NGS vs Sanger Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Validating Chemogenomic Hits

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals selecting between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing to validate chemogenomic screening results.

NGS vs Sanger Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Validating Chemogenomic Hits

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals selecting between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing to validate chemogenomic screening results. It covers the foundational principles of both technologies, outlines methodological workflows tailored for hit validation, delves into common troubleshooting scenarios, and presents a direct comparative analysis. The guide synthesizes key criteria—including throughput, sensitivity, cost, and accuracy—to empower scientists in building a robust, efficient validation pipeline that ensures the reliability of therapeutic targets and accelerates the drug discovery process.

Core Sequencing Technologies: Understanding Sanger and NGS Fundamentals

In the dynamic field of genomics, where next-generation sequencing (NGS) enables the parallel analysis of billions of DNA fragments, the Sanger sequencing method remains an indispensable tool, particularly for the critical validation of chemogenomic hits [1] [2]. Often referred to as the "chain-termination method" or first-generation sequencing, this technique was developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977 and continues to be the gold standard for accuracy in targeted sequencing applications [2] [3]. Its unparalleled precision for reading short to medium-length DNA segments makes it an essential final step in research pipelines, ensuring that the genetic variations identified through high-throughput NGS screens are verified with maximum reliability [1] [4]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the core principles, appropriate applications, and technical execution of Sanger sequencing is fundamental to generating robust, publication-quality data.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the Sanger sequencing methodology, focusing on its underlying mechanism of chain termination. It offers a direct comparison with modern NGS platforms and provides detailed protocols to integrate this foundational technique effectively into your chemogenomic research workflow.

The Chemical Principle of Chain Termination

The genius of the Sanger method lies in its elegant use of modified nucleotides to decipher the exact order of bases in a DNA strand. The process relies on the natural function of DNA polymerase, the enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding complementary nucleotides to a single-stranded template [2]. The key to the entire sequencing process is the introduction of dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs) into the reaction mixture alongside the normal deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) [1] [2].

These ddNTPs are crucial chain-terminating agents. Structurally, they are identical to regular dNTPs but lack a 3'-hydroxyl group on their sugar moiety, which is essential for forming a phosphodiester bond with the next nucleotide [2] [5]. When a DNA polymerase incorporates a ddNTP into a growing DNA strand instead of a dNTP, the absence of the 3'-OH group halts any further elongation [1]. This results in a truncated DNA fragment.

In a standard sequencing reaction, millions of template DNA molecules are being copied simultaneously. For any given position in the sequence, there is a random chance that either a dNTP or its corresponding ddNTP will be incorporated. This randomness generates a complete set of DNA fragments of every possible length, all ending at the specific base corresponding to the ddNTP that was incorporated. Modern automated Sanger sequencing uses fluorescently labeled ddNTPs, where each of the four bases (A, T, C, G) is tagged with a distinct fluorescent dye, allowing for the termination events to be detected and distinguished in a single reaction [2] [5].

Diagram 1: The core principle of chain termination in Sanger sequencing, showing how random incorporation of dye-labeled ddNTPs generates a population of fragments of every possible length.

Sanger Sequencing Workflow: A Step-by-Step Protocol

The journey from a biological sample to an analyzed DNA sequence involves a series of meticulous steps. The following protocol, summarized in the workflow diagram below, ensures the generation of high-quality, accurate sequence data.

Library Preparation and Cycle Sequencing

The process begins with DNA template preparation. The source material can vary widely, from bacterial colonies and tissue to blood or plasma, each requiring an appropriate DNA extraction method (e.g., silica column-based, magnetic bead-based, or chemical extraction) to obtain a pure template [5]. For Sanger sequencing, the target region must first be amplified, typically by PCR, using specific primers that flank the region of interest to ensure sufficient template quantity [5]. Following PCR, a clean-up step is critical to remove excess primers and dNTPs that would otherwise interfere with the subsequent sequencing reaction [5].

The core of the method is the cycle sequencing reaction. This is a modified PCR that uses the purified PCR product as a template. Unlike standard PCR, cycle sequencing employs only a single primer to ensure the reaction proceeds in one direction, producing single-stranded fragments [5]. The reaction mixture includes:

- DNA template

- A single sequencing primer

- DNA polymerase

- Normal dNTPs

- Fluorescently labeled ddNTPs

During thermal cycling, the DNA is repeatedly denatured, primers are annealed, and the polymerase extends the strands. The random incorporation of fluorescent ddNTPs terminates the growing chains, producing a nested set of dye-labeled fragments [5].

Capillary Electrophoresis and Data Analysis

After the cycle sequencing reaction, a second clean-up is performed to remove unincorporated dye-labeled ddNTPs, whose fluorescent signals would create background noise [5]. The purified fragments are then injected into a capillary electrophoresis (CE) instrument.

Inside the capillary, which is filled with a polymer matrix, the DNA fragments are separated by size under an electric field, with the shortest fragments migrating fastest [2] [5]. As each fragment passes a laser detector at the end of the capillary, the laser excites the fluorescent dye on its terminal ddNTP. The emitted light is captured, and the color identifies the base (A, T, C, or G) that ended that particular fragment [5]. The instrument's software compiles these signals into a chromatogram, which is a trace of fluorescent peaks, each representing one base in the DNA sequence. Software then translates this chromatogram into a text sequence, assigning a quality score (Phred score) to each base call [6] [5].

Diagram 2: The end-to-end Sanger sequencing workflow, from sample preparation to final data output.

Sanger vs. NGS: A Quantitative Comparison for Validation

Choosing between Sanger sequencing and NGS depends entirely on the research question. The table below provides a direct comparison of their key characteristics, highlighting their complementary roles in a research pipeline.

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination using ddNTPs [1] [2] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis) [1] [6] |

| Throughput | Low (single fragment per reaction) [6] [4] | Ultra-high (millions to billions of fragments per run) [1] [6] |

| Read Length | Long, contiguous reads (500–1000 bp) [1] [2] | Short reads (50–300 bp for short-read platforms) [1] [7] |

| Per-Base Accuracy | Exceptionally high (~99.99%), gold standard for validation [1] [2] | High, but single-read accuracy is lower than Sanger; overall accuracy is achieved through high coverage [1] [8] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low cost per run for small projects; high cost per base [1] [4] | High capital and reagent cost per run; very low cost per base [1] [6] |

| Variant Sensitivity | Low (limit of detection ~15–20%) [4] [8] | High (can detect variants at frequencies of 1% or lower) [4] [8] |

| Optimal Application | Validation of NGS hits, single-gene testing, cloning verification [1] [3] | Whole genomes, transcriptomes, metagenomics, rare variant discovery [1] [6] |

| Data Analysis | Simple; requires basic alignment software [1] | Complex; requires sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines for alignment and variant calling [1] [6] |

| Turnaround Time | Fast for single targets (hours for sequencing) [6] [5] | Longer for full workflow (days for library prep and sequencing) [6] [8] |

Table 1: A direct comparison of Sanger sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing across key technical and operational metrics.

NGS excels at discovery, providing an unbiased, genome-wide view to identify novel genetic variants, expression patterns, and pathways associated with drug response [1] [7]. However, its lower per-read accuracy and complex data analysis necessitate a confirmatory step for high-stakes results. This is where Sanger sequencing is irreplaceable. Its high per-base accuracy and long read lengths make it the ideal choice for validating specific chemogenomic hits—such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or small insertions/deletions (indels)—identified in NGS screens before proceeding to functional studies or reporting findings [1] [4] [3]. A 2025 study on hematological malignancies demonstrated a 99.43% concordance when using orthogonal methods to validate Sanger results, underscoring its reliability as a verification tool [8].

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

The reliability of Sanger sequencing is dependent on the quality and performance of its core components. The following table details the essential reagents required for a successful experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes the template-directed synthesis of new DNA strands during both PCR and the cycle sequencing reaction [5]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled ddNTPs | Chain-terminating nucleotides; each base (A, T, C, G) is marked with a distinct fluorophore, enabling detection and base identification [2] [5]. |

| Sequencing Primers | Short, single-stranded oligonucleotides that are complementary to a known sequence on the template DNA, providing the starting point for DNA polymerase [5]. |

| Purified DNA Template | The sample DNA containing the target region to be sequenced; purity is critical for optimal reaction performance [5]. |

| Capillary Array & Polymer | The physical medium (glass capillaries filled with a viscous polymer) that separates DNA fragments by size via electrophoresis [5]. |

Table 2: Key research reagents and their functions in the Sanger sequencing workflow.

Sanger sequencing, built on the robust and elegant principle of chain termination, maintains its status as the gold standard for accuracy in genetic analysis. While NGS provides an unparalleled powerful tool for discovery-driven science, the precise and targeted nature of Sanger sequencing makes it an indispensable component of the modern researcher's toolkit. Its role in the validation of chemogenomic hits ensures the integrity and reproducibility of research data, forming a critical bridge between high-throughput genetic discovery and downstream functional application. By understanding its principles and optimal use cases, scientists and drug developers can strategically leverage both Sanger and NGS technologies to advance their research with confidence.

The validation of chemogenomic hits demands sequencing technologies that are both precise and capable of handling immense scale. For decades, Sanger sequencing served as the gold standard, providing accurate data for targeted regions. However, its low throughput and high cost per base rendered it impractical for projects requiring the analysis of thousands of genetic targets across numerous samples. The advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), built on the core principle of massively parallel sequencing, has fundamentally altered this landscape [9] [10]. This technology enables the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments, offering ultra-high throughput, scalability, and speed that Sanger sequencing cannot match [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of NGS performance against Sanger sequencing, detailing the core mechanics of NGS and its critical application in validating chemogenomic screening results through structured data, experimental protocols, and key methodological workflows.

Core Mechanics of NGS Technology

The revolutionary power of NGS lies in its ability to deconstruct a genomic sample into countless fragments and read them all at once. This process is a radical departure from the linear, one-sequence-at-a-time approach of Sanger sequencing.

The Foundational Principle: Massive Parallelism

Massively parallel sequencing allows modern NGS platforms to sequence hundreds of thousands to hundreds of millions of DNA fragments concurrently [10]. While Sanger sequencing is limited to a single, pre-defined target per reaction, NGS involves fragmenting the entire sample, sequencing all fragments in parallel, and then computationally mapping the reads to a reference genome [11]. This fundamental difference enables NGS to generate terabytes of data in a single run, making projects like whole-genome sequencing accessible and practical for average researchers [9].

The NGS Workflow: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The standard NGS workflow consists of three key steps, each distinct from Sanger's methodology.

Library Preparation

The process begins by fragmenting the isolated DNA or RNA into a library of small, random, overlapping fragments. These fragments are then ligated to platform-specific adapters, which often include unique molecular identifiers (barcodes) to allow for sample multiplexing—a key feature enabling the cost-effective sequencing of dozens of samples in a single run [12] [13].

Clonal Amplification and Sequencing

Following library preparation, the DNA fragments are amplified to generate clonal template populations. The method varies by platform:

- Bridge Amplification: Used by Illumina, where fragments are amplified on a solid-phase glass flow cell to form clusters [11] [12].

- Emulsion PCR (emPCR): Used by Roche/454 and Ion Torrent, where DNA molecules are amplified on beads in water-in-oil emulsion droplets [11] [12].

The actual sequencing occurs via different biochemical principles, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Core Sequencing Technologies in NGS Platforms

| Technology | Principle | Detection Method | Key Platform Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) | Polymerase-based extension with reversible terminators. | Fluorescently labeled nucleotides are imaged after each incorporation cycle [9] [11]. | Illumina/Solexa [11] [7] |

| Pyrosequencing | Polymerase-based sequential nucleotide addition. | Detection of pyrophosphate release via light emission; intensity correlates with homopolymer length [11] [7]. | Roche/454 [11] [7] |

| Semiconductor Sequencing | Polymerase-based incorporation of natural nucleotides. | Detection of hydrogen ion (H+) release, which changes pH [7] [12]. | Ion Torrent [7] [12] |

| Sequencing by Ligation (SBL) | Ligase-based probe hybridization. | Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes are ligated and imaged [11] [7]. | SOLiD [11] [7] |

Data Analysis and Alignment

The massive volume of short sequencing reads generated must be processed computationally. This involves base calling, quality scoring, and then alignment or assembly of these reads to a reference genome to reconstruct the full sequence and identify variants [12] [13]. This is a fundamental difference from Sanger sequencing, which produces a single continuous read for a targeted region.

Visualizing the NGS Workflow

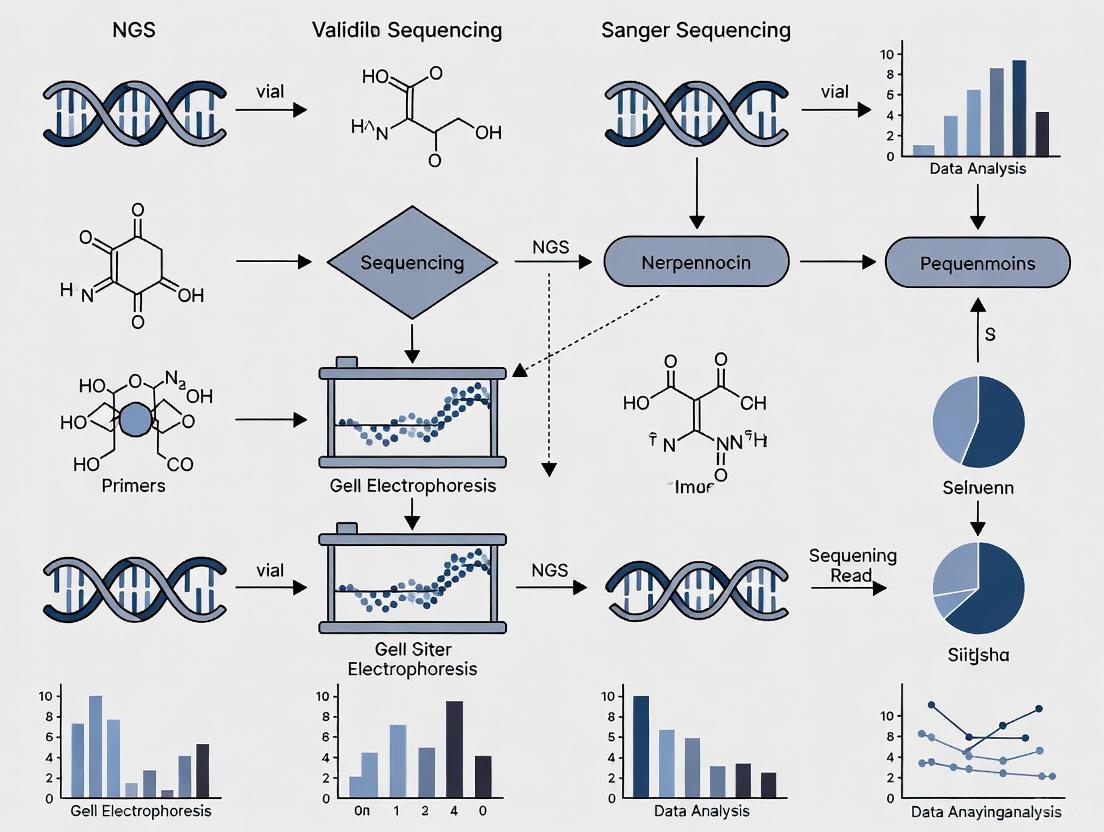

The following diagram illustrates the core steps of the NGS workflow, from sample to analysis.

NGS vs. Sanger Sequencing: A Quantitative Comparison

When validating chemogenomic hits, researchers must choose the appropriate tool based on the project's scope and requirements. The following tables provide a direct, data-driven comparison between the two technologies.

Performance and Output Specifications

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics: NGS vs. Sanger Sequencing

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Implication for Chemogenomic Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (One sequence per reaction) [11] | Very High (Millions to billions of reads per run) [9] [10] | NGS enables genome-wide variant discovery; Sanger is suitable for a few specific targets. |

| Read Length | Long (400-900 bp) [7] | Short (50-600 bp, platform-dependent) [7] [12] | Sanger is superior for resolving complex repeats; NGS short reads can challenge assembly in repetitive regions. |

| Cost per Sample | High for large studies | Low for large-scale sequencing [13] | NGS is more economical for validating hundreds of hits or performing deep, multi-sample profiling. |

| Speed per Run | Slow (Hours to days for multiple targets) | Fast (Days for whole genomes) [13] | NGS provides a faster turnaround for comprehensive datasets. |

| Accuracy | Very High (Error rate: ~0.001%) [12] | High (Error rates: 0.1%-1.78% depending on platform) [12] | Sanger is the gold standard for confirming key mutations; NGS requires high coverage for confident variant calling. |

| Variant Detection | Excellent for SNPs, small indels. | Comprehensive (SNPs, indels, CNVs, SVs, gene expression) [9] [10] | NGS provides a holistic view of genomic alterations, beyond the capability of Sanger. |

| Ideal Use Case | Confirming a few known mutations. | Unbiased discovery of novel variants across the genome or transcriptome. | Sanger for final confirmation; NGS for initial broad screening and hypothesis generation. |

Error Profiles and Technical Limitations

Different NGS platforms exhibit distinct error profiles, which is a critical consideration for detecting low-frequency variants in chemogenomic studies.

Table 3: NGS Platform-Specific Error Profiles and Limitations

| NGS Platform | Primary Error Type | Common Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina/Solexa | Substitution errors in AT-rich and CG-rich regions. | Signal decay over cycles; potential for index misassignment. | [7] [12] |

| Roche/454 | Insertion/Deletion (Indel) errors in homopolymer regions (≥6-8 bp). | High cost per run compared to other NGS platforms. | [7] [12] |

| Ion Torrent | Indel errors in homopolymer regions due to non-linear pH response. | Similar to Roche/454, struggles with long homopolymers. | [7] [12] |

| SOLiD | Substitution errors. | Very short read lengths limit application and complicate assembly. | [7] [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Chemogenomic Hit Validation

To ensure robust and reproducible results, a structured experimental approach is required. The following protocol outlines a typical workflow using NGS for validating chemogenomic screening hits, with a note on orthogonal Sanger validation.

Detailed mNGS Protocol for Pathogen Identification in LRTI

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 clinical study, demonstrates the application of metagenomic NGS (mNGS) for comprehensive pathogen detection, a common scenario in infectious disease-related chemogenomics [14].

Objective: To compare the detection performance of mNGS against standard culture and Sanger sequencing for identifying pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and sputum samples from patients with Lower Respiratory Tract Infections (LRTI) [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Sample Types: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and sputum samples.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit: (Specific kit not named in the study).

- Library Prep Kit: Respiratory Pathogen Multiplex Detection Kit (Vision Medicals, Inc.).

- Sequencing Platform: VisionSeq 1000 sequencing platform (Vision Medicals, Inc.).

- Bioinformatics Software: IDseqTM-2 automated bioinformatic analysis (Vision Medicals, Inc.).

- Culture Media: Blood agar, chocolate agar, McConkey agar, CHROMagar Candida, and Sabouraud agar.

- Identification Instrument: MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Autof MS1000) for culture isolate identification.

- Sanger Sequencing Service: Outsourced to Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. [14].

Methodology:

- Sample Collection and Processing: 184 BALF and 322 sputum samples were collected according to standardized clinical operating procedures [14].

- Standard Microbiological Culture: Specimens were inoculated on the specified culture media. Isolates from positive cultures were identified using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry [14].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA was extracted from all collected samples. The extracted nucleic acid was divided into two portions: one for Sanger sequencing and one for mNGS [14].

- Sanger Sequencing: Each sample was individually amplified using PCR with specific primers for target pathogens. The PCR products were purified and sequenced by a commercial service provider. The resulting sequences were aligned using the NCBI BLAST program [14].

- mNGS Library Preparation and Sequencing: The DNA library was constructed using the Respiratory Pathogen Multiplex Detection Kit, involving fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and amplification. High-throughput sequencing was performed on the VisionSeq 1000 platform [14].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing data were compared against a pathogen database using the automated IDseqTM-2 software. Positive thresholds were set as follows: for certain pathogens like Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Aspergillus fumigatus, an RPM (Reads Per Million) ≥ 0.1 was used; for other microorganisms, the threshold was RPM ≥ 1 [14].

- Discrepant Analysis: Culture and Sanger sequencing were used as reference methods to resolve discrepancies in mNGS findings [14].

Key Results and Conclusions:

- mNGS demonstrated a significant advantage in detecting co-infections, identifying them in 66 BALF samples, compared to 64 by Sanger sequencing and only 22 by culture [14].

- For common bacterial pathogens, conventional culture methods were sufficient. However, mNGS provided a more comprehensive profile and was particularly useful for identifying rare and difficult-to-culture pathogens [14].

- The study concluded that mNGS is a powerful supplementary tool but may not be necessary as a first-line test for all common LRTI pathogens [14].

Decision Pathway for Sequencing Technology Selection

The following flowchart provides a logical framework for choosing between Sanger and NGS sequencing in a validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of an NGS experiment for chemogenomic validation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from diverse sample types (tissue, cells, BALF). | Purity and integrity of input material are critical for library complexity and data quality. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA/RNA and ligate platform-specific adapters and barcodes. | Choice depends on application (e.g., whole genome, exome, RNA-Seq) and required insert size. |

| Sequenceing Kits | Provide the enzymes and nucleotides required for the sequencing-by-synthesis reaction. | Specific to the sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina SBS, Ion Torrent semiconductor). |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess nucleic acid quality (Bioanalyzer) and quantify library concentration (qPCR). | Essential for ensuring uniform loading on the sequencer and avoiding failed runs. |

| Bioinformatics Software | For base calling, read alignment, variant calling, and annotation. | Open-source (BWA, GATK) or commercial solutions require significant computational expertise. |

The selection between NGS and Sanger sequencing for validating chemogenomic hits is not a matter of declaring one technology superior, but of aligning the tool's strengths with the project's goals. Sanger sequencing remains the undisputed gold standard for accuracy and is ideal for the final confirmation of a limited number of specific genetic alterations. However, the massively parallel power of NGS provides an unparalleled capacity for broad discovery, offering a comprehensive, high-throughput, and cost-effective solution for profiling hundreds to thousands of hits across the entire genome or transcriptome. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, with ongoing developments in XLEAP-SBS chemistry and patterned flow cell technology driving further improvements in fidelity, speed, and throughput [9], their role as the cornerstone of large-scale genomic validation in chemogenomics and drug development will only become more firmly established.

The fundamental architecture of a DNA sequencing technology dictates its application in scientific research. For validating hits in chemogenomic screens—where the interaction between thousands of chemical compounds and genetic perturbations is tested—choosing the correct sequencing architecture is paramount. Sanger sequencing, developed in 1977, operates on a single-fragment, chain-termination principle [15] [3]. In contrast, Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is a fundamentally different, massively parallel architecture capable of simultaneously sequencing millions of DNA fragments [4] [16]. This article provides a structured comparison of these architectures, focusing on throughput, read length, and data output, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal tool for confirming the targets and mechanisms of action of bioactive compounds identified in high-throughput chemogenomic screens.

Core Architectural Specifications

The following table summarizes the fundamental performance differences between Sanger and NGS architectures, which directly influence their suitability for various stages of chemogenomic research.

Table 1: Architectural and Performance Comparison of Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Capillary electrophoresis of chain-terminated fragments [17] [3] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis) [4] [16] |

| Throughput | Sequences a single DNA fragment per run [4] | Sequences millions of fragments simultaneously per run [4] [16] |

| Maximum Output per Run | ~1.5 Kilobases per reaction [3] | Up to 16 Terabases (NovaSeq X) [18] |

| Typical Read Length | 500 - 1000 base pairs [15] [18] [16] | Short-Read: 50 - 600 bp; Long-Read: 15,000 - 2,300,000+ bp [18] [16] |

| Key Quantitative Strength | High accuracy for single fragments; cost-effective for ≤ 20 targets [4] | Superior sensitivity for low-frequency variants (~1%); high throughput for >20 targets [4] [17] |

| Primary Limitation | Low throughput and scalability; not cost-effective for many targets [4] [17] | Complex data analysis; potential for sequencing artifacts [17] [3] |

Experimental Data and Protocol for Orthogonal Validation

A critical application in genomics is the orthogonal validation of variants, where one sequencing method is used to verify results from another. The following experiment demonstrates this process.

Experimental Protocol: Large-Scale Sanger Validation of NGS Variants

- Objective: To systematically evaluate the utility of Sanger sequencing for validating variants called from next-generation exome sequencing [19].

- Sample Preparation: DNA was isolated from whole blood from 684 participants in the ClinSeq cohort using a salting-out method followed by phenol-chloroform extraction [19].

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Solution-hybridization exome capture was performed using SureSelect (Agilent) or TruSeq (Illumina) systems. Sequencing was conducted on Illumina GAIIx or HiSeq 2000 platforms. Reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genome, and variants were called using the Most Probable Genotype (MPG) caller [19].

- Sanger Sequencing: A subset of genes was sequenced using 16,371 primer pairs. PCR and sequencing primers were designed using PrimerTile to avoid common variants. Amplicons were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer. All bases with a Phred quality score ≥ Q20 were aligned in Consed, and genotypes were manually verified [19].

- Data Analysis: Variants from exome data were compared against Sanger sequencing data. NGS variants that Sanger failed to validate were re-tested with the original primers and with newly designed, manually-optimized primers [19].

Key Experimental Findings

The large-scale comparison yielded decisive results on validation efficacy [19]:

- Validation Rate: Of over 5,800 NGS-derived variants, only 19 were not initially validated by Sanger sequencing.

- Confirmation of NGS Accuracy: Upon re-sequencing with newly designed primers, 17 of the 19 discordant variants were confirmed, meaning the NGS calls were correct and the initial Sanger had failed.

- Final Calculated Accuracy: The measured validation rate for NGS variants using Sanger sequencing was 99.965%.

- Conclusion: The study concluded that a single round of Sanger sequencing is more likely to incorrectly refute a true positive NGS variant than to correctly identify a false positive. This finding challenges the dogma that Sanger validation is a necessary step for all NGS-derived variants [19].

Workflow and Data Analysis Pathways

The contrasting architectures of Sanger and NGS necessitate different experimental and computational workflows, especially in the context of processing samples from chemogenomic screens.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of sequencing-based validation requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for the workflows described.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing-Based Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Primers | Unique nucleotide sequences added to PCR primers to label amplicons from different samples or reactions, enabling multiplexing [20]. | Critical for NGS workflows, allowing pools of candidate genes from a chemogenomic screen to be sequenced together. |

| Chain-Terminating ddNTPs | Dideoxynucleotide triphosphates halt DNA strand elongation during synthesis, generating fragments of specific lengths for base calling [17] [3]. | The core reagent in Sanger sequencing. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Commercial kits that provide optimized reagents for fragmenting DNA, attaching adapters, and amplifying libraries for sequencing [16]. | Essential for preparing diverse sample types (e.g., genomic DNA from yeast knockouts) for NGS. |

| Polymerases with High Fidelity | DNA polymerases with strong proofreading activity (3'→5' exonuclease) to minimize errors introduced during PCR amplification [15]. | Crucial for both Sanger and NGS library prep to ensure sequence accuracy, especially for low-frequency variant detection. |

| Platform-Specific Sequencing Kits | Kits containing the specialized enzymes, buffers, and fluorescent or unlabeled nucleotides required for a specific sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina SBS, ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit) [16] [20]. | Required to run the sequencing reaction on instruments like Illumina, PacBio, or Nanopore systems. |

The architectural chasm between Sanger sequencing and NGS creates a clear division of labor in chemogenomics and drug target validation. Sanger sequencing remains the champion for targeted, low-throughput confirmation—ideal for verifying a handful of critical mutations or genetic edits in candidate hits with utmost accuracy and minimal bioinformatic overhead [4] [15] [3]. Conversely, NGS is the undisputed choice for comprehensive, high-throughput analysis—capable of re-screening entire gene networks affected by a compound, detecting rare resistant subpopulations, and uncovering novel off-target effects with its massive scale and superior sensitivity [4] [21] [16]. The modern research strategy leverages both: using NGS as a discovery engine to generate hypotheses from genome-wide chemogenomic fitness signatures, and deploying Sanger as a precise validation tool to confirm key findings, thus creating a powerful, iterative cycle for target identification and validation.

The transition from Sanger sequencing to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a paradigm shift in chemogenomic hit validation, moving from single-gene interrogation to massively parallel analysis. While Sanger sequencing remains the historical gold standard for validating genetic variants with its high single-base accuracy, NGS technologies now offer unprecedented throughput for profiling hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously [4]. This expansion in capability necessitates equally rigorous validation frameworks to ensure data reliability for critical drug development decisions. Establishing robust performance metrics—particularly accuracy, sensitivity, and limit of detection (LOD)—forms the foundational requirement for implementing NGS in chemogenomics research. These metrics provide the quantitative basis for comparing technological platforms and ensure that variant calls meet the stringent requirements for downstream functional studies and therapeutic targeting.

The analytical validation of NGS assays has increased in complexity due to sample type variability, stringent quality control criteria, intricate library preparation, and evolving bioinformatics tools [22]. For clinical and public health laboratories implementing NGS, this complexity is further governed by regulatory environments such as the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) [22]. Consequently, systematic validation approaches have emerged to address these challenges, enabling researchers to confidently deploy NGS for comprehensive chemogenomic hit validation while understanding the specific performance characteristics where each technology excels.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Sequencing Technologies

The analytical performance of sequencing technologies can be objectively compared through key metrics that directly impact their utility in chemogenomic hit validation. The following table summarizes the characteristic performance profiles of Sanger sequencing, targeted NGS, and emerging third-generation sequencing exemplified by Oxford Nanopore technology.

Table 1: Performance Metrics Comparison Across Sequencing Platforms

| Performance Metric | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS | Nanopore Technology (MinION) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Method | Chain termination with capillary electrophoresis | Massively parallel sequencing | Nanopore sequencing |

| Theoretical Sensitivity (VAF) | 15–20% [4] | 1% [4] | <1% [8] |

| Single-Read Accuracy | >99.9% [15] | >99.9% [8] | >99% (with error correction) [8] |

| Limit of Detection (VAF) | ~15–20% [4] | 2.9–5% (validated) [23] | Comparable to NGS [8] |

| Read Length | 400–900 base pairs [8] | 50–500 base pairs [8] | Up to megabase scales [8] |

| Error Profile | Low error rate (0.001%) [8] | 0.1–1% [8] | ~5% (platform-specific) [8] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Single fragment per reaction | Millions of fragments simultaneously [4] | Thousands of reads per flow cell |

| Key Applications in Validation | Single gene confirmation, orthogonal validation | Multi-gene panels, novel variant discovery | Rapid screening, complex regions |

The sensitivity advantage of NGS is particularly significant for chemogenomics applications where detecting low-frequency variants is critical. While Sanger sequencing has a limit of detection of approximately 15-20% variant allele frequency (VAF), targeted NGS can reliably detect variants at 1% VAF or lower [4]. This enhanced sensitivity enables researchers to identify subclonal populations in heterogeneous samples—a common scenario in cancer research and microbial resistance studies. Recent validation studies of pan-cancer NGS panels have demonstrated the ability to detect single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (Indels) at allele frequencies as low as 2.9% with high sensitivity (98.23%) and specificity (99.99%) [23]. For liquid biopsy applications, where detecting circulating tumor DNA requires exceptional sensitivity, specialized NGS assays have achieved 96.92% sensitivity and 99.67% specificity for SNVs/Indels at 0.5% allele frequency [24].

Experimental Protocols for Analytical Validation

Determining Accuracy Through Orthogonal Verification

Accuracy validation establishes how well NGS variant calls correspond to the true genetic variation present in a sample. The established protocol involves comparing NGS results with an orthogonal method, typically Sanger sequencing. A comprehensive approach includes:

Sample Selection and Preparation: Select a representative set of 50-100 samples encompassing various variant types (SNVs, Indels), allelic frequencies, and genomic contexts (GC-rich regions, repetitive elements) [25]. Extract DNA using standardized methods (e.g., salting-out with phenol-chloroform extraction) and quantify using fluorometric methods to ensure accurate input amounts [19].

NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing: For targeted NGS, employ hybrid capture or amplicon-based approaches (e.g., Haloplex/SureSelect) covering the genes of interest. For a 61-gene oncopanel, library preparation can be performed using hybridization-capture with library kits compatible with automated systems to reduce human error and contamination risk [23]. Sequence on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq or MGI DNBSEQ-G50RS to achieve a minimum median coverage of 469×–2320× across the target regions [23].

Variant Calling and Filtering: Process raw sequencing data through a bioinformatics pipeline including:

- Quality control (FastQC)

- Adapter trimming (Surecall Trimmer)

- Alignment to reference genome (BWA-MEM, NovoAlign)

- Variant calling (GATK HaplotypeCaller) Apply minimum quality filters such as Phred quality score (Q) ≥30, minimum coverage depth of 30×, and allele balance >0.2 [25].

Sanger Sequencing Validation: Design PCR primers flanking the target variants using Primer3, avoiding SNPs in primer-binding sites [25]. Amplify target regions using optimized PCR conditions (e.g., FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase), purify amplicons, and perform Sanger sequencing with both forward and reverse primers. Analyze sequences using software such as Sequencher with manual review of fluorescence peaks [19].

Concordance Analysis: Calculate accuracy as the percentage of NGS variants confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Large-scale studies have demonstrated 99.72%–99.965% concordance rates between NGS and Sanger sequencing for high-quality variants [26] [19]. Establish quality score thresholds (e.g., QUAL ≥100, depth ≥20×, allele frequency ≥0.25) to define "high-quality" variants that may not require orthogonal confirmation [26].

Establishing Sensitivity and Limit of Detection

Sensitivity validation determines the lowest variant allele frequency that can be reliably detected, defining the assay's limit of detection (LOD). The procedural steps include:

Reference Material Titration: Use commercially available reference standards (e.g., HD701) with known variants at predetermined allele frequencies. Titrate DNA input from 10-100 ng to determine the minimum input requirement, with ≥50 ng typically needed for reliable detection [23].

Variant Dilution Series: Create a dilution series of mutant DNA in wild-type DNA to simulate variants across a range of allele frequencies (e.g., 10%, 5%, 2.5%, 1%, 0.5%). For each dilution point, perform library preparation and sequencing in replicates (n≥3) [23].

Data Analysis and LOD Determination: Process sequencing data through the standard bioinformatics pipeline. Calculate sensitivity as: [True Positives/(True Positives + False Negatives)] × 100. Plot detection rate against variant allele frequency to determine the LOD, defined as the lowest VAF where ≥95% of expected variants are detected. Studies have established LODs of 2.9% VAF for both SNVs and Indels in targeted NGS panels [23].

Precision Assessment: Evaluate repeatability (intra-run precision) by sequencing the same sample with different barcodes within a single run. Assess reproducibility (inter-run precision) by sequencing the same sample across different runs, operators, and instruments. High-quality NGS assays demonstrate ≥99.99% repeatability and ≥99.98% reproducibility [23].

Figure 1: Limit of Detection (LOD) Validation Workflow. The process involves creating a dilution series of reference materials, sequencing replicates, and determining the lowest variant allele frequency (VAF) with consistent detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS validation protocols requires specific reagents and platforms designed to ensure reproducibility and accuracy. The following table outlines essential solutions for establishing robust NGS validation workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Capture Kits (SureSelect, TruSeq) | Target enrichment for specific gene panels | Enables focused sequencing of chemogenomic targets; provides uniform coverage [25] [23] |

| Automated DNA Extraction (QIAsymphony) | Standardized nucleic acid purification | Reduces manual variability; ensures consistent input quality with A260/A280 quality control [27] |

| Reference Standards (HD701) | Accuracy and LOD determination | Provides known variants at defined frequencies for assay calibration [23] |

| Library Prep Robotics (MGI SP-100RS) | Automated library preparation | Minimizes human error, contamination risk; improves inter-run reproducibility [23] |

| NGS Benchtop Sequencers (MiSeq, DNBSEQ-G50) | Accessible in-house sequencing | Enables rapid turnaround times (4 days) compared to outsourcing (3 weeks) [23] |

| Bioinformatics Tools (GATK, Sophia DDM) | Variant calling and quality control | Provides machine learning-based variant filtering; connects molecular profiles to clinical insights [23] |

The quantitative comparison of accuracy, sensitivity, and limit of detection provides a rigorous framework for selecting appropriate sequencing technologies for chemogenomic hit validation. While Sanger sequencing maintains utility for low-throughput confirmation of single variants, targeted NGS offers superior performance for comprehensive profiling where detection of low-frequency variants is essential. The experimental protocols outlined enable researchers to establish validated NGS workflows that meet the stringent requirements of drug development research. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, with platforms such as Oxford Nanopore offering rapid turnaround times and long-read capabilities, the fundamental validation metrics remain essential for ensuring data quality and reliability. By implementing these standardized validation approaches, research teams can confidently leverage NGS technologies to accelerate chemogenomic discovery while maintaining the analytical rigor required for translational applications.

Building Your Validation Workflow: Strategic Application of Sanger and NGS

Ideal Use Cases for Sanger Sequencing in Hit Confirmation

In the era of high-throughput genomics, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomic screening by enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions of DNA fragments. However, when research progresses from hit discovery to targeted validation, Sanger sequencing emerges as an indispensable tool for confirming critical genetic findings. Despite its lower throughput, Sanger sequencing provides superior accuracy for analyzing small targeted regions, making it the gold standard for orthogonal validation of NGS-derived variants [4] [28]. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of Sanger sequencing and NGS for validating chemogenomic hits, providing researchers with evidence-based criteria for selecting the appropriate technology at each stage of their experimental workflow.

Technical Performance Comparison

The selection between Sanger sequencing and NGS requires understanding their fundamental technical differences. While both methods utilize DNA polymerase to incorporate nucleotides, their approaches to sequencing and applications in hit confirmation differ significantly.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | >99.999% (Error rate: ~0.001%) [29] [12] | ~99.9% (Error rate: 0.1-1%) [12] |

| Throughput | Single DNA fragment per reaction [4] | Millions of fragments simultaneously [4] |

| Read Length | 500-1000 bp [30] [28] [31] | 150-300 bp (Illumina) [29] [31] |

| Detection Limit | ~15-20% variant frequency [4] [29] | As low as 1% variant frequency [4] |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Optimal for 1-20 targets [4] | Cost-prohibitive for low target numbers [4] [31] |

| Sample Multiplexing | Limited | High capacity [4] |

| Data Analysis | Minimal bioinformatics required [29] | Advanced bioinformatics essential [29] |

Table 2: Experimental Validation Success Rates

| Study Context | Validation Rate | Sample Size | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing Variants [26] | 99.72% | 1,756 variants | 100% concordance for high-quality variants (QUAL ≥100, DP ≥20, AF ≥0.2) |

| ClinSeq Cohort [19] | 99.965% | ~5,800 variants | Single-round Sanger validation incorrectly refuted true positives more often than identifying false positives |

| Clinical Pipeline Validation [25] | ~100% | 945 validated variants | Discrepancies often resulted from allelic dropout in Sanger method, not NGS errors |

When to Use Sanger Sequencing for Hit Confirmation

Specific Application Scenarios

Sanger sequencing provides maximum utility in targeted confirmation scenarios where its exceptional accuracy and straightforward interpretation offer distinct advantages over NGS approaches.

Orthogonal Validation of NGS-Derived Variants: Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for confirming variants identified through NGS, particularly for clinically significant or publication-bound results [28] [19]. Current guidelines from organizations like the ACMG recommend orthogonal validation for clinical reporting, though this requirement is being reevaluated as NGS quality improves [26]. Research demonstrates that high-quality NGS variants (with appropriate quality thresholds) show 99.72-100% concordance with Sanger validation [26] [19]. However, Sanger confirmation is particularly valuable for variants in challenging genomic regions or those with borderline quality metrics.

Analysis of Small Gene Targets: When investigating 1-20 specific genomic targets, Sanger sequencing provides superior cost-effectiveness and workflow efficiency compared to NGS [4] [31]. The established protocols and minimal sample preparation requirements make it ideal for focused studies where multiplexing provides no advantage. This is especially relevant for confirming specific chemogenomic hits in candidate genes without the overhead of NGS library preparation and complex bioinformatics analysis.

Testing for Known Familial Variants: For targeted investigation of specific sequence variants—such as known pathogenic mutations or engineered alterations—Sanger sequencing offers precise and flexible analysis [30]. This application is common in clinical settings for conditions like BRCA1-related breast cancer risk or cystic fibrosis carrier testing, where only specific nucleotides require interrogation [30] [28]. The method's ability to generate long, continuous reads (up to 1,000 bp) provides context for variant interpretation [30].

Verification of Cloned Constructs and Plasmids: Sanger sequencing is the preferred method for verifying cloned inserts, plasmid sequences, and genetic engineering outcomes [28] [31]. Its long read capabilities are particularly valuable for confirming sequences with repetitive elements, secondary structures, or high GC content that challenge short-read NGS technologies [31]. Specialized Sanger protocols have been developed for challenging sequences like AAV inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) [31].

Decision Workflow for Sequencing Technology Selection in Hit Confirmation

Experimental Design and Protocols

Sanger Sequencing Validation Workflow

A standardized protocol ensures reliable Sanger sequencing results for confirming chemogenomic hits. The process begins with PCR amplification of the target region from genomic DNA or cloned constructs, using primers designed to flank the variant of interest [25] [28]. The sequencing reaction then utilizes a mixture of standard dNTPs and fluorescently labeled ddNTPs (chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides), DNA polymerase, and the same primer used for PCR amplification [28] [31]. Following thermal cycling, the products are purified to remove unincorporated nucleotides and subjected to capillary electrophoresis, which separates DNA fragments by size [30] [28]. The final output is a chromatogram displaying fluorescence peaks corresponding to the nucleotide sequence, allowing both automated base calling and visual inspection [31].

Sanger Sequencing Experimental Workflow for Hit Confirmation

Protocol for Validating NGS-Derived Variants

To confirm NGS-identified variants using Sanger sequencing:

Primer Design: Design oligonucleotide primers flanking the variant using tools like Primer3 [25]. Amplicons should be 500-700 bp for optimal results [31]. Verify that primers do not bind to regions with known polymorphisms that could cause allelic dropout [25].

PCR Amplification: Amplify the target region using 50-100 ng of genomic DNA, standard PCR reagents, and thermostable DNA polymerase [25]. Use touchdown PCR or optimized annealing temperatures for specific amplification.

Sequencing Reaction: Prepare reactions using BigDye Terminator kits or similar systems according to manufacturer protocols [25] [19]. Include both forward and reverse primers for bidirectional sequencing.

Cleanup and Electrophoresis: Remove unincorporated dyes using column purification or enzymatic cleanup [25]. Perform capillary electrophoresis on ABI 3500 or similar platforms [25].

Data Analysis: Examine chromatograms using software such as SnapGene Viewer or FinchTV [31]. Manually verify variants, especially near primer-binding sites and in regions with complex signatures [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sanger Sequencing

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| BigDye Terminator v3.1 [25] [19] | Fluorescent dideoxy terminator sequencing | Ready reaction mix containing dye-terminators, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer |

| ABI 3500 Series Genetic Analyzers [25] | Capillary electrophoresis platform | 8-96 capillary configurations; detects 4-color fluorescence |

| FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase [25] | PCR amplification of targets | Thermostable polymerase for specific amplification of template regions |

| Exonuclease I/FastAP [25] | PCR product purification | Enzyme mixture to degrade excess primers and dNTPs before sequencing |

| Primer3 Software [25] | Primer design algorithm | Open-source tool for designing Sanger sequencing primers with optimal parameters |

Sanger sequencing maintains a critical role in hit confirmation workflows despite the proliferation of NGS technologies. Its exceptional accuracy, long read capabilities, and minimal bioinformatics requirements make it ideally suited for orthogonal validation of NGS findings, analysis of limited targets, and verification of cloned constructs. By understanding the specific use cases where Sanger sequencing provides maximal advantage—particularly when working with 1-20 targets or requiring gold-standard validation—researchers can effectively integrate both technologies into robust hit confirmation pipelines. As NGS quality continues to improve, the requirement for Sanger validation may diminish for high-quality variants, but its position as the accuracy benchmark remains unchallenged in molecular diagnostics and critical research applications.

Leveraging NGS for Comprehensive Variant Discovery and Rare Allele Detection

In the field of chemogenomics research, where identifying genetic variants linked to compound sensitivity is paramount, the choice of sequencing technology directly impacts discovery potential. For decades, Sanger sequencing has served as the undisputed gold standard for DNA sequence validation, providing high-quality data for limited targets. However, the emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed this landscape, enabling researchers to move from targeted interrogation to comprehensive variant discovery. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of NGS against Sanger sequencing specifically for validating chemogenomic hits, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform platform selection for drug development professionals. The critical distinction lies in sequencing volume: while Sanger sequences a single DNA fragment at a time, NGS is massively parallel, sequencing millions of fragments simultaneously per run [4]. This fundamental difference in throughput creates a paradigm shift from validating known hits to discovering novel variants and rare alleles across extensive genomic regions.

Technology Comparison: NGS vs. Sanger Sequencing

Performance Characteristics and Capabilities

The following table summarizes the key technical differences between Sanger sequencing and NGS relevant to chemogenomics research:

Table 1: Performance comparison between Sanger sequencing and NGS

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Volume | Single DNA fragment per reaction [4] | Millions of fragments simultaneously (massively parallel) [4] |

| Detection Limit (Variant Allele Frequency) | ~15-20% [4] [31] | As low as 0.3%-1% with standard protocols; down to 0.125% with advanced error correction [32] [33] |

| Discovery Power | Low; best for known variants [4] | High; identifies novel variants across targeted regions [4] |

| Mutation Resolution | Limited to targeted size variants | Identifies variants from single nucleotides to large chromosomal rearrangements [4] |

| Typical Read Length | 500-700 bp [31] | 150-300 bp (Illumina) [31] |

| Cost Efficiency | Cost-effective for 1-20 targets [4] | Cost-effective for larger target numbers (>20 targets) [4] |

| Throughput | Low throughput [31] | High throughput for many samples [4] |

| Quantitative Capability | Not quantitative; mixed peaks become uninterpretable [34] | Quantitative via read counts [34] |

Application in Chemogenomic Research

For chemogenomic studies aiming to validate hits against a limited number of predefined genetic targets (e.g., specific mutations in kinase domains), Sanger sequencing remains a reliable and cost-effective option, particularly when working with fewer than 20 targets [4]. Its established workflow and straightforward data interpretation require less specialized bioinformatics support, making it accessible for routine validation.

In contrast, NGS provides distinct advantages for more comprehensive variant discovery applications. Its higher sensitivity enables detection of low-frequency variants present in heterogeneous samples (e.g., compound-resistant subpopulations in cell pools) [4] [35]. The technology's massively parallel nature allows researchers to screen hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously, making it indispensable for genome-wide association studies or pathway-focused chemogenomic screens [4]. Furthermore, NGS provides both qualitative and quantitative data, combining sequence information with allele frequency quantification—critical for understanding clonal dynamics in response to compound treatment [34].

Experimental Data and Validation

Accuracy and Validation Studies

Recent large-scale studies have systematically evaluated the accuracy of NGS-detected variants, with profound implications for validation workflows in research settings. A comprehensive analysis of 1,756 whole-genome sequencing (WGS) variants validated by Sanger sequencing demonstrated 99.72% concordance between the technologies [26]. This remarkably high agreement challenges the long-standing requirement for orthogonal Sanger validation of all NGS findings.

Further evidence comes from the ClinSeq project, which compared NGS variants against high-throughput Sanger sequencing across 684 participants. From over 5,800 NGS-derived variants analyzed, only 19 were not initially validated by Sanger data. Upon re-examination, 17 of these were confirmed as true positives using optimized sequencing primers, while the remaining two variants had low quality scores from exome sequencing [19]. This resulted in an overall validation rate of 99.965% for NGS variants, leading the authors to conclude that "validation of NGS-derived variants using Sanger sequencing has limited utility, and best practice standards should not include routine orthogonal Sanger validation of NGS variants" [19].

Quality Thresholds for High-Confidence Variants

Research has identified specific quality metrics that can reliably distinguish high-confidence NGS variants requiring no orthogonal validation. For whole-genome sequencing data, applying caller-agnostic thresholds of depth of coverage (DP) ≥ 15x and allele frequency (AF) ≥ 0.25 successfully identified all true positive variants while drastically reducing the number requiring Sanger confirmation to just 4.8% of the initial variant set [26]. When using caller-dependent quality scores (QUAL ≥ 100 with HaplotypeCaller), this proportion was further reduced to 1.2% of the initial variant set [26].

Table 2: Experimental validation rates for NGS variants compared to Sanger sequencing

| Study | Sample Size | Variant Types | Concordance Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGS Validation [26] | 1,756 variants from 1,150 patients | SNVs, INDELs | 99.72% | Caller-agnostic thresholds (DP≥15, AF≥0.25) enable reliable variant filtering |

| ClinSeq Project [19] | 684 participants; >5,800 variants | SNVs, INDELs | 99.965% | Single round of Sanger validation more likely to incorrectly refute true NGS variants |

| PAN100 Panel [32] | 27 patients across 8 cancer types | SNVs, INDELs | 73.1%-80.0% PPA* | High concordance between ctDNA and tissue NGS supports liquid biopsy applications |

*PPA: Positive Percent Agreement between ctDNA and tissue NGS

Advanced NGS Methodologies for Rare Allele Detection

Error Correction Strategies

A significant limitation of conventional NGS for rare allele detection is the inherent error rate of approximately 0.1-1%, which creates background noise that can obscure genuine low-frequency variants [35]. This is particularly problematic for chemogenomics applications detecting rare resistant clones in heterogeneous cell populations. To address this challenge, several advanced error-correction methodologies have been developed:

Molecular Barcoding (UIDs): Unique identifiers are ligated to individual DNA molecules before amplification and sequencing, enabling bioinformatic grouping of reads derived from the original molecule and generating consensus sequences to eliminate random errors [35] [33].

Single Molecule Consensus Sequencing: Methods such as Duplex Sequencing achieve exceptional accuracy by tracking both strands of individual DNA molecules, reducing error rates to approximately 1×10⁻⁷ [35].

Computational Artifact Reduction: Bioinformatics tools like MuTect and VarScan2 employ sophisticated filters to exclude technical artifacts based on mapping quality, sequence context, and positional biases [35].

Specialized Protocols for Ultrasensitive Detection

Recent methodological advances have further enhanced the sensitivity of NGS for rare variant detection. The SPIDER-seq (Sensitive genotyping method based on a peer-to-peer network-derived identifier for error reduction in amplicon sequencing) protocol demonstrates how molecular barcoding can be adapted to PCR-based libraries, enabling detection of mutations at frequencies as low as 0.125% with high accuracy and reproducibility [33]. This approach constructs peer-to-peer networks of daughter molecules derived from original DNA strands, creating cluster identifiers (CIDs) that allow accurate consensus generation even when barcodes are overwritten during PCR amplification [33].

For comprehensive genomic analysis, integrated platforms like DRAGEN utilize pangenome references, hardware acceleration, and machine learning-based variant detection to identify all variant types—including single-nucleotide variations (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), short tandem repeats (STRs), structural variations (SVs), and copy number variations (CNVs)—in approximately 30 minutes of computation time from raw reads to variant detection [36]. This unified approach enables researchers to obtain a complete variant profile from chemogenomic screens without needing multiple specialized assays.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Recommended Workflows for Chemogenomic Applications

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for leveraging NGS in chemogenomic variant discovery, from sample preparation to data analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for NGS-based variant discovery

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep | Fragmentation, end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina TruSight Oncology, Agilent SureSelect | Hybridization-based capture of gene panels or whole exome |

| Molecular Barcoding Reagents | IDT Unique Dual Indexes | Sample multiplexing and identification |

| Error Reduction Chemistry | SPIDER-seq components [33] | Molecular barcoding for rare allele detection |

| PCR Enzymes | KAPA HiFi Polymerase [33] | High-fidelity amplification for library construction |

| Sequence Capture Beads | Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads | Recovery of biotinylated target sequences |

| Quality Control Assays | Agilent Bioanalyzer, qPCR assays | Library quantification and quality assessment |

| Analysis Software | DRAGEN [36], GATK, GAIAGEN Analyze | Variant calling, filtering, and annotation |

The comprehensive comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that NGS technologies have matured to a point where they offer distinct advantages over Sanger sequencing for comprehensive variant discovery and rare allele detection in chemogenomics research. While Sanger sequencing remains suitable for limited target validation, NGS provides superior discovery power, sensitivity, and throughput for genome-scale investigations. The experimental data showing >99.7% concordance between NGS and Sanger sequencing supports a paradigm shift toward reducing routine orthogonal validation, particularly for variants meeting established quality thresholds.

Future directions in NGS-based variant discovery will likely focus on further enhancing detection sensitivity through improved error-correction methods, reducing turnaround times via integrated analysis platforms, and decreasing costs to enable larger-scale chemogenomic screens. As these trends continue, NGS is poised to become the primary technology for both discovery and validation in advanced chemogenomics research, ultimately accelerating the identification of genetic determinants of compound sensitivity and resistance in drug development pipelines.

In the field of chemogenomic research, the identification of true-positive genetic variants from high-throughput screens is a critical step in target validation and drug discovery. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our ability to screen thousands of genetic targets simultaneously, offering unprecedented scale and discovery power [4]. However, this massive screening power necessitates a robust validation strategy to confirm putative hits before investing resources in downstream functional studies. While Sanger sequencing has long been considered the "gold standard" for variant confirmation, its application across all NGS findings is often impractical, costly, and time-consuming [19] [37].

A tiered validation strategy effectively leverages the strengths of both technologies: utilizing NGS for broad, unbiased screening of chemogenomic hits, followed by targeted Sanger verification of the most promising candidates. This approach balances comprehensive discovery with rigorous confirmation, ensuring research integrity while optimizing resource allocation. The evolution of NGS accuracy has prompted a reevaluation of when orthogonal Sanger validation is truly necessary, with recent studies demonstrating that high-quality NGS variants can achieve validation rates exceeding 99.9% [19] [26]. This guide provides a structured framework for designing an efficient validation workflow, supported by experimental data and practical protocols for implementation in drug discovery pipelines.

Technological Comparison: Understanding the Fundamental Differences

The design of an effective validation strategy begins with understanding the complementary technical profiles of NGS and Sanger sequencing technologies. Each method possesses distinct advantages that can be strategically leveraged at different stages of the hit validation process.

Key Characteristics and Capabilities

Table 1: Comparison of Sanger Sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination using ddNTPs [1] [31] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis) [1] [38] |

| Throughput | Low to medium (individual samples or small batches) [1] | Extremely high (entire genomes, exomes, or multiple samples multiplexed) [1] [38] |

| Read Length | Long reads (500–1,000 bp) [1] [31] | Short reads (50-300 bp for Illumina; varies by platform) [1] [31] |

| Detection Sensitivity | ~15-20% limit of detection [4] [31] | Down to 1% for low-frequency variants [4] |

| Cost Efficiency | Cost-effective for 1-20 targets; high cost per base [4] [1] | Low cost per base; cost-effective for large target numbers [4] [1] |

| Data Analysis | Simple; requires basic alignment software [1] | Complex; requires sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines [1] [38] |

| Primary Applications | Targeted confirmation, single-gene variant analysis, plasmid validation [1] [31] | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, epigenetics, clinical oncology [1] |

Visualizing the Sequencing Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental methodological differences between Sanger and NGS workflows, highlighting where errors may be introduced and quality control is critical:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data for Decision Making

Empirical data from comparative studies provides the foundation for evidence-based protocol design. The following quantitative comparisons highlight key performance metrics relevant to validation strategy design.

Concordance Rates and Validation Efficiency

Table 2: Experimental Concordance Rates Between NGS and Sanger Sequencing

| Study Context | Sample Size | Concordance Rate | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (PIK3CA) | 186 tumors | 98.4% | 3 mutations missed by Sanger had variant frequencies <10%; NGS detected additional mutations in exons 1, 4, 7, 13 | [39] |

| ClinSeq Cohort | 5,800+ variants | 99.97% | 19 variants not initially validated; 17 confirmed with redesigned primers, 2 had low quality scores | [19] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | 1,756 variants | 99.72% | 5 discordant variants; established quality thresholds to reduce needed validation to 1.2% of variants | [26] |

| HIV Drug Resistance | 10 specimens across 10 labs | 99.6% identity at 20% threshold | NGS sequences using 20% threshold most similar to Sanger consensus | [40] |

| Genetic Diagnosis | 945 validated variants | >99.6% | 3 discrepancies due to allelic dropout in Sanger; highlights Sanger limitations | [37] |

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

The dramatically different detection sensitivities between the two methodologies significantly impact their appropriate applications in validation workflows. NGS demonstrates superior capability for identifying low-frequency variants, with detection limits as low as 1% allele frequency compared to 15-20% for Sanger sequencing [4]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly valuable in chemogenomic research for identifying subclonal populations or detecting variants in heterogeneous samples. However, this same sensitivity can present challenges in clinical interpretation, as the significance of low-frequency variants may be uncertain [40]. For validation of chemogenomic hits, this means that NGS can identify potential variants that would be undetectable by Sanger, but the decision to pursue Sanger confirmation should consider the biological relevance of the variant allele frequency.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Tiered Validation

Implementing a robust tiered validation strategy requires standardized protocols for both NGS screening and subsequent Sanger verification. The following methodologies are adapted from peer-reviewed studies and can be implemented in most molecular biology laboratories.

Targeted NGS Screening Protocol

The following protocol for targeted NGS is adapted from breast cancer mutation studies and can be modified for chemogenomic hit screening [39]:

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract genomic DNA from samples using validated kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit).

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit fluorometer HS DNA Assay).

- Assess DNA quality through spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280 ~1.8-2.0) and fragment analysis.

- Use 10-50 ng of input DNA for library preparation, depending on sample quality.

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment

- Utilize customized sequencing panels targeting relevant genomic regions (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Designer for panel creation).

- Perform multiplex PCR amplification using validated primer sets.

- Incorporate molecular barcodes for sample multiplexing to reduce costs and batch effects.

- Purify amplified products using magnetic bead-based clean-up protocols.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Perform emulsion PCR or bridge amplification for clonal amplification.

- Sequence using appropriate NGS platforms (Illumina MiSeq/Ion PGM) with minimum coverage of 100-200x for variant detection.

- Align sequences to reference genome (hg19/GRCh38) using optimized aligners (BWA-MEM, NovoAlign).

- Call variants using established algorithms (GATK HaplotypeCaller, Torrent Variant Caller) with minimum quality score thresholds.

Sanger Sequencing Verification Protocol

For orthogonal confirmation of NGS-identified variants, this Sanger sequencing protocol provides reliable validation [37]:

Primer Design and Optimization

- Design primers using Primer3 algorithm to generate 300-500 bp amplicons flanking the variant of interest.

- Verify primer specificity using BLAST against reference genome.

- Check for polymorphisms in primer binding sites using dbSNP database.

- Include positive and negative controls in each reaction batch.

PCR Amplification and Purification

- Perform PCR reactions in 25 μL volumes containing:

- 1X PCR buffer

- 1.5-2.5 mM MgCl₂ (optimize per primer pair)

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 0.5 μM forward and reverse primers

- 1.0 U DNA polymerase (e.g., FastStart Taq)

- 10-50 ng template DNA

- Use touchdown PCR cycling conditions for improved specificity when necessary.

- Verify amplification by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Purify PCR products using exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphatase treatment or column-based purification.

- Perform PCR reactions in 25 μL volumes containing:

Sequencing Reaction and Analysis

- Set up sequencing reactions with BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit.

- Use 5-20 ng purified PCR product per 100 bp of sequence length.

- Perform capillary electrophoresis on automated sequencers (e.g., ABI 3130xl).

- Analyze chromatograms using sequence analysis software (e.g., Sequencher).

- Manually inspect variant calls for peak quality, background signal, and heterozygous balance.

The Tiered Validation Framework: Strategic Implementation

A strategic tiered approach to validation maximizes efficiency while maintaining scientific rigor. The following framework categorizes NGS-identified variants based on multiple quality metrics to determine Sanger verification necessity.

Quality Thresholds for Validation Triage

Table 3: Quality Thresholds for Determining Sanger Validation Necessity

| Variant Category | Coverage Depth (DP) | Variant Allele Frequency (AF) | Quality Score (QUAL) | Sanger Validation Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Quality | ≥30x [37] | ≥0.25 [26] | ≥100 [26] | Optional; may proceed without validation |

| Moderate Quality | 20-30x [39] | 0.15-0.25 [39] | 50-100 [26] | Recommended, especially for clinically significant variants |

| Low Quality | <20x [39] | <0.15 [39] | <50 [26] | Required if biologically relevant; otherwise, exclude |

| Complex Regions | Any | Any | Any | Always validate regardless of quality metrics |

Decision Framework for Validation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for implementing a tiered validation approach, incorporating quality metrics and practical considerations:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of a tiered validation strategy requires access to specific laboratory reagents and bioinformatics tools. The following table catalogues essential materials referenced in the experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NGS and Sanger Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from various sample types | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, Tecan Freedom EVO with GeneCatcherTM gDNA Kit [39] [37] |

| DNA Quantification Assays | Accurate measurement of DNA concentration and quality | Qubit fluorometer HS DNA Assay, TapeStation, Nanodrop [39] |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Selection and amplification of genomic regions of interest | Agilent SureSelect, Haloplex, Ion AmpliSeq [39] [37] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries with adapters and barcodes | Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0, Illumina TruSeq [39] [38] |

| Sequencing Kits | Execution of sequencing reactions on respective platforms | Ion OneTouch 200 Template Kit, Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kits [39] [40] |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of specific genomic regions | FastStartTM Taq DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, optimized buffers [37] |

| Sanger Sequencing Kits | Cycle sequencing with fluorescent terminators | BigDye Terminator v3.1, ABI PRISM kits [19] [37] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data analysis, variant calling, and interpretation | GATK, Torrent Suite Software, BWA, NovoAlign [39] [19] [37] |

A strategically designed tiered validation approach effectively leverages the complementary strengths of NGS and Sanger sequencing technologies. By implementing quality-based triage protocols, research teams can significantly reduce unnecessary Sanger verification while maintaining confidence in results. Current evidence supports that high-quality NGS variants with appropriate quality metrics (depth ≥30x, allele frequency ≥0.25, quality score ≥100) may not require orthogonal Sanger validation, potentially reducing verification efforts to less than 5% of identified variants [26]. This optimized workflow accelerates the transition from NGS screening to verified chemogenomic hits, ultimately streamlining the drug discovery pipeline while upholding scientific rigor. As NGS technologies continue to evolve and demonstrate increasingly robust performance, validation strategies should be regularly reevaluated to incorporate emerging evidence and technological advancements.

Choosing the appropriate DNA sequencing method is a critical strategic decision in research and drug development. The choice between Sanger sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is primarily dictated by the project's scale and economic constraints. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these technologies to inform the validation of chemogenomic hits.

Economic and Scale Considerations at a Glance

The core of the cost-benefit analysis lies in aligning the technology's throughput and cost structure with the project's scope. The following table summarizes the key economic differentiators.

Table 1: Key Economic and Operational Factors for Sanger and NGS

| Factor | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|