Ortholog Identification for Target Validation: A Cross-Species Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging ortholog identification to validate therapeutic targets across species.

Ortholog Identification for Target Validation: A Cross-Species Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging ortholog identification to validate therapeutic targets across species. It covers the foundational principles of orthology and its critical role in establishing disease relevance and predicting essential genes. The content details state-of-the-art computational methods and databases, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex gene families and big data, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks to assess prediction accuracy and functional conservation. By synthesizing current methodologies and applications, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and success rate of preclinical target validation in biomedical research.

The Critical Link: Why Orthologs are Fundamental to Target Validation

Defining Orthologs, Paralogs, and the Ortholog Conjecture for Functional Prediction

In the field of comparative genomics and cross-species target validation, accurately identifying evolutionary relationships between genes is fundamental. The terms orthologs and paralogs describe different types of homologous genes—genes related by descent from a common ancestral sequence [1] [2]. Understanding this distinction is critical for predicting gene function in newly sequenced genomes and for selecting appropriate targets for drug development research across species.

Homology refers to biological features, including genes and their products, that are descended from a feature present in a common ancestor. All homologous genes share evolutionary ancestry, but they can be separated through different evolutionary events [1]. The proper classification of these homologous relationships forms the basis for reliable functional annotation transfer, a process essential for leveraging model organism research to understand human disease mechanisms and identify therapeutic targets.

Defining Orthologs and Paralogs

Conceptual Definitions

- Orthologs: Genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation events [1] [2]. Orthologs typically retain the same function during evolution [3].

- Paralogs: Genes related by gene duplication events within a genome [1] [2]. Paralogs often evolve new functions, though they may retain similar functions, especially if the duplication event was recent [3].

The diagram below illustrates the evolutionary relationships between orthologs and paralogs:

Figure 1: Evolutionary relationships showing orthologs and paralogs. Orthologs (blue) arise from speciation events, while paralogs (red) arise from gene duplication events. All genes shown are homologs, sharing common ancestry [1].

Refined Classification: Inparalogs and Outparalogs

Paralogs can be further categorized based on the timing of duplication events relative to speciation:

- Inparalogs: Paralogs that arise from duplication events after a speciation event of interest. These are co-orthologs to a single-copy gene in another species [4] [5].

- Outparalogs: Paralogs that arise from duplication events before a speciation event. These are not considered orthologs according to standard definitions [4].

This distinction is particularly important for functional prediction, as inparalogs are more likely to retain similar functions compared to outparalogs, which have had more evolutionary time to diverge.

The Ortholog Conjecture and Modern Evidence

The Traditional Ortholog Conjecture

The ortholog conjecture is a fundamental hypothesis in comparative genomics that proposes orthologous genes are more likely to retain similar functions than paralogous genes [5]. This conjecture has guided computational gene function prediction for decades, with the assumption that orthologs evolve functions more slowly than paralogs [6]. This principle has been embedded in many functional annotation pipelines, where orthologs are preferentially used to transfer functional annotations from well-studied model organisms to newly sequenced genomes.

Contemporary Evidence Challenging the Conjecture

Recent large-scale studies using experimental functional data have challenged the validity of the ortholog conjecture:

Table 1: Key Studies Testing the Ortholog Conjecture

| Study | Data Analyzed | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nehrt et al. (2011) [5] | Experimentally derived functions of >8,900 human and mouse genes | Paralogs were often better predictors of function than orthologs; same-species paralogs most functionally similar | Challenges fundamental assumption in function prediction |

| Stamboulian et al. (2020) [6] | Experimental annotations from >40,000 proteins across 80,000 publications | Strong evidence against ortholog conjecture in function prediction context; paralogs provide valuable functional information | Supports using all available homolog data regardless of type |

These findings demonstrate that the relationship between evolutionary history and functional conservation is more complex than traditionally assumed. Paralogs—particularly those within the same species—can provide equal or superior functional information compared to orthologs [5]. This has significant implications for target validation strategies, suggesting researchers should consider both orthologs and paralogs when predicting gene function.

Ortholog Identification Methods and Databases

Computational Methodologies

Several computational approaches have been developed to identify orthologous relationships:

- Pairwise Reciprocal Best Hits: Identifies pairs of genes in two species that are each other's best match in the other species [7]. This method forms the basis for many ortholog databases but can be misled by complex gene families.

- Phylogenetic Tree-Based Methods: Uses phylogenetic trees to infer orthology by comparing gene trees with species trees [4]. While more accurate, these methods are computationally intensive.

- Synteny-Based Approaches: Leverages conserved gene order and genomic context to identify orthologs [4]. Particularly useful for detecting orthology in complex genomic regions.

- Graph-Based Clustering (OrthoMCL): Applies Markov Cluster algorithm to similarity graphs to group orthologs and recent paralogs across multiple taxa [7]. Effective for handling eukaryotic genomes with multiple paralogs.

The OrthoMCL workflow exemplifies a robust approach for eukaryotic ortholog identification:

Figure 2: OrthoMCL workflow for identifying ortholog groups across multiple eukaryotic species [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Ortholog Databases

| Database | Methodology | Coverage | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) [4] | Reciprocal best hits across multiple species | Originally prokaryotic-focused, now includes some eukaryotes | Well-established, manually curated | Limited eukaryotic coverage |

| OrthoMCL [7] | Graph-based clustering using MCL algorithm | Multiple eukaryotic species | Handles "recent" paralogs effectively | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Ensembl Compara [4] | Synteny-enhanced reciprocal best hits | Wide range of vertebrate species | Incorporates genomic context | Complex to navigate |

| InParanoid [8] | Pairwise ortholog clustering with inparalog inclusion | Focused on pairwise species comparisons | Accurate for two-species comparisons | Limited to pairwise comparisons |

| Gene-Oriented Ortholog Database (GOOD) [8] | Genomic location-based clustering of isoforms | Mammalian species | Handles alternative splicing effectively | Limited species coverage |

Specialized Tools for Particular Applications

Recent developments have produced specialized ortholog identification tools tailored to specific research communities:

- AlgaeOrtho: A user-friendly tool built upon SonicParanoid and PhycoCosm database specifically designed for identifying orthologs across diverse algal species [9]. This tool generates ortholog tables, similarity heatmaps, and phylogenetic trees to facilitate target identification for bioengineering applications.

- SonicParanoid: A fast, accurate command-line tool for identifying orthologs across multiple species, particularly useful for large-scale comparative genomics studies [9].

Experimental Protocols for Ortholog Identification and Validation

Protocol: Reference Gene Identification for Cross-Species Expression Studies

Objective: Identify reliable reference genes for cross-species transcriptional profiling, as demonstrated in studies of Anopheles Hyrcanus Group mosquitoes [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological Material*: Samples from multiple related species at various developmental stages

- RNA Extraction: TRI reagent or equivalent

- cDNA Synthesis: DNase I, SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase or equivalent

- qPCR: SYBR Green master mix, species-specific primers

- Analysis Software: geNorm, BestKeeper, NormFinder, or RefFinder

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect specimens from multiple developmental stages for each species (e.g., larval, pupal, adult stages) [10].

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Extract total RNA using standard methods, treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Candidate Gene Selection: Select potential reference genes based on previous studies and housekeeping gene functions (e.g., ribosomal proteins, actin, GAPDH, elongation factors) [10].

- Primer Design and Validation: Design primers in conserved regions across species, test primer efficiency using standard curves with serial cDNA dilutions.

- qPCR Analysis: Perform quantitative PCR for all candidate genes across all samples and species.

- Stability Analysis: Analyze expression stability using multiple algorithms (geNorm, BestKeeper, NormFinder, RefFinder) [10].

- Validation: Select genes with highest stability rankings for use in cross-species comparisons.

Expected Results: Identification of pan-species reference genes with stable expression across developmental stages and species, enabling valid cross-species transcriptional comparisons.

Protocol: OrthoMCL-Based Ortholog Group Identification

Objective: Identify groups of orthologous genes across multiple eukaryotic genomes using OrthoMCL methodology [7].

Materials and Software:

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster recommended for large datasets

- Input Data: Protein sequences in FASTA format for all species of interest

- Software: BLASTP, OrthoMCL pipeline, Markov Cluster algorithm (MCL)

- Database Resources: Optional integration with GUS (Genomic Unified Schema) for data storage

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Download or compile complete protein sequences for all genomes of interest in FASTA format.

- All-against-all BLAST: Perform BLASTP comparisons of all proteins against all other proteins with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5 [7].

- Ortholog Pair Identification: Identify reciprocal best hits between pairs of species as putative orthologs.

- Paralog Identification: Identify "recent" paralogs as sequences within the same genome that are reciprocally more similar to each other than to any sequence from another species.

- Similarity Graph Construction: Construct a similarity graph where nodes represent proteins and weighted edges represent BLAST similarity scores, normalized to account for systematic biases.

- MCL Clustering: Apply Markov Cluster algorithm with appropriate inflation parameter (typically 1.5-3.0) to identify ortholog groups [7].

- Result Interpretation: Analyze clusters containing sequences from at least two species as final ortholog groups.

Expected Results: Clusters of orthologous proteins and recent paralogs across the analyzed genomes, suitable for functional annotation, evolutionary analysis, and target identification.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ortholog Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ortholog Identification and Validation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Ortholog Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | PhycoCosm (JGI), Ensembl, NCBI RefSeq | Source of protein and nucleotide sequences for ortholog analysis |

| Ortholog Identification Software | OrthoMCL, OrthoFinder, InParanoid, SonicParanoid | Computational detection of orthologous relationships |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | ClustalW, MAFFT, MUSCLE | Align orthologous sequences for phylogenetic analysis |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Packages | IQ-TREE, RAxML, PhyML | Construct phylogenetic trees to validate orthology |

| Gene Expression Analysis | qPCR reagents, RNA extraction kits, reverse transcriptases | Experimental validation of ortholog function through expression studies |

| Functional Annotation Resources | Gene Ontology (GO) database, KEGG pathways | Functional comparison of orthologs and paralogs |

| Synteny Visualization Tools | Genomicus, UCSC Genome Browser, Ensembl Compara | Visualize conserved gene order to support orthology predictions |

Applications in Target Validation and Drug Discovery

The accurate identification of orthologs plays a critical role in target validation across species, particularly in drug discovery research. Key applications include:

- Model Organism Translation: Understanding orthologous relationships enables researchers to translate findings from model organisms (e.g., mice, zebrafish, Drosophila) to human biological processes and disease mechanisms [5].

- Drug Target Conservation: Assessing the conservation of potential drug targets across species helps evaluate the relevance of animal models for specific therapeutic areas.

- Toxicology Prediction: Identifying orthologs of human drug metabolism enzymes in preclinical models improves prediction of compound metabolism and potential toxicity.

- Functional Compensation: Recognizing paralogous relationships helps identify potential functional compensation mechanisms that might affect drug efficacy or cause side effects.

The traditional reliance on the ortholog conjecture for functional prediction is being replaced by more nuanced approaches that incorporate both orthologs and paralogs, particularly same-species paralogs that show strong functional conservation [5]. This expanded view provides a more comprehensive framework for target validation across species.

The distinction between orthologs and paralogs remains fundamental to comparative genomics and cross-species target validation, though the traditional ortholog conjecture requires refinement in light of contemporary evidence. Current research indicates that both orthologs and paralogs provide valuable functional information, with same-species paralogs often being strong predictors of gene function. Researchers engaged in target validation across species should employ robust ortholog identification methods such as OrthoMCL while considering functional information from both orthologs and paralogs. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation, particularly through cross-species expression studies, provides the most reliable approach for translating findings across species boundaries in drug development research.

The Role of Target Product Profiles (TPPs) in Defining Validation Requirements

In translational research, particularly in drug development and comparative genomics, Target Product Profiles (TPPs) serve as critical strategic documents that align development activities with predefined commercial and regulatory goals. A TPP outlines the desired characteristics of a final product—such as a therapeutic, vaccine, or diagnostic—to address an unmet clinical need [11] [12]. When integrated with ortholog identification, a methodology for finding equivalent genes across species, TPPs provide a powerful framework for defining and validating therapeutic targets in non-human model organisms, thereby de-risking and accelerating the development pipeline [13].

This integration is vital for cross-species research, where understanding the function of a gene in a model organism relies on the confirmed equivalence of its ortholog to the human target. This document details the application of TPPs to establish rigorous validation requirements for ortholog-based research, providing structured protocols for researchers and development professionals.

The Strategic Foundation of Target Product Profiles

A Target Product Profile is a strategic planning tool that summarizes the key attributes of an intended product. Originally championed by regulatory authorities, its primary purpose is to guide development by ensuring that every research and development activity is aligned with the goals of the final product, as described in its label [14]. A well-constructed TPP provides a clearly articulated set of goals that help focus and guide development activities to reach the desired commercial outcome [11].

Core Components of a TPP

A comprehensive TPP is structured around the same sections that will appear in the final drug label or product specification sheet [14]. It typically defines both minimum acceptable and ideal or "stretch" targets for each attribute. Failure to meet the "essential" parameters will often mean termination of product development, while meeting the "ideal" profile significantly increases the product's value [11] [14].

Table 1: Core Components of a Target Product Profile for a Therapeutic Candidate

| Drug Label Section | TPP Attribute / Target | Minimum Acceptable | Ideal Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indications & Usage | Therapeutic indication & patient population | Treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe Disease X | First-line treatment for all disease severities in adults & pediatrics |

| Dosage & Administration | Dosing regimen & route | Oral, twice daily, with titration | Oral, once daily, no titration needed |

| Dosage Forms & Strengths | Formulation | Immediate-release tablet | Multiple strengths for flexible dosing |

| Contraindications | Absolute contraindications | Hypersensitivity to active ingredient | None |

| Warnings/Precautions | Major safety risks | Monitoring for hepatotoxicity required | No black-box warning |

| Adverse Reactions | Tolerability profile | Comparable to standard of care | Superior to standard of care |

| Clinical Studies | Efficacy endpoints & outcomes | Non-inferiority on primary endpoint vs. standard of care | Superiority on primary and key secondary endpoints |

| How Supplied/Storage | Shelf life & storage | 24 months at 2-8°C | 36 months at room temperature |

TPPs as a Framework for Defining Validation Requirements

The TPP moves from a strategic document to an operational tool by defining the specific evidence required to confirm that a candidate meets its predefined targets. This is especially critical when relying on model organisms for early-stage validation, where the biological relevance must be firmly established.

Linking TPP Attributes to Ortholog Validation

For a TPP attribute like "Efficacy Endpoints," the underlying requirement is a confirmed biological pathway conserved between humans and the model organism used for preclinical testing. The TPP drives the need to identify and validate the correct ortholog in the research model.

Table 2: Translating TPP Attributes into Ortholog Validation Requirements

| TPP Attribute | Downstream Validation Requirement | Ortholog-Based Research Question |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Efficacy (e.g., >80% point estimate) [15] | Robust, predictive in vivo efficacy model | Does the model organism's ortholog recapitulate the human protein's function in the disease-relevant pathway? |

| Safety Profile (Differentiation from standard of care) [11] | Understanding of conserved off-target biology | Are the binding sites or interactive partners of the target protein conserved in the model organism? |

| Target Population (e.g., pediatrics) [15] | Validation in multiple physiological contexts | Is the ortholog expressed and functional similarly across developmental stages in the model? |

| Onset/Duration of Protection (e.g., within 2 weeks, for 3 years) [15] | Pharmacodynamic biomarker development | Can the ortholog's activity be reliably measured and linked to the functional outcome in the model system? |

Application Note: Integrating TPPs and Ortholog Identification for Target Validation

Experimental Objective

To establish a robust, TPP-informed workflow for identifying and validating orthologs of a human disease gene in a model organism, ensuring the model is fit-for-purpose in evaluating a candidate therapeutic's efficacy and safety.

Experimental Workflow

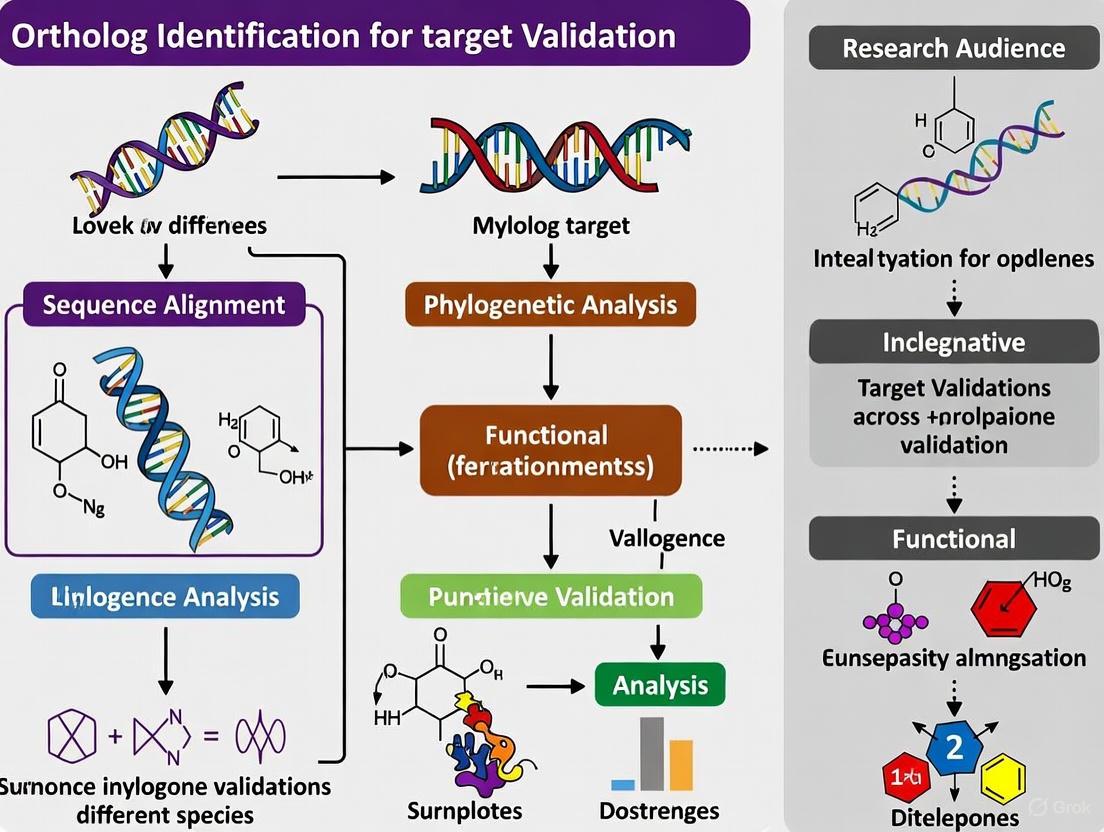

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for using TPPs to guide ortholog identification and validation.

Protocol 1: Defining TPP-Derived Validation Criteria

- Draft the TPP: Assemble a cross-functional team (discovery, clinical, regulatory) to draft a TPP for the candidate therapeutic. The TPP should be structured around future labeling concepts [14].

- Identify Critical Attributes: Pinpoint the TPP attributes that are dependent on the biological function of the target. These typically include efficacy endpoints, safety profile, and target population [11] [15].

- Define Evidence Requirements: For each critical attribute, define the specific biological evidence needed. For example:

- For Efficacy: "Demonstrate that modulating the ortholog in the model organism produces the predicted physiological effect aligned with the human mechanism of action."

- For Safety: "Evaluate the sequence and structural conservation of off-target binding sites in the model organism versus human."

Protocol 2: Ortholog Identification and Confirmation

Objective: To accurately identify the ortholog of the human target gene in the chosen model organism using established bioinformatics tools.

- Sequence Collection: Obtain the protein sequence of the human target gene. Download the complete proteome (all protein sequences) for the model organism(s) of interest from a reliable database such as PhycoCosm, Ensembl, or NCBI [16].

- Ortholog Inference: Use an orthology inference tool to identify putative orthologs.

- Recommended Tools: OrthoFinder (for high accuracy and phylogenetic analysis) [17] or SonicParanoid (for speed and user-friendly downstream processing) [16].

- Input: The human protein sequence and the model organism proteome file(s).

- Command (OrthoFinder example):

orthofinder -f ./proteome_files -t 8, where-tspecifies the number of CPU threads.

- Ortholog Confirmation: The output of these tools (e.g., Orthogroups.tsv from OrthoFinder) will list groups of orthologous genes. Identify the orthogroup containing your human protein and extract the putative ortholog from the model organism.

- Phylogenetic Validation (Optional but Recommended): For critical targets, perform a phylogenetic analysis to confirm the orthology relationship visually and exclude paralogs (genes related by duplication within a species) [17]. Tools like AlgaeOrtho can automatically generate sequence similarity heatmaps and unrooted phylogenetic trees for this purpose [16].

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation of Functional Equivalence

Objective: To experimentally verify that the identified ortholog performs the same biological function as the human target.

- Expression Pattern Analysis:

- Use techniques like RT-qPCR or RNA-Seq to analyze the spatial and temporal expression pattern of the ortholog in the model organism. The expression should be consistent with the expected role in the disease-relevant pathway or tissue.

- Functional Rescue/Complementation Assay:

- In vitro: Transfer the model organism ortholog into a human cell line where the native human gene has been knocked down. Assess if the ortholog can rescue the lost cellular function.

- In vivo: Knock out the ortholog in the model organism and observe the phenotype. Subsequently, introduce the human gene to see if it can rescue the phenotype, providing strong evidence of functional conservation.

- Biochemical Assays:

- Characterize the ortholog's biochemical activity (e.g., kinase activity, receptor binding affinity) and compare it to the human protein. Use assays relevant to the TPP's efficacy mechanism.

- Pharmacological Profiling:

- Test the lead therapeutic candidate (or tool compound) on the model organism ortholog to confirm that the interaction (e.g., binding, inhibition) is conserved. The pharmacodynamic response should mirror what is anticipated in humans.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for TPP-Guided Ortholog Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Orthology Inference Software | Identifies groups of orthologous genes from protein sequences across multiple species. | OrthoFinder [17], SonicParanoid [16], OrthoMCL [13] |

| Proteome Databases | Provides the complete set of protein sequences for a species, required for ortholog searches. | PhycoCosm (algae) [16], Ensembl, NCBI, UniProt |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool | Aligns orthologous sequences to assess conservation and infer phylogeny. | Clustal Omega (used in AlgaeOrtho pipeline) [16], MAFFT |

| Target Enrichment Probe Set | Custom probes to capture orthologous loci for phylogenomics or functional genomics. | Orthoptera-specific OR-TE probe set [18] |

| Model Organism Databases | Curated genomic and functional data for specific model organisms (e.g., yeast, mouse, zebrafish). | SGD, MGI, ZFIN |

The integration of Target Product Profiles with rigorous ortholog identification and validation creates a traceable and defensible bridge from early-stage discovery to clinical application. By using the TPP to define the "what" and "why" of validation, and ortholog research to address the "how," research teams can make informed decisions on model organism selection, derisk preclinical development, and increase the likelihood that their final product will successfully address an unmet clinical need. This structured approach ensures that resources are invested in the most predictive models and assays, ultimately accelerating the translation of basic research into effective therapies.

Linking Target Essentiality to Drug Efficacy in Pathogens and Disease Models

In the field of pharmaceutical innovation, the identification of novel drug targets is a critical and challenging step in the development process. Essential genes, defined as those vital for cell or organism survival, have emerged as highly promising candidates for therapeutic targets in disease treatment [19]. These genes encode critical cellular functions and regulate core biological processes, making them paramount in assessing new drug targets [19]. The systematic identification of essential genes provides a powerful strategy for uncovering potential therapeutic targets, thereby accelerating new drug development across various diseases, including infectious pathogens and cancer [19].

This framework is particularly powerful when applied within a cross-species research paradigm, where ortholog identification enables the validation of targets from model organisms to humans. Understanding the characteristics of essential genes—including their conditional nature, evolutionary conservation, and network properties—provides crucial insights for rational drug design, helping to improve efficacy while anticipating potential side effects [20] [19].

Key Concepts and Definitions

Essential Genes and Their Characteristics

Essential genes are no longer perceived as a binary or static concept. Contemporary research reveals that gene essentiality is often conditional, dependent on specific genetic backgrounds and biochemical environments [19]. These genes typically exhibit high evolutionary conservation across species, indicating their fundamental biological importance, and demonstrate evolvability, where non-essential genes can acquire essential functions through evolutionary processes [19].

From a drug development perspective, essential genes represent particularly valuable targets because their disruption or modulation directly impacts pathogen survival or disease progression. In many pathogens, essential genes account for only 5-10% of the genetic complement but represent targets for the majority of antibiotics [19].

Network Properties Influencing Drug Effects

The position and role of drug targets within biological networks significantly influence therapeutic outcomes and side effect profiles. Key network properties include:

- Essentiality: Drugs targeting essential genes (those encoding critical cellular functions) demonstrate higher efficacy but may also cause more side effects [20] [19].

- Centrality: Targets with high degree (number of direct protein interactions) and betweenness (position in shortest paths) within protein interactome networks are associated with increased side effects [20].

- Interaction Interfaces: Single-interface targets (binding different partners at same interfaces) cause more adverse effects than multi-interface targets when disrupted [20].

Table 1: Network Properties of Drug Targets and Their Implications

| Network Property | Definition | Impact on Drug Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Target Essentiality | Gene required for organism survival [19] | Determines drug efficacy; primary driver of side effects [20] |

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct interaction partners [20] | Higher degree correlates with more side effects [20] |

| Betweenness Centrality | Number of shortest paths going through the target [20] | Higher betweenness correlates with more side effects [20] |

| Interface Sharing | Proportion of partners binding at same interface [20] | Single-interface targets cause more side effects when disrupted [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Essential Gene Identification

CRISPR-Cas9 Functional Genomics Screening

CRISPR-Cas9 screening enables genome-wide identification of essential genes through targeted gene knockouts. The protocol below applies to both pathogen and mammalian systems:

- Library Design: Design and clone guide RNA (gRNA) libraries targeting all protein-coding genes in the target organism.

- Viral Transduction: Transduce cells with lentiviral vectors at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single gRNA integration.

- Selection Pressure: Apply appropriate selection (e.g., antibiotics for integrated vectors) for 48-72 hours.

- Population Sampling: Harvest cell samples at multiple time points (e.g., days 0, 7, 14, 21) to monitor population dynamics.

- gRNA Quantification: Extract genomic DNA and sequence gRNA regions to determine relative abundance.

- Essentiality Scoring: Calculate gene essentiality scores based on gRNA depletion using specialized algorithms (MAGeCK, CERES).

Critical Considerations: Include non-targeting control gRNAs; use sufficient biological replicates (n≥3); optimize infection efficiency for each cell type; confirm Cas9 activity before screening.

Transposon Mutagenesis (Tn-seq) for Bacterial Pathogens

Transposon sequencing identifies essential genes in bacterial pathogens through random insertion mutagenesis:

- Transposon Delivery: Introduce mariner-based transposon into pathogen via conjugation or electroporation.

- Mutant Library Generation: Grow library to high coverage (≥50,000 unique mutants) under permissive conditions.

- Selection Passage: Passage library through relevant conditions (e.g., antibiotic exposure, host infection models).

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest genomic DNA from input and output populations.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA, enrich transposon-chromosome junctions, and prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequence Analysis: Map insertion sites and identify genomic regions with significant insertion depletion.

This method successfully identified pyrC, tpiA, and purH as essential genes and potential antibiotic targets in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [19].

Cross-Species Ortholog Validation Protocol

Validating essential gene conservation across species requires specialized approaches:

- Ortholog Identification: Use reciprocal BLAST with threshold E-value < 1e-10 and alignment coverage > 70%.

- Reference Gene Selection: Identify stable reference genes for normalization in cross-species qPCR (see Table 2).

- Expression Profiling: Measure target gene expression across multiple species and developmental stages.

- Functional Complementation: Test whether orthologs can rescue essential gene function in knockout models.

Table 2: Reference Genes for Cross-Species Expression Studies

| Biological Context | Recommended Reference Genes | Stability Measure | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larval Stage (Mosquito) | RPL8, RPL13a [10] | High stability across 6 species | Cross-species comparison at larval stage |

| Adult Stage (Mosquito) | RPL32, RPS17 [10] | Stable across all adult stages | Cross-species adult comparison |

| Multiple Stages (An. belenrae) | RPS17 [10] | Most stable across stages | Intra-species normalization |

| Multiple Stages (An. kleini) | RPS7, RPL8 [10] | Most stable across stages | Intra-species normalization |

Data Analysis and Visualization Workflows

Network Analysis of Target Essentiality

Network Analysis Workflow for Drug Target Identification

Cross-Species Ortholog Validation Pipeline

Cross-Species Ortholog Validation Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Target Essentiality Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Libraries | Genome-wide gene knockout screening | Identification of essential genes in mammalian and pathogen systems [19] |

| Mariner Transposon Systems | Random insertion mutagenesis | Essential gene identification in bacterial pathogens (Tn-seq) [19] |

| Network Analysis Tools (Gephi) | Network visualization and metric calculation | Analysis of target centrality, degree, and betweenness [20] [21] |

| qPCR Reference Genes (RPS17, RPL8) | Expression normalization in cross-species studies | Stable reference for comparing gene expression across related species [10] |

| Protein Interaction Databases | Source of protein-protein interaction data | Construction of interactome networks for target characterization [20] |

| Ortholog Prediction Tools | Identification of conserved genes across species | Cross-species target validation and essentiality transfer [10] |

Case Studies and Applications

Essential Targets inPseudomonas aeruginosa

A comprehensive transposon mutagenesis study identified three essential genes—pyrC, tpiA, and purH—as promising antibiotic targets in P. aeruginosa [19]. These genes encode functions in pyrimidine biosynthesis (pyrC), glycolysis (tpiA), and purine metabolism (purH). Follow-up validation confirmed that inhibitors targeting these essential pathways exhibited potent bactericidal activity against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates, demonstrating the power of systematic essential gene identification for antibiotic development.

Network Analysis for Side Effect Prediction

A systematic analysis of 4,199 side effects associated with 996 drugs revealed that drugs causing more side effects are characterized by high degree and betweenness of their targets in the human protein interactome network [20]. This finding provides a network-based framework for predicting potential side effects during drug development, emphasizing that both essentiality and centrality of drug targets are key factors contributing to side effects and should be incorporated into rational drug design [20].

Cross-Species Reference Genes in Mosquito Vectors

A recent study identified reliable reference genes for cross-species transcriptional profiling across six Anopheles mosquito species [10]. The research demonstrated that RPL8 and RPL13a showed the most stable expression at larval stages, while RPL32 and RPS17 exhibited stability across adult stages [10]. These reference genes enable accurate comparison of gene expression across closely related pathogen vectors, facilitating research into species-specific differences in vector competence and insecticide susceptibility.

Utilizing Evolutionary Conservation to Infer Gene Function and Disease Relevance

Evolutionary conservation analysis provides a powerful framework for identifying functionally important genes and regions across species. The fundamental premise is that genomic elements under purifying selection due to their critical biological roles will be retained throughout evolution. For researchers in drug discovery and target validation, this approach enables prioritization of candidate genes with higher potential clinical relevance and lower likelihood of redundancy.

Comparative genomics studies have demonstrated that human disease genes are highly conserved in model organisms, with 99.5% of human disease genes having orthologs in rodent genomes [22]. This remarkable conservation enables researchers to utilize model organisms for functional studies, though with important caveats regarding specific disease mechanisms. The distribution of conservation varies significantly across biological systems—genes associated with neurological and developmental disorders typically exhibit slower evolutionary rates, while those involved in immune and hematological systems evolve more rapidly [22]. This variation has direct implications for selecting appropriate model systems for specific disease contexts.

Recent methodological advances now allow researchers to move beyond simple sequence alignment to identify functionally conserved elements, even when sequences have significantly diverged. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying non-coding regulatory elements, which often show rapid sequence turnover while maintaining functional conservation [23].

Quantitative Frameworks for Conservation Analysis

Key Metrics and Their Applications

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation Metrics and Their Applications in Target Validation

| Metric | Calculation Method | Biological Interpretation | Target Validation Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| dN/dS Ratio (KA/KS) | Ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates [22] | Values <1 indicate purifying selection; >1 indicate positive selection | Identify genes under functional constraint across species [22] |

| Taxonomy-Based Measures (VST/STP) | Incorporates taxonomic distance between species with matching variants [24] | Variants shared with distant taxa are more likely deleterious in humans | Improved prediction of pathogenic missense variants [24] |

| Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process | Models expression evolution with parameters for drift (σ) and selection (α) [25] | Quantifies stabilizing selection on gene expression levels | Identify genes with constrained expression patterns across tissues [25] |

| Sequence Conservation Score | Percentage identity from multiple sequence alignments | Estimates degree of sequence constraint | Filter for highly conserved genes as candidate essential genes [26] |

| Indirect Positional Conservation | Synteny-based mapping using IPP algorithm [23] | Identifies functional conservation despite sequence divergence | Discover conserved non-coding regulatory elements [23] |

Performance Comparison of Conservation Metrics

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Conservation Methods for Pathogenic Variants

| Method | Underlying Principle | AUC Value | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIST | Taxonomy-distance exploitation [24] | 0.888 | Superior performance for deleterious variants in non-abundant domains | Requires carefully curated multiple sequence alignments |

| PhyloP | Phylogenetic p-values [24] | 0.820 | Models nucleotide substitution rates | Lower precision across variant types |

| SIFT | Sequence homology-based [24] | 0.818 | Predicts effect on protein function | Limited to coding variants |

| PROVEAN | Alignment-based conservation [24] | 0.816 | Handles indels and single residues | Performance drops with shallow alignments |

| SiPhy | Phylogeny-based conservation [24] | 0.810 | Models context-dependent evolution | Computationally intensive |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identification of Evolutionarily Constrained Genes for Target Prioritization

Purpose: To systematically identify and prioritize evolutionarily constrained genes as high-value targets for therapeutic development.

Materials:

- Genomic sequences from multiple vertebrate species

- Computing infrastructure for large-scale comparative analyses

- Quality-controlled variant datasets (e.g., gnomAD, ClinVar)

Procedure:

Ortholog Identification

- Identify 1:1 orthologs across target species using reciprocal best BLAST hits or specialized tools like Ensembl Compara

- Filter for genes with orthologs across minimum 10 species spanning appropriate evolutionary distances

Evolutionary Rate Calculation

- Perform multiple sequence alignment for each ortholog group using MAFFT or Clustal Omega

- Calculate dN/dS ratios using codeml from PAML package or similar tools

- Classify genes as evolutionarily constrained (dN/dS < 0.5)

Conservation Metric Integration

Functional Validation Prioritization

- Prioritize genes with strong conservation signals (composite score > 0.8) and disease association

- Exclude genes with known redundancy through paralog analysis

- Select top candidates for experimental validation in model systems

Troubleshooting:

- For genes with limited phylogenetic coverage, consider using the IPP algorithm to infer positional conservation [23]

- Address alignment uncertainties by using multiple alignment methods and comparing results

- For rapidly evolving gene families, focus on conserved domains rather than full-length proteins

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Conserved Non-Coding Elements

Purpose: To functionally validate conserved non-coding regulatory elements identified through comparative genomics.

Materials:

- Embryonic tissue from model organisms (mouse, chicken)

- Chromatin profiling reagents (ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq kits)

- Reporter constructs for enhancer assays

- In vivo electroporation or transgenic system

Procedure:

Identification of Non-Coding Conservation

Functional Testing

- Clone candidate elements into reporter vectors (e.g., luciferase, GFP)

- Test enhancer activity in cell-based systems

- Validate in vivo using model organisms at equivalent developmental stages [23]

Disease Variant Assessment

- Identify human variants within conserved non-coding elements

- Test impact of variants on regulatory activity

- Correlate with disease phenotypes and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs)

Diagram 1: Workflow for Identification of Indirectly Conserved Regulatory Elements

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Evolutionary Conservation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, Clustal Omega, MUSCLE | Generate protein/nucleotide alignments | Calculation of evolutionary rates [22] |

| Evolutionary Rate Analysis | PAML (codeml), HYPHY, GERP++ | Calculate dN/dS and conservation scores | Quantifying selective pressure [22] |

| Variant Pathogenicity Prediction | LIST, SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD | Predict functional impact of variants | Prioritizing disease-associated variants [24] |

| Expression Evolution Analysis | OU model implementation (R/BioConductor) | Model expression level evolution | Identify constrained expression patterns [25] |

| Synteny-Based Mapping | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Identify positionally conserved elements | Discovery of conserved regulatory elements [23] |

| Genomic Data Integration | Ensembl, UCSC Genome Browser | Visualize conservation across species | Contextualize conservation patterns [22] |

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Modeling Expression Evolution

Gene expression levels evolve under distinct selective pressures that can be quantified using Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes [25]. This framework models expression evolution through two key parameters: σ (drift rate) and α (strength of stabilizing selection toward an optimal expression level θ). The application of OU models to RNA-seq data across 17 mammalian species revealed that most genes evolve under stabilizing selection, with expression differences between species saturating at larger evolutionary distances [25].

Diagram 2: Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Model of Expression Evolution

Taxonomic Distance Integration

Traditional conservation measures treat all species equally, but newer approaches exploit taxonomic distances to improve predictive power. The LIST method incorporates two taxonomy-aware measures: Variant Shared Taxa (VST), which quantifies the taxonomic distance to species sharing a variant of interest, and Shared Taxa Profile (STP), which captures position-specific variability across the taxonomy tree [24]. These measures significantly improve identification of deleterious variants, particularly in protein regions like intrinsically disordered domains that are poorly captured by conventional methods.

Applications in Disease Gene Discovery

Evolutionary conservation analyses have revealed systematic differences between disease gene categories. Genes associated with neurological disorders show significantly slower evolutionary rates compared to immune system genes [22]. This pattern makes neurological disease genes particularly amenable to study in model organisms, though important exceptions exist, such as trinucleotide repeat expansion disorders where rodent orthologs contain substantially fewer repeats [22].

For infectious disease applications, conservation analysis in bacterial pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa has identified essential genes as promising antibiotic targets [26]. These studies demonstrate that essential and highly expressed genes in bacteria evolve at lower rates, enabling target prioritization based on evolutionary conservation [26].

Regulatory element conservation presents special challenges, as sequence conservation dramatically decreases with evolutionary distance—only ~10% of enhancers show sequence conservation between mouse and chicken [23]. However, synteny-based approaches like IPP can identify 5-fold more conserved enhancers through positional conservation, enabling functional studies of non-coding regions relevant to disease [23].

From Sequence to Function: Methods and Tools for Ortholog Identification

Orthology, describing genes that originated from a common ancestor through speciation events, is a cornerstone of comparative genomics and functional genetics [27] [28]. Accurate ortholog identification is particularly critical for target validation in cross-species research, where understanding gene function and essentiality in a model organism can inform drug target prioritization in a pathogen or human [29]. The two predominant computational approaches for inferring these relationships are graph-based and tree-based methods, each with distinct theoretical foundations and practical implications for researchers. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental protocols and quantitative benchmarks, to guide their application in target validation pipelines.

Orthology Fundamentals and Their Application to Target Validation

Defining Orthology and Paralogy

According to Fitch's classical definition, orthologs are homologous genes diverged by a speciation event, while paralogs are diverged by a gene duplication event [28] [30]. This distinction is biologically significant as orthologs often, though not always, retain equivalent biological functions across species—a concept known as the "ortholog conjecture" [31] [28]. This functional conservation makes ortholog identification indispensable for transferring functional annotations from well-characterized model organisms to less-studied species, a common requirement in biomedical and agricultural research.

The Critical Role of Orthology in Target Validation

In pharmaceutical and parasitology research, orthology inference enables the prediction of essential genes in non-model pathogens by leveraging functional data from model organisms. Studies have demonstrated that evolutionary conservation and the presence of essential orthologues in diverse eukaryotes are strong predictors of gene essentiality [29]. Furthermore, genes absent from the host genome but present and essential in the pathogen represent promising candidates for selective drug targets with minimized host toxicity [29]. Quantitative analyses show that combining orthology with essentiality data can yield up to a five-fold enrichment in essential gene identification compared to random selection [29].

Table 1: Key Orthology Concepts in Target Validation

| Concept | Description | Application to Target Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Orthologs | Genes diverged via speciation [28] | Primary candidates for functional annotation transfer |

| Paralogs | Genes diverged via gene duplication [28] | May indicate functional divergence; potential for redundancy |

| Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) | Nested sets of orthologs defined at different taxonomic levels [30] | Enables precise identification of duplication events and functional conservation depth |

| Essentiality Prediction | Leveraging essential orthologs across species to predict gene indispensability [29] | Prioritizes high-value targets likely required for pathogen survival |

Orthology Inference Methodologies

Graph-Based Methods

Graph-based approaches infer orthology directly from pairwise sequence comparisons, bypassing the need for explicit gene and species trees [27]. These methods typically construct an orthology graph where vertices represent genes and edges connect pairs estimated to be orthologs [27]. Popular implementations include OrthoMCL, ProteinOrtho, and OMA [27] [32].

A key theoretical insight is that under a tree-like evolutionary model, true orthology graphs must be cographs—graphs that can be generated through a series of join and disjoint union operations and do not contain induced paths of four vertices (P~4~) [27]. This structural property enables error correction in inferred graphs by editing them to the closest cograph [27]. For complex evolutionary scenarios involving hybridization or horizontal gene transfer, level-1 networks (networks with relatively few hybrid vertices per "block") provide a more flexible explanatory framework, with characterizations showing that level-1 explainable orthology graphs are precisely those in which every primitive subgraph is a near-cograph (a graph where removing a single vertex results in a cograph) [27].

Graph 1: Graph-based orthology inference workflow. The process begins with sequence comparison and progresses through graph construction and clustering to final orthologous groups, with potential error correction if the graph violates the cograph property.

Tree-Based Methods

Tree-based methods require gene trees and species trees as input and infer orthology through reconciliation—mapping the gene tree onto the species tree to determine whether each divergence event represents a speciation (orthology) or duplication (paralogy) [27] [30]. This approach, implemented in tools like OrthoFinder and EnsemblCompara, uses event-based maximum parsimony, assigning costs to evolutionary events (duplication, speciation, transfer) to find the most plausible reconciliation [27] [30].

The Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) framework represents a powerful extension of tree-based methods, organizing genes into nested sets defined at different taxonomic levels [30]. HOGs can be conceptualized as clades within a reconciled gene tree, with each HOG corresponding to genes descended from a single ancestral gene at a specific taxonomic level [30]. This hierarchical organization enables researchers to pinpoint exactly when in evolutionary history duplications occurred, providing critical context for understanding functional conservation and divergence.

Graph 2: Tree-based orthology inference workflow. This approach requires both gene trees and a species tree, with reconciliation identifying speciation and duplication events to define hierarchical orthologous groups.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 2: Methodological Comparison: Graph-Based vs. Tree-Based Approaches

| Characteristic | Graph-Based Methods | Tree-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Orthology graphs and cograph theory [27] | Gene tree-species tree reconciliation [27] [30] |

| Primary Input | Pairwise sequence similarities [27] | Gene trees and species tree [27] |

| Computational Efficiency | Generally more efficient; suitable for large datasets [27] | Computationally challenging; can be impractical for genome-wide data [27] |

| Handling Complex Evolution | Can be extended to networks (e.g., level-1 networks) [27] | Requires complex reconciliation models for transfers/hybridization |

| Output Resolution | Flat or moderately hierarchical orthologous groups | Explicit hierarchical orthologous groups (HOGs) [30] |

| Key Strengths | Speed, scalability, robustness to incomplete data | Detailed evolutionary history, precise duplication timing |

| Common Tools | OrthoMCL, ProteinOrtho, OMA [27] [32] | OrthoFinder, EnsemblCompara, PANTHER [27] [30] |

Recent benchmarking using the Orthobench resource, which contains 70 expert-curated reference orthogroups (RefOGs), revealed that methodological improvements have significantly enhanced orthology inference accuracy. A phylogenetic reassessment of Orthobench RefOGs revised 44% (31/70) of the groups, with 24 requiring major revision affecting phylogenetic extent [33]. This highlights the importance of using updated benchmarks when evaluating method performance.

Table 3: Orthology Benchmark Performance of Selected Methods

| Method | Approach | Precision (SwissTree) | Recall (SwissTree) | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastOMA | Graph-based with hierarchical resolution [32] | 0.955 [32] | 0.69 [32] | Linear scaling; processes 2,086 genomes in 24h [32] |

| OMA | Graph-based with hierarchical resolution [32] | High (comparable) [32] | Moderate [32] | Quadratic scaling; processes 50 genomes in 24h [32] |

| OrthoFinder | Tree-based [33] | Benchmarked [33] | Benchmarked [33] | Quadratic scaling [32] |

| Panther | Tree-based [32] | High [32] | High recall [32] | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Graph-Based Orthology Inference with FastOMA

FastOMA represents a modern, scalable graph-based method that maintains high accuracy while achieving linear scalability in the number of input genomes [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Input Proteomes: FASTA files of protein sequences for all species of interest

- OMAmer: Alignment-free k-mer-based tool for sequence placement [32]

- Linclust: Highly scalable clustering tool from MMseqs package [32]

- Species Tree: NCBI taxonomy or user-provided reference phylogeny [32]

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Gene Family Inference (RootHOGs):

- Map input proteins to reference Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) using OMAmer

- Group proteins mapped to the same reference HOG into query rootHOGs

- For sequences without recognizable homologs in the reference database, perform additional clustering using Linclust to form new rootHOGs

Orthology Inference:

- For each query rootHOG, infer the nested structure of HOGs through a bottom-up traversal of the species tree

- At each taxonomic level, combine HOGs from child levels based on evolutionary relationships

- Resolve the full hierarchical structure of orthologous groups across all taxonomic levels

Output Generation:

- Generate HOGs at all taxonomic levels for downstream analysis

- Export orthology relationships in standardized formats

Applications in Target Validation

- Rapid identification of conserved orthologs across multiple pathogen species

- Detection of pathogen-specific genes absent from host genomes by examining rootHOG membership

- Essentiality prediction based on conservation patterns across diverse eukaryotes

Protocol 2: Tree-Based Orthology Inference with Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs)

The HOG framework provides a phylogenetic approach to orthology inference, enabling precise determination of duplication events and their evolutionary timing [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool: MAFFT L-INS-i algorithm [33]

- Alignment Trimming: TrimAL [33]

- Phylogenetic Inference: IQ-TREE with model selection [33]

- Species Tree: Known taxonomy or inferred species phylogeny

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Gene Tree Reconstruction:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT L-INS-i algorithm

- Trim alignment with TrimAL to remove poorly aligned regions

- Infer gene tree using IQ-TREE with best-fitting model of sequence evolution

- Assess statistical support using appropriate methods (e.g., bootstrapping)

Tree Reconciliation:

- Reconcile gene trees with the species tree using maximum parsimony or probabilistic methods

- Label internal nodes as speciation or duplication events

- Map gene duplication and loss events onto the species tree

HOG Extraction:

- Define HOGs at each taxonomic level corresponding to clades rooted at speciation nodes

- Organize HOGs in a nested hierarchy reflecting the species phylogeny

- Annotate each HOG with its taxonomic level and evolutionary history

Applications in Target Validation

- Precise identification of lineage-specific gene duplications that may indicate functional specialization

- Reconstruction of ancestral gene content to understand gene family evolution in pathogens

- Differentiation between ancient conserved orthologs and recently diverged paralogs for functional annotation

Application to Target Validation: A Case Study in Parasitic Nematodes

The utility of orthology inference for target prediction is exemplified by research on blood-feeding strongylid nematodes like Haemonchus contortus and Ancylostoma caninum [29]. These parasites cause significant agricultural and human health burdens, yet functional genomic tools for directly testing gene essentiality are limited.

Researchers constructed a database integrating essentiality information from four model eukaryotes (C. elegans, D. melanogaster, M. musculus, and S. cerevisiae) with orthology mappings from OrthoMCL [29]. Analysis revealed that evolutionary conservation and the presence of essential orthologues are each strong predictors of essentiality, with absence of paralogues further increasing the probability of essentiality [29].

By applying quantitative orthology and essentiality criteria, researchers achieved a five-fold enrichment in essential gene identification compared to random selection [29]. This approach enabled prioritization of potential drug targets from among the ~20,000 genes in these parasites, demonstrating the power of orthology inference to guide target validation in non-model organisms where direct genetic manipulation is challenging.

Both graph-based and tree-based orthology inference methods offer distinct advantages for target validation research. Graph-based methods provide computational efficiency and scalability for large multi-genome analyses, while tree-based approaches offer detailed evolutionary histories and precise duplication timing. The emerging generation of tools like FastOMA combines the scalability of graph-based methods with the hierarchical resolution of tree-based approaches [32], while frameworks like Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) provide a structured way to represent complex evolutionary relationships [30].

For researchers engaged in cross-species target validation, orthology inference remains an indispensable tool for predicting gene essentiality, identifying pathogen-specific targets, and transferring functional annotations. Method selection should be guided by research goals: graph-based methods for large-scale screening and tree-based approaches for detailed evolutionary analysis of candidate targets. As genomic data continue to expand, ongoing methodological innovations will further enhance our ability to accurately infer orthology relationships and apply these insights to validate therapeutic targets across the tree of life.

In biomedical and pharmaceutical research, the identification of molecular targets across species is a foundational step for understanding disease mechanisms and developing new therapeutics. The principle that orthologous genes—genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation—largely retain their ancestral function provides a powerful framework for extrapolating functional knowledge from model organisms to humans, or for understanding pathogen biology [34] [30]. This approach is particularly critical in target validation, where researchers assess the potential of a biological molecule to be a drug target. Accurate ortholog identification helps establish biologically relevant model systems, predicts potential side effects due to off-target interactions, and informs on the translatability of preclinical findings.

However, evolutionary processes such as gene duplication and loss create complex gene families, making simple pairwise gene comparisons insufficient. Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (HOGs) offer a refined solution by systematically organizing genes across multiple taxonomic levels, providing a structured view of gene evolution and enabling more precise functional inference [30]. This article details four key resources—OrthoDB, OMA, OrthoFinder, and BUSCO—that empower researchers to navigate this complexity, providing protocols for their effective application in target validation workflows.

The field offers several complementary resources for orthology inference, each with distinct strengths in methodology, taxonomic scope, and output. The table below summarizes the key features of OrthoDB, OMA, OrthoFinder, and BUSCO for direct comparison.

Table 1: Key Features of Ortholog Identification Resources

| Resource | Primary Function | Key Methodological Approach | Taxonomic Scope (as of 2024) | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoDB | Integrated resource of pre-computed orthologs with functional annotations | Hierarchical orthology delineation using OrthoLoger software; aggregates functional data [34] [35] | 5,827 Eukaryotes; 17,551 Bacteria; 607 Archaea [34] | Hierarchical Orthologous Groups (OGs), functional descriptors, evolutionary annotations, BUSCO datasets |

| OMA (Orthologous MAtrix) | Database and method for inferring orthologs | Graph-based inference of orthologs and paralogs, focusing on pairs and groups [34] [35] | 713 Eukaryotes; 1,965 Bacteria; 173 Archaea (2024) [34] | Pairwise orthologs, OMA Groups (HOGs), Gene Ontology annotations |

| OrthoFinder | Software for de novo inference of orthologs from user-provided proteomes | Phylogenetic methodology; infers rooted gene trees and orthogroups [30] | N/A (Software for user-defined species sets) | Orthogroups, gene trees, gene duplication events, phylogenetic analysis |

| BUSCO | Tool for assessing genome/assembly completeness using universal orthologs | Mapping user sequences to benchmark sets of universal single-copy orthologs [34] | Wide coverage of Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes via OrthoDB-derived sets [34] | Completeness scores (% of complete, duplicated, fragmented, missing BUSCOs) |

Table 2: Data Content and Access for Orthology Resources

| Resource | Functional Annotations | Evolutionary Annotations | Data Access & APIs |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoDB | Gene Ontology, InterPro domains, KEGG pathways, EC numbers, textual descriptions [34] [35] | Evolutionary rate, phyletic profile (universality/duplicability), sibling groups [34] | Web interface, REST API, SPARQL/RDF, Python/R API, bulk download [34] |

| OMA | Gene Ontology, functional annotations | Inference of orthologs and paralogs, HOGs | OMA Browser, REST API, bulk download [35] |

| OrthoFinder | N/A (can be added post-analysis) | Gene trees, duplication events, species tree inference | Command-line tool, output files (TSV, Newick) |

| BUSCO | N/A | Implied by universal single-copy ortholog presence | Command-line tool, pre-computed sets for major lineages |

OrthoDB: Application Protocol for Target Assessment

OrthoDB is a comprehensive resource that provides pre-computed orthologous groups with integrated functional and evolutionary annotations, making it highly efficient for initial target assessment.

Workflow for Target Characterization

Step-by-Step Protocol

Query the Database

- Navigate to the OrthoDB website (https://www.orthodb.org).

- Use the search bar with a gene identifier (e.g., human gene symbol, UniProt ID) or genome assembly accession.

- Filter your search using the "get gene" or "search orthologs" selectors to refine results [34].

Retrieve and Analyze Orthologous Groups (OGs)

- OrthoDB presents a list of OGs related to your query. Select the appropriate OG at the taxonomic level relevant to your research (e.g., Vertebrata for comparison across vertebrates, or a narrower clade for more precise functional inference) [34] [30].

- In the OG detail view, examine the Sankey diagram to navigate the hierarchical relationship of OGs across taxonomic levels [34].

- Download protein or newly added coding DNA sequences (CDS) for the entire OG using the "View fasta" links for subsequent analysis [34].

Leverage Functional and Evolutionary Annotations for Target Assessment

- Functional Descriptors: Review the aggregated functional summary, which consolidates data from UniProt, Gene Ontology (GO), InterPro domains, KEGG pathways, and enzyme codes. This provides a concise overview of molecular function and biological role [34] [35].

- Evolutionary Traits: Critically evaluate the evolutionary descriptors unique to OrthoDB:

- Phyletic Profile: Assess the "universality" (proportion of species with orthologs) and "duplicability" (proportion of multi-copy orthologs). A universal gene may indicate a core biological function, while lineage-restriction might suggest species-specific adaptations. High duplicability could signal gene family expansions relevant to functional redundancy or specialization [34].

- Evolutionary Rate: The relative degree of sequence conservation can indicate selective pressure; rapidly evolving genes might be involved in host-pathogen interactions or other adaptive processes [34].

Access Data Programmatically (For Advanced Users)

- For large-scale analyses, use the REST API or the new Python and R Bioconductor API packages to programmatically access OrthoDB data and integrate it into custom analysis pipelines [34].

OrthoFinder: Protocol for De Novo Orthology Inference

OrthoFinder is the tool of choice when working with novel genomes or a specific set of proteomes not fully covered by pre-computed databases.

Workflow for Phylogenomic Analysis

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Preparation

- Gather proteome files (in FASTA format) for all species of interest. Ensure consistent sequence annotation is helpful for downstream interpretation.

- Place all proteome files in a single directory.

Running OrthoFinder

- Install OrthoFinder (e.g., via Conda:

conda install -c bioconda orthofinder). - Run a basic analysis:

orthofinder -f /path/to/proteome_directory -t <number_of_threads>. - For large datasets, consider using the

-M msaoption for more accurate gene tree inference, though this increases computational time.

- Install OrthoFinder (e.g., via Conda:

Analysis of Results for Target Validation

- Orthogroups: The primary output is "Orthogroups.tsv". This file lists all genes belonging to each orthogroup (a HOG at the level of the entire species set). Identify the orthogroup containing your target gene.

- Gene Trees: Examine the rooted gene trees for your orthogroup of interest (located in the "ResolvedGeneTrees" folder). This allows visual confirmation of orthology/paralogy relationships and helps identify potential species-specific duplications that might complicate experimental validation [30].

- Gene Duplication Events: The "GeneDuplicationEvents" output identifies which nodes in the gene trees represent duplications. This is critical for understanding whether a gene pair are true orthologs or out-paralogs, which is vital for selecting the correct counterpart in a model organism [30].

BUSCO: Protocol for Quality Control in Genomics

BUSCO assessments are a critical first step to ensure the reliability of genomic data used for ortholog identification and downstream target validation.

Workflow for Genome Assessment

Step-by-Step Protocol

Dataset Selection and Tool Execution

- Select the appropriate BUSCO lineage dataset (e.g.,

mammalia_odb10for mammals,eukaryota_odb10for broad eukaryotic analysis) that matches the taxonomy of your sample. - Run BUSCO on your genome assembly or annotated gene set. Example command for a transcriptome:

busco -i transcriptome.fa -l eukaryota_odb10 -m transcriptome -o busco_result

- Select the appropriate BUSCO lineage dataset (e.g.,

Interpretation for Target Validation Context

- Analyze the summary output and

full_table.tsv:- High "Complete" BUSCOs (>90-95% for well-assembled genomes): Indicates high gene space completeness, increasing confidence that an absent ortholog represents a true biological loss rather than an assembly artifact.

- Low "Fragmented" and "Missing" BUSCOs: Minimizes false negatives in ortholog searches.

- Low "Duplicated" BUSCOs: A high duplication rate in a haploid genome might indicate assembly issues, such as haplotypic duplication, which could artificially inflate gene copies and mislead orthology calls [34].

- Analyze the summary output and

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Orthology Research

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Orthology Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoDB | Database | One-stop resource for pre-computed hierarchical orthologs with integrated functional and evolutionary annotations [34]. |

| OrthoFinder | Software | State-of-the-art tool for de novo inference of orthologs, gene trees, and gene duplication events from custom proteome sets [30]. |

| BUSCO | Tool & Dataset | Provides benchmark sets of universal single-copy orthologs and a tool to assess the completeness of genomic data [34]. |

| OrthoLoger | Software | The underlying method used by OrthoDB for orthology delineation; also available as a standalone tool or Conda package for mapping new genomes to OrthoDB groups [34] [35]. |

| AlgaeOrtho | Tool / Workflow | Example of a domain-specific (algal) pipeline built upon SonicParanoid for identifying and visualizing orthologs, demonstrating a tailored application [16]. |

| LEMOrtho | Benchmarking Framework | A Live Evaluation of Methods for Orthologs delineation, useful for comparing and selecting the best orthology inference method for a specific project [35]. |

OrthoDB, OMA, OrthoFinder, and BUSCO form a powerful ecosystem of resources for accurate ortholog identification. OrthoDB offers a comprehensive starting point with its rich annotations, while OrthoFinder provides flexibility for custom datasets. BUSCO acts as an essential gatekeeper for data quality. By applying the protocols outlined herein, researchers can robustly leverage evolutionary relationships to validate therapeutic targets across species, thereby strengthening the foundation of translational biomedical research.

The escalating challenge of anthelmintic resistance in parasitic nematodes poses a significant threat to global health and food security, creating an urgent need for novel therapeutic targets [36] [37]. Traditional approaches to anthelmintic discovery have been protracted, expensive, and technically demanding, often relying on whole-organism phenotypic screening without prior knowledge of molecular targets [38] [39]. The integration of orthology identification with machine learning (ML) prediction frameworks now enables systematic prioritization of essential genes in parasitic nematodes, dramatically accelerating the early discovery pipeline [38] [40]. This workflow establishes a robust protocol for cross-species target prediction by leveraging the extensive functional genomic data available for model organisms like Caenorhabditis elegans and translating these insights to medically and agriculturally important parasites through orthology relationships [36] [38].

Table 1: Key Definitions in Orthology-Based Target Discovery

| Term | Definition | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Orthologs | Genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation [28] | Central bridge for functional annotation transfer |

| Essential Genes | Genes critical for organism survival, whose inhibition causes lethality or significant fitness loss [38] | Primary candidates for anthelmintic targeting |

| Chokepoint Reactions | Metabolic reactions that consume a unique substrate or produce a unique product [41] | Prioritization filter for metabolic targets |

| Target Deconvolution | Process of identifying the molecular target of a bioactive compound [36] | Experimental validation of predicted targets |

Orthology-Based Machine Learning Prediction Pipeline

Feature Selection and Model Training

The foundation of accurate essential gene prediction lies in curating informative features with proven predictive power across species. Based on successful applications in Dirofilaria immitis, Brugia malayi, and Onchocerca volvulus, 26 features have been identified as strong predictors of gene essentiality [38] [40]. The most informative predictors include OrthoFinder_species (identifying ortholog groups across species), exon count, and subcellular localization predictors (nucleus and cytoplasm) [38]. These features are derived from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data sources, enabling multi-faceted assessment of gene criticality.

For model training, multiple machine learning algorithms should be evaluated, including Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), Generalized Linear Models (GLM), Neural Networks (NN), Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) [38]. In comparative studies, GBM and XGB typically achieve the highest performance, with ROC-AUC values exceeding 0.93 for C. elegans and approximately 0.9 for Drosophila melanogaster when trained on 90% of the data [38]. The model training process requires careful cross-validation and performance assessment using both ROC-AUC and Precision-Recall AUC (PR-AUC) metrics to ensure robust predictions.

Cross-Species Prediction Implementation

The practical implementation of cross-species prediction involves a structured workflow that transfers essentiality annotations from well-characterized model organisms to poorly studied parasitic nematodes. This process begins with comprehensive data collection from reference databases, followed by orthology inference, feature engineering, and finally ML-based prediction with priority ranking [38] [40].

Table 2: Machine Learning Performance for Essential Gene Prediction

| Model Algorithm | C. elegans ROC-AUC | D. melanogaster ROC-AUC | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting (GBM) | ~0.93 [38] | ~0.9 [38] | Primary prediction model |

| XGBoost (XGB) | ~0.93 [38] | ~0.9 [38] | High-dimensional data |

| Random Forest (RF) | ~0.91 [38] | ~0.9 [38] | Feature importance analysis |

| Neural Network (NN) | >0.87 [38] | >0.8 [38] | Complex non-linear relationships |

Figure 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Cross-Species Essential Gene Prediction

Experimental Validation and Target Deconvolution

Proteomic Approaches for Target Identification

Following computational prediction, experimental validation is crucial for confirming essential gene function and anthelmintic potential. Stability-based proteomic methods have emerged as powerful tools for direct target identification, requiring no compound modification (label-free) and applicable to both lysed cells and live parasites [36]. Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP) has been successfully applied to parasitic nematodes including Haemonchus contortus, identifying protein targets for anthelmintic candidates like UMW-868, ABX464, and UMW-9729 [36]. In these studies, TPP revealed significant stabilization of specific H. contortus proteins (HCON014287 and HCON011565 for UMW-868; HCON_00074590 for ABX464) upon compound binding, providing direct evidence of drug-target interactions [36].