Phenotypic Screening for Novel Mechanism of Action (MoA) Discovery: Strategies, AI Integration, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phenotypic screening as a powerful, unbiased strategy for discovering novel therapeutic mechanisms of action.

Phenotypic Screening for Novel Mechanism of Action (MoA) Discovery: Strategies, AI Integration, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phenotypic screening as a powerful, unbiased strategy for discovering novel therapeutic mechanisms of action. It explores the foundational principles distinguishing phenotypic from target-based approaches, details advanced methodologies including high-content imaging and AI integration, addresses key challenges in target deconvolution and screening limitations, and validates the approach through real-world success stories and performance metrics. Tailored for drug discovery professionals and researchers, this review synthesizes current innovations and future trends reshaping MoA discovery in complex disease areas.

Rediscovering Phenotypic Screening: An Unbiased Gateway to Novel Biology

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) is defined as a strategy for identifying active compounds based on their effects on observable, disease-relevant biological processes—or phenotypes—without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target involved [1]. This approach stands in contrast to Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD), which begins with a predetermined molecular target hypothesized to play a causal role in disease [2]. The fundamental distinction between these paradigms lies in their starting points: TDD investigates how modulation of a specific target affects a disease phenotype, whereas PDD asks what molecular targets can be identified based on compounds that produce a therapeutic phenotypic effect [1] [3].

After being largely supplanted by target-based approaches during the molecular biology revolution, PDD has experienced a major resurgence since approximately 2011 [1]. This renewed interest followed a surprising observation that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered empirically without a predefined drug target hypothesis [1]. Modern PDD now combines the original concept with advanced tools and strategies, systematically pursuing drug discovery based on therapeutic effects in realistic disease models [1]. This renaissance positions phenotypic screening as a crucial approach for identifying novel therapeutic mechanisms and expanding the druggable genome.

Historical Successes and Key Case Studies

Phenotypic screening has generated numerous first-in-class medicines across diverse therapeutic areas. The following table summarizes notable examples approved or in advanced clinical development:

Table 1: Notable Therapeutics Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Therapeutic | Disease Area | Key Molecular Target/Mechanism | Discovery Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR channel gating and folding correction [1] | Cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants [1] |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulation [1] | Screening for compounds increasing full-length SMN protein [1] |

| Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulation [1] [2] | Phenotypic optimization of thalidomide analogs [2] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A protein inhibition [1] | HCV replicon phenotypic screen [1] |

| SEP-363856 | Schizophrenia | Novel mechanism (non-D2) [1] | Phenotypic screening in disease models [1] |

| Kartogenin | Osteoarthritis | Filamin A/CBFβ interaction disruption [4] | Image-based chondrocyte differentiation assay [4] |

The thalidomide derivatives exemplify how phenotypic screening can reveal entirely novel biological mechanisms. Thalidomide was initially withdrawn due to teratogenicity but later rediscovered for treating multiple myeloma and erythema nodosum leprosum [2]. Phenotypic optimization led to lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which exhibited significantly enhanced potency for TNF-α downregulation with reduced side effects [2]. Subsequent target deconvolution revealed these compounds bind cereblon, a substrate receptor of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, altering its substrate specificity to promote degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 [1] [2]. This novel mechanism has since inspired the development of targeted protein degradation platforms, including PROTACs [2].

Table 2: Additional Case Studies of Phenotypic Screening Success

| Therapeutic/Candidate | Disease Area | Key Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| StemRegenin 1 (SR1) | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Expansion | CD34/CD133 expression screen identified aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonist [4] |

| KAF156 | Malaria | Imidazolopiperazine class with novel action against blood/ liver stages [1] |

| Crisaborole | Atopic Dermatitis | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor discovered through anti-inflammatory screening [1] |

The Phenotypic Screening Workflow: Modern Methodological Advances

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated workflows that integrate advanced cell models, high-content readouts, and computational analysis. The fundamental process involves multiple stages from assay development through hit validation and mechanism elucidation.

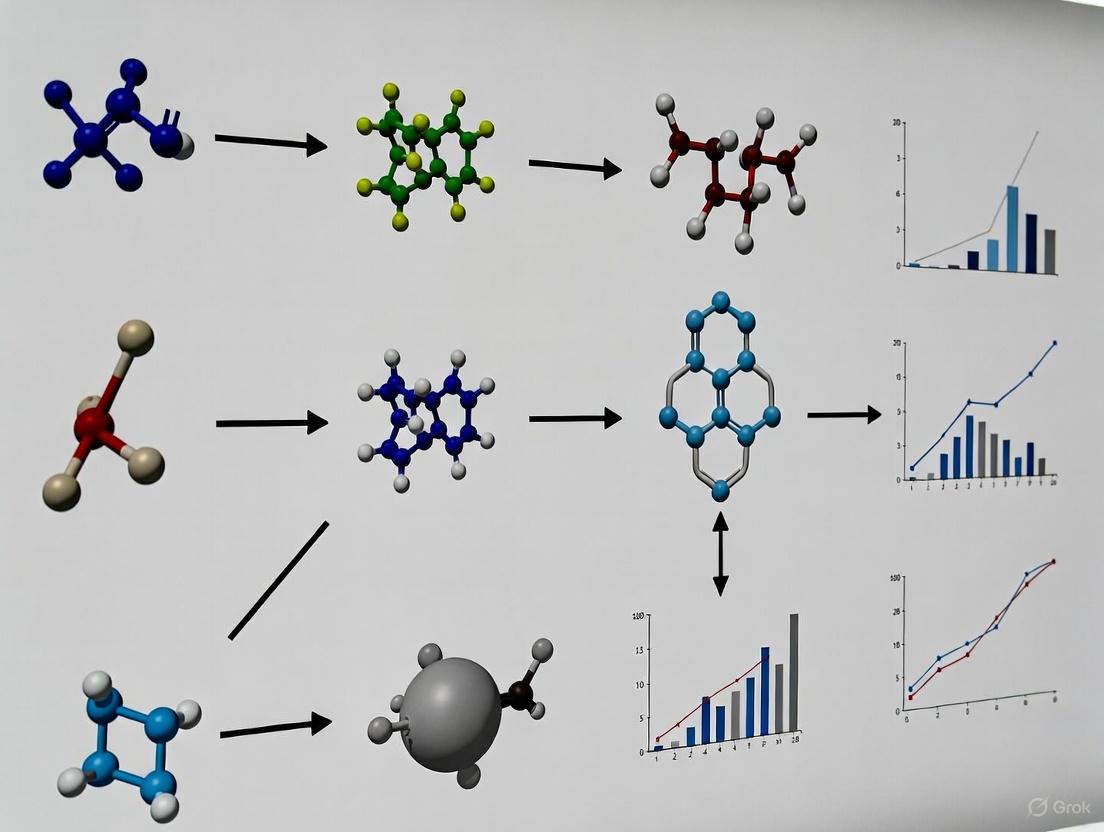

Diagram 1: Modern Phenotypic Screening Workflow (76 characters)

Advanced Model Systems and Readout Technologies

Modern phenotypic screening emphasizes biologically relevant systems that closely recapitulate disease pathophysiology. The "phenotypic screening rule of 3" has been proposed to guide assay development, emphasizing: (1) highly disease-relevant assay systems, (2) maintenance of disease-relevant cell stimuli, and (3) assay readouts closely aligned with clinically desired outcomes [4]. Advanced model systems now include induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), CRISPR-engineered isogenic cell lines, organoids, and complex co-culture systems that better mimic tissue and disease microenvironments [3].

High-content imaging has emerged as a powerful platform for phenotypic screening, enabling multiparametric analysis of cellular responses at single-cell resolution [5]. The ORACL (Optimal Reporter cell line for Annotating Compound Libraries) approach systematically identifies reporter cell lines whose phenotypic profiles most accurately classify compounds across multiple drug classes [5]. This method uses live-cell reporters fluorescently tagged for genes involved in diverse biological functions, allowing efficient classification of compounds by mechanism of action in a single-pass screen [5].

Target Deconvolution and Mechanism of Action Studies

A historical challenge in PDD has been identifying the molecular mechanisms responsible for observed phenotypic effects. Modern approaches have significantly advanced this capability:

Table 3: Methods for Target Deconvolution and Mechanism Elucidation

| Method Category | Specific Approaches | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Methods | Photoaffinity labeling, biotin tagging, mass spectrometry [4] | Direct target identification (e.g., kartogenin binding to filamin A) [4] |

| Genetic Modifier Screening | CRISPR, shRNA, ORF overexpression [4] | Identification of resistance mechanisms and pathway dependencies |

| Gene Expression Profiling | RNA-Seq, microarray analysis, reporter assays [4] | Pathway analysis and classification based on transcriptional signatures |

| Computational Approaches | Connectivity Map, DrugReflector [6] | Pattern recognition and mechanism prediction based on similarity |

The DrugReflector platform represents a recent advance in computational MoA prediction, using a closed-loop active reinforcement learning framework trained on compound-induced transcriptomic signatures [6]. This approach has demonstrated an order-of-magnitude improvement in hit rates compared to random library screening [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Reporter Lines (ORACL) | Enable dynamic monitoring of protein expression and localization [5] | A549 triple-labeled reporters for classification across drug classes [5] |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Multiparametric analysis of morphology and subcellular features [5] | Automated microscopy with ~200 feature extraction per cell [5] |

| CD-Tagging Technology | Genomic tagging of endogenous proteins with fluorescent markers [5] | Creation of reporter cell lines with native protein regulation [5] |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Covalent capture of compound-protein interactions [4] | Kartogenin-biotin conjugate for filamin A identification [4] |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Genome-wide functional assessment of gene contributions to phenotype [4] | Identification of resistance mechanisms and synthetic lethal interactions |

Signaling Pathways Elucidated Through Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening has revealed novel biological mechanisms and unexpected connections in cellular signaling networks. The kartogenin example illustrates how phenotypic discovery can illuminate previously unrecognized regulatory pathways:

Diagram 2: Kartogenin Chondrogenesis Pathway (47 characters)

This pathway, discovered through phenotypic screening, demonstrates how kartogenin binding to filamin A disrupts its interaction with CBFβ, allowing CBFβ translocation to the nucleus where it activates RUNX transcription factors and drives chondrocyte differentiation [4]. This mechanism was entirely novel when discovered and highlighted the potential of phenotypic approaches to identify previously unexplored therapeutic strategies.

Similarly, the discovery of cereblon as the target of thalidomide derivatives revealed a completely unexpected mechanism wherein drug binding reprograms E3 ubiquitin ligase specificity, leading to selective degradation of pathogenic transcription factors [1] [2]. This mechanism has not only explained the therapeutic effects of these drugs but has also spawned an entirely new modality in drug discovery—targeted protein degradation.

Future Directions and Integrative Approaches

The future of phenotypic screening lies in its integration with target-based approaches and emerging technologies. Hybrid strategies that combine the unbiased nature of phenotypic screening with the precision of target-based validation are increasingly shaping drug discovery pipelines [2]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are playing a central role in parsing complex, high-dimensional datasets generated by phenotypic screens, enabling identification of predictive patterns and emergent mechanisms [2].

Multi-omics integration provides a comprehensive framework for linking observed phenotypic outcomes to discrete molecular pathways [2]. The incorporation of transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic data allows researchers to build more complete models of compound activities and mechanisms. As these technologies continue to advance, phenotypic screening is poised to remain at the forefront of first-in-class drug discovery, particularly for complex diseases with polygenic etiologies and poorly understood underlying biology.

Phenotypic screening continues to evolve from its serendipitous origins to a systematic, technology-driven discipline that expands the druggable genome, reveals novel therapeutic mechanisms, and delivers transformative medicines for challenging diseases.

The drug discovery process relies heavily on two primary screening paradigms: phenotypic screening and target-based screening. Phenotypic screening involves testing compounds in biologically relevant systems, such as cells, tissues, or whole organisms, to identify those that produce a desired therapeutic effect without prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [1] [7]. In contrast, target-based screening employs a reductionist approach, focusing on compounds that interact with a predefined molecular target, typically a protein with a hypothesized role in disease pathogenesis [8] [9]. Over the past two decades, target-based strategies dominated pharmaceutical discovery, but phenotypic screening has experienced a significant resurgence following analyses revealing its disproportionate success in producing first-in-class medicines [10] [1] [4]. This resurgence is particularly relevant for discovering compounds with novel mechanisms of action (MoA), as phenotypic approaches allow biological systems to reveal unanticipated therapeutic targets and pathways [1] [4]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these complementary approaches, with special emphasis on their application in novel MoA research.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

Phenotypic Screening: A Target-Agnostic Approach

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) is defined by its focus on modulating a disease phenotype or biomarker to provide therapeutic benefit rather than acting on a pre-specified target [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning PDD is that observable phenotypes—such as changes in cell morphology, viability, motility, or signaling pathways—result from the complex interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors within a biological system [7]. By screening for compounds that reverse or ameliorate disease-associated phenotypes, researchers can identify bioactive molecules without the constraint of target-based hypotheses, potentially revealing unexpected cellular processes and novel mechanisms of action [1].

Modern phenotypic screening has evolved significantly from its historical origins, with advances in high-content imaging, functional genomics, and the development of more physiologically relevant model systems enabling more sophisticated and predictive assays [1] [7]. Contemporary PDD embraces the complexity of biological systems, recognizing that many diseases involve polygenic influences and complex network interactions that may be poorly served by single-target modulation [1] [8].

Target-Based Screening: A Reductionist Strategy

Target-based drug discovery (TDD) operates on the premise that diseases can be treated by modulating the activity of specific molecular targets, typically proteins identified through genetic analysis or biological studies as being causally involved in disease pathogenesis [8] [9]. This approach requires substantial prior knowledge of disease mechanisms, including the identification and validation of specific molecular targets before screening commences [8].

The TDD process typically begins with target identification and validation, followed by the development of biochemical or simple cellular assays that measure compound interactions with the defined target [8] [9]. This reductionist strategy allows for highly specific optimization of compounds against their intended targets but may overlook complex physiological interactions and off-target effects that could contribute to efficacy or toxicity [8]. Target-based approaches have been particularly successful in developing best-in-class drugs that improve upon existing mechanisms but have demonstrated limitations in identifying truly novel therapeutic mechanisms [10] [1].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Screening Approaches

| Feature | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Modulation of observable disease phenotype without target pre-specification | Modulation of predefined molecular target with hypothesized disease role |

| Knowledge Prerequisite | Disease-relevant biological model; target agnostic | Validated molecular target and its disease association |

| Typical Assay Systems | Cell-based assays (2D, 3D, organoids), whole-organism models | Biochemical assays, recombinant cell systems, protein-binding assays |

| Mechanism of Action | Often unknown initially; requires deconvolution | Defined from the outset based on target hypothesis |

| Theoretical Basis | Systems biology; emergent properties | Reductionism; specific molecular interactions |

Historical Context and Success Rates

The historical trajectory of drug discovery reveals a pendulum swing between phenotypic and target-based approaches. Before the 1980s, most medicines were discovered through observational methods of compound effects on physiology, often in whole organisms or human patients [1]. The advent of molecular biology, recombinant DNA technology, and genomics in the late 20th century prompted a major shift toward target-based approaches, with the expectation that greater mechanistic understanding would improve drug discovery efficiency [1] [9].

A seminal analysis by Swinney and Anthony (2011) examined discovery strategies for new molecular entities approved between 1999 and 2008, finding that phenotypic screening accounted for 56% of first-in-class drugs, compared to 34% for target-based approaches [4]. More recent analyses confirm this trend, with phenotypic strategies continuing to contribute disproportionately to the discovery of innovative therapies with novel mechanisms [1]. Notable examples of drugs emerging from phenotypic screens include ivacaftor and lumacaftor for cystic fibrosis, risdiplam for spinal muscular atrophy, and daclatasvir for hepatitis C [1].

Despite the dominance of target-based approaches in pharmaceutical screening portfolios over recent decades, phenotypic screening has maintained an advantage in identifying first-in-class medicines, while target-based screening has excelled in producing best-in-class drugs that optimize existing mechanisms [10]. This pattern highlights the complementary strengths of both approaches within a comprehensive drug discovery strategy.

Table 2: Historical Success Metrics for Screening Approaches

| Metric | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| First-in-class Drugs (1999-2008) | 56% of NMEs [4] | 34% of NMEs [4] |

| Best-in-class Drugs | Lower proportion [10] | Higher proportion [10] |

| Novel Target Identification | Strong capability [1] | Limited to predefined targets |

| Translation to Clinical Efficacy | Potentially higher for complex diseases [7] | Variable; can fail due to inadequate target validation |

| Recent Trends | Resurgence since approximately 2011 [1] | Remain dominant but with recognition of limitations |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Phenotypic Screening Workflows

Phenotypic screening employs diverse methodological frameworks depending on the biological context and disease under investigation. A generalized workflow encompasses several key stages:

1. Biological Model Selection: The foundation of a successful phenotypic screen is choosing a physiologically relevant system that faithfully recapitulates key aspects of human disease biology. Modern approaches increasingly utilize complex model systems including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), 3D organoids, co-cultures, and microphysiological systems (organs-on-chips) that better mimic tissue architecture and function compared to traditional 2D monocultures [1] [7]. For example, in neurodegenerative disease research, iPSC-derived neurons from patients can model disease-specific phenotypes not observable in immortalized cell lines [7].

2. Assay Development and Validation: The phenotypic assay must be designed to measure a disease-relevant endpoint with robust statistical performance. Vincent et al. (2015) proposed a "phenotypic screening rule of 3" emphasizing: (1) use of disease-relevant assay systems, (2) maintenance of disease-relevant stimuli, and (3) implementation of readouts closely linked to clinical outcomes [4]. Assay validation establishes performance metrics including Z-factor, signal-to-noise ratio, and intra-assay variability to ensure reliable detection of true positive hits [7].

3. Compound Library Screening: Phenotypic screens may utilize diverse compound libraries including small molecules, siRNA, antibodies, or CRISPR-based perturbagens [11]. Unlike target-based screens that often prioritize drug-like properties, phenotypic screens may benefit from structural diversity to maximize opportunities for novel mechanism discovery [7]. Screening can range from high-throughput formats (100,000+ compounds) to more focused, hypothesis-driven selections [11].

4. Hit Confirmation and Characterization: Initial hits undergo confirmation in dose-response experiments and counter-screens to exclude artifacts and assess preliminary cytotoxicity [7]. Advanced high-content imaging can capture multiple phenotypic parameters simultaneously, enabling multiparametric analysis and classification of compound effects based on phenotypic profiles [10] [7].

5. Target Deconvolution and Mechanism Elucidation: A critical challenge in PDD is identifying the molecular target(s) responsible for the observed phenotype. Multiple approaches exist for target identification, including affinity chromatography, protein microarrays, genetic modifier screens (CRISPR, siRNA), resistance mutation selection, and computational methods [1] [4]. Modern approaches often combine several methods to build confidence in proposed mechanisms.

Target-Based Screening Workflows

Target-based screening follows a more linear, hypothesis-driven pathway:

1. Target Identification and Validation: The process begins with selecting a molecular target—typically a protein, gene, or specific molecular mechanism—with demonstrated or hypothesized involvement in disease pathogenesis [8] [9]. Targets are classified as either genetic targets (genes or gene-derived products linked to disease through genetic evidence) or mechanistic targets (receptors, enzymes, or other proteins with established biological roles in disease processes) [8]. Validation employs techniques including gene knockouts, dominant negative mutants, antisense technology, and expression profiling to establish causal relationships between target modulation and therapeutic benefit [8].

2. Assay Development: Target-based assays are designed to measure compound interactions with the defined target, typically using biochemical assays (enzyme activity, receptor binding) or simple cellular systems with recombinant target expression [8] [9]. These assays prioritize specificity and sensitivity for the target of interest, often employing techniques such as fluorescence polarization, AlphaScreen, or surface plasmon resonance to detect molecular interactions [12] [9].

3. High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Large compound libraries (often >1 million compounds) are screened against the target using automated systems [12]. The primary readout is typically a single parameter measuring target engagement or functional modulation, enabling rapid triage of compounds based on potency and efficacy against the defined target [9].

4. Hit-to-Lead Optimization: Confirmed hits undergo extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies to optimize potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties [9]. Modern TDD frequently employs structure-based drug design using X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM structures of target-compound complexes to guide rational optimization [9].

5. Mechanistic Confirmation: Compounds with optimized properties are tested in more complex biological systems to verify that target engagement produces the expected phenotypic and therapeutic effects, establishing pharmacological proof-of-concept before advancing to animal models and clinical development [9].

Case Study: Kartogenin - Phenotypic Screening Success

The discovery of kartogenin (KGN) illustrates a successful phenotypic screening approach for novel MoA discovery. Researchers sought compounds that could induce chondrocyte differentiation for osteoarthritis treatment using an image-based screen of primary human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [4]. The assay measured rhodamine B staining, which highlights cartilage-specific components like proteoglycans and type II collagen [4].

From a screen of >20,000 compounds, KGN emerged as a potent inducer of chondrocyte differentiation (EC₅₀ ~100 nM) that upregulated multiple chondrocyte markers including SOX9, aggrecan, and lubricin [4]. In both chronic (collagenase VII-induced) and acute (surgical ligament transection) mouse models of cartilage damage, weekly intra-articular KGN injection reduced inflammation and pain while promoting cartilage regeneration [4].

The target deconvolution process employed a biotinylated, photo-crosslinkable KGN analog to identify filamin A (FLNA) as the molecular target [4]. Further mechanistic studies revealed that KGN disrupts the interaction between FLNA and core-binding factor beta subunit (CBFβ), leading to CBFβ translocation to the nucleus where it activates RUNX transcription factors and drives chondrocyte differentiation [4]. This example demonstrates how phenotypic screening can identify both novel chemical matter and previously unknown regulatory mechanisms with therapeutic potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Screening Approaches

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Models | iPSCs, 3D organoids, primary cells, co-culture systems | Provide physiologically relevant contexts for phenotypic screening; patient-derived cells enable personalized disease modeling [1] [7] |

| Whole-Organism Models | Zebrafish, C. elegans, Drosophila, rodent models | Enable in vivo phenotypic screening with systemic physiology; useful for assessing complex behaviors and organism-level responses [11] [7] |

| Molecular Probes | Fluorescent tags, bioluminescent reporters, affinity handles (biotin) | Facilitate target identification and validation; enable visualization and quantification of cellular processes [4] [9] |

| Genomic Tools | CRISPR libraries, siRNA collections, cDNA overexpression constructs | Support target validation and identification; enable genetic screening approaches [10] [4] |

| Compound Libraries | Diverse small molecules, fragment libraries, natural products | Source of chemical matter for screening; diversity enhances novelty potential [7] |

| Detection Reagents | Antibodies, fluorescent dyes, enzyme substrates | Enable measurement of specific phenotypic endpoints or target engagement [4] [7] |

Advantages and Limitations: A Comparative Analysis

Strengths and Challenges of Phenotypic Screening

Phenotypic screening offers several distinctive advantages for novel MoA research. Its primary strength lies in its target-agnostic nature, which allows discovery of compounds with completely novel mechanisms without prior target hypothesis [1] [7]. This approach has consistently demonstrated superior performance in identifying first-in-class medicines, likely because it embraces the complexity of disease biology rather than attempting to reduce it to single targets [1] [4]. By screening in biologically relevant systems, phenotypic approaches inherently select for compounds with favorable cellular properties, including membrane permeability, solubility, and absence of overt cytotoxicity, potentially reducing attrition in later development stages [10]. Furthermore, phenotypic screening can identify compounds that act through polypharmacology—simultaneous modulation of multiple targets—which may be advantageous for treating complex, multifactorial diseases [1].

The most significant challenge in phenotypic screening is target deconvolution—identifying the specific molecular target(s) responsible for the observed phenotypic effect [1] [4] [7]. This process can be time-consuming, expensive, and technically challenging, requiring specialized approaches such as affinity chromatography, genetic modifier screens, or resistance mutation selection [4]. Phenotypic assays also tend to be lower in throughput and more complex to implement than target-based assays, potentially limiting the number of compounds that can be screened [10] [7]. Additionally, phenotypic hits may have undefined specificity, with potential off-target effects that are difficult to predict without comprehensive mechanism elucidation [7].

Strengths and Challenges of Target-Based Screening

Target-based screening offers distinct advantages in mechanistic clarity and efficiency. Because the molecular target is defined from the outset, the path from hit identification to optimization is typically more straightforward, with clear structure-activity relationship parameters for medicinal chemistry [9]. Target-based assays generally enable higher throughput screening of larger compound libraries at lower cost compared to phenotypic approaches [10] [9]. The predefined mechanism also facilitates rational drug design using structural biology and computational modeling approaches to optimize compound properties [9]. Furthermore, target-based approaches simplify safety assessment by enabling focused evaluation of target-related toxicities early in the discovery process [9].

The primary limitation of target-based screening is its reliance on predetermined hypotheses about disease mechanisms, which may be incomplete or incorrect [8]. This approach risks investing significant resources in targets that ultimately prove irrelevant to human disease, contributing to high attrition rates in clinical development [8]. Target-based assays also employ reductionist systems that may fail to capture the complex physiological context of native tissues, potentially identifying compounds that are ineffective in more biologically relevant settings [8] [9]. Additionally, the focus on single targets may overlook the therapeutic potential of polypharmacology or fail to identify compensatory mechanisms that limit efficacy in intact biological systems [1] [8].

Table 4: Comprehensive Comparison of Advantages and Limitations

| Aspect | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Novel MoA Discovery | High potential for unprecedented mechanisms [1] [7] | Limited to predefined targets and mechanisms |

| Physiological Relevance | Higher; uses complex biological systems [10] [7] | Lower; uses reduced systems [8] [9] |

| Throughput | Generally lower due to assay complexity [10] | Generally higher with simpler assays [10] [9] |

| Target Identification | Required after screening; can be challenging [1] [4] | Defined before screening; straightforward |

| Chemical Optimization | Can proceed without target knowledge but may be indirect [1] | Direct with clear SAR based on target structure [9] |

| Polypharmacology | Can naturally identify multi-target compounds [1] | Typically designed for specificity; may require combination approaches |

| Resource Requirements | Higher per compound screened [10] | Lower per compound screened [10] |

| Risk of Clinical Attrition | Potentially lower for efficacy [7] | Higher due to inadequate target validation [8] |

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

The historical dichotomy between phenotypic and target-based screening is increasingly giving way to integrated strategies that leverage the strengths of both approaches [10] [9]. Many successful drug discovery programs now employ phenotypic screening for initial hit identification followed by target-based approaches for lead optimization once mechanisms are elucidated [10] [9]. This hybrid model combines the novelty potential of phenotypic discovery with the efficiency and precision of target-focused optimization.

Several technological advances are driving innovation in both screening paradigms. For phenotypic screening, developments in high-content imaging, artificial intelligence-based image analysis, and functional genomics are enhancing the depth and throughput of phenotypic characterization [7]. The availability of more physiologically relevant model systems, including iPSC-derived cell types, 3D organoids, and organ-on-a-chip platforms, is improving the translational predictive power of phenotypic assays [1] [7]. For target-based screening, advances in structural biology, biophysical methods, and computational prediction are enabling more effective targeting of challenging protein classes and complex molecular interactions [9].

The emerging field of chemical genomics is particularly promising for bridging phenotypic and target-based approaches. By linking compound-induced phenotypic profiles to specific molecular targets or pathways using pattern-matching algorithms and large-scale reference databases, researchers can potentially accelerate both target deconvolution for phenotypic hits and mechanism identification for target-based compounds [4]. As these technologies mature, they promise to further blur the distinctions between screening paradigms, enabling more efficient discovery of therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action.

Phenotypic and target-based screening represent complementary rather than opposing strategies in modern drug discovery. Phenotypic screening excels at identifying first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action, leveraging biological complexity to reveal unanticipated therapeutic opportunities. Target-based screening offers efficiency and precision in developing best-in-class drugs against validated molecular targets. The most productive discovery pipelines strategically integrate both approaches, using phenotypic methods for initial innovation and target-based techniques for optimization. As technological advances continue to enhance both screening paradigms, the future of drug discovery lies not in choosing between these approaches but in developing sophisticated frameworks for their synergistic application. For researchers focused on novel MoA discovery, phenotypic screening remains an indispensable tool, provided that challenges in target deconvolution and assay complexity are addressed through appropriate methodological and technological solutions.

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) represents a biology-first approach to identifying novel therapeutics by focusing on the modulation of disease phenotypes in realistic biological systems, without a pre-specified molecular target hypothesis [1] [3]. This strategy stands in contrast to target-based drug discovery (TDD), which relies on modulating specific molecular targets with known roles in disease [2]. Historically, PDD was the foundation of most drug discovery before being supplanted in the 1980s-2000s by the more reductionist TDD approach, fueled by advances in molecular biology and genomics [1]. However, a landmark analysis revealed that between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered through phenotypic screening, leading to a major resurgence of interest in this empirical strategy [1].

Modern PDD leverages sophisticated tools including high-content imaging, complex disease models, and functional genomics to systematically pursue drug discovery based on therapeutic effects [1] [13]. This whitepaper details key historical successes of PDD, highlighting how this unbiased approach has expanded the "druggable" target space and delivered transformative medicines with novel mechanisms of action (MoA) for challenging diseases.

Paradigm-Shifting Successes in Phenotypic Drug Discovery

The following case studies exemplify how phenotypic screening has successfully identified first-in-class therapies, often revealing entirely novel and unexpected biological targets and mechanisms.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) NS5A Inhibitors

The treatment of Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was revolutionized by the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), with NS5A inhibitors like daclatasvir becoming a cornerstone of combination therapies that now cure >90% of patients [1]. The initial discovery occurred through a phenotypic screen using an HCV replicon system. This approach identified small-molecule modulators of the HCV protein NS5A, which was known to be essential for viral replication but possessed no known enzymatic activity, making it a non-obvious target for traditional TDD [1]. This discovery underscores the power of PDD to identify chemical tools that probe and validate novel target space.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) CFTR Modulators

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease caused by mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. Phenotypic screens on cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants identified compounds that improved CFTR function through two distinct and unanticipated MoAs [1]:

- Potentiators (e.g., ivacaftor) that improve the channel gating properties of CFTR at the cell surface.

- Correctors (e.g., tezacaftor, elexacaftor) that enhance the folding and trafficking of CFTR to the plasma membrane.

The subsequent development of the triple-combination therapy (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor) addresses 90% of the CF patient population and stands as a landmark achievement derived from target-agnostic screening [1].

Immunomodulatory Imide Drugs (IMiDs) and Cereblon

The discovery of thalidomide and its analogs, lenalidomide and pomalidomide, is a classic example of PDD where the molecular target and MoA were elucidated long after the observation of clinical efficacy [1] [2]. Thalidomide was initially marketed for morning sickness but withdrawn due to teratogenicity. Phenotypic observations of its efficacy in treating leprosy and later multiple myeloma spurred further investigation [1]. Phenotypic screening of analogs led to the discovery of lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which exhibited enhanced immunomodulatory and anticancer potency with reduced side effects [2]. Years post-approval, the MoA was uncovered: these drugs bind to the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cereblon, reprogramming its substrate specificity to promote the ubiquitination and degradation of specific transcription factors, IKZF1 and IKZF3 [1] [2]. This novel MoA has not only explained the efficacy of IMiDs in blood cancers but has also founded the entire field of targeted protein degradation, including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [2].

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) SMN2 Splicing Modulators

Spinal muscular atrophy is a rare neuromuscular disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SMN1 gene. Humans have a nearly identical SMN2 gene, but a splicing defect leads to the exclusion of exon 7 and the production of a truncated, unstable protein. Phenotypic screens independently identified small molecules, including risdiplam, that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase levels of full-length, functional SMN protein [1]. The MoA involves binding to two specific sites on SMN2 pre-mRNA and stabilizing the U1 snRNP complex, an unprecedented target for small-molecule drugs [1]. Risdiplam was approved in 2020 as the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA.

Table 1: Summary of Key First-in-Class Therapies from Phenotypic Screening

| Therapy | Disease Area | Key Molecular Target/Mechanism Identified Post-Discovery | Novelty of Mechanism of Action (MoA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daclatasvir (NS5A Inhibitors) | Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | HCV NS5A protein (non-enzymatic) [1] | First-in-class; novel viral target without enzymatic activity. |

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) | CFTR potentiators & correctors [1] | Novel MoAs (channel potentiation, protein folding/trafficking correction). |

| Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide | Multiple Myeloma, Blood Cancers | Cereblon/E3 Ubiquitin Ligase [1] [2] | Molecular glue inducing targeted protein degradation. |

| Risdiplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | SMN2 pre-mRNA Splicing [1] | Small-molecule modulation of pre-mRNA splicing. |

Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Screening

The successful application of PDD relies on robust, disease-relevant experimental models and protocols. The following outlines a generalized workflow and key methodologies.

General Workflow for a Phenotypic Screen

The typical workflow involves multiple stages, from model selection to hit validation.

Diagram 1: Phenotypic Screening Workflow

Detailed Methodologies for Key Stages

1. Disease Model Selection and Validation:

- Patient-derived cells or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): Provide a genetically relevant human context. For example, iPSC-derived motor neurons for SMA research [3] [11].

- Genetically engineered animal models: Transgenic, knock-out, or knock-in animals (e.g., zebrafish, mice) that recapitulate key disease phenotypes are used for in vivo screening [11]. Example: Transgenic mouse overexpressing human α-synuclein for Parkinson's disease modeling [11].

- Complex cellular systems: 3D organoids, co-cultures, or "organs-on-chips" are increasingly used to capture tissue-level pathophysiology and multicellular interactions [11]. Protocol: Culture cells in specialized matrices (e.g., Matrigel) to promote 3D structure formation.

2. Phenotypic Assay Development and High-Throughput Screening (HTS):

- High-Content Imaging (HCA): Cells are stained with fluorescent dyes or antibodies. Automated microscopy captures images, and software quantifies hundreds of morphological and intensity-based features (e.g., cell size, shape, protein localization/organization) [13].

- Protocol Example (Cell Painting): Seed cells in 384-well plates. Treat with compound libraries. Fix and stain with a panel of dyes (e.g., Phalloidin for F-actin, Hoechst for nucleus, Concanavalin A for ER). Image with an automated confocal microscope. Use segmentation algorithms to identify single cells and extract ~1,000 morphological features per cell [13].

- Functional biomarker assays: Measure disease-relevant physiological outputs, such as cytokine secretion (ELISA/electrochemiluminescence), CFTR chloride channel function (halide-sensitive fluorescent dyes), or viral replication (luciferase-based reporters in the HCV replicon system) [1] [11].

- Viability/ proliferation assays: Standard readouts for oncology and infectious disease (e.g., ATP-based luminescence assays).

3. Hit Validation and Lead Optimization:

- Counter-screens: Test hits against related but distinct models to establish selectivity and rule out nonspecific effects (e.g., assay interference).

- Dose-response curves: Confirm potency and efficacy (e.g., IC50, EC50) in the primary phenotypic assay.

- Chemical exploration: Establish structure-activity relationships (SAR) through iterative medicinal chemistry cycles, guided by the phenotypic readout, not target binding [1] [11].

- Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling: Use biomarker assays developed during in vitro discovery to demonstrate target engagement and pathway modulation in vivo, aiding dose prediction for clinical trials [11].

4. Target Deconvolution:

- Chemical proteomics: Immobilize the hit compound on a solid support to create an affinity matrix. Incubate with cell lysates, pull down interacting proteins, and identify them via mass spectrometry. This was instrumental in identifying Cereblon as the target of thalidomide [2].

- Functional genomics: Use CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi knockout/knockdown libraries to identify genes whose loss either resists or enhances the compound's phenotypic effect.

- Transcriptomics/proteomics: Profile global gene expression or protein abundance changes in response to compound treatment and compare to databases of genetic or compound-induced profiles (e.g., Connectivity Map) to infer MoA and potential targets [3].

- Resistance generation: Culture cells under increasing compound pressure and sequence clones that survive, as mutations often point to the drug target or pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful phenotypic screening and subsequent MoA elucidation rely on a suite of specialized tools and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Discovery

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PDD |

|---|---|---|

| Disease-Relevant Cell Models | Patient-derived cells, iPSC-derived lineages (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes), 3D Organoids [11] | Provide physiologically relevant human cellular context for screening; capture disease-specific phenotypes. |

| Advanced Imaging Reagents | Cell Painting dye kits (e.g., Phalloidin, Hoechst, Concanavalin A), biosensors (e.g., Ca²⁺, cAMP), fluorescent antibody panels [13] | Enable high-content analysis of complex cellular morphology, signaling, and composition. |

| Genomic & Proteomic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout libraries, siRNA/shRNA collections, Affinity Purification Mass Spec (AP-MS) kits, Phospho-specific Antibodies [2] | Facilitate target identification and deconvolution (functional genomics, chemical proteomics). |

| Specialized Compound Libraries | Diverse small-molecule collections, FDA-approved drug libraries (for repurposing), Fragment-based libraries [11] | Source of chemical starting points for unbiased screening; designed to maximize chemical space coverage. |

| In Vivo Model Organisms | Zebrafish (Danio rerio), C. elegans, Drosophila, Transgenic/ Xenograft Mouse Models [11] | Allow for in vivo phenotypic screening in a whole-organism context with conserved biology. |

Visualizing the Impact of Phenotypic Discovery

The following diagram illustrates how phenotypic screening has successfully targeted diverse and novel cellular processes, expanding the conventional "druggable" genome.

Diagram 2: Novel Target Spaces Opened by PDD

The landscape of drug discovery is witnessing a significant resurgence of phenotypic screening, moving away from the previously dominant target-based paradigm. This shift is driven by the convergence of three powerful technologies: high-content imaging for generating rich, multidimensional data; complex, physiologically relevant disease models that better recapitulate human biology; and advanced artificial intelligence (AI) capable of interpreting complex biological patterns. This whitepaper details how this synergy is creating a robust framework for de novo mechanism of action (MoA) research, enabling the unbiased discovery of novel therapeutic pathways and accelerating the development of first-in-class medicines.

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) entails the identification of active compounds based on measurable biological responses in cells or whole organisms, often without prior knowledge of their specific molecular targets [2]. This approach captures the complexity of cellular systems and has been historically pivotal in discovering first-in-class agents and uncovering novel therapeutic mechanisms [2]. The central challenge in MoA research has been the inability to fully model human disease complexity with simplistic assays and single-target hypotheses. Target-based approaches, while rational, often fail in clinical trials due to an incomplete understanding of disease biology and compensatory network mechanisms [2]. Phenotypic screening addresses this by starting with a biological outcome, thereby allowing the discovery of compounds with polypharmacology or those acting on previously uncharacterized pathways.

The modern resurgence of PDD is not a return to old methods but a transformation powered by technological leaps. The integration of high-content imaging, complex disease models, and AI is reshaping drug discovery pipelines, creating adaptive, integrated workflows that enhance efficacy and overcome resistance [2]. This powerful combination allows researchers to start with biology, add molecular depth, and leverage algorithms to reveal patterns, moving the field toward more effective and better-understood therapies [14].

Technological Drivers of the Resurgence

Advanced High-Content Imaging and Profiling

High-content screening (HCS) is an advanced phenotypic screening technique that combines automated microscopy with quantitative image analysis to evaluate the effects of chemical or genetic perturbations on cells [15]. It provides multidimensional data on changes in cell morphology, protein expression, localization, and metabolite levels, offering comprehensive insights into cellular responses [15].

Key Assay Technologies:

- Cell Painting: A widely utilized, multiplexed staining method that uses typically six fluorescent dyes to label and image six to eight key cellular components, including nuclear DNA, cytoplasmic RNA, nucleoli, endoplasmic reticulum, actin cytoskeleton, Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, and mitochondria [16] [17]. This generates a detailed morphological "fingerprint" or profile for each perturbation.

- Cell Painting PLUS (CPP): An evolution of the standard Cell Painting assay, CPP uses iterative staining-elution cycles to significantly expand multiplexing capacity. It enables the separate imaging of at least seven fluorescent dyes labeling nine subcellular compartments in individual channels, thereby improving organelle-specificity and the diversity of phenotypic profiles [16].

- Optimal Reporter Cell Lines (ORACLs): A method for systematically identifying reporter cell lines whose phenotypic profiles most accurately classify a training set of known drugs. This approach maximizes the discriminatory power of phenotypic screens by selecting the most informative cellular biomarkers for a given research question [5].

Table 1: Key High-Content Imaging and Profiling Assays

| Assay Name | Core Principle | Key Readouts | Advantages for MoA Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting [16] [17] | Multiplexed staining with 6 fluorescent dyes | Morphological profiles of 6-8 organelles | Untargeted, generates rich, comparable morphological barcodes |

| Cell Painting PLUS (CPP) [16] | Iterative staining & elution cycles | 9+ organelles imaged in separate channels | Enhanced specificity & customizability; reduced spectral crosstalk |

| ORACL (Optimal Reporter) [5] | Live-cell reporters for diverse pathways | Phenotypic profiles predictive of drug class | Identifies optimal cellular system for classifying compounds |

The data generated by these assays is processed through automated image analysis pipelines that perform cell segmentation and extract hundreds of quantitative morphological features related to shape, size, texture, intensity, and spatial relationships [5] [15]. These features are concatenated into a phenotypic profile that succinctly summarizes the effect of a compound, enabling guilt-by-association analysis and MoA prediction [5].

Complex and Translational Disease Models

The physiological relevance of phenotypic screening outcomes is heavily dependent on the cellular models used. There is a growing shift from traditional 2D cell lines to more sophisticated models that better mimic the in vivo environment.

- Primary Cells and Patient-Derived Models: The use of early-passage patient-derived organoids, primary human cells (such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells - PBMCs), and tissues explants maintains high-fidelity to the in vivo disease context, including relevant cell types, epigenetic states, and tissue residency [17].

- 3D Organoids and Spheroids: These models recapitulate the 3D architecture, cell-cell interactions, and phenotypic heterogeneity of native tissues. They are particularly valuable for studying complex diseases like cancer and for toxicology assessments [15].

- Organs-on-a-Chip (OOCs): These microfluidic devices simulate organ-level physiology and functionality, allowing for precise control over cell culture environments, nutrient flow, and drug exposure. They provide highly translatable data on tissue integrity, metabolism, and functional drug responses [18].

The adoption of these complex models was previously constrained by scalability and cost. However, advanced screening methods are now unlocking their potential for high-content phenotypic profiling [17].

Artificial Intelligence and Data Integration

AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), is the critical engine that transforms high-content data into actionable insights for MoA research.

- Image Analysis and Phenotype Classification: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and other DL models automate the analysis of complex cellular images, improving accuracy, speed, and reproducibility. They excel at segmentation of cells and subcellular structures in heterogeneous samples and can identify subtle phenotypic changes invisible to the human eye [15] [18].

- MoA Prediction and Hit Prioritization: AI models can correlate complex morphological profiles induced by compounds to known MoAs, effectively classifying novel compounds into functional drug classes based on phenotypic similarity [5] [18]. Platforms like PhenoModel use multimodal foundation models to connect molecular structures with phenotypic information, enabling virtual screening for molecules that induce a desired phenotype [19].

- Multi-Omics Integration: AI enables the fusion of high-content imaging data with other multimodal datasets, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and genomics. This integration provides a systems-level view of biological mechanisms, improving prediction accuracy and target identification for precision medicine [14]. For example, the JUMP-Cell Painting and OASIS Consortia are benchmarking phenomics data against other omics and in vivo data to increase confidence in the physiological relevance of the cellular responses [16].

Integrated Experimental Workflows for Novel MoA Discovery

The true power for MoA research emerges when these drivers are combined into a cohesive workflow. The following diagram and protocol outline a modern, AI-powered phenotypic screening campaign designed for novel MoA identification.

Detailed Protocol: A Compressed Phenotypic Screening Campaign

This protocol, adapted from Soule et al. (2025), demonstrates a scalable approach for high-content MoA studies using pooled perturbations [17].

Objective: To identify compounds with novel MoAs by screening a chemical library against a complex disease model using a high-content readout, with compression to reduce cost and labor.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological Model: Early-passage patient-derived pancreatic cancer organoids or primary human PBMCs [17].

- Perturbation Library: A library of 316 bioactive small molecules (e.g., FDA-approved drug repurposing library) [17].

- Staining Reagents: Cell Painting dye cocktail [17] or CPP dye set for iterative staining [16].

- Key Instrumentation: Automated liquid handler, high-content imaging system (e.g., confocal microscope with environmental control), high-performance computing cluster.

Procedure:

Pooled Library Design:

- Combine N perturbations (e.g., 316 drugs) into unique pools of size P (e.g., 3-80 drugs per pool). Ensure each perturbation appears in R distinct pools (e.g., R=3, 5, or 7) for statistical robustness.

- This creates a P-fold compression, drastically reducing the number of assay wells compared to a conventional screen [17].

Cell Seeding and Perturbation:

- Seed the complex disease model (e.g., organoids or PBMCs) into assay plates using an automated liquid handler.

- Treat cells with the pre-formed perturbation pools. Include appropriate vehicle control wells (e.g., DMSO).

- Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 24 hours) based on pilot kinetics studies [17].

Multiplexed Staining and High-Content Imaging:

- For Cell Painting: Fix cells and stain with the standard 6-dye cocktail (Hoechst 33342 for nuclei, Concanavalin A-AlexaFluor 488 for ER, MitoTracker Deep Red for mitochondria, Phalloidin-AlexaFluor 568 for F-actin, Wheat Germ Agglutinin-AlexaFluor 594 for Golgi and plasma membrane, and SYTO14 for nucleoli and RNA) [17].

- For CPP: Perform iterative cycles of staining, imaging, and efficient dye elution using a specialized elution buffer (e.g., 0.5 M L-Glycine, 1% SDS, pH 2.5) to achieve multiplexed imaging of 9 organelles in separate channels [16].

- Acquire images on a high-content microscope using a 20x or higher objective. Capture multiple fields per well to achieve sufficient cell counts.

Image Processing and Feature Extraction:

- Use an automated pipeline for illumination correction, quality control, and cell segmentation.

- Extract ~500-1000 morphological features (e.g., area, intensity, texture, shape) for each cell. This generates a high-dimensional data matrix.

- Perform plate normalization and select highly variable features (e.g., 886 features) for downstream analysis [17].

Data Deconvolution and Hit Identification:

- Deconvolution: Use a regularized linear regression framework to deconvolve the effect of each individual drug on the morphological features from the pooled screen data. This computational step infers single-perturbation effects [17].

- Phenotypic Clustering: Perform dimensionality reduction (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE) on the deconvolved phenotypic profiles. Cluster compounds based on profile similarity to group them by potential MoA.

- Hit Selection: Calculate an overall morphological effect size, such as the Mahalanobis Distance (MD), for each drug compared to controls. Prioritize hits with large MD values and those that cluster separately from known MoA classes for further investigation [17].

AI-Driven MoA Hypothesis Generation:

- Input the phenotypic profiles of novel hits into an AI platform (e.g., PhenoModel [19] or similar) trained on reference datasets.

- The platform compares the unknown profile against a database of profiles with known MoAs to generate predictive hypotheses.

- Integrate the phenotypic data with transcriptomic or proteomic data from the treated samples to strengthen the MoA hypothesis and identify potential signaling pathways or targets [14].

Experimental Validation:

- Confirm the phenotypic effects of top hits in a conventional, non-pooled screen.

- Employ orthogonal assays (e.g., biochemical, phosphoproteomics, siRNA knockdown) to validate the predicted molecular targets or pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a modern phenotypic screening campaign relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in MoA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dyes & Stains | Hoechst 33342, MitoTracker Deep Red, Phalloidin conjugates, Concanavalin A, LysoTracker [16] [17] | Label specific organelles to generate multiparametric morphological profiles for clustering and MoA prediction. |

| Live-Cell Reporters | ORACL (Optimal Reporter) cell lines with fluorescently tagged endogenous proteins [5] | Enable dynamic, live-cell imaging of pathway-specific responses to perturbations. |

| Specialized Buffers | CPP Elution Buffer (0.5 M Glycine, 1% SDS, pH 2.5) [16] | Enable iterative staining and elution cycles for highly multiplexed imaging in assays like CPP. |

| Complex Cell Models | Patient-derived organoids, Primary cells (e.g., PBMCs), 3D spheroids [17] [18] | Provide physiologically relevant context for phenotypic screening, improving clinical translatability. |

| Automation & Imaging | Acoustic liquid handlers (e.g., Echo 525), Automated microscopes, High-content analysis software [15] | Ensure precision, reproducibility, and scalability of screening workflows and image data acquisition. |

The convergence of high-content imaging, complex disease models, and artificial intelligence is fundamentally reshaping the paradigm of phenotypic drug discovery. This powerful synergy provides an unprecedentedly robust and scalable platform for unraveling novel mechanisms of action. By starting with biologically relevant phenotypes in sophisticated models, extracting deep insights via high-content imaging, and leveraging AI to find patterns within immense datasets, researchers can systematically deconvolve the complex actions of therapeutic compounds. This integrated approach moves the field beyond single-target hypotheses, enabling the discovery of polypharmacology and entirely new biology, thereby accelerating the delivery of transformative medicines to patients.

Advanced Workflows and Cutting-Edge Technologies in Modern Phenotypic Screening

The resurgence of phenotypic screening in drug discovery marks a significant shift from target-based approaches, offering the potential to identify first-in-class medicines by observing compound effects in complex biological systems without preconceived molecular hypotheses. [14] [3] However, the full potential of phenotypic screening is constrained by the physiological relevance of the cellular models employed. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, while valuable for their simplicity and throughput, suffer from critical limitations that impair their ability to predict human physiology and mechanism of action (MoA). [20] This technical guide examines the evolution from 2D cultures to advanced three-dimensional (3D) models—specifically organoids and organ-on-chip systems—framed within the context of MoA research. We provide a structured comparison of model systems, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of workflows to empower researchers in selecting appropriate models for deconvoluting complex biological mechanisms.

The Limitations of Conventional 2D Culture in MoA Studies

Despite over a century of contributions to fundamental biological discoveries, 2D monolayer cultures grown on rigid plastic or glass substrates present artificial microenvironments that elicit abnormal cellular responses. [20] The key disadvantages impacting MoA prediction include:

- Lack of physiological context: Cells in 2D cultures exhibit abnormal polarization, impaired cell-cell interactions, and limited cellular diversity, failing to recapitulate tissue-level architecture. [20]

- Absence of biomechanical cues: The static microenvironment lacks native mechanical forces such as fluid shear stress and cyclic strain, which significantly influence cell signaling and drug response. [21]

- Non-physiological nutrient and oxygen gradients: In 2D cultures, cells are exposed to uniform, often supraphysiological concentrations of oxygen and nutrients, unlike the complex gradients found in living tissues. [20]

- Reliance on transformed cell lines: 2D systems often utilize cancerous or immortalized cell lines with genetic and metabolic profiles that diverge significantly from primary human cells. [20]

These limitations manifest in poor translatability, where drug responses observed in 2D models frequently fail to predict clinical outcomes, highlighting the critical need for more physiologically relevant models in MoA research. [22]

Three-Dimensional Model Systems: Characteristics and Applications

Three-dimensional culture systems have emerged to bridge the gap between traditional 2D cultures and in vivo physiology. These models can be broadly categorized into spheroid/organoid cultures and microphysiological organ-on-chip systems, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and applications in phenotypic screening.

Table 1: Comparison of 3D Cell Culture Model Systems for MoA Research

| Model Characteristic | Spheroids & Organoids | Organ-on-Chip Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | Self-organizing 3D structures with multiple cell lineages; sophisticated architecture [22] [23] | Engineered tissue-tissue interfaces and organized cell layers mimicking organ microstructure [21] [20] |

| Microenvironmental Control | Limited control over biomechanical cues; self-directed differentiation [23] | Precise spatiotemporal control over biochemical and biophysical cues (flow, stretch) [22] [21] |

| Physiological Relevance | High cellular heterogeneity and phenotype fidelity; resemble developing organs [23] | Recapitulates tissue-level function with vascular perfusion and mechanical activity [21] [20] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Moderate to high throughput possible with standardized protocols [22] | Moderate throughput; increasing with multi-organ integration [23] |

| Primary MoA Applications | Disease modeling, developmental biology, personalized medicine [23] | Drug transport studies, toxicity testing, human pathophysiology [22] [20] |

| Key Limitations | Limited reproducibility, abnormal architecture, no perfusion or mechanical cues [20] | Higher complexity, cost, and technical expertise requirements [22] |

Spheroids and Organoids: Self-Organizing 3D Models

Organoids are 3D cell masses characterized by the presence of multiple organ-specific cell lineages and sophisticated 3D architecture that resembles the in vivo counterpart. [22] [23] These models are typically generated from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) or adult stem cells through processes that mimic embryonic development, where aggregates of PSCs undergo differentiation and morphogenesis when embedded in hydrogel scaffolds with appropriate exogenous factors. [23]

Key Advantages for MoA Research:

- Cellular heterogeneity: Organoids contain multiple cell types found in native tissues, enabling study of complex cell-cell interactions relevant to drug mechanisms. [23]

- Patient-specific modeling: Derived from human PSCs, organoids enable personalized medicine approaches and study of patient-specific disease mechanisms. [23]

- Developmental relevance: The self-organizing nature of organoids provides unique insights into developmental processes and disease pathogenesis. [23]

Organ-on-Chip Systems: Microengineered Physiological Models

Organ-on-chip technology comprises microfluidic devices containing living cells arranged to simulate organ-level physiology and functions. [22] These systems are fabricated using biocompatible materials, typically polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), with microchambers and channels that enable controlled fluid flow and application of mechanical cues. [21]

Key Advantages for MoA Research:

- Dynamic microenvironments: Microfluidic perfusion enables nutrient delivery, waste removal, and establishment of physiological gradients. [21] [20]

- Mechanical forces application: Systems can incorporate fluid shear stress, cyclic stretching (to mimic breathing or peristalsis), and other mechanical cues known to influence cell behavior and drug response. [21] [20]

- Tissue-tissue interfaces: Enable co-culture of different tissue types at physiologically relevant boundaries (e.g., epithelium and endothelium). [21]

- Integrated sensing: Capability for real-time, non-invasive monitoring of cellular responses through trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements and other biosensors. [23]

Experimental Protocols for 3D Model Implementation

Successful implementation of 3D models requires standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility and physiological relevance. Below are detailed methodologies for establishing key model systems for phenotypic screening applications.

Protocol 1: Formation of Spheroids and Aggregates in Microfluidic Systems

Principle: Leverage microfluidic confinement or non-adhesive surfaces to promote cell self-assembly into 3D spheroids through cell-cell adhesion and interactions. [22]

Materials:

- Microfluidic device with appropriate chamber design (e.g., droplet generators, microwells)

- Cell suspension (primary cells or cell lines, 1-5×10^6 cells/mL density)

- Appropriate culture medium with necessary growth factors and supplements

- Extracellular matrix (ECM) components if needed (e.g., Matrigel, collagen)

Procedure:

- Device preparation: Sterilize microfluidic device using UV light or 70% ethanol, then coat with appropriate ECM if required.

- Cell loading: Introduce cell suspension into microfluidic channels at optimized flow rates (typically 1-10 μL/min) to position cells in trapping regions or form droplets.

- Spheroid formation: Maintain culture under static or perfused conditions for 24-72 hours to allow cell aggregation and compaction.

- Culture maintenance: Exchange medium periodically (every 24-48 hours) via perfusion or manual exchange to maintain nutrient supply and waste removal.

- Characterization: Monitor spheroid formation using microscopy; assess viability and morphology through histology or live-dead staining.

Technical considerations: Cell density, flow rates, and chamber geometry critically impact spheroid size and uniformity. Optimization is required for each cell type. [22]

Protocol 2: Establishment of 3D Hydrogel Cultures in Organ-on-Chip Systems

Principle: Embed cells within natural or synthetic hydrogel matrices in microfluidic devices to provide biomechanical and biochemical cues mimicking native extracellular matrix. [22]

Materials:

- PDMS or polymer-based microfluidic device with appropriate chamber design

- Hydrogel precursor solution (e.g., collagen, fibrin, Matrigel, or synthetic polymers)

- Cell suspension at appropriate density (typically 5-20×10^6 cells/mL in hydrogel precursor)

- Polymerization agents if required (e.g., thrombin for fibrin, temperature control for Matrigel)

Procedure:

- Cell-hydrogel mixture preparation: Mix cell suspension with hydrogel precursor solution on ice to maintain liquid state until polymerization.

- Device loading: Introduce cell-laden hydrogel into microfluidic chambers using pipetting or controlled flow.

- Gel polymerization: Induce gelation using appropriate method (temperature change, pH adjustment, or chemical crosslinkers).

- Perfusion establishment: Connect device to perfusion system and begin medium flow at physiological shear stresses (typically 0.1-5 dyn/cm²).

- Culture maintenance: Maintain under continuous perfusion with periodic medium changes; monitor tissue formation and function.

- Endpoint analysis: Fix for histology, extract for molecular analysis, or perform live imaging as required.

Technical considerations: Hydrogel stiffness, composition, and degradability should be tailored to specific tissue type. Polymerization conditions must be compatible with cell viability. [22]

Protocol 3: Multi-Organoid Systems on Chip

Principle: Integrate multiple organoids in a microfluidic platform to simulate organ-organ interactions and systemic drug responses. [23]

Materials:

- Multi-compartment microfluidic device with interconnecting channels

- Multiple cell types for different organoids (e.g., hepatic, intestinal, neuronal)

- Cell-type specific differentiation media

- Perfusion system with programmable flow control

Procedure:

- Sequential organoid formation: Form individual organoids in separate chambers using protocols 1 or 2.

- System integration: Connect organoid chambers via microfluidic channels after organoid maturation (typically 3-7 days).

- Common medium establishment: Switch to a universal medium compatible with all organoids or use sequential perfusion with conditioning.

- Perfusion initiation: Begin recirculating flow at physiologically relevant rates to enable communication between compartments.

- Functional validation: Assess organoid-specific functions (e.g., albumin secretion for liver, barrier integrity for gut).

- Pharmacological testing: Introduce compounds and monitor responses across different organoids.

Technical considerations: Medium composition must support viability of all organ types. Flow rates should be optimized to ensure adequate nutrient delivery without excessive shear stress. [23]

Integration with Phenotypic Screening and MoA Deconvolution

Advanced 3D models gain maximum value when integrated with comprehensive MoA elucidation strategies. The convergence of high-content phenotypic screening with multi-omics technologies and artificial intelligence creates powerful frameworks for understanding compound mechanisms.

Phenotypic Screening in 3D Models

Phenotypic screening in 3D systems captures complex responses to genetic or chemical perturbations without presupposing molecular targets, offering unbiased insights into complex biology. [14] Key advancements enabling this approach include:

- High-content imaging: Automated microscopy coupled with 3D image analysis captures subtle, disease-relevant phenotypes in organoids and organ-chips. [14]

- Multiplexed assays: Simultaneous measurement of multiple phenotypic endpoints (morphology, viability, functional markers) provides rich datasets for MoA inference. [14]

- Single-cell technologies: Resolution of cellular heterogeneity within 3D models reveals subpopulation-specific drug responses. [14]

Computational MoA Elucidation Strategies

Once phenotypic hits are identified, computational approaches integrate 3D model data with prior knowledge to generate MoA hypotheses:

- Connectivity mapping: Compare gene expression signatures from treated 3D models to reference databases to identify compounds with similar mechanisms. [24] [25]

- Pathway enrichment analysis: Link differentially expressed genes or proteins to biological pathways using annotation resources. [24]

- Multi-omics integration: Combine transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data from 3D models to obtain systems-level views of compound actions. [14] [24]

- Morphological profiling: Use high-content imaging data to generate quantitative phenotypic profiles that can be connected to known MoAs through reference databases. [14]

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Model-Based MoA Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Matrices | Matrigel, collagen, fibrin, hyaluronic acid, PEG-based synthetics [22] | Provide 3D scaffolding with biomechanical and biochemical cues for tissue-specific culture |

| Microfluidic Devices | PDMS chips, 3D printed platforms, commercial organ-chips (e.g., Emulate) [23] [20] | Enable controlled perfusion, mechanical stimulation, and tissue-tissue interfaces |

| Stem Cell Sources | Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), adult stem cells, organ-specific progenitors [23] | Generate patient-specific models and recapitulate developmental processes |

| Differentiation Factors | WNT agonists, BMP inhibitors, FGFs, organ-specific morphogens [23] | Direct stem cell differentiation toward specific lineages and tissue types |

| Characterization Tools | Live-cell imaging dyes, viability assays, metabolic activity probes, TEER electrodes [23] [20] | Assess tissue formation, function, and compound effects in real-time |

| Omics Technologies | Single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, mass spectrometry proteomics [14] [24] | Enable comprehensive molecular profiling for deep MoA elucidation |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Effective implementation of 3D models requires understanding the sequential workflows for model establishment and the logical relationships between model selection and MoA research goals. The following diagrams provide visual guidance for these processes.

3D Model Establishment Workflow

Model Selection Logic for MoA Research

The field of 3D cell culture for MoA research is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends promising to enhance physiological relevance and screening throughput. Key future directions include:

- Convergence of organoid and organ-chip technologies: Integrating the cellular complexity of organoids with the environmental control of organ-chips creates human organoid-on-chip systems with enhanced physiological relevance. [23]

- Advanced biosensing and real-time monitoring: Incorporation of miniaturized sensors within 3D models enables continuous monitoring of metabolic activity, barrier function, and contractility without disrupting culture integrity. [23]

- 3D bioprinting for standardized model production: Bioprinting technologies enable precise deposition of cells and matrices to create reproducible, complex tissue architectures with defined cellular composition. [23]

- AI-powered MoA prediction platforms: Advanced machine learning algorithms that integrate multimodal data from 3D models (morphology, gene expression, functional metrics) to generate testable MoA hypotheses. [14] [26]

In conclusion, the strategic selection of 3D cell culture models—from organoids to organ-chips—represents a critical advancement in phenotypic screening for MoA research. By carefully matching model capabilities to specific research questions, scientists can leverage these physiologically relevant systems to deconvolute complex drug mechanisms, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics with improved clinical translatability.

High-content imaging, particularly the Cell Painting assay, represents a transformative approach in phenotypic screening for novel Mechanism of Action (MoA) research. This technical guide details how this multiplexed morphological profiling method captures holistic cellular phenotypes by simultaneously labeling multiple organelles, generating rich, high-dimensional data that enables the functional classification of compounds and genetic perturbations. By providing unbiased, system-wide readouts of cellular states, the assay effectively illuminates phenotypic "dark space," allowing researchers to group unknown compounds with known MoA candidates and deconvolve novel biological activities in drug discovery [27] [28].