Intrinsic Resistance Unplugged: The Definitive Guide to Bacterial Efflux Pumps in Antimicrobial Defense

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role efflux pumps play as a primary mechanism of intrinsic antimicrobial resistance in bacteria.

Intrinsic Resistance Unplugged: The Definitive Guide to Bacterial Efflux Pumps in Antimicrobial Defense

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role efflux pumps play as a primary mechanism of intrinsic antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on pump structure, classification, and physiological functions with advanced methodological approaches for their study. The content further explores the challenges efflux poses in clinical settings and drug development, detailing current strategies to circumvent this resistance, including the development of efflux pump inhibitors and the design of evader compounds. By integrating validation frameworks and comparative analyses of key pathogen-specific pumps, this resource offers a roadmap for overcoming one of the most significant barriers in modern antimicrobial therapy.

The Essential Gatekeepers: Deconstructing Efflux Pump Biology and Intrinsic Resistance Mechanisms

Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents represents a critical challenge to global public health, undermining the efficacy of conventional treatments and complicating therapeutic interventions. This resistance manifests through two primary pathways: intrinsic resistance, an innate, inherited characteristic of a bacterial species, and acquired resistance, which occurs through genetic mutations or horizontal gene transfer from other organisms [1] [2]. Within the framework of bacterial defense strategies, intrinsic resistance mechanisms constitute the "first line of defense," providing immediate protection against antimicrobial agents without prior exposure [3]. Among these mechanisms, efflux pumps stand as fundamental components of intrinsic resistance, actively extruding toxic compounds from bacterial cells and substantially reducing intracellular antibiotic concentrations [4] [5]. This whitepaper delineates the distinctions between intrinsic and acquired resistance, with particular emphasis on the structural and functional roles of efflux pumps as primary defensive apparatuses, while providing technical methodologies for investigating these systems in research settings.

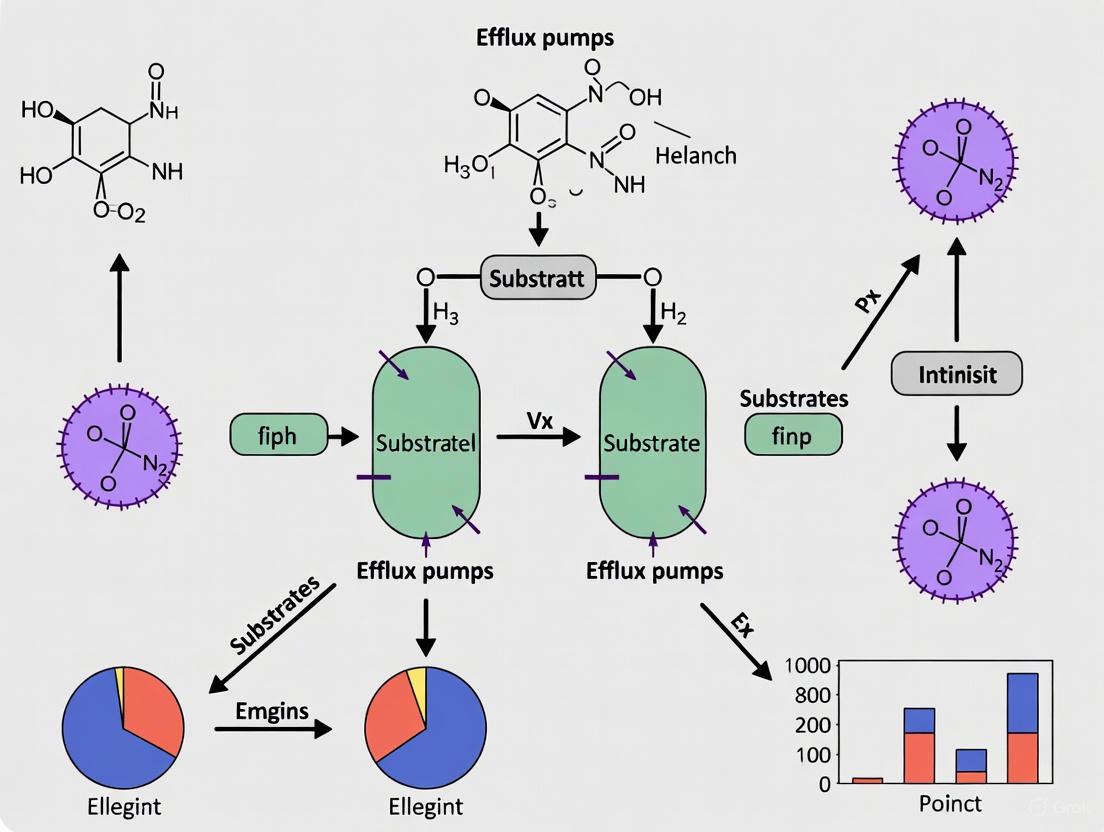

The following conceptual framework illustrates the sequential nature of bacterial defense lines, positioning intrinsic efflux systems as the foundational protective barrier:

Fundamental Concepts: Intrinsic Versus Acquired Resistance

Definitional Distinctions and Key Characteristics

Bacterial resistance mechanisms demonstrate remarkable diversity in origin and function, with intrinsic and acquired resistance representing fundamentally distinct evolutionary adaptations:

Intrinsic Resistance refers to the innate, chromosomally encoded capacity of a bacterial species to withstand antimicrobial agents without prior exposure [1] [2]. This form of resistance is a universal trait within a species, independent of horizontal gene transfer, and results from the inherent structural or functional characteristics of the microorganism [1]. For instance, Gram-negative bacteria exhibit intrinsic resistance to vancomycin due to their outer membrane impermeability to large glycopeptide molecules, while anaerobic bacteria display natural resistance to aminoglycosides because they lack the oxygen-dependent transport system required for drug uptake [1] [2].

Acquired Resistance emerges in previously susceptible bacterial populations through genetic alterations that may occur via mutation in existing genes or acquisition of new genetic material through horizontal gene transfer mechanisms (conjugation, transduction, or transformation) [1] [2]. This form of resistance is strain-specific rather than species-wide and develops in response to selective pressure from antimicrobial exposure. Notable examples include the acquisition of the mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which confers resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, and the plasmid-mediated acquisition of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes in Enterobacteriaceae [6] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Intrinsic Versus Acquired Resistance

| Characteristic | Intrinsic Resistance | Acquired Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Chromosomal genes present in all members of a species | Mutations or acquired genetic elements (plasmids, transposons) |

| Scope | Species-wide | Strain-specific |

| Dependence on Prior Antibiotic Exposure | Independent | Dependent |

| Transferability | Vertical inheritance only | Horizontal gene transfer possible |

| Examples | Vancomycin resistance in Gram-negative bacteria; β-lactam resistance in Klebsiella spp. | MRSA (mecA gene); ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae |

| Overcoming Strategies | Drug design bypassing inherent barriers | Combination therapy; antimicrobial stewardship |

The Resistance Continuum: From Intrinsic to Multidrug Resistance

Bacterial resistance exists along a spectrum, with intrinsic resistance representing the foundational layer upon which additional resistance mechanisms can accumulate. When bacteria acquire multiple resistance determinants, they may progress to become multidrug-resistant (MDR), defined as resistance to three or more antimicrobial categories [2]. Further accumulation of resistance mechanisms can lead to extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) phenotypes, creating significant therapeutic challenges [2]. Efflux pumps play a particularly insidious role in this progression, as their broad substrate specificity can confer resistance to multiple antibiotic classes simultaneously, thereby facilitating the selection of additional, more specific resistance mechanisms [5] [7].

Efflux Pumps: Architects of Intrinsic Resistance

Structural Classification and Functional Mechanisms

Efflux pumps are active transporter proteins embedded in bacterial membranes that extrude toxic substances, including antibiotics, from the cellular interior. These systems are phylogenetically categorized into six major superfamilies based on their structure and energy coupling mechanisms [5] [8] [9]:

Table 2: Major Efflux Pump Superfamilies in Bacteria

| Superfamily | Energy Source | Primary Organisms | Representative Pumps | Key Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) | Proton motive force | Gram-negative | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli), AdeABC (A. baumannii) | Broad spectrum: β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines |

| MFS (Major Facilitator Superfamily) | Proton motive force | Gram-positive and Gram-negative | EmrB (E. coli), NorA (S. aureus) | Fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol |

| ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) | ATP hydrolysis | Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative | MacAB-TolC (E. coli) | Macrolides, polypeptides |

| SMR (Small Multidrug Resistance) | Proton motive force | Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative | EmrE (E. coli) | Disinfectants, dyes, some antibiotics |

| MATE (Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion) | Sodium or proton gradient | Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative | NorM (V. cholerae) | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides |

| PACE (Proteobacterial Antimicrobial Compound Efflux) | Proton motive force | Gram-negative | AceI (A. baumannii) | Chlorhexidine, other biocides |

The tripartite architecture of Gram-negative efflux systems, particularly well-characterized in RND family pumps, exemplifies the structural sophistication of these intrinsic resistance mechanisms. Systems such as AcrAB-TolC (E. coli) and AdeABC (A. baumannii) span both the inner and outer membranes, comprising three essential components: an inner membrane transporter (e.g., AcrB) that recognizes substrates and couples extrusion to proton influx; a periplasmic adapter protein (e.g., AcrA) that bridges the inner and outer membrane components; and an outer membrane channel (e.g., TolC) that forms an exit conduit for extruded compounds [5] [8]. This tripartite organization enables direct extrusion of substrates from the cytosol or periplasm to the extracellular environment, bypassing both membrane barriers efficiently.

Molecular Mechanisms of Substrate Extrusion

RND efflux pumps operate through a sophisticated rotational mechanism in which each proton that enters the cell drives the conformational changes necessary to export one substrate molecule [5]. The AcrB trimer, the prototypical RND transporter, exhibits functional asymmetry with its three protomers cycling consecutively through loose (L), tight (T), and open (O) conformations [8]. This cyclic conformational change creates a peristaltic motion that propels substrates from the binding pockets through the channel to the extracellular space. Substrate recognition involves multiple substrate-binding pockets with broad specificity, recognizing compounds based on physicochemical properties like hydrophobicity and aromaticity rather than specific molecular structures [7] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the operational mechanism of the tripartite AcrAB-TolC efflux system:

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Efflux-Mediated Resistance

Quantitative Assessment of Antibiotic Accumulation

Determining intracellular antibiotic concentrations provides direct evidence of efflux pump activity. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers a highly sensitive approach for quantifying antibiotic accumulation in bacterial cells [4].

Protocol: LC-MS-Based Antibiotic Accumulation Assay

Bacterial Culture and Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Mycobacterium abscessus ATCC19977) to mid-logarithmic phase in appropriate medium. Harvest cells by centrifugation (3,500 × g, 10 minutes) and wash twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or assay buffer.

Antibiotic Exposure: Resuspend bacterial pellets to a standardized optical density (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) in pre-warmed medium containing the target antibiotic at clinically relevant concentrations (typically 1-10× MIC). Include control samples without antibiotics for background subtraction.

Incubation and Sampling: Incimate the bacterial suspension with shaking at optimal growth temperature. Remove aliquots at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes) and immediately separate cells from medium by rapid filtration (0.45 μm pore size filters) or silicone oil centrifugation.

Sample Processing: Lyse cell pellets using a combination of mechanical disruption (bead beating) and chemical lysis in acetonitrile:water (70:30) containing internal standards. Remove cellular debris by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 15 minutes, 4°C).

LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separate analytes using reverse-phase C18 columns with gradient elution (mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile).

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode with electrospray ionization. Use antibiotic-specific transitions for quantification.

Data Analysis: Calculate intracellular antibiotic concentrations using standard curves of pure antibiotics normalized to protein content or cell count. Express accumulation as the ratio of intracellular to extracellular drug concentration over time [4].

Genetic Screening for Efflux Components

Transposon mutagenesis coupled with next-generation sequencing (Tn-Seq) enables genome-wide identification of genetic determinants contributing to efflux-mediated resistance.

Protocol: Transposon Mutagenesis Screening for Efflux Determinants

Transposon Library Construction: Generate a comprehensive transposon mutant library using a mariner-based transposon system (e.g., Himar1) delivered via phage or conjugation. Achieve coverage of >100,000 independent insertion mutants to ensure comprehensive genome coverage.

Selection Pressure: Divide the mutant library and expose to sub-inhibitory and inhibitory concentrations of target antibiotics (e.g., linezolid for M. abscessus [4]). Include an untreated control pool cultured in parallel.

Library Harvest and DNA Preparation: After 24-48 hours of antibiotic exposure, harvest bacterial cells from both treated and control conditions. Extract genomic DNA using a method that preserves short fragments (e.g., phenol-chloroform extraction).

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Fragment genomic DNA by sonication or enzymatic digestion.

- Add sequencing adapters using ligation or transposase-based methods.

- Amplify transposon-chromosome junctions using primers specific to the transposon ends.

- Sequence amplified libraries using Illumina platforms to obtain >10 million reads per condition.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map sequencing reads to the reference genome to identify transposon insertion sites.

- Compare insertion abundance between antibiotic-treated and control conditions using specialized software (e.g., TRANSIT, ESSENTIALS).

- Identify genes with significantly depleted insertions under antibiotic selection, indicating essentiality for survival under antibiotic pressure.

Validation: Confirm hits by constructing defined deletion mutants and complementation strains, then reassessing antibiotic susceptibility profiles [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Efflux Pump Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Efflux Pump Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Escherichia coli K-12; Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606; Mycobacterium abscessus ATCC 19977 | Comparative studies of efflux pump conservation and function | Select strains with well-annotated genomes and genetic tractability |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN); Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP); Verapamil | Functional assessment of efflux activity through potentiation assays | Use appropriate solvent controls; CCCP depletes proton motive force non-specifically |

| Fluorescent Substrates | Ethidium bromide; Hoechst 33342; Rhodamine 6G | Real-time monitoring of efflux activity via fluorometry | Optimize loading concentrations; confirm specificity with inhibitor controls |

| Genetic Tools | Himar1 transposon system; CRISPRI knockdown; Plasmid-based overexpression vectors | Genetic dissection of efflux pump components and regulators | Include appropriate antibiotic resistance markers for selection |

| Antibiotic Panels | Fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, macrolides | Substrate specificity profiling | Use clinical isolates with defined resistance profiles for comparison |

| Analytical Standards | Isotope-labeled antibiotic internal standards (e.g., ¹³C-levofloxacin) | LC-MS quantification of intracellular drug accumulation | Ensure chromatographic separation of analogs and metabolites |

Efflux pumps represent a fundamental component of the bacterial intrinsic resistance arsenal, serving as an essential first line of defense against antimicrobial agents. Their structural complexity, broad substrate specificity, and genetic conservation across bacterial species make them formidable barriers to antibiotic therapy. The distinction between intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance, as each demands different therapeutic approaches. For intrinsic resistance mediated by efflux, potential solutions include the development of efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) to be used as antibiotic adjuvants, design of novel antibiotics that bypass efflux systems, or manipulation of efflux pump expression. The methodological frameworks presented herein provide robust approaches for investigating these resistance mechanisms, enabling researchers to quantify antibiotic accumulation, identify genetic determinants of efflux, and screen for potential inhibitors. As the antimicrobial resistance crisis intensifies, understanding and targeting the first line of bacterial defense—intrinsic resistance mechanisms like efflux pumps—will be paramount in developing the next generation of effective antibacterial therapies.

Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) efflux pumps represent sophisticated tripartite molecular assemblies that traverse the entire cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria, constituting a primary mechanism of intrinsic multidrug resistance. These protein complexes function as specialized architectural constructs with precisely engineered components spanning from the inner to the outer membrane. This technical review delineates the structural blueprint and functional dynamics of RND efflux pumps, with particular emphasis on the paradigm systems MexAB-OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and AcrAB-TolC of Escherichia coli. We provide detailed experimental methodologies for studying these complexes, alongside quantitative analyses of their components and functions. Understanding these intricate membrane-spanning structures provides critical insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies to counteract multidrug resistance in pathogenic bacteria.

Structural Architecture of RND Efflux Pumps

RND efflux pumps exemplify remarkable structural engineering, forming continuous conduits that export antimicrobial compounds directly from the bacterial cell. These tripartite complexes comprise three essential components that collaboratively span the entire Gram-negative cell envelope [10].

Table 1: Core Components of RND Efflux Pumps

| Component | Location | Structural Features | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Membrane Transporter (e.g., AcrB, MexB) | Inner membrane | Homo-trimer with 12 transmembrane α-helices per monomer; large periplasmic domain (~7 nm) | Substrate recognition and proton antiport; primary engine of the efflux system |

| Periplasmic Adaptor Protein (e.g., AcrA, MexA) | Periplasmic space, anchored to inner membrane | Tetratricopeptide repeat domains; α-helical hairpin; lipoyl domain | Structural and functional coupling between inner and outer membrane components |

| Outer Membrane Channel (e.g., TolC, OprM) | Outer membrane | Homo-trimeric β-barrel transmembrane domain; periplasmic α-helical tunnel (~10 nm) | Final efflux duct for substrate extrusion into extracellular space |

The inner membrane transporter (IMP) component serves as the engine of the efflux system. MexB and AcrB form trimers where each protomer contains a transmembrane domain of 12 α-helices that facilitates proton translocation, and a large periplasmic portion comprising porter and funnel domains that extend approximately 7 nm into the periplasm [11]. This periplasmic domain is responsible for substrate recognition and initial capture.

The outer membrane factor (OMF) component, exemplified by OprM and TolC, exhibits a distinctive trimeric organization featuring a 4-nm-long transmembrane domain forming a β-barrel structure, complemented by a 10-nm-long periplasmic domain consisting of 12 α-helices and a mixed α/β equatorial domain [11]. This architecture creates a sealed conduit spanning the outer membrane and periplasmic space.

Linking these membrane-embedded components, the periplasmic adaptor protein (PAP) or membrane fusion protein forms critical connections between the IMP and OMF. MexA/AcrA proteins are arranged in four consecutive domains: membrane proximal, β-barrel, lipoyl, and α-helical hairpin domains, with anchoring to the inner membrane via palmitoylation of an N-terminal cysteinyl residue [11]. Recent evidence suggests these adaptor proteins may form hexameric assemblies when binding to their respective outer membrane channels, creating an extended funnel structure [12].

Assembly and Functional Dynamics

Tripartite Complex Assembly

The assembly of RND efflux pumps represents a sophisticated process wherein individually stable components form a functional complex without direct physical interaction between the inner and outer membrane components [11]. The periplasmic adaptor protein serves as the crucial architectural element bridging this intermembrane space.

Single-particle electron microscopy studies of reconstituted native P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM and E. coli AcrAB-TolC complexes reveal elongated structures measuring approximately 33 nm along their main axis, with the inner and outer membrane protein components linked exclusively via the periplasmic adaptor protein [11]. This structural arrangement emphasizes the role of the adaptor protein as an integral part of the exit duct, with no physical contact occurring directly between the inner and outer membrane components.

Notably, these complexes demonstrate an intrinsic ability to self-assemble, evidenced by the formation of stable interspecies AcrA–MexB–TolC complexes, suggesting a conserved mechanism of tripartite assembly across bacterial species [11]. This evolutionary conservation underscores the fundamental importance of this architectural design in bacterial physiology and resistance mechanisms.

Functional Transport Mechanism

RND efflux pumps operate through a sophisticated peristaltic mechanism driven by proton motive force. The inner membrane transporter undergoes a functional rotation cycle through three distinct conformational states in each protomer:

- Loose (L) or Access state: Facilitates substrate entry from the periplasm or outer leaflet of the inner membrane

- Tight (T) or Binding state: Encloses the substrate within binding pockets

- Open (O) or Extrusion state: Directs the substrate toward the adaptor protein and outer membrane channel [12] [10]

This asymmetric conformational cycling creates a directional peristaltic motion that propels substrates through the complex. The proton motive force drives this process through protonation and deprotonation of key residues in the transmembrane domain of the IMP, with energy transduction achieved via allosteric coupling between the transmembrane and periplasmic domains [10].

Multiple substrate entry pathways have been identified, including:

- CH1 and CH4: Transmembrane grooves (between TM1/TM2 and TM7/TM8) for substrates from the membrane bilayer

- CH2: A periplasmic cleft formed by PC1/PC2 subdomains

- CH3: An interfacial channel between protomers that bypasses the access pocket [10]

These multiple entry pathways contribute to the remarkable polyspecificity of RND transporters, enabling recognition of structurally diverse compounds.

Diagram: Functional rotation mechanism of RND efflux pumps

Experimental Methodologies for Structural Analysis

Nanodisc Reconstitution Protocol

The reconstitution of native tripartite efflux complexes using lipid nanodisc technology represents a significant advancement for structural studies [11]. This methodology enables the visualization of membrane protein complexes in a near-native lipid environment.

Experimental Workflow:

Separate Membrane Protein Insertion into Nanodiscs

- Utilize two different membrane scaffold proteins (MSPs) to control complex assembly:

- MSP1D1: For outer membrane proteins (OprM/TolC) with smaller transmembrane domains (~40-55 Å diameter)

- MSP1E3D1: For inner membrane transporters (MexB/AcrB) with larger transmembrane domains (~80 Å diameter)

- Employ 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipids

- Optimize molar ratios for single molecule insertion per nanodisc:

- For OprM–ND: MSP:lipid:OprM molar ratio of 1:36:0.4

- For MexB–ND: MSP:lipid:MexB molar ratio of 1:27:1

- Utilize two different membrane scaffold proteins (MSPs) to control complex assembly:

Tripartite Complex Assembly

- Combine separately reconstituted components:

- Mix OprM–ND, MexB–ND, and lipidated MexA in 1:1:10 molar ratio

- Incubate under appropriate buffer conditions to facilitate self-assembly

- Combine separately reconstituted components:

Complex Validation

- Analyze complex formation using native PAGE electrophoresis

- Identify electrophoretic mobility shifts indicating successful complex formation

- Employ electron microscopy with negative uranyl acetate staining for structural validation

This protocol successfully demonstrates the intrinsic ability of native efflux pump components to self-assemble into functional tripartite complexes, confirmed through single-particle electron microscopy analysis [11].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide critical insights into the dynamic behavior of RND efflux pumps, complementing structural data with functional dynamics at atomic resolution [12].

Key Methodological Considerations:

- System Setup: Embed membrane protein complexes in asymmetric phospholipid bilayers with explicit solvent representation

- Simulation Parameters:

- Perform independent unbiased atomistic MD simulations (e.g., 6 × 50 ns trajectories)

- Apply periodic boundary conditions with particle-mesh Ewald electrostatics

- Maintain physiological temperature (310 K) and pressure (1 atm)

- Enhanced Sampling Techniques:

- Steered or targeted MD for probing specific conformational transitions

- Multiple copy simulations with different initial velocity distributions

- Umbrella sampling for free energy calculations along reaction coordinates

MD simulations have elucidated fundamental aspects of RND pump function, including:

- Identification of protein-internal water distributions and proton conduction pathways

- Characterization of substrate transport routes and binding pocket dynamics

- Analysis of allosteric coupling between transmembrane and periplasmic domains

- Investigation of protein-lipid interactions critical for complex stability and function [12]

Table 2: Key Insights from MD Simulations of RND Efflux Pumps

| Simulation Focus | Key Findings | Methodological Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Proton Transport | Identification of cytoplasmic and periplasmic water channels; intermediate-specific hydration patterns | Unbiased atomistic MD of asymmetric trimers with intermediate-specific protonation states |

| Substrate Pathways | Characterization of multiple substrate access channels (CH1-CH4); gating residue dynamics | Analysis of solvent pathways; steered MD for substrate translocation |

| Polyspecificity | Dynamic binding pocket architectures; multiple substrate recognition mechanisms | Docking and MD with diverse antibiotic classes; binding free energy calculations |

| Complex Assembly | Protein-lipid interactions; interfacial stability; adaptor protein conformational coupling | Coarse-grained and all-atom MD of membrane-embedded complexes |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RND Efflux Pump Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function/Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Scaffold Proteins | MSP1D1, MSP1E3D1 | Nanodisc reconstitution | Control nanodisc size for specific membrane protein insertion |

| Lipid Systems | POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) | Membrane mimetics | Provide native-like lipid environment for membrane proteins |

| Electron Microscopy Reagents | Uranyl acetate | Negative staining | Enhance contrast for single-particle EM analysis |

| Computational Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, Martini | Molecular dynamics simulations | Parameterize atomic interactions for accurate dynamics prediction |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | D13-9001, phenylalanyl-arginyl-β-naphthylamide (PAβN) | Functional characterization | Competitive and allosteric inhibition studies; therapeutic development |

| Fluorescent Substrates | Ethidium bromide, Hoechst 33342 | Transport assays | Real-time monitoring of efflux activity; inhibitor screening |

Role in Intrinsic Resistance and Clinical Implications

Within the context of intrinsic resistance, RND efflux pumps serve as first-line defense mechanisms that significantly reduce bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. In P. aeruginosa, even relatively susceptible strains actively extrude tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and fluoroquinolones, with enhanced efflux activity in strains showing elevated intrinsic resistance [13]. This fundamental role in intrinsic resistance is further demonstrated by the hypersusceptibility of mutant strains lacking functional efflux systems [13].

The clinical relevance of RND efflux pumps continues to escalate with the emergence of resistance to novel beta-lactam antibiotics and beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations [14]. Mutations in RND efflux pumps and their regulatory systems represent common adaptive mechanisms in clinical isolates, leading to increased expression or altered substrate specificity that compromises therapeutic efficacy [14]. Particularly concerning is the observation that P. aeruginosa strains with elevated intrinsic resistance overproduce specific cytoplasmic and outer membrane proteins, including components of efflux systems [13].

Beyond their role in antibiotic resistance, RND efflux pumps contribute significantly to bacterial physiology and pathogenesis through:

- Export of quorum-sensing molecules and virulence factors

- Biofilm formation and maturation

- Stress response and adaptation to hostile environments

- Heavy metal detoxification [15] [16] [10]

Diagram: Multifunctional role of RND pumps in bacterial resistance

The architectural blueprint of RND efflux pumps reveals sophisticated membrane-spanning complexes that efficiently coordinate substrate translocation from the inner membrane to the extracellular space. Their tripartite structural organization, dynamic functional mechanism, and critical role in intrinsic antibiotic resistance establish these systems as pivotal determinants of multidrug resistance in Gram-negative pathogens. Advanced experimental methodologies, including nanodisc reconstitution and molecular dynamics simulations, continue to unravel the intricate details of their assembly and operation. As clinical resistance to novel antimicrobial compounds increasingly involves efflux-mediated mechanisms, comprehensive understanding of these molecular machines provides an essential foundation for developing innovative therapeutic strategies to counteract multidrug resistance. Future research directions should focus on exploiting structural vulnerabilities in these complexes for the rational design of efflux pump inhibitors that can restore antibiotic efficacy in resistant bacterial infections.

Bacterial efflux pumps are membrane-embedded protein complexes that actively transport a wide variety of substrates—including antibiotics, toxic compounds, and metabolic byproducts—out of bacterial cells, serving as a fundamental component of intrinsic antimicrobial resistance [17]. By reducing the intracellular concentration of antibiotics below effective levels, these systems allow bacteria to survive in the presence of antimicrobial agents and create opportunities for the acquisition of more sophisticated resistance mechanisms [5] [15]. This portfolio systematically classifies the six major efflux pump families—ABC, RND, MFS, MATE, SMR, and PACE—detailing their molecular architectures, energy coupling mechanisms, substrate specificities, and roles in bacterial physiology. Understanding these systems is critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies, including efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs), to combat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections [15] [18].

Efflux Pump Family Classification and Characteristics

Bacterial efflux systems are categorized into six major families based on structural features, energy coupling mechanisms, and genetic organization [15] [17]. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of their key characteristics.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major Bacterial Efflux Pump Families

| Family | Full Name | Energy Source | Typical Structure | Primary Substrates | Physiological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC | ATP-Binding Cassette | ATP hydrolysis [15] | Tripartite complexes; Two TMDs and two NBDs [15] | Drugs, lipids, sterols [15] | Virulence, nutrient uptake, LPS/CPS export [15] |

| RND | Resistance-Nodulation-Division | Proton motive force [5] | Tripartite (IMP-MFP-OMP) [5] [14] | Broad spectrum: β-lactams, FQs, aminoglycosides, dyes [5] [14] | Virulence, biofilm formation, stress response [5] [14] |

| MFS | Major Facilitator Superfamily | Proton motive force [15] | Single component (12-14 TMS) or tripartite [18] | Structurally diverse compounds [15] | Metabolic waste removal, toxin extrusion [17] |

| MATE | Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion | Proton or sodium ion gradient [15] | Single component (12 TMS) [15] | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides [15] | Detoxification, cation export [15] |

| SMR | Small Multidrug Resistance | Proton motive force [15] | Small tetrameric (4 TMS) [15] | Lipophilic cations, dyes [15] | Quaternary amine compound resistance [15] |

| PACE | Proteobacterial Antimicrobial Compound Efflux | Proton motive force [15] | Single component (4 TMS) [15] | Chlorhexidine, acriflavine [15] | Disinfectant resistance, adaptation [15] |

Molecular Architectures and Transport Mechanisms

ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Superfamily

ABC transporters are primary active transporters that utilize energy from ATP hydrolysis to translocate substrates across cellular membranes [15]. They typically consist of two transmembrane domains (TMDs) that form the substrate conduction pathway and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) that bind and hydrolyze ATP [15]. These transporters can function as "full transporters" with all domains contained within a single polypeptide or "half transporters" that homodimerize or heterodimerize to form functional units [15]. In Gram-negative bacteria, some ABC transporters form tripartite efflux systems spanning both membranes, such as the MacAB-TolC system which includes a MacB dimer (inner membrane), hexameric MacA (periplasmic adapter protein), and a TolC trimer (outer membrane channel) [18]. ABC transporters operate via an 'alternate access' mechanism, cycling between inward-facing and outward-facing conformations to extrude substrates [15].

Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) Superfamily

RND transporters are among the most clinically significant efflux systems in Gram-negative bacteria due to their broad substrate specificity and contribution to multidrug resistance [5] [14]. These complexes form sophisticated tripartite architectures that span the entire cell envelope, consisting of an inner membrane RND transporter (e.g., AcrB, AdeB), a periplasmic adapter protein (membrane fusion protein, MFP), and an outer membrane factor (OMF) that forms an exit channel [5] [14]. The RND transporter itself typically contains 12 transmembrane segments with two large periplasmic loops that form substrate-binding domains [5]. These pumps function as proton antiporters, coupling substrate efflux to proton import via the proton motive force [5]. The transport mechanism involves sophisticated conformational cycling; in the prototypical AcrB transporter, the trimeric complex operates asymmetrically with each protomer adopting consecutive loose (L), tight (T), and open (O) conformations to create a peristaltic pumping action [18]. Substrates access binding pockets through multiple entry channels and are extruded through the central funnel domain and outer membrane channel [18].

Table 2: Characterized RND Efflux Pumps in Acinetobacter baumannii

| Efflux Pump | Regulator(s) | Genetic Location | Key Substrate Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AdeABC | AdeRS, BaeSR [5] | Chromosomal [5] | Aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, tetracyclines, tigecycline* [5] |

| AdeFGH | AdeL, ddrR, abaI [5] | Chromosomal [5] | Trimethoprim, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines [5] |

| AdeIJK | AdeN, BaeSR [5] | Chromosomal [5] | β-lactams, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, rifampin [5] |

| AdeDE | Unknown [5] | Chromosomal [5] | Meropenem, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, ceftazidime [5] |

Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS)

The MFS represents the largest known superfamily of secondary active transporters, found ubiquitously across bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [15]. These transporters typically possess 12-14 transmembrane segments and utilize proton motive force to drive substrate translocation [15]. While many MFS transporters function as single-component systems, some form tripartite efflux complexes in Gram-negative bacteria, such as EmrAB-TolC, which exports protonophores like CCCP and nalidixic acid [18]. Unlike RND pumps that primarily capture substrates from the periplasm, MFS transporters like EmrB typically interact with cytoplasmic or inner membrane-localized substrates [18].

Minor Efflux Pump Families (MATE, SMR, PACE)

The MATE family represents the most recently classified multidrug efflux transporters, utilizing either proton or sodium ion gradients to drive substrate extrusion [15]. These transporters typically contain 12 transmembrane segments and exhibit specificity for fluorochinolones and aminoglycosides [15]. The SMR family comprises the smallest multidrug resistance transporters, with typical members containing four transmembrane segments and forming homo-tetrameric complexes that use proton motive force to export lipophilic cations and various dyes [15]. The PACE family represents a more recently discovered group of transporters particularly implicated in resistance to disinfectants like chlorhexidine and to compounds like acriflavine [15].

Experimental Methodologies for Efflux Pump Characterization

Protocol 1: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination with Efflux Pump Inhibitors

Purpose: To evaluate efflux pump contribution to antibiotic resistance by measuring MIC reduction in presence of EPIs. Reagents:

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth

- Antibiotic stock solutions

- Efflux pump inhibitors (e.g., CCCP, PAβN, verapamil)

- DMSO (solvent control)

- Late-log phase bacterial culture

Procedure:

- Prepare serial two-fold dilutions of the test antibiotic in broth

- Add subinhibitory concentrations of EPI (e.g., 10-50 μg/mL for PAβN) or equivalent DMSO control

- Inoculate wells with ~5×10^5 CFU/mL bacterial suspension

- Incubate at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours

- Record MIC as lowest antibiotic concentration inhibiting visible growth

- Interpret significant efflux activity as ≥4-fold MIC reduction in EPI-containing wells versus control

Validation: Include control strains with known efflux pump overexpression and deletion mutants [18].

Protocol 2: Ethidium Bromide Accumulation Assay

Purpose: To directly measure efflux pump activity using fluorescent substrates. Reagents:

- Ethidium bromide stock solution (1 mg/mL)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate buffer

- Efflux pump inhibitors (CCCP, PAβN)

- Glucose solution (20% w/v)

- Late-log phase bacterial culture

Procedure:

- Harvest bacteria by centrifugation and wash twice with PBS

- Resuspend to OD600 of 0.2 in PBS containing 0.4% glucose

- Add ethidium bromide to final concentration of 1-5 μg/mL

- Distribute aliquots to microtiter plate with and without EPIs

- Monitor fluorescence continuously (excitation: 530 nm, emission: 600 nm)

- Calculate accumulation rates and compare between conditions

Interpretation: Increased fluorescence in EPI-treated samples indicates impaired efflux activity [18].

Protocol 3: Real-time PCR for Efflux Pump Gene Expression

Purpose: To quantify efflux pump gene expression in clinical isolates versus reference strains. Reagents:

- RNA extraction kit with DNase treatment

- cDNA synthesis kit

- SYBR Green PCR master mix

- Gene-specific primers for target efflux pumps and housekeeping genes

- Late-log phase bacterial culture

Procedure:

- Extract total RNA from bacterial cultures

- Treat with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase

- Perform qPCR with gene-specific primers

- Calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method

- Normalize to housekeeping genes (rpoB, gyrB, or recA)

Controls: Include reference strain and no-template controls [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Efflux Pump Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Efflux Pump Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | CCCP, PAβN, verapamil, D13-9001 [14] [18] | Functional characterization of efflux activity | Cytotoxicity, specificity, solvent controls required |

| Fluorescent Substrates | Ethidium bromide, Hoechst 33342, rhodamine 6G [18] | Real-time efflux activity measurements | Substrate specificity varies between pumps |

| Genetic Tools | Knockout mutants, overexpression plasmids, reporter fusions [19] | Mechanistic studies of pump regulation | Complementation controls essential |

| Antibiotic Panels | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides [5] | Substrate profiling | Include novel BL/BLI combinations [14] |

| Structural Biology Reagents | Detergents, crystallization screens, cryo-EM grids [18] | Molecular mechanism studies | Membrane protein stability challenges |

Visualizing Efflux Pump Regulation and Experimental Workflows

Efflux-Mediated Resistance Development Pathway

Diagram 1: Efflux-mediated evolution of antibiotic resistance. Research demonstrates that efflux activation under antibiotic pressure downregulates DNA repair pathways, increasing mutation frequency and accelerating fixation of resistance mutations in bacterial populations [19].

Tripartite RND Efflux Pump Architecture

Diagram 2: Tripartite RND efflux pump structure. The complex spans both membranes, with the inner membrane RND transporter (e.g., AdeB, AcrB) capturing substrates, the membrane fusion protein (MFP) bridging the periplasmic space, and the outer membrane factor (OMF) forming the exit channel [5] [14] [18].

The comprehensive classification of efflux pump families reveals sophisticated bacterial defense systems that contribute significantly to intrinsic antibiotic resistance. The ABC, RND, MFS, MATE, SMR, and PACE families represent distinct evolutionary solutions to the challenge of xenobiotic extrusion, each with unique structural features and energy-coupling mechanisms [5] [15] [17]. Beyond their role in antibiotic resistance, these systems participate fundamentally in bacterial physiology, influencing virulence, biofilm formation, stress response, and intercellular communication [15] [14]. The emerging understanding that efflux activity is genetically linked to DNA repair downregulation and accelerated evolution of resistance mutations highlights the complex role these systems play in bacterial adaptation [19]. Future research directions should prioritize the development of broad-spectrum efflux pump inhibitors that can rejuvenate existing antibiotics, standardized methodologies for clinical detection of efflux-mediated resistance, and structural-guided approaches to overcome the substrate promiscuity of these systems [15] [18]. Addressing these challenges will require interdisciplinary approaches combining structural biology, chemical genomics, and clinical microbiology to develop effective strategies against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Efflux pumps are integral membrane transporters known for their role in extruding antibiotics, thereby conferring multidrug resistance (MDR) in pathogenic bacteria [15] [9]. However, their functions extend far beyond this classical role. This whitepaper delineates the critical physiological roles of efflux pumps in bacterial virulence, biofilm formation, and stress response, framing these functions within the context of intrinsic resistance research. A comprehensive understanding of these roles is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies that target bacterial pathogenicity and resilience, potentially circumventing conventional resistance mechanisms [5] [16].

Physiological Roles of Efflux Pumps

Bacterial efflux pumps are not merely drug ejectors; they are fundamental components of bacterial physiology, adaptation, and pathogenesis. Their activity is intricately linked to the regulation of internal homeostasis, response to environmental stresses, and the expression of virulence factors.

Regulation of Virulence and Pathogenesis

Efflux pumps contribute significantly to bacterial virulence, enabling pathogens to colonize host tissues, evade immune responses, and cause disease.

- Colonization and Host Interaction: In Erwinia amylovora, the AcrAB efflux system is crucial for virulence, plant colonization, and resistance to host-produced plant toxins [9]. Similarly, in Escherichia coli, the AcrAB system pumps out bile acids and fatty acids encountered in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing their toxicity and facilitating colonization [9].

- Adhesion and Invasion: Research indicates a significant reduction in the ability of efflux pump mutants of E. coli and Salmonella enterica to adhere to and invade host cells, underscoring the role of pumps like AcrB in successful infection establishment [15].

- Virulence Factor Transport: Efflux pumps are implicated in exporting molecules essential for pathogenesis. For instance, ABC family transporters contribute to virulence by exporting components for lipopolysaccharides and capsular polysaccharides in major human pathogens [15].

Modulation of Biofilm Formation

Biofilms are structured, surface-attached bacterial communities that are highly resistant to antimicrobials. Efflux pumps are pivotal in multiple stages of biofilm development and maintenance.

- Extrusion of Biofilm-Related Molecules: Pumps actively expel toxins, metabolic waste, and, crucially, quorum sensing (QS) signals and molecules that form the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, which is critical for biofilm structure and stability [16] [20].

- Direct Regulation of Biofilm Phenotype: Studies involving efflux pump gene mutagenesis and inhibitors have demonstrated their direct impact on biofilm formation. Key systems include AcrAB-TolC in E. coli, MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa, and AdeFGH in A. baumannii [21]. Overexpression of efflux pumps in biofilm-forming bacteria is directly linked to enhanced survival and the establishment of chronic, hard-to-treat infections [16].

- Stage-Dependent Function: The role of a specific efflux pump can vary depending on the stage of biofilm formation, its expression level, and the type and concentration of substrates present in the environment [20]. This dynamic function suggests a complex regulatory network governing biofilm architecture and resilience.

Management of Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress

Inside host cells, bacteria are exposed to lethal reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated by the immune system. Efflux pumps provide a key defense mechanism against this assault.

- Stress Relief: In Acinetobacter baumannii, it is believed that Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) efflux pumps play a role in oxidative and nitrosative stress relief, enhancing bacterial survival within the host [5].

- Intramacrophage Survival: The MacAB efflux pump in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aids bacterial survival against oxidative stress encountered inside macrophages, a critical step in systemic infection [15].

Heavy Metal Detoxification and Intercellular Signaling

- Heavy Metal Resistance: Efflux pumps confer resistance to heavy metal ions such as Ag²⁺, Cu²⁺, Co²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, and Ni²⁺ by exporting them from the cell. In Gram-negative bacteria, this involves reducing concentrations in both the cytoplasm and the periplasm [15].

- Quorum Sensing and Metabolite Transport: Efflux pumps are involved in the transport of quorum sensing molecules (autoinducers), bacterial metabolites, and other intercellular communication signals, thereby influencing population-level behaviors [15] [14] [9].

Table 1: Key Physiological Functions of Bacterial Efflux Pumps Beyond Antibiotic Resistance

| Physiological Function | Mechanism of Action | Example Efflux Pump(s) | Pathogen Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence & Colonization | Resistance to host bile acids/fatty acids, adhesion, invasion, toxin export | AcrAB-TolC, AcrAB | E. coli, Erwinia amylovora, Salmonella enterica [15] [9] |

| Biofilm Formation | Extrusion of QS signals, EPS components, and toxic metabolites; direct genetic regulation | AdeFGH, AcrAB-TolC, MexAB-OprM | A. baumannii, E. coli, P. aeruginosa [21] [16] |

| Stress Response | Relief from oxidative and nitrosative stress | RND Pumps, MacAB | A. baumannii, S. enterica [5] [15] |

| Heavy Metal Resistance | Export of toxic metal ions from cytoplasm and periplasm | RND, PACE, ABC families | Various Gram-negative bacteria [15] |

| Intercellular Signaling | Transport of quorum sensing molecules and bacterial metabolites | MexAB-OprM, AcrAB-TolC | P. aeruginosa, E. coli [15] [14] |

Experimental Methodologies for Functional Analysis

Studying the non-antibiotic roles of efflux pumps requires a combination of phenotypic, genotypic, and functional assays. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments.

Assessing Efflux Pump Activity and Biofilm Formation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Efflux Pump Contribution to Biofilm Formation via Gene Inactivation

- Objective: To determine the functional role of a specific efflux pump gene in biofilm development.

- Methodology:

- Strain Construction: Create an isogenic mutant strain with a deletion or disruption of the target efflux pump gene (e.g.,

ΔadeBin A. baumannii). A complementary strain with the gene restored on a plasmid should also be generated. - Biofilm Cultivation: Grow wild-type, mutant, and complementary strains in appropriate media (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth with 1% glucose for enhanced biofilm) in static conditions using 96-well polystyrene plates for 24-48 hours at the optimal growth temperature [21].

- Biofilm Quantification:

- Remove planktonic cells and gently wash the adhered biofilm.

- Fix the biofilm with methanol or ethanol for 15 minutes.

- Stain with a 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet solution for 20 minutes.

- Wash to remove excess stain.

- Dissolve the bound crystal violet in 33% acetic acid.

- Measure the optical density at 570 nm (OD₅₇₀) using a microplate reader. A significant reduction in the mutant's OD compared to the wild-type indicates the pump's role in biofilm formation [21].

- Strain Construction: Create an isogenic mutant strain with a deletion or disruption of the target efflux pump gene (e.g.,

- Interpretation: Confirmation is achieved if the complementary strain shows restored biofilm formation, directly linking the gene to the phenotype.

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Detection of Efflux Activity Using Fluorometric Assays

- Objective: To measure the real-time efflux capability of bacterial strains.

- Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Grow bacterial cells to mid-log phase. Harvest and wash them in a buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS) at pH 7.0.

- Substrate Loading: Incubate the cell suspension with a fluorescent efflux pump substrate (e.g., Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) at 1-2 µg/mL) for 30-60 minutes to allow intracellular accumulation.

- Energy Depletion: To arrest active efflux, add an energy inhibitor like Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), a proton motive force uncoupler, to a final concentration of 10-50 µM. Incubate for an additional 10-15 minutes.

- Efflux Measurement:

- Centrifuge the cells and resuspend them in fresh, pre-warmed buffer without EtBr or CCCP.

- Immediately transfer the suspension to a quartz cuvette or a microplate.

- Monitor the fluorescence intensity over time (e.g., every 30 seconds for 10-15 minutes) using a spectrofluorometer (for EtBr: excitation 530 nm, emission 585 nm) [16] [16].

- Data Analysis: Strains with high efflux activity will show a rapid decrease in fluorescence as the substrate is extruded. The inclusion of a known efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) serves as a control to confirm the efflux mechanism.

Gene Expression Analysis in Biofilms

Protocol 3: Quantifying Efflux Pump Gene Expression using RT-PCR

- Objective: To compare efflux pump gene expression levels between planktonic and biofilm states.

- Methodology:

- RNA Isolation:

- Grow biofilms on a large surface area (e.g., in a biofilm reactor or on multiple plates). Harvest biofilm cells by scraping or sonication.

- In parallel, harvest planktonic cells from the same culture.

- Stabilize RNA immediately using a reagent like RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent.

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit with an on-column DNase I digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- cDNA Synthesis: Use a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit with random hexamers to synthesize first-strand cDNA from 500 ng to 1 µg of purified RNA.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- Design gene-specific primers for the target efflux pump (e.g.,

adeB,acrB,mexB) and for reference housekeeping genes (e.g.,rpoB,gyrB,16S rRNA). - Prepare a SYBR Green qPCR master mix according to manufacturer instructions and run the reactions in triplicate on a real-time PCR instrument.

- Use a standard thermal cycling protocol (e.g., 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min).

- Design gene-specific primers for the target efflux pump (e.g.,

- Data Analysis: Calculate the relative gene expression using the comparative 2^–ΔΔCq method. Normalize the Cq values of the target gene to the reference gene(s) and compare the biofilm samples to the planktonic control [16] [22]. An upregulation in biofilms suggests a functional role for the pump in this mode of growth.

- RNA Isolation:

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Efflux Pump Physiology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Isogenic Mutant Strains | To study the specific function of a single efflux pump gene by comparison to wild-type. | Comparing biofilm formation in ΔacrB vs. wild-type E. coli [21]. |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors (EPIs) | To chemically block pump activity and observe resultant phenotypic changes. | Using CCCP or PAβN to assess restoration of antibiotic susceptibility in biofilms [16]. |

| Fluorescent Substrates | To act as a tracer for direct measurement of efflux pump activity. | Using Ethidium Bromide in fluorometric assays to quantify real-time efflux [16]. |

| Gene Expression Assays | To quantify mRNA levels of efflux pump genes under different conditions. | SYBR Green-based RT-PCR to measure adeIJK expression in A. baumannii biofilms [16]. |

| Crystal Violet Stain | To quantify total biomass in static biofilm models. | Standard staining protocol for 96-well plate biofilm assays [21]. |

Visualizing Efflux Pump Regulation and Function

The following diagrams illustrate the regulatory pathways of efflux pumps and a standardized experimental workflow.

Efflux Pump Regulation and Physiological Impact

Diagram 1: Regulatory network of efflux pump expression and its physiological consequences. Environmental stressors activate regulatory systems, leading to efflux pump overexpression which directly influences key physiological traits like biofilm formation, virulence, and stress response [5] [14] [16].

Experimental Workflow for Functional Analysis

Diagram 2: A multi-faceted experimental workflow for analyzing efflux pump functions. The process begins with genetic manipulation, followed by parallel phenotypic, functional, and molecular analyses to comprehensively characterize pump roles [21] [16] [22].

The physiological functions of efflux pumps in virulence, biofilm formation, and stress response are fundamental to bacterial survival and pathogenesis. Viewing these transporters solely as antibiotic resistance elements provides an incomplete picture. Future research and therapeutic development should focus on these intrinsic roles, potentially leading to novel anti-virulence strategies and efflux pump inhibitors that disarm pathogens rather than directly killing them, thereby reducing selective pressure for resistance.

In the landscape of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), multidrug efflux pumps represent a primary defense mechanism for bacterial pathogens, contributing significantly to intrinsic and acquired resistance. Among Gram-negative bacteria, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa stand out due to their formidable ability to expel a wide range of antimicrobial agents. A. baumannii, particularly its carbapenem-resistant form (CRAB), is classified by the World Health Organization as a critical priority pathogen, while P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of life-threatening nosocomial infections [23] [24]. The core of this defensive capability lies in their Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family efflux pumps: the Ade pumps in A. baumannii and the Mex pumps in P. aeruginosa. These sophisticated transporter systems not only extrude antibiotics but are also intricately linked to fundamental bacterial physiology, including virulence, biofilm formation, and stress response [25] [26]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these efflux systems, detailing their operational mechanisms, regulatory networks, and methods for their experimental investigation, framed within the broader context of intrinsic resistance research.

Ade Pumps in Acinetobacter baumannii

Major Ade Pumps and Their Characteristics

Acinetobacter baumannii possesses several RND efflux pumps, among which three are clinically most significant: AdeABC, AdeIJK, and AdeFGH. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Major RND Efflux Pumps in Acinetobacter baumannii

| Efflux Pump | Genomic Context | Key Regulator | Primary Regulatory Mechanism | Common Antibiotic Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdeABC [26] | Core genome (some strains have AdeC) | AdeSR [26] | Two-component system (TCS) | Tetracyclines (e.g., Tigecycline), Aminoglycosides, Fluoroquinolones, Chloramphenicol [23] [26] |

| AdeIJK [26] | Core genome | Unknown (non-local) | Putative GntR-type regulator; AdeN suspected [26] | Broad spectrum of antibiotics, β-lactams [26] |

| AdeFGH [26] | Core genome | AdeL [26] | LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) | Fluoroquinolones, Chloramphenicol, Trimethoprim, Clindamycin [23] |

AdeABC is the most frequently overexpressed pump in multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolates. Its expression is controlled by the AdeSR two-component system, where AdeS is a histidine kinase and AdeR is a response regulator [26]. Upon sensing environmental signals (e.g., antibiotic presence), AdeS autophosphorylates and transfers the phosphate to AdeR. Phosphorylated AdeR then binds to the intercistronic region between adeR and adeA, activating transcription of the adeABC operon [26]. Mutations in adeS or adeR are a common mechanism for constitutive overexpression of this pump in clinical strains [26].

AdeIJK is considered the ancestral efflux pump of the Acinetobacter genus and is present in the core genome of all species. Its basal activity contributes to intrinsic resistance, and its overexpression leads to a broad MDR phenotype. In contrast, AdeFGH is the least studied, and its full clinical impact is still being elucidated [26].

Regulatory Pathways of Ade Pumps

The following diagram illustrates the complex transcriptional regulation of the key Ade efflux pumps in A. baumannii.

Diagram Title: Transcriptional Regulation of A. baumannii Ade Pumps

Mex Pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Major Mex Pumps and Their Roles

Pseudomonas aeruginosa's resistance is heavily mediated by four clinically relevant Mex efflux pumps of the RND family. These tripartite systems span the cell envelope and are composed of an inner membrane RND transporter (e.g., MexB), a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP, e.g., MexA), and an outer membrane factor (OMF, e.g., OprM) [27] [24]. Their individual profiles are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Major RND Efflux Pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Efflux Pump | Expression | Key Regulatory Gene(s) | Primary Antibiotic Substrates | Other Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MexAB-OprM [28] [27] [24] | Constitutive | nalC, nalB, naID [24] | β-lactams, Fluoroquinolones, Tetracycline, Chloramphenicol [28] [24] | Bile acid & fatty acid extrusion [24] |

| MexXY-OprM [28] [27] | Inducible | mexZ [27] | Aminoglycosides, Fluoroquinolones, Tetracycline, Erythromycin [28] [27] | Induced by ribosome-targeting antibiotics [27] |

| MexCD-OprJ [28] | Repressed in wild-type | nfxB [27] | Fluoroquinolones, Tetracycline, Chloramphenicol, Cephems [28] | - |

| MexEF-OprN [28] | Repressed in wild-type | nfxC [27] | Fluoroquinolones, Chloramphenicol, Trimethoprim [28] | - |

MexAB-OprM is constitutively expressed and provides a baseline level of intrinsic resistance to a wide range of antibiotic classes. In contrast, MexXY is noteworthy for its inducibility by ribosome-inhibiting antibiotics and its central role in aminoglycoside resistance, particularly in cystic fibrosis isolates [27]. MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN are typically silent in wild-type strains but can be derepressed through mutations, leading to increased resistance to their specific substrate profiles [28] [27].

Regulatory Network of Mex Pumps

The regulation of Mex pumps is multi-layered, involving local repressors and global regulators that respond to environmental stresses. The following diagram maps this complex regulatory network.

Diagram Title: Regulatory Network of P. aeruginosa Mex Pumps

Experimental Approaches for Efflux Pump Research

Workflow for Identifying Natural Substrates via Metabolomics

Understanding the full physiological role of efflux pumps requires identifying their natural substrates. A powerful approach for this is untargeted metabolomics, as exemplified by a recent study on P. aeruginosa [28]. The experimental workflow is outlined below.

Diagram Title: Metabolomic Workflow for Identifying Natural Substrates

Detailed Methodology:

- Strain Construction: Create a mutant strain (e.g., PA14Δ4mex) genetically deleted for the four major Mex efflux pumps (mexAB-oprM, mexCD-oprJ, mexXY-oprM, and mexEF-oprN) to serve as a background with minimal efflux activity [28].

- Genetic Complementation: Clone the operon of each efflux pump into an expression vector (e.g., pSRKGm) under the control of an inducible promoter (e.g., lac promoter). Introduce these constructs individually into the mutant strain to create a panel of isogenic strains, each overexpressing a single, specific efflux pump [28].

- Functional Validation: Verify the functionality of the overexpressed pumps by determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of known antibiotic substrates against each strain in the panel. A successful complementation should restore resistance levels to the substrates of the specific pump being expressed [28].

- Sample Preparation: Grow the wild-type, pump-deficient mutant, and individual pump-overexpressing strains under defined conditions. Collect culture supernatants at the desired growth phase and remove bacterial cells via filtration or centrifugation to obtain the "exo-metabolome" for analysis [28].

- LC-HRMS Analysis: Analyze the supernatant samples using Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) in an untargeted mode. This allows for the detection of a wide array of metabolic features [28].

- Data Analysis: Process the raw metabolomic data using specialized software for feature detection, alignment, and normalization. Statistically compare the abundance of each metabolic feature in the supernatant of each pump-overexpressing strain against the pump-deficient mutant. Features that are significantly more abundant when a specific pump is overexpressed are considered potential natural substrates for that pump [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Efflux Pump Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pSRKGm Expression Vector [28] | Inducible expression of efflux pump operons for genetic complementation and overexpression studies. | Used in P. aeruginosa for controlled EP expression from a lac promoter [28]. |

| LC-HRMS System [28] | Untargeted metabolomic analysis for identifying and characterizing natural substrates of efflux pumps. | Critical for detecting a wide range of metabolic features in culture supernatants [28]. |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors (EPIs) [15] [24] | Tool compounds to probe efflux pump function; potential leads for adjuvant therapy. | PAβN (Phenylarginyl-β-naphtylamide) is a widely used research EPI, though toxic for clinical use [24]. |

| Defined Mutant Libraries [28] [15] | Isogenic strains with single or multiple efflux pump gene deletions for functional genomics. | Essential for controlled experiments to assign specific functions to individual pumps. |

| RNA Sequencing (RNAseq) [28] | Transcriptomic profiling to analyze EP gene expression and regulatory networks. | Used to verify no compensatory overexpression of other EPs in multi-pump deletion mutants [28]. |

The Ade and Mex RND efflux pumps are fundamental components of the intrinsic resistome of A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Their ability to extrude diverse antimicrobials, coupled with complex regulatory networks that fine-tune their expression, makes them formidable adversaries. Research efforts are increasingly shifting towards understanding their natural physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms, as this knowledge is crucial for developing next-generation antimicrobial strategies. Promising approaches include the discovery of competitive efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) based on natural substrate structures [28], and the targeting of transcriptional regulators like AdeR to sensitize bacteria to existing antibiotics [26]. Overcoming the technical challenges associated with EPI development, such as achieving potency and avoiding eukaryotic toxicity, remains a key frontier. A deep and integrated understanding of efflux pump biology, from molecular structure to physiological function, is therefore indispensable for combating multidrug-resistant infections caused by these priority pathogens.

From Bench to Diagnostics: Advanced Techniques for Detecting and Quantifying Efflux Activity

Efflux pumps are a critical component of intrinsic antibiotic resistance in bacteria, significantly reducing the intracellular concentration of antimicrobial agents and contributing to the multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype [29] [30]. Phenotypic assays that measure the reduction of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in the presence of efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs), combined with fluorometric assays that directly quantify efflux activity, provide powerful tools for quantifying this resistance mechanism and screening for novel therapeutic adjuvants. This technical guide details the core methodologies and applications of these assays within intrinsic resistance research, providing a standardized framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Profiling of Efflux Pump Inhibitors via MIC Reduction Assays

The MIC reduction assay is a foundational phenotypic method for evaluating the efficacy of EPIs. It determines the fold increase in antibiotic susceptibility conferred by a candidate EPI, providing a direct measure of its potential to reverse efflux-mediated resistance.

Table 1: Representative EPI Efficacy from MIC Reduction Assays

| EPI Candidate | Bacterial Strain | Antibiotic Potentiated | MIC Reduction (Fold) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sertaconazole & Oxiconazole [29] | S. aureus (MSSA & MRSA) | Norfloxacin, Cefotaxime, Moxifloxacin | Significant reduction (specific values not provided) | Restored antibiotic efficacy; minimal cytotoxicity; effective in murine infection model. |

| KSA5_1 [31] | MDR A. baumannii | Ciprofloxacin | Up to 512-fold | Superior to PAβN; inhibits AdeG efflux pump gene expression. |

| Vitamin D & Vitamin K [30] | K. pneumoniae & P. aeruginosa | Ciprofloxacin | 64-fold | Powerful anti-efflux activity observed via EtBr accumulation. |

| Omeprazole (OME) [30] | K. pneumoniae & P. aeruginosa | - | - | Decreased expression of acrB and mexA efflux genes by 91.5% and 99.7%, respectively. |

| D13-9001 [32] | E. coli producing MexAB-OprM | Aztreonam, Ciprofloxacin, Erythromycin | Synergy observed (specific fold reduction not provided) | Specific inhibitor of MexAB-OprM; no activity against MexXY-OprM. |

| Chlorpromazine [33] | E. coli | Trimethoprim | Synergy observed | Efflux pump inhibitor used in resistance-proofing studies. |

Experimental Protocol: Broth Microdilution for MIC Reduction

Principle: This method assesses the ability of an EPI to lower the MIC of a co-administered antibiotic by inhibiting active efflux, thereby increasing intracellular antibiotic accumulation [29] [30] [31].

Materials:

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB)

- Sterile 96-well microtiter plates

- Logarithmic-phase bacterial suspension (e.g., adjusted to 1 × 10⁶ CFU/mL)

- Antibiotic stock solutions (e.g., norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin)

- EPI stock solution (e.g., sertaconazole, KSA5_1)

Method:

- Preparation: Dispense CAMHB into the wells of the microtiter plate.

- Antibiotic Dilution: Perform two-fold serial dilutions of the antibiotic in the growth medium along the rows of the plate.

- EPI Addition: Add the candidate EPI at a sub-inhibitory concentration (e.g., 0.25× or 0.5× its predetermined MIC) to all test wells [30]. A control without the EPI must be included.

- Inoculation: Inoculate all wells with the standardized bacterial suspension. Include growth control and sterility control wells.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 16–20 hours.

- Analysis: Determine the MIC of the antibiotic in the presence and absence of the EPI. The MIC is the lowest concentration that completely inhibits visible growth. The fold reduction is calculated as: MIC(antibiotic alone) / MIC(antibiotic + EPI).

Validation: A significant reduction (typically ≥4-fold) in the MIC of the antibiotic in the presence of the EPI is indicative of efflux pump inhibition [29] [31].

Direct Measurement of Efflux Activity via Fluorometric Assays

Fluorometric assays provide direct, real-time functional data on efflux pump activity by tracking the accumulation or extrusion of fluorescent substrate dyes in the presence of EPIs.

Table 2: Key Fluorometric Assays for Efflux Activity

| Assay Type | Fluorogenic Substrate | Key Readout | Application & Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) Accumulation Assay [29] [30] | Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) | Increase in fluorescence intensity indicates EPI-mediated efflux inhibition. | Standard method; real-time kinetic measurement; adaptable to high-throughput. |

| FDG-Based Microfluidic Assay [32] | Fluorescein-di-β-d-galactopyranoside (FDG) | Intracellular fluorescence after hydrolysis indicates reduced efflux. | Highly sensitive; allows single-cell analysis; visualizes real-time efflux inhibition. |

| MALDI-TOF MS Efflux Monitoring [34] | EtBr, Hoechst 33342, Nile Red, drugs | Direct measurement of substrate abundance in extracellular medium over time. | Label-free; avoids fluorescence quenching issues; monitors multiple substrates. |

Experimental Protocol: Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) Accumulation Assay

Principle: EtBr is a substrate for many efflux pumps. Its fluorescence is quenched in aqueous environments and strongly enhances upon binding to intracellular DNA. Inhibition of efflux pumps leads to increased intracellular accumulation of EtBr and a corresponding increase in fluorescence [29] [30].

Materials:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Bacterial cells in mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 ~ 0.6)

- Ethidium Bromide stock solution (1 mg/mL)

- Candidate EPI (e.g., sertaconazole, oxiconazole)

- Glucose solution (for energy-dependent efflux)

- 96-well black-walled microplate

- Multi-mode plate reader with fluorescence capabilities (excitation ~530 nm, emission ~590 nm)

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation and resuspend in PBS to an OD600 of ~0.3.

- Plate Setup: Dispense the cell suspension into the wells of a black microplate.

- Treatment: Add EtBr (e.g., 1 µg/mL) to all experimental wells. Add the candidate EPI (e.g., 10 µM) to the test wells. Include controls:

- Negative Control: Cells + EtBr + Glucose (0.4% to energize efflux)

- Positive Control: Cells + EtBr + known EPI (e.g., Thioridazine at 16 µg/mL)

- Test: Cells + EtBr + candidate EPI

- Measurement: Immediately transfer the plate to a pre-warmed (37°C) plate reader. Shake the plate continuously and measure the fluorescence intensity every 5 minutes for 60 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity versus time. A steeper slope and higher final fluorescence in the test well compared to the negative control indicate successful inhibition of efflux activity [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Efflux Assays

| Reagent | Function in Assay | Example Usage & Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) [29] [34] [30] | Fluorescent efflux pump substrate. | Used in accumulation/efflux assays; fluorescence increases upon DNA binding. |

| Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenyl Hydrazone (CCCP) [34] [30] | Protonophore that dissipates proton motive force (PMF). | Positive control for EPI; inhibits PMF-driven secondary transporters. |

| Phenylarginine-β-Naphthylamide (PAβN) [34] [32] [31] | Broad-spectrum EPI for RND pumps. | Commonly used positive control for Gram-negative bacteria; can have membrane permeabilizing effects. |

| Fluorescein-di-β-d-galactopyranoside (FDG) [32] | Fluorogenic substrate hydrolyzed intracellularly to fluorescent fluorescein. | Used in specialized microfluidic assays; both FDG and fluorescein are efflux substrates. |

| Sertraline [35] | Clinically used antidepressant identified as an EPI. | Prevents formation of phenotypically resistant subpopulations to AMPs in stationary phase cells. |

Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms of Efflux Inhibition

A key mechanism of efflux pump inhibition involves disruption of the energy source required for pump activity. Secondary active transporters, such as those in the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) and Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family, utilize the proton motive force (PMF) [29].

Diagram Title: EPI Inhibition of PMF-Dependent Efflux

Studies on EPIs like sertaconazole and oxiconazole demonstrate that they alter the PMF, diminishing the membrane potential (ΔΨ) while increasing the ΔpH component, thereby robbing the efflux pumps of their energy source and ultimately inhibiting ATP production [29].

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Novel Analytical and Single-Cell Approaches

MALDI-TOF MS for Efflux Monitoring: This label-free method directly measures the efflux of substrates by tracking their abundance in the extracellular medium over time using mass spectrometry. It avoids potential issues associated with fluorescent dyes, such as signal quenching, and can monitor multiple substrates simultaneously [34].

Microfluidic Single-Cell Analysis: Microfluidic devices, combined with fluorogenic substrates like FDG, enable the observation of efflux inhibition in real-time at the single-cell level. This high-sensitivity approach can reveal heterogeneous efflux pump expression and activity within a clonal population, which is crucial for understanding phenotypic resistance [32] [35].

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Profiling

Diagram Title: Workflow for EPI Profiling

The path to a successful EPI involves multiple, complementary assays. The workflow typically begins with basic phenotypic screening (MIC reduction) and functional analysis (fluorometric assays), progressing to molecular confirmation of EP gene expression, and finally, advanced profiling using techniques like microfluidics and metabolomics [29] [30] [28]. This multi-faceted approach is essential for deciphering the role of efflux pumps in intrinsic resistance and for developing effective therapeutic strategies to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a critical threat to global public health, with projections of 10 million annual deaths by 2050 if left unaddressed [36]. Among the various mechanisms bacteria employ to resist antibiotics, multidrug efflux pumps constitute a formidable first line of defense through intrinsic resistance [37]. These membrane-associated transporters actively extrude diverse toxic compounds, including multiple classes of antibiotics, from the bacterial cell before they reach their intracellular targets [38]. The resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family of efflux pumps, exemplified by AcrAB-TolC in Escherichia coli and Enterobacteriaceae and MexAB-OprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are particularly noteworthy for their exceptionally broad substrate specificity and clinical significance [39] [40].