Single-Cell NGS in Chemogenomics: Revolutionizing Drug Discovery from Target to Clinic

This article explores the transformative impact of single-cell Next-Generation Sequencing (sc-NGS) on chemogenomics, the study of genome-wide compound interactions.

Single-Cell NGS in Chemogenomics: Revolutionizing Drug Discovery from Target to Clinic

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of single-cell Next-Generation Sequencing (sc-NGS) on chemogenomics, the study of genome-wide compound interactions. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it details how sc-NGS technologies like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) are providing unprecedented resolution to decipher cellular heterogeneity in drug responses. We cover foundational principles, methodological advances for target identification and validation, and practical solutions for technical challenges. The article also provides a comparative analysis of computational tools for data interpretation and concludes with the future clinical implications of integrating single-cell multi-omics and artificial intelligence into the drug discovery pipeline.

The Single-Cell Revolution: Core Principles and Its Entry into Chemogenomics

The advent of single-cell next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed biomedical research by enabling the detailed molecular characterization of individual cells. Traditional bulk sequencing methods average signals across thousands to millions of cells, effectively masking critical cell-to-cell variations that underlie development, disease progression, and therapeutic response [1] [2]. The single-cell approach has revealed that even seemingly homogeneous cell populations exhibit substantial heterogeneity at genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic levels, with profound implications for understanding biological systems [3] [4].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), first described in 2009, marked the beginning of this revolution by allowing researchers to profile gene expression in individual cells [5] [6]. Since then, the field has rapidly expanded beyond transcriptomics to encompass a diverse array of molecular profiling techniques, collectively known as single-cell multi-omics. These technologies enable simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers within the same cell, providing unprecedented insights into the complex regulatory networks governing cellular function [5] [1]. In 2019, single-cell multimodal omics was rightfully selected as Method of the Year, highlighting its transformative potential [5].

In chemogenomics research, which focuses on the systematic identification of drug targets and understanding compound mechanisms of action, single-cell NGS technologies offer powerful tools for dissecting drug response heterogeneity, identifying rare resistant cell populations, and understanding how genetic perturbations translate to phenotypic outcomes [7] [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the single-cell NGS landscape, with particular emphasis on practical protocols and applications relevant to drug discovery and development.

Foundational Single-Cell Sequencing Approaches

Single-cell sequencing technologies have evolved from specialized, low-throughput methods to high-throughput, commercially accessible platforms that can process thousands of cells in parallel. The core principle underlying all scRNA-seq methods involves isolating individual cells, capturing polyadenylated mRNA molecules, reverse transcribing them to cDNA, amplifying the cDNA, and preparing sequencing libraries [8] [4]. Critical technical innovations that have enabled this progress include unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias, microfluidic partitioning systems for high-throughput processing, and advanced barcoding strategies for multiplexing [6] [1].

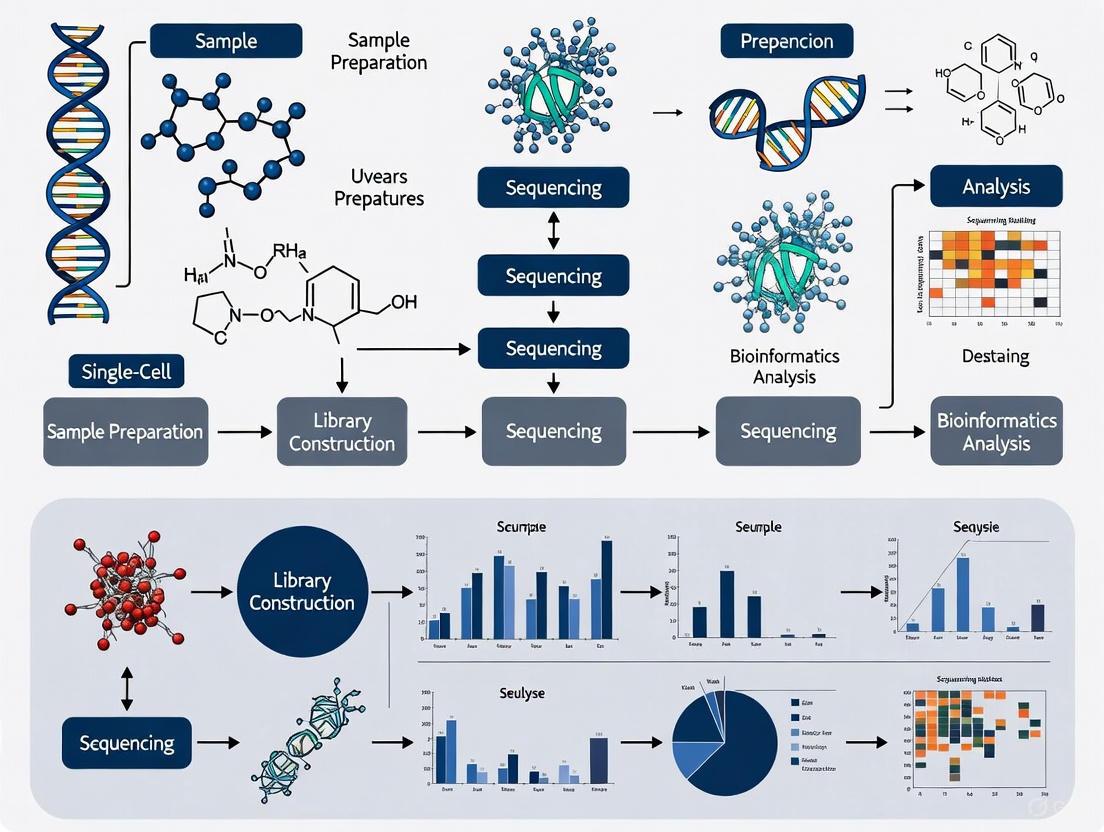

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow and key decision points in single-cell RNA sequencing experiments:

Table 1: Major scRNA-seq Technologies and Their Characteristics

| Technology | Read Coverage | Throughput | UMIs | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium [1] | 3' counting | High (10,000-100,000 cells) | Yes | Large-scale cell atlas projects, tumor heterogeneity |

| Smart-seq2 [4] | Full-length | Low (96-384 cells) | No | Alternative splicing, SNP detection, rare cell characterization |

| CEL-Seq2 [1] | 3' counting | Medium to High | Yes | Developmental biology, time-course experiments |

| MARS-Seq [8] | 3' counting | High | Yes | Large-scale screening, immune profiling |

| Drop-seq [1] | 3' counting | High | Yes | Cost-effective large-scale studies |

| SPLiT-seq [1] | 3' counting | Very High (>1 million cells) | Yes | Fixed samples, large-scale atlas construction |

The choice of scRNA-seq method involves important trade-offs between throughput, sensitivity, and information content. High-throughput 3' counting methods like 10X Genomics Chromium and Drop-seq enable researchers to profile tens of thousands of cells, making them ideal for comprehensive cell atlas projects and identifying rare cell populations within heterogeneous samples [1] [8]. In contrast, full-length transcript methods like Smart-seq2 provide complete coverage of transcript sequences, enabling detection of alternative splicing, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and allele-specific expression, albeit at lower throughput [4]. The incorporation of UMIs has been particularly valuable for accurate transcript quantification, as they enable distinction between biological duplicates and PCR amplification artifacts [6] [8].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Integration

Single-cell multi-omics technologies represent the cutting edge of the field, allowing simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular modalities within the same cell. This capability is particularly valuable for establishing causal relationships between genomic variation, epigenetic regulation, transcription, and protein expression [5] [2]. By capturing layered information from individual cells, researchers can move beyond correlative observations to mechanistic understanding of cellular behavior and drug responses.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for single-cell multi-omics integration and its applications in biomedicine:

Table 2: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies and Their Applications

| Technology/Approach | Molecular Modalities | Key Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| CITE-seq [5] | RNA + Surface Proteins | Immune profiling, cell surface target validation, immunophenotyping |

| scTCR-seq/scBCR-seq [5] | RNA + Immune Receptors | T/B cell clonality tracking, immunotherapy development |

| SHARE-seq [1] | Chromatin Accessibility + RNA | Regulatory network inference, enhancer-promoter mapping |

| 10X Genomics Multiome | Chromatin Accessibility + RNA | Gene regulatory mechanisms in drug response |

| TEA-seq [2] | RNA + Protein + Epigenetics | Comprehensive cellular profiling for therapeutic target ID |

| SCoPE2 [7] | RNA + Protein | Direct correlation of transcript and protein abundance |

The simultaneous measurement of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information from the same cell enables direct correlation between biomolecular layers, moving beyond statistical correlations derived from separate experiments [2]. For example, researchers can directly observe how a specific DNA mutation impacts gene expression and subsequent protein translation within individual cells, providing unprecedented insight into disease mechanisms and drug mode of action. Multi-omics approaches are particularly valuable for identifying rare cell subclones that drive disease progression and therapeutic resistance, as they can detect and characterize populations representing as little as 0.1% of cells that might be missed by conventional bulk sequencing [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard scRNA-seq Workflow Using 10X Genomics Platform

The 10X Genomics Chromium system has emerged as one of the most widely used platforms for high-throughput scRNA-seq due to its robustness, commercial availability, and ability to process thousands of cells in a single run. The following protocol describes a standard workflow for sample preparation through library construction:

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation (Day 1)

- Tissue Dissociation: Prepare single-cell suspension from fresh or preserved tissue using appropriate enzymatic or mechanical dissociation methods. For difficult-to-dissociate tissues, consider nuclear isolation (snRNA-seq) as an alternative [3].

- Cell Viability and Concentration Assessment: Determine cell viability using trypan blue exclusion or fluorescent viability dyes. Viability should exceed 80% for optimal performance. Quantify cell concentration using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter.

- Cell Suspension Preparation: Adjust cell concentration to 700-1,200 cells/μL in phosphate-buffered saline or culture medium containing serum or protein (0.04-1.0% BSA). Avoid excessive EDTA or calcium chelators that might interfere with droplet formation.

- Chip Loading and Partitioning: Combine cells, Master Mix, and Partitioning Oil on the Chromium Chip according to manufacturer's instructions. Target cell recovery between 500-10,000 cells per sample, anticipating a multiplet rate of approximately 1% when following the 10X Genomics recovery guidelines.

Library Preparation (Day 1-3)

- Gel Bead-in-Emulsion (GEM) Formation: Within each droplet, individual cells are co-partitioned with a barcoded gel bead. Cells are lysed upon encapsulation, and polyadenylated RNA molecules hybridize to the poly(dT) primers containing cell barcodes and UMIs [1] [8].

- Reverse Transcription: Perform reverse transcription in a thermal cycler (53°C for 45 min, then 85°C for 5 min) to generate barcoded cDNA. The resulting cDNA shares a common barcode for all transcripts originating from the same cell.

- cDNA Amplification: Break emulsions and purify cDNA using DynaBeads MyOne Silane Beads. Amplify cDNA with PCR (12 cycles) to generate sufficient material for library construction.

- Library Construction: Fragment the amplified cDNA and add sample indices and sequencing adapters through End Repair, A-tailing, Adaptor Ligation, and PCR (12 cycles). The final libraries contain P5 and P7 primers for cluster generation on Illumina sequencers, sample index for multiplexing, and the cell barcode and UMI information [8].

Quality Control and Sequencing

- Library QC: Assess library quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation (expect peak at ~400-500 bp) and quantify by qPCR (Kapa Biosystems).

- Sequencing: Load libraries onto an Illumina sequencer (NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 500, or HiSeq 4000). For 10X 3' v3 libraries, sequence to a depth of 20,000-50,000 reads per cell using the following read configuration: Read 1: 28 cycles, i7 Index: 10 cycles, i5 Index: 10 cycles, Read 2: 90 cycles [8].

CITE-seq for Combined Transcriptome and Protein Profiling

Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing (CITE-seq) enables simultaneous measurement of gene expression and surface protein abundance in single cells by using oligonucleotide-labeled antibodies [5] [9]. This protocol can be integrated with the 10X Genomics platform:

Antibody Conjugation and Validation (Pre-experiment)

- Antibody Selection: Choose purified antibodies against surface proteins of interest. Avoid antibodies containing carrier proteins or stabilizers that might interfere with conjugation.

- Oligo Conjugation: Conjugate antibodies to oligonucleotides containing PCR handles, barcodes, and poly(A) sequences using maleimide chemistry. Validate conjugation efficiency by HPLC or mass spectrometry.

- Titration and Validation: Titrate conjugated antibodies on relevant cell lines to determine optimal staining concentration. Validate specificity using knockout cell lines or isotype controls.

Cell Staining and Processing (Day 1)

- Cell Staining: Wash cells with PBS + 0.04% BSA and incubate with titrated antibody cocktail for 30 minutes on ice. Include a hashing antibody (if sample multiplexing is desired) and a viability antibody (e.g., TotalSeq-C) for dead cell exclusion.

- Cell Washing: Wash cells 3 times with PBS + 0.04% BSA to remove unbound antibodies.

- Cell Counting and Viability Assessment: Determine cell concentration and viability, then proceed to 10X Genomics library preparation as described in section 3.1.

Library Preparation and Sequencing (Day 1-3)

- Separate Library Construction: Following the standard 10X Genomics workflow, prepare two separate libraries: (1) the gene expression library following the standard protocol, and (2) the antibody-derived tag (ADT) library using a separate PCR with primers specific to the antibody oligo sequences.

- Differential Amplification: For ADT library, use 10-14 PCR cycles depending on antibody signal strength. For gene expression library, follow standard amplification conditions.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries at an appropriate ratio (typically 10:1 gene expression:ADT library) and sequence on an Illumina platform. The ADT library requires significantly fewer reads (1,000-5,000 reads per cell) compared to gene expression library.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of single-cell sequencing data requires specialized bioinformatics tools to handle its high dimensionality, technical noise, and sparsity [5] [10]. A standard analytical workflow includes:

Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Raw Data Processing: Use Cell Ranger (10X Genomics) or STARsolo to demultiplex raw sequencing data, align reads to the reference genome, and generate gene-cell count matrices with cell barcodes and UMIs.

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells using tools like Seurat or Scanpy based on the following criteria [9]:

- Cells with unusually high or low numbers of detected genes (potential multiplets or empty droplets)

- Cells with high mitochondrial read percentage (>10-20%), indicating stress or apoptosis

- Cells with low number of total UMIs/transcripts

- Normalization and Scaling: Normalize counts using methods like SCTransform (Seurat) or log(CP10K+1) to account for sequencing depth variation. Regress out confounding factors like mitochondrial percentage and cell cycle stage.

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes (1,000-5,000) that drive biological heterogeneity.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on scaled data, then use the top principal components (typically 10-30) for non-linear dimensionality reduction with UMAP or t-SNE.

- Clustering: Apply graph-based clustering algorithms (Louvain or Leiden) to identify cell populations. Resolution parameters may need optimization based on the biological context.

Cell Type Annotation and Differential Expression

- Cell Annotation: Identify cluster-specific marker genes using differential expression tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) and annotate cell types based on canonical markers and reference databases [9].

- Reference Mapping: For improved annotation, map datasets to established references like the Human Cell Atlas using tools like Seurat's label transfer or SCTransform-based integration.

- Differential Analysis: Identify differentially expressed genes between conditions (e.g., treated vs. control) within specific cell types, using methods that account for the unique characteristics of single-cell data (e.g., MAST, DESingle).

Advanced Analyses

- Trajectory Inference: Reconstruct developmental or transition trajectories using tools like Monocle3, PAGA, or Slingshot to order cells along pseudotemporal axes [5].

- RNA Velocity: Analyze spliced vs. unspliced mRNA ratios to predict future cell states using scVelo or Velocyto [5].

- Cell-Cell Communication: Infer ligand-receptor interactions between cell types using tools like CellChat or NicheNet [9].

- Regulatory Network Analysis: Identify gene regulatory networks using SCENIC based on co-expression and transcription factor binding motifs [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful single-cell sequencing experiments require careful selection of reagents and tools throughout the workflow. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Single-Cell Sequencing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Assays | Trypan blue, Propidium iodide, Fluorescent viability dyes (Calcein AM, DAPI) | Assessment of cell viability and integrity before processing; critical for data quality |

| Dissociation Reagents | Collagenase, Trypsin-EDTA, Accutase, Liberase, Tumor Dissociation Kits | Tissue-specific enzymatic blends for generating high-quality single-cell suspensions |

| Surface Protein Staining | TotalSeq antibodies (BioLegend), CITE-seq antibodies | Oligo-conjugated antibodies for simultaneous protein detection in scRNA-seq |

| Cell Hashing Reagents | TotalSeq-H antibodies, MULTI-seq lipid-modified barcodes | Sample multiplexing to reduce batch effects and costs by pooling samples before processing |

| Bead-Based Cleanup | SPRIselect beads, DynaBeads MyOne Silane | Size selection and purification of nucleic acids during library preparation |

| Amplification Reagents | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix, SMARTer reagents | High-fidelity PCR amplification of limited cDNA from single cells |

| Library Preparation Kits | 10X Genomics Chromium Next GEM Kits, Parse Biosciences kits | Commercial solutions for preparing barcoded single-cell libraries |

| QC Instruments | Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation, Qubit fluorometer, Automated cell counters | Quality assessment of input cells, RNA, and final libraries |

| Single-Cell Analysis Software | Seurat, Scanpy, Cell Ranger, Partek Flow | Bioinformatics tools for processing, analyzing, and visualizing single-cell data |

Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

Single-cell NGS technologies have emerged as powerful tools in chemogenomics research, enabling unprecedented resolution in understanding drug mechanisms, identifying novel targets, and characterizing therapeutic resistance. Three key applications demonstrate their transformative potential:

Elucidating Heterogeneous Drug Responses Single-cell RNA sequencing enables researchers to move beyond population-averaged drug responses to characterize how individual cells within a population respond differently to compound treatment. This is particularly valuable for understanding partial efficacy, biphasic responses, and identifying resistant subpopulations [7]. For example, in cancer drug screening, scRNA-seq has revealed distinct transcriptional programs in persistent cells following targeted therapy, including upregulated survival pathways, stress response programs, and dormant states that may serve as reservoirs for disease recurrence [3]. By profiling these rare subpopulations, researchers can identify novel combination therapy strategies to prevent or overcome resistance.

Target Identification and Validation Single-cell multi-omics approaches provide powerful methods for target identification by linking genetic variation to phenotypic consequences at unprecedented resolution. In oncology, combined scDNA-seq and scRNA-seq can identify how specific mutations influence transcriptional programs and cellular phenotypes within the context of tumor heterogeneity [2]. Similarly, in immunology, CITE-seq enables comprehensive profiling of immune cell states and surface protein expression, facilitating identification of novel immunotherapy targets [9]. The ability to simultaneously measure chromatin accessibility and gene expression (e.g., through SHARE-seq or 10X Multiome) further enables identification of regulatory elements and transcription factors driving disease-relevant cell states.

Characterizing Cellular Mode of Action Single-cell technologies enable comprehensive characterization of how small molecules and biologics perturb cellular networks by profiling thousands of individual cells following treatment. This approach can reveal on-target and off-target effects, identify biomarkers of response, and delineate heterogeneous mechanisms of action [7]. For cell and gene therapies, single-cell multi-omics provides rigorous characterization of therapeutic products, enabling quality control and assessment of product consistency [2]. In one application, combined scRNA-seq and scTCR-seq has been used to track clonal dynamics of T-cell populations following immunotherapy, linking specific TCR sequences to transcriptional states associated with clinical response [5].

The single-cell NGS landscape has evolved from specialized transcriptomic profiling to a sophisticated toolkit for multi-omic characterization of individual cells. These technologies provide unprecedented resolution for exploring cellular heterogeneity, tracing developmental trajectories, and understanding complex biological systems. In chemogenomics and drug discovery, single-cell approaches are transforming target identification, mechanism of action studies, and resistance characterization by revealing how cellular heterogeneity influences drug response.

As single-cell technologies continue to advance, several trends are shaping the field. Computational methods, particularly machine learning approaches, are playing an increasingly important role in analyzing complex multi-omic datasets and extracting biological insights [10]. Spatial transcriptomic technologies are adding crucial spatial context to single-cell data, enabling researchers to understand how cellular organization influences function and drug response [5] [9]. Meanwhile, ongoing efforts to reduce costs and increase throughput are making these powerful technologies more accessible for broader applications.

For researchers implementing single-cell approaches, success depends on careful experimental design, appropriate technology selection, and robust analytical strategies. Matching the right single-cell method to the biological question, ensuring high-quality sample preparation, and applying appropriate computational analyses are all critical for generating meaningful results. As these technologies continue to mature and integrate, they promise to further accelerate the pace of discovery in chemogenomics and therapeutic development.

In the pursuit of personalized cancer therapeutics, accurately predicting how tumors respond to drugs remains a formidable challenge. Traditional drug response prediction methods have largely relied on bulk RNA sequencing, which provides an average gene expression profile across all cells in a sample. While valuable for population-level insights, this approach fundamentally obscures a critical biological reality: tumors are not homogeneous masses of identical cells, but complex ecosystems composed of diverse cell subtypes with distinct transcriptional profiles and functional states. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in drug discovery, where the presence of rare, pre-existing resistant cell populations can dictate treatment outcomes yet remain undetectable in bulk measurements. The averaging effect of bulk sequencing masks the very cellular heterogeneity that drives variable treatment responses, creating a significant blind spot in therapeutic development [11] [12] [13].

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally altered this landscape by enabling researchers to probe transcriptomic profiles at the resolution of individual cells. This technological shift reveals the cellular composition and interaction networks within tumors, providing unprecedented insights into the mechanisms underlying drug sensitivity and resistance. By capturing the full spectrum of cellular states present in a tumor ecosystem, scRNA-seq allows for the identification of specific cell subpopulations that survive treatment and ultimately drive disease recurrence [11] [14]. This application note explores the technical limitations of bulk sequencing in resolving cellular heterogeneity, presents experimental frameworks for single-cell pharmacotranscriptomics, and highlights how these advanced approaches are transforming drug discovery pipelines.

The Technical Divide: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The fundamental difference between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing begins at the sample preparation stage and extends throughout the entire experimental workflow. In bulk RNA-seq, the entire biological sample is digested to extract RNA from a pooled population of cells, resulting in a single, averaged gene expression profile that represents the entire cell population [13]. This approach effectively treats complex tissues as uniform entities, blurring critical biological distinctions between cell types and states. In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing requires the generation of a viable single-cell suspension, followed by the partitioning of individual cells into micro-reaction vessels where each cell's transcriptome is uniquely barcoded before sequencing [13]. This preservation of cellular identity throughout the sequencing process enables the reconstruction of individual transcriptomic profiles for each cell within the original sample.

The implications of these methodological differences extend throughout the data generation and analysis pipeline. Bulk sequencing workflows are generally lower in cost, have simpler sample preparation requirements, and generate data that can be analyzed with more straightforward computational approaches [13]. Single-cell protocols, while typically more resource-intensive, generate massively multiplexed datasets that require specialized bioinformatic tools for processing and interpretation but offer unparalleled resolution of cellular heterogeneity [11] [13]. The choice between these approaches therefore represents a trade-off between practical considerations and biological resolution, with single-cell methods providing the necessary granularity to identify rare cell populations and continuous cellular transitions that are invisible in bulk data.

Quantitative Limitations of Bulk Sequencing in Heterogeneous Samples

Table 1: Comparative Limitations of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Drug Response Studies

| Aspect | Bulk RNA-Seq Limitations | Single-Cell RNA-Seq Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution of Cellular Heterogeneity | Provides only population-average data, masking rare cell types (<5% abundance) [13] | Identifies rare cell populations down to 0.1-1% abundance and distinct cell states [11] [13] |

| Detection of Resistance Mechanisms | Cannot identify pre-existing resistant subclones; resistance signatures diluted by sensitive cells [15] [16] | Reveals pre-treatment resistant subpopulations and tracks their expansion post-treatment [15] [14] |

| Characterization of Transitional States | Obscures continuous cellular transitions (e.g., epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition) [12] | Maps continuous trajectories and transitional states using pseudotime algorithms [11] |

| Identification of Cell-Type Specific Responses | Cannot attribute gene expression changes to specific cell types; cell-type specific signals are confounded [17] [13] | Precisely links drug response signatures to specific cell subtypes and states within complex mixtures [14] |

| Analysis of Tumor Microenvironment | Fails to resolve complex cell-cell interaction networks between tumor and stromal/immune cells [14] | Enables comprehensive characterization of tumor ecosystem and cell-cell communication [11] [14] |

The quantitative limitations of bulk sequencing become particularly evident when analyzing highly heterogeneous samples like tumors. The averaging effect means that gene expression signals from rare cell populations (generally those representing less than 5-10% of the total population) become diluted below reliable detection thresholds [13]. In the context of drug response, this is particularly problematic as pre-existing resistant subclones often represent only a small fraction of the total tumor cell population before treatment but ultimately determine therapeutic outcome. Bulk sequencing cannot resolve these critical minority populations, whereas single-cell approaches can identify rare cell types representing as little as 0.1-1% of the total population [11] [13].

Furthermore, bulk sequencing fundamentally cannot resolve continuous biological processes such as cellular differentiation trajectories or state transitions that occur along biological continua. In cancer, these transitions—such as the emergence of drug-tolerant persister cells or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition—represent critical mechanisms of adaptation and resistance. Single-cell technologies can capture these continuous processes through pseudotime analysis, revealing the transcriptional programs that enable cells to transition from sensitive to resistant states [15] [11]. This capability provides insights into the dynamic nature of tumor evolution under therapeutic pressure that are completely inaccessible through bulk profiling approaches.

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches, highlighting where cellular heterogeneity information is lost versus preserved.

Case Study: ATSDP-NET - Overcoming Bulk Sequencing Limitations Through Transfer Learning

Experimental Framework and Protocol

The ATSDP-NET (Attention-based Transfer Learning for Enhanced Single-cell Drug Response Prediction) framework represents a sophisticated computational approach that directly addresses the limitations of bulk sequencing while leveraging existing bulk data resources [15] [16]. This method employs a transfer learning strategy that pre-trains a deep learning model on large-scale bulk RNA-seq datasets from resources like the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC), then fine-tunes the model on smaller scRNA-seq datasets for single-cell drug response prediction [15] [16]. The protocol involves several key stages:

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Bulk RNA-seq data: Curate drug response data from CCLE and GDSC databases containing genomic profiles and drug sensitivity measurements (IC50 values) across hundreds of cancer cell lines [15] [16].

- Single-cell RNA-seq data: Collect scRNA-seq data from tumor cells pre- and post-drug treatment across multiple cancer types (e.g., oral squamous cell carcinoma with cisplatin, prostate cancer with docetaxel, AML with I-BET-762) [15] [16].

- Response labeling: Assign binary response labels (sensitive=1, resistant=0) to individual cells based on post-treatment viability assays, using established thresholds from original datasets or quantile-based binarization of continuous response values [15] [16].

2. Model Architecture and Training:

- Implement a multi-head attention mechanism within a deep neural network to identify gene expression patterns predictive of drug response at single-cell resolution [15] [16].

- Address class imbalance in labeled datasets using SMOTE oversampling for DATA1 and standard oversampling for DATA2-DATA4 [15] [16].

- Perform model validation using recall, ROC curves, and average precision (AP) metrics on held-out test sets [15] [16].

3. Interpretation and Visualization:

- Identify critical genes associated with drug responses through attention weight analysis [15] [16].

- Visualize the dynamic transition of cells from sensitive to resistant states using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [15] [16].

- Validate predictions through differential gene expression scoring and correlation analysis with actual response values [15] [16].

Key Findings and Performance Metrics

Table 2: ATSDP-NET Performance Metrics Across Single-Cell Drug Response Datasets

| Dataset | Cancer Type | Treatment | Key Performance Metrics | Biological Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DATA1 | Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Cisplatin | High correlation for sensitivity gene scores (R=0.888, p<0.001) [15] [16] | Accurate prediction of cisplatin sensitivity/resistance patterns [15] [16] |

| DATA2 | Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Cisplatin | Consistent performance across technical replicates [15] [16] | Confirmation of heterogeneous response within tumor [15] [16] |

| DATA3 | Human Prostate Cancer | Docetaxel | Superior to existing methods in ROC and AP metrics [15] [16] | Identification of taxane resistance mechanisms [15] [16] |

| DATA4 | Murine Acute Myeloid Leukemia | I-BET-762 | High correlation for resistance gene scores (R=0.788, p<0.001) [15] [16] | Accurate mapping of sensitive-to-resistant transition states [15] [16] |

The ATSDP-NET framework demonstrated superior performance compared to existing methods across all evaluation metrics, including recall, ROC curves, and average precision [15] [16]. More importantly, it successfully identified critical genes associated with drug responses and visualized the dynamic process of cells transitioning from sensitive to resistant states—capabilities that are impossible with bulk sequencing approaches. The high correlation between predicted sensitivity gene scores and actual values (R=0.888, p<0.001), along with significant correlation for resistance gene scores (R=0.788, p<0.001), confirms the model's ability to capture biologically meaningful signals at single-cell resolution [15] [16].

The multi-head attention mechanism proved particularly valuable for interpretability, allowing researchers to pinpoint specific gene expression patterns driving drug sensitivity and resistance in different cellular subpopulations [15] [16]. This represents a significant advance over "black box" prediction models, as it provides biological insights into the mechanisms underlying treatment failure while simultaneously offering accurate response predictions. The framework effectively bridges the gap between large-scale bulk sequencing resources and the high-resolution insights provided by newer single-cell technologies, demonstrating a practical path forward for leveraging existing investments in bulk profiling while embracing the future of single-cell analysis.

Advanced Experimental Framework: Multiplexed Single-Cell Pharmacotranscriptomics

High-Throughput Pipeline for Drug Discovery

A recently published advanced pipeline for pharmacotranscriptomic profiling demonstrates how single-cell technologies are being scaled for comprehensive drug discovery applications [14]. This approach combines live-cell barcoding using antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates with 96-plex single-cell RNA sequencing to enable high-throughput screening of transcriptional responses to drug treatments. The experimental workflow includes:

1. Sample Preparation and Drug Treatment:

- Isolate and culture primary cancer cells (e.g., high-grade serous ovarian cancer models) at early passages to maintain phenotypic identity [14].

- Treat cells with a diverse library of 45 drugs covering 13 distinct mechanisms of action (including PI3K-AKT-mTOR inhibitors, Ras-Raf-MEK pathway inhibitors, epigenetic modifiers, and DNA damage agents) [14].

- Use DMSO as a control and employ drug concentrations above the half-maximal effective concentration based on preliminary drug sensitivity and resistance testing (DSRT) screens [14].

2. Multiplexing and Single-Cell Profiling:

- Label cells from each treatment condition with unique pairs of anti-β2 microglobulin (B2M) and anti-CD298 antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (Hashtag oligos or HTOs) [14].

- Pool samples for multiplexed scRNA-seq processing, dramatically reducing batch effects and technical variability while increasing throughput [14].

- Sequence using 10X Chromium technology, processing 36,016 high-quality cells across 288 samples with a median of 122-140 cells per treatment condition [14].

3. Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Demultiplex cells based on HTO barcodes and perform quality control to remove doublets and low-quality cells [14].

- Conduct unsupervised clustering using Leiden algorithm to identify drug-responsive cell states across different mechanisms of action [14].

- Perform gene set variation analysis (GSVA) to evaluate activity of biological processes and pathways affected by different drug classes [14].

Key Insights from Multiplexed Pharmacotranscriptomic Screening

This multiplexed approach revealed several critical insights that would be inaccessible through bulk sequencing methods. First, it uncovered significant heterogeneity in drug responses even within supposedly homogeneous cancer cell lines, with different cells exhibiting distinct transcriptional programs after identical drug treatments [14]. Second, the analysis identified previously unknown resistance mechanisms, including a feedback loop whereby PI3K-AKT-mTOR inhibitors induced upregulation of caveolin 1 (CAV1), leading to activation of receptor tyrosine kinases like EGFR—a resistance mechanism that could be mitigated through combination therapy targeting both pathways [14].

Perhaps most importantly, the single-cell resolution enabled researchers to observe that cells treated with different classes of inhibitors exhibited distinct clustering patterns: those treated with PI3K-AKT-mTOR, Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK, and multikinase inhibitors showed milder, model-specific transcriptional shifts, while cells treated with BET, HDAC, and CDK inhibitors formed distinct clusters enriched with cells from all three tested models, suggesting more consistent cross-lineage effects [14]. This type of comparative analysis across mechanisms of action and cancer models provides invaluable insights for drug development prioritization and combination therapy design.

Diagram 2: High-throughput multiplexed single-cell pharmacotranscriptomics workflow for comprehensive drug response profiling.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Drug Response Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Technology | Function in Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Platform | 10X Genomics Chromium System [14] [13] | Enables high-throughput single-cell partitioning and barcoding using microfluidics technology |

| Multiplexing Reagents | Cell Hashing Antibodies (Anti-B2M, Anti-CD298) [14] | Allow sample multiplexing through antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates that label live cells |

| Reference Databases | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [15] [16] | Provides bulk RNA-seq and drug response data for transfer learning approaches |

| Reference Databases | Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) [15] [16] | Offers comprehensive drug sensitivity data across cancer cell lines for model training |

| Computational Tools | ATSDP-NET Framework [15] [16] | Implements attention mechanisms and transfer learning for single-cell drug response prediction |

| Computational Tools | MrVI (Multi-Resolution Variational Inference) [18] | Enables exploratory and comparative analysis of multi-sample single-cell studies |

| Visualization Tools | UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) [15] [16] | Visualizes high-dimensional single-cell data in two dimensions for interpretation |

| Analysis Suites | scvi-tools [18] | Provides scalable probabilistic models for single-cell omics data analysis |

Successful implementation of single-cell drug response studies requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The 10X Genomics Chromium platform has emerged as a widely adopted solution for high-throughput single-cell partitioning and barcoding, offering robust, instrument-enabled workflows that reduce technical variability [14] [13]. For multiplexing experiments, cell hashing technologies using antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates against ubiquitously expressed surface markers like B2M and CD298 enable massive parallelization of drug treatment conditions while controlling for batch effects [14].

On the computational side, leveraging existing reference databases like CCLE and GDSC provides the foundational bulk data necessary for transfer learning approaches that overcome limitations in single-cell dataset sizes [15] [16]. Specialized computational frameworks like ATSDP-NET incorporate multi-head attention mechanisms to simultaneously predict drug responses and identify predictive gene patterns [15] [16], while tools like MrVI (Multi-Resolution Variational Inference) enable sophisticated analysis of sample-level heterogeneity in large-scale single-cell studies without requiring predefined cell states [18]. The integration of these wet-lab and computational tools creates a powerful ecosystem for advancing single-cell pharmacotranscriptomics in both basic research and clinical translation.

The limitations of bulk RNA sequencing in resolving cellular heterogeneity represent more than just a technical shortcoming—they constitute a fundamental barrier to understanding the complex biology of drug response in cancer and other diseases. As the case studies presented here demonstrate, single-cell technologies are already overcoming these limitations by revealing the cellular subpopulations and transitional states that determine therapeutic outcomes. The integration of these approaches with advanced computational methods like transfer learning and attention mechanisms creates a powerful framework for predicting drug responses while simultaneously generating biologically interpretable insights into resistance mechanisms.

Looking forward, the field is moving toward even more sophisticated multi-omic approaches that combine single-cell transcriptomics with spatial context, genetic perturbations, and proteomic measurements [19] [20]. The ongoing development of specialized computational tools like MrVI for analyzing multi-sample single-cell studies further enhances our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from these complex datasets [18]. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly transform drug discovery pipelines and clinical translation, ultimately enabling more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies that account for the profound heterogeneity inherent in cancer and other complex diseases.

The advent of single-cell technologies has fundamentally transformed pharmacological research, enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity and its profound implications for drug discovery and development. Traditional bulk sequencing methods, which average signals across thousands to millions of cells, inevitably obscure rare cell populations, transient cellular states, and subtle but therapeutically significant transcriptional differences. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), first described in 2009, initiated a paradigm shift by allowing researchers to investigate gene expression profiles at the individual cell level [10] [8]. This technological revolution has since expanded to encompass multi-omic approaches that simultaneously probe the genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome within single cells, providing unprecedented insights into cellular mechanisms of disease and therapeutic response [1].

In the context of chemogenomics research, which seeks to understand the complex interactions between biological systems and chemical compounds, single-cell technologies offer particularly powerful applications. By revealing how individual cells within a tissue or tumor respond to chemical perturbations, these methods accelerate target identification, validate mechanism of action, and stratify patient populations for precision medicine. The integration of single-cell technologies with pharmacological research has created a new frontier where drug discovery is increasingly guided by deep molecular understanding of cellular heterogeneity, leading to more effective and targeted therapeutic strategies [21].

Historical Trajectory: Milestones in Single-Cell Technology Development

The evolution of single-cell technologies represents a remarkable journey of innovation, marked by key methodological breakthroughs that have progressively enhanced our ability to probe cellular complexity. The timeline of development reflects a consistent drive toward higher throughput, multi-parameter analysis, and clinical translation.

Table 1: Key Milestones in Single-Cell Technology Development

| Year | Technological Milestone | Significance for Pharmacological Research |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | First scRNA-seq protocol described [8] | Enabled transcriptomic analysis of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity in disease contexts |

| 2013 | Single-cell epigenome sequencing developed [22] | Allowed investigation of epigenetic mechanisms in drug response and resistance |

| 2015 | High-throughput droplet-based scRNA-seq (Drop-Seq, inDrop) [10] [8] | Scaled analysis to thousands of cells, enabling comprehensive atlas projects and rare cell population detection |

| 2015-2016 | First single-cell multi-omics assays [22] | Enabled correlated analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic features within single cells |

| 2016 | Spatial transcriptomics methods published [22] | Preserved spatial context of cellular interactions relevant to drug distribution and activity |

| 2020s | Automated, integrated multi-omics platforms [23] [19] | Streamlined workflow for applied drug discovery and clinical translation |

The initial single-cell transcriptomic approaches, while groundbreaking, were limited by low throughput and high costs. The development of droplet-based microfluidics in 2015 represented a pivotal advance, dramatically increasing the number of cells that could be profiled in a single experiment while reducing per-cell costs [8]. This scalability enabled researchers to capture rare cell types and transitional states that are often crucial in disease progression and treatment response. The subsequent emergence of single-cell multi-omics further expanded analytical capabilities by allowing simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers within the same cell, providing insights into coordinated regulatory mechanisms that underlie drug sensitivity and resistance [22] [1].

More recently, spatial transcriptomics has addressed a fundamental limitation of early single-cell methods—the loss of anatomical context. By preserving and mapping the spatial organization of cells within tissues, these techniques have revealed how cellular microenvironment influences drug response, particularly in complex tissues like tumors [22]. The ongoing integration of these technological streams—high-throughput sequencing, multi-omic profiling, and spatial context—creates an increasingly powerful platform for pharmacological investigation, enabling researchers to build comprehensive models of drug action across diverse cellular contexts.

Current Applications in Pharmacological Research

Single-cell technologies have matured from specialized research tools to essential components of the drug discovery pipeline, impacting multiple stages from target identification to clinical trial design. The ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity at molecular scale has proven particularly valuable in oncology, immunology, and neuroscience, where disease mechanisms often involve complex interactions between diverse cell populations.

Target Identification and Validation

The initial stage of drug discovery depends critically on identifying and validating molecular targets with strong causal links to disease processes. Single-cell technologies excel in this domain by enabling cell-type-specific resolution of gene expression patterns across entire tissues. A 2024 retrospective analysis conducted by researchers at the Wellcome Institute demonstrated that drugs targeting genes with cell-type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues showed significantly higher success rates in progressing from Phase I to Phase II clinical trials [21]. This approach allows researchers to focus on targets with greater biological relevance and potentially fewer off-target effects.

The combination of scRNA-seq with CRISPR screening has emerged as a particularly powerful method for functional target validation. In one landmark application, researchers profiled approximately 250,000 primary CD4+ T cells to systematically map regulatory element-to-gene interactions and functionally interrogate non-coding regulatory elements at single-cell resolution [21]. This integrated approach not only identifies potential drug targets but also elucidates their functional mechanisms within native cellular contexts, derisking subsequent development stages.

Drug Screening and Mechanism of Action Studies

Beyond target identification, single-cell technologies are transforming conventional drug screening paradigms. Traditional screening approaches typically rely on bulk readouts like cell viability or limited marker expression, providing insufficient information about heterogeneous responses across cell types. High-throughput scRNA-seq now enables detailed, cell-type-specific gene expression profiling across multiple drug doses and experimental conditions, capturing complex response dynamics that would be masked in bulk analyses [21].

The power of this approach was demonstrated in a pioneering study that measured 90 cytokine perturbations across 18 immune cell types from twelve donors, resulting in nearly 20,000 observed perturbations captured in a 10 million-cell dataset [21]. This unprecedented resolution revealed that while certain cell types shared overall response patterns to cytokines like IFN-omega, individual cells exhibited distinct behaviors and reactions—a level of biological nuance that would have been undetectable in smaller datasets. Such insights are invaluable for understanding both intended therapeutic effects and potential off-target consequences during early drug development.

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

The translation of drug candidates from preclinical models to clinical success depends heavily on identifying robust biomarkers that can guide patient selection and monitor treatment response. Single-cell approaches have demonstrated particular utility in defining more accurate biomarkers and disease classifications based on cellular heterogeneity. In colorectal cancer, for instance, scRNA-seq has enabled new molecular classifications with subtypes distinguished by unique signaling pathways, mutation profiles, and transcriptional programs [21].

These refined stratification schemes support more precise targeting of therapeutic interventions to patient subgroups most likely to respond. Furthermore, single-cell analysis of liquid biopsies and longitudinal tissue samples provides opportunities to monitor dynamic changes in cellular populations during treatment, enabling early detection of resistance mechanisms and adaptive treatment strategies. The resulting cellular biomarkers offer greater specificity than tissue-level measurements, potentially improving clinical trial success rates through better patient stratification and response monitoring [21].

Table 2: Single-Cell Technology Applications in Drug Development Pipeline

| Drug Development Stage | Single-Cell Application | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Cell-type-specific gene expression mapping in diseased tissues | Identifies targets with higher clinical success potential [21] |

| Target Validation | CRISPR-scRNA-seq perturbation screening | Elucidates functional mechanisms and regulatory networks [21] |

| Lead Optimization | High-throughput multi-dose scRNA-seq screening | Reveals cell-type-specific responses and off-target effects [21] |

| Preclinical Toxicology | Cellular heterogeneity assessment in tissues | Identifies subpopulation-specific toxicities [21] |

| Clinical Trial Design | Biomarker discovery and patient stratification | Enriches for responders and monitors treatment resistance [21] |

| Companion Diagnostics | Rare cell population detection in liquid biopsies | Enables non-invasive monitoring of treatment response [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The successful application of single-cell technologies requires careful consideration of experimental design, protocol selection, and analytical approaches. This section outlines core methodologies and their implementation in pharmacological research contexts.

Core Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

The standard scRNA-seq workflow encompasses multiple critical steps, each requiring specific methodological considerations to ensure data quality and biological relevance.

Figure 1: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Core Workflow. Key steps from cell isolation to data analysis with critical reagents and platforms.

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial step of isolating individual cells from tissues or culture systems represents a critical foundation for subsequent analysis. The choice of isolation method depends on tissue type, cell abundance, and experimental objectives:

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Enables selection of specific cell populations based on surface markers or fluorescent reporters, with the ability to simultaneously analyze cells according to size, granularity, and multiple fluorescence parameters [1]. However, FACS requires sufficient cell density and may affect viability through rapid flow and fluorescence exposure.

Microfluidic Droplet-Based Systems: Platforms such as 10x Genomics Chromium utilize nanoliter-scale droplets to encapsulate individual cells with barcoded beads, enabling high-throughput processing of thousands to millions of cells [8] [1]. These systems offer significantly reduced reagent costs and hands-on time compared to plate-based methods.

Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS): Employed for isolation based on surface markers using magnetic beads, offering a gentler alternative to FACS that preserves cell viability, though with lower specificity [1].

Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing (snRNA-seq): Used when tissue dissociation is challenging or samples are frozen, as nuclei are more resistant to isolation stresses. This approach has enabled single-cell analysis of previously intractable tissues like neuronal brain regions [8].

For pharmacological applications involving drug-treated samples, consideration of dissociation-induced stress responses is critical, as these can confound drug response signatures. Rapid processing or fixation protocols may be necessary to preserve authentic transcriptional states.

Molecular Barcoding and Library Preparation

Following cell isolation, the implementation of robust barcoding strategies enables multiplexing and accurate quantification:

Cellular Barcodes: Short DNA sequences added during reverse transcription that uniquely label each cell, allowing pooled sequencing of multiple cells while maintaining individual identity during computational analysis [1].

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Random nucleotide tags added to each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, enabling precise quantification by correcting for amplification biases and distinguishing biological duplicates from technical PCR duplicates [8].

Amplification Methods: Either polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in vitro transcription (IVT) amplification is employed to generate sufficient material for sequencing. PCR-based methods (e.g., SMART-seq2) typically provide better coverage across transcript length, while IVT methods (e.g., CEL-Seq2) offer reduced amplification bias [8].

Protocol selection depends on specific research questions—full-length transcript protocols (SMART-seq3, FLASH-seq) enable isoform analysis and variant detection, while 3'-end counting methods (10x Genomics, Drop-seq) provide more cost-effective cellular profiling [8] [1].

Advanced Multi-Omic Profiling Protocols

The integration of multiple molecular modalities within single cells provides a more comprehensive view of cellular responses to pharmacological interventions.

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Integration

Combined measurement of transcriptome and epigenome in individual cells enables researchers to connect regulatory mechanisms with functional responses:

CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes): Simultaneously measures mRNA expression and surface protein abundance using antibody-derived tags, providing complementary information about cellular identity and functional state [1].

ATAC-seq + RNA-seq: Combines assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with transcriptome profiling to link chromatin accessibility patterns with gene expression programs [22].

SPLiT-seq: A split-pool ligation-based method that enables scalable single-cell transcriptomic profiling without specialized equipment, particularly useful for large-scale drug screening applications [8].

For chemogenomics research, these multi-omic approaches can reveal how drug treatments simultaneously alter epigenetic states, transcriptional programs, and surface protein expression, providing mechanistic insights into both efficacy and resistance.

Spatial Transcriptomics in Pharmacological Research

Preserving spatial context is particularly valuable for understanding drug distribution, target engagement, and microenvironmental influences on treatment response:

Sequential Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (seqFISH/MERFISH): Uses sequential hybridization with fluorescent probes to map hundreds to thousands of RNA species within intact tissue sections, revealing how cellular neighborhoods influence drug sensitivity [22].

In Situ Capturing (Visium/XYZ): Captures RNA from tissue sections on spatially barcoded arrays, allowing correlation of histopathological features with global transcriptional patterns in response to treatment [22] [24].

In Situ Sequencing: Directly sequences cDNA amplicons within tissue sections, providing both spatial localization and sequence information for transcript identification [22].

These spatial methods are particularly powerful when applied to preclinical models treated with drug candidates, as they can reveal heterogeneous drug effects across different tissue regions and cellular microenvironments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of single-cell technologies requires careful selection of reagents, instruments, and computational tools tailored to specific pharmacological research questions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Pharmacology

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Pharmacological Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Kits | MACS Microbeads, FACS antibodies | Isolation of specific cell populations from complex tissues | Target cell enrichment from diseased tissue [1] |

| Single-Cell Library Prep Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences Evercode | Barcoding, reverse transcription, cDNA amplification | High-throughput drug screening across cell types [21] [23] |

| Viability Stains | Propidium iodide, DAPI, Calcein AM | Discrimination of live/dead cells during isolation | Ensure analysis of healthy, drug-affected cells [1] |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Commercial lysis buffers, homebrew formulations | Release of RNA while preserving integrity | Maintain RNA quality for accurate expression profiling [8] |

| UMIs and Barcoded Oligos | Custom-designed UMIs, template-switch oligos | Molecular tagging for quantification and multiplexing | Accurate measurement of drug-induced expression changes [8] |

| Amplification Reagents | SMART-Seq3, MATQ-Seq kits | cDNA amplification from single cells | Detect low-abundance transcripts affected by treatment [8] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Kits | 10x Visium, MERFISH reagents | Spatial mapping of gene expression in tissue | Localization of drug effects within tissue architecture [22] [24] |

| Multi-omics Assays | Tapestri Mission Bio, CITE-seq antibodies | Simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers | Comprehensive view of drug mechanism of action [23] [1] |

The selection of appropriate platforms and reagents should be guided by specific research objectives, with considerations for cell throughput, molecular coverage, and integration with existing laboratory workflows. Commercial platforms from established vendors like 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences, and Mission Bio offer standardized, validated workflows particularly valuable for regulated environments, while more customizable academic protocols may provide advantages for specialized applications [21] [23].

Computational Analysis Framework

The enormous datasets generated by single-cell technologies—routinely encompassing millions of cells and thousands of genes—require sophisticated computational approaches for meaningful biological interpretation. The analysis pipeline typically progresses through several stages, each with specific methodological considerations for pharmacological applications.

Figure 2: Single-Cell Data Analysis Computational Workflow. Key computational steps with representative tools for each stage.

Core Analytical Workflow

The foundational analysis pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into biologically interpretable results through sequential processing steps:

Quality Control and Filtering: Removal of low-quality cells based on metrics like total counts, detected genes, and mitochondrial percentage, which often indicate compromised viability or sequencing quality. For drug treatment studies, consistent filtering thresholds across conditions are essential to avoid technical biases [8].

Normalization and Batch Correction: Adjustment for technical variations in sequencing depth and composition, followed by integration of datasets across multiple batches or experimental runs. Methods like SCTransform and ComBat effectively remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signals, including drug response signatures [10].

Dimensionality Reduction: Projection of high-dimensional gene expression data into lower-dimensional spaces using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) to visualize and explore cellular heterogeneity [10].

Clustering and Cell Type Annotation: Identification of distinct cellular populations using graph-based clustering algorithms (Louvain, Leiden), followed by annotation based on canonical marker genes or reference datasets. In pharmacological contexts, this enables detection of treatment effects on specific cell types [10].

Differential Expression Analysis: Statistical identification of genes with significant expression changes between conditions (e.g., treated vs. control) using methods like MAST or DESeq2 that account for the unique characteristics of single-cell data [10].

Advanced Analytical Approaches for Pharmacology

Beyond the standard workflow, several specialized analytical techniques offer particular value for pharmacological research:

Trajectory Inference and Pseudotime Analysis: Reconstruction of dynamic cellular processes like differentiation or treatment response along inferred temporal trajectories. Tools like Monocle3 and PAGA can model how drug treatments alter cellular state transitions, revealing mechanisms of action and resistance development [10].

Gene Regulatory Network Analysis: Inference of transcription factor activities and regulatory relationships from scRNA-seq data, identifying key regulators affected by drug treatments that might represent novel therapeutic targets or resistance mechanisms [10].

Machine Learning for Drug Response Prediction: Application of random forest, deep learning, and other ML models to predict treatment outcomes based on single-cell profiles. These approaches can identify predictive biomarkers and molecular signatures of drug sensitivity [10].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents a particularly promising frontier, with demonstrated capabilities in pattern recognition across large, complex single-cell datasets to uncover subtle but therapeutically relevant cellular responses [10] [19].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolution of single-cell technologies continues to accelerate, driven by both methodological innovations and expanding applications in pharmacological research. Several emerging trends are poised to further transform chemogenomics research in the coming years:

Multi-omic Integration will increasingly become the standard approach for comprehensive drug profiling, with technologies enabling simultaneous measurement of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic features from the same single cells [1] [19]. This holistic view will provide unprecedented insights into coordinated molecular responses to therapeutic interventions, revealing complex mechanism-of-action networks rather than isolated targets.

Spatial Multi-omics represents another frontier, combining spatial context with multi-layer molecular profiling to preserve tissue architecture while analyzing drug effects. The anticipated growth in 3D spatial studies will enable researchers to comprehensively assess cellular interactions within native tissue microenvironments and their influence on treatment efficacy [22] [19]. This is particularly relevant for solid tumors and complex tissues where cellular neighborhood effects significantly impact drug response.

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Analytics will play an increasingly central role in extracting biological insights from the enormous datasets generated by single-cell technologies. As noted by industry leaders, "AI and machine learning will have a profound impact on our industry in helping to accelerate biomarker discoveries, identify new pathways for drug development and offer a more defined path towards precision medicine" [19]. The training of AI models on large, application-specific datasets will provide critical insights for researchers to dramatically accelerate biomarker discovery and guide development of more effective, targeted therapies.

The ongoing technology commoditization and cost reduction will further democratize access to single-cell approaches, moving them beyond specialized core facilities to become routine tools in pharmaceutical research and development. Sequencing cost reductions—with the $100 genome now in sight—combined with streamlined workflows will enable more widespread adoption across the drug discovery pipeline [25] [19].

In conclusion, single-cell technologies have evolved from specialized research tools to essential components of modern pharmacological research, providing unprecedented resolution into cellular heterogeneity and its implications for therapeutic development. As these technologies continue to mature and integrate with advanced computational approaches, they promise to accelerate the development of more effective, precisely targeted therapies while improving the efficiency and success rates of the drug discovery process. For researchers in chemogenomics and drug development, mastery of these single-cell approaches is no longer optional but essential for remaining at the forefront of therapeutic innovation.

Single-cell next-generation sequencing (scNGS) technologies have revolutionized chemogenomics research by enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity and its profound impact on drug response. Unlike bulk sequencing methods that average signals across cell populations, single-cell approaches reveal the distinct transcriptomic, genomic, and epigenomic states of individual cells within a complex biological sample [26] [27]. This resolution is critical for understanding the varied mechanisms of drug action, resistance, and toxicity across different cell types and states in a population. The integration of these technologies into the drug discovery pipeline provides unprecedented insights into cellular responses to chemical perturbations, accelerating the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers [28] [27]. This application note outlines core applications and provides detailed protocols for implementing single-cell technologies in drug discovery workflows.

Core Applications of Single-Cell NGS in Drug Discovery

The application of single-cell technologies spans the entire drug discovery and development workflow, from initial target identification to clinical trials. The table below summarizes the core applications, their descriptions, and key technological platforms.

Table 1: Core Applications of Single-Cell NGS in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Description | Key Single-Cell Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification & Validation | Discovers novel drug targets by identifying key genes and pathways driving disease in specific cell subpopulations. | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, Multiome (scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) |

| Pharmacotranscriptomic Profiling | Elucidates heterogeneous transcriptional responses to drug treatments at single-cell resolution, defining mechanisms of action (MoA). | Multiplexed scRNA-seq (e.g., with live-cell barcoding) [14] |

| Cell Cycle State Analysis | Deeply phenotypes how drugs perturb canonical and non-canonical cell cycle states using multiplexed protein measurements. | Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) with expanded antibody panels [29] |

| Drug Resistance Mechanisms | Uncovers pre-existing or acquired rare cell subpopulations and transcriptional programs that confer resistance to therapies. | scRNA-seq, Single-cell DNA sequencing |

| Biomarker Discovery | Identifies expression signatures specific to cell types or states that predict drug sensitivity, resistance, or patient stratification. | scRNA-seq, CITE-seq (RNA + surface protein) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Multiplexed Single-Cell RNA-Seq Pharmacotranscriptomic Profiling

This protocol enables high-throughput screening of transcriptional drug responses by combining live-cell barcoding with scRNA-seq, allowing for the pooling and simultaneous processing of up to 96 drug treatment conditions [14].

Table 2: Key Steps for Pharmacotranscriptomic Profiling

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Preparation & Drug Treatment | Plate live epithelial cancer cells (e.g., primary HGSOC cells) and treat with a library of compounds for 24 hours. Use DMSO as a control. | Drug concentration should be above the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) to elicit a transcriptional response. |

| 2. Live-Cell Barcoding (Cell Hashing) | Label cells in each well with unique pairs of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (Hashtag Oligos, HTOs) against surface markers (e.g., B2M, CD298). | Antibody concentration and incubation time must be optimized to ensure specific binding and minimal cell loss. |

| 3. Cell Pooling & Library Preparation | Pool all barcoded cells into a single suspension. Proceed with standard droplet-based single-cell 3' RNA-seq library preparation (e.g., 10x Genomics). | Ensure cell viability >80% and target a recovery of 100-150 cells per treatment condition after quality control. |

| 4. Sequencing & Data Analysis | Sequence libraries to a depth of ~20,000 reads per cell. Demultiplex cells by HTOs and transcriptomes using tools like Seurat or Scanpy for downstream analysis. | Bioinformatics analysis includes gene set variation analysis (GSVA) to evaluate activity of biological processes post-treatment. |

Protocol for a Deep Single-Cell Mass Cytometry Approach to Cell Cycle

This protocol uses an expanded panel of metal-tagged antibodies to deeply phenotype the diversity of cell cycle states at the single-cell level, capturing both canonical and non-canonical states beyond standard phase definitions [29].

Table 3: Key Steps for Deep Cell Cycle Phenotyping

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Preparation & Stimulation | Culture suspension/adherent cell lines or primary cells (e.g., human T cells). Apply cell cycle perturbations if needed (e.g., CDK inhibitors). | Include a DNA label (IdU) for 30-60 minutes to mark S-phase cells prior to fixation. |

| 2. Cell Staining & Barcoding | Fix and permeabilize cells. Stain with a pre-optimized panel of 48 metal-tagged antibodies against CC-related molecules. Use palladium barcoding for multiplexing. | Antibody panel should include "minimal" (checkpoint proteins), "core" (with DNA content), and "complete" (with chromatin state) targets. |

| 3. Data Acquisition on CyTOF | Acquire single-cell data on a mass cytometer (CyTOF). | Use event length, DNA intercalators (e.g., Ir), and standard gating to remove doublets, debris, and dead cells during acquisition. |

| 4. High-Dimensional Data Analysis | Analyze data using dimensionality reduction (e.g., PHATE) and graph-based approaches to quantify CC state diversity. | Compare molecular patterns across cell lines and perturbations to identify aberrant, non-canonical CC states. |

Protocol for scCLEAN: Enhanced scRNA-seq Sensitivity

This protocol describes single-cell CRISPRclean (scCLEAN), a method to enhance the detection of low-abundance transcripts in scRNA-seq libraries by using CRISPR/Cas9 to remove highly abundant and uninformative molecules, thereby redistributing sequencing reads [30].

Table 4: Key Steps for scCLEAN Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Library Preparation & Guide RNA Design | Generate a full-length cDNA library from single cells (e.g., using 10x Genomics). Design sgRNA arrays against targets. | Targets include genomic-derived intervals, rRNAs, and a pre-defined panel of 255 low-variance, protein-coding genes (NVGs). |

| 2. CRISPR/Cas9 Cleavage | Incubate the dsDNA sequencing library with Cas9 protein and the pooled sgRNA array to cleave target sequences. | Optimization of Cas9 concentration and digestion time is crucial for efficient cleavage without excessive library degradation. |

| 3. Library Purification & Sequencing | Purify the digested library to remove the cleaved fragments. Proceed with standard sequencing. | Use solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads for size selection and purification. |

| 4. Data Analysis | Process sequencing data through standard scRNA-seq pipelines (e.g., Cell Ranger). | Expect a ~2-fold increase in reads aligning to the informative (non-targeted) transcriptome, enhancing signal-to-noise ratio. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of single-cell technologies in drug discovery relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for the featured applications.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Drug Discovery

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hashtag Oligos (HTOs) | Antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates that label live cells from different experimental conditions (e.g., drug treatments) with unique barcodes prior to pooling. | Multiplexed pharmacotranscriptomic screens [14]. |

| Expanded Cell Cycle MC Panel | A pre-configured set of 48 metal-tagged antibodies targeting cyclins, phospho-proteins, DNA licensing factors, and cell cycle regulators. | Deep phenotyping of cell cycle states and drug-induced aberrancies via Mass Cytometry [29]. |

| scCLEAN sgRNA Array | A pooled library of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) designed to target and remove highly abundant ribosomal, mitochondrial, and non-variable gene transcripts from scRNA-seq libraries. | Enhancing detection sensitivity of low-abundance, biologically relevant transcripts in any scRNA-seq library [30]. |

| Viability Stains (e.g., Live/Dead Fixable Stains) | Fluorescent dyes that distinguish live cells from dead cells and debris during fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), critical for generating high-quality cell suspensions. | Sample preparation for all single-cell protocols requiring viable single-cell suspensions [31]. |

| Palladium Barcoding Kits | Stable metal-tagged reagents that allow unique labeling of individual samples, enabling sample multiplexing and reduction of technical variation in Mass Cytometry experiments. | Multiplexing up to 20+ samples in a single CyTOF run for robust comparative analysis [29]. |

From Bench to Dataset: sc-NGS Workflows for Target ID, Validation, and Mechanism Elucidation

This application note details a high-throughput pharmacotranscriptomic pipeline that integrates multiplexed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) with live-cell barcoding for the systematic identification of drug response mechanisms at single-cell resolution. The protocol is presented within the broader context of applying single-cell next-generation sequencing (NGS) in chemogenomics research to deconvolute cellular heterogeneity and identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities.

In chemogenomics and drug discovery, a major bottleneck has been the notable variability in drug responses due to cancer heterogeneity, which imposes genetic, transcriptomic, epigenetic, and phenotypic changes at the level of individual patient cells [14]. High-throughput pharmacotranscriptomic profiling addresses this by moving beyond bulk cell viability assays to characterize the full spectrum of transcriptional responses induced by compound libraries across heterogeneous cell populations [14] [11]. The workflow described herein leverages live-cell barcoding to physically multiplex up to 96 drug-treated samples in a single scRNA-seq run, enabling the cost-efficient and time-efficient generation of perturbation signatures from primary patient-derived cells, a capability critical for advancing personalized oncology [14].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the core pipeline for high-throughput pharmacotranscriptomic screening.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Cell Preparation and Drug Treatment