Leveraging Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms for Advanced Chemogenomics Research in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms into chemogenomics research.

Leveraging Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms for Advanced Chemogenomics Research in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms into chemogenomics research. It explores the foundational principles of modern NGS technologies, details methodological applications for linking genomic data with drug response, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers comparative validation strategies. With a focus on multiomics integration, AI-powered analytics, and advanced tumor models, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accelerate therapeutic discovery and precision medicine.

The Evolution and Core Principles of NGS for Chemogenomics

The evolution of DNA sequencing technology represents one of the most transformative progressions in modern biological science, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of biomedical research and drug discovery. From its humble beginnings with laborious manual methods to today's massively parallel technologies, sequencing has advanced at a pace that dramatically outpaces Moore's Law, enabling applications once confined to science fiction [1]. This technological revolution is particularly pivotal for chemogenomics research, where understanding the intricate relationships between genomic features and compound sensitivity is essential for advancing targeted therapies and personalized medicine. The journey from first-generation methods to next-generation sequencing (NGS) has not only enhanced our technical capabilities but has fundamentally altered the kinds of scientific questions researchers can pursue, moving from single-gene investigations to system-wide genomic analyses [2].

The impact on drug development has been profound. Modern sequencing platforms allow researchers to rapidly identify disease-associated genetic variants, characterize tumor heterogeneity, elucidate drug resistance mechanisms, and map complex biological pathways at unprecedented resolution [3] [2]. For chemogenomics—which seeks to correlate genomic variation with drug response—the availability of high-throughput, cost-effective sequencing has enabled the creation of comprehensive datasets linking genetic profiles to compound sensitivity across diverse cellular models, including next-generation tumor organoids that closely mimic patient physiology [4]. This review traces the technological evolution through distinct generations of sequencing technology, highlighting key innovations, methodological principles, and applications that have positioned NGS as an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery pipelines.

The Generational Shift in Sequencing Technology

DNA sequencing technologies have evolved through distinct generations, each marked by fundamental improvements in throughput, cost, and scalability. This progression is categorized into three main generations, with the second and third generations collectively referred to as next-generation sequencing (NGS) due to their massive parallelization capabilities [3] [5].

Table 1: Evolution of DNA Sequencing Technologies

| Generation | Key Technologies | Maximum Read Length | Throughput per Run | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Sanger Sequencing (dideoxy chain-termination) [6], Maxam-Gilbert (chemical cleavage) [5] | ~1,000 bases [5] | ~1 Megabase [1] | High accuracy, simple data analysis | Low throughput, high cost per base |

| Second Generation | 454 Pyrosequencing [6], Illumina (SBS) [3], Ion Torrent [7], SOLiD [3] | 36-400 bases [3] | Up to multiple Terabases [2] | Massive parallelism, low cost per base | Short reads, PCR amplification bias |

| Third Generation | PacBio SMRT [3], Oxford Nanopore [6] | 10,000-30,000+ bases [3] | Varies by platform | Long reads, real-time sequencing, no amplification | Higher error rate, higher cost per instrument |

First Generation: Foundations of Sequencing

The first generation of DNA sequencing was pioneered by two parallel methodological developments: the Maxam-Gilbert chemical cleavage method and Sanger chain-termination sequencing [5] [1]. Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam published their chemical sequencing technique in 1973, which involved radioactively labeling DNA fragments followed by base-specific chemical cleavage [8]. The resulting fragments were separated by gel electrophoresis and visualized via autoradiography to deduce the DNA sequence [1]. While revolutionary for its time, this method was technically challenging and utilized hazardous chemicals.

In 1977, Frederick Sanger introduced the dideoxy chain-termination method, which would become the dominant sequencing technology for the following three decades [6] [7]. This technique utilizes dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs), which lack the 3′-hydroxyl group necessary for DNA chain elongation [1]. When incorporated by DNA polymerase, these analogues terminate DNA synthesis randomly, producing fragments of varying lengths that could be separated by size to reveal the sequence [6]. Sanger's method proved more accessible and scalable than Maxam-Gilbert, leading to its widespread adoption [1]. The subsequent automation of Sanger sequencing with fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and capillary electrophoresis in instruments like the ABI 370 marked a critical advancement, enabling higher throughput and setting the stage for large-scale projects like the Human Genome Project [6] [5].

Second Generation: The Rise of Massively Parallel Sequencing

The transition to second-generation sequencing was characterized by a fundamental shift from capillary-based methods to massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [3]. This "next-generation" sequencing began with the introduction of pyrosequencing by Mostafa Ronaghi, Mathias Uhlen, and Pȧl Nyŕen in 1996 [6] [7]. This sequencing-by-synthesis technology measured luminescence generated during pyrophosphate release when nucleotides were incorporated [6]. The commercial implementation of this technology in the Roche 454 system in 2005 marked the arrival of the first NGS platform, achieving unprecedented throughput compared to Sanger methods [7].

The subsequent development and refinement of various NGS platforms dramatically accelerated genomic research. The Illumina sequencing platform, based on reversible dye-terminator chemistry, emerged as the market leader [3] [2]. Ion Torrent introduced semiconductor sequencing, detecting hydrogen ions released during nucleotide incorporation rather than using optical detection [7]. The SOLiD system employed a unique sequencing-by-ligation approach with di-base fluorescent probes [3]. Despite their technical differences, all second-generation platforms share a common workflow involving library preparation, clonal amplification (via emulsion PCR or bridge amplification), and parallel sequencing of dense arrays of DNA clusters [6] [3]. This parallelization enabled monumental increases in daily data output—from approximately 1 Megabase with automated Sanger sequencers to multiple Terabases with modern Illumina systems [1] [2].

Third Generation: Single-Molecule and Real-Time Sequencing

Third-generation sequencing technologies emerged to address key limitations of second-generation methods, particularly short read lengths and amplification biases. These platforms are defined by their ability to sequence single DNA molecules in real time without prior amplification [9]. The two most prominent technologies are Pacific Biosciences' Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore sequencing [3] [9].

PacBio SMRT sequencing utilizes specialized flow cells containing thousands of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)—nanophotonic nanostructures that confine observation volumes to the single-molecule level [3] [1]. Each ZMW contains a single DNA polymerase enzyme immobilized at the bottom, incorporating fluorescently labeled nucleotides. As nucleotides are incorporated, the fluorescent signal is detected in real time, enabling direct observation of the synthesis process [7] [1]. This approach produces exceptionally long reads (averaging 10,000-25,000 bases), which are invaluable for genome assembly, structural variant detection, and resolving complex genomic regions [3].

Oxford Nanopore technologies employ a fundamentally different mechanism based on electrical signal detection. Single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules are passed through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane [6] [1]. As each nucleotide passes through the pore, it causes characteristic disruptions in ionic current that can be decoded to determine the sequence [7] [1]. Nanopore devices like the MiniON are notably compact and portable, enabling field applications and rapid deployment [9] [7]. Both third-generation technologies offer the advantage of real-time data analysis and the ability to detect epigenetic modifications without specialized preparation [3].

Technical Workflows and Methodologies

Core NGS Workflow

Despite the diversity of NGS platforms, most follow a similar three-step workflow consisting of library preparation, clonal amplification and sequencing, and data analysis [6] [2]. Each stage involves critical technical decisions that influence data quality and applicability to specific research questions.

Library Preparation: DNA is fragmented—either mechanically or enzymatically—to appropriate sizes for the specific platform [6]. Platform-specific adapter sequences are ligated to both ends of the fragments, enabling hybridization to the sequencing matrix and providing priming sites for both amplification and sequencing [6] [2]. For targeted sequencing approaches, additional enrichment steps using hybrid capture or amplicon-based strategies are employed to isolate regions of interest [2].

Clonal Amplification and Sequencing: Except for some third-generation approaches, most NGS platforms require in vitro cloning of the library fragments to generate sufficient signal for detection [6]. This is typically achieved through emulsion PCR (used by 454, Ion Torrent, and SOLiD) or bridge amplification (used by Illumina) [3]. The amplified DNA fragments are then sequenced using platform-specific detection methods, whether based on fluorescent detection (Illumina), pH sensing (Ion Torrent), or electrical current changes (Nanopore) [3] [1].

Data Analysis and Alignment: The raw data output from NGS platforms consists of short sequence reads (for second-generation) or longer error-prone reads (for third-generation) that must be processed through specialized bioinformatics pipelines [3]. Typical steps include quality filtering, read alignment to a reference genome, variant calling, and functional annotation [3] [2]. The massive volume of NGS data—ranging from gigabytes to terabytes per experiment—requires substantial computational resources and specialized algorithms [3].

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Illumina Sequencing-by-Synthesis Protocol

The Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis method represents the most widely adopted NGS technology [3] [2]. The detailed protocol consists of:

Library Preparation: Genomic DNA is fragmented to 200-500bp using acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation. After end-repair and A-tailing, indexed adapter sequences are ligated to both ends of the fragments. The final library is purified using SPRI bead-based cleanups and quantified via qPCR [2].

Cluster Amplification: The library is denatured and loaded onto a flow cell where fragments hybridize to complementary lawn oligonucleotides. Through bridge amplification, each fragment is clonally amplified into distinct clusters, generating approximately 1,000 identical copies per cluster to ensure sufficient signal strength during sequencing [3] [2].

Sequencing Chemistry: The flow cell is placed in the sequencer where reversible terminator nucleotides containing cleavable fluorescent dyes are incorporated one base at a time. After each incorporation, the flow cell is imaged to determine the identity of the base at each cluster. The terminator group and fluorescent dye are then cleaved, allowing the next cycle to begin [3] [2]. This process continues for the specified read length, typically 50-300 cycles depending on the application and platform.

Data Processing: The instrument's software performs base calling, demultiplexing based on index sequences, and generates FASTQ files containing sequence reads and quality scores for downstream analysis [2].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Chemogenomics

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has become an essential method in chemogenomics for characterizing tumor heterogeneity and drug response [2]. A typical droplet-based scRNA-seq protocol includes:

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation: Viable single-cell suspensions are prepared from tumor organoids or primary tissue using enzymatic digestion and mechanical dissociation. Cell viability and concentration are critical parameters, typically requiring >85% viability and optimal concentration for the specific platform [4].

Droplet-Based Partitioning: Cells are co-encapsulated with barcoded beads in nanoliter-scale droplets using microfluidic devices. Each bead contains oligonucleotides with a cell barcode (unique to each cell), unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to label individual mRNA molecules, and a poly(dT) sequence for mRNA capture [2].

Library Preparation: Within each droplet, cells are lysed and mRNA is hybridized to the barcoded beads. After droplet breakage, reverse transcription is performed to generate cDNA with cell-specific barcodes. The cDNA is then amplified and processed into a sequencing library following standard protocols [2].

Sequencing and Analysis: Libraries are sequenced on an appropriate NGS platform (typically Illumina). The resulting data is processed through specialized pipelines that perform demultiplexing, cell barcode assignment, UMI counting, and gene expression quantification to generate a digital expression matrix for downstream analysis [2].

Sequencing in Chemogenomics Research

Applications in Drug Discovery

Next-generation sequencing has become foundational to modern chemogenomics research, enabling comprehensive mapping of relationships between genomic features and compound sensitivity [4]. Key applications include:

Drug Target Identification: Whole-genome and exome sequencing of patient cohorts enables identification of somatic mutations and copy number alterations driving disease pathogenesis, highlighting potential therapeutic targets [3] [2]. Integration with functional genomics approaches like CRISPR screening further prioritizes targets based on essentiality and druggability [2].

Biomarker Discovery: NGS facilitates the identification of predictive biomarkers for drug response by correlating genomic variants with sensitivity data across cell line panels or patient-derived models [4]. For example, sequencing of cancer models treated with compound libraries can reveal genetic features associated with sensitivity or resistance [4].

Mechanism of Action Studies: Profiling gene expression changes following drug treatment using RNA-Seq provides insights into compound mechanism of action and secondary effects [2]. The digital nature of NGS-based expression profiling offers a broader dynamic range compared to microarrays, enabling detection of subtle transcriptional changes [2].

Pharmacogenomics: Sequencing of genes involved in drug metabolism and transport helps identify variants affecting pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, supporting personalized dosing and toxicity prediction [3].

Advanced Chemogenomic Models

The integration of NGS with sophisticated disease models has dramatically enhanced the predictive power of chemogenomic studies:

Patient-Derived Organoids: 3D patient-derived tumor organoids retain key characteristics of original tumors, including cell-cell interactions, tumor heterogeneity, and drug response profiles [4]. Sequencing these models alongside primary tissue enables in-depth studies of resistance mechanisms and combination therapy strategies [4].

Liquid Biopsy Applications: Sequencing of cell-free DNA from patient blood samples provides a non-invasive approach for monitoring treatment response, tracking resistance mutations, and detecting minimal residual disease [7] [2]. The high sensitivity of NGS enables detection of rare variants in complex mixtures [2].

Single-Cell Chemogenomics: Combining single-cell sequencing with compound screening allows researchers to map drug responses at cellular resolution, revealing how pre-existing cellular heterogeneity influences treatment outcomes and resistance development [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-based Chemogenomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep, NEBNext Ultra II | Fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, library amplification | Preparation of sequencing libraries from diverse sample types |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina Nextera Flex, Twist Target Enrichment, IDT xGen Panels | Selective capture of genomic regions of interest | Focused sequencing of cancer gene panels, pharmacogenes |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody, Parse Biosciences | Partitioning and barcoding of single cells | Characterization of tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina SBS Chemistry, PacBio SMRTbell, Oxford Nanopore Kits | Nucleotides, enzymes, and buffers for sequencing reactions | Platform-specific sequencing of prepared libraries |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK, DRAGEN, Cell Ranger, Seurat | Raw data processing, variant calling, expression analysis | Data analysis and interpretation for chemogenomic insights |

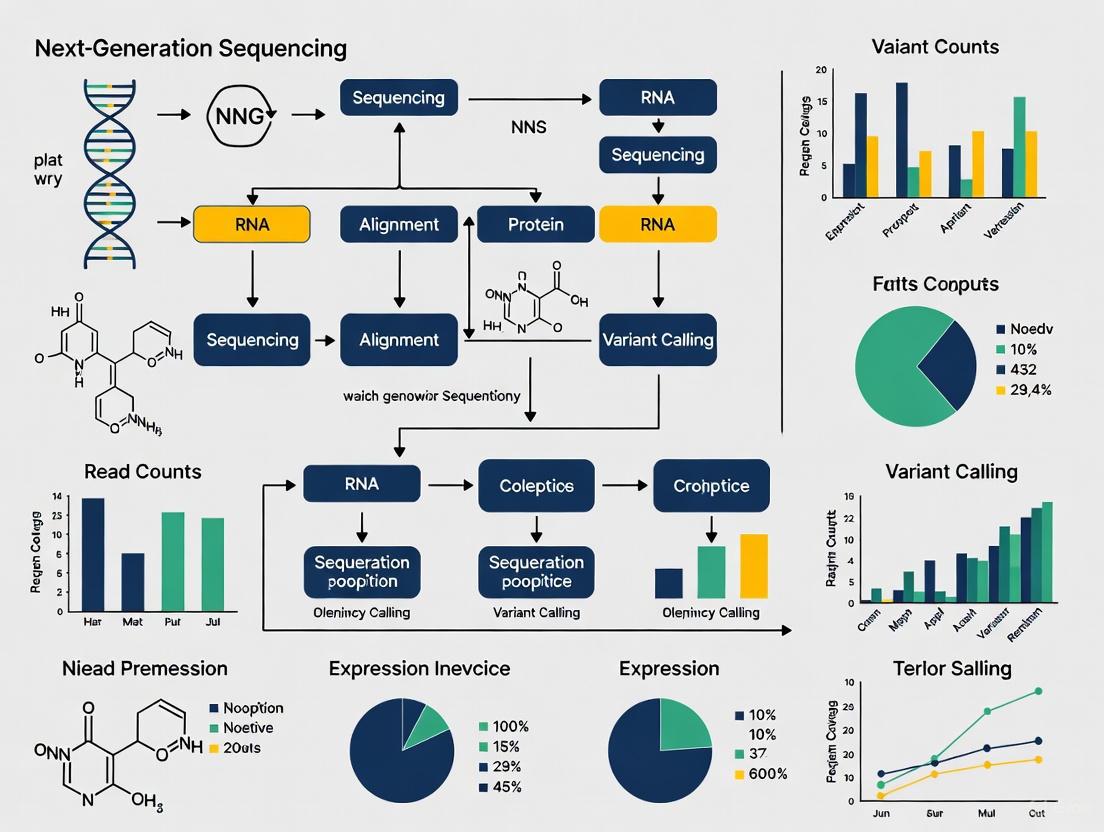

Visualization of Key Sequencing Methodologies

The evolution of DNA sequencing from the first gel-based methods to today's massively parallel technologies represents one of the most significant technological revolutions in modern biology. Each generational shift has brought exponential increases in throughput and corresponding reductions in cost, making comprehensive genomic analysis accessible to individual laboratories [1]. For chemogenomics research, this progression has been particularly transformative, enabling the systematic mapping of relationships between genomic features and compound sensitivity at unprecedented scale and resolution [4].

Looking ahead, several emerging trends are poised to further reshape the sequencing landscape and its applications in drug discovery. The continued development of long-read technologies will enhance our ability to resolve complex genomic regions and detect structural variations with implications for drug target identification [3]. Spatial transcriptomics approaches are adding geographical context to gene expression data, revealing how tissue microenvironment influences drug response [2]. The integration of multi-omics datasets—combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data—will provide more comprehensive views of cellular states and their modulation by therapeutic compounds [2]. Additionally, advances in portable sequencing technologies will potentially enable point-of-care genomic analysis and real-time monitoring of disease evolution [7].

For chemogenomics research, the future will likely focus on increasingly sophisticated models that better recapitulate human disease, including patient-derived organoids, organs-on-chips, and complex coculture systems [4]. Coupled with ongoing improvements in sequencing cost and throughput, these models will enable more predictive compound screening and mechanism of action studies. The convergence of artificial intelligence with large-scale sequencing data holds particular promise for identifying complex patterns predictive of drug response and for designing novel therapeutic combinations [4] [2].

In conclusion, the journey from Sanger sequencing to massively parallel technologies has fundamentally transformed our approach to biological research and drug development. Each technological generation has built upon its predecessor, addressing limitations while opening new possibilities for scientific discovery. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new layers of biological complexity and provide increasingly powerful tools for the chemogenomics community in its mission to develop more effective, personalized therapeutics.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics research by enabling high-throughput analysis of genetic responses to chemical compounds, thereby accelerating drug discovery and development. This technical guide deconstructs the modern NGS workflow into its fundamental components, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing these technologies in precision medicine applications. We examine each operational phase from nucleic acid extraction to computational analysis, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints, experimental design considerations, and platform selection criteria essential for robust chemogenomics investigations. The integration of advanced sequencing technologies with bioinformatics pipelines has created unprecedented opportunities for identifying novel drug targets, understanding mechanisms of action, and developing personalized therapeutic strategies based on individual genetic profiles.

Next-generation sequencing technologies have transformed molecular biology research by enabling massive parallel sequencing of DNA and RNA fragments, providing comprehensive insights into genetic variations, gene expression patterns, and epigenetic modifications. In chemogenomics research, which explores the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, NGS serves as a foundational technology for identifying novel drug targets, understanding mechanisms of drug action, and predicting compound efficacy and toxicity. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, which was time-intensive and costly, NGS allows simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, democratizing genomic research and enabling large-scale projects [10]. The strategic implementation of NGS workflows in chemogenomics provides researchers with powerful tools for linking genetic information with compound activity, thereby facilitating more efficient drug development pipelines and advancing precision medicine initiatives.

The Four Pillars of the NGS Workflow

The standard NGS workflow comprises four critical stages that transform biological samples into interpretable genetic data. Each stage requires careful execution and quality control to ensure reliable results, particularly in chemogenomics applications where subtle genetic variations can significantly impact compound-target interactions.

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quality Control

The NGS workflow begins with the isolation of genetic material from various sample types, including bulk tissue, individual cells, or biofluids [11]. The quality of this initial extraction directly influences all subsequent steps and ultimately determines the reliability of final results. For chemogenomics research, where experiments often involve treated cell lines or tissue samples, maintaining nucleic acid integrity is particularly crucial for accurately assessing transcriptional responses to chemical compounds.

Key Considerations:

- Yield: Most library preparation methods require nanograms to micrograms of DNA or cDNA (from RNA). This is especially important when working with low biomass samples, such as limited patient specimens often used in pharmacogenomics studies [12].

- Purity: Contaminants from nucleic acid isolation kits (phenol, ethanol) or biological materials (heparin, humic acid) can inhibit library preparation. Effective isolation methods must include steps for removing these inhibitors [12].

- Quality: DNA should be of high molecular weight and intact, while RNA requires minimized degradation during storage and preparation. Specific isolation methods should be selected if starting material is known to be fragmented [12].

Quality control assessment typically employs UV spectrophotometry for purity evaluation and fluorometric methods for accurate nucleic acid quantitation [11]. These measurements establish the suitability of samples for proceeding to library preparation and help prevent reagent waste and sequencing failures.

Library Preparation

Library preparation converts purified nucleic acids into formats compatible with sequencing platforms through fragmentation and adapter ligation [11]. This critical step determines what genomic regions will be sequenced and how efficiently they can be decoded. For chemogenomics applications, library preparation strategies must be tailored to specific research questions, whether examining whole transcriptome responses to compound treatment or targeted sequencing of specific gene families.

Core Steps:

- Fragmentation: DNA or cDNA is fragmented into appropriate sizes for the sequencing platform.

- Adapter Ligation: Short oligonucleotide adapters are attached to fragment ends, enabling binding to sequencing flow cells and facilitating amplification.

- Indexing: Unique barcodes are added to samples, allowing multiplexing (pooling) of multiple libraries for simultaneous sequencing, significantly reducing per-sample costs [12].

Enrichment Options: As an alternative to whole genome sequencing, targeted approaches sequence specific genomic regions of interest:

- Amplicon Sequencing: Enrichment during library preparation using targeted PCR amplification.

- Hybridization Capture: Enrichment after library preparation using probe hybridization to capture regions of interest [12].

These targeted approaches are particularly valuable in chemogenomics for focusing on gene families relevant to drug metabolism (e.g., cytochrome P450 genes) or compound targets (e.g., kinase families).

Sequencing

The sequencing phase involves determining the nucleotide sequence of prepared libraries using specialized platforms. Different sequencing methods offer distinct advantages in throughput, read length, and application suitability. The selection of an appropriate sequencing platform represents a critical decision point in experimental design, with significant implications for data quality and interpretation in chemogenomics studies.

Primary Sequencing Methods:

- Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS): This dominant approach, utilized by Illumina platforms, detects single bases as they are incorporated into growing DNA strands [11]. The recently introduced XLEAP-SBS chemistry enhances speed and quality while reducing error rates [11].

- Nanopore Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore Technologies measures changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores, enabling real-time, portable sequencing with exceptionally long reads [10].

- Sequencing by Expansion (SBX): Roche's emerging technology uses biochemical conversion to encode DNA into Xpandomers (50x longer than target DNA), enabling highly accurate single-molecule nanopore sequencing using CMOS-based sensors [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Leading NGS Platforms (2025)

| Company | Platform | Key Features | Throughput | Primary Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | NovaSeq X Series | XLEAP-SBS chemistry, high accuracy | 20,000+ genomes/year | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptomics, epigenomics [10] |

| Element Biosciences | AVITI24 | Innovation roadmap with direct in-sample sequencing | ~$60M revenue (2024) | Library-prep free transcriptomics, targeted RNA sequencing [13] |

| Ultima Genomics | UG 100 Solaris | Simplified workflows, low cost per genome | 10-12 billion reads/wafer | Large-scale compound screening, population studies [13] |

| Oxford Nanopore | MinION | Real-time sequencing, long reads, portable | Scalable capabilities | Rapid pathogen identification, field applications [13] |

| MGI Tech | DNBSEQ-T1+ | Q40 accuracy, 24-hour workflow | 25-1,200 Gb | High-throughput genotyping, expression profiling [13] |

| PacBio | Revio | Long-read sequencing, structural variant detection | N/A | Complex genome assembly, isoform sequencing [10] |

Data Analysis

The final workflow phase transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights through computational analysis. This multi-step process requires specialized bioinformatics tools and significant computational resources, particularly challenging in chemogenomics where integrating chemical and genetic data adds analytical complexity.

Read Processing:

- Base Calling: Identification of specific nucleotides at each position in sequencing reads, accompanied by quality scores indicating confidence levels [12].

- Adapter Trimming: Removal of artificial adapter sequences added during library preparation.

- Demultiplexing: Separation and grouping of reads by sample-specific barcodes [12].

Sequence Analysis:

- Alignment/Mapping: Positioning sequence reads against reference genomes or databases.

- Variant Calling: Identification of genetic variations (SNPs, indels) relative to reference.

- Advanced Analyses: Gene expression quantification, pathway analysis, epigenetic modification detection, and integration with chemical data in chemogenomics applications [12].

The growing accessibility of bioinformatics tools through user-friendly interfaces and automated workflows has democratized NGS data analysis, allowing researchers without extensive computational backgrounds to derive meaningful insights from complex datasets [11].

NGS Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive NGS workflow highlighting critical quality control checkpoints and chemogenomics integration.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS workflows in chemogenomics research requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each procedural step. The following table catalogizes essential solutions with specific functions in the experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in NGS Workflow | Application in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Cell/Tissue-specific isolation kits | Lysing cells/tissues to capture genetic material while maximizing yield, purity, and quality [12] | Isolation of intact RNA from compound-treated cells for transcriptomics |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina, Ion Torrent, MGI-compatible kits | Converting nucleic acids to platform-specific libraries through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and barcoding [12] | Preparation of strand-specific libraries for accurate transcript quantification |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Hybridization capture kits, Amplicon sequencing panels | Selecting specific genomic regions (e.g., exomes, gene panels) instead of whole genomes [12] | Focusing on pharmacogenomics genes or drug target families |

| Sequencing Consumables | Flow cells, SBS chemistry kits, Nanopores | Platform-specific reagents that enable the sequencing reaction and detection [11] | High-throughput screening of multiple compound conditions |

| Quality Control Tools | Fluorometric assays, Bioanalyzer chips | Assessing nucleic acid quantity, quality, and library preparation success before sequencing [11] | Ensuring sample quality across experimental replicates |

| Bioinformatics Software | Variant callers, Alignment algorithms, Expression analyzers | Processing raw data, identifying variations, and interpreting biological significance [12] | Connecting genetic variations with compound sensitivity/resistance |

Advanced Methodologies for Chemogenomics Research

Single-Cell and Spatial Genomics in Compound Screening

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative methodology in chemogenomics by enabling researchers to profile transcriptional responses to chemical compounds at individual cell resolution. This approach reveals cell-to-cell heterogeneity in drug responses and identifies rare cell populations that may drive resistance mechanisms. Spatial transcriptomics further enhances these analyses by preserving tissue architecture while mapping gene expression patterns, providing critical context for understanding compound distribution and effects within complex tissues [10]. These technologies are particularly valuable for:

- Identifying distinct cellular subpopulations with differential compound sensitivity

- Mapping drug penetration and metabolism within tissue microenvironments

- Uncovering heterogeneous mechanisms of action within complex cell populations

Multi-Omics Integration for Comprehensive Compound Profiling

Multi-omics approaches combine NGS data with other molecular profiling technologies to generate comprehensive views of compound effects on biological systems. By integrating genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, researchers can establish complete mechanistic pictures of compound activities [10]. This integrated framework is particularly powerful for:

- Linking genetic variations to compound-induced changes across multiple molecular layers

- Identifying biomarkers predictive of compound efficacy or toxicity

- Understanding how epigenetic modifications influence compound sensitivity

- Mapping compound effects on metabolic pathways through integrated genomics-metabolomics

AI-Enhanced Analysis of Chemogenomic Data

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms have become indispensable for interpreting complex NGS datasets in chemogenomics. These computational approaches can identify subtle patterns across large compound-genetic interaction datasets that might escape conventional statistical methods [10]. Key applications include:

- Variant Calling: Deep learning tools like Google's DeepVariant achieve superior accuracy in identifying genetic variations from NGS data [10].

- Compound Response Prediction: ML models analyze genetic features to forecast individual responses to specific compounds.

- Target Identification: AI algorithms integrate multi-omics data to prioritize novel drug targets based on genetic dependencies.

- Mechanism of Action Determination: Pattern recognition in transcriptional responses classifies compounds by their biological mechanisms.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Technologies

The NGS landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to further transform chemogenomics research. The United States NGS market is projected to grow from $3.88 billion in 2024 to $16.57 billion by 2033, representing a compound annual growth rate of 17.5% [14]. This expansion reflects both technological advances and expanding applications across biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Key Technological Trends:

- Ultra-Low-Cost Sequencing: Platforms like Ultima Genomics' UG 100 Solaris are driving costs down to approximately $80 per genome while increasing output to 10-12 billion reads per wafer [13].

- Long-Read Advancements: Oxford Nanopore and PacBio technologies continue to improve read length and accuracy, enabling more comprehensive characterization of structural variations and complex genomic regions [10].

- Integrated Workflow Solutions: Companies like Revvity and Element Biosciences are collaborating to develop comprehensive in vitro diagnostic (IVD) workflow solutions, streamlining implementation in regulated environments [13].

- Real-Time Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore's portable MinION device provides scalable, real-time sequencing capabilities suitable for field applications and rapid diagnostics [13].

Computational and Analytical Innovations:

- Cloud-Based Genomics: Platforms like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Genomics provide scalable infrastructure for storing and analyzing massive NGS datasets while ensuring compliance with regulatory frameworks such as HIPAA and GDPR [10].

- AI-Driven Discovery: The integration of artificial intelligence with multi-omics data is enhancing predictive modeling of compound-target interactions and accelerating therapeutic discovery [10].

- CRISPR-Enhanced Functional Genomics: CRISPR screens combined with NGS readouts enable high-throughput interrogation of gene function and compound mechanisms across the entire genome [10].

These technological advances are progressively removing barriers between sequencing and clinical application, positioning NGS as an increasingly central technology in personalized medicine and rational drug design. As costs continue to decline and analytical capabilities expand, NGS workflows will become further integrated into standard chemogenomics research pipelines, enabling more comprehensive and predictive compound profiling.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, enabling the parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments and providing comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, and gene expression profiles [3]. In chemogenomics research, which utilizes genomic tools to discover new drug targets and understand drug mechanisms, selecting the appropriate NGS platform is paramount. The choice directly influences the detection of somatic mutations in cancer driver genes, the characterization of complex microbial communities in the microbiome, and the identification of rare genetic variants that may predict drug response [15] [3]. The core specifications of throughput, read length, and error profile form a critical decision-making framework, determining the resolution, accuracy, and scale at which chemogenomic inquiries can be pursued. This guide provides a detailed technical comparison of these specifications to inform platform selection for advanced drug discovery and development applications.

Core NGS Platform Specifications

Definition and Impact of Key Specifications

The performance of any NGS platform is defined by three primary technical specifications, each with direct implications for experimental design and data quality in chemogenomics:

- Throughput refers to the amount of data generated in a single sequencing run, typically measured in gigabases (Gb) or terabases (Tb) [16]. High-throughput systems are essential for large-scale projects like population studies or comprehensive cancer genomic profiling, whereas lower-throughput benchtop machines are suited for targeted gene panels or smaller pilot studies [16] [17].

- Read Length indicates the average number of consecutive bases determined from a single DNA fragment [16]. Short-read technologies (50-300 base pairs) are effective for variant calling and gene expression quantification [16] [18]. Long-read technologies (thousands to tens of thousands of base pairs) are indispensable for resolving repetitive genomic regions, detecting large structural variants, and performing de novo genome assembly without a reference [18] [19].

- Error Profile describes the type and frequency of sequencing inaccuracies. Unlike the uniform accuracy of Sanger sequencing (0.001% error rate), NGS platforms exhibit distinct error patterns [20]. These include substitution errors (incorrect base incorporated), insertions, and deletions (collectively "indels"), which are not random but follow patterns specific to the underlying sequencing chemistry [15]. Understanding these profiles is critical for detecting low-frequency variants, such as subclonal mutations in tumors, which is a central task in cancer chemogenomics [15].

Comparative Analysis of Major NGS Platforms

The following table summarizes the key specifications of major sequencing platforms available, highlighting their suitability for different chemogenomic applications.

Table 1: Key Specifications of Major NGS Platforms

| Platform (Category) | Typical Throughput per Run | Typical Read Length | Primary Error Profile | Key Chemogenomics Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X (Short-read) | Up to 16 Tb [17] [19] | 50-300 bp [16] [3] | Substitution errors (~0.1%-0.8%); particularly in AT/CG-rich regions [20] [3] | Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), large-scale transcriptomics (RNA-Seq), population studies [16] |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T7 (Short-read) | High (comparable to Illumina) [18] | Short-read [18] | Accurate reads, cost-effective for polishing [18] | Cost-effective alternative for large-scale WGS and targeted sequencing [18] |

| PacBio Revio (HiFi) (Long-read) | High (leverages SMRTbell templates) [19] [3] | 10-25 kb (High-Fidelity) [19] | Random errors, suppressed to <0.1% (Q30) via circular consensus sequencing [19] | Detecting structural variants, haplotype phasing, de novo assembly of complex genomes [18] [19] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) (Long-read) | Varies by device (MinION to PromethION) [18] | Average 10-30 kb (can be much longer) [3] | Historically higher indel rates, especially in homopolymers; Duplex reads now achieve >Q30 (>99.9% accuracy) [19] | Real-time sequencing, metagenomic analysis, direct detection of epigenetic modifications [18] [3] |

| Ion Torrent (e.g., PGM) (Short-read) | Up to 10 Gb [21] | 200-600 bp [21] | High error rate (~1.78%); poor accuracy in homopolymer regions [20] [3] | Rapid pathogen identification in diagnostic settings [21] |

NGS Workflow and Experimental Protocols

A successful NGS experiment in chemogenomics requires meticulous execution of a multi-stage workflow. The following diagram illustrates the key steps, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Figure 1: The generalized NGS workflow, from sample to sequence.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Workflow Steps

1. Nucleic Acid Extraction The protocol is tailored to the sample source (e.g., tissue, blood, microbial cultures) and study type [20]. For chemogenomic studies using patient-derived tumor organoids, ensuring high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA is critical for representing the original tumor's genetic landscape [4]. Environmental samples or complex microbiomes may require pre-treatment to remove impurities that inhibit downstream reactions [20].

2. Library Construction This process prepares the nucleic acids for sequencing.

- DNA Library Preparation: Isolated DNA is fragmented to a specific size (e.g., 150-800 bp) via enzymatic digestion, sonication, or nebulization [16] [20]. Specialized long-read kits (e.g., Illumina's Complete Long Reads, Element's LoopSeq) use transposase enzymes or barcoding to reconstruct long sequences from short-read data [17].

- RNA Library Preparation: mRNA is captured from total RNA, fragmented, and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) before adapter ligation [20].

- Adapter Ligation: Short, known DNA sequences (adapters) are ligated to fragment ends. These allow binding to the flow cell, provide primer binding sites, and often include unique molecular barcodes for multiplexing—pooling multiple samples in a single run to reduce costs [16].

3. Template Amplification Library fragments are clonally amplified to generate sufficient signal for detection.

- Emulsion PCR (ePCR): Used by Roche/454 and Ion Torrent. DNA is immobilized on beads and amplified in water-in-oil emulsion droplets, ensuring one molecule per bead [20] [3].

- Bridge Amplification: Used by Illumina. DNA fragments bind to primers covalently attached to a glass flow cell and are amplified into clusters through repeated cycles of extension and denaturation [16] [21].

4. Sequencing and Imaging The amplified library is sequenced using platform-specific biochemistry.

- Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS): The predominant method (Illumina). Fluorescently labeled, reversible terminator nucleotides are added one at a time. After each incorporation, a camera captures the fluorescent signal, the terminator is cleaved, and the cycle repeats [16] [21].

- Semiconductor Sequencing: Used by Ion Torrent. Incorporation of a nucleotide releases a hydrogen ion, causing a detectable pH change. This method converts chemical information directly to a digital signal without optics [16] [21].

- Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing: Used by PacBio. A DNA polymerase synthesizes a strand in real-time within a zero-mode waveguide (ZMW), with incorporated nucleotides detected by their fluorescent tag [19] [3].

- Nanopore Sequencing: Used by Oxford Nanopore. A single strand of DNA is electrophoretically driven through a protein nanopore. Each base causes a characteristic disruption in ionic current, which is decoded into a sequence in real-time [18] [3].

Error Analysis and Quality Control

Understanding and Mitigating Sequencing Errors

Different NGS chemistries introduce distinct error types, which must be accounted for in data analysis, especially when detecting low-frequency variants for pharmacogenomics.

- Substitution Errors: Illumina platforms are prone to substitution errors, particularly A>G/T>C changes and context-dependent C>T/G>A errors, with rates ranging from 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁴ after computational suppression [15]. These can confound single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection.

- Indel Errors in Homopolymers: Roche/454 and Ion Torrent platforms struggle with homopolymer regions (runs of identical bases), leading to insertion and deletion errors due to inefficient determination of homopolymer length [20] [3].

- Template Amplification Artifacts: PCR amplification during library prep can introduce several artifacts, including polymerase base incorporation errors, artificial recombination chimeras, and amplification bias (where one allele amplifies more efficiently than another), potentially leading to both false positives and false negatives [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Item | Function in NGS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA/RNA from diverse sample types (e.g., tissue, cells, biofluids) [20]. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/Assays | Mechanically or enzymatically shear DNA into random, overlapping fragments of defined size ranges optimal for the chosen platform [16] [20]. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Provide enzymes and buffers for end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation to create sequence-ready libraries [16]. |

| Unique Molecular Barcodes | Short nucleotide sequences added to samples during library prep to allow multiplexing and track reads to their original sample [16]. |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Probes designed to capture and amplify specific genomic regions of interest (e.g., cancer gene panels) from complex samples [16]. |

| PCR Enzymes (High-Fidelity) | Amplify library fragments with minimal base incorporation errors to reduce false positive variant calls [20] [15]. |

| Quality Control Assays | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, or qPCR assays to quantify and assess the size distribution of final libraries before sequencing [20]. |

Application in Chemogenomics Research

The integration of NGS into chemogenomics is powerfully exemplified by platforms that combine advanced tumor models with high-throughput screening. The following diagram outlines a modern chemogenomic workflow.

Figure 2: A chemogenomic atlas workflow integrating NGS and drug screening.

This approach, as pioneered by researchers like Dr. Benjamin Hopkins, involves creating a proprietary library of 3D patient-derived tumor organoids (PDOs) that retain the cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions of the original tumor [4]. These organoids are characterized using whole-exome and transcriptome NGS to establish their genomic baseline. In parallel, they are subjected to high-throughput screening against a library of compounds, including standard-of-care regimens and novel chemical entities [4].

The power of this platform lies in the integration of the deep genomic data (NGS) with the drug response data (screening). This creates a chemogenomic atlas that allows researchers to:

- Identify Predictive Biomarkers: Correlate specific genomic features (mutations, expression signatures) with sensitivity or resistance to particular drugs.

- Discover Rational Combination Therapies: Understand the mechanistic rationale for relapse by analyzing post-treatment genomic changes, revealing opportunities for effective drug combinations.

- Define Patient Strata: Categorize optimal patient populations for a given therapy based on their genomic profile, a cornerstone of precision medicine [4].

In such a framework, the choice of NGS platform is strategic. For instance, using PacBio HiFi or ONT duplex sequencing allows for the detection of complex structural variants and epigenetic modifications that may drive drug resistance. In contrast, the high throughput and accuracy of Illumina platforms are ideal for cost-effectively profiling the vast number of samples required to build a robust statistical model linking genotype to chemotherapeutic response.

Benchtop vs. Production-Scale Sequencers

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, providing unparalleled capabilities for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [3]. For chemogenomics research—which focuses on discovering the interactions between small molecules and biological systems to drive drug development—selecting the appropriate sequencing platform is a critical strategic decision. The choice fundamentally shapes the scale, speed, and depth of research into drug mechanisms, toxicogenomics, and pharmacogenomics.

NGS technologies have evolved rapidly, leading to two primary categories of instruments defined by their throughput, physical footprint, and operational scope: benchtop sequencers and production-scale sequencers [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these platforms, framing their capabilities and applications within the specific context of a chemogenomics research pipeline.

Platform Categories: Defining Benchtop and Production-Scale Systems

Benchtop Sequencers

Benchtop sequencers are characterized by their compact, self-contained design, operational simplicity, and accessibility for labs of all sizes [23] [24]. They bring the power of NGS in-house, eliminating dependencies on core facilities or service providers and giving researchers direct control over their sequencing projects and data privacy [23]. These systems are engineered for ease of use, often featuring preconfigured analysis workflows that enable both novice and experienced NGS users to generate data efficiently [23].

- Low-Throughput Benchtop Systems: These instruments, such as the Illumina MiSeq i100 Series, typically generate 2 to 30 gigabases (Gb) of data per run [23]. They are ideal for targeted sequencing, small-scale pilot studies, and library quality control (QC) prior to committing samples to larger, more expensive runs [23] [25].

- Mid-Throughput Benchtop Systems: Platforms like the Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 offer greater flexibility, with an output range from 10 Gb to 540 Gb [23] [26]. This expanded capability supports a wider array of applications, including whole-exome sequencing, single-cell profiling, and transcriptome analysis, making them versatile workhorses for diverse research programs [23].

Production-Scale Sequencers

Production-scale sequencers represent the pinnacle of high-throughput genomics, designed for large centers that require massive data output [26]. These systems are built to sequence hundreds to thousands of genomes per year, leveraging immense parallel sequencing capabilities to achieve the lowest cost-per-base [22].

- Key Specifications: Modern production-scale systems like the Illumina NovaSeq X can generate up to 8 terabases (Tb) and 52 billion reads in a single run using dual flow cells [26]. They are the platform of choice for applications demanding vast sequencing depth and breadth, such as large human whole-genome sequencing (WGS) projects, extensive plant and animal genomics, and population-scale studies [26].

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Representative Sequencing Platforms

| Feature | Low-Throughput Benchtop (e.g., MiSeq i100) | Mid-Throughput Benchtop (e.g., NextSeq 1000/2000) | Production-Scale (e.g., NovaSeq X) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Output | 1.5–30 Gb [23] | 10–540 Gb [23] [26] | Up to 8 Tb [26] |

| Max Reads per Run | 100 Million (single reads) [23] | 1.8 Billion (single reads) [23] | 52 Billion (dual flow cell) [26] |

| Run Time | ~4–24 hours [23] | ~8–44 hours [23] [26] | ~17–48 hours [26] |

| Max Read Length | 2 × 500 bp [23] | 2 × 300 bp [23] | 2 × 150 bp [26] |

| Key Applications | Small WGS (microbes), targeted panels, 16S rRNA [23] | Exome sequencing, single-cell, RNA-seq, methylation [23] | Large WGS (human, plant, animal) [26] |

| Typical Footprint | Benchtop | Benchtop | Production-scale (large instrument) |

Technical Comparison and Workflow Integration

Data Output, Speed, and Flexibility

The choice between benchtop and production-scale systems often involves a trade-off between throughput, turnaround time, and operational flexibility.

- Benchtop systems excel in speed and adaptability. The Illumina MiSeq i100, for example, can deliver results in as little as four hours, enabling same-day data analysis [23] [24]. This rapid turnaround is invaluable in chemogenomics for time-critical applications, such as checking the success of a CRISPR screen or validating a candidate drug target. A 2025 study demonstrated the flexibility of the AVITI benchtop system, achieving >30x human WGS in under 12 hours for rapid applications, and also supporting large-insert libraries (>1kb) for improved genome coverage and variant calling accuracy [27].

- Production-scale systems prioritize data volume and cost-efficiency. While their runs take longer (up to 48 hours), the sheer amount of data they produce per run drives down the cost-per-genome, making large-scale projects economically feasible [26] [28]. This is essential for chemogenomics initiatives aimed at screening vast compound libraries across hundreds of cell lines or conducting extensive pharmacogenomic studies.

Data Quality and Accuracy

Data quality is paramount for identifying subtle genetic variants in chemogenomics studies. The Illumina platform is widely recognized for its high accuracy, with most of its systems producing >90% of bases above Q30 [23] [24]. This score denotes a base-calling accuracy of 99.9%, which is a community standard for high-quality data [28]. Other technologies, such as Ion Torrent, also produce high-quality data, though some platforms may have limitations with homopolymer regions [3] [22].

Economic Considerations: Acquisition and Operational Costs

The total cost of ownership (TCO) for an NGS platform extends far beyond the initial purchase price.

- Instrument Acquisition: Benchtop sequencers represent a lower capital investment, with prices ranging from approximately $50,000 to $335,000 for models from Illumina, Ion Torrent, and others [25] [29]. Production-scale systems, in contrast, require a significant capital commitment, often costing between $600,000 and over $1 million [29].

- Operational and Reagent Costs: Recurrent costs for reagents, flow cells, and library preparation kits constitute a major part of the TCO. Benchtop runs can cost a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, making them cost-efficient for smaller projects [25]. Production-scale systems, while having higher per-run reagent costs, achieve a much lower cost-per-gigabase at maximum throughput, providing economies of scale [30] [29].

- Infrastructure and Data Management: Production-scale instruments generate terabytes of data per run, necessitating robust computational infrastructure, high-performance data storage, and sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines [30]. Benchtop systems have more modest data management needs, though proper planning for data analysis and storage is still essential [30].

Table 2: Economic and Operational Considerations

| Factor | Benchtop Sequencers | Production-Scale Sequencers |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Instrument Cost | \$50,000 – \$335,000 [25] [29] | \$600,000 – \$1,000,000+ [29] |

| Typical Cost per Run | Lower (e.g., Mid-output: ~$550 [25]) | Higher, but lower cost/Gb at scale |

| Data Output Management | Moderate IT infrastructure required | Demands robust IT, high-performance computing, and large-scale storage [30] |

| Laboratory Space | Standard lab bench | Dedicated, controlled environment |

| Personnel | Suitable for labs with limited dedicated NGS staff | Often requires specialized technical and bioinformatic support |

Experimental Protocols for Chemogenomics Research

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Compound Profiling via Targeted Gene Expression

Objective: To evaluate the transcriptomic responses of cell lines to a library of small-molecule compounds.

Methodology:

- Cell Treatment & RNA Extraction: Plate cancer cell lines in 96-well format. Treat with compound library for 24 hours. Lyse cells and extract total RNA.

- Library Preparation: Use a stranded mRNA-seq library prep kit. Fragment purified mRNA and synthesize cDNA. Ligate dual-indexed adapters to enable sample multiplexing [27].

- Library QC and Pooling: Quantify libraries using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Quantifluor) [27]. Pool libraries equimolarly.

- Sequencing: Load pooled library onto a mid-throughput benchtop sequencer (e.g., NextSeq 1000) with a 2x150 bp configuration. This is ideal for gene expression quantification.

- Data Analysis: Align reads to the reference transcriptome. Perform differential gene expression analysis to identify compound-specific signatures and pathway enrichment.

Protocol 2: Discovery of Resistance Mechanisms via Whole Genome Sequencing

Objective: To identify novel genetic variants that confer resistance to a lead therapeutic compound.

Methodology:

- Sample Generation: Generate drug-resistant cell lines via long-term exposure to increasing concentrations of the compound. Isolate genomic DNA from resistant and parental control cells.

- Library Preparation for WGS: Shear gDNA to a desired insert size (e.g., 350-600 bp) using a focused-ultrasonication system [27]. Prepare PCR-free libraries if input DNA quality and quantity permit to reduce bias.

- Library QC and Pooling: Employ a "pre-pool QC" strategy: sequence a small fraction of each library on a low-throughput benchtop system (e.g., MiSeq) to check quality and balance pooling ratios before full-depth sequencing [27].

- Deep Sequencing: Perform whole-genome sequencing to a high coverage (e.g., >30x) on a production-scale sequencer (e.g., NovaSeq X). This platform provides the cost-effective, high-throughput capacity needed for multiple resistant models and controls.

- Data Analysis: Perform variant calling (SNPs, indels, structural variants) across the genome. Compare resistant lines to parental controls to pinpoint candidate resistance mutations.

Diagram 1: Generalized chemogenomics sequencing workflow from compound treatment to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for NGS in Chemogenomics

| Item | Function in Workflow | Application Context in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Covaris ME220 | Shears genomic DNA into fragments of a defined size distribution using focused ultrasonication [27]. | Essential for preparing WGS libraries from cell lines or tissues to study drug-induced genomic alterations. |

| KAPA HyperPrep Kit | A library preparation kit for DNA sequencing, incorporating end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation steps [27]. | A versatile kit for constructing sequencing libraries from gDNA for variant discovery. |

| Quantifluor dsDNA System | A fluorescent dye-based assay for accurate quantification of double-stranded DNA concentration [27]. | Critical for normalizing library concentrations before pooling and sequencing to ensure balanced sample representation. |

| Agilent TapeStation | An automated electrophoresis system that assesses the quality, size, and integrity of DNA libraries [27]. | Used for QC of finished libraries to confirm correct size distribution and absence of adapter dimers. |

| Dual Indexed UDIs | Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) are molecular barcodes that allow precise sample multiplexing and demultiplexing while minimizing index hopping [27]. | Enables pooling of dozens of samples from different compound treatments, reducing per-sample sequencing cost. |

| Cloudbreak / AVITI Chemistry | Proprietary sequencing chemistry on the AVITI benchtop system enabling high-quality data and flexible run configurations [27]. | Facilitates both rapid, low-depth QC runs and high-depth production runs on the same platform. |

Decision Framework: Selecting the Right Platform for Your Research Goals

Choosing between a benchtop and production-scale sequencer depends on a careful analysis of your project's specific needs. The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway to guide this critical choice.

Diagram 2: A decision framework for selecting a sequencing platform based on primary research needs.

Key Decision Factors

- Project Scale and Throughput: For projects requiring fewer than 50 whole human genomes per year or focused on targeted/exome sequencing, a mid-throughput benchtop system is often sufficient and more cost-effective. For population-scale studies or projects requiring hundreds of whole genomes, a production-scale system is necessary to achieve the required throughput and economies of scale [23] [26].

- Turnaround Time Requirements: If rapid results are critical for iterative experiments or time-sensitive diagnostics (e.g., in a drug screening cascade), the speed of benchtop systems is a decisive advantage [27] [24].

- Budget and Infrastructure: Consider not only the instrument price but also the total cost of ownership, including reagents, maintenance, and the computational infrastructure for data storage and analysis. Production-scale sequencing demands a significant investment in all these areas [30].

- Operational Flexibility: A benchtop sequencer offers the flexibility to run smaller, more frequent batches, adapting quickly to changing research demands without the need to batch hundreds of samples to justify a run [25].

The dichotomy between benchtop and production-scale sequencers is not a matter of one being superior to the other, but rather a question of strategic fit for the research context. Benchtop sequencers empower individual labs and core facilities with unprecedented speed, flexibility, and control for targeted and medium-throughput studies central to hypothesis-driven chemogenomics. Production-scale sequencers remain indispensable for large-scale discovery efforts, where the ultimate cost-efficiency and massive throughput enable population-level insights and the comprehensive characterization of genomic landscapes.

The most successful chemogenomics research programs will likely leverage both platforms in a complementary manner: using benchtop systems for rapid QC, pilot studies, and focused projects, while partnering with large-scale sequencing centers or investing in production-scale technology for the largest genome discovery initiatives. As NGS technology continues to advance, the performance of benchtop systems will keep rising, further blurring the lines between these categories and making powerful genomic insights increasingly accessible to drug discovery scientists.

Chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, integrating large-scale genomic analysis with functional drug response profiling to elucidate the complex relationships between genetic makeup and drug sensitivity. This whitepaper examines the foundational role of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in advancing chemogenomics research. By enabling comprehensive characterization of genetic variants, transcriptional networks, and epigenetic modifications, NGS technologies provide the critical data infrastructure required for target identification, patient stratification, and biomarker discovery. We present current NGS platforms, detailed methodological frameworks for chemogenomic studies, and essential research tools that collectively empower researchers to decode the functional genomic landscape of drug response and accelerate the development of personalized therapeutic strategies.

Chemogenomics is a systematic approach that investigates the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems through the comprehensive analysis of genomic features and their functional responses to drug perturbations. This field has emerged as a cornerstone of precision medicine, addressing the critical need to understand how genetic variations influence drug efficacy, toxicity, and resistance mechanisms. The advent of Next-Generation Sequencing has fundamentally transformed chemogenomics from a theoretical concept into a practical research discipline by providing the technological capacity to generate multidimensional genomic datasets at unprecedented scale and resolution [31].

The integration of NGS within chemogenomics frameworks enables researchers to move beyond single-gene analysis toward a systems-level understanding of drug action. By simultaneously interrogating thousands of genetic variants across diverse biological contexts, NGS facilitates the discovery of novel drug targets, predictive biomarkers, and resistance mechanisms that would remain undetectable using conventional approaches [32]. This capability is particularly valuable in complex diseases such as cancer, where tumor heterogeneity and dynamic evolution under therapeutic pressure necessitate comprehensive genomic characterization to develop effective treatment strategies [33].

The foundational role of NGS in chemogenomics extends across the entire drug development continuum, from early target discovery to clinical trial optimization and post-market surveillance. By providing a high-resolution view of the genetic determinants of drug response, NGS empowers researchers to build predictive models that inform therapeutic decision-making and guide the development of combination therapies that overcome resistance mechanisms [34]. As NGS technologies continue to evolve in terms of throughput, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness, their integration into chemogenomics research promises to further accelerate the translation of genomic insights into clinically actionable therapeutic strategies.

NGS Technology Landscape for Chemogenomics Research

The selection of an appropriate NGS platform is a critical consideration in designing chemogenomics studies, as each technology offers distinct advantages tailored to specific research applications. Modern NGS platforms can be broadly categorized into short-read and long-read sequencing technologies, each with characteristic profiles for read length, throughput, accuracy, and cost that influence their utility for different aspects of chemogenomics research [3] [16].

Second-Generation Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

Short-read sequencing technologies remain the workhorse for the majority of chemogenomics applications due to their high accuracy and cost-effectiveness for large-scale sequencing projects. These platforms utilize sequencing-by-synthesis approaches to generate billions of short DNA fragments in parallel, providing comprehensive coverage of genomic regions of interest [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Short-Read NGS Platforms for Chemogenomics Applications

| Platform | Technology | Max Read Length | Throughput Range | Key Applications in Chemogenomics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) with reversible dye-terminators | 300-600 bp | 8-16 Tb per run | Whole genome sequencing (WGS), transcriptomics, epigenomics, large-scale variant discovery | Higher initial instrument cost, requires high sample multiplexing for cost efficiency |

| Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 | SBS with reversible dye-terminators | 300-600 bp | 120-600 Gb per run | Targeted gene panels, exome sequencing, RNA-seq for patient stratification | Moderate throughput compared to production-scale systems |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T1+ | DNA nanoball sequencing with combinatorial probe anchor synthesis | Up to 400 bp | 25-1200 Gb per run | Population-scale studies, pharmacogenomic screening | Limited availability in some geographic regions |

| Thermo Fisher Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions | 200-600 bp | 1-80 Gb per run | Targeted sequencing, rapid turnaround for clinical applications | Higher error rates in homopolymer regions |

Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis technology dominates the short-read landscape, with platforms ranging from the benchtop MiSeq i100 Series to the production-scale NovaSeq X [13] [33]. These systems employ fluorescently-labeled reversible terminator nucleotides that are incorporated into growing DNA strands, with imaging-based detection providing highly accurate base calling. The platform's versatility supports diverse chemogenomics applications including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics, epigenomic profiling, and targeted sequencing of pharmacogenetic loci [33].

Alternative short-read technologies include MGI's DNBSEQ platforms, which utilize DNA nanoball technology and combinatorial probe anchor synthesis to generate high-quality sequencing data with reduced reagent costs [13]. Thermo Fisher's Ion Torrent systems employ semiconductor sequencing that detects hydrogen ions released during nucleotide incorporation, offering rapid turnaround times that are advantageous for time-sensitive clinical applications [21] [35].

Third-Generation Long-Read and Emerging Sequencing Technologies

Long-read sequencing platforms address specific challenges in chemogenomics research by enabling the resolution of complex genomic regions that are inaccessible to short-read technologies. These include highly repetitive sequences, structural variants, and complex gene rearrangements that frequently contribute to drug resistance and variable therapeutic responses [3].

Table 2: Long-Read and Emerging Sequencing Platforms for Complex Chemogenomics Applications

| Platform | Technology | Max Read Length | Throughput Range | Key Applications in Chemogenomics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Revio | Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing | 10-25 kb | 360-1200 Gb per run | Full-length transcript sequencing, phased variant detection, structural variant identification in drug targets | Higher per-base cost, requires specialized bioinformatics expertise |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (MinION, PromethION) | Nanopore sequencing measuring electrical current changes | Up to 2 Mb | 10-100 Gb per flow cell | Real-time sequencing for rapid diagnostics, direct RNA sequencing, metagenomic analysis of microbiome-drug interactions | Higher error rate compared to short-read technologies |

| Ultima Genomics UG 100 Solaris | Non-optical sequencing with patterned flow cells | ~300 bp | Up to 10-12 billion reads per wafer | Large-scale population studies, comprehensive pharmacogenomic variant screening | Emerging technology with evolving ecosystem |

Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) employs Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, which immobilizes DNA polymerase within microscopic zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) to observe nucleotide incorporation in real-time [3] [35]. This technology generates long reads that span complex genomic regions, enabling the detection of structural variants and phased haplotypes that are critical for understanding the relationship between genetic variation and drug response.

Oxford Nanopore Technologies utilizes protein nanopores embedded in a polymer membrane to measure changes in electrical current as DNA or RNA molecules pass through the pores [3]. The platform's capacity for ultra-long reads and direct RNA sequencing without reverse transcription provides unique advantages for characterizing fusion transcripts, alternative splicing events, and epigenetic modifications that influence drug sensitivity [13] [35].

Emerging platforms such as Ultima Genomics are driving further reductions in sequencing costs through innovative engineering approaches. The UG 100 Solaris system achieves a price of $80 per genome by utilizing patterned flow cells and non-optical detection methods, potentially enabling unprecedented scale in chemogenomics studies [13].

Methodological Framework for NGS in Chemogenomics

The successful application of NGS in chemogenomics research requires the implementation of robust experimental and computational workflows designed to generate high-quality, reproducible data. This section outlines comprehensive methodologies for integrating NGS with functional drug screening, highlighting best practices and quality control measures essential for generating reliable insights.

Integrated Chemogenomic Profiling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for integrating NGS with drug sensitivity and resistance profiling in a chemogenomics study:

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing for Actionable Mutation Detection

Targeted NGS focuses sequencing capacity on predefined genomic regions with established or potential relevance to drug response, enabling deep coverage of pharmacogenes at reduced cost compared to whole-genome approaches. This method is particularly valuable for clinical translation where turnaround time and cost are critical considerations [32] [34].

Protocol: Hybrid Capture-Based Targeted Sequencing

Library Preparation: Fragment 50-200 ng of genomic DNA via acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation to generate 150-300 bp fragments. Ligate platform-specific adapters containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to enable duplicate removal and error correction.

Target Enrichment: Hybridize sequencing libraries with biotinylated oligonucleotide probes targeting a predefined set of pharmacogenes (e.g., 200-500 genes). Common targets include:

- Drug metabolism enzymes: CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, TPMT, DPYD

- Drug transporters: ABCB1, ABCG2, SLC22A2

- Drug targets: EGFR, BRAF, KIT, FLT3, BCR-ABL

- Cancer predisposition genes: TP53, BRCA1, BRCA2

Post-Capture Amplification: Enrich target-bound fragments via PCR amplification (8-12 cycles) using primers complementary to the adapter sequences.

Sequencing: Pool barcoded libraries and sequence on an appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000) to achieve minimum 500x coverage across >95% of target regions.

Variant Calling and Annotation: Process raw sequencing data through a bioinformatic pipeline including:

- Quality Control: FastQC for read quality assessment

- Alignment: BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 alignment to reference genome

- Variant Calling: GATK HaplotypeCaller or VarScan for SNV/indel detection

- Annotation: ANNOVAR or SnpEff for functional consequence prediction

- Pharmacogenetic Interpretation: PharmGKB and CPIC guidelines for clinical annotation

Ex Vivo Drug Sensitivity and Resistance Profiling (DSRP)

Functional drug screening complements genomic analysis by providing direct empirical evidence of drug response phenotypes. The integration of DSRP with NGS data enables the identification of chemogenomic associations that inform mechanism-based treatment strategies [32].

Protocol: High-Throughput Drug Sensitivity Screening

Sample Preparation: Isolate mononuclear cells from patient specimens (peripheral blood or bone marrow) via density gradient centrifugation. Determine viability and count using trypan blue exclusion. Plate 5,000-20,000 viable cells per well in 384-well format.

Drug Panel Preparation: Prepare a curated library of 50-150 clinically relevant compounds spanning multiple therapeutic classes:

- Targeted therapies: Kinase inhibitors, epigenetic modulators

- Chemotherapeutic agents: Cytarabine, daunorubicin, topoisomerase inhibitors

- Investigational compounds: Clinical-stage candidates with novel mechanisms

Serially dilute compounds in DMSO across 5-8 concentrations (typically 0.1 nM - 10 μM) using automated liquid handling systems.

Drug Exposure and Incubation: Transfer compound dilutions to assay plates containing cells. Include DMSO-only controls for normalization. Inculture plates for 72-96 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Viability Assessment: Quantify cell viability using homogeneous ATP-based assays (CellTiter-Glo). Measure luminescence signal using a plate reader. Alternative endpoints may include apoptosis markers (caspase activation) or cell proliferation dyes.

Dose-Response Modeling: Calculate normalized viability values relative to DMSO controls. Fit dose-response curves using a four-parameter logistic model: [ Viability(D) = E{\text{min}} + \frac{E{\text{max}} - E{\text{min}}}{1 + (\frac{D}{EC{50}})^h} ] where (D) is drug concentration, (EC_{50}) is half-maximal effective concentration, and (h) is Hill slope.

Z-score Calculation: Normalize drug sensitivity across a reference population to identify outlier responses: [ Z = \frac{EC{50{\text{patient}}} - \mu{EC{50{\text{reference}}}}}{\sigma{EC{50{\text{reference}}}}} ] where (\mu) and (\sigma) represent the mean and standard deviation of (EC_{50}) values from a reference cohort [32].

Integrated Chemogenomic Data Analysis

The integration of genomic and functional screening data represents the core analytical challenge in chemogenomics. This process identifies statistically significant associations between molecular features and drug response phenotypes.