Optimizing Nucleic Acid Extraction from Chemical-Treated Samples: A Complete Guide for Reliable Biomolecular Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the unique challenges of nucleic acid extraction from chemically treated samples.

Optimizing Nucleic Acid Extraction from Chemical-Treated Samples: A Complete Guide for Reliable Biomolecular Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the unique challenges of nucleic acid extraction from chemically treated samples. It covers the foundational principles of how common chemical treatments affect nucleic acid integrity and yield, explores optimized and novel extraction methodologies, details systematic troubleshooting for common pitfalls like inhibitors and degradation, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing current research and protocols, this resource aims to empower scientists to obtain high-quality, amplifiable DNA and RNA from complex sample matrices, thereby ensuring success in downstream molecular applications such as PCR, sequencing, and diagnostic assays.

Understanding the Challenge: How Chemical Treatments Impact Nucleic Acid Integrity and Yield

Common Chemical Treatments and Their Effects on Nucleic Acids

This guide addresses frequently asked questions for researchers optimizing nucleic acid extraction from chemically treated samples, a critical step in drug development and diagnostic research.

▎FAQs on Chemical Treatments and Nucleic Acid Integrity

How do common anticoagulants in blood samples affect downstream PCR analysis?

Anticoagulants are essential for preserving blood samples but can become significant PCR inhibitors if not properly managed.

- EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid): Acts as a chelating agent by binding magnesium ions (

Mg²⁺), which are essential cofactors for DNA polymerase. This binding effectively halts the polymerase reaction [1]. - Heparin: Inhibits PCR by binding directly to DNA polymerase, preventing the enzyme from interacting with the DNA template [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Dilution: Diluting the DNA extract reduces the concentration of the anticoagulant to a level where it no longer inhibits the polymerase [1].

- Purification: Using silica-based columns or magnetic beads can effectively separate nucleic acids from these inhibitors during extraction [1].

- Enzyme Selection: Employing inhibitor-tolerant DNA polymerases engineered for resistance to such compounds can improve amplification success [1].

What is the impact of humic substances from soil or plant samples on DNA analysis?

Humic substances are a major challenge when extracting nucleic acids from environmental samples like soil or decomposed material.

- Inhibition Mechanism: These large, heterogeneous molecules can interfere with the PCR process through multiple mechanisms, including direct interaction with the DNA polymerase and fluorescence quenching of the fluorophores used in qPCR, dPCR, and MPS analysis [1].

- Differential Effects: Digital PCR (dPCR) has been shown to be less affected than quantitative PCR (qPCR) for quantification in the presence of inhibitors like humic acid. This is because dPCR relies on end-point measurement rather than amplification kinetics, making quantification more robust [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Enhanced Purification: Specific kits designed for environmental samples containing additives that precipitate or bind humic acids are recommended.

- Direct PCR Kits: Using specialized "direct PCR" kits with inhibitor-tolerant polymerases can bypass the need for extensive purification, saving time and avoiding DNA loss, especially from samples with high DNA content [1].

How does the use of EDTA in bone demineralization protocols interfere with later steps?

Bone demineralization is a necessary but delicate step for DNA extraction, and EDTA is the most common agent used.

- Primary Function: EDTA chelates calcium ions to soften and dissolve the mineral matrix of the bone, making intracellular DNA accessible [2].

- Secondary Inhibition: The same chelating property becomes a problem if residual EDTA carries over into the PCR, as it will sequester the required

Mg²⁺[2] [1].

Optimized Protocol:

- Balance Chemical and Mechanical Lysis: Combine EDTA treatment with efficient mechanical homogenization (e.g., using a bead ruptor with ceramic or steel beads) to reduce incubation time and the required EDTA volume [2].

- Thorough Washing: After demineralization, pellet the bone powder and wash multiple times with a suitable buffer (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water) to remove residual EDTA before proceeding with protein digestion and DNA purification.

- Post-Extraction Purification: A final purification step using a spin-column protocol is crucial to eliminate any remaining traces of EDTA.

What are the key strategies to protect RNA from degradation during and after extraction?

RNA is inherently less stable than DNA due to its single-stranded structure and susceptibility to ribonucleases (RNases). The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms of RNA degradation and corresponding stabilization strategies.

Table: RNA Degradation Mechanisms and Stabilization Strategies

| Degradation Mechanism | Description | Stabilization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Water molecules break the RNA backbone, accelerated at elevated temperatures and non-optimal pH [3]. | Store RNA in buffered solutions at slightly acidic pH (e.g., pH 5-6) and frozen (-80°C). Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [3]. |

| Enzymatic Breakdown (RNases) | Ubiquitous RNases rapidly degrade RNA [2]. | Use RNase-free reagents and consumables. Include RNase inhibitors (e.g., RNasin) in reactions. Use denaturing agents during lysis [2]. |

| Oxidation | Reactive oxygen species modify nucleotide bases, leading to strand breaks [2]. | Add antioxidants to storage buffers. Store samples in oxygen-free environments or at -80°C [2]. |

| Deadenylation | The CCR4-NOT complex shortens the 3' poly-A tail, marking the mRNA for decay [4]. | Emerging research uses peptide inhibitors to block the CCR4-NOT complex, stabilizing the poly-A tail and extending mRNA lifespan [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating RNA Stability in Solution

- Objective: To determine the impact of buffering species and pH on the integrity of your RNA sample.

- Materials: Purified RNA, different buffering solutions (e.g., Sodium Acetate, Tris-HCl, Citrate), pH meter.

- Method:

- Aliquot the same amount of RNA into different buffering solutions at various pH levels (e.g., pH 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0).

- Incubate the samples at a controlled temperature (e.g., 4°C and 37°C) for a set period.

- Analyze RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or gel electrophoresis. Metrics like the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) can be used.

- Expected Outcome: RNA integrity is generally better preserved in slightly acidic buffers (e.g., Sodium Acetate at pH 5.2) compared to neutral or basic buffers over time [3].

▎Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Research on Chemically Treated Samples

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases | Amplifies DNA in the presence of common inhibitors like humic acid, heparin, or heme [1]. | Essential for "direct PCR" from complex samples, avoiding purification-related DNA loss. |

| Mechanical Homogenizer (e.g., Bead Ruptor) | Physically breaks down tough tissues (bone, plant) [2]. | Reduces reliance on harsh chemical lysing agents. Optimize speed/bead type to minimize DNA shearing. |

| Silica-Membrane / Magnetic Bead Kits | Purifies nucleic acids by binding them in high-salt buffers; elution in low-salt or water [1]. | Effectively removes many PCR inhibitors (salts, proteins, organics). Critical for post-EDTA cleanup. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Non-competitively binds to RNases, inactivating them [2]. | Crucial for all RNA work. Should be added to cell lysates and storage buffers. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., DTT) | Protects nucleic acids from oxidative damage by scavenging reactive oxygen species [2]. | Useful for long-term storage of nucleic acids, especially for precious or archival samples. |

| CCR4-NOT Inhibitor Peptides | Protects mRNA poly-A tail from deadenylation, thereby increasing its intracellular half-life [4]. | An emerging tool for mRNA-based therapeutics and research to enhance protein expression levels. |

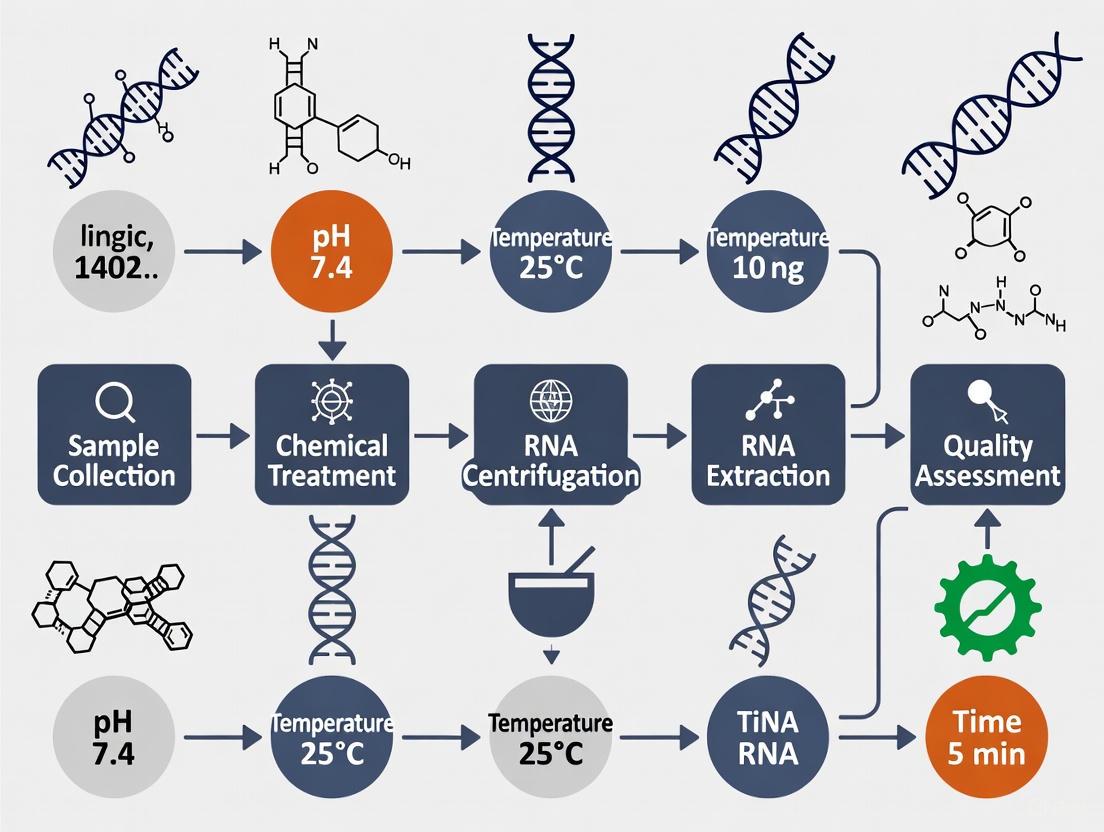

▎Experimental Workflow for Nucleic Acid Optimization

The following diagram summarizes the logical workflow for troubleshooting nucleic acid extraction and analysis from chemically challenging samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of nucleic acid degradation in a laboratory setting, and how can I prevent them? Nucleic acid degradation primarily occurs through four mechanisms: oxidation, hydrolysis, enzymatic breakdown, and physical shearing. Oxidation is triggered by exposure to heat or UV radiation, while hydrolysis occurs when water molecules break the DNA backbone, leading to depurination. Enzymatic breakdown is caused by nucleases present in biological samples, and physical shearing results from overly aggressive mechanical disruption during homogenization. Prevention strategies include adding antioxidants to samples, storing samples at -80°C in dry conditions, using nuclease inhibitors like EDTA during extraction, and optimizing homogenization parameters to balance effective disruption with DNA preservation [2].

2. My downstream applications (e.g., PCR, sequencing) are failing due to inhibitors. Which contaminants are most commonly co-precipitated with nucleic acids, and how are they removed? Common co-precipitating inhibitors include polysaccharides, polyphenols, proteins, and salts. Complex samples like soil and stool contain huge amounts of diverse interfering components that inhibit enzymatic reactions. Effective removal strategies involve using specialized lytic reagents containing phosphates and mild chaotropic agents to solubilize nucleic acids while minimizing degradation. Furthermore, novel combinations of protein-precipitating agents and tri- or tetra-valent salts can precipitate and remove these contaminants. For plant materials high in polysaccharides and polyphenols, modifying lysis buffers with CTAB or adding reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol is effective [5] [6].

3. How can I improve my nucleic acid yield from a difficult, chemically-treated sample? Optimizing the binding conditions during solid-phase extraction is crucial for improving yield. Using a binding buffer at a lower pH (e.g., pH 4.1 instead of 8.6) reduces the negative charge on silica beads, minimizing electrostatic repulsion with negatively charged DNA and significantly enhancing binding efficiency. Furthermore, the mode of bead mixing is critical; a "tip-based" method (repeatedly aspirating and dispensing the binding mix) exposes beads to the sample more rapidly than orbital shaking, reducing the binding time from 5 minutes to 1 minute for the same efficiency and dramatically improving yield, especially for higher input amounts [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Yield and Purity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA/RNA yield | Inefficient cell lysis | - Use a combination of chemical (e.g., CTAB, optimized lytic reagents) and mechanical methods (e.g., bead beating).- Optimize incubation time and temperature for lysis [2] [5] [6]. |

| Suboptimal binding to purification matrix | - Lower the pH of the binding buffer (e.g., to ~4.1) [7].- Use a more efficient mixing method like tip-based mixing instead of orbital shaking [7].- Increase the amount of silica beads for higher input samples [7]. | |

| Nucleic acid degradation | - Ensure samples are flash-frozen and stored at -80°C.- Include nuclease inhibitors (e.g., EDTA, RNase inhibitors) in the lysis buffer [2] [6]. | |

| Low purity (inhibitors present) | Co-precipitation of polysaccharides/polyphenols | - Modify lysis buffer composition (e.g., add CTAB for polysaccharides, PVP or β-mercaptoethanol for polyphenols) [6].- Use purification methods that employ protein-precipitating agents and multivalent salts [5]. |

Degradation and Integrity Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared or absent bands on gel | Physical shearing during homogenization | - Use a homogenizer that allows precise control over speed, cycle duration, and temperature [2].- For sensitive samples, use specialized bead types (e.g., ceramic) and fine-tune processing parameters [2]. |

| Chemical degradation (oxidation/hydrolysis) | - Control temperature during processing to avoid excessive heat buildup [2].- Use buffered solutions to maintain a stable pH and avoid hydrolytic damage [2]. | |

| RNA is degraded | RNase contamination | - Maintain an RNase-free environment and use RNase-inhibiting reagents [6].- Process certain plant tissues, like young leaves, with shorter lysis times to minimize exposure [6]. |

Workflow Optimization Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the optimized workflow for nucleic acid extraction, integrating key steps to overcome degradation and inhibitor challenges.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in optimized nucleic acid extraction protocols, along with their specific functions in addressing core challenges.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | A cationic detergent in lysis buffers that effectively separates polysaccharides and other contaminants from nucleic acids, crucial for plant and other complex samples [6]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | A chelating agent that inactivates metal-dependent DNases and RNases, preventing enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids during extraction [2]. |

| Silica-coated Magnetic Beads | A solid matrix for solid-phase extraction. Binding is significantly enhanced by using a low-pH buffer and efficient "tip-based" mixing, leading to higher yields and faster processing times [7]. |

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine) | Denature proteins and inactivate nucleases and viruses in the sample. They also facilitate the binding of nucleic acids to silica surfaces in solid-phase extraction methods [7]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds to and helps remove polyphenols from plant extracts, preventing their oxidation and subsequent co-precipitation with nucleic acids, which can inhibit downstream applications [6]. |

| β-mercaptoethanol | A reducing agent added to lysis buffers to prevent the oxidation of phenolic compounds in plant samples, thereby improving the purity and yield of the extracted nucleic acids [6]. |

| Optimized Lytic Reagent | A composition containing phosphates and mild chaotropic agents designed to effectively solubilize nucleic acids from complex samples like soil and stool without significant degradation, while also aiding in inhibitor removal [5]. |

The Triple Protection Strategy is a simplified, semi-unified protocol for extracting DNA and RNA from diverse prokaryotic and eukaryotic sources. This approach ensures nucleic acids are safeguarded during the critical lysis step by a specific chemical environment created by Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), and Sodium Chloride (NaCl) [8]. Research indicates that this combined environment is improper for RNase to render DNA free of RNA, and even for DNase to degrade the DNA, thereby preserving the integrity of the target nucleic acids from the moment of cell disruption [8]. This method is recognized for its effectiveness, reduced use of toxic materials, and the high quality of the resulting nucleic acids, making them suitable for sensitive downstream applications like PCR and RT-PCR [8].

Core Functions of the Triple Protection Components

The table below details the specific protective role of each component in the lysis buffer.

Table 1: Core Functions of the Triple Protection Reagents

| Reagent | Primary Function in Lysis | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA (Chelating Agent) | Inhibits metalloenzymes (e.g., DNases, RNases) [8] [2] | Chelates (binds) divalent metal ions (Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺), which are essential cofactors for many nucleases [8]. |

| SDS (Detergent) | Disrupts cellular membranes and denatures proteins [9] | Solubilizes lipid bilayers and binds to proteins, causing them to unfold and inactivating enzymes including nucleases [9]. |

| NaCl (Salt) | Aids in protein precipitation and maintains ionic strength [8] | Neutralizes charges on proteins, facilitating their precipitation and removal during the phase separation step, thereby protecting nucleic acids [8]. |

Troubleshooting Common Lysis Buffer and Extraction Issues

This section addresses specific challenges researchers might encounter when working with the triple protection strategy or nucleic acid extraction in general.

FAQ 1: I suspect my extracted DNA is degraded. What are the common causes related to the lysis step?

DNA degradation can occur through several mechanisms. Inefficient lysis or protection can lead to enzymatic breakdown, while physical methods can cause shearing [2].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Incomplete inhibition of DNases is a primary cause. Ensure your lysis buffer contains fresh and adequate EDTA to chelate all metal ions. Also, verify that SDS is present at the correct concentration to denature nucleases effectively [8] [2].

- Oxidation/Hydrolysis: Exposure to environmental stressors like heat or reactive oxygen species can damage DNA. Store samples and reagents appropriately and consider the use of antioxidants [2].

- Mechanical Shearing: Overly aggressive mechanical homogenization can fragment DNA. For tough samples, balance effective disruption with DNA preservation by optimizing homogenization speed and time, and consider using specialized instruments like a bead-based homogenizer [2].

FAQ 2: My nucleic acid yield is low. How can I optimize the lysis efficiency?

Low yield often points to incomplete cell disruption or inefficient recovery of nucleic acids.

- Incomplete Lysis: The lysis buffer alone may not be sufficient for some robust sample types, like bacterial cells or tissues [9] [10]. For such challenging samples, combine chemical lysis with mechanical methods.

- Bacterial Cultures: Use lysozyme in the lysis buffer followed by freeze-thaw cycles and/or brief sonication [10].

- Tissues/Plant Matter: Use grinding in liquid nitrogen or employ a high-throughput bead homogenizer (e.g., Bead Ruptor Elite, PreOmics BeatBox) to achieve complete homogenization [8] [2] [11].

- Protein Contamination: If proteins are not effectively separated, they can coprecipitate with nucleic acids or interfere with binding. Ensure the neutral saturated salt solution (NaCl) is added correctly and the sample is mixed gently but thoroughly to precipitate proteins during the phase separation step [8].

FAQ 3: How does the protocol differ for RNA extraction to ensure RNase inhibition?

While the triple protection strategy creates a suboptimal environment for RNases, RNA requires even more stringent handling.

- DNase Treatment: After RNA is isolated and precipitated, any contaminating DNA is degraded by adding an RNase-free DNase [8].

- Critical Reagents: Use DEPC-treated water to dissolve the purified RNA pellet, which inactivates any RNases that may be present in the water [8].

- Lysis Buffer Variation: The protocol uses an acidic saturated salt solution during the phase separation step for RNA, which helps to partition RNA into the aqueous phase while leaving DNA and proteins in the interphase/organic phase [8].

Advanced Optimization and Alternative Protocols

For particularly challenging samples (e.g., bone, formalin-fixed tissues, or soil), the basic protocol may require optimization.

- Challenging Samples: Hard, mineralized tissues like bone require a combinatorial approach. This involves chemical demineralization with EDTA alongside powerful mechanical homogenization to physically break through the matrix. It is critical to balance EDTA concentration, as it is a known PCR inhibitor at high levels [2].

- Alternative Solid-Phase Methods: Magnetic nanoparticle (MNP)-based isolation is a modern, efficient alternative to traditional organic extraction. Methods using nanoparticles like NiFe₂O₄ or amine-functionalized variants offer a cost-effective, automatable, and toxic-reagent-free path to high-quality DNA [12]. These methods are particularly suited for high-throughput applications and can be optimized with specific binding and elution buffers (e.g., Tris-HCl, Phosphate Buffer) [12].

Table 2: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Isolation Technologies

| Method | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Suitable Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triple Protection (Organic/Salt-Precipitation) | Chemical cell lysis followed by salt-induced protein precipitation and alcohol precipitation of nucleic acids [8]. | Effective for diverse sample types; semi-unified for DNA/RNA; cost-effective [8]. | PCR, RT-PCR, cloning [8]. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based | Nucleic acids bind to surface-coated paramagnetic beads in high-salt buffer and are released in low-salt or water [12] [13]. | Amenable to automation; high purity; no centrifugation; no toxic reagents [12] [13]. | NGS, PCR, qPCR, sequencing [12] [13]. |

| Silica Column-Based | Nucleic acids bind to a silica membrane in high-salt buffer and are eluted in low-salt buffer or water [13]. | Well-established; consistent results; good for multiple sample types. | NGS, PCR, qPCR, cloning [13]. |

| Rapid Extraction Buffers | Simple lysis and inactivation of nucleases using specialized buffer solutions [13]. | Extremely fast (minutes); simple protocol; high-throughput [13]. | End-point PCR, genotyping [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Hepatic DNA Extraction from Mouse

This is a detailed methodology for extracting DNA from mouse liver, as outlined in the primary source [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer: 1X STE (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM EDTA; pH 8.0)

- 10% SDS solution

- Proteinase K

- Neutral saturated salt solution (NaCl)

- 100% and 70% Ethanol

- RNase A

- Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer or DD water

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Take 1g of liver tissue, cut it into pieces, and grind it using a mortar and pestle in 3 ml of lysis buffer containing 900 µl of 10% SDS. Transfer the emulsion to a micro-centrifuge tube. Add 100 µg of Proteinase K per ml of emulsion and incubate for 1 hour at 50°C [8].

- Phase Separation: Add 350 µl of neutral saturated salt solution (NaCl) per ml of emulsion. Cap the tube and shake gently by hand for 15 seconds. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 590 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature. The DNA will be in the clear aqueous phase (upper layer) [8].

- DNA Precipitation: Transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube. Mix with two volumes of room-temperature absolute ethanol. Invert the tube several times until DNA precipitates (becomes visible as a stringy or cloudy mass) [8].

- DNA Wash: Remove the supernatant. Wash the DNA pellet once with 1 ml of 75% ethanol. Centrifuge at 9500 × g for 5 minutes to reprecipitate the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant [8].

- DNA Dissolving: Air-dry the pellet for 5 minutes. Dissolve the DNA in an appropriate volume of DD water or TE buffer. Quantify the DNA and store at -20°C [8].

- Removal of RNA: To the dissolved DNA, add 50 µg per ml of RNase A and incubate for 1 hour at 37°C to remove any residual RNA contamination [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA | Nuclease inhibition via metal ion chelation [8] [2]. | Critical component of the "triple protection"; concentration must be sufficient to inactivate all cellular nucleases. |

| SDS | Membrane disruption and protein denaturation [8] [9]. | Works synergistically with EDTA and Proteinase K to dismantle cellular structures and inactivate enzymes. |

| NaCl (Saturated Solution) | Protein precipitation and charge neutralization [8]. | The use of neutral vs. acidic saturated salt solution is a key differentiator between DNA and RNA protocols [8]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum protease digestion of cellular proteins [8]. | Essential for degrading nucleases and other proteins; incubation at 50-60°C enhances its activity. |

| RNase A / DNase I | Removal of unwanted nucleic acids [8]. | Added after initial extraction and precipitation to obtain pure DNA or RNA, free of contamination [8]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., NiFe₂O₄) | Solid-phase nucleic acid binding for purification [12]. | Enable rapid, automatable, and toxic-reagent-free isolation of high-quality DNA and RNA for sensitive applications like NGS [12]. |

Visualizing the Triple Protection Workflow and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of the extraction process and the protective mechanism of the lysis buffer components.

Diagram 1: DNA Extraction Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in the triple protection protocol for DNA extraction, from homogenization to the final pure product.

Diagram 2: Triple Protection Mechanism. This diagram shows how the components of the lysis buffer work in concert to neutralize key threats to nucleic acid integrity during cell lysis.

Core Concepts: The Four Fundamental Steps

The purification of nucleic acids is a critical first step in molecular biology. The process can be broken down into four essential stages, each with a specific goal, to ensure the yield and purity required for downstream applications [8].

- 1. Lysis: This initial step involves disrupting the cellular structure to create a lysate and release the nucleic acids into solution. Methods can be physical (e.g., grinding, bead beating), chemical (e.g., detergents, chaotropic salts), or enzymatic (e.g., Proteinase K, lysozyme) [14] [8].

- 2. Dehydration and Protein Denaturation: Cellular proteins are dehydrated and precipitated out of the solution. This is often achieved using high-concentration salt solutions, which cause proteins to fall out of solution, protecting the nucleic acids from nucleases [14] [8].

- 3. Separation: The soluble nucleic acid is separated from the precipitated cellular proteins and other insoluble debris. This is commonly accomplished by centrifugation, filtration, or bead-based methods [14] [8].

- 4. Precipitation: The nucleic acids are forced out of the solution, typically by adding alcohol (e.g., ethanol or isopropanol). The insoluble nucleic acid pellet is then collected via centrifugation, washed, and dissolved in an aqueous buffer like Tris-EDTA or nuclease-free water [14] [8].

This workflow can be visualized as follows:

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Nucleic Acid Purification Issues

This guide addresses common challenges encountered during nucleic acid purification, specifically framed within the context of working with chemically treated samples, which can introduce unique complications.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Purification Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Incomplete lysis due to robust cell walls in chemically treated samples [15] [16]. | Optimize lysis by combining mechanical disruption (bead beating) with enzymatic digestion (Proteinase K) [14] [15]. |

| Column overload or clogging from excessive biomass or indigestible fibers [15]. | Reduce the input material to the recommended amount. For fibrous tissues, centrifuge the lysate to remove debris before binding [15]. | |

| Inefficient binding of nucleic acids to the purification matrix [16]. | Ensure the binding buffer is fresh and at the correct pH. Verify that ethanol was added to the binding buffer as specified [17]. | |

| DNA Degradation | Nuclease activity in DNase-rich tissues (e.g., liver, spleen) exacerbated by chemical treatment [15]. | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. Keep samples on ice during preparation and use nuclease inhibitors [15]. |

| Improper sample storage or overly large tissue pieces [15]. | Cut tissue into the smallest possible pieces and store samples properly with stabilizers like RNAlater [15]. | |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion of proteins, especially in fixed or stabilized samples [15]. | Extend Proteinase K digestion time (30 min to 3 hours) after the tissue appears dissolved. Ensure the lysis buffer is appropriate [15]. |

| Membrane clogged with tissue fibers or protein complexes [15]. | Centrifuge the lysate at maximum speed for 3 minutes to pellet fibers before loading onto the column [15]. | |

| Salt Contamination | Carryover of guanidine salts from the binding or wash buffers [15] [18]. | Perform additional wash steps with 70-80% ethanol. Ensure wash buffer is completely removed before elution [17] [18]. |

| Splashing of the lysate/buffer mixture into the column cap or upper area [15]. | Pipette carefully onto the center of the membrane, avoid transferring foam, and close caps gently [15]. | |

| RNA Contamination in DNA Prep | Co-purification of RNA, leading to inflated DNA quantification [14]. | Add RNase A (e.g., to the elution buffer) during or after the purification process to digest RNA [14] [8]. |

| gDNA Contamination in RNA Prep | Insufficient shearing of genomic DNA during homogenization [18]. | Use a high-velocity bead beater or polytron for homogenization. Include a DNase digestion step, either on-column or in-solution [18]. |

The logical flow for diagnosing and resolving these common issues is summarized below:

Special Considerations for Chemically-Treated and FFPE Samples

Research involving formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) or other chemically treated samples presents specific challenges. The fixation process creates crosslinks between proteins, nucleic acids, and other biomolecules, which must be reversed for successful extraction [19].

- Optimized Lysis: Standard lysis is insufficient. A robust proteolytic digestion using Proteinase K under defined temperatures is crucial to break crosslinks and free nucleic acids [19].

- Severe Conditions for DNA: Due to its higher stability, DNA isolation from FFPE samples often requires more severe conditions, such as longer incubation times and higher temperatures, which can serendipitously help remove more crosslinks [19].

- Handling Fragmented Nucleic Acids: Both RNA and DNA from FFPE samples will be fragmented. Downstream assays must be designed accordingly, typically targeting shorter amplicons (e.g., 60-70 bp) for successful amplification [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Two Common FFPE Nucleic Acid Extraction Methodologies

| Feature | RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit | MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit |

|---|---|---|

| Deparaffinization | Required (uses xylene or substitute and ethanol) [19]. | Not required; direct incubation in proteolytic solution [19]. |

| Digestion Format | Performed in a tube with buffer and protease [19]. | Performed in a 96-well plate with buffer, protease, and a wax-penetrating additive [19]. |

| Isolation Method | Filter-based spin column (glass-fiber filter) [19]. | Bead-based (magnetic beads) [19]. |

| Throughput | Lower (e.g., 40 reactions per kit) [19]. | Higher, amenable to automation (e.g., 96 reactions per kit) [19]. |

| Best For | Lower throughput, manual processing [19]. | High-throughput labs, automated platforms like KingFisher [19]. |

Optimization and Advanced Techniques

Magnetic Bead-Based Extraction

Magnetic beads-based nucleic acid extraction is widely used in automated systems and can be optimized for efficiency.

- Speed Variation: Using a single, slow mixing speed can result in lower RNA extraction efficiency. Implementing varied speeds (slow, moderate, fast) during the mixing process significantly increases positivity rates and lowers Ct values in downstream RT-PCR, as it enhances the capture and mixing processes [20].

- Heating Step: For some magnetic beads-based kits, skipping the heating step during lysis and elution does not significantly reduce extraction quality, simplifying the protocol [20].

Heat-Based Extraction

The heat-shock method is a simple and effective alternative, especially in resource-limited settings.

- Methodology: Heating samples at 90-95°C for 5 minutes disrupts cells to release nucleic acids [20].

- Separation without Centrifugation: While centrifugation gives the best results, cell debris can also be separated by allowing samples to cool or simply settling at room temperature, making this a feasible method in laboratories without centrifugation facilities [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My nucleic acid yields are consistently low, but my samples are fresh. What is the most likely cause? The most common cause of low yields is incomplete lysis or homogenization [16] [18]. Ensure your lysis method is appropriate for your sample type. For tough tissues, use a combination of physical disruption (e.g., grinding in liquid nitrogen) and enzymatic digestion. Also, verify that the binding conditions are correct, including the freshness and concentration of the ethanol used [17].

Q2: How can I tell if my DNA sample is contaminated with salt, and how do I fix it? Salt contamination is indicated by a low A260/A230 ratio (<2.0) in spectrophotometric measurements [15] [18]. To resolve this, ensure wash buffers are prepared correctly and perform an additional wash step with 70-80% ethanol. Be careful during pipetting to avoid splashing buffer into the column cap, as this is a common source of salt carryover [15].

Q3: I am working with pancreas tissue, and my DNA is always degraded. What specific steps should I take? Organs like the pancreas, liver, and intestine are rich in nucleases. To prevent degradation:

- Flash-freeze the tissue immediately after collection in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

- During processing, keep the tissue frozen on ice.

- Cut the tissue into the smallest possible pieces before adding it to the lysis buffer.

- Ensure your lysis buffer contains chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine) to inactivate nucleases immediately upon contact [14] [15].

Q4: For downstream applications like long-range PCR, what is the best practice for eluting DNA? For applications requiring high-molecular-weight DNA, elution in a slightly basic buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8-9) is superior to water. DNA is more stable at a basic pH and will dissolve faster and more completely in a buffer. Allow the elution buffer to stand on the silica membrane for a few minutes before centrifugation to maximize recovery [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts(e.g., Guanidine HCl, Guanidine thiocyanate) | Denature proteins and nucleases; disrupt hydrogen bonding in water to facilitate nucleic acid binding to silica [14] [17]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests proteins and aids in lysing tough tissues; works optimally under denaturing conditions [14] [17]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) that are cofactors for nucleases, thereby protecting nucleic acids from degradation [21] [8]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | An ionic detergent that solubilizes cellular membranes and denatures proteins, aiding in cell lysis [14] [8]. |

| RNase A | An enzyme that degrades RNA; used to remove RNA contamination from DNA preparations [14] [8]. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | An enzyme that degrades DNA; used to remove genomic DNA contamination from RNA preparations [8] [18]. |

| Beta-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | A reducing agent that helps inactivate RNases by breaking disulfide bonds, particularly critical for stabilizing RNA during extraction [18]. |

| Silica Matrix / Magnetic Beads | The solid phase that selectively binds nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts and high concentrations of ethanol, allowing for purification from other cellular components [14] [17]. |

Optimized Protocols and Novel Methods for Challenging Sample Types

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the semi-unified nucleic acid extraction protocol, along with their primary functions. [21]

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelates divalent cations (Mg²⁺), which are essential cofactors for DNase and RNase enzymes, protecting nucleic acids from degradation. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | A detergent that disrupts cellular membranes (lysis) and denatures proteins, facilitating the release of nucleic acids. |

| NaCl (Sodium Chloride) | Provides the appropriate ionic strength to shield the negative charges on the phosphate backbone of nucleic acids, preventing aggregation and aiding in stability. |

| RNase A | An enzyme added after DNA extraction to degrade any residual RNA contamination, yielding pure DNA. |

| DNase I | An enzyme used during RNA isolation to degrade DNA contaminants, resulting in high-quality RNA. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., NiFe₂O₄) | A modern, cost-effective solid phase for binding and purifying nucleic acids from complex matrices, reducing the use of toxic reagents. [22] |

| Lysis Buffer | A mixture typically containing EDTA, SDS, and NaCl, creating the "triple protection" environment for nucleic acids during cell disruption. |

| Elution Buffer | A low-salt solution (e.g., Tris-EDTA buffer or nuclease-free water) used to release purified nucleic acids from silica columns or magnetic beads. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

This section addresses specific challenges you might encounter when using semi-unified protocols, especially with chemically-treated samples.

FAQ 1: My nucleic acid yield is consistently low. What could be the cause?

- A: Low yield can stem from several points in the protocol. The table below outlines common causes and recommended solutions. [23]

| Problem Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inadequate Lysis | Solution: Optimize lysis conditions. For tough cell walls (e.g., gram-positive bacteria, plant cells), incorporate mechanical disruption (bead beating) or extended enzymatic digestion (lysozyme, proteinase K) in addition to the standard SDS-based chemical lysis. [21] [23] |

| Carryover of Inhibitors | Solution: Ensure thorough washing steps. If using spin columns, do not reduce wash buffer volumes. For magnetic bead-based protocols, ensure complete resuspension of beads during washes. Adding an extra wash step can be beneficial for complex samples like blood or soil. [23] |

| Inefficient Binding | Solution: Verify the pH and composition of the binding buffer. Ensure the sample is adequately mixed with the buffer. If using magnetic nanoparticles, optimize the incubation time and mixing frequency to maximize contact. [22] [23] |

FAQ 2: My extracted nucleic acids are degraded. How can I prevent this?

- A: Degradation is primarily caused by nucleases. The semi-unified protocol's "triple protection" lysis environment (EDTA, SDS, NaCl) is designed to inhibit these enzymes. [21] For additional protection:

- Work quickly and on ice whenever possible.

- Use nuclease-free tubes and tips.

- For RNA-specific work, use dedicated RNase-free reagents and consider adding a specific RNase inhibitor.

- Store extracts at -80°C (especially for RNA) and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. [23]

FAQ 3: My downstream applications (PCR, RT-PCR) are failing due to contaminated nucleic acids. What should I do?

- A: Contamination can be from co-purified biomolecules or cross-sample contamination.

- DNA contamination in RNA preps (and vice-versa): This is addressed directly in the semi-unified protocol. Always add DNase I during RNA isolation and RNase A after DNA extraction to obtain pure nucleic acids. [21]

- Protein or Salt Carryover: Perform the recommended wash steps thoroughly and ensure the final eluate does not contain ethanol from wash buffers.

- Cross-Contamination: Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips and change gloves frequently. For high-throughput labs, automated nucleic acid extraction systems can significantly reduce this risk. [23]

FAQ 4: How can I adapt this protocol for samples treated with harsh chemicals?

- A: Chemical treatments can cross-link or fragment nucleic acids.

- Extended Lysis: Increase lysis incubation times and consider using higher concentrations of proteinase K to reverse formaldehyde cross-links.

- Additional Purification: If inhibitors from the chemical treatment persist, perform a post-extraction purification using magnetic bead-based clean-up protocols, which are effective for removing a wide range of contaminants. [22]

- Quality Control: Always assess the integrity of extracted nucleic acids from chemically treated samples via gel electrophoresis or a bioanalyzer before proceeding to expensive downstream applications. [23]

Experimental Protocol: Core Methodology

This section provides the detailed, step-by-step methodology for the semi-unified nucleic acid extraction protocol.

Lysis under "Triple Protection"

- Principle: The combined action of EDTA, SDS, and NaCl creates an environment that physically disrupts cells and chemically inactivates nucleases, preserving nucleic acid integrity. [21]

- Procedure:

- Resuspend cell pellet or tissue sample in 500 µL of lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0).

- For prokaryotic cells with robust walls, add 10 µL of lysozyme (10 mg/mL) and incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Add 10 µL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL) and incubate at 55-60°C for 30-60 minutes or until the solution clears. Vortex intermittently.

- Add 200 µL of 5 M NaCl to further precipitate proteins and polysaccharides. Mix thoroughly.

Separation and Purification

- Principle: Nucleic acids are separated from cellular debris, proteins, and other contaminants.

- Procedure (Organic Extraction Method):

- Add an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) to the lysate. Vortex vigorously.

- Centrifuge at >12,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase (containing nucleic acids) to a new tube.

- Add an equal volume of chloroform to remove residual phenol. Vortex and centrifuge as before. Transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube.

- Procedure (Solid-Phase Method - Column or Magnetic Beads):

- Mix the lysate with a binding buffer (e.g., containing guanidinium thiocyanate) that promotes nucleic acid binding to a silica surface.

- Transfer the mixture to a spin column or add functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. [22]

- Centrifuge the column or use a magnet to capture the beads. Discard the flow-through.

Washing

- Principle: Remove salts, solvents, and other impurities while the nucleic acids remain bound.

- Procedure:

- Wash the silica membrane or magnetic beads twice with 700 µL of a wash buffer (typically ethanol-based).

- Centrifuge or use a magnet to ensure all wash buffer is removed. A final "dry" spin is recommended for columns to evaporate residual ethanol.

Elution

- Principle: Release pure nucleic acids from the solid phase into an aqueous buffer.

- Procedure:

- Add 50-100 µL of elution buffer (TE buffer or nuclease-free water) to the center of the silica membrane or to the dried magnetic beads.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2-5 minutes to allow for complete rehydration and elution.

- Centrifuge (for columns) or use a magnet (for beads) to collect the purified nucleic acid eluate.

Post-Extraction Treatment for Purity

- For DNA purification: Add 2 µL of RNase A (10 mg/mL) to the eluted DNA. Incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes. [21]

- For RNA purification: Add 2 µL of DNase I (1 U/µL) to the eluted RNA. Incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes, then inactivate the enzyme (e.g., with EDTA or heat). [21]

Protocol Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points within the semi-unified nucleic acid extraction protocol.

Advanced Method: Magnetic Nanoparticle Workflow

For a modern, cost-effective, and less toxic approach, magnetic nanoparticles can be integrated into the purification step. The following diagram details this advanced workflow. [22]

This guide provides targeted troubleshooting for researchers optimizing nucleic acid extraction from chemically-treated samples. The methods detailed below—mechanical, enzymatic, and chaotropic salt-based lysis—are critical for achieving high yields of pure, intact nucleic acids for sensitive downstream applications in drug development and molecular diagnostics.

Lysis Method Selection Guide

Choosing the appropriate lysis technique is paramount for sample integrity. The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision process for selecting an optimal method based on your sample type and research goals.

Troubleshooting Common Lysis Problems

FAQ: Why is my nucleic acid yield low after mechanical lysis?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete Cell Disruption: Ensure your method matches the cell wall toughness. Bacterial spores and plant tissues require more aggressive techniques like bead beating.

- Nucleic Acid Degradation during Lysis: Mechanical methods can generate heat. Always use cooling intervals during sonication or bead beating, and include nuclease inhibitors in your buffer [24] [25].

- Inefficient Binding to Purification Matrix: After lysis, the released nucleic acids must bind to silica columns or beads. Verify that the correct concentration of chaotropic salts and ethanol is used, as this is critical for efficient binding [17].

FAQ: My protein recovery is low or the protein is inactive after enzymatic lysis. What went wrong?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Enzyme Incompatibility: The lytic enzyme must match the cell wall composition. Use lysozyme for bacterial peptidoglycan, lyticase for fungal glucans, or cellulase for plant cells [24].

- Suboptimal Reaction Conditions: Enzymatic lysis is sensitive to buffer conditions (pH, temperature, osmotic stability). For protoplast formation, the lysis buffer must be isotonic, often achieved by adding sugars like sorbitol or mannitol, to prevent premature rupture [26].

- Co-purifying Nucleic Acids Increasing Viscosity: The released chromosomal DNA can create a viscous lysate that traps proteins, reducing yield. Add a nuclease like Benzonase to the lysis buffer to digest nucleic acids and reduce viscosity [25].

FAQ: How do I choose between urea and guanidinium salts for chaotropic lysis?

Guanidinium salts (e.g., GdmCl, GdmSCN) and urea are potent denaturants but have different strengths. The table below summarizes their distinct properties to guide your selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Chaotropic Salts for Lysis and Denaturation

| Chaotropic Salt | Common Concentrations | Mechanism of Action | Preferred For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium HCl (GdmCl) | 4-6 M [27] | Competes for hydrogen bonds; disrupts hydrophobic interactions; stacks with aromatic groups [27]. | Preferentially denatures and disrupts proteins rich in alpha-helices [27]. | Highly effective for inactivating nucleases during nucleic acid extraction [17]. |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate (GdmSCN) | 2-4 M | Similar to GdmCl, but the thiocyanate anion is highly chaotropic, enhancing potency [28]. | Rapid and complete denaturation of DNA and proteins; a key component in RNA stabilization reagents (e.g., TRIzol) [29]. | The most potent denaturant among guanidinium salts; can fully denature DNA origami structures at 2 M and 50°C [28]. |

| Urea | 6-9 M [27] | Disrupts the hydrogen-bonding network of water, leading to solvation of hydrophobic residues; can also form direct hydrogen bonds [27]. | Preferentially denatures and disrupts proteins rich in beta-sheets [27]. | Can form cyanate ions at high temperatures, which can carbamylate proteins. Use fresh solutions. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A properly formulated lysis buffer is more than just a denaturant. The table below lists key components and their functions for effective and reliable cell lysis.

Table 2: Key Components of a Lysis Buffer and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Example Components | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agents | Tris-HCl, HEPES, Phosphate buffers | Maintain stable pH during lysis, crucial for biomolecule stability [26] [30]. | Avoid amine-based buffers (e.g., Tris) in cross-linking reactions [26]. |

| Chaotropic Salts | Guanidine HCl, Guanidine Thiocyanate, Urea | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, and facilitate nucleic acid binding to silica [17] [27]. | Concentration determines denaturing strength; GdmSCN is most potent [28]. |

| Detergents | SDS (ionic), Triton X-100 (non-ionic), CHAPS (zwitterionic) | Solubilize lipid membranes and proteins [24] [30]. | Ionic detergents (SDS) fully denature; non-ionic are milder and preserve protein function [30]. |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol | Break disulfide bonds in proteins, aiding denaturation and preventing aggregation [26] [30]. | Add fresh before use as they oxidize in solution. |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, EDTA, Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent proteolytic degradation of target proteins [26] [30]. | PMSF targets serine proteases; EDTA inhibits metalloproteases [26]. |

| Nucleases | Benzonase, DNase I, RNase A | Digest unwanted nucleic acids to reduce lysate viscosity and prevent co-purification [25]. | Essential for streamlining protein purification and improving chromatography [25]. |

| Osmotic Stabilizers | Sucrose, Sorbitol, Mannitol | Maintain osmotic balance to protect organelles or create protoplasts during gentle lysis [26]. | Critical for enzymatic lysis of yeast/fungi (1M sorbitol) and plant cells (mannitol) [26]. |

Optimized Protocol: Combined Mechanical and Chaotropic Lysis for Soil DNA

This protocol, adapted from a comparative study, is effective for difficult samples like chemically-treated soils or sediments [31].

Principle: Brief, low-speed bead milling provides physical disruption, while a buffered SDS-chloroform mixture ensures chemical lysis. This combination maximizes DNA yield and minimizes shearing.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Lyophilize 100 mg of soil or sediment and grind to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle [31].

- Bead Mill Homogenization: Transfer the powder to a tube with lysis beads. Add 1-2 mL of pre-cooled Phosphate-Tris Lysis Buffer (pH 8.0) containing:

- 100 mM Sodium Phosphate

- 100 mM Tris-HCl

- 2% (w/v) SDS

- 100 mM NaCl Homogenize at low speed for 30-120 seconds. Monitor temperature to avoid overheating [31].

- Chemical Lysis and Extraction: Add an equal volume of chloroform to the homogenate. Mix thoroughly and centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to separate the phases [31].

- DNA Recovery: Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. The DNA can be purified using a commercial silica column kit or by Sephadex G-200 spin column chromatography to remove PCR-inhibiting humic substances [31].

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) is a foundational sample preparation technique critical for purifying and concentrating analytes from complex matrices. In modern nucleic acid research, particularly for chemically-treated samples, optimizing SPE is essential for obtaining high-quality DNA and RNA for downstream applications like sequencing and PCR. The technique has evolved from traditional silica membranes to advanced magnetic bead-based methods, each with distinct advantages and operational challenges. This technical support center addresses the most common experimental hurdles researchers face, providing targeted troubleshooting and methodological guidance to enhance extraction efficiency, reproducibility, and nucleic acid recovery from challenging sample types.

Troubleshooting Common Solid-Phase Extraction Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Solutions

Q1: What is the most common cause of low analyte recovery in SPE, and how can I fix it? Low recovery often stems from improper sorbent choice, inadequate elution conditions, or the cartridge drying out. Ensure the sorbent chemistry matches your analyte's polarity and charge state. For elution, increase solvent strength or volume; for ionizable analytes, adjust pH to neutralize the charge. Always prevent sorbent beds from drying before sample loading by re-conditioning if necessary [32] [33].

Q2: My flow rate is inconsistent. What should I check? Flow rate variations are frequently caused by particulate clogging, high sample viscosity, or uneven sorbent packing. Always filter or centrifuge samples to remove particulates. For viscous samples, dilute with a weak, matrix-compatible solvent. Using a controlled vacuum manifold or pump can standardize flow rates across samples [32].

Q3: How do I know if I've exceeded my SPE cartridge's capacity? Sorbent overload leads to analyte breakthrough and loss. As a general rule, silica-based sorbents have a capacity of ~5% of their mass, while polymeric sorbents can hold up to ~15%. For example, a 100 mg C18 cartridge can bind approximately 5 mg of analyte. If you suspect overload, reduce the sample load or use a cartridge with higher capacity [32].

Q4: Why is my cleanup insufficient, with many co-extracted impurities? This typically indicates a suboptimal purification strategy or wash solvent strength. For targeted analysis, choose a mode that retains your analyte and selectively washes out impurities. Re-optimize your wash conditions—small changes in organic percentage or pH can significantly improve selectivity. Using a more selective sorbent (e.g., ion-exchange) can also enhance cleanup [32].

Q5: Can I reuse magnetic beads? Reuse is only acceptable when cross-sample contamination is not a concern, such as in repeated purifications of the same sample. For most applications, especially with different biological samples, use fresh beads to prevent carryover contamination and ensure consistent binding capacity [34].

Troubleshooting Guide Table

The following table summarizes common SPE problems, their causes, and recommended solutions for efficient problem-solving.

Table 1: Solid-Phase Extraction Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Primary Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recovery [32] [33] | - Incorrect sorbent choice- Weak elution solvent- Insufficient elution volume- Column dried out | - Match sorbent chemistry to analyte (RP, Ion-Exchange, Normal-Phase)- Increase organic % in eluent or adjust its pH- Increase elution volume; use multiple fractions- Keep sorbent wet; re-condition if dried |

| Poor Reproducibility [32] | - Variable flow rates during loading- Column bed dried out- Wash solvent too strong | - Use a manifold or pump to control flow rate (<5 mL/min)- Ensure proper conditioning/equilibration before loading- Weaken wash solvent strength; avoid prolonged soaking |

| Slow Flow Rate [32] [33] | - Particulate clogging- High sample viscosity- Overly dense sorbent packing | - Filter or centrifuge sample pre-loading; use a prefilter- Dilute sample with weak solvent to reduce viscosity- Apply gentle positive pressure if not clogged |

| Incomplete Cleanup [32] | - Incorrect purification strategy- Poorly chosen wash solvents | - Retain analyte and wash impurities, not vice-versa- Re-optimize wash solvent composition, pH, and ionic strength |

| Magnetic Beads Not Pelleting [35] | - Solution too viscous- Bead aggregation | - Increase separation time on magnet (2-5 mins)- Add Tween 20 (~0.05%) or DNase I to lysate |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Optimized Two-Phase SPE for Urinary Nucleic Acid Adducts

Background: This protocol is designed for the untargeted analysis of the urinary nucleic acid adductome, which requires maximal recovery of a wide spectrum of chemically diverse adducts. Single-phase SPE is often insufficient for this purpose [36].

Methodology:

- SPE Sorbent Combination: The optimized combination uses ENV+ cartridges coupled with Phenyl (PHE) cartridges. This two-phase system provides superior retention for a cocktail of 20 different nucleic acid adduct standards compared to any single sorbent [36].

- Sample Preparation: Urine samples are spiked with a cocktail of isotopically labeled internal standards (e.g., at a final concentration of 1 µg/mL) to monitor recovery and aid in identification [36].

- Conditioning and Loading: Condition the combined sorbents as per manufacturer recommendations. Load the urine sample at a controlled, slow flow rate to ensure optimal binding.

- Washing and Elution: Wash with a solvent that removes matrix interferences without eluting the target adducts. Elute with a solvent of sufficient strength and volume to disrupt analyte-sorbent interactions completely.

- Analysis: The eluate is analyzed using untargeted high-resolution mass spectrometry. Data processing with software like FeatureHunter 1.3 can identify approximately 500 distinct adduct features in mouse and human urine samples, demonstrating the method's effectiveness [36].

Acid-Activated Bentonite (ASAB) for Pathogenic Samples

Background: This innovative SPE method uses modified clay to overcome limitations of traditional silica-based kits, such as suboptimal recovery and chaotropic ion inhibition. It is highly versatile for DNA, RNA, and miRNA from various samples [37].

Methodology:

- Matrix Fabrication:

- Acid Activation: Treat raw bentonite with sulfuric acid. This process increases its surface area by 2.2 times, creating more binding sites [37].

- Amino-Functionalization: Modify the sulfuric acid-activated bentonite (SAB) with 3-aminopropyl(diethoxy)methylsilane (APDMS) to create ASAB [37].

- Cross-linking: Use a homobifunctional imidoester (HI) reagent to create reversible cross-links between the amine groups on ASAB and the nucleic acids, enabling pH-dependent binding and elution [37].

- Extraction Protocol:

- Binding: Mix the sample with the ASAB-HI complex at a pH that facilitates binding. The system can handle large volumes (up to 50 mL) to enrich trace pathogens [37].

- Washing: Wash away contaminants with an appropriate buffer.

- Elution: Elute the purified nucleic acids using an elution buffer at a specific pH that breaks the reversible cross-links [37].

- Performance: This method demonstrated a 3.95-fold increase in DNA recovery from human urine and plasma and a 6.3-fold improvement in unstable viral RNA isolation from clinical swabs compared to a commercial silica-based SPE kit [37].

Magnetic Beads Optimization for Nucleic Acids

Background: Magnetic beads are widely used for high-throughput nucleic acid purification. Their performance depends on proper handling and buffer optimization.

Methodology:

- Bead Handling:

- Resuspension: Always vortex magnetic beads thoroughly before use to redisperse settled particles [34].

- Storage: Store beads at 2-8°C or room temperature per instructions. Do not freeze, as freezing can crack the beads and destroy their magnetic and binding properties [34].

- Pelleting: If beads do not pellet, increase separation time on the magnet to 2-5 minutes. For viscous solutions or aggregates, add Tween 20 (up to 0.1%) or DNase I to the lysate [35].

- Binding Capacity Optimization: The binding capacity is length-dependent. For large fragments (>2 kb), expect reduced capacity due to steric hindrance.

- Elution: For efficient elution, resuspend the bead-nucleic acid complex completely in a low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., water or Tris-HCl) and incubate at 65°C for >5 minutes. Using pre-heated elution buffer can improve yield [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid SPE

| Reagent/Material | Function in SPE Optimization |

|---|---|

| ENV+ & PHE Sorbents [36] | A two-phase SPE combination that provides broad retention for diverse nucleic acid adducts in untargeted adductomics. |

| Acid-Activated Bentonite (ASAB) [37] | A high-surface-area SPE matrix for efficient, versatile extraction of DNA, RNA, and miRNA from various sample types. |

| Homobifunctional Imidoester (HI) [37] | A cross-linker for pH-dependent, reversible binding of nucleic acids to amine-functionalized surfaces like ASAB. |

| Isotopically Labeled Standards [36] | Internal standards used to quantitatively monitor analyte recovery and identify endogenous adducts in mass spectrometry. |

| Magnetic Beads (Streptavidin) [35] | Paramagnetic particles with a streptavidin coating for highly specific capture of biotinylated nucleic acids or other molecules. |

| Tween 20 [35] | A non-ionic detergent added to buffers to reduce nonspecific binding and bead aggregation, improving purity and recovery. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Two-Phase SPE Optimization Workflow

ASAB-SPE Nucleic Acid Extraction Pathway

Magnetic Bead Purification Logic

In nucleic acid research, the purity of your final extract is paramount. Contaminating genomic DNA (gDNA) in RNA preps, or RNA in DNA samples, can lead to inaccurate quantification, failed reactions, and misleading results in sensitive downstream applications like qPCR, sequencing, and genotyping. This guide provides targeted strategies for researchers to diagnose, troubleshoot, and resolve these common contamination challenges, ensuring the integrity of your nucleic acid extracts from complex or chemically-treated samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my RNA still contaminated with genomic DNA even after using a standard isolation kit? Virtually no RNA isolation method consistently produces DNA-free RNA without a specific DNase digestion step. Contamination occurs because the physical and chemical processes that lyse cells to release RNA also release genomic DNA, which can co-purify due to its similar properties. This is true for both phenol-based (e.g., TRIzol) and silica column-based methods [38] [18]. The solution is to incorporate a dedicated DNase treatment into your protocol.

2. How can I quickly check my RNA sample for DNA contamination? You can use several methods to detect DNA contamination:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Visualize the RNA. DNA contamination will appear as a high molecular weight smear or band above the 28S ribosomal RNA band [39] [40].

- "Minus-RT" Control: In an RT-PCR experiment, include a control that contains all components except the reverse transcriptase. If a PCR product is generated, it was amplified from contaminating DNA, not your RNA [38].

- Spectrophotometry: While a 260/280 ratio below ~1.8 may suggest protein contamination, UV absorbance is not a reliable method for detecting gDNA contamination on its own [39] [40].

3. What is the most effective method for removing DNA from my RNA sample? The most effective and reliable method is treatment with DNase I, followed by complete inactivation or removal of the enzyme. The key is using an optimized system that ensures complete DNA digestion without harming your RNA or leaving behind active DNase that can degrade your downstream reaction components [38]. On-column DNase treatment during purification is a highly effective and convenient approach [40].

4. How do I remove RNA contamination from a DNA sample? The standard method is to treat the DNA sample with RNase. A recommended protocol is to add RNase I (which works in standard buffers like TE) to your DNA sample and incubate at 30°C for 20 minutes. Following digestion, the RNase can be removed using magnetic bead cleanups (e.g., AMPure XP) or spin columns. Do not heat-inactivate the RNase, as heating can denature your DNA and introduce biases in subsequent library prep steps [39].

5. My RNA has good concentration but performs poorly in RT-PCR. What could be wrong? This is often caused by carryover of salts or inhibitors from the extraction process. A low 260/230 ratio in spectrophotometry indicates guanidine salt or organic compound carryover, which can inhibit enzymatic reactions. The solution is to perform additional wash steps with 70-80% ethanol during a column-based cleanup or to re-precipitate the RNA [18] [41]. Also, ensure that any DNase used has been properly inactivated or removed [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting RNA Isolation and DNase Treatment

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Contamination | No DNase step in protocol; inefficient homogenization | Incorporate an on-column or in-solution DNase treatment [18] [40]. Improve mechanical homogenization to shear gDNA [2] [18]. |

| Low RNA Yield | Incomplete cell lysis; RNA degradation | Optimize lysis with mechanical disruption (bead beating) and/or enzymatic treatment (proteinase K) [40]. Stabilize samples immediately upon collection using lysis buffer or DNA/RNA Shield [40]. |

| Poor RNA Purity (Low 260/230) | Carryover of guanidine salts or other inhibitors | Add extra wash steps with 70-80% ethanol during column purification [18] [41]. Ensure the eluate is clear of any wash buffer before elution. |

| DNase I is Inefficient | Suboptimal reaction conditions; presence of inhibitors | Use an optimized DNase digestion buffer [38]. Ensure the RNA sample is free of chelating agents like EDTA, which can inhibit DNase activity. |

| RNA Degradation Post-DNase | Harsh DNase inactivation method | Avoid heat inactivation in the presence of divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) which catalyze RNA hydrolysis [38]. Use a specialized DNase Removal Reagent for gentle and effective inactivation [38]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting DNA Isolation and RNase Treatment

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Contamination | No RNase step in protocol | Treat DNA sample with RNase I (e.g., 1 µl per sample, incubate at 30°C for 20 min) [39]. |

| Incomplete RNase Removal | Use of heat inactivation | Do NOT heat-inactivate RNase I. Remove the enzyme using a magnetic bead cleanup or spin column after digestion is complete [39]. |

| DNA Degradation after RNase Treatment | RNase contamination in final sample | Always purify the DNA sample after RNase treatment using bead-based methods or spin columns to remove the enzyme [39]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: On-Column DNase I Treatment for RNA Purification

This protocol is integrated into many commercial RNA kits and is highly effective for removing gDNA contamination during extraction [40].

- Sample Lysis: Lyse your sample (cells, tissue, etc.) in an appropriate lysis buffer. Ensure complete homogenization.

- Bind RNA: Apply the lysate to the RNA purification column and centrifuge. The RNA binds to the silica membrane, while many contaminants pass through.

- DNase I Digestion: Prepare a master mix of DNase I and the provided digestion buffer. Pipet this mix directly onto the center of the silica membrane.

- Incubate: Incubate the column at room temperature for 15-20 minutes. This allows the DNase I to digest any bound genomic DNA.

- Wash and Elute: Proceed with the standard wash steps to remove the DNase and other impurities. Elute your DNA-free RNA in nuclease-free water.

Protocol 2: In-Solution DNase Treatment and Removal with a Specialized Reagent

This protocol is for treating RNA that has already been purified but still shows DNA contamination [38].

- Set Up Reaction: Combine your RNA sample with 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer and RNase-free DNase I.

- Incubate: Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Remove DNase: Add a specialized DNase Removal Reagent directly to the reaction mix. Flick the tube to mix and incubate at room temperature for 2 minutes.

- Centrifuge: Centrifuge the tube for 1 minute. The DNase Removal Reagent, with the bound DNase and cations, will form a pellet.

- Recover RNA: Carefully transfer the supernatant, which contains your purified, DNA-free RNA, to a new tube. It is now ready for downstream applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nucleic Acid Decontamination

| Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| RNase-free DNase I | Digests contaminating genomic DNA in RNA samples. | Must be certified RNase-free; provided with an optimized reaction buffer for maximum activity [38]. |

| DNase Removal Reagent | Inactivates and removes DNase I after digestion. | Enables simple, room-temperature inactivation without hazardous phenol or heat-induced RNA damage [38]. |

| RNase I | Digests contaminating RNA in DNA samples. | Active in common buffers like TE; does not require a specific reaction buffer [39]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Sample Stabilization Reagent | Inactivates nucleases upon contact, stabilizing nucleic acids in samples at room temperature for transport and storage [40]. |

| Magnetic Beads (e.g., AMPure XP) | Post-reaction cleanup. | Used to remove enzymes like RNase I after digestion, ensuring they do not interfere with downstream steps [39]. |

| Beta-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | RNase Inactivation | Added to lysis buffer to inactivate RNases and stabilize RNA during extraction from tough samples [18]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Strategic DNase Treatment Workflow for RNA Purification

RNA Removal Protocol from DNA Samples

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for On-Chip Nucleic Acid Extraction

Frequently Asked Questions

1. My on-chip extraction yields low amounts of nucleic acid. What could be the cause? Low yield is often due to inefficient cell lysis or incomplete elution. For complex samples like saliva, ensure your lysis buffer is optimized. The POC-Pure method, for instance, uses a custom buffer with guanidine HCl and proteinase K for effective RNase inactivation and viral lysis in salivary samples [42]. Also, verify that the binding conditions (e.g., chaotropic salt concentration) are correct for your specific chip's silica membrane [42] [14].

2. I am getting inhibitors in my final eluate that affect downstream LAMP. How can I improve purity? Inhibitors often carry over from the sample matrix if washing steps are inefficient. Ensure wash buffers contain appropriate alcohols and salts to remove contaminants like proteins and saccharides without eluting the nucleic acid [14]. For salivary samples, the incorporation of a three-way valve actuator in the microfluidic chip can help optimize these wash steps [42].

3. My microfluidic chip frequently gets clogged, especially with complex samples. Clogging is typically caused by cellular debris or particulates in the lysate. Implement a pre-clearing step by centrifugation or filtration before loading the lysate onto the chip [14]. Furthermore, using xurographic and laser-cut chips designed with appropriate channel dimensions can mitigate this issue [42].

4. The heating within my cartridge is inconsistent during thermal lysis or elution. Inconsistent heating is a common design challenge. Ensure a lack of air gaps between the heating blocks in the reader and the well in the cartridge. The use of a soft, thermally conductive interface material can improve heat transfer [43]. Optimizing the thickness of the heat spreader is also crucial; a thinner spreader (e.g., 0.25mm) can reduce the time to reach a stable temperature by over 65% compared to a 4mm spreader [43].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: High Background or Low Signal in Downstream Detection

- Potential Cause: Excessive shearing of DNA or RNA during extraction, leading to fragments that are too small.

- Solution: Optimize mechanical homogenization parameters. If using a bead-based method, control the speed, cycle duration, and bead type to efficiently lyse cells while minimizing mechanical stress on the nucleic acids [2].

Issue: DNA Degradation During the Extraction Process

- Potential Cause: Incomplete inactivation of nucleases (DNases, RNases), especially in biofluids like saliva.

- Solution: Formulate your extraction buffer to include effective nuclease inhibitors. The POC-Pure method addresses this by optimizing conditions for RNase inactivation using reducing agents and guanidine HCl [42]. Ensure fresh buffers are used, as contaminated buffers can also cause issues [44].

Performance Data and Protocol Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies on on-chip and magnetic nanoparticle-based nucleic acid extraction methods, providing a benchmark for your experiments.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Emerging Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Sample Input Volume | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Reported Cost for 96 preps | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Chip (POC-Pure) [42] | 200 µL | DNA: <0.25 copies/µLRNA: <0.5 copies/µL | Not specified | Point-of-care salivary diagnostics |

| MNP-based (Tris-HCl Protocol) [12] | Not specified | Not specified | ~17.76 EUR | Bacterial plasmid & genomic DNA |

| Commercial Column-based Kit [12] | Not specified | Not specified | ~1283.96 EUR | General purpose |

| Traditional (Phenol-Chloroform) [12] | Not specified | Not specified | ~35.08 EUR | General purpose |

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Chemistries

| Chemistry | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Suitability for POC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silica-based [14] [45] | Binding to silica under high-salt chaotropic conditions | Well-established, high purity | Requires multiple steps for binding/washing | Good (can be adapted to chips) |

| Magnetic Beads [12] [45] | Nucleic acids bind to coated magnetic particles | Amenable to automation, no centrifugation | Requires magnet, potential for bead aggregation | Excellent |

| Cellulose-based [14] | Binding to cellulose in high salt and alcohols | High concentration eluates | Less common, protocols may be less optimized | Moderate |

| Phenol-Chloroform [45] | Solubility partitioning in organic phases | Effective for difficult samples | Uses toxic reagents, labor-intensive | Poor |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid On-Chip Nucleic Acid Extraction for Saliva

This protocol is adapted from the POC-Pure method for microfluidic chips [42].

- RNase Inactivation and Lysis: Mix 200 µL of salivary sample with the custom POC-Pure lysis buffer. The buffer contains guanidine HCl (a chaotropic salt), reducing agents, and proteinase K. Incubate at an optimized temperature to inactivate nucleases and lyse viral particles.

- Loading and Binding: Transfer the lysate to the inlet reservoir of the microfluidic chip. Activate the fluidic system (e.g., via integrated pumps, centrifugal force, or vacuum) to move the lysate across a silica membrane. The chaotropic conditions facilitate the binding of nucleic acids to the silica surface.

- Washing: Using the chip's fluidic architecture, pass wash buffers containing salt and ethanol through the membrane. This step removes proteins, inhibitors, and other contaminants. A three-way valve actuator can be used to precisely control buffer flow.

- Elution: Introduce a low-ionic-strength elution buffer (e.g., nuclease-free water or TE buffer) to the membrane. Purified nucleic acids are released into a small volume eluate, which is collected from the output reservoir for downstream analysis.

Protocol 2: MNP-Based DNA Isolation from Bacterial Cultures

This protocol is adapted from cost-effective methods using magnetic nanoparticles [12].

- Synthesis of MNPs: Synthesize Nickel Ferrite (NiFe2O4) nanoparticles using an ultrasonic polyol method. Transition metal nitrate salts and iron nitrate are dissolved in polyethylene glycol (PEG) and sonicated. The resulting nanoparticles are heated to 300°C for 3 hours to form a magnetizable spinel structure [12].

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend the bacterial pellet in a lysis buffer. This can be a traditional lysis buffer or an optimized buffer like Tris-HCl with NaCl.

- Binding to MNPs: Add the synthesized NiFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles to the cleared lysate. Incubate to allow DNA to adsorb onto the surface of the MNPs.

- Magnetic Separation: Place the tube on a magnetic stand to aggregate the MNP-DNA complexes. Carefully discard the supernatant containing contaminants.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the pellet with an ethanol-based wash buffer while it is retained by the magnet. Elute the pure DNA in water or Tris-EDTA buffer after removing the magnetic field.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for On-Chip NA Extraction

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) [42] [14] | Disrupts cells, inactivates nucleases, and enables nucleic acid binding to silica matrices. | Key component in the POC-Pure lysis and binding buffer [42]. |