Multiplexing in Chemogenomic NGS Screens: Strategies for High-Throughput Discovery and Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing multiplexing strategies in chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) screens.

Multiplexing in Chemogenomic NGS Screens: Strategies for High-Throughput Discovery and Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing multiplexing strategies in chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) screens. It covers foundational principles of sample multiplexing and its critical role in enhancing throughput and reducing costs in large-scale functional genomics studies. The content explores practical methodological approaches, including barcoding strategies and library preparation protocols, alongside advanced techniques like single-cell multiplexing and CRISPR-based screens. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting common experimental challenges and optimizing workflows for accuracy. Furthermore, the article delivers a comparative analysis of multiplexing performance against other sequencing methods, supported by validation frameworks to ensure data reliability. This resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively design, execute, and interpret multiplexed chemogenomic screens, thereby accelerating drug discovery and functional genomics research.

Unlocking Scale and Efficiency: The Core Principles of Sample Multiplexing in NGS

Sample multiplexing, also referred to as multiplex sequencing, is a foundational technique in next-generation sequencing (NGS) that enables the simultaneous processing of numerous DNA libraries during a single sequencing run [1]. This methodology is particularly vital in high-throughput applications such as chemogenomic CRISPR screens, where researchers need to evaluate thousands of genetic perturbations against various chemical compounds. By allowing large numbers of libraries to be pooled and sequenced together, multiplexing exponentially increases the number of samples analyzed without a corresponding exponential increase in cost or time [1]. The core mechanism that makes this possible is the use of barcodes or index adapters—short, unique nucleotide sequences added to each DNA fragment during library preparation [1] [2]. After sequencing, these barcodes act as molecular passports, allowing bioinformatic tools to identify the sample origin of each read and sort the complex dataset into its constituent samples before final analysis.

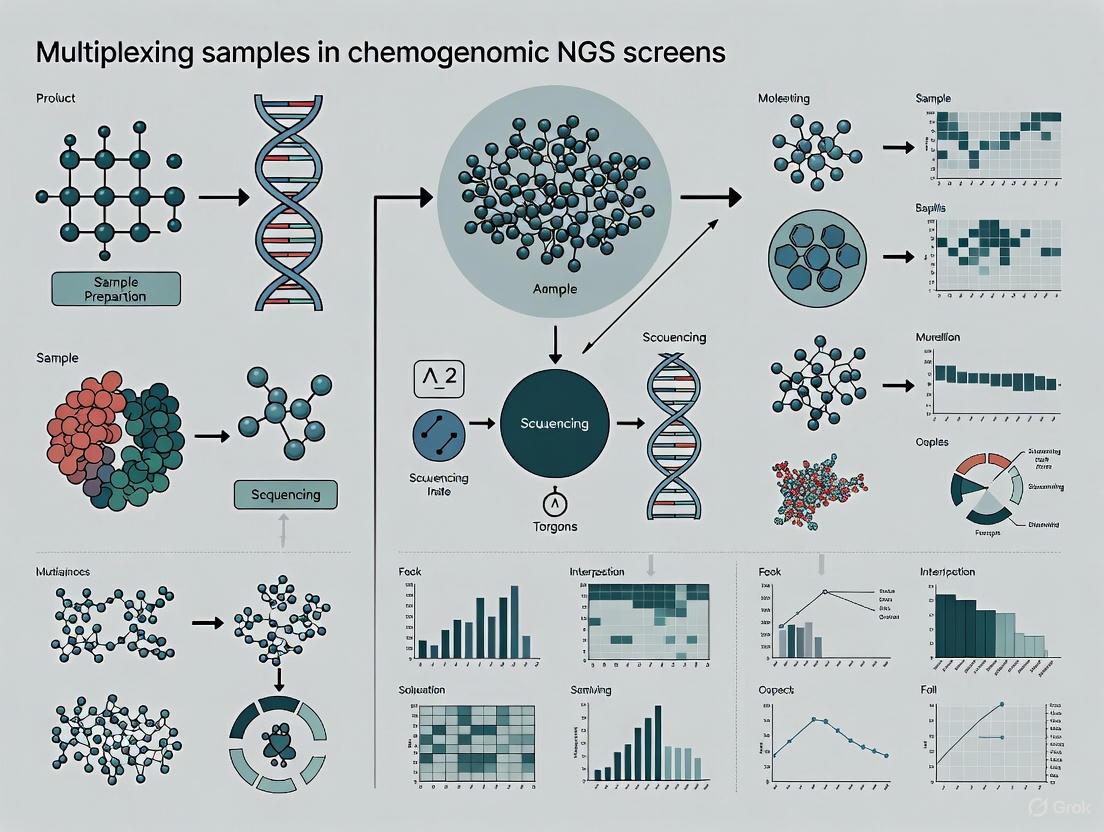

The integration of sample multiplexing is transformative for research scalability. For functional genomic screens, including those utilizing pooled shRNA or CRISPR libraries, sequencing the resulting mixed-oligo pools is a key challenge [3]. Multiplexing not only makes large-scale projects feasible but also optimizes resource utilization. The ability to pool samples means that sequencers can operate at maximum capacity, significantly reducing per-sample costs and reagent usage while dramatically increasing experimental throughput [1]. This efficiency is crucial in drug development, where screening campaigns may involve thousands of gene-compound interactions. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a multiplexed NGS experiment, from sample preparation to data demultiplexing.

Core Concepts: Barcodes, Indexes, and Adapters

In multiplexed NGS, the terms barcode and index are often used interchangeably to refer to the short, known DNA sequences (typically 6-12 nucleotides) that are attached to each fragment in a library, uniquely marking its sample of origin [4]. These sequences are embedded within the adapters—longer, universal oligonucleotides that are covalently attached to the ends of the DNA fragments during library preparation [2]. The adapters serve multiple critical functions: they contain the primer-binding sites for the sequencing reaction and, crucially, the flow cell attachment sequences that allow the library fragments to bind to the sequencing platform [2]. The barcodes are strategically positioned within these adapter structures.

There are two primary indexing strategies, which differ in the location of the barcode sequence within the adapter, as shown in the diagram below.

Inline Indexing (Sample-Barcoding): With this strategy, the index sequence is located between the sequencing adapter and the actual genomic insert [4]. A key consequence of this design is that the barcode must be read out as part of the primary sequencing read (Read 1 or Read 2), which effectively reduces the available read length for the genomic insert itself [4]. The major advantage of inline indexing is that it permits early pooling of samples. Since the barcode is added in the initial reverse transcription or amplification step, hundreds of samples can be combined and processed simultaneously through subsequent workflow steps, leading to significant savings in consumables and hands-on time [4]. This makes inline indexing ideal for ultra-high-throughput applications, such as massive single-cell RNA sequencing or high-throughput drug screening.

Multiplex Indexing: In this more common strategy, the index sequences are located within the dedicated adapter regions, not the insert [4]. This requires designated Index Reads during the sequencing process, which are separate from the reads that sequence the genomic insert. Because the index is read independently, it has no impact on the insert read length [4]. Multiplex indexing can be further divided into single and dual indexing. Single indexing uses only one index (e.g., the i7 index), while dual indexing uses two separate indexes (the i7 and the i5 index) [1] [4]. Dual indexing is now considered best practice for most applications, as it provides a powerful mechanism for error correction and drastically reduces the rate of index hopping—a phenomenon where index sequences are incorrectly reassigned between molecules [1] [4].

Indexing Strategies for Optimal Experimental Design

Choosing the correct indexing strategy is a critical step in experimental design that directly impacts data quality, multiplexing capacity, and cost. The following table compares the primary indexing methods used in NGS.

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Indexing Strategies

| Strategy | Index Location | Read Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inline Indexing [4] | Within genomic insert | Part of primary sequencing read (Read 1/Read 2) | Enables early pooling; maximizes throughput; reduces hands-on time and cost for 1000s of samples | Reduces available insert read length; less error correction capability | Ultra-high-throughput screens, single-cell RNA-seq, QuantSeq-Pool |

| Single Indexing [4] | Within adapter (i7 only) | Dedicated Index Read | Shorter sequencing time; simpler design | Higher risk of index misassignment due to errors; no built-in error correction | Low-plexity studies, older sequencing platforms |

| Dual Indexing (Combinatorial) [1] [4] | Within adapter (i7 and i5) | Two Dedicated Index Reads | High multiplexing capacity; reduced index hopping vs. single indexing | Individual barcodes are re-used, limiting error correction | Most standard applications, general RNA-seq, exome sequencing |

| Unique Dual Indexing (UDI) [1] [4] | Within adapter (unique i7 and i5) | Two Dedicated Index Reads | Highest accuracy; enables index error correction; minimizes index hopping and misassignment | Requires more complex primer design and inventory | Chemogenomic screens, rare variant detection, sensitive applications |

For sensitive applications like chemogenomic CRISPR screens, Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) are strongly recommended [4]. In a UDI system, each individual i5 and i7 index is used only once in the entire experiment. This creates a unique pair for each sample, which serves as two independent identifiers. The primary advantage is enhanced error correction: if a sequencing error occurs in one index of the pair, the second, error-free index can be used as a reference to pinpoint the correct sample identity and salvage the read [4]. This process, known as index error correction, can rescue approximately 10% of reads that would otherwise be discarded, maximizing data yield and ensuring the integrity of sample identity—a non-negotiable requirement in a quantitative screen where accurately tracking sgRNA abundance is paramount [4].

Practical Protocol for a Multiplexed Chemogenomic CRISPR Screen

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for preparing sequencing libraries from a pooled chemogenomic CRISPR screen, incorporating best practices for multiplexing. This protocol is adapted from established methodologies for sequencing sgRNA libraries from genomic DNA [5] [3].

Step-by-Step Workflow

Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction:

- Input Material: Harvest cells from the completed CRISPR screen. The number of cells to collect is critical and must be calculated based on the desired library representation (see Table 2) [5].

- Procedure: Extract gDNA using a commercial kit (e.g., PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit). CRITICAL: Do not process more than 5 million cells per spin column to avoid clogging. For larger cell numbers, use multiple columns and pool the eluted gDNA [5].

- Quality Control: Quantify gDNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA BR Assay). Assess purity via spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop); 260/280 ratios should be 1.8-2.0 [5] [6]. Aim for a high concentration (>190 ng/µL) to minimize volume in subsequent PCR.

PCR Amplification and Indexing:

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify the sgRNA integrated in the host genome. The forward primer should bind upstream of the guide spacer sequence and introduce the P5 Illumina adapter, stagger sequences (to increase nucleotide diversity), and the i7 index [5]. The reverse primer should bind downstream and introduce the P7 adapter and the i5 index [5]. For the highest data fidelity, use Unique Dual Index (UDI) primers.

- PCR Setup: Set up reactions in a decontaminated PCR workstation to avoid cross-contamination. UV-irradiate all tubes and tips before use [5].

- Reaction Conditions: Use a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Herculase). The number of parallel PCR reactions is determined by the total gDNA input required (see Table 2). To minimize heteroduplex formation (a major source of sequencing errors), use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for sufficient amplification and use magnetic beads for post-PCR clean-up instead of columns [3].

Library Purification and Quality Control:

- Purification: Pool all PCR reactions and purify using a magnetic bead-based clean-up system (e.g., GeneJET PCR Purification Kit). Beads effectively remove primers, enzymes, and small fragments while selecting for the desired library size [5] [3].

- Quality Control: Assess the final library concentration using a high-sensitivity fluorometric assay (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Validate the library size distribution using a bioanalyzer or agarose gel electrophoresis.

Pooling and Sequencing:

- Normalization and Pooling: Quantify all indexed libraries by qPCR or a high-sensitivity fluorometer. Normalize each library to an equimolar concentration and pool them together to create the final sequencing pool.

- Sequencing: Dilute the pooled library to the optimal concentration for clustering on your specific Illumina sequencing platform. A paired-end run is standard, with read lengths sufficient to cover the entire sgRNA sequence.

Table 2: Calculation of Input Requirements for CRISPR Library Representation (based on the Saturn V library example) [5]

| Saturn V Pool | Number of Guides | Library Representation at 300X | Minimum No. Cells for gDNA Extraction | Total Input gDNA Required (μg) | Parallel PCR Reactions (4 μg gDNA/reaction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool 1 | 3,427 | 530X | 2,300,000 | 12 | 3 |

| Pool 2 | 3,208 | 567X | 2,300,000 | 12 | 3 |

| Pool 3 | 3,184 | 571X | 2,300,000 | 12 | 3 |

| Pool 4 | 1,999 | 606X | 1,500,000 | 8 | 2 |

| Pool 5 | 2,168 | 559X | 1,500,000 | 8 | 2 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplexed CRISPR Screen NGS

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| gDNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from screened cells. | PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) [5], QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (QIAGEN) [3] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of the sgRNA region from gDNA with low error rate. | Herculase (Agilent Technologies) [5], Platinum Pfx (Invitrogen) [3] |

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Primers | Provides unique i5/i7 index pairs for each sample to enable sample multiplexing with minimal index hopping. | xGen NGS Adapters & Indexing Primers (IDT) [2], NEXTFLEX UDI Barcodes (Revvity) [7] |

| PCR Purification Kit | Post-amplification clean-up to remove enzymes, salts, and short fragments. Magnetic beads help reduce heteroduplexes. | GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific) [5] [3] |

| DNA Quantification Kits | Fluorometric assays for precise quantification of gDNA (Broad Range) and final libraries (High Sensitivity). | Qubit dsDNA BR/HS Assay Kits (Invitrogen) [5] |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Even with a robust protocol, challenges can arise. Below are common issues and their solutions:

Challenge: Index Hopping. This occurs when index sequences are incorrectly assigned to reads, leading to sample misidentification. It is more prevalent on pattern flow cells (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) [1] [4].

- Solution: Implement Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs). UDIs provide two unique identifiers per sample, allowing bioinformatic filters to detect and discard reads with non-matching index pairs, thus preventing misassignment [4].

Challenge: Heteroduplex Formation. During the final PCR amplification of a mixed library, incomplete extension can create heteroduplex molecules that lead to polyclonal clusters and failed sequencing reads [3].

- Solution: Minimize PCR cycles and use magnetic bead-based clean-up instead of spin columns, as beads are more effective at removing these heteroduplex structures [3].

Challenge: Mixing Indexes of Different Lengths. Combining libraries from different kits or vendors may result in a pool with varying index lengths (e.g., 8-nt and 10-nt indexes) [7].

- Solution: This is feasible. In the sample sheet, set the index length to the longest one in the pool (e.g., 10-nt). For shorter indexes, "pad" the sequence by adding bases (e.g., 'AT') to the end to match the required length. To maintain base diversity during the index read, ensure that over 50% of the pool consists of libraries with the longest index [7].

Sample multiplexing via barcodes and index adapters is an indispensable technique that underpins the scale and efficiency of modern NGS, most notably in complex, high-value applications like chemogenomic CRISPR screening. A deep understanding of the different indexing strategies—from inline to the highly recommended Unique Dual Indexing—empowers researchers to design robust, cost-effective, and high-quality studies. By adhering to the detailed protocols outlined herein, including careful calculation of library representation, meticulous PCR setup, and the use of UDIs, scientists can confidently execute multiplexed screens. This approach ensures the generation of reliable, high-integrity data that is crucial for identifying novel genetic interactions and accelerating the journey toward new therapeutic discoveries.

In the field of chemogenomics, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for unraveling the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. Chemogenomic screens, which utilize pooled shRNA or CRISPR libraries, enable the systematic interrogation of gene function and drug-target relationships on a genome-wide scale [3]. A central challenge in these studies is managing the immense scale of data generation in a cost- and time-efficient manner. Sample multiplexing, also known as multiplex sequencing, addresses this challenge by allowing large numbers of libraries to be sequenced simultaneously during a single NGS run [1]. This approach transforms the economics of large-scale genetic screens by exponentially increasing the number of samples analyzed without proportionally increasing costs or experimental time [1]. The core principle involves labeling individual DNA fragments from different samples with unique DNA barcodes (indexes) during library preparation, which enables computational separation of the data after sequencing [1]. For chemogenomic research, where screening entire libraries of compounds against comprehensive genetic backgrounds is essential, multiplexing provides the throughput necessary to achieve statistical power and biological relevance.

Economic and Operational Advantages

The implementation of multiplexing strategies confers significant economic and operational benefits, making large-scale chemogenomic projects feasible for individual laboratories.

Table 1: Economic Advantages of Multiplexed NGS in Chemogenomic Screens

| Factor | Standard NGS | Multiplexed NGS | Impact on Chemogenomic Screens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | High | Dramatically reduced [1] | Enables screening of more compounds/conditions within same budget |

| Sequencing Time | Linear increase with sample number | Minimal increase with sample number [1] | Accelerates target discovery and validation cycles |

| Reagent Consumption | Proportional to sample number | Significantly reduced [1] | Lowers per-datapoint cost in high-throughput compound profiling |

| Labor & Hands-on Time | High for multiple library preps | Consolidated into fewer, larger runs [1] | Increases research efficiency in functional genomics labs |

| Data Generation Rate | Limited by sequential processing | High-throughput; 100s of samples in parallel [1] | Facilitates robust, statistically powerful screens |

The economic imperative for multiplexing is clear. By pooling samples, researchers optimize instrument use, reduce reagent consumption, and decrease the hands-on time required per sample [1]. This is particularly critical in chemogenomic screens, where researchers often need to test multiple compound concentrations, time points, and genetic backgrounds against entire shRNA or CRISPR libraries [3]. The alternative—running samples individually—is prohibitively expensive and slow. The global NGS market's rapid growth, driven by factors like increased adoption in clinical diagnostics and drug discovery, underscores the technology's central role in modern bioscience [8]. Multiplexing ensures that chemogenomic studies can remain at the cutting edge without being constrained by resource limitations.

Key Multiplexing Methodologies and Protocols

Core Principles: Barcoding and Indexing Strategies

At the heart of sample multiplexing is the use of unique DNA barcodes, or indexes. These short, known DNA sequences are ligated to the fragments of each sample library during preparation [1]. When samples are pooled and sequenced, the sequencer reads both the genomic DNA and the barcode. Sophisticated bioinformatics software then uses these barcode sequences to demultiplex the data, sorting the sequenced reads back into their respective sample-specific files for downstream analysis [9] [10]. The choice of indexing strategy is critical for minimizing errors and maximizing multiplexing capacity.

- Unique Dual Indexes (UDI): This is the recommended strategy for complex chemogenomic screens. UDI employs two unique barcodes on each fragment—one on each end. This provides an error-correction mechanism, as an index hop (where a barcode is incorrectly assigned) is highly unlikely to occur for both indexes simultaneously. This dramatically reduces misassignment and cross-talk between samples, ensuring the integrity of sample identity in pooled screens [1].

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): For applications requiring ultra-high accuracy in quantifying allele frequencies or transcript counts, UMIs are incorporated. UMIs are random molecular barcodes added to each molecule before amplification. This allows bioinformatics tools to distinguish between biologically unique molecules and PCR duplicates, thereby reducing false-positive variant calls and increasing the sensitivity of detection [1]. This is vital in chemogenomics for accurately determining guide RNA abundances in CRISPR screens or quantifying dropout of shRNAs in response to compound treatment.

Detailed Protocol: Maximizing Throughput in Pooled shRNA/CRISPR Screens

Pooled chemogenomic screens are highly susceptible to sequencing failures due to the formation of secondary structures (hairpins) and heteroduplexes in mixed-oligo PCR reactions [3]. The following optimized protocol mitigates these issues to maximize usable data from a single run.

A. Library Amplification from Genomic DNA

- Isolate Genomic DNA: From cells transduced with the pooled shRNA or CRISPR library, using a kit such as the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit [3].

- Amplify the Library: Perform PCR amplification using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Platinum Pfx). Critical parameters include:

- Template: Use ~20 µg of genomic DNA to ensure sufficient representation of each shRNA/sgRNA in the library [3].

- Primers: Design primers compatible with your sequencer and which flank the shRNA/sgRNA sequence.

- PCR Cycles: Minimize the number of cycles (e.g., 30 cycles) to reduce the formation of heteroduplexes, which are a major cause of low-quality, polyclonal reads [3].

- Purify the Product: Pool PCR reactions and purify using a magnetic bead-based purification system (e.g., GeneJET PCR Purification Kit). Beads are preferred over gel extraction at this stage for speed and to minimize heteroduplex formation [3].

B. Overcoming Hairpin Structures (Half-shRNA Method)

This step is crucial for shRNA libraries, which contain palindromic sequences that form hairpins, leading to incomplete and failed sequencing reads [3].

- Restriction Digest: Digest the purified PCR product with a restriction enzyme (e.g., XhoI) that cuts specifically within the loop region of the shRNA hairpin. Perform the digestion immediately after PCR purification to avoid cruciform formation [3].

- Ligate Adapter: Purify the digested product to remove the small, cut loop fragment. Ligate a custom adapter oligonucleotide to the end of the now-linearized shRNA fragment. This adapter provides the sequence necessary for binding to the sequencing flow cell [3].

- Final Amplification: Perform a second, limited-cycle PCR with primers that bind the adapter and the original library-specific sequence to generate the final sequencing library.

C. Library Quantification and Pooling

- Quantify each barcoded library accurately using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit).

- Pool Equimolar amounts of each uniquely barcoded library into a single tube. Use a pooling calculator to normalize contributions and ensure even sequencing coverage across all samples [1].

D. Sequencing

Sequence the pooled library on an appropriate Illumina sequencer (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq, or NovaSeq), following the manufacturer's instructions for loading and data generation [1].

Diagram: Multiplexing Workflow for Pooled Screens. This workflow illustrates the key steps, from library preparation to computational demultiplexing, highlighting stages critical for overcoming technical challenges like hairpins.

Data Analysis Workflow for Multiplexed Screens

The data analysis pipeline for a multiplexed chemogenomic screen is a multi-stage process that transforms raw sequencer output into biologically interpretable results.

Primary Analysis occurs on the sequencer and involves the conversion of raw signal data (e.g., fluorescence, pH change) into nucleotide base calls. The key output of this stage is the FASTQ file, which contains the sequence of each read and its corresponding per-base quality score (Phred score) [9] [10]. A critical step in primary analysis is demultiplexing, where the sequencer's software uses the index reads to sort all sequences into separate FASTQ files, one for each sample in the pool [9].

Secondary Analysis begins with quality control and alignment.

- Read Cleanup: Tools like Trimmomatic or FastQC are used to trim adapter sequences and remove low-quality reads or portions of reads (typically with a Phred score cutoff of <30) [10]. This step generates a "cleaned" FASTQ file.

- Alignment (Mapping): The cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., hg38 for human) using specialized aligners like BWA or Bowtie. The output is a BAM (Binary Alignment Map) file, a compressed, efficient format storing how each read maps to the genome [9] [10] [11].

- Variant Calling: For chemogenomic screens, the crucial step is not variant calling but molecular barcode counting. Custom scripts or tools are used to count the number of reads corresponding to each unique shRNA or sgRNA sequence from the BAM file, generating a count table [10] [3].

Tertiary Analysis involves the biological interpretation of the data. The count table for each sample (condition, compound treatment) is analyzed to identify shRNAs/sgRNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted compared to a control (e.g., DMSO-treated cells). This statistical analysis, often using specialized software, reveals genes essential for survival under specific chemical treatments, thereby identifying potential drug targets or resistance mechanisms [10].

Diagram: NGS Data Analysis Pipeline. The three-stage workflow from raw data to biological interpretation, showing key file types and processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplexed Chemogenomic Screens

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Provides enzymes and buffers for end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. | Select kits designed for complex genomic DNA inputs and that support dual indexing [3]. |

| Unique Dual Indexed (UDI) Adapters | Contains the unique barcode sequences for multiplexing. | UDIs are essential for minimizing index hopping in pooled screens, ensuring sample identity integrity [1]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the library from genomic DNA with low error rates. | Critical for accurate representation of the shRNA/sgRNA pool; minimizes PCR-introduced errors [3]. |

| Magnetic Bead-based Purification Kits | For size selection and cleanup of DNA after enzymatic reactions. | Preferred over column-based or gel extraction for higher yield and to reduce heteroduplex formation [3]. |

| Restriction Enzyme (e.g., XhoI) | Digests hairpin structures in shRNA libraries. | Key for the "half-shRNA" method to prevent sequencing failures due to secondary structures [3]. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Assay | Accurately measures DNA concentration. | Essential for normalizing library concentrations before pooling to ensure even sequencing coverage [3]. |

| Pooled shRNA/CRISPR Library | The core reagent containing the collection of genetic perturbagens. | Libraries targeting specific gene families (e.g., kinome) are ideal for focused chemogenomic screens [3]. |

The strategic implementation of multiplexing is a cornerstone of modern, high-throughput chemogenomics. By enabling the processing of hundreds of samples in a single NGS run, it provides an undeniable economic and throughput advantage, making large-scale, statistically robust screens routine. Adhering to optimized protocols that address technical challenges like heteroduplex formation and hairpin structures, combined with the use of robust bioinformatics pipelines, ensures the generation of high-quality, reliable data. As NGS technology continues to evolve, becoming faster and more cost-effective, its synergy with advanced multiplexing strategies will further empower researchers to deconvolute the complex interplay between genes and small molecules, accelerating the pace of drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Multiplexing as a Pillar of Modern Chemogenomics and Functional Genomics Screens

Multiplexing has emerged as a foundational methodology that has fundamentally transformed the scale and efficiency of chemogenomic and functional genomic research. This approach, which enables the simultaneous processing and analysis of numerous samples or perturbations within a single experiment, provides the technical framework for high-throughput screening campaigns essential for modern drug discovery and functional genomics. The core principle of multiplexing involves strategically "barcoding" individual samples or perturbations with unique identifiers, allowing them to be pooled and processed collectively while maintaining the ability to deconvolute results back to their origin through computational demultiplexing [1] [12]. This paradigm has become indispensable for addressing the complexity of biological systems, where understanding the relationships between genetic variants, chemical perturbations, and phenotypic outcomes requires testing thousands to millions of experimental conditions.

The adoption of multiplexing strategies across genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and chemogenomics has accelerated the transition from reductionist, single-target approaches to systems-level investigations. In chemogenomics, where small molecule libraries are screened against biological systems to identify bioactive compounds and their mechanisms of action, multiplexing enables the efficient profiling of extensive compound libraries [13]. Similarly, in functional genomics, which seeks to understand gene function and regulation, multiplexed assays make it feasible to systematically interrogate the consequences of thousands of genetic perturbations in parallel [14] [15]. The integration of these fields through multiplexed approaches provides unprecedented opportunities to link chemical and genetic perturbations to molecular and cellular phenotypes, offering comprehensive insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic strategies.

Fundamental Principles and Advantages of Multiplexing

Core Concepts and Methodological Framework

At its essence, multiplexing relies on the incorporation of unique molecular tags, or barcodes, that serve as sample identifiers throughout experimental workflows. These barcodes can be introduced at various stages: during library preparation for next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1], through metabolic or chemical labeling in proteomic studies [16], via lentiviral vectors for genetic perturbations [12], or through antibody-based tagging methods in single-cell studies [12]. The strategic application of these identifiers enables researchers to combine multiple experimental conditions, significantly reducing reagent costs, instrument time, and technical variability while dramatically increasing experimental throughput.

Two primary indexing strategies dominate multiplexed NGS approaches: single indexing and dual indexing. Single indexing employs one barcode sequence per sample, while dual indexing uses two separate barcode sequences, providing a much larger combinatorial space for sample identification [1]. Dual indexing is particularly valuable in large-scale screens as it exponentially increases the number of samples that can be uniquely tagged and pooled. For example, a dual indexing system with 24 unique i5 indexes and 24 unique i7 indexes can theoretically multiplex 576 samples in a single sequencing run. This strategy also helps mitigate index hopping—a phenomenon where barcode sequences are incorrectly assigned during sequencing—which can compromise data integrity in highly multiplexed experiments [1].

Key Advantages in Screening Applications

The implementation of multiplexing strategies confers several critical advantages that make large-scale chemogenomic and functional genomic screens technically and economically feasible:

Cost Efficiency: Pooling samples exponentially increases the number of samples analyzed in a single sequencing run or mass spectrometry injection without proportionally increasing costs. This efficiency makes large-scale screens accessible even with limited resources [1] [16].

Reduced Technical Variability: Processing all samples simultaneously under identical conditions minimizes batch effects and technical noise, enhancing the statistical power to detect true biological signals [12].

Increased Throughput: Multiplexing enables the processing of hundreds to thousands of samples in timeframes previously required for just a handful of samples, dramatically accelerating screening timelines [14] [15].

Internal Controls: Multiplexed designs naturally incorporate internal controls and reference standards within the same experiment, improving normalization and quantitative accuracy [16].

Resource Conservation: By reducing the consumption of expensive reagents, antibodies, and sequencing capacity, multiplexing extends research budgets while maximizing data output [1] [17].

Technological Approaches for Multiplexed Screens

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs)

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays represent a powerful multiplexing approach for functionally characterizing noncoding genetic variants. MPRAs utilize synthetic oligonucleotide libraries containing thousands to millions of putative regulatory elements, each coupled to a unique barcode sequence. These libraries are introduced into cells, where the transcriptional activity of each element drives the expression of its associated barcode. By quantifying barcode abundance through high-throughput sequencing, researchers can simultaneously assess the regulatory potential of thousands of sequences in a single experiment [14].

The key advantage of MPRA lies in its direct measurement of regulatory function and its ability to test sequences outside their native genomic context, eliminating confounding effects from local chromatin environment or three-dimensional genome architecture. However, this strength also represents MPRAs' primary limitation: the artificial context may not fully recapitulate endogenous regulatory dynamics. Additionally, MPRAs cannot inherently identify the target genes of regulatory elements, requiring complementary approaches to establish physiological relevance [14].

CRISPR-Based Pooled Screens

CRISPR-based technologies have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise genetic perturbations at unprecedented scale. Pooled CRISPR screens introduce complex libraries of guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting thousands of genomic loci into populations of cells, with each gRNA acting as both a perturbation agent and a unique barcode for that perturbation [14] [15]. The power of this approach lies in its flexibility—different CRISPR systems can be employed to achieve diverse perturbation modalities:

- CRISPR Knockout: Utilizes Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks, resulting in gene disruption through imperfect repair [14].

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Employs catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor domains to reversibly suppress gene expression without altering DNA sequence [14].

- CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): Uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activator domains to enhance gene expression [14].

- Base Editing: Leverages Cas9 nickase fused to deaminase enzymes to directly convert one base to another without double-strand breaks [15].

- Prime Editing: Utilizes Cas9 nickase fused to reverse transcriptase to mediate all possible base-to-base conversions, small insertions, and small deletions [15].

These diverse CRISPR tools enable researchers to tailor their screening approach to specific biological questions, from essential gene identification to nuanced studies of transcriptional regulation or specific mutational effects.

Single-Cell Multiomic Technologies

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have enabled multiplexed analysis at unprecedented resolution. Single-cell DNA-RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) simultaneously profiles up to 480 genomic DNA loci and gene expression in thousands of single cells, enabling accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated transcriptional changes [18]. This joint profiling confidently links precise genotypes to gene expression in their endogenous context, overcoming limitations of methods that use guide RNAs as proxies for variant perturbation [18].

Several sample-multiplexing strategies have been developed for single-cell sequencing to overcome challenges of inefficient sample processing, high costs, and technical batch effects:

- Natural Genetic Variation: Demultiplexing based on naturally occurring genetic variants using tools like demuxlet, scSplit, Vireo, or Souporcell [12].

- Cell Hashing: Uses oligo-tagged antibodies against ubiquitous cell-surface proteins to label cells from different samples prior to pooling [12].

- MULTI-seq: Employs lipid-modified oligonucleotides that incorporate into cell membranes to barcode live cells [12].

- Nucleus Hashing: Adapts cell hashing principles for nuclei isolation using DNA-barcoded antibodies targeting the nuclear pore complex [12].

These approaches enable "super-loading" of single cells, significantly increasing throughput while reducing multiplet rates and identifying technical artifacts [12]. The ability to pool multiple samples prior to single-cell processing also minimizes batch effects and reduces per-sample costs, making large-scale single-cell studies more feasible.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Multiplexing Technologies

| Technology | Multiplexing Capacity | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPRA | 10³-10⁶ variants/experiment | Functional characterization of noncoding variants | Direct measurement of regulatory function; High throughput | Artificial genomic context; Cannot infer endogenous target genes |

| CRISPR Screens | 10³-10⁵ gRNAs/experiment | Functional genomics; Gene discovery; Mechanism of action studies | Endogenous genomic context; Diverse perturbation modalities; Target gene identification | Relatively lower throughput; Potential for confounding off-target effects |

| Single-Cell Multiomics | 10³-10⁵ cells/experiment; 2-8 samples/pool | Cellular heterogeneity; Gene regulation studies; Tumor evolution | Single-cell resolution; Combined genotype-phenotype information | Technical complexity; Higher cost per cell; Limited molecular targets per cell |

| Isobaric Labeling (Proteomics) | 2-54 samples/experiment [16] | Quantitative proteomics; Drug mechanism studies | Reduced instrument time; Internal controls; High quantitative accuracy | Potential for reporter ion interference; Limited multiplexing compared to genetic approaches |

Experimental Protocols for Multiplexed Functional Genomics

Saturation Genome Editing for Variant Functionalization

Multiplexed Assays for Variant Effects (MAVEs) enable comprehensive functional assessment of all possible genetic variations within specific genomic regions. The following protocol outlines the steps for saturation genome editing to study variant effects:

Step 1: sgRNA Sequence Design

- Import the fully annotated gene of interest (e.g., from Ensembl) into a sequence analysis platform like Benchling.

- Select the target exon and use the guide RNA algorithm to generate 20 bp sgRNA sequences with high on-target and low off-target scores.

- Incorporate a synonymous change that disrupts the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) site to serve as a fixed marker that blocks Cas9 recutting after editing.

- Verify that PAM modification does not impact splicing using SpliceAI prediction (score > 0.2 indicates potential splicing impact).

- Order sgRNA sequences and forward/reverse primers for cloning (forward primer: 5′-CACCG + 20 bp sgRNA sequence; reverse primer: 5′-AAAC + reverse complement + C) [15].

Step 2: Oligo Donor Library Design

- Design 180 bp antisense oligos covering the Cas9 cut site with homology arms positioned such that the cut site is in the middle.

- Incorporate the fixed PAM modification into all oligos as a homologous directed repair (HDR) marker.

- Systematically change each nucleotide position across the saturation region to all three non-wild-type bases using standard mixed base nomenclature (e.g., H = A/C/T, B = G/C/T, V = A/C/G, D = A/G/T).

- Order the oligo library as 180 bp ultramers for direct use in nucleofection without cloning [15].

Step 3: Cell Culture and Nucleofection

- Culture mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) containing a single copy of the human gene of interest integrated into the mouse genome on SNLP feeder dishes in mESC maintenance media.

- Prepare cells for nucleofection by trypsinization and resuspension in nucleofection solution.

- Combine sgRNA (or Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex) with the oligo donor library and nucleofect into mESCs.

- Plate transfected cells and allow recovery for 48-72 hours before drug selection or phenotypic analysis [15].

Step 4: Genomic DNA Amplification and Sequencing

- Harvest genomic DNA from pooled edited cells after phenotypic selection or at designated timepoints.

- Amplify edited genomic regions using primers flanking the target site with Illumina adapter overhangs.

- Purify PCR products and prepare sequencing libraries using standard Illumina library preparation methods.

- Sequence on an appropriate Illumina platform to achieve sufficient coverage for variant quantification (typically >1000x coverage) [15].

Step 5: Computational Analysis

- Process sequencing data to quantify variant abundance and calculate indel rates.

- Normalize variant counts to control for amplification bias and sequencing depth.

- Determine functional impact of variants based on their enrichment or depletion under selective conditions compared to non-selective conditions.

- Classify variants as functional (enriched/depleted) or neutral (no change in abundance) [15].

Protocol for Single-Cell DNA-RNA Sequencing (SDR-seq)

SDR-seq enables simultaneous profiling of genomic DNA loci and gene expression in thousands of single cells, providing a powerful approach to link genotypes to transcriptional phenotypes:

Step 1: Cell Preparation and Fixation

- Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension using appropriate enzymatic or mechanical methods.

- Count cells and assess viability using trypan blue exclusion or similar methods.

- Fix cells using either paraformaldehyde (PFA) or glyoxal. Glyoxal is preferred for better nucleic acid preservation as it does not cross-link nucleic acids [18].

- Permeabilize fixed cells to enable access to intracellular components for subsequent molecular reactions.

Step 2: In Situ Reverse Transcription

- Perform in situ reverse transcription using custom poly(dT) primers that add a unique molecular identifier (UMI), sample barcode, and capture sequence to cDNA molecules.

- This step preserves the cellular origin of RNA molecules while adding the necessary information for downstream demultiplexing and sequencing.

Step 3: Droplet-Based Partitioning and Amplification

- Load cells containing cDNA and gDNA onto the Tapestri platform (Mission Bio) for droplet-based partitioning.

- Generate first droplets containing individual cells, then lyse cells and treat with proteinase K to release nucleic acids.

- Mix with reverse primers for each intended gDNA or RNA target and generate second droplets containing forward primers with capture sequence overhangs, PCR reagents, and barcoding beads with cell barcode oligonucleotides.

- Perform multiplexed PCR within droplets to amplify both gDNA and RNA targets, with cell barcoding achieved through complementary capture sequence overhangs [18].

Step 4: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Break emulsions and purify amplified products.

- Prepare separate sequencing libraries for gDNA and RNA using distinct overhangs on reverse primers (R2N for gDNA, R2 for RNA).

- This separation enables optimized sequencing for each data type: full-length coverage for gDNA variants and standard RNA-seq libraries for transcriptome analysis.

- Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform with appropriate read lengths to cover the targeted regions [18].

Step 5: Data Integration and Analysis

- Process sequencing data to assign reads to individual cells based on cell barcodes.

- Demultiplex samples based on genetic variants or sample barcodes introduced during in situ RT.

- Call variants from gDNA reads and quantify gene expression from RNA reads.

- Integrate data to associate specific genotypes with transcriptional changes at single-cell resolution [18].

Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplexed Screens

Successful implementation of multiplexed screening approaches requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for high-throughput applications. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for establishing multiplexed functional genomics and chemogenomics workflows:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Multiplexed Genomic Screens

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Multiplexed Screens | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barcoding Reagents | Unique Dual Indexes (Illumina) [1]; Cell Hashing Antibodies [12]; MULTI-seq Lipids [12] | Sample multiplexing; Sample origin identification | Barcode diversity; Minimal sequence similarity; Compatibility with downstream applications |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep; Nextera XT; NEBNext Ultra II [17] | NGS library construction; Adapter ligation; Library amplification | Efficiency for low-input samples; Compatibility with automation; Fragment size distribution |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 enzymes; sgRNA libraries; Base editors; Prime editors [14] [15] | Genetic perturbation; Screening libraries; Precision genome editing | Editing efficiency; Specificity; Delivery method; Off-target effects |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium; BD Rhapsody; Mission Bio Tapestri [18] [12] | Single-cell partitioning; Barcoding; Library preparation | Cell throughput; Multiplexing capacity; Multiomics capabilities; Cost per cell |

| Quantitative Proteomics Reagents | TMT & iTRAQ isobaric tags [16]; DiLeu tags [16]; SILAC amino acids [16] | Multiplexed protein quantification; Sample multiplexing in MS | Number of plex; Labeling efficiency; Cost; Reporter ion interference |

| Cell Painting Reagents | Cell Painting kit (Broad Institute); Fluorescent dyes [13] | Morphological profiling; Phenotypic screening | Image quality; Stain specificity; Compatibility with automation; Feature extraction |

Data Analysis and Computational Considerations

The computational demultiplexing and analysis of data generated from multiplexed screens present unique challenges and considerations. Effective analysis pipelines must address several key aspects:

Demultiplexing Strategies: The approach to sample demultiplexing depends on the barcoding method employed. For genetically multiplexed samples, tools like demuxlet, scSplit, Vireo, and Souporcell use natural genetic variation to assign cells to their sample of origin [12]. These tools employ different statistical approaches—including maximum likelihood models, hidden state models, and Bayesian methods—to confidently assign cells to samples based on reference or reference-free genotyping. For antibody-based hashing methods, demultiplexing involves detecting the antibody-derived tags (ADTs) associated with each cell and comparing their expression patterns to assign sample identity [12].

Multiomic Data Integration: Advanced multiplexing approaches like SDR-seq generate coupled DNA and RNA measurements from the same single cells, requiring specialized integration methods [18]. These analyses must account for technical factors such as allelic dropout (where one allele fails to amplify), cross-contamination between cells, and the sparsity inherent in single-cell data. Successful integration enables researchers to directly link genotypes (e.g., specific mutations) to transcriptional phenotypes (e.g., differential expression) within the same cells, providing powerful insights into variant function [18].

Hit Identification and Validation: In pooled screening approaches, identifying true hits requires careful statistical analysis to distinguish biologically significant signals from technical noise. Methods like MAGeCK, BAGEL, and drugZ implement specialized statistical models that account for guide-level efficiency, screen dynamics, and multiple testing correction. For chemogenomic screens integrating chemical and genetic perturbations, network-based approaches can help identify functional modules and pathways affected by compound treatment [13].

Application in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

Multiplexed approaches have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery, particularly in the emerging field of network pharmacology which considers the complex interactions between drugs and multiple biological targets [13]. Chemogenomic libraries comprising 5,000 or more small molecules representing diverse target classes enable systematic profiling of compound activities against biological systems [13]. When combined with multiplexed readouts, these libraries provide unprecedented insights into compound mechanism of action, polypharmacology, and cellular responses.

Morphological Profiling: The Cell Painting assay represents a powerful multiplexed phenotypic screening approach that uses multiplexed fluorescence imaging to capture thousands of morphological features in treated cells [13]. When applied to chemogenomic libraries, this approach generates high-dimensional phenotypic profiles that can be used to cluster compounds with similar mechanisms of action, identify novel bioactive compounds, and deconvolute the cellular targets of uncharacterized compounds. The integration of morphological profiles with chemical and target information in network pharmacology databases enables predictive modeling of compound activities [13].

Target Deconvolution: A major challenge in phenotypic drug discovery is identifying the molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic effects. Multiplexed chemogenomic approaches address this challenge by screening compound libraries against diverse genetic backgrounds or in combination with genetic perturbations. For example, profiling compound sensitivity across cell lines with different genetic backgrounds or in combination with CRISPR-based genetic perturbations can help identify synthetic lethal interactions and resistance mechanisms, providing clues about compound mechanism of action [13].

Network Pharmacology: The integration of multiplexed screening data with biological networks enables a systems-level understanding of drug action. By mapping compound-target interactions onto protein-protein interaction networks, signaling pathways, and gene regulatory networks, researchers can identify network neighborhoods and functional modules affected by compound treatment [13]. This network pharmacology perspective moves beyond the traditional "one drug, one target" paradigm to consider the systems-level effects of pharmacological intervention, potentially leading to more effective therapeutic strategies with reduced side effects.

Visualizing Multiplexed Screening Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and conceptual frameworks for multiplexed screening approaches:

Diagram 1: Conceptual workflow for sample multiplexing approaches showing the integration of multiple samples through barcoding and pooling, followed by unified processing and computational demultiplexing. Key advantages include cost efficiency, reduced technical variability, and increased throughput.

Diagram 2: Workflow for multiplexed CRISPR screening showing key steps from library design and delivery through phenotypic selection and sequencing-based readout. Different CRISPR modalities enable diverse perturbation types including gene knockout, transcriptional modulation, and precise base editing.

Multiplexing technologies have fundamentally transformed the scale and scope of chemogenomic and functional genomic research, enabling systematic interrogation of biological systems at unprecedented resolution. The integration of diverse multiplexing approaches—from pooled genetic screens to single-cell multiomics and high-content phenotypic profiling—provides complementary insights into gene function, regulatory mechanisms, and compound mode of action. As these technologies continue to evolve, several exciting directions promise to further enhance their capabilities and applications.

The ongoing development of higher-plex methods will enable even more comprehensive profiling in single experiments. In proteomics, recent advances have expanded isobaric tagging from 2-plex to 54-plex approaches [16], while single-cell technologies now routinely profile tens of thousands of cells in individual runs [12]. Future improvements will likely focus on increasing multiplexing capacity while reducing technical artifacts such as index hopping in sequencing [1] and reporter ion interference in mass spectrometry [16].

The integration of multiplexed functional data with large-scale biobanks and clinical datasets represents another promising direction. As multiplexed assays are applied to characterize the functional impact of variants identified in population-scale sequencing studies, they will provide mechanistic insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies [14]. Similarly, the application of multiplexed chemogenomic approaches to patient-derived samples, including organoids and primary cells, will enhance the translational relevance of screening findings.

Finally, advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning will revolutionize the analysis and interpretation of multiplexed screening data. These approaches can identify complex patterns in high-dimensional data, predict variant functional effects, and prioritize candidate compounds or targets for further investigation. As multiplexed screening technologies continue to generate increasingly large and complex datasets, sophisticated computational methods will be essential for extracting biologically and clinically meaningful insights.

In conclusion, multiplexing has established itself as an indispensable pillar of modern chemogenomics and functional genomics, providing the technical foundation for large-scale, systematic investigations of biological systems. Through continued methodological refinement and innovative application, these approaches will continue to drive advances in basic research and therapeutic development for years to come.

Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for Error Correction

In the context of chemogenomic NGS screens, where the parallel testing of numerous chemical compounds on multiplexed biological samples is standard, ensuring data integrity is paramount. Accurate demultiplexing and variant calling are critical for correlating chemical perturbations with genomic outcomes. Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are two powerful barcoding strategies that, when integrated into next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows, provide robust error correction and mitigate common artifacts. UDIs are essential for accurate sample multiplexing, effectively preventing sample misassignment—a phenomenon known as index hopping [19] [20] [21]. In contrast, UMIs are molecular barcodes that tag individual nucleic acid fragments before amplification, enabling bioinformaticians to distinguish true biological variants from errors introduced during PCR amplification and sequencing, thereby increasing the sensitivity of detecting low-frequency variants [22] [23]. For chemogenomic screens, which often involve limited samples like single cells or low-input DNA/RNA, the combination of these technologies provides a framework for highly accurate, quantitative, and multiplexed analysis.

Table 1: Core Functions of UDIs and UMIs

| Feature | Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Sample multiplexing and demultiplexing | Identification and correction of PCR/sequencing errors |

| Level of Application | Per sample library | Per individual molecule |

| Key Benefit | Prevents sample misassignment due to index hopping | Enables accurate deduplication and rare variant detection |

| Impact on Cost | Reduces per-sample cost by enabling higher multiplexing | Prevents wasteful analysis of false positives, improving data quality |

Understanding Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs)

Principles and Design

Unique Dual Indexes consist of two unique nucleotide sequences—an i7 and an i5 index—ligated to opposite ends of each DNA fragment in a sequencing library [19] [21]. In a pool of 96 samples, for instance, each sample receives a truly unique pair of indexes; these index combinations are not reused or shared across any other sample in the pool [19] [20]. This design is a significant improvement over combinatorial dual indexing, where a limited set of indexes (e.g., 8 i7 and 8 i5) are combined to create a theoretical 64 unique pairs, but where sequences are repeated across a plate, increasing the risk of misassignment [19]. The uniqueness of the UDI pair is the key to its error-correction capability. During demultiplexing, the sequencing software expects only a specific set of i7-i5 combinations. Reads that exhibit an unexpected index pair—a result of index hopping where an index dimer erroneously attaches to a different library molecule—can be automatically identified and filtered out, thus preserving the integrity of sample identity [19] [21]. This is particularly crucial when using modern instruments with patterned flow cells, like the Illumina NovaSeq 6000, where index hopping rates can be significant [19] [21].

Application Note for Chemogenomic Screens

In a typical chemogenomic screen, researchers may treat hundreds of cell lines or pools with different chemical compounds and need to sequence them all in parallel. UDIs enable the precise pooling of these libraries, ensuring that the genomic data for a cell line treated with compound "A" is never confused with that treated with compound "B." This accurate sample tracking is the foundation for a reliable screen.

Protocol: Implementing UDI-Based Multiplexing

- Library Preparation and UDI Ligation: During the NGS library prep, use a kit or system that incorporates UDIs. Examples include the IDT for Illumina UD Indexes or the Twist Bioscience HT Universal Adapter System [19] [20]. The UDI adapters are ligated to the fragmented genomic DNA or cDNA.

- Library Pooling: Quantify the final concentration of each uniquely indexed library. Combine equimolar amounts of each library into a single pool. With a single UDI plate, you can confidently pool up to 96 samples [19].

- Sequencing: Sequence the pooled library on your chosen Illumina platform. Ensure the sequencing run includes the additional cycles required to read both the i7 and i5 indexes.

- Demultiplexing and Data Analysis: Use Illumina's standard demultiplexing software (e.g., Illumina DRAGEN BaseSpace App or bcl2fastq). The software will assign reads to their correct sample based on the expected UDI pairs and will filter out reads with index combinations not present in the sample sheet, effectively mitigating the effects of index hopping [19] [21].

Diagram 1: UDI Workflow for Error-Free Multiplexing. This diagram illustrates the process from library preparation to demultiplexing, highlighting the step where unexpected index pairs are filtered out.

Understanding Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

Principles and Design

Unique Molecular Identifiers are short, random nucleotide sequences (e.g., 8-12 bases) that are used to tag each individual DNA or RNA molecule in a sample library before any PCR amplification steps [22] [23]. The central premise is that every original molecule receives a random, unique "barcode." When this molecule is subsequently amplified by PCR, all resulting copies (PCR duplicates) will carry the identical UMI sequence. During bioinformatic analysis, reads that align to the same genomic location and share the same UMI are collapsed into a single "read family" and counted as a single original molecule [22] [23]. This process, known as deduplication, provides two major benefits: First, it removes PCR amplification bias, allowing for accurate quantification of transcript abundance in RNA-Seq or original fragment coverage in DNA-Seq [23]. Second, by generating a consensus sequence from the read family, random errors introduced during PCR or sequencing can be corrected, dramatically improving the sensitivity and specificity for detecting low-frequency variants [22] [24]. This is especially critical in chemogenomics for identifying rare somatic mutations induced by chemical treatments.

Application Note for Chemogenomic Screens

In screens aiming to quantify subtle changes in gene expression or to detect rare mutant alleles following chemical exposure, standard NGS workflows can be confounded by PCR duplicates and sequencing errors. UMIs allow researchers to trace the true molecular origin of each read, ensuring that quantitative measures of gene expression or variant allele frequency are accurate and reliable.

Protocol: Incorporating UMIs for Variant Detection

- Early UMI Incorporation: Introduce UMIs at the earliest possible step in library preparation to tag original molecules. For RNA-Seq, this can be during reverse transcription by using oligo(dT) primers containing a UMI sequence [23]. For DNA-Seq, use UMI-containing adapters, such as the NEBNext Unique Dual Index UMI Adaptors, during ligation [25] [24].

- Library Amplification and Sequencing: Proceed with PCR amplification and sequencing as normal. The UMI sequences will be co-amplified and sequenced along with the genomic DNA.

- Bioinformatic Processing with UMI-Aware Tools: Process the raw sequencing data using specialized tools like UMI-tools or AmpUMI [26]. The typical workflow involves:

- Extraction: Identifying and extracting the UMI sequence from each read.

- Consensus Building: Grouping reads into families based on their alignment coordinates and UMI sequence.

- Error Correction: Generating a high-quality consensus sequence for each read family, which corrects for random errors in individual reads.

- Deduplication: Collapsing each read family into a single, high-quality representative read for accurate quantification [26] [23] [24].

Diagram 2: UMI Workflow for Error Correction and Deduplication. The process shows how original molecules are tagged, amplified, and then bioinformatically processed to generate a consensus, correcting for PCR and sequencing errors.

The Combined Power of UDIs and UMIs

For the highest data integrity in demanding applications like chemogenomic NGS screens, UDIs and UMIs can and should be used together [21] [24]. They address orthogonal sources of error: UDIs correct for sample-level misassignment, while UMIs correct for molecule-level errors and biases. Using both technologies creates a powerful, multi-layered error-correction system. A study demonstrated that combining unique dual sample indexing with UMI molecular barcoding significantly improves data analysis accuracy, especially on patterned flow cells [24]. Furthermore, traditional methods for identifying PCR duplicates based on read mapping coordinates can be highly inaccurate, with one analysis showing that up to 90% of reads flagged as duplicates this way were, in fact, unique molecules [24]. UMI-based deduplication prevents this loss of valuable data, ensuring maximum use of sequencing depth.

Table 2: Comparison of Error Correction Strategies

| Error Source | Impact on Data | Corrective Technology | Mechanism of Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index Hopping | Sample misassignment; cross-contamination of samples | UDIs | Bioinformatic filtering of reads with invalid i7-i5 index pairs |

| PCR Duplication | Amplification bias; inaccurate quantification of gene expression/variant frequency | UMIs | Bioinformatic grouping and deduplication of reads sharing a UMI and alignment |

| PCR/Sequencing Errors | False positive variant calls, especially for low-frequency variants | UMIs | Generating a consensus sequence from a family of reads sharing a UMI |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is critical for successfully implementing UDI and UMI protocols. The following table details key commercially available solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UDI and UMI Workflows

| Product Name | Supplier | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDT for Illumina UD Indexes | Illumina/IDT | Provides a plate of unique dual indexes for highly accurate sample multiplexing. | Whole-genome sequencing, complex multiplexing [19] |

| Twist Bioscience HT Universal Adapter System | Twist Bioscience | Offers 3,072 empirically tested unique indexes for large-scale multiplexing with minimal barcode collisions. | Population-scale genomics, rare disease gene panels [20] |

| NEBNext Unique Dual Index UMI Adaptors | New England Biolabs | Provides pre-annealed adapters containing both UMIs and UDIs in a single system. | Sensitive detection of low-frequency variants in DNA-Seq (including PCR-free) [25] [24] |

| Zymo-Seq SwitchFree 3' mRNA Library Kits | Zymo Research | All-in-one kit for RNA-Seq with built-in UMIs and UDIs, requiring no additional purchases. | Accurate gene expression quantification, especially for low-input RNA [21] |

| UMI-tools | Open Source | A comprehensive bioinformatics package for processing UMI data, including extraction, deduplication, and error correction. | Downstream analysis of UMI-tagged sequencing data [26] |

The integration of Unique Dual Indexes and Unique Molecular Identifiers represents a significant advancement in the reliability of next-generation sequencing. For researchers conducting chemogenomic screens, where the cost of error is high and the signals of interest can be subtle, these technologies are no longer optional luxuries but essential components of a robust NGS workflow. UDIs ensure that the complex data from multiplexed samples are assigned correctly, while UMIs peel back the layers of technical noise to reveal the true biological signal. By adopting the detailed protocols and reagent solutions outlined in this application note, scientists can achieve unprecedented levels of accuracy in their data, leading to more confident and impactful discoveries in drug development and chemical genomics.

Integrating Multiplexing with Multi-Omics Approaches for Comprehensive Biological Insight

The convergence of multiplexing technologies and multi-omics approaches represents a paradigm shift in biological research, enabling unprecedented depth and breadth in molecular profiling. Multiplexing, the simultaneous analysis of multiple molecules or samples, synergizes with multi-omics—the integrative study of various molecular layers—to provide a holistic view of biological systems [27]. This integration is particularly transformative for chemogenomic NGS screens, where understanding compound-genome interactions requires capturing complex, multi-layered molecular responses. The ability to pool hundreds of samples through multiplex sequencing exponentially increases experimental throughput while reducing per-sample costs, making large-scale chemogenomic studies feasible [1]. However, this powerful combination introduces computational and analytical challenges related to data heterogeneity, integration complexity, and interpretive frameworks that must be addressed through sophisticated computational strategies [28] [29].

Foundational Concepts and Integration Strategies

Multiplexing and Multi-Omics: A Synergistic Relationship

Multiplexing technologies and multi-omics approaches are intrinsically complementary. Multiplexing addresses the "who" and "what" by enabling simultaneous measurement of multiple analytes, while multi-omics contextualizes these measurements across biological layers to reveal functional interactions [27]. In chemogenomic screens, this synergy allows researchers to not only identify hits but also understand the mechanistic basis of compound action across genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic dimensions.

Spatial multiplexing adds crucial contextual information by preserving the anatomical location of molecular measurements, revealing how cellular microenvironment influences compound response [27]. This is particularly valuable in complex tissues like tumors, where drug penetration and activity vary across regions. Temporal multiplexing through longitudinal sampling captures dynamic molecular responses to compounds over time, illuminating pathway activation kinetics and adaptive resistance mechanisms.

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies for Chemogenomics

Integrating diverse molecular data types requires strategic approaches that balance completeness with computational feasibility. Three principal integration strategies have emerged, each with distinct advantages for chemogenomic applications:

Table: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies for Chemogenomic Screens

| Integration Strategy | Timing of Integration | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration (Concatenation-based) | Before analysis | Captures all cross-omics interactions; preserves raw information | High dimensionality; computationally intensive; prone to overfitting | Discovery of novel, complex biomarker patterns across omics layers [29] [30] |

| Intermediate Integration (Transformation-based) | During analysis | Reduces complexity; incorporates biological context through networks | May lose some raw information; requires domain knowledge | Pathway-centric analysis; network pharmacology studies [28] [29] |

| Late Integration (Model-based) | After individual analysis | Handles missing data well; computationally efficient; robust | May miss subtle cross-omics interactions | Predictive modeling of drug response; patient stratification [29] [31] |

Early integration (also called concatenation-based or low-level integration) merges raw datasets from multiple omics layers into a single composite matrix before analysis [30]. While this approach preserves all potential interactions, it creates extreme dimensionality that requires careful handling through regularization or dimensionality reduction techniques.

Intermediate integration (transformation-based or mid-level) first transforms each omics dataset into intermediate representations—such as biological networks or latent factors—before integration [29]. Network-based approaches are particularly powerful for chemogenomics, as they can map compound-induced perturbations across molecular interaction networks to identify key regulatory nodes and emergent properties [28].

Late integration (model-based or high-level) builds separate models for each omics data type and combines their outputs [29] [31]. This approach is exemplified by ensemble methods that aggregate predictions from omics-specific models, making it robust to missing data types—a common challenge in large-scale screens.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Sample Preparation and Multiplexing Considerations

Robust sample preparation is foundational to successful multi-omics studies. The general workflow for NGS sample preparation involves four critical steps: (1) nucleic acid extraction, (2) library preparation, (3) amplification, and (4) purification and quality control [17]. Each step requires careful optimization to maintain compatibility across omics layers.

For multiplexed chemogenomic screens, unique dual indexes (UDIs) are essential for sample pooling and demultiplexing [1]. UDIs contain two separate barcode sequences that uniquely identify each sample, dramatically reducing index hopping and cross-contamination between samples. Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) provide an additional layer of accuracy by tagging individual molecules before amplification, enabling error correction and accurate quantification by accounting for PCR duplicates [1].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplexed Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique Dual Indexes | Sample identification during multiplex sequencing | Minimize index hopping; enable high-level multiplexing | Track multiple cell lines/conditions in pooled screens [1] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Molecular tagging for error correction | Account for PCR amplification bias; improve variant detection | Accurate quantification of transcriptional responses to compounds [1] |

| Cross-linking Reversal Reagents | Epitope retrieval for FFPE samples | Overcome formalin-induced crosslinks; optimize antibody binding | Enable archival sample analysis for longitudinal studies [27] |

| Multiplexed Imaging Panels | Simultaneous detection of multiple proteins | Validate compound effects across signaling pathways | Spatial resolution of drug target engagement in complex tissues [27] |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | High-throughput library preparation | Reduce manual errors; improve reproducibility | Enable large-scale compound library screening [17] |

Sample Type Considerations for Multi-Omics

Sample selection and processing directly impact data quality and integration potential. The two primary sample types—FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) and frozen samples—offer complementary advantages and limitations for multi-omics studies [27]:

FFPE samples represent the most widely available archival material, offering structural preservation and stability at room temperature. However, formalin fixation creates protein-DNA and protein-protein crosslinks that can compromise nucleic acid quality and antigen accessibility. Lipid removal during processing eliminates lipidomic analysis potential. Recent advances in antigen retrieval methods have significantly improved FFPE compatibility with proteogenomic approaches [27].

Frozen samples preserve molecular integrity without crosslinking, making them ideal for lipidomics, metabolomics, and native protein complex analysis. While requiring continuous cold storage, frozen tissues provide superior quality for most omics applications, particularly when analyzing labile metabolites or post-translational modifications [27].

Workflow for multiplexed multi-omics sample processing. The diagram illustrates parallel processing paths for different sample types (FFPE, frozen) and molecular analyses, converging through multiplexing before integrated data analysis.

Computational Integration and Analysis

AI and Machine Learning Approaches

The complexity of multi-omics data demands advanced computational approaches to extract meaningful biological insights. Deep learning models have emerged as powerful tools for handling high-dimensional, non-linear relationships inherent in integrated omics datasets [29] [31].

Autoencoders and Variational Autoencoders learn compressed representations of high-dimensional omics data in a lower-dimensional latent space, facilitating integration and revealing underlying biological patterns [29]. These unsupervised approaches are particularly valuable for hypothesis generation and data exploration in chemogenomic screens.

Graph Convolutional Networks operate directly on biological networks, aggregating information from connected nodes to make predictions [29]. In chemogenomics, GCNs can model how compound-induced perturbations propagate through molecular interaction networks to identify key regulatory nodes and emergent properties.

Multi-task learning frameworks like Flexynesis enable simultaneous prediction of multiple outcome variables—such as drug response, toxicity, and mechanism of action—from integrated omics data [31]. This approach mirrors the multi-faceted decision-making required in drug development, where therapeutic candidates must be evaluated across multiple efficacy and safety dimensions.

Addressing Analytical Challenges

Multi-omics integration introduces several analytical challenges that must be addressed to ensure robust conclusions:

Batch effects represent systematic technical variations that can obscure biological signals [29]. Experimental design strategies such as randomization and blocking, combined with statistical correction methods like ComBat, are essential for mitigating these effects. The inclusion of reference standards and control samples further improves cross-batch comparability.

Missing data is inevitable in large-scale multi-omics studies, particularly when integrating across platforms and timepoints [29]. Imputation methods ranging from simple k-nearest neighbors to sophisticated matrix factorization approaches can estimate missing values based on patterns in the observed data. The selection of appropriate imputation strategies depends on the missingness mechanism and proportion.

Data harmonization ensures that measurements from different platforms and laboratories are comparable [29]. This process includes normalization to adjust for technical variations, standardization of data formats, and annotation using common ontologies. Frameworks like MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) provide robust implementations of these principles for integrative analysis [32].

Applications in Precision Oncology and Drug Development

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification