Scaffold Analysis in Chemogenomic Libraries: Strategies for Enhancing Diversity and Drug Discovery Success

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold analysis and its critical role in evaluating and enhancing the diversity of chemogenomic libraries for modern drug discovery.

Scaffold Analysis in Chemogenomic Libraries: Strategies for Enhancing Diversity and Drug Discovery Success

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of scaffold analysis and its critical role in evaluating and enhancing the diversity of chemogenomic libraries for modern drug discovery. It covers foundational concepts of chemical scaffolds and their importance in navigating chemical space, explores traditional and AI-driven methodological approaches for analysis, addresses common limitations and optimization strategies in phenotypic screening, and validates these approaches through comparative assessments of library design strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements to guide the construction of more effective, target-addressed screening libraries, ultimately improving hit-finding and lead optimization outcomes.

The Foundation of Chemical Diversity: Understanding Scaffolds in Chemogenomic Libraries

In chemogenomic library diversity research, the systematic classification of chemical structures is paramount. The concept of a molecular scaffold—the core structure of a molecule—provides a foundational framework for organizing chemical space, analyzing screening data, and designing targeted libraries [1]. Scaffold analysis allows researchers to move beyond considering individual compounds to evaluating entire structural classes, enabling the identification of privileged structures with desired bioactivity and the assessment of library coverage and diversity [2]. This application note details the primary methodologies for defining chemical scaffolds, from the foundational Murcko framework to the hierarchical Scaffold Tree, providing standardized protocols for their application in chemogenomic library research.

Defining Scaffold Types: Concepts and Applications

The definition of a molecular scaffold can vary from concrete structural representations to abstract hierarchical classifications, each serving distinct purposes in cheminformatics and drug discovery.

Murcko Frameworks: The Foundational Approach

Introduced by Bemis and Murcko in 1996, the Murcko framework is one of the most widely used scaffold representations [3] [2]. It systematically dissects a molecule into four components: ring systems, linkers, side chains, and the resulting Murcko framework, which is the union of the ring systems and linkers [2]. This approach effectively captures the core topology of a molecule by removing all terminal side chains, preserving only the cyclic components and the chains that connect them [1].

Advanced Hierarchical Representations

To address limitations of the Murcko approach, more advanced hierarchical representations have been developed:

Scaffold Trees: Schuffenhauer et al. proposed a systematic methodology that iteratively prunes rings one by one based on a set of 13 chemical prioritization rules until only one ring remains [2]. This creates a deterministic, tree-like hierarchy where single-ring scaffolds form the roots and more complex scaffolds are placed at higher levels [1] [4]. The process preserves atoms connected via double bonds to ring or linker atoms to maintain correct hybridization [1].

Scaffold Networks: In contrast to the single-parent approach of Scaffold Trees, scaffold networks exhaustively enumerate all possible parent scaffolds generated through iterative ring removal without applying prioritization rules [1]. This generates multi-parent relationships between nodes, creating a more comprehensive network representation that can identify more active substructural motifs in screening data [4].

HierS Clustering: The Hierarchical Scaffold Clustering (HierS) approach uses a scaffold definition similar to Murcko frameworks but includes atoms directly attached to rings and linkers via multiple bonds [4]. It builds hierarchy by generating all smaller scaffolds resulting from stepwise removal of ring systems, linking parent and child scaffolds through substructure relationships [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Scaffold Definitions

| Scaffold Type | Key Features | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murcko Framework | Union of rings and connecting linkers; removal of terminal side chains [2] | Initial scaffold analysis; drug-likeness assessment [2] | Simple, intuitive interpretation; easily computable | Ignores non-cyclic molecules; small structural changes yield different scaffolds |

| Scaffold Tree | Hierarchical tree via iterative ring removal using 13 prioritization rules [1] [2] | Systematic classification; visualizing scaffold universe; identifying characteristic cores [4] | Deterministic, unique classification; dataset-independent; chemically intuitive | Limited exploration of possible parent scaffolds; may miss some active substructures |

| Scaffold Network | Exhaustive enumeration of all parent scaffolds without prioritization rules [1] | Identifying active substructural motives in HTS data; virtual scaffold generation [1] | More comprehensive exploration of scaffold space; identifies more active scaffolds | Can become large and complex; difficult to visualize completely |

| HierS Clustering | Includes atoms attached via multiple bonds; removes ring systems (not individual rings) [4] | Scaffold clustering; classification of chemical libraries [4] | Considers multiple bonds; includes non-cyclic molecules | Multi-class assignment; ring systems not split into single rings |

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Analysis

Protocol 1: Generating Murcko Frameworks

Principle: Convert molecular structures to their core frameworks by removing all terminal side chains and preserving ring systems and connecting linkers [2].

Materials:

- Input: Molecular structures in SDF or SMILES format

- Software: RDKit, Pipeline Pilot, or the ScaffoldGraph library [4]

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Load molecular structures and standardize representation (remove duplicates, neutralize charges, generate canonical tautomers).

- Ring System Identification: Identify all cyclic systems in the molecule using a ring perception algorithm.

- Linker Detection: Identify all atoms and bonds forming the shortest paths between ring systems.

- Side Chain Removal: Remove all terminal atoms and bonds not part of rings or linkers.

- Framework Output: Generate the resulting Murcko framework as a canonical SMILES string or molecular graph.

Applications in Chemogenomics: Murcko frameworks provide a rapid initial assessment of scaffold diversity in large compound libraries, enabling researchers to identify over-represented or under-represented core structures in screening collections [2].

Protocol 2: Constructing Scaffold Trees

Principle: Iteratively decompose molecular scaffolds through prioritized ring removal to create a hierarchical classification [1] [2].

Materials:

- Input: Molecular structures in SDF or SMILES format

- Software: ScaffoldGraph library, Scaffold Hunter, or CDK-based implementations [1] [4]

Procedure:

- Initial Scaffold Extraction: Generate the Murcko framework for each molecule, preserving atoms connected via double bonds.

- Ring Perception: Identify all rings using a smallest set of smallest rings (SSSR) approach.

- Iterative Ring Removal:

- Identify removable terminal rings (whose removal maintains scaffold connectivity)

- Apply prioritization rules to select one ring for removal:

- Prioritize aliphatic over aromatic rings

- Remove smaller rings before larger ones

- Remove rings with fewer heteroatoms first

- Apply additional rules until one ring remains [1]

- Tree Construction: Link each child scaffold to its single parent scaffold formed by ring removal.

- Hierarchy Assignment: Assign hierarchy levels from Level 0 (single ring) to Level n (original framework).

Applications in Chemogenomics: Scaffold Trees enable systematic organization of chemogenomic libraries by structural relationship, facilitating the identification of structure-activity relationships across scaffold hierarchies and guiding library enrichment strategies [1] [4].

Protocol 3: Building Scaffold Networks

Principle: Exhaustively generate all possible parent scaffolds through iterative ring removal without prioritization rules, creating a network of relationships [1].

Materials:

- Input: Molecular structures in SDF or SMILES format

- Software: ScaffoldGraph library or custom implementations [4]

Procedure:

- Initial Scaffold Extraction: Generate comprehensive scaffolds including all ring systems and linkers.

- Exhaustive Ring Removal:

- Generate all possible sub-scaffolds by removing each removable ring individually

- Continue process recursively until only single rings remain

- Retain all scaffold relationships without filtering

- Network Construction: Create directed graph with edges from child to all parent scaffolds.

- Virtual Scaffold Identification: Note scaffolds generated through dissection that don't appear as original molecular frameworks.

Applications in Chemogenomics: Scaffold Networks are particularly valuable for analyzing high-throughput screening data, as they can identify substructural motifs associated with bioactivity that might be missed by more restrictive tree-based approaches [1].

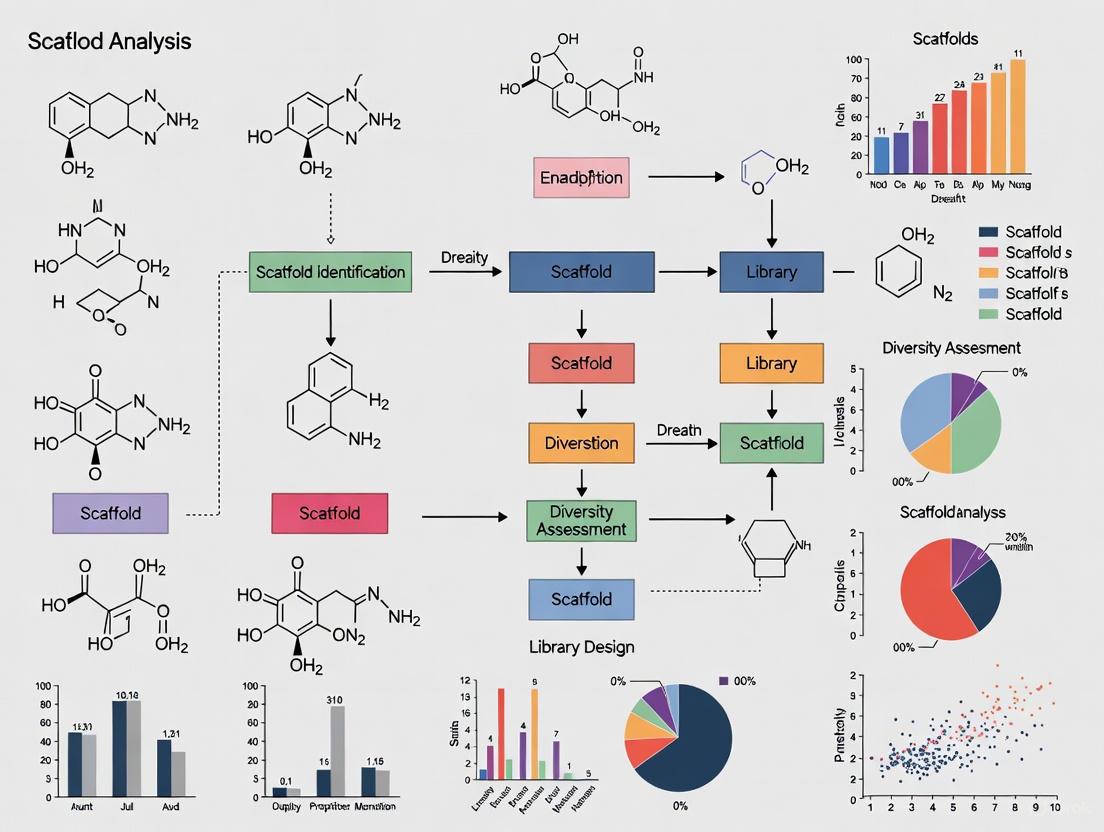

Visualization of Scaffold Analysis Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decision points in selecting appropriate scaffold analysis methods based on research objectives:

Scaffold Analysis Method Selection Based on Research Objectives

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Essential Tools for Scaffold Analysis in Chemogenomic Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Scaffold Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| ScaffoldGraph | Open-source Python library [4] | Generation and analysis of molecular scaffold networks and trees | Computes Scaffold Trees, Scaffold Networks, and HierS networks; supports parallel processing of large datasets |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Chemical pattern matching, molecular representation, and descriptor calculation | Fundamental operations for molecular standardization, ring perception, and scaffold manipulation |

| Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) | Open-source Java library | Cheminformatics algorithms and data structures | Provides the foundation for the Scaffold Generator implementation with multiple framework definitions [1] |

| Scaffold Hunter | Software platform with graphical interface [5] [4] | Interactive exploration of chemical space using scaffold hierarchies | Visualization and navigation of scaffold trees and networks; supports chemical and biological data integration |

| Pipeline Pilot | Commercial scientific workflow platform | Automated data pipelining and analysis | Generate Fragments component for creating multiple scaffold representations (Murcko, RECAP, etc.) [2] |

| ChEMBL Database | Public domain database of bioactive molecules [5] | Curated bioactivity, molecule, target, and drug data | Source of annotated compounds for building scaffold-activity relationships and context-dependent analysis |

Application in Chemogenomic Library Design and Analysis

The strategic application of scaffold analysis methods directly enhances chemogenomic library design and diversity assessment:

Library Diversity Quantification

Scaffold-based diversity analysis employs metrics such as scaffold counts and cumulative scaffold frequency plots (CSFPs) to evaluate library composition [2]. The PC50C metric—defined as the percentage of scaffolds that represent 50% of molecules in a library—provides a standardized measure for comparing scaffold diversity across different screening collections [2].

Privileged Substructure Identification

Scaffold Trees and Networks facilitate the identification of privileged substructures—molecular frameworks that appear frequently in compounds active against multiple target classes [1]. By mapping bioactivity data onto scaffold hierarchies, researchers can distinguish between truly promiscuous scaffolds and those with selective target profiles, informing target-focused library design [1] [4].

Virtual Library Design and Scaffold Hopping

Scaffold-based generative models enable the design of novel compounds retaining desired core structures while optimizing peripheral properties [6]. These approaches accept a molecular scaffold as input and extend it by sequentially adding atoms and bonds, guaranteeing that generated molecules contain the scaffold—a crucial capability for scaffold-hopping strategies in lead optimization [6].

The systematic application of scaffold analysis methods—from fundamental Murcko frameworks to sophisticated Scaffold Trees and Networks—provides an essential foundation for chemogenomic library diversity research. By implementing the standardized protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can quantitatively assess scaffold diversity, identify privileged substructures with desired bioactivity, and design targeted screening libraries with optimal coverage of chemical space. The integration of these scaffold-centric approaches continues to advance the efficiency and effectiveness of modern drug discovery pipelines.

In modern drug discovery, the structural core of a molecule, known as its scaffold, fundamentally determines its interaction with biological systems. Scaffold diversity refers to the variety of these core structures within a chemical library. A diverse scaffold portfolio is critical for broad biological coverage because different scaffolds interact with distinct protein families and biological pathways. The chemogenomic approach, which systematically studies the interaction of chemical compounds with the proteome, relies on scaffold diversity to efficiently explore the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) and link structural variety to phenotypic outcomes [7]. A library rich in scaffold diversity increases the probability of finding hits for novel targets and reduces the risk of attrition due to narrow structure-activity relationships.

Quantitative Assessment of Scaffold Diversity

A comprehensive assessment of scaffold diversity requires multiple metrics to provide a "global diversity" perspective, as each metric captures different aspects of structural variation [8]. The most informative quantitative measures are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Scaffold Diversity

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Count | Total number of unique molecular frameworks (cyclic and acyclic) in a library. | Higher counts indicate greater structural variety. | Initial library profiling and comparison. |

| Singleton Fraction | Proportion of scaffolds that appear only once in the library. | A high fraction suggests high novelty and diversity. | Assessing exploration of new chemical space. |

| Cyclic System Recovery (CSR) Curve | Plot of the cumulative fraction of compounds recovered versus the cumulative fraction of scaffolds. | Curves that rise slowly indicate higher diversity (more scaffolds needed to cover the library). | Visualizing and comparing the distribution of scaffolds across libraries. |

| Area Under the CSR Curve (AUC) | Quantitative summary of the CSR curve. | Low AUC values point to high scaffold diversity. | Ranking libraries by scaffold diversity. |

| F50 Value | The fraction of scaffolds required to recover 50% of the compounds in a library. | Low F50 values indicate high scaffold diversity. | Complementary metric to AUC. |

| Shannon Entropy (SE) | Measures the distribution of compounds across scaffolds, considering both the number of scaffolds and their relative abundance. | Higher SE indicates a more even distribution of compounds across scaffolds. | Evaluating library balance and focus. |

| Scaled Shannon Entropy (SSE) | Normalizes SE to a 0-1 scale based on the number of scaffolds. | Value of 1 indicates maximum diversity (perfect even distribution). | Comparing diversity across libraries of different sizes. |

These metrics reveal that libraries can be diverse in different ways. For instance, a library might have a high scaffold count but a low SSE if most compounds are concentrated on a few popular scaffolds. Therefore, a combination of these metrics, as utilized in Consensus Diversity Plots (CDPs), provides the most robust evaluation [8].

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Diversity Analysis

Protocol 1: Core Scaffold Generation and Enumeration

This protocol details the process for extracting and classifying molecular scaffolds from a compound library.

1. Purpose: To generate a standardized set of molecular scaffolds from a raw structural data set (e.g., SDF or SMILES files) for subsequent diversity analysis.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Tool: ScaffoldHunter [5].

- Function: A software specifically designed for the hierarchical decomposition of molecules into scaffolds and fragments according to deterministic rules.

3. Procedure: A. Input Preparation: Load the curated chemical library into ScaffoldHunter. Ensure data curation (e.g., salt removal, standardization of tautomers) is complete. B. Scaffold Decomposition: Execute the stepwise fragmentation algorithm: i. Remove all terminal side chains, preserving double bonds directly attached to a ring. ii. Iteratively remove one ring at a time based on predefined rules until only a single ring remains. C. Data Output: The software generates a hierarchical tree of scaffolds for each molecule, allowing for analysis at different levels of abstraction. The set of all unique top-level scaffolds constitutes the primary data for diversity metrics.

4. Analysis: Calculate the key metrics from Table 1 (Scaffold Count, Singleton Fraction) from the generated list of top-level scaffolds.

Protocol 2: Generating a Consensus Diversity Plot (CDP)

This protocol describes how to integrate multiple diversity metrics into a single, powerful visualization [8].

1. Purpose: To visually compare the global diversity of multiple compound libraries by simultaneously considering scaffold diversity, fingerprint diversity, and property diversity.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Platform: The online CDP tool (https://consensusdiversityplots-difacquim-unam.shinyapps.io/RscriptsCDPlots/) [8].

- Function: A specialized web application for constructing CDPs using pre-defined or user-uploaded data.

3. Procedure: A. Data Preparation: For each library to be compared, calculate: i. Y-axis metric: A measure of scaffold diversity (e.g., SSE or AUC from CSR curves). ii. X-axis metric: A measure of fingerprint diversity (e.g., average Tanimoto similarity using MACCS keys). iii. Color scale metric: A measure of property diversity (e.g., Euclidean distance based on a profile of physicochemical properties). B. Data Input: Upload a table containing the calculated metrics for each library to the CDP web platform. C. Plot Generation: The application automatically generates a 2D scatter plot (the CDP), where each point represents a library. The plot is divided into quadrants to classify libraries as high/low in fingerprint and scaffold diversity.

4. Analysis: Interpret the CDP to identify libraries with balanced diversity. For example, a library positioned in the quadrant for high scaffold diversity and high fingerprint diversity is optimally positioned for broad phenotypic screening [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data integration process for constructing a CDP.

The Link Between Scaffolds and Biological Coverage

The primary value of scaffold diversity lies in its direct connection to biological and phenotypic coverage. A diverse set of scaffolds increases the likelihood of modulating a wider range of biological targets and pathways.

Maximizing Target Space: Even the most comprehensive chemogenomics libraries cover only a fraction of the human genome. For example, a well-annotated library might interrogate 1,000-2,000 targets out of over 20,000 protein-coding genes [9]. A scaffold-diverse library is engineered to maximize the coverage of this "druggable" genome, ensuring that multiple, distinct target classes (e.g., kinases, GPCRs, ion channels) are represented by specific chemotypes. This is crucial for phenotypic screening, where the molecular target is unknown at the outset [5].

Enhancing Phenotypic Deconvolution: In Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD), a key challenge is "deconvoluting" the mechanism of action after a hit is identified. If a hit compound has a common, well-studied scaffold, its target may be easier to hypothesize. A library with high scaffold diversity increases the probability that a screening hit is biologically novel, but it also necessitates robust methods for target identification, such as the integration of morphological profiling data from assays like Cell Painting into system pharmacology networks [5].

The relationship between scaffold diversity, target coverage, and phenotypic outcomes can be visualized as a connected network, where increasing structural variety directly enables broader biological exploration.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Scaffold Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Scaffold Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| ScaffoldHunter [5] | Software | Hierarchical decomposition of molecules into scaffolds and fragments for diversity analysis. |

| RDKit [10] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and handling molecular representations (e.g., SMILES). |

| ChEMBL [5] [7] | Public Database | Source of biologically annotated molecules for benchmarking and enriching library design. |

| Consensus Diversity Plot (CDP) [8] | Online Tool | Visualizing the global diversity of compound libraries using multiple, simultaneous metrics. |

| Cell Painting Assay [5] | Phenotypic Profiling | Providing high-content morphological data to link scaffold-induced perturbations to biological outcomes. |

| Neo4j [5] | Graph Database | Integrating diverse data (drug-target-pathway-disease) into a network pharmacology model for analysis. |

Scaffold diversity is not merely a numerical descriptor of a compound library; it is a fundamental strategic asset in chemogenomics and phenotypic drug discovery. A rigorous, multi-metric approach to its quantification—using scaffold counts, CSR curves, Shannon entropy, and especially integrative tools like Consensus Diversity Plots—is essential for designing libraries with broad biological coverage. By deliberately maximizing scaffold diversity, researchers can create more effective screening collections capable of illuminating novel biology and yielding first-in-class therapeutic candidates.

In modern drug discovery, the concept of "chemical space" is paramount for understanding the structural diversity and potential of compound libraries. Scaffold analysis serves as a primary method for navigating this space, providing a systematic approach to deconstructing molecules into their core structural components to map and quantify diversity [2]. For researchers developing chemogenomic libraries, which aim to cover a broad spectrum of biological targets, this analysis is indispensable for ensuring comprehensiveness and avoiding redundancy [11].

This Application Note details the practical application of scaffold analysis to assess chemical space coverage. It provides a defined protocol for conducting this analysis and presents quantitative data on library diversity, enabling researchers to make informed decisions in library design and selection for phenotypic screening and target deconvolution.

Protocol: Hierarchical Scaffold Analysis for Library Characterization

This protocol outlines a stepwise procedure for performing a hierarchical scaffold analysis to characterize the diversity of a chemical library. The method is based on established practices in cheminformatics [11] [2].

Materials and Software Requirements

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Software | KNIME, Pipeline Pilot, or Python/R | Data processing workflow management |

| Scaffold Hunter [11] or MOE sdfrag [2] | Hierarchical scaffold generation | |

| Neo4j or Similar Graph Database | Network visualization and analysis [11] | |

| Input Data | Chemical Library | SDF or SMILES file of the compound collection |

| Computing | Workstation | Standard computer for libraries <1M compounds |

Experimental Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Standardization Begin by loading the chemical library (e.g., in SDF or SMILES format) into the chosen workflow manager. Standardize all molecular structures by removing duplicates, neutralizing charges, and stripping salts to ensure a consistent basis for comparison [2].

Step 2: Hierarchical Scaffold Generation Process the standardized molecules using scaffold analysis software (e.g., Scaffold Hunter) [11]. The algorithm prunes terminal side chains and removes one ring at a time based on a set of prioritization rules until only a single ring remains [11] [2]. This creates a hierarchical tree of scaffolds for each molecule, from the original molecular structure (Level n) down to a single ring (Level 0).

Step 3: Data Integration and Analysis Export the generated scaffolds at each level. The Murcko framework (equivalent to Level n-1) is often a primary focus for diversity analysis [2]. Integrate the molecule-scaffold relationships with other relevant data, such as bioactivity or pathway information, into a graph database like Neo4j for advanced querying and systems pharmacology analysis [11].

Step 4: Diversity Quantification and Visualization Calculate key diversity metrics, including the total number of unique scaffolds and the cumulative scaffold frequency. Visualize the scaffold distribution using Tree Maps or Similarity-Activity Trailing (SimilACTrail) maps to identify clusters and gaps in the chemical space [12] [2].

Diagram 1: Hierarchical scaffold analysis workflow for assessing chemical space.

Results and Data Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Scaffold Diversity

Analysis of standardized subsets from several purchasable compound libraries reveals significant differences in their scaffold diversity, as shown in Table 1. The PC50C metric—the percentage of unique scaffolds required to cover 50% of the molecules in a library—is a key indicator of diversity, where a lower value indicates a more diverse collection [2].

Table 1: Scaffold diversity metrics for selected compound libraries (standardized subsets) [2]

| Compound Library | Number of Unique Murcko Frameworks | PC50C Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Chembridge | 7,821 | 2.5 |

| ChemicalBlock | 7,559 | 2.7 |

| Mcule | 7,312 | 2.8 |

| TCMCD | 6,901 | 3.1 |

| VitasM | 7,190 | 2.9 |

| Enamine | 6,845 | 3.2 |

| Maybridge | 6,112 | 4.0 |

Application in Phenotypic Screening and Toxicology

Table 2: Key metrics from scaffold-driven predictive toxicology model [12]

| Modeling Parameter | Result / Feature |

|---|---|

| Dataset | 299 Pesticides (acute toxicity in rainbow trout) |

| Analytical Method | Structure-Similarity Activity Trailing (SimilACTrail) map |

| Key Structural Drivers | Molecular polarizability, Lipophilicity |

| Model Performance | >92% prediction reliability for 2000+ external pesticides |

| Singleton Ratio in Clusters | 80.0% - 90.3% |

Scaffold analysis, combined with machine learning, enables the prediction of compound toxicity based on structural features. A study on pesticide toxicity in rainbow trout used a SimilACTrail map to explore chemical space, identifying high structural uniqueness with singleton ratios of 80.0–90.3% in clusters [12]. The model achieved high predictive reliability, identifying key features like polarizability and lipophilicity as primary drivers of acute toxicity [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Scaffold Analysis |

|---|---|

| Scaffold Hunter [11] | Open-source software for generating hierarchical scaffold trees from a set of molecules by iteratively pruning side chains and rings. |

| ChEMBL Database [11] [13] | A manually curated, open-access database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for bioactivity data and target annotation. |

| Neo4j [11] | A graph database platform used to integrate drug-target-pathway-disease relationships and scaffold data into a unified network pharmacology model. |

| iSIM Framework [13] | A computational tool that efficiently calculates the intrinsic similarity (or diversity) of large compound libraries using O(N) complexity, bypassing the need for pairwise comparisons. |

| Murcko Framework [2] [13] | A standard method for defining a molecular scaffold as the union of all ring systems and linkers in a molecule, enabling consistent structural comparisons. |

Discussion

The results confirm that scaffold analysis is a powerful and versatile tool for mapping the comprehensiveness of chemical libraries. The quantitative data reveals that libraries from different vendors possess distinct diversity profiles, which can directly impact the success of a screening campaign [2]. Selecting a library with low PC50C values, such as Chembridge or ChemicalBlock, increases the probability of encountering novel chemotypes during screening.

The application of these methods extends beyond simple diversity assessment. In phenotypic drug discovery, integrating scaffold data with morphological profiles from assays like Cell Painting in a network pharmacology framework facilitates the deconvolution of a compound's mechanism of action by linking structural features to observed phenotypic outcomes and biological pathways [11]. Furthermore, in predictive toxicology, scaffold-centric models like q-RASAR provide interpretable and reliable predictions, supporting regulatory decision-making [12].

Diagram 2: Integrative network pharmacology linking chemical scaffolds to phenotypic outcomes.

Scaffold hopping, also referred to as lead hopping or core hopping, is a fundamental strategy in medicinal chemistry and computer-aided drug design aimed at identifying novel bioactive compounds by modifying the central core structure of a known active molecule [14] [15]. The primary objective is to replace a molecular scaffold with an alternative chemical structure while preserving the spatial orientation of key substituents responsible for biological activity [15]. This approach directly supports chemogenomic library diversity research by systematically generating structurally novel chemotypes with maintained or improved biological function, thereby expanding the accessible chemical space around a biological target of interest.

The conceptual foundation of scaffold hopping was formally introduced in 1999 by Schneider et al. as a technique to identify isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones [14]. This definition emphasizes two critical components: different core structures and similar biological activities relative to the parent compounds [16]. Although this may appear to conflict with the traditional similarity-property principle, scaffold hopping operates on the principle that ligands binding the same protein pocket must share complementary pharmacophore features—similar shape and electrostatic potential—even when their underlying chemical architectures differ substantially [14] [16]. The technique has become an indispensable tool for addressing multiple drug discovery challenges, including achieving intellectual property novelty, overcoming physicochemical or pharmacokinetic liabilities associated with an existing scaffold, and improving metabolic stability or solubility profiles [14] [15].

Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

Scaffold hopping strategies can be systematically categorized based on the degree and nature of structural modification applied to the original molecular framework. These classifications help medicinal chemists select appropriate strategies for specific discovery objectives, ranging from conservative modifications that maintain close synthetic analogy to transformative changes that generate entirely novel chemotypes.

Table 1: Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

| Hop Category | Structural Transformation | Degree of Novelty | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° Hop: Heterocycle Replacement | Swapping or replacing atoms within a ring system (e.g., C, N, O, S) [14] | Low | Fine-tuning electronic properties, solubility, and synthetic accessibility while maintaining core geometry [14] |

| 2° Hop: Ring Opening/Closure | Breaking cyclic bonds to increase flexibility or forming new rings to reduce conformational entropy [14] | Medium | Optimizing molecular flexibility/rigidity to improve binding entropy, potency, or absorption [14] [16] |

| 3° Hop: Peptidomimetics | Replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties to mimic bioactive peptide structures [14] | Medium-High | Converting endogenous peptides into metabolically stable, bioavailable drug-like molecules [14] |

| 4° Hop: Topology-Based | Modifying the overall molecular topology or shape while preserving key pharmacophore elements [16] | High | Discovering entirely novel chemotypes with significant structural differences from parent compounds [14] [16] |

The strategic selection of hopping approach involves a fundamental trade-off: small-step hops (such as heterocycle replacements) generally offer higher success rates for maintaining biological activity but yield lower structural novelty, while large-step hops (particularly topology-based approaches) can deliver breakthrough chemotypes but carry greater risk of activity loss [14]. This risk-rebalance profile makes smaller-step approaches more prevalent in published literature, though successful large-step hops can provide significant intellectual property and clinical advantages [14] [16].

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Hopping

The successful implementation of scaffold hopping requires the integration of computational design, chemical synthesis, and biological evaluation. The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for executing and validating scaffold hops.

Computational Workflow for Core Replacement

This protocol outlines a standard computational approach for identifying novel scaffolds using known active compounds as starting points, particularly valuable for generating novel chemotypes in chemogenomic library design.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Scaffold Hopping

| Tool/Reagent | Vendor/Provider | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ReCore | BiosolveIT [15] | Suggests scaffold replacements by analyzing exit vectors and geometry [15] |

| BROOD | OpenEye [15] | Fragments molecules and identifies bioisosteric replacements for molecular cores [15] |

| SHOP | Molecular Discovery [15] | Performs scaffold hopping based on 3D molecular similarity and pharmacophore matching [15] |

| Spark | Cresset [15] | Uses field-based similarity to propose bioisosteric core replacements [15] |

| RDKit | Open-Source [17] | Cheminformatics toolkit for scaffold network generation and molecular manipulation [17] |

| Cytoscape | Open-Source [17] | Network visualization software for analyzing scaffold relationships and hierarchies [17] |

Procedure:

Input Structure Preparation: Begin with a known active compound, preferably with structural data (X-ray co-crystal pose) of the ligand bound to its target protein. Prepare the 3D structure using appropriate energy minimization and conformational sampling. If structural data is unavailable, generate a pharmacophore hypothesis based on structure-activity relationship (SAR) data [15].

Scaffold Identification and Deconstruction: Define the current molecular scaffold (core) and its attachment vectors. Fragment the molecule at the core, preserving the geometry of substituent groups that interact with the protein target [15].

Replacement Scaffold Identification: Utilize specialized software such as ReCore, BROOD, or SHOP to search structural databases for alternative cores that can accommodate the existing substituent geometry [15]. Apply shape-based and pharmacophore-based screening filters to prioritize candidates that maintain critical spatial relationships.

Virtual Library Generation and Filtering: Connect the proposed novel scaffolds with the original substituents to generate a virtual library of hop candidates. Apply computational filters to assess drug-like properties (e.g., logP, topological polar surface area) and synthetic accessibility [15].

Binding Pose Validation: Perform molecular docking of top-ranked candidates into the target protein's binding site to confirm maintenance of key interactions. Compare the binding mode of hop candidates with the original compound [15].

Figure 1: Computational workflow for scaffold hopping identification.

Experimental Validation of Hop Candidates

Following computational design and synthesis, rigorous biological evaluation is essential to confirm the success of a scaffold hop.

Procedure:

Primary Target Affinity/Potency Assay: Test the synthesized hop compounds in a dose-response manner using the same biochemical or cell-based assay used to characterize the original active compound. Calculate IC₅₀ or EC₅₀ values to compare potency directly [15].

Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate compounds against related targets or anti-targets to ensure the scaffold hop has not introduced undesired off-target interactions. This is particularly important in kinase and GPCR-targeted programs [15].

Structural Biology Validation: Where possible, determine an X-ray co-crystal structure of the hop compound bound to the target protein. This provides definitive confirmation that the key binding interactions have been maintained despite the core modification [15]. Superimpose the new structure with the original ligand-protein complex to validate pharmacophore conservation.

Physicochemical and ADMET Profiling: Characterize the hop compounds for key drug-like properties, including solubility, lipophilicity (logD), metabolic stability, and membrane permeability. Compare these profiles with the original scaffold to identify potential improvements [15].

Case Study: Scaffold Hopping in BACE-1 Inhibitor Development

A compelling real-world application of scaffold hopping comes from a project at Roche targeting the β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE-1) for Alzheimer's disease therapy [15].

Challenge: The research team sought to improve the aqueous solubility and reduce the lipophilicity (logD) of their lead compound series while maintaining potency against BACE-1 [15].

Computational Solution: The team employed the ReCore software, which suggested replacing the central phenyl ring with a trans-cyclopropylketone moiety [15].

Experimental Outcome: The newly synthesized compound exhibited significantly reduced logD and improved solubility while maintaining excellent enzymatic potency. X-ray co-crystallization studies with BACE-1 confirmed the effectiveness of the scaffold hop, demonstrating that the novel core maintained all critical binding interactions despite the significant structural change [15].

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes of BACE-1 Inhibitor Scaffold Hop

| Parameter | Original Scaffold | Hopped Scaffold | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Phenyl ring | trans-Cyclopropylketone | Reduced aromaticity, introduced polarity [15] |

| BACE-1 IC₅₀ | Excellent potency | Excellent potency | Maintained target engagement [15] |

| logD (pH 7.4) | High | Significantly reduced | Improved physicochemical properties [15] |

| Aqueous Solubility | Limited | Improved | Enhanced drug-like character [15] |

This case exemplifies how strategic scaffold hopping can successfully address specific compound liabilities while preserving the pharmacological activity essential for therapeutic development.

Scaffold hopping represents a sophisticated cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry, enabling the deliberate exploration of novel chemical space while leveraging established structure-activity relationships. The systematic classification of hops—from conservative heterocycle replacements to transformative topology-based designs—provides a strategic framework for balancing novelty with a reduced risk of activity loss. As computational methodologies continue to advance, integrating more accurate prediction of bioisosteric relationships and binding pose conservation, scaffold hopping will remain an indispensable component of chemogenomic library design and optimization. By applying the detailed protocols and analyses outlined in this document, researchers can effectively leverage scaffold hopping to generate intellectually property-distinct, clinically superior bioactive compounds that address the persistent challenges of modern drug discovery.

Methodologies in Action: Traditional and AI-Driven Scaffold Analysis Techniques

In chemogenomic library design, the systematic analysis of molecular scaffolds and their structural features is fundamental to achieving meaningful diversity. The Murcko framework, derived from the pioneering work of Bemis and Murcko, provides a method to decompose a molecule into its core ring system and linkers, effectively representing the molecular scaffold [18] [19]. This decomposition allows researchers to move beyond peripheral substituents and compare the fundamental skeletal architectures of compounds. Concurrently, molecular fingerprints, such as Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP), encode molecular structures into bit strings, enabling rapid computational comparison of chemical libraries based on the presence or absence of specific substructural features [18] [20].

Within the context of chemogenomic library diversity research, these methodologies are not merely descriptive but are critical for making strategic decisions. Analyzing the scaffold diversity of a compound collection—the presence of distinct molecular skeletons—is widely recognized as one of the most effective ways to increase its overall functional diversity [21]. This is because the central scaffold primarily defines the overall three-dimensional shape of a molecule, and shape diversity is a fundamental indicator of the potential range of biological activities a library can probe [21]. The integration of Murcko framework analysis with molecular fingerprinting creates a powerful toolkit for characterizing the coverage of chemical space, identifying regions of over-saturation or neglect, and guiding the acquisition or synthesis of novel compounds to fill these gaps.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Metrics

The Murcko Framework Decomposition

The Bemis-Murcko analysis involves a systematic deconstruction of a molecule into its core components [18] [19]. The process begins with the removal of all terminal, non-ring atoms (side chains), leaving behind the ring systems and the linkers that connect them. This resulting structure is the Murcko framework or scaffold. A key insight from the original analysis was that a surprisingly small number of frameworks account for a large proportion of known drugs, indicating a skewed distribution in pharmaceutical chemical space [18]. This analysis allows for the quantification of scaffold diversity within any compound collection.

Molecular Fingerprints for Similarity and Diversity

Molecular fingerprints are numerical representations of chemical structure that facilitate rapid similarity comparisons. The Tanimoto coefficient is the most common metric for quantifying the similarity between two fingerprints [18] [20]. It is calculated as the ratio of the number of common features to the number of unique features across the two molecules. A Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) of 1.0 indicates identical fingerprints, while a value of 0.0 indicates no similarity.

Different fingerprint types offer varying levels of resolution:

- ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint): A circular fingerprint that captures atomic environments and is particularly well-suited for assessing molecular diversity and for machine learning applications [18] [20].

- FCFP (Functional Connectivity Fingerprint): A variant of ECFP that uses generalized atom types based on functional class, making it more suitable for identifying functionally similar molecules [18].

- MACCS Keys: A dictionary-based fingerprint consisting of pre-defined structural fragments, providing a standardized and interpretable set of features [20].

Table 1: Common Molecular Fingerprints and Their Applications in Diversity Analysis

| Fingerprint Type | Description | Common Use Cases | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | Circular fingerprint capturing atom neighborhoods within a radius of 2 bonds. | Diversity analysis, Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) modeling, Machine learning. | [18] [20] |

| FCFP4 | Functional-class version of ECFP4. | Scaffold hopping, Bioactivity profiling. | [18] |

| MACCS Keys | A set of 166 predefined binary structural fragments. | Rapid similarity screening, Legacy similarity search. | [20] |

| RDKit Fingerprints | A topological fingerprint based on linear subgraphs. | General-purpose similarity and machine learning, often with optimized performance. | [20] |

Key Diversity Metrics from Literature

Analyses of public datasets have yielded critical insights into the scaffold diversity of biologically relevant chemical space. One study noted a two-fold enrichment of metabolite scaffolds in the drug dataset (42%) compared to currently used lead libraries (23%), highlighting a significant underutilization of natural product-like scaffolds in synthetic collections [18]. Furthermore, the study revealed that only a small percentage (5%) of natural product scaffold space is shared by the lead dataset, identifying a vast reservoir of unexplored scaffolds with potential biological relevance [18].

Table 2: Comparative Scaffold Analysis Across Biologically Relevant Datasets

| Dataset | Key Finding | Implication for Library Design | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Products (NPs) | Contains a maximum number of rings and rotatable bonds; over 1300 ring systems are missing from screening libraries. | A rich source of complex, novel scaffolds for targeting "undruggable" targets like protein-protein interactions. | [18] [21] |

| Metabolites | Has the highest average molecular polar surface area and solubility, but the lowest number of rings and limited scaffold diversity. | Useful for designing leads with improved ADMET properties, but limited for broad scaffold diversity. | [18] |

| Drugs | Shows high similarity to toxics in fingerprint space; scaffold distribution is highly skewed (few frameworks are very common). | Confirms bias in current libraries; underscores the need to explore new scaffolds for novel target classes. | [18] [21] |

| AI-Designed Molecules | 42.3% of AI-designed hits have high similarity (Tcmax > 0.4) to known active compounds, indicating limited novelty. | Highlights the challenge of achieving true novelty with AI and the need for diverse training data. | [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Murcko Scaffold Decomposition and Diversity Analysis

This protocol details the process for extracting and analyzing Murcko scaffolds from a compound library to assess scaffold diversity.

I. Materials and Software

- Input Data: A chemical library in SMILES or SDF format (e.g., from ChEMBL, DrugBank, or an in-house collection).

- Software/Tools: A cheminformatics toolkit capable of Murcko decomposition (e.g., RDKit or OpenBabel). The following examples use RDKit, a widely used open-source toolkit.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preparation and Standardization

- Load the molecular structures from the input file.

- Standardize the structures by removing salts, neutralizing charges, and generating canonical tautomers. This ensures consistent scaffold assignment.

Murcko Scaffold Extraction

- For each standardized molecule, apply the Murcko decomposition algorithm.

- The algorithm: a. Removes all side chains and acyclic linkers, retaining only ring atoms and the linkers that connect rings. b. Converts the resulting structure into a canonical SMILES representation to identify identical scaffolds.

- Code Snippet (using RDKit in Python):

Scaffold Frequency Analysis

- Count the frequency of each unique scaffold SMILES.

- Calculate the scaffold diversity index, which can be defined as the ratio of the number of unique scaffolds to the total number of compounds in the library. A value closer to 1 indicates high diversity, while a value closer to 0 indicates a few dominant scaffolds.

Visualization and Interpretation

- Generate a histogram plotting the frequency of the top N (e.g., 20) most common scaffolds. This visually reveals the "long tail" distribution typical of chemical libraries.

- Identify and list scaffolds that are unique to your library or, conversely, those that are over-represented compared to reference sets like known drugs or natural products.

The following workflow graph outlines the key steps and decision points in this protocol.

Protocol 2: Virtual Screening Using Molecular Fingerprints and Machine Learning

This protocol describes a virtual screening workflow using molecular fingerprints as features for a machine learning model to prioritize compounds from a drug repurposing library, as demonstrated in a study for identifying USP8 inhibitors [20].

I. Materials and Software

- Active and Inactive Compound Sets: A training set with known actives and inactives (or decoys) for the target of interest.

- Screening Library: The library to be screened (e.g., DrugBank, Broad Repurposing Hub).

- Software/Tools: A cheminformatics library (e.g., RDKit) for fingerprint generation and a machine learning library (e.g., scikit-learn, XGBoost).

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Curation and Featurization

- Curate a training set from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL) or high-throughput screening (HTS) data. Label compounds as active or inactive based on a defined activity threshold.

- For each compound in the training and screening sets, generate multiple molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, RDKit, MACCS). The study on USP8 inhibitors found that the RDKit fingerprint paired with an XGBoost model achieved a 16.3-fold improvement in hit-rate over random selection [20].

Model Training and Validation

- Train a machine learning classifier, such as XGBoost, using the fingerprints as input features and the activity labels as the target variable.

- Optimize model hyperparameters via cross-validation.

- Evaluate model performance using metrics like ROC-AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) and PR-AUC (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve). The USP8 study achieved an MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) of 0.607 at a 0.1 classification threshold [20].

Virtual Screening and Hit Analysis

- Use the trained model to predict the probability of activity for each compound in the screening library.

- Rank the screening library by the predicted probability and select the top candidates for experimental testing.

- Analyze the chemical diversity of the hits by calculating the Tanimoto similarity between predicted actives and known actives. The goal is to identify structurally novel hits (low Tc) while maintaining activity. The USP8 study discovered 9 new Bemis-Murcko scaffolds with low similarity to known USP8 inhibitors [20].

The following workflow graph illustrates this machine-learning-based screening process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Scaffold and Fingerprint Analysis

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Example Use in Protocols | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Software | |||

| RDKit | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics and machine learning. | Core library for Murcko decomposition, fingerprint generation (ECFP, RDKit), and molecular standardization. | [20] |

| OpenBabel | A chemical toolbox designed to speak the many languages of chemical data. | Alternative to RDKit for file format conversion and basic descriptor calculation. | |

| Commercial Platforms (e.g., Scitegic Pipeline Pilot) | Workflow-based informatics platforms with extensive chemistry components. | Used in large-scale studies for calculating FCFP fingerprints and complex data analysis pipelines. | [18] |

| Data Resources | |||

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Source of known active and inactive compounds for model training in Protocol 2. | [19] |

| DrugBank Repurposing Hub | A database containing FDA-approved and investigational drugs. | A prime screening library for drug repurposing campaigns in virtual screening. | [20] |

| PubChem | A public database of chemical molecules and their activities. | Source of chemical structures and HTS data for analysis and model training. | [18] [22] |

| Computational Libraries | |||

| XGBoost | An optimized distributed gradient boosting library. | The ML classifier of choice in multiple studies for virtual screening due to its high performance. | [20] |

| scikit-learn | A simple and efficient tool for data mining and data analysis. | For implementing other ML models and for standard data preprocessing and evaluation. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The combined use of Murcko frameworks and molecular fingerprints provides a robust, quantitative foundation for analyzing and designing diverse chemogenomic libraries. However, several challenges and future directions are emerging.

A primary challenge is the limited novelty of compounds generated by some computational methods, including AI. A recent analysis found that 42.3% of AI-designed active compounds exhibited high structural similarity (Tcmax > 0.4) to known actives, with only 8.4% achieving high novelty (Tcmax < 0.2) [19]. This is often due to biases in training data and the inherent conservatism of similarity-based approaches.

To overcome this, the field is moving towards:

- Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS): This synthetic strategy aims to efficiently populate chemical space with structurally complex and diverse small molecules by deliberately incorporating skeletal (scaffold), stereochemical, and appendage diversity [21]. DOS libraries are specifically designed to explore a broader range of chemical space than traditional combinatorial libraries.

- Advanced Similarity Metrics: Relying solely on Tanimoto coefficients of standard fingerprints can miss opportunities for "scaffold hopping," where different scaffolds achieve similar binding modes. Future work should incorporate metrics that better capture scaffold topology and three-dimensional shape [19].

- Structure-Based Generative Models: While still developing, generative models that use protein structural information as a direct input show promise in creating novel scaffolds tailored to a binding pocket, potentially leading to more effective exploration of uncharted chemical space [19].

In conclusion, while Murcko frameworks and molecular fingerprints remain indispensable traditional workhorses, their full power is realized when they inform and are integrated with next-generation strategies like DOS and advanced AI models to systematically conquer the vast and biologically relevant regions of chemical space that remain unexplored.

The process of drug discovery is notoriously arduous, often spanning 10-15 years with costs averaging approximately $2.6 billion and facing nearly 90% failure rates for drugs entering clinical trials [23]. Within this challenging landscape, scaffold analysis has emerged as a crucial strategy for navigating chemical space and improving the efficiency of early discovery phases. Scaffold hopping—the discovery of new core structures that retain biological activity—enables medicinal chemists to overcome limitations of existing compounds, including toxicity, metabolic instability, and patent restrictions [24]. The chemogenomic library diversity research provides the foundational framework for understanding the relationship between chemical structures and their biological effects across multiple targets, creating a systematic approach to explore structure-activity relationships [5].

Traditional molecular representation methods, including molecular fingerprints and descriptors, have historically supported scaffold analysis through similarity searching and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling [24]. However, these approaches rely on predefined rules and expert knowledge, limiting their ability to explore novel chemical spaces beyond known structural domains. The integration of artificial intelligence has fundamentally transformed scaffold representation, enabling data-driven discovery of novel bioactive compounds with enhanced efficacy and safety profiles [24]. Modern AI-driven representation methods have shifted from manual feature engineering to automated learning of complex molecular features directly from data, dramatically expanding the possibilities for scaffold hopping and de novo molecular design [23] [24].

AI-Driven Molecular Representation Methods

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Scaffold Representation

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful architecture for molecular representation because they naturally operate on the graph structure of molecules, where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [25]. This native structural representation allows GNNs to preserve both local chemical environments and global molecular topology, capturing essential features that determine biological activity [23]. The most common framework for implementing GNNs in chemistry is the Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN), which operates through iterative steps of information propagation between connected atoms [25].

The MPNN framework consists of three fundamental phases [25]:

- Message Passing: Each atom collects feature vectors from its neighboring atoms through a learned message function.

- Node Update: The atom updates its own representation by combining incoming messages with its current state using an update function.

- Readout: Atom-level representations are aggregated into a molecular-level representation using permutation-invariant functions.

For scaffold representation, GNNs excel at capturing key molecular interactions—including hydrogen bonding patterns, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic forces—that are essential for maintaining biological activity during scaffold hopping [24]. Unlike traditional fingerprints that encode predefined substructures, GNNs learn to identify relevant chemical motifs directly from data, enabling them to recognize non-obvious structural relationships that preserve activity across diverse scaffolds [24].

Chemical Language Models (CLMs) for Scaffold Representation

Chemical Language Models (CLMs) approach molecular representation by treating chemical structures as sequences, typically using Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings or their alternatives as a specialized chemical language [24]. Inspired by advances in natural language processing, transformer-based architectures process these sequences by tokenizing molecular strings at the atomic or substructure level, then mapping these tokens into continuous vector representations that capture syntactic and semantic relationships [24].

CLMs employ self-supervised pre-training strategies, such as masked token prediction, where portions of the input sequence are hidden and the model learns to predict them based on context [24]. This approach enables the model to internalize chemical grammar rules and structural constraints without explicit human labeling. For scaffold representation, CLMs can learn to generate novel structures while maintaining the essential features required for biological activity, effectively enabling scaffold hopping through sequence generation [24].

Recent research indicates that for chemical language models, data diversity often surpasses scale as the critical factor for performance. One study found that beyond a minimal threshold, further model scaling yielded no gains in hit generation rate, while dataset scaling gave diminishing returns [26]. Instead, dataset diversification strategies substantially increased hit diversity with minimal change in hit rate, suggesting a paradigm shift from scale-first to diversity-first training approaches [26].

Comparative Analysis of Representation Methods

Table 1: Comparison of AI Methods for Scaffold Representation

| Representation Method | Molecular Input Format | Key Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) | Native representation of molecular structure; Captures both local and global topology; Naturally preserves molecular symmetry | Requires conformer generation for 3D information; Computationally intensive for large graphs | Scaffold hopping requiring spatial awareness; Property prediction for complex molecules |

| Chemical Language Models (CLMs) | SMILES, SELFIES, or other string representations | Leverages advanced NLP architectures; Simple serialization; Rapid generation of novel structures | Limited 3D structural awareness; SMILES validity constraints; May generate synthetically inaccessible structures | High-throughput virtual screening; De novo molecular generation; Transfer learning from chemical databases |

| 3D-Geometric GNNs | 3D molecular coordinates with atomic features | Explicit modeling of spatial relationships; SE(3)-equivariance; Superior binding affinity prediction | High computational requirements; Complex architecture; Limited pretraining data availability | Protein-ligand interaction modeling; Conformation-sensitive property prediction |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representation Methods on Key Tasks

| Method | Scaffold Hopping Accuracy | Novelty Rate | Synthetic Accessibility | Training Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) | 62% | Low | High | High |

| Graph Neural Networks | 78% | Medium-High | Medium | Medium |

| Chemical Language Models | 75% | High | Medium-Low | Medium |

| 3D-Aware GNNs | 81% | Medium | Medium | Low |

Application Notes: Protocols for Scaffold Representation

Protocol 1: GNN-Based Scaffold Hopping for Lead Optimization

Objective: Identify novel scaffold hops with maintained biological activity while improving ADMET properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound dataset with measured bioactivity (e.g., ChEMBL)

- RDKit or OpenBabel for molecular processing

- DeepGraphLibrary or PyTor Geometric for GNN implementation

- High-performance computing resources with GPU acceleration

Experimental Workflow:

Data Preparation and Curation

- Collect bioactivity data for target of interest from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL) or proprietary sources

- Standardize molecular structures: neutralize charges, remove duplicates, handle tautomers

- Annotate compounds with scaffold levels using hierarchical scaffolding (e.g., Scaffold Hunter) [5]

- Split data into training/validation/test sets (typical ratio: 80/10/10)

Molecular Graph Construction

- Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges

- Initialize node features using atomic properties (atom type, degree, hybridization, etc.)

- Initialize edge features using bond characteristics (bond type, conjugation, stereo)

- Generate multiple conformers to capture molecular flexibility

GNN Model Configuration

- Implement MPNN architecture with 3-5 message passing layers

- Use attention-based aggregation mechanisms for adaptive readout

- Include skip connections to mitigate over-smoothing

- Configure output heads for multi-task learning (activity prediction, property prediction)

Model Training and Validation

- Pre-train GNN on large-scale molecular datasets (e.g., QM9, PCBA) for transfer learning

- Fine-tune on target-specific bioactivity data using multi-fidelity learning approaches [27]

- Apply Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning

- Validate model using time-split or scaffold-split cross-validation

Scaffold Hopping and Compound Generation

- Extract molecular embeddings from the trained GNN

- Perform similarity searching in latent space to identify diverse scaffolds with similar embeddings

- Apply generative approaches for de novo scaffold design

- Filter proposed scaffolds using medicinal chemistry rules and synthetic accessibility scoring

Diagram Title: GNN Scaffold Hopping Workflow

Protocol 2: Chemical Language Model for De Novo Scaffold Design

Objective: Generate novel molecular scaffolds with predicted activity against a specific biological target using sequence-based generative models.

Materials and Reagents:

- Large-scale chemical database for pre-training (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC)

- SMILES or SELFIES representation of molecules

- Transformer-based model architecture

- Reinforcement learning framework for optimization

Experimental Workflow:

Data Preprocessing and Tokenization

- Extract canonical SMILES from chemical databases

- Implement robust tokenization (atom-level, SMILES syntax-aware)

- Apply data augmentation through SMILES enumeration

- Curate diverse training sets emphasizing structural diversity over sheer volume [26]

Model Architecture Selection

- Implement encoder-decoder transformer architecture

- Configure appropriate context window (typically 256-512 tokens)

- Set embedding dimensions (512-1024) based on model size constraints

- Include attention mechanisms for capturing long-range dependencies

Pre-training and Fine-tuning

- Pre-train model on general chemical database using masked language modeling

- Apply transfer learning to adapt model to target-specific chemical space

- Implement multi-task fine-tuning for balanced property optimization

Reinforcement Learning Optimization

Scaffold Generation and Validation

- Generate novel scaffolds using sampling techniques (top-k, nucleus sampling)

- Apply validity filters (chemical validity, synthetic accessibility)

- Validate proposed scaffolds through docking studies or experimental testing

Diagram Title: CLM Scaffold Generation Pipeline

Protocol 3: Multi-Fidelity Transfer Learning for Sparse Data Scenarios

Objective: Leverage multi-fidelity data to improve scaffold representation and activity prediction in data-sparse scenarios common in early drug discovery.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-throughput screening data (low-fidelity)

- Confirmatory assay data (high-fidelity)

- Graph neural network architecture with adaptive readout mechanisms

- Transfer learning framework

Experimental Workflow:

Multi-Fidelity Data Integration

- Collect low-fidelity data (HTS) and high-fidelity data (confirmatory assays)

- Align compound identifiers across different data sources

- Account for experimental noise and systematic biases

- Implement appropriate data normalization across fidelity levels

Transfer Learning Strategy

Model Architecture Configuration

- Implement GNN with neural readout functions instead of fixed aggregations [27]

- Include domain adaptation layers to bridge fidelity gaps

- Configure progressive neural networks for knowledge transfer

Training and Evaluation

- Employ multi-fidelity learning algorithms

- Validate using time-split or cold-start scenarios

- Benchmark against single-fidelity models and traditional QSAR approaches

- Evaluate extrapolation capability to novel scaffold spaces

Key Findings: Research demonstrates that transfer learning with GNNs in multi-fidelity settings can improve performance on sparse high-fidelity tasks by up to eight times while using an order of magnitude less high-fidelity training data [27]. In transductive settings (where low-fidelity and high-fidelity labels are available for all data points), inclusion of actual low-fidelity labels typically provides performance improvements between 20% and 60%, with severalfold improvements in best cases [27].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Scaffold Representation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Key Functionality | Application in Scaffold Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC, DrugBank | Source of bioactivity data and compound structures | Training data for AI models; Reference for scaffold analysis and hopping |

| Molecular Representation | RDKit, OpenBabel, DeepChem | Chemical informatics toolkit; Molecular featurization | Structure standardization; Fingerprint generation; Graph representation |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch Geometric, DeepGraphLibrary, DGL-LifeSci | GNN implementations specialized for molecular data | Building and training scaffold representation models |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | Custom-designed targeted libraries (e.g., 1,211 compounds targeting 1,386 anticancer proteins) [29] | Experimentally validated compounds with known target annotations | Validation of computational predictions; Phenotypic screening |

| Visualization & Analysis | Scaffold Hunter, ChemSuite | Hierarchical scaffold analysis and visualization | Scaffold tree generation; Diversity analysis; Compound clustering |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Case Study: EGFR Inhibitor Design Using Reinforcement Learning

A proof-of-concept study demonstrated the application of deep generative recurrent neural networks enhanced by reinforcement learning for designing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors [28]. The researchers addressed the critical challenge of sparse rewards in reinforcement learning, where the majority of generated molecules are predicted as inactive, making learning difficult.

Methodological Innovations:

- Combination of policy gradient algorithm with transfer learning

- Experience replay to retain knowledge of successful scaffolds

- Real-time reward shaping to guide exploration

- Ensemble Random Forest models as predictors for more robust activity prediction

Experimental Results:

- Models trained with only policy gradient failed to discover molecules with high active class probability due to sparse rewards

- The combination of policy gradient with experience replay and fine-tuning significantly improved exploration

- Generated compounds included privileged EGFR scaffolds found in known active molecules

- Experimental testing validated the potency of generated compounds, confirming the effectiveness of the approach [28]

Case Study: Phenotypic Screening with Chemogenomic Libraries

In glioblastoma research, a systematically designed chemogenomic library of 789 compounds covering 1,320 anticancer targets was applied to profile patient-derived glioma stem cells [29]. This approach demonstrated:

Library Design Strategy:

- Analytic procedures considering library size, cellular activity, chemical diversity, and target selectivity

- Coverage of diverse protein targets and pathways implicated in cancer

- Balancing comprehensive target coverage with practical screening feasibility

Research Findings:

- Highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses across patients and GBM subtypes

- Patient-specific vulnerabilities identifiable through targeted screening

- Integration of computational prediction with experimental validation

- Demonstration of precision oncology applications through targeted compound libraries [29]

The integration of Graph Neural Networks and Chemical Language Models for scaffold representation represents a paradigm shift in chemogenomic library design and diversity research. These AI-driven approaches enable a more fundamental understanding of structure-activity relationships, moving beyond superficial similarity to capture the essential molecular features that determine biological activity.

The emerging lab-in-a-loop concept promises to create a closed-loop, self-improving drug discovery ecosystem where AI algorithms generate predictions that are experimentally validated, with results feeding back to retrain and enhance the models [23]. This iterative process represents a transformation from linear, human-driven discovery to cyclical, AI-driven processes with human oversight, promising compounding improvements in efficiency and innovation [23].

Future developments will likely focus on multimodal representations that combine the strengths of graph-based and sequence-based approaches while incorporating 3D structural information, pharmacokinetic properties, and systems biology data. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly enable the de novo design of optimized compounds with specific, pre-defined properties, fundamentally redefining the strategic approach to drug discovery [23].

For researchers in chemogenomic library diversity, the adoption of AI-driven scaffold representation methods offers the potential to systematically explore chemical space, identify novel bioactive compounds, and accelerate the development of targeted therapies for precision medicine applications. The protocols and applications outlined in this document provide a foundation for implementing these transformative approaches in both academic and industrial drug discovery settings.

Within modern drug discovery, the strategic design of chemical libraries is paramount for efficiently navigating the vastness of chemical space to identify novel bioactive compounds. Scaffold-focused library design has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this challenge, concentrating synthetic and computational efforts on central molecular cores, or scaffolds, that are privileged for target families or specific binding sites [30]. This approach provides a structured method to explore chemical diversity while maintaining synthetic feasibility and enhancing the likelihood of identifying hit compounds. Framed within the context of chemogenomic library diversity research, scaffold analysis enables the systematic interrogation of biological target spaces by ensuring that the resulting compound libraries cover a wide range of protein families and biological pathways [31] [5]. This manuscript details comprehensive application notes and protocols for the in silico design and enumeration of scaffold-focused libraries, providing researchers with a practical workflow to transition from virtual designs to physically available, "REAL" compound collections ready for biological screening.

Application Notes: Core Principles and Workflow

Foundational Concepts in Scaffold-Based Design

The design of a scaffold-focused library begins with the identification and selection of appropriate molecular scaffolds. A scaffold is defined as the core structural framework of a molecule, which can be systematically decorated with various substituents at specific points of diversity [30]. In chemogenomic research, the objective is often to select scaffolds that are "privileged," meaning they possess inherent binding compatibility with a range of biologically relevant targets. The subsequent enumeration process involves the computational generation of all possible concrete molecules derived from these scaffolds and a defined set of building blocks, using robust chemical reaction rules [32].

The strategic value of this approach lies in its balance of diversity and focus. By concentrating on a curated set of scaffolds, researchers can efficiently saturate a specific region of chemical space that is most relevant to their target of interest, whether it be a single protein or a full target class like kinases or GPCRs [5]. This contrasts with purely diversity-oriented synthesis, which may generate a broader but less targeted set of structures. A key consideration throughout the design process is synthetic feasibility, ensuring that the virtually enumerated compounds can be feasibly synthesized to create a physical "make-on-demand" library, such as those exemplified by the REadily Accessible (REAL) Database [32].

Integrated Workflow for Library Design and Enumeration

The following workflow synthesizes best practices for designing, enumerating, and prioritizing compounds for a scaffold-focused library. It integrates target-agnostic and target-aware strategies to maximize the probability of success in phenotypic or target-based screening campaigns.

Diagram 1: A comprehensive workflow for designing and enumerating a scaffold-focused library, from initial concept to physical compound collection.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Enumeration of a Virtual Library

This protocol details the steps for generating a virtual compound library using a defined scaffold and a set of building blocks, leveraging open-source chemoinformatics tools.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|