Next-Generation Sequencing in Chemogenomics: Basic Principles and Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in chemogenomics.

Next-Generation Sequencing in Chemogenomics: Basic Principles and Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and its transformative role in chemogenomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores how NGS technologies enable the high-throughput analysis of genetic material to unravel complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. The scope ranges from core sequencing methodologies and workflow to direct applications in target identification, mechanism of action studies, and personalized therapy. It further addresses critical challenges in data interpretation and platform selection, offering a practical guide for integrating NGS into efficient and targeted drug discovery pipelines.

Demystifying NGS: The Core Technologies Powering Modern Chemogenomics

The evolution from Sanger sequencing to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in genomics that has profoundly impacted chemogenomics research. This transition marks a move from low-throughput, targeted analysis to massively parallel, genome-wide approaches, enabling unprecedented scale and discovery power in genetic analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this technological revolution is crucial for leveraging genomic insights in target identification, mechanistic studies, and personalized medicine strategies. The core principle underlying this shift is massively parallel sequencing—where Sanger methods sequenced single DNA fragments individually, NGS technologies simultaneously sequence millions to billions of fragments, creating a high-throughput framework that has transformed genomic inquiry from a targeted endeavor to a comprehensive discovery platform [1] [2].

This revolution has been particularly transformative in chemogenomics, which explores the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. The ability to rapidly generate comprehensive genetic data has accelerated drug target validation, mechanism of action studies, and toxicity profiling. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, they are increasingly integrated with multiomic approaches and artificial intelligence, further enhancing their utility in pharmaceutical development and precision medicine initiatives [3]. This technical guide examines the principles, methods, and applications of this sequencing revolution within the context of modern chemogenomics research.

Historical Context: From Sanger to Massively Parallel Sequencing

The Sanger Sequencing Era

The Sanger method, developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977, established the foundational principles of DNA sequencing that would dominate for nearly three decades [2]. This first-generation technology employed dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) to terminate DNA synthesis at specific bases, creating fragments that could be separated by size through capillary electrophoresis [4] [5]. Automated Sanger sequencing instruments, commercialized by Applied Biosystems in the late 1980s, introduced fluorescence detection and capillary array electrophoresis, significantly improving throughput and reducing manual intervention [4] [6]. While this technology powered the landmark Human Genome Project, its limitations were substantial—the project required 13 years and approximately $3 billion to complete, highlighting the prohibitive cost and time constraints of first-generation methods [2].

Sanger sequencing faced fundamental scalability challenges for large-scale genomic applications. Each reaction could only sequence a single DNA fragment of ~400-1000 base pairs, making comprehensive genomic studies impractical [5] [2]. The technology's detection limit of approximately 15-20% for minor variants further restricted its utility for detecting low-frequency mutations in heterogeneous samples [1] [5]. These constraints created an urgent need for more scalable approaches as researchers sought to expand beyond single-gene investigations to genome-wide analyses in chemogenomics and other fields.

The Emergence of Next-Generation Sequencing

The year 2005 marked the beginning of the NGS revolution with the commercial introduction of the 454 Genome Sequencer by 454 Life Sciences [2]. This platform pioneered massively parallel sequencing using a novel approach based on pyrosequencing in microfabricated picoliter wells [4] [2]. The system utilized emulsion PCR to clonally amplify DNA fragments on beads, which were then deposited into wells and sequenced simultaneously through detection of light signals generated during nucleotide incorporation [2]. This approach enabled millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced in parallel—a dramatic departure from the one-fragment-at-a-time Sanger approach [2].

The period from 2005-2010 witnessed rapid innovation and platform diversification in the NGS landscape. In 2007, Illumina acquired Solexa and commercialized sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology using reversible dye terminators [2]. Applied Biosystems introduced SOLiD (Sequencing by Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection) around 2006, employing a unique ligation-based chemistry with two-base encoding [6] [2]. These competing technologies drove exponential increases in sequencing throughput while dramatically reducing costs. By 2008, resequencing of a human genome using Illumina's technology demonstrated that NGS could compete with Sanger for large genomic applications, validating its potential for comprehensive genetic studies [2].

Table 1: Key Milestones in Sequencing Technology Development

| Year | Technological Development | Impact on Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Sanger sequencing method developed | Enabled DNA sequencing with ~400-1000 bp read lengths [4] |

| 1987 | First commercial automated sequencer (ABI 370) | Introduced fluorescence detection and capillary electrophoresis [6] |

| 2005 | 454 Pyrosequencing (first commercial NGS) | First massively parallel sequencing platform [2] |

| 2006 | SOLiD sequencing platform introduced | Ligation-based sequencing with two-base encoding [2] |

| 2007 | Illumina acquires Solexa | Commercialized sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible terminators [2] |

| 2008 | First human genome resequenced with NGS | Validated NGS for whole-genome applications [2] |

| 2011 | PacBio SMRT sequencing launched | Introduced long-read, single-molecule sequencing [2] |

| 2014 | Oxford Nanopore MinION launch | Portable, real-time long-read sequencing [2] |

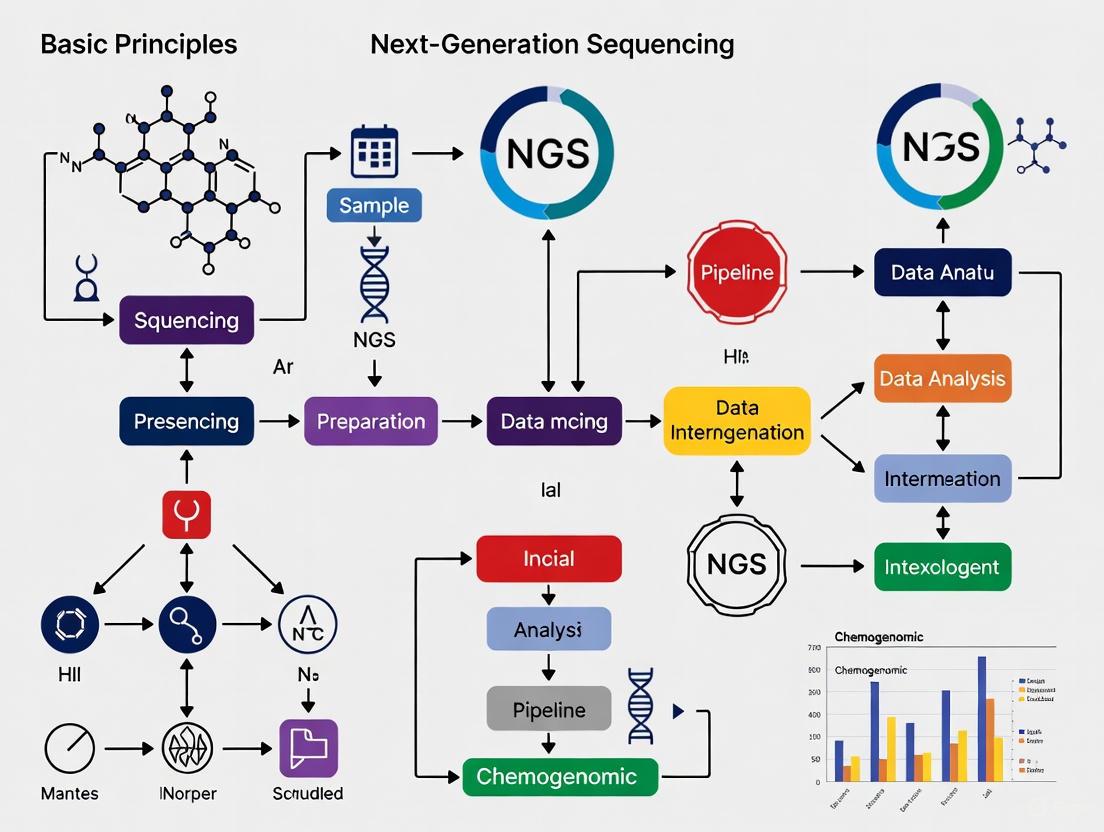

Figure 1: Evolution of DNA sequencing technologies from first-generation (Sanger) to second-generation (NGS) and third-generation platforms

Technical Foundations of NGS Platforms

Core NGS Methodologies

NGS technologies share a common principle of massively parallel sequencing but employ diverse biochemical approaches. The dominant Illumina platform utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye terminators [6]. In this method, DNA fragments amplified on a flow cell undergo cyclic nucleotide incorporation where fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are added and imaged before the termination reversible is removed for the next cycle [7] [6]. This approach generates read lengths typically ranging from 36-300 base pairs with high accuracy, making it suitable for a wide range of applications from targeted sequencing to whole genomes [6].

Other significant NGS technologies include pyrosequencing (employed by the now-discontinued 454 platform), which detected pyrophosphate release during nucleotide incorporation via light emission [4] [6]; ion semiconductor sequencing (Ion Torrent), which detects hydrogen ions released during DNA synthesis [6]; and sequencing by ligation (SOLiD), which utilized DNA ligase and fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides to determine sequences [6] [2]. Each technology presented distinct trade-offs in read length, error profiles, and cost structures, with Illumina ultimately emerging as the dominant platform due to its superior scalability and cost-effectiveness [6] [2].

Third-Generation Sequencing Technologies

A significant advancement in sequencing technology emerged with the development of third-generation platforms that address key limitations of second-generation NGS, particularly short read lengths. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) introduced Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, which utilizes zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) to observe individual DNA polymerase molecules incorporating fluorescent nucleotides in real time [6] [2]. This approach generates long reads averaging 10,000-25,000 base pairs, enabling resolution of complex genomic regions and detection of epigenetic modifications through kinetic analysis [6] [2].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies developed an alternative long-read approach based on nanopore sequencing, where DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane, causing characteristic changes in ionic current that identify individual nucleotides [6] [2]. This technology offers the unique advantages of extreme read lengths (potentially hundreds of kilobases), real-time data analysis, and portable form factors such as the MinION device [2]. Both third-generation platforms eliminate PCR amplification requirements, reducing associated biases and enabling direct detection of base modifications [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Sequencing Platforms and Technologies

| Platform/Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Chain termination with ddNTPs [5] | 400-1000 bp [4] | High accuracy, simple workflow [1] | Low throughput, high cost for many targets [1] |

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible terminators [6] | 36-300 bp [6] | High throughput, accuracy, and scalability [6] | Short reads, PCR amplification biases [6] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions [6] | 200-400 bp [6] | Rapid run times, lower instrument cost [6] | Homopolymer errors [6] |

| PacBio SMRT | Real-time single molecule sequencing [6] | 10,000-25,000 bp average [6] | Long reads, epigenetic modification detection [2] | Higher cost per sample, lower throughput [6] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore electrical signal detection [6] | 10,000-30,000 bp average [6] | Ultra-long reads, portability, real-time analysis [2] | Higher error rates (~15%) [6] |

Comparative Analysis: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS

Throughput and Sensitivity

The most fundamental distinction between Sanger sequencing and NGS lies in their throughput capacity. While Sanger sequencing processes a single DNA fragment per reaction, NGS platforms sequence millions to billions of fragments simultaneously in a massively parallel fashion [1]. This difference translates into extraordinary disparities in daily output—where a Sanger sequencer might generate thousands of base pairs per day, modern NGS instruments can produce terabases of sequence data in the same timeframe [1] [2]. This massive throughput enables applications that are simply impractical with Sanger methods, including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and large-scale population studies [1].

NGS also provides significantly enhanced sensitivity for variant detection, particularly for low-frequency mutations. While Sanger sequencing has a detection limit of approximately 15-20% for minor variants, targeted NGS with deep sequencing can reliably detect variants present at frequencies as low as 1% [1] [5]. This increased sensitivity is critical for applications such as cancer genomics, where tumor heterogeneity produces subclonal populations, and for infectious disease monitoring, where pathogen variants may be rare within a complex background [1]. The combination of high throughput and superior sensitivity has established NGS as the preferred technology for comprehensive genomic characterization.

Applications and Cost Considerations

The choice between Sanger sequencing and NGS is primarily determined by the scope of the research question and economic considerations. Sanger sequencing remains a cost-effective and reliable choice for targeted interrogation of small genomic regions (typically ≤20 targets) or when verifying specific variants identified through NGS [1] [5]. Its straightforward workflow, minimal bioinformatics requirements, and rapid turnaround for small projects make it well-suited for diagnostic applications focused on established variants and for laboratories with limited bioinformatics infrastructure [5].

In contrast, NGS provides superior economic value for larger-scale projects, despite requiring more complex library preparation and data analysis pipelines [1]. The ability to multiplex hundreds of samples in a single run dramatically reduces per-sample costs for comprehensive genomic analyses [1] [5]. Furthermore, NGS offers unparalleled discovery power for identifying novel variants across targeted regions, entire exomes, or whole genomes—applications that would be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming with Sanger methods [1] [5]. For chemogenomics research, which often requires comprehensive genomic profiling to understand compound mechanisms and variability in response, NGS has become an indispensable tool.

Table 3: Decision Framework for Selecting Sequencing Methodology

| Consideration | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Use Cases | Single-gene studies, variant confirmation, small target numbers (≤20) [1] | Large gene panels, whole exome/genome sequencing, novel variant discovery [1] |

| Throughput | Low: sequences one fragment at a time [1] | High: massively parallel sequencing of millions of fragments [1] |

| Sensitivity | 15-20% limit of detection [1] [5] | Can detect variants at 1% frequency or lower with deep sequencing [1] |

| Cost Efficiency | Cost-effective for small numbers of targets [1] | More economical for larger numbers of targets/samples [1] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited or none | High: can barcode hundreds of samples per run [1] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Minimal | Complex, requires bioinformatics expertise [8] |

NGS Workflows and Data Analysis

Laboratory Workflow

The standard NGS workflow comprises four fundamental steps: nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [7]. Library preparation is a critical stage where extracted DNA or RNA is fragmented, and specialized adapters are ligated to fragment ends [7]. These adapters serve multiple functions—they facilitate binding to the sequencing platform surface, enable PCR amplification if required, and contain sequencing primer binding sites [7]. For Illumina platforms, library fragments are amplified on a flow cell through bridge amplification, creating clonal clusters that each originate from a single molecule [4]. Library preparation methods vary significantly depending on the application, with specialized approaches available for whole-genome sequencing, targeted sequencing, RNA sequencing, and epigenetic analyses.

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) have become an important enhancement to NGS library preparation, particularly for applications requiring accurate quantification or detection of low-frequency variants [8]. UMIs are short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before amplification, serving as molecular barcodes that distinguish original molecules from PCR duplicates [8]. This approach improves quantification accuracy in RNA-seq and enables more sensitive variant detection in applications such as liquid biopsy by correcting for amplification and sequencing errors [8].

Data Analysis Framework

NGS data analysis represents a significant computational challenge due to the massive volume of data generated, typically requiring sophisticated bioinformatics infrastructure and expertise [8]. The analysis workflow is generally conceptualized in three stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary analysis [8]. Primary analysis involves base calling and quality assessment, converting raw signal data (e.g., .bcl files in Illumina platforms) into FASTQ files containing sequence reads and quality scores [8]. Key quality metrics assessed at this stage include Phred quality scores (Q30 indicating 99.9% base call accuracy), cluster density, and percentage of reads passing filters [8].

Secondary analysis encompasses read alignment and variant calling, transforming FASTQ files into biologically meaningful data [8]. During this stage, sequence reads are aligned to a reference genome using tools such as BWA or Bowtie 2, producing BAM files that document alignment positions [8]. Variant calling identifies differences between the sequenced sample and reference genome, with results typically stored in VCF format [8]. For RNA sequencing, this stage includes gene expression quantification, while for other applications it may involve detecting epigenetic modifications or structural variants.

Tertiary analysis represents the interpretation phase, where biological meaning is extracted from variant calls and expression data [8]. This may include annotating variants with functional predictions, identifying enriched pathways, correlating genetic findings with clinical outcomes, or integrating multiomic datasets [8]. Tertiary analysis is increasingly leveraging machine learning approaches to identify complex patterns in high-dimensional genomic data, particularly in chemogenomics applications where compound responses are correlated with genomic features [3].

Figure 2: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflow encompassing both wet laboratory procedures and bioinformatics analysis stages

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of NGS in chemogenomics research requires careful selection of reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines key components of the NGS ecosystem:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS workflows

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in NGS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, NEBNext Ultra II | Fragment DNA/RNA, add platform-specific adapters, optional amplification [7] |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina Nextera Flex, Twist Target Enrichment | Enrich specific genomic regions of interest using hybrid capture or amplicon approaches |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | IDT UMI Adaptors, Swift UMI kits | Molecular barcoding to distinguish PCR duplicates from original molecules [8] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore | Generate sequence data from prepared libraries [6] [9] |

| Alignment Tools | BWA, Bowtie 2, STAR | Map sequence reads to reference genome [8] |

| Variant Callers | GATK, FreeBayes, DeepVariant | Identify genetic variants from aligned reads [8] |

| Genome Browsers | IGV, UCSC Genome Browser | Visualize aligned sequencing data and variants [8] |

| Bioinformatics Languages | Python, R, Perl, Bash | Script custom analysis pipelines and statistical analyses [8] |

Current Trends and Future Directions

Multiomics and AI Integration

The NGS field is increasingly moving toward integrated multiomic approaches that combine genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from the same samples [3]. This trend is particularly relevant for chemogenomics research, where understanding the comprehensive biological effects of chemical compounds requires insights across multiple molecular layers. In 2025, population-scale genome studies are expanding to incorporate direct interrogation of native RNA and epigenomic markers rather than relying on proxy measurements, enabling more sophisticated understanding of biological mechanisms [3]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with these multiomic datasets is creating new opportunities for biomarker discovery, drug target identification, and predictive modeling of compound efficacy and toxicity [3].

Spatial genomics represents another frontier in NGS technology, enabling direct sequencing of cells within their native tissue context [3]. This approach preserves critical spatial information about cellular organization and microenvironment interactions that is lost in bulk sequencing methods. By 2025, spatial biology is poised for breakthroughs with new high-throughput sequencing-based technologies that enable large-scale, cost-effective studies, including 3D spatial analyses of tissue microenvironments [3]. For chemogenomics, spatial transcriptomics and genomics offer unprecedented insights into compound effects on tissue organization and cellular communities.

Market Growth and Clinical Adoption

The United States NGS market is projected to grow from $3.88 billion in 2024 to $16.57 billion by 2033, representing a compound annual growth rate of 17.5% [9]. This growth is driven by advancing sequencing technologies, expanding clinical applications, and increasing adoption in agricultural and environmental research [9]. Key factors propelling market expansion include the growing demand for personalized medicine, government funding initiatives such as the NIH's All of Us Research Program, and increased adoption in clinical diagnostics for cancer, genetic diseases, and infectious agents [9].

Clinical adoption of NGS continues to accelerate as costs decline and analytical validation improves. The emergence of benchtop sequencers and more automated workflows is decentralizing NGS applications, moving testing closer to point-of-care settings [3]. Liquid biopsy applications for cancer detection and monitoring are particularly promising, requiring technologies that provide extremely low limits of detection (part-per-million level) to identify rare circulating tumor DNA fragments without prohibitive costs [3]. As sequencing costs approach and fall below the $100 genome milestone, NGS is increasingly positioned to become standard of care across the patient continuum [3].

The revolution from Sanger sequencing to NGS has fundamentally transformed genomics and its applications in chemogenomics research. This paradigm shift from single-gene analysis to massively parallel, genome-wide interrogation has expanded the scale and scope of scientific inquiry, enabling researchers to address biological questions that were previously intractable. The continuing evolution of NGS technologies—including third-generation long-read sequencing, spatial genomics, and integrated multiomic approaches—promises to further enhance our understanding of biological systems and accelerate drug discovery and development. For research scientists and drug development professionals, staying abreast of these technological advancements is essential for leveraging the full potential of genomic information in chemogenomics applications. As NGS continues to become more accessible, cost-effective, and integrated with artificial intelligence, its role in personalized medicine and targeted therapeutic development will only expand, solidifying its position as a cornerstone technology in 21st-century biomedical research.

Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS), commonly termed next-generation sequencing (NGS), represents a fundamental paradigm shift in genomic analysis that has revolutionized chemogenomics research and drug development. This technology enables the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments through spatially separated, parallelized processing platforms, dramatically reducing the cost and time required for comprehensive genetic analysis. The core principle hinges on the miniaturization and parallelization of sequencing reactions, allowing researchers to obtain unprecedented volumes of genetic data in a single instrument run. This technical guide examines the underlying mechanisms, platform technologies, and analytical frameworks of MPS, with specific emphasis on their applications in chemogenomics research for identifying novel drug targets, understanding compound mechanisms of action, and advancing personalized therapeutic strategies.

Massively Parallel Sequencing encompasses several high-throughput approaches to DNA sequencing that utilize the concept of massively parallel processing, a radical departure from first-generation Sanger sequencing methods [10]. These technologies emerged commercially in the mid-2000s and have since become indispensable tools in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. MPS platforms can sequence between 1 million and 43 billion short reads (typically 50-400 bases each) per instrument run, generating gigabytes to terabytes of genetic information in a single experiment [10]. This exponential increase in data output has facilitated large-scale genomic studies that were previously impractical due to technological and economic constraints.

In chemogenomics research, which focuses on the systematic identification of all possible pharmacological interactions between chemical compounds and their biological targets, MPS provides unprecedented capabilities for understanding drug-gene relationships at genome-wide scale. The technology enables researchers to simultaneously assess genetic variations, gene expression patterns, epigenetic modifications, and compound-induced genomic changes across entire biological systems. This comprehensive profiling is essential for identifying novel drug targets, understanding mechanisms of drug resistance, and developing personalized treatment strategies based on individual genetic profiles.

Historical Development and Technological Evolution

The development of MPS technologies was largely driven by initiatives following the Human Genome Project, particularly the NIH's 'Technology Development for the $1,000 Genome' program launched during Francis Collins' tenure as director of the National Human Genome Research Institute [10]. The first next-generation sequencers were based on pyrosequencing, originally developed by Pyrosequencing AB and commercialized by 454 Life Sciences, which launched the GS20 system in 2003 [10]. This platform provided reads approximately 400-500 bp long with 99% accuracy, enabling sequencing of about 25 million bases in a four-hour run at significantly lower costs compared to Sanger sequencing.

In 2004, Soleqa began developing Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) technology, later acquiring colony sequencing (bridge amplification) technology from Manteia [10]. This approach produced densely clustered DNA fragments ("polonies") immobilized on flow cells, with stronger fluorescent signals that improved accuracy and reduced optical costs. The first commercial sequencer based on this technology, the Genome Analyzer, was launched in 2006, providing shorter reads (about 35 bp) but higher throughput (up to 1 Gbp per run) and paired-end sequencing capability [10].

The sequencing technology landscape has evolved significantly through corporate acquisitions and technological innovations. In 2007, 454 Life Sciences was acquired by Roche and Solexa by Illumina, the same year Applied Biosystems introduced SOLiD, a ligation-based sequencing platform [10]. Illumina's SBS technology eventually dominated the sequencing market, and by 2014, Illumina controlled approximately 70% of DNA sequencer sales and generated over 90% of sequencing data [10]. Continuing innovation has led to the development of third-generation sequencing technologies, such as PacBio and Oxford Nanopore, which enable direct sequencing of single DNA molecules without amplification, providing longer read lengths and real-time sequencing capabilities [11].

Core Principles of Massively Parallel Sequencing

The fundamental principle of MPS involves sequencing millions of short DNA or RNA fragments simultaneously, generating high-throughput data in a single run [11]. This represents a radical departure from traditional Sanger sequencing, which processes individual DNA fragments sequentially through capillary electrophoresis. The massively parallel approach enables unprecedented scaling of sequencing output while dramatically reducing per-base costs.

The core principle can be deconstructed into three essential components: template preparation through fragmentation and amplification, parallelized sequencing through cyclic interrogation, and detection of incorporated nucleotides through various signaling mechanisms. Unlike Sanger sequencing, which is based on electrophoretic separation of chain-termination products produced in individual sequencing reactions, MPS employs spatially separated, clonally amplified DNA templates or single DNA molecules in a flow cell [10]. This design allows sequencing to be completed on a much larger scale without physical separation of reaction products.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technology Generations

| Generation | Technology Examples | Key Characteristics | Read Length | Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Sanger Sequencing | Single fragment sequencing, high accuracy | 600-1000 bp | Validation of genetic variants, targeted analysis |

| Second Generation | Illumina, Ion Torrent | Clonal amplification, short reads, high throughput | 50-400 bp | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, variant discovery |

| Third Generation | PacBio, Oxford Nanopore | Single molecule sequencing, long reads, real-time | 10,000+ bp | Structural variant detection, haplotype phasing, epigenetic modification |

In chemogenomics research, understanding these core principles is essential for selecting appropriate sequencing strategies for specific applications. The choice between different MPS platforms involves trade-offs between read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost, each factor influencing the experimental design for drug target identification and validation.

MPS Platform Technologies and Methodologies

Template Preparation Methods

MPS requires specialized template preparation to enable parallel sequencing. Two primary methods are employed: amplified templates originating from single DNA molecules, and single DNA molecule templates [10]. For imaging systems that cannot detect single fluorescence events, amplification of DNA templates is required. The three most common amplification methods are:

Emulsion PCR (emPCR) involves attaching single-stranded DNA fragments to beads with complementary adaptors, then compartmentalizing them into water-oil emulsion droplets. Each droplet serves as a PCR microreactor producing amplified copies of the single DNA template [10]. This method is utilized by platforms such as Roche/454 and Ion Torrent.

Bridge Amplification, used in Illumina platforms, involves covalently attaching forward and reverse primers at high density to a slide in a flow cell. The free end of a ligated fragment "bridges" to a complementary oligo on the surface, and repeated denaturation and extension results in localized amplification of DNA fragments in millions of separate locations across the flow cell surface [10]. This produces 100-200 million spatially separated template clusters.

Rolling Circle Amplification generates DNA nanoballs through circularization of DNA fragments followed by isothermal amplification. These nanoballs are then deposited on patterned flow cells at high density for sequencing. This approach is used in BGI's DNBSEQ platforms and offers advantages in reducing amplification biases and improving data quality [10].

For single-molecule templates, protocols eliminate PCR amplification steps, thereby avoiding associated biases and errors. Single DNA molecules are immobilized on solid supports through various approaches, including attachment to primed surfaces or passage through biological nanopores [10]. These methods are particularly advantageous for AT-rich and GC-rich regions that often show amplification bias.

Sequencing Chemistry and Detection Methods

Different MPS platforms employ distinct sequencing chemistries and detection mechanisms, each with unique advantages and limitations for specific research applications:

Sequencing by Synthesis with Reversible Terminators (Illumina) utilizes fluorescently labeled nucleotides that incorporate into growing DNA strands but temporarily terminate polymerization. After imaging to identify the incorporated base, the terminator is chemically cleaved to allow incorporation of the next nucleotide [12]. This cyclic process enables base-by-base sequencing with high accuracy, though read lengths are typically shorter than other methods.

Pyrosequencing (Roche/454) detects nucleotide incorporation indirectly through light emission. When a nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, an inorganic phosphate ion is released, initiating an enzyme cascade that produces light. The intensity of light correlates with the number of incorporated nucleotides, allowing detection of homopolymer regions, though accuracy in these regions can be challenging [12].

Semiconductor Sequencing (Ion Torrent) measures pH changes resulting from hydrogen ion release during nucleotide incorporation. This approach uses standard nucleotides without optical detection, making the technology simpler and less expensive. However, it similarly struggles with accurate sequencing of homopolymer regions [11].

Sequencing by Ligation (SOLiD) utilizes DNA ligase rather than polymerase to determine sequence information. Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes hybridize to the template and are ligated, with the fluorescence identity determining the sequence. Each base is interrogated twice in this system, providing inherent error correction capabilities [12].

Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing (Pacific Biosciences) monitors nucleotide incorporation in real time using zero-mode waveguides. As fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated by a polymerase, their emission is detected without pausing the synthesis reaction. This enables very long read lengths but with higher error rates compared to other technologies [11].

Nanopore Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore) measures changes in ionic current as DNA strands pass through biological nanopores. Each nucleotide disrupts the current in characteristic ways, allowing direct electronic sequencing of DNA or RNA molecules. This technology offers extremely long reads and real-time analysis capabilities [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Major MPS Platforms and Their Characteristics

| Platform | Template Preparation | Chemistry | Max Read Length | Run Time | Throughput per Run | Key Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq | Bridge Amplification | Reversible Terminator | 2×150 bp | 1-3 days | 3000 Gb | Large-scale whole genome sequencing, population studies |

| Ion Torrent | emPCR | Semiconductor (pH detection) | 200-400 bp | 2-4 hours | 10-100 Gb | Targeted sequencing, rapid screening |

| PacBio Revio | Single Molecule | SMRT Sequencing | 10,000-30,000 bp | 0.5-4 hours | 360 Gb | Structural variants, haplotype phasing |

| Oxford Nanopore | Single Molecule | Nanopore | 10,000+ bp | Real-time | 10-100 Gb | Metagenomics, direct RNA sequencing |

| BGI DNBSEQ | DNA Nanoballs | Recombinase Polymerase Amplification | 2×150 bp | 1-3 days | 600-1800 Gb | Large-scale genomic projects |

Diagram 1: MPS Workflow and Technology Options - This diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for massively parallel sequencing, from sample preparation through data interpretation, highlighting the different technology options at each stage.

MPS Data Analysis Framework

The analysis of MPS-generated data involves multiple computational stages to transform raw sequencing signals into biologically meaningful information. The NGS data analysis process includes three main steps: primary, secondary, and tertiary data analysis [13].

Primary Data Analysis

Primary analysis begins during the sequencing run itself, with real-time processing of raw signals into base calls. For example, Illumina's Real-Time Analysis (RTA) software operates during cycles of sequencing chemistry and imaging, providing base calls and associated quality scores representing the primary structure of DNA or RNA strands [13]. This built-in software performs primary data analysis automatically on the sequencing instrument, generating FASTQ or similar format files containing sequence reads and their quality metrics.

Secondary Data Analysis

Secondary analysis involves alignment of sequence reads to a reference genome and identification of genetic variants. This stage includes several critical processes:

Sequence Alignment/Mapping involves determining the genomic origin of each sequence read by aligning it to a reference genome. This is computationally intensive due to the massive volume of short reads generated by MPS platforms. Common alignment tools include BWA, Bowtie, and NovoAlign, each employing different algorithms to optimize speed and accuracy.

Variant Calling identifies differences between the sequenced sample and the reference genome. This includes single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants. Variant callers such as GATK, FreeBayes, and SAMtools employ statistical models to distinguish true genetic variants from sequencing errors.

Variant Filtering and Annotation removes low-quality calls and adds biological context to identified variants. This includes predicting functional consequences on genes, assessing population frequency in databases like gnomAD, and evaluating potential pathogenicity using tools such as ANNOVAR, SnpEff, or VEP.

Tertiary Analysis

Tertiary analysis focuses on biological interpretation of the identified variants in the context of the research question or clinical application. In chemogenomics, this may include:

Pathway Analysis to identify biological pathways enriched with genetic variants, helping to contextualize findings within known drug response mechanisms or disease pathways. Tools such as Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and GSEA are commonly used.

Variant Prioritization to identify the most likely causal variants for further functional validation. This often involves integrating multiple lines of evidence, including functional predictions, conservation scores, and regulatory element annotations.

Data Visualization using tools such as the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), which enables interactive exploration of large, integrated genomic datasets, including aligned reads, genetic variants, and gene annotations [14]. IGV supports a wide variety of data types and allows researchers to visualize sequence data in the context of genomic features.

Diagram 2: MPS Data Analysis Framework - This diagram illustrates the three-stage process of MPS data analysis, from raw data processing to biological interpretation, highlighting key computational steps at each stage.

Applications in Chemogenomics Research

MPS technologies have become fundamental tools in chemogenomics research, enabling comprehensive analysis of compound-genome interactions at unprecedented scale and resolution. Key applications include:

Pharmacogenomics and Drug Response Profiling

MPS enables comprehensive characterization of genetic variants influencing drug metabolism, efficacy, and adverse reactions. By sequencing genes involved in drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics across diverse populations, researchers can identify genetic markers predictive of treatment outcomes [15]. Whole genome sequencing approaches allow identification of both common and rare variants contributing to interindividual variability in drug response, facilitating development of personalized treatment strategies.

Target Identification and Validation

MPS facilitates systematic identification of novel drug targets through analysis of genetic variations associated with disease susceptibility and progression. Large-scale sequencing studies can identify genes with loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations in patient populations, highlighting potential therapeutic targets [16]. For example, trio sequencing studies (sequencing of both parents and affected offspring) have identified de novo mutations contributing to severe disorders, revealing novel pathogenic mechanisms and potential intervention points [16].

Functional Genomics and CRISPR Screening

The integration of MPS with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized functional genomics in chemogenomics research. Technologies such as CRISPEY enable highly efficient, parallel precise genome editing to measure fitness effects of thousands of natural genetic variants [17]. In one application, researchers studied the fitness consequences of 16,006 natural genetic variants in yeast, identifying 572 variants with significant fitness differences in glucose media; these were highly enriched in promoters and transcription factor binding sites, providing insights into regulatory mechanisms of gene expression [17].

Cancer Genomics and Precision Oncology

MPS has transformed cancer drug development by enabling comprehensive characterization of somatic mutations, gene expression changes, and epigenetic alterations in tumors. Panel sequencing targeting cancer-associated genes allows identification of actionable mutations guiding targeted therapy selection [11]. Whole exome and whole genome sequencing of tumor-normal pairs facilitates discovery of novel cancer genes and mutational signatures, informing both target discovery and patient stratification strategies.

Microbiome and Metagenomic Analysis

MPS enables characterization of complex microbial communities and their interactions with pharmaceutical compounds. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing provides insights into how gut microbiota influence drug metabolism and efficacy, potentially explaining variability in treatment response [11]. This application is particularly relevant for understanding drug-microbiome interactions and developing strategies to modulate microbial communities for therapeutic benefit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MPS Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in MPS Workflow | Considerations for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Fragmentation enzymes, adapters, ligases | Fragment DNA and add platform-specific sequences | Insert size affects coverage uniformity; adapter design impacts multiplexing |

| Target Enrichment | Hybridization probes, PCR primers | Selective amplification of genomic regions of interest | Probe design must avoid SNP sites; coverage gaps may require Sanger filling |

| Sequencing | Flow cells, sequencing primers, polymerases | Template immobilization and sequence determination | Platform-specific requirements; read length determined by chemistry cycles |

| Indexing/Barcoding | Dual index primers, unique molecular identifiers | Sample multiplexing and PCR duplicate removal | Enough unique barcodes for sample multiplexing plan |

| Quality Control | AMPure XP beads, Bioanalyzer chips, qPCR kits | Library quantification and size selection | Accurate quantification critical for cluster density optimization |

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Library Preparation Protocols

Effective MPS experiments require optimized library preparation protocols tailored to specific research questions. A standard protocol for Illumina platforms includes:

DNA Fragmentation through mechanical shearing (acoustic focusing) or enzymatic digestion (transposase-based tagmentation) to generate fragments of appropriate size (typically 200-500 bp for whole genome sequencing).

End Repair and A-tailing to create blunt-ended fragments with 5'-phosphates and 3'-A-overhangs, facilitating adapter ligation.

Adapter Ligation using T4 DNA ligase to attach platform-specific adapter sequences containing priming sites for amplification and sequencing, as well as sample-specific barcode sequences for multiplexing.

Size Selection using SPRI beads (e.g., AMPure XP) to remove adapter dimers and select fragments of the desired size distribution, improving library uniformity.

Library Amplification using limited-cycle PCR to enrich for properly ligated fragments and incorporate complete adapter sequences. The number of amplification cycles should be minimized to reduce duplicates and amplification biases.

For targeted sequencing approaches, additional enrichment steps are required, typically using either hybrid capture with biotinylated probes or amplicon-based approaches using target-specific primers. Each method offers different advantages: hybrid capture provides more uniform coverage and flexibility in target design, while amplicon approaches require less input DNA and have simpler workflows.

Quality Control Metrics

Rigorous quality control is essential throughout the MPS workflow to ensure data quality and interpretability. Key metrics include:

DNA Quality assessed by fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) and fragment size analysis (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation). High-molecular-weight DNA is preferred for most applications, though specialized protocols exist for degraded samples.

Library Concentration measured by qPCR-based methods (e.g., KAPA Library Quantification) that detect amplifiable molecules, providing more accurate quantification than fluorometry alone.

Sequencing Quality monitored through metrics such as Q-scores (probability of incorrect base call), cluster density, and phasing/prephasing rates. Most platforms provide real-time quality metrics during the sequencing run.

Coverage Metrics including mean coverage depth, coverage uniformity, and percentage of target bases covered at minimum depth (typically 10-20x for variant calling). These metrics determine variant detection sensitivity and specificity.

Experimental Design for Chemogenomics Studies

Effective experimental design is critical for generating meaningful results in chemogenomics applications:

Sample Size Considerations must balance statistical power with practical constraints. For variant discovery, larger sample sizes increase power to detect rare variants, while for differential expression, appropriate replication is essential for reliable statistical testing.

Controls including positive controls (samples with known variants), negative controls (samples without expected variants), and technical replicates are essential for assessing technical performance and distinguishing biological signals from artifacts.

Multiplexing Strategies should incorporate sufficient barcode diversity to prevent index hopping and cross-contamination between samples. The level of multiplexing affects sequencing depth per sample and should be optimized based on the specific application requirements.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The continued evolution of MPS technologies promises to further transform chemogenomics research and drug development. Emerging trends include:

Single-Cell Sequencing technologies enable analysis of genetic heterogeneity within tissues and cell populations, providing insights into cell-type-specific responses to chemical compounds and mechanisms of drug resistance. Applications in oncology, immunology, and neuroscience are particularly promising for understanding complex biological systems and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Long-Read Sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are overcoming traditional limitations in resolving complex genomic regions, structural variations, and epigenetic modifications. These platforms enable more comprehensive characterization of genomic architecture and haplotype phasing, improving our understanding of how genetic variations influence drug response.

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data from the same samples provide systems-level insights into drug mechanisms and biological pathways. MPS serves as the foundational technology enabling these comprehensive analyses, with computational methods advancing to integrate diverse data types.

Direct RNA Sequencing without reverse transcription preserves natural base modifications and eliminates amplification biases, providing more accurate quantification of gene expression and enabling detection of RNA modifications that may influence compound activity.

Portable Sequencing devices are making genomic analysis more accessible and enabling point-of-care applications. The MiniON from Oxford Nanopore exemplifies this trend, with potential applications in rapid pathogen identification, environmental monitoring, and field research.

As MPS technologies continue to evolve, they will further integrate into the drug discovery and development pipeline, from target identification through clinical trials and post-market surveillance. The increasing scale and decreasing cost of genomic analysis will enable more comprehensive characterization of compound-genome interactions, accelerating the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

Massively Parallel Sequencing has fundamentally transformed the landscape of genomic analysis and chemogenomics research. By enabling the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments, MPS provides unprecedented scale and efficiency in genetic characterization. The core principle of parallelization through spatially separated sequencing templates, combined with diverse biochemical approaches for template preparation and nucleotide detection, has created a versatile technological platform with applications across all areas of biomedical research.

In chemogenomics, MPS facilitates comprehensive analysis of genetic variations influencing drug response, systematic identification of novel therapeutic targets, and functional characterization of biological pathways. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, with improvements in read length, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness, their impact on drug discovery and development will continue to grow. The integration of MPS with other emerging technologies, including CRISPR-based genome editing and single-cell analysis, promises to further accelerate the pace of discovery in chemical biology and therapeutic development.

Researchers and drug development professionals must maintain awareness of both the capabilities and limitations of different MPS platforms and methodologies to effectively leverage these powerful tools. Appropriate experimental design, rigorous quality control, and sophisticated computational analysis are all essential components of successful MPS-based research programs. As the field continues to evolve, MPS will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technology for advancing our understanding of genome-compound interactions and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics research by providing powerful tools to understand complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. As a cornerstone of modern genomic analysis, NGS technologies enable researchers to decipher genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications with unprecedented resolution [6]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of chemogenomics, facilitating studies on drug-target interactions, mechanism of action analysis, resistance mechanisms, and toxicogenomics. In chemogenomics, where understanding the genetic basis of drug response is paramount, the choice of sequencing platform directly impacts the depth and quality of insights that can be generated. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three major NGS platforms—Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)—focusing on their working principles, performance characteristics, and applications in chemogenomics research.

Core Sequencing Technologies: Principles and Methodologies

Illumina: Sequencing by Synthesis

Illumina platforms utilize sequencing by synthesis (SBS) with reversible dye-terminators. This technology relies on solid-phase sequencing on an immobilized surface leveraging clonal array formation using proprietary reversible terminator technology. During sequencing, single labeled dNTPs are added to the nucleic acid chain, with fluorescence detection occurring after each incorporation cycle [6]. The process involves bridge amplification on flow cells containing patterned nanowells at fixed locations, which provides even spacing of sequencing clusters and enables massive parallelization [18]. Illumina's latest XLEAP-SBS chemistry delivers improved reagent stability with two-fold faster incorporation times compared to previous versions, representing a significant advancement in both speed and quality [18].

Pacific Biosciences: Single Molecule Real-Time Sequencing

PacBio employs Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, which utilizes a structure called a zero-mode waveguide (ZMW). Individual DNA molecules are immobilized within these small wells, and as polymerase incorporates each nucleotide, the emitted light is detected in real-time [6]. This approach allows the platform to generate long reads with average lengths between 10,000-25,000 bases. A key innovation is the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) protocol, which generates HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads by making multiple passes of the same DNA molecule, achieving accuracy exceeding 99.9% [19] [20]. The technology sequences native DNA, preserving base modification information that is crucial for epigenomics studies in chemogenomics.

Oxford Nanopore: Electronic Molecular Sensing

Oxford Nanopore technology is based on the measurement of electrical current disruptions as DNA or RNA molecules pass through protein nanopores. The technology utilizes a flow cell containing an electrically resistant membrane with nanopores of eight nanometers in width. Electrophoretic mobility drives the linear nucleic acid strands through these pores, generating characteristic current signals for each nucleotide that enable base identification [6] [21]. This unique approach allows for real-time sequencing and direct detection of base modifications without additional experiments or preparation. Recent advancements in chemistry (R10.4.1 flow cells) and basecalling algorithms have significantly improved raw read accuracy to over 99% [21] [22].

Technical Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the key technical specifications and performance metrics of the three major NGS platforms, highlighting their distinct characteristics and capabilities relevant to chemogenomics research.

Table 1: Platform Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | Illumina | PacBio | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) | Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | Nanopore Electrical Sensing |

| Read Length | 36-300 bp (short-read) [6] | Average 10,000-25,000 bp (long-read) [6] | Average 10,000-30,000 bp (long-read) [6] |

| Maximum Output | NovaSeq X Plus: 8 Tb (dual flow cell) [18] | Revio: 120 Gb per SMRT Cell [23] | Platform-dependent (MinION/PromethION) |

| Typical Accuracy | >85% bases >Q30 [18] | ~99.9% (HiFi reads) [20] | >99% raw read accuracy (Q20+) [21] |

| Error Profile | Substitution errors [24] | Random errors | Mainly indel errors [24] |

| Run Time | ~17-48 hours (NovaSeq X) [18] | Varies by system | Real-time data streaming |

| Epigenetic Detection | Requires bisulfite conversion | Direct detection of base modifications [20] | Direct detection of DNA/RNA modifications [21] |

Table 2: Platform Applications in Chemogenomics Research

| Application | Illumina | PacBio | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Excellent for small genomes, exomes, panels [25] | Ideal for complex regions, structural variants [23] | Comprehensive genome coverage, T2T assembly [21] |

| Transcriptomics | mRNA-Seq, gene expression profiling [25] | Full-length isoform sequencing [20] | Direct RNA sequencing, isoform detection |

| Metagenomics | 16S sequencing, shotgun metagenomics [25] | Full-length 16S for species-level resolution [19] | Real-time adaptive sampling for enrichment |

| Variant Detection | SNVs, indels (short-range) | Comprehensive variant calling (SNVs, indels, SVs) [23] | Structural variant detection, phasing |

| Epigenomics | Methylation sequencing with special prep [25] | Built-in methylation calling (5mC, 6mA) [20] | Direct detection of multiple modifications [21] |

Experimental Comparisons and Benchmarking Studies

16S rRNA Sequencing for Microbiome Analysis

Microbiome studies are particularly relevant in chemogenomics for understanding drug-microbiome interactions. A 2025 comparative study evaluated Illumina (V3-V4 regions), PacBio (full-length), and ONT (full-length) for 16S rRNA sequencing of rabbit gut microbiota. The results demonstrated significant differences in species-level resolution, with ONT classifying 76% of sequences to species level, PacBio 63%, and Illumina 48% [19]. However, most species-level classifications were labeled as "uncultured bacterium," highlighting database limitations rather than technological constraints. The study also found that while high correlations between relative abundances of taxa were observed, diversity analysis showed significant differences between the taxonomic compositions derived from the three platforms [19].

A similar 2025 study on soil microbiomes compared these platforms and found that ONT and PacBio provided comparable bacterial diversity assessments when sequencing depth was normalized. PacBio showed slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa, but ONT results closely matched PacBio despite differences in inherent sequencing accuracy. Importantly, all platforms enabled clear clustering of samples based on soil type, except for the V4 region alone where no soil-type clustering was observed (p = 0.79) [22].

Whole Genome Assembly Performance

A 2023 practical comparison of NGS platforms and assemblers using the yeast genome provides valuable insights for chemogenomics researchers working with model organisms. The study found that ONT with R7.3 flow cells generated more continuous assemblies than those derived from PacBio Sequel, despite homopolymer-based assembly errors and chimeric contigs [24]. The comparison between second-generation sequencing platforms showed that Illumina NovaSeq 6000 provided more accurate and continuous assembly in SGS-first pipelines, while MGI DNBSEQ-T7 offered a cost-effective alternative for the polishing process [24].

For human genome applications, Oxford Nanopore has demonstrated impressive capabilities, with one study achieving telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assembly quality with Q51 accuracy, resolving 30 full chromosome haplotypes with N50 greater than 144 Mb using PromethION R10.4.1 flow cells and specialized library preparation kits [21].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

Standardized protocols for 16S rRNA sequencing across platforms enable fair comparison in chemogenomics applications. The following experimental workflow outlines the key steps:

Diagram 1: 16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow

For Illumina, the V3 and V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene are amplified using specific primers (Klindworth et al., 2013) with Nextera XT Index Kit for multiplexing [19]. For PacBio and ONT, the full-length 16S rRNA gene is amplified using universal primers 27F and 1492R, producing ~1,500 bp fragments covering V1-V9 regions [19]. PacBio amplification typically uses 27 cycles with KAPA HiFi Hot Start DNA Polymerase, while ONT uses 40 cycles with verification on agarose gel [19].

Bioinformatic Processing Pipelines

The bioinformatic processing of sequencing data requires platform-specific approaches. For Illumina and PacBio, sequences are typically processed using the DADA2 pipeline in R, which includes quality assessment, adapter trimming, length filtering, and chimera removal, resulting in Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [19]. For ONT, due to higher error rates and lack of internal redundancy, denoising with DADA2 is not feasible; instead, sequences are often analyzed using Spaghetti, a custom pipeline that employs an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU)-based clustering approach [19]. Taxonomic annotation is commonly performed in QIIME2 using a Naïve Bayes classifier trained on the SILVA database, customized for each platform by incorporating specific primers and read length distributions [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NGS Experiments in Chemogenomics

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Platform Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) | DNA isolation from complex samples | All platforms [19] |

| 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Prep (Illumina) | Amplification and preparation of V3-V4 regions | Illumina [19] |

| SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (PacBio) | Library preparation for SMRT sequencing | PacBio [19] |

| 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-RAB204/SQK-16S024) | Full-length 16S amplification and barcoding | Oxford Nanopore [19] |

| Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) | Dual indices for sample multiplexing | Illumina [19] |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 (SQK-NBD109) | Multiplexing for native DNA sequencing | Oxford Nanopore [22] |

Platform Selection Guide for Chemogenomics Applications

Application-Based Recommendations

Large-Scale Population Studies in Drug Response: Illumina NovaSeq X Series provides the highest throughput and lowest cost per genome for large-scale sequencing projects, such as pharmacogenomics studies requiring thousands of whole genomes [18].

Complex Variant Detection in Disease Pathways: PacBio Revio and Vega systems offer comprehensive variant calling with high accuracy for all variant types (SNVs, indels, SVs), making them ideal for studying complex disease mechanisms and identifying rare variants in drug target genes [23] [20].

Metagenomics for Drug-Microbiome Interactions: Both PacBio and ONT provide superior species-level resolution for microbiome studies through full-length 16S sequencing, enabling precise characterization of drug-induced microbiome changes [19] [22].

Epigenomic Modifications in Chemical Exposure: ONT and PacBio enable direct detection of base modifications without special preparation, valuable for studying epigenetic changes in response to chemical exposures or drug treatments [21] [20].

Rapid Diagnostic and Translational Applications: ONT's real-time sequencing capabilities and portable formats (MinION) support rapid analysis for clinical chemogenomics applications, such as infectious disease diagnostics and resistance detection [26].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The NGS landscape continues to evolve with significant implications for chemogenomics research. Oxford Nanopore is developing a sample-to-answer offering combining integrated technologies, including the low-power 'SmidgION chip' to support lab-free sequencing in applied markets [26]. The company is also making strides into direct protein analysis—the next step in complete multiomic offering for chemogenomics [26]. PacBio continues to enhance its HiFi read technology with the Vega benchtop system making long-read sequencing more accessible to individual labs [20]. Illumina's NovaSeq X Series with XLEAP-SBS chemistry represents significant advances in throughput and efficiency for large-scale chemogenomics projects [18]. These technological advancements will further empower chemogenomics researchers to unravel the complex relationships between chemicals and biological systems, accelerating drug discovery and development.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics research, providing scientists with a powerful tool to unravel the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. This high-throughput technology enables the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, offering unprecedented insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the core NGS workflow is fundamental to designing robust experiments, identifying novel drug targets, and understanding mechanisms of drug action and resistance. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the basic NGS workflow, from initial sample preparation to final data generation, framed within the context of modern chemogenomics research.

Nucleic Acid Extraction

The NGS workflow begins with the isolation of genetic material. The quality and integrity of the starting material are critical to the success of the entire sequencing experiment. Nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) are isolated from a variety of sample types relevant to chemogenomics, including bulk tissue, individual cells, or biofluids [27]. After extraction, a quality control (QC) step is highly recommended. For assessing purity, UV spectrophotometry is commonly employed, while fluorometric methods are preferred for accurate nucleic acid quantitation [27]. Proper extraction ensures that the genetic material is free from contaminants that could inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions in library preparation.

Library Preparation

Library preparation is the process of converting a genomic DNA sample (or cDNA sample derived from RNA) into a library of fragments that can be sequenced on an NGS instrument [27]. This crucial step involves fragmenting the DNA or RNA samples into smaller pieces and then adding specialized adapters to the ends of these fragments [7]. These adapters are essential for several reasons: they enable the fragments to be bound to a sequencing flow cell, facilitate the amplification of the library, and provide a priming site for the sequencing chemistry. The choice of library preparation method (e.g., PCR-free, with PCR amplification, or using transposase-based "tagmentation") can impact the uniformity and coverage of the sequencing results, making it a key consideration for experimental design.

Sequencing

The prepared libraries are then loaded onto a sequencing platform. Illumina systems, among the most widely used, utilize proven sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry [28] [27]. This method detects single fluorescently-labeled nucleotides as they are incorporated by a DNA polymerase into growing DNA strands that are complementary to the template. The process is massively parallel, allowing millions to billions of DNA fragments to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run [28]. Key experimental parameters for this step are read length (the length of a DNA fragment that is read) and sequencing depth (the number of reads obtained per sample), which should be optimized for the specific research question [27]. Recent advancements, such as XLEAP-SBS chemistry, have delivered increased speed, greater fidelity, and higher throughput, with some production-scale instruments capable of generating up to 16 Terabases of data in a single run [28].

Sequencing Platform Comparison

The following table summarizes the characteristics of selected sequencing technologies, illustrating the landscape of options available to researchers.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Platform Technologies

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Amplification Type | Read Length | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [6] | Sequencing by Synthesis | Bridge PCR | 36-300 bp (Short Read) | Solid-phase sequencing using reversible dye-terminators. |

| Ion Torrent [6] | Sequencing by Synthesis | Emulsion PCR | 200-400 bp (Short Read) | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions released during nucleotide incorporation. |

| PacBio SMRT [6] | Sequencing by Synthesis | Without PCR | 10,000-25,000 bp (Long Read) | Real-time sequencing within zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs). |

| Oxford Nanopore [6] | Electrical Impedance Detection | Without PCR | 10,000-30,000 bp (Long Read) | Measures current changes as DNA/RNA strands pass through a nanopore. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The massive volume of raw data generated by an NGS instrument is a series of nucleotide bases (A, T, G, C) and associated quality scores, stored in FASTQ file format [29]. The analysis phase is where this data is transformed into biological insights. A basic analysis workflow for RNA-Seq, for example, starts with quality assessment of the FASTQ files, often using tools like FastQC [29]. If issues are detected, trimming may be performed to remove low-quality bases or adapter contamination. The subsequent steps typically involve alignment to a reference genome, quantification of gene expression, and finally, differential expression analysis and biological interpretation [29].

The field of bioinformatics has evolved to make NGS data analysis more accessible. User-friendly software and integrated data platforms now offer secondary and tertiary analysis tools, allowing researchers without extensive bioinformatics expertise to perform complex analyses [28] [27]. This is particularly powerful in chemogenomics, where the integration of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic data (multiomics) can provide a systems-level view of a drug's effect, accelerating biomarker discovery and the development of targeted therapies [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a Basic NGS Workflow

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA or RNA from various sample types (tissue, cells, biofluids). |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment nucleic acids and attach platform-specific adapters for sequencing. |

| Sequence Adapters | Short, known oligonucleotides that allow library fragments to bind to the flow cell and be amplified. |

| PCR Reagents | Enzymes and nucleotides for amplifying the library to generate sufficient material for sequencing. |

| Quality Control Kits | e.g., Fluorometric assays for accurate nucleic acid quantitation; electrophoretic assays for fragment size analysis. |

| Flow Cells | The surface (often a glass slide with patterned lanes) where library fragments are immobilized and sequenced. |

| Sequencing Reagents | Chemistry-specific kits containing enzymes, fluorescent nucleotides, and buffers for the sequencing-by-synthesis reaction. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of the four fundamental steps in the NGS workflow, highlighting the key input, process, and output at each stage.

The basic NGS workflow—extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis—forms the technological backbone of modern chemogenomics. As the field advances, the trends toward multiomic analysis, the integration of artificial intelligence, and the development of more efficient and cost-effective solutions are set to deepen our understanding of biology and further empower drug discovery and development [3] [6]. For researchers, a firm grasp of these foundational steps is essential for leveraging the full power of NGS to answer critical questions in precision medicine and therapeutic intervention.

Understanding Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing and Their Chemogenomic Applications

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics research, which focuses on understanding the complex interplay between genetic variation and drug response. The fundamental principle of NGS involves determining the nucleotide sequence of DNA or RNA molecules, enabling researchers to decode the genetic basis of disease and therapeutic outcomes [30]. Two primary technological approaches have emerged: short-read sequencing (SRS) and long-read sequencing (LRS). Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different applications within drug discovery and development [6] [31]. Short-read technologies, dominated by Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis platforms, generate highly accurate reads of 50-300 bases in length, while long-read technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) produce reads spanning thousands to tens of thousands of bases from single DNA molecules [32] [33]. The selection between these platforms depends on the specific research question, with short-reads excelling in variant detection frequency and long-reads providing superior resolution of complex genomic regions [34].

Fundamental Principles of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing

Short-Read Sequencing Technologies

2.1.1 Core Methodologies and Platforms

Short-read sequencing technologies employ parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously. The dominant platform is Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis, which utilizes bridge amplification on a flow cell surface followed by cyclic fluorescence detection using reversible dye terminators [6]. This process generates reads typically between 50-300 bases with exceptional accuracy (exceeding 99.9%) [34]. Other notable short-read platforms include Ion Torrent, which detects hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization; DNA nanoball sequencing that employs ligation-based chemistry on self-assembling DNA nanoballs; and the emerging sequencing-by-binding (SBB) technology used in PacBio's Onso system, which separates nucleotide binding from incorporation to achieve higher accuracy [6] [35]. These technologies share the common limitation of analyzing short DNA fragments that must be computationally reassembled, creating challenges in resolving repetitive regions and structural variations [32].

2.1.2 Experimental Workflow for Short-Read Sequencing

The standard workflow for short-read sequencing begins with DNA extraction and purification, followed by fragmentation through mechanical shearing, sonication, or enzymatic digestion to achieve appropriate fragment sizes (100-300 bp) [30]. Library preparation then involves end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation, with the optional addition of sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing. For targeted approaches, either hybridization capture with complementary probes or amplicon generation with specific primers enriches regions of interest [30]. The final library is quantified, normalized, and loaded onto the sequencing platform for massive parallel sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis follows, comprising base calling, read alignment to a reference genome, variant identification, and functional annotation [30].

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

2.2.1 Core Methodologies and Platforms

Long-read sequencing technologies directly sequence single DNA molecules without fragmentation, producing reads that span thousands to tens of thousands of bases. The two primary platforms are Pacific Biosciences' Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies' nanopore sequencing [31]. PacBio's SMRT technology immobilizes DNA polymerase at the bottom of nanometer-scale wells called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs). As nucleotides are incorporated into the growing DNA strand, their fluorescent labels are detected in real-time [33]. The circular consensus sequencing (CCS) approach, which generates HiFi reads, allows the polymerase to repeatedly traverse circularized DNA templates, achieving accuracies exceeding 99.9% with read lengths of 15,000-20,000 bases [33]. Oxford Nanopore's technology measures changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane, with different nucleotides creating distinctive current disruptions [31] [32]. This approach can produce extremely long reads (up to millions of bases) and detects native base modifications without additional processing.

2.2.2 Experimental Workflow for Long-Read Sequencing

The long-read sequencing workflow begins with high-molecular-weight DNA extraction to preserve molecule integrity. For PacBio systems, library preparation involves DNA repair, end-repair/A-tailing, SMRTbell adapter ligation to create circular templates, and size selection [33]. For Nanopore sequencing, library preparation includes end-repair/dA-tailing and adapter ligation with motor proteins that control DNA movement through pores [31]. Sequencing proceeds in real-time without amplification, preserving epigenetic modifications. Adaptive sampling can be employed for computational enrichment of targeted regions [31]. Bioinformatic analysis requires specialized tools for base calling, read alignment, and variant detection that account for the distinct error profiles and read lengths of long-read data.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Major Sequencing Platforms

| Parameter | Illumina (Short-Read) | PacBio HiFi (Long-Read) | Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-300 bp | 15,000-20,000 bp | 10,000-30,000+ bp |

| Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30+) | >99.9% (Q30+) | ~99% (Q20+) with latest chemistry |

| Primary Technology | Sequencing-by-synthesis | Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | Nanopore current detection |

| Amplification Required | Yes (bridge PCR) | No | No |

| Epigenetic Detection | Requires bisulfite conversion | Native detection via kinetics | Native detection via signal |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy, low cost | Long accurate reads, phasing | Ultra-long reads, portability |

| Main Limitation | Short reads, GC bias | Higher DNA input requirements | Higher raw error rate |

Comparative Analysis and Technical Considerations

Performance Benchmarking in Clinical Applications