Overcoming GC Bias in Chemogenomic NGS Sequencing: Strategies for Accurate Data and Reliable Discovery

GC bias, a pervasive technical artifact in next-generation sequencing (NGS), systematically distorts genomic coverage and compromises data integrity, posing a significant challenge in chemogenomics for drug discovery and biomarker identification.

Overcoming GC Bias in Chemogenomic NGS Sequencing: Strategies for Accurate Data and Reliable Discovery

Abstract

GC bias, a pervasive technical artifact in next-generation sequencing (NGS), systematically distorts genomic coverage and compromises data integrity, posing a significant challenge in chemogenomics for drug discovery and biomarker identification. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the mechanisms, impacts, and solutions for GC bias. We explore the foundational causes of this bias across major sequencing platforms, present methodological best practices from sample preparation to data analysis, detail advanced troubleshooting and optimization protocols for library preparation, and offer a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of correction methods. By synthesizing current research and practical insights, this resource aims to empower scientists to produce more accurate, reproducible, and biologically meaningful sequencing data, thereby enhancing the reliability of chemogenomic applications in biomedical research.

Understanding GC Bias: The Hidden Driver of Data Distortion in NGS

Defining GC Bias and Its Critical Impact on Chemogenomic Data Integrity

FAQs on GC Bias in Chemogenomic NGS

What is GC Bias in Next-Generation Sequencing? GC bias describes the uneven sequencing coverage of genomic regions due to their guanine-cytosine (GC) content. It causes the under-representation of both GC-rich (>60%) and GC-poor (<40%) regions during sequencing, leading to inaccurate abundance measurements in genomic and metagenomic data [1] [2]. This bias primarily arises during the PCR amplification steps of library preparation, where DNA fragments with extreme GC content amplify less efficiently [3].

Why is GC Bias a Critical Concern in Chemogenomic Research? GC bias is critical because it directly compromises data integrity, which is the foundation of reliable scientific conclusions. In chemogenomics, where researchers link chemical compounds to genomic signatures, GC bias can:

- Skew abundance estimates, making some genomic regions or microbial species appear more or less abundant than they truly are [2] [4].

- Cause false negatives in variant calling, as regions with poor coverage may hide true genetic variants [1].

- Lead to incorrect assembly of genomes, creating artificial gaps, especially in GC-extreme regions [2].

- Confound biological signals, potentially misguiding drug discovery and diagnostic development by creating artifacts that mimic or obscure true biological effects [4].

Which Sequencing Platforms are Most Affected by GC Bias? The degree and profile of GC bias vary significantly across sequencing platforms and their associated library preparation protocols. The following table summarizes the GC bias profiles of common platforms based on experimental data:

Table 1: GC Bias Profiles Across Sequencing Platforms

| Sequencing Platform | GC Bias Profile | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina (MiSeq, NextSeq) | Major GC bias | Severe under-coverage outside the 45–65% GC range; GC-poor regions (30% GC) can have >10-fold less coverage than regions at 50% GC [2]. |

| Illumina (HiSeq) | Moderate GC bias | Shows a distinct but less severe bias profile compared to MiSeq/NextSeq [2]. |

| PacBio | Moderate GC bias | Similar GC bias profile to HiSeq, distinct from MiSeq/NextSeq [2]. |

| Oxford Nanopore | Minimal to No GC bias | Demonstrated no significant GC bias in comparative studies, making it a robust choice for quantifying samples with diverse GC content [2]. |

How Can I Identify GC Bias in My Own Sequencing Data? You can identify GC bias using standard quality control (QC) tools. Software like FastQC provides graphical reports that plot the relationship between GC content and read coverage, highlighting deviations from an expected normal distribution [1]. More detailed assessments can be performed with tools like Picard and Qualimap, which enable detailed evaluation of coverage uniformity [1]. An unbiased dataset should show a relatively smooth, unimodal distribution of coverage across the GC spectrum, while a biased one will show dramatic dips in coverage for GC-rich and/or GC-poor regions [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Metagenomic Quantification Due to GC Bias

Symptoms

- Observed microbial community structure does not match expected biological composition.

- Under-representation of specific taxa, particularly those with GC-extreme genomes (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria with high GC content) [4].

- Poor correlation between technical replicates when using different library prep methods.

Diagnosis and Resolution This problem often originates from biased library preparation. Follow this diagnostic and resolution workflow:

Experimental Protocol: Validating GC Bias with a Mock Community

- Obtain a Mock Community: Use a commercially available or in-house assembled mock microbial community with known genome sequences and a wide range of GC contents (e.g., from 30% to 70% GC).

- Sequencing: Sequence the mock community using your standard NGS workflow.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map the sequencing reads to the reference genomes of the mock community members.

- Calculate the mean coverage for each genome.

- Plot the normalized coverage against the known GC content of each genome.

- Interpretation: A strong correlation between coverage and GC content indicates significant GC bias in your workflow [2].

Problem: Gaps in Genome Assembly and Coverage Dropouts

Symptoms

- Incomplete de novo genome assembly with many short contigs.

- Consistent lack of coverage in specific genomic regions, often correlated with high or low GC content.

- Difficulty in identifying variants in GC-extreme regions, leading to false negatives [1].

Diagnosis and Resolution Coverage dropouts are frequently caused by the combined effects of DNA extraction and PCR amplification biases.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Coverage Gaps

| Root Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Lysis | Check if coverage gaps correlate with hard-to-lyse organisms (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria). Compare extraction yields from different kits. | Implement a balanced lysis protocol combining mechanical bead-beating (using a mix of small, dense beads) with enzymatic lysis (e.g., lysozyme, mutanolysin) [4]. |

| PCR Amplification Bias | Check library prep protocol for number of PCR cycles. Look for high duplicate read rates in QC reports. | 1. Reduce PCR cycles or switch to a PCR-free library prep if input DNA allows [1]. 2. Use polymerase mixtures and buffers optimized for high-GC or high-AT templates (e.g., additives like betaine for GC-rich regions) [2] [1]. |

| Fragmentation Bias | Analyze fragment size distribution. Enzymatic fragmentation can introduce sequence-specific biases. | Use mechanical shearing (e.g., sonication, acoustics) which has demonstrated improved coverage uniformity compared to enzymatic methods [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mitigating GC Bias

| Reagent / Material | Function in Mitigating GC Bias |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Bead-Beating System (e.g., Bead Ruptor Elite) | Ensures equitable lysis of diverse cell types (Gram-positive, Gram-negative) by combining strong mechanical shear with optimized, dense ceramic beads, preventing under-representation at the DNA extraction stage [4]. |

| Multi-Enzyme Lysis Cocktail (e.g., MetaPolyzyme) | Used in conjunction with bead-beating to chemically degrade tough cell walls (e.g., peptidoglycan in Firmicutes), further improving DNA yield from hard-to-lyse organisms [4]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Eliminates the primary source of GC bias by removing the amplification step entirely, preserving the original abundance ratios of DNA fragments [2] [1]. |

| GC-Rich/AT-Rich Optimized Polymerase & Buffers | When PCR is unavoidable, these specialized enzymes and additives (e.g., betaine, TMAC) help to equilibrate the amplification efficiency across fragments with extreme GC content, leading to more uniform coverage [2] [1]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags ligated to each fragment before PCR. UMIs allow bioinformatic identification and correction of PCR duplicates, helping to distinguish technical artifacts from true biological signals [1]. |

Why is Understanding and Mitigating NGS Bias So Critical?

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), bias refers to any systematic deviation that causes some genomic sequences to be over- or under-represented in the final data. In the context of chemogenomic research, where you are often working with complex genomic DNA from treated cells, these biases can obscure true biological signals, such as subtle mutation patterns or gene expression changes induced by a compound. If not properly managed, biases can lead to both false positives and false negatives, compromising the validity of your findings [1]. The two most significant sources of this bias are the library preparation process itself and the PCR amplification steps that are necessary for most protocols [5] [1].

How Does Library Preparation Enzymatically Introduce Bias?

The very first step in library preparation—fragmenting DNA and adding adapter sequences—can be a major source of bias, particularly when using enzymatic methods like tagmentation.

- Molecular Mechanism: Transposases, such as the common Tn5 transposase, are enzymes that simultaneously fragment DNA and ligate adapters. Their activity can be influenced by local DNA sequence and structure. Wild-type transposases may exhibit sequence insertion bias, meaning they have preferred (or avoided) genomic insertion sites based on sequence context [6].

- Impact: This preference results in a library that does not quantitatively represent the original genome, leading to uneven coverage and potential gaps in data, especially in regions with extreme GC content [1].

- Solutions: The field has responded by engineering modified transposases with reduced bias. For example, mutations at specific residues in the Tn5 transposase (e.g., Asp248, Lys212, Pro214) have been shown to improve insertion sequence bias and increase DNA input tolerance, leading to more uniform genome coverage [6].

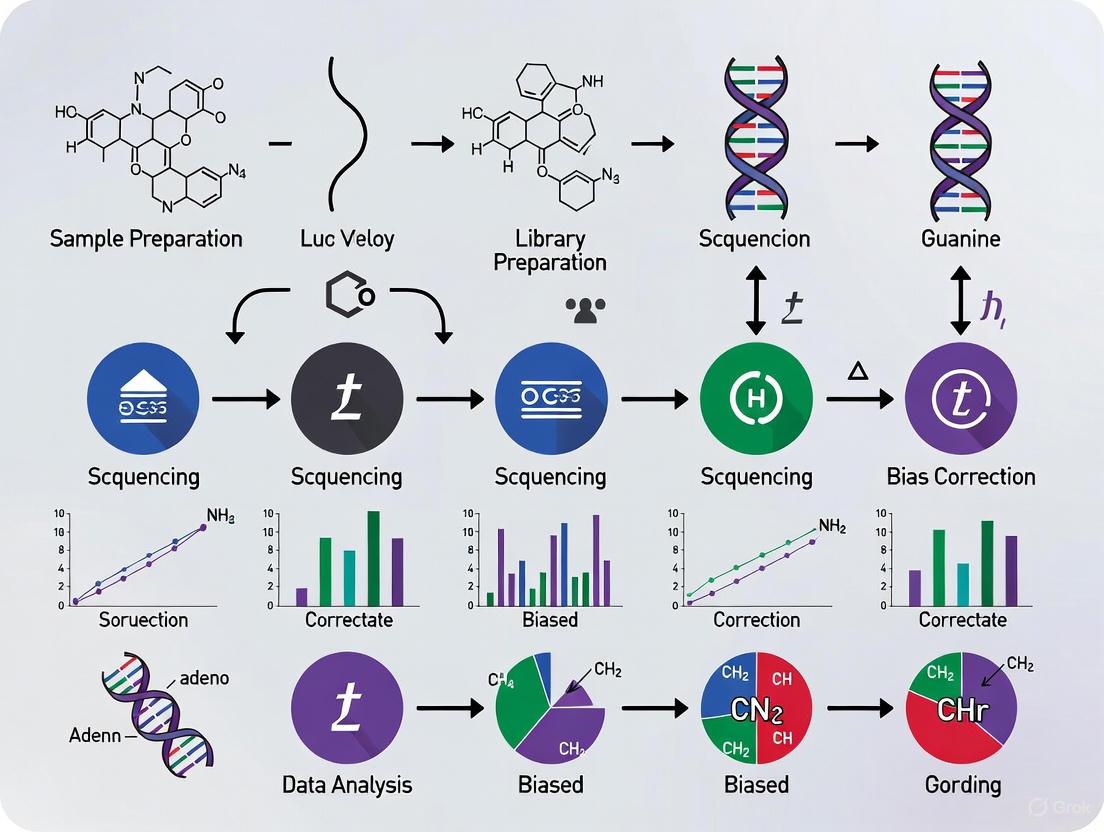

The following workflow summarizes the key points where bias is introduced during a standard NGS library preparation and highlights the corresponding mitigation strategies.

What is the Molecular Basis of PCR Amplification Bias?

PCR amplification is a necessary but often problematic step in NGS library prep, well-known as a major source of bias [5]. The core mechanism is differential amplification efficiency.

- Molecular Mechanism: A PCR reaction is a complex mixture of DNA fragments of different sizes, GC content, and secondary structures. DNA polymerases do not amplify all these fragments with equal efficiency. Smaller fragments and those with GC-neutral content (typically ~50%) amplify more readily than larger fragments, or those with very high or very low GC content [5] [1].

- Consequence of GC-Content:

- High-GC Regions (>60-65%): GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds (vs. two for AT), leading to higher thermostability and melting temperatures. This can prevent DNA strands from fully separating during the PCR denaturation step, causing polymerase stalling and incomplete amplification. These regions are also prone to forming stable secondary structures (e.g., G-quadruplexes) that block polymerase progression [7] [1].

- Low-GC Regions (<40%): While less studied, these AT-rich regions may also amplify poorly, potentially due to less stable primer binding or the formation of alternative secondary structures [1].

- Impact: Over multiple PCR cycles, these small efficiency differences are exponentially amplified. This results in sequencing data where some genomic regions are drastically over-represented while others are under-represented or even completely missing [5].

Which PCR Enzymes Perform Best for Minimizing Bias in NGS?

Choosing the right polymerase is one of the most critical decisions for reducing PCR bias. A 2024 systematic study evaluated over 20 different high-fidelity PCR enzymes for NGS library amplification across genomes with varying GC content [5].

Table 1: Evaluation of High-Fidelity PCR Enzymes for NGS Bias Reduction [5]

| Polymerase / Master Mix | Performance Characteristics | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Quantabio RepliQa Hifi Toughmix | Consistent performance across all genomes tested; also best for long fragment amplification. | Mirrored PCR-free data most closely; a top performer for both short- and long-read prep. |

| Watchmaker 'Equinox' | Consistent, high-performance coverage uniformity over all genomes tested. | Significantly outperformed previous industry standards like Kapa HiFi. |

| Takara Ex Premier | Robust and unbiased amplification across a range of GC contents. | One of three enzymes identified as giving the most even sequence representation. |

Best Practice: Based on this study, the enzymes listed above are recommended for short-read (Illumina) library amplification. Furthermore, keeping the number of PCR cycles to a minimum is essential to prevent the accumulation of bias. For the most even coverage, PCR-free library methods are recommended, though these require higher input DNA [5] [1].

A Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Overcoming GC-Bias

Success in unbiased NGS requires a combination of optimized reagents and protocols. The following table lists essential tools and strategies for mitigating bias, particularly for challenging GC-rich templates.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating GC and PCR Bias

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Mechanism | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bias-Reduced Transposase | Engineered transposase with mutations (e.g., D248K) for more random DNA fragmentation and adapter insertion [6]. | Replacing wild-type Tn5 in tagmentation-based library prep kits for more uniform coverage. |

| High-Fidelity, High-Synthesis Capacity Polymerase | DNA polymerase with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity and high processivity to efficiently amplify long and structured DNA [8]. | Amplifying complex templates in PCR or post-library amplification; essential for long-range PCR. |

| PCR Enhancers (e.g., Betaine, DMSO) | Betaine homogenizes DNA melting temperatures; DMSO disrupts DNA secondary structures, aiding in denaturation [7]. | Added to PCR reactions (e.g., 1-3% DMSO, 1M Betaine) to improve amplification of high-GC regions. |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | A dGTP analog that reduces hydrogen bonding, thereby lowering the melting temperature of GC-rich DNA [7]. | Partial replacement for dGTP in PCR mixes to facilitate amplification of extremely GC-rich sequences. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Random barcodes ligated to each DNA molecule before any amplification steps [1]. | Allows bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates and quantification of original molecule count. |

| Mechanical Shearing (Covaris/Sonication) | Physical method (acoustic shearing) for DNA fragmentation that is largely independent of DNA sequence [5] [1]. | Alternative to enzymatic fragmentation to generate libraries with reduced sequence-based bias. |

How Can I Troubleshoot and Overcome PCR Bias in My Experiments?

Here are detailed, actionable protocols to address specific bias-related issues.

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming High-GC PCR Amplification

Problem: Failure or poor efficiency when amplifying high-GC content (>65%) targets during library preparation or target enrichment.

Solutions & Protocols:

Optimize the PCR Reaction Chemistry

- Use Additives: Incorporate PCR enhancers like 1M Betaine or 1-3% DMSO into your master mix. These compounds help destabilize DNA secondary structures and promote more uniform strand separation [7].

- Adjust Mg²⁺ Concentration: Slightly increase the Mg²⁺ concentration (e.g., to 2.5-4 mM). Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for polymerases, and higher concentrations can facilitate primer binding and enzyme processivity in difficult regions, though this must be balanced against increased non-specific amplification risk [7].

- Consider dGTP analogs: For extreme cases, replace 50% of the dGTP in the dNTP mix with 7-deaza-dGTP to reduce the stability of GC base pairing [7].

Employ a Specialized PCR Regimen

- Increase Denaturation Temperature and Time: Use a high-thermostability polymerase (e.g., Phusion) that can withstand a 98°C denaturation step. Extend the initial denaturation to 2-5 minutes and use a 98°C denaturation step throughout the cycling program to ensure complete melting of GC-rich duplexes [7] [8].

- Apply a Touchdown PCR Protocol: Start with an annealing temperature 2-3°C above the calculated primer Tm for the first 5-10 cycles. Then, gradually decrease the annealing temperature by 1°C per cycle until the optimal Tm is reached. This early stringency selectively enriches the desired specific product before non-specific products can accumulate. A hot-start polymerase is recommended for this method [7] [8].

Utilize Advanced Primer Design

- Strategy: Design longer primers (25-30 bp) with a Tm of ~68-72°C. Avoid placing GC-rich stretches at the 3' end. Techniques like Stem-Loop Inclusion (STI) PCR can be used, where a universal, high-Tm sequence is added to the 5'-end of gene-specific primers to improve specificity and yield for difficult targets [7].

How Can Bioinformatics Tools Help Identify and Correct for Bias?

Even with optimized wet-lab protocols, some bias may persist. Bioinformatics tools are essential for diagnosing and computationally correcting these issues.

- Identification and QC: Tools like FastQC provide a visual report on sequence quality, including a "per sequence GC content" plot that shows if your library's GC distribution deviates from the theoretical expectation. Picard Tools and Qualimap can generate detailed metrics on coverage uniformity and duplicate read rates [1].

- Correction: Bioinformatics normalization algorithms exist that can adjust read depth based on local GC content, thereby improving the uniformity of coverage and the accuracy of downstream analyses like variant calling [1].

The following diagram illustrates a holistic strategy, integrating both experimental and computational approaches, to manage NGS bias.

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), GC bias refers to the uneven sequencing coverage resulting from variations in the proportion of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotides across different genomic regions. This technical artifact causes both GC-rich (>60%) and GC-poor (<40%) regions to be underrepresented in sequencing data, leading to coverage gaps and inaccurate variant calling [1]. This bias poses significant challenges for chemogenomic research, where comprehensive and uniform coverage of all genomic regions—including GC-extreme areas that may contain functionally important genes or regulatory elements—is essential for robust target identification and validation. Understanding the platform-specific profiles of this bias is the first step toward developing effective mitigation strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on GC Bias

Q1: What are the primary experimental causes of GC bias? GC bias primarily originates during library preparation, with PCR amplification being a major contributor. Polymerases often amplify sequences with extreme GC content less efficiently, leading to their underrepresentation. Additionally, specific enzymes used in library construction, such as transposases in some rapid protocols, exhibit sequence-specific insertion preferences that can further skew coverage [1] [9].

Q2: How does GC bias impact my chemogenomic sequencing data? The implications are substantial and can compromise research outcomes:

- Variant Calling: Poor coverage in GC-extreme regions can lead to false negatives (missing true variants) or false positives from sequencing artifacts [1].

- Structural Variant Detection: Uneven coverage obscures genuine genomic rearrangements like copy number variations (CNVs) [1].

- Microbiome Profiling: Quantitative microbial community analysis can be skewed, as the library preparation method can significantly alter the observed taxonomic profile [9].

- Target Identification: In chemogenomics, incomplete coverage can cause researchers to miss potential drug targets located in difficult-to-sequence genomic regions.

Q3: Which sequencing platform is most susceptible to GC bias? Illumina short-read sequencing has been widely documented to exhibit strong GC bias due to its reliance on PCR amplification during library preparation [3] [1]. While long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore also display biases, their patterns differ based on the underlying biochemistry. Nanopore's rapid transposase-based kits, for example, show a distinct coverage bias tied to the transposase recognition motif [9].

Q4: Can GC bias be corrected computationally? Yes, several bioinformatics tools can help normalize sequencing data based on GC content. Algorithms that adjust read depth according to local GC composition can improve coverage uniformity and enhance the accuracy of downstream analyses. These are often used in conjunction with experimental mitigations for best results [1].

Troubleshooting Guides: Platform-Specific GC Bias Profiles

The following section provides a detailed comparison of how GC bias manifests across the three major sequencing platforms, with targeted troubleshooting advice.

GC Bias Profile: Illumina Short-Read Sequencing

- Root Cause: The bias is predominantly driven by PCR amplification during library preparation. Both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments amplify less efficiently, creating a unimodal bias curve where coverage peaks in mid-GC regions and drops off at both extremes [3] [1]. Enzymatic fragmentation methods can also introduce sequence-dependent bias.

- Impact on Data: This results in uneven coverage, gaps in genome assembly, and reduced accuracy in variant calling and CNV detection, particularly in promoter regions and other GC-extreme areas [1].

Troubleshooting Steps for Illumina:

- Switch to PCR-free library prep: Where input DNA allows, use PCR-free workflows to eliminate the primary source of amplification bias [1].

- Optimize fragmentation: Use mechanical fragmentation (e.g., sonication) over enzymatic methods, as it generally provides improved coverage uniformity across varying GC content [1].

- Utilize Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs before amplification to accurately distinguish true biological duplicates from PCR duplicates [1].

- Apply bioinformatic correction: Use tools like Picard or Qualimap to assess coverage uniformity and apply GC-normalization algorithms during data processing [3] [1].

GC Bias Profile: PacBio HiFi Long-Read Sequencing

- Root Cause: PacBio's Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing does not rely on PCR amplification, which inherently reduces GC bias. The high accuracy of HiFi reads is achieved through circular consensus sequencing (CCS), where the same DNA molecule is sequenced multiple times to generate a highly accurate (>99.9%) consensus read [10] [11].

- Impact on Data: PacBio HiFi sequencing provides exceptionally uniform coverage and high accuracy, even in challenging GC-rich repetitive regions of the genome. This makes it particularly suitable for identifying genetic variants and assembling complex genomic areas that are problematic for short-read technologies [10].

Troubleshooting Steps for PacBio:

- The primary strength of PacBio HiFi is its minimal GC bias. The key troubleshooting step is to ensure high molecular weight DNA input to fully leverage the long-read capabilities and generate high-fidelity HiFi reads.

GC Bias Profile: Oxford Nanopore Long-Read Sequencing

- Root Cause: The bias profile is heavily dependent on the library preparation kit:

- Ligation-based Kits: Show relatively even coverage distribution across various GC contents, though a slight underrepresentation of AT-rich sequences at read termini has been observed [9].

- Rapid Transposase-based Kits: Exhibit significant coverage bias linked to the MuA transposase's recognition motif (5’-TATGA-3’). This leads to enriched cleavage in specific GC ranges (30-40%) and markedly reduced coverage in regions with 40-70% GC content [9].

- Impact on Data: The choice of kit directly influences sequencing coverage uniformity and can significantly alter observed microbial community structures in microbiome studies [9].

Troubleshooting Steps for Oxford Nanopore:

- Select ligation-based kits for quantitative applications: For studies requiring even coverage, such as microbiome quantification or variant calling, opt for ligation-based library kits over rapid transposase-based kits [9].

- Use high-accuracy basecalling: Employ high-accuracy basecalling models (e.g., HAC models) to improve per-base accuracy, which can enhance downstream taxonomic classification and analysis [9].

- Be consistent with protocols: For comparative studies, use the same library preparation method consistently across all samples to avoid introducing batch effects from different bias profiles.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of GC bias across the three major sequencing platforms.

Table 1: Platform-Specific GC Bias and Performance Metrics

| Platform | Primary Cause of GC Bias | Typical Read Accuracy | Key Strength Against GC Bias | Recommended for GC-Extreme Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | PCR amplification during library prep [1] | >99.9% [10] | Wide range of validated bioinformatic correction tools | Fair (with PCR-free protocols and bioinformatic correction) |

| PacBio HiFi | Minimal; technology is PCR-free [10] | >99.9% (Q30) [10] [11] | Highly uniform coverage and accuracy in complex regions [10] | Excellent |

| Oxford Nanopore | Transposase insertion preference (rapid kits) [9] | ~99% (Q20) and improving [10] [11] | Ligation-based kits provide more even coverage [9] | Good (with careful kit selection, preferably ligation-based) |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing GC Bias

To effectively troubleshoot GC bias, researchers must first be able to quantify it in their own data. The following workflow provides a standardized method for this assessment.

Workflow: Generating a GC Bias Profile

Purpose: To visualize and quantify the extent of GC bias in a sequencing dataset. Materials:

- Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format

- Reference genome sequence (FASTA)

- Computing resources with bioinformatics tools like BWA, SAMtools, and R/Python.

Methodology:

- Read Mapping: Align the FASTQ reads to the reference genome using an appropriate aligner (e.g., BWA for Illumina, minimap2 for long reads) [3].

- Binning and Coverage Calculation: Divide the reference genome into consecutive bins (e.g., 1 kilobase). Using tools like SAMtools, calculate the depth of coverage (number of reads overlapping) for each bin [3].

- GC Content Calculation: For each genomic bin, compute the proportion of bases that are Guanine (G) or Cytosine (C).

- Visualization: Create a scatter plot with the GC content of each bin on the x-axis and the corresponding coverage depth on the y-axis. A LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing) curve is often fitted to reveal the overall trend [3].

- Interpretation:

- Uniform Coverage: A flat line indicates minimal GC bias.

- Unimodal Bias: An arch-shaped curve, where coverage peaks at mid-range GC values and falls at both extremes, is characteristic of PCR-amplified libraries like Illumina [3].

- Kit-Specific Skew: For Oxford Nanopore, compare results from ligation versus rapid kits. The rapid kit may show a coverage drop in mid-GC regions correlated with the transposase interaction frequency [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

The table below lists key commercial solutions relevant to managing GC bias in sequencing workflows.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating GC Bias

| Product / Kit | Function / Feature | Role in Mitigating GC Bias |

|---|---|---|

| PCR-free Library Prep Kits (e.g., from Illumina) | Library construction without PCR amplification | Eliminates the primary source of amplification bias in short-read sequencing [1]. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kits | Preparation of libraries for HiFi sequencing | Enables PCR-free, long-read sequencing with high uniformity in GC-rich regions [10] [11]. |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kits (e.g., SQK-LSK110) | Ligase-based adapter attachment for Nanopore | Provides more even sequence coverage compared to transposase-based rapid kits [9]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes for tagging individual molecules | Allows bioinformatic correction for PCR duplication bias, improving quantification accuracy [1]. |

| Mechanical Shearing (e.g., Sonication) | DNA fragmentation method | Reduces sequence-specific bias introduced by enzymatic fragmentation methods [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is GC bias in next-generation sequencing (NGS)? GC bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and the guanine-cytosine (GC) content of the DNA sequence. This results in uneven sequencing coverage where genomic regions with very high or very low GC content are underrepresented in the final data [3] [1]. The bias is typically unimodal, meaning both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments are underrepresented compared to those with moderate GC content [3].

Why is GC bias a critical problem in chemogenomic research? GC bias confounds the accurate measurement of fragment abundance, which is fundamental to many NGS applications. In chemogenomic research, this can directly lead to:

- Inaccurate variant calling: Poor coverage in extreme GC regions causes false negatives (missing true variants) or false positives from sequencing artifacts [1] [12].

- Skewed abundance measurements: In metagenomic studies, species with atypical genomic GC content (e.g., F. nucleatum at 28% GC) can have their abundance under- or over-estimated, distorting community profiles [13] [2].

- Compromised copy number variation (CNV) detection: GC bias can create patterns that mimic or obscure genuine CNV events, leading to incorrect biological interpretations [3] [14].

Which sequencing workflows are most affected by GC bias? GC bias profiles vary significantly between library preparation protocols and sequencing platforms. Common Illumina workflows (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq) can show severe under-coverage outside the 45-65% GC range, while PCR-free long-read workflows like Oxford Nanopore have been shown to be less afflicted [2]. The bias is not consistent between samples or even libraries within the same experiment [3].

Can GC bias be corrected computationally? Yes, several bioinformatic correction methods exist. These often work by modeling the relationship between observed coverage and GC content across the genome, then using this model to normalize the data [3] [13]. The DRAGEN Bio-IT platform, for example, includes a dedicated GC bias correction module that is recommended for whole-genome sequencing data to improve downstream CNV calling [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing GC Bias in Your Data

Objective: To identify and quantify the presence and severity of GC bias in your NGS dataset.

Experimental Protocol:

- Calculate GC Content: Using a reference genome, divide the sequence into windows (e.g., 1 kb for WGS, or use exonic targets for WES). For each window, calculate its GC content percentage.

- Calculate Observed Coverage: Using your aligned BAM files, calculate the mean read depth for each of the same genomic windows.

- Plot and Model the Relationship: Create a scatter plot or a binned boxplot with GC content on the x-axis and mean coverage (often normalized to the median) on the y-axis. A unimodal (bell-shaped) pattern, with lower coverage at the extremes of GC content, is the hallmark of GC bias [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of GC Bias Across Sequencing Platforms [2]

| Sequencing Platform | Library Prep Key Feature | Observed Coverage Fold-Change (30% GC vs. 50% GC) | Observed Coverage Fold-Change (70% GC Vs. 50% GC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NextSeq/MiSeq | PCR-amplified libraries | >10-fold decrease | ~5-fold decrease |

| Illumina HiSeq | PCR-amplified libraries | Moderate decrease | Moderate decrease |

| Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) | PCR-free | Moderate decrease | Moderate decrease |

| Oxford Nanopore | PCR-free | No significant bias | No significant bias |

Mitigating GC Bias in Library Preparation

Objective: To minimize the introduction of GC bias during the wet-lab stages of NGS.

Experimental Protocol:

- Optimize PCR (if amplification is necessary):

- Reduce Cycle Number: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles required for library amplification [1] [15].

- Use High-Fidelity Polymerases: Select polymerases engineered for unbiased amplification.

- Employ PCR Additives: Use additives like betaine or trimethylammonium chloride to help amplify GC-rich or GC-poor regions, respectively [2] [16].

- Consider PCR-Free Library Preparation: Whenever input DNA is sufficient, opt for PCR-free library prep kits. This is one of the most effective ways to eliminate amplification-related GC bias [1] [16].

- Optimize Fragmentation: Mechanical fragmentation (e.g., sonication) has generally demonstrated improved coverage uniformity compared to some enzymatic methods [1].

- Use Unique Molecular Indices (UMIs): Incorporating UMIs before amplification helps distinguish true biological duplicates from PCR duplicates, improving quantification accuracy in biased data [1].

Table 2: Performance of Computational GC Bias Correction Methods [13]

| Correction Method | Application Context | Key Principle | Impact on Abundance Estimation (Relative Error) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuaCAMOLE | Metagenomics (Alignment-free) | Compares species within a single sample to estimate GC-dependent efficiency. | Reduces error to <1% in simulated data with known bias. |

| BEADS/LOESS Model | DNA-seq, CNV Analysis | Models unimodal GC-coverage relationship to correct counts in genomic bins. | Significantly improves precision in copy number estimation [3]. |

| DRAGEN GC Correction | WGS, WES | Corrects coverage based on GC bins; uses smoothing for robust correction. | Recommended for downstream CNV analysis to remove bias-driven artifacts [14]. |

Correcting for GC Bias in Bioinformatics Analysis

Objective: To computationally remove GC bias from sequencing data post-alignment to obtain more accurate variant calls and abundance estimates.

Experimental Protocol for a Typical Correction Workflow: This workflow can be implemented using tools like DRAGEN [14] or custom scripts based on the LOESS model [3].

GC Bias Correction Workflow

Key Steps:

- Bin the Genome: The reference genome is divided into bins (e.g., 1 kb for WGS, or exome capture targets for WES) [3] [14].

- Calculate GC and Coverage: For each bin, compute the GC content percentage and the mean read depth from the BAM file.

- Fit a Regression Model: Model the relationship between coverage and GC content using a LOESS fit or similar smoothing function. This establishes the expected "biased" coverage for a given GC value [3].

- Compute and Apply Correction: For each bin, a correction factor is derived from the model (e.g., the inverse of the observed/expected ratio). This factor is then applied to the raw coverage values to generate a normalized, bias-corrected coverage profile [3] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Managing GC Bias

| Item | Function | Considerations for GC Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Betaine | PCR Additive | Destabilizes secondary structures in GC-rich regions, improving their amplification efficiency [2] [16]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Library Construction | Eliminates the primary source of amplification bias, providing more uniform coverage across GC extremes [1] [16]. |

| Mechanical Shearing Device | DNA Fragmentation | Provides more random and uniform fragmentation compared to some enzymatic methods, reducing sequence-dependent bias [1]. |

| UMI Adapters | Library Barcoding | Allows bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates, ensuring quantitative accuracy for variant calling and abundance estimation [1]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Enzyme | Library Amplification | Engineered polymerases offer better performance and uniformity when amplifying difficult templates, including those with extreme GC content [15] [16]. |

Impact of Library Prep on GC Bias

Proactive Strategies: Methodologies to Minimize GC Bias from Sample to Sequence

FAQs on GC-Bias in NGS Sequencing

What is GC-bias and why is it a critical concern in chemogenomic NGS research?

GC-bias refers to the uneven sequencing coverage of genomic regions due to their guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotide content. Regions with extremely high (>60%) or low (<40%) GC content often show reduced sequencing efficiency, leading to inaccurate representation in your data [1]. This bias is particularly critical in chemogenomic research because it can:

- Skew relative taxon abundances in microbial community studies, leading to incorrect conclusions about which species dominate under different chemical treatments [16].

- Hinder variant detection, potentially causing false negatives in regions with poor coverage or false positives from sequencing artifacts, compromising drug target identification [1].

- Limit reproducibility and comparability between experiments and laboratories, as the exact shape of the GC bias curve can vary between samples and sequencing runs [3].

My NGS data shows uneven coverage and high duplicate reads. What steps in my workflow are most likely to blame?

This is a common symptom of biases introduced during sample and library preparation. The most likely culprits are:

- DNA Extraction Method: The choice of DNA extraction protocol can significantly skew which species and genomic regions are recovered. One study found that bias due to DNA extraction protocols resulted in error rates of over 85% in some microbiome samples [16]. Phenol-chloroform methods may yield more DNA but with higher variability, while some commercial kits might underrepresent certain taxa [17].

- PCR Amplification during Library Prep: This is a major source of GC-bias. PCR preferentially amplifies fragments with "optimal" GC content, leading to under-representation of both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments. This results in uneven coverage and a high rate of PCR duplicate reads, which are multiple copies of the exact same DNA fragment [1] [3].

- Fragmentation Method: The method used to fragment DNA for library construction can introduce sequence-dependent biases. Studies have shown that mechanical fragmentation methods (e.g., sonication) generally provide more uniform coverage across regions with varying GC content compared to some enzymatic fragmentation methods [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low DNA Yield and Quality from Challenging Samples

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Cause | Specific Issue | Solution and Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Storage | Sample degradation or bacterial overgrowth. | Preserve samples immediately after collection using stabilization chemistry or deep freezing. For blood, use EDTA tubes and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [16] [18] [19]. |

| Cell Lysis | Inefficient lysis due to tough cellular structures (e.g., plant cell walls, bacterial spores, exoskeletons). | Optimize lysis by combining mechanical (e.g., bead beating) and chemical (e.g., detergents, Proteinase K) methods. Incubate for 1-3 hours for thorough digestion [16] [18] [19]. |

| Inhibitor Contamination | Presence of heme (blood), polyphenols (plants), or mucins (saliva) that co-purify with DNA. | Use sample-specific kits designed to remove these inhibitors. Incorporate additional wash steps and use magnetic bead-based or other specialized purification technologies [18]. |

Problem: High GC-Bias and PCR Duplication in Sequencing Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Cause | Impact on Data | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR Protocols | Exponential under-representation of GC-rich and GC-poor fragments, creating a unimodal coverage curve. Duplicate reads reduce usable sequence data [1] [3]. | Use a high-fidelity PCR mastermix with bias-reducing additives like betaine for GC-rich regions. Minimize the number of amplification cycles [1] [16]. |

| Library Preparation Method | Amplification bias is inherent to PCR-dependent library prep. | Switch to PCR-free library preparation workflows. This requires higher input DNA (>500 ng - 2 µg) but effectively eliminates amplification bias [1] [16]. |

| Size Selection | Presence of short fragments can dominate the library and skew coverage. | Implement rigorous size selection to remove short fragments. For long-read sequencing, use kits like the Short Read Eliminator (SRE) to retain only high-molecular-weight DNA [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Minimization

Protocol: Evaluating DNA Extraction Methods for Microbiome Studies

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing extraction methods for complex microbial communities [17].

Objective: To select a DNA extraction method that provides the most representative profile for your specific sample type while minimizing GC-bias.

Materials:

- Your sample material (e.g., soil, stool, chemical-treated culture)

- Candidate DNA extraction kits (e.g., phenol-chloroform, commercial bead-beating kits)

- Mock microbial community with known ratios of species spanning a range of GC content

- Standard tools for QC (e.g., Qubit, Bioanalyzer)

- Access to 16S rRNA gene sequencing or shotgun metagenomics

Method:

- Parallel Processing: Split the same sample aliquot and process it simultaneously using the different DNA extraction methods you are evaluating. Include the mock community as a control.

- Standardized Elution: Elute all DNA in the same volume to allow for direct comparison of yield.

- Quality Control: Measure DNA concentration, purity (A260/A280), and fragment size distribution.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Perform sequencing on all extracts simultaneously using the same sequencing run to avoid batch effects.

- Data Comparison:

- For the mock community, assess which method yields results closest to the expected theoretical composition.

- For the environmental sample, compare metrics like alpha diversity (richness), beta diversity (community similarity), and the relative abundance of key taxa.

Expected Outcome: No single method is universally superior. The "best" method maximizes yield, minimizes inter-sample variability, and most accurately recovers the known mock community composition for your sample type [17].

Workflow: Integrated Sample Prep to Minimize GC-Bias

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow that integrates multiple strategies to minimize GC-bias from sample to sequence.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their specific roles in overcoming challenges in DNA extraction and handling for NGS.

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Workflow | Specific Role in Overcoming Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Stabilization Kits (e.g., Oragene for saliva) | Preserves sample integrity at room temperature post-collection. | Prevents microbial community shifts and nucleic acid degradation, reducing a major source of pre-extraction bias [16] [18]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Chemistry (e.g., PVP for plants, specialized wash buffers) | Added during lysis or wash steps of DNA extraction. | Binds to and removes contaminants like polyphenols and humic acids that can inhibit polymerases and lead to uneven amplification [18]. |

| Bead Beating Tubes with Heterogeneous Bead Sizes | Used for mechanical cell disruption. | Ensures efficient lysis of a wide range of microbial cell walls (Gram-positive, Gram-negative, spores), preventing under-representation of tough-to-lyse species [16]. |

| Bias-Reducing PCR Mastermix | Used during the amplification step of library preparation. | Contains polymerases and additives (e.g., betaine) that improve amplification efficiency across a wider range of GC contents, flattening coverage curves [1] [16]. |

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kits | Creates sequencing libraries without an amplification step. | Eliminates PCR amplification bias, the primary cause of GC-bias, leading to the most uniform coverage [1]. |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., SPRI beads) | Used to selectively purify DNA fragments within a target size range. | Removes short fragments and adapter dimers, which can improve assembly and ensure that coverage biases are not confounded by fragment length [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is GC-bias in NGS library preparation, and why is it a problem? GC-bias refers to the under-representation or over-representation of genomic regions with high or low guanine-cytosine (GC) content in your sequencing data. This occurs during library preparation steps like PCR amplification [15]. In chemogenomic research, this bias can skew results, leading to inaccurate conclusions about compound-gene interactions and missed drug targets.

Which library preparation steps are most prone to introducing GC-bias? The primary steps where GC-bias is introduced are:

- Fragmentation: Uneven fragmentation of GC-rich regions [15].

- Amplification (PCR): Overamplification artifacts and inefficient polymerase activity in hard-to-amplify regions [15].

How can I troubleshoot a suspected GC-bias issue in my data?

- Check Data Metrics: Look for uneven coverage in GC-rich regions and a high duplicate read rate [15].

- Review Protocols: Trace the issue back to fragmentation and amplification steps [15].

- Verify Input Quality: Ensure your input DNA is not degraded, as this can exacerbate bias [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Library Preparation Failures

Table 1: Common Issues and Corrective Actions for Low-Bias Workflows

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions for GC-Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low library complexity; smear in electropherogram [15] | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [15] | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of UV absorbance only [15]. |

| Fragmentation | Unexpected fragment size distribution; skewed results from GC-rich regions [15] | Over- or under-shearing, which can disproportionately affect regions with high secondary structure [15] | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragment size distribution post-fragmentation [15]. |

| Amplification / PCR | High duplicate rate; overamplification artifacts; bias [15] | Too many PCR cycles; inefficient polymerase; primer exhaustion [15] | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use high-fidelity polymerases designed for GC-rich templates; optimize primer design [15]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of small fragments; sample loss [15] | Wrong bead-to-sample ratio; overly aggressive size selection [15] | Precisely follow bead cleanup protocols; avoid over-drying beads; use optimized bead ratios to minimize loss of target fragments [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Mitigating GC-Bias

The following diagram illustrates a generalized NGS library preparation workflow, highlighting critical steps for bias mitigation.

Detailed Methodology:

Input Quality Control (QC):

- Extract nucleic acids from your biological sample (e.g., cells, tissue) [21].

- Quantify using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) for accuracy. Assess purity via spectrophotometry (260/280 and 260/230 ratios). A 260/280 ratio of ~1.8 is ideal for pure DNA [15].

- Verify integrity using an instrument like the BioAnalyzer. Degraded samples should not be processed further.

Fragmentation & Adapter Ligation:

- Fragment DNA via enzymatic or physical shearing to the desired insert size [21].

- Critical Step: Optimize fragmentation time and enzyme concentration to ensure uniform shearing of GC-rich regions and prevent a skewed size distribution [15].

- Ligate adapters to fragment ends. Titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio to maximize yield while minimizing adapter-dimer formation [15].

Library Amplification:

- Amplify the library via PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing [21].

- Critical Step: Use a minimal number of PCR cycles and select a high-fidelity polymerase specifically engineered for efficient amplification of GC-rich templates. This is crucial for reducing bias and duplication artifacts [15].

Purification, Cleanup, and Final QC:

- Purify the library using magnetic bead-based cleanup to remove enzymes, salts, and unwanted short fragments like adapter dimers [15] [21].

- Critical Step: Precisely follow the recommended bead-to-sample ratio to prevent loss of desired fragments. Avoid over-drying the bead pellet [15].

- Perform Final QC to confirm library concentration and size distribution (e.g., via BioAnalyzer) before sequencing [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Low-Bias Workflows

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Reducing GC-Bias |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies library fragments during PCR. | Select enzymes specifically validated for robust performance with high-GC templates to ensure even coverage [15]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Purifies and size-selects nucleic acids after various preparation steps. | Use precise bead-to-sample ratios to prevent loss of specific fragments; avoid over-drying [15]. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes | Shears DNA into fragments of the desired length for sequencing. | Optimize enzymatic fragmentation conditions to achieve uniform shearing across all genomic regions, regardless of GC content [15]. |

| Double-Sided Adapters | Attached to DNA fragments to allow binding to the flow cell and primer hybridization. | Titrate the adapter concentration to find the optimal ratio that minimizes adapter-dimer formation and maximizes ligation efficiency [15]. |

The Role of PCR-Free Libraries and Advanced Polymerase Mixtures

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is GC bias in NGS sequencing, and why is it a problem for chemogenomic research? GC bias refers to the uneven sequencing coverage of genomic regions based on their guanine (G) and cytosine (C) content. Regions with extremely high (>60%) or low (<40%) GC content often show reduced sequencing efficiency, leading to inaccurate representation in the data [1]. In chemogenomics, this can cause false-negative or false-positive variant calls, obscure genuine copy number variations, and compromise the integrity of downstream analyses and drug target identification [1] [2].

2. How do PCR-free libraries help in reducing GC bias? PCR-free library preparation workflows eliminate the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification step. Since PCR is a major contributor to GC bias—as it preferentially amplifies fragments with "optimal" GC content—bypassing it prevents this selective amplification [1] [22]. This results in more uniform genome coverage, reduced duplicate reads, and a more accurate representation of all genomic regions, including those with extreme GC content [23] [24].

3. If PCR-free methods are superior, when should I consider using advanced polymerase mixtures? PCR-free protocols require a higher amount of input DNA (often >100 ng), which is not always available, such as with clinical or degraded samples [1] [25] [23]. In these cases, using advanced, high-fidelity polymerase mixtures is a practical alternative. Modern enzymes are engineered to be more robust against complex secondary structures in GC-rich templates and exhibit reduced amplification bias compared to older polymerases like Phusion [26] [27]. They are a crucial mitigation strategy when PCR-free workflows are impractical.

4. What are the key trade-offs between PCR-free and PCR-based libraries with advanced polymerases? The choice involves balancing input requirements, bias, and workflow simplicity. The table below summarizes the core considerations:

| Feature | PCR-Free Libraries | PCR-Based Libraries with Advanced Polymerases |

|---|---|---|

| GC Bias Reduction | Excellent - eliminates PCR amplification bias [23] [24] | Good - significantly reduced bias with modern enzymes [26] [27] |

| Input DNA Requirement | High (e.g., 25-1000 ng) [25] [23] | Low to very low (e.g., 1 pg - 100 ng) [25] |

| Library Workflow | Simplified, faster, lower cost by removing PCR step [24] | Includes additional steps for library amplification [15] |

| Ideal Use Cases | High-input WGS, sensitive variant calling, de novo assembly [23] | Low-input samples, FFPE DNA, targeted sequencing, cfDNA [25] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor or Uneven Coverage in GC-Rich or GC-Poor Regions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Use of a suboptimal polymerase.

- Solution: Switch to a polymerase mixture specifically engineered for high GC content. These enzymes often contain additives in their buffer systems that help denature stable secondary structures, enabling more uniform amplification of challenging templates [27].

- Protocol: When setting up a PCR for library amplification, replace a standard polymerase with a specialized one (e.g., PCRBIO Ultra Polymerase or a VeriFi high-fidelity mix). Follow the manufacturer's protocol, which may include recommendations for adjusted denaturation temperatures or times [27].

Cause 2: Over-amplification during library prep.

- Solution: Minimize the number of PCR cycles. The duplication rate and amplification bias increase dramatically with each additional cycle [15].

- Protocol: Determine the minimum number of PCR cycles required to generate sufficient library yield. A great alternative is to use only a single PCR cycle, which creates fully double-stranded molecules for sequencing with minimal bias [26].

Cause 3: Inefficient fragmentation method.

- Solution: Mechanical fragmentation methods (e.g., sonication) have generally demonstrated improved coverage uniformity across varying GC content compared to enzymatic (e.g., tagmentation) methods, which can be susceptible to sequence-dependent biases [1].

- Protocol: For the most unbiased results, use a sonication-based fragmentation protocol. If using an enzymatic method, ensure it is optimized and validated for even fragmentation across different GC contexts.

Problem: Low Library Yield from Precious Low-Input Samples

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: PCR-free protocol used with insufficient DNA.

- Solution: For samples where input DNA is limited, a PCR-free workflow is not feasible. Opt for a PCR-based kit designed for low-input samples and pair it with a high-fidelity, bias-resistant polymerase [25].

- Protocol: Use a specialized low-input kit (e.g., xGen ssDNA & Low-Input DNA Library Prep Kit). Carefully quantify input DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) rather than UV absorbance to ensure accuracy [25] [15].

Cause 2: PCR inhibition or inefficiency.

- Solution: Re-purify the input DNA to remove contaminants like salts or phenol that can inhibit polymerase activity. Always use a high-fidelity polymerase known for robustness [26] [15].

- Protocol: Perform a column- or bead-based clean-up of the DNA sample before library construction. Check purity via spectrophotometry (260/230 and 260/280 ratios) [15].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points for selecting the appropriate strategy to mitigate GC bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and kits for managing GC bias in NGS workflows.

| Product Name / Type | Function / Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep [23] | Library preparation kit that eliminates PCR amplification to prevent associated biases. | Input: 25-300 ng; Assay time: ~1.5 hrs; Ideal for human WGS and de novo assembly. |

| VeriFi Library Amplification Mix [27] | Polymerase mix for NGS library amplification designed to reduce GC bias. | High-fidelity enzyme; Provides more unique reads and reduced bias compared to standard mixes. |

| PCRBIO Ultra Polymerase [27] | Polymerase engineered for robust amplification of challenging templates, including GC-rich ones. | Effective on GC-rich templates (up to 80% GC), and inhibitor-tolerant. |

| xGen ssDNA & Low-Input DNA Library Prep Kit [25] | Library preparation kit designed for very low-input and challenging samples. | Input: 10 pg - 250 ng; Enables sequencing of low-quality/degraded DNA when PCR-free is not an option. |

| Hieff NGS Ultima Pro PCR Free Kit [24] | A third-party PCR-free library prep kit that streamlines the preparation process. | Eliminates PCR duplicates and reduces error rates for more uniform coverage. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [1] | Short DNA barcodes ligated to each fragment before any amplification steps. | Allows bioinformatic distinction between true biological duplicates and PCR duplicates, mitigating the impact of amplification bias. |

In chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) research, a significant technical challenge is GC bias, where the proportion of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in a DNA region influences its amplification efficiency and, consequently, its representation in sequencing results. This bias manifests as a unimodal curve: both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments are underrepresented in sequencing data, which can confound copy number estimation and other quantitative analyses [3]. A primary cause of this bias is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) step during library preparation [3]. GC-rich sequences (typically defined as over 60% GC content) form stable secondary structures and exhibit higher melting temperatures, causing polymerases to stall and leading to inefficient amplification [28]. To overcome this, wet-lab interventions employing PCR additives are critical. These reagents, such as betaine and tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC), work by altering the physicochemical environment of the PCR, facilitating the denaturation of stubborn DNA structures and promoting uniform amplification across templates of varying GC content [29] [30]. This guide provides detailed troubleshooting and FAQs for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to mitigate GC-bias in their chemogenomic studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does betaine improve the amplification of GC-rich DNA in PCR?

Betaine (N,N,N-trimethylglycine) is a kosmotropic molecule that improves the amplification of GC-rich DNA by reducing the formation of secondary structures and equalizing the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA. GC-rich regions have a higher Tm due to the three hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs compared to the two in A-T pairs. This can lead to incomplete denaturation and the formation of hairpins or other structures that block polymerase progression. Betaine penetrates the DNA and weakens the stacking forces between base pairs, effectively reducing the Tm difference between GC-rich and AT-rich regions. This promotes more uniform denaturation and allows the polymerase to synthesize through previously challenging sequences [29].

Q2: Are there PCR additives that can work better than betaine for some targets?

Yes, research indicates that other additives can outperform betaine for specific GC-rich targets. A 2009 study found that ethylene glycol and 1,2-propanediol could rescue amplification for a larger percentage of 104 tested GC-rich human genomic amplicons compared to betaine [30]. While 72% of amplicons worked with betaine alone, 90% worked with 1,2-propanediol and 87% with ethylene glycol. Interestingly, betaine sometimes exhibited a PCR-inhibitive effect, causing some reactions that worked with the other additives to fail when betaine was added [30]. The mechanism of these newer additives is not fully understood but is believed to function differently from betaine.

Q3: What is the role of TMAC in PCR, and how does it differ from betaine?

While betaine is primarily used to destabilize secondary structures in the DNA template, Tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC) functions mainly as a specificity enhancer. TMAC increases the stringency of primer annealing by equalizing the binding strength of A-T and G-C base pairs, which helps prevent mispriming to off-target sites with similar sequences [28]. This is particularly useful in reducing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation. Betaine and TMAC can be considered complementary tools: betaine addresses template structure issues, while TMAC addresses primer-binding fidelity.

Q4: How does GC-bias in PCR affect my chemogenomic NGS data?

GC-bias introduces a technical artifact where fragment coverage depends on the GC content of the DNA region. This bias can dominate the biological signal of interest, such as in copy number variation (CNV) analysis using DNA-seq [3]. The dependence is unimodal, meaning both very high-GC and very low-GC (high-AT) regions are underrepresented in the sequencing results. Since this bias pattern is not consistent between samples or even libraries within the same experiment, it can lead to inaccurate comparisons unless corrected. Evidence suggests that PCR is a major contributor to this bias, making the optimization of the PCR step crucial for generating quantitatively accurate NGS data [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product or Low Yield | Polymerase stalled by GC-rich secondary structures | - Use a polymerase optimized for GC-rich templates [28].- Include 0.5 M to 2.5 M betaine in the reaction [29] [31].- Increase denaturation temperature or duration [32]. |

| Insufficient denaturation of GC-rich DNA | - Increase denaturation temperature (e.g., to 98°C) or time [32] [33].- Ensure reagents are mixed thoroughly to avoid density gradients [32]. | |

| Non-Specific Products / Multiple Bands | Low annealing stringency leading to mispriming | - Increase annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments [32] [33].- Include 1-10% DMSO or TMAC to increase primer specificity [28].- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase [32] [34]. |

| Excessive Mg2+ concentration | - Optimize Mg2+ concentration using a gradient from 1.0 to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments [32] [28]. | |

| Smeared Bands on Gel | Degraded DNA template or contaminants | - Re-purify template DNA to remove inhibitors like phenol or salts [32] [33].- Use additives like BSA (10-100 μg/ml) to bind contaminants [31]. |

| Accumulation of amplifiable contaminants from prior PCRs | - Use a new set of primers with different sequences that do not interact with the accumulated contaminants [34].- Separate pre- and post-PCR laboratory areas [34]. |

Quantitative Data on PCR Additives

Table 1: Common PCR Additives for GC-Rich Amplification

| Additive | Typical Final Concentration | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | 0.5 M - 2.5 M [29] [31] | Equalizes DNA melting temps; disrupts secondary structure [29] | Most common additive for GC-rich DNA; can be inhibitive for some targets [30]. |

| DMSO | 1% - 10% [31] [28] | Disrupts secondary DNA structure; increases specificity | High concentrations can inhibit polymerase; may require Ta reduction [32] [28]. |

| Formamide | 1.25% - 10% [31] | Denaturant; increases primer stringency | Can improve specificity; concentration must be optimized [31] [28]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | ~1.075 M [30] | Lowers DNA melting temperature; enhances yield | In one study, rescued 87% of GC-rich amplicons vs. 72% for betaine [30]. |

| 1,2-Propanediol | ~0.816 M [30] | Lowers DNA melting temperature; enhances yield | In one study, rescued 90% of GC-rich amplicons vs. 72% for betaine [30]. |

| TMAC | Not specified in results | Increases primer annealing stringency | Reduces non-specific binding and primer-dimer formation [28]. |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | Varies (partial replacement for dGTP) | dGTP analog that reduces base stacking | Does not stain well with ethidium bromide [28]. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Additives on 104 GC-Rich Amplicons

This data, derived from a study on 104 human genomic amplicons (60-80% GC content), demonstrates the relative effectiveness of different additives [30].

| Additive Condition | Percentage of Amplicons Successfully Amplified |

|---|---|

| No Additive | 13% |

| Betaine Alone | 72% |

| Ethylene Glycol Alone | 87% |

| 1,2-Propanediol Alone | 90% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard PCR Setup with Betaine

This protocol outlines a standard method for setting up a PCR reaction with betaine to amplify GC-rich targets [31].

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA template (1-1000 ng)

- Forward and reverse primers (20-50 pmol each)

- 10X PCR buffer (supplied with polymerase)

- dNTP mix (200 μM final concentration)

- MgCl2 (1.5 mM final concentration, adjust if needed)

- Betaine (5 M stock solution)

- DNA polymerase (0.5-2.5 units per 50 μL reaction)

- Sterile distilled water

Methodology:

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: Thaw all reagents on ice. For a 50 μL reaction, combine the following in a 0.2 mL thin-walled PCR tube in the listed order:

- Sterile water (Q.S. to 50 μL)

- 10X PCR buffer: 5 μL

- dNTP mix (10 mM): 1 μL

- MgCl2 (25 mM): variable (e.g., 0.8 μL for 1.5 mM final, adjust as needed)

- Forward primer (20 μM): 1 μL

- Reverse primer (20 μM): 1 μL

- Betaine (5 M stock): 5 μL (for 0.5 M final) to 25 μL (for 2.5 M final)

- DNA template: variable (e.g., 0.5 μL of 2 ng/μL genomic DNA)

- DNA polymerase: 0.5-1 μL

- Mix Thoroughly: Gently mix the reaction by pipetting up and down at least 20 times. Briefly centrifuge to collect the contents at the bottom of the tube.

- Thermal Cycling: Place tubes in a thermal cycler preheated to the initial denaturation temperature. A typical cycling program is:

- Initial Denaturation: 94-98°C for 2-5 minutes

- 25-40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94-98°C for 20-30 seconds

- Annealing: 50-72°C for 20-30 seconds (optimize based on primer Tm)

- Extension: 68-72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon

- Final Extension: 68-72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Hold: 4-10°C

Protocol 2: Systematic Optimization of Additives and Mg2+

This protocol provides a strategy for testing different additives and Mg2+ concentrations to rescue a failed GC-rich PCR.

Materials and Reagents:

- All reagents from Protocol 1.

- Additional additives: DMSO, formamide, ethylene glycol, 1,2-propanediol, etc.

- MgCl2 stock solution (e.g., 25 mM or 50 mM).

Methodology:

- Master Mix Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing all common components (water, buffer, dNTPs, primers, template, polymerase). Omit Mg2+ and additives.

- Aliquot for Optimization: Distribute the master mix into multiple PCR tubes.

- Variable Additions:

- Additive Screen: To different tubes, add a single additive from Table 1 at its standard concentration. Include one tube with no additive as a control.

- Mg2+ Gradient: For a promising additive (or no additive), set up a separate Mg2+ gradient. Add MgCl2 to achieve final concentrations spanning 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments.

- Run PCR and Analyze: Perform thermal cycling and analyze the results by agarose gel electrophoresis. Identify the condition that provides the strongest specific product with the least background.

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing PCR amplification of GC-rich sequences, integrating the use of additives.

Optimization Workflow for GC-Rich PCR

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Overcoming GC-Bias

| Item | Function in GC-Rich PCR | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Affinity DNA Polymerases | Polymerases with high processivity are less likely to stall at complex secondary structures. | OneTaq DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [28]. |

| Specialized PCR Buffers | Buffers are often supplied with GC Enhancers containing a proprietary mix of additives. | OneTaq GC Buffer, Q5 GC Enhancer [28]. |

| PCR Additives | Chemical reagents that modify DNA melting behavior or polymerase specificity. | Betaine, DMSO, formamide, ethylene glycol, 1,2-propanediol, TMAC [29] [30] [31]. |

| Magnesium Salts (Mg2+) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity; concentration critically affects yield and specificity. | MgCl2 or MgSO4 (check polymerase preference) [32] [28]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Polymerases inactive at room temperature prevent non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. | Various commercially available hot-start enzymes [32] [34]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Instrument that allows testing a range of annealing or denaturation temperatures in a single run. | Essential for efficient optimization of annealing temperature (Ta) [32] [33]. |

Incorporating Spike-In Controls for Normalization Across GC Ranges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental purpose of a spike-in control in NGS experiments? Spike-in controls are synthetic DNA or RNA sequences of known identity and quantity added to your samples before library preparation. Their primary purpose is to provide an external reference to correct for technical variation that occurs during processing, enabling accurate normalization and quantification, especially when global changes in the total amount of the target molecule (e.g., RNA, DNA, or histones) are suspected between experimental conditions [35] [36]. They are essential for detecting genuine global changes that standard normalization methods, which assume constant total output, would obscure [35].

2. Why are spike-in controls particularly important for overcoming GC bias? GC bias—the underrepresentation of both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments—is a prevalent issue in NGS that can confound analyses like copy number variation and differential expression [3] [1]. Spike-in controls are manufactured with a range of GC contents. By monitoring the recovery of these known sequences, you can directly measure and computationally correct for the sequence-dependent biases introduced during library preparation and sequencing, leading to more uniform coverage and accurate quantification across all genomic regions [37] [3].

3. When is it absolutely necessary to use spike-in controls? You should strongly consider spike-in controls in the following scenarios [35]:

- Global changes are expected: When comparing conditions where the total cellular RNA, DNA, or histone content may change (e.g., during cellular differentiation, drug treatment, or in disease states).

- ChIP-seq for histone modifications: When the global levels of a histone modification may vary between samples, as standard normalization would incorrectly show depletion in regions where the mark is unchanged [35] [36].

- Copy number variation (CNV) analysis: To accurately determine chromosome ploidy and identify amplified or deleted genomic regions without the confounding effect of GC bias [35] [1].

- Challenging sample types: For low-input samples, such as biofluids or FFPE tissues, where technical variation is high [38].

4. My spike-in controls show uneven recovery across the GC range. What does this indicate? Uneven recovery of spike-ins across the GC spectrum is a direct measurement of your library's GC bias. A unimodal pattern, where both low-GC and high-GC controls are underrepresented, is a classic signature often attributed to PCR amplification bias [3]. This data should be used to inform bioinformatic correction algorithms for your entire dataset.

5. Can I use the same spike-in control for all my different NGS applications? Not typically. The ideal spike-in control should closely mimic the endogenous molecules you are studying.

- RNA-seq: Use exogenous RNA controls (e.g., ERCC standards) that are polyadenylated and have a range of lengths and GC contents [37].

- ChIP-seq: Use chromatin or synthetic nucleosomes from a different species (e.g., Drosophila chromatin in human samples) that contain the epitope of interest [35] [36].

- DNA-seq: Use synthetic DNA sequences with no homology to your target genome and a representative GC content [35] [39]. Always ensure the spike-in sequences are distinct from your experimental genome to prevent misalignment.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Normalization Despite Spike-In Use

Symptoms: After spike-in normalization, results do not align with orthogonal validation methods (e.g., qPCR, Western blot), or the normalized data shows unexpected global trends.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Improper spike-in addition | Check logs for consistent volume added per cell/equivalent. Verify the spike-in to sample chromatin/RNA ratio is consistent across samples [36]. | Always add spike-in in an amount proportional to the number of cells. Use precise pipetting and master mixes to reduce error [36]. |

| Failed ChIP on spike-in chromatin | Check the number of reads mapping to the spike-in genome. Extremely low counts indicate a problem [36]. | Ensure the antibody recognizes the epitope in both the sample and spike-in chromatin. Titrate the antibody for optimal efficiency. |

| Incorrect computational alignment | Check the alignment strategy. Were reads aligned to a combined reference genome (sample + spike-in) or separately? [36] | Always align sequencing reads to a concatenated reference genome containing both the target and spike-in sequences to ensure competitive and accurate mapping [36]. |

| Spike-in concentration is suboptimal | Check the percentage of reads mapping to spike-ins. If it's too high, it wastes sequencing depth; if too low, normalization is unreliable [38]. | Titrate the spike-in amount in a pilot experiment. Aim for a read percentage (e.g., 2-10%) that provides robust detection without dominating the library [37] [38]. |

Problem: Low Library Yield After Adding Spike-In Controls

Symptoms: Final library concentration is unexpectedly low, potentially impacting sequencing depth.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in oligonucleotide contaminants | Analyze the library profile on a BioAnalyzer or TapeStation. Look for a sharp peak consistent with adapter dimers [15]. | Re-purify the spike-in oligonucleotides before use, using PAGE purification or similar high-stringency methods. |

| Inhibition of enzymatic steps | Check the purity of your sample and spike-in solution using absorbance ratios (260/280, 260/230) [15]. | Re-purify the input sample and the spike-in controls to remove salts, phenol, or other inhibitors. Ensure all buffers are fresh. |

| Overly aggressive size selection | Review the bead-based cleanup ratios. A high bead-to-sample ratio can exclude desired fragments [15]. | Optimize the bead clean-up ratio to maximize the recovery of your target fragment size range. |

Problem: High Duplication Rates and Amplification Bias

Symptoms: High percentage of PCR duplicate reads and/or skewed coverage in regions of extreme GC content.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Too many PCR cycles | Check the library preparation protocol and the number of amplification cycles. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles. If yield is insufficient, optimize the initial ligation or use PCR enzymes designed for high-GC content [15] [1]. |

| Suboptimal input DNA/RNA | Use a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) for accurate quantification of input material. | Increase the amount of input material if possible. For very precious samples, use library kits specifically designed for low input. |

| PCR bias from GC content | Use QC tools like FastQC or Picard to assess the relationship between coverage and GC content [1]. | Consider PCR-free library preparation workflows. Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish biological duplicates from technical PCR duplicates [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Using Chromatin Spike-Ins for ChIP-seq Normalization

This protocol is adapted from methods used to correctly quantify global changes in histone modifications, such as H3K79me2 inhibition [35] [36].