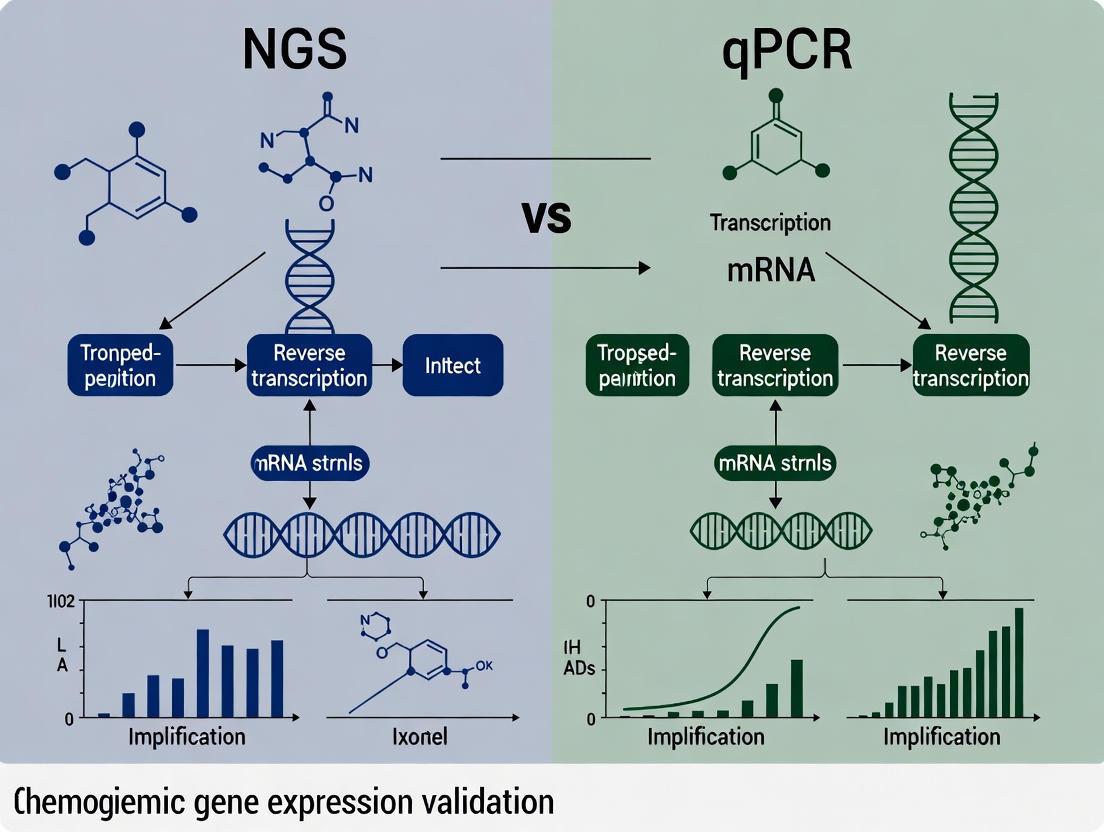

NGS vs qPCR for Gene Expression Validation: A Strategic Guide for Chemogenomics Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression validation in chemogenomics and drug development.

NGS vs qPCR for Gene Expression Validation: A Strategic Guide for Chemogenomics Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression validation in chemogenomics and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of each technology, explores their specific methodological applications from discovery to clinical validation, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a rigorous framework for cross-platform validation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current trends, including multiomics integration and AI-driven analytics, to empower scientists in selecting the optimal validation strategy for their specific research goals, ultimately accelerating the path from genomic data to clinical insight.

Understanding the Core Technologies: NGS and qPCR in the Modern Genomics Era

The advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed the landscape of genomic research, offering unprecedented capabilities for comprehensive genetic analysis. While quantitative PCR (qPCR) has long been the gold standard for targeted gene expression analysis, the limitations of this technology in scope and discovery power have become increasingly apparent in the era of systems biology and personalized medicine. The emergence of NGS technologies represents a paradigm shift from targeted analysis to holistic genomic profiling, enabling researchers to move beyond hypothesis-driven research to discovery-oriented science.

This revolution is particularly evident in chemogenomic research, where understanding complex gene expression responses to chemical compounds requires comprehensive transcriptome assessment. Where qPCR can analyze a predefined set of known sequences, NGS provides a hypothesis-free approach that does not require prior knowledge of sequence information, thereby unlocking novel discovery potential [1]. The ability to simultaneously sequence millions of DNA fragments has made NGS an indispensable tool for researchers seeking to understand complex biological systems, identify novel biomarkers, and develop targeted therapies [2].

This guide provides an objective comparison of NGS and qPCR technologies, focusing on their application in gene expression validation studies. Through experimental data and detailed methodologies, we examine how these technologies perform across critical parameters including sensitivity, specificity, throughput, and discovery power, providing researchers with the evidence needed to select appropriate genomic analysis platforms for their specific applications.

Technology Fundamentals: Core Principles and Capabilities

qPCR: The Established Workhorse

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), particularly in its reverse transcription form (RT-qPCR), has remained the method of choice for targeted gene expression analysis for decades. This technology operates on the principle of amplifying specific DNA sequences using target-specific primers and detecting the amplification products in real-time using fluorescent chemistry. The point at which fluorescence crosses a threshold detection level (Cycle threshold or Cq) provides quantitative information about the initial amount of the target sequence [3] [4]. The widespread adoption of qPCR stems from its strengths: high sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts, excellent reproducibility, relatively low cost per reaction, and straightforward data analysis workflows [5]. The technology is particularly well-suited for validation studies where a limited number of pre-identified targets need to be quantified across multiple samples.

However, qPCR faces significant limitations in the context of comprehensive genomic profiling. The technology can only detect known sequences for which specific primers and probes have been designed, fundamentally limiting its discovery power [1]. Additionally, the multiplexing capacity of qPCR is constrained by spectral overlap of fluorescent dyes, typically allowing simultaneous detection of only a few targets per reaction. This necessitates running multiple reactions for comprehensive profiling, increasing sample requirements, hands-on time, and overall costs when analyzing large gene sets [5].

NGS: The High-Throughput Discovery Platform

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, particularly RNA-Seq for transcriptome analysis, have revolutionized genomic research by enabling massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [2]. Unlike qPCR, NGS is not limited to predetermined targets and can identify both known and novel transcripts through an unbiased approach. This comprehensive profiling capability has made NGS the technology of choice for discovery-phase research where the complete transcriptional landscape needs to be characterized.

The core advantage of NGS lies in its unbiased discovery power and massive throughput. A single NGS experiment can profile thousands of genes across multiple samples, providing both quantitative expression data and information about sequence variations, splice isoforms, fusion transcripts, and novel genes [1]. Furthermore, NGS demonstrates a wider dynamic range for quantifying gene expression without the signal saturation limitations that can affect qPCR [1]. The digital nature of NGS data, where expression is measured by direct counting of sequence reads, provides absolute quantification capabilities that surpass the relative quantification methods typically used in qPCR analysis [1].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Experimental Data

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Both NGS and qPCR offer high sensitivity, though their detection limits differ based on experimental design and application. qPCR is exceptionally sensitive, capable of detecting a few copies of a transcript, making it ideal for measuring low-abundance targets [5]. Targeted NGS approaches can achieve sensitivity down to 1% variant allele frequency when sequencing to sufficient depth, while maintaining the ability to detect novel variants [1].

In a clinical validation study for respiratory virus detection, a metagenomic NGS assay achieved mean limits of detection of 543 copies/mL across multiple viruses, with performance comparable to clinical RT-PCR assays [6]. The study demonstrated 93.6% sensitivity, 93.8% specificity, and 93.7% accuracy compared to gold-standard clinical multiplex RT-PCR testing, with performance increasing to 97.9% overall predictive agreement after discrepancy testing [6].

For mutation detection in cancer research, targeted NGS has demonstrated sufficient sensitivity for diagnostic applications, reliably detecting EGFR variants at allelic frequencies below 5% in DNA reference material [7]. In this study, NGS correctly identified all variants down to 3.3% allele frequency, demonstrating superior performance compared to the declared manufacturer detection limit of 5% [7].

Table 1: Sensitivity and Detection Capabilities Comparison

| Parameter | qPCR | Targeted NGS | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Few transcript copies | ~543 copies/mL [6] | Viral detection in clinical samples |

| Variant Allele Frequency | Not applicable | <5% [7] | EGFR mutation detection in NSCLC |

| Dynamic Range | Up to 7-8 logs | >5 logs [1] | Gene expression quantification |

| Accuracy | High for known targets | 93.7% overall [6] | Clinical validation |

Concordance and Reliability

Multiple studies have directly compared the concordance between NGS and qPCR technologies. In a comprehensive analysis of EGFR variant detection in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the overall concordance between NGS and qPCR was 76.14% (Cohen's Kappa = 0.5933) across 59 clinical tissue and cytology specimens [7]. The majority of discordant results concerned false-positive detection of EGFR exon 20 insertions by qPCR, with 9 out of 59 (15%) clinical samples showing discordant results for one or more EGFR variants in both assays [7].

Notably, NGS provided additional advantages in mutation characterization, offering exact identification of variants, calculation of allelic frequency, and demonstrating high analytical sensitivity that enhanced the basic diagnostic report [7]. The technology also identified frequently co-mutated genes (such as TP53) in EGFR-positive NSCLC patients, providing broader molecular context than qPCR alone [7].

In gene expression studies, Thermo Fisher Scientific reports high concordance between their TaqMan Gene Expression assays and Ion AmpliSeq Transcriptome kits, supporting the complementary use of both technologies within research workflows [5].

Table 2: Concordance Studies Between NGS and qPCR

| Study Focus | Concordance Rate | Sample Size | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR Variant Detection in NSCLC [7] | 76.14% | 59 clinical samples | 15% discordance rate; NGS provided exact variant identification |

| Respiratory Virus Detection [6] | 93.7% accuracy increasing to 97.9% after adjudication | 167 samples | NGS performance superior to RT-PCR (95.0% agreement) |

| Gene Expression Analysis [5] | High concordance | Not specified | Complementary use in workflows |

Methodological Considerations: Experimental Design and Best Practices

qPCR Experimental Protocols and Validation

Proper experimental design is crucial for generating reliable qPCR data. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide a framework for ensuring rigor and reproducibility in qPCR studies [4]. Key considerations include:

RNA Quality and Reverse Transcription: High-quality RNA with integrity number (RIN) >7 is essential for reliable results [8]. Reverse transcription should be performed using standardized protocols, with consistent input RNA amounts across samples [9].

Reference Gene Validation: The accuracy of relative quantification in qPCR depends on stable reference genes for normalization. Multiple algorithms including GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and RefFinder should be used to evaluate expression stability of candidate reference genes under specific experimental conditions [3] [9]. Studies in sweet potato identified IbACT, IbARF, and IbCYC as the most stable reference genes across different tissues, while IbGAP, IbRPL, and IbCOX showed high variability [3]. Similarly, wheat studies identified Ta2776, eF1a, Cyclophilin, Ta3006, Ta14126, and Ref 2 as stable references, while β-tubulin, CPD, and GAPDH were less reliable [9].

Data Analysis Methods: While the 2−ΔΔCT method remains widely used, ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance) provides enhanced statistical power and is not affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency [4]. Sharing raw qPCR fluorescence data with detailed analysis scripts improves reproducibility and allows independent verification of results [4].

NGS Experimental Workflows

NGS methodologies vary based on application, but share common workflow components:

Library Preparation: The process begins with library preparation where RNA is converted to sequencing-ready fragments. For transcriptome studies, rRNA depletion or poly-A selection enriches for mRNA. In a validated clinical mNGS assay for respiratory viruses, centrifugation alone produced the highest yield of detected viral reads, followed by a 15-min protocol for human rRNA depletion to decrease turnaround times [6].

Sequencing and Analysis: Different NGS platforms offer varying read lengths, throughput, and applications. Illumina sequencing uses a sequencing-by-synthesis approach with reversible dye terminators, while Ion Torrent detects hydrogen ions released during DNA synthesis [2]. Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore technologies provide long-read sequencing capabilities [2].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Computational pipelines are essential for NGS data interpretation. The SURPI+ pipeline used in clinical mNGS testing incorporates capabilities for viral load quantification, curated reference genome databases, and algorithms for novel virus detection through de novo assembly and translated nucleotide alignment [6].

Application-Based Technology Selection

When to Use qPCR

qPCR remains the preferred technology for specific applications where its strengths align with research needs:

Targeted Validation Studies: When validating a small number of pre-identified targets (typically ≤20), qPCR provides cost-effective, rapid, and highly sensitive quantification [5] [1]. The technology is ideal for confirming NGS findings or checking candidate biomarkers across large sample cohorts.

High-Throughput Screening: In drug discovery applications where hundreds to thousands of samples need to be screened for a limited number of targets, qPCR platforms with 384-well or higher formats offer practical solutions with rapid turnaround times [5].

Resource-Limited Settings: For laboratories without access to NGS infrastructure or bioinformatics expertise, qPCR provides an accessible alternative for gene expression analysis [5]. The benchtop workflows are familiar to most molecular biology laboratories, requiring minimal specialized training.

Clinical Diagnostics: For approved companion diagnostics targeting specific mutations, validated qPCR tests such as the "cobas EGFR Mutation Test v2" provide regulatory-approved options [7].

When to Use NGS

NGS technologies offer compelling advantages for applications requiring comprehensive genomic assessment:

Novel Discovery Research: When exploring new disease mechanisms or unknown transcriptional responses, NGS provides unbiased detection of both known and novel transcripts, enabling hypothesis-free experimental design [1].

Comprehensive Profiling: For studies requiring analysis of hundreds to thousands of targets, targeted NGS approaches are more efficient and cost-effective than running numerous individual qPCR reactions [5] [1].

Structural Variant Analysis: NGS can identify splice variants, fusion transcripts, and other structural variations that are inaccessible to standard qPCR approaches [1].

Low Abundance Variant Detection: With sufficient sequencing depth, NGS can detect rare transcripts or mutations present in heterogeneous samples at frequencies below 1% [1] [7].

Multiplexed Analysis: When sample material is limited, NGS allows simultaneous assessment of multiple genomic features (SNVs, indels, fusions, expression) from a single library [7].

Table 3: Application-Based Technology Selection Guide

| Research Application | Recommended Technology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Validation (≤20 targets) | qPCR | Cost-effective, rapid, established workflows |

| Novel Biomarker Discovery | NGS | Unbiased detection of known and novel transcripts |

| Large-scale Screening (100s+ targets) | Targeted NGS | More efficient than multiple qPCR reactions |

| Clinical Diagnostics (approved targets) | qPCR | Regulatory-approved tests available |

| Comprehensive Genomic Profiling | NGS | Simultaneous assessment of multiple variant types |

| Sample-Limited Studies | NGS | Multiple data types from single library |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

qPCR Research Solutions

TaqMan Gene Expression Assays: Pre-designed assays for specific exon-exon junctions enable targeted quantification of known transcripts. Assays are available for most genes and species in predesigned collections, with custom options for variant-specific detection [5].

TaqMan Array Platforms: Format options include 96- and 384-well plates pre-spotted with dried assays, microfluidic cards for low-volume reactions, and OpenArray plates for highest-throughput applications with lowest price per data point [5].

RNA Extraction and QC Reagents: TRIzol LS reagent provides reliable RNA isolation from blood samples [8], while NanoDrop spectrophotometers and Bioanalyzer systems assess RNA quality and integrity (RIN >7 recommended) [8].

Reverse Transcription Kits: SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System provides high-quality cDNA synthesis from total RNA [8].

NGS Research Solutions

Library Preparation Kits: Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep offers a rapid single-day solution for coding transcriptome analysis, while RNA Prep with Enrichment enables targeted interrogation of expansive gene panels [1].

Sequencing Platforms: MiSeq System suits smaller panels and targeted sequencing; NextSeq 1000 & 2000 Systems handle larger panels including RNA-Seq and exome sequencing [1].

Bioinformatics Tools: DRAGEN RNA App performs secondary analysis of RNA transcripts; Correlation Engine enables comparison of omics data with curated public datasets [1].

Validation Tools: Commercial reference panels (e.g., Accuplex Panel) with quantified viruses spiked into negative matrix serve as external positive controls for assay validation [6].

The NGS revolution has undoubtedly expanded our capabilities for comprehensive genomic profiling, yet qPCR maintains important applications in targeted validation studies. Rather than representing competing technologies, NGS and qPCR increasingly function as complementary approaches within integrated research workflows [5].

NGS provides the discovery power to identify novel transcripts and comprehensively profile transcriptional landscapes, while qPCR offers the precision and practicality for validating findings across large sample sets [5] [1]. This synergistic relationship is exemplified in studies where NGS identifies candidate biomarkers subsequently validated using qPCR in expanded cohorts [8].

For chemogenomic research, the technology selection should be driven by specific research questions, target numbers, sample availability, and resource constraints. Targeted NGS approaches effectively bridge the gap between comprehensive discovery and practical validation, offering balanced solutions for researchers seeking both breadth and depth in genomic characterization [7].

As NGS technologies continue to evolve with decreasing costs, streamlined workflows, and enhanced analytical sensitivity, their adoption in routine laboratory practice will undoubtedly expand. However, the fundamental principles of rigorous experimental design, appropriate controls, and transparent data analysis remain essential regardless of the technological platform selected [4] [6]. By understanding the strengths and limitations of both NGS and qPCR technologies, researchers can make informed decisions that optimize scientific rigor and resource allocation in their genomic studies.

In the evolving landscape of chemogenomic gene expression validation research, the debate often centers on next-generation sequencing (NGS) versus quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). While NGS provides unprecedented discovery power for profiling entire transcriptomes, qPCR remains the gold-standard technology for targeted gene expression analysis due to its exceptional sensitivity, precision, and cost-effectiveness [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of qPCR and NGS, demonstrating how these technologies function not as replacements but as complementary tools in the research pipeline. qPCR provides the critical verification and validation needed both upstream and downstream of NGS workflows, ensuring data integrity for high-confidence results in drug development applications [5].

The fundamental distinction lies in their operational paradigms: qPCR excels at quantifying predefined, specific targets with remarkable precision, while NGS operates as a hypothesis-free discovery engine capable of identifying novel transcripts and variants [1]. For research focused on validating expression changes in a defined panel of genes—particularly in chemogenomics where researchers investigate gene expression responses to chemical compounds—qPCR offers an unparalleled combination of sensitivity, throughput, and analytical robustness.

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. NGS for Gene Expression Analysis

Key Technical and Operational Differences

| Aspect | qPCR | NGS (RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput & Scalability | Ideal for low to moderate number of targets (typically ≤ 20-50 genes); workflow becomes cumbersome for hundreds of targets [1] | High-throughput; simultaneously profiles thousands of genes across multiple samples [1] |

| Discovery Power | Detects only known, predefined sequences; limited to established transcript knowledge [1] | Hypothesis-free; identifies novel transcripts, splice variants, and fusion genes without prior knowledge [5] [1] |

| Sensitivity | Can detect low-abundance transcripts; well-established for rare targets | Enhanced sensitivity for rare variants; can detect expression changes as subtle as 10% [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Excellent dynamic range (>7 logs) sufficient for most applications [5] | Wider dynamic range for quantifying gene expression without signal saturation [1] |

| Turnaround Time | Rapid (1-3 days for typical experiments); streamlined workflow [5] | Longer process (days to weeks); especially when outsourcing to core facilities [5] |

| Cost Considerations | Cost-effective for low target numbers; minimal reagent costs [5] | Higher cost per sample; more economical for profiling hundreds to thousands of targets [5] [1] |

| Data Complexity | Simple, quantitative data (Ct values); straightforward analysis [5] | Complex datasets requiring advanced bioinformatics expertise [10] |

| Absolute Quantification | Requires standard curves for absolute quantification | Provides absolute quantification through direct read counting [1] |

| Experimental Flexibility | Easily adaptable to different sample numbers and targets; ideal for time-course studies | Less flexible once a sequencing run is planned; better for fixed panel analyses |

Analytical Performance and Validation Data

| Performance Metric | qPCR Performance | NGS Performance | Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Not explicitly quantified in results, but described as "sufficient for most experimental contexts" [5] | Clinical mNGS assays for viruses: 543 copies/mL average LoD [6] | qPCR sensitivity is well-established through decades of use; NGS sensitivity continues to improve but may not match optimized qPCR assays for specific targets |

| Concordance with Orthogonal Methods | Often used as the gold standard for validating NGS results [5] | K-MASTER study vs. PCR: 87.4% sensitivity for KRAS, 77.8% for BRAF mutations in cancer [11] | NGS shows strong but imperfect concordance with qPCR, varying by gene and mutation type |

| Variant Detection Resolution | Limited to predefined mutations with specific probes | Identifies single nucleotide variants, indels, CNVs, and structural variants [12] | NGS provides comprehensive variant profiling unavailable to qPCR |

| Precision and Reproducibility | High reproducibility with low technical variation when properly validated [13] | Intra-assay precision: <10% CV; Inter-assay precision: <30% CV for mNGS [6] | Both technologies show excellent precision with proper controls and standardization |

| Linear Quantification Range | Wide dynamic range (>7 logs) with proper validation | 100% linearity demonstrated across multiple log dilutions in validation studies [6] | Both techniques provide highly linear quantification across clinically relevant ranges |

Core Principles and Methodologies of qPCR

The "Golden Rules" of Reliable qPCR

The exceptional sensitivity and specificity of qPCR depend on strict adherence to established methodological principles. Research from peer-reviewed literature outlines essential guidelines—the "golden rules"—for generating reproducible and accurate qPCR data [13]:

- Proper Sample Collection and RNA Quality: Harvest material from at least three biological replicates, freeze immediately in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C. Use RNA isolation procedures that produce high-quality total RNA, with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7 and ideally >9 [13].

- Genomic DNA Removal: Digest purified RNA with DNase I to remove contaminating genomic DNA, which can lead to spurious results. Confirm absence of genomic DNA by performing PCR on the treated RNA using gene-specific primers [13].

- Reverse Transcription Quality: Use a robust reverse transcriptase with no RNase H activity and high-integrity primers. Ensure all reactions contain the same total amount of RNA and use the same priming strategy to enable comparable gene expression measurements [13].

- Primer Design and Validation: Design gene-specific primers with standard criteria (Tm = 60±1°C, length 18-25 bases, GC content 40-60%) that generate a unique, short PCR product (60-150 bp). The 3'-untranslated region is often a good target because it is generally more unique than coding sequence [13].

- Reference Gene Validation: Validate reference genes for expression stability across all experimental conditions using tools like geNorm or BestKeeper. Do not assume traditional "housekeeping" genes are stable under all conditions [13].

Experimental Workflow and Quality Control

The following diagram illustrates a robust qPCR workflow with integrated quality control checkpoints, essential for generating publication-quality data:

Figure 1: Comprehensive qPCR workflow with integrated quality control checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after sample collection | Critical for preventing RNA degradation; must be compatible with downstream applications |

| High-Quality Total RNA Isolation Kit | Isulates intact RNA from biological samples | Should yield RNA with RIN >7, A260/A280 >1.8, A260/A230 >2.0 [13] |

| DNase I Enzyme | Removes contaminating genomic DNA | Essential for accurate RNA quantification; must be completely inactivated or removed after treatment |

| Reverse Transcriptase without RNase H Activity | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates | High processivity and yield; minimal secondary structure effects; examples include SuperScript III [13] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, buffers, and dNTPs for amplification | Contains hot-start Taq polymerase, SYBR Green or probe-based chemistry, and optimized buffer [13] |

| Validated Primer Sets | Specifically amplify target sequences | Designed to generate 60-150 bp products with Tm = 60±1°C; tested for specificity and efficiency [13] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalize for technical variation | Must be validated for stable expression under experimental conditions [13] |

Complementary Roles: Integrated NGS and qPCR Workflows

Modern chemogenomic research increasingly leverages the complementary strengths of NGS and qPCR. The following diagram illustrates how these technologies integrate throughout a typical research pipeline:

Figure 2: Integrated research workflow showing complementary NGS and qPCR roles.

In this synergistic approach, qPCR serves critical functions at multiple points:

- Upstream of NGS: qPCR is commonly used to check cDNA integrity prior to NGS library preparation, ensuring that only high-quality samples proceed to expensive sequencing steps [5].

- Downstream of NGS: qPCR remains the go-to method for verification of NGS results, particularly for key findings that will form the basis for further research or clinical applications [5].

- Follow-up Studies: For research involving a targeted panel of transcripts discovered during NGS screening, qPCR is the gold-standard technology for comprehensive analysis across larger sample sets [5].

This integrated approach combines the discovery power of NGS with the precision and reliability of qPCR, delivering both innovation and validation in chemogenomic research.

The choice between qPCR and NGS is not a matter of technological superiority but of strategic alignment with research objectives. qPCR maintains its position as the gold standard for targeted gene expression quantification due to its exceptional sensitivity, reproducibility, cost-effectiveness, and operational efficiency—particularly valuable in chemogenomic research where specific pathways or gene sets are investigated. Its well-established protocols, straightforward data analysis, and rapid turnaround time make it ideal for focused validation studies and high-throughput screening of defined targets.

Conversely, NGS provides unparalleled capabilities for discovery-oriented research, offering hypothesis-free experimental design, detection of novel transcripts, and comprehensive transcriptome profiling. The most advanced research programs leverage both technologies strategically: employing NGS for initial discovery and qPCR for rigorous validation and expanded studies. This integrated approach ensures both innovation and reliability, meeting the dual demands of novel insight and reproducible results in drug development and precision medicine.

Core Capabilities and Limitations at a Glance

The choice between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) is fundamental in chemogenomics, where validating gene expression changes in response to small molecules is crucial. The table below summarizes their core attributes to guide your experimental design.

| Feature | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Power | Hypothesis-free; detects known and novel transcripts, splice variants, and mutations [1] [2]. | Targeted; limited to known, pre-defined sequences [1] [14]. |

| Throughput & Multiplexing | Very High. Can profile from a few to >10,000 targets across multiple samples simultaneously [1] [14]. | Low to Moderate. Typically 1 to 5 targets per reaction [14]. |

| Quantitative Nature | Quantitative; provides absolute or relative expression values (e.g., read counts) [1] [14]. | Quantitative; provides cycle threshold (Cq) values relative to standards [14]. |

| Sensitivity | High; can detect rare variants and subtle expression changes (down to 10%) with sufficient depth [1] [7]. | High; excellent for detecting low-abundance targets, but limited to known sequences [14]. |

| Data Complexity & Analysis | High. Requires advanced bioinformatics for data processing and interpretation [15]. | Low. Data analysis is straightforward with familiar, accessible software [5] [1]. |

| Typical Run Time | Longer. Library prep and sequencing can take hours to days [14]. | Shorter. Rapid sample-to-answer in 1-3 hours [5] [14]. |

| Cost Consideration | Higher per-sample cost, but lower per-base cost. Requires significant investment in infrastructure and analysis [15]. | Low per-reaction cost. Accessible equipment available in most labs [5] [1]. |

Experimental Validation: A Head-to-Head Case Study

A 2024 study directly compared a targeted NGS assay (Illumina TruSight Tumor 15) with an IVD-certified qPCR test (Roche cobas EGFR Mutation Test v2) for detecting druggable EGFR variants in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), a common chemogenomics application [7].

Key Experimental Findings

| Metric | Targeted NGS Performance | qPCR Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | 76.14% (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.5933) [7] | |

| Primary Discordance | Accurate identification of exon 20 insertions [7]. | False-positive detection of EGFR exon 20 insertions [7]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Demonstrated sufficient sensitivity for variants with <5% Variant Allele Frequency (VAF), correctly identifying variants down to 3.3% VAF [7]. | Designed for known variants; limited by its pre-defined targets [7]. |

| Additional Data | Provided Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) and identified co-mutations (e.g., in TP53) [7]. | Qualitative result (presence/absence of predefined mutations) [7]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow diagrams the methodology used in the comparative study.

Methodology Details:

- Samples: 59 NSCLC tissue and cytology specimens, alongside biosynthetic and biological DNA reference materials with known EGFR variant allele frequencies (VAF) [7].

- qPCR Method: The IVD-certified cobas EGFR Mutation Test v2 was run according to manufacturer specifications, using cycle threshold (Ct) values for automated result interpretation [7].

- Targeted NGS Method: Libraries were prepared using the TruSight Tumor 15 panel. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq system, with a quality threshold of QC30 > 85% and a median coverage depth of >6,000x. Bioinformatic analysis involved aligning reads to the human reference genome (hg19) and calling variants [7].

- Validation: The sensitivity and specificity of the NGS assay were evaluated using DNA reference material, and its repeatability was assessed via the coefficient of variation (CV%) between runs [7].

Strategic Workflow for Chemogenomic Validation

In practice, NGS and qPCR are often complementary. The following diagram illustrates a robust, integrated workflow for gene expression validation in chemogenomics research.

Workflow Rationale:

- Discovery Phase (NGS): Use RNA-Seq or targeted NGS panels for agnostic discovery of all transcriptomic changes induced by a small molecule. This is critical for identifying novel biomarkers, splice variants, and off-target effects without prior sequence knowledge [5] [1].

- Validation Phase (qPCR): Use qPCR to verify the expression changes of a focused panel of key genes identified in the NGS discovery phase. This leverages qPCR's speed, low cost, and operational simplicity to ensure the robustness of initial findings on larger sample sets [5] [14].

- Follow-up Studies: For absolute quantification of critical low-abundance transcripts or rare mutations, digital PCR (dPCR) can be employed for the highest sensitivity and precision [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of NGS and qPCR workflows relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

| Category | Item | Function in Research | Example Platforms & Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep | Targeted RNA Panels | Enables focused, cost-effective sequencing of a predefined set of genes relevant to specific pathways (e.g., cancer, signaling). | Illumina TruSight Tumor 15 [7], Thermo Fisher Ion AmpliSeq [5] |

| Whole-Transcriptome Kits | For unbiased discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants, and global expression profiling. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep [1] | |

| qPCR Assays | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Predesigned, highly specific probe-based assays for quantifying the expression of known genetic targets. | Thermo Fisher TaqMan Assays [5] |

| TaqMan Array Cards | 384-well microfluidic cards pre-loaded with assays for medium-throughput profiling of focused gene sets. | Thermo Fisher TaqMan Array Cards [5] | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Benchtop Sequencers | Ideal for targeted panels and smaller-scale sequencing projects in individual labs. | Illumina MiSeq [1] [7] |

| High-Throughput Sequencers | For large-scale projects like whole transcriptomes across many samples. | Illumina NovaSeq X Series [16] | |

| Critical Analysis Software | Bioinformatic Secondary Analysis | Processes raw sequencing data into aligned, analyzed formats; often integrated with sequencers. | Illumina DRAGEN RNA App [1] [16] |

| Bioinformatic Knowledge Bases | Puts private NGS data into biological context with curated public data for functional interpretation. | Illumina Correlation Engine [1] |

Defining the 'Fit-for-Purpose' Concept in Analytical Validation for Gene Expression Studies

In the rapidly evolving field of gene expression analysis, the choice between next-generation sequencing (NGS) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) represents a critical methodological crossroad. The concept of 'fit-for-purpose' (FFP) validation has emerged as an essential framework for guiding this decision, ensuring that the level of analytical validation is sufficient to support a specific research or clinical context of use [17]. As defined by consensus guidelines, FFP is "a conclusion that the level of validation associated with a medical product development tool is sufficient to support its context of use" [17]. This principle recognizes that different research questions and clinical applications demand distinct levels of evidence for analytical validity.

The growing importance of FFP validation reflects the expanding applications of genomic technologies across basic research, clinical trials, and in vitro diagnostics. For chemogenomic studies investigating gene expression responses to chemical compounds, selecting the appropriate analytical platform is paramount for generating reliable, interpretable data. This guide provides an objective comparison of NGS and qPCR technologies through the lens of FFP validation, enabling researchers to align their platform selection with specific experimental needs and validation requirements.

Analytical Validation Principles for Gene Expression Analysis

Core Validation Parameters

Analytical validation ensures that a test reliably measures what it claims to measure. For both NGS and qPCR technologies, key performance characteristics must be evaluated to establish analytical validity [17]:

- Analytical Sensitivity: The ability to detect the target analyte (e.g., minimum detectable concentration or limit of detection)

- Analytical Specificity: The ability to distinguish the target from non-target analytes

- Analytical Precision: The closeness of agreement between repeated measurements (includes repeatability and reproducibility)

- Analytical Trueness/Accuracy: The closeness of measured values to true values

The required stringency for these parameters varies significantly based on the context of use. Research use only (RUO) applications may tolerate more variability, whereas in vitro diagnostics (IVD) or companion diagnostic applications demand rigorous validation with predefined performance thresholds [17].

The Validation Spectrum: From Research to Clinical Applications

The validation requirements for genomic technologies exist along a continuum, with increasing stringency as applications move closer to clinical decision-making:

Figure 1: The analytical validation spectrum for genomic technologies, from basic research to clinical applications.

Clinical Research (CR) Assays occupy an intermediate position, requiring more thorough validation than basic research assays but not needing full IVD certification [17]. These assays are particularly relevant for biomarker development in clinical trials, where reliable results are essential for making preliminary assessments of diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive value.

Technology Comparison: NGS vs. qPCR for Gene Expression Analysis

Key Technical Differentiators

NGS and qPCR offer distinct advantages and limitations for gene expression studies, making them differentially suited for specific applications:

Table 1: Comparative analysis of NGS and qPCR technologies for gene expression studies

| Parameter | qPCR | NGS (RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Limited, optimal for ≤20 targets [1] | High, capable of profiling thousands of targets simultaneously [1] |

| Discovery Power | Limited to known, predefined targets [1] | High, enables novel transcript discovery [1] |

| Sensitivity | Sufficient for most applications [5] | Enhanced sensitivity for rare variants and lowly expressed genes [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Sufficient for most applications [5] | Wider dynamic range without signal saturation [1] |

| Variant Resolution | Limited to predefined variants | Single-base resolution [1] |

| Turnaround Time | 1-3 days for typical experiments [5] | Longer, especially when outsourcing to core facilities [5] |

| Cost Considerations | More cost-effective for low target numbers [5] [1] | Higher upfront costs, more economical for large target sets [5] [1] |

| Data Complexity | Manageable datasets, simpler analysis [15] | Complex datasets requiring advanced bioinformatics [15] |

Complementary Roles in Validation Workflows

Rather than existing in opposition, NGS and qPCR often play complementary roles in gene expression validation workflows. A common practice is to use qPCR both upstream and downstream of NGS to ensure data integrity [5]. Upstream applications include quality control checks, such as verifying cDNA integrity prior to NGS library preparation. Downstream, qPCR serves as the gold-standard method for verifying NGS results or for follow-up studies targeting specific transcripts identified during NGS screening [5].

This complementary relationship extends to analytical validation, where qPCR often provides orthogonal confirmation of NGS findings. A 2023 benchmarking study demonstrated that while different bioinformatics tools for NGS-based miRNA profiling generated divergent results, qPCR validation confirmed the expression of investigated miRNAs, with "strong and significant correlation coefficients for a subset of the tested miRNAs" [18].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Robust analytical validation begins with rigorous sample preparation. For integrated RNA and DNA sequencing approaches, recommended protocols include:

- Nucleic Acid Isolation: Using commercial kits (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit) with quality assessment via Qubit, NanoDrop, and TapeStation systems [19]

- RNA Integrity: Ensuring RNA integrity numbers (RIN) > 7.0 for reliable results

- Library Preparation: Following manufacturer protocols with appropriate input amounts (10-200 ng) [19]

- Quality Control: Implementing standard QC metrics including Q30 scores > 90% for sequencing data [19]

For qPCR experiments, the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines provide comprehensive recommendations for experimental design, including appropriate sample collection, storage conditions, and RNA quality assessment [17].

Reference Materials and Normalization Strategies

Effective normalization is crucial for accurate gene expression quantification. For qPCR, recent advances leverage large RNA-Seq databases to identify optimal reference genes:

- Stable Gene Combinations: Research demonstrates that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform traditional reference genes for qPCR normalization [20]

- Algorithmic Selection: Using mathematical variance calculations on comprehensive RNA-Seq datasets to identify genes whose expressions balance each other across experimental conditions [20]

For NGS validation, custom reference standards can be generated containing thousands of variants. One recent study utilized samples "containing 3042 SNVs and 47,466 CNVs" for comprehensive analytical validation [19].

Orthogonal Validation Methodologies

Orthogonal validation using different methodological principles provides strong evidence of analytical validity:

- NGS to qPCR Correlation: Comparing expression measurements between platforms using statistical correlation coefficients [18]

- Clinical Sample Testing: Validating assays against well-characterized patient samples with known expression profiles [19]

- Inter-laboratory Studies: Assessing reproducibility across different testing sites and operators [21]

Figure 2: Workflow for analytical validation of gene expression technologies, highlighting key experimental stages.

Application-Based Selection Guide

Decision Framework for Technology Selection

The FFP principle dictates that technology selection should be driven by specific research questions and application requirements:

Table 2: Fit-for-purpose technology selection based on research applications

| Research Context | Recommended Technology | Rationale | Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Gene Expression (≤20 genes) | qPCR | Cost-effective, rapid turnaround, familiar workflow [5] [1] | Standard curve validation, precision assessment, reference gene verification [17] |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | NGS (RNA-Seq) | Hypothesis-free approach, detects unknown transcripts [5] [1] | Limit of detection, specificity for novel targets, bioinformatic pipeline validation |

| Biomarker Screening & Identification | NGS (RNA-Seq) | Comprehensive profiling, detects subtle expression changes [1] | Sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility across sample types |

| Validation of NGS Findings | qPCR | Gold-standard for targeted quantification [5] [18] | Correlation with NGS data, precision, dynamic range |

| Clinical Trial Assays | Platform dependent on context | Balance between comprehensiveness and practicality [22] | Stringent validation following FDA/EMA guidelines [17] |

| Companion Diagnostic Development | Platform dependent on actionable targets | Alignment with therapeutic mechanism and regulatory pathway [22] | Full analytical and clinical validation per regulatory standards [23] |

Successful implementation of gene expression technologies requires access to specialized reagents and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and resources for gene expression validation

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation | AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction, preservation of nucleic acid integrity [19] |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina), SureSelect XTHS2 | Library construction for NGS, target enrichment [19] |

| qPCR Reagents | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, miRCURY LNA SYBR Green PCR Kit | Target detection and quantification, miRNA analysis [5] [18] |

| Reference Materials | Commercial reference standards, cell line mixtures | Analytical validation, quality control, proficiency testing [19] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BWA aligner, STAR aligner, GATK, Strelka2 | Sequence alignment, variant calling, expression quantification [19] |

| Validation Software | GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper | Reference gene evaluation, normalization strategy optimization [20] |

The 'fit-for-purpose' framework provides an essential paradigm for selecting and validating gene expression technologies. Rather than seeking a universal superior technology, researchers should align their choice of NGS or qPCR with specific research objectives, validation requirements, and resource constraints. NGS offers unparalleled discovery power for comprehensive transcriptome characterization, while qPCR provides robust, cost-effective solutions for targeted gene expression analysis.

The evolving regulatory landscape for genomic technologies continues to emphasize the importance of proper analytical validation, with increasing attention to standardized validation frameworks for combined RNA and DNA sequencing approaches [19]. As both technologies advance, their complementary roles in chemogenomic research are likely to strengthen, with integrated workflows leveraging the unique strengths of each platform to provide comprehensive insights into gene expression responses to chemical perturbations.

By applying FFP principles to technology selection and validation strategies, researchers can ensure that their methodological choices effectively support their scientific objectives while generating reliable, reproducible data that advances our understanding of gene expression in health and disease.

Strategic Deployment: Matching NGS and qPCR to Your Research Workflow

In the field of chemogenomic gene expression validation research, the choice between next-generation sequencing (NGS) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) represents a fundamental strategic decision. While qPCR has long been the gold standard for targeted gene expression analysis due to its sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness for analyzing a limited number of predefined targets [5] [24], its utility is inherently constrained by its reliance on prior knowledge of sequence information [1]. In contrast, NGS technologies enable a hypothesis-free approach that does not require predesigned probes or primers, providing unprecedented discovery power to identify novel biomarkers and pathways without predetermined constraints [1] [2]. This capability makes NGS particularly valuable for comprehensive genomic profiling in complex diseases like cancer, where identifying both known and emerging biomarkers is crucial for advancing precision medicine [25] [24].

The growing demand for personalized diagnostics, projected to reach nearly $590 billion by 2028, is driving increased adoption of NGS in research and clinical settings [24]. This comprehensive guide examines the application of NGS for unbiased discovery in novel biomarker and pathway identification, comparing its performance with qPCR alternatives and providing supporting experimental data to inform research methodologies in chemogenomic studies.

Technology Comparison: NGS vs. qPCR for Discovery Research

Fundamental Technological Differences

The core distinction between NGS and qPCR lies in their fundamental approaches to genetic analysis. qPCR is designed to detect and quantify specific, known sequences using predesigned probes or primers, making it ideal for validating predefined targets but incapable of discovering novel genetic elements [1] [24]. Its analytical scope is limited to the number of targets that can be practically incorporated into a single assay, typically ranging from a few to approximately 20 targets in a cost-effective manner [5] [1].

NGS, in contrast, employs a massively parallel sequencing approach that can simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments without requiring prior knowledge of target sequences [1] [2]. This unbiased approach allows researchers to profile thousands of target regions in a single assay, detecting both known and novel transcripts with single-base resolution [1]. The technology's dynamic range enables quantification of gene expression across approximately 5-6 orders of magnitude, surpassing qPCR's typical dynamic range of 3-4 orders of magnitude, particularly for detecting rare variants and lowly expressed genes [1].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics of NGS vs. qPCR for Gene Expression Analysis

| Parameter | qPCR | NGS (RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Power | Limited to known sequences; requires pre-designed probes/primers [1] [24] | Hypothesis-free; detects known and novel transcripts, splice variants, and fusion genes [1] |

| Throughput | Effective for low target numbers (typically ≤20); workflow becomes cumbersome for multiple targets [5] [1] | High-throughput; profiles >1000 target regions across multiple samples simultaneously [1] |

| Sensitivity | High for abundant transcripts; can detect down to 1-10 copies per reaction [26] | Enhanced sensitivity for rare variants and lowly expressed genes; can detect expression changes down to 10% [1] |

| Dynamic Range | ~3-4 orders of magnitude [1] | ~5-6 orders of magnitude; no signal saturation [1] |

| Mutation Resolution | Limited to predefined variants [1] | Single-nucleotide resolution; detects SNVs, indels, and structural variants [1] |

| Turnaround Time | 1-2 days for ~20 samples and 10 targets [5] | 2+ days for library prep to data analysis; longer if outsourcing required [5] |

| Cost Efficiency | Cost-effective for low target numbers; price increases with target number [5] [1] | More expensive for simple experiments; cost-effective for multi-target analyses [5] [1] |

Experimental Evidence: NGS Performance in Biomarker Discovery

Case Study: Comprehensive Genomic Profiling in Oncology

NGS has transformed biomarker testing in solid tumors by enabling simultaneous analysis of hundreds of genes in a single platform [25]. In lung cancer, for example, NGS allows researchers to test for approximately 12 different biomarkers (including EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and RET) within a unified workflow, significantly streamlining the discovery process compared to sequential qPCR assays [25]. This comprehensive approach not only identifies currently actionable targets but also reveals emerging biomarkers that may inform future therapeutic development and clinical trial enrollment [25].

The unbiased nature of NGS is particularly valuable in cancer research where tumor heterogeneity and evolution can produce novel genetic alterations that would be undetectable using targeted qPCR approaches. NGS provides the discovery power to identify these novel variants, enabling more personalized treatment strategies based on a tumor's complete genetic profile rather than a limited set of predefined markers [24].

Comparative Validation: NGS vs. qPCR in Clinical Detection

A 2025 study comparing NGS, real-time PCR, and HRM-PCR for Helicobacter pylori detection in pediatric biopsies provides compelling experimental data on their relative performance [26]. The research analyzed 40 unique pediatric biopsy samples, with results demonstrating that both real-time PCR-based methods detected H. pylori DNA in 16 samples (40.0%), while NGS detected the pathogen in 14 samples (35.0%) [26].

Table 2: Experimental Detection Results for H. pylori in Pediatric Biopsies

| Method | Detection Rate | Quantification Metric | Additional Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVD-certified qPCR | 16/40 samples (40.0%) | Cq values: 17.51-32.21 [26] | Targeted detection only |

| HRM-PCR | 16/40 samples (40.0%) | Melt curve analysis [26] | Limited variant discrimination |

| NGS | 14/40 samples (35.0%) | Read counts: 7,768-42,924 [26] | Comprehensive genomic characterization; variant identification |

While PCR methods demonstrated slightly higher sensitivity in this particular application, the study highlighted NGS's unique value in diagnosing difficult or ambiguous cases by enabling simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens and comprehensive genetic characterization [26]. The authors noted that NGS could complement PCR in complex diagnostic scenarios, though PCR variants remained more cost-effective for routine targeted detection [26].

Methodological Workflow: Implementing NGS for Biomarker Discovery

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

Proper experimental design is crucial for successful NGS-based biomarker discovery. The process begins with careful sample collection and RNA extraction, ensuring high nucleic acid quality and integrity. For transcriptome analyses, both whole-transcriptome and targeted RNA-Seq approaches are available, with the former recommended when detecting all cellular RNA species (mRNA, miRNA, tRNA) or investigating transcript isoform diversity and novel gene discovery [5].

Quality control checks should be implemented throughout the workflow. As noted in comparative analyses, "it is common practice to use real-time PCR both upstream and downstream of NGS," with TaqMan real-time PCR frequently employed to check cDNA integrity prior to NGS library preparation [5]. This integrated approach ensures data quality while leveraging the respective strengths of both technologies.

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The NGS data analysis workflow involves multiple computational steps, each requiring specialized tools and approaches. Following sequencing, raw reads must undergo quality assessment, adapter trimming, and alignment to reference genomes before variant calling and expression quantification.

NGS Data Analysis Workflow

Advanced bioinformatic tools such as the DRAGEN RNA App can perform secondary analysis of RNA transcripts, while knowledge bases like Correlation Engine enable comparison of NGS data with previously generated qPCR data and public datasets [1]. These computational resources are essential for translating raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights about novel biomarkers and pathways.

Validation Strategies: Integrating NGS and qPCR Approaches

Reference Gene Selection and Validation

A critical consideration in gene expression studies, whether using NGS or qPCR, is the selection of appropriate reference genes for data normalization. A 2024 study demonstrated that "a stable combination of non-stable genes outperforms standard reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization" [27]. This research highlighted that classical housekeeping genes do not always display stable expression across different experimental conditions, potentially compromising data accuracy if used indiscriminately for normalization [27].

The study proposed a novel methodology using comprehensive RNA-Seq databases to identify optimal gene combinations for qPCR normalization, demonstrating that "such an optimal combination of genes can be found using a comprehensive database of RNA-Seq data" [27]. This approach leverages the unbiased nature of NGS data to enhance the rigor of downstream qPCR validation, representing a powerful integration of both technologies.

Research in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) further emphasized the importance of context-specific reference gene validation, showing that gene stability varies significantly across different tissues [3]. Through analysis of ten candidate reference genes across four tissue types (fibrous root, tuberous root, stem, and leaf), researchers found that IbACT, IbARF, and IbCYC displayed the most stable expression, while IbGAP, IbRPL, and IbCOX were classified as the least stable genes [3]. These findings underscore the necessity of empirically validating reference genes for specific experimental conditions rather than relying on conventional housekeeping genes.

Advanced Data Analysis Methods

Recent methodological advances have improved the rigor and reproducibility of gene expression data analysis. A 2025 study highlighted that Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) "enhances statistical power compared to 2−ΔΔCT" and that "ANCOVA P-values are not affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency" [4]. This approach offers greater robustness compared to the widely used 2−ΔΔCT method, which often overlooks critical factors such as amplification efficiency variability and reference gene stability [4].

The study also emphasized the importance of sharing raw qPCR fluorescence data alongside detailed analysis scripts to improve reproducibility, noting that "widespread reliance on the 2−ΔΔCT method often overlooks critical factors such as amplification efficiency variability and reference gene stability" [4]. Implementing these improved analytical methods strengthens the validation process for biomarkers initially discovered through NGS.

Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NGS Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | Library preparation | Analyzes coding transcriptome for expression profiling [1] |

| RNA Prep with Enrichment + Targeted Panel | Targeted RNA sequencing | Enables focused interrogation of specific gene sets with improved coverage [1] |

| MiSeq System | Benchtop sequencing | Ideal for smaller panels and targeted resequencing applications [1] |

| NextSeq 1000 & 2000 Systems | High-throughput sequencing | Supports larger panels, RNA-Seq, and exome sequencing [1] |

| dUTP Master Mixes | Prevents carryover contamination | Essential for high-throughput settings and sensitive applications [24] |

| Lyo-Ready Master Mixes | Ambient-temperature stability | Enables development of stable assays for field or point-of-care use [24] |

| Glycerol-Free Enzymes | Enhanced performance in NGS library prep | Reduces cost of NGS testing and improves portability [24] |

The comparative analysis of NGS and qPCR technologies reveals a complementary relationship rather than a competitive one in chemogenomic research. NGS provides unparalleled discovery power for identifying novel biomarkers and pathways through its hypothesis-free approach and massive parallel sequencing capability [1] [2]. Meanwhile, qPCR remains invaluable for targeted validation of discovered biomarkers, offering rapid turnaround, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity for analyzing limited numbers of predefined targets [5] [24].

A strategic integrated approach leverages the strengths of both technologies: utilizing NGS for initial comprehensive discovery phases followed by qPCR for validation and routine monitoring of established biomarkers [5] [24]. This hybrid model maximizes both discovery power and practical efficiency, creating robust workflows that advance precision medicine through comprehensive genomic insight coupled with practical validation methodologies.

As personalized medicine continues to evolve, the synergistic combination of NGS for unbiased discovery and qPCR for focused validation will remain essential for translating genomic information into actionable biological insights and therapeutic strategies. Researchers are encouraged to implement rigorous validation protocols, including careful reference gene selection and advanced statistical methods, to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of their biomarker discovery efforts.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) are often presented as competing technologies in gene expression analysis. However, in modern chemogenomic research, they serve complementary roles within a cohesive workflow. NGS provides unparalleled discovery power for identifying novel transcripts, splice variants, and differentially expressed genes across the entire transcriptome without prior sequence knowledge [1]. Despite this powerful discovery capability, the translation of NGS findings into clinically applicable biomarkers requires rigorous validation in larger, independent cohorts—a role for which qPCR remains exceptionally well-suited [5].

This guide explores the strategic implementation of qPCR for targeted validation of candidate genes initially identified through NGS screens. We objectively compare the performance characteristics of both technologies and provide detailed experimental protocols for employing qPCR to verify gene expression signatures in expanded sample sets, with a focus on producing publication-quality, reproducible data that meets the stringent requirements of drug development research.

Technology Comparison: NGS Discovery Versus qPCR Validation

Key Differences in Application and Capabilities

The choice between NGS and qPCR depends on several factors, including the number of targets, sample availability, budgetary considerations, and study objectives [1]. While NGS excels at hypothesis-free discovery, qPCR provides a more efficient and cost-effective solution for focused validation studies.

Table 1: Fundamental differences between NGS and qPCR technologies

| Parameter | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Discovery of novel variants, transcripts, and splice isoforms [1] | Targeted validation and quantification of known sequences [1] |

| Discovery Power | High (hypothesis-free approach) [1] | Limited to known, predefined targets [1] |

| Optimal Target Number | >20 targets (hundreds to thousands) [1] [5] | ≤20 targets [1] |

| Throughput | High for multiple genes across multiple samples [1] | High for few targets across many samples [1] |

| Sensitivity | Can detect rare variants and transcripts [1] | Highly sensitive for detecting low-abundance targets [1] |

| Detection Capability | Known and novel transcripts [1] | Known sequences only [1] |

| Mutation Resolution | Single nucleotide variants to large chromosomal rearrangements [1] | Specific predefined variants only [1] |

Performance Metrics and Practical Considerations

Beyond their fundamental differences, NGS and qPCR exhibit distinct performance characteristics that directly impact their suitability for validation workflows.

Table 2: Performance comparison for gene expression analysis

| Performance Metric | RNA-Seq (NGS) | Targeted Amplicon NGS | qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Wide [1] | Wide [5] | Sufficient for most applications [5] |

| Time to Results | Days to weeks (including library prep) [5] | Days [5] | 1-3 days [5] |

| Cost Factor | Higher for targeted studies [5] | More expensive for <20 targets [5] | Lower for limited target numbers [5] |

| Accuracy/Error Rate | ~0.1-1% depending on platform [28] [29] | ~0.1-1% depending on platform [28] | High (gold standard for quantification) [5] |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate to high | Moderate to high | High |

| Ease of Implementation | Complex workflow, specialized equipment [28] | Complex workflow [5] | Simple, familiar workflow [1] |

Experimental Design for Targeted Validation

Strategic Approach to Validation Study Design

The transition from NGS discovery to qPCR validation requires careful experimental planning to ensure statistically robust, reproducible results. Well-designed validation studies incorporate appropriate sample sizes, adequate controls, and standardized processing protocols to minimize technical variability.

A key consideration in validation study design is the implementation of the "fit-for-purpose" (FFP) concept, where the level of validation rigor is sufficient to support the specific context of use [17]. For candidate biomarkers intended to support clinical decision-making, this includes evaluating both analytical performance (accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity) and clinical performance (diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, predictive values) [17].

Workflow Integration: From NGS Discovery to qPCR Validation

The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow integrating NGS discovery with qPCR validation, highlighting key decision points and quality control steps throughout the process:

Detailed qPCR Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

Proper sample acquisition, processing, and RNA extraction are critical preanalytical steps that significantly impact qPCR results [17]. Consistent handling procedures must be maintained throughout the validation study.

- Sample Collection: Standardize collection timing and conditions. For blood samples, collect in the early morning after an overnight fast using EDTA tubes, and process within 2 hours of collection [8].

- RNA Extraction: Use validated extraction methods (e.g., TRIzol LS reagent) following manufacturer protocols. Assess RNA quality and quantity using NanoDrop spectrophotometry and Agilent Bioanalyzer [8].

- Quality Thresholds: Implement strict inclusion criteria, accepting only samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) >7 and A260/A280 ratios between 1.8-2.0 for downstream analysis [8].

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize first-strand cDNA from 1μg of total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System or equivalent reverse transcriptase kits [8].

qPCR Assay Design and Optimization

Effective qPCR validation requires carefully designed assays that provide specific, efficient amplification of candidate genes.

- Assay Design: Utilize bioinformatics tools like RealTimeDesign software to create specific primer and probe sequences. For multiplex assays, design all assays together to minimize primer-dimers and ensure compatibility [30].

- Probe Selection: Select fluorophore-quencher pairs appropriate for your detection system. Black Hole Quencher (BHQ)-modified probes provide low background fluorescence ideal for multiplexing [30].

- Validation Steps: Test individual assay performance before multiplexing. Generate standard curves using serial dilutions of template to determine amplification efficiency (90-110% ideal), dynamic range, and limit of detection [30].

- Multiplex Optimization: Combine validated individual assays and verify performance remains uncompromised. Cycle threshold values for individual reactions should agree with multiplexed reactions [30].

qPCR Run Setup and Conditions

Standardized reaction setup and cycling conditions are essential for reproducible results across large validation cohorts.

- Reaction Composition: Use SYBR Green Master Mix or equivalent probe-based chemistry. For multiplex reactions, use a master mix specifically formulated for multiplexing, potentially supplemented with additional components to improve performance [30].

- Controls: Include no-template controls (NTC) to detect contamination, positive controls to confirm assay performance, and reference gene controls for normalization.

- Thermal Cycling: Program instruments with initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute on an ABI 7900HT system or equivalent [8].

- Replication: Perform all reactions in triplicate to account for technical variability and enable statistical assessment of data quality.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantification Methods and Normalization Strategies

Robust data analysis is essential for deriving biologically meaningful conclusions from qPCR validation studies.

- Quantification Method: Calculate relative gene expression using the 2-ΔΔCt method. For absolute quantification, establish standard curves with known template concentrations [8].

- Reference Gene Selection: Normalize data to appropriate endogenous control genes (e.g., GAPDH) that show stable expression across experimental conditions [8] [31].

- Data Transformation: Apply log2 transformation to gene expression values before statistical analysis to normalize distribution [8].

- Quality Assessment: Monitor amplification curves, efficiency values, and melting curves (for SYBR Green assays) to identify problematic reactions that require exclusion.

Statistical Validation and Performance Metrics

Comprehensive statistical analysis confirms the reliability of candidate biomarkers in distinguishing biological states.

- Effect Size Calculation: Use Hedges' g effect size calculations to combine gene expression effect sizes across multiple studies or cohorts via random-effects meta-analysis [8].

- Discriminatory Power: Evaluate diagnostic performance using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Report area under the curve (AUC) values with confidence intervals [8].

- Statistical Significance: Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections (e.g., false discovery rate) to account for comparisons across multiple candidate genes [8].

- Reproducibility Assessment: Determine intra-assay and inter-assay precision through repeated measurements of quality control samples.

Advanced Applications: Enhancing qPCR Capabilities

Multiplex qPCR Strategies

Multiplex qPCR enables simultaneous quantification of multiple targets in a single reaction, conserving precious samples while increasing throughput.

- Dye Selection: Choose reporter dyes with distinct emission spectra that align with instrument detection capabilities. CAL Fluor Red 610, Quasar 670, and FAM are common choices for 3-plex assays [30].

- Crosstalk Management: Perform dye calibration and screen for crosstalk (fluorescent bleed-through between channels) during assay validation. Most qPCR instruments require dye calibration to distinguish fluorescent signals [30].

- Competition Management: Monitor for assay dominance in multiplex reactions. Qualify assay performance using disproportionate copy numbers to simulate real sample conditions where targets may vary widely in abundance [30].

Machine Learning-Enhanced qPCR

Recent advances integrate machine learning (ML) with qPCR to enhance multiplexing capabilities and analytical precision.

- Signal Classification: ML algorithms can leverage information contained in amplification and melting curves to accurately classify multiple nucleic acid targets in single reactions, potentially exceeding traditional detection limits [32].

- Assay Optimization: Knowledge-based software solutions predict DNA secondary structures and hybridization properties, enabling rational design of multiplex assays and anticipating unwanted interactions before experimental validation [32].

- Data Integration: Combined knowledge-based and data-driven approaches create end-to-end frameworks that streamline assay design and improve target detection accuracy in the multiplex setting [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for qPCR validation studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from various sample types | TRIzol LS reagent, AllPrep DNA/RNA kits [8] [19] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System [8] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, buffers, and dNTPs for amplification | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix [8] [5] |

| Pre-designed Assays | Validated primer-probe sets for specific gene targets | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [5] |

| Custom Assay Design Tools | Bioinformatics support for designing specific assays | RealTimeDesign software, TaqMan Custom Assay Design Tool [30] [5] |

| High-Throughput Platforms | Format options for large-scale validation studies | TaqMan Array Cards, OpenArray Plates [5] |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessment of RNA and DNA quality | NanoDrop, Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer [19] |

qPCR remains an indispensable technology for targeted validation of candidate genes identified through NGS discovery screens. While NGS provides unprecedented power for hypothesis generation across the entire transcriptome, qPCR offers distinct advantages for verification studies in expanded cohorts, including lower cost, faster turnaround, simpler workflows, and superior sensitivity for limited target numbers.

The strategic integration of both technologies creates a powerful framework for biomarker development, leveraging the discovery power of NGS with the precision and practicality of qPCR for validation. By implementing rigorous experimental designs, standardized protocols, and comprehensive data analysis strategies, researchers can effectively translate NGS discoveries into clinically applicable biomarkers with strong statistical support. This complementary approach ensures that gene expression signatures identified through broad discovery screens can be reliably confirmed in larger cohorts, ultimately advancing drug development and personalized medicine initiatives.

In chemogenomic research aimed at validating gene expression changes, the debate is not about next-generation sequencing (NGS) versus quantitative PCR (qPCR), but rather how these technologies can be strategically integrated to maximize both discovery power and validation rigor. While NGS provides an unbiased, hypothesis-free approach for transcriptome-wide discovery, qPCR delivers targeted, highly sensitive confirmation of specific expression changes [1] [5]. This sequential pipeline leverages the unique strengths of each technology, beginning with broad exploratory capability and culminating in precise, reproducible quantification of candidate genes.

The synergy between these methods addresses a critical need in drug development: the requirement for both comprehensive discovery and highly reliable validation of transcriptional biomarkers. As research increasingly moves toward clinical translation, establishing workflows that ensure data accuracy while managing resource constraints becomes paramount. This guide examines the experimental evidence, technical protocols, and practical considerations for implementing an integrated NGS-to-qPCR pipeline that enhances workflow efficiency and data confidence in chemogenomic studies.

Technology Comparison: Distinct Strengths and Applications

Key Characteristics of NGS and qPCR

| Feature | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Power | High - detects novel transcripts, isoforms, and variants [1] | Limited to known, predefined targets [1] |

| Throughput | High - profiles thousands of targets across multiple samples simultaneously [1] | Low to moderate - best for ≤20 targets; workflow becomes cumbersome for multiple targets [1] |

| Quantification | Absolute, based on read counts [1] | Relative or absolute, based on quantification cycle (Cq) [14] |

| Sensitivity | Detects gene expression changes down to 10%; can identify rare variants [1] | Excellent for low-copy transcripts; can detect rare variants (<1% allelic frequency) [33] |

| Sample-to-Answer Time | Longer (library prep: hours to days; sequencing: hours to days) [14] | Rapid (1-3 hours) [14] |

| Cost Per Sample | Higher [14] | Lower [14] |

| Best Applications | Discovery-driven research, novel transcript identification, comprehensive profiling [1] | Targeted validation, high-throughput screening of known targets, clinical diagnostics [1] [14] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison in Validation Studies