Resolving Phylogenetic Diversity in Cross-Species Genome Alignments: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational and methodological landscape for resolving phylogenetic diversity from cross-species genome alignments, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Resolving Phylogenetic Diversity in Cross-Species Genome Alignments: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational and methodological landscape for resolving phylogenetic diversity from cross-species genome alignments, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of phylogenetic diversity metrics and their significance in biodiversity and biomedical research. The content delves into cutting-edge methodological advances, including the integration of deep learning, novel alignment tools, and phylogenetic networks for detecting evolutionary relationships and gene flow. It further addresses critical challenges in troubleshooting and optimizing large-scale phylogenetic analyses, covering issues from model misspecification to computational bottlenecks. Finally, the article offers a framework for the validation and comparative assessment of phylogenetic diversity, emphasizing robust statistical comparisons and the selection of appropriate metrics for conservation and trait discovery. This synthesis aims to bridge the gap between theoretical phylogenetics and its practical applications in identifying evolutionarily significant, functionally diverse genomic elements for biomedical innovation.

The Foundations of Phylogenetic Diversity: From Concepts to Genomic Data

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

What is Phylogenetic Diversity (PD)?

Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) is a measure of biodiversity that incorporates the evolutionary relationships between species. It is quantitatively defined as the sum of the lengths of all the branches on a phylogenetic tree that span the members of a set of species [1] [2]. This approach recognizes that not all species are equally distinct; some represent vastly more unique evolutionary history than others.

How does PD differ from simple species richness?

Unlike simple species counts, PD accounts for the phylogenetic difference between organisms. Two communities might have the same number of species, but the community containing species from more distantly related lineages will have a higher PD, capturing a greater amount of evolutionary history and, by inference, a greater variety of biological features [1] [3].

What is the core rationale for using PD in conservation and research?

The core rationale is that PD represents "feature diversity" and "option value." The branches in a phylogenetic tree represent the accumulation of evolutionary features (genetic, phenotypic, behavioral). Therefore, maximizing the PD preserved in a set of species also maximizes the preserved feature diversity, which maintains future benefits and options for humanity, such as new medicines or resilient crop traits [2].

A Framework for Phylogenetic Metrics

With over 70 different phylogenetic metrics in use, selecting the right one is critical. A unifying framework classifies these metrics into three primary dimensions based on their mathematical form and the ecological question they address [3].

The Three Dimensions of Phylogenetic Diversity

| Dimension | Core Question | Representative Metric(s) | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | How much evolutionary history is represented? | Faith's PD (PD) | Conservation prioritization to maximize total evolutionary history preserved [1] [3]. |

| Divergence | How different are the species from one another? | Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD) | Inferring community assembly processes (e.g., environmental filtering vs. competition) [3]. |

| Regularity | How regular are the phylogenetic distances? | Variation of Pairwise Distance (VPD) | Understanding the evenness of evolutionary relationships within a community [3]. |

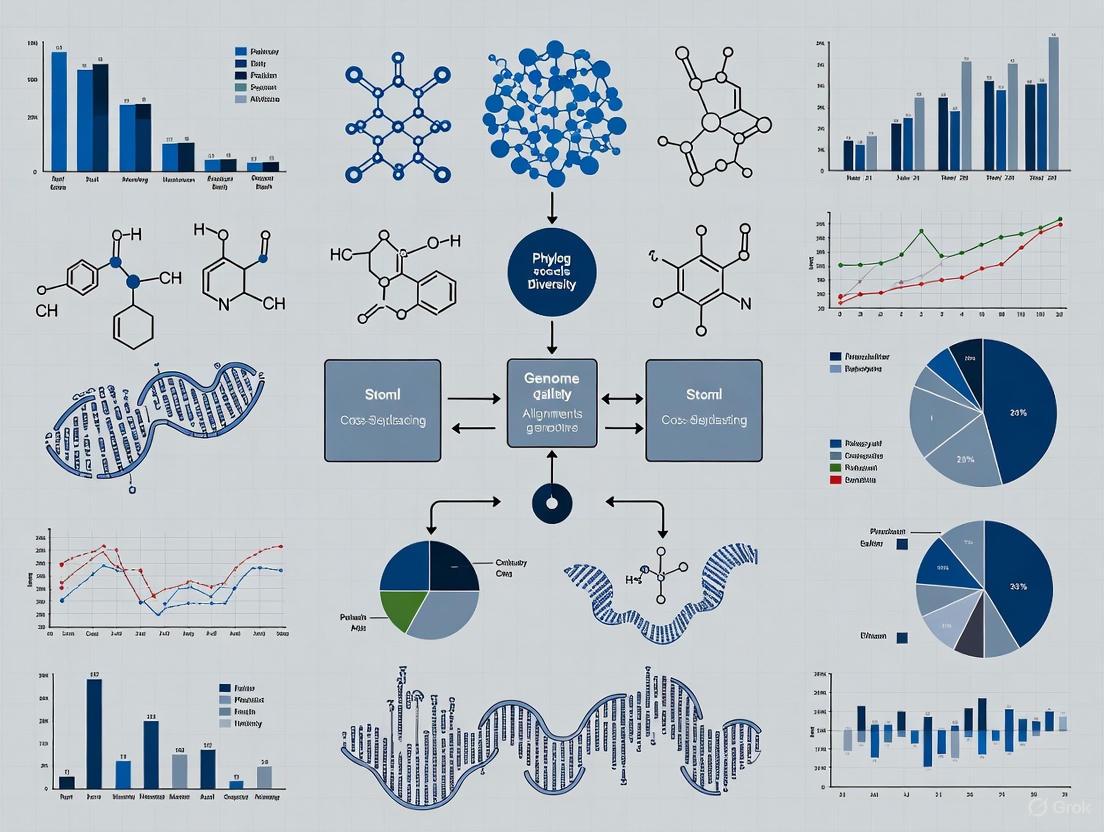

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting phylogenetic diversity metrics based on research questions.

Troubleshooting Common Phylogenetic Analysis Problems

Why did my phylogenetic tree structure change drastically when I added more strains/species?

A sudden and drastic change in tree topology after adding new data can be caused by several factors [4]:

- Low sequence coverage in new strains: This leads to a higher number of ignored positions in the alignment, effectively reducing the informative core genome used for tree building.

- Presence of a severe outlier: A highly divergent or contaminated sample can distort the entire tree. Check for strains with an unusually high number of variants.

- Inappropriate handling of missing data: Some tree-building algorithms ignore positions not present in all samples. Using a method like RAxML, which can incorporate these positions, can restore the correct structure [4].

- Data concatenation errors: In one case, concatenating divergent sample replicates created artificial heterozygous positions that were ignored, collapsing diverse strains into a single branch. Removing these concatenated samples resolved the issue [4].

How can I assess the reliability of my phylogenetic tree?

Always check bootstrap values. These values test whether your entire dataset supports the tree structure. A common rule of thumb is that bootstrap values below 0.8 (or 80%) are considered weak [4]. Nodes with low support should not be trusted for biological interpretation.

My tree and my SNP-based clustering give conflicting signals. Which one is correct?

This conflict often arises because phylogenetic trees are typically built from a core genome alignment, while SNP-based clustering (like a "SNP address") can be generated from a full pairwise comparison of genomes [4]. If two strains look similar on the tree but are in different SNP clusters, it may indicate similarity in the core genome but divergence in accessory genes. Investigate the alignment method and the genomic regions used for each analysis.

Advanced Considerations: Phylogenetic Networks

When should I use a phylogenetic network instead of a tree?

Use a phylogenetic network when you have evidence or suspicion of reticulate evolutionary events, such as hybridization, introgression, or horizontal gene transfer, which cannot be represented by a strictly branching tree [5]. Networks are essential for studying groups where these processes are common.

How do I interpret a phylogenetic network?

In a rooted phylogenetic network, a reticulation vertex (a node with two incoming branches) represents a hybridization event [5]. The inheritance probability (γ), a value between 0 and 1 assigned to one of the incoming edges, denotes the proportion of genetic material the hybrid inherited from that parent. A value of γ ≈ 0.5 suggests symmetrical contributions from both parents [5].

Diagram 2: A phylogenetic network showing hybridization and introgression events with inheritance probabilities.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Key Software and Packages for Phylogenetic Diversity Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RAxML | Phylogenetic tree inference | Building large, accurate trees from molecular data; can handle positions not present in all samples [4]. |

| FastTree | Phylogenetic tree inference | Rapid construction of approximate trees for large datasets [4]. |

| CIPRES Cluster | Online computing platform | Provides free access to supercomputing resources for running compute-intensive analyses like RAxML [4]. |

| V.PhyloMaker (R package) | Phylogeny generation | Constructing a phylogeny for a list of species using a broadly inclusive backbone (e.g., for vascular plants) [6]. |

| picante / vegan (R packages) | Metric calculation | Calculating a wide array of phylogenetic diversity metrics within ecological communities [6]. |

| EDGE of Existence program | Conservation prioritization | A global conservation initiative that uses evolutionary distinctness (a PD-related metric) to set priorities [1] [2]. |

For researchers in cross-species genome alignments, quantifying biodiversity extends beyond simple species counts. Phylogenetic diversity metrics leverage evolutionary relationships to provide a deeper understanding of genomic divergence and feature diversity. This guide details the core phylogenetic metrics—PDFaith, MPD, MNTD, NRI, and NTI—to assist in the selection, calculation, and interpretation of these measures in genomic studies [7] [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between PDFaith, MPD, and MNTD?

PDFaith, MPD, and MNTD capture different dimensions of evolutionary history. PDFaith (Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity) represents the total amount of evolutionary history in an assemblage by summing the branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree connecting a set of species [7]. MPD (Mean Pairwise Distance) measures the average evolutionary distance between all pairs of species in a sample, reflecting relatedness deep in the tree [7]. MNTD (Mean Nearest Taxon Distance) is the average evolutionary distance between each species and its closest relative in the sample, reflecting relatedness near the branch tips [7].

2. How do NRI and NTI help me infer ecological or evolutionary processes from my genomic data?

NRI (Net Relatedness Index) and NTI (Nearest Taxon Index) are standardized effect sizes that compare observed MPD and MNTD to values expected under a null model (e.g., a random assemblage from a regional species pool) [7].

- NRI is based on MPD. A significantly positive NRI indicates phylogenetic clustering (species are more closely related than expected by chance), which can suggest the influence of habitat filtering or limited dispersal. A significantly negative NRI indicates phylogenetic overdispersion (species are more distantly related than expected), which can suggest the influence of competitive exclusion [7].

- NTI is based on MNTD. It is often more sensitive to recent evolutionary events. The same interpretation for positive (clustering) and negative (overdispersion) values applies [7].

3. My analysis shows high species richness but low phylogenetic diversity (PDFaith). What does this imply for my study of cross-species genome alignments?

This result often indicates the presence of a recent, rapid radiation. The species in your assemblage are numerous but genetically very similar, having diverged from a common ancestor in a relatively short evolutionary time frame. For genome alignment research, this suggests that you are working with a clade of closely related species or lineages, where identifying genomic variations might require focusing on more rapidly evolving regions of the genome [7].

4. When should I use MPD versus MNTD to describe my genomic samples?

The choice depends on the scale of evolutionary history you wish to emphasize.

- Use MPD to understand deep evolutionary relationships and processes that have acted over long time scales. It provides a broad, "tree-wide" perspective on relatedness [7].

- Use MNTD to understand recent evolutionary relationships and processes, such as recent radiations or recent immigration events. It is more sensitive to patterns at the tips of the phylogenetic tree [7].

5. My phylogenetic tree is built from whole-genome alignments. Are there any special considerations for calculating these metrics?

High-throughput sequencing data, like whole-genome alignments, generally produce more robust and better-supported phylogenies compared to those built from a few genetic markers [7]. This strengthens the reliability of your PD metric calculations. Ensure that your branch lengths are proportional to the actual amount of genetic divergence (e.g., substitutions per site) as inferred from your alignments, as this is the fundamental input for all these metrics.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly low PDFaith | The assemblage may consist of many recently diverged species (a "bushy" clade) with short branch lengths [7]. | Verify the phylogenetic tree topology. Check if the species set is monophyletic and has undergone a recent radiation. Consider if this aligns with the biological context. |

| NRI/NTI values are not significant | The phylogenetic structure of your assemblage does not significantly differ from a random draw from the species pool. The null model used may be inappropriate [7]. | Review the composition of your regional species pool. Ensure the null model (e.g., random shuffling of tip labels) is appropriate for your research question and data. |

| MPD is high, but MNTD is low | The assemblage contains distinct, recent evolutionary radiations. Deep relationships are distant (high MPD), but within each deep branch, species are closely related (low MNTD) [7]. | Investigate the tree for the presence of multiple closely-related clades that are distantly related to each other. This pattern is common in adaptive radiations. |

| Discrepancy between PD metrics and species richness | Rapid radiations, imbalanced phylogenies, or rare dispersal events can decouple species counts from evolutionary history [7]. | This is an expected finding in many systems. Prioritize PD metrics if the goal is to capture feature diversity or evolutionary history, not just the number of taxa. |

| Poorly supported phylogenetic tree | The tree may be inferred from too few genetic markers, leading to unresolved relationships or unreliable branch lengths [7]. | Use phylogenetic trees estimated from many genetic markers or whole-genome data for more reliable and well-supported results, which are critical for accurate PD calculations [7]. |

The table below provides a structured comparison of the core phylogenetic diversity metrics for easy reference [7].

| Metric | Full Name | Interpretation | Calculation Basis | Standardized Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDFaith | Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity | Total evolutionary history; higher values = greater diversity [7]. | Sum of all branch lengths in the connecting tree [7]. | PDSES |

| MPD | Mean Pairwise Distance | Average relatedness between all species pairs; higher values = more distantly related species (deep tree structure) [7]. | Mean of all pairwise phylogenetic distances [7]. | NRI (Net Relatedness Index) |

| MNTD | Mean Nearest Taxon Distance | Average relatedness to closest relative; lower values = more compact topology at tips [7]. | Mean distance of each species to its nearest neighbor [7]. | NTI (Nearest Taxon Index) |

| NRI | Net Relatedness Index | Phylogenetic structure vs. null model; + values = clustering, - values = overdispersion [7]. | Standardized effect size of MPD [7]. | --- |

| NTI | Nearest Taxon Index | Phylogenetic structure at tips vs. null model; + values = clustering, - values = overdispersion [7]. | Standardized effect size of MNTD [7]. | --- |

Experimental Protocol: Calculating Phylogenetic Metrics from a Genome Alignment

This protocol outlines the key steps for deriving and interpreting phylogenetic diversity metrics from cross-species genome alignment data.

I. Materials and Software Requirements

- Input Data: Multi-sequence whole-genome alignment file (e.g., in FASTA, MAF, or VCF format).

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or workstation with sufficient memory and CPU cores.

- Key Software Packages:

- Phylogenetic Inference: IQ-TREE, RAxML, BEAST2.

- Metric Calculation: R with packages

picante,ape,PhyloMeasures. - Pipeline Integration: PhyloNext (for integrated data processing and analysis) [8].

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Phylogenetic Tree Inference:

- Use your whole-genome alignment as input for a phylogenetic inference tool (e.g., IQ-TREE).

- Select an appropriate nucleotide substitution model (e.g., ModelFinder within IQ-TREE).

- Execute the analysis to generate a rooted, time-calibrated phylogenetic tree with branch lengths proportional to genetic divergence (substitutions/site). Save the output as a Newick file (

.treefile).

Assemblage Data Preparation:

- Define the species assemblages for comparison (e.g., by geographic location, phenotypic group).

- Create a community data matrix (presence/absence or abundance) in a format compatible with R, such as a comma-separated values (CSV) file.

Metric Calculation in R:

- Import the phylogenetic tree and community data into R.

- Use the

picantepackage to calculate the core metrics. Below is example R code for a single assemblage: - Note: The negative sign in the NRI/NTI calculation aligns with the convention that positive values indicate clustering [7].

Interpretation and Visualization:

- Compare metric values across your defined assemblages.

- Statistically test the significance of NRI and NTI values against the null distribution.

- Visualize results by plotting phylogenetic trees and highlighting assemblages of interest.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for deriving phylogenetic diversity metrics from genomic data.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources and tools essential for conducting phylogenetic diversity analysis in the context of genomic research.

| Item Name | Category | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| IQ-TREE | Software | Efficient software for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference from molecular sequences; supports a wide range of evolutionary models [8]. |

| BEAST2 | Software | Bayesian statistical software for phylogenetic analysis; used for inferring time-calibrated trees and complex evolutionary models. |

R with picante package |

Software / Library | The primary environment for calculating and analyzing phylogenetic diversity metrics, including PD, MPD, MNTD, NRI, and NTI [7]. |

| Open Tree of Life (OToL) | Data Resource | Provides a comprehensive, synthetic phylogenetic tree of life, which can be used as a backbone or reference tree for analyses [8]. |

| Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) | Data Resource | Provides standardized species occurrence data, which is used to define species assemblages for analysis [8]. |

| PhyloNext Pipeline | Workflow Tool | An integrated computational pipeline (using Nextflow and Biodiverse) that streamlines the process from fetching GBIF data and OToL trees to calculating PD metrics [8]. |

Why Genome Alignments are Crucial for Accurate Phylogenetic Inference

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Alignment Artifacts and Frameshifts in Phylogenomic Analysis

Problem: Apparent frameshift mutations and shifted alignments in output, not representative of genuine biological mutations.

Explanation: Apparent frameshifts can result from local alignment errors rather than biological reality. These artifacts may be caused by low-quality sequencing data, inappropriate alignment parameters, or using evolutionarily distant reference species. Even sophisticated alignment pipelines can retain these errors, which subsequently bias phylogenetic inference and selection analyses [9] [10].

Solution:

- Implement comprehensive quality control: Run quality assurance on original reads using tools like FastQC and MultiQC before alignment [9].

- Filter alignment outputs: Remove low-quality alignments by keeping only primary alignments, proper pairs, or alignments with mapQ ≥ 20-30 [9].

- Apply post-alignment processing: Use BamLeftAlign to normalize alignments and Mark Duplicates to remove PCR artifacts [9].

- Verify reference consistency: Ensure the same reference genome assembly is used throughout analysis and visualization steps [9].

- Employ error-aware models: Use methods like BUSTED-E that incorporate an "error-sink" component to capture aberrant evolutionary patterns from alignment errors [10].

Prevention: For cross-species alignments, select reference genomes from species at appropriate evolutionary distances. Closer references (e.g., chimpanzee for human studies) help identify recent genomic events, while distant comparisons (e.g., human-pufferfish) primarily reveal coding sequences [11].

Guide 2: Addressing False Positive Selection Inference Due to Alignment Errors

Problem: Spuriously high rates of episodic diversifying selection (EDS) detected in genome-wide scans.

Explanation: Positive selection inference methods are highly sensitive to alignment errors. Even low error rates can profoundly bias EDS detection, as alignment errors can mimic patterns of positive selection. This problem often worsens with larger datasets as the probability of local alignment errors increases [10].

Solution:

- Apply BUSTED-E analysis: This method adds an error category (ωₑ ≥ 100) with maximum 1% weight to capture false signals from local alignment errors [10].

- Compare results with standard methods: Run both BUSTED and BUSTED-E analyses - a dramatic reversal in EDS support (e.g., p-value changing from 0.006 to 0.50) indicates likely alignment artifacts [10].

- Manual alignment inspection: Check regions with strong selection signals for local misalignment, particularly near sequence ends where errors often cluster [10].

- Use PRANK-C alignments: When computationally feasible, PRANK-C codon alignments are least affected by alignment errors and cannot be substantially improved by standard filtering programs [10].

Expected Outcome: BUSTED-E typically identifies pervasive residual alignment errors missed by automated filtering, produces more realistic positive selection estimates, reduces bias, and improves biological interpretation [10].

Guide 3: Optimizing Cross-Species Genome Alignment for Phylogenetic Diversity Assessment

Problem: Inadequate variant detection and phylogenetic resolution when using reference genomes from distantly related species.

Explanation: The evolutionary distance between target species and reference genome significantly impacts alignment completeness and variant detection. While felid species show high synteny conservation enabling successful cross-species alignment, more distant taxa may yield poor results [12].

Solution:

- Assess synteny conservation: For non-model species, first determine if a well-annotated reference from a related species exists with demonstrated synteny conservation [12].

- Validate with coverage metrics: Ensure >90% of reference genome is covered at sufficient depth (≥20x). Cheetah alignments to domestic cat reference achieved 94% properly paired reads, enabling discovery of 38+ million variants [12].

- Utilize multiple reference options: Test references at different evolutionary distances when possible. Read2Tree maintains higher precision with closer references but functions even with very distant references [13].

- Consider alignment-free methods: For extremely distant comparisons, tools like Read2Tree can process raw reads directly into orthologous groups, bypassing genome assembly and traditional alignment [13].

Performance Metrics: Successful cross-species alignments should achieve >90% reference coverage with proper pairing, enabling comprehensive variant discovery comparable to within-species alignments [12].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the key considerations when selecting reference species for cross-species genome alignments?

A: Reference selection depends on your biological question. For identifying functional elements, use species at intermediate evolutionary distances (diverged 40-80 million years) like human-mouse comparisons, which reveal both coding and conserved noncoding sequences. For primarily detecting coding sequences, use distantly related species (diverged ~450 million years). To identify recent evolutionary changes, use closely related species [11].

Q2: How do alignment errors specifically affect phylogenetic inference and selection analyses?

A: Alignment errors create false phylogenetic signals that mimic biological patterns. They increase false positive rates in diversifying selection tests, distort branch lengths, and can lead to incorrect tree topologies. Methods like BUSTED-E show that many genes initially flagged under positive selection are actually explained by alignment errors [10].

Q3: What computational strategies can handle large-scale phylogenomic datasets with hundreds of species?

A: New tools address scalability challenges: Phyling uses profile-based ortholog identification rather than all-against-all searches, enabling incremental dataset updates without reprocessing [14]. Read2Tree bypasses genome assembly entirely, processing raw reads directly into orthologous groups, achieving 10-100x speedup over assembly-based approaches while maintaining accuracy [13].

Q4: How reliable are cross-species alignments for variant discovery in non-model organisms?

A: When synteny is high, cross-species alignment works remarkably well. Felid studies aligned cheetah, snow leopard and Sumatran tiger to domestic cat reference, achieving 93-95% properly paired reads and discovering millions of high-quality variants. However, this approach has limitations in detecting rare variants [12].

Table 1: Impact of Evolutionary Distance on Alignment Detection Sensitivity

| Comparison Type | Divergence Time | Primary Sequences Detected | Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closely Related (e.g., Human-Chimpanzee) | ~7 million years | Recent genomic changes, species-specific sequences | Identifying traits unique to reference species |

| Intermediate Distance (e.g., Human-Mouse) | 40-80 million years | Coding sequences + conserved noncoding sequences | Finding functional noncoding elements |

| Distantly Related (e.g., Human-Pufferfish) | ~450 million years | Primarily coding sequences | Gene identification and annotation |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Alignment and Phylogenetic Tools

| Tool | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phyling | Profile-based ortholog identification using HMM profiles from BUSCO | Fast, scalable to thousands of species; checkpoint system for incremental updates | Lower accuracy with very distant references [14] |

| Read2Tree | Direct raw read processing into orthologous groups | 10-100x faster than assembly-based approaches; works with low-coverage (0.1×) data | Slightly lower accuracy with high coverage and very distant references [13] |

| BUSTED-E | Branch-site random effects model with error-sink component | Identifies residual alignment errors; reduces false positive selection inference | Requires reasonable alignment quality to start [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Variant Discovery Using Divergent Reference Genomes

Purpose: To identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in non-model species using reference genomes from related species.

Materials:

- Whole genome sequencing data from target non-model species

- High-quality reference genome assembly from related model species

- Computing infrastructure with ≥16GB RAM

- BWA-MEM2 or similar aligner [9]

- GATK or similar variant calling toolkit [12]

Methodology:

- Quality Control: Assess raw read quality using FastQC and MultiQC.

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using BWA-MEM2 with species-appropriate parameters.

- Processing: Convert, sort, and index alignment files; remove PCR duplicates.

- Variant Calling: Identify SNVs using HaplotypeCaller in GATK.

- Filtering: Apply variant quality score recalibration and hard filters.

- Annotation: Annotate variants using VEP or SnpEff with available gene models.

Validation: Expect >90% reference genome coverage with proper pairing. For felid species, cheetah alignments to domestic cat achieved 94% properly paired reads, enabling discovery of 38,839,061 variants [12].

Protocol 2: Phylogenomic Tree Inference with Error-Aware Selection Analysis

Purpose: To infer species phylogenies while accounting for alignment errors that bias selection inference.

Materials:

- Multiple sequence alignments of orthologous genes

- Phylogenetic tree inference software (IQ-TREE, RAxML-NG, or FastTree)

- HyPhy package with BUSTED and BUSTED-E methods [10]

- Computational resources for likelihood calculations

Methodology:

- Ortholog Identification: Extract orthologous sequences using Phyling (profile-based) or OrthoFinder (RBH-based) approaches [14].

- Alignment: Create multiple sequence alignments using MAFFT or PRANK-C.

- Tree Inference: Construct initial phylogenies using maximum likelihood or concatenation approaches.

- Selection Analysis:

- Run standard BUSTED analysis to test for episodic diversifying selection

- Run BUSTED-E analysis with error-sink component (ωₑ ≥ 100, max 1% weight)

- Compare results: dramatic changes in significance indicate alignment error contamination

- Visualization: Inspect alignment regions flagged by BUSTED-E for manual verification.

Interpretation: BUSTED-E typically reduces false positive selection calls. In one analysis, UROD gene significance dropped from p=0.006 (BUSTED) to p=0.50 (BUSTED-E), with selection signal absorbed by error class [10].

Workflow Visualization

Title: How Alignment Errors Impact Phylogenetic Inference and Mitigation Strategies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Phylogenomic Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Tools | BWA-MEM2, PRANK-C | Map reads to reference genomes | PRANK-C particularly robust for selection analysis [10] |

| Orthology Inference | Phyling, OrthoFinder | Identify orthologous genes across species | Phyling uses profile-based approach for scalability [14] |

| Variant Callers | GATK, SAMtools | Identify genetic variants from alignments | Critical for cross-species comparisons [12] |

| Selection Analysis | BUSTED-E, PAML | Detect positive selection | BUSTED-E incorporates error modeling [10] |

| Tree Inference | IQ-TREE, RAxML-NG, ASTRAL | Phylogenetic tree construction | Concatenation vs. consensus approaches available [14] |

| Error Detection | BUSTED-E, manual inspection | Identify alignment artifacts | Essential for reliable phylogenetic inference [10] |

Linking Evolutionary History to Biodiversity and Trait Diversity

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary considerations when selecting a reference genome for a cross-species alignment study? The key considerations are evolutionary distance and assembly quality. For closely related species, you can use a high-quality reference genome from a closely related organism due to high genomic synteny [12]. For more distantly related species, a high-quality, chromosome-level assembly from the best-studied species in the clade is preferable. Always prioritize assemblies with fewer gaps and high sequencing depth over draft-quality assemblies, as the latter can contain errors that bias biological conclusions [12].

FAQ 2: My cross-species alignment shows high coverage, but my variant calls have an unusually high number of putative deleterious mutations. What could be the cause? This pattern often indicates a problem with the reference genome or the alignment itself, but it can also be a true biological signal. First, ensure you are not using a draft-quality assembly with known errors [12]. If the reference is validated, this pattern could accurately reflect the population history of your study species. Low genetic diversity and a high burden of deleterious variants are genomic signatures of endangered species with recent population declines [15]. Compare your findings to the species' conservation status.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between functional non-coding sequences and neutrally evolving sequences in a multi-species alignment? The strategy involves comparing species at different evolutionary distances [11]. Sequences conserved between distantly related species (e.g., human and pufferfish, which diverged ~450 million years ago) are almost certainly under functional constraint and are often coding exons. Sequences conserved between moderately related species (e.g., human and mouse, diverged ~80 million years ago) can include both coding and functional non-coding elements, like regulatory regions. Adding a closely related species (e.g., human and chimpanzee) helps identify recently evolved sequences and species-specific traits [11].

FAQ 4: What is the difference between "conserved synteny" and a "conserved segment"? These terms describe different levels of conserved genome architecture. Conserved synteny means that groups of genes (orthologs) are located on the same chromosome in two different species, regardless of their order or orientation. A conserved segment (or conserved linkage) is a stricter definition; it means that the order of multiple orthologous genes is the same in the two species [11].

FAQ 5: Can I use a cross-species alignment to test adaptive versus non-adaptive evolutionary hypotheses? Yes, this is a primary application of comparative genomics. To test an adaptive hypothesis, you must first construct a null model. In evolution, a null model often explains a trait as arising through non-adaptive processes like mutation accumulation or genetic drift [16]. For example, the mutation accumulation (MA) model is a null hypothesis for aging, positing that deleterious mutations with late-acting effects persist because natural selection is too weak to remove them. To argue for adaptation, you must provide evidence that your observation (e.g., the rate of aging) is too pronounced to be explained by the null model alone [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Alignment Coverage and Mapping Rates

- Problem: A low percentage of your sequencing reads are successfully mapping to the reference genome.

- Solution:

- Verify Reference Genome Quality: Check the assembly quality of your reference genome. Prefer chromosome-level builds (like felCat9 for felids [12]) over fragmented draft assemblies.

- Check for Contamination: Ensure your DNA sample is not contaminated with foreign DNA.

- Assess Evolutionary Distance: The reference species may be too evolutionarily distant from your study species. Try a reference genome from a closer relative. High mapping rates (>90%) are achievable when aligning big cat genomes to the domestic cat reference, demonstrating the utility of this approach within families [12].

- Inspect Raw Read Quality: Use tools like FastQC to check for adapter contamination or poor sequencing quality.

Issue 2: Inability to Delineate Population Structure

- Problem: Variant data from cross-species alignment fails to reveal expected population structure.

- Solution:

- Increase Sample Size: The power to detect population structure increases with the number of individuals sequenced.

- Switch from Pooled to Individual Sequencing: Non-barcoded pooled sequencing (PoolSeq) can be limited in its ability to detect rare variants and delineate fine-scale population structure. Transitioning to individual whole-genome sequencing provides genotype data for each individual, which is superior for population analysis [12].

- Filter Variants Rigorously: Apply strict quality filters to your variant calls (SNVs) to minimize false positives that can obscure biological signals.

Issue 3: High Heterozygosity Complicating Genome Assembly

- Problem: Difficulty in achieving a contiguous genome assembly for a species, often correlated with high heterozygosity [15].

- Solution:

- Use Specialized Assemblers: Employ assembly algorithms designed for highly heterozygous genomes.

- Utilize Long-Read Technologies: Sequence using long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to span repetitive and heterozygous regions.

- Employ Proximity Ligation: Techniques like Hi-C can scaffold a fragmented assembly into chromosome-length scaffolds, dramatically improving contiguity, even for challenging genomes [15].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Exemplar Alignment and Variant Call Metrics from a Cross-Species Study in Felids [12]

This table summarizes key quantitative outcomes from a study that aligned three big cat species to the domestic cat (Felis catus) reference genome (felCat9), providing a benchmark for expected results.

| Species | Read Pairs Mapped (Millions) | Properly Paired & Mapped | Biallelic SNVs Called | Transitions (Ts) | Transversions (Tv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) | 170 (avg.) | 94% | 38,839,061 | 26,430,702 | 12,408,359 |

| Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia) | 627 (avg.) | 93% | 15,504,143 | 9,124,699 | 4,285,891 |

| Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) | 251 (avg.) | 95% | 13,414,953 | 10,472,528 | 5,030,622 |

Table 2: Genetic Diversity Metrics from the Zoonomia Project for Conservation Prioritization [15]

This table illustrates how reference genome metrics from a single individual can inform conservation status. SoH (Segments of Homozygosity) is a robust metric less affected by assembly contiguity.

| Species / Grouping | Metric | Value / Correlation | Conservation Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 126 DISCOVAR Assemblies | Correlation (Overall Heterozygosity vs. SoH) | Pearson's r = -0.56 | Confirms that lower diversity is linked to more homozygous stretches. |

| Giant Otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) | Low diversity & high deleterious variants | Found | Consistent with known population decline; has higher recovery potential than sea otters [15]. |

| General Finding | Heterozygosity in threatened species | Generally lower | A genome from a single individual can help identify at-risk populations [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cross-Species SNV Discovery Using a Reference Genome

This methodology is adapted from a study that successfully identified single nucleotide variants in big cats by aligning to the domestic cat genome [12].

- DNA Source: Obtain high-quality genomic DNA from the target non-model species. DNA can be from tissue, blood, or cell cultures. The Frozen Zoo at San Diego Zoo Global is a key resource for endangered species [15].

- Sequencing: Perform whole-genome sequencing on an Illumina platform. For individual samples, aim for a minimum coverage of 10-15x. For non-barcoded pooled sequencing (PoolSeq), pool DNA from multiple individuals in equimolar ratios and sequence to a higher depth (e.g., >25x) to ensure coverage of rare alleles [12].

- Alignment: Map the sequenced reads to a high-quality reference genome (e.g., felCat9 for felids) using a standard aligner like BWA-MEM.

- Variant Calling: Call biallelic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in diploid mode for all samples using a caller like GATK HaplotypeCaller or SAMtools/bcftools.

- Variant Annotation and Filtering: Annotate variants using a tool like SnpEff and the reference genome's annotation. Apply quality filters (e.g., on depth, quality score, and mapping quality) to generate a high-confidence set of variants.

- Downstream Analysis: Use the filtered SNVs for population structure analysis (e.g., with ADMIXTURE), calculating nucleotide diversity (π), and enrichment analysis of fixed and species-specific SNVs.

Protocol 2: Assessing Phylogenetic Diversity and Evolutionary Constraint with a Multi-Species Alignment

This protocol is based on the design and implementation of large-scale comparative genomics projects like Zoonomia [15].

- Species Selection: Maximize evolutionary branch length by selecting at least one species from each family within the clade of interest. Prioritize species of medical, biological, or conservation concern.

- Genome Assembly & Curation: Generate genome assemblies using a consistent method (e.g., DISCOVAR de novo for short-read contigs [15]) to minimize technical variation. For a subset, perform proximity ligation (Hi-C) to create chromosome-level scaffolds.

- Whole-Genome Alignment: Use a specialized pipeline (e.g., CACTUS) to create a multiple whole-genome alignment of all selected species, independent of a single reference genome.

- Measuring Constraint: Identify evolutionarily constrained regions by detecting nucleotides that have remained unchanged across millions of years of evolution more than expected by chance alone. This is powerful for annotating functional genomes [15].

- Linking to Traits: Overlap species-specific genetic changes (e.g., accelerated evolution, conserved non-coding elements) with phenotypic data to generate hypotheses about the genetic basis of traits like venom production or cancer resistance [15].

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Cross-Species Variant Discovery Workflow

Diagram 2: Evolutionary Hypothesis Testing Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Reference Genome | A chromosome-level assembly of a closely related or model species used for read alignment and variant discovery. Essential for providing genomic context [12]. |

| The Frozen Zoo (San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance) | A biorepository storing renewable cell cultures from over 1,100 taxa, including many endangered species. A critical source of DNA for non-model organism genomics [15]. |

| Whole-Genome Alignment (WGA) | A multitool for scientific discovery. Enables the identification of evolutionarily constrained regions and species-specific changes by comparing multiple genomes simultaneously [15]. |

| Orthologous Sequences | Genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation. Comparisons between orthologs are critical for identifying functional elements [11]. |

| Paralogous Sequences | Genes related by duplication within a genome. Comparisons between paralogs are more divergent and less informative for cross-species functional analysis than orthologs [11]. |

The Limitation of Traditional Statistics and the Rise of Phylogenetic Comparisons

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main limitations of traditional statistical methods in genomic analysis? Traditional statistics often assume that data points are independent and identically distributed. However, in cross-species genomic studies, species are related through an evolutionary tree, violating this core assumption. This can lead to:

- Increased False Positives: Failure to account for shared evolutionary history (phylogenetic non-independence) can inflate Type I errors, mistakenly identifying patterns as significant.

- Oversimplified Models: Traditional methods struggle to model complex evolutionary processes like gene flow, hybridization, and incomplete lineage sorting, which are common in genomic datasets [5].

- Inaccurate Conclusions: Without a phylogenetic framework, it is easy to misinterpret shared genetic similarities as evidence of direct relationship or recent function, when they may be due to ancestral traits or convergent evolution [17].

FAQ 2: How do phylogenetic comparisons address the problem of non-independence? Phylogenetic comparative methods explicitly incorporate the evolutionary relationships among species into the statistical model. By using a phylogenetic tree, these methods:

- Model Covariance: They treat species as related tips on a tree, with their expected covariance based on shared branch lengths.

- Distinguish Homology from Homoplasy: They help differentiate between similarities due to common descent (homology) and those arising independently (homoplasy or convergent evolution) [17].

- Provide an Evolutionary Framework: This allows researchers to test hypotheses about trait evolution, selection, and adaptation in a statistically robust manner.

FAQ 3: What is the difference between a phylogenetic tree and a phylogenetic network, and when should I use a network? You should use a phylogenetic network when your data shows strong, conflicting signals that cannot be explained by a simple tree-like evolutionary history [5].

| Feature | Phylogenetic Tree | Phylogenetic Network |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Model | Assumes strictly divergent, tree-like evolution. | Generalizes trees to incorporate reticulate events like hybridization and gene flow. |

| Visual Structure | Strictly branching (bifurcating). | Includes both branches and reticulations (nodes with two incoming edges). |

| Best Used For | Scenarios where vertical descent is the primary evolutionary process. | Scenarios involving hybridization, horizontal gene transfer, or hybrid speciation [5]. |

FAQ 4: My phylogenetic analysis shows conflicting signals. How can I determine if it's due to incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) or hybridization? Distinguishing between ILS and hybridization is a key challenge. You can approach it as follows:

- Use Specific Methods: Employ methods based on the Network Multi-Species Coalescent (NMSC), which are designed to model both ILS and hybridization simultaneously [5].

- Analyze Gene Tree Variation: Compare gene trees from across the genome. While both processes cause gene tree discordance, hybridization creates specific patterns that can be detected.

- Leverage Hybridization Tests: Use statistical tests like Patterson's D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) to detect signals of gene flow between lineages. However, be aware that these tests can be sensitive to violations of assumptions and perform poorly with multiple or ghost reticulations [5].

FAQ 5: How can phylogenetic analysis be applied in drug discovery? Phylogenetic analysis is crucial for identifying and validating new drug targets [18].

- Target Identification: It helps pinpoint evolutionarily conserved regions in proteins (e.g., enzymes, receptors) that are crucial for function and can be targeted by drugs.

- Understanding Pathogen Evolution: By reconstructing the phylogenetic history of pathogens, researchers can track the emergence and spread of drug-resistant strains, informing drug and vaccine design [18].

- Natural Product Discovery: A correlation between phylogeny and biosynthetic pathways can predict which related plant species are likely to produce similar bioactive compounds, streamlining the selection of candidates for chemical analysis [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Weak Support for Phylogenetic Clades Potential Cause: The evolutionary model may be misspecified, or the data may contain conflicting signals from processes like Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS). Solution:

- Step 1 - Model Selection: Use model selection tools (e.g., in IQ-TREE) to find the best-fit nucleotide or amino acid substitution model for your data [18].

- Step 2 - Data Exploration: Consider partitioning your data (by gene, codon position) and analyzing partitions separately to identify conflicting signals.

- Step 3 - Method Upgrade: If ILS is suspected, switch to a method that explicitly models it, such as coalescent-based species tree methods (e.g., ASTRAL) or phylogenetic network methods (e.g., SNaQ) that account for both ILS and hybridization [5].

Problem 2: Detecting Reticulate Evolution but Unclear Interpretation Potential Cause: Challenges in biologically interpreting the inferred phylogenetic network, particularly the direction of gene flow or the nature of the hybridization event. Solution:

- Step 1 - Understand Reticulation Parameters: In a network, a reticulation vertex has an inheritance probability (γ), which denotes the proportion of genetic material the hybrid lineage inherited from one parent. A value of 0.5 suggests symmetrical hybridization, while values close to 0 or 1 suggest asymmetrical introgression [5].

- Step 2 - Distinguish Event Types: Be cautious in interpretation. A γ of 0.5 could indicate an F1 hybrid species or repeated backcrossing with both parents. The method alone may not distinguish between recent and ancient events without additional biological evidence [5].

- Step 3 - Incorporate External Evidence: Use information from geography, morphology, or known reproductive biology to constrain and validate the plausible biological interpretations of the network.

Problem 3: Computational Limitations with Large Genomic Datasets Potential Cause: Phylogenetic analyses, especially Bayesian inference or large bootstrap analyses, are computationally intensive and time-consuming. Solution:

- Step 1 - Use Efficient Software: Opt for fast and memory-efficient programs like IQ-TREE for maximum likelihood analysis [18].

- Step 2 - Reduce Data Complexity: For initial exploration, use a subset of data (e.g., one representative per species) or a reduced set of informative sites.

- Step 3 - Leverage High-Performance Computing (HPC): Scale your analyses by utilizing HPC clusters or cloud computing resources.

- Step 4 - Explore Scalable Network Methods: Newer methods for inferring explicit phylogenetic networks are becoming more scalable and effective with hundreds of loci, making them applicable to typical phylogenomic datasets [5].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Testing for Phylogenetic Signal in Chemical Traits This protocol is used to determine if the production of specific chemical compounds (e.g., alkaloids) is correlated with the evolutionary relationships among species [17].

- Sample Collection: Gather plant material from a taxonomically diverse set of species within a clade of interest (e.g., Amaryllidoideae).

- DNA Sequencing & Phylogeny Reconstruction: Sequence multiple DNA regions (e.g., ITS, matK) from all samples. Use parsimony and Bayesian inference to reconstruct a robust phylogenetic hypothesis [17].

- Chemical Profiling: Extract and analyze specialized metabolites from each species using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). Identify and quantify the diversity of compounds, such as different alkaloid types.

- Bioactivity Assay: Perform relevant bioassays (e.g., acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition for Alzheimer's research) on the extracts [17].

- Statistical Analysis: Use comparative phylogenetic methods (e.g., Blomberg's K, Pagel's λ) to test whether chemical diversity and bioactivity show a significant phylogenetic signal.

Quantitative Data from a Model Study (Amaryllidoideae) [17] The table below summarizes the data sources and their contribution to a phylogenetic analysis, demonstrating the power of combined evidence.

| DNA Region | Number of Aligned Characters | Potentially Parsimony-Informative Characters (%) | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | 953 | 502 (53%) | The most informative individual region. |

| Plastid Combined | 3182 | 480 (15%) | Provided strong support for major lineages. |

| Total Evidence | 5861 | 1086 (19%) | Resolved 87% of clades, the highest of any analysis. |

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Target Identification in Pathogens This methodology helps identify conserved and pathogen-specific proteins as potential drug targets [18].

- Genome Assembly: Collect or sequence genomes for multiple strains and species of a pathogen (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and related non-pathogens.

- Gene Family Identification: Use orthology prediction tools to group genes into families across all genomes.

- Phylogenetic Profiling: For each gene family, reconstruct a phylogenetic tree to identify:

- Genes that are conserved and essential in the pathogen.

- Genes that are absent from the human host.

- Prioritization: Prioritize candidate targets that are conserved across the pathogen, present in a broad range of strains, and absent or highly divergent in the host to minimize off-target effects [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Phylogenomic Analysis |

|---|---|

| IQ-TREE | A software for maximum likelihood phylogenomic inference. It incorporates model selection to find the best-fit evolutionary model, making phylogenetic inference more accurate and robust [18]. |

| Patterson's D-Statistic | A hybridization test used to detect gene flow between lineages by analyzing patterns of allele sharing among four taxa. It is practical for identifying specific reticulate events [5]. |

| Vega Visualization Grammar | A higher-level language for creating customizable, interactive visualizations. It is useful for generating complex phylogenetic trees and networks from JSON specs, aiding in data exploration and presentation [19]. |

| Multi-Species Coalescent Model | A population genetics model that accounts for gene tree-species tree discordance caused by Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS). It is fundamental for delimiting species and analyzing traits from genomically diverse datasets [5]. |

| Phylodynamic Modeling | A framework that combines phylogenetic data with epidemiological information. It is used to simulate and predict the spread of infectious diseases, informing the timely design of drug therapies and vaccines [18]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Traditional vs phylogenetic analysis workflow.

Diagram 2: Phylogenetic analysis for drug discovery.

Advanced Methods for Phylogenetic Inference from Genomic Data

Cross-species genome alignment is a foundational step in resolving phylogenetic diversity. It allows researchers to identify conserved functional elements, understand evolutionary constraints, and pinpoint rapidly changing genomic regions. For phylogenetic studies spanning divergent species, the choice of alignment tool is critical, as it must capture homologous sequences separated by vast evolutionary distances. The core challenge lies in balancing the exceptional sensitivity required to detect these distant homologies with the computational speed needed to process genome-scale data. Among the available tools, lastZ has been the long-standing benchmark for sensitivity, while its modern, GPU-accelerated derivative, KegAlign, promises to maintain this sensitivity at a fraction of the runtime [20] [21]. This technical support center addresses the specific issues researchers encounter when employing these tools in demanding cross-species phylogenetic projects.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is lastZ often recommended for cross-species alignment over faster tools like minimap2?

A1: lastZ is renowned for its superior sensitivity when aligning evolutionarily divergent sequences. While tools like minimap2 are dramatically faster, lastZ excels at finding homologies between genomes that have undergone significant sequence change. Benchmarking tests show that lastZ consistently generates end-to-end alignments across a wide range of sequence divergence (from 0% to 40%), and its alignments cover the vast majority of protein-coding exons in comparisons between species as distant as human and mouse [20] [21]. This sensitivity is crucial for phylogenetic studies that include deeply divergent taxa.

Q2: What is the primary performance bottleneck when running lastZ on large genomes?

A2: The main bottleneck is the immense computational time required. A standard mammalian whole-genome alignment using lastZ can take approximately 2,700 CPU hours. Scaling this to align 100 vertebrate genomes with a human reference would take an estimated 30 CPU years, making lastZ the primary obstacle for large-scale phylogenetic alignment projects [20] [21].

Q3: How does KegAlign address the speed limitations of lastZ?

A3: KegAlign is a GPU-enabled refactoring of the lastZ algorithm. It introduces a novel diagonal partitioning parallelization strategy and leverages advanced NVIDIA GPU features like Multi-Instance GPU (MIG) and Multi-Process Service (MPS). This optimization allows KegAlign to compute a human-mouse alignment in under 6 hours on a single node with an NVidia A100 GPU and 80 CPU cores, representing a speedup of approximately 150 times over lastZ without sacrificing sensitivity [20] [21].

Q4: What are the common hardware utilization problems with earlier GPU-accelerated aligners like SegAlign?

A4: SegAlign, a predecessor to KegAlign, suffered from severe hardware underutilization due to tail latency. The tool partitioned input sequences into equally-sized segments, which did not translate to equally-sized computational workloads. For closely related genomes (e.g., human-chimp), some segment pairs required vastly more time for gapped extension than others (up to 10,000 times longer than the median). This caused most CPU and GPU resources to sit idle while waiting for a few long-running tasks to complete, a problem that could not be solved by simply adding more hardware [20].

Q5: How should I choose alignment parameters for species at different evolutionary distances?

A5: Alignment strategy should be tailored to the evolutionary divergence of the species being compared. The following table summarizes recommended presets and tools for different scenarios [22]:

| Evolutionary Distance | Example Species Pair | TimeTree (MYa) | Recommended Aligner | Suggested Preset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same Species | Human (build 38) vs. Human (build 37) | 0 | BLAT, GSAlign | -tileSize=11 -minScore=100 -minIdentity=98 (BLAT) |

| Near / Primate | Human vs. Chimpanzee | 6.7 | lastZ / KegAlign | primate or E=30 H=3000 K=5000 L=5000 M=10 [22] |

| Medium / General | Human vs. Mouse | 90 | lastZ / KegAlign | general or E=30 H=3000 K=5000 L=5000 M=10 [22] |

| Far / Distant | Human vs. Chicken | 312 | lastZ / KegAlign | far or E=30 H=2000 K=2200 L=6000 M=50 O=400 T=2 [22] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Extremely Long Runtime with lastZ

Symptoms: An alignment job is taking days or weeks to complete, severely hampering research progress.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large, divergent genomes | Check the sizes and estimated divergence of your input genomes. | Switch from lastZ to KegAlign to leverage GPU acceleration [20] [21]. |

| Suboptimal sensitivity settings | Review the parameters. Using default, high-sensitivity settings on large sequences is computationally expensive. | For an initial survey, use a lower-sensitivity preset (e.g., --notransition --step=20). Reserve high-sensitivity runs for final analyses [23]. |

| Inefficient sequence partitioning | The job is running on a single thread without any parallelization. | If KegAlign is not an option, partition the input sequences into smaller fragments (e.g., by chromosome or smaller chunks) and run lastZ jobs in parallel on a compute cluster [20]. |

Problem 2: Poor Alignment Sensitivity on Divergent Genomes

Symptoms: The resulting alignment fails to cover known functional elements (e.g., exons) when comparing distant species.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly aggressive speed-optimized tools | The aligner used (e.g., minimap2) is optimized for speed, not deep divergence. | Use lastZ or KegAlign as the primary aligner, as they are specifically designed for sensitivity across evolutionary timescales [20] [21]. |

| Incorrect scoring parameters | Check if the scoring matrix and parameters match the evolutionary distance. | Use evolutionarily-informed parameter presets. For distant species, use the "far" preset with parameters like H=2000 K=2200 L=6000 which are tuned for lower sequence similarity [22]. |

| Algorithmic limitations | The tool uses a protein-level rather than nucleotide-level comparison, missing non-coding regions. | For aligning non-coding UTRs or other non-translated sequences, a nucleotide-level tool like lastZ/KegAlign is the only option [24]. |

Problem 3: Low Hardware Utilization with KegAlign/SegAlign

Symptoms: GPU and CPU usage metrics show significant idle time, despite a running job.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| CPU/GPU workload imbalance (Tail Latency) | Monitor per-core CPU usage. One or a few cores are at 100% while others are idle. | This was a key flaw in SegAlign. KegAlign's diagonal partitioning strategy is specifically designed to mitigate this by creating more balanced work units. Ensure you are using KegAlign, not SegAlign [20]. |

| GPU data starvation | GPU utilization drops sharply after an initial period, while CPUs remain busy. | This is caused by back pressure from the gapped-extension stage. KegAlign's use of MPS (Multi-Process Service) helps optimize GPU workload scheduling and communication to reduce idle time [20] [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Alignment Sensitivity and Coverage

This protocol is used to evaluate how well an aligner recovers homologous regions between divergent genomes, such as in a phylogenetic context.

- Input Preparation: Create a set of "homologous" sequence pairs of varying lengths (e.g., 1kb, 2kb, 5kb, 10kb) with simulated divergence from 0% to 40% in 1% increments. Add random 1,000 nucleotide flanks to the 5' and 3' ends of each sequence [20] [21].

- Alignment Execution: Run the target aligners (e.g., lastZ, KegAlign, minimap2) on these sequence pairs using their recommended parameters for divergent sequences.

- Sensitivity Calculation: For each alignment output, calculate the alignment coverage, defined as the fraction of the original homologous sequence included in the final alignment block.

- Visualization and Analysis: Plot alignment coverage against sequence divergence and length. A sensitive aligner will maintain high coverage even at high divergence rates [20] [21].

- Validation with Biological Data: As a validation step, perform a whole-genome alignment (e.g., human vs. mouse) and compute the fraction of protein-coding exons from the reference genome that are covered by the alignments. Merge overlapping alignments and exons to eliminate redundancy before calculating coverage [20].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Runtime Performance and Hardware Utilization

This protocol assesses the computational efficiency of an aligner, which is critical for project planning on shared or limited resources.

- Baseline Establishment: Run a standard alignment task (e.g., human chromosome 1 vs. mouse chromosome 1) using a baseline tool like lastZ on a defined CPU-only system. Record the total wall-clock time and CPU time [20] [21].

- Test Execution: Run the same alignment task with the optimized tool (e.g., KegAlign) on a system with a capable GPU (e.g., containing an NVidia A100).

- Resource Monitoring: During the run, use system monitoring tools (e.g.,

nvtopfor GPU,htopfor CPU) to track:- GPU Utilization: The percentage of time the GPU is actively processing data.

- CPU Utilization: The per-core and overall CPU usage.

- Memory Usage: System and GPU memory consumption.

- Performance Analysis: Calculate the speedup as:

Baseline Runtime (lastZ) / Optimized Runtime (KegAlign). Analyze monitoring logs to identify hardware underutilization, such as tail latency where most resources wait for a few slow tasks [20]. - Data Presentation: Summarize key performance metrics in a table for clear comparison.

Table: Example Performance Benchmark (Human chr1 vs. Mouse chr1) [21]

| Tool | Hardware | Runtime | Relative Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| lastZ | CPU | ~208 minutes | 1x (Baseline) |

| minimap2 | CPU | ~0.6 minutes | ~347x faster |

| KegAlign | GPU (A100) + CPU | < 6 hours (full genome) | ~150x faster than lastZ |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core alignment process optimized by KegAlign and lastZ, highlighting the critical stages and bottlenecks.

Diagram Title: Genome Alignment Core Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Software and Hardware for Genomic Alignment

| Item Name | Function / Application | Notes for Phylogenetic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| lastZ | The sensitive, CPU-based pairwise aligner; the gold standard for detecting distant homologies. | Ideal for final, high-quality alignments of divergent taxa. Use provided presets (primate, general, far) based on evolutionary distance [23] [22]. |

| KegAlign | GPU-accelerated version of lastZ; maintains sensitivity while drastically reducing runtime. | Essential for large-scale phylogenetic projects with many genomes. Requires an NVIDIA GPU (e.g., A100) [20] [21]. |

| Conda | Package and environment management system. | Used for installing and managing versions of lastZ, KegAlign, and other bioinformatics tools in isolated environments [20] [21]. |

| Galaxy | Web-based, user-friendly platform for data analysis. | Provides a graphical interface for KegAlign, making it accessible to researchers without command-line expertise [20]. |

| NVidia A100 GPU | High-performance computing GPU. | The reference hardware for running KegAlign efficiently. Enables alignment of mammalian genomes in hours instead of weeks [20] [21]. |

| HPC Cluster | High-performance computing cluster with many CPU nodes. | The traditional infrastructure for running lastZ by parallelizing alignment jobs across thousands of sequence chunks [20]. |

Leveraging Deep Learning and Neural Networks for Phylogeny Reconstruction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of using deep learning over traditional methods for phylogeny reconstruction?

Deep learning addresses several key limitations of traditional phylogenetic methods. The primary advantages are:

- Speed and Scalability: Deep learning methods can analyze very large phylogenies and datasets much faster than traditional maximum likelihood or Bayesian approaches, which often involve computationally expensive calculations and tree optimizations [25]. Neural network computation times are constant, offering significant runtime savings, especially for alignments with long sequences and many taxa [26].

- Handling Model Complexity: Traditional methods struggle with complex evolutionary models that require solving sets of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) numerically, leading to instability and inaccuracy with large trees [25]. Deep learning, being a simulation-based and likelihood-free approach, bypasses these complex mathematical formulae entirely [25].

- Elimination of Summary Statistics: Unlike Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC), which relies on a potentially incomplete set of summary statistics to represent a tree, some deep learning approaches use a complete and compact vectorial tree representation. This avoids information loss and can be applied to any phylodynamic model [25].

FAQ 2: My deep learning model for phylogenetic parameter estimation is not performing well. What could be the issue?

Poor performance can stem from several sources related to both the data and the model design:

- Data Violating Model Assumptions: If your empirical data violates the assumptions of the models used to generate the training data, performance will suffer. Common issues include branch length heterogeneity (leading to long-branch attraction), compositional heterogeneity, and site saturation [27]. It is crucial to detect and ameliorate these artefacts before analysis.

- Training-Testing Data Mismatch: Deep learning models for phylogenetics are often trained on simulated data. If the simulation model is too simple or does not reflect the complexity and diversity of your real biological data, the model's generalizability to empirical data will be limited [28].

- Inadequate Tree Representation: The choice of how a phylogenetic tree is represented as input to the neural network is critical. Using a limited set of summary statistics might omit important features of the tree. Consider using a Compact Bijective Ladderized Vector (CBLV) representation, which preserves all information about the tree topology and branch lengths and is bijective [25].

FAQ 3: How can I integrate a new sequence into an existing, large phylogenetic tree efficiently?

A targeted approach using deep learning can significantly accelerate this process:

- Identify the Taxonomic Unit: Use a pretrained DNA language model (like DNABERT) fine-tuned on the taxonomic hierarchy of your existing tree. This model can identify the smallest taxonomic unit (e.g., genus or family) to which the new sequence belongs [28].

- Extract Informative Regions: Leverage the attention mechanisms of the transformer model to identify "high-attention regions" within the sequences of the identified taxonomic unit. These regions are potentially the most informative for phylogenetic construction [28].

- Update the Subtree: Instead of reconstructing the entire tree, only align and reconstruct a phylogeny for the sequences within the identified taxonomic unit using the extracted high-attention regions. This subtree can then be integrated back into the main tree, saving substantial computational time [28].

FAQ 4: Can deep learning help with phylogenetic model selection, and is it reliable?

Yes, deep learning can perform model selection rapidly and reliably.

- Method: Tools like ModelRevelator use deep neural networks to recommend a model of sequence evolution and determine whether to incorporate a Γ-distributed rate heterogeneous model, including an estimate of the shape parameter (α) [26].

- Reliability: This approach performs comparably with likelihood-based methods (e.g., ModelTest-NG, ModelFinder) but without the need for tree reconstruction, parameter optimization, or likelihood calculations. This makes it both accurate and drastically faster, preventing computational bottlenecks in your analysis pipeline [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Dealing with Phylogenetic Artefacts and Incongruence

Incongruence between phylogenetic reconstructions from different datasets can be due to biological sources (e.g., Horizontal Gene Transfer, incomplete lineage sorting) or methodological errors. Before concluding biological causes, you must rule out methodological artefacts [27].

- Symptoms: Unexpected tree topologies, high support for likely incorrect relationships, conflicting results between different genes or analyses.

- Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Test for Compositional Heterogeneity: Use software like

BaCoCaorPhyloMAdto check if the nucleotide or amino acid composition is homogeneous across your taxa. A significant violation can attract compositionally similar taxa together artificially [27]. - Test for Branch Length Heterogeneity: Use methods such as

TreePuzzleor posterior predictive simulations to identify taxa with exceptionally long branches. Long-branch attraction is a major cause of strongly supported but incorrect topologies [27]. - Check for Site Saturation: Plot transitions and transversions against genetic distance. A plateau indicates saturation, meaning the phylogenetic signal at these sites is obscured and can be misleading [27].

- Addressing the Issues:

- For compositional and branch length heterogeneity, consider using more complex models that account for these factors, such as site-heterogeneous models (e.g., CAT) or non-stationary models [27].

- For saturated data, consider removing the fastest-evolving sites or using models specifically designed for such data [27].

- Test for Compositional Heterogeneity: Use software like

Table 1: Common Phylogenetic Artefacts and Detection Methods

| Artefact Type | Description | Effect on Tree | Detection Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branch Length Heterogeneity | Some taxa have much longer branches due to elevated evolutionary rates or sampling gaps. | Long-branch attraction: distantly related long-branched taxa cluster together. | TreePuzzle, Posterior Predictive P-values [27] |

| Compositional Heterogeneity | Violation of the assumption that sequences have similar nucleotide/amino acid compositions. | Taxa with similar base compositions cluster together artificially. | BaCoCa, PhyloMAd [27] |

| Site Saturation | Multiple substitutions have occurred at a site, obscuring the true phylogenetic signal. | Loss of resolution, underestimation of branch lengths, incorrect groupings. | Saturation plots (Ti/Tv vs. distance) [27] |

Issue 2: Implementing a Deep Learning Pipeline for Phylodynamics

This guide outlines the workflow for using a tool like PhyloDeep to estimate epidemiological parameters from a pathogen phylogeny [25].

- Symptoms: You have a large phylogenetic tree from a pathogen outbreak and need to infer key parameters (e.g., reproduction number ( R_0 ), rate of becoming infectious) quickly, but traditional methods are too slow or unstable.

- Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Input Preparation: Prepare your rooted phylogenetic tree in Newick format.

- Tree Representation Choice: Decide on the input representation for the neural network.

- Option A (Summary Statistics): Calculate a vector of 83+ summary statistics from your tree, including measures of branch lengths, tree topology, and lineage-through-time data [25].

- Option B (CBLV Representation): Convert your tree into a Compact Bijective Ladderized Vector. This bijective representation preserves all information from the tree topology and branch lengths and is often more accurate [25].

- Model Selection and Execution: Choose the appropriate pre-trained neural network model within PhyloDeep based on the phylodynamic model you wish to use (e.g., Birth-Death, Birth-Death-Exposed-Infectious). Run the analysis.

- Output and Validation: The output will be an estimation of the epidemiological parameters. It is good practice to validate these results on simulated datasets with known parameters if possible [25].

The following diagram illustrates the two primary deep learning pathways for phylogenetic analysis as implemented in tools like PhyloDeep.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Models for Deep Learning Phylogenetics

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| PhyloDeep | A software tool that uses deep learning for fast parameter estimation and model selection from phylogenies. | Estimating the basic reproduction number (R0) from a large SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny [25]. |

| ModelRevelator | A deep learning-based tool for phylogenetic model selection. It recommends a model of sequence evolution and estimates rate heterogeneity. | Quickly determining the best-fit nucleotide substitution model (e.g., GTR+Γ) for a large genomic alignment before tree inference [26]. |

| PhyloTune | A method using a pretrained DNA language model (DNABERT) to efficiently place new sequences into an existing phylogenetic tree. | Integrating a newly sequenced pathogen genome into a large existing reference tree without realigning all data [28]. |

| DNA Language Models (e.g., DNABERT) | A transformer-based model pre-trained on DNA sequences to understand genomic language. Can be fine-tuned for taxonomic classification. | Used by PhyloTune to identify the taxonomic unit of a new sequence and extract phylogenetically informative regions [28]. |

| Compact Bijective Ladderized Vector (CBLV) | A compact, bijective vector representation of a phylogenetic tree that includes topology and branch length information. | Providing a complete representation of a tree as input to a convolutional neural network (CNN) for analysis [25]. |

The Power of Phylogenetic Networks to Model Hybridization and Introgression

The Limitation of Trees in the Era of Genomics

For decades, the phylogenetic tree has been the central model for representing evolutionary relationships. However, the advent of phylogenomics—the analysis of genome-scale data—has revealed widespread evolutionary processes that trees cannot adequately represent. A key finding is species/gene tree incongruence, where different genomic regions tell conflicting evolutionary stories. This incongruence arises primarily from two processes:

- Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS): The retention of ancestral genetic polymorphisms through speciation events.

- Hybridization and Introgression: The exchange of genetic material between different species or lineages [29].

When a trait's evolutionary path conflicts with the species tree, the conflict was traditionally explained as homoplasy (independent gain or loss of the trait) or hemiplasy (the trait follows a gene tree that is incongruent with the species tree due to ILS). Phylogenetic networks introduce a third explanation: xenoplasy, where a trait is shared due to inheritance across species boundaries via hybridization or introgression [29].

Key Concepts: Hemiplasy vs. Xenoplasy

Understanding the difference between hemiplasy and xenoplasy is critical for diagnosing evolutionary histories.

- Hemiplasy: Requires deep coalescence events, where ancestral polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events. The trait pattern is incongruent with the species tree but congruent with a gene tree that differs from the species tree due to ILS [29].

- Xenoplasy: Does not require deep coalescence. It results from the direct transfer of genetic material (and the traits they encode) between species via hybridization or introgression. The trait pattern is explained by a network, not a tree [29].

Table: Distinguishing Between Sources of Phylogenetic Incongruence

| Term | Definition | Primary Cause | Implied Evolutionary Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homoplasy | Trait similarity not due to common descent; independent evolution. | Convergent evolution or evolutionary reversal. | Trait gained or lost independently in different lineages. |