NGS vs Microarray for Chemical Perturbation Profiling: A 2025 Strategic Guide

Choosing between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and microarrays for chemical perturbation studies is a critical decision that impacts data quality, cost, and biological insights.

NGS vs Microarray for Chemical Perturbation Profiling: A 2025 Strategic Guide

Abstract

Choosing between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and microarrays for chemical perturbation studies is a critical decision that impacts data quality, cost, and biological insights. This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical troubleshooting. It synthesizes recent evidence showing that while NGS offers a wider dynamic range and detects novel transcripts, microarrays remain a robust, cost-effective alternative for pathway analysis and benchmark concentration modeling. The guide concludes with a forward-looking perspective on integrating these technologies to advance toxicogenomics and precision medicine.

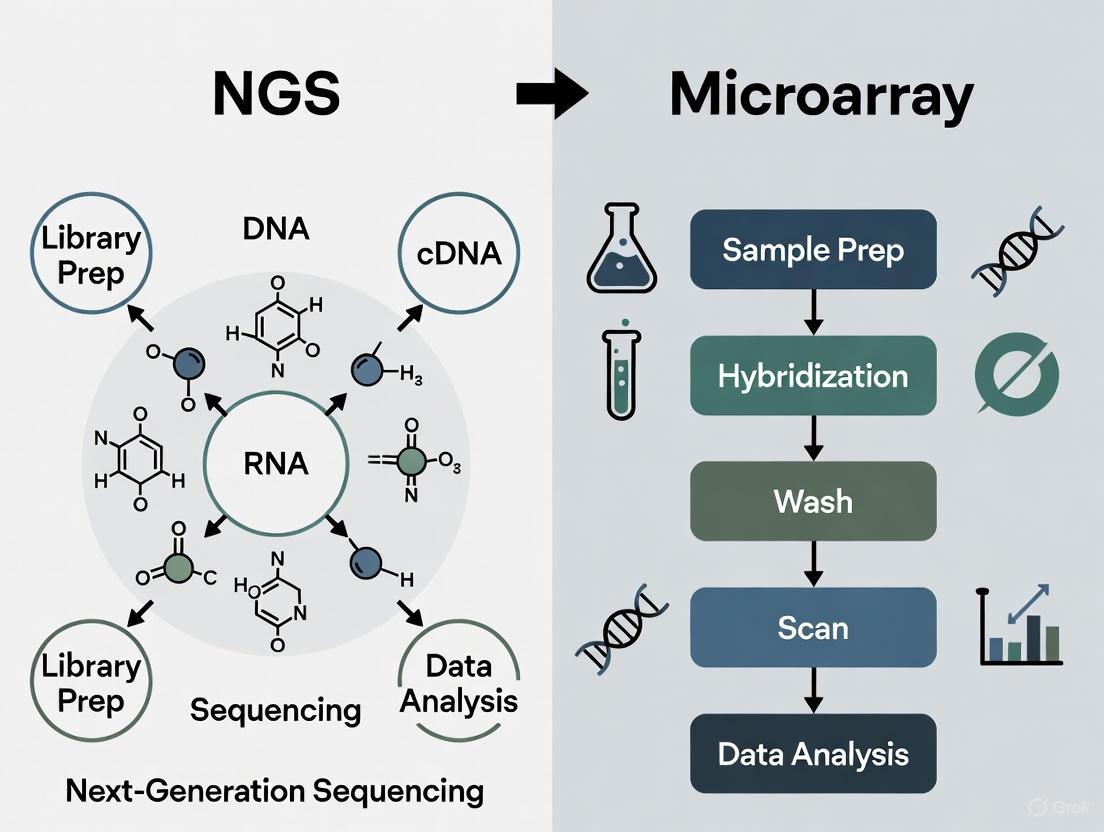

Core Technologies Unveiled: The Fundamental Principles of NGS and Microarray

The field of transcriptomics has undergone a profound transformation over the past two decades, moving decisively from hybridization-based methods to sequencing-driven approaches. This evolution represents more than just a technological upgrade; it signifies a fundamental shift in how researchers quantify and understand gene expression. Microarray technology, which dominated the field for over a decade, operates on a hybridization-based principle using fluorescence intensity of predefined transcripts [1]. While offering relatively simple sample preparation and lower per-sample cost, this method suffers from inherent limitations including limited dynamic range, high background noise, and an inability to detect transcripts beyond those pre-designed on the array [1] [2].

The mid-2000s witnessed the emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) as a powerful alternative. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) leverages massively parallel sequencing technology to determine the order of nucleotides in entire transcriptomes or targeted regions of RNA [3]. This shift from a "closed" to an "open" architecture system has enabled researchers to ask and answer biological questions with unprecedented depth and precision [2]. The technology generates discrete, digital sequencing read counts, providing a broader dynamic range and eliminating signal saturation issues that plague microarray platforms [4]. This technological evolution has fundamentally expanded the scope of biological inquiry, allowing scientists to rapidly sequence whole genomes, discover novel RNA variants, analyze epigenetic factors, and study complex biological systems at a resolution never before possible [3].

Technology Comparison: Core Methodologies and Capabilities

Fundamental Technological Principles

The operational dichotomy between microarrays and RNA-Seq begins at the most fundamental level of their detection methodologies. Microarrays function through a hybridization-based approach where fluorescently labeled complementary RNA (cRNA) is generated from sample RNA and hybridized to predefined probes arrayed on a glass slide [1]. The resulting fluorescence intensity provides a relative measure of gene expression, constrained by physical properties of the hybridization process including background fluorescence and signal saturation [1] [4]. This closed architecture requires a priori knowledge of the genome, limiting discovery to previously annotated transcripts [5].

In stark contrast, RNA-Seq employs a sequencing-by-synthesis approach that directly determines nucleotide sequences through detection of incorporated fluorescently-labeled nucleotides [3]. This methodology transforms analog expression signals into digital read counts, creating a direct correspondence between transcript abundance and sequencing depth [4]. As an open architecture system, RNA-Seq requires no pre-specified probes, enabling discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants, gene fusions, and non-coding RNAs without prior knowledge of their existence [1] [4]. This fundamental difference in operation underpins the significant advantages RNA-Seq offers in sensitivity, dynamic range, and discovery potential.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies reveal substantial differences in performance characteristics between these technological platforms. When assessing sensitivity and dynamic range, RNA-Seq demonstrates a clear advantage, with a dynamic range exceeding 10⁵ compared to approximately 10³ for microarrays [4]. This translates to practical experimental benefits, as RNA-Seq can simultaneously detect both rare and highly abundant transcripts without signal saturation at the high end or loss in background noise at the low end [5] [4].

A landmark 2014 comparison study of activated T cells found that RNA-Seq provided higher specificity and sensitivity, enabling detection of a higher percentage of differentially expressed genes, particularly those with low expression [4]. The technology also demonstrated superior ability to identify novel transcripts and splice variants that were completely undetectable by microarray analysis [4].

However, a 2025 updated comparison study using cannabinoids as case studies revealed a more nuanced picture. While RNA-Seq identified larger numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with wider dynamic ranges, including various non-coding RNA transcripts, both platforms displayed equivalent performance in identifying functions and pathways impacted by compound exposure through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [1]. Furthermore, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived through benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling were statistically indistinguishable between platforms for both cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN) [1]. This suggests that for traditional transcriptomic applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration response modeling, microarrays remain a viable option, particularly when considering their lower cost, smaller data size, and better availability of software and public databases for analysis [1].

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Microarray and RNA-Seq Technologies

| Feature | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-by-synthesis |

| Throughput | Moderate | Ultra-high throughput |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ [4] | >10⁵ [4] |

| Background Noise | High [1] | Low |

| Detection Capabilities | Predefined transcripts only | Novel transcripts, splice variants, gene fusions, non-coding RNAs [1] [4] |

| Quantitative Nature | Analog fluorescence intensity | Digital read counts [4] |

| A Priori Knowledge Required | Yes [5] | No |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [1] | Higher |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Established tools and databases [1] [5] | More complex, requires bioinformatics expertise |

| Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Transcripts | Limited [5] [4] | High [4] [6] |

Table 2: Experimental Findings from Direct Comparison Studies

| Study Focus | Microarray Performance | RNA-Seq Performance | Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated T Cells [4] | Limited dynamic range, signal saturation issues | Higher specificity/sensitivity, broader dynamic range | Moderate for known transcripts |

| Cannabinoid Exposure [1] | Identified key pathways and tPoD values | Identified more DEGs, non-coding RNAs | High for pathway identification and tPoD values |

| Differential Expression Detection [4] | Lower sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts | Higher percentage of DEGs detected, especially low-expression | Dependent on transcript abundance |

| Novel Transcript Discovery [1] [4] | Unable to detect novel features | Comprehensive discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants | Not applicable |

Experimental Protocols: From Sample to Data

Microarray Experimental Workflow

The microarray workflow begins with total RNA extraction from biological samples, followed by a series of enzymatic reactions to generate biotin-labeled complementary RNA (cRNA). As detailed in cannabinol (CBN) exposure studies, this process typically involves generating single-stranded cDNA from 100 ng total RNA using reverse transcriptase and a T7-linked oligo(dT) primer, which is then converted to double-stranded cDNA [1]. Subsequently, cRNA is synthesized through in vitro transcription (IVT) with biotinylated UTP and CTP, using T7 RNA polymerase [1]. The biotin-labeled cRNA is fragmented and hybridized onto microarray chips, which are then stained, washed, and scanned to produce image files that are processed into cell intensity (CEL) files [1]. The robust multi-chip average (RMA) algorithm is commonly used for background adjustment, quantile normalization, and summarization of normalized expression data for each probe set on a log2 scale [1].

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

The RNA-Seq workflow shares the initial RNA extraction step but diverges significantly in subsequent processes. For sequencing library preparation, the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit is commonly employed, beginning with purification of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) with polyA tails from 100 ng of total RNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads [1]. The purified mRNA is then fragmented and converted to cDNA, followed by adapter ligation and potential amplification to create the final sequencing library [3]. These libraries are loaded onto flow cells where cluster generation occurs, amplifying single molecules to create thousands of identical copies for sequencing [3]. The actual sequencing employs sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry, which tracks the addition of fluorescently-labeled nucleotides as the DNA chain is copied in a massively parallel fashion [3]. The resulting sequences are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome for quantification and analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Transcriptomics

| Item | Function | Example Products/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Microarrays | Pre-designed arrays for targeted transcript detection | GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays [1] |

| NGS Platforms | Massively parallel sequencing instruments | Illumina NovaSeq, MiSeq; PacBio SMRT; Oxford Nanopore [7] [3] |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare RNA samples for sequencing | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep; Ion Torrent Transcriptome Sequencing kits [1] [6] |

| RNA Extraction & Purification Kits | Isolate high-quality RNA from samples | EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit; QIAshredder [1] |

| Hybridization & Staining Reagents | Process microarrays for detection | GeneChip Hybridization, Wash, and Stain Kits [1] |

| Data Analysis Software | Process, normalize, and analyze transcriptomic data | Affymetrix TAC; JMP Genomics; IPA; BaseSpace [1] [5] [3] |

Application in Chemical Perturbation Profiling

Case Study: Cannabinoid Exposure Research

The application of transcriptomic technologies in chemical perturbation profiling is well illustrated by recent research on cannabinoids. A 2025 study directly compared microarray and RNA-Seq platforms using two cannabinoids—cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN)—as case studies [1]. The experimental design exposed iPSC-derived hepatocytes to varying concentrations of each cannabinoid for 24 hours, with subsequent transcriptomic analysis performed using both platforms on the same biological samples [1]. This rigorous approach enabled direct comparison of platform performance in identifying functions and pathways impacted by compound exposure.

Both technologies successfully revealed similar overall gene expression patterns with regard to concentration for both CBC and CBN [1]. Despite RNA-Seq identifying a larger number of differentially expressed genes with wider dynamic ranges, including various non-coding RNA transcripts unavailable to microarray analysis, the platforms demonstrated equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [1]. Most notably, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived through benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling showed no statistically significant differences between platforms for both compounds [1]. This finding has substantial implications for regulatory risk assessment, suggesting that for quantitative toxicogenomic applications, both technologies can provide equivalent points of departure for data-poor chemicals.

Analysis Pathways for Chemical Perturbation Studies

Implementation Considerations for Research Programs

Decision Framework for Technology Selection

Choosing between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies requires careful consideration of multiple factors specific to each research program. For established model organisms with comprehensive genomic annotations, where the research question focuses on known transcripts and the study design involves high sample throughput, microarrays offer significant advantages in cost-effectiveness and analytical simplicity [1] [5]. The technology benefits from decades of methodological refinement, with well-established normalization techniques and user-friendly analysis software that reduces the bioinformatics burden [5].

In contrast, RNA-Seq becomes the preferred option for non-model organisms, discovery-oriented research, and studies requiring detection of novel transcript features [5] [4]. The technology's ability to profile transcriptomes without a priori knowledge makes it indispensable for exploratory investigations and applications requiring the highest sensitivity [4]. However, researchers must be prepared for the bioinformatics challenges associated with RNA-Seq, including substantial data storage requirements, computational processing needs, and the need for specialized analytical expertise [5] [2].

Hybrid Approaches and Future Directions

Increasingly, researchers are adopting hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both technologies. One effective strategy involves using RNA-Seq for initial discovery phases to identify novel transcripts and biomarkers, followed by development of targeted microarrays for high-throughput screening applications [5]. This approach was successfully demonstrated in ecotoxicity testing on Chironomus riparius, where researchers used initial RNA-Seq data to create a microarray for routine monitoring [5]. This synergistic combination allows for both comprehensive discovery and cost-effective large-scale application.

The field continues to evolve with emerging methodologies that push transcriptomic analysis to higher resolution. Single-cell RNA sequencing is enabling researchers to move beyond bulk tissue analysis to examine transcriptomic responses at cellular resolution, revealing heterogeneity in chemical responses within seemingly uniform cell populations [8]. Similarly, spatial transcriptomics technologies are beginning to preserve geographical information within tissues, allowing researchers to map chemical effects within the architectural context of organs and tissue structures [8] [9]. These advances, combined with decreasing sequencing costs and improved computational methods, suggest that the transition to sequencing-based approaches will continue, while microarrays maintain their niche in targeted applications where their cost-effectiveness and analytical simplicity provide distinct advantages.

The evolution from hybridization-based microarrays to sequencing-driven RNA-Seq represents a paradigm shift in transcriptomics that has fundamentally expanded research capabilities. While RNA-Seq offers clear advantages in detection range, sensitivity, and discovery potential for novel transcripts, microarray technology maintains relevance for targeted applications where cost-effectiveness and analytical simplicity are paramount [1]. For chemical perturbation profiling specifically, both technologies can generate equivalent results for key endpoints including pathway analysis and benchmark concentration modeling [1]. The choice between platforms should be guided by specific research objectives, organism familiarity, discovery requirements, and resource constraints. As transcriptomics continues evolving toward single-cell and spatial resolutions, the integration of these complementary technologies will further empower researchers to unravel the complex molecular responses to chemical perturbations, advancing both basic science and regulatory decision-making.

In the field of chemical perturbation profiling research, scientists increasingly face a critical choice between established and emerging technologies for transcriptome analysis. Two platforms dominate this landscape: microarrays, the established workhorse relying on fluorescence-based hybridization to predefined transcripts, and RNA-Seq (Next-Generation Sequencing), the disruptive technology that enables direct, hypothesis-free sequencing of the entire transcriptome. Understanding the fundamental workings of microarrays—their strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications—is essential for designing effective toxicogenomic studies and accurately interpreting the resulting data. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, supported by experimental data, to inform decision-making for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Technology: The Microarray Method

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Gene expression microarrays function on the principle of complementary hybridization between immobilized probe sequences and fluorescently-labeled target transcripts. The technology provides a high-throughput method for quantifying the expression levels of thousands of predefined transcripts simultaneously [10].

A typical modern microarray consists of short oligonucleotide probes complementary to transcripts of interest, immobilized on a solid substrate [10]. Probe design is typically based on known genome sequences or predicted open reading frames, with multiple probes often designed per gene model to improve accuracy and reliability [10].

Table: Key Steps in a Microarray Experiment

| Step | Process Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Probe Design | Oligonucleotides designed based on genomic sequences | Dependent on prior genomic knowledge; limited to annotated regions |

| 2. Sample Preparation | RNA extraction, purification, and fluorescent labeling | RNA quality (RIN ≥9) critical; may involve amplification |

| 3. Hybridization | Labeled transcripts bind to complementary probes on array | Stringency controls minimize cross-hybridization; typically 16-24 hours |

| 4. Washing & Scanning | Removal of non-specific binding; laser excitation of dyes | Eliminates background noise; captures fluorescence intensity |

| 5. Data Acquisition | Fluorescence intensity measured for each probe | Intensity correlates with expression level; specialized scanners required |

The process begins with transcript extraction from cells or tissues, followed by labeling with fluorescent dyes (either one-color or two-color approaches) [10]. The labeled transcripts are then hybridized to the arrays, washed to remove non-specifically bound material, and scanned with a laser [10]. Probes that correspond to transcribed RNA hybridize to their complementary targets, with light intensity serving as the quantitative measure of gene expression [10].

Visualization: Microarray Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete microarray experimental workflow, from probe design to data interpretation:

Comparative Analysis: Microarrays vs. RNA-Seq

Technical and Performance Comparison

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance of microarray and RNA-Seq platforms for transcriptomic analysis. The table below summarizes key comparative findings from experimental studies:

Table: Experimental Comparison of Microarray and RNA-Seq Performance

| Parameter | Microarray | RNA-Seq | Experimental Context & Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Limited [1] | Wider [1] [11] | RNA-Seq provides higher precision and wider dynamic range [1] |

| DEG Detection | Fewer DEGs typically identified [11] | More DEGs, including non-coding RNAs [1] [11] | RNA-Seq identified more differentially expressed protein-coding genes [11] |

| Platform Concordance | ~78% overlap with RNA-Seq DEGs [11] | High correlation with microarray (Spearman's 0.7-0.83) [11] | Both platforms detected similar pathway perturbations despite DEG differences [11] |

| Alternative Splicing | Requires specialized junction arrays [10] | Direct detection of splice junctions [10] | RNA-Seq enables identification of transcript isoforms without prior knowledge [10] |

| Species Flexibility | Limited to species with known sequences [10] | Can be used on species without full genome [10] | Microarrays require species-specific design or cross-species hybridization [10] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$100 [10] | ~$1,000 [10] | Microarrays offer significant cost advantage for large studies [10] |

Practical Considerations for Research Applications

Beyond technical specifications, practical considerations significantly impact platform selection for chemical perturbation studies:

Table: Practical Implementation Factors

| Factor | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Data Maturity | Well-understood biases; stable analytical solutions [10] | Evolving standards; biases still being researched [10] |

| Sample Throughput | High-throughput; streamlined workflows [1] | Moderate throughput; more complex preparation [12] |

| Infrastructure Needs | Standard computing resources [1] | Extensive computational resources needed [11] |

| Data Interpretation | Established pipelines and databases [1] | Complex bioinformatics; longer analysis times [11] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established for toxicogenomics [11] | Growing acceptance; expanding databases [11] |

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that despite their technological differences, both platforms can produce biologically concordant results. A 2024 study found that "despite some degree of discordance between the two platforms found during data analysis, very similar final results, i.e., impacted functional pathways and transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values, were obtained by the two platforms" [1]. This suggests that for many traditional transcriptomic applications, microarrays remain a viable and cost-effective option.

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in Toxicogenomics

Hepatotoxicity Study

A comprehensive comparison study examined liver samples from rats treated with five hepatotoxicants using both platforms [11]. The research demonstrated that:

- Both platforms identified a larger number of DEGs in livers of rats treated with ANIT, MDA, and CCl4 compared to APAP and DCLF, correlating with histopathological findings [11]

- Consistent with established mechanisms of toxicity, both platforms detected dysregulation of key liver-relevant pathways including Nrf2, cholesterol biosynthesis, eiF2, hepatic cholestasis, glutathione, and LPS/IL-1 mediated RXR inhibition [11]

- RNA-Seq data enriched these pathways with additional DEGs and suggested modulation of additional liver-relevant pathways [11]

- RNA-Seq enabled identification of non-coding DEGs offering potential for improved mechanistic clarity [11]

Cannabinoid Profiling Study

A 2025 investigation compared microarray and RNA-Seq platforms using two cannabinoids (CBC and CBN) as case studies [1]. The experimental protocol included:

- Cell Culture: Commercial iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) cultured following manufacturer's protocol [1]

- Exposure: Cells exposed to varying concentrations of cannabinoids in triplicate for 24 hours [1]

- RNA Preparation: Total RNA purified using EZ1 Advanced XL automated instrument with DNase digestion [1]

- Quality Control: RNA concentration/purity measured by NanoDrop; quality checked by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer for RIN [1]

- Microarray Processing: Samples processed using GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit and hybridized to GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays [1]

- Data Generation: Arrays scanned using GeneChip Scanner 3000; CEL files processed with Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console using RMA algorithm [1]

The study concluded that "considering the relatively low cost, smaller data size, and better availability of software and public databases for data analysis and interpretation, microarray is still a viable method of choice for traditional transcriptomic applications such as mechanistic pathway identification and concentration response modeling" [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microarray Experiments

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| iCell Hepatocytes 2.0 (FUJIFILM) | Biologically relevant in vitro model | iPSC-derived; maintain hepatocyte functionality [1] |

| EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Total RNA purification | Automated purification with DNase digestion step [1] |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | RNA quality assessment | Determines RNA Integrity Number (RIN); essential for QC [1] |

| GeneChip PrimeView Arrays (Affymetrix) | Gene expression profiling | Predefined transcript coverage; consistent performance [1] |

| GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Kit (Affymetrix) | Target preparation | Includes reverse transcription, IVT, and labeling [1] |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit (Illumina) | RNA-Seq library prep | Comparison methodology; enriches coding mRNAs [11] |

Decision Framework: Platform Selection Guide

The choice between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies depends on multiple factors, which can be visualized through the following decision pathway:

Microarray technology, based on fluorescence-based hybridization to predefined transcripts, remains a valuable and reliable platform for transcriptomic analysis in chemical perturbation profiling research. While RNA-Seq offers advantages in detecting novel transcripts and providing a wider dynamic range, microarrays provide a cost-effective, well-established alternative with mature analytical frameworks [10] [1]. The experimental evidence demonstrates that for many applications—including mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling—microarrays produce results functionally equivalent to RNA-Seq in terms of biological interpretation [1] [11]. The choice between platforms should be guided by specific research objectives, budgetary constraints, and the need for novel transcript discovery versus focused hypothesis testing.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research by providing powerful tools to investigate biological systems. For researchers studying chemical perturbation profiling—analyzing how cells respond to drugs or chemical compounds—understanding the core technological advantages of NGS compared to traditional microarray platforms is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation. This guide explores the fundamental principles of sequencing-by-synthesis and massive parallel sequencing, objectively comparing NGS performance against microarrays for toxicogenomic and chemical perturbation applications.

Principles of NGS Technology

Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) Chemistry

Sequencing-by-Synthesis forms the foundation of modern NGS platforms. Unlike the Sanger chain-termination method, SBS technology involves tracking the addition of fluorescently-labeled nucleotides as the DNA chain is copied in a cyclical process [3]. The core SBS process consists of repeated steps: polymerase-based extension using reversible terminator nucleotides, fluorescence imaging to identify the incorporated base, and chemical cleavage to remove the terminating group and fluorescent dye, preparing the template for the next incorporation cycle [13].

This reversible termination chemistry enables highly accurate base determination across millions of parallel reactions. Recent innovations like XLEAP-SBS chemistry have further increased sequencing speed and fidelity compared to standard Illumina SBS chemistry [3].

Massive Parallel Sequencing

Massive parallel sequencing refers to the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments in a single run [14]. This is achieved through clonal amplification of individual DNA fragments either on a solid surface (bridge amplification) or in emulsion droplets (emulsion PCR), creating clusters of identical DNA templates that generate sufficient signal for detection during sequencing [13].

The extraordinary throughput of massive parallel sequencing enables researchers to rapidly sequence whole genomes, deeply sequence target regions, and perform complex transcriptomic analyses that would be impractical with traditional methods [3]. Modern Illumina systems can generate data output ranging from 300 kilobases up to multiple terabases in a single run, depending on the instrument type and configuration [3].

NGS Versus Microarrays: Technical Comparison

The table below summarizes the core technical differences between NGS and microarray technologies for chemical perturbation studies:

| Feature | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Microarray |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Sequencing-by-synthesis via reversible terminator chemistry [13] | Fluorescence-based hybridization to predefined probes [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Orders of magnitude greater; digital counting of reads enables detection across wide expression levels [5] [3] | Limited; suffers from signal saturation at high expression levels and background noise at low levels [1] [5] |

| Transcript Discovery | Capable of detecting novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs without prior knowledge [1] [5] | Limited to predefined probes; cannot detect sequences not represented on the array [1] |

| Required A Priori Knowledge | Not required; can profile organisms with unsequenced genomes [5] | Extensive knowledge needed for probe design [5] |

| Background Noise | Low background signal [1] | High background noise due to nonspecific binding [1] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher per-sample cost; decreasing over time [5] | Lower per-sample cost; established economical option [1] |

Experimental Evidence: Performance Comparison in Chemical Perturbation Studies

Recent research directly compares these platforms for chemical perturbation profiling. A 2025 study examined two cannabinoids (cannabichromene and cannabinol) using both RNA-seq and microarrays, providing quantitative performance data [1].

Experimental Protocol

The comparative study followed this methodology [1]:

- Cell Culture: Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) cultured in 24-well plates

- Chemical Exposure: Cells exposed to varying concentrations of CBC and CBN for 24 hours in triplicate

- RNA Extraction: Total RNA purified using EZ1 Advanced XL automated instrument with DNase digestion

- Platform-Specific Processing:

- Microarray: GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays with 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit

- RNA-seq: Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit for library preparation

- Data Analysis: Differential expression analysis followed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key findings from the cannabinoid perturbation study:

| Performance Metric | RNA-seq Results | Microarray Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | Larger numbers of DEGs identified with wider dynamic range [1] | Fewer DEGs detected [1] | RNA-seq more sensitive in DEG detection |

| Functional Pathway Identification | Equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways through GSEA [1] | Equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways through GSEA [1] | Both platforms equivalent for functional analysis |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) | tPoD values on the same level for both cannabinoids [1] | tPoD values on the same level for both cannabinoids [1] | Both platforms equivalent for concentration-response modeling |

| Novel Transcript Detection | Detected non-coding RNAs (miRNA, lncRNA) and novel transcripts [1] | Limited to predefined probeset [1] | RNA-seq superior for novel biomarker discovery |

Despite RNA-seq's technical advantages in detecting more DEGs with wider dynamic range, both platforms produced equivalent results for the endpoints most relevant to chemical risk assessment: identification of impacted functional pathways and transcriptomic point of departure values [1]. This suggests that for traditional toxicogenomic applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling, microarrays remain a viable option, particularly considering their lower cost, smaller data size, and better availability of analysis software and databases [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key reagents and materials essential for implementing NGS and microarray protocols in chemical perturbation studies:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived hepatocytes (e.g., iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) | Physiologically relevant in vitro model for chemical exposure studies [1] | Preferred over cancer cell lines for non-cancer chemical perturbation research [15] |

| Stranded mRNA Prep Kit (Illumina) | Library preparation for RNA-seq; preserves strand orientation [1] | Essential for accurate transcript annotation and quantification |

| GeneChip PrimeView Array (Affymetrix) | Microarray-based gene expression profiling [1] | Established platform with well-annotated databases |

| EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Automated RNA purification with genomic DNA removal [1] | Critical for obtaining high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) for both platforms |

| Poly-A Selection Beads | mRNA enrichment for RNA-seq library prep [1] | Reduces ribosomal RNA contamination |

| Reversible Terminator Nucleotides | Core SBS chemistry for base identification [13] | XLEAP-SBS chemistry offers improved fidelity [3] |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

NGS Sequencing-by-Synthesis Workflow

Chemical Perturbation Transcriptomics Pathway

The choice between NGS and microarray technologies for chemical perturbation profiling depends on specific research objectives and resource constraints. NGS technologies, with their sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry and massive parallel sequencing capabilities, offer clear technical advantages for discovery-based research where novel transcript detection, broader dynamic range, and absence of pre-existing genomic knowledge are primary considerations [5] [3]. However, recent evidence demonstrates that microarray platforms remain competitive for traditional toxicogenomic applications, providing equivalent performance in functional pathway analysis and concentration-response modeling at lower cost and with less computational overhead [1].

For comprehensive chemical perturbation studies that require novel biomarker discovery or detection of non-coding RNAs, NGS is unquestionably superior. However, for well-defined hypothesis testing within annotated genomes, microarrays provide a cost-effective and analytically tractable alternative. The emerging trend of combining both approaches—using NGS for initial discovery and microarrays for routine screening—represents a pragmatic strategy that leverages the respective strengths of both platforms [5].

In the field of chemical perturbation profiling, researchers face a critical decision when selecting a genomic tool: next-generation sequencing (NGS) or microarray technology. Each platform possesses distinct technical characteristics that directly impact data quality and biological interpretation. For research aimed at understanding the mechanisms of action of chemical compounds, the choices between these technologies influence everything from experimental design to the validation of findings. This guide provides an objective comparison of three fundamental performance parameters—dynamic range, background noise, and specificity—between NGS and microarrays, drawing on experimental data to inform selection for toxicogenomics and drug development studies.

The core distinction between these platforms lies in their underlying biochemistry. Microarrays are a closed-architecture system that relies on the hybridization of fluorescently-labeled nucleic acids to predefined probes immobilized on a solid surface [16]. The signal intensity measured at each probe provides a relative quantification of the target sequence. In contrast, next-generation sequencing (NGS) is an open-architecture system that uses massively parallel sequencing-by-synthesis to directly determine the nucleotide sequence of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [3]. This fundamental difference—indirect hybridization versus direct sequencing—is the origin of their performance distinctions.

Direct Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key technological distinctions between NGS and microarrays based on experimental comparisons.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Microarray and NGS Platforms

| Performance Metric | Microarray | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Limited by signal saturation at high end and background noise at low end [3]. | Broader, digital counting of reads enables quantification across a wider concentration range [3]. |

| Background Noise | Susceptible to high background noise from nonspecific binding [1] [17]. | Lower background; noise primarily from sequencing errors or PCR duplicates [7]. |

| Specificity | Challenged by cross-hybridization between related sequences; difficult to distinguish paralogs or splice variants [18] [17]. | High specificity; can uniquely map reads to their genomic origin, identifying splice sites and single-nucleotide differences [3]. |

| Data Type | Relative, analog-like fluorescence intensity. | Digital, countable read counts. |

| Optimal Application | Profiling known transcripts; studies where cost-effectiveness and sample throughput are priorities [1]. | Discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs; quantifying rare transcripts [1] [7]. |

Experimental data reinforces these distinctions. A 2025 toxicogenomics study comparing the same cannabinoid samples on both platforms noted that RNA-seq identified larger numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a wider dynamic range, consistent with its digital, counting-based nature [1]. In a separate investigation, the specificity of microarrays was compromised by cross-hybridization, a phenomenon where a probe binds to non-target sequences with high similarity, such as closely related members of a miRNA family [18].

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

To ensure valid and reproducible comparisons between NGS and microarray technologies, a rigorous experimental protocol is essential.

Sample Preparation and Core Methodology

The foundational step for a fair comparison is using the same high-quality RNA sample for both platforms. RNA integrity should be verified using methods like microfluidic electrophoresis to obtain an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [17] [19].

- Microarray Workflow: The protocol generally involves reverse transcribing RNA into cDNA, followed by in vitro transcription to produce biotin-labeled cRNA. This labeled cRNA is fragmented and hybridized to the microarray chip. After washing, the chip is scanned to produce fluorescence intensity data (DAT files), which are converted into cell intensity (CEL) files for analysis [1] [17].

- NGS Workflow (RNA-Seq): The library preparation starts by isolating and fragmenting RNA. Fragments are reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and platform-specific adapters are ligated to the ends. These libraries are then quantified and loaded onto a sequencer. In Illumina systems, fragments undergo clonal amplification on a flow cell, followed by sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators [3] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical workflows for each technology.

Data Analysis and Validation

- Microarray Data Processing: Raw intensity files require significant pre-processing, including background correction, normalization (e.g., Robust Multi-array Average - RMA), and summarization to generate expression values for each probe set [1] [17].

- NGS Data Processing: The primary data analysis involves base calling, demultiplexing, and quality control. Reads are then aligned to a reference genome, and gene expression is quantified by counting the number of reads mapped to each gene [19].

- Validation: A common practice is to validate key findings using an orthogonal method, such as real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for a subset of genes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of a chemical perturbation study requires specific reagents and tools for both platforms.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Perturbation Profiling

| Item | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Total RNA | Starting material for both library prep (NGS) and labeling (microarray). | Assess yield, purity (A260/280), and integrity (RIN > 8) [17] [19]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares RNA/DNA fragments for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters. | Select based on application (e.g., mRNA-seq, total RNA-seq), input amount, and workflow simplicity [19]. |

| Microarray Platform | Pre-manufactured slide or chip with immobilized probes for hybridization. | Choose a platform with comprehensive and up-to-date gene coverage for your organism of interest [18] [17]. |

| qPCR Reagents | For orthogonal validation of differentially expressed genes identified by NGS or microarray. | Enables high-sensitivity and high-specificity confirmation of expression changes [18]. |

| Cell Painting Assay Reagents | For complementary morphological profiling; includes fluorescent dyes for staining cellular components. | Used to connect transcriptional changes with phenotypic outcomes in chemical perturbation studies [20]. |

Implications for Chemical Perturbation Research

The choice between NGS and microarray has direct consequences for interpreting chemical perturbation experiments.

- Mechanism of Action (MoA) Elucidation: NGS is superior for de novo discovery, as it can reveal novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs affected by a compound, providing a more complete picture of its MoA [7] [3]. Microarrays are confined to pre-defined transcripts.

- Toxicogenomics and Pathway Analysis: A 2025 study found that while NGS identified more DEGs, both platforms ultimately revealed similar enriched pathways and produced comparable transcriptomic points of departure (tPoD) in concentration-response modeling [1]. This suggests that for well-annotated pathways, microarrays remain a cost-effective option.

- Data Reproducability and Noise: Microarray data can be confounded by batch effects and cross-hybridization, requiring careful normalization and batch-effect correction [17] [21]. NGS data, while less prone to cross-hybridization, must be processed to account for sequencing artifacts and amplification biases [18] [7].

The relationship between data generation and biological insight in perturbation studies is summarized below.

The decision between NGS and microarray technology for chemical perturbation profiling is not one-size-fits-all. NGS offers clear technical advantages in dynamic range, specificity, and discovery power, making it the preferred tool for uncovering novel mechanisms and profiling complex transcriptomes. Microarrays, however, remain a viable and cost-effective option for focused studies where high sample throughput and well-established analytical pipelines are priorities, and where the target transcripts are well-annotated. The most appropriate technology depends on the specific research goals, budget, and bioinformatic capabilities of the project.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, bringing unparalleled capabilities to analyze DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [7]. This transformative technology has become particularly crucial for chemical perturbation profiling, a field that systematically studies how small molecules affect biological systems. Unlike traditional microarray technologies, which rely on hybridization to predefined probes, NGS-based methods offer higher precision, wider dynamic range, and the ability to detect novel transcripts and modifications without prior sequence knowledge [22]. The transition from microarray to NGS has enabled researchers to move beyond simple gene expression profiling to comprehensive mechanism-of-action studies for drug discovery, fundamentally changing how we approach chemical genomics and toxicogenomics.

NGS Technology Generations: Core Platforms and Specifications

The evolution of sequencing technologies has progressed through distinct generations, each overcoming limitations of its predecessors while introducing new capabilities essential for detailed perturbation studies.

Second-Generation Sequencing: The Short-Read Workhorse

Second-generation or short-read sequencing platforms remain the workhorses of most NGS laboratories, dominating applications requiring high accuracy and throughput at low cost [23]. These technologies share a common principle of massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments, typically ranging from 50-300 base pairs in length [7]. The Illumina platform, which accounts for the majority of the world's sequencing data, utilizes a sequencing-by-synthesis approach with reversible dye-terminators and bridge amplification on flow cells [7] [24]. Alternative short-read technologies like Ion Torrent employ semiconductor sequencing, detecting hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization rather than using optical methods [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Amplification Method | Read Length | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequencing-by-Synthesis | Bridge PCR | 36-300 bp | Extremely high throughput (16 Tb/run); Low error rate (<1%) [25] [26] | Limited read length; GC bias [27] |

| Ion Torrent Genexus | Semiconductor | Emulsion PCR | 200-600 bp | Rapid results (1 day); Simple workflow [26] | Homopolymer errors [7] |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T7 | DNA Nanoball | Nanoball PCR | 50-150 bp | Cost-effective; Competitive accuracy [7] [27] | Multiple PCR cycles required [7] |

| Element AVITI | Sequencing-by-Binding | Proprietary | Up to 300 bp | Q40 accuracy (1 error/10,000 bases) [24] | Emerging platform with smaller user base |

Third-Generation Sequencing: Long-Read Technologies

Third-generation sequencing technologies overcome the read length limitations of short-read platforms by sequencing single DNA molecules without amplification [7]. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) employs Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, where DNA polymerase incorporates fluorescently labeled nucleotides in real-time within nanoscale wells called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [7] [25]. The introduction of HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads circularizes DNA fragments, allowing multiple passes to generate reads of 10-25 kilobases with accuracy exceeding 99.9% (Q30) [25] [23].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) utilizes a fundamentally different approach, measuring changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [7]. Recent developments like the Q20+ and Q30 Duplex kits have significantly improved accuracy, with duplex reads exceeding Q30 (>99.9% accuracy) while maintaining the ability to generate ultra-long reads exceeding 100 kilobases [25] [24]. This technology uniquely enables direct detection of epigenetic modifications and requires minimal instrumentation, from pocket-sized MinION devices to high-throughput PromethION platforms [7] [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio Revio (HiFi) | SMRT Sequencing | 10-25 kb | >99.9% (Q30) | High accuracy; Uniform coverage [25] [23] | Higher cost per sample; Moderate throughput |

| Oxford Nanopore (Q30 Duplex) | Nanopore Sensing | 10-100+ kb | >99.9% (Q30) | Ultra-long reads; Direct epigenetic detection [25] | Higher DNA input requirements |

| PacBio Onso | Sequencing-by-Binding | 100-200 bp | Q40 | Exceptional accuracy (1 error/10,000 bases) [24] | Short-read platform |

Benchmarking NGS Performance for Chemical Genomics Applications

Technical Comparisons Across Platforms

Practical comparisons of NGS platforms reveal distinct performance characteristics critical for experimental design. A comprehensive evaluation of yeast genome assembly demonstrated that ONT reads generated more continuous assemblies than PacBio Sequel, though with persistent homopolymer-related errors [27]. The study further found Illumina NovaSeq 6000 provided more accurate assemblies in short-read-first pipelines, while MGI DNBSEQ-T7 offered a cost-effective alternative for polishing processes [27].

For transcriptomic applications, including chemical perturbation studies, RNA-seq demonstrates clear advantages over microarrays in detecting novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs with a wider dynamic range [22]. However, microarray technology remains competitive for traditional applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling, offering lower costs, smaller data sizes, and better-established analytical pipelines [22].

NGS in Chemical Perturbation Profiling: The PROSPECT Case Study

The application of NGS to chemical genomics is exemplified by the PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform for antibiotic discovery [28]. This methodology addresses a fundamental challenge in drug discovery—simultaneously identifying bioactive compounds and their mechanisms of action.

Experimental Protocol: PROSPECT Chemical-Genetic Profiling

Strain Pool Preparation: A pooled collection of hypomorphic Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants, each depleted of a different essential protein and tagged with unique DNA barcodes, is prepared [28].

Chemical Perturbation: The mutant pool is exposed to chemical compounds across a range of concentrations, with untreated controls maintained for comparison [28].

Selective Growth: Following incubation, genomic DNA is extracted from both treated and control pools. The relative abundance of each mutant strain is quantified by amplifying and sequencing the barcode regions using NGS [28].

Data Analysis: Chemical-genetic interaction (CGI) profiles are generated as vectors representing each hypomorph's sensitivity. The Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis then compares unknown compound profiles to a curated reference set of compounds with known mechanisms of action [28].

Figure 1: NGS-Based Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling Workflow. This diagram illustrates the PROSPECT platform workflow for elucidating small molecule mechanism of action through chemical-genetic interaction profiling [28].

This approach demonstrates how NGS transcends mere sequence detection to become a quantitative tool for measuring biological responses. In proof-of-concept validation, PCL analysis correctly predicted mechanism of action with 70% sensitivity and 75% precision in leave-one-out cross-validation, successfully identifying compounds targeting tuberculosis respiration [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Successful implementation of NGS-based chemical genomics requires specialized reagents and methodologies tailored to perturbation studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Chemical Genomics

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application in Perturbation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic Mutant Libraries | Collection of essential gene knockdown strains | Enables genome-wide sensitivity profiling; Key to PROSPECT platform [28] |

| DNA Barcode Systems | Unique sequence tags for each strain or perturbation | Allows pooled screening by tracking strain abundance via NGS [28] [29] |

| Stranded mRNA Prep Kits | Library preparation preserving strand information | Maintains transcriptional directionality in perturbation transcriptomics [22] |

| Transposase-Based Library Construction | Efficient fragmentation and tagging of DNA | Streamlines library prep for both short- and long-read sequencing [23] |

| Multiplexed Library Prep Technologies (e.g., purePlex, ExpressPlex) | Simultaneous processing of multiple samples | Enables large-scale chemical screening with normalized libraries [23] |

| Batch Effect Correction Methods (e.g., ComBat, TVN) | Statistical adjustment for technical variation | Critical for integrating data across multiple screens or laboratories [29] [30] |

Integrated Data Analysis: From Sequences to Biological Insights

The computational transformation of NGS data into biological insights requires sophisticated pipelines, particularly for perturbation studies where distinguishing true signals from background variation is crucial.

Perturbative Map Building with EFAAR Pipeline

Large-scale chemical and genetic perturbation data can be integrated into unified "maps of biology" using the EFAAR pipeline (Embedding, Filtering, Aligning, Aggregating, Relating) [29]. This framework processes high-dimensional data from various perturbation types (CRISPR knockout, chemical treatment) into comparable embedding spaces [29].

Embedding reduces high-dimensional assay data (e.g., 20,000 gene expression values or million-pixel images) to tractable numerical representations using methods like principal component analysis or neural networks [29]. Filtering removes low-quality perturbation units based on predefined criteria. Aligning applies batch effect correction methods like Typical Variation Normalization (TVN) or ComBat to remove technical artifacts [29]. Aggregating combines replicate measurements using statistical methods, while Relating computes similarity measures between perturbations to identify biological relationships [29].

Figure 2: EFAAR Computational Pipeline for Perturbative Map Building. This workflow transforms raw perturbation data into unified maps that capture biological relationships [29].

Advanced Algorithms for Chemical-Genetic Data

The Bucket Evaluations (BE) algorithm addresses specific challenges in chemical-genomic data analysis by using leveled rank comparisons to minimize batch effects without requiring prior knowledge of confounding variables [30]. This method divides each profile's gene scores into "buckets" - smaller buckets for the most significant genes (highest fitness defects) and larger buckets for less significant genes [30]. A weighted scoring system then identifies profile similarities, awarding higher scores to genes in corresponding high-significance buckets across experiments [30].

The NGS landscape continues to evolve with emerging technologies that promise to further transform chemical perturbation profiling. Multi-omics integration represents a key frontier, with platforms like PacBio's SPRQ chemistry simultaneously capturing DNA sequence and chromatin accessibility information from the same molecule [25]. Ultra-high accuracy sequencing is another trend, with platforms like Element AVITI and PacBio Onso achieving Q40 accuracy (1 error in 10,000 bases), enabling more confident detection of rare variants in heterogeneous samples [24].

The ongoing competition between short-read and long-read technologies has driven remarkable cost reductions, with the price of sequencing a human genome falling below $100, outpacing Moore's Law [24]. This increased affordability, combined with continuous improvements in accuracy and throughput, ensures that NGS will remain the foundational technology for chemical perturbation profiling and drug discovery.

While microarrays retain niche applications in standardized toxicogenomic testing due to their lower cost and simpler data analysis [22], NGS provides unparalleled versatility for discovering novel biological mechanisms. The choice between short-read and long-read technologies increasingly depends on specific application requirements rather than technical limitations, with many researchers adopting hybrid approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of both platforms [23] [27].

For chemical genomics research, this expanding NGS landscape offers unprecedented opportunities to elucidate mechanisms of action, identify novel therapeutic targets, and accelerate drug discovery through more informative early-stage screening. As sequencing technologies continue to converge and improve, they will undoubtedly uncover deeper insights into biological systems and their chemical perturbations.

Designing Your Profiling Study: Methodological Approaches and Practical Applications

In chemical perturbation profiling research, selecting the appropriate transcriptomic platform is crucial for generating reliable, biologically relevant data. The choice between microarray technology and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) represents a fundamental decision point that affects every subsequent stage of experimental workflow, data interpretation, and biological insight. While RNA-seq has increasingly become the dominant platform in modern transcriptomics, recent evidence suggests that microarrays remain surprisingly competitive for specific applications, particularly in studies focusing on pathway identification and concentration-response modeling [1].

This guide provides an objective comparison of sample preparation workflows for both platforms, focusing specifically on their application in chemical perturbation studies. We examine detailed experimental protocols, present quantitative performance data, and analyze the technical considerations researchers must evaluate when designing transcriptomic experiments for toxicogenomics and drug development applications.

The fundamental distinction between these platforms lies in their basic detection principles: microarrays utilize hybridization-based detection of predefined transcripts, while RNA-seq employs sequencing-by-synthesis to generate digital read counts [1] [4]. This core difference dictates substantial variations in their sample preparation requirements, data output, and analytical capabilities.

The following diagram illustrates the parallel workflows for both technologies, highlighting key decision points and procedural differences:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Microarray Sample Preparation Protocol

The microarray workflow employs a hybridization-based approach with fluorescent detection. The following protocol is adapted from toxicogenomic studies of cannabinoids (CBC and CBN) using iPSC-derived hepatocytes [1]:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate total RNA using silica-based membrane purification (e.g., EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit) with integrated DNase digestion to remove genomic DNA contamination. Assess RNA purity using UV spectrophotometry (260/280 ratio) and determine RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥7.0 using microfluidics-based analysis (e.g., Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) [1].

cDNA Synthesis and Amplification: Convert 100ng total RNA to double-stranded cDNA using reverse transcriptase with T7-linked oligo(dT) primers, followed by second-strand synthesis with DNA polymerase and RNase H. Perform in vitro transcription (IVT) using T7 RNA polymerase with biotin-labeled UTP and CTP to generate complementary RNA (cRNA) [1].

Fragmentation and Hybridization: Fragment 12μg of biotin-labeled cRNA using magnesium-induced cleavage (94°C). Hybridize to array (e.g., GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array) at 45°C for 16 hours in a specialized hybridization oven [1].

Washing, Staining, and Scanning: Perform automated washing and staining on a fluidics station using streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate. Scan arrays using a high-resolution scanner (e.g., GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G) to generate DAT image files, which are processed into CEL files using vendor software [1].

RNA-Seq Sample Preparation Protocol

RNA-seq employs a sequencing-based approach that captures digital expression data. The following protocol is adapted from parallel analysis of the same cannabinoid samples [1]:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Use identical RNA extraction and quality assessment procedures as the microarray protocol to ensure comparable starting material. The consistency in initial sample processing allows for direct platform comparisons [1].

Library Preparation: Process 100ng total RNA using Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation kit. Purify polyadenylated mRNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads. Fragment RNA and synthesize cDNA with random hexamer priming. Perform end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation for library construction [1] [31].

Library Quality Control and Normalization: Assess library quality using microfluidics-based systems (e.g., Bioanalyzer) and quantify using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit). Normalize libraries to equimolar concentrations for pooling and multiplexed sequencing [31].

Sequencing: Load pooled libraries onto an NGS platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq 2000) for cluster generation and sequencing-by-synthesis. Generate 50-100 million paired-end reads per sample (2×100bp configuration) to ensure sufficient coverage for transcript quantification [1].

Performance Comparison Data

Technical Capabilities and Limitations

Table 1: Technical comparison between microarray and RNA-seq platforms

| Parameter | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-based |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ [4] | >10⁵ [4] |

| Background Noise | High background due to nonspecific binding [1] | Low background |

| Sample Throughput | High [16] | Moderate [16] |

| Required RNA Input | 100ng [1] | 100ng [1] |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Limited to predefined probes [4] | Unlimited detection capability [4] |

| Variant Detection | Not available | SNP, splice variants, fusion genes [4] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited | High (with barcoding) |

| Startup Cost | Low | High |

| Cost per Sample | Low [5] | High [5] |

Experimental Outcomes in Chemical Perturbation Studies

Recent comparative studies using identical chemical perturbation samples reveal nuanced performance differences between the platforms:

Table 2: Experimental outcomes from comparative studies of cannabinoid perturbations

| Performance Metric | Microarray Results | RNA-Seq Results | Comparative Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes | 427 DEGs identified in HIV study [32] | 2,395 DEGs identified in HIV study [32] | RNA-seq detects 5.6× more DEGs |

| Pathway Identification | 47 perturbed pathways [32] | 205 perturbed pathways [32] | 30 pathways shared between platforms |

| Correlation with Protein Expression | Variable by gene; superior for BAX, PIK3CA [33] | Variable by gene; superior for others [33] | Platform performance gene-dependent |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) | Equivalent to RNA-seq [1] | Equivalent to microarray [1] | No significant difference in tPoD values |

| Gene Expression Correlation | Median Pearson R=0.76 with RNA-seq [32] | Median Pearson R=0.76 with microarray [32] | High correlation between platforms |

| Dynamic Fold Change Distribution | Similar distribution to RNA-seq [32] | Similar distribution to microarray [32] | No significant difference (KS test) |

Pathway Analysis and Bioinformatics

Functional analysis of chemical perturbation data reveals important similarities and differences between the platforms. The following diagram illustrates the bioinformatic workflow for pathway enrichment analysis from raw data through functional interpretation:

Despite detecting different numbers of differentially expressed genes, both platforms identify highly concordant biological pathways in chemical perturbation studies. Research comparing cannabinoid exposures found that "the two platforms displayed equivalent performance in identifying functions and pathways impacted by compound exposure through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)" [1]. This pathway-level concordance persists even when gene-level detection differs substantially.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and solutions for transcriptomic sample preparation

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Platform Application |

|---|---|---|

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | RNA stabilization during blood collection | Both platforms [32] |

| EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit | Automated RNA purification with DNase treatment | Both platforms [1] |

| GLOBINclear Kit | Globin mRNA depletion (blood samples) | Both platforms [32] |

| GeneChip 3' IVT Express Kit | cDNA synthesis, IVT, and biotin labeling | Microarray only [1] [32] |

| Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | RNA library preparation with poly(A) selection | RNA-seq only [1] |

| Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit | RNA quality assessment (RIN calculation) | Both platforms [1] |

| NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep | High-efficiency library construction | RNA-seq only [32] |

The choice between microarray and RNA-seq technologies for chemical perturbation profiling involves trade-offs between discovery power and practical considerations. While RNA-seq offers superior detection of novel transcripts, wider dynamic range, and higher sensitivity for low-abundance genes, microarrays provide a cost-effective alternative with established analytical frameworks that deliver equivalent performance for pathway identification and concentration-response modeling [1].

Researchers should select platforms based on their specific study objectives: RNA-seq is preferable for comprehensive transcriptome characterization and novel biomarker discovery, while microarrays remain viable for focused hypothesis testing in well-annotated genomes, particularly when processing large sample sets with limited budgets. For chemical perturbation studies specifically, both platforms generate comparable transcriptomic points of departure for risk assessment, suggesting that legacy microarray data remains relevant for toxicogenomic applications [1] [33].

Transcriptomic Benchmark Concentration (BMC) modeling represents a pivotal advancement in toxicogenomics, providing quantitative information that is increasingly used in regulatory risk assessment of data-poor chemicals [22]. This methodology enables researchers to derive transcriptomic points of departure (tPoDs) that can inform chemical safety decisions. The emergence of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) has accelerated the adoption of transcriptomic BMC modeling to address the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in toxicology testing while generating human-relevant data for risk assessment [22]. As the field progresses, a critical question has emerged: which transcriptomic platform—microarray or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)—offers superior performance for concentration-response studies? This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms within the context of chemical perturbation profiling, drawing upon recent experimental evidence to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Technological Platforms: Microarray vs. RNA-seq

Fundamental Principles and Evolution

Microarray technology, dominant for over a decade, employs a hybridization-based approach to profile transcriptome-wide gene expression by measuring fluorescence intensity of predefined transcripts [22]. This established platform offers relatively simple sample preparation, low per-sample cost, and well-established methodologies for data processing and analysis. However, microarrays suffer from limitations including restricted dynamic range, high background noise, and nonspecific binding [22].

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) emerged in the mid-2000s as a transformative alternative, based on counting reads that can be aligned to a reference sequence [22]. This next-generation sequencing approach theoretically offers unlimited dynamic range of signal detection and can identify transcripts not typically detectable by microarrays, including splice variants, microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and pseudogenes [22]. With advancing technology and reduced costs, RNA-seq has gradually become the mainstream platform for transcriptomic studies [22].

Key Technical Differences

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Microarray and RNA-seq Technologies

| Feature | Microarray | RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-based |

| Dynamic Range | Limited [22] | Wide (theoretically unlimited) [22] |

| Background Noise | High [22] | Lower |

| Transcript Discovery | Limited to predefined transcripts | Capable of detecting novel transcripts, splice variants, non-coding RNAs [22] |

| Sample Preparation | Relatively simple [22] | More complex |

| Cost per Sample | Low [22] | Higher |

| Data Analysis Resources | Well-established software and databases [22] | Rapidly evolving but require more sophisticated bioinformatics |

| A Priori Genome Knowledge | Required [5] | Not required [5] |

Experimental Comparison in Toxicogenomics

Case Studies with Cannabinoids

Recent research provides direct comparisons between microarray and RNA-seq platforms for concentration-response transcriptomic studies. A 2025 investigation examined two cannabinoids—cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN)—as case studies [22] [34]. The study utilized the same biological samples to generate both microarray and RNA-seq data, allowing for direct platform comparison without biological variability confounding the results.

The experimental protocol involved several key stages [22]:

- Cell Culture: Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) were cultured following manufacturer protocols and exposed to cannabinoids on day 6 of culture.

- Chemical Exposure: Cells were exposed to varying concentrations of CBC and CBN in triplicate, with DMSO vehicle controls (0.5% v/v), for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- RNA Extraction: Total RNA was purified using automated RNA purification instruments with DNase digestion, followed by quality assessment using NanoDrop and Bioanalyzer.

- Microarray Processing: Samples were processed using the GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit and hybridized to GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays, with scanning performed using the GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G.

- RNA-seq Library Preparation: Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation kit with polyA selection, followed by fragmentation and cDNA synthesis.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative transcriptomic studies

Performance Metrics and Benchmark Concentration Modeling

The critical assessment of both platforms focused on their performance in identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs), enriching biological pathways, and deriving transcriptomic points of departure (tPoDs) through BMC modeling [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Concentration-Response Transcriptomics

| Performance Metric | Microarray Results | RNA-seq Results |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Gene Expression Patterns | Similar patterns with regard to concentration for both CBC and CBN [22] | Similar patterns with regard to concentration for both CBC and CBN [22] |

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | Standard numbers identified | Larger numbers with wider dynamic ranges identified [22] |

| Non-coding RNA Detection | Limited | Many varieties detected [22] |

| Functional Pathway Identification (GSEA) | Equivalent performance [22] | Equivalent performance [22] |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) | Same level for both CBC and CBN [22] | Same level for both CBC and CBN [22] |

| BMC Modeling Performance | Equivalent | Equivalent |

Despite RNA-seq's technical advantages in detecting more DEGs with wider dynamic ranges and identifying non-coding RNAs, both platforms demonstrated equivalent performance in identifying functions and pathways impacted by compound exposure through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [22]. Most significantly, transcriptomic point of departure values derived through BMC modeling were at the same levels for both CBC and CBN across platforms [22].

These findings align with earlier comparative studies, such as research on aristolochic acid effects in rat kidneys, which found that while RNA-seq was more sensitive in detecting genes with low expression levels, the biological interpretation was largely consistent between platforms [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomic BMC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived Hepatocytes | Metabolically competent in vitro model for chemical exposure | iCell Hepatocytes 2.0 [22] |

| RNA Stabilization Buffer | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after cell lysis | RLT buffer (Qiagen) [22] |

| RNA Purification Kit | High-quality total RNA extraction with genomic DNA removal | EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit [22] |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Evaluates RNA integrity for downstream applications | Bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Nano Kit [22] |

| Microarray Platform | Whole transcriptome expression profiling | GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array [22] |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from total RNA | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation Kit [22] |

| BMC Modeling Software | Computational analysis of concentration-response data | BMD software [36] |

Experimental Design Considerations for BMC Studies

Concentration-Time Response Relationships

Recent research highlights the importance of considering both concentration and exposure time when designing transcriptomic studies for BMC derivation. A 2024 study demonstrated that BMC can vary with exposure time, and the degree of this variation is chemical-dependent [36]. For two of five chemicals tested, the point of departure varied by 0.5-1 log-order within a 48-hour timeframe [36].

The experimental approach utilized metabolically competent HepaRG cells exposed to five known toxicants over a range of concentrations and time points, followed by gene expression analysis using a targeted RNA expression assay (TempO-Seq) [36]. A non-parametric factor-modeling approach was employed to model the collective response of all significant genes, exploiting the interdependence of differentially expressed gene responses to determine an isobenchmark response (isoBMR) curve for each chemical [36].

Figure 2: Concentration-time modeling for BMC derivation

Platform Selection Decision Framework

Choosing between microarray and RNA-seq requires careful consideration of multiple factors:

Existing Expertise and Infrastructure: If a laboratory is already established for microarray analysis, transitioning to RNA-seq requires significant investment in expertise and computational resources [5].

Data Analysis Capabilities: Microarray data analysis benefits from decades of method development and user-friendly software, while RNA-seq analysis demands more sophisticated bioinformatics skills [5].

Genome Knowledge: For well-characterized organisms like humans or mice, both platforms are suitable. For non-model organisms, RNA-seq is necessary due to its independence from a priori genome knowledge [5].

Transcript Expression Levels: RNA-seq provides superior performance for detecting very low or high abundance transcripts due to its wider dynamic range [5].

Budget Constraints: Despite decreasing costs, RNA-seq remains more expensive than microarrays, particularly for large-scale studies involving hundreds of samples [5].

The comparative analysis between microarray and RNA-seq for transcriptomic BMC modeling reveals a nuanced landscape. While RNA-seq offers technical advantages including wider dynamic range, detection of novel transcripts, and superior sensitivity for low-abundance genes, these advantages do not necessarily translate to improved performance in deriving benchmark concentrations for chemical risk assessment [22]. Both platforms produce similar transcriptomic points of departure and biological interpretations through pathway analysis.

For traditional transcriptomic applications such as mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling, microarrays remain a viable and cost-effective choice, particularly considering their lower cost, smaller data size, and better availability of software and public databases for data analysis and interpretation [22]. However, for discovery-oriented research requiring detection of novel transcripts or comprehensive transcriptome characterization, RNA-seq provides distinct advantages. The decision between platforms should be guided by specific research goals, available resources, and the biological questions being addressed.