Optimizing High-Content Phenotypic Screening Protocols: From Foundational Principles to AI-Enhanced Workflows

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing high-content phenotypic screening (HCS) protocols.

Optimizing High-Content Phenotypic Screening Protocols: From Foundational Principles to AI-Enhanced Workflows

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing high-content phenotypic screening (HCS) protocols. It covers foundational principles, exploring the resurgence of phenotypic screening and its advantages in discovering first-in-class therapies. The piece delves into advanced methodological approaches, including the choice between multiplexed dye assays like Cell Painting and targeted fluorescent ligands, and the integration of AI for image analysis. A significant focus is placed on practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common challenges like positional effects, batch variation, and data complexity. Finally, it addresses validation and comparative analysis, detailing how to benchmark performance, integrate multi-omics data, and ensure regulatory compliance. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to design robust, scalable, and informative HCS campaigns that accelerate drug discovery.

Understanding High-Content Phenotypic Screening: Core Principles and Resurgence in Drug Discovery

Defining High-Content Phenotypic Screening and Its Role in Modern Drug Discovery

High-content screening (HCS), also known as high-content analysis (HCA) or cellomics, is an advanced method in biological research and drug discovery that identifies substances which alter cellular phenotypes in a desired manner [1]. This approach combines automated high-resolution microscopy with multiparametric quantitative data analysis to capture complex cellular responses to genetic or chemical perturbations [2] [3]. Unlike target-based screening that focuses on specific molecular interactions, phenotypic screening observes the overall effect on cells without presupposing a target, making it particularly valuable for complex diseases where mechanisms of action are unknown [4] [5] [3].

The technology has evolved significantly since its inception, driven by advances in automated digital microscopy, fluorescent labeling, and image analysis software [1]. Modern HCS platforms can simultaneously monitor multiple biochemical and morphological parameters in intact biological systems, providing spatially and temporally resolved information at subcellular levels [1] [6]. This systems-level perspective enables researchers to capture the complexity of cellular responses that single-target approaches might miss, positioning HCS as a powerful tool for functional genomics, toxicology, and drug discovery [3].

Key Applications in Drug Discovery

Primary Compound Screening and Hit Identification

HCS enables the evaluation of large chemical libraries through automated, image-based assays that quantify multiple cellular features simultaneously [7]. This multiparametric approach allows researchers to identify compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes in a single-pass screen, significantly accelerating early-stage drug discovery [7]. The rich phenotypic profiles generated facilitate the grouping of compounds by similarity of induced cellular responses, enabling functional annotation of compound libraries even without prior knowledge of molecular targets [7].

Mechanism of Action Studies and Target Deconvolution

By capturing diverse cytological responses, HCS phenotypic profiles can classify compounds with different cellular mechanisms of action (MOA) [6]. The technology enables inference of MOA through "guilt-by-association" approaches, where compounds producing similar phenotypic profiles are predicted to share biological targets or pathways [7] [6]. This application has proven particularly valuable for characterizing cellular responses to compounds with diverse reported MOAs and low structural similarity [6].

Functional Genomics and Target Discovery

HCS has been widely adopted for genomic screening to identify genes responsible for specific biological processes [1] [3]. Through combination with RNAi technology, libraries of RNAis covering entire genomes can be used to identify gene subsets involved in specific mechanisms, facilitating the annotation of genes with previously unestablished functions [1]. This application leverages the ability of HCS to detect subtle phenotypic changes resulting from genetic perturbations.

Toxicology and Safety Assessment

HCS provides a sensitive approach for predictive toxicology assessment during drug development [3]. The imaging capabilities enable single-cell level endpoint assessment, allowing focus on particular cell types and providing better understanding of cellular toxicity modes of action [3]. Studies have demonstrated that HCS cell counting identifies cytotoxic compounds with approximately twice the accuracy of alternative methods such as ATP content assays [3].

Table 1: Key Applications of High-Content Screening in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Primary Purpose | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Screening | Identification of bioactive compounds from large libraries | Multiparametric readouts; single-pass screening across multiple mechanisms |

| Mechanism of Action Studies | Classification of compounds by biological activity | Guilt-by-association profiling; prediction of cellular targets |

| Functional Genomics | Elucidation of gene function through phenotypic analysis | Genome-wide coverage; annotation of uncharacterized genes |

| Toxicology Assessment | Prediction of compound safety and cytotoxicity | Higher accuracy than biochemical assays; single-cell resolution |

| Lead Optimization | Refinement of compound efficacy and specificity | Structural-activity relationships in physiological context |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Workflow for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

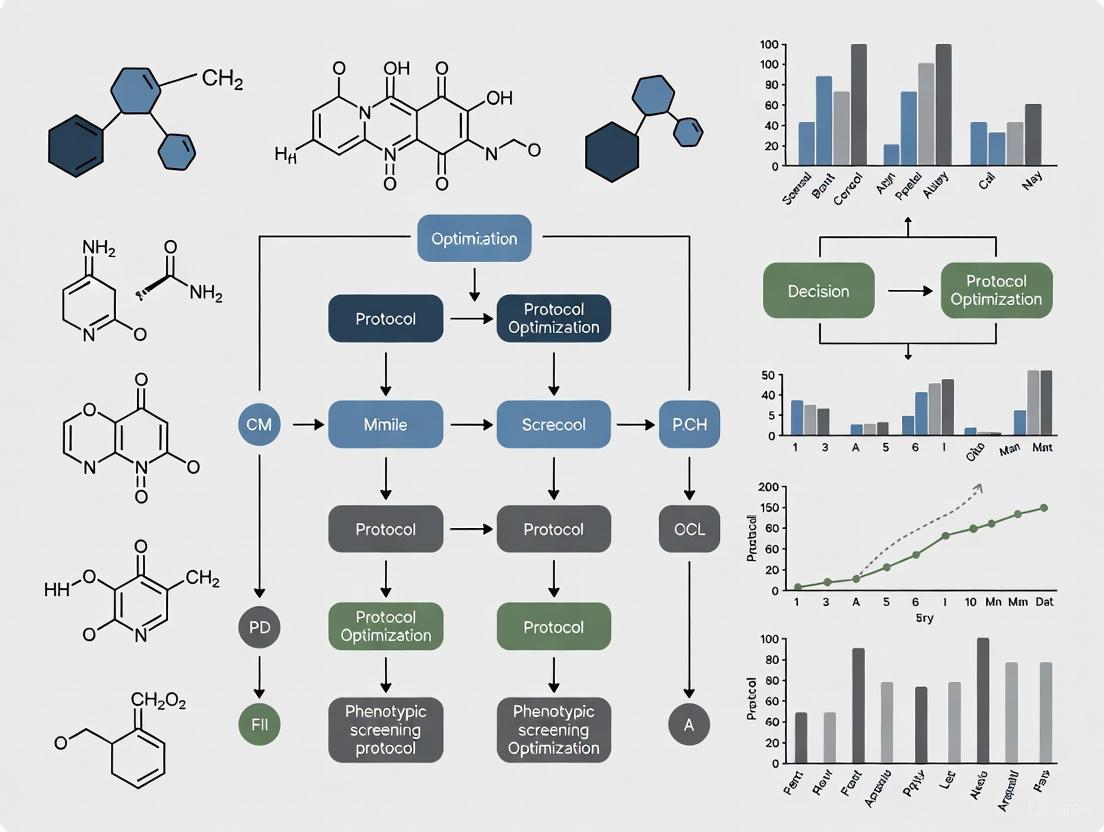

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for high-content phenotypic screening:

Detailed Protocol: High-Content Screening for Cancer Cachexia

A recent study demonstrated an advanced high-content phenotypic screening system to identify drugs that ameliorate cancer cachexia-induced inhibition of skeletal muscle cell differentiation [8]. The following protocol details the methodology:

Cell Culture and Differentiation

- Cell Line: Human skeletal muscle myoblasts (HSMM) were maintained in expansion medium according to supplier specifications [8].

- Differentiation Induction: Myoblast differentiation was induced by switching to differentiation medium containing 2% horse serum when cells reached 70-80% confluence [8].

- Experimental Groups: Cells were divided into three treatment groups: (1) control with normal human serum, (2) cachectic stimulus with cancer patient serum (from grade III colon cancer patients), and (3) therapeutic testing with cachectic stimulus plus HDAC inhibitors [8].

Compound Treatment and Stimulation

- Cachexia Induction: Cancer cachexia serum (Serum E from Table 1 of the source study) was added at the initiation of differentiation (Day 0) to test inhibition of differentiation, or after differentiation (Day 5) to test induction of atrophy [8].

- Therapeutic Intervention: Various HDAC inhibitors, particularly broad-spectrum inhibitors, were tested for their ability to ameliorate the cachexia-induced phenotype [8].

- Time Course: Cells were treated for 4 days (for differentiation inhibition assessment) or 4 days post-differentiation (for atrophy assessment) [8].

Immunostaining and Labeling

- Fixation: Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Staining: Immunostained for myosin heavy chain (MHC) using appropriate primary and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies to identify differentiated myotubes [8].

- Nuclear Counterstaining: Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI to enable automated cell segmentation and counting.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

- Microscopy: Automated high-throughput microscopy was performed using a high-content imaging system.

- Image Analysis: Myotube area and thickness were quantified using automated image analysis algorithms [8].

- Quantification Parameters: Myotube area and thickness were normalized to control groups, with 0% representing undifferentiated cells in expansion medium and 100% representing cells cultured in differentiation medium with normal human serum [8].

Protocol: Broad-Spectrum Phenotypic Profiling

An alternative comprehensive protocol for broad-spectrum phenotypic profiling was described in a 2022 study that maximized detectable cellular phenotypes [6]:

Multiplexed Assay Panel Design

- Cellular Compartments: The assay simultaneously monitored ten cellular compartments using fluorescent markers: DNA, RNA, mitochondria, plasma membrane and Golgi (PMG), lysosomes, peroxisomes, lipid droplets, ER, actin, and tubulin [6].

- Staining Protocol: Cells were stained with appropriate fluorescent dyes and genetically encoded reporters distributed across multiple fluorescent channels to minimize bleed-through [6].

Compound Treatment and Experimental Design

- Compound Library: 65 compounds with diverse mechanisms of action and low structural similarity were tested [6].

- Dosing Strategy: Seven concentrations of each compound were tested in a dilution series to capture dose-dependent responses [6].

- Plate Design: 384-well plates with 55 control wells distributed across all rows and columns to detect and correct for positional effects [6].

- Replication: Three technical replicates were performed for each compound, distributed across multiple plates [6].

Feature Extraction and Profiling

- Feature Measurement: 16 cytological features were measured for individual cells for each marker across four panels, totaling 174 texture, shape, count, and intensity features [6].

- Phenotypic Profiling: Cellular responses were transformed into phenotypic profiles using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics to compare feature distribution differences between treated and control cells [6].

- Data Integration: The analysis pipeline included positional effect adjustment, data standardization, statistical metric comparisons, and feature reduction [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Features Measured in High-Content Phenotypic Screening

| Feature Category | Specific Measurements | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological Features | Cell area, nuclear area, cellular perimeter, form factor, eccentricity | Cell health, cytoskeletal organization, apoptosis |

| Intensity Features | Total intensity, average intensity, intensity standard deviation | Protein expression levels, activation states |

| Texture Features | Haralick texture features, granularity, local contrast | Subcellular distribution, organelle organization |

| Spatial Features | Distance between compartments, radial distribution, correlation between channels | Protein translocation, organelle interactions |

| Population Features | Cell count, mitotic index, cell cycle distribution | Proliferation, cytotoxicity, cell cycle effects |

Analytical Methods and Data Processing

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for image analysis and phenotypic profiling in HCS:

Statistical Framework for Phenotypic Profiling

Advanced statistical methods are crucial for interpreting high-content screening data [6]. The workflow includes:

Quality Control and Positional Effect Adjustment

- Positional Effect Detection: Two-way ANOVA models identify row and column effects on control well features, with approximately 45% of intensity-related features exhibiting significant positional dependencies [6].

- Data Correction: Median polish algorithm iteratively calculates and corrects for row and column effects within each plate [6].

- Standardization: Cell-level data standardization enables integration of features from multiple marker panels and different plates [6].

Phenotypic Profile Generation

- Distribution-based Metrics: Wasserstein distance metric outperforms other measures for detecting differences between cell feature distributions, capturing changes in distribution shape beyond mean shifts [6].

- Feature Reduction: Dimensionality reduction techniques identify the most informative features for phenotypic profiling [6].

- Profile Visualization: Phenotypic trajectories visualize dose-dependent responses in low-dimensional latent space [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HCS |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells, U2OS osteosarcoma cells, primary cells, patient-derived cells | Provide biological context; disease modeling; A549 preferred for transfection efficiency and imaging characteristics [7] [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, RFP, CFP, YFP fusion proteins; H2B-CFP for nuclear labeling; mCherry for whole-cell segmentation | Enable live-cell tracking; compartment-specific labeling; automated cell segmentation [7] |

| Chemical Dyes | Hoechst 33342 (DNA), Syto14 (RNA), MitoTracker (mitochondria), Phalloidin (actin) | Vital staining of cellular compartments; fixed-cell imaging; multiplexed readouts [6] |

| Immunofluorescence Reagents | Primary antibodies against specific targets; fluorescent secondary antibodies | Target-specific protein detection; post-translational modification assessment [2] |

| Assay Plates | 384-well and 96-well microtiter plates with clear flat black bottoms | Optimized for automated imaging; minimal background fluorescence; compatible with liquid handlers [2] |

Case Study: Integration with AI and Multi-Omics Technologies

The future of high-content phenotypic screening lies in integration with artificial intelligence and multi-omics technologies [5]. Advanced platforms like PhenAID demonstrate how AI can bridge the gap between phenotypic screening and actionable insights by integrating cell morphology data with omics layers and contextual metadata [5]. This integration enables:

- Predictive Modeling: AI algorithms interpret massive, noisy datasets to detect meaningful patterns that correlate with mechanism of action, efficacy, or safety [5].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining HCS with transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provides a systems-level view of biological mechanisms [5].

- Target Identification: Computational backtracking of observed phenotypic shifts can identify biological targets without target-based screening [5].

Notable successes include the identification of HDAC inhibitors as potential therapeutics for cancer cachexia through phenotypic screening [8], and the discovery of novel antibiotics using GNEprop and PhenoMS-ML models that interpret imaging and mass spectrometry phenotypes [5]. These examples demonstrate how integrative approaches reduce timelines and enhance confidence in hit validation.

In the modern drug discovery landscape, the strategic selection between phenotypic and target-based screening approaches is pivotal for navigating the complexity of disease biology and improving the efficiency of therapeutic development [9]. Phenotypic screening identifies compounds based on their observable effects on cells, tissues, or whole organisms without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target, thereby capturing the complexity of biological systems [4] [10]. In contrast, target-based screening focuses on identifying compounds that interact with a predefined, well-characterized molecular target, enabling a mechanism-driven approach [9] [4].

Historically, drug discovery relied heavily on phenotypic approaches, but the late 20th century saw a major shift toward target-based strategies, facilitated by advances in genomics and high-throughput screening technologies [11]. However, the analysis by Swinney and Anthony revealed that a majority of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2008 originated from phenotypic screening, prompting a resurgence in its application [11] [12]. Today, the integration of both paradigms, accelerated by artificial intelligence (AI), multi-omics technologies, and advanced disease models, is reshaping drug discovery pipelines [4] [13]. This document provides a detailed comparative analysis and experimental protocols to guide researchers in strategically applying and optimizing these approaches.

Comparative Analysis: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening Approaches

| Feature | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Identifies compounds based on functional, observable effects in a biological system (cells, tissues, organisms) [10]. | Screens for compounds that modulate a predefined molecular target (e.g., protein, enzyme) [10]. |

| Knowledge Prerequisite | No prior knowledge of a specific molecular target is required [4] [12]. | Requires a well-validated molecular target with a hypothesized role in the disease [9] [4]. |

| Mechanism of Action (MoA) | MoA is often unknown at the discovery stage, requiring subsequent deconvolution [10] [14]. | MoA is defined and understood from the outset of the screening campaign [9]. |

| Throughput & Complexity | Can be lower throughput due to complex assays (e.g., high-content imaging); more resource-intensive [9] [10]. | Typically high-throughput, using simpler, miniaturized biochemical assays; more cost-effective [11] [10]. |

| Key Advantage | Unbiased discovery of novel mechanisms; captures complex biology and polypharmacology; higher rate of first-in-class drug discovery [9] [10] [12]. | Mechanistically clear; enables rational, structure-based drug design; generally more straightforward optimization [9] [10]. |

| Primary Challenge | Target deconvolution can be difficult, time-consuming, and costly [10] [15] [14]. | Reliant on incomplete disease knowledge; may fail if the target hypothesis is flawed [9] [11]. |

| Ideal Application | Diseases with poorly understood molecular mechanisms (e.g., neurodegenerative disorders, rare diseases), or when seeking first-in-class therapies [9] [11] [10]. | Diseases with well-validated molecular targets and established pathway biology (e.g., oncology with defined oncogenes) [9] [4]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics and Historical Output Comparison

| Metric | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening | Notes & Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-in-Class Drugs (1999-2008) | ~62% | ~38% | Analysis by Swinney & Anthony, cited in [11]. |

| Representative Drugs | Artemisinin (malaria), Lithium (bipolar), Sirolimus (immunosuppressant), Venlafaxine (antidepressant) [9] [11]. | Imatinib (CML), Trastuzumab (breast cancer), Zidovudine (HIV) [9]. | |

| Typical Hit Validation Timeline | Longer (weeks to months, due to required target deconvolution) [15] [14]. | Shorter (days to weeks, as the target is known) [9]. | |

| AI-Enhanced Discovery Timeline | Can be significantly compressed. Example: Exscientia's AI-design cycle reported ~70% faster [13]. | Can be significantly compressed. Example: Insilico Medicine's drug candidate to Phase I in 18 months [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Content Phenotypic Screening for Cancer Cachexia

This protocol details a phenotypic screen to identify compounds that ameliorate the inhibition of skeletal muscle cell differentiation induced by cancer cachexia (CC) serum [16].

I. Biological Model and Cell Culture

- Cell Line: Commercially available Human Skeletal Muscle Myoblasts (HSMMs).

- Culture Conditions: Maintain HSMMs in growth medium according to supplier specifications. For differentiation, switch to an appropriate differentiation medium upon reaching confluence.

- Pathophysiological Stimulus: Use serum from cancer patients (e.g., grade III colon cancer) as a disease-relevant stimulus. Pooled healthy human serum serves as a control.

II. Assay Setup and Compound Treatment

- Plate HSMMs in a multi-well plate suitable for high-content imaging.

- Induce Differentiation by switching to differentiation medium.

- Apply Stimulus and Library: Simultaneously add cancer cachexia serum (e.g., 10% v/v) and compounds from the screening library to the wells. Include control wells with normal serum and DMSO vehicle.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 4 days to allow for myotube formation under the influence of the serum stimuli and compounds.

III. High-Content Imaging and Analysis

- Fixation and Staining: On day 4, fix cells and perform immunocytochemistry for skeletal muscle mass detection. Stain myotubes with an antibody against Myosin Heavy Chain (MHC) and use a fluorescent secondary antibody. Use DAPI or Hoechst for nuclear counterstaining.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution images using an automated high-content imaging system.

- Quantitative Phenotypic Analysis: Use image analysis software to quantify:

- Myotube Area: The total area occupied by MHC-positive structures.

- Myotube Thickness: The average diameter of the formed myotubes.

- Fusion Index: The number of nuclei within myotubes versus the total number of nuclei.

- Hit Selection: Identify "hits" as compounds that significantly restore myotube area and thickness towards levels observed in the healthy serum control.

IV. Validation and Counterscreening

- Dose-Response: Confirm active compounds in a dose-response experiment to determine potency (EC50).

- Cytotoxicity Counterscreening: Test hit compounds in a parallel viability assay (e.g., ATP-based assay) to exclude compounds that improve the phenotype simply by inducing cytotoxicity.

Protocol 2: A Phenotype-to-Target Workflow with Integrated Deconvolution

This protocol outlines a strategy for identifying a compound's molecular target following a phenotypic hit, using a p53 pathway activator screen as an example [15].

I. Primary Phenotypic Screening

- Phenotypic Assay: Utilize a high-throughput luciferase reporter system. Employ a cell line engineered with a luciferase gene under the control of a p53-responsive promoter.

- Screening Execution: Screen a compound library for agents that increase luciferase activity, indicating enhanced p53 transcriptional activity.

- Hit Confirmation: Confirm phenotypically active compounds (e.g., UNBS5162) in secondary assays, such as measuring endogenous p53 protein levels and transcription of downstream targets like p21.

II. Target Deconvolution via Knowledge Graph and Molecular Docking

- Construct a Protein-Protein Interaction Knowledge Graph (PPIKG): Build a comprehensive graph encompassing proteins and their interactions within the p53 signaling pathway and related networks.

- Candidate Target Prediction: Use the PPIKG to analyze the phenotypically validated hit. The graph narrows down potential protein targets from a vast number (e.g., 1088) to a focused, manageable set (e.g., 35) based on network proximity and functional linkage to the observed phenotype [15].

- Virtual Screening (Molecular Docking): Perform molecular docking of the hit compound (UNBS5162) against the shortlist of candidate proteins (e.g., MDM2, USP7, etc.) to evaluate binding affinity and pose.

- Prioritization: Integrate PPIKG inference scores and docking scores to prioritize the most likely direct target(s) for experimental validation (e.g., USP7).

III. Experimental Target Validation

- Cellular Binding Assays: Use techniques like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) or affinity-based pulldown to confirm direct binding between the hit compound and the prioritized target (USP7) in a cellular context [14].

- Functional Validation: Employ genetic knockdown (siRNA/shRNA) or CRISPR knockout of the putative target. The expectation is that knocking down the true target will diminish or abolish the compound's phenotypic effect (p53 activation).

- Biochemical Assays: Conduct in vitro enzymatic assays (e.g., USP7 deubiquitinase assay) to demonstrate direct functional modulation by the compound.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Biological Fluids | Provides a pathophysiologically relevant stimulus containing the complex mix of factors present in disease. | Cancer cachexia patient serum used to induce a disease phenotype in muscle cells [16]. |

| Stem Cell-Derived Models (iPSCs) | Enables patient-specific disease modeling and screening in relevant human cell types. | iPSC-derived neurons for neurodegenerative disease screening [10]. |

| 3D Organoids / Spheroids | Provides a more physiologically relevant model that better mimics tissue architecture and function than 2D cultures. | Used in cancer and neurological research for more predictive compound screening [10]. |

| High-Content Imaging Reagents | Fluorescent dyes and antibodies for multiplexed detection of phenotypic features (morphology, protein localization). | Anti-Myosin Heavy Chain (MHC) antibody for quantifying myotube formation [16]. |

| Affinity-Based Probes | Chemically modified versions of a hit compound used to immobilize and "pull-down" its direct protein targets from a complex lysate. | Key tool for target deconvolution; service available as "TargetScout" [14]. |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) Probes | Trifunctional probes (compound, photoreactive group, handle) that covalently crosslink to targets upon UV light, ideal for membrane proteins or transient interactions. | Service available as "PhotoTargetScout" for challenging target deconvolution [14]. |

| Label-Free Target ID Reagents | Compounds and reagents for techniques like thermal proteome profiling (TPP), which detects target engagement by measuring ligand-induced protein stability shifts. | Enables target deconvolution without chemical modification of the hit compound ("SideScout" service) [14]. |

| AI/ML-Driven Discovery Platforms | Integrated software and data platforms that use AI for generative chemistry, phenomic analysis, and predicting drug-target interactions. | Platforms from Exscientia, Recursion, Insilico Medicine used to accelerate both phenotypic and target-based discovery [13]. |

The strategic choice between phenotypic and target-based screening is not a matter of selecting a universally superior approach, but rather of aligning the strategy with the specific biological and therapeutic context [9] [12]. Phenotypic screening offers an unbiased path to novel biology and first-in-class medicines, particularly for diseases of unknown or complex etiology. Target-based screening provides a mechanism-focused, efficient route for optimizing interventions against validated pathways.

The future of drug discovery lies in the flexible and intelligent integration of both paradigms [4]. The convergence of advanced disease models, multi-omics technologies, and sophisticated AI-driven analytics is creating a new landscape where the initial phenotypic discovery of a hit can be rapidly followed by AI-assisted target deconvolution and structure-based optimization in a unified workflow [13] [15]. By leveraging the complementary strengths of both strategies, researchers can enhance the efficacy, speed, and success rate of bringing new therapeutics to patients.

High-content phenotypic screening (HCS) has emerged as a transformative approach in biological research and drug discovery, enabling the multiparametric analysis of cellular responses to genetic or chemical perturbations. This methodology integrates three core technological pillars: automated microscopy for high-throughput image acquisition, advanced fluorescent labeling for specific biomarker visualization, and sophisticated quantitative image analysis for extracting meaningful biological data. The optimization of these components is critical for enhancing screening accuracy, reproducibility, and biological relevance, particularly as the field advances toward more physiologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) model systems [17] [18]. The convergence of these technologies within a single workflow allows researchers to capture complex phenotypic profiles that serve as powerful fingerprints for classifying compound mechanisms of action, identifying novel therapeutics, and understanding fundamental biological processes in systems ranging from simple 2D monolayers to complex 3D-oid models that better mimic in vivo conditions [17] [7].

The evolution of HCS represents a paradigm shift from traditional target-based screening toward a more holistic, systems-level approach to studying cellular function. Where high-throughput screening (HTS) rapidly tests large compound libraries against single targets, HCS captures rich, image-based phenotypic data, providing deeper biological insights beyond simple activity counts [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying first-in-class therapeutics and uncovering unanticipated biological interactions, as demonstrated by the discovery of immunomodulatory drugs like thalidomide and its derivatives through phenotypic screening [4]. The continued refinement of HCS protocols through technological innovation addresses key challenges in drug discovery, including the need for improved predictive accuracy, reduced attrition rates, and enhanced translation from in vitro models to clinical applications.

Quantitative Fluorescent Labeling Protocols

Ratiometric Method for Determining Labeling Efficiency

Fluorescent labeling efficiency is a crucial parameter that directly impacts the accuracy and quantitative potential of high-content screening, particularly for single-molecule studies where incomplete labeling can significantly distort interaction analyses. Traditional methods for estimating labeling yield suffer from critical limitations, including inaccurate quantification and dissimilarity to actual experimental conditions. To address these challenges, a robust ratiometric method has been developed to precisely quantify fluorescent-labeling efficiency of biomolecules under experimental conditions [19].

This protocol employs sequential labeling with two different fluorophores to mathematically determine labeling efficiency. The method operates by performing two labeling reactions in sequence, where the molecules available for the second reaction are those unlabeled during the first reaction. By inverting the order of fluorophore application in parallel samples and measuring the ratio of labeled molecules, the efficiency for each probe can be precisely calculated using defined mathematical relationships [19].

Workflow for Labeling Efficiency Determination:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical samples expressing the target biomolecule of interest. For membrane proteins like TrkA receptors, this involves cell cultures with appropriately tagged receptors [19].

- Sequential Labeling (Order 1):

- Perform first labeling reaction with fluorescent Probe A (e.g., Atto 565)

- Perform second labeling reaction with fluorescent Probe B (e.g., Abberior STAR 635p) on the same sample

- Sequential Labeling (Order 2):

- Perform first labeling reaction with fluorescent Probe B

- Perform second labeling reaction with fluorescent Probe A on a parallel sample

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images using appropriate microscopy systems (e.g., TIRF microscopy for membrane proteins) [19].

- Quantification: Measure the ratio (r) of molecules labeled in the first reaction to those labeled in the second reaction for both experimental orders.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate labeling efficiencies using the derived equations:

- Efficiency for Probe A: eA = (r × r' - 1)/(r × r' + r')

- Efficiency for Probe B: eB = (r × r' - 1)/(r × r' + r) [19]

This method enables researchers to optimize labeling strategies by systematically varying parameters such as dye concentration, reaction timing, and enzyme concentration (for enzyme-based labeling systems like Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase). The protocol has demonstrated particular utility for demanding single-molecule and multi-color experiments requiring high degrees of labeling, achieving conditions never previously reported for Sfp-based labeling systems [19].

Fluorescent Labeling Strategies for Bioimaging

The selection of appropriate fluorescent labeling strategies is fundamental to successful high-content screening, with implications for specificity, resolution, and quantitative accuracy. Recent advances in fluorescent labeling have transformed biological imaging by enabling visualization of cellular structures and processes at the molecular level, particularly through super-resolution microscopy (SRM) techniques that circumvent the diffraction limit of light [20].

Key Considerations for Fluorescent Labeling:

- Labeling Density: Optimal labeling density is crucial for accurate representation of biomolecular distributions and interactions. insufficient density can lead to false negative results, while excessive labeling may cause steric hindrance or non-specific binding [19] [20].

- Linkage Error: The physical distance between the fluorophore and the actual biomolecule of interest can introduce measurement inaccuracies, particularly in super-resolution applications. Minimizing linkage error through appropriate tag selection and positioning is essential for precise localization [20].

- Labeling Specificity: Ensuring that fluorescent signals originate only from the intended target requires careful optimization of labeling conditions and thorough validation using appropriate controls [19].

- Multi-color Compatibility: For experiments requiring multiple fluorophores, careful selection of dyes with non-overlapping emission spectra and similar brightness characteristics is necessary for accurate quantification and interpretation [19].

Table 1: Fluorescent Labeling Techniques for High-Content Screening

| Labeling Technique | Mechanism | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunofluorescence | Antibody-antigen binding with fluorescent dyes | Protein localization, post-translational modifications | High specificity, wide commercial availability | Fixed cells only, potential cross-reactivity |

| Fluorescent Proteins | Genetically encoded (GFP, RFP, etc.) | Live-cell imaging, protein trafficking | Non-invasive, enables longitudinal studies | Maturation time, photostability limitations |

| Sfp Transferase | Covalent attachment of CoA-functionalized probes | Cell surface receptor labeling, single-molecule studies | Small tag size, high specificity | Requires multiple components, optimization needed |

| Self-Labeling Tags (HALO/SNAP) | Covalent binding to synthetic ligands | Live-cell imaging, pulse-chase experiments | Modular, diverse fluorophore options | Larger tag size may affect function |

| Chemical Dyes | Non-covalent association with cellular structures | Organelle labeling, viability assessment | Simple implementation, often cell-permeable | Potential non-specific binding |

For quantitative imaging applications, protocol optimization must address challenges such as fluorophore photobleaching, sample preparation variability, and antibody specificity validation. Studies have demonstrated that many antibodies producing single bands on Western blots may not perform optimally for immunofluorescence due to differences in protein folding and epitope accessibility between techniques [21]. Therefore, independent validation using knockout controls or correlation with orthogonal methods is recommended when establishing new labeling protocols [21].

Automated Microscopy and 3D Imaging Systems

Advanced Imaging Modalities for HCS

Automated microscopy forms the backbone of high-content screening by enabling the rapid, standardized acquisition of vast image datasets from thousands of experimental conditions. The selection of appropriate imaging modalities depends on experimental requirements, with considerations for resolution, speed, phototoxicity, and sample compatibility. Fluorescence microscopy remains the cornerstone of HCS, allowing multiplexed detection of multiple cellular markers simultaneously through specific fluorescent tagging [18]. However, label-free imaging approaches such as phase-contrast or brightfield microscopy are gaining traction for live-cell imaging and longitudinal studies where phototoxicity and sample preparation simplicity are paramount [18].

Confocal microscopy, particularly laser point-scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM), represents a significant advancement for HCS applications by eliminating out-of-focus light through optical sectioning, thereby producing sharper images with improved resolution [21]. This technique utilizes a laser beam focused to a diffraction-limited spot in the specimen, with emitted light passing through a pinhole to reject out-of-focus light before detection by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs). The resulting digital images represent matrices of intensity values that can be quantitatively analyzed to extract meaningful biological information [21].

Essential Considerations for Quantitative Image Acquisition:

- Objective Lens Selection: The choice of objective lens significantly impacts imaging quality and field of view. Higher magnification objectives (e.g., 40x/1.3 Oil, 40x/1.2 W) provide greater cellular detail but reduce field of view and may introduce selection bias if imaging non-representative regions. Tile scanning with image stitching can overcome this limitation by providing comprehensive specimen views [21].

- Detector Linearity: Ensuring microscope detectors operate within their linear range is critical for quantitative intensity measurements. Saturation effects can distort data and prevent accurate quantification of fluorescence intensity [21].

- Standardized Imaging Conditions: Maintaining consistent exposure times, laser powers, and focus settings across experimental batches is essential for reproducible, comparable results [18] [21].

- Quality Control: Regular instrument calibration and implementation of automated quality control protocols help maintain imaging consistency and data reliability across large screening campaigns [18].

3D High-Content Screening Systems

The limitations of two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures in recapitulating physiological tissue environments have driven the development of 3D high-content screening platforms. Systems like HCS-3DX represent next-generation approaches that combine engineering innovations, advanced imaging, and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to enable single-cell resolution analysis within complex 3D models including spheroids, organoids, and tumouroids (collectively termed "3D-oids") [17].

The HCS-3DX platform addresses key challenges in 3D screening through three integrated components:

- AI-driven micromanipulation for selecting morphologically homogeneous 3D-oids using tools like the SpheroidPicker, which combines morphological pre-selection with automated pipetting to ensure experimental reproducibility [17].

- Specialized imaging hardware including custom Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene (FEP) foil multiwell plates optimized for light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM), which provides high imaging penetration with minimal phototoxicity and photobleaching [17].

- AI-based data analysis workflows implemented in specialized software (e.g., Biology Image Analysis Software - BIAS) for automated segmentation, classification, and feature extraction from complex 3D datasets [17].

Table 2: Comparison of 3D High-Content Screening Platforms

| Platform/Technology | Imaging Modality | Resolution | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCS-3DX | Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) | Single-cell level in 3D-oids | High with AI-assisted selection | High penetration depth, minimal phototoxicity | Specialized equipment required |

| Confocal HCS | Point-scanning confocal | Subcellular | Moderate to high | Optical sectioning, widely available | Photobleaching concerns in thick samples |

| SpheroidPicker | Brightfield/fluorescence | Tissue level pre-selection | High for initial selection | Reduces variability in 3D-oid analysis | Additional instrumentation needed |

| Conventional Widefield | Widefield fluorescence | Limited by out-of-focus light | High | Rapid imaging, lower cost | Limited penetration in thick samples |

Validation studies of the HCS-3DX system have demonstrated its ability to quantify tissue composition at single-cell resolution in both monoculture and co-culture tumor models, revealing significant heterogeneity in 3D-oid morphology even when generated by experts following identical protocols [17]. This variability underscores the importance of standardized, automated selection processes for ensuring reproducible 3D screening outcomes.

Quantitative Image Analysis and Data Management

Feature Extraction and Phenotypic Profiling

Quantitative image analysis transforms raw pixel data into biologically meaningful information through computational approaches that extract, process, and interpret cellular features. The phenotypic profiling workflow typically involves multiple stages: image preprocessing and segmentation to identify cellular and subcellular compartments, feature extraction to quantify morphological and intensity parameters, and data reduction/analysis to identify patterns and classify phenotypes [18] [7].

The phenotypic profiling approach involves three key transformations:

- Images to Feature Distributions: ~200 features of morphology (nuclear and cellular shape characteristics) and protein expression (intensity, localization, texture properties) are measured for each cell [7].

- Distributions to Numerical Scores: For each feature, differences between perturbed and unperturbed conditions are quantified using statistical measures such as the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic, which compares cumulative distribution functions [7].

- Scores to Phenotypic Profiles: KS scores are concatenated across features to form a phenotypic profile vector that succinctly summarizes compound effects, enabling comparison across different experimental conditions [7].

This approach has proven valuable for classifying compounds into functional categories based on similarity of induced cellular responses, effectively implementing a "guilt-by-association" strategy for mechanism of action prediction [7]. The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has further enhanced analysis capabilities by improving segmentation accuracy in heterogeneous samples and enabling identification of subtle phenotypic patterns that may escape conventional analysis [18].

Data Management and FAIR Principles

The substantial data generated by high-content screening—potentially hundreds of thousands of images from a single experiment—presents significant data management challenges. Effective solutions must integrate and link diverse data types including images, reagents, protocols, analytic outputs, and phenotypes while ensuring accessibility to researchers, collaborators, and the broader scientific community [22].

The OMERO (Open Microscopy Environment Remote Objects) platform has emerged as a flexible, open-source solution for managing biological image datasets, providing centralized storage for images and metadata alongside tools for visualization, analysis, and collaborative sharing [22]. When integrated with workflow management systems (WMS) like Galaxy or KNIME, OMERO enables the creation of reproducible, semi-automated pipelines for data transfer, processing, and analysis [22].

Essential components of effective HCS data management:

- Standardized Data Formats: Adoption of open standards like OME-TIFF ensures interoperability across different analysis platforms and facilitates long-term data accessibility [22].

- Metadata Annotation: Comprehensive metadata capture, including experimental conditions, assay parameters, and analysis protocols, is crucial for experimental reproducibility and data interpretation [22].

- Workflow Integration: Connecting data management platforms with analytical workflows through APIs (e.g., OMERO Python API, ezomero library) enables automated data processing while maintaining provenance tracking [22].

- FAIR Compliance: Implementing Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles ensures that HCS data remains a valuable resource for future research and meta-analyses [22].

Recent implementations demonstrate that automated bioimage workflows can bridge local storage systems and dedicated data management platforms by consistently transferring images in a structured, reproducible manner across different locations, significantly improving efficiency while reducing error likelihood [22].

Implementation Protocols and Research Toolkit

Integrated Protocol for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Optimization

- Biomarker Selection: Identify optimal reporter cell lines or labeling strategies based on biological questions. The ORACL (Optimal Reporter cell line for Annotating Compound Libraries) approach systematically identifies reporter cell lines whose phenotypic profiles most accurately classify training drugs across multiple drug classes [7].

- Assay Development: Optimize cell culture conditions, treatment parameters, and labeling protocols using quantitative methods like the ratiometric labeling efficiency determination [19]. For 3D models, implement standardized generation protocols and AI-assisted selection to minimize variability [17].

- Control Selection: Include appropriate positive and negative controls (e.g., DMSO vehicle controls, reference compounds with known mechanisms) for assay validation and normalization [7].

Phase 2: Sample Preparation and Labeling

- Cell Culture: Plate cells in appropriate vessels (standard multiwell plates for 2D, U-bottom cell-repellent plates for 3D spheroids) at optimized densities [17] [7].

- Treatment: Apply compounds at multiple concentrations and time points to capture diverse phenotypic responses and establish dose-response relationships [7].

- Fluorescent Labeling: Implement validated labeling protocols, considering factors such as dye permeability, specificity, and photostability. For fixed cells, perform immunofluorescence with thoroughly validated antibodies [21]. For live-cell imaging, utilize genetically encoded fluorescent proteins or cell-permeable dyes [7].

Phase 3: Image Acquisition

- Microscope Setup: Configure automated microscope with appropriate objectives, light sources, and filters. Establish focusing system to maintain consistency across large sample sets [18] [21].

- Acquisition Parameters: Define imaging locations per well, exposure times, and z-stack settings (if applicable). Ensure detector operation within linear range for quantitative measurements [21].

- Quality Control: Implement automated quality assessment during acquisition to flag focus failures, contamination, or other artifacts [18].

Phase 4: Image Analysis and Data Interpretation

- Preprocessing: Apply background correction, flat-field normalization, and other preprocessing steps as needed [21].

- Segmentation: Identify cells and subcellular compartments using appropriate algorithms (threshold-based, machine learning, etc.) [18].

- Feature Extraction: Calculate morphological, intensity, and texture features for each segmented object [7].

- Phenotypic Profiling: Generate phenotypic profiles by comparing feature distributions between treated and control samples [7].

- Hit Identification: Use statistical analysis and machine learning to identify compounds inducing significant phenotypic changes and classify them based on profile similarity [18] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Content Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HCS Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Reporters | pSeg plasmid (mCherry RFP + H2B-CFP), CD-tagged proteins (YFP) [7] | Enable automated segmentation and monitoring of protein expression | Endogenous expression levels, preservation of functionality |

| Fluorescent Labels | Atto 565, Abberior STAR 635p [19] | Specific biomarker visualization | Labeling efficiency, photostability, spectral separation |

| Cell Lines | A549 (non-small cell lung cancer), HeLa Kyoto, MRC-5 fibroblasts [17] [7] | Provide cellular context for screening | Transfection efficiency, morphological characteristics |

| 3D Culture Systems | U-bottom cell-repellent plates [17] | Support spheroid formation for physiologically relevant models | Reproducibility, uniformity of 3D-oids |

| Fixation and Permeabilization | Paraformaldehyde, methanol, Triton X-100 [21] | Preserve cellular structures and enable antibody access | Antigen preservation, membrane integrity |

| Validation Tools | Knockout-verified antibodies, isotype controls [21] | Confirm labeling specificity and assay performance | Specificity verification, reduction of false positives |

| Image Analysis Software | BIAS, CellProfiler, ReViSP [17] | Extract quantitative data from images | Algorithm accuracy, processing speed, usability |

This toolkit provides the fundamental components for implementing robust high-content screening workflows. The selection of specific reagents should be guided by experimental goals, with particular attention to validation and compatibility across the integrated workflow. As the field advances, continued refinement of these tools—especially through the incorporation of AI-driven analysis and more physiologically relevant model systems—will further enhance the predictive power and translational potential of high-content phenotypic screening in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has experienced a major resurgence following a surprising observation: between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered empirically without a predetermined target hypothesis [23]. Modern PDD represents a strategic shift from reductionist target-based approaches, instead focusing on identifying compounds that produce therapeutic effects in realistic disease models without requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [23] [24]. This renaissance is characterized by the integration of classical concepts with cutting-edge tools, including high-content imaging, functional genomics, and sophisticated data analysis pipelines, enabling researchers to systematically pursue drug discovery based on observable therapeutic effects in physiologically relevant systems [23].

The fundamental driver for this renewed interest stems from PDD's demonstrated ability to expand "druggable target space" to include unexpected cellular processes and novel mechanisms of action (MoA) [23]. Unlike target-based drug discovery (TDD), which relies on established causal relationships between molecular targets and disease, PDD employs a biology-first strategy that provides tool molecules to link therapeutic biology to previously unknown signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms [23]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for complex, polygenic diseases where single-target strategies have shown limited success, and for situations where no attractive molecular target is known to modulate the pathway or disease phenotype of interest [23].

Technological Advances Driving Modern Phenotypic Screening

High-Content Imaging and Profiling

The scalability of phenotypic screening has been dramatically enhanced through high-content imaging technologies that enable multi-parametric measurement of cellular responses [7]. Image-based profiling transforms compounds into quantitative vectors that capture systems-level responses in individual cells, summarizing effects on cell morphology, protein localization, and expression patterns [7]. These phenotypic profiles serve as distinctive fingerprints that can classify compounds by similarity of their induced cellular responses, enabling mechanism-of-action prediction through guilt-by-association principles [7] [25].

Advanced profiling techniques now include:

- Cell Painting: An image-based assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles [25].

- Live-cell reporters: Genomically tagged endogenous proteins that enable monitoring of protein expression and localization in living cells over time [7].

- Transcriptomic profiling: L1000 assay that measures gene expression responses to compound treatment [25].

Recent studies demonstrate that combining these profiling modalities with chemical structure information can significantly enhance compound bioactivity prediction. When chemical structures are augmented with phenotypic profiles, the number of assays that can be accurately predicted increases from 37% with chemical structures alone to 64% with combined data [25].

Optimal Reporter Selection and Experimental Design

A critical innovation in phenotypic screening is the systematic identification of optimal reporter cell lines for annotating compound libraries (ORACLs) [7]. This approach involves constructing a library of fluorescently tagged reporter cell lines and using analytical criteria to identify which reporter produces phenotypic profiles that most accurately classify training drugs across multiple mechanistic classes [7]. The ORACL strategy enables accurate functional annotation of large compound libraries across diverse drug classes in a single-pass screen, significantly increasing the efficiency and discriminatory power of phenotypic screens [7].

For cancer drug discovery, refined screening approaches now incorporate:

- Patient-derived cancer cells cultured in tumor-relevant microenvironments to improve disease relevance [26].

- Larger biological panels that capture disease heterogeneity [26].

- Multi-omic readouts that increase information content [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: High-Content Phenotypic Profiling Using Live-Cell Reporters

Objective: To classify compounds into functional categories based on their induced phenotypic profiles in live-cell reporter systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Triply-labeled reporter cell lines (e.g., A549 non-small cell lung cancer line)

- pSeg plasmid for cell segmentation (mCherry for whole cell, H2B-CFP for nucleus)

- Central Dogma (CD)-tagged biomarkers (YFP-tagged endogenous proteins)

- Compound library with appropriate controls (DMSO vehicle)

- Live-cell imaging medium

- 96-well or 384-well optical-grade microplates

- High-content imaging system with environmental control

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Plating:

- Maintain triply-labeled reporter cells under standard conditions.

- Plate cells in optical-grade microplates at optimized density (e.g., 2,000-5,000 cells/well for 384-well format).

- Allow cells to adhere and recover for 24 hours before compound treatment.

Compound Treatment:

- Prepare compound dilutions in appropriate vehicle (typically DMSO, final concentration ≤0.1%).

- Treat cells with test compounds, controls, and vehicle controls using automated liquid handling.

- Include multiple time points (e.g., 24h and 48h) for temporal profiling.

Image Acquisition:

- Acquire images every 12 hours for 48 hours using automated microscopy.

- Capture multiple fields per well to ensure adequate cell sampling (≥500 cells/condition).

- Maintain environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂) throughout time-course experiments.

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction:

- Segment individual cells using nuclear and cytoplasmic markers.

- Extract ~200 features of morphology and protein expression including:

- Morphological features: nuclear/cytoplasmic size, shape descriptors, texture

- Protein expression features: intensity, localization, spatial patterns

- Process images using automated pipelines (e.g., CellProfiler, custom algorithms)

Phenotypic Profile Generation:

- For each feature, compute differences between treated and control distributions using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics.

- Concatenate KS scores across all features to generate phenotypic profile vectors.

- Generate replicate profiles from multiple control samples to establish baseline variability.

Profile Analysis and Compound Classification:

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques to visualize profile relationships.

- Use clustering algorithms to group compounds with similar phenotypic profiles.

- Validate classification accuracy using compounds with known mechanisms.

Protocol: Quantitative Phenotypic Screening for Helmintic Diseases

Objective: To automatically quantify and cluster phenotypic responses of parasites to drug treatments using time-series analysis.

Materials:

- Adult schistosomes or other relevant helminths

- Compound libraries

- 96-well culture plates

- Automated imaging systems

- Image analysis software with custom algorithms

Procedure:

- Parasite Preparation and Compound Treatment:

- Isolate and culture adult parasites under appropriate conditions.

- Transfer individual parasites to wells containing serial compound dilutions.

- Include vehicle controls and reference compounds.

Time-Lapse Imaging:

- Acquire images at regular intervals (e.g., hourly) over 24-72 hours.

- Maintain appropriate environmental conditions throughout imaging.

Phenotypic Quantification:

- Apply biological image analysis to automatically quantify:

- Shape-based phenotypes: body length, width, curvature

- Appearance-based phenotypes: tegument texture, gut content

- Motion-based phenotypes: motility patterns, frequency of movement

- Represent phenotypes as time-series data.

- Apply biological image analysis to automatically quantify:

Time-Series Analysis and Clustering:

- Compare phenotypic responses using appropriate similarity measures.

- Cluster parasites based on similarity of phenotypic responses.

- Identify distinct response groups and correlate with compound classes.

Key Successes and Applications

Notable First-in-Class Therapies from Phenotypic Approaches

Table 1: Approved Drugs Discovered Through Phenotypic Screening

| Drug | Disease | Target/MoA | Key Screening Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivacaftor, Tezacaftor, Elexacaftor | Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR potentiators/correctors | Cell-based assays measuring CFTR function [23] |

| Risdiplam, Branaplam | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modulators | Phenotypic screens identifying splicing modifiers [23] |

| Daclatasvir | Hepatitis C | NS5A inhibitor | HCV replicon phenotypic screen [23] |

| Lenalidomide | Multiple Myeloma | Cereblon E3 ligase modulator | Observations of efficacy in leprosy and multiple myeloma [23] |

| SEP-363856 | Schizophrenia | Unknown novel target | Phenotypic screen in disease-relevant models [23] |

| KAF156 | Malaria | Unknown novel target | Phenotypic screening against parasite [23] |

| Crisaborole | Atopic Dermatitis | PDE4 inhibitor | Phenotypic screening for anti-inflammatory effects [23] |

Predictive Performance of Different Profiling Modalities

Table 2: Assay Prediction Accuracy by Data Modality (AUROC > 0.9)

| Profiling Modality | Number of Accurately Predicted Assays | Unique Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure (CS) | 16 | No wet lab required; enables virtual screening |

| Morphological Profiles (MO) | 28 | Captures systems-level cellular responses |

| Gene Expression (GE) | 19 | Provides transcriptional regulation insights |

| CS + MO (combined) | 31 | Leverages complementary information |

| All modalities combined | 64% of assays (at AUROC > 0.7) | Maximum predictive coverage [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Triply-labeled reporter cell lines | Enable simultaneous monitoring of multiple cellular features | Combine segmentation markers with pathway-specific reporters [7] |

| CD-tagging vectors | Genomic labeling of endogenous proteins | Preserves native expression levels and functionality [7] |

| pSeg plasmid | Automated cell segmentation | Expresses mCherry (cell) and H2B-CFP (nucleus) for robust identification [7] |

| High-content imaging dyes | Multi-parameter cell staining | Cell Painting uses 5-6 fluorescent dyes to mark organelles [25] |

| Patient-derived primary cells | Enhanced disease relevance | Maintains pathological characteristics in culture [24] [26] |

| 3D culture matrices | Tissue-relevant microenvironment | Improves physiological accuracy for complex diseases [24] |

| L1000 assay reagents | Gene expression profiling | Cost-effective transcriptomic profiling at scale [25] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Phenotypic Screening Workflow

Workflow Overview: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for modern phenotypic screening, from initial planning through mechanism of action studies.

Multi-Modal Predictor Integration

Predictor Integration: This diagram shows how different data modalities are combined to enhance assay outcome prediction accuracy.

The resurgence of phenotypic screening represents a fundamental evolution in drug discovery philosophy, acknowledging the limitations of purely reductionist approaches while leveraging modern technological capabilities. By focusing on therapeutic outcomes in physiologically relevant systems, PDD has consistently delivered first-in-class medicines that modulate novel targets and mechanisms [23]. The continued refinement of phenotypic approaches—through improved disease models, multi-parametric readouts, and advanced data analysis—promises to further enhance their impact on therapeutic discovery.

Future directions in the field include increased integration of functional genomics with phenotypic screening, application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to decipher complex phenotypic responses, and development of more sophisticated human disease models that better capture patient heterogeneity and disease complexity [23]. As these technological innovations mature, phenotypic screening is poised to remain a vital approach for expanding the druggable genome and delivering novel therapeutics for challenging diseases.

High Content Screening (HCS) has evolved into a cornerstone technology for modern drug discovery and cellular analysis, combining high-throughput screening with automated microscopy and multiparametric data analysis. The market is experiencing robust growth, propelled by the demand for personalized medicines, increased research and development activities, and technological advancements [27].

Table 1: Global High Content Screening Market Size and Growth Projections

| Metric | Details |

|---|---|

| 2024 Market Size | USD 1.52 billion [27] |

| 2025 Market Size | Ranging from USD 1.63 billion [27] to USD 1.9 billion [28] |

| Projected 2034 Market Size | USD 3.12 billion [27] |

| Projected 2030 Market Size | USD 2.2 billion [29] |

| CAGR (2025-2034) | 7.54% [27] |

The adoption of HCS is widespread, with over 72% of pharmaceutical companies integrating HCS platforms into early-stage research. North America is the dominant region, holding a 39% revenue share in 2024, followed by Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, which is expected to witness the fastest growth [27] [30].

Key Market Drivers and Segment Analysis

Primary Growth Drivers

- Demand for Novel Drug Discovery: The increasing prevalence of chronic disorders drives the need for new therapeutics. HCS is essential in early stages for target validation and candidate optimization, enabling researchers to analyze multiple cellular parameters simultaneously [27].

- Rise of Personalized Medicine: The growth in precision medicine, particularly in oncology, creates major opportunities for HCS. About 61% of oncology research centers deploy HCS to evaluate biomarker-driven therapies [30].

- Government Initiatives and Funding: Favorable government support, such as the Indian government's "PRIP" scheme with a budget of Rs 5,000 crores to promote pharma MedTech R&D, enables the development and use of HCS [27]. In the United States, NIH and BARDA invest over USD 45 billion annually in life sciences [28].

- Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI and machine learning streamline the analysis of complex HCS datasets, enhancing efficiency and accuracy. AI-powered HCS systems can reduce screening time by up to 30% while improving image fidelity [27] [28]. In 2024, 48% of new HCS products featured integrated AI imaging platforms [30].

Market Segmentation

The HCS market is segmented by product, application, technology, and end-user, each with distinct growth trajectories.

Table 2: High Content Screening Market Segmentation and Leadership

| Segment | Leading Sub-Segment | Key Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| By Product | Instruments | Held ~37% market share in 2025 [28] [30]. |

| By Product | Software | Expected to witness the fastest growth, driven by AI/ML-based analysis tools [27]. |

| By Application | Toxicity Studies | Accounted for the highest revenue share (~28%) in 2024 [27]. |

| By Application | Phenotypic Screening | Expected to show the fastest growth over the forecast period [27]. |

| By Technology | 2D Cell Culture | Held the largest revenue share (~42%) in 2024 [27]. |

| By Technology | 3D Cell Culture | Expected to grow with the highest CAGR; offers superior physiological relevance [27]. |

| By End-User | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies | Held a dominant share (~46%) in 2024 [27]. |

| By End-User | Contract Research Organizations (CROs) | Expected to expand rapidly due to outsourcing trends [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for High Content Phenotypic Screening

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for conducting high content phenotypic screening assays in both 2D and 3D cell culture models, optimized for efficiency and reproducibility.

Protocol 1: 2D High Content Phenotypic Screening for Toxicity and Target Identification

This protocol is designed for high-throughput, multiplexed analysis of cellular events in monolayer cultures.

Workflow Diagram: 2D Phenotypic Screening Protocol

Materials and Reagents

- Cells: Appropriate cell line for the biological question (e.g., HeLa, HepG2, primary cells).

- Microplates: 96-well or 384-well optically clear bottom microplates [30].

- Cell Culture Medium: Complete medium (e.g., DMEM, RPMI-1640) supplemented with FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics.

- Compound Library: Small molecules, siRNAs, or other perturbagens dissolved in DMSO or aqueous buffer.

- Fixative: 4% Formaldehyde or Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

- Permeabilization Buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Staining Reagents:

- Hoechst 33342: Nuclear stain (e.g., 1 µg/mL).

- Phalloidin (e.g., conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488): F-actin stain for cytoskeleton.

- Primary and Secondary Antibodies: For specific protein targets (e.g., anti-tubulin for microtubules).

- Wash Buffer: 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Imaging Buffer: PBS or commercial anti-fade mounting medium.

Procedure

Cell Seeding (Day 1):

- Harvest cells and prepare a single-cell suspension. Determine cell count and viability.

- Seed cells into microplates at an optimized density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for a 96-well plate) in 100 µL of complete medium. The density should allow for 50-70% confluency at the time of assay.

- Incubate plates overnight at 37°C, 5% CO₂ to allow for cell attachment and recovery.

Compound Treatment (Day 2):

- Prepare serial dilutions of test compounds in culture medium. Include positive (e.g., known cytotoxic agent) and negative (DMSO vehicle) controls.

- Remove the existing medium from the microplates and add 100 µL of compound-containing medium to respective wells.

- Incubate plates for the desired treatment duration (e.g., 24, 48 hours) at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Staining and Fixation (Day 3):

- Fixation: Aspirate the medium and carefully add 100 µL of 4% PFA to each well. Incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature (RT).

- Permeabilization: Aspirate PFA and wash wells 3x with 150 µL PBS. Add 100 µL of 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubate for 10 minutes at RT.

- Blocking: Aspirate and add 150 µL of blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS) for 30-60 minutes at RT.

- Immunostaining:

- Prepare primary antibody dilution in blocking buffer.

- Aspirate blocking buffer, add 50-100 µL of primary antibody solution, and incubate for 2 hours at RT or overnight at 4°C.

- Wash wells 3x with PBS.

- Prepare secondary antibody and Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/mL) dilution in blocking buffer.

- Add 50-100 µL of this solution and incubate for 1 hour at RT in the dark.

- Alternative: Direct Staining: For simpler assays, after permeabilization, add a solution containing Hoechst 33342 and Phalloidin conjugate in PBS. Incubate for 30-60 minutes at RT in the dark.

- Perform a final 3x wash with PBS. Leave 100 µL of PBS in each well for imaging.

Image Acquisition (Day 3):

- Use a high-content imaging system (e.g., from Thermo Fisher Scientific, PerkinElmer) with a 20x or 40x objective.

- Acquire images from multiple sites per well (e.g., 9-16 sites) to ensure statistical robustness.

- Capture fluorescence channels for all dyes used (e.g., DAPI for nuclei, FITC for cytoskeleton, Cy5 for target protein).

Image and Data Analysis (Day 3-4):

- Use integrated HCS software (e.g., from Genedata AG, BioTek Instruments) or standalone AI-powered analysis tools.

- Steps in Analysis Workflow:

- Nuclei Identification: Use the Hoechst channel to segment individual nuclei.

- Cell Segmentation: Use the cytosolic stain (e.g., Phalloidin) to define the cytoplasmic boundary for whole-cell analysis.

- Phenotypic Feature Extraction: Measure hundreds of features per cell, including intensity, texture, morphology, and spatial relationships.

- AI-Powered Classification: Employ machine learning models to classify cells into phenotypic classes based on the extracted features [27] [30].

Protocol 2: 3D Spheroid-Based Phenotypic Screening

This protocol leverages 3D cell culture models, which more accurately mimic in vivo conditions and are increasingly used in oncology and toxicity studies [27] [29].

Workflow Diagram: 3D Spheroid Screening Protocol

Materials and Reagents

- Cells: Cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, U-87 MG) or patient-derived cells.

- Microplates: Ultra-low attachment (ULA) round-bottom plates (96-well or 384-well) to promote spheroid formation.

- Spheroid Formation Medium: Standard culture medium, often supplemented with growth factors.

- Viability Stains:

- Hoechst 33342: Cell-permeant nuclear stain (labels all cells).

- Propidium Iodide (PI): Cell-impermeant stain (labels dead cells with compromised membranes).

- Calcein AM: Cell-permeant dye converted to green fluorescent calcein in live cells (labels live cells).

Procedure

Spheroid Formation (Day 1):

- Prepare a single-cell suspension and seed cells into ULA microplates at an optimized density (e.g., 1,000-5,000 cells/well in 150 µL medium).

- Centrifuge plates at low speed (e.g., 300-500 x g for 3-5 minutes) to aggregate cells at the bottom of the well.

- Incubate plates for 72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ to allow for spheroid formation.

Compound Treatment (Day 4):

- After spheroid formation, prepare compound dilutions in fresh medium.

- Carefully remove 100 µL of the old medium from each well without disturbing the spheroid.

- Add 100 µL of compound-containing medium to respective wells.

- Incubate plates for 72 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

Viability Staining (Day 7):

- Prepare a staining solution in PBS containing Hoechst 33342 (1-2 µg/mL), PI (1-2 µg/mL), and/or Calcein AM (1-4 µM).

- Carefully remove the treatment medium and add 100 µL of the staining solution to each well.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ in the dark.

3D Image Acquisition (Day 7):

- Use a high-content imager equipped with confocal or optical sectioning capabilities (e.g., Yokogawa CellVoyager, PerkinElmer Opera Phenix).

- Acquire Z-stacks through the entire depth of the spheroid (e.g., with a 10µm step size) using objectives suitable for 3D imaging (e.g., 10x water immersion, 20x).

- Capture all relevant fluorescence channels.

3D Image Analysis (Day 7-8):

- Use 3D analysis modules in HCS software.

- Analysis Steps:

- Spheroid Segmentation: Identify the entire 3D spheroid object using the Hoechst channel.

- Viability Analysis: Quantify the intensity and volume of PI (dead cells) and Calcein AM (live cells) signals within the spheroid volume.

- Morphometric Analysis: Calculate spheroid volume, diameter, and integrity.

- Dose-Response Modeling: Fit data to calculate IC₅₀ values for treatment efficacy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for High Content Screening

| Item | Function in HCS | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | Platform for cell culture and assay execution. | 96-well and 384-well formats are standard; black walls with clear bottoms optimize imaging [30]. Ultra-low attachment plates are essential for 3D spheroid formation. |

| Multiplexed Assay Kits | Enable simultaneous measurement of multiple cellular parameters (e.g., viability, cytotoxicity, apoptosis). | Critical for complex phenotypic screening. Reduces well-to-well variability and increases information content per experiment. |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Probes | Visualize and quantify specific cellular components and activities. | Includes nuclear stains (Hoechst), viability indicators (Calcein AM/PI), cytoskeletal markers (Phalloidin), and mitochondrial probes (TMRM). |

| Validated Antibodies | Specific detection of proteins and post-translational modifications via immunostaining. | Antibodies validated for immunofluorescence (IF) provide reliable and specific signal with low background. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Reagents | Allow for kinetic monitoring of cellular processes over time without fixation. | Includes fluorescent biosensors and dyes compatible with live cells. Demand for live-cell imaging in clinical research grew 32% [30]. |

| AI-Powered Analysis Software | Automated, high-throughput extraction and interpretation of complex phenotypic data from images. | AI software adoption has increased by 53%, improving predictive accuracy by 42% [30]. Essential for managing large datasets. |

Advanced HCS Assay Design: From Cell Painting to Targeted Fluorescent Ligands

In the realm of high-content phenotypic screening, the choice between a broad, untargeted profiling approach and a focused, targeted strategy is fundamental. Multiplexed dye panels, exemplified by the Cell Painting assay, and targeted fluorescent ligands represent two distinct yet complementary philosophies for quantifying cellular responses to genetic or chemical perturbations. Cell Painting aims to capture a holistic, systems-level view of cellular morphology by simultaneously staining multiple organelles, generating a high-dimensional profile that can detect unanticipated effects [31] [32]. In contrast, assays employing targeted fluorescent ligands are designed to interrogate specific, predefined biological entities—such as a particular receptor population—with high specificity, providing deep mechanistic insights into a focused area of biology [33]. The decision to implement one over the other, or to combine them, hinges on the research goals, whether for initial unbiased discovery or for the detailed mechanistic study of a known target. This application note details the principles, protocols, and applications of both methods to guide researchers in optimizing their high-content screening protocols.

The core distinction between these assays lies in their scope and application. Cell Painting serves as a powerful, unbiased tool for phenotypic discovery and annotation, while targeted fluorescent ligands offer a precise method for probing specific biological mechanisms.

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Multiplexed Dye Panels and Targeted Fluorescent Ligands

| Feature | Multiplexed Dye Panels (Cell Painting) | Targeted Fluorescent Ligands |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Untargeted morphological profiling; hypothesis generation [31] | Targeted investigation of a predefined molecule or pathway [33] |

| Typical Applications | Mechanism of action (MoA) identification, functional gene clustering, toxicity profiling, drug repurposing [31] [34] [32] | Receptor internalization studies, ligand-binding competition assays, target engagement validation [33] |