Precision Calling: Optimizing NGS Variant Accuracy in Chemogenomic Screens for Drug Discovery

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) variant calling is foundational to interpreting chemogenomic screens, where accurately linking genetic perturbations to compound sensitivity is paramount.

Precision Calling: Optimizing NGS Variant Accuracy in Chemogenomic Screens for Drug Discovery

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) variant calling is foundational to interpreting chemogenomic screens, where accurately linking genetic perturbations to compound sensitivity is paramount. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the core principles of variant calling, best-practice methodologies for different variant types, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing pipelines, and rigorous frameworks for validation and benchmarking. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, including the impact of AI and multi-omics integration, this resource aims to empower scientists to enhance the reliability and actionability of their data, thereby accelerating target identification and therapeutic development.

The Bedrock of Precision: Core Concepts and Challenges in NGS Variant Calling

In chemogenomics, which explores the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, the accurate identification of genomic variants is a foundational pillar. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for uncovering the genetic determinants of drug response, resistance, and toxicity. However, the inherent limitations of sequencing technologies and the diverse nature of genomic alterations present significant challenges. Variants are broadly categorized by size and type: Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) involve changes to a single base; Insertions and Deletions (Indels) are typically under 50 bp; Copy Number Variations (CNVs) are large-scale duplications or deletions; and Structural Variations (SVs), including balanced rearrangements like inversions, are generally 50 bp or larger [1]. The sophistication of variant calling is ever-increasing, yet the performance of detection algorithms varies dramatically depending on the variant type, genomic context, and sequencing technology used [2] [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of variant calling performance, synthesizing recent benchmarking data to inform robust experimental design in chemogenomic screens. A precise understanding of the variant landscape enables researchers to better correlate genetic features with compound activity, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development.

Performance Comparison of Variant Callers and Technologies

The accuracy of variant detection is influenced by a complex interplay of sequencing technology and the computational algorithm employed. The tables below summarize key performance metrics from recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing for Variant Detection

| Variant Type | Sequencing Technology | Key Performance Findings | Notable Top-Performing Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs | Short-Read (Illumina) | High accuracy, similar to long-reads in non-repetitive regions [1]. | DeepVariant [1] [3] |

| Long-Read (ONT/PacBio) | Matches or exceeds short-read accuracy; deep learning tools achieve F1 scores >99.9% [3]. | Clair3, DeepVariant [3] | |

| Indels | Short-Read (Illumina) | Recall for insertions >10 bp is poor compared to long-reads; performance decreases in repetitive regions [1]. | GATK [1] |

| Long-Read (ONT/PacBio) | Superior accuracy for all indels; deep learning tools achieve F1 scores >99.5% [3]. | Clair3, DeepVariant [3] | |

| Structural Variants (SVs) | Short-Read (Illumina) | Significantly lower recall in repetitive regions; union of multiple algorithms enhances detection [4] [1]. | DELLY, LUMPY, Manta, GRIDSS [4] |

| Long-Read (ONT/PacBio) | Higher sensitivity and precision, especially in repetitive regions and for complex SVs [1]. | cuteSV, Sniffles, pbsv [1] |

Table 2: Performance of Specific SV Detection Algorithms on Short-Read Data (GIAB Benchmark)

| Algorithm/Strategy | Recall (DEL) | Precision (DEL) | F1 Score (DEL) | Recall (INS) | Precision (INS) | F1 Score (INS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DELLY | 0.62 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.24 |

| LUMPY | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0.34 |

| Manta | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.43 | 0.97 | 0.60 |

| DRAGEN (Commercial) | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 0.75 |

| Union of 3 Algorithms | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.76 |

Data adapted from Duan et al., 2025 [4]. The union strategy combined Manta, MELT, and GRIDSS. DEL=Deletion, INS=Insertion.

Key Insights from Performance Data

- The Superiority of Ensemble Methods for SVs: For SV detection on short-read data, no single algorithm is universally optimal. A union strategy combining multiple callers (e.g., Manta, MELT, and GRIDSS) can achieve performance comparable to, and sometimes surpassing, sophisticated commercial software like DRAGEN, particularly for insertions [4]. Interestingly, expanding the ensemble beyond three well-chosen algorithms does not necessarily improve performance [4].

- The Rise of Deep Learning and Long-Reads: For SNVs and Indels, deep learning-based variant callers (Clair3, DeepVariant) applied to high-accuracy long-read data (e.g., ONT super-accuracy mode) are now setting a new standard, outperforming traditional methods and even challenging the historical primacy of Illumina short-reads [3].

- Context Matters: Repetitive Regions Are a Major Challenge: A critical finding across studies is that the performance of short-read-based variant callers for indels and SVs deteriorates significantly in repetitive regions, such as segmental duplications and simple tandem repeats [1]. Long-read technologies, by spanning these repetitive elements, maintain high accuracy [1].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Variant Callers

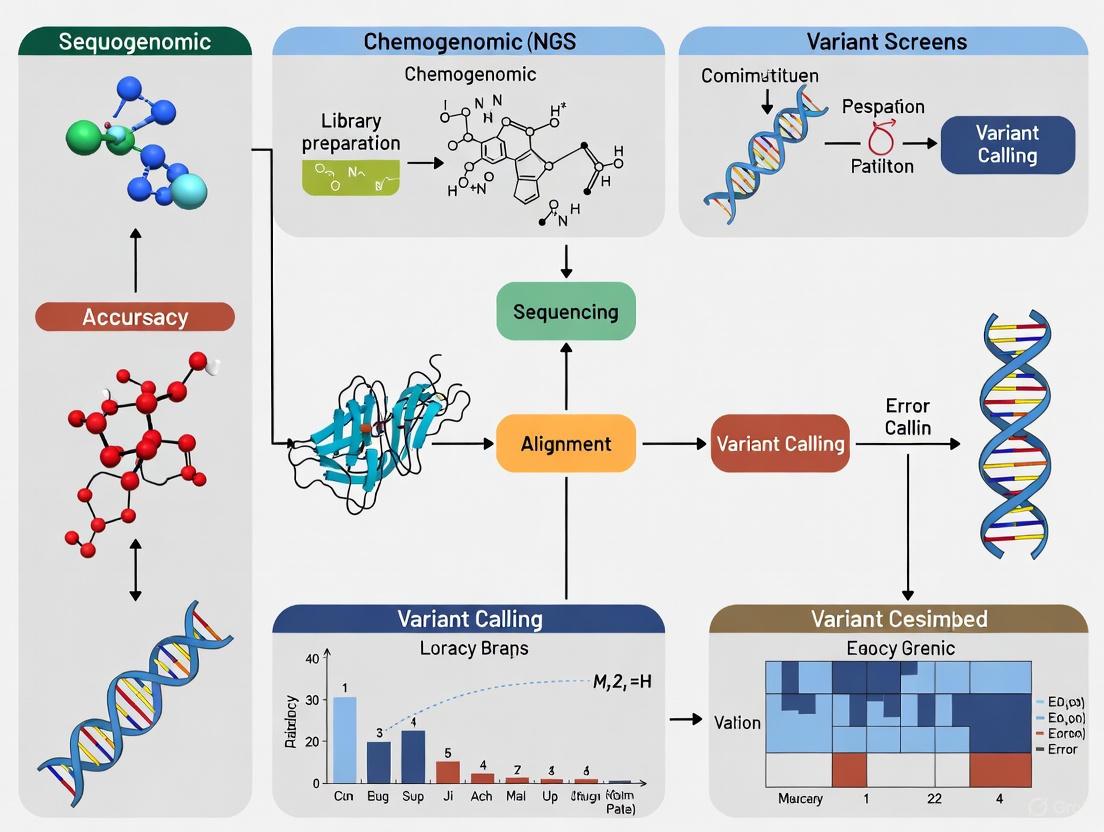

To generate the comparative data presented in this guide, benchmarking studies follow rigorous and standardized experimental workflows. The following diagram and protocol outline the common steps involved in evaluating variant detection performance.

Detailed Benchmarking Methodology

- Sample and Data Preparation: Benchmarking relies on well-characterized reference samples from consortia like the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Consortium (e.g., NA12878, HG002) [4] [1]. The same DNA extraction is used for both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (PacBio HiFi, ONT) sequencing to prevent culture-induced mutations from biasing results [3].

- Read Alignment and Variant Calling: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome (GRCh37/hs37d5). Short reads are typically aligned with

bwa mem, while long reads are aligned withminimap2[1]. A wide array of variant calling algorithms (e.g., 6 for SNVs, 12 for indels, 13 for SVs) are then run on the aligned data [1]. - Truth Set Construction: A high-confidence set of true variants is essential for evaluation. This is created by integrating data from multiple sources, including:

- GIAB benchmark sets [1].

- Long-read-based haplotype-resolved assemblies (e.g., from HGSVC) [1].

- Variants commonly identified by multiple long-read-based callers to ensure precision [1].

- For bacterial studies, a "pseudo-real" truthset may be generated by projecting real variants from a closely related donor genome onto a gold-standard reference [3].

- Performance Evaluation and Manual Inspection: Variant calls from each tool are compared against the truth set using

vcfevalorvcfdistto calculate precision, recall, and F1 scores [3]. To ensure the highest quality, a subset of variants, particularly indels, is often validated through manual visual inspection using tools like the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [1].

Successful variant detection and annotation require a suite of computational tools and genomic resources. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Variant Detection

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Variant Detection |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Materials | Genomic DNA from well-characterized human cell lines (e.g., HG002). | Provides a gold-standard benchmark for validating variant calls across platforms and algorithms [1]. |

| Variant Call Format (VCF) | A standardized text file format for storing gene sequence variations. | The primary output of variant callers; used for interoperability between different analysis tools [5]. |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) | A high-performance visualization tool for interactive exploration of large genomic datasets. | Enables manual inspection and validation of variant calls by visualizing read alignments [2]. |

| Ensembl VEP & ANNOVAR | Command-line tools for determining the functional consequences of variants (e.g., missense, frameshift). | Critical for annotating VCF files to predict the impact of variants on genes and proteins [6]. |

| CAVA (Clinical Annotation of VAriants) | A tool for providing standardized, clinically appropriate annotation of NGS data. | Resolves inconsistencies in indel annotation, ensuring compatibility with historical clinical data [5]. |

| BioRender | A web-based tool for creating scientific figures and illustrations. | Used to generate professional diagrams of workflows, signaling pathways, and results for publications. |

The landscape of NGS variant calling is evolving rapidly, driven by advancements in long-read sequencing and sophisticated deep learning algorithms. For chemogenomics researchers, the choice of technology and computational pipeline must be tailored to the variant types of interest. While short-read sequencing combined with ensemble calling strategies remains a powerful and cost-effective approach for population-scale studies, long-read technologies offer a compelling alternative for comprehensive variant discovery, particularly in complex genomic regions. The emerging paradigm emphasizes that there is no single "best" tool, but rather a need for refined, context-aware strategies. As the field moves forward, the integration of multiple data types and continuous benchmarking against curated truth sets will be paramount for defining the variant landscape with the accuracy required to power the next generation of chemogenomic discoveries.

In chemogenomic screens, which systematically explore the interactions between chemical compounds and genetic variants, the accuracy of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data analysis is paramount. These screens rely on precise variant calling to identify genetic modifiers of drug response, potential drug targets, and mechanisms of resistance. The standard NGS data analysis pipeline serves as the foundation for extracting meaningful biological insights from raw sequencing data, transforming billions of short DNA fragments into accurate genetic variants [7] [8]. Even minimal error rates in sequencing data—seemingly low at 0.1-1%—can translate to thousands of incorrect base calls across the human genome, severely compromising the identification of true somatic mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in chemogenomic studies [7]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of current NGS analysis methodologies, focusing on their performance characteristics and providing supporting experimental data to guide researchers in selecting optimal pipelines for precision oncology and chemogenomics research.

The Standard NGS Analysis Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The journey from raw sequencing output to biological insights follows a structured pathway with distinct computational steps. Each stage addresses specific data quality challenges and prepares the data for subsequent analysis, with the overall workflow managed by specialized systems that ensure reproducibility and efficiency [9].

Quality Control and Adapter Trimming

The initial critical stage involves assessing data quality and removing technical sequences. Raw sequencing data in FASTQ format contains not only sequence reads but also quality scores for each base, and potential contaminants such as adapter sequences [9].

- Purpose: To identify low-quality bases, sequence bias, and over-represented sequences that could skew downstream analysis [9].

- Common Tools: FastQC, fastp, and MultiQC are widely employed for quality assessment [9]. FastQC provides comprehensive quality metrics including per-base sequence quality, sequence duplication levels, and adapter contamination [9].

- Adapter Trimming: Tools like Cutadapt, Trimmomatic, and fastp remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases, significantly improving data quality for alignment [9].

Alignment to a Reference Genome

Processed reads are then mapped to a reference genome to identify their genomic origins.

- Purpose: To determine the precise location in the genome from which each sequencing read originated [9].

- Alignment Tools: BWA-Mem, Bowtie, HISAT2, and STAR are commonly used aligners [9]. BWA-Mem is particularly prevalent for DNA sequencing data [9] [8].

- Output: The alignment process produces BAM files (Binary Alignment/Map format), which store the aligned sequences and their mapping qualities [8].

Variant Calling

This crucial step identifies genetic differences (variants) between the sequenced sample and the reference genome.

- Purpose: To detect single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions (indels), and other genetic variations [9] [8].

- Approaches: Variant callers employ diverse algorithms, from traditional statistical methods to emerging deep learning approaches:

- Germline Variant Calling: GATK HaplotypeCaller, FreeBayes, and Platypus are established tools [8].

- Somatic Variant Calling: Mutect2 is specifically designed for identifying cancer-associated mutations [9].

- Deep Learning Methods: Clair3 and DeepVariant use convolutional neural networks for improved accuracy [3].

Variant Annotation and Filtering

Identified variants undergo biological interpretation through annotation and filtering.

- Purpose: To predict the functional consequences of variants and filter out technical artifacts [9].

- Annotation Tools: VEP (Variant Effect Predictor), ANNOVAR, and SnpEff provide information on variant consequences, such as whether they affect protein coding, regulatory regions, or splice sites [9].

- Filtering Resources: Databases like dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, and gnomAD help distinguish common polymorphisms from potentially disease-relevant mutations [9].

Comparative Analysis of Variant Calling Technologies

Performance Benchmarking Across Platforms and Tools

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal significant differences in variant calling accuracy across platforms and computational methods. A landmark study evaluating 14 bacterial species demonstrated that deep learning-based variant callers applied to Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) data outperformed traditional methods and even surpassed Illumina sequencing accuracy for both SNPs and indels [3].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Variant Calling Methods for Oxford Nanopore Technologies Data

| Variant Caller | Type | SNP F1 Score (%) | Indel F1 Score (%) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clair3 | Deep Learning | 99.99 | 99.53 | Overall accuracy |

| DeepVariant | Deep Learning | 99.99 | 99.61 | Indel calling |

| Medaka | Deep Learning | 99.80 | 98.20 | Fast processing |

| NanoCaller | Deep Learning | 99.70 | 97.50 | Complex variants |

| BCFtools | Traditional | 99.30 | 80.10 | Standard SNPs |

| FreeBayes | Traditional | 98.90 | 85.60 | Germline variants |

| Longshot | Traditional | 99.50 | 90.20 | Long read haplotyping |

Data adapted from eLife benchmarking study [3]

For Illumina platforms, the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) remains a widely adopted solution, particularly known for its robust variant discovery and genotyping capabilities [10] [9]. The Broad Institute's Best Practices workflow provides a standardized approach for processing Illumina data, though evaluations suggest that the improvements from certain preprocessing steps like base quality score recalibration may be marginal considering their computational cost [8].

Impact of Sequencing Technology on Variant Calling Accuracy

Different sequencing technologies exhibit characteristic error profiles that directly impact variant calling accuracy:

- Illumina Platforms: Generally display low error rates (0.26%-0.8%) but may show substitution errors in AT-rich or CG-rich regions [7] [11].

- Ion Torrent: Similar to 454 pyrosequencing, has limitations in homopolymer regions with an error rate of approximately 1.78% [7] [11].

- SOLiD: Utilizes a two-base encoding system that achieves a lower error rate of about 0.06%, though with shorter read lengths [7].

- Oxford Nanopore: Historically had higher error rates, but with the latest R10.4.1 pore and super-accuracy basecalling, median read identities can reach 99.93% (Q32) for duplex reads, enabling F1 scores >99.5% for both SNPs and indels when using deep learning variant callers [3].

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Error Profiles and Characteristics

| Platform | Typical Error Rate | Error Type | Read Length | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 0.26%-0.8% | Substitutions | Short (36-300 bp) | High-throughput screening |

| Ion Torrent | ~1.78% | Homopolymer indels | Short (200-400 bp) | Targeted sequencing |

| SOLiD | ~0.06% | Substitutions | Short (75 bp) | Variant validation |

| PacBio | Variable | Random errors | Long (10-25 kb) | Structural variants |

| Oxford Nanopore | <0.1% (sup duplex) | Random errors | Long (10-30 kb) | Comprehensive variant detection |

Data synthesized from multiple sources [7] [11] [3]

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Variant Calling Performance

Establishing Gold Standard Reference Sets

Rigorous benchmarking of variant calling pipelines requires well-characterized reference datasets where "ground truth" variants are known. The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium and Platinum Genomes project provide benchmark variants for human genomes, particularly for the extensively characterized NA12878 sample [8]. For bacterial genomics, a novel approach involves projecting real variants from closely related donor genomes (with ~99.5% average nucleotide identity) onto gold standard reference assemblies, creating biologically realistic variant distributions for benchmarking [3].

Protocol: Truthset Generation for Bacterial Genomes

- Generate high-quality reference assemblies using both ONT and Illumina reads

- Select donor genome with closest to 99.5% average nucleotide identity

- Identify variants between sample and donor using minimap2 and MUMmer

- Intersect variant sets and filter to remove overlaps and indels >50bp

- Apply variant truthset to sample's reference to create mutated reference

- Validate mutated reference against original donor genome [3]

Performance Assessment Metrics

Variant calling accuracy is typically evaluated using standard classification metrics:

- Precision: The proportion of called variants that are true positives (fewer false positives)

- Recall: The proportion of true variants that are detected (fewer false negatives)

- F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced metric [3]

Specialized tools like vcfdist are used for variant comparison, properly handling complex variants and differences in variant representation [3].

Visualization of the NGS Data Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete standard NGS data analysis pipeline, from raw sequencing data to biological insights, including key decision points for tool selection:

Diagram 1: Standard NGS analysis workflow with key computational steps and representative tools for each stage.

Workflow Management Systems

Modern NGS analysis relies on workflow managers that ensure reproducibility, scalability, and efficient resource utilization:

- Nextflow: A domain-specific language that enables portable and reproducible workflows, with active community-developed pipelines available through nf-core [9].

- Snakemake: A Python-based workflow management system that excels in creating transparent and flexible analysis pipelines [9].

- Galaxy: A web-based platform that provides an accessible interface for bioinformatics analysis, particularly valuable for researchers with limited computational expertise [9].

Accurate variant interpretation depends on comprehensive biological databases:

- Reference Genomes: GRCh38 (human) and species-specific references provide the coordinate systems for alignment [9].

- Population Databases: gnomAD, 1000 Genomes, and dbSNP contain information on population allele frequencies, helping filter common polymorphisms [9] [8].

- Functional Annotation: Ensembl, RefSeq, and UniProt provide gene models and functional information for consequence prediction [9].

Table 3: Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Resources for NGS Analysis

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management | Nextflow, Snakemake | Pipeline automation and reproducibility | Ensures consistent analysis across screens |

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Quality assessment and reporting | Identifies batch effects and technical artifacts |

| Alignment | BWA-Mem, STAR | Read mapping to reference genome | Critical for accurate variant detection |

| Variant Calling | GATK, Clair3, DeepVariant | Genetic variant identification | Detects drug-resistance mutations |

| Variant Annotation | VEP, ANNOVAR | Functional consequence prediction | Prioritizes variants affecting drug targets |

| Visualization | IGV | Manual variant inspection | Validates candidate variants in context |

| Benchmarking | vcfdist, GIAB resources | Performance assessment | Quantifies pipeline accuracy |

The field of NGS data analysis is undergoing rapid transformation, with deep learning approaches demonstrating remarkable improvements in variant calling accuracy. The latest benchmarking evidence suggests that Oxford Nanopore sequencing combined with deep learning variant callers like Clair3 can achieve F1 scores exceeding 99.5% for both SNPs and indels, potentially surpassing the accuracy of traditional Illumina-based pipelines [3]. For chemogenomic screens, where identifying true genetic modifiers of drug response is critical, these technological advances promise enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants and improved specificity in distinguishing genuine mutations from sequencing artifacts.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multimodal data, improving scalability for large-scale screens, and enhancing the detection of complex structural variations. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the establishment of rigorous benchmarking standards and reproducible analysis pipelines will remain essential for maximizing the value of NGS data in chemogenomics research and precision oncology.

In modern drug discovery, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for identifying and validating potential drug targets. The process of variant calling—identifying genetic variations from sequencing data—serves as the critical foundation upon which target discovery rests [12]. Inaccurate variant calling can create a cascade of errors, leading research down unproductive pathways, overlooking genuine therapeutic targets, and ultimately wasting substantial resources during development [13]. Within chemogenomic screens, where researchers systematically study interactions between chemical compounds and genetic variants, variant calling accuracy becomes particularly crucial as it directly influences our understanding of disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions [12] [14].

This guide examines how variant calling errors impact drug target discovery, compares the performance of various variant calling methods, and provides evidence-based recommendations for implementing optimal practices in genomic research. By understanding the sources and consequences of these errors, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and efficiency of their target discovery pipelines.

The Critical Role of Variant Calling in Drug Discovery Pipelines

From Sequence to Therapy: How Variant Calling Informs Target Discovery

Variant calling provides the essential genetic insights that drive multiple stages of the drug discovery pipeline [12]. Initially, population-scale sequencing studies leverage electronic health records to identify associations between genetic variants and specific disease phenotypes, highlighting potential therapeutic targets [12]. Once candidate targets emerge, researchers use loss-of-function mutation detection in combination with phenotype studies to validate target relevance and predict potential effects of therapeutic inhibition [12]. During drug design, variant calling informs this process by revealing details about genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [12]. Finally, in clinical development, accurate variant calling enables precise patient stratification for clinical trials based on genetics, leading to smaller, more targeted trials with higher success rates [12].

The connection between variant calling and successful drug development is further strengthened through innovative approaches like patient-derived organoids combined with NGS. This combination allows researchers to study genetic heterogeneity within diseases like cancer and understand how this diversity contributes to drug resistance and poorer outcomes [12]. As drug discovery increasingly embraces personalized medicine, variant calling helps clarify how drugs may affect different patients depending on their genetics, enabling the customization of treatments based on individual genetic profiles [12].

Consequences of Variant Calling Errors in Decision Making

Variant calling errors can significantly derail drug discovery efforts through multiple mechanisms. False positive variants may lead researchers to pursue nonexistent targets, while false negatives can cause genuine therapeutic opportunities to be overlooked [15] [13]. These errors are particularly problematic in complex genomic regions such as homopolymers, segmental duplications, and hard-to-map regions, which often coincide with medically relevant genes [15].

The StratoMod study demonstrated that different variant calling pipelines show substantially different performance characteristics across various genomic contexts [15]. For instance, Illumina excels in low-complexity regions like homopolymers, while Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) shows higher performance in segmental duplications and hard-to-map regions [15]. These contextual performance variations mean that choice of sequencing platform and analysis pipeline can systematically bias which variants are detected, potentially skewing target discovery efforts toward or away from certain genomic regions [15].

In cancer research, where tumor heterogeneity presents additional challenges, variant calling errors can lead to mischaracterization of tumor evolution and drug resistance mechanisms [12] [13]. In pharmacogenomics, errors in identifying genetic variations that affect drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion can compromise personalized dosing strategies [12]. The cumulative impact of these errors extends beyond scientific missteps to significant financial costs, as misguided clinical trials based on inaccurate genetic information can waste millions of dollars and delay life-saving treatments [12].

Figure 1: Impact of variant calling on drug discovery pipeline. Errors introduce failures (red) while best practices improve outcomes (green).

Comparative Analysis of Variant Calling Approaches

Traditional vs. AI-Enhanced Variant Calling Methods

Variant calling methodologies have evolved significantly from early statistical approaches to modern artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced methods [16]. Traditional variant callers typically employ rule-based algorithms that apply predetermined thresholds and statistical models to identify genetic variants [16]. While these methods have served as the foundation of genomic analysis for years, they often struggle with complex genomic regions, repetitive sequences, and challenging variant types [16].

AI-enhanced approaches, particularly those utilizing deep learning (DL), represent a paradigm shift in variant calling [16]. These methods leverage convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained on large-scale genomic datasets to identify subtle patterns that distinguish true variants from sequencing artifacts [16]. Unlike traditional methods that require manual parameter tuning and filtering, DL-based callers can automatically produce filtered variants, eliminating the need for post-calling refinement in many cases [16]. This automation not only improves accuracy but also reduces the bioinformatics expertise required for reliable variant detection [16].

The performance advantage of AI-enhanced methods is particularly evident in challenging genomic contexts. DeepVariant, for example, analyzes pileup image tensors of aligned reads, effectively transforming the variant calling problem into an image recognition task [16]. This approach has demonstrated superior accuracy compared to traditional methods including SAMTools, Strelka, GATK, and FreeBayes [16]. Similarly, Clair3 employs deep learning to achieve better performance, especially at lower coverages traditionally more prone to errors [16]. These advancements are crucial for drug discovery applications where comprehensive and accurate variant detection is essential for target identification.

Benchmarking Performance Across Platforms and Methodologies

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies provide quantitative evidence of variant caller performance across different sequencing technologies and genomic contexts. A systematic evaluation of state-of-the-art variant calling pipelines tested 45 different combinations of read alignment and variant calling tools on 14 gold standard samples from the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium [17]. The results revealed "surprisingly large differences in the performance of cutting-edge tools even in high confidence regions of the coding genome," highlighting the critical importance of tool selection [17]. In this extensive benchmark, DeepVariant "consistently showed the best performance and the highest robustness," while other actively developed tools including Clair3, Octopus, and Strelka2 also performed well but with greater dependence on input data quality and type [17].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected Variant Calling Tools

| Variant Caller | Technology Base | SNV Accuracy | Indel Accuracy | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant [16] [17] | Deep Learning (CNN) | >99% [18] | >96% [18] | High accuracy, robust across regions | High computational cost [16] |

| DNAscope [16] [19] | Machine Learning | >99% [18] | >96% [18] | Computational efficiency, no manual filtering | ML-based rather than deep learning [16] |

| GATK [17] | Statistical model | Varies by version | Varies by version | Well-established, extensive documentation | Requires complex filtering [13] |

| Clair3 [17] [20] | Deep Learning | High [20] | High [20] | Fast, excellent at lower coverages | Performance varies by data type [17] |

| Strelka2 [17] | Statistical model | High | High | Good performance | Less robust than DL methods [17] |

The transition from traditional to AI-enhanced variant calling methods shows clear performance benefits. A 2025 study focusing on bacterial genomics demonstrated that deep learning-based variant callers, particularly Clair3 and DeepVariant, "significantly outperform traditional methods and even exceed the accuracy of Illumina sequencing" when applied to Oxford Nanopore Technologies' super-high accuracy model [20]. This superior performance was attributed to the ability of these methods to overcome Illumina's errors, which often arise from difficulties in aligning reads in repetitive and variant-dense genomic regions [20].

For drug discovery applications, the choice between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies also significantly impacts variant calling accuracy. Short-read technologies like Illumina excel in SNV detection and offer cost-effective sequencing, while long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore provide advantages for structural variant detection and resolving complex genomic regions [11] [13]. The emerging approach of hybrid analysis, which combines short-read and long-read data from the same sample, demonstrates promising improvements in variant calling accuracy [19]. The DNAscope Hybrid pipeline, for instance, "significantly improves SNP and Indel calling accuracy, particularly in complex genomic regions," and at lower long-read depths (5x-10x) can outperform standalone short- or long-read pipelines at full sequencing depths (30x-35x) [19].

Table 2: Sequencing Strategy Impact on Variant Calling

| Sequencing Strategy | Target Space | Read Length | SNV/Indel Detection | Structural Variant Detection | Best Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing [14] | ~3200 Mbp | Varies | Excellent | Excellent | Comprehensive variant discovery, novel target identification |

| Whole Exome Sequencing [14] [18] | ~50 Mbp | Short | Excellent | Limited | Coding region focus, cost-effective target screening |

| Targeted Panels [14] | ~0.5 Mbp | Short | Outstanding for low-frequency variants | Limited | Specific gene families, clinical validation |

| Long-Read Sequencing [11] | Full genome | 10,000-30,000 bp | Good | Outstanding | Complex regions, structural variation, repetitive elements |

| Hybrid Approach [19] | Full genome | Combined | Excellent | Excellent | Comprehensive discovery where accuracy is critical |

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Variant Detection

Best Practices in Sample Preparation and Sequencing

The foundation of accurate variant calling begins long before computational analysis, with proper sample preparation and sequencing strategies significantly influencing downstream results [13]. Sample quality deserves particular attention, as degraded or damaged DNA—commonly encountered with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples—can introduce artifacts that complicate variant calling and make it difficult to distinguish between true and damage-induced low-frequency mutations [13]. The use of repair enzymes can help mitigate these issues by removing a broad range of damage, thereby increasing confidence in variant calls [13].

Sequencing strategy selection represents another critical decision point. As shown in Table 2, different approaches offer distinct advantages for various applications in drug discovery [14]. Whole genome sequencing provides the most comprehensive variant detection but at higher cost, while targeted panels offer cost-effective focused analysis with superior sensitivity for low-frequency variants due to higher sequencing depths [14] [13]. The choice between short-read and long-read technologies should align with research objectives, with long-read sequencing particularly valuable for regions inaccessible to short reads [11] [13].

Experimental design should also account for specific variant types of interest. For somatic variant detection in cancer studies, sequencing multiple samples from the same individual increases specificity, helping distinguish true somatic variants from artifacts [13]. Similarly, for familial disorders, trio sequencing (child and both parents) enhances accuracy by providing genetic context [16]. Each of these considerations must be balanced against practical constraints including cost, sample availability, and downstream analysis capabilities.

Bioinformatics Pipelines and Quality Control

Implementing robust bioinformatics pipelines is essential for accurate variant calling, with several critical steps required before variant detection itself [14]. The process typically begins with read alignment using tools such as BWA-MEM, Bowtie2, or minimap2, which map raw sequencing reads to a reference genome [14]. During this stage, prioritizing sensitivity over specificity ensures potential variants are not overlooked initially [13]. Following alignment, identifying and marking PCR duplicates—redundant reads originating from the same nucleic acid molecule—helps prevent overcounting of amplification artifacts [14]. Tools like Picard Tools or Sambamba are commonly used for this purpose [14].

Quality control represents a crucial but sometimes overlooked component of the variant calling pipeline [14]. Routine QC of analysis-ready BAM files should evaluate key sequencing metrics, verify sufficient sequencing coverage was achieved, and check for sample contamination [14]. For family studies and paired samples, expected relationships should be confirmed using tools like the KING algorithm [14]. Additional processing steps such as base quality score recalibration (BQSR) and local realignment around indels may be implemented, though evaluations suggest these provide marginal improvements for their computational cost [14].

The selection of appropriate benchmarking resources enables objective evaluation of variant calling performance [14] [18]. The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium provides gold standard datasets with high-confidence variant calls for several well-characterized genomes, allowing researchers to compare their results against established benchmarks [14] [18]. These resources facilitate the calculation of standard performance metrics including precision, recall, and F1 scores, providing quantitative measures of variant calling accuracy [18]. For clinical applications, the Association for Molecular Pathology recommends using representative variants in bioinformatics guidelines, which must satisfy regulatory requirements for submissions [15].

Figure 2: Optimal variant calling workflow. Critical pre-calling considerations in yellow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Variant Calling

| Resource | Function | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Materials [14] [18] | Gold standard genomes for benchmarking | Validating variant calling pipeline performance |

| Agilent SureSelect Kits [18] | Exome capture and library preparation | Target enrichment for coding region focus |

| FFPE DNA Repair Mix [13] | DNA damage reversal in archived samples | Enabling variant calling from clinical specimens |

| Patient-Derived Organoids [12] | Disease modeling using human cells | Studying genetic heterogeneity and drug response |

| Corning Organoid Culture Products [12] | Specialized surfaces and media | Maintaining genetically stable disease models |

The critical importance of variant calling accuracy in drug target discovery cannot be overstated. As this comparison guide has demonstrated, errors in variant detection can fundamentally misdirect research efforts, leading to missed therapeutic opportunities and costly failed clinical trials. The emergence of AI-enhanced variant calling methods represents a significant advancement over traditional approaches, with tools like DeepVariant, DNAscope, and Clair3 consistently demonstrating superior performance in benchmarking studies [18] [16] [17].

Successful implementation of variant calling in drug discovery requires attention to the entire workflow—from sample preparation through computational analysis. The choice of sequencing strategy should align with research objectives, with hybrid approaches offering particular promise for comprehensive variant detection [19]. As the field advances, the development of more diverse gold standard genomes and improved benchmarking in challenging genomic regions will further enhance variant calling accuracy [17].

For researchers and drug development professionals, investing in optimal variant calling practices is not merely a technical consideration but a fundamental requirement for success. By adopting the best practices, tools, and validation frameworks outlined in this guide, the drug discovery community can significantly improve the reliability of target identification and validation, ultimately accelerating the development of more effective, personalized therapies.

In chemogenomic screens, where researchers systematically study the interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, the accurate detection of genetic variants through Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is paramount. These screens rely on identifying true compound-induced genetic changes amidst technical noise to understand drug mechanisms, identify resistance markers, and discover new therapeutic targets. The reliability of these findings, however, is continually challenged by three persistent technical pitfalls: PCR-derived artifacts, alignment ambiguities, and the inherent difficulties in detecting low-frequency variants. These challenges are particularly pronounced in clinical sequencing contexts, where false positives can lead to incorrect therapeutic decisions, and false negatives can miss biologically significant mutations present in subpopulations of cells [14]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various experimental and computational approaches for mitigating these challenges, providing researchers with data-driven insights to optimize their variant calling accuracy in chemogenomic research.

PCR Artifacts: Origins and Mitigation Strategies

PCR artifacts introduced during library preparation represent a major source of false-positive variant calls. These errors are not merely stochastic but can arise from specific, identifiable mechanisms. One significant source is the oxidation of DNA during fragmentation, particularly during acoustic shearing. This process can generate 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) lesions, which subsequently cause C>A/G>T transversion artifacts during sequencing. These artifacts are characterized by their presence at low allelic fractions, specific strand orientation (G>T errors in the first Illumina read, C>A in the second), and occurrence in both tumor and normal samples, indicating a non-biological origin [21]. Another source involves the generation of chimeric reads during library fragmentation. Studies comparing ultrasonic and enzymatic fragmentation have revealed that sonication can create artifacts containing inverted repeat sequences (IVSs), while enzymatic fragmentation tends to produce artifacts centered on palindromic sequences (PS) with mismatched bases. These chimeric molecules are formed through a mechanism termed the PDSM model (pairing of partial single strands derived from a similar molecule), where sheared DNA fragments incorrectly reanneal [22].

Experimental Protocols for Artifact Reduction

Antioxidant Supplementation Protocol: To mitigate oxidation artifacts during DNA shearing, researchers can introduce antioxidant agents to the DNA sample before acoustic shearing. The following protocol, adapted from Costello et al., has proven effective [21]:

- Perform a solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) bead cleanup (e.g., using Ampure XP beads) on genomic DNA to remove contaminants from extraction.

- Elute the DNA in 50 µL of an antioxidant-supplemented buffer. Tested conditions include:

- Condition A: 10 mM Tris-HCl + 1 mM EDTA

- Condition B: 10 mM Tris-HCl + 100 µM Deferoxamine Mesylate (DFAM)

- Condition C: 10 mM Tris-HCl + 100 µM Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT)

- Condition D: A combination of all three antioxidants.

- Proceed with standard Covaris shearing and subsequent library preparation steps. ELISA-based quantification of 8-oxoG levels can confirm reduction of oxidative damage.

Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) Integration Workflow: UMIs are short random nucleotide sequences ligated to DNA fragments before any PCR amplification steps. This allows bioinformatic consensus generation to distinguish true original molecules from PCR errors [23]. A typical UMI workflow using the fgbio toolkit involves:

- Annotate Bam with Umis: Tag reads in a BAM file with their UMI sequences.

- Group Reads by UMI: Cluster reads that share both a UMI and mapping coordinates into "UMI families."

- Create Consensus Reads: Generate a single, high-quality consensus sequence for each UMI family. Variants not present in the consensus of a family are considered PCR errors and filtered out. Table 1: Comparison of Antioxidant Efficacy in Reducing Oxidation Artifacts (Based on Costello et al. [21])

| Antioxidant Condition | Relative Reduction in C>A Artifacts | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 mM EDTA | Moderate | Chelates metal ions that catalyze oxidation. |

| 100 µM DFAM | High | Potent iron chelator, highly effective. |

| 100 µM BHT | Moderate | Lipid-soluble antioxidant. |

| Combination (All three) | Highest | Synergistic effect, most comprehensive protection. |

Performance Comparison of UMI-Aware Variant Callers

The use of UMIs necessitates specialized variant callers. A 2024 benchmark study compared six variant callers on ctDNA data, including two UMI-aware callers [23]. Table 2: Benchmarking of Variant Callers on Low-Frequency Variants (Synthetic Data) [23]

| Variant Caller | Type | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMI-VarCal | UMI-aware | High | Highest | Detected the fewest putative false positives in UMI data. |

| Mutect2 | Standard | Highest | Medium (Low without UMIs) | Balanced sensitivity/specificity with UMIs; high false positives without. |

| LoFreq | Standard | High | Medium | Effective for low-frequency calls but susceptible to PCR artifacts. |

| bcftools | Standard | Medium | High | Conservative caller, may miss true low-frequency variants. |

| FreeBayes | Standard | Medium | Medium | Balanced performance but outperformed by UMI-aware methods. |

The data indicates that while standard callers like Mutect2 can achieve high sensitivity, they tend to generate more privately called variants—a potential indicator of false positives—in data without UMIs. The integration of UMIs with UMI-aware callers like UMI-VarCal provides a superior balance for distinguishing true low-frequency variants from PCR artifacts [23].

Diagram 1: UMI Workflow for PCR Error Correction. This diagram illustrates the process of using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to tag original DNA molecules before PCR. Bioinformatic grouping into UMI families allows the generation of a consensus sequence, which effectively filters out stochastic PCR errors that are not present in the majority of reads within a family.

Alignment Ambiguity: Impact on Variant Calling Fidelity

Challenges in Spliced Alignment for RNA Sequencing

Variant calling from RNA-seq data presents unique alignment challenges not encountered in DNA-seq. The primary issue stems from the presence of introns in pre-mRNA, which results in sequencing reads that are "spliced" when aligned to a reference genome. These spliced alignments contain large gaps (represented by 'N' in the CIGAR string of the BAM file), which disrupt the contiguous read pileups that DNA-based variant callers are designed to analyze [24]. This misalignment between data structure and tool expectation leads to two major problems: reduced sensitivity (false negatives) and compromised precision (false positives), particularly for variants near exon-intron boundaries.

Optimized Protocol for lrRNA-Seq Variant Calling

A 2023 study demonstrated that transforming alignment files is critical for achieving high performance with DNA-based variant callers on long-read RNA sequencing (lrRNA-seq) data. The recommended pipeline for tools like DeepVariant is as follows [24]:

- SplitNCigarReads (SNCR): Use the GATK function to split reads at intron gaps (N in CIGAR). This converts a single long read spanning multiple exons into several shorter, contiguous alignment segments.

- flagCorrection: A critical, often overlooked step. The SNCR tool assigns the "primary alignment" flag to only one segment from a split read, marking others as "supplementary." The custom

flagCorrectiontool resets all fragments from the original read to be primary alignments, preventing their accidental filtration by downstream tools. - Variant Calling with DeepVariant: Process the transformed BAM file with DeepVariant, which uses a deep learning model to call variants from the now-contiguous read pileups.

Performance benchmarks on PacBio Iso-Seq data from Jurkat and WTC-11 cell lines showed that this combined SNCR + flagCorrection + DeepVariant pipeline significantly outperformed using DeepVariant on unmodified BAMs or with SNCR alone, especially in regions with low-to-moderate read coverage (≤ 40x) and a high proportion of intron-containing reads [24].

The Low-Allele-Frequency Challenge: Distinguishing Signal from Noise

The Fundamental Detection Limit Problem

The reliable detection of mutations present at very low frequencies is crucial for chemogenomics, where it can reveal rare resistant subclones or the early effects of a compound. The core challenge is that the expected frequency of true biological variants (e.g., ~10⁻⁸ to 10⁻⁵ mutations per nucleotide for independent events) falls far below the background error rate of standard Illumina sequencing (~5 × 10⁻³ per nucleotide) [25]. Without specialized methods, even variants with a Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) of 0.5% - 1% are often spurious. Factors that can push a true variant above this noise floor include DNA damage hyperhotspots, clonal expansion of a mutant cell, or analyzing very small biopsies [25].

Advanced Methods for Ultra-Sensitive Detection

To breach this barrier, several sophisticated sequencing methods have been developed, primarily relying on consensus strategies. These can be categorized based on how they use the original template strand information [25]:

- Single-Strand Consensus Sequencing (SSCS): Methods like Safe-SeqS and SiMSen-Seq use UMIs to group reads derived from the same original single DNA strand. Errors are reduced by requiring a consensus within these groups.

- Duplex Sequencing (DS): Ultrasensitive methods like DuplexSeq, SaferSeq, and NanoSeq tag and sequence both strands of the original DNA duplex independently. A true variant is only called if it is found in the consensus sequences derived from both complementary strands. This approach can push the error rate down to ~10⁻⁹ per nucleotide, as it corrects for errors arising from DNA damage on a single strand [25].

SPIDER-seq Protocol for PCR-based Libraries: A novel method called SPIDER-seq (2025) addresses the challenge of applying UMIs to general PCR-based libraries, where UMI sequences are overwritten in subsequent cycles. Its protocol is [26]:

- Amplification with UID-Primers: Perform multiple cycles (e.g., 6 cycles) of PCR using primers containing random Unique Identifiers (UIDs).

- Peer-to-Peer Network Clustering: Bioinformatically cluster all daughter molecules derived from a single original strand by constructing a network based on shared UIDs between parental and daughter strands. This creates a Cluster Identifier (CID).

- CID-Based Consensus Generation: Generate a high-fidelity consensus sequence for each CID, effectively correcting for sequencing and late-cycle PCR errors.

SPIDER-seq has demonstrated the ability to detect mutations at frequencies as low as 0.125% from amplicon libraries, offering a more cost-effective and rapid alternative to hybridization-capture-based UMI methods for applications like monitoring a defined set of mutations [26].

Informatics-Based Filtering for Low-VAF Variants

In the absence of wet-lab consensus methods, robust bioinformatic filtering is essential. Key strategies include:

- Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Cutoffs: Empirical data from clinical exome sequencing suggests that setting a VAF cutoff at approximately 0.30 (30%) can filter out a significant portion (∼82%) of technical artifacts while retaining all medically relevant heterozygous variants, which are expected at VAFs between 0.33 and 0.63 [27]. For somatic cancer variants or mosaic germline variants, lower, validated cutoffs must be established.

- Artifact Blacklisting: Tools like

ArtifactsFindercan systematically scan a BED target region to identify locations prone to artifacts from inverted repeats (IVSs) or palindromic sequences (PSs), generating a custom "blacklist" to filter false positives [22]. - Orientation Filtering: For oxidation artifacts, a strong indicator is a strand bias where G>T errors are found exclusively in read 1 and C>A errors in read 2. Filtering variants that display this pattern can effectively remove these artifacts [21].

Table 3: Comparison of Ultrasensitive Variant Detection Methods [25]

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Principle | Reported Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Strand Consensus | Safe-SeqS, SiMSen-Seq | Consensus from multiple reads of one original strand. | VAF ~10⁻⁵ | Good error reduction; simpler than duplex. | Cannot correct for single-strand DNA damage. |

| Duplex Sequencing | DuplexSeq, SaferSeq | Independent consensus from both strands of DNA duplex. | MF <10⁻⁹ per nt | Highest accuracy; corrects for strand damage. | More complex; lower library yield. |

| Amplicon with UID Overwriting | SPIDER-seq | Network clustering of PCR reads with overwritten UIDs. | VAF ~0.125% | Cost-effective; fast; suitable for amplicons. | New method; requires specialized pipeline. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Variant Calling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants (EDTA, DFAM, BHT) | Mitrate oxidative DNA damage during acoustic shearing. | Reduction of C>A/G>T transversion artifacts [21]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcoding of original DNA molecules before amplification. | Tagging and tracking molecules to generate consensus sequences and remove PCR errors [23]. |

| Enzymatic Fragmentation Mix | Alternative to sonication for DNA shearing; minimal DNA loss. | Library prep from low-input samples; requires awareness of palindromic sequence artifacts [22]. |

| ArtifactsFinder | Bioinformatic algorithm to identify artifact-prone genomic sites. | Generation of a custom "blacklist" for filtering false positives from fragmentation artifacts [22]. |

| SPIDER-seq Pipeline | Computational tool for clustering reads and generating CIDs. | Enables ultra-sensitive variant calling from standard PCR amplicons [26]. |

| FlagCorrection Tool | Corrects alignment flags after splitting spliced RNA-seq reads. | Critical pre-processing step for accurate variant calling from lrRNA-seq data using DNA-based callers [24]. |

Diagram 2: Integrated Strategy for Overcoming NGS Pitfalls. This diagram outlines the multi-faceted approach required for accurate variant calling, combining wet-lab experimental techniques, alignment file pre-processing, and rigorous bioinformatic filtering to address the intertwined challenges of PCR artifacts, alignment ambiguity, and low-frequency variants.

Navigating the pitfalls of PCR artifacts, alignment ambiguity, and low-frequency variants requires an integrated strategy combining rigorous wet-lab protocols with sophisticated bioinformatic tools. The experimental data and comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that no single tool or method is universally superior; rather, the choice depends on the specific application, sample type, and available resources. For instance, while Duplex Sequencing offers the highest theoretical accuracy, SPIDER-seq provides a powerful and more accessible alternative for amplicon-based screens. Critically, the baseline performance of any variant calling pipeline must be established using validated reference standards with known, spiked-in variants to quantify sensitivity and specificity accurately [28]. For chemogenomic screens, where the accurate identification of genetic variants directly impacts the interpretation of compound mechanism and efficacy, adopting these best practices is not merely an optimization but a necessity for generating reliable and actionable data.

Building Robust Pipelines: Best Practices and Tool Selection for Chemogenomic Data

In the field of chemogenomics, where understanding the genetic basis of drug response is paramount, the accuracy of next-generation sequencing (NGS) variant calling is a critical foundation for reliable research outcomes. The choice of computational tools in the bioinformatics pipeline—specifically the aligner and variant caller—directly impacts the sensitivity and precision of variant discovery, which in turn influences downstream analyses and conclusions. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of two widely used aligners, BWA-MEM and Bowtie2, and three established variant callers—GATK, Samtools (Bcftools), and Freebayes—to help researchers and drug development professionals select the optimal tools for their projects.

Aligner Performance: BWA-MEM vs. Bowtie2

BWA-MEM (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner - Maximal Exact Matches) is designed for aligning sequencing reads of 100 bp and longer. It uses a seed-and-extend approach, employing an affine-gap Smith-Waterman algorithm for extension and implementing heuristics to avoid extending alignments through poorly mapping regions. It is particularly well-suited for handling a wide range of read lengths (up to 1 Mbp) and performs chimeric alignments [29] [30].

Bowtie2 is an ultrafast, memory-efficient tool for aligning sequencing reads. It uses the FM-index for efficient sequence search and typically operates in one of two modes: a fast, end-to-end mode (BT-E2E) ideal for reads expected to align entirely to the reference, or a more sensitive local alignment mode (BT-LOC) that allows for partial alignments of reads, which can be beneficial for reads with adapter sequence or significant polymorphisms [17].

Performance Comparison Data

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics as established in benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of BWA-MEM and Bowtie2

| Feature | BWA-MEM | Bowtie2 | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Accuracy | Consistently high; often a gold standard in benchmarks [17] | Lower F1 scores in some benchmarks; BT-LOC mode can be more sensitive than BT-E2E [17] | Evaluation using GIAB gold standard samples for variant discovery in coding sequences [17] |

| Alignment Speed | Faster (e.g., ~1042 sec for 2GB FASTQ) [31] | Slower (e.g., ~5132 sec for same dataset) [31] | Empirical test with paired-end FASTQ files [31] |

| Alignment Specificity | High; can be optimized for multi-species samples by increasing seed length [30] | Information not available in search results | Analysis of host-pathogen (e.g., Plasmodium-human) data; default seed length is 19nt [30] |

| Recommended Use Case | General-purpose alignment for WGS and WES; preferred for medical variant calling [17] | Not recommended for medical variant calling in one benchmark; may be suitable for other sequencing applications [17] | Benchmark of state-of-the-art variant calling pipelines [17] |

Variant Caller Performance: GATK, Samtools/Bcftools, and Freebayes

GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) HaplotypeCaller is a widely adopted, complex tool that operates by reassembling reads in regions of potential variation. It uses a pair-hidden Markov model for local reassembly of haplotypes and a powerful Markov model-based genotyping algorithm to calculate genotype likelihoods. Its Best Practices pipeline includes additional steps like base quality score recalibration (BQSR) and variant quality score recalibration (VQSR) to refine results [32] [17].

Samtools/Bcftools is a pipeline that relies on the mpileup command to summarize read alignments and compute genotype likelihoods at each genomic position. The bcftools call command then performs the actual variant calling. It is known for its speed and efficiency and can be run in both single-sample and multiple-sample (joint-calling) modes [32].

Freebayes is a Bayesian genetic variant caller that detects polymorphisms—SNPs, indels, mnps, and complex events—by counting the observed alleles and assigning a probability based on their frequency in the population of aligned reads. It is a straightforward method that assumes diploidy but does not rely on complex machine learning models [32].

Performance Comparison Data

The table below summarizes the performance of these callers based on recent benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GATK, Bcftools, and Freebayes

| Variant Caller | SNP F1 Score (Example) | Indel F1 Score (Example) | Key Strengths & Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| GATK HaplotypeCaller | High (e.g., >99% concordance with truth sets) [33] | High | Strengths: Highly polished, extensive best practices, good overall accuracy. Weaknesses: Can be computationally slow, complex to set up [33]. |

| Bcftools | High sensitivity, especially in multiple-sample mode [32] | Information not available in search results | Strengths: Very fast, high specificity, efficient for large projects. Weaknesses: May have lower sensitivity in single-sample mode at low coverage [32]. |

| Freebayes | Lower number of detected variants in some comparisons [32] | Information not available in search results | Strengths: Simple, model-free approach. Weaknesses: May have lower sensitivity and specificity compared to other methods [32]. |

| DeepVariant | Highest in benchmarks (e.g., >99.9%) [17] | High (e.g., >99.5%) [3] | Strengths: Top-tier accuracy and robustness using deep learning. Weaknesses: Computationally intensive [17]. |

Integrated Workflows and Experimental Protocols

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, benchmarking studies often follow a rigorous protocol based on gold-standard reference materials.

- Reference Datasets: The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium provides well-characterized human genomes (e.g., NA12878/HG001, Ashkenazi Jewish trio HG002-HG004) with high-confidence variant calls that serve as the "truth set" for evaluation [34] [17].

- Data Processing:

- Alignment: Raw FASTQ reads are aligned to a reference genome (GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38) using the aligner with default or optimized parameters [17].

- Post-Alignment Processing: The resulting BAM files are processed to mark duplicate reads (e.g., using GATK MarkDuplicates) and, for some pipelines, to perform Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR) [35] [17].

- Variant Calling: Processed BAM files are used as input for the variant callers.

- Performance Assessment: The generated VCF files are compared against the GIAB truth set using the

hap.pytool. Key metrics include:

Impact of Alignment on Variant Calling

A critical finding from recent research is that while the choice of aligner is important, its impact is often superseded by the choice of the variant caller, provided a robust aligner like BWA-MEM is used. One large-scale study concluded that when considering accurate aligners (excluding Bowtie2, which performed poorly), "the accuracy of variant discovery mostly depended on the variant caller and not the read aligner" [17]. However, the alignment and variant calling steps are not entirely independent. The DRAGEN platform, which uses a highly optimized alignment algorithm, demonstrated systematically higher F1 scores, precision, and recall compared to a GATK with BWA-MEM2 pipeline, underscoring that improvements in the alignment stage can translate to better final variant calls [34].

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for benchmarking aligners and variant callers.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and resources that form the backbone of a reliable NGS variant calling workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for NGS Variant Calling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Samples | Benchmark Dataset | Provides a gold-standard set of genomes with expertly curated variant calls to validate pipeline accuracy [34]. |

| GRCh37/hg38 | Reference Genome | The standard human reference sequences to which reads are aligned for mapping and variant identification. |

| BWA-MEM | Read Aligner | Aligns sequencing reads to the reference genome, a critical first step that influences all downstream analysis [29] [17]. |

| GATK | Variant Calling Toolkit | A comprehensive suite of tools, with HaplotypeCaller being a benchmark for accurate germline variant discovery [17]. |

| DeepVariant | Variant Caller | A deep-learning based caller that has demonstrated top-tier accuracy in independent benchmarks [3] [17]. |

| SAMtools/Bcftools | Utility Suite | A collection of utilities for manipulating alignments and calling variants, prized for its speed and efficiency [32]. |

| hap.py | Benchmarking Tool | The official GA4GH tool for calculating performance metrics like precision and recall against a truth set [17]. |

The choice between BWA-MEM and Bowtie2 is clear-cut for variant calling applications: BWA-MEM is the recommended aligner due to its superior performance in benchmarking studies, higher speed, and status as a de facto gold standard in medical genomics [17]. For variant calling, the landscape is more nuanced. While GATK HaplotypeCaller remains a robust and widely supported option with very high accuracy, newer tools like DeepVariant have demonstrated superior performance in recent, comprehensive benchmarks [17].

For researchers in chemogenomics, where accuracy is non-negotiable, the evidence suggests a pipeline combining BWA-MEM for alignment and DeepVariant for calling would yield the most accurate results. If computational resources or support for DeepVariant are a constraint, the established BWA-MEM and GATK HaplotypeCaller pipeline remains a very strong alternative. Tools like Bcftools are excellent for projects where processing speed is a critical factor, and it has been shown to outperform other callers in specific scenarios, such as low-coverage data or multiple-sample calling modes [32].

In chemogenomic screens, the precise identification of variants is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation upon which all subsequent analyses and therapeutic insights are built. The central challenge in this process lies in the accurate discrimination between somatic mutations, which are acquired and specific to the tumor cells, and germline variants, which are inherited and present in all of a patient's cells. This distinction is critical because somatic mutations can drive cancer progression and dictate response to therapies, whereas germline variants provide the constitutional genetic background of the individual. The failure to properly separate these variant types directly compromises the integrity of chemogenomic data, leading to misinterpretation of drug response biomarkers and potentially flawed therapeutic associations.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have become the standard for variant detection in cancer research, yet each platform presents distinct advantages and limitations for chemogenomic applications. Short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) currently offers higher base-level accuracy and is widely adopted in clinical settings, but struggles with highly homologous genomic regions, including paralogous genes and pseudogenes, which can lead to false positives or negatives [36]. Conversely, emerging long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) excel in resolving complex genomic regions and providing phasing information, making them particularly valuable for pharmacogenes with structural complexity, such as CYP2D6, CYP2B6, and HLA genes [37]. The choice of sequencing technology must align with the specific genomic contexts of the drug targets under investigation in chemogenomic screens.

Fundamental Biological and Technical Distinctions

Biological Origins and Clinical Implications

Somatic and germline variants originate through fundamentally different biological mechanisms and have distinct implications for cancer biology and treatment.

Somatic Variants: These mutations occur in non-germline tissues after conception and are not inherited. In cancer, somatic mutations accumulate due to environmental exposures, replication errors, and defective DNA repair mechanisms. They are present only in tumor cells and their progeny, leading to mosaicism within tissues. From a clinical perspective, somatic mutations in genes such as BRAF, EGFR, and KRAS can serve as direct therapeutic targets or predictive biomarkers for drug response. Identifying these variants helps guide targeted therapies and is essential for calculating clinically relevant metrics like tumor mutational burden (TMB), an important predictor of response to immunotherapy [38].

Germline Variants: These are inherited genetic variations present in virtually every cell from birth. While most are benign polymorphisms, pathogenic germline variants in cancer predisposition genes (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53) confer increased lifetime risk of developing specific malignancies. In chemogenomic contexts, germline variants in pharmacogenes can significantly influence drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity risk. For instance, polymorphisms in genes like CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and DPYD affect the metabolism of numerous chemotherapeutic agents and targeted therapies [37].

The accurate classification of these variant types is not merely an academic exercise but has direct clinical consequences. Misclassification can lead to inappropriate treatment decisions, miscalculated TMB scores, and incorrect assessment of hereditary cancer risk. This is particularly challenging in tumor-only sequencing designs, where the absence of a matched normal sample complicates the discrimination between somatic and germline variants [38].

Technical Challenges in Variant Discrimination

Several technical factors complicate the accurate distinction between somatic and germline variants in sequencing data:

Germline Leakage: This occurs when germline variants are mistakenly identified as somatic mutations due to limitations in variant calling algorithms. The median somatic SNV prediction set contains approximately 4325 calls and leaks about one germline polymorphism, with leakage rates inversely correlated with somatic SNV prediction accuracy [39]. This leakage poses privacy concerns as leaked germline variants could potentially be used for patient re-identification.

Tumor-in-Normal Contamination: The unexpected contamination of normal samples with tumor cells reduces variant detection sensitivity, compromising downstream analyses. This problem is particularly prevalent in haematological malignancies and sarcomas, with highest prevalence observed in saliva samples from acute myeloid leukaemia patients and sorted CD3+ T-cells from myeloproliferative neoplasms [40]. Such contamination can lead to erroneous subtraction of genuine high-allele-frequency somatic variants during variant calling.

Mapping Artifacts in Homologous Regions: Short-read sequencing technologies face significant challenges in highly homologous genomic regions such as pseudogenes or paralogous genes. Genes with high homology (e.g., SMN1, SMN2, CBS, and CORO1A) show consistently low coverage across all read lengths due to nonspecific mapping, potentially leading to false negative results in critical pharmacogenes [36].

Comparative Performance of Variant Calling Approaches

Individual Caller Performance Benchmarking

Comprehensive benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of somatic variant callers, enabling informed selection for chemogenomic applications. A recent evaluation of 20 somatic variant callers across multiple whole-exome sequencing datasets revealed significant differences in accuracy for detecting single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels) [41].

Table 1: Performance of Leading Somatic Variant Callers

| Variant Caller | SNV F1 Score | Indel F1 Score | Notable Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragen | 0.895 (Highest for SNVs) | - | Commercial solution with optimized performance |

| Mutect2 | ~0.89 | ~0.837 | Widely adopted, balanced SNV/indel performance |

| Muse | ~0.88 | - | High SNV accuracy |

| NeuSomatic | - | 0.837 (Highest for indels) | Deep learning approach |

| TNScope | ~0.87 | - | Commercial solution |

| Strelka | ~0.86 | ~0.82 | Robust open-source option |

| VarScan2 | ~0.80 | ~0.81 | Established method |

The benchmarking study identified five high-performing individual somatic variant callers: Muse, Mutect2, Dragen, TNScope, and NeuSomatic [41]. Performance varied significantly across different reference datasets, highlighting the importance of evaluating callers on datasets representative of specific research contexts. For chemogenomic applications focused on specific pharmacogenes, additional validation in genomic regions relevant to drug metabolism and response is recommended.

Ensemble Approaches for Enhanced Accuracy

Ensemble methods that combine multiple variant callers have demonstrated superior performance compared to individual callers, achieving significantly higher F1 scores for both SNVs and indels [41].

Table 2: High-Performing Ensemble Combinations

| Variant Type | Ensemble Composition | Performance (F1 Score) | Improvement Over Best Single Caller |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs | LoFreq, Muse, Mutect2, SomaticSniper, Strelka, Lancet | 0.927 | >3.6% improvement over Dragen |

| Indels | Mutect2, Strelka, Varscan2, Pindel | 0.867 | >3.5% improvement over NeuSomatic |

| Optimal Balanced | Muse, Mutect2, Strelka (SNVs); Mutect2, Strelka, Varscan2 (Indels) | >0.89 (SNVs), >0.85 (Indels) | Cost-effective solution with high accuracy |

The ensemble approach that combined six callers (LoFreq, Muse, Mutect2, SomaticSniper, Strelka, and Lancet) for SNVs achieved a mean F1 score of 0.927, outperforming the top-performing individual caller (Dragen) by more than 3.6% [41]. Similarly, for indels, a four-caller ensemble (Mutect2, Strelka, Varscan2, and Pindel) achieved a mean F1 score of 0.867, representing a 3.5% improvement over the best individual indel caller (NeuSomatic) [41]. These ensemble methods effectively leverage the complementary strengths of individual callers, mitigating their respective limitations.

Tumor-Only Calling and Machine Learning Advances

In clinical settings where matched normal samples are unavailable, tumor-only variant calling presents significant challenges, primarily due to difficulty distinguishing rare germline variants from true somatic mutations. Traditional approaches that rely on filtering against germline databases (e.g., dbSNP, gnomAD) exhibit substantial false positive rates, particularly for patients from populations underrepresented in these databases [38].

Recent machine learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable improvements in tumor-only variant calling. Studies applying TabNet, XGBoost, and LightGBM to classify variants as somatic or germline using features derived exclusively from tumor-only data achieved area under the curve (AUC) values exceeding 94% on TCGA datasets and 85% on metastatic melanoma datasets [38]. These models utilized 30 mutation- and copy-number-specific features, including:

- Traditional features: germline database frequency, COSMIC somatic mutation database counts, variant allele fraction (VAF)

- Sequence context features: trinucleotide context and base substitution subtypes

- Local copy number features: derived from copy-number segmentation data

Notably, these machine learning approaches successfully eliminated the significant racial bias observed in traditional tumor-only variant calling methods, where TMB estimates for Black patients were extremely inflated relative to those of white patients due to underrepresented germline variants in reference databases [38].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Variant Detection

Standardized Sequencing and Analysis Workflow

Implementing a robust, reproducible variant calling pipeline requires strict adherence to standardized protocols across sample processing, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis. The following workflow represents best practices derived from comprehensive benchmarking studies:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Utilize matched tumor-normal pairs when possible, with normal tissue derived from blood, saliva, or skin biopsy

- Implement rigorous quality control measures using tools like omnomicsQ to flag samples falling below predefined thresholds [42]

- For WES, ensure minimum coverage of 100× for tumor samples and 75× for normal samples to confidently detect variants with VAFs ≥0.15 [43]

- Consider longer read lengths (150-250 bp) to improve mapping accuracy in homologous regions [36]

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Alignment with BWA-MEM against appropriate reference genome (hg19/hg38)

- Post-alignment processing including duplicate marking (sambamba) and base quality score recalibration (GATK BQSR) [41]

- Multi-caller approach using at least 2-3 high-performing callers (e.g., Mutect2, Strelka, VarScan2)

- Ensemble aggregation of calls with threshold-based filtering

- Annotation using tools like ANNOVAR, Ensembl VEP, or SnpEff [42]

Quality Assurance and Validation: