Mapping the Chemical Genetic Landscape: High-Throughput NGS Strategies for Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in high-throughput chemical genetic interaction mapping, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery.

Mapping the Chemical Genetic Landscape: High-Throughput NGS Strategies for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in high-throughput chemical genetic interaction mapping, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. It provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational NGS principles and their direct application in large-scale screening. The content delves into advanced methodological workflows for identifying drug targets and mechanisms, followed by practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assay sensitivity and reproducibility. Finally, it outlines rigorous analytical validation frameworks and comparative analyses of emerging technologies, offering a holistic perspective on deploying robust, data-driven NGS pipelines to accelerate therapeutic development.

The NGS Revolution: Core Technologies Powering Chemical Genetic Screens

The evolution from Sanger sequencing to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in genomics, transforming biological research from a targeted, small-scale endeavor to a comprehensive, systems-level science. This transition has been particularly transformative for high-throughput chemical-genetic interaction mapping, a research area essential for understanding gene function and identifying novel therapeutic targets. Where Sanger sequencing provided a precise but narrow snapshot of genetic information, NGS delivers a massively parallelized, panoramic view, enabling researchers to interrogate entire genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes in single experiments [1] [2].

The core technological advance lies in parallelism. While Sanger sequencing processes a single DNA fragment per run, NGS simultaneously sequences millions to billions of fragments, creating an unprecedented scale of data output [1] [3]. This democratization has drastically reduced costs and time requirements, moving genome sequencing from a multinational project costing billions to a routine laboratory procedure accessible with standard research funding [3] [4]. The implementation of NGS in chemical-genetic interaction studies, such as the E-MAP (Epistatic Miniarray Profile) and PROSPECT platforms, has empowered researchers to systematically quantify how genetic backgrounds modulate chemical compound effects, rapidly elucidating mechanisms of action for drug discovery [5] [6].

Quantitative Comparison: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS

The quantitative differences between Sanger and NGS technologies highlight the revolutionary impact of parallelization on genomic research. The following table summarizes key performance metrics that have enabled large-scale genomics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Volume | Single DNA fragment at a time [1] | Millions to billions of fragments simultaneously [1] [3] |

| Throughput | Low (suitable for single genes) [1] [7] | Extremely high (entire genomes or populations) [3] |

| Human Genome Cost | ~$3 billion (Human Genome Project) [3] | Under $1,000 [3] [4] |

| Human Genome Time | 13 years (Human Genome Project) [3] | Hours to days [3] |

| Read Length | 500-1000 base pairs [7] | 50-600 base pairs (short-read); up to millions (long-read) [3] |

| Detection Sensitivity | ~15-20% limit of detection [1] | Down to 1% for low-frequency variants [1] |

| Applications | Single gene analysis, validation [1] [7] | Whole genomes, transcriptomes, epigenomes, metagenomes [1] [2] |

| Data Analysis | Simple chromatogram interpretation [7] | Complex bioinformatics pipelines required [3] |

The cost and time reductions have been particularly dramatic. The first human genome sequence required 13 years and nearly $3 billion to complete using Sanger-based methods [3]. Today, NGS platforms like the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus can sequence more than 20,000 whole genomes per year at a cost of approximately $200 per genome [4]. This efficiency gain of several orders of magnitude has made large-scale genomic studies feasible for individual research institutions, truly democratizing genomic capability.

NGS Workflow for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping

The application of NGS to chemical-genetic interaction profiling follows a standardized workflow that integrates molecular biology, high-throughput screening, and computational analysis. The PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform exemplifies this approach for antimicrobial discovery [6].

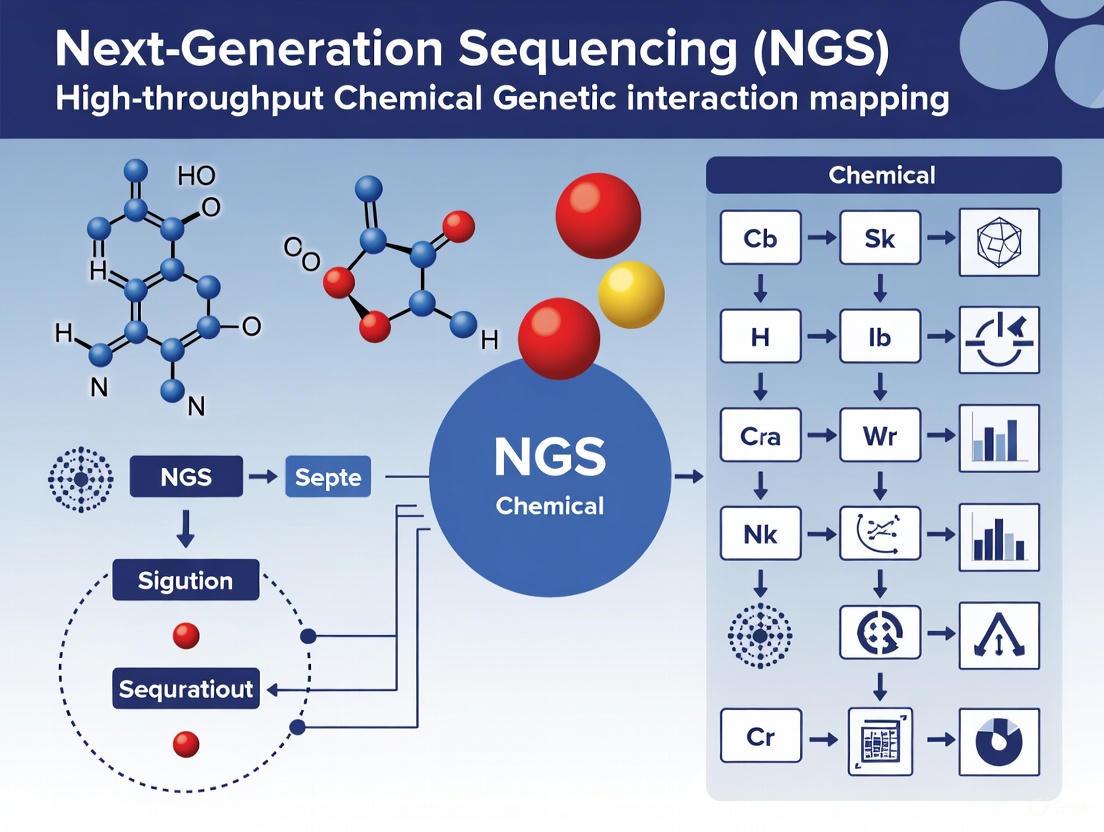

Diagram 1: NGS Chemical-Genetic Screening Workflow. This workflow shows the key steps from library preparation to mechanism of action (MOA) prediction.

Protocol: PROSPECT Platform for Mechanism of Action Prediction

Principle: Identify chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs) by screening compound libraries against pooled hypomorphic mutants of essential genes, using NGS to quantify strain abundance changes and predict mechanisms of action (MOA) through comparative profiling [6].

Materials:

- Pooled hypomorphic Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant library (each strain with unique DNA barcode)

- Compound library (437 reference compounds with known MOA + experimental compounds)

- NGS library preparation reagents

- Illumina sequencing platform (or equivalent)

- Bioinformatics computational resources

Procedure:

Library Preparation and Compound Treatment

- Grow pooled hypomorphic mutant library to mid-log phase

- Distribute aliquots of pooled library into 96-well plates containing compound treatments (include DMSO vehicle controls)

- Incubate for multiple generations (typically 5-7 population doublings)

- Harvest cells by centrifugation

DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification

- Extract genomic DNA from harvested cell pellets

- Amplify strain-specific DNA barcodes with primers containing NGS adapter sequences

- Purify amplified libraries using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads

- Quantify library concentration by fluorometry

NGS Sequencing and Data Acquisition

- Pool purified barcode libraries at equimolar concentrations

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 500,000 reads per condition)

- Demultiplex sequences by sample and align to reference barcode database

- Calculate relative abundance of each mutant strain across conditions

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Scoring

- For each compound-mutant pair, calculate CGI score as:

- ε = PABobserved - PABexpected

- Where PABobserved is the observed growth phenotype of the double mutant (hypomorph + compound)

- And PABexpected is the expected phenotype if no interaction exists [5]

- Normalize scores across experiments and replicates

- Generate CGI profile for each compound (vector of all mutant interaction scores)

- For each compound-mutant pair, calculate CGI score as:

Mechanism of Action Prediction

- Compare CGI profiles of experimental compounds to reference set using Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis

- Calculate similarity metrics (e.g., Pearson correlation) between query and reference profiles

- Assign MOA predictions based on highest similarity references

- Validate predictions through follow-up experiments (e.g., resistance mutation analysis)

Notes: This protocol enables high-throughput MOA prediction with reported sensitivity of 70% and precision of 75% in leave-one-out cross-validation [6]. Include appropriate controls and replicates to ensure statistical robustness.

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of NGS-based chemical-genetic interaction mapping requires specific research tools and platforms. The following table details essential components for establishing these workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic Mutant Library | Collection of strains with reduced essential gene function; enables detection of hypersensitivity [6] | Each strain contains unique DNA barcode for NGS quantification; ~400-800 mutants provides optimal coverage [5] [6] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Prepare amplified barcode libraries compatible with sequencing platforms [6] | SPRI bead-based cleanup preferred for consistency; incorporate dual index primers for multiplexing |

| Illumina Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput short-read sequencing for barcode quantification [1] [2] | NovaSeq X Series enables 20,000+ genomes annually; MiniSeq suitable for smaller screens [4] |

| TSO 500 Content | Comprehensive genomic profiling for oncology applications; detects variants, TMB, MSI [4] | Uses both DNA and RNA; identifies biomarkers for immunotherapy response |

| TruSight Oncology Comprehensive | In vitro diagnostic kit for cancer biomarker detection in Europe [4] | Companion diagnostic for NTRK fusion cancer therapy (Vitrakvi) |

| Reference Compound Set | Curated compounds with annotated mechanisms of action [6] | 437+ compounds with diverse MOAs essential for training PCL analysis predictions |

NGS Data Analysis Pathway

The computational analysis of NGS data from chemical-genetic interaction studies follows a structured pathway from raw sequence data to biological insight. The PCL (Perturbagen Class) analysis method exemplifies this process for mechanism of action prediction.

Diagram 2: NGS Data Analysis Pathway. This pathway illustrates the computational workflow from sequence data to biological insight.

Protocol: PCL Analysis for MOA Prediction

Principle: Infer compound mechanism of action by comparing its chemical-genetic interaction profile to a curated reference set of profiles from compounds with known targets [6].

Materials:

- CGI profiles for reference compounds (n ≥ 400 recommended)

- CGI profiles for experimental compounds

- Computational environment (R, Python, or specialized software)

- High-performance computing resources for large datasets

Procedure:

Reference Set Curation

- Compile CGI profiles for 400+ compounds with annotated MOAs

- Include established clinical agents, tool compounds, and validated leads

- Ensure representation of diverse target classes and mechanisms

Similarity Metric Calculation

- For each query compound, compute similarity to all reference profiles

- Use Pearson correlation or cosine similarity as distance metric

- Apply appropriate normalization to account for batch effects

MOA Assignment and Confidence Scoring

- Assign MOA based on highest similarity reference matches

- Calculate confidence scores using bootstrap resampling or Bayesian methods

- Apply threshold criteria (e.g., minimum correlation coefficient > 0.4)

Validation and Experimental Follow-up

- For high-confidence predictions, confirm through orthogonal methods

- Test against resistant mutants (e.g., qcrB alleles for QcrB inhibitors)

- Evaluate hypersensitivity in pathway-deficient strains

- Perform chemical optimization for initial hits with weak activity

Notes: In validated studies, PCL analysis achieved 69% sensitivity and 87% precision in MOA prediction for antitubercular compounds [6]. The method successfully identified novel scaffolds targeting QcrB that were subsequently validated experimentally.

The democratization of large-scale genomics through NGS has fundamentally transformed chemical-genetic interaction research, enabling systematic, high-throughput mapping of compound mechanisms of action. The massively parallel nature of NGS provides the scalability required to profile hundreds of compounds against thousands of genetic backgrounds, an undertaking impossible with Sanger sequencing. As NGS technologies continue to advance in accuracy, throughput, and affordability, their integration into drug discovery pipelines will accelerate the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets, particularly for complex diseases like tuberculosis and cancer. The protocols and methodologies detailed herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these powerful approaches in their own genomic research programs.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become the cornerstone of high-throughput functional genomics, enabling researchers to decipher complex genetic and chemical-genetic interactions on an unprecedented scale. In the context of chemical genetic interaction mapping—a powerful approach for elucidating small molecule mechanisms of action (MOA) and identifying novel therapeutic targets—the choice between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies represents a critical strategic decision [6]. Each technology offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully considered based on the specific goals of the research, whether focused on comprehensive variant detection, structural variant identification, or resolving complex genomic regions.

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling platforms such as PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) generate massive datasets by measuring how chemical perturbations affect pooled mutants depleted of essential proteins [6]. The resulting interaction profiles serve as fingerprints for MOA prediction, but their resolution depends fundamentally on the sequencing methodology employed. Similarly, large-scale genetic interaction studies, such as systematic pairwise gene double knockouts in human cells, require sequencing solutions that can accurately capture complex phenotypic readouts [8]. This application note provides a structured comparison of short-read and long-read sequencing technologies within this context, offering detailed protocols and practical guidance for researchers engaged in high-throughput interaction mapping.

Technology Comparison: Key Characteristics and Performance Metrics

The selection between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies involves balancing multiple factors including read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost. The table below summarizes the core technical characteristics of each approach relevant to interaction mapping applications.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Short-Read and Long-Recent Sequencing Technologies

| Characteristic | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | 50-300 bp [9] | 10 kb to >100 kb; up to hundreds of kilobases for ONT ultra-long reads [10] [11] |

| Primary Platforms | Illumina, Ion Torrent [9] | Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [10] |

| Accuracy | >99.9% [11] | Varies: PacBio HiFi >99% [11]; ONT 87-98% [11] |

| Key Strengths | High accuracy, low cost per base, established clinical applications [9] | Resolves complex genomic regions, detects structural variants, enables haplotype phasing [12] [10] |

| Limitations for Interaction Mapping | Limited detection of structural variants and repetitive regions [9] | Higher error rates (historically), higher cost per base, more complex data analysis [10] |

| Optimal Use Cases in Interaction Mapping | Variant calling in non-repetitive regions, large-scale screening projects requiring high accuracy at low cost [13] | Resolving complex structural variations, haplotype phasing in regions with high homology, de novo assembly [12] [10] |

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that both technologies can be effectively applied to microbial genomics and epidemiology. A 2025 comparison of short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore) sequencing for microbial pathogen epidemiology found that long-read assemblies were more complete, while variant calling accuracy depended on the computational approach used [13]. Importantly, the study demonstrated that computationally fragmenting long reads could improve variant calling accuracy, allowing researchers to leverage the assembly advantages of long-read sequencing while maintaining high accuracy in epidemiological analyses [13].

Experimental Protocols for Interaction Mapping Applications

Protocol 1: Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling Using Short-Read Sequencing

The PROSPECT platform provides a robust methodology for high-throughput chemical-genetic interaction mapping compatible with short-read sequencing. This protocol enables simultaneous small molecule discovery and MOA identification by screening compounds against pooled hypomorphic mutants of essential genes [6].

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Generate a pool of hypomorphic Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants, each engineered to be proteolytically depleted of a different essential protein and tagged with a unique DNA barcode [6].

- Chemical Screening: Expose the pooled mutant library to compound treatments across multiple dose conditions, including controls.

- Sample Collection: Harvest cells after appropriate incubation period and extract genomic DNA.

- Barcode Amplification: Amplify mutant-specific barcodes using PCR with Illumina-compatible adapters.

- Sequencing: Perform short-read sequencing on Illumina platform (typically 2x150 bp) to quantify barcode abundances [6].

- Data Analysis:

- Align sequences to a barcode reference genome using optimized aligners (e.g., MAQ) [14]

- Quantify barcode frequencies across conditions

- Generate chemical-genetic interaction profiles representing each compound's effect on mutant growth

- Apply Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis to compare interaction profiles to reference compounds with known MOA [6]

Quality Control Considerations:

- Include replicate screens for reproducibility assessment

- Implement randomization schemes to control for batch effects

- Use positive and negative control compounds with established MOA

- Apply neighborhood quality standards (NQS) during variant calling to ensure accuracy [14]

Protocol 2: Genetic Interaction Mapping Using Long-Read Sequencing

This protocol adapts long-read sequencing for large-scale genetic interaction studies, such as systematic pairwise double knockout screens, where comprehensive variant detection and structural variant identification are priorities.

Procedure:

- Library Construction:

- Phenotypic Selection: Culture transduced cells under relevant selective conditions for appropriate duration.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Use high molecular weight DNA extraction protocols to preserve long fragments.

- Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Sequencing:

- Perform sequencing on appropriate platform (PacBio Sequel/Revio or ONT PromethION)

- Aim for sufficient coverage (typically 50-100x) to detect guide RNA combinations

- Data Analysis:

- Perform base calling and read filtering (e.g., PacBio HiFi read generation)

- Align reads to reference genome using long-read optimized aligners

- Call guide RNA identities and abundances from sequencing data

- Calculate genetic interaction scores based on deviation from expected double mutant phenotypes [8]

Quality Control Considerations:

- Assess DNA integrity prior to library preparation (A260/280 ratio, fragment size distribution)

- Include control guide RNAs with known phenotypes

- Monitor sequencing run metrics (read length distribution, accuracy, throughput)

- Validate key interactions through orthogonal assays

Workflow Visualization: From Experimental Design to Data Analysis

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key steps in short-read and long-read sequencing approaches for interaction mapping applications, highlighting critical decision points and methodology-specific procedures.

Figure 1: Short-read sequencing workflow for chemical-genetic interaction profiling, adapted from the PROSPECT platform [6]

Figure 2: Long-read sequencing workflow for genetic interaction mapping using combinatorial CRISPR approaches [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of interaction mapping studies requires careful selection of reagents, platforms, and computational tools. The following table summarizes key solutions used in the featured protocols and applications.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Interaction Mapping Studies

| Category | Product/Platform | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | Short-read sequencing for barcode quantification | High accuracy (>99.9%), high throughput [11] |

| PacBio Sequel II/Revio | HiFi long-read sequencing | >99% accuracy, 15-25 kb read length [10] [11] | |

| Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Ultra-long read sequencing | Reads up to hundreds of kilobases, direct epigenetic detection [10] [11] | |

| CRISPR Systems | Cas12a (Cpf1) | Combinatorial double knockout screens | Processing of two gRNAs from single transcript [8] |

| Cas9 | Standard gene knockout | High efficiency, well-validated guides | |

| Library Prep Kits | SMRTbell Prep Kit | PacBio long-read library preparation | Circular consensus sequencing for high accuracy [11] |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | Nanopore library preparation | Compatible with ultra-long reads [11] | |

| Analysis Tools | MAQ | Short-read alignment and variant calling | Mapping quality scores, mate-pair utilization [14] |

| DRAGEN | Secondary analysis for mapped reads | Hardware-accelerated, supports constellation mapping [15] | |

| PCL Analysis | Chemical-genetic interaction profiling | Reference-based MOA prediction [6] |

Implementation Guidance: Strategic Technology Selection

When planning interaction mapping studies, researchers should consider the following decision framework to select the most appropriate sequencing technology:

Choose short-read sequencing when:

- Primary research goal involves single nucleotide variant calling or small indel detection

- Studying regions with minimal repeats or structural complexity

- Project requires high sample throughput at minimal cost

- Working with established reference genomes with good annotation

- Applications include barcode quantification in pooled screens [6]

Choose long-read sequencing when:

- Research focuses on structural variant detection or characterization

- Studying regions with high repeat content or segmental duplications

- Haplotype phasing is essential for interpreting genetic interactions

- De novo assembly is required for non-model organisms

- Direct detection of epigenetic modifications is desired [10]

Consider hybrid approaches when:

- Budget allows for combining cost-effective short-read sequencing with targeted long-read sequencing

- Validating structural variants detected in short-read data requires orthogonal confirmation

- Different genomic regions require different resolution approaches

For comprehensive genetic interaction mapping studies, such as the SLC transporter interaction map that utilized both Cas12a and Cas9 systems [8], a hybrid strategy may provide optimal balance between comprehensive variant detection and ability to resolve complex genomic regions.

The strategic selection between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies represents a critical decision point in designing effective interaction mapping studies. Short-read technologies offer established, cost-effective solutions for variant calling and barcode-based screening applications, while long-read platforms provide unparalleled resolution for complex genomic regions and structural variants. As both technologies continue to evolve, with improvements in accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness, their application to chemical and genetic interaction mapping will further expand our understanding of biological systems and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

Researchers should consider their specific biological questions, genomic contexts, and analytical requirements when selecting between these complementary technologies, remaining open to hybrid approaches that leverage the unique strengths of each platform. The continued development of specialized analysis methods, such as PCL analysis for MOA prediction [6] and optimized variant calling pipelines for long-read data [13], will further enhance the utility of both approaches for deciphering complex genetic interactions.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling the unbiased, systematic profiling of chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs) on a massive scale. In high-throughput chemical-genetic interaction mapping, the fitness of thousands of engineered microbial or human cell mutants is measured simultaneously in response to compound treatment [6] [16]. This approach generates rich CGI profiles—vectors of mutant fitness scores—that reveal a compound's mechanism of action (MOA) by identifying hypersensitive or resistant mutants [6]. The entire paradigm depends critically on a robust NGS workflow to track mutant abundances in pooled screens via DNA barcode sequencing [16]. This application note details the three core technical components—library preparation, cluster generation, and sequencing by synthesis (SBS)—that underpin reliable CGI profiling, providing detailed protocols framed within the context of high-throughput drug discovery research.

Core NGS Workflow Components

Library Preparation

Library preparation converts genomic DNA or cDNA into a sequencing-compatible format by fragmenting samples and adding platform-specific adapters [17] [18] [19]. In CGI screens, this process handles DNA barcodes that uniquely identify each mutant strain in a pooled collection [16].

Protocol: DNA Sequencing Library Preparation for Illumina Systems [19]

- Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction and Qualification Isolate genetic material from samples (e.g., bulk tissue, individual cells, biofluids). Assess purity using UV spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8 for DNA; ~2.0 for RNA) and quantify using fluorometric methods [17].

- Step 2: DNA Fragmentation

Fragment purified DNA to desired sizes (typically 300–600 bp). Choose one of the following methods:

- Mechanical Shearing: Use focused acoustic energy (Covaris) for unbiased, consistent fragmentation with minimal sample loss.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Employ endonuclease cocktails for streamlined, automatable fragmentation requiring lower DNA input.

- Transposon-Based Tagmentation: Simultaneously fragment and tag DNA with adapters in a single reaction, circumventing traditional fragmentation and ligation steps [19].

- Step 3: End Repair and A-Tailing

Convert fragmented DNA's mixed overhangs into blunt ends, phosphorylate 5' ends, and add a single 'A' base to 3' ends to facilitate adapter ligation. This involves:

- Filling in 5' overhangs (5'→3' polymerase activity).

- Removing 3' overhangs (3'→5' exonuclease activity).

- Phosphorylating 5' ends (T4 polynucleotide kinase).

- Adding 'A' to 3' ends (A-tailing using Klenow fragment exo– or Taq polymerase) [19].

- Step 4: Adapter Ligation Ligate duplex oligonucleotide adapters to both ends of the A-tailed fragments. Adapters contain:

- Step 5: Library Amplification and Clean-Up Amplify the adapter-ligated library via limited-cycle PCR to enrich for properly constructed fragments. Purify and quantify the final library, then normalize concentrations before sequencing [19].

Table 1: DNA Fragmentation Methods Comparison

| Method | Principle | Best For | Input DNA | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Shearing | High-frequency sound waves | Unbiased fragmentation, consistent size | Standard input (μg) | Minimal bias, high consistency | Specialized equipment (Covaris) |

| Enzymatic Digestion | Sequence-specific endonucleases | Low-input samples, automation | Low input (ng-μg) | Fast, simple, automatable | Potential sequence bias |

| Tagmentation | Transposase-mediated cut & paste | Ultra-fast library prep | Standard input | Single-tube reaction, fastest | Optimization for complex genomes |

Cluster Generation

Cluster generation amplifies single DNA molecules locally on a flow cell surface to create thousands of identical copies, forming detectable "clusters" that provide sufficient signal intensity for sequencing [18].

Protocol: Bridge Amplification on an Illumina Flow Cell [18]

- Step 1: Flow Cell Priming The flow cell is a glass surface coated with a lawn of two types of oligonucleotides (P5 and P7) that are complementary to the adapters ligated during library preparation [18].

- Step 2: Template Loading and Binding Denature the prepared library into single strands and load it onto the flow cell. Single-stranded DNA fragments bind complementarily to either P5 or P7 oligos on the flow cell surface.

- Step 3: Bridge Amplification

- The bound template is copied by a polymerase, forming a double-stranded bridge.

- The double-stranded molecule is denatured, leaving two single-stranded copies attached to the flow cell.

- This process repeats over ~30 cycles, with each strand bending over to "bridge" to the opposite oligo and serve as a template for copying.

- The result is a dense cluster of ~1,000 identical DNA molecules localized within a sub-micron area [18].

- Step 4: Strand Denaturation and Cleavage After cluster growth, reverse strands are cleaved and washed away, leaving forward strands ready for sequencing. For paired-end reads, the process reverses after the first read to sequence from the opposite end [18].

Sequencing by Synthesis

Sequencing by synthesis is the cyclic process of determining the nucleotide sequence of each cluster through reversible terminator chemistry [18].

Protocol: Illumina's Four-Color SBS Chemistry [18]

- Step 1: Primer Binding and Initialization A sequencing primer binds to the adapter sequence adjacent to the DNA template of each cluster.

- Step 2: Cyclic Nucleotide Incorporation and Imaging

For each cycle, the flow cell is flooded with four fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides.

- Incorporation: DNA polymerase incorporates a single complementary nucleotide onto the growing strand. The reversible terminator blocks further extension.

- Imaging: A high-resolution camera takes four images (one for each laser-excited color channel: A, C, G, T) to determine the identity of the incorporated base at every cluster.

- Cleavage: The fluorescent dye and terminator are chemically cleaved from the nucleotide, enabling the next incorporation cycle.

- Step 3: Base Calling

Instrument software performs base calling, identifying the sequence of nucleotides for each cluster based on the fluorescent signals. The quality of each base call is assessed by a Phred-like Q score:

Q = -10 log₁₀(P), where P is the probability of an incorrect base call. A Q-score of 30 (99.9% accuracy) is standard for high-quality data [20] [18]. - Step 4: Read Completion and Paired-End Sequencing After reading the forward strand, the template can be regenerated in situ to sequence the reverse strand from the opposite end, generating paired-end reads for improved alignment accuracy [18].

Table 2: Key Sequencing Quality Control Metrics

| Metric | Description | Target Value/Range | Significance in CGI Profiling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q Score | Probability of an incorrect base call [20] | >30 (99.9% accuracy) | Ensures accurate barcode counting for mutant abundance |

| Error Rate | Percentage of incorrectly called bases per cycle [20] | <0.1% | Minimizes false positives/negatives in interaction calls |

| Cluster Density | Clusters per mm² on flow cell | Platform-dependent optimal range | Affects data yield and crosstalk; under/over-clustering harms data |

| % Bases ≥ Q30 | Proportion of bases with QScore≥30 [20] | >75-80% | Indicator of overall run success and data usability |

| Phasing/Prephasing | % clusters falling behind/ahead [20] | <1% per cycle | Reduces signal dephasing, maintains read length and quality |

Application in Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping

In high-throughput CGI profiling, the NGS workflow is applied to sequence DNA barcodes that serve as proxies for mutant abundance [6] [16]. The process involves:

- Pooled Screening: A collection of uniquely barcoded mutant strains (e.g., yeast deletion mutants or bacterial hypomorphs) is grown pooled together in the presence of a compound [6] [16].

- DNA Barcode Extraction and Library Prep: Genomic DNA is extracted from the pool pre- and post-compound treatment. The barcode regions are amplified via PCR and prepared for NGS following the library preparation protocol in Section 2.1 [16].

- Sequencing and Analysis: The barcode library is sequenced. The resulting data undergoes primary analysis (base calling), followed by secondary bioinformatics analysis to quantify barcode abundances and calculate fitness scores for each mutant, generating a chemical-genetic interaction profile [6] [16].

The PROSPECT platform for Mycobacterium tuberculosis exemplifies this, using NGS to quantify changes in barcode abundances from a pooled hypomorph library to identify hypersensitive strains and elucidate small molecule mechanism of action [6]. Similarly, high-throughput yeast chemical-genetic screens utilize multiplexed barcode sequencing (e.g., 768-plex) to profile thousands of compounds [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-based CGI Screens

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexed Barcode Library | Collection of mutant strains, each with a unique DNA barcode [16] | Enables pooled fitness assays; yeast (~5000 mutants) or Mtb (hypomorph) libraries are common [6] [16]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Commercial kit for end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation [19] | Select kit compatible with sequencing platform; ensures high efficiency for low-input barcode PCR products. |

| Indexed Adapters | Oligonucleotides with unique molecular barcodes [18] [19] | Critical for multiplexing many compound screens in one sequencing run, reducing cost per sample. |

| Flow Cell | Glass surface with covalently bound oligos for cluster generation [18] | Platform-specific consumable (e.g., Illumina); cluster density impacts data yield. |

| SBS Kit | Reagent kit containing enzymes and fluorescent nucleotides [18] | Core chemistry for sequencing; newer versions (XLEAP-SBS) offer improved speed/accuracy [17]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software for base calling, demultiplexing, and fitness analysis [17] [6] | Essential for translating raw sequence data into chemical-genetic interaction profiles. |

Chemical-genetic interaction mapping represents a powerful functional genomics approach that systematically explores how genetic perturbations modulate cellular responses to chemical compounds. By quantifying the fitness of gene mutants under chemical treatment, this methodology provides deep insights into drug mode-of-action, resistance mechanisms, and functional gene relationships. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has revolutionized this field, enabling unprecedented scalability and precision in mapping these interactions across entire genomes. This Application Note examines the fundamental principles, methodological frameworks, and practical applications of chemical-genetic interaction mapping, with particular emphasis on NGS-enabled high-throughput screening platforms that are transforming drug discovery and functional genomics.

Chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs) occur when the combination of a genetic mutation and a chemical compound produces an unexpected phenotype that cannot be readily predicted from their individual effects [21]. These interactions are typically measured by assessing cellular fitness—most commonly growth—when mutant strains are exposed to chemical treatments. CGIs manifest as either sensitivity (negative interaction), where the combination of mutation and compound produces a stronger than expected deleterious effect, or resistance (positive interaction), where the mutant exhibits enhanced survival under chemical treatment [22] [21].

The conceptual foundation of CGIs derives from classical genetic interaction studies, where synthetic lethality—a phenomenon where two non-lethal mutations become lethal when combined—demonstrated how functional relationships between genes could be systematically mapped [23]. Chemical-genetic approaches extend this principle by replacing one genetic perturbation with a chemical perturbation, thereby creating a powerful platform for connecting compounds to their cellular targets and mechanisms [21].

In the era of high-throughput genomics, NGS technologies have become indispensable for CGI profiling, enabling the parallel assessment of millions of genetic perturbations under diverse chemical conditions [3] [24]. This technological synergy has transformed CGI mapping from a targeted approach to a comprehensive systems biology tool.

Quantitative Frameworks for Defining Interactions

The accurate quantification of chemical-genetic interactions requires rigorous mathematical frameworks to distinguish meaningful biological interactions from expected additive effects. Multiple definitions have been developed, each with distinct statistical properties and applications.

Alternative Mathematical Definitions

Research by Mani et al. (2008) identified four principal mathematical definitions used for quantifying genetic interactions, each with practical consequences for interpretation [25]:

- Product Definition: Multiplies the individual fitness effects of single perturbations

- Additive Definition: Sums the individual fitness effects

- Log Definition: Utilizes logarithmic transformation of fitness values

- Min Definition: Uses the minimum fitness value of single mutants as reference

Comparative studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have demonstrated that while 52% of known synergistic genetic interactions were originally inferred using the Min definition, the Product and Log definitions (shown to be practically equivalent) proved superior for identifying bona fide functional relationships between genes and pathways [25].

Interaction Scoring and Classification

CGIs are quantitatively classified based on the deviation between observed and expected fitness values:

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Relationship | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Synergistic/Negative | Fitness < Expected | Gene mutation enhances compound sensitivity |

| Antagonistic/Positive | Fitness > Expected | Gene mutation confers resistance to compound |

| Neutral/Additive | Fitness ≈ Expected | No functional interaction |

| Suppressive | Double mutant fitter than sickest single mutant | One mutation suppresses effect of other |

Table 1: Classification of chemical-genetic interactions based on fitness deviations.

The quantitative measurement of these interactions enables the construction of chemical-genetic profiles that serve as functional fingerprints for compounds, revealing their cellular targets and mechanisms of action [22] [21].

NGS-Enabled Methodological Frameworks

The integration of NGS technologies has revolutionized CGI profiling through massively parallel sequencing of pooled mutant libraries, enabling genome-wide scalability previously unattainable with arrayed screening formats.

Essential Workflows and Experimental Design

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for NGS-enabled chemical-genetic interaction screening:

Figure 1: Workflow for NGS-enabled chemical-genetic interaction screening of pooled mutant libraries.

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of CGI screening requires carefully curated biological and chemical resources:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in CGI Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Mutant Libraries | Yeast deletion collection, E. coli Keio collection, CRISPRi libraries | Provides systematic genetic perturbations for screening |

| Chemical Libraries | FDA-approved drugs, natural product libraries, diversity-oriented synthesis compounds | Source of chemical perturbations for profiling |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Enables barcode sequencing and fitness quantification |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CG-TARGET, DeepVariant, Nextflow pipelines | Analyzes NGS data and predicts functional associations |

| Cell Culture Systems | Synthetic genetic array (SGA), TREC, robotic pinning tools | Enables high-throughput manipulation of mutant collections |

Table 2: Essential research reagents for chemical-genetic interaction studies.

Protocol: Genome-Wide Chemical-Genetic Interaction Screening in Yeast

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for systematic CGI profiling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using NGS-enabled pooled fitness assays.

Library Preparation and Compound Treatment

Materials:

- Yeast knockout deletion collection (

4,800 homozygous diploid mutants~6,000 viable haploid mutants) - Compound of interest dissolved in appropriate vehicle (DMSO typically <1%)

- YPD growth medium and 96-well deep-well plates

- DNA barcodes unique to each mutant strain

Procedure:

- Pool Preparation: Combine equal volumes of all mutant strains from the deletion collection into a single pooled culture. Grow overnight to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5-0.8) in rich medium.

- Compound Treatment: Divide the pooled culture into two aliquots. Add compound to treatment condition and vehicle only to control condition. Use multiple concentrations around IC50 when possible.

- Competitive Growth: Incubate cultures with shaking for 12-16 generations to allow fitness differences to manifest. Maintain cultures in mid-log phase through periodic dilution.

- Sample Collection: Harvest approximately 10^8 cells from both treatment and control conditions at multiple time points for time-resolved fitness measurements.

Genomic DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification

Materials:

- Zymolyase or lyticase for cell wall digestion

- Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and ethanol for DNA precipitation

- Uptag and Dntag specific primers with Illumina adapter sequences

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase for PCR amplification

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Digest cell walls with lytic enzymes followed by SDS/proteinase K treatment for complete lysis.

- DNA Purification: Extract genomic DNA using standard phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Quantify DNA concentration by fluorometry.

- Barcode Amplification: Perform two separate PCR reactions for uptag and dntag barcodes using 1μg genomic DNA as template. Use 18-22 cycles to maintain linear amplification range.

- Library Pooling: Combine uptag and dntag amplifications in equimolar ratios. Purify using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads.

NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing

Materials:

- Illumina platform-specific adapters with dual indices

- Size selection beads (AMPure XP or equivalent)

- Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit for quantification

- Illumina sequencing platform (NovaSeq X preferred for high throughput)

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Fragment amplified barcode pools to ~300bp and add Illumina sequencing adapters with dual indexing using commercial library preparation kits.

- Quality Control: Validate library fragment size distribution using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation. Quantify by qPCR for accurate cluster generation.

- Sequencing: Pool multiple libraries and sequence on Illumina platform using 75bp single-end reads. Aim for minimum coverage of 200-500 reads per barcode.

- Demultiplexing: Separate sequencing reads by sample index using Illumina bcl2fastq or similar tools.

Bioinformatics Analysis and Interaction Scoring

Materials:

- High-performance computing cluster with ≥16GB RAM

- Barcode-to-mutant mapping file for reference strain collection

- Bioinformatics pipelines (CG-TARGET, established Python/R scripts)

Procedure:

- Sequence Alignment: Map sequencing reads to barcode reference file using exact matching allowing 1-2 mismatches.

- Fitness Calculation: For each mutant, calculate relative abundance in treatment versus control using normalized read counts: Fitness = log2(treatmentreads/controlreads).

- Interaction Scoring: Compute chemical-genetic interaction score (ε) using the equation: ε = WtreatmentAB - (WtreatmentA × WtreatmentB) where W represents fitness values.

- Statistical Analysis: Identify significant interactions using z-score transformation or false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Functional Genomics

CGI mapping provides multifaceted insights that accelerate therapeutic development and functional annotation of genes.

Mode-of-Action Elucidation

Chemical-genetic profiles serve as functional fingerprints that can be compared to reference compounds with known targets through "guilt-by-association" approaches [21]. Machine learning algorithms, including Random Forest and Naïve Bayesian classifiers, have demonstrated strong predictive power for identifying cellular targets based on CGI profiles [26]. For example, CG-TARGET integration of genetic interaction networks with CGI data enabled high-confidence biological process predictions for over 1,500 compounds [22].

Synergistic Combination Prediction

CGI data provides a rational framework for identifying synergistic drug combinations that enhance efficacy while reducing resistance development. Studies have successfully leveraged CGI matrices to predict compound pairs that exhibit species-selective toxicity against human fungal pathogens [26]. The conceptual relationship between genetic and chemical interaction networks for synergy prediction is illustrated below:

Figure 2: Rational prediction of synergistic drug combinations based on synthetic lethal genetic interactions.

Resistance Mechanism Mapping

CGI profiling comprehensively identifies genes involved in drug uptake, efflux, and detoxification—revealing both known and novel resistance determinants [21]. Studies in E. coli have identified dozens of genes with pleiotropic roles in multidrug resistance, highlighting the extensive capacity for intrinsic antibiotic resistance in microbial populations [21]. This knowledge enables predictive models of resistance evolution and strategies to counteract resistance through adjuvant combinations.

Integration with Multi-Omics Technologies

The power of CGI mapping multiplies when integrated with complementary functional genomics approaches:

- Transcriptomic Integration: Correlation with gene expression signatures refines MoA predictions

- Proteomic Overlay: Identifies post-translational regulatory mechanisms

- Structural Bioinformatics: Enables rational design of optimized compounds

- CRISPR Screening Platforms: Extends CGI approaches to mammalian systems

Advanced integration methods like CG-TARGET successfully combine large-scale CGI data with genetic interaction networks to predict biological processes perturbed by compounds with controlled false discovery rates [22].

Chemical-genetic interaction mapping has evolved from a specialized genetic technique to a comprehensive systems biology platform, largely enabled by NGS technologies. The continued advancement of sequencing platforms—with Illumina's NovaSeq X series now capable of sequencing over 20,000 genomes annually at approximately $200 per genome—promises to further democratize and scale CGI profiling [27]. As these technologies converge with artificial intelligence and automated phenotyping, CGI mapping will play an increasingly central role in functional genomics, drug discovery, and personalized medicine, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies against human diseases.

Building the Pipeline: High-Throughput NGS Workflows for Interaction Mapping

In high-throughput chemical genetic interaction mapping, the ability to systematically screen thousands of compounds against genomic libraries demands precision, reproducibility, and scalability. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool in this field, enabling researchers to decipher complex gene-compound interactions at an unprecedented scale. A typical NGS workflow involves four critical steps: sample preparation, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [28]. Library preparation, which converts nucleic acids into a sequence-ready format, is particularly crucial as it establishes the foundation for reliable sequencing data [28]. This multi-step process includes DNA fragmentation, adapter ligation, PCR amplification, purification, quantification, and normalization, requiring meticulous attention to detail and precise liquid handling [28].

Manual library preparation methods present significant limitations for large-scale chemical genetic screens, being time-inefficient, labor-intensive, and constrained by limited throughput [28]. Furthermore, manual pipetting is prone to errors, especially when working with small volumes, leading to inconsistent results and challenges in reaction miniaturization [28]. Automated liquid handling systems effectively address these challenges by providing precise and consistent dispensing for complex protocols, particularly for small volumes, thereby reducing processing costs through miniaturization and enhancing reproducibility [28]. For drug development professionals seeking to map chemical-genetic interactions on a large scale, automation is not merely a convenience but a necessity for generating high-quality, statistically powerful datasets.

Key Concepts and Definitions

The Role of Assay Miniaturization in High-Throughput Screening

Assay miniaturization involves scaling down reaction volumes while maintaining accuracy and precision [29]. In the context of NGS library preparation for chemical genetics, this translates to performing reactions in volumes as low as hundreds of nanoliters [28]. The advantages are multifold:

- Cost Reduction: Miniaturization significantly decreases consumption of expensive reagents and precious compounds, making large-scale screening campaigns economically feasible [29]. For example, using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cells that can cost over $1,000 per vial of 2 million cells, moving from a 96-well to a 384-well format reduces cell consumption approximately fivefold, resulting in substantial savings [30].

- Enhanced Efficiency: Smaller volumes allow for higher well densities (e.g., 384-well or 1536-well plates), amplifying testing scale and efficiency within the same laboratory footprint [29].

- Improved Data Quality: Miniaturization can concentrate targets and reduce diffusion distances, potentially enhancing assay sensitivity and precision [29].

Automated Liquid Handling Technologies

Automated liquid handling (ALH) systems are engineered to deliver precise liquid transfers, enabling both miniaturization and process standardization. These systems generally fall into two categories:

- Non-Contact Dispensers: Instruments like the Mantis and Tempest use patented microfluidic technology to dispense sub-microliter volumes with high precision without tips, minimizing consumable costs and cross-contamination risks [28].

- Liquid Handlers with Tips: Systems such as the F.A.S.T. (96-channel, positive displacement) and FLO i8 PD (8-channel independent spanning, air displacement) are versatile for various volume ranges and protocol steps [28].

The integration of these systems into laboratory workflows is facilitated by features like CSV format file compatibility for sample pooling, normalization, and serial dilution, as well as Application Programming Interfaces (API) for seamless laboratory automation integration [28].

Application Note: Implementing Automated NGS for Compound Screening

Experimental Design for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Mapping

In a typical chemical-genetic interaction mapping study, the goal is to identify how different chemical compounds affect various genetic mutants. The experimental design involves treating an array of yeast deletion mutants or CRISPR-modified human cell lines with a library of compounds, followed by NGS-based readout of mutant abundance to identify genetic sensitivities and resistances.

Key design considerations include:

- Library Complexity: The number of unique barcodes must match the genetic library size, often exceeding 10,000 unique mutants.

- Replication: Appropriate biological and technical replicates are crucial for statistical power in identifying significant interactions.

- Controls: Including untreated controls and reference compounds with known mechanisms is essential for data normalization and quality control.

Automation enables this complex experimental design by ensuring consistent liquid handling across hundreds of plates, precise compound dispensing at nanoliter scales, and reproducible library preparation for accurate sequencing results.

Automated Protocol for NGS Library Preparation from Treated Cell Pools

Table 1: Automated NGS Library Preparation Workflow for Chemical-Genetic Screens

| Step | Process | Automated System | Key Parameters | Volume Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Genomic DNA Extraction | Agilent Bravo (96 channels) or Biomek NXp (8-channel) | Input: 1-5 million cells; Elution Volume: 50-100 μL | 50-200 μL |

| 2 | DNA Fragmentation | Focused-ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris LE220) | Target size: 550 bp; Sample Distribution: Automated transfer to microTUBE plates | 50-100 μL |

| 3 | Library Construction | Agilent Bravo, MGI SP-960, or Hamilton NGS STAR | PCR-free or with limited-cycle PCR; Adapter Ligation | 20-50 μL |

| 4 | Library Purification | Magnetic bead-based cleanup on liquid handler | Bead-to-sample ratio: 1.0-1.8X; Elution Volume: 15-30 μL | 15-100 μL |

| 5 | Quality Control | Fragment Analyzer or TapeStation | Size distribution: 300-700 bp; Concentration: ≥ 2 nM | 1-5 μL |

| 6 | Library Normalization & Pooling | Hamilton, Formulatrix FLO i8, or Beckman Biomek i7 | Normalization to 2-4 nM; Equal volume pooling | 5-20 μL |

| 7 | Quantification for Sequencing | qPCR systems (e.g., qMiSeq) | Loading concentration optimization | 2-5 μL |

This protocol, adapted from large-scale sequencing projects [31], can process 96-384 samples in parallel with minimal hands-on time, enabling rapid screening of compound libraries.

Technical Specifications of Automated Liquid Handling Systems

Table 2: Comparison of Automated Liquid Handling Systems for NGS Library Prep

| System | Technology | Precision | Miniaturization Range | Throughput Capacity | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulatrix Mantis | Non-contact, tipless dispenser | <2% CV at 100 nL | Down to 100 nL | Plates up to 1536 wells; Up to 48 reagents | CSV input, backfill, concentration normalization |

| Formulatrix Tempest | Non-contact, tipless dispenser | <5% CV at 200 nL | Down to 200 nL | Plates up to 1536 wells; 24 plate stacking | 96 nozzles; Serial dilution, pooling, broadcasting |

| Formulatrix F.A.S.T. | 96-channel, positive displacement | <5% CV at 100 nL | Down to 100 nL transfer | Plates up to 384 wells; 6 on-deck positions | Flow Axial Seal Tip technology |

| Formulatrix FLO i8 PD | 8-channel, air displacement | <5% CV at 1 μL | Down to 500 nL transfer | Plates up to 384 wells; 10 on-deck positions | Independent spanning channels; Integrated flow rate sensors |

| Agilent Bravo | 96-channel, adaptable | Protocol-dependent | Down to 1 μL | Plates up to 384 wells | Used with TruSeq DNA PCR-free kits [31] |

| Hamilton NGS STAR | 96-channel or 8-channel | Protocol-dependent | Down to 1 μL | Plates up to 384 wells | Compatible with Illumina DNA Prep [32] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Automated NGS

Table 3: Essential Materials for Automated NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products | Automation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-Free Library Prep Kit | Creates sequencing libraries without PCR bias | Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free HT, MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set [31] | Compatibility with automated platforms; Dead volume requirements |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Multiplexing samples in sequencing runs | IDT for Illumina TruSeq DNA Unique Dual indexes [31] | Plate-based formatting for automated liquid handlers |

| Magnetic Beads | Library purification and size selection | SPRIselect, AMPure XP | Viscosity and behavior in automated protocols |

| DNA Quantitation Kits | Accurate library quantification | Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [31] | Compatibility with automated plate readers |

- Library Preparation Kits: Specialized for automation with reduced dead volumes and pre-formatted reagents.

- Magnetic Beads: Engineered for consistent binding kinetics in small-volume reactions.

- Indexing Primers: Pre-arrayed in plates compatible with automated liquid handlers.

Methods and Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Miniaturized NGS Library Preparation on Automated Systems

Procedure for 384-Well Library Preparation Using PCR-Free Methods

DNA Normalization and Plate Reformatting

- Program the liquid handler (e.g., Biomek NXp) to transfer genomic DNA samples from source plates to a 384-well assay plate, normalizing all samples to 10-20 ng/μL in 50 μL volume using low-EDTA TE buffer [31].

- Centrifuge the plate briefly (1000 × g, 1 minute) to collect liquid at the bottom of wells.

Automated DNA Fragmentation

Library Assembly on Liquid Handler

- Program the system (e.g., Agilent Bravo with 96-channel head) to add:

- 25 μL of fragmented DNA

- 10 μL of End Repair Mix

- 5 μL of Ligation Mix

- 5 μL of Appropriate Adapters with Unique Dual Indexes [31]

- Use the instrument's mixing function to ensure complete homogenization without bubble formation.

- Program the system (e.g., Agilent Bravo with 96-channel head) to add:

Library Purification

- Perform a two-sided size selection using magnetic beads at 0.5X and 0.8X ratios to remove short fragments and adapter dimers.

- Program the liquid handler to:

- Add magnetic beads to each well

- Incubate for 5 minutes

- Engage magnets and wait for solution clarification

- Remove and discard supernatant

- Perform two 80% ethanol washes

- Elute in 25 μL of Resuspension Buffer [31]

Quality Control and Quantification

Library Normalization and Pooling

- Calculate normalization volumes based on QC data.

- Program the liquid handler to transfer calculated volumes of each library to a pooling reservoir.

- Mix the pool thoroughly and transfer to a fresh tube for sequencing.

Protocol: Miniaturized Compound Addition for Chemical Treatment

Procedure for 1536-Well Compound Screening Prior to NGS

Compound Plate Preparation

- Reform compound libraries into 1536-well source plates at appropriate concentrations (typically 1-10 mM in DMSO) using acoustic dispensers or pintool transfer.

- Include control compounds in designated wells.

Miniaturized Compound Transfer

- Using a non-contact dispenser (e.g., Formulatrix Mantis), transfer 20 nL of compound from source plates to 1536-well assay plates containing cells in 2 μL culture medium.

- This results in final compound concentrations of 10-100 μM.

Incubation and Processing

- Incubate plates under appropriate conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) for the desired treatment period (typically 24-72 hours).

- Process cells for genomic DNA extraction using miniaturized protocols compatible with high-density plates.

Workflow Visualization: Automated NGS Library Preparation

Figure 1: Automated NGS workflow for chemical genetic screens.

System Architecture: Integration of Automation Components

Figure 2: Integration of automation components in NGS workflow.

Results and Discussion

Performance Metrics for Automated NGS Library Preparation

Implementation of automated liquid handling and assay miniaturization in NGS library preparation yields significant improvements in key performance metrics:

- Process Efficiency: Automated systems reduce hands-on time by 50-65% compared to manual methods [32]. For example, the Illumina DNA Prep with Enrichment automated on Hamilton or Beckman systems processes up to 48 DNA libraries with over 65% less hands-on time [32].

- Cost Reduction: Miniaturization of Nextera XT library preparation using the Mantis liquid dispenser demonstrates 75% savings on reagent costs while maintaining high-quality RNA-seq libraries from low-input murine neuronal cells [28].

- Data Quality: Automated systems maintain or improve data quality metrics. The Formulatrix F.A.S.T. instrument enables precise plate-to-plate transfers of single microliter volumes of single cell cDNA, efficiently combining 384 unique indexing primers from separate plates while mitigating evaporation risk [28].

- Reproducibility: Automated liquid handling significantly reduces well-to-well variability, with precision metrics of <2% coefficient of variation (CV) at 100 nL for advanced systems like the Mantis [28].

Addressing Challenges in Miniaturization and Automation

Despite the clear benefits, implementing automated, miniaturized NGS workflows presents challenges that require strategic solutions:

- Evaporation Management: Smaller volumes are more susceptible to evaporation, particularly in edge wells. Strategies to mitigate this include using plate seals, maintaining high humidity in automated environments, and employing non-contact dispensers that minimize well-open time [28] [30].

- Liquid Handling Precision: Transferring nanoliter volumes demands specialized instrumentation. Positive displacement systems and microfluidic-based non-contact dispensers provide the required precision for miniaturized reactions [28].

- Reagent Compatibility: Some reagents may exhibit different behavior in miniaturized formats, requiring optimization of concentrations, incubation times, and mixing parameters.

- Cross-Contamination Risks: As well density increases, the potential for cross-contamination grows. Regular maintenance, proper tip washing protocols, and non-contact dispensing where appropriate minimize this risk.

Future Directions in Automated NGS for Chemical Genetics

The field of automated NGS continues to evolve, with several trends shaping its application in chemical genetic interaction mapping:

- Integration with Multiomics Approaches: Future workflows will likely incorporate simultaneous analysis of genetic interactions with transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic changes from the same samples, enabled by automated systems capable of processing multiple analyte types [33].

- AI-Enhanced Experimental Design and Analysis: Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly being applied to optimize screening parameters, predict interactions, and analyze complex datasets [33].

- Further Miniaturization: Ongoing developments in microfluidics and nanodispensing technologies promise continued reduction in reaction volumes, potentially enabling high-density formats beyond 1536-well plates for ultra-high-throughput applications [29].

- Real-Time Process Monitoring: Integration of sensors and real-time quality control checks within automated workflows will enhance process control and reduce failure rates.

For research teams engaged in high-throughput chemical genetic interaction mapping, the strategic implementation of automated liquid handling and assay miniaturization represents a critical capability for scaling screening efforts without compromising data quality or operational efficiency.

The advent of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has revolutionized functional genomics, providing an unparalleled toolkit for high-throughput interrogation of gene function. When integrated with Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), CRISPR-based screens transform genetic mapping from a correlative to a causal science, enabling the systematic deconvolution of complex chemical-genetic interaction networks [34] [35]. This synergy allows researchers to not only identify genes essential for cell viability under specific chemical treatments but also to map entire genetic interaction networks that define drug mechanisms of action and resistance pathways [36]. For drug development professionals, this integrated approach provides a powerful platform for target identification, validation, and mechanism-of-action studies, ultimately accelerating therapeutic discovery.

Experimental Design: Core CRISPR Screening Modalities

The power of CRISPR functional genomics lies in its adaptability. Three primary screening modalities enable either loss-of-function (LOF) or gain-of-function (GOF) studies at scale, each with distinct advantages for specific biological questions.

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko)

Mechanism: Utilizes the wild-type Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the target DNA. These breaks are repaired by the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the coding sequence and create gene knockouts [36] [37].

Applications: Identification of essential genes, fitness genes under specific conditions (e.g., drug treatment), and genes involved in pathways governing cellular responses [35].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi)

Mechanism: Employs a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a transcriptional repressor domain, such as the KRAB domain. The dCas9-KRAB complex binds to the promoter or transcriptional start site of a target gene without cutting the DNA, leading to targeted epigenetic silencing and reduced gene expression [36].

Applications: Tunable and reversible gene suppression; ideal for studying essential genes where complete knockout is lethal, and for functional characterization of non-coding regulatory elements [36].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa)

Mechanism: Uses dCas9 fused to strong transcriptional activation domains, such as the VP64-p65-Rta (VPR) or Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) systems. This complex is guided to the promoter regions of target genes to recruit transcriptional machinery and enhance gene expression [36].

Applications: Gain-of-function screens to identify genes that confer resistance to therapeutics, drive cell differentiation, or overcome pathological states.

Table 1: Comparison of Core CRISPR Screening Modalities

| Screening Modality | Core Mechanism | Genetic Outcome | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko (Knockout) | Cas9-induced DSB + NHEJ repair | Gene disruption/Loss-of-function | Essential gene discovery, drug-gene interactions, fitness screens [36] [35] |

| CRISPRi (Interference) | dCas9 fused to repressor (e.g., KRAB) | Transcriptional repression/Loss-of-function | Studies of essential genes, non-coding regulatory elements [36] |

| CRISPRa (Activation) | dCas9 fused to activators (e.g., VPR, SAM) | Transcriptional activation/Gain-of-function | Gene suppressor screens, identification of resistance mechanisms [36] |

Detailed Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Pooled CRISPRko Screen for Chemical-Genetic Interactions

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying genes that modulate cellular sensitivity to a small molecule compound, a cornerstone of high-throughput chemical genetic interaction mapping [35].

Step 1: Library Design and Selection

- Select a genome-scale or focused sgRNA library (e.g., Brunello, GeCKO).

- Ensure coverage of 3-6 sgRNAs per gene and include non-targeting control sgRNAs.

- Amplify the library plasmid DNA and prepare high-titer lentiviral stock.

Step 2: Cell Transduction and Selection

- Transduce the target cell population (e.g., HAP1, haploid cells) at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA.

- Forty-eight hours post-transduction, select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., Puromycin) for 5-7 days to generate a stable mutant pool.

Step 3: Application of Chemical Challenge

- Split the selected cell pool into two groups: Treatment and Control.

- Treat the Treatment arm with the IC20-IC30 concentration of the compound of interest.

- Culture the Control arm with the compound's vehicle (e.g., DMSO).

- Maintain cultures for 14-21 days, allowing for 10-12 population doublings to enable phenotypic manifestation.

Step 4: Sample Preparation and NGS

- Harvest a minimum of 1,000 cells per sgRNA in the library at both T0 (baseline) and Tfinal (post-treatment/control) time points.

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences using primers containing Illumina adapters and sample barcodes.

- Pool PCR products and perform NGS on an Illumina platform to a depth of 200-500 reads per sgRNA.

Step 5: Data Analysis and Hit Calling

- Process raw FASTQ files to count sgRNA reads for each sample using tools like

MAGeCK count[36]. - Normalize read counts and identify differentially enriched or depleted sgRNAs between Treatment and Control groups using robust statistical models (e.g.,

MAGeCK test). - Aggregate sgRNA-level effects to gene-level scores. Genes whose sgRNAs are significantly depleted in the Treatment arm are "sensitizers" (loss enhances drug effect), while those enriched are "resistors" (loss confers resistance) [36].

Protocol: High-Content Screening with Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (Perturb-Seq)

This advanced protocol couples genetic perturbations with deep phenotypic profiling, enabling the dissection of transcriptional networks and heterogeneous cellular responses at single-cell resolution [36] [35].

Step 1: Library Transduction and Preparation

- Transduce cells with a pooled CRISPRko/i/a library as in Protocol 3.1, but at a higher MOI to ensure widespread perturbation.

- After selection, subject the entire pool of perturbed cells to single-cell RNA sequencing (e.g., using the 10x Genomics platform).

Step 2: Single-Cell Library Construction and Sequencing

- Prepare a single-cell suspension and partition cells into nanoliter droplets along with barcoded beads.

- Generate barcoded cDNA libraries where the transcriptome of each cell is tagged with a unique cellular barcode.

- Include a custom pre-amplification step to also capture and barcode the expressed sgRNAs from each cell.

Step 3: Data Integration and Analysis

- Align sequencing reads to the reference genome and assign transcripts to individual cells using cellular barcodes.

- Demultiplex the perturbations by matching the captured sgRNA sequences to the library manifest.

- Use computational tools like

MIMOSCAorscMAGeCKto regress the single-cell transcriptional profile of each cell against its genetic perturbation [36]. - Identify differentially expressed genes and pathways resulting from each knockout, building a high-resolution map from genetic perturbation to transcriptional outcome.

Advanced Tools: Precision Genome Editing for Variant Functionalization

Beyond gene-level knockout, newer CRISPR-derived technologies enable precise nucleotide-level editing, allowing for the functional characterization of human genetic variants discovered through NGS.

Base Editing

Mechanism: Uses a Cas9 nickase (nCas9) or dCas9 fused to a deaminase enzyme. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert a C•G base pair to T•A, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert an A•T base pair to G•C, all without inducing a DSB [34] [37].

Application in Functional Genomics: Saturation mutagenesis of specific codons to assay the functional impact of all possible single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in a gene region of interest.

Prime Editing

Mechanism: Employs a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase (PE2 system), programmed with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The pegRNA both specifies the target site and contains the desired edit template. The system nicks the target strand and directly "writes" the new genetic information from the pegRNA template into the genome [34] [38].

Application in Functional Genomics: A recent study demonstrated the power of pooled prime editing to screen over 7,500 pegRNAs targeting tumor suppressor genes like SMARCB1 and MLH1 in HAP1 cells. This approach enabled high-throughput saturation mutagenesis to identify pathogenic loss-of-function variants in both coding and non-coding regions, providing a robust platform for classifying variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified by clinical NGS [38].

Table 2: Advanced CRISPR-Based Editors for Variant Study

| Editor Type | Key Components | Type of Changes | Advantages for NGS Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosine Base Editor (CBE) | nCas9/dCas9 + Cytidine Deaminase | C•G to T•A | Clean, efficient installation of specific transition mutations without DSBs [34] |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | nCas9/dCas9 + Adenine Deaminase | A•T to G•C | Installs precise A-to-G changes with minimal indel formation [34] |

| Prime Editor (PE) | nCas9 + Reverse Transcriptase + pegRNA | All 12 base-to-base conversions, small insertions/deletions | Unprecedented precision and versatility for modeling human SNVs and indels [38] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nucleases | Engineered variants of the Cas9 protein (from S. pyogenes and other species) with different PAM specificities and off-target profiles. | CRISPRko screens; foundation for engineering base and prime editors [37]. |

| dCas9 Effector Fusions | Catalytically inactive Cas9 fused to transcriptional repressors (KRAB for CRISPRi) or activators (VPR/SAM for CRISPRa). | Transcriptional modulation screens; epigenetic editing [36]. |

| Base Editors (BE) | Fusion proteins of nCas9/dCas9 with deaminase enzymes (e.g., BE4 for C->T; ABE8e for A->G). | High-throughput saturation mutagenesis to model SNVs [34] [37]. |

| Prime Editors (PE) | nCas9-reverse transcriptase fusions programmed with pegRNAs. | Installation of precise variants (SNVs, indels) for functional characterization of VUS [38]. |

| sgRNA Libraries | Pooled, barcoded collections of thousands of sgRNAs targeting genes genome-wide or in specific pathways. | Pooled knockout, interference, and activation screens [35]. |

| pegRNA Libraries | Pooled libraries of prime editing guide RNAs designed to install specific variants via prime editing. | Multiplexed Assays of Variant Effect (MAVEs) in the endogenous genomic context [38]. |

| Analysis Software (MAGeCK) | A widely used computational workflow for the robust identification of positively and negatively selected genes from CRISPR screen NGS data. | Statistical analysis of screen results to identify hit genes [36]. |

Enzyme-Coupled Assay Systems and Readout Cascades for Phenotypic Screening

Enzyme-coupled assay systems represent a sophisticated and versatile toolset for phenotypic screening, a drug discovery strategy that has experienced a major resurgence in the past decade. Modern phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) focuses on modulating disease phenotypes or biomarkers rather than pre-specified molecular targets, and has contributed to a disproportionate number of first-in-class medicines [39]. These screens require robust, sensitive readout systems capable of detecting subtle phenotypic changes in realistic disease models. Enzyme-coupled assays fulfill this need by translating molecular events into measurable signals through cascading biochemical reactions, thereby enabling researchers to monitor complex biological processes in high-throughput screening (HTS) environments.

The fundamental principle underlying enzyme-coupled assays involves linking a primary enzymatic reaction of interest to one or more auxiliary enzyme reactions that generate a detectable output signal, typically through absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence readouts [40]. This signal amplification strategy is particularly valuable for monitoring enzymatic activities where products are not easily measured by available instruments at high-throughput. Within the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for chemical-genetic interaction mapping, these assay systems provide the phenotypic data that, when correlated with genetic perturbation information, enables the comprehensive reconstruction of regulatory circuits and drug mechanisms of action [41].

Theoretical Foundations of Enzyme-Coupled Assay Systems

Basic Principles and Kinetic Considerations