Next-Generation Sequencing in Chemogenomics: Accelerating Precision Drug Target Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in modern chemogenomic approaches for drug target discovery and validation.

Next-Generation Sequencing in Chemogenomics: Accelerating Precision Drug Target Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in modern chemogenomic approaches for drug target discovery and validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how the integration of high-throughput genomic data with drug response profiling is revolutionizing the identification of novel therapeutic targets, repurposing existing drugs, and guiding personalized treatment strategies. The content spans from foundational concepts and methodological applications to practical troubleshooting and rigorous validation, providing a comprehensive resource for leveraging NGS to enhance the efficiency and success rate of the drug discovery pipeline.

The Chemogenomic Revolution: How NGS is Redefining Drug-Target Interaction Mapping

Chemogenomics represents a transformative paradigm in modern drug discovery, defined as the systematic study of the interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, informed by genomic data. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of chemogenomics and examines how next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies serve as a foundational pillar for accelerating target discovery research. By enabling high-throughput, genome-wide analysis, NGS provides an unprecedented capacity to identify and validate novel drug targets, stratify patient populations, and elucidate mechanisms of compound action. The integration of NGS with advanced computational analytics and automated screening platforms is reshaping the landscape of precision medicine and therapeutic development, offering researchers powerful methodologies to navigate the complexity of biological systems and chemical space.

Chemogenomics is an interdisciplinary field that investigates the systematic relationship between small molecules and their biological targets on a genome-wide scale. This approach operates on the fundamental premise that all drugs and bioactive compounds interact with specific gene products or cellular pathways, creating a complex network of chemical-biological interactions. The primary objective of chemogenomics is to comprehensively map these interactions to facilitate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents and elucidate biological pathways.

The convergence of genomic data and compound screening represents a paradigm shift from traditional reductionist approaches in drug discovery toward a more holistic, systems-level understanding of drug action. This integrated framework allows researchers to simultaneously explore multiple targets and pathways, identify polypharmacological effects, and repurpose existing compounds for new therapeutic indications. The core value proposition of chemogenomics lies in its ability to generate multidimensional datasets that connect chemical structures to biological functions, thereby accelerating the identification and validation of promising therapeutic candidates.

Within this conceptual framework, next-generation sequencing has emerged as a critical enabling technology that provides the genomic foundation for chemogenomic research. NGS technologies deliver the comprehensive genetic information necessary to understand disease mechanisms at the molecular level, identify druggable targets, and predict compound efficacy and toxicity profiles. The synergy between high-throughput sequencing and chemical screening establishes a powerful discovery platform for personalized medicine and targeted therapeutic development.

The Role of NGS in Modern Chemogenomics

Next-generation sequencing technologies have fundamentally transformed chemogenomic research by providing unprecedented access to genomic information at multiple molecular levels. The application of NGS in chemogenomics spans the entire drug discovery pipeline, from initial target identification to clinical trial optimization, through several distinct mechanistic approaches:

Target Identification and Validation: NGS enables comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic profiling to identify disease-associated genes and pathways that represent potential therapeutic targets. By sequencing entire genomes or exomes from patient cohorts, researchers can detect genetic variants, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs) that correlate with disease phenotypes [1]. This variant-to-function approach facilitates the prioritization of candidate drug targets based on human genetic evidence. Furthermore, through the analysis of loss-of-function (LoF) mutations in human populations, NGS provides a powerful method for target validation by revealing the phenotypic consequences of target modulation in humans [2].

Mechanism of Action Studies: Chemogenomics leverages NGS to elucidate the mechanisms through which small molecules exert their biological effects. Transcriptomic profiling using RNA-seq following compound treatment reveals gene expression signatures that can indicate the pathways affected by drug action [3]. Additionally, integrating epigenomic sequencing techniques, such as ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq, allows researchers to characterize compound-induced changes in chromatin accessibility and histone modifications, providing insights into epigenetic mechanisms of drug action [1] [4].

Biomarker Discovery for Patient Stratification: A critical application of NGS in chemogenomics is the identification of predictive biomarkers that enable patient selection for targeted therapies. By sequencing tumor genomes, for example, researchers can discover genetic alterations that predict response to specific compounds, facilitating the development of companion diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies [5] [2]. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology, where NGS-based liquid biopsies can detect tumor-derived DNA in blood samples, allowing for non-invasive monitoring of treatment response and disease progression [2].

The scalability and declining cost of NGS technologies have made large-scale chemogenomic studies feasible, enabling researchers to generate comprehensive datasets that connect genetic variation with compound sensitivity across diverse cellular contexts [6] [7]. This data-rich environment, combined with advanced computational methods, is accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic opportunities and enhancing our understanding of drug-target interactions across the human genome.

NGS Technologies and Methodologies for Chemogenomic Research

The successful implementation of chemogenomic approaches requires the strategic selection and application of appropriate NGS methodologies. The rapidly evolving landscape of sequencing technologies offers diverse platforms with complementary strengths, enabling researchers to address specific biological questions in chemogenomics. The table below summarizes the principal NGS technologies and their applications in chemogenomic research:

Table 1: Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies in Chemogenomics

| Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Key Applications in Chemogenomics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [1] | Sequencing by synthesis with reversible dye terminators | 36-300 bp (short-read) | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, target discovery, variant identification | Short reads may challenge structural variant detection and haplotype phasing |

| Ion Torrent [1] | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions | 200-400 bp (short-read) | Targeted sequencing, gene panel analysis, pharmacogenomics | Homopolymer sequence errors, lower throughput compared to Illumina |

| PacBio SMRT [1] | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp (long-read) | Full-length transcript sequencing, resolving complex genomic regions, structural variation analysis | Higher cost per sample, lower throughput than short-read platforms |

| Oxford Nanopore [8] [1] | Nanopore electrical signal detection | 10,000-30,000 bp (long-read) | Real-time sequencing, direct RNA sequencing, metagenomic analysis | Higher error rate (~15%) requiring computational correction |

| 454 Pyrosequencing [1] | Detection of pyrophosphate release | 400-1000 bp | Previously used for targeted sequencing and transcriptomics | Obsolete technology; homopolymer errors |

Experimental Design Considerations

The design of NGS experiments for chemogenomic research requires careful consideration of multiple factors to ensure biologically meaningful results:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control: The foundation of any successful NGS experiment lies in sample quality. For chemogenomic compound screens, this typically involves treating cell lines, organoids, or primary cells with compound libraries at various concentrations and time points. DNA or RNA extraction should follow standardized protocols with rigorous quality control measures. DNA integrity should be assessed using methods such as agarose gel electrophoresis or fragment analyzers, with RNA integrity numbers (RIN) >8.0 recommended for transcriptomic studies [3]. Accurate quantification using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) is essential for precise library preparation.

Library Preparation Strategies: Library construction approaches must align with experimental objectives. For whole genome sequencing (WGS), fragmentation and size selection optimize coverage uniformity, while for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), mRNA enrichment via poly-A selection or ribosomal RNA depletion captures the transcriptome of interest [1]. Targeted sequencing approaches utilizing hybrid capture or amplicon-based methods enhance sequencing depth for specific genomic regions, making them cost-effective for focused compound screens [7]. The integration of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during library preparation helps control for amplification biases and improves quantification accuracy.

Sequencing Depth and Coverage: Appropriate sequencing depth is critical for detecting genetic variants and quantifying gene expression changes in response to compound treatment. For WGS, 30-50x coverage is typically recommended for variant detection, while RNA-seq experiments generally require 20-50 million reads per sample for robust transcript quantification [1]. Targeted sequencing panels require significantly higher coverage (500-1000x) to detect low-frequency variants in heterogeneous samples, such as tumor biopsies or compound-resistant cell populations.

Advanced Methodologies for Enhanced Resolution

Single-Cell Sequencing: The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized chemogenomics by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity in compound responses [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying rare cell populations with differential compound sensitivity, understanding resistance mechanisms, and characterizing tumor microenvironment dynamics. Experimental workflows typically involve cell dissociation, single-cell isolation (via droplet-based or plate-based platforms), reverse transcription, library preparation, and sequencing. The integration of scRNA-seq with compound screening creates powerful high-dimensional datasets that connect cellular phenotypes with transcriptional responses to therapeutic agents.

Multiomic Integration: Contemporary chemogenomic research increasingly employs multiomic approaches that combine genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data from the same samples [4]. This integrated perspective provides a more comprehensive understanding of compound mechanisms of action and enables the identification of master regulators that coordinate cellular responses to chemical perturbations. Experimental designs for multiomic studies require careful planning to ensure sample compatibility across sequencing assays and computational methods for data integration.

Spatial Transcriptomics: The emerging field of spatial transcriptomics adds geographical context to gene expression data, preserving the architectural organization of tissues during sequencing [4]. For chemogenomics, this technology enables the visualization of compound distribution and activity within complex tissue environments, such as tumor sections or organoid models. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding tissue penetration, microenvironment-specific effects, and heterogeneous responses to therapeutic compounds.

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

The integration of NGS into chemogenomic research requires standardized experimental workflows that ensure reproducibility and data quality. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies that combine compound screening with genomic analysis.

High-Throughput Compound Screening with NGS Readout

Objective: To identify compounds that induce specific transcriptional signatures or genetic vulnerabilities in disease models.

Materials:

- Cell line or organoid model of interest

- Compound library (e.g., small molecules, FDA-approved drugs)

- Cell culture reagents and equipment

- RNA/DNA extraction kits (e.g., Corning Clean-up Kits) [2]

- Library preparation reagents (e.g., Illumina, Twist Bioscience, Pillar Biosciences) [9]

- Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel) [1]

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Compound Treatment:

- Seed cells in 384-well plates at optimized densities (e.g., 1,000-5,000 cells/well)

- Treat with compound library across a concentration range (typically 1 nM-10 μM) with appropriate controls (DMSO vehicle)

- Incubate for predetermined duration (24-72 hours) based on biological context

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Lyse cells directly in plates using TRIzol or similar reagents

- Extract total RNA/DNA following manufacturer protocols

- Assess quality and quantity using Fragment Analyzer or Bioanalyzer

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For transcriptomic analysis: Perform RNA-seq library preparation using poly-A enrichment or rRNA depletion

- For genomic analysis: Prepare whole genome or targeted sequencing libraries

- Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification biases

- Perform quality control on libraries using qPCR or Bioanalyzer

- Sequence on appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina for short-read, PacBio for isoform resolution)

Data Analysis:

- Align sequences to reference genome using STAR or HISAT2 (RNA-seq) or BWA (DNA-seq)

- Quantify gene expression (e.g., using featureCounts) or identify genetic variants (e.g., using GATK)

- Perform differential expression/abundance analysis comparing compound-treated vs. control samples

- Identify gene signatures and pathways enriched in compound-treated samples

This integrated approach enables the systematic identification of compounds that modulate specific pathways or genetic networks, facilitating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents and the repurposing of existing drugs.

Patient-Derived Organoid Screening with NGS Analysis

Objective: To evaluate compound efficacy in physiologically relevant patient-derived models and identify biomarkers of response.

Materials:

- Patient-derived organoids (PDOs)

- Corning organoid culture products (specialized surfaces and media) [2]

- Compound library of interest

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- Library preparation reagents

- Single-cell RNA-seq reagents if applicable (e.g., 10x Genomics) [9]

Procedure:

- Organoid Culture and Compound Treatment:

- Maintain PDOs in Corning Matrigel or similar extracellular matrix with optimized culture media [2]

- Dissociate organoids into single cells or small clusters for uniform plating

- Seed in 96-well or 384-well format suitable for high-throughput screening

- Treat with test compounds across concentration gradients (typically 5-8 points)

- Incubate for 5-14 days depending on organoid growth characteristics

Viability Assessment and Sample Collection:

- Measure cell viability using ATP-based (CellTiter-Glo) or similar assays at endpoint

- Collect organoids for genomic analysis at predetermined time points (e.g., 24h for early response markers)

- Preserve samples in RNA/DNA stabilization reagents

NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract high-quality RNA/DNA using column-based methods

- Prepare sequencing libraries focusing on targeted panels or whole transcriptome

- For heterogeneous responses, employ single-cell RNA-seq to resolve cellular subtypes

- Sequence using appropriate platform and depth

Data Integration and Analysis:

- Process sequencing data to quantify gene expression or genetic variants

- Correlate compound sensitivity (IC50 values) with genomic features

- Identify gene expression signatures predictive of compound response

- Validate biomarkers in independent patient cohorts

This protocol leverages the physiological relevance of patient-derived organoids with the comprehensive profiling capabilities of NGS to advance personalized medicine approaches and biomarker discovery.

Data Analysis and Computational Approaches

The integration of NGS data with chemogenomic screening generates complex, high-dimensional datasets that require sophisticated computational methods for meaningful biological interpretation. The analysis workflow typically involves multiple stages, from primary processing to advanced integrative modeling.

Primary and Secondary Analysis

The initial phases of NGS data analysis focus on converting raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information:

Primary Analysis: This stage involves base calling, quality control, and demultiplexing. Modern NGS platforms perform real-time base calling during sequencing, generating FASTQ files containing sequence reads with associated quality scores [1]. Quality assessment tools such as FastQC provide essential metrics on read quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and sequence duplication levels. For chemogenomic screens involving multiple compounds and conditions, careful demultiplexing is critical to maintain sample identity throughout the analysis pipeline.

Secondary Analysis: The core of NGS data processing occurs at this stage, where sequences are aligned to reference genomes and relevant features are quantified. For DNA-seq data, this involves:

- Read alignment using tools like BWA-MEM or Bowtie2

- Duplicate marking to identify PCR artifacts

- Variant calling using GATK or similar pipelines to identify SNPs, indels, and structural variants

- Annotation of variants with functional predictions using tools like SnpEff or VEP

For RNA-seq data from compound-treated samples, secondary analysis includes:

- Transcript quantification using alignment-based (STAR, HISAT2) or alignment-free (Salmon, kallisto) methods

- Differential expression analysis using packages such as DESeq2 or edgeR to identify compound-induced transcriptional changes

- Alternative splicing analysis using tools like MAJIQ or rMATS to detect compound-mediated effects on RNA processing

The output from secondary analysis provides the fundamental datasets for exploring compound-gene relationships and identifying mechanisms of action.

Tertiary Analysis and Integration

Advanced computational methods enable the extraction of biologically meaningful insights from processed NGS data:

Pathway and Enrichment Analysis: Compound-induced gene expression signatures are interpreted in the context of biological pathways using tools like GSEA, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), or Enrichr. These analyses identify pathways significantly modulated by chemical treatment, providing insights into mechanisms of action and potential off-target effects [3].

Network-Based Approaches: Graph theory-based methods construct interaction networks connecting compounds, genes, and phenotypes. These approaches can identify hub genes that represent key regulators of compound response and reveal modular organization within chemogenomic datasets [4].

Machine Learning and AI Integration: The scale and complexity of chemogenomic data make them ideally suited for machine learning approaches. Supervised methods (e.g., random forests, support vector machines) can predict compound efficacy based on genomic features, while unsupervised approaches (e.g., clustering, autoencoders) can identify novel compound groupings based on shared genomic responses [7] [4]. Deep learning models, particularly graph neural networks, are increasingly applied to integrate chemical structure information with genomic responses for improved prediction of compound properties and mechanisms.

Multiomic Data Integration: Advanced statistical methods, including multivariate analysis and tensor decomposition, enable the integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data from compound screens. These approaches reveal coordinated changes across molecular layers and provide a systems-level understanding of drug action [4].

The successful implementation of these computational workflows requires robust infrastructure, including high-performance computing resources, cloud-based platforms for collaborative analysis, and specialized bioinformatics expertise [9] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Enhanced Chemogenomics

The implementation of robust chemogenomic screens with NGS readouts depends on specialized reagents and tools that ensure experimental reproducibility and data quality. The table below outlines essential research reagent solutions and their applications in NGS-enhanced chemogenomics:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-Enhanced Chemogenomic Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina Nextera, Pillar Biosciences OncoPrime, Twist NGS Library Preparation [9] | Convert nucleic acids to sequencing-ready libraries | Streamlined workflows, minimal hands-on time, compatibility with automation |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina TruSight Oncology, IDT xGen Panels, Corning SeqCentral [9] [2] | Selective capture of genomic regions of interest | Comprehensive coverage of disease-relevant genes, uniform coverage |

| Automation Reagents | Beckman Coulter Biomek NGeniuS reagents [9] | Enable automated liquid handling for high-throughput screens | Reduced manual intervention, improved reproducibility, integrated quality control |

| Cell Culture Systems | Corning Matrigel, Elplasia plates, specialized media [2] | Support 3D culture of organoids and complex models | Physiological relevance, maintenance of genomic stability, high-throughput compatibility |

| Nucleic Acid Stabilization | Corning DNA/RNA Shield, PAXgene RNA tubes | Preserve sample integrity during collection and storage | Prevent degradation, maintain sample quality for downstream sequencing |

| Single-Cell Reagents | 10x Genomics Single Cell Gene Expression, Parse Biosciences kits [9] | Enable single-cell resolution in compound screens | Cellular heterogeneity resolution, high cell throughput, multiomic capabilities |

The selection of appropriate reagents should be guided by experimental objectives, throughput requirements, and compatibility with existing laboratory infrastructure. For high-throughput chemogenomic screens, integration with automated liquid handling systems is particularly valuable for ensuring reproducibility and managing large sample numbers [9]. Quality control measures should be implemented at each stage of the workflow, from nucleic acid extraction through library preparation, to ensure the generation of high-quality sequencing data.

The convergence of genomic data and compound screening through chemogenomics represents a fundamental shift in drug discovery methodology. Next-generation sequencing technologies serve as the critical enabling platform that provides the comprehensive molecular profiling necessary to connect chemical compounds with their biological targets and mechanisms of action. The integration of diverse NGS methodologies—from whole genome sequencing to single-cell transcriptomics—with high-throughput compound screening creates powerful datasets that accelerate target identification, validation, and biomarker discovery.

The future of chemogenomics will be shaped by continued technological advancements in sequencing, particularly in the realms of long-read technologies, real-time sequencing, and multiomic integration. The growing application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze complex chemogenomic datasets will further enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights and predict compound properties. Additionally, the trend toward decentralized sequencing and the development of more accessible platforms will democratize chemogenomic approaches, enabling broader adoption across the research community.

As these technologies mature, chemogenomics will increasingly bridge the gap between basic research and clinical application, enabling the development of more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies. The systematic mapping of chemical-biological interactions across the genome will continue to reveal novel therapeutic opportunities and advance our fundamental understanding of disease mechanisms, ultimately transforming the landscape of drug discovery and precision medicine.

Visualizations

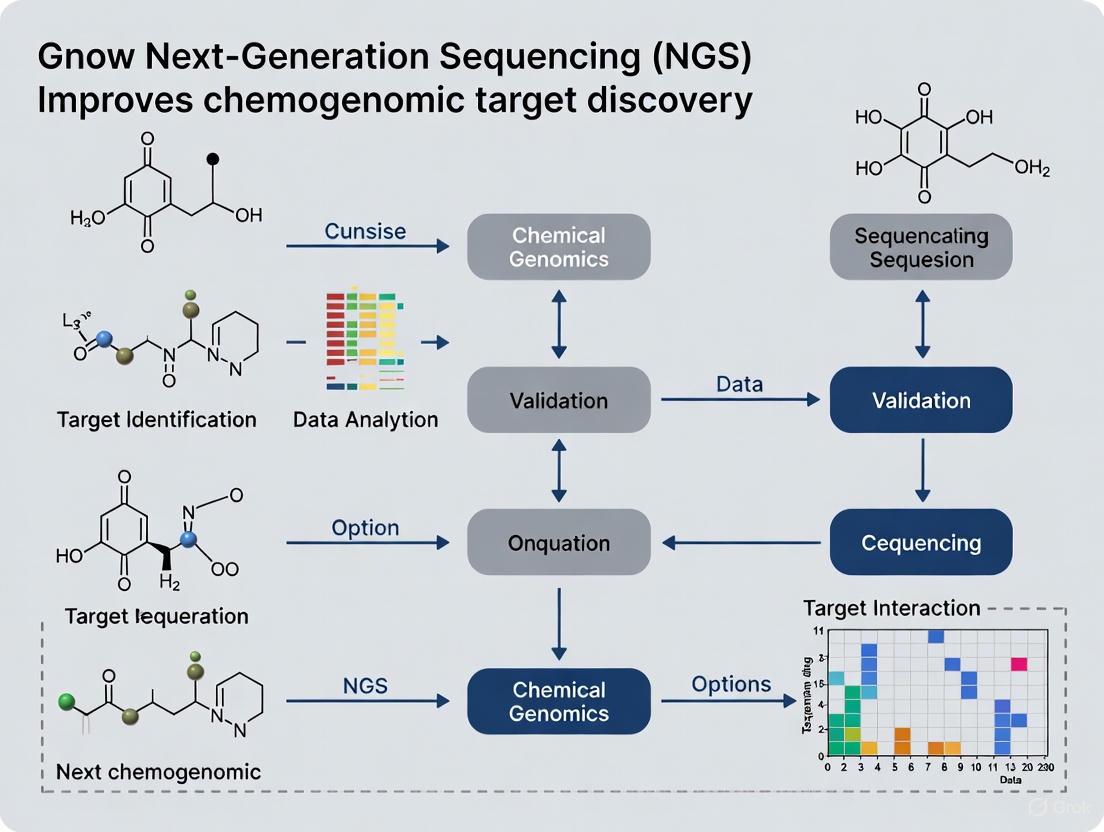

NGS-Enhanced Chemogenomics Workflow

Core Chemogenomics Concept

The High-Throughput Advantage of NGS in Population-Wide Genetic Association Studies

Genetic association studies have long been the cornerstone of understanding the genetic architecture of complex diseases and traits. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of common genetic variants, usually single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), associated with common diseases and traits [10] [11] [12]. However, the transition to next-generation sequencing (NGS), also known as high-throughput sequencing, represents a paradigm shift that is transforming population genetics and its application to chemogenomic target discovery [2] [1]. This technological evolution is moving beyond the limitations of traditional GWAS by providing a more comprehensive view of genetic variation across entire genomes of large populations.

The fundamental advantage of NGS in this context lies in its ability to sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously in a massively parallel manner, providing unprecedented resolution for identifying genetic contributors to disease and drug response [1] [13]. Unlike earlier methods that relied on pre-selected variants, NGS enables an unbiased discovery approach that captures a broader spectrum of genetic variations, including rare variants with potentially larger effect sizes. For drug development professionals, this enhanced resolution is critical for identifying novel therapeutic targets, understanding drug mechanisms, and ultimately developing more effective personalized treatment strategies [14] [2].

The Technical Evolution: From GWAS Limitations to NGS Solutions

Traditional GWAS Approach and Its Constraints

Traditional GWAS methodologies have operated by genotyping hundreds of thousands of pre-selected SNPs across hundreds to thousands of DNA samples using microarray technology [10]. After stringent quality control procedures, each variant is statistically analyzed against traits of interest, with researchers often collaborating to combine data from multiple studies. While this approach has generated numerous robust associations for various traits and diseases, it faces significant limitations:

- Limited Variant Coverage: GWAS typically captures only common variants (usually with frequencies >5%) and relies on linkage disequilibrium to implicate genomic regions rather than identifying causal variants directly [10] [11].

- Incomplete Heritability Explanation: Despite identifying numerous associations, the vast majority of heritability for common diseases remains unexplained. For example, while 70 variants associated with type 2 diabetes have been identified, they explain only a fraction of the disease's heritability [10].

- Modest Effect Sizes: Most variants identified through GWAS confer very small effects, with odds ratios typically below 2.0 for disease associations and effects of <0.1 standard deviation for continuous traits [10].

- Limited Clinical Utility: The predictive power of GWAS-identified variants has generally proven insufficient for clinical decision-making. For instance, combining the 40 strongest type 2 diabetes variants yields a receiver operator curve area under the curve value of only 0.63, where 0.8 is considered clinically useful [10].

The NGS Technological Advantage

Next-generation sequencing technologies have overcome these limitations through several fundamental technological advances that enable comprehensive genomic assessment:

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Approaches in Population Studies

| Feature | Traditional GWAS | NGS-Based Association Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Coverage | Pre-selected common variants (typically >5% MAF) | Comprehensive assessment of common, low-frequency, and rare variants |

| Resolution | Indirect association via linkage disequilibrium | Direct detection of potentially causal variants |

| Structural Variant Detection | Limited capability | Comprehensive identification of structural variants |

| Novel Discovery Potential | Restricted to known variants | Unbiased discovery of novel associations |

| Sample Throughput | Hundreds to thousands | Thousands to millions via scalable workflows |

NGS platforms leverage different technological principles to achieve high-throughput sequencing. Illumina sequencing utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye terminators, enabling highly accurate short reads [1] [13]. In contrast, Oxford Nanopore sequencing employs nanopore-based detection of electrical signal changes as DNA strands pass through protein pores, enabling real-time sequencing with long reads [1] [13]. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) technology uses single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing with fluorescently labeled nucleotides to generate long reads with high accuracy [1] [13]. Each platform offers distinct advantages in read length, accuracy, throughput, and application suitability, allowing researchers to select the optimal technology for specific association study designs.

NGS Methodologies for Population-Wide Genetic Association Studies

Core Experimental Workflows

Implementing NGS in population-wide genetic association studies requires carefully designed experimental protocols that ensure data quality and reproducibility. The following workflow outlines the standard approach for large-scale NGS association studies:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for NGS-based population genetic association studies

Sample Collection and Library Preparation

Population-scale NGS studies begin with careful sample collection and phenotypic characterization. For drug discovery applications, this often involves recruiting individuals with detailed clinical information, treatment responses, and disease subtypes [2]. DNA extraction follows stringent quality control measures to ensure high molecular weight and purity.

Library preparation involves fragmenting DNA, attaching platform-specific adapters, and often incorporating molecular barcodes to enable sample multiplexing. Modern library prep protocols have been optimized for automation, enabling processing of thousands of samples with minimal hands-on time and batch effects [15]. The emergence of PCR-free library preparation methods has further reduced amplification biases, particularly important for accurate allele frequency estimation in population studies.

Sequencing and Primary Analysis

The prepared libraries are sequenced using high-throughput NGS platforms, with Illumina systems like the NovaSeq X Series being particularly prominent for population-scale studies due to their ability to generate up to 16 Tb output and 52 billion single reads per dual flow cell run [15]. The massive parallelization enables sequencing of entire cohorts in a cost-effective manner.

Primary data analysis involves base calling, demultiplexing, and quality control. For large-scale studies, automated pipelines like Illumina's DRAGEN platform can process NGS data for an entire human genome at 30x coverage in approximately 25 minutes, enabling rapid turnaround times [15]. Quality metrics including base quality scores, coverage uniformity, and contamination checks are essential at this stage to ensure data integrity before downstream analysis.

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Variant Calling and Annotation

The core analytical challenge in NGS-based association studies involves accurate variant calling across diverse samples. This process typically involves:

- Read alignment to a reference genome using optimized aligners like BWA-MEM or HISAT2

- Post-alignment processing including duplicate marking, base quality score recalibration, and indel realignment

- Variant calling using methods like GATK HaplotypeCaller or Samtools mpileup

- Variant quality score recalibration to filter false positives

- Functional annotation using databases like dbSNP, gnomAD, and ClinVar

For association studies, joint calling across all samples improves sensitivity for low-frequency variants while maintaining specificity. Annotation pipelines then prioritize variants based on predicted functional impact (e.g., loss-of-function, missense), evolutionary conservation, and regulatory potential.

Association Testing and Integration

The final analytical stage tests for associations between genetic variants and phenotypes of interest:

Figure 2: Association testing framework for NGS population data

Standard association tests include:

- Single-variant tests for common variants (MAF > 1%)

- Burden tests and SKAT tests for rare variant aggregation within genes

- Mixed models to account for population structure and relatedness

For drug discovery applications, phenotypes of particular interest include drug response metrics, adverse event occurrence, and biomarker levels. Significant associations are then prioritized based on effect size, functional potential, and biological plausibility for further validation.

Application to Chemogenomic Target Discovery

Enhancing Target Identification and Validation

The integration of NGS into chemogenomics has revolutionized early drug discovery by providing comprehensive genetic insights into drug-target interactions [14]. Chemogenomic approaches leverage large-scale chemical and genetic information to systematically map interactions between compounds and their cellular targets, and NGS provides the genetic foundation for these maps.

In target identification, NGS enables association studies that link genetic variations in potential drug targets with disease susceptibility or progression. For example, sequencing individuals at extreme ends of a disease phenotype can reveal loss-of-function mutations in specific genes that confer protection or increased risk, providing strong genetic validation for those targets [2]. This approach, known as human genetics-driven target discovery, has gained prominence because targets with genetic support have significantly higher success rates in clinical development.

For target validation, NGS facilitates functional genomics screens using CRISPR-based approaches where guide RNAs are tracked via sequencing to identify genes essential for cell survival or drug response in specific contexts. When applied across hundreds of cell lines or primary patient samples, these screens generate comprehensive maps of gene essentiality and drug-gene interactions that inform target prioritization.

Practical Research Toolkit

Implementing NGS-based association studies for chemogenomic applications requires specific research tools and resources:

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for NGS-Based Chemogenomic Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X Series, PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Large-scale whole genome sequencing, long-read for complex regions |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep, Corning PCR microplates | High-quality library preparation, minimization of batch effects |

| Automation Systems | Liquid handling robots, automated library prep systems | Scalable processing of thousands of samples |

| Analysis Platforms | Illumina DRAGEN, Illumina Connected Analytics | Secondary analysis, secure data management and collaboration |

| Functional Validation | Patient-derived organoids, CRISPR screening systems | Experimental validation of target-disease relationships |

The selection of appropriate tools depends on study objectives, with whole-genome sequencing providing the most comprehensive variant detection while targeted sequencing approaches offer more cost-effective deep coverage of specific gene panels relevant to particular disease areas [2] [13].

Case Study: Malaria Drug Resistance Mechanisms

A compelling example of NGS application in chemogenomics comes from malaria research, where forward genetic screening using piggyBac mutagenesis combined with NGS revealed intricate networks of genetic factors influencing parasite responses to dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ) [16]. Researchers created a library of isogenic Plasmodium falciparum mutants with random insertions covering approximately 11% of the genome, then exposed these mutants to sublethal drug concentrations.

The chemogenomic profiles generated through quantitative insertion site sequencing (QIseq) identified mutants with altered drug sensitivity, revealing genes involved in proteasome-mediated degradation and lipid metabolism as critical factors in antimalarial drug response [16]. This systematic approach uncovered both shared and distinct genetic networks influencing sensitivity to different drug classes, providing new insights into potential combination therapies and drug targets for overcoming artemisinin resistance.

The integration of high-throughput NGS technologies into population-wide genetic association studies has fundamentally transformed chemogenomic target discovery research. By providing comprehensive maps of genetic variation and its functional consequences across diverse populations, NGS enables more genetically validated targets with higher potential clinical success. The scalability of modern sequencing platforms continues to improve, with costs decreasing while data quality increases, making increasingly large sample sizes feasible for detecting subtle genetic effects relevant to drug response.

Future advancements in long-read sequencing, single-cell sequencing, and spatial transcriptomics will further refine our understanding of genetic contributions to disease and treatment response [1]. Meanwhile, improvements in bioinformatics pipelines and AI-driven variant interpretation will accelerate the translation of genetic associations into validated drug targets [2] [3]. For drug development professionals, these technological advances promise to enhance the efficiency of the drug discovery pipeline, ultimately delivering more targeted therapies with improved success rates in clinical development.

As NGS technologies continue to evolve, their integration with other data modalities including proteomics, metabolomics, and clinical data will create increasingly comprehensive maps of disease biology and therapeutic opportunities. This multi-omics approach, grounded in high-quality genetic data from diverse populations, represents the future of targeted therapeutic development and personalized medicine.

The drug discovery process has long been a crucial and cost-intensive endeavor, with a clinical success rate of approval historically as low as 19% [14]. Target identification and validation form the critical foundation of this pipeline, representing the stage where the journey toward a new therapeutic begins [14]. Traditionally reliant on wet-lab experiments, this process has been transformed by the advent of in silico methods and the availability of big data in the form of bioinformatics and genetic databases [14]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a cornerstone technology within this transformation, revolutionizing genomics research by providing ultra-high throughput, scalability, and speed for determining the order of nucleotides in entire genomes or targeted regions of DNA or RNA [17].

NGS enables the rapid sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, offering comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [1]. This technological capability is particularly powerful when applied within a chemogenomic framework, which utilizes small molecules as tools to establish the relationship between a target and a phenotype [18]. This review explores how NGS technologies are specifically improving chemogenomic target discovery research, providing detailed methodologies, visual workflows, and reagent toolkits to bridge the gap between big genomic data and actionable biological insights for drug development professionals.

NGS-Enhanced Chemogenomic Approaches

Chemogenomics operates through two primary directional paradigms: "reverse chemogenomics," which begins by investigating the biological activity of enzyme inhibitors, and "forward chemogenomics," which identifies the relevant target(s) of a pharmacologically active small molecule [18]. NGS technologies profoundly enhance both approaches by adding deep genomic context to functional screening data.

The integration of targeted NGS (tNGS) with ex vivo drug sensitivity and resistance profiling (DSRP) represents a powerful chemogenomic approach to proposing patient-specific treatment options. A clinical study in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) demonstrated the feasibility of this combined method, where a tailored treatment strategy could be achieved for 85% of patients (47 of 55) within 21 days for a majority of cases [19]. This chemogenomic analysis identified mutations in 63 genes, with a median of 3.8 mutated genes per patient, and actionable mutations were found in 94% of patients [19]. The high variability in drug response observed across all samples underscored the necessity of combining genomic and functional data for effective target validation [19].

Table 1: Key NGS Platforms for Chemogenomic Applications

| Platform/Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Primary Applications in Target ID | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) | 36-300 bp (short-read) | Whole-genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, epigenetic profiling [1] [17] | Ultra-high throughput, cost-effective, broad dynamic range [17] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp (long-read) | De novo genome assembly, resolving complex genomic regions [1] | Long reads capable of spanning repetitive regions and structural variants |

| Oxford Nanopore | Electrical impedance detection via nanopores | 10,000-30,000 bp (long-read) | Real-time pathogen identification, metagenomic studies [1] | Long reads, portability, direct RNA sequencing capability |

| Targeted NGS (tNGS) | Varies by platform | Varies | Focused sequencing of candidate genomic regions, actionable mutations [19] [20] | High sensitivity and specificity for regions of interest, cost-effective for clinical applications [20] |

NGS Methodologies for Target Identification and Validation

Population-Scale Genomic Studies

Population-scale sequencing with paired electronic health records (EHRs) has become a powerful strategy for identifying novel drug targets. The pioneering DiscovEHR study, a collaboration between Regeneron and Geisinger Health System, performed whole-exome sequencing on 50,726 subjects with paired EHRs [21]. By leveraging rich phenotype information such as lipid levels extracted from EHRs, this study examined associations between loss-of-function (LoF) variants in candidate drug targets and selected phenotypes of interest [21].

The methodology confirmed known associations, such as those between pLoF mutations in NPC1L1 (the drug target of ezetimibe) and PCSK9 (the drug target of alirocumab and evolocumab) with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels [21]. Furthermore, it uncovered novel associations, such as LoF variants in CSF2RB with basophil and eosinophil counts, revealing new potential therapeutic targets [21].

Experimental Protocol: Population-Scale Genetic Association

- Cohort Selection: Recruit large, well-phenotyped population cohorts with linked EHRs [21].

- Sequencing: Perform whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing using platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq [21].

- Variant Calling: Identify and annotate LoF variants, missense mutations, and other potentially functional genetic changes.

- Phenotype Extraction: Use natural language processing and structured data queries to extract quantitative traits and disease diagnoses from EHRs.

- Association Analysis: Conduct statistical tests (e.g., regression analyses) correlating specific genetic variants with phenotypes of interest, correcting for multiple testing [21].

- Target Prioritization: Prioritize genes where LoF variants are associated with favorable disease-relevant phenotypes (e.g., reduced LDL levels, improved glycemic control) [21].

Extreme Phenotype Sequencing

Sequencing individuals at the extreme ends of phenotypic distributions provides an efficient strategy to overcome the challenge of large sample sizes. This approach focuses statistical power on individuals who are most likely to carry meaningful genetic variants with large effect sizes [21].

A notable example investigated the genetic causes of extreme bone density phenotypes. Research on a family with supernatural bone density identified mutations in the LRP5 gene, a component of the Wnt signaling pathway [21]. This discovery provided novel biological insights that catalyzed the development of therapies for osteoporosis by modulating the Wnt pathway [21].

Diagram 1: Extreme Phenotype Sequencing Workflow

Functional Chemogenomic Integration

The combination of tNGS with ex vivo DSRP represents a robust functional chemogenomic approach for validating targets and identifying effective therapies, particularly in complex diseases like cancer [19].

In a prospective study of relapsed/refractory AML patients, researchers performed both tNGS (focusing on known actionable mutations) and ex vivo DSRP (testing sensitivity to a panel of 76 drugs) on patient-derived blast cells [19]. A multidisciplinary review board integrated both datasets to propose a tailored treatment strategy (TTS). The study successfully achieved a TTS for 85% of included patients, with 36 of 47 proposals based on both genomic and functional data [19]. This integrated approach yielded more options and a better rationale for treatment selection than either method alone [19].

Experimental Protocol: Integrated tNGS and DSRP

- Sample Processing: Collect and process bone marrow or blood samples to isolate mononuclear cells or specific cell populations of interest [19].

- Targeted NGS: Perform tNGS using panels covering known actionable genes relevant to the disease (e.g., for AML: TP53, NRAS, NF1, IDH2, FLT3) [19].

- Ex Vivo DSRP: Plate isolated cells in multi-well plates and expose them to a panel of targeted therapies across a concentration gradient. Assess cell viability after 72-96 hours using assays like CellTiter-Glo [19].

- Data Integration: Calculate Z-scores for drug sensitivity (EC50) normalized to a reference population. Select drugs with Z-scores below a set threshold (e.g., -0.5) indicating superior sensitivity [19].

- Multidisciplinary Review: Convene a board of physicians and molecular biologists to integrate genomic and DSRP data, proposing mono or polytherapy strategies based on actionable mutations and ex vivo efficacy [19].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function in NGS-Enhanced Target ID |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera Flex | Fragment DNA/RNA and attach platform-specific adapters for sequencing [17] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | TruSight Oncology 500, Custom AML Panels | Selectively capture genomic regions of interest for targeted sequencing [22] [19] |

| Cell Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo, MTT Assay | Quantify cell viability and proliferation in ex vivo DSRP screens [19] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, PAXgene Blood RNA Kit | Isolve high-quality DNA/RNA from clinical samples (blood, tissue, BM) [19] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform, GATK, clusterProfiler | Process raw sequencing data, call variants, and perform pathway enrichment analysis [22] [23] |

Quantitative Data and Clinical Impact

The clinical impact of NGS-guided target discovery is demonstrated by quantitative outcomes from implemented studies. In the AML chemogenomics study, the integrated tNGS and DSRP approach resulted in a TTS that recommended on average 3-4 potentially active drugs per patient [19]. Notably, only five patient samples were resistant to the entire drug panel, highlighting the value of comprehensive profiling for identifying treatment options in refractory disease [19].

Of the 17 patients who received a TTS-guided treatment, objective responses were observed: four achieved complete remissions, one had a partial remission, and five showed decreased peripheral blast counts [19]. This demonstrates that NGS-facilitated, function-driven target validation can lead to meaningful clinical outcomes even in heavily pretreated populations.

Diagram 2: Integrated Chemogenomic Workflow

Next-generation sequencing has fundamentally transformed the landscape of target identification and validation within chemogenomics research. By enabling population-scale genetic studies, facilitating extreme phenotype analysis, and integrating with functional drug sensitivity testing, NGS provides a powerful suite of tools to bridge the gap between genomic big data and actionable therapeutic insights. The structured methodologies, reagent toolkits, and visual workflows presented in this technical guide provide researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for implementing these cutting-edge approaches. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, becoming more efficient and cost-effective, their role in validating targets with genetic evidence and functional support will undoubtedly expand, accelerating the development of more effective and personalized therapeutics.

In the modern drug discovery pipeline, the identification and validation of a drug target is a crucial, cost-intensive, and high-risk initial step [14]. Within this process, loss-of-function (LoF) mutations have emerged as powerful natural experiments for target hypothesis testing. These mutations, which reduce or eliminate the activity of a gene product, provide direct causal evidence about gene function and its relationship to disease phenotypes [24]. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our capacity to systematically identify these LoF mutations on a genome-wide scale, thereby fundamentally improving chemogenomic target discovery research [2].

Chemogenomics, the study of the interaction of functional genomics with chemical space, relies on high-quality genetic evidence to link targets to disease [14]. LoF mutations serve as critical natural knock-down models; if individuals carrying a LoF mutation in a specific gene exhibit a protective phenotype against a disease, this provides strong genetic validation that inhibiting the corresponding protein could be a safe and effective therapeutic strategy [2]. This case study explores the integrated experimental and computational methodologies for identifying LoF mutations through NGS, detailing how this approach de-risks the early stages of drug development and creates novel therapeutic hypotheses.

Technical Foundations: LoF Mutations and NGS Technology

Characterizing Loss-of-Function Mutations

Loss-of-function mutations disrupt the normal production or activity of a gene product, leading to partial or complete loss of biological activity [24]. The table below summarizes the major types and consequences of LoF mutations relevant to target discovery.

Table 1: Types and Consequences of Loss-of-Function Mutations

| Mutation Type | Molecular Consequence | Impact on Protein Function | Utility in Target Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsense | Introduces premature stop codon | Truncated, often degraded protein | High confidence in complete LoF; strong validation signal |

| Frameshift | Insertion/deletion shifts reading frame | Drastically altered amino acid sequence, often premature stop | High impact LoF; excellent for causal inference |

| Splice Site | Disrupts RNA splicing | Aberrant mRNA processing, non-functional protein | Can be tissue-specific; reveals critical functional domains |

| Missense | Amino acid substitution in critical domain | Reduced stability or catalytic activity | Partial LoF; useful for understanding structure-function |

| Regulatory/Epigenetic | Promoter/enhancer mutation or silencing | Reduced or eliminated transcription | Tissue-specific effects; identifies regulatory vulnerabilities |

The clinical and phenotypic data associated with individuals carrying these mutations provides invaluable insights for target selection. For instance, individuals with LoF mutations in the PCSK9 gene were found to have significantly lower LDL cholesterol levels and reduced incidence of coronary heart disease, directly validating PCSK9 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for cardiovascular disease [2].

NGS Platforms for LoF Mutation Detection

The selection of appropriate NGS technologies is fundamental to successful LoF mutation identification. Different sequencing platforms offer complementary strengths for various applications in target discovery.

Table 2: NGS Platform Comparison for LoF Mutation Detection

| Platform/Technology | Key Strengths | Limitations | Best Applications in LoF Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (Short-Read) | High accuracy (99.9%), low cost per base, high throughput | Shorter read lengths (75-300 bp) | Population-scale sequencing, targeted panels, variant validation |

| Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read) | Real-time sequencing, very long reads (100,000+ bp), portable | Higher error rates than Illumina | Resolving complex genomic regions, structural variants |

| Pacific Biosciences (Long-Read) | Long reads, high consensus accuracy | Lower throughput, higher cost | Phasing compound heterozygotes, splicing analysis |

| Targeted Panels (e.g., Haloplex, Ion Torrent) | Deep coverage of specific genes, cost-effective for focused studies | Limited to known genes | High-throughput screening of candidate target genes |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Comprehensive, hypothesis-free approach | Higher cost, complex data analysis | Novel gene discovery, unbiased target identification |

The massively parallel architecture of NGS enables the concurrent analysis of millions of DNA fragments, providing the scalability needed for population-scale genetic studies [25]. This high-throughput capacity is essential for identifying rare LoF mutations with large effect sizes, which often provide the most compelling evidence for therapeutic target validation [2].

Integrated Experimental Design: From Sample to Target Hypothesis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for identifying and validating LoF mutations for target hypothesis testing:

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for LoF Mutation Discovery

Sample Selection and Cohort Design

Robust LoF discovery begins with strategic sample selection. Key considerations include:

- Extreme Phenotype Sampling: Selecting individuals at both ends of a disease spectrum increases power to detect rare large-effect LoF variants [26].

- Family-Based Designs: Sequencing affected and unaffected family members helps identify segregating LoF mutations in Mendelian disorders [26].

- Population Biobanks: Large-scale resources like the UK Biobank provide both genomic and rich phenotypic data for association studies [27].

- Diverse Ancestry: Including ethnically diverse cohorts ensures discoveries are generalizable and improves fine-mapping resolution [25].

For target discovery, special attention should be paid to individuals exhibiting protective phenotypes against common diseases, as LoF mutations in these cases can directly nominate therapeutic targets [2].

Methodologies: NGS Experimental Protocols

DNA Sequencing Approaches for LoF Detection

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Protocol: WGS provides comprehensive coverage of both coding and non-coding regions, enabling discovery of LoF mutations beyond protein-coding exons [25].

- Library Preparation: Fragment genomic DNA (100-1000bp), perform end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using validated kits (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) [28].

- Sequencing: Sequence to minimum 30x mean coverage using Illumina NovaSeq X or similar platform [28].

- Quality Control: Verify library concentration (Qubit), fragment size (TapeStation), and ensure >80% bases ≥Q30 [26].

Advantages: Captures structural variants, regulatory mutations, and novel LoF mechanisms in non-coding regions [25].

Limitations: Higher cost and data burden compared to targeted approaches; requires sophisticated bioinformatics infrastructure [29].

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)

Protocol: WES enriches for protein-coding regions (1-2% of genome) where most known LoF mutations with large effects occur [24].

- Target Capture: Use integrated workflow (e.g., Illumina Exome Panel) with biotinylated probes targeting ~60Mb exonic regions [28].

- Sequencing Parameters: Sequence to 100x mean coverage to ensure adequate depth for heterozygous variant calling [26].

- Validation: Confirm target coverage with >95% of exons covered at 20x minimum [26].

Advantages: Cost-effective for large sample sizes; focuses on most interpretable genomic regions [24].

Limitations: Misses regulatory variants; uneven coverage due to capture biases [26].

Targeted Gene Panel Sequencing

Protocol: Focused sequencing of genes relevant to specific disease areas or biological pathways [26].

- Panel Design: Custom panels (e.g., Haloplex, Ion Torrent) including known and candidate genes in disease-relevant pathways [26].

- Multiplexing: Barcode samples for high-throughput processing (96-384 samples per run) [26].

- Sequencing Depth: Sequence to very high depth (500x) to detect low-level mosaicism [26].

Advantages: Highest cost-efficiency for focused hypotheses; enables ultra-deep sequencing for sensitivity [26].

Limitations: Restricted to known biology; unable to discover novel gene-disease associations [26].

RNA Sequencing for Functional Validation of LoF

Protocol: Targeted RNA-seq validates transcriptional consequences of putative LoF mutations [30].

- Library Prep: Use ribosomal RNA depletion or poly-A selection for RNA enrichment; targeted RNA panels (e.g., Agilent Clear-seq, Roche Comprehensive Cancer panels) provide deeper coverage of genes of interest [30].

- Sequencing: Aim for 50-100 million reads per sample depending on expression dynamics [30].

- Quality Metrics: Check RNA integrity number (RIN >7), mapping rates (>80%), and gene body coverage [30].

Advantages: Confirms allelic expression imbalance, nonsense-mediated decay, and splicing defects; bridges DNA to protein functional effects [30].

Applications: Particularly valuable for classifying variants of uncertain significance and confirming functional impact of putative LoF mutations [30].

Bioinformatics Pipeline for LoF Variant Calling

Computational Workflow for LoF Identification

The bioinformatics pipeline for identifying bona fide LoF mutations requires multiple filtering steps to distinguish true functional variants from sequencing artifacts or benign rare variants.

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics Pipeline for LoF Variant Calling

Key Filtering Steps and Criteria

Table 3: Bioinformatics Filters for High-Confidence LoF Variants

| Filtering Step | Tools & Databases | Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Qscore >30, mapping quality >50, depth >20x | Removes technical artifacts and false positives |

| Variant Annotation | VEP, SnpEff | Predicted impact: HIGH (stop-gain, frameshift, canonical splice) | Focuses on variants most likely to cause complete LoF |

| Population Frequency | gnomAD, 1000 Genomes | MAF <0.1% in population databases | Filters benign common variants; retains rare pathogenic variants |

| In Silico Prediction | CADD, REVEL, SIFT | CADD >20, REVEL >0.5, SIFT <0.05 | Computational evidence of deleteriousness |

| Functional Impact | LOFTEE, ANNOVAR | Passes all LoF filters, not in last 5% of transcript | Removes false positive LoF calls due to annotation errors |

| Conservation | PhyloP, GERP++ | PhyloP >1.5, GERP++ >2 | Evolutionary constraint indicates functional importance |

The integration of AI and machine learning tools, such as Google's DeepVariant, has significantly improved the accuracy of variant calling, particularly for challenging genomic regions [27]. Cloud-based platforms (AWS, Google Cloud Genomics) provide the scalable computational resources needed for these intensive analyses [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of NGS-based LoF discovery requires integration of specialized reagents, platforms, and computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NGS-based LoF Discovery

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Function in Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera Flex | Fragment DNA and add sequencing adapters | Compatibility with automation, fragment size distribution |

| Target Enrichment | IDT xGen, Twist Human Core Exome | Capture specific genomic regions (exomes, panels) | Coverage uniformity, off-target rates |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X, PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore | Generate raw sequence data | Throughput, read length, error profiles, cost per sample |

| Automation Systems | Hamilton STAR, Agilent Bravo | Standardize liquid handling for library prep | Walkaway time, cross-contamination prevention |

| QC Instruments | Agilent TapeStation, Qubit Fluorometer | Assess library quality and quantity | Sensitivity, required sample volume, throughput |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK, VEP, DeepVariant, LOFTEE | Process data and identify high-quality LoF variants | Accuracy, computational requirements, scalability |

| Cloud Computing | AWS Genomics, Google Cloud Genomics | Scalable data analysis and storage | Data transfer costs, HIPAA/GDPR compliance [27] |

| Data Visualization | IGV, R/Bioconductor | Visualize variants and explore results | User interface, customization options |

Integration with Chemogenomic Target Discovery

Conceptual Framework: From Genetic Finding to Therapeutic Hypothesis

The integration of LoF mutation data into chemogenomic research creates a powerful framework for identifying and prioritizing novel therapeutic targets. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual pipeline:

Diagram 3: From Genetic Finding to Therapeutic Hypothesis

Enhancing Drug Discovery Success Rates

The integration of NGS-derived LoF evidence into target selection significantly de-risks drug discovery, which traditionally suffers from high failure rates (only 19% clinical success rate from phase 1 to approval) [14]. This approach provides multiple advantages:

- Human Validation: Targets with human genetic evidence, particularly LoF mutations with protective effects, have approximately twice the success rate in clinical development compared to those without [2].

- Safety Prediction: Natural LoF variants reveal potential on-target toxicities before drug development, as phenotypes associated with germline LoF mutations often predict pharmacological inhibition side effects [2].

- Patient Stratification: LoF mutations can identify patient subpopulations most likely to respond to targeted therapies, enabling precision medicine approaches in clinical trials [2] [30].

- Drug Repurposing: LoF mutations in genes encoding drug targets can reveal new therapeutic indications for existing compounds [3].

The integration of NGS-based LoF mutation discovery with chemogenomic target research represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery. This approach leverages human genetics as a randomized natural experiment, providing unprecedented evidence for target selection and validation. As NGS technologies continue to advance—with innovations in long-read sequencing, single-cell genomics, and AI-driven analytics—the resolution and scope of LoF discovery will further accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets [27].

The declining costs of sequencing (with whole genome sequencing now approaching $200 per genome) and growing population genomic resources are making this approach increasingly accessible [29] [28]. Future developments in functional genomics, including CRISPR screening and multi-omics integration, will further enhance our ability to interpret LoF mutations and translate genetic findings into transformative therapies [27]. Through the systematic application of these methodologies, the drug discovery pipeline can become more efficient, evidence-based, and successful in delivering novel medicines to patients.

Practical NGS Applications: From Targeted Panels to Single-Cell Sequencing in Functional Genomics

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomic target discovery by providing powerful tools to elucidate the genetic underpinnings of disease and identify novel therapeutic targets [1] [27]. The choice of sequencing strategy—whole-genome, exome, or targeted—is pivotal, as it directly impacts the breadth of discovery, the depth of analysis, and the efficiency of the research pipeline. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these core NGS approaches to inform their strategic application in drug discovery research.

Core Sequencing Methodologies Compared

The three primary NGS approaches offer distinct trade-offs between comprehensiveness, cost, data management, and analytical depth, making them suited for different stages of the target discovery workflow.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Whole-Genome, Exome, and Targeted Sequencing

| Feature | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing (Panels) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Target | Entire genome (coding and non-coding regions) [31] | Protein-coding exons (~1-2% of genome) [32] [31] | Specific genes or regions of interest (e.g., disease-associated genes) [31] |

| Variant Detection | Most comprehensive: SNVs, indels, structural variants, copy number variants, regulatory elements [31] [33] | Primarily SNVs and small indels in exons; limited sensitivity for structural variants [33] | Focused on known or suspected variants in the panel design [31] |

| Best For | Discovery of novel variants, de novo assembly, non-coding region analysis [31] [33] | Balancing cost and coverage for identifying causal variants in coding regions [32] [33] | Cost-effective, high-depth sequencing of specific genomic hotspots [31] |

| Data Volume | Largest (terabytes) [31] | Medium [31] | Smallest [31] |

| Approximate Cost | $$$ (Highest) [31] | $$ (Medium) [31] | $ (Lowest) [31] |

| Diagnostic Yield | Highest potential, but analysis of non-coding regions is challenging [33] | High for coding regions (~85% of known pathogenic variants are in exons) [33] | High for the specific genes targeted, but can miss variants outside the panel [33] |

Table 2: Strategic Application in Drug Discovery Workflows

| Application | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing (Panels) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Discovery-based research, uncovering new drug targets and disease mechanisms [31] [34] | Disease-specific research, clinical sequencing, diagnosing rare genetic disorders [32] [31] [33] | Clinical sequencing, IVD testing, oncology, inherited disease, liquid biopsy [31] |

| Target Identification | Excellent for novel target and biomarker discovery across the entire genome [34] | Good for identifying targets within protein-coding regions [32] | Limited to pre-defined targets; not for discovery [31] |

| Pharmacogenomics | Comprehensive profiling of variants affecting drug metabolism and response [35] | Identifies relevant variants in coding regions of pharmacogenes [35] | Panels for specific pharmacogenes (e.g., CYP450 family) to guide therapy [35] |

| Clinical Trial Stratification | Can identify complex biomarkers for patient stratification [34] | Useful for stratifying based on coding variants [32] | Highly efficient for stratifying patients based on a known biomarker signature [31] [34] |

NGS in Chemogenomic Target Discovery

Next-generation sequencing improves chemogenomic target discovery research by enabling a systematic, genome-wide, and data-driven approach. It moves beyond the traditional "one-drug, one-target" paradigm to a systems pharmacology perspective, which is critical for treating complex diseases involving multiple molecular pathways [36].

NGS technologies allow researchers to rapidly sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, providing comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, and gene expression profiles [1]. This capability is foundational for identifying and validating new therapeutic targets.

Experimental Workflow for Target Discovery

A typical NGS-based target discovery pipeline involves a multi-stage process. The following diagram outlines the key steps from sample preparation to target identification and validation.

Integrating CRISPR and AI for Enhanced Discovery

The integration of CRISPR screening with NGS has redefined therapeutic target identification by enabling high-throughput functional genomics [37]. Researchers can use extensive single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries to systematically knock out genes across the genome and use NGS to read the outcomes. This identifies genes essential for cell survival or drug response, directly implicating them as potential therapeutic targets [37]. When combined with organoid models, this approach provides a more physiologically relevant context for target identification [37].

Furthermore, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning have become indispensable for analyzing the massive, complex datasets generated by NGS [27] [36]. Tools like Google's DeepVariant use deep learning to identify genetic variants with greater accuracy than traditional methods [27]. AI models can analyze polygenic risk scores, predict drug-target interactions, and help prioritize the most promising candidate targets from NGS data, thereby streamlining the drug development pipeline [27] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of an NGS-based target discovery project relies on a suite of essential reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NGS

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep | Fragmentation Enzymes/Shearers | Randomly breaks DNA into appropriately sized fragments for sequencing [31]. |

| Sequencing Adapters & Barcodes | Ligated to fragments for platform binding and multiplexing multiple samples [31]. | |

| Enrichment | Hybridization Capture Probes | Biotinylated oligonucleotides that enrich for exonic or other genomic regions of interest in solution-based WES [31]. |

| PCR Primer Panels | Multiplexed primers for amplicon-based enrichment in targeted sequencing [31]. | |

| Sequencing | NGS Flow Cells | Solid surfaces where clonal amplification and sequencing-by-synthesis occur (e.g., Illumina) [1]. |

| Polymerases & dNTPs | Enzymes and nucleotides essential for the DNA amplification and sequencing reaction [1]. | |

| Data Analysis | Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software for sequence alignment, variant calling, and annotation (e.g., GATK, GRAF). |

| Reference Genomes | Standardized human genome sequences (e.g., GRCh38) used as a baseline for aligning sequenced reads. | |

| Validation | CRISPR-Cas9/sgRNA Libraries | Tools for high-throughput functional validation of candidate target genes identified by NGS [37]. |

The field of NGS is rapidly evolving. Long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are improving the ability to resolve complex regions of the genome that were previously difficult to sequence, such as those with repetitive elements or complex structural variations [38]. Meanwhile, the continued integration of multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics) with genomic data provides a more comprehensive view of biological systems, further enhancing target discovery and validation [27].

As the cost of whole-genome sequencing continues to fall (approaching ~$500), its use in large-scale population biobanks is becoming more feasible, providing an unprecedented resource for discovering new genetic associations with disease [38]. Cloud computing platforms are also proving crucial for managing and analyzing the immense datasets generated, offering scalable and collaborative solutions for researchers [27].

The choice of sequencing strategy is not one-size-fits-all and should be driven by the specific research question and context.

- Use targeted panels for efficient, cost-effective screening of known genes in clinical or validated research settings.

- Employ WES as a balanced first-tier test for rare disease diagnosis and projects where the primary interest lies in protein-coding regions.

- Leverage WGS for maximum comprehensiveness in discovery-phase research, aiming to identify novel targets and biomarkers across the entire genome, including non-coding regions.

By understanding the strengths and applications of each method, researchers and drug developers can strategically select the optimal NGS approach to accelerate chemogenomic target discovery and advance the development of precision medicines.

Targeted NGS Panels for Efficient Profiling of Actionable Mutations in Oncology

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed oncology research and clinical practice, enabling a paradigm shift from morphological to molecular diagnosis. In chemogenomic target discovery—the process of linking genetic information to drug response—targeted NGS panels have emerged as a critical tool for efficient identification of actionable mutations. Unlike broader sequencing approaches, these panels focus on a predefined set of genes with known clinical or research relevance to cancer, providing the depth, speed, and cost-effectiveness required for scalable drug discovery pipelines [39] [40]. By concentrating on clinically relevant mutation profiles, targeted panels bridge the gap between massive genomic datasets and practical, actionable insights, thereby accelerating the development of targeted therapies and personalized treatment strategies [41].

This technical guide explores the foundational principles, performance characteristics, and practical implementation of targeted NGS panels within the context of chemogenomic research. We detail optimized experimental protocols, data analysis workflows, and the integral role these panels play in linking genetic alterations to therapeutic susceptibility, ultimately providing a framework for their application in precision oncology.

Technical Foundations of Targeted NGS Panels

Core Design Principles and Advantages

Targeted NGS panels are designed to selectively sequence a defined set of genes or genomic regions associated with cancer. This focused approach presents several distinct advantages over whole-genome (WGS) or whole-exome sequencing (WES) in a chemogenomic context [40]:

- Predefined Focus: Panels are meticulously designed to target genes implicated in specific pathways, mutations, or cancer types, ensuring relevance to therapeutic decision-making.

- High Precision and Sensitivity: The method is fine-tuned for detecting minute genetic changes, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs), even at low allele frequencies.

- Cost-Efficiency and Faster Turnaround: By limiting sequencing to specific genomic regions, costs are drastically reduced, and results can be obtained within days, which is critical for time-sensitive research and clinical decisions [41] [40].

- Reduced Data Noise and Simplified Analysis: Targeted panels generate a concise, manageable dataset focused on regions of interest, simplifying bioinformatic analysis and interpretation.

Key Genes and Pathways Interrogated