Library Preparation for Chemogenomic Screens: A Guide to CRISPR Workflows, Optimization, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to library preparation for chemogenomic CRISPR screens, a cornerstone of modern functional genomics and drug discovery.

Library Preparation for Chemogenomic Screens: A Guide to CRISPR Workflows, Optimization, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to library preparation for chemogenomic CRISPR screens, a cornerstone of modern functional genomics and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from sgRNA library design to the latest screening modalities like CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa. The content delves into methodological workflows for both pooled and arrayed screens, offers expert troubleshooting for common preparation and sequencing issues, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to empower scientists to design and execute robust, high-quality chemogenomic screens that yield reliable, actionable biological insights.

Core Concepts and Screening Modalities in Chemogenomics

Defining Chemogenomic Screens and Their Role in Target Identification

Chemogenomic screens represent a powerful functional genomics approach that systematically explores the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems to identify molecular targets. These screens combine large-scale genetic or chemical perturbations with phenotypic readouts to deconvolute the mechanisms of action (MoA) of bioactive molecules and identify novel therapeutic targets [1]. Within the drug discovery pipeline, they serve as a critical bridge between initial compound screening and target validation, addressing the significant challenge of identifying the protein target of a small molecule, particularly those discovered in phenotypic screens [2] [1].

The core principle involves screening comprehensive libraries of genetically perturbed cells (e.g., via CRISPR) or chemical compounds against a diverse set of chemical or genetic perturbations to generate rich, multidimensional datasets. These datasets reveal how different cellular states or genetic backgrounds alter compound sensitivity, providing functional clues about target pathways and disease biology [3]. This approach has been widely adopted by pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies because it accelerates the identification of potent and selective compounds for a chosen target and helps explore whether target modulation will lead to mechanism-based side effects [2].

Key Screening Approaches and Methodologies

Chemogenomic screens can be broadly categorized into two main paradigms: forward chemogenomics, which starts with a biological phenotype to identify the responsible gene or target, and reverse chemogenomics, which begins with a specific target or gene to find modulating compounds [2]. The choice between these approaches depends on the starting point of the research and the underlying biological question.

Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

- Phenotypic Screening: This approach tests compounds in disease-relevant models to identify small molecule hits that modulate a desired phenotype without presupposing a specific molecular target. It is powerful for discovering novel biology when a strong chain of translatability is available [2] [4]. A key challenge is that the target of the hit molecule is often unknown, requiring additional deconvolution through methods like chemical proteomics [2].

- Target-Based Screening: This hypothesis-driven approach focuses on identifying potent and selective compounds for a pre-defined molecular target. It leverages rational drug design and has been widely adopted in the pharmaceutical industry [2].

Modern chemogenomic screens often integrate elements of both approaches, using phenotypic readouts to identify biologically active compounds while employing systematic genetic perturbations to hypothesize about potential targets [1].

Essential Screening Technologies

CRISPR-Based Functional Genomics

CRISPR-based screens enable systematic interrogation of gene function across the entire genome. The following table summarizes key CRISPR screening methodologies:

Table 1: Key CRISPR Screening Methodologies for Target Identification

| Method | Mechanism | Application in Target ID | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout (CRISPRko) | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), resulting in gene knockouts [3]. | Identification of genes that suppress or enhance compound sensitivity [3]. | Direct measurement of gene essentiality; comprehensive coverage. |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | Uses catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressors (e.g., KRAB) to silence gene expression without DNA cleavage [5]. | Probing essential genes without triggering p53-mediated toxicity; suitable for sensitive cell types like stem cells [5]. | Avoids DNA damage response; enables screening in pluripotent stem cells. |

| CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) | Employs dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators to overexpress genes [5]. | Identifying genes that confer resistance when overexpressed. | Complements knockout screens; reveals dosage-sensitive interactions. |

The protocol for a phenotypic CRISPR screen typically involves:

- Library Selection: Choosing a sgRNA library (e.g., TKOv3, genome-wide) targeting genes of interest [3].

- Cell Line Engineering: Generating Cas9-expressing cell lines, often with TP53 knockout to prevent confounding effects of p53 activation by genotoxic stress [3].

- Viral Transduction: Delivering sgRNA libraries at low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure single sgRNA incorporation per cell [5].

- Phenotypic Selection: Applying selection pressure (e.g., compound treatment) and sorting cells based on phenotypic readouts [3].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Isolating genomic DNA, amplifying sgRNA cassettes, and sequencing to quantify sgRNA abundance changes using tools like MAGeCK [3].

High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening

Modern phenotypic screening leverages high-content technologies to capture subtle, disease-relevant phenotypes at scale [4]. Key advancements include:

- High-Content Imaging and Cell Painting: Uses fluorescent dyes to visualize multiple cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles that can be processed with AI/ML algorithms like PhenAID to identify phenotypic patterns correlating with mechanism of action [4].

- Flow Cytometry-Based Readouts: Enables quantitative measurement of specific markers like γ-H2AX for DNA damage [3] or eGFP to BFP conversion for measuring gene editing outcomes [6].

- Pooled Perturbation Screens with Computational Deconvolution: Allows testing of multiple perturbations in a single sample, dramatically reducing sample size, labor, and cost while maintaining information-rich outputs [4].

Chemogenomics in Target Identification and Validation

From Phenotypic Hits to Molecular Targets

When a compound shows efficacy in a phenotypic screen, the critical next step is identifying its molecular target(s). Several chemical proteomics approaches have been developed for this purpose:

- Affinity Chromatography: Immobilizing a chemical probe on a solid phase to fish for unknown protein targets in a complex mixture. Proteins with affinity for the probe are retained, eluted, and identified through proteomics technologies [2].

- Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): Uses active-site-directed covalent probes to profile the functional states of enzymes in complex proteomes. ABPs can distinguish active enzymes from their inactive states or inhibitor-bound forms and typically contain a reactive group and a reporter tag (e.g., biotin) for detection and identification [2].

- Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL): Incorporates a photoreactive group into the probe which, upon UV irradiation, forms a highly reactive intermediate that covalently binds to nearby proteins. This allows temporal control of labeling events and identification of protein-ligand interactions [2].

Table 2: Chemical Proteomics Methods for Target Deconvolution

| Method | Mechanism | Covalent Binding | Temporal Control | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography | Probe immobilization on solid support [2]. | No | No | Fishing for targets in complex mixtures. |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Reactive group targets enzyme active sites [2]. | Yes | No | Profiling enzyme activity states; distinguishing active/inactive enzymes. |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Photoreactive group activated by UV light [2]. | Yes | Yes | Studying protein-ligand interactions; identifying unknown targets. |

Case Study: DNA Damage Suppressor Screening

Zhao et al. (2023) exemplify the power of phenotypic chemogenomic screens by conducting flow cytometry-based CRISPR/Cas9 screens monitoring γ-H2AX levels to identify genes suppressing DNA damage [3]. Their experimental workflow included:

- Cell Line Selection: Using RKO colon carcinoma and COL-hTERT immortalized colon epithelial cells, both with TP53 knockout to prevent confounding p53 activation [3].

- Library Implementation: Employing the TKOv3 sgRNA library targeting essential and non-essential genes [3].

- Phenotypic Sorting: Sorting cells with the highest 5% γ-H2AX fluorescence intensity after treatment with replication-perturbing agents (aphidicolin, hydroxyurea, cytarabine) or without treatment [3].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Computing gene-level enrichment scores using MAGeCK to compare sgRNA abundance in sorted versus unsorted populations [3].

This screen identified 160 genes whose mutation caused spontaneous DNA damage, enriched for essential genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and iron-sulfur cluster metabolism. Notably, the approach successfully captured essential genes like components of the replicative CMG helicase (GINS1-4, MCM2-6) that were missed in previous fitness-based screens, demonstrating the method's unique ability to probe essential gene function in genome maintenance [3].

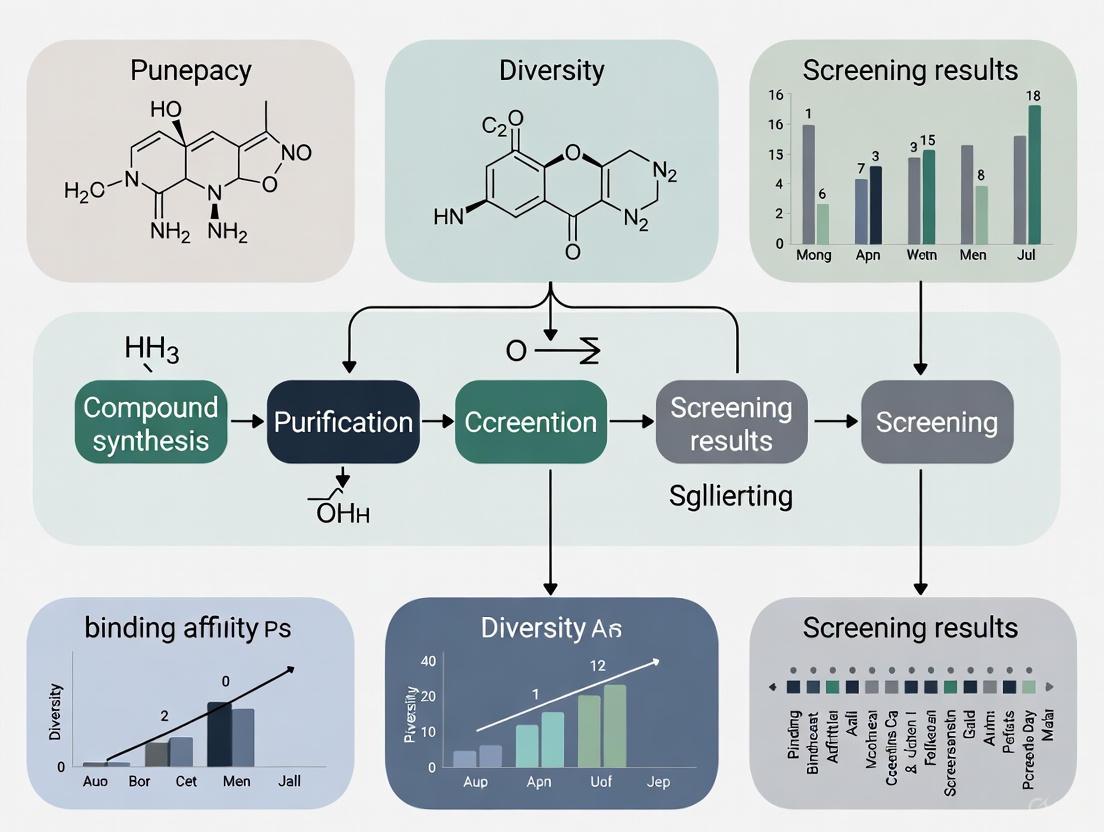

Diagram 1: DNA Damage Suppressor Screen

Implementation and Workflow Design

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful chemogenomic screens require careful planning of several key parameters:

- Library Design: The sgRNA library should provide sufficient coverage (typically 3-10 guides per gene) and include non-targeting control guides. Libraries like TKOv3 are optimized for improved on-target efficiency [3].

- Cell Model Selection: Choose physiologically relevant cell models. Inducible CRISPRi systems in hiPS cells and differentiated lineages (neural progenitor cells, neurons, cardiomyocytes) enable comparison across cellular contexts [5].

- Phenotypic Readout Selection: The readout must be quantitatively robust and biologically relevant. Examples include γ-H2AX for DNA damage [3], β-galactosidase activity for HDR efficiency [7], and fluorescent protein conversion for editing outcomes [6].

- Replication and Controls: Include sufficient biological replicates and controls (non-targeting guides, untreated samples) to ensure statistical power and minimize false discoveries.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemogenomic Screens

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Libraries | Enables systematic genetic perturbation [3]. | TKOv3, CRISPRi/v2 libraries; genome-wide or focused sets. |

| CRISPR Systems | Executes genetic perturbations [5] [3]. | Cas9, dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), base editors. |

| Cell Lines | Provides cellular context for screening [5] [3]. | RKO, HEK293, hiPS cells, and differentiated lineages. |

| Selection Agents | Maintains genetic elements in cells [5]. | Puromycin, blasticidin, hygromycin. |

| Chemical Probes | Target deconvolution for phenotypic hits [2]. | Affinity probes, ABPs, photoaffinity probes. |

| Detection Reagents | Enables phenotypic measurement [7] [3]. | γ-H2AX antibodies, β-galactosidase substrates (ONPG). |

Protocol: Flow Cytometry-Based CRISPR Screen for DNA Damage Suppressors

This protocol adapts the methodology from Zhao et al. (2023) for identifying genes that suppress DNA damage [3]:

Cell Line Preparation (Weeks 1-2):

- Generate Cas9-expressing RKO or COL-hTERT cell lines with TP53 knockout using CRISPR.

- Validate Cas9 activity and p53 knockout status through immunoblotting and functional assays.

Library Transduction (Week 3):

- Transduce cells with the TKOv3 lentiviral library at MOI of 0.3-0.4 to ensure most cells receive single sgRNAs.

- Add polybrene (8μg/mL) to enhance transduction efficiency.

- Select transduced cells with puromycin (1-2μg/mL) for 5-7 days.

Treatment and Sorting (Week 4):

- Split cells into treatment groups: untreated, aphidicolin (0.3μM), hydroxyurea (100μM), cytarabine (1μM).

- Culture for 14 days, maintaining library representation at 500x coverage.

- Harvest cells, fix in paraformaldehyde, and stain with anti-γ-H2AX antibody and fluorescent secondary antibody.

- Sort cells with highest 5% γ-H2AX fluorescence intensity using FACS.

Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing (Weeks 5-6):

- Extract genomic DNA from sorted and unsorted control cells using silica column-based kits.

- Amplify sgRNA cassettes via PCR with barcoded primers.

- Sequence amplified fragments on Illumina platform (minimum 50x coverage).

Bioinformatic Analysis (Week 7):

- Align sequences to reference sgRNA library.

- Calculate sgRNA abundance fold-changes between sorted and unsorted populations.

- Perform gene-level statistical analysis using MAGeCK to identify significantly enriched genes (FDR < 0.05).

Diagram 2: Target Deconvolution Workflow

Data Analysis and Integration

Bioinformatics Pipelines

Robust computational analysis is essential for interpreting chemogenomic screen data:

- Primary Screen Analysis: Tools like MAGeCK (Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout) calculate gene-level enrichment or depletion scores by comparing sgRNA abundance between experimental conditions and controls [3]. MAGeCK uses a negative binomial model to account for over-dispersion in sgRNA counts and employs robust ranking statistics (RRA) to identify essential genes.

- Hit Prioritization: Candidates are prioritized based on statistical significance (FDR < 0.05), effect size (log2 fold-change), and consistency across multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene. Integration with external datasets (DepMap, GO annotations) provides biological context [3].

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining chemogenomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets provides a systems-level view of biological mechanisms. AI/ML models can fuse these heterogeneous data sources to identify complex patterns and relationships [8] [4].

Validation Strategies

- Orthogonal Validation: Top hits require confirmation through orthogonal methods such as individual sgRNA validation, cDNA rescue experiments, and secondary phenotypic assays [5] [3].

- Target Engagement Assays: Techniques like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) quantify drug-target interactions directly in cells by measuring protein stability changes upon compound binding [1].

- Mechanistic Studies: Follow-up experiments including co-immunoprecipitation, enzymatic assays, and structural studies elucidate the precise molecular mechanism of compound action.

The field of chemogenomics is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends:

- AI-Powered Integration: Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming chemogenomics by enabling the integration of multimodal datasets (imaging, transcriptomics, proteomics) to predict mechanism of action, identify novel targets, and streamline the drug development pipeline [8] [4]. Platforms like Archetype AI and PhenAID demonstrate how AI can interpret complex phenotypic data to uncover new biology and therapeutic candidates [4].

- Single-Cell and Spatial Technologies: Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics allow deconvolution of heterogeneous cellular responses to perturbations, revealing cell-type-specific effects within complex models [8] [4].

- Advanced Cellular Models: The use of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPS) and their differentiated derivatives (neurons, cardiomyocytes) provides more physiologically relevant contexts for screening, overcoming limitations of cancer cell lines [5].

- High-Content Phenotypic Profiling: Technologies like Cell Painting combined with AI-based image analysis capture subtle morphological changes that provide deep insights into compound mechanism of action [4].

In conclusion, chemogenomic screens represent an indispensable approach in modern drug discovery, systematically linking chemical and genetic perturbations to phenotypic outcomes. When properly designed and executed, these screens effectively bridge the gap between phenotypic observations and molecular target identification, accelerating the development of novel therapeutics. As single-cell technologies, AI integration, and sophisticated cellular models continue to advance, chemogenomic approaches will play an increasingly central role in understanding complex biology and identifying druggable targets for therapeutic intervention.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based technologies have revolutionized functional genomics by enabling precise manipulation of gene function at scale. Within chemogenomic screening research—which explores gene-compound interactions to identify drug targets and mechanisms of action—three primary CRISPR modalities have become essential tools: CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko), CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa). Each system offers distinct mechanistic approaches to perturb gene function, allowing researchers to systematically investigate gene function and identify genetic determinants of drug sensitivity and resistance [9] [10].

CRISPRko utilizes the wild-type Cas9 nuclease to create permanent double-stranded breaks in DNA, resulting in frameshift mutations and complete gene knockout. In contrast, CRISPRi and CRISPRa employ catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to effector domains to reversibly modulate transcription without altering the underlying DNA sequence [9]. CRISPRi achieves transcriptional repression, while CRISPRa enables targeted gene activation [9] [11]. The selection of appropriate modality depends on the biological question, with CRISPRko suited for complete loss-of-function studies, CRISPRi for partial and reversible knockdown, and CRISPRa for gain-of-function investigations [9] [10].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Modalities

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, mechanisms, and applications of CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa, highlighting their distinct advantages in chemogenomic screens.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major CRISPR Modalities

| Feature | CRISPRko (Knockout) | CRISPRi (Interference) | CRISPRa (Activation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Type | Wild-type, nuclease-active Cas9 [9] | Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) [9] | Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) [9] |

| Core Mechanism | Creates double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs), leading to frameshift mutations and gene disruption via NHEJ [9] [11] | dCas9 fused to repressor domains (e.g., KRAB) blocks transcription or creates repressive chromatin [9] [10] | dCas9 fused to activator domains (e.g., VP64, p65, Rta) recruits transcriptional machinery [9] [10] |

| Effect on Gene | Permanent, complete loss-of-function (knockout) [9] | Reversible, partial to strong knockdown (knockdown) [9] | Overexpression (gain-of-function) [9] |

| Key Applications in Screens | Identifying essential genes [10], gene functions where complete ablation is needed [12] | Studying essential genes [9], mimicking drug action [9], toxic genes [13] | Identifying genes conferring resistance [10] [13], activating tumor suppressors [10], studying lowly expressed or non-coding genes [9] |

| Advantages | Strong, permanent phenotype; well-established [12] | Reversible; fewer off-target effects than RNAi; avoids DNA damage toxicity [9] [13] | Endogenous gene activation in native context; superior to ORF overexpression for large transcripts [9] |

| Limitations | Unsuitable for essential gene studies in knockout screens [9]; can cause DNA damage response toxicity [13] | Effect is limited to a narrow window around the Transcription Start Site (TSS) [13] | Effect is limited to a narrow window upstream of the TSS [13]; promoter accessibility can be a challenge [9] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Workflows

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

The functional divergence between these modalities stems from the nature of the Cas9 protein and its associated effector domains. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic principles of each technology.

Optimized Library Designs for Large-Scale Screens

For genome-wide chemogenomic screens, CRISPR libraries are designed for high efficiency and specificity. The Broad Institute has developed optimized human genome-wide libraries, each with distinct sgRNA design rules tailored to their modality [13].

Table 2: Optimized Genome-Wide CRISPR Libraries from the Broad Institute

| Library Name | Modality | sgRNA Design & Targeting | Key Features and Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello [13] | CRISPRko | ~4 sgRNAs/gene; 77,441 total sgRNAs | Designed for high on-target activity and reduced off-target effects; outperforms libraries with more sgRNAs per gene. |

| Dolcetto [13] | CRISPRi | 2 sets of 3 sgRNAs/gene; targets narrow window around TSS | Mitigates toxicity from DNA cutting; discriminates essential genes similarly to Brunello. |

| Calabrese [13] | CRISPRa | 2 sets of 3 sgRNAs/gene; targets -150 to -75 bp upstream of TSS | Uses tracrRNA with PP7 stem loops to recruit transcription factors; identified more hits than SAM method in resistance screens. |

Application in Chemogenomic Screens: Experimental Workflow

Conducting a genome-scale chemogenomic CRISPR screen involves a multi-step process that integrates molecular biology, cell culture, and next-generation sequencing. The following workflow and detailed protocol are adapted from established screening methodologies [14] [12] [15].

Detailed Screening Protocol

STEP 1: Select the Phenotypic Change and Cell Line The chosen phenotype must provide a basis for enrichment or depletion of edited cells. For chemogenomic screens, this is typically sensitivity or resistance to a drug-like compound. The cell line should be a relevant model for the experimental system but also easy to culture and transduce. The RPE1-hTERT p53−/− cell line is one example used in protocols with the TKOv3 library (70,948 sgRNAs targeting 18,053 genes) [14] [15].

STEP 2: Establish Cas9-Expressing Cells Stably integrate the Cas9, dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi), or dCas9-activator (for CRISPRa) into the target cell line. For the Guide-it CRISPR Genome-Wide sgRNA Library System, Cas9 lentivirus is used, and transduced cells are selected with puromycin. Isolating cells expressing Cas9 at an optimal level is critical for screen success [12].

STEP 3: Produce sgRNA Library Lentivirus and Transduce Cells Produce a high-titer lentiviral stock of the pooled sgRNA library. A critical step is to transduce the Cas9-expressing cells at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive only a single sgRNA. A transduction efficiency of 30-40% is often recommended to minimize the number of cells with multiple sgRNAs [12]. For a genome-wide screen, this requires scaling up to tens of millions of transduced cells to maintain library representation.

STEP 4: Perform the Screen and Harvest Genomic DNA Apply the selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment) to the population of sgRNA-expressing cells. Culture the cells long enough for phenotypes to manifest—typically 10-14 days for positive selection screens. Subsequently, harvest genomic DNA from both the treated and untreated control populations. The scale of DNA isolation is crucial; it must be performed on hundreds of millions of cells to maintain the diversity of sgRNA representation [14] [12].

STEP 5: Sequence and Analyze Results PCR-amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences from the genomic DNA and prepare next-generation sequencing libraries. The resulting sequencing data is analyzed using specialized software (e.g., MAGeCK, drugZ) to identify sgRNAs that are significantly enriched or depleted in the treated population compared to the control [14] [15]. Positive screens for drug resistance typically require a read depth of ~10 million reads, while more subtle negative screens may require up to 100 million reads [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screens

| Reagent / Material | Function in Screen | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Library | Contains pooled sgRNAs targeting genes genome-wide; the core screening reagent. | TKOv3: For knockout screens [14].Brunello (ko), Dolcetto (i), Calabrese (a): Optimized Broad Institute libraries [13]. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Produces lentivirus to deliver the sgRNA library and Cas9 constructs into target cells. | Systems like Lenti-X 293T cells are used to generate high-titer viral stocks [12]. |

| Cas9/dCas9 Effector Cell Line | Provides the stable, in-cell machinery for genomic editing or transcriptional modulation. | Cell lines with stable, inducible expression of Cas9 (for ko), dCas9-KRAB (for i), or dCas9-activator (for a) [12] [16]. |

| Selection Agents | Enriches for cells that have successfully integrated the lentiviral constructs. | Puromycin is commonly used to select for Cas9- and sgRNA-expressing cells [12]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | Identifies and quantifies sgRNA abundance in pre- and post-selection cell populations. | Illumina platforms are standard. Specialized analysis kits (e.g., Guide-it NGS Analysis Kit) are available [14] [12]. |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Tools | Statistically identifies significantly enriched or depleted genes from NGS data. | MAGeCK: Robust identification of essential genes from knockout screens [15].drugZ: Specifically designed for identifying chemogenetic interactions from knockout screens [15]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

CRISPR modalities are powerful tools for probing gene function and have been applied to identify genes involved in viral infection, therapy resistance, and neurodegenerative diseases [12]. A cutting-edge advancement is CRISPRai, a system for bidirectional epigenetic editing that enables simultaneous activation of one genomic locus and repression of another in the same cell [16]. This platform, when coupled with single-cell RNA sequencing (CRISPRai Perturb-seq), allows for the high-resolution mapping of genetic interactions and gene regulatory networks, providing unprecedented insights into context-specific genetic interactions that underlie drug responses [16].

In plant biology, CRISPRa shows promise for enhancing disease resistance by upregulating endogenous defense genes without altering the DNA sequence, offering a new strategy for crop improvement [11]. Furthermore, CRISPRa and CRISPRi are being explored as therapeutic modalities themselves, moving beyond screening tools into direct disease treatment by modulating the expression of endogenous genes to correct pathological states [17].

In chemogenomic research, where the interplay between small molecules and gene function is systematically probed, the design and selection of single guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries form the foundational step. A well-designed sgRNA library enables researchers to identify gene targets that modulate cellular response to chemical compounds, driving discoveries in drug development and functional genomics. The core challenge lies in creating a library that maximizes on-target editing efficiency while minimizing off-target effects, ensuring that screening results are both specific and reproducible [18] [19]. The selection of the sgRNA sequence is paramount, as it directly influences the success of the screen by determining how accurately the CRISPR system can target and perturb genes of interest.

This technical guide details the essential components of sgRNA library design and selection, framed within the context of preparing robust tools for chemogenomic screens. We will explore the critical design parameters, benchmark different library architectures, outline experimental workflows for implementation, and describe the bioinformatic analysis required to interpret screening data. Adherence to the principles outlined here will ensure that researchers can construct and utilize sgRNA libraries that yield high-quality, reliable data for identifying essential genes and therapeutic targets.

Core Design Principles for sgRNA Libraries

Sequence Features for Optimal On-Target Activity

The efficacy of an sgRNA is largely determined by its sequence composition. Several key features must be considered during design to ensure high on-target activity.

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Specificity: The Cas9 enzyme requires a specific PAM sequence to bind and cleave DNA. For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where 'N' is any nucleotide. The target genomic sequence must be located immediately adjacent to a PAM site for cleavage to occur [18].

- Guide Length: The optimal length for the target-specific protospacer sequence is 20 nucleotides for SpCas9. Shorter guides often suffer from reduced on-target editing efficiency [18].

- GC Content: The GC content of the sgRNA should ideally be between 40% and 80%. Guides falling within this range tend to have improved stability and binding efficiency [20].

- Sequence Composition: Avoid sgRNAs with homopolymeric nucleotide stretches (e.g., long runs of a single base) or those that bind to genomic sites with high single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) density, particularly near the PAM-distal region, as this can compromise hybridization efficiency [21].

Strategies for Minimizing Off-Target Effects

Off-target activity, where the Cas9 complex cleaves unintended genomic sites, is a major source of false positives in CRISPR screens. Mitigation strategies are a critical component of library design.

- Specificity Scoring: Employ computational algorithms to predict and minimize off-target effects. The Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) score is a widely used metric for evaluating potential off-target sites [21].

- Genomic Alignment: Filter out sgRNAs that align to multiple genomic locations (e.g., more than six sites) to ensure high specificity [21].

- Functional Domain Targeting: For negative selection or dropout screens, designing sgRNAs to target conserved protein domains can increase the likelihood of generating a loss-of-function phenotype. This strategy leverages the functional importance of these domains to improve screening sensitivity [21].

Table 1: Key sgRNA Design Parameters and Their Optimal Values

| Design Parameter | Optimal Value or Feature | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| PAM Sequence | NGG (for SpCas9) | Essential for Cas9 binding and DNA cleavage [18]. |

| Protospacer Length | 20 nucleotides | Maximizes on-target editing efficiency [18]. |

| GC Content | 40–80% | Enhances sgRNA stability and binding efficiency [20]. |

| Off-Target Filtering | CFD score; ≤6 genomic alignments | Reduces unintended edits and false positives [21]. |

| Target Location | Conserved protein domains (for knockout) | Increases probability of disruptive mutation in dropout screens [21]. |

Library Architecture and Selection

Library Sizing and Composition

A CRISPR library is a collection of sgRNAs designed to target multiple genes across the genome. Its architecture directly impacts screening cost, scalability, and statistical power.

- sgRNAs per Gene: It is standard practice to include multiple sgRNAs (typically 3-10) per target gene. This redundancy controls for variable activity among individual sgRNAs and helps distinguish true hits from false positives by looking for consistent phenotypes across multiple guides targeting the same gene [19] [22].

- Library Representation: To maintain library diversity throughout the screen, each sgRNA must be represented in a large number of cells. A common guideline is to ensure 50 to 1000x coverage, meaning 50 to 1000 cells per sgRNA in the pool at the start of the screen [22] [21] [23]. The total number of cells required is calculated as: (Number of sgRNAs in library) x (Desired coverage).

- Control sgRNAs: Libraries should include non-targeting control sgRNAs (e.g., 500 in the H-mLib library) that do not target any genomic sequence. These are essential for establishing a baseline in data analysis and for quality control [21].

Benchmarking Published Library Designs

Several genome-wide human sgRNA libraries have been developed and benchmarked, each with distinct characteristics. The choice of library depends on the specific experimental needs, such as the desired balance between comprehensiveness and practical manageability.

Table 2: Comparison of Published Genome-Wide Human sgRNA Libraries

| Library Name | Target Genes | sgRNA Count | Key Features | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-mLib [21] | ~21,000 | ~42,000 (2 per gene) | Minimal library size; uses dual-sgRNA vector; high CDD targeting rate. | Screening with limited cell numbers (e.g., primary cells). |

| Brunello [21] | ~19,000 | ~77,000 (4 per gene) | Designed with improved on-target efficiency rules (Rule Set 2). | High-sensitivity genome-wide knockout screens. |

| TKOv3 [14] [24] | ~18,000 | ~71,000 | Curated library used in chemogenomic protocols. | Dropout screens and chemogenomic studies. |

| Avana [19] | ~18,000 | ~6 per gene | Designed with Rule Set 1; validated in positive/negative selection. | Viability and drug resistance screens. |

| GeCKOv2 [19] | ~19,000 | ~6 per gene | Earlier, widely-used library; serves as a common benchmark. | General genome-wide screening. |

Subsampling analysis has shown that screening with a subset of sgRNAs per gene (e.g., 4 instead of 6) can still recover a high percentage (over 90%) of hits when using a relaxed false discovery rate (FDR) threshold, suggesting a viable strategy for primary screens followed by secondary validation [19].

Experimental Workflow for Library Screening

The process of conducting a pooled CRISPR screen involves a multi-step workflow, from library delivery to phenotypic selection.

Diagram 1: sgRNA Screening Workflow.

Library Delivery and Cell Transduction

- Lentiviral Delivery: sgRNA libraries are typically cloned into lentiviral vectors to ensure stable integration of a single sgRNA per cell, which is crucial for linking genotype to phenotype [22].

- Stable Cas9 Expression: Target cells must express the Cas9 nuclease. This is often achieved by generating a stable cell line with lentivirally delivered Cas9, followed by selection (e.g., with puromycin) [22].

- Low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI): Cells are transduced with the lentiviral sgRNA library at a low MOI (aiming for 30-40% transduction efficiency). This ensures most infected cells receive only one unique sgRNA, maintaining a clear genotype-phenotype link [22].

Phenotypic Selection and Sample Preparation

Screens are broadly categorized based on the phenotype they select for.

- Positive Selection: Cells with a growth advantage (e.g., drug resistance) under selective pressure become enriched. Sequencing reveals sgRNAs that are more abundant in the final population [22].

- Negative Selection (Dropout): Cells lacking genes essential for survival under screening conditions are depleted. The corresponding sgRNAs become less abundant. These screens are often more challenging and require greater sequencing depth [24] [22].

For sample preparation, genomic DNA (gDNA) is harvested from a sufficient number of cells to maintain library representation (e.g., ~76 million cells for a 300x coverage) [22] [23]. The integrated sgRNA sequences are then PCR-amplified from the gDNA, with primers adding Illumina sequencing adapters and sample barcodes, and prepared for next-generation sequencing (NGS) [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for sgRNA Library Screens

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit [23] | High-quality gDNA extraction from harvested screen cells. | Isolating gDNA from millions of transduced cells for NGS library prep. |

| Qubit dsDNA Assay Kit [23] | Accurate quantification of gDNA and PCR product concentration. | Ensuring precise input amounts for PCR amplification of sgRNAs. |

| Herculase PCR Reagents [23] | High-fidelity amplification of sgRNA regions from gDNA. | Preparing NGS libraries with minimal bias for sequencing. |

| GeneJET PCR Purification Kit [23] | Purification of PCR-amplified sgRNA NGS libraries. | Removing enzymes and primers post-amplification before sequencing. |

| Lenti-X 293T Cells [22] | Production of high-titer lentiviral particles. | Generating the sgRNA library virus for cell transduction. |

| Lenti-X GoStix Plus [22] | Rapid titration of lentiviral preparations. | Quickly estimating viral titer to determine volume for transduction. |

Data Analysis and Hit Identification

Following NGS, bioinformatic tools are used to quantify changes in sgRNA abundance between the selected population and a control (e.g., the initial plasmid library or a non-selected cell population).

Analysis Workflows and Algorithms

The raw sequencing data undergoes a standard analysis pipeline.

- Sequence Quality Assessment: Check the quality of the NGS reads.

- Read Alignment: Map the sequenced reads to the reference sgRNA library to generate a count table for each sgRNA in each sample.

- Read Count Normalization: Normalize counts to account for differences in library size and distribution.

- Statistical Enrichment/Depletion Analysis: Apply specialized algorithms to identify sgRNAs, and consequently genes, that are significantly enriched or depleted [24].

Several algorithms have been developed or repurposed for this critical step:

- MAGeCK (Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout): A widely used method that employs a negative binomial model to test for sgRNA significance and then uses Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) to identify key genes from the collective behavior of their targeting sgRNAs [24].

- STARS (STARS Analysis): A gene-ranking system that rewards genes where a high fraction of sgRNAs score significantly [19].

- BAGEL (Bayesian Analysis of Gene EssentiaLity): A Bayesian framework that compares the distribution of sgRNA log-fold-changes for a target gene to a set of known core essential and non-essential genes to compute a Bayes factor for essentiality [24].

- DrugZ: An algorithm specifically designed for chemogenomic screens. It uses a normal distribution-based model to identify drug-gene interactions by comparing sgRNA abundances in drug-treated versus control samples [24].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline.

The meticulous design and selection of sgRNA libraries are paramount for the success of chemogenomic CRISPR screens. By adhering to established rules for on-target efficiency and off-target minimization, researchers can construct libraries with high specificity and sensitivity. The choice of library architecture—balancing size, redundancy, and coverage—must be tailored to the biological question and experimental constraints. When coupled with a robust experimental workflow and rigorous bioinformatic analysis, a well-designed sgRNA library becomes a powerful tool for unraveling gene function and identifying novel drug targets, thereby advancing our understanding of cellular responses to chemical perturbations.

The Role of Optimized Libraries (e.g., Brunello, Dolcetto) in Enhancing Performance

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic screening by providing robust on-target activity and high fidelity, surpassing RNA interference (RNAi) as the preferred method for systematic interrogation of gene function [25]. Unlike RNAi, which merely knocks down gene expression, CRISPR technology enables multiple screening modalities: unmodified Cas9 generates complete loss-of-function alleles (CRISPR knockout, or CRISPRko), while nuclease-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) can be tethered to inhibitory domains (CRISPR interference, or CRISPRi) or activating domains (CRISPR activation, or CRISPRa) to precisely regulate gene expression [25]. The creation of optimized genome-wide libraries for these modalities—including Brunello for CRISPRko, Dolcetto for CRISPRi, and Calabrese for CRISPRa—represents a critical advancement in functional genomics, particularly for chemogenomic screens that probe gene-compound interactions [25] [14]. These libraries provide researchers with a suite of tools to efficiently interrogate gene function with enhanced performance, distinguishing essential and non-essential genes with unprecedented accuracy and enabling the discovery of novel drug targets and resistance mechanisms.

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparisons of CRISPR Libraries

Key Performance Metrics for Library Evaluation

The performance of CRISPR libraries is quantitatively assessed using specific metrics in negative selection (dropout) screens. The delta area under the curve (dAUC) metric provides a size-unbiased measurement of a library's ability to distinguish essential from non-essential genes [25]. This metric calculates the difference between the AUC of sgRNAs targeting essential genes (which should deplete) and the AUC of sgRNAs targeting non-essential genes (which should remain constant) [25]. Additionally, the area-under-the-curve of the receiver-operator characteristic (ROC-AUC) evaluates gene-level performance by treating essential genes as true positives and non-essential genes as false positives, highlighting the value of having multiple effective sgRNAs per gene [25].

Quantitative Performance of Optimized Libraries

Extensive comparative analyses demonstrate that optimized libraries significantly outperform earlier generations of CRISPR tools. The Brunello CRISPRko library (comprising 77,441 sgRNAs, with an average of 4 sgRNAs per gene and 1000 non-targeting controls) shows superior performance in direct comparisons [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPRko Libraries in Negative Selection Screens

| Library Name | sgRNAs per Gene | dAUC Value | ROC-AUC Value | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello | 4 | 0.80 | 0.94 | Highest performance with fewer sgRNAs [25] |

| Avana | 4-6 | 0.70 | 0.89 | Intermediate performance [25] |

| GeCKOv2 | 6 | 0.46 | 0.85 | Baseline CRISPRko performance [25] |

| GeCKOv1 | 3-4 | 0.24 | 0.65 | Early CRISPRko library [25] |

The improvement from GeCKOv2 to Brunello (ddAUC = 0.22) exceeds the average improvement from RNAi to GeCKOv2 (ddAUC = 0.17) in Project Achilles, demonstrating the substantial leap in screening technology [25]. Similarly, the Dolcetto CRISPRi library achieves comparable performance to CRISPRko in detecting essential genes despite containing fewer sgRNAs per gene, while the Calabrese CRISPRa library outperforms the SAM approach at identifying vemurafenib resistance genes [25].

Subsampling analysis reveals that even with just one sgRNA per gene, the Brunello library outperforms the GeCKOv2 library with six sgRNAs per gene, highlighting the profound impact of improved sgRNA design [25]. This enhanced efficiency is particularly valuable in settings where cell numbers are limiting, such as screens in primary cells or in vivo models [25].

Experimental Protocols for Genome-Scale CRISPR Screens

Workflow for Pooled CRISPR Screening

Implementing a successful genome-scale CRISPR screen requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines the key steps for conducting pooled screens using optimized libraries:

Diagram 1: CRISPR Screen Workflow

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Cell Line Preparation and Library Transduction

The screening process begins with selecting an appropriate cell line that serves as a good surrogate for the biological system under investigation [26]. For the TKOv3 library protocol, the RPE1-hTERT p53−/− cell line has been successfully utilized, though the approach can be customized for other lines [14]. Cells must first be engineered to stably express Cas9 (for CRISPRko) or dCas9 fusion proteins (for CRISPRi/CRISPRa) through lentiviral transduction and antibiotic selection [26]. Critical parameters include:

- Multiplicity of Infection (MOI): Aim for ~0.5 to ensure most transduced cells receive only a single viral integrant [25]

- Transduction Efficiency: Optimize to achieve 30-40% efficiency to minimize multiple sgRNA integrations per cell [26]

- Cell Coverage: Maintain a minimum of 500x coverage, meaning each sgRNA is represented in at least 500 unique cells [25]

Screening Execution and Sample Processing

After establishing Cas9-expressing cells, the sgRNA library is delivered via lentiviral transduction at the predetermined MOI [26]. For negative selection screens, cells are passaged for approximately 3 weeks to allow depletion of essential genes, while positive selection screens typically require 10-14 days of selection pressure [25] [26]. Key considerations include:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality gDNA from 100-200 million cells (approximately 400-1000 cells per sgRNA) using maxi-prep scale methods to maintain sgRNA representation [26]

- Sequencing Depth: Negative screens require greater sequencing depth (up to ~100 million reads) due to subtle changes in sgRNA representation, while positive screens typically need ~10 million reads [26]

- NGS Library Preparation: Include barcodes for sample multiplexing and primer staggering to maintain library complexity [26]

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screening

Successful implementation of CRISPR screens requires specific reagents and tools optimized for each step of the process. The following table details essential components and their functions:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Screens

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized sgRNA Libraries (Brunello, Dolcetto, Calabrese) | Targeting specific genes with high on-target, low off-target activity | Brunello: 77,441 sgRNAs, 4/gene; Dolcetto: CRISPRi; Calabrese: CRISPRa [25] |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Delivery of sgRNA libraries into target cells | Enables single-copy integration for precise genotype-phenotype linkage [26] |

| Cas9/dCas9-Expressing Cell Lines | Provides the CRISPR effector machinery | Stable integration with selection markers (e.g., puromycin) [26] |

| Selection Antibiotics (e.g., Puromycin) | Enrichment for successfully transduced cells | Critical for maintaining library representation [26] |

| NGS Library Preparation Kits | Amplification and preparation of sgRNA sequences for sequencing | Must include features for Illumina sequencing and sample barcoding [26] |

Advanced Applications in Chemogenomic Screening

Chemogenomic Dropout Screens

Chemogenomic CRISPR screens represent a powerful approach for identifying gene-compound interactions, revealing mechanisms of action, and understanding resistance pathways. The protocol for genome-scale chemogenomic dropout screens using the TKOv3 library (containing 70,948 sgRNAs targeting 18,053 genes) involves treating cells with a genotoxic agent after library transduction and monitoring sgRNA depletion over time [14]. This approach enables systematic identification of genes essential for survival under specific compound treatments, providing insights into synthetic lethal interactions and drug mechanism of action.

Diagram 2: Chemogenomic Screen Logic

Multi-Modality Approaches for Comprehensive Functional Genomics

The availability of optimized libraries for multiple CRISPR modalities enables researchers to approach biological questions from complementary angles. While CRISPRko produces complete and permanent gene knockout, CRISPRi and CRISPRa offer reversible, tunable regulation of gene expression [25]. This multi-modal approach is particularly valuable for:

- Essential Gene Analysis: CRISPRi achieves comparable performance to CRISPRko in detecting essential genes but with transient modulation [25]

- Activation Screens: Calabrese CRISPRa outperforms SAM library in identifying vemurafenib resistance genes, demonstrating utility in drug resistance studies [25]

- Comparative Analysis: Parallel screens using multiple modalities can distinguish between structural and regulatory requirements for genes, providing deeper mechanistic insights

The direct comparison of CRISPRa with genome-scale libraries of open reading frames (ORFs) further validates hits and provides orthogonal confirmation of screening results [25].

Optimized CRISPR libraries such as Brunello, Dolcetto, and Calabrese represent a significant advancement in the toolkit available for chemogenomic screens and functional genomics research. Their enhanced performance in distinguishing essential and non-essential genes, coupled with reduced off-target effects, provides researchers with more reliable and interpretable data [25]. The quantitative improvements in metrics like dAUC and ROC-AUC directly translate to increased power in detecting genuine hits while reducing false positives [25]. As these libraries become more widely adopted and screening protocols continue to be refined, they will undoubtedly accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and deepen our understanding of gene function in both health and disease. The integration of these optimized tools into chemogenomic screening pipelines represents a critical step forward in systematic drug target identification and validation.

Core Concepts and Workflows

Functional genetic screens are a foundational tool in modern biology and drug discovery, enabling the systematic identification of genes involved in specific biological processes or disease states. Within chemogenomic research, which explores the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems, two primary screening formats have emerged: pooled and arrayed. These approaches differ fundamentally in how genetic perturbations are organized, delivered, and analyzed, each offering distinct advantages for different experimental scenarios [27] [28].

In a pooled screen, a mixture of thousands of different guide RNAs (gRNAs) is introduced simultaneously into a single population of cells. The cells are then subjected to a selective pressure, and the gRNAs that become enriched or depleted are identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS). This approach is highly scalable for studying thousands of genes in parallel [27] [29]. In contrast, an arrayed screen involves isolating each genetic perturbation—typically one gene target—in individual wells of a multiwell plate. This format allows researchers to easily link complex cellular phenotypes to specific genetic manipulations without the need for complex deconvolution steps [27] [30].

The workflows for these screening strategies differ significantly, from library construction to final readout, as illustrated below.

Comparative Analysis of Screening Formats

The choice between pooled and arrayed screening involves multiple considerations, from assay compatibility to resource constraints. The table below provides a detailed comparison of key parameters to guide experimental design.

| Parameter | Pooled Screening | Arrayed Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Compatibility | Binary assays only (viability, FACS) [27] [28] | Binary and multiparametric assays (high-content imaging, morphology) [27] [28] |

| Phenotypic Resolution | Population-level enrichment/depletion [27] | Single-cell resolution within isolated wells [30] |

| Scalability | High (genome-wide) [29] | Moderate (focused libraries) [29] |

| Cell Model Compatibility | Best for proliferating, easy-to-transfect cells [27] | Suitable for primary cells, neurons, and various cell types [27] |

| Data Deconvolution | Required (NGS and bioinformatics) [27] [28] | Not required [27] [28] |

| Equipment Needs | Standard lab equipment [27] | Automation, liquid handlers, high-content imaging systems [27] |

| Upfront Cost | Lower [27] | Higher [27] |

| Detectable Phenotypes | Strong survival advantages/disadvantages [31] | Subtle, complex, and mild phenotypes [30] [31] |

Advanced Screening Modalities: Optical Pooled Screening

A cutting-edge hybrid approach, optical pooled screening (OPS), combines the scalability of pooled libraries with the rich phenotypic data of imaging. In OPS, cells are transduced with a pooled, barcoded library. After image-based phenotyping, perturbation identities are determined directly in the fixed cells through in situ sequencing of the barcodes [32] [33]. This method enables the screening of complex spatial and temporal phenotypes, such as protein localization and dynamic signaling events, at a scale traditionally only possible with simple pooled screens [32]. For instance, one study used OPS to screen genes affecting NF-κB signaling and discovered that Mediator complex subunits regulate the duration of p65 nuclear retention—a finding difficult to capture with traditional methods [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pooled CRISPR Screen

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a pooled CRISPR knockout screen, a method widely used for genome-wide loss-of-function studies [27] [28].

Library Construction and Validation

- Library Acquisition: Obtain a pooled sgRNA library as a glycerol stock of E. coli containing the plasmid library. These libraries typically include multiple sgRNAs per gene (e.g., 3-10) to increase confidence in genotype-phenotype correlations [27].

- Plasmid Preparation: Amplify the plasmid library through large-scale PCR and purify it. Validate the library by NGS to ensure equal representation of all sgRNAs and the absence of major dropouts [27].

- Viral Packaging: Transfect the plasmid library into a lentiviral packaging cell line (e.g., HEK293T) to produce viral particles. Harvest the supernatant containing the lentiviral library and concentrate it if necessary [27] [28].

Library Delivery and Transduction

- Cell Preparation: Culture the target cells, which must either stably express Cas9 or be co-transduced with a Cas9 vector [27].

- Transduction Optimization: Perform a pilot transduction to determine the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI), aiming for an MOI of ~0.3-0.4. This ensures most transduced cells receive only one viral particle, minimizing the chance of multiple perturbations in a single cell [27] [31].

- Selection and Expansion: Transduce the entire cell population with the pooled viral library. Enrich for successfully transduced cells using antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin) for 3-7 days. Expand the cell population to obtain sufficient numbers for the screen, ensuring maintained library representation (typically aiming for 500-1000x coverage per sgRNA) [27].

Application of Selective Pressure

- Screen Execution: Split the transduced cell population into experimental and control arms. Apply the selective pressure relevant to your biological question. For a negative selection screen (e.g., identifying essential genes for cell survival under drug treatment), the control arm is typically an untreated sample representing the baseline library. For a positive selection screen (e.g., identifying resistance genes), the experimental arm is the one that survives the pressure [27] [28].

- Alternative Assays: If not using viability, a biomarker can be tagged, and cells can be separated based on fluorescence using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [27].

Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS Library Preparation

- Harvesting and Extraction: Harvest cells from both the experimental and control populations after selection. Extract high-quality genomic DNA from a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 100x coverage per sgRNA) to maintain library representation [27].

- sgRNA Amplification: Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences from the genomic DNA using a two-step PCR protocol. The first PCR amplifies the sgRNA region with specific primers, and the second PCR adds Illumina adapters and sample barcodes to allow for multiplexing [27] [34].

- Sequencing: Purify the final PCR product and quantify the NGS library using methods like qPCR or fluorometry. Pool libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform to a depth sufficient to count each sgRNA accurately [34] [35].

Data Analysis and Hit Identification

- sgRNA Quantification: Demultiplex the sequencing data and align reads to the reference sgRNA library to generate count files for each sample [27].

- Statistical Analysis: Use specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK) to compare sgRNA abundances between the experimental and control groups. These tools identify sgRNAs, and consequently genes, that are significantly enriched or depleted after selection [31].

Protocol 2: Arrayed CRISPR Screen

This protocol describes an arrayed CRISPR screen using a plasmid-based sgRNA library, ideal for focused, high-content studies [31].

Library Design and Plate Formatting

- Library Design: Design a library targeting a specific gene set (e.g., a kinase library). Include multiple sgRNAs per gene (e.g., 3) to enhance knockout efficiency and confidence. Design sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential, for instance, by requiring a minimum number of mismatches to any other genomic site [31].

- Source and Format: The library can be sourced as individual plasmids, pre-arrayed lentivirus, or synthetic sgRNAs in a multiwell plate (e.g., 96-well or 384-well format). For plasmid-based screens, array the sgRNA expression plasmids into master plates [30] [31].

Reverse Transfection of CRISPR Components

- Plate Preparation: Dilute a transfection reagent in an appropriate medium and dispense it into each well of the assay plates. Transfer the arrayed sgRNAs from the master plate to the assay plates. For a complete knockout, include a Cas9 expression plasmid or complex with recombinant Cas9 protein to form Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) in each well [30] [31].

- Cell Seeding: Prepare a suspension of Cas9-expressing cells and seed them directly into each well of the assay plate containing the transfection mix. The reverse transfestion process occurs as cells settle and attach [31].

Phenotypic Assay and Incubation

- Knockout Incubation: Incubate the transfected cells for a sufficient period (e.g., 3-5 days) to allow for protein turnover and the full manifestation of the knockout phenotype [31].

- Assay Application: If applicable, treat cells with a compound or stimulus. Then, perform the phenotypic assay. For image-based assays, this typically involves fixing and staining cells with fluorescent antibodies or dyes, followed by automated imaging on a high-content microscope (e.g., PerkinElmer Operetta) [31].

Image and Data Analysis

- Image Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler) to extract quantitative features from the images on a per-well basis, such as cell count, fluorescence intensity, or morphological parameters [31].

- Hit Calling: Normalize the data per plate (e.g., using Z-scores or B-scores) to account for plate-based artifacts. Compare the phenotypic readout of each well (gene knockout) to control wells (non-targeting sgRNAs). Genes whose knockout produces a statistically significant phenotype are considered hits [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a genetic screen relies on a carefully selected set of reagents and instruments. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the workflows described above.

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Library | EditCo Whole Genome gRNA libraries [27]; IDT arrayed sgRNA libraries [30] | Provides the collection of genetic perturbations targeting specific gene sets. |

| Delivery Vector | LentiGuide-BC [32]; CROP-seq vector [32] | Delivers sgRNA and sometimes a barcode into the target cell's genome. |

| Cas9 Source | Cas9-expressing cell line; recombinant Cas9 protein [27] [30] | The nuclease enzyme that executes the DNA cut directed by the sgRNA. |

| Delivery Method | Lentiviral transduction [27]; Lipofection/electroporation of RNPs [30] | Introduces the CRISPR components into the target cells. |

| Selection Agent | Puromycin; Geneticin (G418) [27] | Enriches for cells that have successfully integrated the perturbation vector. |

| Phenotyping Assay | High-content imager (e.g., Operetta) [31]; FACS sorter [27] | Measures the cellular outcome (phenotype) of the genetic perturbation. |

| NGS Prep Kit | xGen NGS DNA Library Preparation Kits [36] | Prepares the amplified sgRNAs from genomic DNA for sequencing. |

| Analysis Software | MAGeCK [31]; CellProfiler [31] | Analyzes NGS data or microscopic images to identify hit genes. |

Strategic Selection and Integrated Workflows

The choice between screening formats is not mutually exclusive. A powerful and efficient strategy involves using both methods in a tiered approach: an initial genome-wide pooled screen to identify a broad list of candidate "hit" genes, followed by a more focused arrayed screen to validate these hits using more complex, information-rich phenotypic assays in biologically relevant models [27] [28]. This combined workflow leverages the respective strengths of each format to build robust and actionable conclusions for target identification in chemogenomic research.

Executing a Screen: From Library Preparation to Phenotypic Readout

In the realm of chemogenomic screens, where the relationship between chemical compounds and genetic function is systematically explored, the preparation of high-quality genetic libraries is foundational. This technical guide details a critical preparatory workflow: the process of introducing genetic material into cells via lentiviral transduction and subsequently harvesting the genomic DNA (gDNA) for downstream analysis. Mastering this workflow is essential for robust screen outcomes, enabling the discovery of drug targets, mechanisms of action, and resistance pathways.

The overarching process begins with the introduction of a genetic library (e.g., a CRISPR library) into a population of target cells and culminates with the extraction of high-quality gDNA for next-generation sequencing. This process can be divided into two main phases: Library Transduction and Genomic DNA Harvest.

A thorough planning stage is crucial for success. Before initiating experiments, researchers must define their screening goals and select the appropriate viral vector system. Lentiviral vectors are often the system of choice for chemogenomic screens due to their ability to stably integrate into the host genome and infect both dividing and non-dividing cells [37] [38]. Furthermore, a well-designed experiment incorporates the necessary controls, including cells transduced with a non-targeting guide RNA (for CRISPR screens) and untransduced cells, to account for background effects and experimental variability [39].

Phase 1: Lentiviral Transduction

Lentiviral transduction is a method for introducing a target gene into recipient cells using viral vectors, facilitating its stable, long-term expression [37]. This stability is paramount in chemogenomic screens that span multiple cell divisions.

Key Reagents and Materials

The following reagents are essential for the viral transduction phase of the workflow.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Lentiviral Transduction

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vector | Delivers the genetic cargo (e.g., gRNA, shRNA) into the target cell. | For screens, a pooled library (e.g., genome-wide CRISPRko) is used. The vector often contains a selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance) [39] [40]. |

| Packaging Plasmids & Production Cell Line | Used to produce functional viral particles. The plasmids (gag/pol, rev, vsv-g) provide viral proteins in trans. HEK293T cells are commonly used. | Third- or fourth-generation systems offer enhanced safety. The production cell line should be easy to transfect and maintain [37] [39]. |

| Polybrene | A cationic polymer that enhances transduction efficiency by neutralizing charges between viral particles and the cell membrane. | Typically used at 6–8 µg/mL. Can be toxic to some cell types; concentration should be optimized [37] [39]. |

| Target Cells | The cellular model for the chemogenomic screen. | Cell health and passage number are critical. The Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) must be determined empirically for each cell line. |

| Puromycin | An antibiotic used to select for successfully transduced cells, which express the resistance gene. | The optimal killing concentration and duration must be determined via a kill-curve assay prior to the screen [37] [39]. |

Detailed Transduction Protocol

This protocol assumes the availability of a pre-packaged, titered lentiviral library.

- Cell Preparation and Seeding: Harvest the target cells and seed them into an appropriate culture vessel (e.g., 6-well plate, 10 cm dish). The cell density at the time of transduction is critical. A density of 1–2 x 10^5 cells/mL is often recommended, but this should be optimized to achieve ~50% confluency at the time of infection [37]. Proper cell health is paramount.

- Viral Transduction:

- Prepare the transduction medium. This is often serum-free medium to prevent interference with viral infection [37] [39].

- Add the predetermined volume of lentivirus to achieve the desired MOI. The MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) is the ratio of viral particles to cells. For dividing cells, an MOI of 50-100 is typical, but non-dividing or primary cells may require a higher MOI [37].

- Add Polybrene to the medium at a final concentration of 6-8 µg/mL to enhance infection efficiency [37].

- Gently swirl the plate to mix and incubate the cells for 24 hours.

- Post-Transduction Culture and Selection:

- After 24 hours, carefully remove the virus-containing medium and replace it with fresh, complete growth medium.

- Allow the cells to recover for 24-48 hours.

- Begin puromycin selection. Add the pre-determined optimal concentration of puromycin to the culture medium to eliminate non-transduced cells. Selection typically continues for 3-7 days, until a stable population of resistant cells emerges [37] [39].

- Validate transduction efficiency, for example, by using a fluorescence microscope if the vector contains a fluorescent marker [39].

- Cell Expansion and Screening:

- Once a stable, selected pool of transduced cells is established, expand them for the subsequent chemogenomic screen.

- Proceed with the screen by applying the chemical compound or selective pressure of interest. The duration of this step is experiment-dependent.

Phase 2: Genomic DNA Harvest

Following the screen and phenotypic selection, high-quality genomic DNA must be isolated from the cell population. The integrity and purity of this gDNA are critical for accurate PCR amplification of the integrated library elements (e.g., gRNAs) prior to sequencing.

Principles of DNA Extraction

Most DNA purification methods follow five basic steps [41]:

- Creation of Lysate: Disruption of the cellular structure to release nucleic acids into solution. This can be achieved by physical, enzymatic, or chemical methods, or a combination thereof.

- Clearing of Lysate: Separation of soluble DNA from cell debris and other insoluble material, typically via centrifugation, filtration, or bead-based methods.

- Binding to Purification Matrix: The DNA of interest is bound to a specific matrix (e.g., silica membrane/beads) under high-salt conditions.

- Washing: Proteins, salts, and other contaminants are washed away from the matrix using ethanol-containing buffers.

- Elution: Purified DNA is released from the matrix under low-salt conditions using TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

Detailed gDNA Harvest Protocol

This protocol is adaptable for column-based or magnetic bead-based purification kits.

- Cell Harvest and Lysis:

- Harvest the pelleted cells after the screen. Typically, 1-5 x 10^6 cells are sufficient for most commercial kits, but the number should be scaled according to the manufacturer's instructions and the requirements of downstream sequencing.

- Resuspend the cell pellet thoroughly in a lysis buffer containing a chaotropic salt (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride) and a detergent (e.g., SDS). These components disrupt cells, inactivate nucleases, and create conditions for DNA to bind to the purification matrix [41]. For some yeast or bacterial cells, an enzymatic pre-treatment (e.g., lysozyme, zymolase) may be necessary to break down tough cell walls [42].

- Optional RNase Treatment: To obtain pure DNA without RNA contamination, add RNase A to the lysate and incubate according to the manufacturer's protocol [41].

- Bind, Wash, and Elute DNA:

- For column-based systems: Transfer the lysate to a silica membrane column. Centrifuge to bind the DNA to the membrane. Wash the membrane with the provided wash buffers to remove contaminants. Centrifuge the empty column to dry the membrane. Elute the DNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer [41].

- For magnetic bead-based systems: Add silica-coated magnetic particles to the lysate. Bind the DNA to the beads by mixing. Use a magnet to separate the beads from the supernatant. Wash the beads while they are immobilized by the magnet. Elute the DNA from the beads into an aqueous solution [41].

- DNA Quantification and Quality Control: Precisely quantify the DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit, Picogreen), which is more accurate for gDNA than spectrophotometry. Assess DNA purity by measuring the A260/A280 ratio (ideal range: ~1.8) and check for degradation by running an aliquot on an agarose gel. High molecular weight gDNA should appear as a tight, high-molecular-weight band.

The Scientist's Toolkit: DNA Harvest

This table lists key materials and reagents required for the genomic DNA harvest.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Genomic DNA Harvest

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cell and nuclear membranes to release gDNA. Contains chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine HCl) and detergents (e.g., SDS). | In-house preparation is possible, but commercial buffers are optimized for specific kits and ensure consistency [41]. |

| Silica Membrane Column or Magnetic Beads | The solid-phase matrix that selectively binds DNA in the presence of chaotropic salts and alcohol. | Magnetic beads are amenable to high-throughput, automated workflows. Columns are simple and effective for manual processing [41]. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes contaminants, proteins, and salts from the bound DNA. Typically contains ethanol. | Ensure buffers are prepared with the correct ethanol concentration as per the kit protocol. |

| Elution Buffer (TE or Water) | Releases purified DNA from the binding matrix. | Low-ionic-strength solutions like TE buffer or nuclease-free water are used. TE buffer (with EDTA) helps inhibit nucleases for long-term storage [41]. |

| RNase A | Degrades contaminating RNA, which can co-purify with gDNA and skew quantification. | Essential for obtaining RNA-free gDNA for accurate quantification and downstream PCR [41]. |

Downstream Processing and Data Quality Assurance

The purified gDNA is the template for amplifying the integrated library elements. For a CRISPR screen, this involves PCR amplification of the gRNA region with primers containing Illumina adapter sequences for next-generation sequencing.

The quality of the final sequencing data is directly traceable to the initial steps of this workflow. Key parameters to monitor for a successful screen are summarized below.

Table 3: Critical Parameters for Screen Success

| Parameter | Impact on Screen | Quality Control Check |

|---|---|---|

| Transduction Efficiency | Low efficiency results in an insufficient representation of the library, leading to high noise and poor statistical power. | Check fluorescence (if applicable) or use qPCR to measure proviral copy number before selection [43]. |

| Library Coverage | Maintaining a high number of cells per gRNA (e.g., 500-1000x) during transduction and expansion prevents the loss of library elements due to stochastic drift. | Calculate cell numbers and library complexity at the transduction step. |

| gDNA Yield & Purity | Low yield or impure gDNA (e.g., with residual salts or RNA) can inhibit the PCR amplification of gRNAs, introducing bias. | Use fluorometric quantification and check A260/A280 ratios. Run a gel to confirm high molecular weight. |

| gDNA Integrity | Fragmented gDNA can lead to inefficient amplification of the target gRNA sequence, skewing gRNA abundance counts. | Analyze gDNA by agarose gel electrophoresis. A sharp, high-molecular-weight band indicates good integrity. |

The seamless integration of a robust viral transduction protocol with a reliable genomic DNA harvest method forms the bedrock of a successful chemogenomic screen. Attention to detail at every step—from optimizing the MOI and ensuring high transduction efficiency to extracting pure, high-molecular-weight gDNA—is non-negotiable. By adhering to the detailed workflows and quality control measures outlined in this guide, researchers can generate sequencing-ready gDNA that faithfully represents the genetic landscape of the post-screen cell population, thereby ensuring the identification of high-confidence, biologically relevant hits that advance the discovery of new therapeutic targets and pathways.

This technical guide details the foundational parameters essential for robust experimental design in chemogenomic CRISPR screens. Focusing on Multiplicity of Infection (MOI), library coverage, and cell numbers, we provide a structured framework to ensure the validity and reproducibility of genome-scale screens. Adherence to these principles enables researchers to accurately identify gene-phenotype relationships, thereby advancing drug discovery and functional genomics.

Chemogenomic screens combine CRISPR-mediated genetic perturbations with chemical compounds to elucidate gene function and drug mechanisms of action. These powerful assays can identify genes that confer sensitivity or resistance to specific therapeutics. The reliability of these screens hinges on several critical experimental parameters. Inadequate planning for Multiplicity of Infection (MOI), library coverage, and cell numbers can lead to false positives, false negatives, and irreproducible results, ultimately compromising the screen's outcomes [14] [44]. This guide outlines detailed methodologies and calculations to optimize these parameters, framed within the context of preparing a library for a successful chemogenomic screen.

Core Parameters and Their Experimental Determination

Multiplicity of Infection (MOI)

Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) is defined as the ratio of transducing viral particles to target cells. Optimizing MOI is crucial to ensure that a high percentage of cells receive a single genetic perturbation without multiple integrations, which can confound results and enhance cellular stress.

Experimental Protocol for MOI Determination:

- Cell Preparation: Seed the target cells (e.g., RPE1-hTERT p53−/−) at a density that will be 20-30% confluent at the time of transduction. Prepare multiple wells for a range of viral dilutions [14].

- Viral Transduction: Serially dilute the lentiviral library stock and add it to the cells in the presence of a transduction enhancer (e.g., polybrene). A common approach is to test a range of volumes (e.g., 0.5 µL to 10 µL of virus per well) [14].

- Selection and Analysis: After 24-48 hours, replace the medium with a selection medium containing an antibiotic (e.g., puromycin). The percentage of transduced cells is determined by the survival rate in the selection media compared to a non-transduced control.

- Calculation and Optimization: The optimal MOI is the dilution that results in a transduction efficiency between 30% and 50%. This low percentage minimizes the chance of a single cell incorporating multiple sgRNAs. The MOI is calculated using the formula:

-log(% Non-transduced Cells / 100)[14]. For a transduction efficiency of 40%, the MOI would be-log(60/100) ≈ 0.22.

Library Coverage

Library coverage refers to the number of cells representing each sgRNA in a pooled library. High coverage is necessary to capture the full diversity of the library and avoid the stochastic loss of sgRNAs during screen expansion.

Experimental Protocol for Ensuring Sufficient Coverage:

- Define Library Size: Determine the total number of unique sgRNAs in your library. For example, the TKOv3 library contains 70,948 sgRNAs targeting 18,053 genes [14].