Overcoming Morphological Profiling Data Analysis Challenges: From Classical Features to Self-Supervised Learning

Morphological profiling through high-content imaging, particularly the Cell Painting assay, has emerged as a powerful technology for drug discovery and functional genomics.

Overcoming Morphological Profiling Data Analysis Challenges: From Classical Features to Self-Supervised Learning

Abstract

Morphological profiling through high-content imaging, particularly the Cell Painting assay, has emerged as a powerful technology for drug discovery and functional genomics. This article addresses the key computational challenges in analyzing large-scale morphological data, covering the complete workflow from image processing to biological interpretation. We explore foundational concepts of image-based profiling, compare traditional feature extraction methods with emerging self-supervised learning approaches, provide solutions for common troubleshooting scenarios, and present validation frameworks using recently released benchmark datasets. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review synthesizes current best practices and technological advances that are transforming how we extract biological insights from cellular morphology.

The Fundamentals of Image-Based Cell Profiling: Workflows, Applications, and Core Principles

This technical support resource details the Cell Painting assay, a high-content morphological profiling technique that uses multiplexed fluorescent dyes to reveal cellular components. The assay extracts hundreds of morphological features from images to create profiles for comparing biological samples, enabling applications in drug discovery, functional genomics, and disease modeling [1] [2]. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers facing data analysis challenges in morphological profiling.

Core Staining Panel and Detection

The standard Cell Painting assay uses six fluorescent dyes across five imaging channels to label eight cellular components [1] [2].

Table: Standard Cell Painting Dye Configuration

| Cellular Component | Fluorescent Dye | Staining Type |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Hoechst 33342 | Fixed or live cells |

| Mitochondria | MitoTracker Deep Red | Live cells |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | Fixed cells |

| Nucleoli & Cytoplasmic RNA | SYTO 14 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain | Fixed cells |

| F-actin cytoskeleton | Phalloidin, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate | Fixed cells |

| Golgi apparatus & Plasma membrane | Wheat germ agglutinin, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate | Fixed cells |

Experimental Workflow

The general workflow for a Cell Painting assay follows a series of standardized steps, from cell plating to data analysis [2].

Detailed Protocol Methodology

- Cell Plating and Perturbation: Plate cells in multi-well plates (e.g., 384-well format) and treat with chemical compounds, RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9, or other genetic perturbations [1] [2]. The choice of cell type (e.g., U2OS, A549, Hep G2) and perturbation duration are critical variables that require optimization [3] [4].

- Staining and Fixation: Perform the multiplexed staining procedure. The protocol involves both live-cell staining (e.g., MitoTracker) and staining after fixation [1] [5]. Incubation times for probes can be titrated (from 2 to 30 minutes) to optimize intensity [6].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images on a high-content or high-throughput confocal microscope. The ImageXpress Confocal HT.ai and CellInsight CX7 LZR Pro Platform are examples of systems used [2] [5]. Ensure consistent imaging settings across plates and batches to minimize technical variation.

- Image Analysis and Feature Extraction: Use automated image analysis software (e.g., MetaXpress, IN Carta, or CellProfiler) to identify individual cells and their components [1] [2]. These tools extract ~1,500 morphological features per cell, including measurements of size, shape, texture, intensity, and spatial relationships between structures [1].

- Data Analysis and Profiling: Perform data normalization, batch correction, and dimensionality reduction. Aggregate single-cell data to create well-level profiles and use similarity metrics (e.g., cosine similarity) to compare perturbations and identify matches [4].

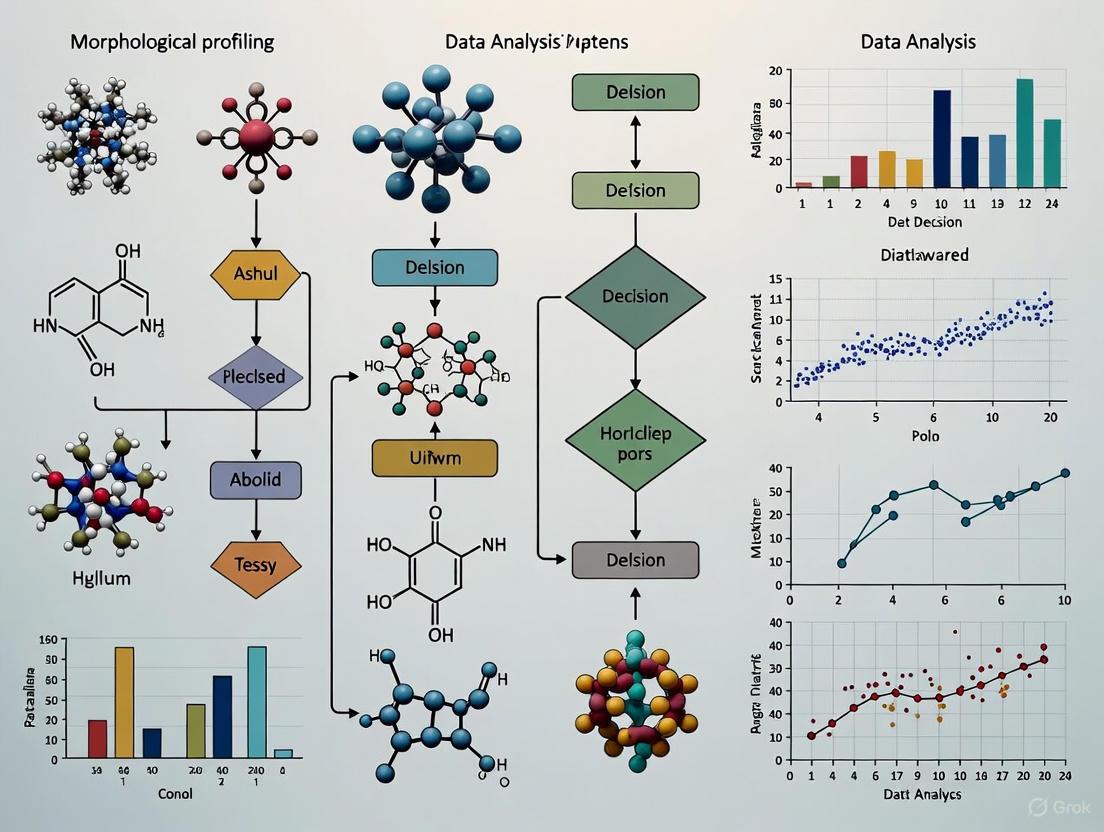

Data Analysis Pathway

The data processing pipeline transforms raw images into comparable morphological profiles.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Low or Uneven Staining Intensity

- Problem: Sub-optimal signal from cell painting markers, leading to poor segmentation.

- Solution:

- Titrate the concentration of off-instrument applied probes, such as those for cell membrane and nucleus [6].

- Optimize incubation times for probes. Test a range from 2 minutes to 30 minutes to find the ideal signal intensity [6].

- For non-specific binding or charge-related issues, use a signal enhancer like Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer to block non-specific interactions [7].

Excessive Photobleaching

- Problem: Fluorescent signals fade quickly during imaging or storage.

- Solution:

- Use an appropriate antifade reagent. For live-cell imaging, use ProLong Live Antifade Reagent. For long-term storage of fixed samples, use a hardening mountant like ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant [7].

- Choose more photostable dyes, such as Alexa Fluor dyes [7].

- Reduce light exposure by lowering laser power, using neutral density filters, and minimizing viewing time [7].

High Background Fluorescence

- Problem: Poor signal-to-noise ratio due to high background.

- Solution:

- Ensure you are using the correct excitation and detection wavelengths for your dyes [7].

- Optimize dye concentration and staining time using control samples [7].

- For live-cell systems, wash out unreacted dye or add a background suppressor like BackDrop Suppressor ReadyProbes Reagent [7].

- Check for endogenous autofluorescence in unstained controls. If present, wash samples with sodium borohydride prior to blocking and labeling [7].

Bubbles in Mounting Medium

- Problem: Bubbles trapped in the mounting medium during sample preparation.

- Solution:

- Degas the mounting medium by centrifuging the aliquot or placing the entire vial under a vacuum for 10-20 minutes before use [7].

- When applying the coverslip, lower it at a slight angle gently to avoid trapping air [7].

- For tissue sections, degas the sections while submerged in buffer to remove air trapped within the tissue [7].

Objective Lens Hitting Sample or Vessel Holder

- Problem: The objective lens makes contact with the sample container during focusing.

- Solution:

- Calibrate objectives using the system's calibration slide [7].

- Ensure you are using the correct objective type (e.g., Long-Working Distance (LWD) for imaging through plasticware or slides, not Coverslip-Corrected (CC) objectives) [7].

- Manually focus the objective upward to touch the sample bottom, then slowly move away for fine focusing, especially with high magnification and oil immersion objectives [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Invinrogen Image-iT Cell Painting Kit | A curated kit containing six reagents for standard Cell Painting staining [5]. |

| Hoechst 33342 | A cell-permeable blue fluorescent dye that stains DNA in the nucleus [2]. |

| MitoTracker Deep Red FM | A far-red fluorescent dye that stains mitochondria in live cells [2]. |

| Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | A green fluorescent lectin that binds to glycoproteins in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi [1] [2]. |

| Phalloidin, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate | An orange-red fluorescent dye that selectively binds to F-actin in the cytoskeleton [2]. |

| Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA), Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate | An orange fluorescent lectin that stains the Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane [1] [2]. |

| SYTO 14 | A green fluorescent nucleic acid stain that labels nucleoli and cytoplasmic RNA [2]. |

| ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant | A hardening mounting medium that retards photobleaching in fixed samples for long-term storage [7]. |

| Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer | A reagent used to block non-specific binding of fluorescent conjugates to cellular components [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is morphological profiling and why is it important in drug discovery? Morphological profiling is a high-content, image-based method that quantitatively captures changes in cell morphology across various cellular compartments. It enables the rapid prediction of compound bioactivity and mechanisms of action (MOA) by analyzing induced phenotypic changes. This is crucial in drug discovery for identifying drug targets, predicting off-target effects, and grouping compounds with similar biological impacts, thereby accelerating the research pipeline [3] [4] [8].

2. What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative data in this workflow? In the context of image-based profiling, the raw images (pixels) represent qualitative, unstructured data. Through feature extraction and analysis, these are transformed into quantitative, structured data. This quantitative data consists of measurable numerical features (size, shape, intensity, texture) that form the morphological profile, allowing for statistical comparison and pattern recognition [9].

3. Why is a unified semantic layer important in this workflow? A unified semantic layer creates a consistent source of truth by standardizing data definitions and metrics across different analytical workflows. It ensures that all researchers and systems (e.g., analytics, machine learning, data science) work with accurate, cohesive data. This breaks down data silos, enhances collaboration, and ensures decision-making is based on consistent and reliable information, which is critical for reproducible research [10].

4. How can we address the challenge of poor data quality in morphological profiles? Data quality is paramount. Strategies include:

- Robust Data Governance: Implementing policies and standards for data collection, processing, and management [10] [11].

- Extensive Assay Optimization: Prior to large-scale screening, optimize protocols to achieve high data quality and reproducibility, even across different imaging sites [3].

- Data Cleaning and Validation: Processes must include removing duplicates, handling missing values, standardizing formats, and validating the cleaned data to ensure accuracy and consistency [12] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Reproducibility of Morphological Profiles Across Experimental Replicates

Problem: Profiles from technical or biological replicates of the same perturbation show high variability and low similarity, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signal from noise.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Image Quality: Check for technical artifacts like out-of-focus images, uneven illumination, or background fluorescence. | High-quality, clear images with consistent staining and illumination across all wells and plates. |

| 2 | Check Plate Layout Effects: Analyze if profiles cluster by well position rather than treatment. Implement plate normalization techniques to correct for systematic row/column biases. | Treatment replicates cluster together in similarity analyses, regardless of their position on the plate. |

| 3 | Validate Replicate Concordance: Use metrics like average precision to quantify how well replicates of the same perturbation retrieve each other against a background of negative controls. | A high fraction of perturbations should be statistically distinguishable from controls (e.g., q-value < 0.05) [4]. |

| 4 | Review Assay Protocol: Ensure consistency in cell culture, perturbation timing, staining protocols, and imaging settings. Document any deviations rigorously. | A standardized and documented protocol leading to highly reproducible profiles across different operators and days. |

Issue 2: Failure to Match Chemical and Genetic Perturbations Targeting the Same Gene

Problem: Computational strategies fail to retrieve or group known compound-gene pairs (where the compound targets the gene's product) based on their morphological profiles.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benchmark Profile Quality: Confirm that the perturbations produce detectable and robust phenotypes using the "perturbation detection" benchmark. Without a strong signal, matching is impossible [4]. | Both chemical and genetic perturbations show significant morphological changes compared to negative controls. |

| 2 | Evaluate Similarity Metric: Test different similarity metrics (e.g., cosine similarity, correlation) and data transformation methods. The directionality of correlation (positive or negative) must be considered. | The chosen metric successfully groups positive controls (e.g., two different CRISPR guides targeting the same gene). |

| 3 | Incorporate Multiple Views: Utilize data from different cell types or time points if available. A match may only be apparent under specific biological conditions [4]. | Compound-gene pairs show higher similarity in a specific cell line or at a specific time point post-treatment. |

| 4 | Leverage Advanced Representations: Explore deep learning and representation learning methods that can automatically learn features directly from image pixels, which may capture more nuanced biological relationships than hand-engineered features [4]. | Improved retrieval of known compound-gene pairs compared to classical feature-based methods. |

Issue 3: Low Discrimination Power in Profile Analysis

Problem: The extracted morphological profiles cannot reliably distinguish between different perturbation mechanisms or identify unique phenotypes.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Assess Feature Selection: Ensure the feature set is comprehensive and captures diverse morphological aspects. Consider incorporating features learned by deep learning models. | A rich set of features that captures variations in size, shape, intensity, and texture across all stained cellular compartments. |

| 2 | Optimize Dimensionality Reduction: Re-evaluate parameters for techniques like PCA or UMAP. Overly aggressive reduction can collapse distinct phenotypes. | Clear, separated clusters in 2D visualization corresponding to perturbations with different known mechanisms of action. |

| 3 | Validate with Controls: Include a diverse set of reference compounds with well-annotated mechanisms of action (MOAs) in your screen. | Profiles cluster meaningfully by MOA, and positive controls are reliably retrieved. |

| 4 | Implement Explainable AI (XAI): Use XAI techniques to understand which features or image regions are driving profile differences, helping to build trust and identify potential areas for assay improvement [10]. | Clear, interpretable insights into the morphological changes that define specific phenotypic classes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and computational tools essential for a morphological profiling experiment.

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | Multiplexed fluorescent dye sets for staining major cellular compartments (nucleus, nucleoli, cytoplasm, Golgi/ER, actin cytoskeleton, plasma membrane). Provides a comprehensive view of cell morphology [4]. |

| High-Throughput Confocal Microscopes | Automated imaging systems that generate high-resolution, multi-channel images of stained cells in multi-well plates, enabling large-scale screening. |

| JUMP Cell Painting Consortium CPJUMP1 Dataset | A publicly available benchmark dataset containing ~3 million images from chemical and genetic perturbations. Used for method development and validation [4]. |

| Open Data Format (Apache Parquet/Iceberg) | Columnar storage formats that enable efficient querying and analysis of large feature data tables, facilitate data sharing, and help avoid vendor lock-in [10]. |

| RAG-Powered AI Tools | AI systems using Retrieval-Augmented Generation. They are integrated into data platforms to allow users to query proprietary morphological profile data using natural language, unlocking insights from structured and unstructured data [10]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Frameworks | Software tools that help explain the reasoning behind AI-driven analysis of morphological profiles, building trust and meeting regulatory demands by showing the 'why' behind decisions [10]. |

Standard Data Analysis Workflow: From Images to Profiles

The diagram below illustrates the eight critical stages of transforming raw cellular images into quantitative morphological profiles, integrating both established practices and modern data lifecycle management principles [11] [13].

Data Analysis Workflow: Eight Key Stages

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Workflow Stages

Stage 1 & 2: Image Acquisition, Data Collection & Aggregation

- Methodology: Cells (e.g., U2OS, A549, Hep G2) are seeded in multi-well plates, treated with perturbations (chemical compounds or genetic tools like CRISPR-Cas9), and stained using the Cell Painting protocol [4]. Imaging is performed using high-throughput confocal microscopes across multiple sites, requiring extensive assay optimization to ensure high cross-site data quality and reproducibility [3] [4].

- Key Considerations: Standardize imaging settings (exposure time, laser power) across plates and sites. Implement careful plate layout planning, randomizing treatments and including adequate positive/negative controls to mitigate batch effects [4].

Stage 3: Data Processing & Feature Extraction

- Methodology: This stage involves classical image segmentation to identify individual cells and feature extraction using software that quantifies morphological aspects. The process includes data cleaning (handling missing data, removing duplicates) and transformation to create a unified dataset [4] [13].

- Key Considerations: "Hand-engineered" features (size, shape, texture) are the current field standard. However, there is active exploration of deep learning methods to learn features directly from pixels, which may capture more subtle biological phenomena [4]. This step lays the foundation for all subsequent analysis, making data quality and validation critical [13].

Stage 5: Profiling & Data Analysis

- Methodology: The goal is to derive a representation where biologically similar samples are close. This involves:

- Normalization & Batch Correction: Account for technical variability.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use PCA or UMAP to visualize and explore profile relationships.

- Similarity Measurement: Calculate cosine similarity between aggregated profiles.

- Benchmarking: Evaluate analysis pipelines using tasks like "perturbation detection" (identifying active treatments) and "perturbation matching" (finding similar profiles) [4].

- Key Considerations: The analysis must be robust against plate layout effects. The success of matching chemical and genetic perturbations can be challenging and depends on the strength and specificity of the induced phenotype [4].

Stage 7 & 8: Interpretation, Insight Generation & Actionable Recommendations

- Methodology: Interpret patterns and correlations to derive meaningful biological insights, such as predicting a compound's Mechanism of Action (MoA) or identifying novel gene functions [4] [13]. This involves reviewing analytical objectives, seeking explanations for observed patterns, and validating insights against original goals.

- Key Considerations: Provide actionable recommendations based on insights, such as prioritizing a compound for further testing or suggesting a new hypothesis for a gene's function. Clearly articulate how these recommendations align with overarching research goals [13].

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in navigating the common computational and experimental challenges encountered in two key areas of modern drug discovery: Mechanism of Action (MoA) identification and toxicity prediction. The guidance provided is framed within a research thesis focusing on overcoming morphological profiling data analysis challenges, leveraging high-content imaging and artificial intelligence (AI) to deconvolve complex biological data into actionable insights.

Troubleshooting Guides

Mechanism of Action Identification

Problem: High-Content Screen Shows High Phenotypic Variability, Compering MoA Classification A phenotypic screen using a Cell Painting assay returns images with high cell-to-cell variability, making it difficult to cluster compounds with similar MoAs reliably.

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent Cell Culture Conditions

- Solution: Standardize passage number, confluence at time of treatment, and media composition. Implement strict quality control logs for serum lots and cell line authentication [14].

- Potential Cause 2: Suboptimal Image Acquisition Parameters

- Solution: Calibrate microscope lasers and cameras regularly. For live-cell imaging, optimize frequency and duration of imaging to minimize phototoxicity, which can itself induce phenotypic changes [14].

- Potential Cause 3: Inefficient Feature Extraction and Normalization

- Solution: Use standardized image analysis pipelines like CellProfiler to extract morphological features. Apply batch correction algorithms to normalize data across different experimental runs and imaging sites [8].

Problem: Inability to Distinguish Between Primary On-Target Effects and Off-Target Toxicity After identifying a phenotypic hit, follow-up experiments fail to confirm the suspected molecular target, suggesting the observed phenotype may be due to off-target effects.

- Potential Cause 1: Limitations of a Single Target Identification Method

- Solution: Employ a combination of orthogonal target deconvolution methods. Do not rely solely on one technique. Combine biochemical methods (e.g., affinity purification) with genetic interaction methods (e.g., CRISPR-based knockouts) and computational inference for cross-validation [15].

- Potential Cause 2: Lead Compound Lacks Sufficient Selectivity

Toxicity Prediction

Problem: AI Model for Hepatotoxicity Prediction Shows Poor Generalization to New Chemical Scaffolds A machine learning model trained on existing toxicity data performs well on test compounds but fails to predict the toxicity of novel chemotypes.

- Potential Cause 1: Training Data is Not Representative of Chemical Space

- Solution: Augment training data with diverse public and proprietary toxicology resources. Use databases like TOXRIC, ChEMBL, and DrugBank, which aggregate toxicity and bioactivity data from numerous sources [17].

- Potential Cause 2: Model Relies on Overly Simplistic Molecular Descriptors

- Solution: Implement advanced deep learning architectures that can learn directly from molecular structures (e.g., graphs or SMILES strings) or utilize multimodal data fusion, incorporating both structural and high-content imaging data [17].

- Potential Cause 3: Species Extrapolation Error

Problem: In Vitro Cytotoxicity Data Does Not Correlate with In Vivo Organ-Specific Toxicity Findings A compound shows minimal cytotoxicity in standard in vitro assays but causes specific organ damage in animal models.

- Potential Cause 1: The In Vitro Model Lacks Physiological Complexity

- Solution: Move from simple 2D monocultures to more complex in vitro models, such as 3D organoids or co-cultures, which can better capture cell-cell interactions and tissue-level responses [14].

- Potential Cause 2: The Toxicity is Metabolite-Mediated

- Solution: Incorporate metabolically competent systems, such as hepatocytes or systems that express key cytochrome P450 enzymes, to assess the toxicity of both the parent compound and its metabolites [17].

- Potential Cause 3: The Assay is Measuring the Wrong Endpoint

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between target-based and phenotypic screening approaches in MoA identification? A1: Target-based screening is a reverse chemical genetics approach. It starts with a purified protein target hypothesized to be disease-relevant and screens for compounds that modulate its activity [18] [15]. In contrast, phenotypic screening is a forward chemical genetics approach. It starts by screening for compounds that induce a desired phenotypic change in a cell or organism, without preconceived notions of the target, requiring subsequent target deconvolution [15]. Phenotypic screens can discover novel therapeutic targets and MoAs.

Q2: When during drug discovery should we invest in elucidating a compound's precise MoA? A2: There is no one-size-fits-all answer. The decision should consider the disease complexity, existence of standard-of-care, and project resources. While MoA knowledge is not strictly required for FDA approval, it greatly benefits lead optimization, understanding clinical efficacy, and managing potential side effects. For programs arising from phenotypic screens, MoA studies are essential and often occur after confirmation of cellular efficacy [18].

Q3: How can morphological profiling from assays like Cell Painting predict toxicity? A3: The Cell Painting assay uses multiplexed fluorescent dyes to label key cellular components (e.g., nucleus, actin, mitochondria). Treating cells with a compound generates a morphological profile—a high-dimensional vector of quantitative features describing cell shape, texture, and organelle organization [8]. Compounds with known toxicity profiles produce characteristic morphological "fingerprints." By comparing a new compound's profile to these references using machine learning, one can predict its potential toxicity, such as mitochondrial dysfunction or cytoskeletal damage, before more costly in vivo studies [14] [8].

Q4: What are Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) in the context of morphological cell analysis? A4: CQAs are a minimal set of standardized, quantitative morphological measurands (e.g., related to the nucleus, actin cytoskeleton, or mitochondria) that are traceable to standardized units and are critically linked to cell bioactivity, identity, and health [14]. Defining CQAs is a goal of the cell metrology community to reduce data variability and improve comparability across different labs and analytical platforms.

Q5: Can computational methods alone identify a small molecule's target? A5: Computational methods, particularly structure-based approaches like Inverse Virtual Screening (IVS), are powerful for generating target hypotheses. IVS computationally "screens" a compound against a large library of protein structures to predict potential binding partners [16]. However, these in silico predictions are not definitive. They significantly reduce the time and cost of target identification by prioritizing the most likely targets, but the hypotheses must be experimentally validated through biochemical or genetic methods [15] [16].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Methodology: Cell Painting Assay for Morphological Profiling

The following protocol is adapted for generating high-quality data for MoA classification and toxicity prediction [8].

- Cell Seeding and Culture: Seed appropriate cell lines (e.g., U2 OS or Hep G2) into multi-well plates at a pre-optimized density to achieve 50-70% confluence at the time of staining.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with the compound of interest alongside appropriate controls (vehicle control, benchmark compounds with known MoA/toxicity). Include a range of concentrations and treatment durations to capture dose- and time-dependent effects.

- Staining and Fixation:

- Fix cells with paraformaldehyde.

- Permeabilize cells with Triton X-100.

- Stain with the multiplexed dye cocktail:

- Nuclei: Hoechst 33342 (DNA)

- Nucleoli and Cytoplasmic RNA: SYTO 14 (RNA)

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Concanavalin A (ConA) conjugated to a fluorophore

- Mitochondria: MitoTracker Deep Red

- Actin Cytoskeleton: Phalloidin conjugated to a fluorophore

- Golgi Apparatus: A suitable antibody or dye (optional, depending on the panel)

- Image Acquisition: Image plates using a high-throughput confocal microscope. Acquire images from multiple sites per well and across all fluorescent channels using a 20x or higher magnification objective. Ensure exposure times are set to avoid pixel saturation.

- Image Analysis and Feature Extraction:

- Use CellProfiler or similar software to segment cells and identify individual cellular compartments.

- Extract hundreds of morphological features (e.g., area, shape, texture, intensity, neighbor relationships) for each compartment per cell.

- Data Analysis and Profiling:

- Aggregate single-cell data and normalize to plate controls.

- Use dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) and clustering algorithms to group compounds with similar morphological profiles, inferring potential MoA or toxicity.

Table 1: Common Morphological Features as Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) for Cell Health Assessment [14]

| Cellular Compartment | Measurand (CQA) | Description | Link to Bioactivity/Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Nuclear Area | 2D area of the nucleus | Changes indicate cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or genotoxic stress. |

| Nucleus | Nuclear Shape Index | Measures roundness (1.0 = perfect circle) | Irregularity can indicate apoptosis or nuclear envelope defects. |

| Actin Cytoskeleton | Actin Fiber Density | Measurement of actin filament bundling | Loss of density indicates disruption of cytoskeletal integrity. |

| Mitochondria | Mitochondrial Network Length | Total length of mitochondrial structures | Fragmentation is linked to apoptosis; elongation can indicate stress. |

| Cell Membrane | Cell Spread Area | Total area occupied by the cell | Reduction can be a marker of cell rounding and detachment in toxicity. |

Table 2: Publicly Available Databases for Toxicity Prediction Model Development [17]

| Database Name | Data Content & Scale | Primary Application in Toxicity Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| TOXRIC | Comprehensive toxicity data (acute, chronic, carcinogenicity) | Training data for various toxicity endpoint models. |

| ChEMBL | Manually curated bioactivity data, ADMET properties | Source for compound structures and associated toxicity data. |

| DrugBank | Drug data with target, mechanism, and adverse reaction info | Linking compound structure to clinical toxicity observations. |

| PubChem | Massive repository of chemical structures and bioassays | Large-scale data source for model training and validation. |

| FAERS | Database of post-market adverse event reports | Identifying clinical toxicity signals for marketed drugs. |

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

MoA Identification Workflow

AI-Driven Toxicity Prediction Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for MoA and Toxicity Studies

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CellProfiler | Software | Open-source platform for automated analysis of cellular images; extracts morphological features for profiling [14]. |

| TOXRIC / ChEMBL | Database | Provides large-scale, curated toxicity and bioactivity data for training and validating computational models [17]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Libraries | Genetic Tool | Enables genome-wide screens to identify genes that confer sensitivity or resistance to a compound, informing MoA [15]. |

| Affinity Beads (e.g., Agarose/NHS) | Biochemical Reagent | For immobilizing compounds to create affinity matrices for pull-down assays to identify direct protein targets [15]. |

| Multiplexed Fluorescent Dyes (Cell Painting Kit) | Staining Reagent | Allows simultaneous labeling of multiple organelles to generate a comprehensive morphological snapshot of the cell [8]. |

Image-based cell profiling is a high-throughput methodology that quantifies the effects of chemical and genetic perturbations on cells by capturing a breadth of morphological changes via microscopy [19]. This approach transforms images into rich, high-dimensional morphological profiles, enabling the comparison of treatments to identify biologically relevant similarities and differences [20]. The foundation of this profiling lies in the extraction and analysis of four core categories of morphological features: Shape, Intensity, Texture, and Spatial Relationships [20]. This technical support guide addresses common challenges researchers encounter when working with these feature categories during their profiling experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Data Analysis Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution | Key References/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Segmentation Accuracy [20] | - Inhomogeneous illumination [20]- Suboptimal algorithm parameters [20] | - Apply retrospective multi-image illumination correction [20]- Use machine learning-based segmentation (e.g., Ilastik) for highly variable cell types [20] | - Model-based approach (CellProfiler) [20]- Machine learning approach (Ilastik) [20] |

| Weak or Unreiable Morphological Profiles [19] | - High dimensionality and noise in features [19]- Technical artifacts (e.g., batch effects) [19] | - Perform feature normalization and selection (e.g., remove low-variance/high-correlation features) [19]- Use hierarchical clustering (e.g., Morpheus) to inspect for batch effects [19] | - Pycytominer for data normalization/aggregation [19]- Morpheus software for matrix visualization & clustering [19] |

| Difficulty Interpreting Biological Meaning of Profiles [19] | - Complex phenotypes involving many features [19]- Lack of visual connection to raw data [19] | - Identify "driving features" that contribute most to profile differences [19]- Correlate profiles with representative single-cell images [19] | - Morpheus heatmaps for feature exploration [19]- Custom Python scripts for single-cell visualization [19] |

| Low Contrast Between Key Features and Background [21] | - Insufficient color contrast ratios in visualizations [21] | - Ensure a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio for chart elements and 4.5:1 for text [21]- Use dark themes to access a wider array of compliant color shades [21] | - WCAG 2.1 (Level AA) guidelines [21]- Color contrast checker tools [21] |

Experimental Workflow for Morphological Profiling

The following diagram outlines the key steps for generating and analyzing morphological profiles, from image acquisition to biological interpretation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key advantages of using morphological features for profiling over other methods?

Morphological analysis is particularly well-suited for texture description and capturing complex phenotypes because it excels at exploiting spatial relationships among pixels and possesses numerous tools for extracting size and shape information [22]. Furthermore, in contrast to methods like difference statistics or Fourier transforms, which describe a texture process only up to second-order characteristics, morphological methods can capture higher-order properties of spatial random processes [22]. This allows profiling to capture unexpected behaviors of the cell system without being limited to pre-defined hypotheses [23].

How can we handle the challenge of high-dimensional feature data?

A standard practice is to perform data normalization and aggregation. For example, single-cell profiles are often aggregated into population-averaged profiles for each sample well [19] [23]. Subsequent feature selection steps are crucial, including excluding features with low variance or high correlation to another feature [19]. Tools like pycytominer are specifically designed for this normalization and feature selection process in morphological profiling data [19].

Our profiles are technically robust but biologically uninterpretable. What can we do?

This is a common bottleneck. We recommend a two-pronged approach:

- Exploratory Data Analysis: Use tools like Morpheus to create heatmaps and perform hierarchical clustering. This allows you to visualize correlations between samples and identify groups of perturbations with similar profiles, which can be linked to known mechanisms of action [19].

- Image Visualization: Go back to the images. Create visualizations of representative single cells from different treatments to understand how changes in features are reflected in the actual cell morphology. This helps build intuition about the biological meaning behind the numerical profiles [19].

What are some best practices for visualizing this data accessibly?

When creating visualizations like charts:

- Color and Contrast: Do not rely on color alone. Use a second encoding such as shapes, patterns, or text labels to convey meaning. Ensure all graphics achieve a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio with neighboring elements [24] [21].

- Text and Icons: Integrate text labels directly into graphs where possible, or use clear, unambiguous icons. This benefits all users and is essential for those with color vision deficiencies [21].

- Focus and Simplicity: Use borders that meet contrast requirements while employing lighter fills to direct focus to the most important metrics, improving glanceability without sacrificing accessibility [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Morphological Profiling | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay Reagents [19] [23] | A standardized set of fluorescent dyes to stain eight cellular components (actin, Golgi, nucleus, etc.), enabling unbiased morphological capture. | Uses six fluorescent dyes imaged across five channels [23]. |

| CellProfiler Software [19] [20] | Open-source software for segmenting cells and performing feature extraction on microscopy images. | Extracts thousands of features per cell for shape, intensity, texture, and spatial relationships [19] [20]. |

| Pycytominer [19] | A Python package for normalizing, aggregating, and performing feature selection on single-cell data from CellProfiler. | Used to normalize features to controls and aggregate single-cell profiles into well-level profiles [19]. |

| Morpheus [19] | A free, web-based software from the Broad Institute for matrix visualization, clustering, and analysis of profiling data. | Helps explore sample similarities and identify features driving profile differences via heatmaps [19]. |

Data Analysis Pathway in Morphological Profiling

This diagram illustrates the computational pathway from raw images to biological insights, highlighting the role of key software tools.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers utilizing public morphological profiling resources. These resources are designed to help you overcome common challenges in data analysis and experimental protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Resource Questions

What is the JUMP-Cell Painting Consortium? The JUMP-Cell Painting Consortium was a collaborative effort that created a large-scale, public Cell Painting dataset to validate and scale up image-based drug discovery strategies. This resource helps in determining the mechanism of action of potential therapeutics and provides an unprecedented public data set for the community [25].

What is EU-OPENSCREEN? EU-OPENSCREEN is a non-profit European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC) that provides academic researchers and companies with access to compound screening, medicinal chemistry, and data resources to advance chemical biology and early drug discovery research. Its network includes 30 partner sites across Europe [26].

Can I still join the JUMP-Cell Painting Consortium? No, the original JUMP-Cell Painting Consortium has completed its work. However, you can explore new related consortia such as OASIS (focused on integrated safety assessment) or VISTA (focused on variant integration for screening therapeutic approaches) [27].

How can I access the data from these resources?

- JUMP-Cell Painting: Data and code are publicly available. You can explore it via the JUMP Cell Painting Hub, which offers interactive tools without programming, as well as guides for data fetching and analysis [28].

- EU-OPENSCREEN: The organization provides an open-access chemical biology database with millions of data points, which is available for screening and machine learning applications [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Data Analysis Issues

How can I improve the quality of my cell images for profiling? A major factor is illumination correction, which addresses uneven background lighting. For high-throughput quantitative profiling, a retrospective multi-image method is recommended. This involves building a correction function from all images in an experiment batch (e.g., per plate) for more robust results compared to single-image or prospective methods [20].

My segmentation results are poor for a complex cell type. What can I do? While model-based segmentation (e.g., using thresholding and watersheds) is common for standard fluorescence images, consider a machine-learning-based approach (e.g., with Ilastik) for highly variable cell types or tissues. This method requires manual pixel labeling for training but can handle more difficult segmentation tasks effectively [20].

What features should I extract for an unbiased morphological profile? To capture a comprehensive view of cell state, extract a wide variety of features [20]:

- Shape features: Area, perimeter, and roundness of cellular compartments.

- Intensity-based features: Mean and maximum intensity within compartments.

- Texture features: Metrics that quantify patterns and regularity of intensities.

- Microenvironment features: Spatial relationships between cells and structures.

How do I handle artifact detection in a high-throughput experiment? Implement automated field-of-view quality control. To detect blurring, compute the log-log slope of the power spectrum of pixel intensities. To identify saturation, calculate the percentage of saturated pixels in an image. We recommend computing multiple such measures to identify and flag a wider range of potential artifacts [20].

The following table summarizes the core components of the featured public datasets, which are critical for planning your experiments and analyses.

Table 1: Key Resource Specifications

| Resource Feature | JUMP-Cell Painting Consortium [25] [28] | EU-OPENSCREEN Compound Set [26] [3] |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Content | Cell Painting image data and morphological profiles | Curated collection of bioactive compounds |

| Key Cell Lines | U2 OS, etc. | Hep G2, U2 OS [3] |

| Number of Compounds | Large-scale, consortium-driven compound set | 2,464 bioactive compounds [3] |

| Imaging Sites | Single centralized source (Broad Institute) | 4 different imaging sites [3] |

| Data Type | Cellular images and extracted feature profiles | Morphological profiles and bioactivity data |

| Primary Application | MOA prediction, drug discovery | Exploring compound bioactivity and toxicity |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Morphological Profiling |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay [20] | A standardized multiplexed staining protocol using up to six fluorescent dyes to label major cellular components (nucleus, cytoplasm, mitochondria, etc.), enabling comprehensive morphological capture. |

| High-Quality Compound Collections [26] | Well-annotated chemical libraries, such as the EU-OPENSCREEN Bioactive compounds, used to perturb biological systems in a reproducible manner. |

| High-Throughput Confocal Microscopy [3] | Advanced imaging systems essential for acquiring high-resolution, multi-channel z-stack images of cells in large-scale screening experiments. |

| Image Analysis Software (e.g., CellProfiler, Ilastik) [20] | Computational tools used for critical image processing steps: illumination correction, segmentation of individual cells and structures, and feature extraction. |

| Bioactivity Database (e.g., ECBD) [26] | An open-access database containing millions of data points, used for validating profiles, predicting activity, and training machine learning models. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The diagram below outlines the standard workflow for generating and analyzing morphological profiling data, integrating key steps from troubleshooting guides.

Detailed Methodology for Key Steps

Assay Optimization and Cross-Site Validation (EU-OPENSCREEN Protocol): The high reproducibility of the EU-OPENSCREEN resource was achieved through an extensive assay optimization process across four different imaging sites. This ensures that the morphological profiles generated are consistent and comparable, regardless of the imaging location [3].

Image Analysis Workflow:

- Illumination Correction: Apply a retrospective multi-image method to correct for uneven illumination within a batch (e.g., all images from one plate) [20].

- Segmentation: Use a model-based approach (e.g., identifying nuclei first as seeds for whole-cell segmentation) for standard cell lines. For difficult samples, use a machine-learning-based approach (e.g., Ilastik) with manual pixel training [20].

- Feature Extraction: Extract hundreds of quantitative features for each cell, covering shape, intensity, texture, and spatial context to build a rich morphological profile [20].

Profiling and MOA Prediction: The extracted morphological profiles form a "fingerprint" for each compound treatment. By comparing these profiles to a public reference dataset (like JUMP-Cell Painting) using pattern-matching algorithms, researchers can predict the Mechanism of Action (MOA) of uncharacterized compounds by associating them with known bioactivities [25] [3].

From Classical Feature Extraction to AI-Driven Approaches: Methodological Evolution

In the field of image-based profiling, the quantitative analysis of cell morphology is crucial for biological discovery, including identifying disease mechanisms, determining the impact of chemical compounds, and understanding gene functions [4]. Traditional feature extraction using CellProfiler involves the use of handcrafted descriptors—carefully developed and optimized morphological features captured through classical image processing software [4]. These features represent the current standard in the field, designed to capture cellular morphology variations including size, shape, intensity, and texture of various stains in an image [4]. Within the context of morphological profiling data analysis, these handcrafted features provide biologically interpretable representations that describe single-cell morphological characteristics from specific aspects such as size, orientation, and intensity [29]. Every column of these representations describes a particular cellular aspect, making them inherently explainable from a biological perspective [29]. This interpretability offers significant value in applications like drug discovery, where understanding the linkage between cellular morphology and chemical effects is paramount [29].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using CellProfiler's handcrafted features over learned representations from machine learning models?

CellProfiler extracts well-established morphological features without extensive human intervention, producing interpretable representations with clear biological meanings [29]. Each feature column describes a specific aspect of single-cell morphology, such as size or intensity, allowing researchers to directly understand and interpret the biological significance of their measurements [29]. This contrasts with machine learning representations which, while often exhibiting better performance in some discrimination tasks, typically operate as "black boxes" with limited biological explainability [29].

Q2: How can I resolve issues with the ClassifyObjects module assigning indistinguishable colors to different object classes?

This is a recognized challenge, particularly for colorblind users. The colors are drawn from the program-wide default colour palette set in the preferences dialog. You can select from common matplotlib palettes in the preferences menu to suit your needs. For future versions, the development team has modified the figure display to more reliably shuffle colors between runs [30].

Q3: Why does CellProfiler fail to start after installation on Windows systems?

This issue particularly affects versions 4.2.8 on Windows 10 and 11. The program may show only a briefly flashing terminal window. This problem has been confirmed to be caused by antivirus software (specifically Sentinel One) blocking the application. Work with your IT department to whitelist CellProfiler in your antivirus software, or temporarily disable the software for testing. If issues persist, version 4.2.7 is a stable alternative [31].

Q4: How can I implement complex gating strategies for classifying cell subpopulations based on multiple intensity measurements?

While FilterObjects module only allows hard thresholds in each feature dimension, complex gating requires alternative approaches. For elliptical or irregularly-shaped populations visible in scatterplots, you can use CellProfiler Analyst to create density plots and manually gate populations of interest [32]. Alternatively, consider calculating derived metrics using CalculateMath to transform your data, or use external analysis in R or Python followed by importing classification results back into CellProfiler [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Computational Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common CellProfiler Issues

| Problem Domain | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module Functionality | ClassifyObjects produces indistinguishable colors | Default color palette; random assignment each run | Modify default color palette in Preferences | Select colorblind-friendly palettes; request fixed color assignment |

| Error: "boolean index did not match indexed array" | Software bug; object measurement dimension mismatch | Use FilterObjects module as workaround | Ensure consistent object identification across pipeline | |

| Installation & Startup | CellProfiler fails to start (Windows 10/11) | Antivirus blocking; version-specific bug | Whitelist in antivirus; install version 4.2.7 | Check compatibility before updating; consult user forums |

| Plugin-related startup failures | Incorrect plugins path configuration | Set plugins directory to correct 'active_plugins' folder | Verify folder structure during plugin installation | |

| Data Analysis & Interpretation | Inability to create non-rectangular gates in FilterObjects | Module limitation to hard thresholds per dimension | Use CellProfiler Analyst for manual gating | Pre-plan analysis strategy for complex populations |

| Poor retrieval of replicate perturbations | Plate layout effects; weak phenotypic signals | Apply well-position mean centering; optimize assay conditions | Validate assay sensitivity with positive controls |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Benchmarking Feature Performance

Protocol: Benchmarking Perturbation Detection Using Handcrafted Features

Objective: To evaluate the sensitivity of CellProfiler's handcrafted features in detecting morphological changes induced by chemical or genetic perturbations compared to negative controls.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell lines (e.g., U2OS and A549 as used in CPJUMP1) [4]

- Chemical perturbations (e.g., Drug Repurposing set) [4]

- Genetic perturbations (CRISPR knockout and ORF overexpression) [4]

- CellPainting assay reagents [4]

- 384-well plates [4]

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Treat cells with matched chemical and genetic perturbations targeting the same genes across multiple cell types and time points [4].

- Image Acquisition: Capture approximately 3 million images using high-throughput microscopy [4].

- Feature Extraction: Process images using CellProfiler to extract handcrafted morphological features (size, shape, intensity, texture) for ~75 million single cells [4].

- Profile Aggregation: Generate well-level aggregated profiles from single-cell data [4].

- Similarity Calculation: Compute cosine similarity between perturbation replicates and negative controls [4].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate average precision for each sample's ability to retrieve its replicates against negative control background [4].

- Perform permutation testing to obtain p-values, adjusted using false discovery rate to yield q-values [4].

- Determine fraction of perturbations with q-value < 0.05 significance threshold (fraction retrieved) [4].

Interpretation: Compounds typically show higher fraction retrieved than genetic perturbations, with CRISPR knockout generally more detectable than ORF overexpression [4]. Note that plate layout effects can significantly impact results, particularly for ORF overexpression [4].

Protocol: Evaluating Perturbation Matching Capability

Objective: To assess the capability of handcrafted features to correctly group gene-compound pairs where the gene's product is a target of the compound.

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation: Utilize the CPJUMP1 resource dataset containing chemical and genetic perturbation pairs targeting the same genes [4].

- Profile Comparison: Calculate cosine similarity (or its absolute value) between pairs of well-level aggregated profiles [4].

- Benchmark Establishment: Create retrieval task where the goal is to find genes or compounds with similar morphological impacts as the query [4].

- Performance Evaluation: Measure success in identifying known biological relationships through morphological similarity [4].

Application: This protocol enables researchers to test computational strategies for representing samples to uncover biological relationships, potentially elucidating compounds' mechanisms of action or novel regulators of genetic pathways [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Morphological Profiling

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Morphological Profiling | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | Standardized microscopy-based profiling using fluorescent dyes | High-throughput morphological screening of chemical and genetic perturbations [4] |

| CPJUMP1 Dataset | Benchmark dataset with 3 million images & morphological profiles | Method development and validation for image-based profiling [4] |

| BBBC021 Dataset | Benchmark dataset of cell responses to drugs | Training and validation of generative models like CP2Image [29] |

| CellProfiler Analyst | Data exploration and analysis software | Interactive analysis of multidimensional image-based screening data [33] |

| Equivalence Scores | Multivariate metric for treatment comparison | Highlighting morphological deviations from negative controls [34] |

Workflow Visualization: From Image Acquisition to Biological Insight

Critical Analysis: Limitations of Handcrafted Descriptors

Technical and Biological Constraints

The application of handcrafted CellProfiler features presents several significant limitations for modern morphological profiling research:

Limited Reconstruction Capability: While handcrafted features demonstrate impressive discrimination performance for mechanisms of action, their capability to generate realistic cell images remains limited compared to machine learning approaches [29]. The CP2Image model represents a pioneering effort to bridge this gap, generating realistic single-cell images directly from CellProfiler representations, but the field is still evolving [29].

Standardization Challenges: Widespread adoption of morphological profiling is partially hindered by lack of alignment in analysis methodologies and output metrics, limiting data comparability across studies [35]. While CellProfiler provides extensive feature sets, the identification of a minimal set of morphological measurands, often termed Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), traceable to standardized units remains a challenge [35].

Workflow Complexity: Traditional CellProfiler analysis requires multiple post-processing steps including normalization, feature selection, and dimensionality reduction [4]. This multi-step process introduces potential variability and requires careful optimization at each stage to produce reliable morphological profiles [4].

Emerging Solutions and Comparative Performance

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods

| Evaluation Metric | Handcrafted Features | Learned Representations | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Interpretability | High (clear feature meaning) [29] | Limited ("black box") [29] | Direct linkage to cellular morphology [29] |

| Image Generation Capability | Limited (requires CP2Image) [29] | High (native generative ability) [29] | Visualization of morphological responses to treatments [29] |

| Perturbation Detection | Variable (compounds > CRISPR > ORF) [4] | Architecture-dependent | Identification of phenotypically active treatments [4] |

| Standardization Potential | Challenging (many redundant features) [35] | Architecture-dependent | Enabling data comparability across labs [35] |

Handcrafted descriptors from CellProfiler remain foundational for morphological profiling, offering unparalleled biological interpretability that is crucial for applications in drug discovery and functional genomics [29]. However, their limitations in image reconstruction, standardization, and handling complex phenotypic patterns necessitate complementary approaches. The integration of handcrafted features with machine learning methods, such as the CP2Image model that generates realistic images from CellProfiler representations, represents a promising direction for the field [29]. Furthermore, emerging metrics like Equivalence Scores that use negative controls as baselines demonstrate improved performance in k-NN classification of morphological changes compared to using raw CellProfiler features alone [34]. As the field advances toward greater standardization and identification of Critical Quality Attributes, the strengths of handcrafted features—particularly their biological interpretability—will continue to make them valuable for researchers tackling morphological profiling data analysis challenges [35].

FAQs: Self-Supervised Learning for Morphological Profiling

Q1: What are the main advantages of using self-supervised learning (SSL) over supervised learning for morphological profiling in drug discovery?

SSL offers two key advantages for morphological profiling. First, it eliminates the massive cost and time required for manual data annotation. Creating a high-quality labeled dataset for tasks like image segmentation can cost millions of dollars [36]. Second, by learning from vast amounts of unlabeled data, SSL models learn robust and generalizable feature representations. This reduces overfitting and can make models less sensitive to adversarial attacks [36]. In practice, this means you can leverage existing, unlabeled data from high-throughput microscopy systems, like Cell Painting assays, to build powerful foundation models without manual annotation [3] [34].

Q2: My lab works with 3D medical images. Why might a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) be a good choice, and what are the common pitfalls to avoid?

MAEs are highly effective for 3D data because their pre-training task—reconstructing masked portions of the input—learns strong internal representations of anatomical structure [37]. However, previous applications in 3D medical imaging have faced three common pitfalls [37]:

- P1 - Limited Dataset Size: Training on too few unlabeled volumes (e.g., <10,000) fails to unlock SSL's potential.

- P2 - Outdated Backbones: Using architectures that are not state-of-the-art for the target downstream task (e.g., transformers for segmentation when CNNs dominate).

- P3 - Insufficient Evaluation: A lack of rigorous evaluation on diverse, unseen datasets and comparisons against strong baselines. A recent successful implementation, which avoided these pitfalls, used a large dataset of ~39k 3D MRI volumes and a Residual Encoder U-Net CNN architecture, establishing a new state-of-the-art [37].

Q3: The DINOv3 paper claims its features are "universal." What does this mean for a researcher analyzing satellite or histology images?

A "universal" backbone means that a single, pre-trained model can produce high-quality features for a wide array of tasks without needing task-specific fine-tuning [38]. For your work, this implies:

- Versatility: A DINOv3 model pre-trained on satellite imagery can be applied directly to various downstream tasks like land cover classification, canopy height estimation, and change detection [38] [39].

- Efficiency: You can train lightweight linear classifiers or adapters on top of the frozen DINOv3 backbone with minimal annotations, drastically reducing computational costs and development time [38]. This has been demonstrated in real-world applications, such as using DINOv3 to analyze satellite imagery for deforestation monitoring with high accuracy [38].

Q4: I have limited compute resources. Can I still use large SSL models like DINOv3?

Yes. The developers of DINOv3 have addressed this by creating a family of models to suit different compute constraints [38]. For resource-constrained environments, you can use:

- Distilled Models: Smaller versions (e.g., ViT-B and ViT-L) that retain much of the performance of the largest model.

- Alternative Architectures: ConvNeXt-based versions (Tiny, Small, Base, Large) that are distilled from the ViT model and are designed for efficient deployment [38]. Furthermore, frameworks like DEIMv2 integrate DINOv3 features into real-time object detection models that span from large (X) to ultra-lightweight (Atto) scales, making them suitable for mobile and edge devices [40].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Poor Feature Quality in Contrastive Learning

- Problem: Your model fails to learn discriminative features, leading to low performance on downstream tasks.

- Solution: Implement hard negative mining. Early contrastive learning models treated all negative samples equally, which diluted learning. Modern variants of frameworks like MoCo focus on identifying and prioritizing "hard negatives"—data points that are semantically similar but belong to different classes. This forces the model to learn finer distinctions and results in richer representations [41].

Challenge 2: Integrating Data from Multiple Modalities

- Problem: How to effectively combine different types of image data (e.g., RGB, multispectral, temporal) for a unified analysis.

- Solution: Employ a Cross-Modal Fusion (CMF) strategy. Research in satellite image analysis has shown that you can enrich feature representations by fusing data from different modalities. For instance, one can effectively combine multispectral and temporal data using a cross-modal fusion module within a Convolutional Vision Transformer (CvT) architecture, significantly enhancing feature discrimination and final classification accuracy [39].

Challenge 3: Achieving Spatial Coherence in Predictions

- Problem: Model predictions for individual pixels or cells lack consistency with their spatial neighbors, making results look noisy.

- Solution: Use Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) for post-processing. CRFs are a probabilistic graphical model that can enforce spatial smoothness and consistency. By incorporating CRFs, you can refine raw model outputs, ensuring that the final segmentation or classification map respects spatial relationships and leads to more biologically plausible results [39].

Comparative Analysis of SSL Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and ideal use cases for DINO, MAE, and SimCLR.

| Method | Core Pre-training Mechanism | Key Strengths | Common Architectures | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DINO/DINOv3 | Self-distillation; matching outputs of a student and teacher network for different augmented views of an image [38]. | Produces strong, high-resolution features; excels at dense prediction tasks; versatile "universal" backbone [38]. | Vision Transformer (ViT) [38] | Segmentation, depth estimation, object detection on natural, medical, or satellite imagery [38] [40]. |

| MAE (Masked Autoencoder) | Reconstructs randomly masked patches of the input image [37]. | Highly scalable and efficient; learns rich internal representations of data structure and content [37]. | Vision Transformer (ViT), CNN (e.g., U-Net) [37] | Pre-training for data-rich domains (e.g., 3D medical imaging); tasks requiring understanding of global context [37]. |

| SimCLR | Contrastive learning; pulls augmented views of the same image together while pushing views of different images apart [41] [39]. | Simple and effective framework; improves class separability in the feature space [41] [39]. | CNN (e.g., ResNet), Vision Transformer [41] [39] | Image classification; representation learning where class separation is crucial; can be integrated with other methods [39]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key SSL Methods

Protocol 1: Implementing a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) for 3D Data

This protocol is based on a successful implementation for 3D medical image segmentation [37].

- Data Preparation: Assemble a large-scale unlabeled dataset. A successful study used ~39k 3D MRI volumes. Critically, filter out low-quality data (e.g., scout scans, images with a field of view <50mm, or incorrect file sizes) [37].

- Preprocessing: Resample all images to a uniform target spacing (e.g., 1x1x1 mm). Apply z-score normalization to achieve zero mean and unit variance [37].

- Model Architecture: Utilize a state-of-the-art CNN architecture for the downstream task. The cited study used a Residual Encoder U-Net within the nnU-Net framework [37].

- Pre-training:

- Masking: Randomly mask a high proportion (e.g., 80-90%) of the input 3D volume.

- Task: Train the model to reconstruct the masked voxels. Use an L1 or L2 loss between the reconstructed and original voxel intensities.

- Optimizer: Use SGD with a polynomial learning rate decay [37].

- Downstream Fine-tuning: Transfer the pre-trained encoder weights to your target segmentation network and fine-tune on the labeled downstream task.

Protocol 2: Leveraging DINOv3 Features for Downstream Task Adaptation

This protocol outlines how to use a pre-trained DINOv3 backbone for a new task without fine-tuning the backbone itself [38] [40].

- Backbone Selection: Choose a pre-trained DINOv3 model (e.g., ViT-g, ViT-L, or a distilled version) suitable for your compute constraints [38].

- Feature Extraction: Perform a single forward pass of your images through the frozen DINOv3 backbone to extract feature maps.

- Adapter Design: To adapt these features for a task like object detection, design a lightweight adapter. For example, DEIMv2 uses a Spatial Tuning Adapter (STA) to efficiently convert DINOv3's single-scale features into multi-scale features, complementing strong semantics with fine-grained details [40].

- Task-Specific Head: Train a small task-specific head (e.g., a linear layer, or a more sophisticated decoder for segmentation) on top of the adapted features. This step requires minimal labeled data.

- Evaluation: The entire pipeline can achieve state-of-the-art performance while keeping the backbone frozen, allowing the same features to be shared across multiple applications [38] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in SSL for Image Analysis |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, high-throughput microscopy assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular compartments. It generates rich, morphological profiles used as a basis for training and validating SSL models in drug discovery [3] [34]. |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) | A neural network architecture that processes images as sequences of patches. It is the foundational backbone for modern SSL methods like DINOv3 and MAE, enabling them to model global context in images [36] [38]. |

| Convolutional Vision Transformer (CvT) | An enhanced ViT that incorporates convolutional layers. It improves local feature extraction and computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for high-resolution satellite and medical imagery [39]. |

| Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) | A probabilistic model used for post-processing. It refines SSL model outputs by enforcing spatial coherence and smoothness, leading to more accurate and biologically plausible segmentations [39]. |

| Momentum Contrast (MoCo) | A contrastive learning framework that uses a momentum-updated encoder and a memory bank to maintain a large and consistent set of negative samples, which is crucial for learning effective representations [41]. |

SSL Method Workflow Diagrams

Morphological Profiling Data Processing Steps

The table below Articalizes the critical steps for generating high-quality morphological profiles from microscopy images, which serve as the foundation for effective SSL.

| Processing Step | Core Function | Recommended Techniques & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Illumination Correction | Corrects for uneven lighting in raw images to ensure accurate quantification. | Use retrospective multi-image methods that build a correction function from all images in a batch (e.g., per plate). Avoids inconsistencies of single-image methods [20]. |

| Segmentation | Identifies and outlines individual cells and sub-cellular structures. | Model-based approaches (e.g., CellProfiler) work well for standard fluorescence images. Machine learning-based (e.g., Ilastik) is better for highly variable cell types or tissues but requires manual labeling for training [20]. |

| Feature Extraction | Quantifies hundreds of morphological characteristics per cell. | Extract a wide variety of features: Shape (area, perimeter), Intensity (mean, max), Texture (patterns), and Microenvironment (spatial relationships) to create a rich, unbiased profile [20]. |

| Image QC | Automatically flags blurry, saturated, or otherwise corrupted images. | Compute multiple metrics (e.g., power spectrum log-slope for blur, percentage of saturated pixels). Use data-analysis tools to set robust thresholds for exclusion [20]. |

| Cell-Level QC | Removes outlier cells resulting from segmentation errors or artifacts. | Filter cells based on predefined criteria (e.g., size, intensity extremes, location at image edge) to prevent contamination of the morphological profile with noise [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core difference between whole-image analysis and single-cell segmentation in terms of their data output?

Whole-image analysis typically provides summary statistics or patch-level classifications for a tissue region, such as the overall density of a cell type or the spatial proximity between two cell communities. In contrast, single-cell segmentation is the process of identifying the precise boundary of every cell in an image, resulting in single-cell expression profiles, morphology measurements, and spatial coordinates for each individual cell [42] [43]. The key trade-off is that while segmentation enables powerful single-cell analysis, it is an error-prone process. Inaccuracies at this stage, such as segments that capture parts of multiple cells (doublets), can have far-reaching consequences for all downstream biological interpretation [44] [42].

FAQ 2: My segmentation results show cells co-expressing mutually exclusive markers (e.g., CD3 and CD20). What is the cause and how can I resolve it?

The appearance of cell populations that co-express biologically implausible marker combinations is a classic indicator of segmentation errors, specifically heterotypic doublets where a single segment covers two or more adjacent cells of different types [44]. To resolve this, consider the following steps:

- Validate with a plausibility score: Curate a list of known mutually exclusive and conditionally co-expressed marker pairs to quantify the biological plausibility of your discovered cellular phenotypes [44].

- Use segmentation-aware tools: Employ computational methods like STARLING, a probabilistic clustering model designed to infer cell populations while explicitly accounting for segmentation errors. This allows you to recover denoised cellular phenotypes from potentially flawed segmentation data [44].

- Inspect segmentation quality: Manually review the segmentation masks in densely packed tissue regions to confirm the algorithm is correctly separating adjacent cells.

FAQ 3: I am working with H&E-stained images. What are my options for whole-cell segmentation, and how do they compare?

While H&E-stained tissue is the diagnostic gold standard, whole-cell segmentation is more challenging than nuclei segmentation due to weak and variable membrane signals [45]. The following table compares two advanced approaches:

| Method | Key Principle | Reported Performance (F1 Score at IoU=0.5) | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSGO (Cell Segmentation with Globally Optimized boundaries) | Integrates a dedicated U-Net for membrane detection with HD-YOLO for nuclei detection, followed by an energy-based watershed algorithm [45]. | 0.37 to 0.53 across multiple cancer types (e.g., lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) [45]. | A specialized, robust pipeline for H&E images that does not require image inversion. |

| Cellpose | A generalist algorithm trained on diverse image types, including fluorescence, brightfield, and H&E [45]. | 0.21 to 0.36 on the same external datasets as CSGO [45]. | For H&E images, may require a preprocessing step to invert image intensities, which can affect generalizability across cancer types with different staining intensities [45]. |

FAQ 4: For a new, large-scale imaging project, what are the key computational and logistical factors I should consider when choosing a segmentation strategy?

Beyond pure algorithmic accuracy, consider these factors for a scalable and efficient project:

- Computational Infrastructure: Deep learning models like Mesmer and BIDCell can achieve human-level performance but require significant resources, often needing specialized GPU infrastructure to scale effectively [42] [46].

- Analysis Speed: Deep learning models, once trained, are typically faster for analyzing large datasets than classical methods like watershed, which can run into major scaling issues [46]. However, training the models themselves is computationally intensive.

- Ease of Use and Parameter Tuning: Classical methods often require extensive manual parameter tuning for each new dataset. In contrast, modern deep learning tools like Cellpose are designed as generalist models with fewer tunable parameters, making them more accessible for non-expert users [47] [46].

- Cloud-Based Solutions: To mitigate local hardware constraints, consider cloud-oriented tools and resources that are becoming more prevalent and user-friendly, moving technical complexity away from the end-user [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Cell Segmentation in Densely Packed Tissue Regions

Problem: In tissues with high cellular density, segmentation algorithms frequently fail, resulting in merged cells (under-segmentation) or fragmented cells (over-segmentation). This is a common issue in lymphoid tissues like the tonsil or in densely packed epithelia [44] [48].

Solution Protocol:

- Preprocessing (Image Restoration): For 3D tissues, ensure imaging parameters are optimized for depth. Use image restoration (deconvolution) software like Huygens Professional to reduce scattering and improve signal-to-noise ratio, especially in deeper axial planes [48].

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a segmentation method designed for complex morphologies. For 3D tissues, a human-in-the-loop pipeline using Cellpose is effective [48]. For 2D highly multiplexed images (IMC, MIBI-TOF), use a segmentation-aware clustering tool like STARLING to de-noise the cellular phenotypes post-segmentation [44].

- Human-in-the-Loop Correction:

- Obtain an initial segmentation with a pre-trained model (e.g., Cellpose 'cyto3').

- Manually correct the segmentation in each 2D slice using an interactive tool like Napari or DeepCell Label [48].

- Use TrackMate (in Fiji/ImageJ) to automatically correct 3D stitching issues, then manually correct any remaining errors [48].

- Model Retraining: Use the manually corrected segmentation as ground truth to re-train the model. This iterative process significantly improves accuracy for your specific tissue type [48].

Issue: Integrating Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data with Spatial Transcriptomics to Improve Segmentation

Problem: In Subcellular Spatial Transcriptomics (SST) data, such as from Xenium or CosMx, relying solely on image intensity may not be sufficient for accurate cell segmentation, leading to contaminated expression profiles.

Solution Protocol: