Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening: Analyzing Success Rates and Strategic Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of phenotypic and target-based drug screening strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening: Analyzing Success Rates and Strategic Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of phenotypic and target-based drug screening strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the historical context and foundational principles of both approaches, examining key metrics such as their relative success in producing first-in-class medicines. The content delves into practical methodological applications, addresses common challenges and optimization tactics, and validates findings with recent case studies and success rates. By synthesizing evidence from industry and academia, it offers a strategic framework for selecting and integrating these methodologies to enhance drug discovery productivity and innovation.

Defining the Paradigms: The History and Core Principles of Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening

The landscape of drug discovery has been historically dominated by two fundamental strategies: phenotypic screening and target-based screening. While the late 20th century saw a significant shift toward target-based approaches, recent decades have witnessed a resurgence in phenotypic screening driven by its proven ability to deliver first-in-class therapies. This guide provides an objective comparison of these parallel methodologies, examining their success rates, experimental protocols, and practical applications in modern drug discovery pipelines. As of 2025, the field has evolved toward integrated workflows that combine the strengths of both approaches, leveraging advances in artificial intelligence, automation, and functional genomics to overcome their respective limitations.

Historical Context and Success Rates

Phenotypic screening, which identifies compounds based on measurable changes in biological function without prior knowledge of the molecular target, predates target-based approaches. Its resurgence follows compelling data on its productivity. Between 1999 and 2008, phenotypic screening was responsible for 28 first-in-class small molecule drugs, compared to 17 from target-based methods [1]. From 2012 to 2022, the application of phenotypic screening in major pharmaceutical companies grew from less than 10% to an estimated 25-40% of project portfolios [1].

Table 1: Comparative Success Rates of Discovery Approaches (1999-2017)

| Discovery Strategy | Number of Approved Drugs |

|---|---|

| Phenotypic Screening | 58 |

| Target-Based Screening | 44 |

| Monoclonal Antibody Therapies | 29 |

Data sources: Swinney and Anthony (2011); Haasen, et al. (2017) as cited in [1].

This renewed adoption stems from phenotypic screening's ability to address complex biological systems and identify novel mechanisms of action, particularly for diseases with multifactorial pathogenesis or poorly understood underlying biology.

Direct Comparison: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

Table 2: Fundamental Characteristics and Comparative Output

| Parameter | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Approach | Measures biological effects without requiring known molecular mechanism [2] | Focuses on modulation of predefined molecular targets [2] |

| Key Strength | Identifies novel targets and mechanisms; captures biological complexity [2] [1] | Enables rational drug design; streamlined optimization [2] |

| Primary Limitation | Target deconvolution challenging; potentially longer discovery timelines [2] [3] | Limited to known biology; may miss complex network effects [2] |

| First-in-Class Success | Higher rate of first-in-class drug discovery [1] | Fewer first-in-class discoveries [1] |

| Therapeutic Area Strengths | Oncology, anti-fibrotics, rare diseases with unknown targets [1] [4] | Well-characterized pathways with validated targets [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Phenotypic Screening Workflows

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated experimental designs that incorporate multiple readouts and model systems:

1. High-Content Cellular Screening Recent advances in high-content screening (HCS) combine automated imaging with machine learning-based image analysis to extract multiparametric data from cell-based assays. The workflow typically involves:

- Culturing disease-relevant cell types (primary cells or engineered lines) in multi-well plates

- Compound library addition using automated liquid handling systems

- Incubation for predetermined time periods (hours to days)

- Multiplexed staining with fluorescent dyes or antibodies

- Automated high-throughput microscopy image acquisition

- ML/AI-powered image analysis for phenotypic profiling [1]

2. Complex Model Systems To enhance physiological relevance, researchers are increasingly implementing:

- 3D Cell Cultures and Organoids: The MO:BOT platform automates seeding, media exchange, and quality control for organoids, providing more physiologically relevant data while improving reproducibility [5].

- CRISPR-Enhanced Screening: Genome-wide CRISPR screening combined with organoid models enables systematic investigation of gene-function relationships in biologically relevant contexts [6].

Target Deconvolution Methods

A critical step following phenotypic hit identification is target deconvolution—determining the precise molecular mechanism of action. Commonly employed methods include:

1. Affinity Chromatography

- Involves immobilizing small molecule tool compounds on solid supports

- Often requires compound labeling or modification that may affect binding properties

- Followed by mass spectrometry-based identification of binding partners [3]

2. Activity-Based Protein Profiling

- Uses specialized small molecule probes containing three parts: covalent modifier, linker, and tag for separation

- Targets specific protein classes (e.g., enzymes with active site nucleophiles)

- Enables profiling of enzyme activities in complex proteomes [3]

3. Label-Free Techniques

- Include methods like cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) that detect drug-target engagement without compound modification

- Measure changes in protein thermal stability upon ligand binding

- Provide direct evidence of target engagement in physiologically relevant environments [7]

4. Genetic Approaches

- CRISPR-based screening identifies genes whose modulation mimics or rescues compound-induced phenotypes

- Expression cloning techniques that increase target expression to facilitate identification [3] [6]

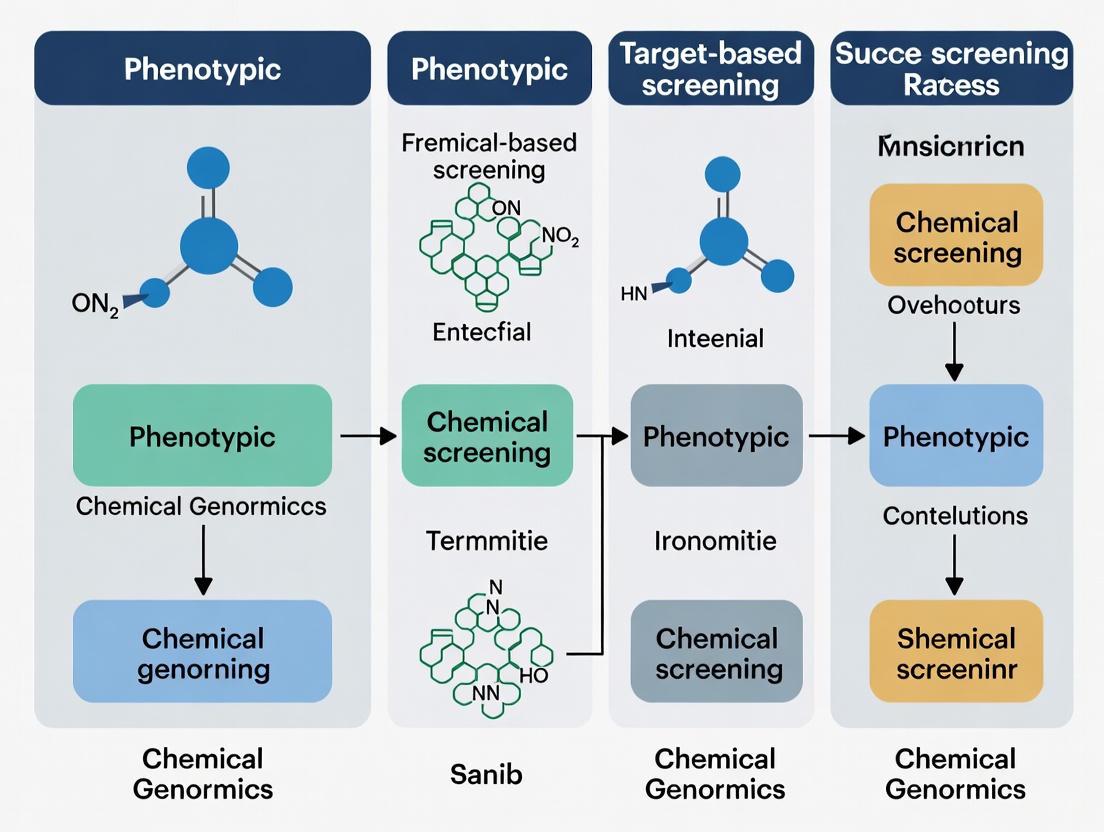

Figure 1: Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution Workflow. Following hit identification from phenotypic assays, multiple parallel approaches are employed to determine the molecular target.

Recent Therapeutic Successes from Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening has yielded multiple recently approved therapies addressing previously untreatable or poorly managed conditions:

Vamorolone (AGAMREE), approved in 2023 for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, was identified through phenotypic profiling that elucidated its unique "dissociative" steroid activity, separating efficacy from typical steroid safety concerns [1].

Risdiplam (Evrysdi), approved in 2020 for spinal muscular atrophy, modulates SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing. The SMN2 target lacked known activity and would have been unlikely identified through traditional target-based approaches [1].

Daclatasvir (Daklinza), a first-in-class NS5A inhibitor for hepatitis C, targets a viral protein with no enzymatic activity and a poorly understood mechanism—characteristics that made it elusive to target-based methods [1].

Lumacaftor (in ORKAMBI), for cystic fibrosis, was discovered using target-agnostic compound screens in cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants [1].

Integrated Approaches and Technological Advancements

The distinction between phenotypic and target-based screening is increasingly blurred by integrated workflows that combine their strengths:

AI-Powered Predictive Models Tools like DrugReflector use active reinforcement learning to predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes based on transcriptomic signatures. This approach has demonstrated an order of magnitude improvement in hit rates compared to random library screening [8].

CRISPR-Enhanced Screening CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables high-throughput functional genomics that bridges phenotypic and target-based approaches. By systematically perturbing genes and observing phenotypic outcomes, researchers can:

- Identify novel therapeutic targets across various diseases

- Elucidate drug mechanisms of action

- Investigate gene-drug interactions at genome-wide scale [6]

Automated and Human-Relevant Model Systems Advanced automation platforms like the MO:BOT system standardize 3D cell culture, improving reproducibility and reducing the need for animal models. These systems produce consistent, human-derived tissue models that provide more predictive safety and efficacy data [5].

Figure 2: Convergence of Technologies in Modern Drug Discovery. Integrated approaches combine strengths of both phenotypic and target-based screening enhanced by computational and technological advances.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Technologies and Reagents for Modern Screening Approaches

| Technology/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MO:BOT Platform | Automated 3D cell culture; standardizes organoid seeding, feeding, QC | Phenotypic screening with enhanced physiological relevance [5] |

| CETSA | Cellular thermal shift assay; measures target engagement in intact cells | Validation of direct drug-target interactions in physiological environments [7] |

| DrugReflector | AI model predicting compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes | Analysis of transcriptomic signatures; improves phenotypic screening hit rates [8] |

| CRISPR sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide gene perturbation for functional genomics | Identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets [6] |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopy with multiparametric readouts | Phenotypic profiling and morphological analysis [1] |

| ChEMBL Database | Repository of bioactivity data; >20 million data points | Selectivity profiling; tool compound identification [3] |

| eProtein Discovery System | Automated protein expression and purification | Target-based screening; structural biology [5] |

The resurgence of phenotypic screening represents not a rejection of target-based approaches, but an evolution toward more integrated discovery paradigms. While phenotypic screening demonstrates superior performance in generating first-in-class therapies for complex diseases, target-based approaches remain valuable for optimizing compounds against validated targets. The most productive modern pipelines leverage both strategies—using phenotypic screening to identify novel mechanisms and target-based methods for rational optimization—supported by AI, functional genomics, and human-relevant model systems. This synergistic approach addresses the limitations of each method alone, creating a more robust framework for addressing unmet medical needs across diverse therapeutic areas.

The latter part of the 20th century witnessed a fundamental transformation in drug discovery, marked by the rise of target-based screening approaches. This shift was catalyzed by breakthroughs in molecular biology, genomics, and structural biology, which enabled researchers to move away from traditional phenotypic screening—which identifies compounds based on observable changes in cells or organisms without requiring knowledge of the specific molecular target—toward a more precise paradigm focused on well-defined molecular targets [2] [9]. Target-based screening involves identifying compounds that interact with a specific molecular target, often a protein with a established role in the disease process [10]. The strategic dichotomy between these approaches has shaped modern pharmaceutical development, with each offering distinct advantages and limitations for drug discovery professionals.

The molecular biology revolution provided the essential tools for this transition, offering unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms at the molecular level. Advances in recombinant DNA technology, protein purification, high-resolution structural determination methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy, and ultimately the sequencing of the human genome created a foundation for target-based drug discovery [2] [11]. These technologies enabled the identification and validation of specific proteins, receptors, and enzymes as potential therapeutic targets, ushering in an era of rational drug design that promised greater precision, efficiency, and mechanistic understanding compared to traditional phenotypic approaches [10].

Historical Context: From Phenotypic Screening to Targeted Approaches

The Traditional Dominance of Phenotypic Screening

Before the molecular biology revolution, drug discovery relied heavily on phenotypic screening, which contributed to the development of numerous first-in-class therapeutics [1]. This approach identified compounds based on functional biological effects in complex systems without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [9]. Notable successes included antibiotics like penicillin, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants discovered by observing their effects on cells, tissues, or whole organisms [1] [9]. Between 1999 and 2008, phenotypic screening was responsible for 28 first-in-class small molecule drugs compared to 17 from target-based methods [1].

The Molecular Biology Revolution

The period from the 1970s to the early 2000s brought transformative technological advances that enabled the shift to target-based screening. Key developments included recombinant DNA technology (1970s), polymerase chain reaction (1980s), high-throughput sequencing (1990s), and the completion of the Human Genome Project (2003) [2]. These breakthroughs provided researchers with an unprecedented view of disease mechanisms at the molecular level, creating the foundation for target-based approaches by identifying thousands of potential therapeutic targets [12]. The parallel development of high-throughput screening technologies allowed rapid testing of compound libraries against these newly identified targets, further accelerating the adoption of target-based paradigms in pharmaceutical research and development [2].

Fundamental Principles of Target-Based Screening

Conceptual Framework

Target-based screening operates on a fundamentally different principle from phenotypic screening. While phenotypic approaches ask "Does this compound produce a beneficial biological effect?", target-based screening asks "Does this compound modulate my specific molecular target?" [9]. This hypothesis-driven approach begins with the selection and validation of a molecular target—typically a protein, enzyme, receptor, or nucleic acid—with a well-established role in the disease process [2]. The target-based paradigm relies on a deep understanding of disease biology, wherein specific molecular entities are identified as critical drivers of pathology, and therapeutic intervention is designed to modulate their activity in a precise manner [10].

The strategic workflow typically begins with target identification and validation, followed by assay development to measure target engagement or functional modulation, high-throughput screening of compound libraries, hit validation and optimization, and finally preclinical and clinical development [13]. This structured approach allows for systematic optimization of drug candidates based on their interactions with the defined molecular target, leveraging structural biology and computational modeling to refine compound properties [2] [12].

Key Technological Enablers

Several technological advances have been instrumental to the success of target-based screening:

- Structural Biology Tools: X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and NMR spectroscopy provide high-resolution views of target structures, enabling structure-based drug design [2] [11].

- Computational Methods: Molecular docking, virtual screening, and molecular dynamics simulations allow in silico prediction of compound-target interactions [13] [12].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Robotics: Automation systems enable testing of thousands to millions of compounds against targets in miniaturized formats [9].

- Bioinformatics and Omics Technologies: Genomic, proteomic, and chemoproteomic methods facilitate target identification, validation, and selectivity profiling [2] [14].

Figure 1: Target-Based Drug Discovery Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential stages of target-based screening, from initial target identification through to preclinical development.

Comparative Analysis: Success Rates and Strategic Value

Quantitative Assessment of Drug Discovery Outcomes

The debate between phenotypic and target-based screening approaches often centers on their relative success rates in producing new therapeutics. Comprehensive analyses of FDA-approved drugs reveal distinct patterns of success for each approach.

Table 1: Drug Discovery Approaches and Their Success Rates (1999-2017)

| Discovery Strategy | Number of Approved Drugs | First-in-Class Drugs | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic Screening | 58 | 28 (1999-2008) | Identifies novel mechanisms; effective for complex diseases |

| Target-Based Screening | 44 | 17 (1999-2008) | Enables rational optimization; higher specificity |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | 29 | N/A | High specificity; favorable pharmacokinetics |

Data adapted from Ardigen analysis of FDA approvals (1999-2017) [1].

More recent data from 2012 to 2022 shows that the application of phenotypic screening in large pharmaceutical companies has grown to approximately 25-40% of project portfolios, reflecting a balanced approach that leverages the strengths of both strategies [1]. This suggests that while target-based approaches remain important, the drug discovery field has recognized the value of maintaining a diversified strategy.

Strategic Advantages of Target-Based Screening

Target-based screening offers several distinct advantages that have secured its position in modern drug discovery:

- Mechanistic Clarity: From the outset, researchers understand precisely how a compound is intended to work, enabling more informed optimization [10].

- High Specificity: Compounds can be designed or selected for precise interaction with the intended target, reducing off-target effects [10].

- Efficient Optimization: Structure-activity relationships (SAR) can be systematically explored using structural biology and computational modeling [2] [12].

- Personalized Medicine Potential: Targets can be selected based on genetic evidence in specific patient populations, enabling precision medicine approaches [10].

- Higher Throughput Capability: Target-based assays are often more amenable to miniaturization and automation than complex phenotypic systems [9].

The success of target-based screening is exemplified by drugs like imatinib (chronic myelogenous leukemia), trastuzumab (HER2-positive breast cancer), and HIV antiretroviral therapies including reverse transcriptase and integrase inhibitors [10]. These therapies were developed with precise knowledge of their molecular targets, enabling highly specific therapeutic interventions tailored to particular disease mechanisms.

Limitations and Challenges of Target-Based Approaches

Despite its advantages, target-based screening faces several significant challenges:

- Dependence on Target Validation: The approach is only as good as the underlying target hypothesis; incorrect validation leads to clinical failure [15] [10].

- Limited Novelty: The hypothesis-driven nature may limit discovery of truly novel mechanisms outside established biological understanding [9].

- Oversimplification of Biology: Single-target approaches may fail to address complex, multifactorial diseases with redundant pathways [2] [10].

- High Validation Costs: Extensive resources are required to establish robust causal links between targets and diseases [15].

These limitations are particularly evident in complex diseases like Alzheimer's, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, where target-based approaches have struggled despite significant investment [10]. The reductionist nature of targeting single proteins often fails to capture the systems-level complexity of many disease processes.

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Characteristic | Target-Based Screening | Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Bias | Hypothesis-driven; limited to known pathways | Unbiased; allows novel target identification |

| Mechanism of Action | Defined from outset | Often unknown at discovery; requires deconvolution |

| Throughput | Typically high | Variable; often medium throughput |

| Technical Requirements | Structural biology, computational modeling, enzyme assays | High-content imaging, functional genomics, AI analysis |

| Optimal Application | Well-validated targets with clear disease linkage | Complex diseases with poorly understood mechanisms |

Comparison based on characteristics described in Technology Networks analysis [9].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Standard Protocols for Target-Based Screening

Target-based screening employs well-established experimental protocols that have been refined through decades of pharmaceutical research. A representative protocol for high-throughput target-based screening typically includes the following stages:

Phase 1: Target Production and Validation

- Clone, express, and purify the recombinant target protein

- Validate target functionality through biochemical and biophysical assays

- Determine optimal buffer conditions for stability and activity

Phase 2: Assay Development and Optimization

- Develop a robust assay measuring target engagement or functional modulation

- Optimize assay parameters (pH, ionic strength, temperature, incubation time)

- Establish controls and determine Z-factor for assay quality assessment

- Miniaturize and adapt assay to high-throughput format

Phase 3: Primary Screening

- Screen compound library (typically 10,000-1,000,000 compounds)

- Include appropriate controls on each plate (positive, negative, vehicle)

- Collect raw data and normalize to plate controls

- Apply statistical thresholds for hit identification (typically >3σ from mean)

Phase 4: Hit Confirmation and Validation

- Confirm hits in dose-response format

- Exclude promiscuous binders/aggregators through counter-screens

- Assess selectivity against related targets

- Validate binding through orthogonal methods (SPR, ITC, NMR)

This systematic approach ensures identification of high-quality starting points for medicinal chemistry optimization [13].

Advanced Methodologies: Structure-Based Drug Design

Structure-based drug design represents the cutting edge of target-based approaches, leveraging high-resolution structural information to guide compound optimization [12]. Recent advances include:

- AI-Powered Molecular Generation: Models like DiffGui use equivariant diffusion models to generate novel molecules with optimized binding affinity and drug-like properties directly within target binding pockets [12].

- Cryo-EM Applications: Single-particle cryo-electron microscopy enables structure determination of challenging targets like membrane proteins and large complexes [2] [11].

- AlphaFold Integration: Computationally predicted protein structures expand the target space accessible to structure-based approaches [11] [12].

- Free Energy Perturbation: Physics-based calculations provide accurate prediction of binding affinities for compound prioritization.

These methodologies enable increasingly sophisticated target-based discovery, reducing reliance on serendipity and enabling more rational drug design [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementation of target-based screening requires specialized reagents and platforms that have become essential tools in modern drug discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Target-Based Screening

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Curated bioactivity data; drug-target interactions | Target identification; chemogenomic analysis [11] |

| AlphaFold DB | Protein structure prediction | Structure-based design for targets without experimental structures [11] [12] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts ligand binding poses and affinities | Virtual screening; binding mode analysis [13] [12] |

| Cryo-EM Platforms | High-resolution structure determination | Membrane proteins; large complexes [2] [11] |

| SPR/BLI Instruments | Label-free binding kinetics | Hit validation; affinity measurement [14] |

| Thermal Shift Assay Kits | Protein stability measurement | Target engagement; binding confirmation [14] |

| Compound Libraries | Diverse chemical collections | High-throughput screening [2] [13] |

These tools collectively enable the implementation of sophisticated target-based screening campaigns, providing the necessary infrastructure for modern drug discovery.

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

Hybrid Strategies in Modern Drug Discovery

The historical dichotomy between phenotypic and target-based screening is increasingly giving way to integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms [2]. Modern drug discovery often employs:

- Phenotypic Screening for Novel Target Discovery: Using phenotypic approaches to identify new biological mechanisms, followed by target deconvolution to identify the molecular targets [1] [9].

- Target-Based Optimization: Applying target-based approaches to optimize compounds identified through phenotypic screening [2].

- Chemical Biology Integration: Using target-agnostic compound profiling to elucidate mechanisms of action for phenotypic hits [15] [14].

These hybrid workflows create a virtuous cycle where phenotypic screening identifies novel biology and target-based approaches enable precise optimization of therapeutic candidates [2].

Figure 2: Integrated Drug Discovery Strategy. This diagram illustrates how modern drug discovery combines phenotypic and target-based approaches, leveraging the strengths of both paradigms.

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The future of target-based screening will be shaped by several emerging technologies:

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI methods are enhancing target identification, compound design, and prediction of binding affinities [2] [12].

- Cryo-EM Advances: Improving resolution and throughput enables more targets to be accessible for structure-based design [2] [11].

- Chemical Proteomics: Methods like thermal proteome profiling (TPP) enable target deconvolution and identification of mechanism of action [14].

- Gene Editing Technologies: CRISPR-based approaches facilitate more physiologically relevant target validation in native cellular contexts [15].

These technologies are expanding the scope and success rate of target-based approaches, particularly for challenging target classes that were previously considered "undruggable."

The rise of target-based screening represents a definitive paradigm shift in pharmaceutical research, enabled by the molecular biology revolution. This approach has demonstrated significant strengths in enabling rational drug design, providing mechanistic clarity, and facilitating the development of targeted therapies for specific patient populations. The quantitative success of target-based approaches is evidenced by numerous approved therapies across therapeutic areas, particularly where disease mechanisms are well-understood.

However, the comparative analysis with phenotypic screening reveals a more nuanced picture—each approach possesses distinct advantages and optimal applications. Rather than a binary choice, modern drug discovery increasingly leverages both strategies in complementary workflows: phenotypic screening to identify novel biology and target-based approaches to optimize therapeutic candidates. This integrated model, enhanced by emerging technologies in AI, structural biology, and chemical proteomics, represents the future of pharmaceutical innovation, promising more effective and targeted therapies for complex diseases.

The strategic selection between phenotypic and target-based approaches ultimately depends on the specific biological context, disease complexity, and stage of therapeutic development, with the most successful drug discovery programs maintaining flexibility to leverage both paradigms as appropriate to their specific challenges and opportunities.

In the pursuit of new medicines, two distinct philosophical approaches have emerged: target-agnostic (phenotypic) discovery and hypothesis-driven (target-based) discovery. The target-agnostic strategy identifies drugs based on their observable effects on disease phenotypes—such as cell death or morphological changes—without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [16] [1]. In contrast, the hypothesis-driven approach begins with a predefined molecular target, typically a protein understood to play a critical role in the disease mechanism, and seeks compounds that modulate its activity [10] [17]. Historically, many pioneering medicines were discovered through phenotypic observation. However, with the advent of molecular biology and genomics, the target-based paradigm became dominant for its precision and rational design [16]. A pivotal 2012 analysis revealing that a majority of first-in-class drugs from 1999-2008 originated from phenotypic approaches catalyzed a major resurgence in this methodology, establishing it as a systematic and complementary discovery route [16] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two philosophies, examining their success rates, experimental protocols, and practical applications for modern drug discovery.

Success Rates and Comparative Performance

Quantitative analyses of new drug approvals provide critical insight into the relative strengths of each discovery paradigm. The following table summarizes key performance metrics, particularly the ability to deliver innovative, first-in-class therapies.

Table 1: Comparative Success Rates of Discovery Philosophies for New Medicines (1999-2017)

| Discovery Philosophy | Total Drugs Approved (1999-2017) | First-in-Class Drugs (1999-2008) | Representative Approved Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Agnostic (Phenotypic) | 58 [1] | 28 (Majority) [16] [18] | Risdiplam, Daclatasvir, Ivacaftor/Lumacaftor, Vamorolone [16] [1] |

| Hypothesis-Driven (Target-Based) | 44 [1] | 17 [16] [18] | Imatinib, Trastuzumab, HIV Antiretroviral Therapies [10] |

| Monoclonal Antibody-Based | 29 [1] | N/A |

The data reveals a clear trend: phenotypic screening has been disproportionately successful in generating first-in-class medicines [16] [18]. This is largely attributed to its unbiased nature, which allows for the identification of novel mechanisms of action (MoA) and the expansion of "druggable" target space to include unexpected cellular processes and multi-target therapies (polypharmacology) [16]. For example, the cystic fibrosis therapy Ivacaftor and the spinal muscular atrophy treatment Risdiplam were both discovered without a pre-specified target hypothesis, revealing entirely new MoAs after their efficacy was established [16] [1].

The hypothesis-driven approach, while slightly less prolific in producing first-in-class drugs, excels in developing highly selective, optimized therapies, especially for diseases with well-understood molecular pathways. It provides a straightforward path for rational drug design and optimization once a validated target is available [10]. The development of Imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia and trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer are prime examples of this precision [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The core philosophies necessitate distinct experimental workflows, from initial screening to lead optimization. The following diagrams and descriptions detail the standard protocols for each approach.

Target-Agnostic (Phenotypic) Screening Workflow

The phenotypic screening workflow is a cyclic process of testing and analysis centered on a biologically relevant disease model. The following diagram maps this multi-stage protocol.

Diagram 1: Phenotypic screening is an iterative process centered on a functional assay.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Screening:

- Step 1: Compound Library Screening. A diverse library of compounds is screened against a disease-relevant biological system. This system can range from 2D cell cultures to more complex 3D organoids or even whole organisms [16] [1]. High-content screening (HCS) is often employed, which uses automated microscopy and image analysis to capture complex phenotypic data [1].

- Step 2: Hit Identification. "Hits" are identified based on their ability to induce a therapeutically desirable phenotypic change (e.g., reversal of a disease-associated morphology, inhibition of pathogen replication, or induction of cancer cell death) [10]. The specific molecular target responsible for this change remains unknown at this stage.

- Step 3: Hit Validation and Lead Optimization. Confirmed hits undergo further testing in secondary, more complex phenotypic assays to validate the biological effect. Medicinal chemistry is then used to improve the drug's properties (potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetics), guided primarily by the phenotypic readouts, not target binding [16].

- Step 4: Target Deconvolution. A critical and often challenging phase where the MoA of the optimized lead compound is investigated. Techniques such as chemical proteomics, resistance generation, and functional genomics (e.g., CRISPR screens) are used to identify the specific molecular target(s) engaged by the compound [16]. For some drugs, like lithium for bipolar disorder, the precise target may remain unknown even after approval [10].

Hypothesis-Driven (Target-Based) Screening Workflow

The target-based workflow is a linear, hypothesis-testing process that begins with a deep understanding of disease biology. The following diagram outlines its sequential stages.

Diagram 2: The hypothesis-driven process is a linear path from target validation to candidate.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Target-Based Screening:

- Step 1: Target Identification and Validation. A specific molecular target (e.g., a kinase, receptor, or ion channel) is identified and rigorously validated as critical to the disease process. Techniques include genetic association studies, gene knockout/knockdown, and proteomic analyses [10] [17].

- Step 2: Assay Development. A robust in vitro assay is developed to measure compound activity against the purified target or a simplified cellular system. Examples include enzymatic activity assays, ligand-binding displacement assays (e.g., AlphaScreen), or cell-based reporter assays [10] [19].

- Step 3: High-Throughput Screening (HTS). The target-specific assay is automated and used to screen large compound libraries (often >1 million compounds) to identify "hits" that modulate the target's activity [10].

- Step 4: Hit-to-Lead and Lead Optimization. Confirmed hits are refined into lead compounds. The known target structure enables rational drug design using techniques like molecular docking and structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis to systematically improve affinity, selectivity, and drug-like properties [7] [17]. Tools like CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) are used to confirm target engagement in a cellular environment [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The execution of both discovery philosophies relies on a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the featured experiments and general workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Discovery Philosophies

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Organoids / Complex Cell Models | Provides a human-relevant, physiologically complex disease model for phenotypic screening [5]. | Target-Agnostic |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Measures drug-target engagement directly in intact cells or tissues, confirming mechanistic action [7]. | Both (Validation) |

| Phage/Yeast Display Libraries | Genotype-phenotype coupled libraries for target-agnostic antibody discovery against complex antigen mixtures (e.g., cell surfaces) [20]. | Target-Agnostic |

| High-Content Screening (HCS) Systems | Automated imaging systems that extract multiparametric morphological data from cells for rich phenotypic profiling [1]. | Target-Agnostic |

| Recombinant Proteins | Isolated, purified target proteins used to develop specific biochemical assays for high-throughput screening [17]. | Hypothesis-Driven |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., Glide, AutoDock) | In silico tools for predicting how a small molecule binds to a protein target of known structure, guiding optimization [7] [17]. | Hypothesis-Driven |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure DB | AI-predicted protein structures provide 3D target models for rational design when experimental structures are unavailable [17]. | Hypothesis-Driven |

Strategic Application and Future Outlook

The choice between target-agnostic and hypothesis-driven philosophies is not a matter of superiority but strategic alignment with project goals and biological context.

Phenotypic screening is most advantageous when: the goal is to discover a first-in-class medicine with a novel mechanism of action, when the disease pathophysiology is complex or poorly understood (e.g., Alzheimer's disease, psychiatric disorders), or when pursuing polypharmacology (multi-target drugs) for complex diseases [16] [10]. Its main challenges are the complexity and cost of assays, and the difficult process of target deconvolution [16] [10].

Target-based screening is most advantageous when: a well-validated molecular target with a clear causal link to the disease exists, as seen in many cancers and genetic disorders. It is highly efficient, cost-effective for HTS, and simplifies lead optimization due to the known target [10] [17]. Its primary risk is clinical failure if the initial hypothesis about the target's role in the human disease is incorrect [10].

The future of drug discovery lies in the strategic integration of both approaches, powered by new technologies. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are accelerating both paradigms—from analyzing high-content phenotypic images to predicting protein structures and generating novel hit molecules in silico [21] [1] [7]. Furthermore, advanced in vitro models like 3D organoids and organs-on-chips are providing more physiologically relevant systems for phenotypic screening, bridging the gap between traditional cell assays and clinical efficacy [5]. By understanding the core distinctions and complementary strengths of these two philosophies, researchers can more effectively navigate the path to breakthrough therapies.

The strategic choice between phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) and target-based drug discovery (TDD) represents a fundamental crossroads in pharmaceutical research. For decades, the pendulum has swung between these two approaches, heavily influenced by technological capabilities and prevailing scientific dogma. Historically, many medicines were discovered through observation of their effects on disease physiology, a form of phenotypic screening. With the advent of the molecular biology revolution in the 1980s and the sequencing of the human genome in 2001, the industry focus dramatically shifted to the powerful but reductionist approach of modulating specific molecular targets [16].

A pivotal 2008 analysis covering 1999-2008 revealed a surprising finding: the majority of first-in-class drugs were discovered empirically without a predefined drug target hypothesis [16]. This revelation, published in 2011, triggered a major resurgence of interest in phenotypic approaches. Since 2011, modern phenotypic drug discovery has re-emerged as a systematic pursuit of therapeutic effects in realistic disease models, combining the original concept with contemporary tools and strategies [16]. This guide quantifies the industry's adoption rates of these competing paradigms from 2012 to the present, examining the quantitative evidence behind this strategic shift.

Quantitative Analysis of Adoption Rates (2012-Present)

Industry-Wide Adoption Trends

Comprehensive analysis of pharmaceutical portfolios reveals a substantial increase in the adoption of phenotypic screening approaches over the past decade. The data demonstrates a consistent upward trajectory in PDD implementation across major research organizations.

Table 1: Industry Adoption Rates of Phenotypic Screening (2012-2022)

| Year | Adoption Rate (%) | Data Source | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | <10% | Novartis Portfolio Analysis [1] | Post-genomic focus on validated targets |

| 2015 | ~25% | Novartis Portfolio Analysis [1] | Growing recognition of PDD success in first-in-class drugs |

| 2022 | 25-40% | AstraZeneca and Novartis Portfolio Analysis [1] | Accumulation of PDD successes; improved disease models |

The expansion of phenotypic approaches is particularly evident in specific therapeutic areas. Oncology and infectious diseases have led this adoption, followed closely by neuroscience and rare genetic disorders [16] [1]. The driving forces behind this shift include the remarkable track record of PDD in delivering first-in-class medicines and technological advancements that have made complex phenotypic assays more reproducible and scalable.

Success Rate Comparison: PDD vs. TDD

The quantitative superiority of phenotypic screening in generating innovative therapies provides the fundamental rationale for its renewed adoption. Multiple analyses of FDA-approved drugs consistently demonstrate PDD's disproportionate contribution to pioneering therapeutics.

Table 2: Success Rate Analysis of Discovery Approaches (1999-2017)

| Discovery Strategy | Number of Approved Drugs | First-in-Class Medicines | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic Drug Discovery | 58 | 28 (Primary Source) | Risdiplam, Daclatasvir, Lumacaftor [1] |

| Target-Based Drug Discovery | 44 | 17 | Imatinib, Selective kinase inhibitors [16] |

| Monoclonal Antibody Therapies | 29 | N/A | Various biologic therapies [1] |

This success rate advantage is particularly pronounced for unprecedented mechanisms of action and historically "undruggable" targets. Between 1999 and 2008, PDD accounted for 28 first-in-class small molecule drugs compared to just 17 from target-based methods [16] [1]. This trend has continued in the subsequent decade, with PDD contributing transformative treatments for conditions including spinal muscular atrophy (risdiplam), cystic fibrosis (lumacaftor/ivacaftor), and hepatitis C (daclatasvir) [16] [1].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Analysis

Methodologies for Quantifying Screening Outcomes

Robust experimental protocols are essential for objectively comparing the performance of phenotypic and target-based screening approaches. The following methodologies represent standardized frameworks employed in key studies cited within this analysis.

High-Content Phenotypic Screening Protocol

Objective: To identify compounds that produce a desired phenotypic change in disease-relevant cellular models without preconceived target hypotheses.

Workflow:

- Model System Selection: Utilize physiologically relevant cell types (primary cells, iPSC-derived cells, or engineered cell lines) expressing disease-associated phenotypes. 3D cultures, co-cultures, or organoids are increasingly employed for enhanced biological relevance [5].

- Assay Development: Implement multiplexed readouts capturing multiple phenotypic features simultaneously (morphology, proliferation, apoptosis, protein localization/organization).

- Compound Screening: Screen diverse chemical libraries (10,000-100,000 compounds) using automated liquid handling systems.

- Image Acquisition: Employ high-content imaging systems to capture multiparametric data.

- Data Analysis: Extract ~1,000 quantitative morphological features per cell using machine learning algorithms. Cluster phenotypes and identify hit compounds inducing desired phenotypic profiles [1].

Validation: Confirm hits in secondary assays using orthogonal detection methods and dose-response curves (10-point dilution series).

Target-Based Screening Validation Protocol

Objective: To identify compounds modulating a specific molecular target with known disease relevance.

Workflow:

- Target Selection: Prioritize targets with strong genetic validation (human genetics, functional genomics) and understood biological function.

- Assay Development: Implement biochemical or simple cellular assays measuring direct target engagement (binding assays, enzymatic activity inhibition/activation).

- Compound Screening: Screen focused chemical libraries enriched for target class expertise.

- Counter-Screening: Test against related targets to establish selectivity profile.

- Cellular Efficacy: Confirm functional activity in cellular models expressing the target.

Validation: Demonstrate direct target engagement using biophysical methods (SPR, ITC) and cellular target engagement assays (CETSA, NanoBRET).

Performance Metrics for Screening Approaches

Standardized metrics enable direct comparison between screening strategies. The following quantitative measures are essential for objective evaluation:

Table 3: Essential Performance Metrics for Screening Approaches

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate | (Confirmed Hits / Compounds Screened) × 100 | Screening efficiency; typically 0.1-1% for PDD vs 0.5-5% for TDD |

| Attrition Rate | (Candidates failing / Total candidates) × 100 | Predictive validity; TDD often shows higher late-stage attrition |

| Chemical Diversity | Scaffold clusters per 100 hits | Structural novelty; PDD typically identifies more diverse chemotypes |

| Success to Clinic | (Clinical candidates / Discovery programs) × 100 | Ultimate productivity measure |

Visualization of Screening Pathways and Outcomes

Comparative Success of Discovery Approaches

Modern Phenotypic Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of phenotypic screening requires specialized reagents and tools that enable biologically relevant assay development and sophisticated readouts.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Modern Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Cell Models | iPSC-derived cells, Primary organoids, 3D co-culture systems [5] | Provide human-relevant disease biology beyond transformed cell lines |

| Biosensors | GFP-tagged proteins, FRET reporters, Calcium flux indicators | Enable dynamic monitoring of pathway activation and cellular responses |

| Phenotypic Dyes | Mitochondrial membrane potential dyes, Cell viability indicators, Apoptosis markers | Facilitate multiparametric assessment of cell health and function |

| High-Content Imaging Reagents | Multiplexable fluorescent antibodies, Live-cell compatible dyes, Nuclear stains | Support automated extraction of morphological features |

| Pathway Reporters | Luciferase-based pathway assays, CRE-reporter systems, Promoter-specific constructs | Enable monitoring of specific signaling pathway modulation |

| Cytokine Panels | Multiplex cytokine arrays, Chemokine panels, Growth factor maps | Characterize immune and secretory responses in complex models |

The quantitative evidence from 2012 to present demonstrates a substantial and sustained shift toward phenotypic screening strategies within pharmaceutical R&D. The adoption rates of PDD have increased from less than 10% to 25-40% of project portfolios in leading organizations, driven by its demonstrated superiority in generating first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action [1]. This trend reflects an evolving understanding of biological complexity and the limitations of exclusively reductionist approaches.

The integration of advanced disease models (organoids, 3D cultures), sophisticated detection methods (high-content imaging), and computational tools (machine learning, AI) has addressed historical limitations of phenotypic screening while preserving its fundamental advantage: the ability to discover therapeutics without predetermined target biases [16] [5] [1]. This technological convergence suggests that the observed adoption trends will not only continue but likely accelerate, particularly for diseases with complex biology and unmet medical needs.

The optimal discovery strategy increasingly appears to be a hybrid approach that leverages the target-agnostic innovation potential of phenotypic screening alongside the precision and efficiency of target-based methods once mechanisms are established. This integrated framework represents the future of therapeutic discovery—one that respects biological complexity while employing increasingly sophisticated tools to decipher and modulate it.

Strategic Implementation: When and How to Apply Phenotypic and Target-Based Methods

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) has undergone a significant resurgence over the past decade, reclaiming its position as a powerful approach for identifying first-in-class therapies. This renewed interest follows a systematic analysis revealing that between 1999 and 2008, 28 first-in-class small molecule drugs were discovered through phenotypic methods compared to 17 from target-based approaches [1]. Modern PDD combines the original concept of observing therapeutic effects on disease physiology with advanced tools and strategies, enabling systematic drug discovery based on therapeutic effects in biologically relevant disease models [16]. Unlike target-based drug discovery (TDD), which relies on modulation of specific molecular targets with established causal relationships to disease, PDD operates in a target-agnostic fashion, focusing on measurable changes in disease phenotypes or biomarkers without requiring prior knowledge of the underlying molecular mechanism [2] [16]. This fundamental difference allows phenotypic screening to expand the "druggable target space" to include unexpected cellular processes and novel mechanisms of action that might otherwise remain undiscovered [16].

The strategic value of PDD lies in its ability to capture the complexity of biological systems and identify therapeutic interventions that address multifaceted disease mechanisms. As a result, pharmaceutical companies have dramatically increased their implementation of phenotypic screens, with estimates suggesting they now constitute 25-40% of the project portfolio of major pharmaceutical companies such as AstraZeneca and Novartis [1]. This strategic shift is powered by advancements in disease modeling, high-content imaging technologies, and computational analysis methods that have addressed historical challenges associated with phenotypic approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Drug Discovery Approaches

| Parameter | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Focus on observable traits/phenotypes in response to treatment [22] | Focus on modulation of specific, pre-validated molecular targets [2] |

| Target Requirement | No prior knowledge of molecular target required [1] | Well-characterized molecular target essential [2] |

| System Complexity | Uses complex biological systems (cells, tissues, organisms) [2] | Typically reductionist systems (purified proteins, simple cellular assays) [2] |

| Success Rate (First-in-Class) | 28 drugs (1999-2008) [1] | 17 drugs (1999-2008) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Identifies novel mechanisms; captures system complexity [16] | Enables rational drug design; typically faster timeline [2] |

| Primary Challenge | Target deconvolution; complex data interpretation [2] | Limited to known biology; may miss complex interactions [2] |

Technological Foundations of Modern Phenotypic Screening

High-Content Imaging and Analysis

High-content screening (HCS) represents the technological backbone of modern phenotypic discovery, using automated microscopy to generate rich, high-dimensional datasets that capture diverse cellular phenotypes. The Cell Painting protocol has emerged as a particularly powerful and widely adopted HCS method, using six fluorescent dyes imaged across five channels to examine multiple cellular components and organelles simultaneously: nuclei (Hoechst 33342), endoplasmic reticulum (concanavalin A–AlexaFluor 488), mitochondria (MitoTracker Deep Red), F-actin (phalloidin–AlexaFluor 568), Golgi apparatus and plasma membranes (wheat germ agglutinin–AlexaFluor 594), and nucleoli/cytoplasmic RNA (SYTO14) [23]. This comprehensive labeling strategy enables the extraction of hundreds of morphological features—including texture, shape, intensity, and spatial relationships—creating detailed phenotypic profiles that characterize cytological responses to chemical or genetic perturbations [24] [23].

Advanced statistical frameworks are essential for interpreting the complex data generated by HCS. Traditional analysis methods that aggregate cellular data into summary statistics (e.g., means, medians, Z-scores) often fail to capture important biological information, particularly when treatments create subpopulations of cells with different responses [24]. Modern analytical approaches instead utilize cell-level feature distributions and advanced metrics like the Wasserstein distance to detect subtle phenotypic changes that would be masked by well-averaged measures [24]. These methods can identify diverse response patterns, including global shifts in cellular feature distributions, stretching of distribution tails, or the emergence of bimodal distributions indicating heterogeneous cell responses [24]. The analytical workflow typically includes quality control measures, positional effect adjustment, data standardization, feature reduction, and phenotypic profiling to ensure robust and interpretable results [24].

Advanced Disease Models for Phenotypic Screening

The translational relevance of phenotypic screens depends heavily on the biological fidelity of the model systems employed. While traditional immortalized cell lines remain useful for certain applications, the field has increasingly shifted toward more human-relevant models that better recapitulate disease physiology [25]. Key advancements in this area include:

Patient-Derived Organoids: Self-organizing 3D structures that mimic key aspects of native tissues, derived directly from patient samples. These models preserve disease-specific characteristics and have been successfully used for phenotypic screening in cancer, inflammatory, and genetic diseases [25] [23].

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Systems: Reprogrammed adult cells that can be differentiated into various cell types, enabling disease modeling and compound screening in otherwise inaccessible human cell types, such as neurons or cardiomyocytes [25].

Complex Co-Culture Systems: Models incorporating multiple cell types to better mimic tissue microenvironment and cell-cell interactions, particularly valuable for immuno-oncology and inflammation research [23].

The industrialization of these complex biological models through automated cell culture systems (e.g., CellXpress.ai) has been crucial for enabling their use in early drug discovery, providing the reproducibility and scalability necessary for high-throughput phenotypic screening [25].

Innovative Methodologies: Compressed and Pooled Screening Approaches

Traditional phenotypic screens face significant scalability challenges when using high-content readouts and complex disease models due to resource constraints. Compressed screening has emerged as an innovative solution to this limitation, enabling researchers to pool multiple perturbations together while still deconvolving individual compound effects through computational methods [23]. This approach dramatically reduces the sample number, cost, and labor requirements—by a factor of P (pool size)—while maintaining the ability to identify bioactive compounds [23].

The fundamental principle behind compressed screening involves combining N perturbations into unique pools of size P, with each perturbation appearing in R distinct pools overall [23]. Following experimental execution, a computational framework based on regularized linear regression and permutation testing deconvolves the effects of individual perturbations from the pooled results [23]. Benchmarking studies using a 316-compound FDA drug repurposing library and Cell Painting readout have demonstrated that compressed screening can reliably identify compounds with the largest effects even at high compression levels (up to 80 drugs per pool) [23]. This approach has been successfully applied to map transcriptional responses to tumor microenvironment protein ligands in pancreatic cancer organoids and to identify immunomodulatory compounds in primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [23].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

| Experimental Stage | Key Procedures | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Development | - Cell model selection & validation- Marker panel design- Staining optimization- Image acquisition parameter optimization | - Ensure disease relevance- Minimize fluorescence bleed-through- Balance complexity with practicality- Include relevant positive/negative controls [24] |

| Screening Execution | - Compound/library application- Incubation period determination- Fixation/staining- Automated image acquisition | - Address positional effects through plate design- Include adequate controls across plates- Standardize incubation conditions- Implement quality control checkpoints [24] [23] |

| Image Analysis | - Illumination correction- Cell segmentation- Feature extraction- Data normalization | - Use appropriate segmentation algorithms- Extract comprehensive feature sets- Account for technical variability- Apply batch effect correction [24] |

| Data Processing | - Positional effect adjustment- Cell-level data standardization- Feature selection & reduction- Phenotypic profile generation | - Use methods like median polish for positional effects- Employ distribution-based statistics- Select most informative features- Create phenotypic fingerprints [24] |

| Hit Identification | - Multivariate distance calculation- Phenotypic clustering- Dose-response analysis- Hit confirmation | - Use Mahalanobis Distance for effect size- Identify phenotypic clusters- Validate through dose-response- Confirm in secondary assays [23] |

Success Stories: Therapeutic Breakthroughs from Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening has generated numerous therapeutic breakthroughs across diverse disease areas, particularly for conditions with complex or poorly understood pathophysiology. These successes highlight the power of phenotypic approaches to identify novel mechanisms and first-in-class medicines:

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA): Risdiplam (Evrysdi) was discovered through phenotypic screening that identified small molecules modulating SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase levels of functional SMN protein [1] [16]. This unprecedented mechanism of action—stabilizing the U1 snRNP complex to promote inclusion of exon 7—would have been unlikely discovered through target-based approaches, as SMN2 lacked known functional activity and would not have been selected as a target in traditional campaigns [1] [16]. Approved in 2020, risdiplam represents the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF): Ivacaftor, lumacaftor, tezacaftor, and elexacaftor were all identified through phenotypic screens using cell lines expressing wild-type or disease-associated CFTR variants [1] [16]. These compounds work through distinct mechanisms—ivacaftor acts as a "potentiator" that improves CFTR channel gating, while the "correctors" enhance CFTR folding and plasma membrane insertion [16]. The combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta) addresses 90% of the CF patient population and represents a transformative therapy for this previously fatal genetic disease [16].

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV): Daclatasvir (Daklinza) was identified through a HCV replicon phenotypic screen and later found to target NS5A, a viral protein with no enzymatic activity that is essential for HCV replication [1] [16]. As a protein with no known enzymatic function and an incompletely understood mechanism, NS5A remained an elusive target for traditional drug discovery approaches [1]. Daclatasvir became the first in the class of NS5A inhibitors and a key component of curative DAA combinations for HCV [16].

Oncology: Thalidomide and its analogs (lenalidomide, pomalidomide) were discovered and optimized exclusively through phenotypic screening [2]. Their molecular target (cereblon) and mechanism of action (altering substrate specificity of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex) were only elucidated years after clinical approval [2] [16]. This novel mechanism is now being intensively explored in targeted protein degradation strategies, including PROTACs, representing one of the most exciting new modalities in drug discovery [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Successful implementation of phenotypic screening workflows requires careful selection and optimization of research reagents and technologies. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications in modern phenotypic screening:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Technology | Primary Function | Application Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | Comprehensive morphological profiling using 6 fluorescent dyes [23] | - Standardized protocol enables cross-study comparisons- Captures ~1,000+ morphological features- Compatible with automated image analysis pipelines | |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Validation of target engagement in intact cells and tissues [7] | - Confirms direct binding in physiological environments- Useful for mechanism of action studies | - Compatible with high-resolution mass spectrometry |

| CRISPR Screening | Functional genomics for target identification and validation [6] | - Systematically investigates gene-drug interactions- Can be combined with phenotypic readouts (Perturb-seq)- Enables identification of resistance mechanisms | |

| Advanced Disease Models | Physiologically relevant screening systems [25] | - Patient-derived organoids maintain disease characteristics- iPSC systems enable human cell type screening- Co-culture models incorporate microenvironment interactions | |

| Automated Cell Culture Systems | Industrialized production of complex biological models [25] | - Enables scalable production of organoids and iPSCs- Improves reproducibility and standardization- Reduces manual labor and increases capacity | |

| AI/ML Analysis Platforms | High-dimensional data analysis and pattern recognition [22] [1] | - Identifies subtle phenotypic patterns | - Enables mechanism of action prediction- Accelerates hit identification and prioritization |

The evolution of phenotypic screening from a serendipity-dependent process to a systematic discovery engine represents a fundamental shift in drug discovery philosophy. Rather than positioning phenotypic and target-based approaches as competing strategies, the most productive path forward involves integrating both paradigms to leverage their complementary strengths [2]. Modern drug discovery pipelines increasingly employ hybrid workflows that use phenotypic screening for novel target and mechanism identification, followed by target-based approaches for lead optimization and mechanistic characterization [2].

This integration is being accelerated by advancements in artificial intelligence, multi-omics technologies, and functional genomics that bridge the historical gap between phenotypic observations and molecular mechanisms [2]. AI and machine learning play particularly important roles in parsing complex, high-dimensional phenotypic datasets and identifying predictive patterns that link morphological profiles to biological mechanisms [22] [1]. Furthermore, innovations in target deconvolution methods, including chemical proteomics, functional genomics, and bioinformatics, have dramatically improved our ability to identify the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic hits [2] [16].

As these trends continue, phenotypic screening will likely become increasingly central to drug discovery efforts, particularly for complex diseases where single-target approaches have shown limited success. The ongoing development of more physiologically relevant models, higher-content readouts, and more sophisticated analytical approaches will further enhance the predictive value and productivity of phenotypic screening, cementing its role as an indispensable tool for discovering the next generation of transformative medicines.

In modern drug discovery, two primary screening strategies are employed: target-based screening and phenotypic screening. Target-based screening begins with a specific, well-characterized molecular target—often a protein, enzyme, or receptor with a established role in disease pathology. This approach uses high-throughput technologies to identify compounds that interact with this predefined target, enabling rational drug design based on detailed knowledge of the target's structure and function [2] [10]. In contrast, phenotypic screening takes a more holistic approach by identifying compounds based on their measurable effects on cells, tissues, or whole organisms without requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular mechanism of action [2]. This method captures the complexity of biological systems and has been instrumental in discovering first-in-class therapies, particularly for diseases with poorly understood underlying mechanisms [2] [10].

The strategic choice between these approaches has significant implications for drug discovery success rates, resource allocation, and eventual clinical outcomes. Target-based screening has gained substantial prominence within the pharmaceutical industry, supported by advances in automation, bioinformatics, and structural biology. The global market for high-throughput screening (HTS), which is predominantly target-based, is experiencing robust growth—projected to increase from USD 32.0 billion in 2025 to USD 82.9 billion by 2035, registering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.0% [26]. Another analysis predicts the HTS market will reach USD 18.8 billion by 2029, expanding at a CAGR of 10.6% [27]. This growth is largely driven by rising research and development investments in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, along with continuous technological innovations in automation and analytical capabilities [26] [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Screening Approaches in Drug Discovery

| Feature | Target-Based Screening | Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Defined molecular target [2] | Observable biological effect [2] |

| Throughput | Typically high [10] | Variable, often lower [10] |

| Mechanism Understanding | Known from outset [2] | Requires target deconvolution [2] |

| Key Advantage | Precision and rational design [10] | Captures biological complexity [2] [10] |

| Key Challenge | Relies on validated targets [2] | Resource-intensive and slower [10] |

| Notable Drug Examples | Imatinib, Trastuzumab [10] | Artemisinin, Lithium [10] |

Market Landscape and Adoption Trends

The adoption of target-based screening platforms continues to accelerate across the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors. Within the technology segment of the high-throughput screening market, cell-based assays currently dominate with a 39.40% share [26]. These assays provide physiologically relevant data and predictive accuracy in early drug discovery by allowing direct assessment of compound effects in biological systems [26]. However, ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) technology is anticipated to expand at a faster CAGR of 12% through 2035 [26]. This growth is fueled by uHTS's unprecedented ability to screen millions of compounds rapidly, enabling comprehensive exploration of chemical space and enhancing the probability of identifying novel therapeutic candidates [26].

The application of high-throughput screening for target identification represents another rapidly growing segment, projected to register a 12% CAGR from 2025 to 2035 [26]. This application is crucial for swiftly evaluating large chemical libraries against diverse biological targets, thereby accelerating the drug development process by identifying promising therapeutic candidates with high specificity and efficacy [26]. Technological advancements in automation and robotics have significantly improved the efficiency and throughput of these screening platforms, establishing them as indispensable tools for target identification in modern drug discovery [26].

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Market Outlook by Application (2025-2035)

| Application Segment | Market Share (2025) | Projected CAGR | Primary Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Screening | 42.70% [26] | -- | Essential role in identifying active compounds from large libraries [26] |

| Target Identification | Significant segment [26] | 12% [26] | Ability to rapidly assess chemical libraries against multiple biological targets [26] |

| Toxicology | -- | -- | Increasing demand for early toxicity testing [26] |

From a geographical perspective, North America dominates the high-throughput screening market, accounting for approximately 50% of global market share [26] [27]. This leadership position is attributed to several factors including a strong biotechnology startup ecosystem, significant government investment in drug research, a robust biopharmaceutical industry, and heightened focus on addressing unmet medical needs [26]. The United States high throughput screening ecosystem specifically is anticipated to grow at a CAGR of 12.6% through 2035 [26]. Meanwhile, the Asia-Pacific region is emerging as the fastest-growing market, driven by increasing digital technology adoption by pharmaceutical companies and expanding collaborations with contract research organizations (CROs) [28] [29].

Technological Framework of Target-Based Screening

Core Components and Workflow

Target-based screening platforms integrate multiple advanced technologies to enable efficient drug discovery. The foundational infrastructure typically includes robotic automation systems for liquid handling and assay execution, microplate readers for absorbance and luminescence detection, and sophisticated data acquisition systems for processing large datasets [27]. These components work in concert to facilitate the screening of thousands to millions of compounds against specific biological targets in remarkably short timeframes. A key technological advancement has been assay miniaturization, implemented through multiplex assays and plate replication, which dramatically boosts productivity while reducing the time and cost associated with compound library screening [27].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has revolutionized target-based screening platforms. AI/ML-based drug discovery solutions currently represent the largest segment within the drug discovery SaaS platforms market, holding a 30% revenue share [28] [29]. These technologies enhance screening efficiency and precision by enabling more accurate analysis of large datasets, predicting compound behavior, and optimizing trial design [28]. The adoption of AI-driven platforms is particularly prominent in pharmaceutical companies, which account for 55% of the end-user market for drug discovery SaaS platforms [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A representative example of a target-based screening protocol comes from recent glioblastoma (GBM) research, which utilized a kinase inhibitor library to identify subtype-specific therapeutic vulnerabilities [30]. This study established a robust high-throughput screening assay using lineage-based GBM models to identify both common and subtype-specific small molecule inhibitors.

Experimental Workflow for Kinase Inhibitor Screening [30]:

- Cell Culture Preparation: Primary mouse GBM Type 1 and Type 2 cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 serum-free medium supplemented with B27 and N2, plus specific growth factors (EGF, Nrg1, and PDGF-AA).

- Assay Optimization: Parameters including cell density (500 cells/well), medium volume (40 μL/well), and incubation time (5 days post-treatment) were systematically optimized in 384-well plate formats to achieve high signal-to-noise ratios.

- Screening Execution: A kinase inhibitor library containing 900 compounds was screened in parallel against both GBM subtypes using CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay to measure intracellular ATP levels as a surrogate for cellular viability.

- Data Analysis: Hit selection was performed based on viability reduction compared to controls, with identification of common inhibitors (84 compounds), Type 1-specific inhibitors (11 compounds), and Type 2-specific inhibitors (18 compounds).

- Validation: Candidate compounds underwent confirmation screens and dose-response assays (IC50 determination) to verify subtype-specific activity.

This methodology successfully identified R406 and Ponatinib as selective inhibitors of Type 2 GBM cells, and further demonstrated synergistic effects between R406 and Tucatinib in Type 2 cells, providing a rationale for combination therapy approaches [30].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Success Rates and Efficiency Metrics

Target-based screening platforms demonstrate distinct advantages in throughput and efficiency compared to phenotypic approaches. Studies indicate that high-throughput screening can improve hit identification rates by up to 5-fold compared to traditional methods [27]. The implementation of ultra-high-throughput screening technologies has further enhanced capacity, with some platforms capable of screening 10,000 times faster than conventional techniques [27]. This dramatic improvement in efficiency translates to significant cost reductions, with reports indicating that HTS can lower operational costs by approximately 15% while improving forecast accuracy by about 20% [27].

The application of target-based screening in oncology drug discovery has been particularly productive. Currently, the oncology segment holds a 35% share of the drug discovery SaaS platforms market by therapeutic area [28] [29]. The dominance of this segment is largely attributable to the precision offered by target-based approaches, which enable researchers to identify novel oncogenic targets and design personalized treatment strategies through computational oncology tools [28]. This targeted approach has accelerated the discovery of immunotherapies and precision drugs, particularly for rare cancers with defined molecular drivers [28].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Target-Based Screening Platforms

| Performance Metric | Target-Based Screening | Industry Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Identification Rate | Up to 5-fold improvement [27] | Faster lead candidate identification |

| Screening Throughput | 10,000x faster than traditional methods [27] | Rapid compound library screening |

| Operational Cost Reduction | ~15% [27] | More efficient resource allocation |

| Development Timeline Reduction | ~30% [27] | Accelerated time to market |

| Forecast Accuracy Improvement | ~20% [27] | Better pipeline planning |

Integration with Computational Approaches

The convergence of target-based screening with advanced computational methods has created powerful hybrid approaches for drug discovery. Bioinformatics and computational chemistry techniques now enable researchers to efficiently identify key molecular targets and screen potential compounds with high binding affinities [31]. Molecular docking simulations and molecular dynamics (MD) analyses provide critical insights into binding stability between compounds and protein targets, facilitating rational drug design [31].