Phenotypic Screening Hit Validation: Strategies for Confirming Bioactive Compounds in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating hits from phenotypic screens.

Phenotypic Screening Hit Validation: Strategies for Confirming Bioactive Compounds in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating hits from phenotypic screens. It covers the foundational principles of phenotypic drug discovery, outlines a multi-tiered methodological framework for hit confirmation and triage, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and explores advanced validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and success rate of transitioning phenotypic screening hits into viable lead candidates.

Understanding Phenotypic Screening and the Critical Need for Rigorous Hit Validation

Modern drug discovery is primarily executed through two distinct strategies: phenotypic screening (PS) and target-based screening (TBS). Phenotypic screening involves selecting compounds based on their ability to modify a disease-relevant phenotype in cells, tissues, or whole organisms, without prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [1]. In contrast, target-based screening employs assays designed to interact with a predefined, purified molecular target, typically a protein, to identify compounds that modulate its activity [2]. The strategic choice between these approaches has profound implications for screening design, hit validation, and clinical success. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

Core Conceptual Differences

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in the initial screening premise. Phenotypic screening is target-agnostic, focusing on the overall therapeutic effect within a biologically complex system, while target-based screening is reductionist, focusing on a specific, hypothesized mechanism of action [1] [3].

Phenotypic Screening operates on the principle that a disease phenotype—such as aberrant cell morphology, death, or secretion of a biomarker—can be reversed by a compound, regardless of its specific protein target. This strategy is particularly valuable when the understanding of disease pathophysiology is incomplete or when the goal is to discover first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms [1]. Successes like the cystic fibrosis corrector lumacaftor and the spinal muscular atrophy therapy risdiplam were discovered through phenotypic screens, and their precise molecular targets and mechanisms were elucidated years later [1] [3].

Target-Based Screening requires a well-validated hypothesis that modulation of a specific protein target will yield a therapeutic benefit. This approach dominates drug discovery when the disease biology is well-understood, allowing for a more direct path to drug optimization, as compounds are optimized for specific parameters like binding affinity and selectivity from the outset [2].

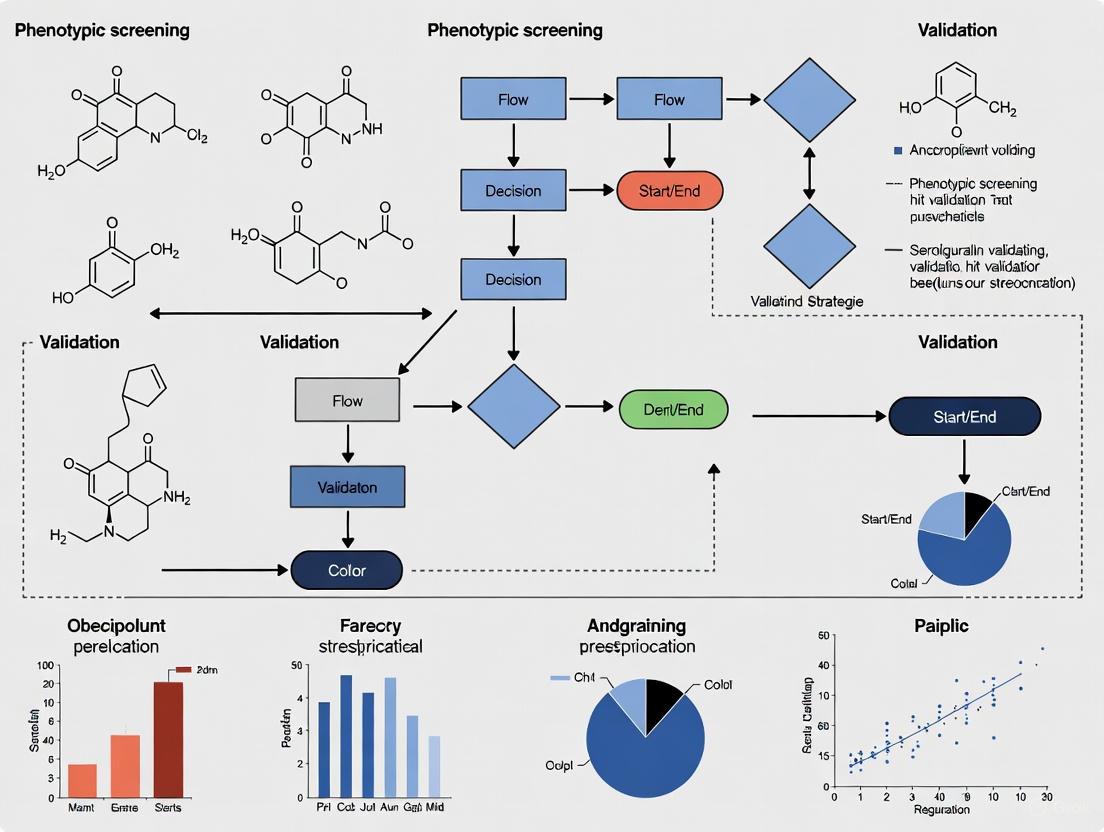

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflow differences between these two strategies.

Quantitative Performance and Success Metrics

A critical metric for comparing these approaches is their historical output of first-in-class medicines. Analysis of new FDA-approved treatments reveals that phenotypic screening has been a significant source of innovative therapies.

Table 1: New Therapies from Different Discovery Strategies (1999-2017) [3]

| Discovery Strategy | Number of Approved Drugs (1999-2017) |

|---|---|

| Phenotypic Drug Discovery | 58 |

| Target-Based Drug Discovery | 44 |

| Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Therapies | 29 |

Furthermore, specific therapeutic areas have been particularly enriched by phenotypic screening, leading to breakthrough medicines for diseases with previously unmet needs.

Table 2: Recent Therapies Originating from Phenotypic Screens [1] [3]

| Drug (Brand Name) | Disease Indication | Year Approved | Key Target/Mechanism Elucidated Post-Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risdiplam (Evrysdi) | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | 2020 | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modifier |

| Vamorolone (Agamree) | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | 2023 | Dissociative mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| Daclatasvir (Daklinza) | Hepatitis C (HCV) | 2014 | NS5A protein inhibitor |

| Lumacaftor (in Orkambi) | Cystic Fibrosis | 2015 | CFTR protein corrector |

| Perampanel (Fycompa) | Epilepsy | 2012 | AMPA glutamate receptor antagonist |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for a High-Content Phenotypic Screen

High-content imaging is a powerful modality for phenotypic screening, enabling multi-parametric analysis of compound effects [4]. The following protocol outlines a typical workflow for identifying hit compounds using a live-cell reporter system.

- Step 1: Reporter Cell Line Construction. Generate a triply-labeled live-cell reporter cell line. A common configuration includes:

- pSeg Plasmid: Demarcates the whole cell (e.g., mCherry fluorescent protein) and nucleus (e.g., Histone H2B fused to cyan fluorescent protein) for automated image segmentation.

- CD-tagged Gene: A full-length protein of interest is labeled with a fluorescent protein (e.g., YFP) via Central Dogma (CD)-tagging, serving as a biomarker for cellular responses [4].

- Step 2: Assay Setup and Compound Treatment. Plate the reporter cells and treat with a library of compounds, typically for 24-48 hours, alongside DMSO vehicle controls. Include known drugs as benchmark controls for relevant phenotypic classes.

- Step 3: Image Acquisition and Feature Extraction. Acquire microscopy images at multiple time points. For each cell in the population, extract ~200 features related to morphology (e.g., nuclear and cellular shape) and protein expression (e.g., intensity, localization, texture) [4].

- Step 4: Phenotypic Profiling. Transform the feature distributions into quantitative phenotypic profiles.

- For each feature, calculate the difference between the cumulative distribution functions (CDF) of compound-treated and untreated (DMSO) cells using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic.

- Concatenate the KS scores across all features to form a single phenotypic profile vector for each compound [4].

- Step 5: Hit Identification and Classification. Use similarity metrics (e.g., cosine similarity) to compare the phenotypic profiles of test compounds to those of benchmark drugs. Compounds that cluster with known active drugs are classified as hits, suggesting a similar functional effect or mechanism of action.

Protocol for a Target-Based Screen

Target-based screens are typically biochemical and configured for high-throughput.

- Step 1: Target and Assay Selection. Select a purified protein target (e.g., an enzyme, receptor) and develop a robust biochemical assay. Common formats include fluorescence polarization (FP), time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET), or absorbance-based enzyme activity assays.

- Step 2: High-Throughput Screening (HTS). Screen a diverse compound library against the target in a microtiter plate format. The assay measures a direct biochemical output, such as enzyme inhibition or receptor-ligand displacement.

- Step 3: Hit Identification. Calculate the percentage inhibition or binding affinity (IC50/Ki) for each compound. Hits are typically defined as compounds that exceed a predefined activity threshold (e.g., >50% inhibition at 10 µM) and are confirmed in dose-response experiments.

- Step 4: Counter-Screening. Test hits against related but unintended targets to assess selectivity and against the assay technology itself to rule out artifacts (e.g., fluorescence interference, compound aggregation).

Protocol for Integrated Target Deconvolution

A major challenge in phenotypic screening is identifying the molecular target of a hit compound. The following integrated protocol, combining knowledge graphs with molecular docking, exemplifies a modern approach [5].

- Step 1: Construct a Protein-Protein Interaction Knowledge Graph (PPIKG). Build a large-scale knowledge graph incorporating proteins, their interactions, and associated pathways relevant to the disease phenotype under study. For example, a p53-focused PPIKG would include all known direct interactors and regulators.

- Step 2: Candidate Target Prioritization. Using the hit compound's phenotypic profile, query the PPIKG to identify potential protein targets within the relevant biological network. This step leverages link prediction algorithms to narrow the candidate pool from thousands to a more manageable number (e.g., from 1088 to 35 proteins) [5].

- Step 3: In Silico Molecular Docking. Perform computational docking of the hit compound against the shortlisted candidate protein targets. This predicts the binding pose and affinity, helping to pinpoint the most likely direct target(s).

- Step 4: Experimental Validation. Validate the top predicted target(s) using orthogonal biochemical and cellular assays, such as:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) to confirm direct binding.

- Gene Knockdown (siRNA/CRISPR) to see if it phenocopies the drug effect.

- Functional Assays to demonstrate that target engagement leads to the expected biological outcome.

The workflow for this integrated deconvolution method is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of both screening paradigms relies on specialized reagents, tools, and databases.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Screening and Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Screening | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [6] | Bioactivity Database | Provides curated data on bioactive molecules, their targets, and interactions. | Serves as a reference database for ligand-centric target prediction and model training. |

| CD-Tagging [4] | Genetic Engineering Tool | Endogenously labels full-length proteins with a fluorescent tag (e.g., YFP) in reporter cell lines. | Creates biomarkers for live-cell imaging in high-content phenotypic screens. |

| pSeg Plasmid [4] | Fluorescent Reporter | Expresses distinct fluorescent markers for the nucleus and cytoplasm. | Enables automated cell segmentation and morphological feature extraction in imaging assays. |

| Cell Painting Assay | Phenotypic Profiling | A multiplexed staining method using up to 6 fluorescent dyes to reveal various cellular components. | Generates rich, high-content morphological profiles for mechanism of action studies. |

| Knowledge Graph (e.g., PPIKG) [5] | Computational Framework | Represents biological knowledge as interconnected entities (proteins, drugs, diseases). | Prioritizes candidate drug targets by inferring links within complex biological networks. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Computational Tool | Predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule when bound to a protein target. | Virtually screens and assesses the binding feasibility of a hit compound to a list of candidate targets. |

Phenotypic and target-based screening are complementary, not competing, strategies in the drug discovery arsenal. Phenotypic screening excels at identifying first-in-class drugs with novel mechanisms, expanding the "druggable" target space, and addressing complex, polygenic diseases [1]. Its primary challenges are the complexity of assay development and the subsequent need for target deconvolution. Target-based screening offers a more direct, mechanistically driven path for well-validated targets, streamlining lead optimization but potentially missing complex biology and synergistic polypharmacology [2]. The future of efficient drug discovery lies in the strategic integration of both approaches, leveraging the strengths of each to increase the probability of delivering new medicines to patients.

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD), once considered a legacy approach, has experienced a major resurgence over the past decade following a surprising observation: between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered empirically without a predefined drug target hypothesis [1]. This revelation prompted a fundamental re-evaluation of drug discovery strategy, leading to the systematic pursuit of therapeutic agents based on their effects on realistic disease models rather than modulation of specific molecular targets [1]. Modern PDD represents the original concept of observing therapeutic effects on disease physiology augmented with contemporary tools and strategies, creating a powerful discovery modality that has begun to yield notable clinical successes [1].

The molecular biology revolution of the 1980s and the subsequent sequencing of the human genome prompted a significant shift toward target-based drug discovery (TDD), a more reductionist approach focused on specific molecular targets of interest [1]. However, the limitations of this strategy in addressing the complex, polygenic nature of many diseases have become increasingly apparent, creating an opportunity for PDD to re-establish itself as a complementary and valuable approach [7]. This article examines the renewed prominence of PDD, analyzing its distinctive strengths and challenges while providing a comparative assessment of its performance against target-based approaches in delivering first-in-class therapies.

PDD vs. TDD: A Strategic Comparison

The fundamental distinction between Phenotypic Drug Discovery and Target-Based Drug Discovery lies in their starting points and underlying philosophies. TDD begins with a hypothesis about a specific molecular target's role in disease pathogenesis, while PDD initiates with a disease-relevant biological system and identifies compounds that modulate a disease phenotype without requiring prior knowledge of the drug's mechanism of action [1] [7]. This distinction creates significant ramifications throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from screening strategies to hit validation approaches.

Table 1: Key Strategic Differences Between PDD and TDD Approaches

| Parameter | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease phenotype or biomarker in realistic model systems [1] | Specific molecular target with hypothesized disease relevance [7] |

| Knowledge Requirement | No requirement for identified molecular target or hypothesis about its role [7] | Established causal relationship between target and disease state [1] |

| Primary Screening Output | Compounds that modulate disease-relevant phenotypes [8] | Compounds that modulate specific target activity [7] |

| Target Identification | Required after compound identification (target deconvolution) [7] | Defined before compound screening [1] |

| Strength | Expands "druggable" target space; identifies novel mechanisms [1] | Straightforward optimization; clear biomarker strategy [8] |

| Challenge | Complex hit validation; resource-intensive target identification [8] [7] | Limited to known biology; may miss complex disease mechanisms [1] |

The track record of PDD in delivering first-in-class therapies is particularly noteworthy. Analysis reveals that PDD approaches have disproportionately contributed to innovative medicines, frequently identifying unprecedented mechanisms of action and novel biological pathways [1]. Successful examples include ivacaftor and lumacaftor for cystic fibrosis, risdiplam and branaplam for spinal muscular atrophy, and lenalidomide for multiple myeloma, all originating from phenotypic screens [1].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in PDD Success

Cystic Fibrosis: Correcting Cellular Trafficking

Cystic fibrosis (CF) stems from mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that disrupt CFTR protein folding, trafficking, and function [1]. Target-agnostic compound screens using cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants identified compounds that improved CFTR channel gating (potentiators such as ivacaftor) and others with an unexpected mechanism: enhancing CFTR folding and plasma membrane insertion (correctors such as tezacaftor and elexacaftor) [1]. The combination therapy elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor, approved in 2019, addresses 90% of the CF patient population and exemplifies how phenotypic strategies can identify unexpected mechanisms that would have been difficult to predict using target-based approaches [1].

Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Modulating Splicing Machinery

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SMN1 gene [1]. Humans possess a closely related SMN2 gene, but a splicing mutation leads to exclusion of exon 7 and production of an unstable SMN variant. Phenotypic screens identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase production of full-length functional SMN protein [1]. These compounds function through an unprecedented mechanism: they bind two sites at the SMN2 exon 7 and stabilize the U1 snRNP complex [1]. The resulting drug, risdiplam, approved in 2020, represents the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA and demonstrates how PDD can reveal novel therapeutic mechanisms involving fundamental cellular processes like RNA splicing [1].

Hepatitis C: Targeting Non-Enzymatic Viral Proteins

The treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was revolutionized by direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), with NS5A modulators such as daclatasvir becoming key components of combination therapies [1]. Notably, NS5A is essential for HCV replication but lacks known enzymatic activity, making it an unlikely candidate for traditional target-based approaches [1]. The importance of NS5A as a drug target was initially discovered using an HCV replicon phenotypic screen, highlighting PDD's ability to identify chemically tractable targets that would be overlooked by conventional target-based strategies [1].

Table 2: Notable First-in-Class Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Drug | Therapeutic Area | Molecular Target/Mechanism | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risdiplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulator [1] | First oral therapy; novel splicing mechanism [1] |

| Ivacaftor/Lumacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR potentiator/corrector [1] | Addresses protein misfolding; novel mechanism [1] |

| Lenalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulator [1] | Targeted protein degradation; novel MoA [1] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A inhibitor [1] | Targets protein without enzymatic activity [1] |

| SEP-363856 | Schizophrenia | Unknown (TAAR1 agonist suspected) [1] | Novel non-D2 mechanism for schizophrenia [1] |

Methodological Framework: PDD Experimental Protocols

Phenotypic Screening and Hit Triage Workflow

The PDD process involves a series of methodical steps from assay development through hit validation, each with specific technical requirements and decision points. The workflow can be visualized as a multi-stage funnel with progressively stringent criteria.

The hit triage and validation phase represents a critical juncture in PDD. Successful navigation of this stage is enabled by three types of biological knowledge: known mechanisms, disease biology, and safety considerations [8]. Interestingly, evidence suggests that structure-based hit triage at this stage may be counterproductive, as it potentially eliminates compounds with novel mechanisms of action [8].

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

Implementation of robust phenotypic screening requires specialized research reagents and tools designed to capture relevant disease biology while enabling high-throughput capabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in PDD |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Models | Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [7] | Patient-derived disease modeling; improved clinical translatability [7] |

| Complex Co-culture Systems | Organoids, 3D culture systems [7] | Recapitulate tissue-level complexity and cell-cell interactions [7] |

| Biosensors | Calcium flux dyes, voltage-sensitive dyes [1] | Monitor functional responses in real-time kinetic assays [1] |

| Gene Expression Tools | Connectivity Map, LINCS [7] | Compare compound signatures to reference databases; mechanism prediction [7] |

| Functional Genomics Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 screens [7] | Target identification and validation; pathway analysis [7] |

| High-Content Imaging Reagents | Multiplexed fluorescent dyes, antibodies [8] | Multi-parameter phenotypic assessment at single-cell resolution [8] |

Mechanism of Action and Polypharmacology in PDD

A distinctive feature of PDD is its capacity to identify compounds with unexpected mechanisms of action, significantly expanding the conventional "druggable" target space [1]. Phenotypic approaches have revealed novel therapeutic mechanisms involving diverse cellular processes including pre-mRNA splicing, protein folding, intracellular trafficking, and targeted protein degradation [1]. The case of lenalidomide exemplifies this phenomenon: while clinically effective in multiple myeloma, its unprecedented molecular mechanism—redirecting the substrate specificity of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cereblon—was only elucidated several years post-approval [1].

PDD also naturally accommodates polypharmacology, where a compound's therapeutic effect depends on simultaneous modulation of multiple targets [1]. While traditionally viewed as undesirable due to potential side effects, strategic polypharmacology may be particularly valuable for complex, polygenic diseases with multiple underlying pathological mechanisms [1]. Phenotypic approaches enable identification of such multi-target agents without preconceived notions about which target combinations might be most efficacious.

Challenges and Future Directions in Phenotypic Screening

Despite its promise, PDD faces considerable challenges that must be addressed to fully realize its potential. Target deconvolution—identifying the molecular mechanism of action of phenotypic hits—remains resource-intensive and technically challenging [7]. Furthermore, developing physiologically relevant yet scalable disease models requires careful balancing of complexity with practicality [1] [7]. There are also ongoing difficulties in establishing robust structure-activity relationships without target knowledge, potentially complicating lead optimization [7].

Future progress in PDD will likely be driven by advances in several key areas. Improved disease models, particularly patient-derived organoids and complex co-culture systems, will enhance physiological relevance [7]. Computational approaches, including machine learning and artificial intelligence, are increasingly being applied to analyze complex phenotypic data and predict mechanisms of action [1] [9]. Functional genomics tools such as CRISPR screening continue to accelerate target identification [7]. Finally, systematic approaches to hit triage that leverage biological knowledge while avoiding premature elimination of novel mechanisms will be essential [8].

The resurgence of Phenotypic Drug Discovery represents not a return to tradition but rather the evolution of a powerful approach enhanced by modern tools and strategic insights. The demonstrated capacity of PDD to deliver first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action justifies its position as a valuable discovery modality alongside target-based approaches [1] [7]. The most productive path forward likely involves strategic selection of the optimal approach based on specific project requirements: target-based strategies when the disease biology and therapeutic hypothesis are well-defined, and phenotypic approaches when exploring novel biology or addressing complex, polygenic diseases [1].

As technological advances continue to address current challenges in hit validation and target deconvolution, PDD is poised to contribute significantly to the next generation of innovative medicines. By embracing both phenotypic and target-based strategies as complementary tools, the drug discovery community can maximize its potential to address unmet medical needs through diverse therapeutic mechanisms.

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD), which identifies active compounds based on their effects in disease-relevant biological systems without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target, has proven highly successful for generating first-in-class medicines [10] [1]. However, this target-agnostic strength also presents a significant challenge: the initial "hits" emerging from primary screens may include numerous false positives resulting from assay interference rather than genuine biological activity [11]. In complex biological systems, these artifacts can arise from various mechanisms, including compound aggregation, chemical reactivity, fluorescence interference, and cytotoxicity [11] [12]. The hit validation imperative therefore demands a systematic, multi-faceted approach to distinguish true bioactive compounds from assay artifacts, ensuring that resources are invested only in the most promising leads with genuine therapeutic potential.

The consequences of inadequate hit validation are severe, often leading to wasted resources on compounds that ultimately fail in later development stages due to off-target activity, lack of cellular efficacy, or unacceptable toxicity profiles [13]. Modern drug discovery has shifted toward more rigorous and physiologically relevant validation strategies that balance throughput with translational fidelity, incorporating direct evidence of intracellular target engagement and biologically meaningful phenotypic responses [13]. This guide examines the experimental strategies and methodologies essential for confident hit validation in phenotypic screening campaigns, providing researchers with a framework for mitigating risks in complex biological systems.

Core Strategies for Hit Triage and Validation

Following primary phenotypic screening, hit validation employs a cascade of computational and experimental approaches to select the most promising compounds for further development [11]. This triage process systematically eliminates artifacts while scoring compounds based on their activity, specificity, and potential for optimization.

Computational Triage Approaches

Before embarking on resource-intensive experimental validation, computational filters provide an efficient first pass for prioritizing chemically tractable hits and flagging potential troublemakers:

- Frequent-Hitter Identification: Analysis of historical screening data can flag compounds with promiscuous activity across multiple unrelated assays, suggesting general assay interference rather than specific biological activity [11].

- Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) Filtering: Structural filters identify chemotypes known to cause assay interference through mechanisms such as redox cycling, protein aggregation, or fluorescence [11] [12].

- Drug-Likeness and Property Calculations: Assessment of physicochemical properties (molecular weight, lipophilicity, polar surface area) helps prioritize compounds with favorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics [12].

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: Early examination of SAR within hit clusters can distinguish genuine bioactivity from assay interference, though caution is needed as interfering compounds can sometimes display convincing SAR (structure-interference relationship) [11].

Experimental Validation Strategies

Experimental hit validation employs three principal strategies—counter, orthogonal, and cellular fitness assays—conducted in parallel or consecutively to build confidence in hit quality [11].

Table 1: Experimental Strategies for Hit Validation

| Strategy | Purpose | Key Assay Types | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Counter Screens | Identify and eliminate false positives from assay technology interference | Reporter enzyme assays, autofluorescence/quenching tests, affinity tag exchange | Specificity of hit compounds; identification of technology-based artifacts [11] |

| Orthogonal Assays | Confirm bioactivity using different readout technologies or conditions | Biophysical assays (SPR, ITC, MST), high-content imaging, different cell models | Confirmation of biological activity; affinity data; single-cell vs population effects [11] [12] |

| Cellular Fitness Assays | Exclude compounds with general toxicity | Viability assays (CellTiter-Glo, MTT), cytotoxicity assays (LDH, CellTox Green), apoptosis assays | Impact on cellular health; therapeutic window estimation [11] |

Counter screens are specifically designed to assess hit specificity and eliminate false positives arising from assay technology interference [11]. These assays bypass the actual biological reaction or interaction to focus solely on the compound's effect on the detection technology itself. Examples include testing for autofluorescence, signal quenching or enhancement, singlet oxygen quenching, light scattering, and reporter enzyme modulation [11]. In cell-based assays, counter screens may involve absorbance and emission tests in control cells, while buffer condition modifications (e.g., adding BSA or detergents) can help counteract unspecific binding or aggregation [11].

Orthogonal assays confirm compound bioactivity using different readout technologies or assay conditions than those employed in the primary screen [11] [12]. These assays analyze the same biological outcome but use independent detection methods, providing crucial validation of initial findings. For example, fluorescence-based primary readouts can be validated with luminescence- or absorbance-based follow-up analyses [11]. In phenotypic screening, orthogonal validation might involve using different cell models (2D vs. 3D cultures, fixed vs. live cells) or disease-relevant primary cells to confirm activity in biologically relevant settings [11].

Cellular fitness assays determine whether hit compounds exhibit general toxicity or harm to cells, which is critical for classifying bioactive molecules that maintain global nontoxicity in a cellular context [11]. These assays can employ bulk readouts representing population-level health (e.g., CellTiter-Glo for viability, LDH assays for cytotoxicity) or high-content, image-based techniques that provide single-cell resolution [11]. The cell painting assay—a high-content morphological profiling approach using multiplexed fluorescent staining—offers particularly comprehensive assessment of cellular states following compound treatment, enabling prediction and identification of compound-mediated cellular toxicity [11].

Figure 1: Comprehensive hit validation workflow integrating computational and experimental approaches to identify high-quality hits from phenotypic screening.

Biophysical Methods for Target Engagement Validation

Biophysical assays provide direct evidence of compound-target interactions, serving as powerful orthogonal approaches in hit validation cascades [11] [12]. These methods are particularly valuable for confirming that hits identified in phenotypic screens engage their intended targets, even when those targets were unknown during the initial screening phase.

Table 2: Biophysical Methods for Hit Validation

| Method | Principle | Information Provided | Throughput | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures binding-induced refractive index changes on a sensor surface | Binding affinity (KD), kinetics (kon, koff), stoichiometry | Medium | Medium purity and stability [11] [12] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Measures heat changes during binding | Binding affinity, stoichiometry, thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS) | Low | High purity and solubility [12] |

| Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) | Measures directed movement of molecules in temperature gradients | Binding affinity, apparent KD | Medium | Low sample consumption, tolerates impurities [11] |

| Thermal Shift Assay (TSA) | Measures protein thermal stabilization upon ligand binding | Binding confirmation, apparent KD | Medium-High | Low sample consumption [11] [12] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Detects changes in nuclear spin properties upon binding | Binding confirmation, binding site identification, affinity | Low | High purity, isotopic labeling often required [12] |

Among these methods, the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as particularly valuable for phenotypic screening hit validation, as it enables direct, label-free quantification of compound-target interactions in physiologically relevant environments [13]. Unlike conventional biophysical methods that use purified proteins, CETSA works in intact cells under native conditions, preserving the cellular context and confirming that hits can engage their targets in a biologically relevant system [13]. This approach directly addresses the critical question of intracellular target engagement, helping triage hits that appear promising in biochemical assays but fail to penetrate cells or engage their targets in a cellular environment.

Successful Hit Validation: Case Studies

Several approved therapeutics discovered through phenotypic screening illustrate the importance of rigorous hit validation in delivering clinically effective medicines:

CFTR Modulators for Cystic Fibrosis

Target-agnostic compound screens using cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants identified both potentiators (ivacaftor) that improve channel gating and correctors (tezacaftor, elexacaftor) that enhance CFTR folding and membrane insertion [1]. The triple combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor, approved in 2019, addresses 90% of the CF patient population [1]. This success required extensive hit validation to distinguish true CFTR modulators from assay artifacts and to optimize combinations that provide clinical benefit through complementary mechanisms of action.

SMN2 Splicing Modulators for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Phenotypic screens identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase full-length SMN protein levels [1]. Rigorous validation confirmed that these compounds engage two sites at the SMN2 exon 7 region to stabilize the U1 snRNP complex—an unprecedented drug target and mechanism of action [1]. The resulting drug, risdiplam, received FDA approval in 2020 as the first oral disease-modifying therapy for spinal muscular atrophy, demonstrating how thorough hit validation can reveal novel biological mechanisms with therapeutic potential.

Immunomodulatory Drugs

Phenotypic screening of thalidomide analogs led to the discovery of lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which exhibited significantly increased potency for downregulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production with reduced side effects [10]. Subsequent target deconvolution efforts identified cereblon as the primary binding target, revealing that these compounds alter the substrate specificity of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to degradation of specific transcription factors [10]. This novel mechanism, validated through extensive follow-up studies, now forms the basis for targeted protein degradation strategies using proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Hit Validation

Implementing a comprehensive hit validation strategy requires specialized reagents and tools designed to address specific validation challenges in phenotypic screening:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hit Validation

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Key Applications in Hit Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Viability Assays (CellTiter-Glo, MTT) | Measure metabolic activity as proxy for cell health | Cellular fitness screening; toxicity assessment [11] |

| Cytotoxicity Assays (LDH assay, CytoTox-Glo, CellTox Green) | Detect membrane integrity compromise | Cellular fitness screening; therapeutic index estimation [11] |

| Apoptosis Assays (Caspase assays) | Measure programmed cell death activation | Cellular fitness screening; mechanism of action studies [11] |

| High-Content Staining Reagents (DAPI, Hoechst, MitoTracker, TMRM/TMRE) | Label specific cellular compartments | High-content cellular fitness analysis; morphological profiling [11] |

| Cell Painting Kits | Multiplexed fluorescent staining of cellular components | Comprehensive morphological profiling; toxicity prediction [11] |

| CETSA Reagents | Enable thermal shift assays in cellular contexts | Intracellular target engagement confirmation [13] |

| Affinity Capture Reagents (His-tag, StrepTagII resins) | Purify or detect tagged proteins | Counter screens for affinity capture interference [11] |

The hit validation imperative in phenotypic screening demands a systematic, multi-layered approach that integrates computational triage with experimental validation through counter, orthogonal, and cellular fitness assays [11]. By implementing this comprehensive framework, researchers can significantly reduce false positives, identify compounds with genuine therapeutic potential, and de-risk downstream development efforts. The successful application of these strategies in discovering transformative medicines for cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and multiple myeloma demonstrates their critical importance in modern drug discovery [10] [1].

As phenotypic screening continues to evolve, incorporating more complex disease models and advanced readout technologies, hit validation strategies must similarly advance to address new challenges and opportunities. The integration of direct target engagement methods like CETSA [13], high-content morphological profiling [11], and artificial intelligence-driven pattern recognition [10] promises to further enhance our ability to distinguish high-quality hits from artifacts. Through rigorous application of these validation principles, researchers can confidently advance the most promising compounds from phenotypic screens, accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients.

Phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful strategy in modern drug discovery, enabling the identification of novel therapeutics based on their observable effects on cellular or organismal phenotypes rather than interactions with a predefined molecular target [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for uncovering first-in-class therapies and addressing diseases with complex or poorly understood biology. However, the path from identifying a active compound (a "hit") in a phenotypic screen to validating it as a true lead candidate is fraught with challenges that stem from two primary sources: assay artifacts that can produce misleading results, and the complex process of target deconvolution to identify the mechanism of action.

The fundamental difference between target-based and phenotypic screening approaches necessitates distinct validation strategies. While target-based screening hits act through known mechanisms, phenotypic screening hits operate within a large and often poorly understood biological space, requiring specialized triage and validation processes [8]. Successful navigation of this process is critical for translating initial screening hits into viable clinical candidates and requires integrating multiple types of biological knowledge—including known mechanisms, disease biology, and safety considerations.

Understanding and Mitigating Assay Artifacts

Assay artifacts represent non-biological signals that can masquerade as genuine phenotypic effects, potentially leading researchers down unproductive pathways. These artifacts can arise from various sources:

- Compound-mediated interference: Some compounds can interfere with assay detection systems through fluorescence, quenching, or light scattering properties.

- Cytotoxicity effects: Non-specific cellular toxicity can produce apparent phenotypic changes that are not related to the intended biological mechanism.

- Solvent effects: The vehicles used to dissolve compounds (e.g., DMSO) can sometimes themselves influence cellular phenotypes at high concentrations.

- Edge effects: Physical phenomena in microtiter plates, such as evaporation or temperature gradients, can create spatial patterns of response.

- Off-target activities: Compounds may interact with unexpected biological targets, producing phenotypic changes unrelated to the disease biology of interest.

The challenge of artifacts is particularly pronounced in high-throughput screening environments where thousands of compounds are tested simultaneously. Without proper controls and counter-screens, these artifacts can significantly compromise screening outcomes and waste valuable resources on follow-up activities.

Strategies for Artifact Mitigation

Several established strategies can help identify and mitigate the impact of assay artifacts:

- Including appropriate controls: Positive and negative controls should be included across multiple plates and time points to monitor assay performance and stability.

- Implementing orthogonal assays: Confirming hits using different detection technologies or assay formats can help eliminate technology-specific artifacts.

- Applying counter-screens: Specific assays designed to detect common interference mechanisms (e.g., fluorescence at relevant wavelengths) should be employed.

- Analyzing structure-activity relationships (SAR): The relationship between chemical structure and observed activity can help distinguish true biological effects from artifacts.

- Employing dose-response characterization: True biological effects typically show concentration dependence, while some artifacts may not.

Recent research suggests that strict filtering with counter-screens might sometimes be more detrimental than beneficial in identifying true positives, as overly aggressive filtering could eliminate valid hits with unusual properties [15]. Therefore, a balanced approach that combines rigorous artifact detection with thoughtful hit prioritization is essential.

Table 1: Common Assay Artifacts and Detection Methods

| Artifact Type | Common Causes | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Fluorescence | Intrinsic fluorophores, impurities | Fluorescence counter-screens, lifetime measurements |

| Chemical Quenching | Light absorption, energy transfer | Orthogonal detection methods, label-free approaches |

| Solvent Toxicity | High DMSO concentrations, solvents | Vehicle controls, solubility assessment |

| Off-target Effects | Polypharmacology, promiscuous binders | Selectivity panels, proteomic profiling |

| Cytotoxicity | Non-specific cell death | Viability assays, multiparametric readouts |

Target Deconvolution Strategies and Methodologies

The Role of Target Deconvolution in Phenotypic Screening

Target deconvolution refers to the process of identifying the molecular target or targets of a chemical compound discovered through phenotypic screening [16]. This process represents a critical bridge between initial hit identification and downstream optimization efforts in the drug discovery pipeline. By elucidating the mechanism of action (MOA) of phenotypic hits, researchers can:

- Assess the novelty and potential intellectual property position of the compound

- Guide medicinal chemistry efforts for optimization

- Predict potential safety liabilities based on target biology

- Identify biomarkers for patient stratification or efficacy monitoring

- Understand structure-activity relationships in the context of the target

The importance of target deconvolution has grown alongside the resurgence of phenotypic screening, as the pharmaceutical industry seeks to balance the innovation potential of phenotypic approaches with the need for mechanistic understanding.

Key Methodologies for Target Deconvolution

Affinity-Based Chemoproteomics

Affinity-based pull-down represents a foundational approach for target deconvolution. This method involves:

- Probe Design: The compound of interest is modified with a linker or handle that enables immobilization without disrupting its biological activity.

- Target Capture: The immobilized "bait" compound is incubated with cell lysates or living cells to allow binding to cellular targets.

- Protein Isolation: Bound proteins are isolated through affinity enrichment using the immobilization handle.

- Target Identification: Captured proteins are identified using mass spectrometry-based proteomics.

This approach works well for a wide range of target classes and can provide dose-response and binding affinity information (e.g., IC50 values) when combined with competitive binding experiments [16]. The key challenge lies in designing a chemical probe that maintains the activity and binding properties of the original hit compound.

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP)

Activity-based protein profiling utilizes bifunctional probes containing both a reactive group and a reporter tag to covalently label functional sites in proteins. Two main variations exist:

- Direct ABPP: An electrophilic compound of interest is functionalized with a reporter tag, allowing direct identification of its binding targets.

- Competitive ABPP: Samples are treated with a broad-spectrum activity-based probe with and without the compound of interest; targets are identified as proteins whose labeling is reduced by compound competition.

This approach is particularly powerful for studying enzymes with nucleophilic active sites and can provide information on the functional state of protein families [16]. However, it requires the presence of reactive residues in accessible regions of the target protein.

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL)

Photoaffinity labeling employs trifunctional probes containing the compound of interest, a photoreactive group, and an enrichment handle. The method proceeds through:

- Binding: The probe is allowed to bind to its cellular targets under physiological conditions.

- Cross-linking: UV irradiation activates the photoreactive group, forming covalent bonds with nearby target proteins.

- Enrichment and Identification: Cross-linked proteins are isolated using the handle and identified by mass spectrometry.

PAL is particularly valuable for identifying membrane protein targets and capturing transient compound-protein interactions that might be missed by other methods [16]. The technique requires careful optimization of photoreactive group placement and irradiation conditions.

Label-Free Approaches

Label-free target deconvolution strategies have emerged as powerful alternatives that avoid potential perturbations caused by compound modification. One prominent example is:

Solvent-Induced Denaturation Shift Assays: These methods leverage the changes in protein stability that typically occur upon ligand binding. By comparing the kinetics of physical or chemical denaturation in the presence and absence of compound, researchers can identify target proteins on a proteome-wide scale without modifying the compound of interest [16].

This approach is particularly valuable for studying compound-protein interactions under native physiological conditions, though it can be challenging for low-abundance proteins, very large proteins, and membrane proteins.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Target Deconvolution Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Pull-down | Immobilized bait captures binding partners | Works for diverse targets, provides affinity data | Requires high-affinity probe, immobilization may affect binding | Soluble proteins, abundant targets |

| Activity-Based Profiling | Covalent labeling of active sites | High sensitivity, functional information | Limited to proteins with reactive residues | Enzyme families, catalytic sites |

| Photoaffinity Labeling | Photocrosslinking of protein-compound complexes | Captures transient interactions, works for membrane proteins | Complex probe design, potential non-specific crosslinking | Membrane proteins, weak interactions |

| Label-Free Methods | Detection of stability changes upon binding | No compound modification needed, native conditions | Challenging for low-abundance proteins | Soluble targets, stable complexes |

Experimental Design and Workflows

Integrated Hit Validation Workflow

A robust workflow for phenotypic screening hit validation incorporates multiple orthogonal approaches to address both artifact elimination and target deconvolution. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive strategy:

Diagram 1: Hit validation workflow from phenotypic screening

Compressed Screening for Enhanced Efficiency

Recent advances in screening methodology have introduced innovative approaches to increase the efficiency of phenotypic screening. Compressed screening utilizes pooled perturbations followed by computational deconvolution to reduce sample requirements, labor, and cost while maintaining information-rich readouts [17].

The fundamental approach involves:

- Combining N perturbations into unique pools of size P

- Ensuring each perturbation appears in R distinct pools overall

- Using computational deconvolution based on regularized linear regression and permutation testing to infer individual perturbation effects

This method enables P-fold compression, substantially reducing resource requirements while maintaining the ability to identify hits with large effects. Benchmarking studies using a 316-compound FDA drug repurposing library and high-content imaging readouts demonstrated that compressed screening consistently identified compounds with the largest ground-truth effects across a wide range of pool sizes (3-80 drugs per pool) [17].

Phenotypic Screening for Ultra-rare Disorders

Phenotypic screening coupled with drug repurposing has emerged as a particularly valuable strategy for addressing ultra-rare disorders. This approach leverages several key principles [14]:

- Use of patient-derived primary cells: Skin fibroblasts from patients provide a biologically relevant system that maintains the disease phenotype.

- Avoidance of artificial stimuli: Systems that don't rely on exogenous stimuli to induce the disease phenotype are preferred.

- Clinically relevant readouts: Assay endpoints should mirror disease endpoints, such as toxic metabolite accumulation.

This strategy has been successfully applied to inherited metabolic disorders, where phenotypic screening in patient fibroblasts using mass spectrometry-based detection of disease-relevant metabolites has identified potential repurposing candidates [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

Successful implementation of phenotypic screening and hit validation requires carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-derived primary cells | Biologically relevant disease modeling | Studying inherited metabolic disorders [14] |

| Cell Painting assays | Multiparametric morphological profiling | High-content screening using fluorescent dyes [17] |

| Affinity enrichment matrices | Immobilization of bait compounds | Target pull-down experiments [16] |

| Photoactivatable probes | Covalent crosslinking for target identification | Photoaffinity labeling studies [16] |

| Activity-based probes | Profiling of functional protein states | Competitive ABPP experiments [16] |

| Mass spectrometry standards | Quantitative proteomics | Protein identification and quantification |

| Multiplexed imaging panels | Spatial proteomics and transcriptomics | Cell type identification in complex tissues [18] |

Case Studies and Data Analysis

SARS-CoV-2 Antiviral Screening

A comprehensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2 drug discovery campaigns provides valuable insights into assay selection and hit validation strategies. Research comparing different high-throughput screening approaches revealed that:

- Multitarget assays showed advantages in terms of accuracy and efficiency over single-target assays for identifying potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 compounds [15].

- Target-specific assays were more suitable for investigating compound mechanisms of action once hits were identified.

- The hit rates of multitarget assays (31-46%) were approximately one order of magnitude higher than that of single-target assays (5-6%) and phenotypic cytopathic effect assays (8%) [15].

This case study highlights the importance of selecting appropriate assay formats based on the screening objectives, with multitarget approaches providing advantages for initial hit identification.

Performance Benchmarking of Computational Methods

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating the performance of computational tools used in hit validation and deconvolution. A recent multi-assay study of cellular deconvolution methods for brain tissue analysis demonstrated that:

- Bisque and hspe were the most accurate methods for estimating cell type proportions from bulk RNA-seq data using single nucleus RNA-seq reference data [19].

- Performance variations across methods highlighted the impact of algorithm selection on result quality.

- The availability of orthogonal measurements of cell type proportions (e.g., via RNAScope/Immunofluorescence) was critical for proper method evaluation [19].

These findings underscore the importance of method selection and validation for computational approaches used in target deconvolution and hit validation.

Navigating the path from phenotypic screening hits to validated leads requires carefully balancing multiple considerations. Assay artifacts must be identified and eliminated without being so aggressive as to discard valuable true positives. Target deconvolution strategies must be selected based on the specific compound properties and biological context. Emerging approaches such as compressed screening and label-free deconvolution methods offer promising avenues for increasing efficiency and physiological relevance.

The future of phenotypic screening hit validation will likely involve even greater integration of orthogonal approaches, combining chemical biology, proteomics, genomics, and computational methods to build confidence in screening hits while accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will expand the scope of diseases that can be addressed through phenotypic screening, particularly for complex disorders and rare diseases with significant unmet medical needs.

A Multi-Tiered Framework for Hit Confirmation and Triage

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, phenotypic screening has maintained a distinguished track record for delivering first-in-class therapies and revealing novel biology [8]. However, the very nature of this approach—identifying compounds based on functional outcomes without prior knowledge of their molecular targets—introduces significant complexity during the hit evaluation phase. Unlike target-based screening, where mechanisms are predefined, phenotypic screening hits operate within a large and poorly understood biological space, acting through a variety of mostly unknown mechanisms [8]. This fundamental difference necessitates a meticulously designed and robust hit triage process to confidently prioritize compounds for further development. A successful triage strategy must effectively separate true, promising hits from false positives and artifacts, thereby laying a solid foundation for the subsequent arduous journey of target deconvolution and lead optimization. This process is not merely a filter but a critical strategic foundation that determines the long-term viability of a drug discovery campaign.

Key Considerations for a Hit Triage Funnel

Constructing an effective hit triage funnel requires balancing multiple competing priorities: thoroughness, speed, resource allocation, and future-proofing for downstream development. The following considerations are paramount.

- Biological Knowledge over Structural Assumptions: Analysis suggests that successful hit triage and validation is enabled by three types of biological knowledge—known mechanisms, disease biology, and safety profiles. In contrast, over-reliance on structure-based hit triage early in the process may be counterproductive in a phenotypic context, as it could prematurely eliminate compounds with novel mechanisms or suboptimal initial structure [8].

- Robust Assay Development and Statistical Rigor: Identification of active compounds in high-throughput screening (HTS) contexts can be substantially improved by applying classical experimental design and statistical inference principles [20]. This includes the use of robust data preprocessing methods to remove unwanted variation (e.g., row, column, and plate biases) and the incorporation of replicate measurements to estimate the magnitude of random error. Statistical models are then used to benchmark putative hits relative to what is expected by chance [20].

- Integrated Multi-Disciplinary Expertise: Hit triage is not solely a biological endeavor. It requires a broad interplay of disciplines, including reagent production, in vitro biology, medicinal chemistry, and statistical data analysis [21]. A data-driven approach that leverages expertise across these fields is essential for assessing both the biological profile and chemical attractiveness of a hit series.

- The Importance of Orthogonal Validation: A single assay is rarely sufficient to confirm a true hit. Following initial triage, prioritized hit series must be validated through secondary assays that employ orthogonal readouts, such as biophysical methods to confirm on-target binding or more physiologically relevant cell-based assays [21]. This step is crucial for confirming functional response and weeding out assay-specific artifacts.

Essential Triage Criteria and Experimental Protocols

A multi-tiered approach, applying sequential filters of increasing stringency, ensures that only the most promising compounds advance. The key criteria and corresponding experimental methodologies are outlined below.

Table 1: Key Triage Criteria and Corresponding Experimental Protocols

| Triage Criterion | Experimental Protocol | Key Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Confirmation & Dose-Response | Re-test of primary hits in dose; confirmatory dose-response curves to determine potency (IC50, EC50, etc.) [21]. | Potency (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀), Efficacy (% maximum effect), and replication of original activity. |

| Chemical and Pharmacological Purity | Interrogation via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and various counter-assays [21]. | Verification of compound identity and purity; identification of pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS), aggregation, fluorescence. |

| Selectivity and Early Safety | Profiling against related target families and anti-targets; cytotoxicity assessment in relevant cell lines [21]. | Selectivity index; early understanding of potential off-target effects and general cellular toxicity. |

| Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | Synthesis and testing of structurally related analogs to probe key chemical groups [21]. | Assessment of chemical tractability and initial identification of moieties critical for biological activity. |

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) | Calculation of LE = (1.37 pIC50)/Number of Heavy Atoms. | Normalizes potency for molecular size, identifying potent but small compounds with room for optimization [22]. |

| Target Agnostic Functional Validation | More complex phenotypic or pathway-specific assays (e.g., high-content imaging, transcriptomics) [8]. | Confirmation of desired phenotypic effect in a more disease-relevant system; understanding broader functional impact. |

Detailed Protocol for Primary Hit Confirmation

The first critical step after a primary screen is to confirm the activity of initial hits.

- Objective: To verify that the observed activity in the primary high-throughput screen is reproducible and to quantify the potency and efficacy of the hit compounds.

- Materials:

- Source of Hit Compounds: Hit compounds identified from the primary phenotypic screen, reconstituted in DMSO or appropriate buffer [21].

- Cell Line/Assay System: The same cell-based or biochemical assay system used in the primary screen, carefully validated for robustness and pharmacological sensitivity [21].

- Equipment: Liquid handling robots, microplate readers, or high-content imaging systems suitable for dose-response assays.

- Methodology:

- Compound Dilution: Prepare a serial dilution of each hit compound, typically across an 8-point concentration range (e.g., from 10 µM to 1 nM).

- Assay Execution: Test each concentration in replicate (e.g., n=3) within the validated phenotypic assay. Include appropriate controls on every plate: positive control (known modulator of the phenotype), negative control (vehicle, e.g., DMSO), and a reference compound if available.

- Data Analysis: Fit the concentration-response data to a four-parameter logistic (e.g., "Hill equation") model to calculate the half-maximal effective or inhibitory concentration (EC50 or IC50) and the maximum efficacy (Emax) for each compound [20]. Compounds that fail to show a dose-dependent response or reproduce the initial activity are deprioritized.

Comparative Analysis of Triage Approaches: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based

The strategic emphasis of hit triage differs significantly between phenotypic and target-based screening paradigms, influencing the choice of criteria and the order of operations. The table below provides a direct comparison.

Table 2: Comparison of Hit Triage Emphasis in Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

| Triage Aspect | Phenotypic Screening Triage | Target-Based Screening Triage |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify compounds that modulate a biologically relevant phenotype; mechanism is initially unknown [8]. | Identify compounds that potently and selectively modulate a specific, predefined molecular target [10]. |

| Mechanism of Action (MOA) | A major challenge; target deconvolution is a secondary, often lengthy, step post-triage [8] [10]. | Inherently known from the outset; triage focuses on optimizing binding and effect on the target. |

| Key Early Triage Criteria | Strength and reproducibility of the phenotypic effect, chemical tractability, and absence of overt toxicity [8]. | Binding affinity (Ki/Kd), potency in a biochemical assay, and selectivity against closely related targets. |

| Role of Chemical Structure | Secondary to function; structural diversity is often prized to enable mapping of chemical space to novel biology [8]. | Central to rational design; used for early SAR and modeling based on the known target structure. |

| Assay Strategy | Prioritizes physiological relevance; may employ multiple, complex cell-based assays early in the triage funnel [21]. | Begins with simple, high-throughput biochemical binding or enzymatic assays; cell-based validation comes later. |

Visualization of the Hit Triage Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, multi-stage nature of a robust hit triage process for phenotypic screening, from initial hit identification to the final selection of validated series for lead optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of a hit triage workflow is dependent on a suite of reliable research reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hit Triage

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Hit Triage |

|---|---|

| Validated Phenotypic Assay Kits | Provide standardized, robust reagents for confirming the primary readout (e.g., cell viability, apoptosis, neurite outgrowth) with minimized variability [21]. |

| Diverse Compound Libraries | Collections of chemically diverse, lead-like small molecules used for screening; their quality and diversity directly impact the success of the initial hit identification [21]. |

| Orthogonal Assay Reagents | Kits or reagents for secondary validation (e.g., biophysical binding assays, high-content imaging probes) that use a different readout technology to confirm activity [21]. |

| Selectivity Panel Assays | Pre-configured assays against common anti-targets or related target families (e.g., kinase panels, GPCR panels) to assess compound selectivity early in the triage process [21]. |

| Analytical Chemistry Tools (e.g., LC-MS) | Used to verify the chemical identity and purity of hit compounds, ensuring the observed activity is due to the intended structure and not an impurity or degradation product [21]. |

| Cell-Based Models (Primary/Stem Cells) | More physiologically relevant cellular systems used in secondary assays to confirm phenotypic effects in a context closer to the native disease state [8] [10]. |

Establishing a robust hit triage process is a cornerstone of successful phenotypic screening campaigns. It requires a deliberate strategy that prioritizes biological relevance and statistical rigor over simplistic structural filters. By integrating sequential layers of confirmation, counter-screening, and orthogonal validation within a multi-disciplinary framework, research teams can effectively navigate the complexity of phenotypic hits. This diligent approach maximizes the likelihood of progressing high-quality, chemically tractable starting points that will withstand the challenges of target deconvolution and lead optimization, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients.

Dose-Response Confirmation and Potency Assessment

In phenotypic drug discovery, hit validation requires robust confirmation of biological activity through dose-response experiments [8] [7]. Assessing potency—the relationship between compound concentration and effect magnitude—is fundamental for prioritizing candidates and understanding their biological impact [23]. Unlike target-based approaches, phenotypic screening hits act through often unknown mechanisms, making careful potency assessment within a physiologically relevant context a critical step before embarking on target deconvolution [8] [24]. This guide compares modern computational tools and methodologies for analyzing dose-response data, focusing on their application within phenotypic screening hit validation strategies.

Comparison of Dose-Response Analysis Platforms

The table below summarizes key software tools for dose-response analysis. GRmetrics and Thunor specialize in advanced metrics for cell proliferation, while REAP and CurveCurator offer robust fitting and high-throughput analysis.

| Tool/Platform Name | Primary Analysis Type | Key Metrics Calculated | Input Data Supported | Specialized Features | User Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRcalculator/GRmetrics [25] [26] | Growth Rate Inhibition | GR50, GRmax, GEC50, hGR | End-point and time-course cell count data | Corrects for division rate confounders; Integrated with LINCS data | Web app (GRcalculator) and R/Bioconductor package (GRmetrics) |

| Thunor [27] | Cell Proliferation & Drug Response | IC50, DIP rate, Activity Area | End-point (viability) and time-course proliferation; IncuCyte, HDF5, TSV | Interactive visualization; Dose-response curve fitting; Dataset tagging and sharing | Web application (Thunor Web) and Python library (Thunor Core) |

| REAP [28] | Robust Dose-Response Potency | IC50, Hill coefficient | CSV with concentration, response, and group | Robust beta regression to handle extreme values; Comparison of multiple curves | Web-based Shiny application |

| CurveCurator [29] | High-Throughput Dose-Response | Potency, Effect Size, Statistical Significance | Proteomics data (MaxQuant, DIA-NN, PD); Viability data (TSV) | 2D-thresholding for hit calling; Automated, unbiased analysis; FDR estimation | Open-source Python platform/command line |

Experimental Protocols for Dose-Response Assessment

Protocol: GR Value Calculation and Metric Extraction

The GR method provides a more accurate assessment of drug sensitivity in dividing cells by being less susceptible to confounding factors like assay duration and cell division rate [25] [26].

- Key Methodological Steps:

- Experimental Data Collection: For each tested concentration, measure the cell count at the start of the assay (x₀), the cell count in untreated control wells after assay duration (x_ctrl), and the cell count in drug-treated wells (x(c)) [26].

- GR Value Calculation: Compute the normalized growth rate inhibition (GR value) for each concentration (c) using the formula:

GR(c) = 2^(log₂(x(c)/x₀) / log₂(x_ctrl/x₀)) - 1[26].- GR(c) = 1 indicates no growth effect relative to control.

- GR(c) = 0 indicates a fully cytostatic effect (complete halt of growth).

- GR(c) < 0 indicates a cytotoxic effect (net cell death) [25].

- Curve Fitting and Metric Extraction: Fit the GR values across the concentration range to a sigmoidal curve model. From the fitted curve, extract key metrics [25]:

- GR50: The drug concentration that produces a GR value of 0.5.

- GRmax: The maximal effect of the drug at the highest tested concentration.

- GEC50: The concentration at the half-maximal effect of the drug.

- hGR: The Hill coefficient, indicating the steepness of the dose-response curve.

Protocol: Robust Beta Regression for Potency Estimation (REAP)

This protocol uses robust statistical modeling to improve the reliability of dose-response estimation, particularly when data contains extreme values [28].

- Key Methodological Steps:

- Data Preparation: Normalize response values to a range of 0 to 1 (e.g., 0% to 100% effect). Format data into a CSV file with three columns: drug concentration, normalized response effect, and group name [28].

- Model Fitting with Robust Beta Regression: The REAP tool fits the median-effect equation using a robust beta regression framework. This method uses a beta law to account for non-normality and heteroskedasticity in the data and employs a minimum density power divergence estimator (MDPDE) to minimize the influence of outliers [28].

- Parameter Estimation: The model estimates key parameters of the dose-response curve, including the Hill slope (β1) and the IC50 (or concentration for any other user-specified effect level). The robust approach provides narrower confidence intervals and higher statistical power, even with extreme but biologically relevant observations [28].

- Statistical Comparison: REAP enables hypothesis testing for comparing effect estimations (e.g., IC50), slopes, and entire models between different treatment groups [28].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Phenotypic Hit Triage and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the strategic integration of dose-response confirmation within the broader phenotypic screening hit validation process [8].

Dose-Response Curve Analysis Logic

This diagram outlines the logical flow for processing raw experimental data into validated dose-response metrics, highlighting the roles of different analytical tools [27] [25] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting dose-response experiments in phenotypic screening.

| Item | Function in Dose-Response Assessment |

|---|---|

| Cell Lines (Primary/Stem) | Provide physiologically relevant in vitro systems for quantifying phenotypic drug effects in a human genetic background [27] [7]. |

| Validated Compound Libraries | High-quality small-molecule collections used for primary screening and follow-up, ensuring a range of chemical and mechanistic diversity [24]. |

| Cell Viability/Proliferation Assays | Reagents (e.g., ATP-based luminescence, fluorescence) to quantify the number of viable cells or their proliferation rate after compound treatment [27]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Instrumentation | Automated liquid handlers, incubators, and plate readers (e.g., IncuCyte) enable scalable, multi-time point data generation for robust dose-response curves [27]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Platforms like Thunor, GRcalculator, and CurveCurator for managing, analyzing, and visualizing large-scale dose-response datasets [27] [25] [29]. |

In phenotypic drug discovery, a primary challenge lies in distinguishing true bioactive compounds from false positives that arise from assay interference or non-specific effects. Counter-screening strategies are indispensable for ruling out non-specific and cytotoxic effects, thereby ensuring the identification of high-quality hits with genuine on-target activity. False positive activity can stem from various sources of compound interference, including compound fluorescence, aggregation, luciferase inhibition, redox reactivity, and general cytotoxicity [30]. These interfering activities can be reproducible and concentration-dependent, mimicking the characteristics of genuinely active compounds and easily obscuring the rare true active compounds, which typically represent only 0.01–0.1% of a screening library [31].

The fundamental purpose of counter-screening is to eliminate compounds that demonstrate activity unrelated to the targeted biology. This process is crucial for improving the specificity of hit validation and ensuring that resources are not wasted on pursuing artifacts [30]. Within the context of a broader phenotypic screening hit validation strategy, counter-screens act as a critical filter to triage hits and focus efforts on the most promising candidates [8]. The strategic implementation of these screens, whether through technology-focused assays or specificity profiling, provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for confirming the biological relevance of screening hits before committing to extensive lead optimization efforts.

Core Counter-Screen Typologies and Applications

Counter-screens are systematically categorized based on the specific type of interference they are designed to detect. Understanding these typologies enables researchers to select appropriate strategies for their specific assay formats and hit validation goals.

Technology Counter-Screens

Technology counter-screens are engineered to identify and eliminate compounds that interfere with the detection technology used in the primary high-throughput screening (HTS) assay [30]. These assays are platform-specific and essential for confirming that observed activity stems from biological interaction rather than technical artifact.

- Luminescence-Based Assays: For primary screens utilizing luminescent readouts, a dedicated luciferase inhibition counter-screen is fundamental. This assay detects compounds that directly inhibit the luciferase reporter enzyme itself, which would otherwise generate false positive signals in pathway-specific assays [30] [31]. Research indicates that firefly luciferase inhibitors can constitute as much as 60% of the actives in certain cell-based assays, making this a critical validation step [31].

- Fluorescence-Based Assays: In fluorescence-based HTS, compound fluorescence can significantly increase detected light, affecting apparent potency. Counter-strategies include using orange/red-shifted fluorophores to minimize spectral overlap, implementing a pre-read step after compound addition but prior to fluorophore addition, employing time-resolved fluorescence with a delay after excitation, or utilizing ratiometric fluorescence outputs [31].

- HTRF and TR-FRET Assays: For assays using HTRF (Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence) or TR-FRET (Time-Resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer), technology counter-screens involve analyzing raw data to detect compounds that directly interfere with the resonance energy transfer signal [30].

Specificity Counter-Screens

Specificity counter-screens identify compounds that are active at the target while filtering out those with undesirable non-specific effects [30]. These assays address biological rather than technological interference.

- Cytotoxicity Screening: In cell-based phenotypic assays, cytotoxicity represents a major source of false positives. A dedicated cytotoxicity assay is essential for detecting and eliminating compounds that modulate signals through non-specific cellular death rather than targeted modulation [30]. This is particularly crucial in assays with longer compound incubation times where cytotoxic effects are more likely to occur [31].

- Aggregation-Based Inhibition: Compound aggregation can lead to non-specific enzyme inhibition through protein sequestration. Characteristic signs of aggregators include inhibition curves with steep Hill slopes, sensitivity to enzyme concentration, and reversibility of inhibition upon addition of detergent such as 0.01–0.1% Triton X-100 [31]. Studies have shown that aggregators can represent as high as 90–95% of actives in some biochemical assays [31].