Kinetic Profiling in Cytotoxicity Phenotypic Screening: Advancing Predictive Drug Discovery

This article explores the integration of kinetic profiling with phenotypic cytotoxicity screening, a transformative approach for modern drug discovery.

Kinetic Profiling in Cytotoxicity Phenotypic Screening: Advancing Predictive Drug Discovery

Abstract

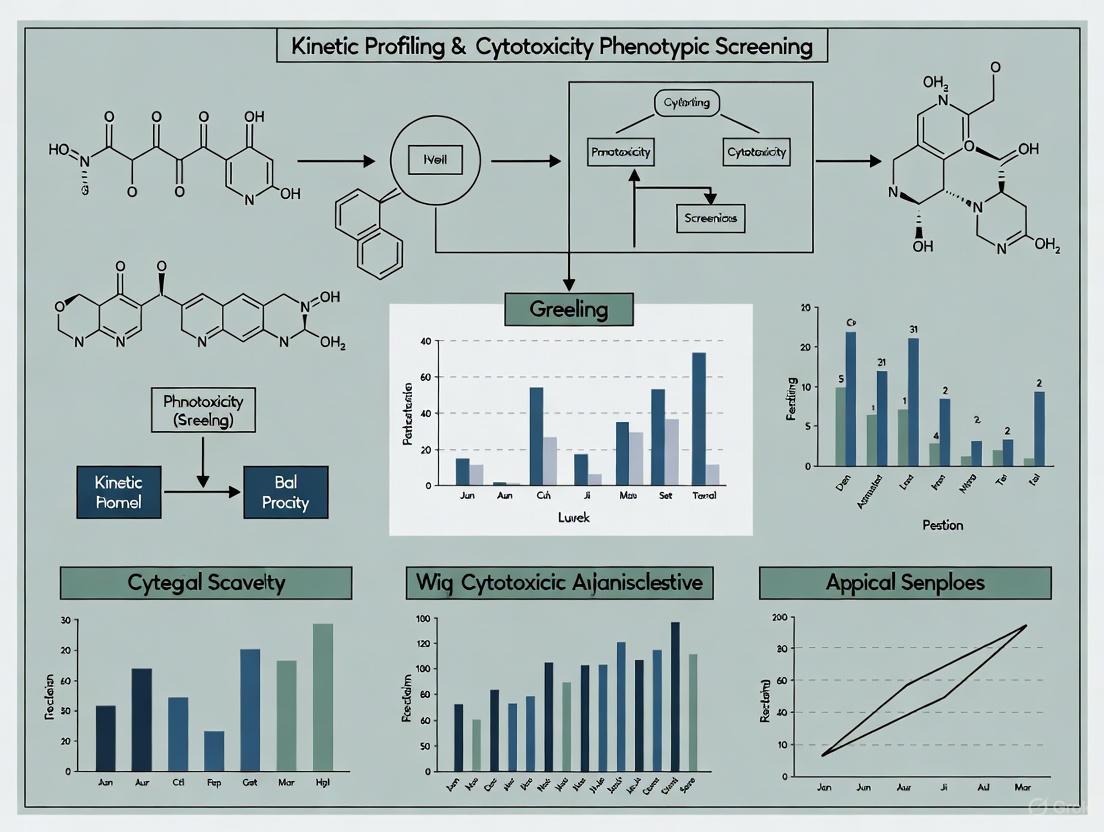

This article explores the integration of kinetic profiling with phenotypic cytotoxicity screening, a transformative approach for modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details how real-time, dynamic assessment of cellular responses moves beyond single-time-point assays to enhance the prediction of compound toxicity and efficacy. The scope covers foundational principles, advanced methodological applications including high-content imaging and live-cell analysis, strategies for troubleshooting and data optimization, and the critical validation of these approaches against traditional methods. By providing a comprehensive framework, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement kinetic strategies, thereby improving the identification of high-quality, safe therapeutic candidates and de-risking the development pipeline.

The Resurgence of Phenotypic Screening and the Case for Kinetic Cytotoxicity Assessment

Phenotypic Screening's Role in Discovering First-in-Class Medicines

Phenotypic screening is a drug discovery approach that identifies bioactive compounds based on their ability to produce a desired observable change in a biological system, without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [1]. Unlike target-based drug discovery, which focuses on modulating predefined proteins, phenotypic screening evaluates how compounds influence complex biological networks as a whole [2] [3].

This method has re-emerged as a powerful strategy following a 2011 review showing that between 2000 and 2008, phenotypic approaches yielded 28 first-in-class small molecule drugs compared to 17 from target-based strategies [3]. Modern phenotypic drug discovery combines this foundational concept with contemporary tools including high-content imaging, CRISPR functional genomics, and artificial intelligence, making it a critical testing ground for technical innovations in the life sciences [2] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Cytotoxic Compound Interference in Assay Readouts

Problem: Active compounds identified in primary screens demonstrate non-specific cytotoxicity rather than targeted modulation of the desired phenotype.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Early Cytotoxicity Counter-Screening: Profile your compound library against "normal" cell lines (e.g., HEK 293, NIH 3T3) in parallel to your disease model. Use a minimum of four normal cell lines to assess pan-activity and selectivity [4].

- Utilize Multiplexed Viability Assays: Incorporate a real-time, kinetic viability endpoint such as ATP-based luminescence (CellTiter-Glo) or caspase activation biosensors (e.g., NucView) to differentiate cytotoxic from cytostatic or phenotype-modifying effects [4] [5].

- Analyze Concentration-Response Relationships: Classify compounds based on full concentration-response curves. Triage compounds that show classic cytotoxic curves (Class -1.1, -1.2) with high efficacy (>80% inhibition) across multiple normal cell lines [4].

Prevention: Pre-screen chemical libraries for cytotoxicity before initiating large-scale phenotypic campaigns. One study profiling >100,000 compounds found a significant portion exhibited cytotoxic effects, which can be flagged and deprioritized upfront [4].

Issue 2: Challenges with Hit Validation and Target Deconvolution

Problem: Confirming that a phenotypic hit is acting "on-target" and identifying its mechanism of action (MoA) is complex and time-consuming.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Employ Kinetic Profiling Early: Use live-cell, impedance-based systems (e.g., xCELLigence) to generate time-dependent cell response profiles (TCRPs). Compounds with similar mechanisms of action often cluster based on similar TCRPs, providing predictive mechanistic information before formal target identification [6].

- Implement Orthogonal Genetic Screens: Combine small-molecule screening with CRISPR/Cas9-based functional genomics. A genome-wide knockout screen (e.g., using a library with >76,000 sgRNAs) can identify genes whose mutation rescues or enhances the compound-induced phenotype, revealing potential targets or pathway members [7].

- Apply Multi-Omics Integration: After hit confirmation, use transcriptomic, proteomic, and phosphoproteomic profiling to build a comprehensive signature of compound activity. Tools like the Connectivity Map can help link this signature to known MoAs [8] [9].

Prevention: Design secondary assays that are mechanistically informative from the start. High-content imaging that captures multiple parameters (e.g., morphology, biomarker localization) provides a rich dataset for MoA hypothesis generation even before target deconvolution begins [5].

Issue 3: Poor Translation from In Vitro Models to Clinical Relevance

Problem: Hits identified in simplified 2D cell models fail to show efficacy in more physiologically relevant systems or in vivo.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Advance Your Disease Model: Transition from 2D monocultures to more complex models such as 3D organoids, patient-derived primary cells, or co-culture systems that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment or tissue architecture [3] [1].

- Incorporate Phenotypic Profiling in Complex Models: Use high-content imaging and analysis pipelines adapted for 3D and co-culture formats. While throughput is lower, the increased physiological relevance helps prioritize compounds with a higher probability of clinical success [5].

- Validate with Kinetic Live-Cell Assays: Kinetic analysis in live cells using reagents like NucView (for apoptosis) allows you to correlate the timing of phenotypic response with the in vivo pharmacokinetic properties of the hit, helping to predict optimal dosing schedules earlier [5].

Prevention: Invest in developing a high-value, disease-relevant biological system for the primary screen. "We really need to make sure that these cell models are of high value... We need to find a way to recreate the disease in a microplate. That way we can expect higher translation to patients," advises Fabien Vincent, Associate Research Fellow at Pfizer [3].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: When should I choose a phenotypic screening approach over a target-based one? A phenotypic approach is particularly advantageous when: 1) no attractive molecular target is known for your disease of interest; 2) the project goal is to obtain a first-in-class drug with a novel mechanism of action; or 3) the disease involves complex, polygenic pathways with potential redundancies and compensatory mechanisms [2] [9] [1]. It is especially well-suited for uncovering unexpected biology and expanding "druggable" target space [2].

Q2: What are the key considerations for setting up a high-throughput phenotypic screen?

- Biological Model: Select the most physiologically relevant model feasible for your throughput (e.g., iPSC-derived cells, 3D cultures) [1].

- Readout: Choose a high-content, information-rich readout (e.g., multiparameter imaging, transcriptomic profiling) that robustly captures the desired phenotype [8] [5].

- Library Design: Consider using annotated libraries (compounds with known MoA) alongside diverse chemical libraries to facilitate early MoA insights [4].

- Counter-Screens: Plan cytotoxicity and assay-interference counter-screens (e.g., luciferase inhibition assay) from the beginning to triage false positives [4].

Q3: How is AI transforming phenotypic screening? AI and machine learning are addressing key bottlenecks. For example, the DrugReflector model uses a closed-loop active reinforcement learning framework trained on transcriptomic signatures to predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes. This approach can improve hit rates by an order of magnitude compared to screening random libraries, enabling smaller, more focused, and more efficient screening campaigns [8] [9].

Q4: Can phenotypic screening be used for discovering combination therapies? Yes, phenotypic screening is a powerful tool for identifying rational drug combinations. Dose-ratio matrix screening in complex biological assays, followed by analysis using methods like the combination index theorem, can systematically identify synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects. This approach is valuable for overcoming redundancy in disease pathways and addressing inherent or acquired resistance [5].

Quantitative Data and Protocols

Cytotoxicity Profiling of Screening Libraries

Large-scale cytotoxicity profiling provides essential reference data for triaging non-selectively cytotoxic compounds. The table below summarizes hit rates from profiling nearly 10,000 annotated and over 100,000 diverse library compounds [4].

Table 1: Cytotoxicity Hit Rates Across Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Type | Cytotoxicity Hit Rate (Annotated Library) | Cytotoxicity Hit Rate (Diversity Library) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293 | Normal (Embryonic Kidney) | Reported in study | ~1% |

| NIH 3T3 | Normal (Fibroblast) | Reported in study | ~1% |

| CRL-7250 | Normal (Fibroblast) | Reported in study | N/A |

| HaCat | Normal (Keratinocyte) | Reported in study | N/A |

| KB 3-1 | Cancer (HeLa subline) | Reported in study | N/A |

Note: The complete quantitative data for the annotated library is available in the source material [4]. The diversity library showed a lower hit rate, but the absolute number of cytotoxic compounds was significant due to the large library size.

Experimental Protocol: Kinetic Cell-Based Morphological Screening

This protocol uses impedance-based readouts to monitor the temporal effects of compounds, providing mechanistic information through kinetic profiling [6].

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the key steps in kinetic phenotypic screening leading to hit clustering and mechanistic prediction.

Key Materials:

- Equipment: Real-time cell analyzer (e.g., xCELLigence RTCA), automated liquid handler, CO2 incubator.

- Reagents: Appropriate cell line, compound library, cell culture medium and supplements.

- Software: Software for analyzing time-course data and performing hierarchical clustering.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in specialized 96- or 384-well E-plates that contain integrated microelectrodes. Allow cells to adhere and establish a stable baseline impedance signal (typically 24 hours).

- Compound Addition: Using an automated liquid handler, add compounds from your library across a range of concentrations (e.g., 3-4 logs). Include controls (DMSO vehicle and reference compounds with known mechanisms).

- Kinetic Data Acquisition: Place the E-plate in the analyzer inside the incubator. Monitor and record the impedance value (reported as Cell Index) continuously for 48-72 hours. The instrument typically takes readings every 15-30 minutes.

- Profile Generation: For each compound, normalize the Cell Index data over time to the point of compound addition to generate its unique TCRP.

- Data Analysis and Clustering: Use hierarchical clustering algorithms to group compounds with highly similar TCRPs. Co-clustering of a hit with compounds of known MoA provides a strong, predictive hypothesis for its own mechanism of action [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Wide Library (e.g., >76,000 sgRNAs) | Enables genome-wide knockout screens to identify genes essential for a phenotype, aiding in target identification and validation [7]. |

| CellTiter-Glo or Other Viability Assay Reagents | Provides a luminescent or fluorescent endpoint for quantifying ATP levels, a marker of cell viability, essential for cytotoxicity counter-screening [4]. |

| High-Content Imaging-Compatible Dyes (e.g., for nuclei, cytoskeleton, organelles) | Allow for multiplexed, multiparameter analysis of cell morphology and phenotype in fixed or live cells [5] [1]. |

| Real-Time Caspase Biosensors (e.g., NucView) | Enable kinetic profiling of apoptosis induction in live cells, helping to differentiate specific MoAs from general cytotoxicity [5]. |

| Impedance-Based Monitoring Systems (e.g., xCELLigence) | Facilitate label-free, kinetic monitoring of cell responses (proliferation, death, morphology) for mechanistic clustering of hits [6]. |

| Annotated Compound Libraries (e.g., FDA-approved drugs, known bioactives) | Serve as reference sets for MoA prediction via profiling and are valuable tools for drug repurposing efforts [4]. |

Kinetic profiling represents a transformative approach in cytotoxicity phenotypic screening, moving beyond traditional single time-point analyses to capture the dynamic response of cells to compound exposure over time. In modern drug discovery, cytotoxicity profiling of chemical libraries at an early stage is essential for increasing the likelihood of candidate success, helping researchers prioritize molecules with little or no cytotoxicity for downstream evaluation [4]. Unlike endpoint measurements that provide a static snapshot, kinetic profiling enables researchers to quantify the temporal progression of cell death, viability, and metabolic changes, offering richer data for distinguishing between specific pharmacological effects and general cytotoxic responses. This approach is particularly valuable in phenotypic screening, where understanding the dynamics of cellular response can provide critical insights into mechanism of action and improve the prediction of in vivo outcomes [2] [10].

Core Principles of Kinetic Profiling

Temporal Resolution and Dynamic Monitoring

Kinetic profiling requires continuous or frequent-interval monitoring of cellular parameters throughout the exposure period. This principle emphasizes that the timing and rate of cytotoxic response can be as informative as the final outcome. For example, different mechanisms of cell death (apoptosis, necrosis, pyroptosis) often exhibit distinct kinetic signatures that can be discriminated through proper temporal monitoring.

Multiparametric Assessment

True kinetic profiling integrates multiple complementary readouts to capture different aspects of cellular health and function. These typically include:

- Metabolic activity (e.g., ATP levels via CellTiter-Glo)

- Membrane integrity

- Morphological changes

- Specific pathway activation markers

Contextual Relevance

The kinetic parameters derived must be interpreted within the specific biological context of the assay system, including cell type, culture conditions, and compound exposure protocols. Research demonstrates that spatial organization significantly impacts cell signaling, requiring quantitative models that appreciate the importance of spatial organization in cellular membranes [11].

Quantitative Parameter Extraction

Kinetic profiling emphasizes derivation of quantitative parameters that describe the dynamics of cellular response, such as:

- EC50 values over time

- Maximum response rates (Vmax)

- Lag times before response initiation

- Area Under the Curve (AUC) for response trajectories

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Kinetic Profiling in Cytotoxicity Screening

| Reagent/Assay | Function in Kinetic Profiling | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay | Quantifies ATP levels as a marker of metabolically active cells | Used in high-throughput cytotoxicity profiling of compound libraries [4] |

| Pro-chromogenic substrates (e.g., indole-3-carboxaldehydes) | Enzyme activity detection through colorimetric change | Enables rapid, convenient screening adaptable for large sample numbers [12] |

| Firefly luciferase reporter systems | Monitoring specific pathway activities | Requires counter-screening for luciferase inhibitors to avoid artifacts [4] |

| Multiplexed assay components | Simultaneous measurement of multiple cell health parameters | Allows correlated kinetic analysis of different death pathways |

| Automated live-cell imaging dyes | Temporal tracking of morphological changes | Enables high-content kinetic profiling without fixed timepoints |

Kinetic Profiling Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for implementing kinetic profiling in cytotoxicity screening:

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

High-Throughput Kinetic Cytotoxicity Profiling

Protocol for 1536-well Plate Cytotoxicity Screening [4]

Cell Seeding: Seed HEK 293, NIH 3T3, CRL-7250, HaCat, or KB 3-1 cells into white 1536-well plates using a Multidrop Combi peristaltic dispenser at densities of 250-500 cells/well in 5 μL of medium, depending on cell line.

Compound Transfer: Use a pintool (Kalypsys) to transfer 23 nL of compound solution to the 1536-well assay plates.

Kinetic Incubation: Incubate plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ and 85% humidity for the duration of the kinetic monitoring period (typically 48 hours).

Multi-timepoint Assessment: At designated timepoints (e.g., 6, 12, 24, 48 hours), dispense 2.5 μL of CellTiter-Glo reagent into each well using a dispenser with solenoid valves.

Signal Detection: Allow plates to equilibrate at room temperature for 10 minutes before imaging ATP-coupled luminescence using a ViewLux microplate imager.

Data Processing: Normalize raw plate reads for each titration point relative to positive control (9.2 μM Bortezomib, -100% activity) and DMSO-only wells (basal, 0% activity).

Parameter Estimation from Time-Course Data

Incremental Iterative Parameter Estimation Method [13]

Data Preprocessing: Perform data smoothing to reduce noise effects and obtain reliable slope estimates from time-course metabolite concentration data.

Two-Phase Estimation:

- Phase 1 (Slope Error Minimization): Estimate subset parameters associated with measured metabolites using minimization of slope errors, avoiding computationally expensive ODE integration.

- Phase 2 (Concentration Error Minimization): Solve the ODE model one equation at a time and obtain remaining model parameters by minimizing concentration errors.

Iterative Refinement: Iterate between the two estimation phases until parameter estimates converge (difference between iterations less than chosen convergence factor).

Global Optimization: Use scatter search global optimization (SSm) methods to solve optimization problems in both phases, as this approach has proven effective for multi-minima problems common in kinetic parameter estimation.

Kinetic Parameter Determination Methods

Table 2: Methods for Determining Kinetic Parameters from Experimental Data

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Method | Fits integrated rate equation to concentration-time data | Straightforward implementation; visual validation through linear plots | Requires assumption of reaction order; limited to simpler mechanisms [14] |

| Differential Method | Directly uses reaction rate equation with measured rate data | No need to assume specific integrated form; applicable to complex mechanisms | Amplifies noise through differentiation; requires high-quality data [14] |

| Incremental Iterative Estimation | Combines decoupling and ODE decomposition in iterative phases | Handles missing metabolite data; computationally efficient; avoids ODE stiffness issues [13] | Requires multiple iterations; complex implementation |

| Bayesian Computational Modeling | Uses probabilistic inference from target gene measurements | Quantitative measurement of functional pathway activity; handles biological variability [15] | Requires calibration samples with known pathway activity |

Signaling Pathways in Cytotoxicity Responses

The cellular response to cytotoxic compounds involves multiple interconnected signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates key pathways relevant to cytotoxicity screening:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Experimental Design and Optimization

Q1: How many timepoints are sufficient for reliable kinetic profiling in cytotoxicity screening?

For most cytotoxicity applications, a minimum of 5-8 timepoints across the exposure period is recommended. Critical early timepoints (2-8 hours) help capture rapid responses, while later timepoints (24-72 hours) assess longer-term effects. The optimal spacing depends on the specific cell type and mechanism being studied—proliferating cells may require more frequent early sampling to capture division-dependent effects.

Q2: What cell density should be used for kinetic cytotoxicity assays?

Cell density significantly impacts kinetic readouts and should be optimized for each cell line. As referenced in established protocols, densities typically range from 250-500 cells/well in 1536-well format [4]. Lower densities may enhance sensitivity to cytostatic effects, while higher densities can provide more robust signals for shorter-term kinetic profiling.

Technical Troubleshooting

Q3: How can we distinguish specific cytotoxic compounds from general nuisance compounds in kinetic profiling?

Kinetic profiling provides several discrimination strategies:

- Response Timing: Specific inhibitors typically show mechanistically consistent kinetic signatures, while nuisance compounds (e.g., firefly luciferase inhibitors) may show anomalous time-response relationships [4].

- Multi-parameter Correlation: Genuine cytotoxicity typically shows concordance across multiple measured parameters (metabolic activity, membrane integrity, morphology) with consistent kinetics.

- Pathway Analysis: Computational analysis of pathway activity can distinguish specific mechanisms from general toxicity [15].

Q4: Our kinetic data shows high variability between replicates. What are potential causes and solutions?

Common causes and solutions include:

- Cell Passage Effects: Use consistent passage number ranges and avoid extremes

- Edge Effects: Use proper plate sealing and consider specialized microplates to minimize evaporation

- Instrument Timing: Standardize time between reagent addition and reading across plates

- Data Normalization: Implement robust normalization protocols using reference controls

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Q5: What are the best practices for parameter estimation from noisy time-course data?

The incremental iterative parameter estimation method has proven effective for handling noisy biological data [13]. This approach:

- Combines slope error minimization with concentration error minimization in alternating phases

- Handles situations with missing metabolite measurements

- Uses global optimization strategies to avoid local minima

- Incorporates data smoothing while avoiding overfitting through careful validation

Q6: How can we quantitatively measure pathway activity relevant to cytotoxicity responses?

Bayesian computational models can infer pathway activity from mRNA levels of transcription factor target genes [15]. This approach:

- Uses calibrated computational network models to infer transcription factor activity

- Transforms probability scores into quantitative pathway activity scores (log2odds)

- Enables quantitative comparison of pathway activity across different samples and conditions

- Has been validated for multiple pathways including NF-κB, TGFβ, and others relevant to cytotoxicity

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Kinetic profiling in cytotoxicity screening continues to evolve with technological advancements. Modern phenotypic drug discovery combines therapeutic effects in realistic disease models with modern tools and strategies [2]. Recent innovations include:

- High-Content Kinetic Imaging: Combining temporal resolution with spatial information at single-cell resolution

- Pathway-Specific Reporter Systems: Engineered systems that provide direct readouts of specific pathway activities in living cells

- Microphysiological Systems: Advanced culture models that provide more physiologically relevant kinetic responses

- Machine Learning Approaches: Pattern recognition algorithms that identify subtle kinetic signatures predictive of specific mechanisms

These advanced approaches enable researchers to move beyond simple viability assessments to understand the dynamic cellular response to chemical exposure, ultimately improving the prediction of compound behavior in more complex biological systems.

Why Cytotoxicity Profiling is a Critical Pillar in Hit Triage and Validation

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary role of cytotoxicity profiling in hit triage? Cytotoxicity profiling acts as a critical early filter in hit triage. It identifies compounds that are generally toxic to cells, helping researchers separate compounds with a desired therapeutic effect (on-target) from those that simply kill cells (off-target). This prevents the advancement of promiscuously toxic compounds that are likely to fail in later development stages [16].

A cytotoxicity assay indicates my hit compound is toxic. Does this mean it's a failed drug candidate? Not necessarily. A positive result in a cytotoxicity test indicates the compound has cytotoxic potential, but it is not a definitive indicator of clinical failure. The result must be evaluated within a comprehensive risk assessment. This includes the intended clinical use (e.g., an anticancer drug is expected to be cytotoxic), the therapeutic window, data from other biocompatibility endpoints, and a thorough toxicological risk assessment based on chemical characterization [17] [18].

Why might my hit compound show cytotoxicity in the assay but not in follow-up studies? Cytotoxicity assays are highly sensitive by design and can generate "false positives" for several reasons:

- Assay Interference: The compound may interfere with the assay readout, for example, by being intrinsically fluorescent, absorbing light at the detection wavelength, or directly reacting with the assay reagents [19] [20].

- Physical Effects: Insoluble particles or the physical presence of a material in direct contact with cells can cause reactivity that is not relevant to the in vivo situation [18].

- Chemical Contamination: The sample may be contaminated with endotoxins or solvents from the manufacturing process, which can cause a cytotoxic response [20].

Which cytotoxicity assay is most suitable for hit triage in phenotypic screening? No single assay is universally perfect. The choice depends on your needs. For a high-throughput primary screen, metabolic assays like MTT or resazurin (alamarBlue) are common. For a more detailed mechanism, combining an assay like LDH release (membrane integrity) with a metabolic assay can provide a multiparametric view of cell health. The key is to understand each assay's limitations and use a combination of methods for validation [21] [19].

How do I validate a cytotoxic hit for an anti-cancer application? For a candidate intended to be cytotoxic, such as in oncology, validation involves confirming the activity is specific and not due to general toxicity. This includes:

- Dose-Response: Establishing a concentration-response curve (e.g., IC₅₀).

- Selectivity Profiling: Testing against non-cancerous cell lines to determine a selectivity index.

- Counter-Screens: Ruling out common false-positive mechanisms like chemical aggregation, redox cycling, or interference with assay signals [16] [10].

- Mechanistic Studies: Using high-content imaging or flow cytometry to confirm the mode of cell death (e.g., apoptosis, necrosis) [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background or Inconsistent Results in Cytotoxicity Assays

Problem: Assay results show high variability, high background signal, or inconsistent data between replicates, making it difficult to reliably identify true hits.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Interference | Test compounds may be intrinsically colored, fluorescent, or redox-active, interfering with colorimetric or fluorometric readouts. | Perform an interference check: Include control wells with the compound but no cells to measure background signal. Use an orthogonal assay with a different readout (e.g., switch from MTT to a LDH or ATP assay) to confirm results [19]. |

| Nanoparticle or Insoluble Material | Particles can adsorb assay dyes, scatter light, or settle on cells, causing physical stress and false positives. | Characterize the formulation: Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) to check for agglomeration. Centrifuge extracts to remove particulates before adding to cells. Consider using direct contact assays with caution [20] [18]. |

| Cell Seeding Density | Inconsistent cell numbers per well lead to variable metabolic activity and signal. | Optimize and standardize: Verify signal linearity with cell density. Use a standardized cell counting method and seeding protocol for every experiment [19]. |

| Contamination | Endotoxin or microbial contamination in samples or reagents can trigger a cytotoxic immune response in certain cell types. | Use sterilized, depyrogenated materials: Test samples for endotoxin. Use proper aseptic technique [20]. |

Issue 2: Different Cytotoxicity Assays Yield Conflicting Results for the Same Hit

Problem: A compound is identified as cytotoxic in one assay but shows low toxicity in another, creating uncertainty about its true profile.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Different Biological Endpoints | Assays measure different aspects of cell health (e.g., MTT measures metabolic activity, LDH measures membrane integrity). A compound may inhibit metabolism without immediately lysing cells. | Adopt a multiparametric approach: Use at least two assays measuring different endpoints (e.g., metabolic activity + membrane integrity). This provides a more comprehensive view of cytotoxic mechanisms [19]. |

| Assay Kinetics and Timing | The timing of cytotoxic events may not align with the assay readout. For example, membrane rupture may occur after metabolic shutdown. | Perform kinetic profiling: Take readings at multiple time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours) to capture the evolution of the toxic effect, which is a core principle of kinetic profiling in phenotypic screening [17] [19]. |

| Mechanism of Action | The compound may have a sub-lethal or cytostatic effect that is detected by more sensitive assays (e.g., high-content imaging) but not by basic viability assays. | Use high-content or mechanistic assays: Implement assays that can detect apoptosis (e.g., caspase activation), changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, or cell cycle arrest to understand the subtle effects [19] [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cytotoxicity Assays

The following protocols are adapted from standard guidelines (ISO 10993-5) and recent research for use in hit triage [21] [18].

MTT Assay for Metabolic Activity

Principle: Viable cells reduce yellow MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to purple formazan crystals. The amount of formazan dissolved and measured is proportional to the number of viable cells [21] [19].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed L-929 mouse fibroblast cells or another relevant cell line in a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 10³ to 1 × 10⁴ cells/well in complete medium. Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24 hours to form a near-confluent monolayer.

- Sample Preparation (Extraction): Prepare extracts of your test compounds or materials. For solids, use the elution method: incubate the sample in cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM with serum) at 37°C for 24-72 hours with agitation. The addition of serum (5-10%) is critical for extracting both polar and non-polar constituents [17] [18].

- Application of Extract: Remove the growth medium from the cells and replace it with the compound extracts or control media (negative control: fresh medium; positive control: medium with 1-2% Triton X-100). Incubate for 24-48 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- MTT Incubation: After treatment, add MTT reagent (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL final concentration) to each well and incubate for 2-4 hours at 37°C.

- Solubilization: Carefully remove the MTT-containing medium. Add a solubilization solution (e.g., isopropanol or DMSO) to dissolve the formed formazan crystals.

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each well at a wavelength of 570 nm, with a reference wavelength of 630-650 nm to correct for background.

- Data Analysis: Calculate cell viability as a percentage relative to the negative control group.

Cell Viability (%) = (Mean Absorbance of Test Group / Mean Absorbance of Negative Control) × 100

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Assay

Principle: LDH is a stable cytosolic enzyme released upon cell membrane damage. The released LDH in the culture supernatant is measured with a coupled enzymatic reaction that converts a tetrazolium salt into a red formazan product [19].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Treatment: Seed and treat cells in a 96-well plate as described in the MTT protocol. Include a "background control" (culture medium only), "low control" (untreated cells), and "high control" (cells treated with lysis buffer to release total LDH).

- Sample Collection: After the treatment period, centrifuge the plate at 250 × g for 10 minutes to pellet cells and debris.

- Reaction Setup: Transfer a portion of the supernatant from each well to a new clear 96-well plate.

- LDH Reaction: Add the LDH assay reaction mixture according to the manufacturer's instructions. This typically contains NAD⁺, lactate, iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT), and diaphorase.

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate the plate for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light. Measure the absorbance at 490-500 nm.

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the background control absorbance from all other values.

- Calculate cytotoxicity using the formula:

Cytotoxicity (%) = [(Test Sample - Low Control) / (High Control - Low Control)] × 100

Assay Comparison and Reagent Toolkit

Cytotoxicity Assay Comparison

| Assay | Measured Endpoint | Advantages | Limitations | HTS Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTT | Metabolic activity (mitochondrial dehydrogenase) | Inexpensive, well-established, widely accepted [21] | End product is insoluble, requires solubilization step; subject to chemical interference [19] | Moderate |

| LDH Release | Membrane integrity | Easy to perform, measures a direct marker of cell death [19] | Can be affected by serum in media; measures only late-stage necrosis [19] | High |

| ATP Assay (Luminometric) | Cellular ATP levels (cell viability) | Highly sensitive, broad dynamic range, low background [21] [19] | Requires a luminometer; more expensive than colorimetric assays | High |

| Neutral Red Uptake (NRU) | Lysosomal function & cell viability | More sensitive to some toxicants than MTT; viable cells incorporate the dye [19] | pH-sensitive; longer incubation time required | Moderate |

| Resazurin Reduction (AlamarBlue) | Overall metabolic capacity | Non-toxic, allows for continuous monitoring of the same culture over time [19] | Signal can saturate quickly with high cell numbers | High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Cytotoxicity Profiling |

|---|---|

| L-929 Mouse Fibroblast Cells | A standard cell line recommended by ISO 10993-5 for biocompatibility testing of medical devices and materials [21] [18]. |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | The standard culture medium for maintaining cells. Serum is crucial for extracting non-polar compounds from test materials during sample preparation [21] [18]. |

| MTT Reagent | A tetrazolium salt used to assess cell metabolic activity via mitochondrial dehydrogenases [21] [19]. |

| Triton X-100 | A detergent used as a positive control to induce 100% cell death (cytotoxicity) [19]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A common solvent for dissolving water-insoluble compounds and for solubilizing formazan crystals in the MTT assay [21]. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

Hit Triage Workflow Integrating Cytotoxicity Profiling

The following diagram illustrates a strategic workflow for integrating kinetic cytotoxicity profiling into the hit triage and validation process.

Cytotoxicity Data Interpretation and Risk Assessment

This diagram outlines the logical decision process for evaluating a cytotoxic hit based on its therapeutic context and comprehensive dataset.

Linking Dynamic Cellular Responses to Complex Disease Biology

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of kinetic profiling over endpoint cytotoxicity assays? Kinetic profiling provides continuous temporal data on cellular responses, revealing compound mechanism of action through time-dependent response patterns that single timepoint assays miss. This allows researchers to distinguish between different mechanisms of cell death, identify off-target effects, and determine optimal treatment durations for maximal efficacy [6] [5].

Q2: Why should cytotoxicity profiling be performed early in screening campaigns? Cytotoxicity profiling at an early stage helps triage compounds with promiscuous cell-killing activity that could lead to misleading results in phenotypic screens. In large-scale screening, approximately 1-5% of compounds may demonstrate cytotoxic effects, influencing future project directions and increasing the likelihood of candidate success [4].

Q3: How can researchers distinguish selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells versus general toxicity? This requires parallel profiling against both cancer and "normal" cell lines. Selective compounds show activity primarily in cancer cells, while pan-cytotoxic compounds affect all cell types. Using at least four normal cell lines (e.g., HEK 293, NIH 3T3, CRL-7250, HaCat) and one cancer cell line (e.g., KB 3-1) provides robust selectivity assessment [4].

Q4: What are common artifacts in cytotoxicity assays and how can they be addressed? Common artifacts include firefly luciferase inhibition (∼5% of compounds), air bubbles causing well-to-well variability, improper cell density, and cytotoxic effects of the detection dyes themselves. These can be mitigated through counter-screening assays, careful pipetting techniques, optimization of cell density, and validation of dye compatibility with specific cell types [4] [22] [23].

Q5: How can kinetic profiling guide combination therapy development? Kinetic profiling reveals optimal dosing schedules and sequences for drug combinations by showing when synergistic activity occurs temporally. This helps align in vitro findings with in vivo pharmacokinetic properties, ensuring co-exposure of drugs at target tissues during synergistic time windows [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

High Variability in Cytotoxicity Measurements

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High well-to-well variability | Air bubbles in wellsUneven cell seedingEdge effects in plates | Break bubbles with syringe needle [22]Optimize cell suspension mixingUse edge well controls |

| Low signal intensity | Insufficient cell densityIncorrect assay incubation timeImproper reagent storage | Determine optimal cell count empirically [22]Validate assay kinetics for specific cell typeFreshly prepare reagents |

| Inconsistent concentration-response | Compound solubility issuesPlate reader calibration driftCell passage number too high | Include solubility controls [4]Regular instrument maintenanceUse low-passage cells |

Optimization of Kinetic Profiling Assays

| Challenge | Optimization Strategy | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Determining optimal sampling frequency | Balance temporal resolution with phototoxicity | Test different intervals (15min-2hr) with control compounds [6] |

| Maintaining cell health during live-cell imaging | Optimize CO₂, temperature controlUse minimal light exposure | Compare endpoint viability with static controls [5] |

| Multiplexing kinetic cytotoxicity with other parameters | Spectral separation of probesStaggered addition protocols | Verify no interference between detection channels [23] |

Interpretation of Complex Kinetic Profiles

| Profile Pattern | Potential Interpretation | Follow-up Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid cytotoxicity followed by recovery | Transient membrane disruptionAdaptive stress response | Measure membrane repair mechanismsAssess oxidative stress markers [24] |

| Delayed cytotoxicity | Indirect mechanismCell cycle-dependent effects | Cell cycle synchronizationGene expression profiling |

| Cell line-specific temporal patterns | Tissue-selective toxicityMetabolic activation required | Metabolic profilingMechanistic studies in sensitive lines |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Kinetic Cytotoxicity Profiling Using Impedance-Based Monitoring

Principle: Continuous monitoring of cell viability through electrical impedance measurements reflecting cell adhesion, proliferation, and death [6].

Materials:

- Real-time cell analyzer (e.g., xCELLigence, Incucyte)

- Appropriate cell culture plates with integrated electrodes

- Test compounds and controls

- Cell culture media and supplements

Procedure:

- Prepare cell suspension at optimized density (determined empirically)

- Seed cells into specialized plates and pre-incubate for 24h to establish monolayer

- Establish baseline impedance reading (2-4 hours pre-treatment)

- Add test compounds using precision liquid handler

- Monitor impedance continuously (every 15 minutes) for 48-72 hours

- Normalize data to baseline and plot time-dependent cell response profiles (TCRPs)

- Cluster compounds based on TCRP similarity for mechanism prediction

Data Analysis:

- Calculate normalized cell index values

- Generate TCRPs for each compound

- Perform hierarchical clustering of TCRPs

- Compare profiles to reference compounds with known mechanisms

Protocol 2: High-Content Kinetic Cytotoxicity with Multiplexed Readouts

Principle: Simultaneous monitoring of multiple cell death parameters over time using fluorescent probes and automated microscopy [23] [5].

Materials:

- High-content imaging system with environmental control

- 96-well or 384-well imaging plates

- DNA binding dyes (SYTOX Green, propidium iodide)

- Apoptosis biosensors (NucView caspase substrates)

- Mitochondrial membrane potential dyes (TMRE, JC-1)

Procedure:

- Seed cells at optimized density and incubate 24h

- Add multiplexed dye cocktail 1h before compound treatment

- Treat with test compounds using concentration-response format

- Acquire images every 2-4 hours at 20x magnification

- Include vehicle and positive controls (e.g., staurosporine) on each plate

- Maintain environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂) throughout experiment

Image Analysis Pipeline:

- Segment nuclei and cytoplasm

- Quantify dye intensity per cell

- Measure morphological parameters (cell area, nuclear condensation)

- Track individual cells over time when possible

- Calculate percentage of dead cells for each timepoint

| Cell Line | Type | Annotated Library (∼10,000 cpds) | Diversity Library (∼100,000 cpds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293 | Normal | 3.2% | 1.8% |

| NIH 3T3 | Normal | 2.8% | 2.1% |

| CRL-7250 | Normal | 2.9% | N/D |

| HaCat | Normal | 3.5% | N/D |

| KB 3-1 | Cancer | 5.1% | 3.2% |

| Dye | Excitation/Emission (nm) | Permeability | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide | 535/617 | Dead cells only | Inexpensive, well-established | High background with RNA |

| SYTOX Green | 504/523 | Dead cells only | >500x fluorescence enhancement | Potential cytotoxicity with extended exposure |

| TO-PRO-3 | 642/661 | Dead cells only | Good for multiplexing with GFP | Requires far-red capable imager |

| Hoechst 33342 | 350/461 | All cells at high concentrations | Can distinguish cell cycle | Permeable to live cells at working concentrations |

Signaling Pathways in Cellular Stress Responses

Mitochondrial Stress Response Pathway

Kinetic Profiling Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Kinetic Cytotoxicity Profiling

| Category | Specific Reagents/Solutions | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | HEK 293, NIH 3T3, CRL-7250, HaCat, KB 3-1 [4] | Normal vs. cancer cell cytotoxicity assessment | Use low passage numbers, regular authentication |

| Viability Detection | CellTiter-Glo ATP assay [4] | Quantification of metabolically active cells | Lyse cells before reading for maximum signal |

| Membrane Integrity | SYTOX Green, Propidium iodide [23] | Selective dead cell staining | Validate dye concentration for each cell type |

| Apoptosis Sensors | NucView caspase substrates [5] | Real-time apoptosis monitoring | Compatible with live cell imaging |

| Metabolic Probes | TMRE, JC-1 dyes [24] | Mitochondrial membrane potential | Calibrate for each cell type |

| Compound Libraries | Annotated libraries (∼10,000 compounds) [4] | Mechanism-based profiling | Include known cytotoxic agents as controls |

Instrumentation and Software Solutions

| Platform Type | Example Systems | Primary Application | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impedance-Based | xCELLigence systems [6] | Real-time cell monitoring | Time-dependent cell response profiles |

| High-Content Imagers | ImageXpress, Incucyte [5] | Multiplexed kinetic imaging | Quantitative morphology and fluorescence |

| Plate Readers | ViewLux [4] | Endpoint cytotoxicity | Luminescence, fluorescence intensity |

| Analysis Software | TIBCO Spotfire, Genedata Screener [4] [5] | Profile clustering and synergy analysis | Heatmaps, combination indices |

Implementing Kinetic Cytotoxicity Assays: From Technologies to Workflow Integration

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the key advantages of using real-time impedance biosensors over endpoint assays in cytotoxicity screening?

Real-time impedance biosensors, such as those used in Electrical Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS), provide a label-free, continuous monitoring capability of cell physiology. Unlike endpoint assays, they allow researchers to track dynamic changes in cell status, including cell adherence, spreading, motility, and growth, which are sensitive indicators of cellular physiopathology and response to external stimuli [25]. This enables the capture of time-course dynamical data rather than just one-shot information, offering deeper insights into the kinetic profile of cytotoxic effects [25].

Q2: Our high-content imaging shows high background staining, compromising our data. What are the common causes and solutions?

High background staining, which results in a poor signal-to-noise ratio, can arise from several sources [26]:

- Cause: Endogenous enzymes (like peroxidases or phosphatases) in the tissue sample are reacting with the detection substrate.

- Solution: Quench endogenous peroxidases with 3% H₂O₂ in methanol or use a commercial peroxidase suppressor. Inhibit endogenous phosphatases with levamisole [26].

- Cause: Endogenous biotin or lectins in the sample.

- Solution: Use an avidin/biotin blocking solution. If using an avidin-biotin complex, consider using streptavidin or NeutrAvidin instead of avidin, as they are not glycosylated and won't bind to lectins [26].

- Cause: Nonspecific binding of the primary or secondary antibody.

- Solution: Optimize antibody concentrations. For the secondary antibody, increase the concentration of normal serum from the source species (up to 10%) in the blocking buffer. For the primary antibody, reduce its final concentration or add NaCl (0.15 M to 0.6 M) to the antibody diluent to reduce ionic interactions [26].

Q3: Why is careful parameter selection critical in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for biosensing?

The accuracy and reliability of impedance-based biosensors can be highly dependent on the electrochemical parameters chosen for data analysis. Relying solely on a single parameter like charge transfer resistance (Rct) may ignore other valuable data. Research shows that:

- The signal gain and relative standard deviation (RSD) are dependent on the potential applied during measurement.

- Parameters such as real impedance at specific frequencies can offer a 2.7-fold higher signal gain with negligible RSD compared to conventional Rct analysis.

- Reasonable signals at frequencies above 100 Hz tend to be less dispersive.

- Increasing the concentration of the redox probe can also help reduce the relative standard deviation [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Cell-Based Biosensor Performance

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Target Staining (Imaging) | Primary antibody degradation or denaturation [26]. | Test antibody potency on a positive control; ensure proper storage pH (7.0-8.2) and avoid freeze/thaw cycles by aliquoting [26]. |

| High Background Staining (Imaging) | Nonspecific antibody binding; endogenous enzymes [26]. | Block with higher serum concentrations (up to 10%); quench endogenous enzymes; optimize antibody dilution [26]. |

| High Signal Variability (Impedance) | Inconsistent cell seeding; electrode passivation; suboptimal EIS parameters [25] [27]. | Standardize cell culture protocols; use fresh electrode surfaces; test multiple frequencies/concentrations to identify least dispersive parameters [27]. |

| Low Sensitivity / Dynamic Range | Limited cellular reactivity to the analyte; impractical biosensor regeneration [25]. | Utilize engineered cell reporters and synthetic gene circuits to enhance cellular reactivity to target analytes [25]. |

| Matrix Interference | Nonspecific binding from complex samples (e.g., serum) [28]. | Use blocking agents, antifouling coatings, or pre-filtration of samples [28]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Cytotoxicity Assay Results

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Distinction Between Cytostatic & Cytotoxic Effects | End-point assay masking kinetic differences [25]. | Employ label-free, real-time biosensors (e.g., impedance, SPR) to dynamically monitor changes in cell adhesion and morphology [25]. |

| High False Positives in Phenotypic Screens | Undetected general cytotoxicity from screening compounds [4]. | Profile screening libraries for cytotoxicity early on; use orthogonal assays to confirm on-target activity and triage promiscuous cytotoxic compounds [4]. |

| Inconsistent Results in Metabolic Profiling | Use of in vitro enzyme parameters that do not reflect in vivo conditions [29]. | Utilize data-driven estimations of in vivo kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat) which are more stable and improve model predictions [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Real-Time Impedance-Based Cytotoxicity and Kinetic Profiling

This protocol outlines the use of electrical impedance to monitor cell physiology and detect cytotoxic effects kinetically, based on established biosensing platforms [25] [30].

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Cell Lines: Adherent cell lines relevant to your research (e.g., HEK 293, NIH 3T3 for "normal" cells; HeLa sublines for cancer) [4].

- Instrumentation: Impedance analyzer or LCR meter, cell culture module with integrated microelectrode arrays [25] [30].

- Consumables: Multi-well plates with embedded gold film electrodes [25].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed adherent cells onto the electrode-coated surface of the biosensor at a defined density (e.g., 250-500 cells/well in a 1536-well format) to form a monolayer [4] [30].

- Equilibration & Baseline Recording: Allow cells to adhere and spread for several hours (or overnight) in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂). Record the baseline impedance signal across a frequency range (e.g., 1 kHz to 300 kHz) for a stable period [25] [30].

- Compound Exposure: Using a pintool or liquid handler, transfer compounds from a library (e.g., annotated or diversity libraries) to the assay plates. Include controls (e.g., DMSO for vehicle, Bortezomib for full cytotoxicity) [4].

- Real-Time Kinetic Monitoring: Continuously monitor impedance, often at a specific frequency (e.g., 150 kHz), for a duration of 48-72 hours. The impedance value is directly related to cell number, adhesion, and morphology [25] [4] [30].

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize raw impedance data to the pre-treatment baseline.

- Generate concentration-response curves and fit them using a four-parameter logistic model to determine EC₅₀ and efficacy values [4].

- Classify compounds based on their cytotoxic kinetic profiles (e.g., rapid cytolysis vs. slow anti-proliferative effects).

Protocol 2: Multiparametric Label-Free Assay for Dynamic Cell Assessment

This protocol combines impedance with other techniques, such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), for a more comprehensive analysis of cell status under toxic insult [25].

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Combined System: A biosensing platform capable of simultaneous EIS and SPR measurements [25].

- Cells: Adherent cell lines capable of forming tight junctions (e.g., renal, endothelial) [25].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Culture on Sensor: Grow a confluent monolayer of cells directly on the sensor surface that supports both EIS and SPR.

- Establish Barrier Function: Confirm the development of tight junctions, which is indicated by a stable, high impedance baseline and a specific SPR signature [25].

- Toxic Insult Exposure: Introduce the cytotoxic compound or bioactive substance (e.g., calcium oxalate crystals, amyloid fibrils) to the cell medium [25].

- Simultaneous Multiparametric Recording:

- EIS: Monitor changes in cell-substrate adherence and the integrity of cell-cell connections.

- SPR/Optical Biosensor: Monitor dynamic mass redistribution and cytoskeletal remodeling within the cells [25].

- Data Fusion and Interpretation:

- Correlate the EIS and SPR kinetic data to deconvolve the complex cellular response.

- For example, a biphasic response upon exposure may correspond to an initial change in cell-substrate adherence followed by a later change in cell-cell tightening [25].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Cytotoxicity Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CellTiter-Glo Assay | Measures ATP content as a marker of metabolic activity and cell viability [4]. | End-point determination of cytotoxicity in high-throughput screening [4]. |

| Quinacrine (Mepacrine) | Fluorescent dye used to label platelets or cellular components for imaging [30]. | Real-time visualization of thrombus formation in impedance/imaging fusion biosensors [30]. |

| PPACK (D-Phenylalanyl-L-Prolyl-L-Arginine Chloromethyl Ketone) | Direct thrombin inhibitor; anticoagulant for blood sample preparation [30]. | Prevents blood coagulation in assays studying platelet adhesion and thrombus formation under flow [30]. |

| Type I Collagen | Protein substrate that induces platelet aggregation and adhesion [30]. | Used to coat microchannels in thrombosis-on-a-chip models to simulate a damaged vessel wall [30]. |

| Sodium Citrate Buffer (pH 6.0) | Common buffer used for heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) [26]. | Unmasking target antigens in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections for IHC staining [26]. |

| Engineered Cell Reporters | Cells with synthetic gene circuits that enhance or tailor reactivity to specific stimuli [25]. | Creating highly sensitive and specific live-cell biosensors for targeted cytotoxic pathways [25]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Organoid Culture Challenges

Q1: My patient-derived colorectal organoids show poor growth efficiency and low viability. What could be the cause and how can I improve this?

A: Poor organoid growth often stems from issues with initial tissue processing and handling. Based on standardized protocols for colorectal organoids, the following solutions are recommended [31]:

- Critical Tissue Handling: Ensure samples are transferred in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with antibiotics immediately after collection. Processing delays significantly reduce cell viability [31].

- Appropriate Preservation: Select preservation method based on expected processing delay:

- Matrix Optimization: Ensure proper Matrigel concentration and distribution. Inhomogeneous matrix embedding creates suboptimal growth environments [32].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Organoid Viability Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low cell viability | Delay in tissue processing | Process immediately or use appropriate preservation method | 20-30% improvement in viability [31] |

| Necrotic cores | Limited nutrient diffusion | Use organoids-on-chip with perfusion | Enhanced viability and extended culture [33] |

| High heterogeneity | Uncontrolled self-assembly | Implement automated liquid handling systems | Improved reproducibility and consistency [32] |

| Limited maturation | Lack of environmental cues | Incorporate mechanical stimulation in OoC platforms | Better functional maturation and physiology [33] |

Q2: My organoid models lack physiological complexity and fail to recapitulate native tissue functions. How can I enhance their functional maturity?

A: Limited organoid maturity is a common challenge that can be addressed through several engineering approaches [32]:

- Integrate Multiple Cell Types: Co-culture epithelial organoids with mesenchymal cells, immune cells, or endothelial cells to better mimic the tissue microenvironment [32].

- Provide Physiological Cues: Incorporate mechanical stimulation (fluid flow, stretching), electrical stimulation (for neural/cardiac models), or biochemical gradients to promote maturation [33].

- Extend Culture Duration: Allow extended differentiation time (e.g., 6-9 months for brain organoids to model later developmental stages) [33].

- Utilize Organ-on-Chip Technology: Microfluidic platforms provide continuous perfusion, mechanical stimuli, and tissue-tissue interfaces that enhance functional maturation [33] [34].

Organ-on-a-Chip Implementation Issues

Q3: When implementing organ-on-a-chip systems for cytotoxicity screening, I encounter high variability between devices. How can I improve reproducibility?

A: OoC variability often stems from inconsistent device fabrication and cell culture conditions. Implement these strategies [33] [32]:

- Standardized Fabrication: Use consistent PDMS curing protocols and quality control measures for chip production [33].

- Automated Fluid Handling: Implement automated perfusion systems to minimize operator-dependent variability in flow rates and medium changes [32].

- Quality Control Checkpoints:

- Integrated Sensors: Incorporate miniature biochemical sensors for real-time monitoring of metabolic parameters (O₂, pH, glucose) to ensure consistent culture conditions [32].

Q4: How can I model multi-organ interactions for systemic cytotoxicity assessment in organ-on-a-chip platforms?

A: Modeling organ-organ interactions requires integrated multi-OoC systems [33] [34]:

- Physiologically-Based Design: Scale organ compartments according to human physiological ratios (tissue size, fluid volumes) [35].

- Vascular Coupling: Create a shared circulatory network that allows communication via endothelial barriers while maintaining tissue-specific compartments [33].

- Sequential Dosing: Implement programmable flow patterns that mimic pharmacokinetic profiles after drug administration [35].

- Sensitive Endpoint Detection: Utilize integrated biosensors and high-content imaging to capture inter-organ signaling and distant toxic effects [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing Patient-Derived Colorectal Cancer Organoids for Phenotypic Screening

Background: This protocol enables generation of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from colorectal tissues for high-content cytotoxicity screening, maintaining tumor heterogeneity and patient-specific drug responses [31].

Materials: Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Organoid Culture

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Medium | Advanced DMEM/F12 | Foundation for culture medium |

| Essential Supplements | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin1 (L-WRN conditioned medium) | Maintain stem cell growth and differentiation [31] |

| Matrix | Matrigel (Basement Membrane Matrix) | Provides 3D structural support mimicking extracellular matrix [31] |

| Tissue Dissociation | Collagenase/Dispase enzyme mix | Liberates crypts and stem cell units from tissue samples [31] |

| Antibiotics | Penicillin-Streptomycin (100 U/mL) | Prevents microbial contamination [31] |

| Cryopreservation | DMSO (10%) in FBS (10%) with 50% L-WRN medium | Preserves tissue/cells for long-term storage [31] |

Step-by-Step Methodology [31]:

Tissue Procurement and Processing:

- Collect human colorectal tissue samples under sterile conditions immediately following surgical resection or biopsy.

- Transfer samples in 5-10 mL cold Advanced DMEM/F12 with antibiotics.

- Critical: Process within 1-2 hours or use validated preservation methods.

Crypt Isolation:

- Wash tissue 3x with cold PBS containing antibiotics.

- Mince tissue into <1 mm³ fragments using sterile scalpels.

- Digest with collagenase solution (2 mg/mL) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Filter through 100 μm strainer to separate crypts from single cells and debris.

Organoid Culture Establishment:

- Mix isolated crypts with Matrigel (approximately 500-1000 crypts/50 μL dome).

- Plate as domes in pre-warmed culture plates and polymerize for 20 minutes at 37°C.

- Overlay with complete intestinal organoid medium containing EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, and other essential factors.

- Culture at 37°C with 5% CO₂, changing medium every 2-3 days.

Passaging and Expansion:

- Mechanically disrupt organoids every 7-14 days using gentle pipetting.

- Re-embed fragments in fresh Matrigel at appropriate dilution (typically 1:3-1:6 split ratio).

Quality Control:

- Verify organoid morphology: presence of crypt-like structures with bud formation.

- Confirm viability >80% via live/dead staining.

- Validate epithelial identity through immunofluorescence for cytokeratins.

Protocol: Integrating Organoids with Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Platform

Background: This protocol describes the integration of pre-formed organoids into microfluidic chips to enhance physiological relevance for cytotoxicity screening applications [33].

Materials:

- Pre-formed organoids (7-14 days old)

- Microfluidic OoC device (commercial or custom-fabricated)

- ECM solution (Matrigel or collagen I)

- Perfusion medium (organ-specific)

- Programmable syringe pump or pneumatic perfusion system

- Tubing and connectors compatible with microfluidics

Step-by-Step Methodology [33]:

Organoid Preparation:

- Harvest organoids from conventional 3D culture.

- Gently break down into appropriate size fragments (50-200 μm diameter).

- Resuspend in diluted ECM solution (Matrigel reduced to 4-6 mg/mL concentration).

Chip Loading:

- Introduce organoid-ECM suspension into microfluidic culture chamber via inlet port.

- Allow ECM polymerization at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Connect to perfusion system primed with culture medium.

Perfusion Culture Establishment:

- Initiate low flow rate (0.1-1 μL/min) for 24 hours to allow organoid acclimation.

- Gradually increase to physiological flow rates (2-5 μL/min) over 48 hours.

- Maintain continuous perfusion with medium replacement every 24-48 hours.

System Validation:

- Confirm organoid viability after 72 hours of perfusion using live/dead staining.

- Verify physiological morphology and polarization (apical-basal orientation when applicable).

- Assess barrier function if relevant (TEER measurements for epithelial models).

Compound Screening:

- Introduce test compounds through perfusion system at physiologically relevant concentrations.

- Implement real-time monitoring using integrated sensors or endpoint analyses.

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive cytotoxicity controls).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q5: What are the key advantages of using phenotypic screening in cytotoxicity assessment compared to target-based approaches?

A: Phenotypic screening offers several distinct advantages for cytotoxicity assessment [2] [36]:

- Identification of Novel Mechanisms: Enables discovery of unexpected therapeutic targets and mechanisms of action without predetermined target hypotheses [2].

- Pathway Context: Evaluates compound effects within complete biological pathways and cellular networks, revealing complex polypharmacology [2].

- First-in-Class Potential: Historically, phenotypic screening has been more successful at generating first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms [2] [36].

- Human Relevance: When using human-derived organoids, provides more clinically predictive data compared to animal models or simplified cell systems [36].

Q6: How do I determine whether my cytotoxicity findings in organoid models are physiologically relevant?

A: Establish these validation criteria for physiological relevance [32] [34]:

- Benchmarking: Compare compound responses to known clinical profiles (IC₅₀ values, therapeutic indices).

- Multiple Endpoints: Assess various cytotoxicity parameters (apoptosis, necrosis, metabolic inhibition, functional impairment) rather than single metrics.

- Histological Correlation: Verify that morphological changes in organoids mirror tissue responses observed in clinical specimens.

- Biomarker Concordance: Confirm that molecular markers of toxicity (e.g., stress response genes, damage-associated molecules) align with clinical toxicity signatures.

Q7: What are the current limitations in using advanced model systems for regulatory decision-making in drug development?

A: While rapidly evolving, current limitations include [32] [34]:

- Standardization Challenges: Lack of standardized protocols and quality control metrics across laboratories.

- Validation Gaps: Limited comprehensive validation against clinical outcomes for specific toxicity endpoints.

- Regulatory Acceptance: Evolving but not yet complete regulatory frameworks for accepting data from these novel platforms.

- Technical Complexity: Requirement for specialized expertise and infrastructure that may limit widespread adoption.

- Throughput Limitations: Despite improvements, most complex OoC systems have lower throughput than traditional 2D models.

However, regulatory attitudes are shifting, with recent FDA approvals incorporating OoC data supporting clinical trials, particularly for rare diseases where traditional models are inadequate [34].

Q8: What computational approaches can enhance the predictive power of cytotoxicity data from advanced model systems?

A: Several computational methods can augment phenotypic screening data [2] [36]:

- Multiparametric Analysis: Use machine learning algorithms to identify complex patterns in high-content screening data that predict clinical toxicity.

- Pathway Mapping: Integrate cytotoxicity data with known signaling pathways to identify vulnerable biological processes.

- Kinetic Modeling: Develop quantitative systems pharmacology models that simulate temporal compound effects and recovery dynamics.

- Cross-Species Translation: Build computational frameworks that translate findings between model systems and human physiology.

- Toxicity Prediction: Train classifiers on historical screening data to flag compounds with high probability of adverse effects.

Table 3: Comparison of Advanced Model Systems for Cytotoxicity Screening

| Parameter | 2D Monolayers | 3D Organoids | Organ-on-Chip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low | Moderate to High | High |

| Throughput Capacity | High (384+ well) | Moderate (96-384 well) | Low to Moderate (varies) |

| Complexity | Single cell type | Multiple cell types, self-organized | Multiple tissues, vascular perfusion |

| Cost per Data Point | Low | Moderate | High |

| Reproducibility | High | Moderate (batch variation) | Improving with standardization |

| Mechanistic Insight | Pathway-specific | Tissue context | Organ-level, systemic |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established | Growing | Emerging |

| Best Use Case | Primary screening, mechanism | Disease modeling, efficacy | ADMET, systemic toxicity |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary differences between phenotypic and target-based screening approaches, and when should I use each?

A1: The choice between phenotypic and target-based screening is foundational to your discovery strategy [9].

- Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) identifies compounds based on a measurable biological response in a cell-based or whole-organism context, without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target [9]. This approach is powerful for uncovering novel biology and first-in-class therapies, as it captures the complexity of cellular systems and can reveal unanticipated mechanisms of action [9]. It is particularly useful when the underlying disease pathways are poorly characterized.

- Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) begins with a predefined, well-characterized molecular target (e.g., a specific enzyme or receptor) [9]. This approach allows for rational drug design, leveraging high-resolution structural biology to optimize compounds for specificity and potency [9].

The following table summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Measurable biological effect or phenotype [9] | Pre-validated molecular target [9] |

| Key Advantage | Unbiased discovery of novel targets and mechanisms; captures system complexity [9] [37] | Rational design; typically simpler optimization and validation [9] |

| Main Challenge | Requires subsequent target deconvolution, which can be complex and time-consuming [9] | Relies on a correct target hypothesis; may fail if the target is not disease-relevant in vivo [9] |

| Ideal Use Case | Identifying first-in-class drugs; complex diseases with multifactorial etiology [9] [37] | Optimizing compounds for a known pathway; developing best-in-class drugs [9] |

Q2: Our HTS campaign yielded an overwhelming number of hits. What are the critical first steps in triaging these for a cytotoxicity phenotypic screen?

A2: Effective hit triage is crucial for prioritizing the most promising candidates. A multi-parameter filtering approach is recommended.

- Confirm Activity: Begin with a dose-response confirmation assay to verify the initial hit and determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). This eliminates false positives from single-concentration screening.

- Assess Specificity and Safety: Test confirmed hits in counter-screens. For cytotoxicity screening, this includes assessing the effect on non-malignant or primary cell lines (e.g., astrocytes, CD34+ progenitor cells) to identify compounds with selective toxicity towards diseased cells [38].

- Evaluate Assay Interference: Rule out pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) and other non-specific inhibitors that can generate false positives through mechanisms like colloidal aggregation or fluorescence [39].

- Analyse Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR): Cluster hits by chemical structure. If several structurally similar compounds show activity, it strengthens the validity of the hit series and provides a starting point for medicinal chemistry optimization.

Q3: What are the best practices for quality control (QC) in a high-throughput kinetic profiling assay?

A3: Robust QC measures are non-negotiable for generating reliable HTS data. These measures fall into two main categories [40]:

- Plate-Based Controls: These characterize the performance of the entire assay plate and help identify technical artifacts.

- Include maximum effect (e.g., 100% cell death control), minimum effect (vehicle/negative control), and if possible, a reference compound control on every plate.

- Monitor for spatial effects like the "edge effect," caused by evaporation from wells at the plate's periphery, which can lead to inconsistent results [40].

- Sample-Based Controls: These characterize the variability in biological responses.

- Use statistical tools like the Z'-factor to assess the quality and robustness of the assay itself. A Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally considered an excellent assay.

- The minimum significant ratio (MSR) is another QC tool that measures assay reproducibility and characterizes the potencies of controls or samples between different assay runs [40].

Q4: How can we integrate multi-omics data to deconvolute the mechanism of action for a phenotypically active hit?

A4: Integrating multi-omics technologies is a powerful strategy for linking a phenotypic outcome to its underlying molecular mechanism [9]. After identifying a robust hit, you can:

- Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq): Profile the global gene expression changes in cells treated with your hit compound versus a vehicle control. This can reveal which pathways are being up- or down-regulated, providing a hypothesis for the Mechanism of Action (MoA) [38].

- Proteomics (Thermal Proteome Profiling): This method identifies direct protein targets by measuring which proteins become stabilized or destabilized upon compound binding when subjected to a heat gradient. It is a direct way to identify the proteins engaged by your hit [38].

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): Using antibodies, this assay can confirm the binding of the compound to specific targets that emerged from the thermal proteome profiling study [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Variability and Poor Reproducibility in HTS Readouts

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High well-to-well or plate-to-plate variability in signal. | Inconsistent liquid handling due to pipetting errors or clogged tips. | Calibrate automated liquid handlers regularly. Use visual or gravimetric checks to verify dispensed volumes. |

| Evaporation, leading to "edge effects." | Use microplates with seals or lids. Employ atmospheric control in incubators. Use assay buffers with low evaporation potential. | |

| Cell seeding density inconsistency. | Standardize cell counting methods and ensure a homogeneous cell suspension during seeding. Use automated cell counters. | |

| Low Z'-factor (<0.5). | High background signal or low signal-to-noise ratio. | Optimize assay reagent concentrations and incubation times. Switch to a more sensitive detection method (e.g., luminescence over absorbance). |

| High variance in positive or negative controls. | Ensure control compounds are fresh and prepared accurately. Check for contamination in cell cultures or reagents. |

Issue: Hit Confirmation and Validation Failures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hits from primary screen fail to show dose-response in confirmation. | The primary screen had a high false-positive rate. | Implement stricter hit-selection criteria in the primary screen (e.g., use of normalised percent inhibition and setting a robust Z-score threshold). |

| Compound instability or precipitation. | Check compound solubility in the assay buffer. Use fresh DMSO stocks and ensure proper storage conditions. | |

| Cytotoxic hits are also toxic to non-malignant cells. | The compound has a non-selective, generic mechanism of cytotoxicity. | Perform counter-screens on relevant primary or non-transformed cell lines early in the triage process [38]. This identifies and filters out non-selective compounds. |

| Potency decreases in more physiologically relevant (3D) models. | Poor compound penetration into spheroids/organoids. | Consider the compound's physicochemical properties. Extend treatment durations to allow for deeper tissue penetration. |

| The 3D model introduces microenvironmental factors (e.g., hypoxia, quiescence) that reduce efficacy. | Validate your 3D model to ensure it represents the key features of the tumor. Use longer exposure times or combination therapies. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol: High-Throughput Kinetic Profiling of Cytotoxicity in 3D Spheroids

Objective: To dynamically monitor the cytotoxic effects of compound libraries on patient-derived glioblastoma (GBM) spheroids over time, generating rich kinetic data (e.g., IC50 over time).

Materials: