Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms, Key Bacterial Pathogens, and Research Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bacterial species possessing intrinsic (natural) antibiotic resistance, a critical challenge in antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms, Key Bacterial Pathogens, and Research Strategies

Abstract

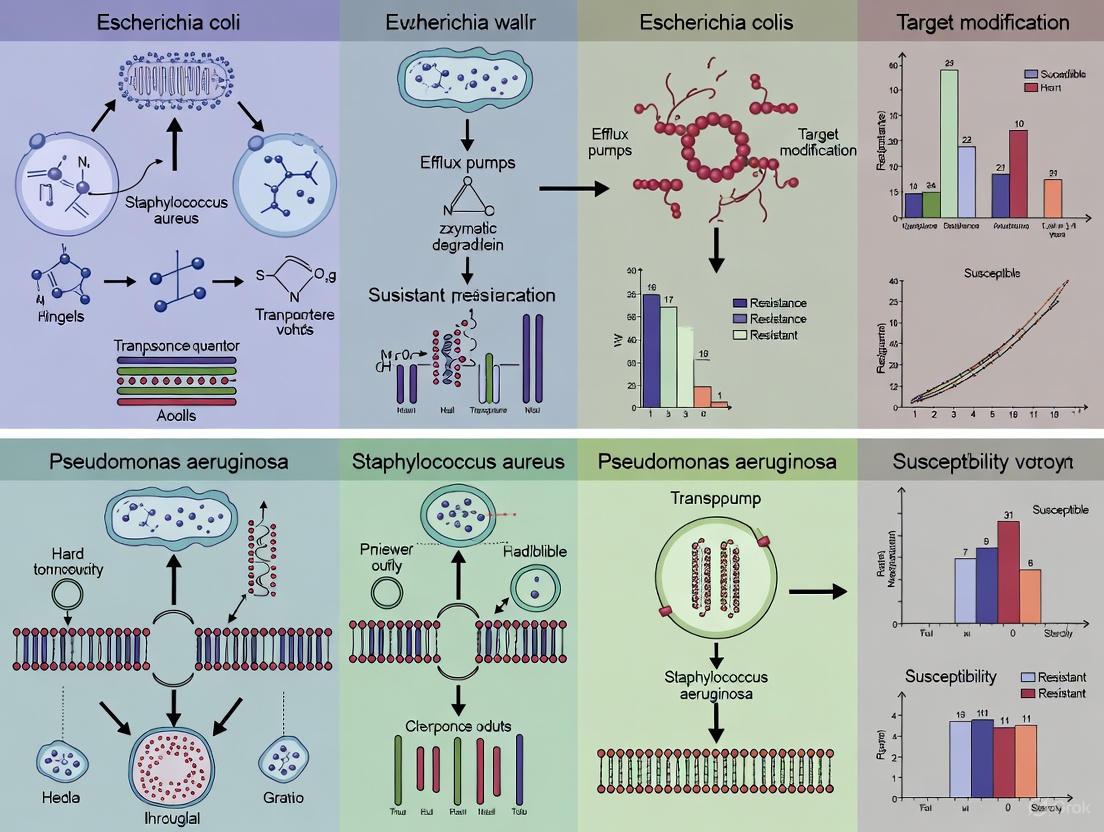

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bacterial species possessing intrinsic (natural) antibiotic resistance, a critical challenge in antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of innate resistance, details high-priority pathogens from the WHO 2024 list, and examines advanced methodological approaches for studying these bacteria. The content further addresses troubleshooting for R&D hurdles, validates surveillance and comparative analysis frameworks, and synthesizes key strategies to guide the development of novel therapeutics against inherently resistant infections.

The Innate Shield: Unraveling the Core Mechanisms of Natural Antibiotic Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global health crises of the 21st century, threatening to undermine the foundations of modern medicine [1]. In 2019 alone, bacterial infections accounted for 13.6% of all global deaths, with more than 7.7 million fatalities directly attributable to 33 bacterial pathogens [1]. Projections indicate that by 2050, AMR could be responsible for over 10 million deaths annually unless effective countermeasures are developed [1] [2].

Within this crisis, understanding the fundamental distinction between intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance is paramount for directing drug discovery efforts. Intrinsic resistance refers to innate capabilities of a bacterial species to withstand antibiotic action, while acquired resistance emerges through genetic changes in previously susceptible strains [3] [4]. This distinction is not merely academic; it shapes diagnostic approaches, therapeutic decisions, and research priorities. For drug development professionals, targeting the immutable mechanisms of intrinsic resistance requires different strategies than countering the adaptable nature of acquired resistance. This whitepaper delineates these critical resistance categories, their molecular foundations, and their implications for developing next-generation antimicrobial therapies.

Defining the Fundamental Resistance Paradigms

Intrinsic Resistance: The Innate Bacterial Armor

Intrinsic resistance, also termed innate or natural resistance, is chromosomally encoded and universally present across all strains of a bacterial species [3]. It is a hereditary trait independent of horizontal gene transfer or previous antibiotic exposure [5] [3]. This form of resistance delineates the natural spectrum of activity for an antibiotic class and is consequently predictable for given bacterial species [3].

Table 1: Mechanisms and Examples of Intrinsic Resistance

| Mechanism | Description | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Permeability | Structural barriers prevent antibiotic entry into the cell | Gram-negative outer membrane confers resistance to glycopeptides (e.g., vancomycin) [3] [4] |

| Efflux Pumps | Constitutively expressed pumps export antibiotics | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MexAB-OprM system exports multiple drug classes [3] |

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Chromosomally encoded enzymes degrade or modify antibiotics | P. aeruginosa AmpC β-lactamase hydrolyzes cephalosporins [3] |

| Target Modification | Native antibiotic targets exhibit low drug affinity | Enterococci low-affinity PBP5 confers cephalosporin resistance [3] |

| Absence of Target | Bacteria lack the structure or pathway targeted by the antibiotic | Mycoplasmas lack cell walls, making them resistant to β-lactams [3] |

Acquired Resistance: The Adaptable Bacterial Response

Acquired resistance emerges in previously susceptible bacterial strains through genetic changes that confer the ability to survive antibiotic exposure [6]. This form of resistance is unpredictable, strain-specific, and results from two primary processes: mutations in chromosomal genes or acquisition of foreign genetic material through horizontal gene transfer [5] [6].

Table 2: Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance

| Mechanism | Genetic Basis | Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Acquisition of plasmid-encoded genes | β-lactamase (ESBL) production in E. coli [1] [4] |

| Target Modification | Mutations in chromosomal genes | MRSA via mecA gene encoding alternative PBP2a [1] [4] |

| Enhanced Efflux | Mutation in regulatory genes | Overexpression of efflux pumps in K. pneumoniae [1] |

| Target Bypass | Acquisition of alternative metabolic pathways | Vancomycin-resistant enterococci produce D-Ala-D-Lac instead of D-Ala-D-Ala [4] |

| Reduced Permeability | Mutations in porin genes | Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacterales via porin loss [1] |

Methodologies for Investigating Resistance Mechanisms

Experimental Workflow for Differentiating Resistance Types

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Identifying Intrinsic Resistance Mechanisms

Objective: Systematically characterize the molecular basis of intrinsic antibiotic resistance in a bacterial species.

Methodology:

- Comparative Genomic Analysis:

- Perform whole-genome sequencing of multiple type strains using Illumina NovaSeq and Oxford Nanopore platforms

- Identify conserved chromosomal genes encoding resistance determinants through pan-genome analysis

- Annotate putative efflux pump regulators, permeability barriers, and innate enzymatic systems

Membrane Permeability Assessment:

- Utilize nitrocefin diffusion assays to quantify outer membrane permeability

- Employ ethidium bromide accumulation assays with and without efflux pump inhibitors

- Conduct proteomic analysis of membrane fractions via LC-MS/MS to characterize porin profiles

Target Site Characterization:

- Express and purify putative target proteins (e.g., PBPs, DNA gyrase)

- Determine antibiotic binding affinity using surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

- Compare target gene sequences across related susceptible and resistant species

Validation: Create targeted knockout mutants of identified resistance genes using CRISPR-Cas9 systems and confirm hypersusceptibility phenotype through broth microdilution MIC testing [3].

Protocol for Tracking Acquisition of Resistance

Objective: Elucidate genetic mechanisms underlying acquired resistance in clinical isolates.

Methodology:

- Horizontal Gene Transfer Detection:

- Perform plasmid conjugation assays with resistant donor and susceptible recipient strains

- Conduct natural transformation experiments with genomic DNA from resistant strains

- Use PCR-based replicon typing to classify resistance plasmids

Mutation Analysis:

- Sequence candidate resistance genes from pre- and post-treatment isolates

- Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) through variant calling pipelines

- Correlate mutation patterns with resistance phenotype trajectories

Expression Profiling:

- Quantify mRNA expression of efflux pumps and resistance enzymes via RT-qPCR

- Assess regulatory gene mutations through promoter sequence analysis

- Profile global gene expression changes using RNA-seq under antibiotic stress

Validation: Conduct complementation experiments by introducing wild-type genes into mutant backgrounds and assess restoration of susceptibility [5] [6].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Resistance Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Application | Key Function in Resistance Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene knockout/editing | Functional validation of resistance genes through targeted mutagenesis [3] |

| Broth Microdilution Panels | MIC determination | Gold standard quantification of resistance levels according to CLSI/EUCAST guidelines |

| Long-read Sequencers (Nanopore) | Whole genome assembly | Resolution of mobile genetic elements and complex resistance loci [1] |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | Mechanism elucidation | Differentiation between efflux-mediated and other resistance mechanisms |

| β-lactamase Substrates | Enzyme detection | Characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases [4] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Binding affinity studies | Quantification of drug-target interactions in intrinsic resistance [3] |

| Conjugation Assay Systems | HGT monitoring | Tracking plasmid-mediated dissemination of resistance genes [5] |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

The strategic distinction between intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms directly informs multiple facets of antibiotic drug development. For pathogens exhibiting primarily intrinsic resistance, such as P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, effective therapeutic approaches must circumvent constitutive barriers like impermeable membranes and multidrug efflux systems [3]. This might involve designing smaller compounds that exploit rare porins, developing efflux pump inhibitors as combination therapies, or creating novel agents that bypass the need to cross certain membrane barriers entirely.

In contrast, combating acquired resistance requires strategies focused on preventing resistance emergence and spread. This includes developing compounds with multiple targets within the same pathogen, creating drugs less susceptible to common enzymatic inactivation mechanisms, and employing stewardship approaches that limit selective pressure [6]. The WHO's critical priority pathogens list, dominated by Gram-negative bacteria with both intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms, highlights the clinical urgency of these targeted approaches [1] [7].

Emerging therapeutic avenues include novel antibiotic classes such as lasso peptides and macrocyclic peptides (e.g., zosurabalpin), naturally derived compounds (e.g., corallopyronin, clovibactin), and targeted inhibitors that circumvent existing resistance mechanisms [1]. Additionally, non-antibiotic approaches including bacteriophage therapy, monoclonal antibodies, and virulence factor inhibitors offer promise for overcoming both intrinsic and acquired resistance by targeting bacterial pathogens through alternative mechanisms [8].

The critical distinction between intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance provides an essential conceptual framework for directing antimicrobial drug development. Intrinsic resistance, being inherent and predictable, demands pathogen-specific strategies that circumvent constitutive protection mechanisms. Acquired resistance, characterized by its genetic plasticity and transferability, necessitates approaches that forestall evolutionary adaptation and horizontal dissemination. As resistance continues to escalate globally—with current reports indicating that one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections worldwide are now resistant to antibiotic treatments—the strategic allocation of research resources guided by this fundamental distinction becomes increasingly imperative [7]. Future progress against the AMR crisis will depend on integrating this understanding with innovative chemical entities, novel therapeutic modalities, and improved diagnostic precision to preserve the efficacy of antimicrobial therapies for future generations.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical threat to global health, with intrinsic resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria presenting particularly formidable challenges. This whitepaper examines the sophisticated cellular fortifications conferred by reduced membrane permeability and active efflux pumps, which function synergistically to limit intracellular antibiotic accumulation. Within the context of bacterial species exhibiting natural antibiotic resistance, we delineate the molecular architecture and operational mechanisms of these barrier systems, present quantitative assessments of their contributions to resistance profiles, and detail experimental methodologies for their investigation. The interplay between these systems not only defines current treatment limitations but also illuminates pathways for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at circumventing resistance in multidrug-resistant pathogens.

The outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria constitutes a highly selective permeability barrier that, in synergy with active efflux systems, confers intrinsic resistance to a broad spectrum of antimicrobial agents [9]. This asymmetric bilayer, composed of phospholipids in the inner leaflet and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the outer leaflet, provides protection without compromising essential exchange functions [9]. The OM's effectiveness as a barrier stems from its unique structural organization. The LPS molecules, particularly their lipid A components, feature six saturated fatty acid chains (compared to two in typical phospholipids), creating a densely packed, hydrophobic membrane with low fluidity [9]. Strong lateral interactions between LPS molecules, stabilized by divalent cations that bridge anionic groups, further reduce permeability to hydrophobic compounds [9].

Simultaneously, bacteria employ active efflux pumps—proteinaceous transporters that expel toxic substances, including antibiotics, from the cell [10]. These energy-dependent systems recognize substrates based on physicochemical properties rather than defined chemical structures, enabling them to handle remarkably diverse compounds [11]. The combination of these passive and active barrier mechanisms creates a robust defense system that this review will explore in detail, focusing on molecular mechanisms, experimental approaches, and therapeutic implications for drug development professionals.

Molecular Architecture of the Outer Membrane

Lipopolysaccharide Structure and Barrier Function

The structural complexity of LPS is fundamental to the OM's barrier properties. A typical LPS molecule consists of three domains: lipid A, a core oligosaccharide, and the O-antigen polysaccharide [9]. Lipid A, a glucosamine-based phospholipid, forms the membrane-anchoring segment, while the O-antigen extends externally, contributing to serum resistance and immune evasion. Mutants with truncated LPS cores ("deep rough" mutants) exhibit dramatically increased sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics, detergents, and bile salts, underscoring the importance of an intact LPS structure for barrier function [9]. The barrier effectiveness is further modulated by LPS modifications, such as the addition of 4-aminoarabinose or phosphoethanolamine to lipid A phosphates in polymyxin-resistant strains. These substitutions reduce the net negative charge of LPS, potentially enabling closer packing of LPS molecules and decreasing binding of cationic antimicrobial peptides [9].

Porin-Mediated Permeation Pathways

Hydrophilic antibiotics, including β-lactams and fluoroquinolones, primarily traverse the OM through porin channels—β-barrel proteins that form aqueous diffusion pores [9]. General diffusion porins, such as OmpF and OmpC in Escherichia coli, permit the passive passage of small hydrophilic molecules based on size, charge, and hydrophobicity. The molecular basis for porin selectivity involves constriction zones lined with acidic and basic residues that create an electric field, influencing the passage of charged molecules [9]. Modifications to porin expression, sequence, or structure represent common resistance strategies. For instance, clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae frequently show alterations in ompK35 and ompK36 porin genes, contributing to resistance against β-lactams and other hydrophilic antibiotics [12]. Similarly, Pseudomonas aeruginosa can downregulate its major porin OprF to reduce antibiotic uptake [9].

Table 1: Primary Antibiotic Permeation Pathways Across the Gram-Negative Outer Membrane

| Permeation Pathway | Antibiotic Classes | Molecular Determinants | Resistance Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-mediated diffusion | Aminoglycosides, Macrolides, Rifamycins, Novobiocin, Fusidic acid | LPS core structure, Hydrophobicity, Cationic bridges | LPS modifications (e.g., 4-aminoarabinose addition), Increased LPS packing density |

| Porin-mediated diffusion | β-Lactams, Fluoroquinolones, Tetracyclines, Chloramphenicol | Porin expression (OmpF, OmpC, OprF), Size exclusion limit, Charge selectivity | Porin downregulation, Porin mutations altering channel properties, Loss-of-function mutations |

| Self-promoted uptake | Polymyxins, Cationic antimicrobial peptides | Lipid A charge, LPS packing density | Lipid A modifications reducing negative charge, Addition of phosphoethanolamine |

Active Efflux Systems: Architecture and Function

Classification and Energy Coupling

Bacterial efflux pumps are categorized into five major superfamilies based on amino acid sequence, energy coupling mechanism, and structural organization [10] [11]. An understanding of their distinct properties is essential for designing inhibition strategies.

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily: These primary active transporters utilize ATP hydrolysis to drive substrate translocation across the membrane. ABC transporters typically consist of two transmembrane domains (TMDs) that form the translocation pathway and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) that hydrolyze ATP [10]. They function via an 'alternate access' mechanism, switching between inward-facing and outward-facing conformations [10].

Resistance-nodulation-division (RND) superfamily: Particularly important in Gram-negative bacteria, RND pumps are secondary active transporters that utilize the proton motive force (pmf) for energy. They form sophisticated tripartite complexes spanning the entire cell envelope, consisting of an inner membrane RND transporter (e.g., AcrB), a periplasmic adapter protein (e.g., AcrA), and an outer membrane factor (e.g., TolC) [10] [11].

Major facilitator superfamily (MFS): The largest superfamily of secondary active transporters, MFS pumps utilize proton gradients to extrude substrates and primarily handle single classes of antimicrobials in bacterial pathogens [10].

Multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family: These secondary transporters use either proton or sodium ion gradients to export diverse drugs [10].

Small multidrug resistance (SMR) family: Compact secondary transporters with four transmembrane segments that form homotrimers to create a functional efflux channel [11].

Table 2: Major Bacterial Efflux Pump Superfamilies and Their Properties

| Superfamily | Energy Source | Typical Architecture | Representative Systems | Substrate Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC | ATP hydrolysis | 2 TMDs + 2 NBDs | MacAB (multiple species) | Macrolides, peptides, LPS |

| RND | Proton motive force | 12 TMDs; tripartite complex | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli), MexAB-OprM (P. aeruginosa) | Extremely broad: β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, dyes, detergents |

| MFS | Proton motive force | 12 or 14 TMDs | MdfA (E. coli), NorA (S. aureus) | Fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol |

| MATE | Proton/sodium motive force | 12 TMDs | NorM (V. cholerae), PmpM (P. aeruginosa) | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, dyes |

| SMR | Proton motive force | 4 TMDs (homotrimer) | EmrE (E. coli), QacC (S. aureus) | Disinfectants, dyes, some β-lactams |

RND Pumps: The Gram-Nigh Tripartite Assemblies

The RND-type efflux pumps represent the most clinically significant efflux systems in Gram-negative pathogens due to their extraordinarily broad substrate specificity [10]. The AcrAB-TolC system of E. coli serves as a paradigm for understanding these complex molecular machines. The inner membrane component AcrB (an RND transporter) acts as the substrate recognition and energy transduction module, undergoing conformational changes that facilitate drug transport [11]. The periplasmic adapter protein AcrA forms a bridge between AcrB and the outer membrane channel TolC, creating a continuous conduit from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space [10]. Structural studies have revealed that AcrB functions as a trimer, with each monomer cycling through consecutive loose, tight, and open states in a coordinated rotational mechanism that extrudes substrates [11].

Beyond antibiotic resistance, RND pumps serve fundamental physiological functions. The AcrAB-TolC system in E. coli pumps out bile acids and fatty acids, providing protection in hostile environments like the intestinal tract [11]. In pathogens like Erwinia amylovora, AcrAB homologs contribute to virulence, host colonization, and resistance to plant toxins [11]. The multifunctionality of these systems complicates therapeutic targeting, as complete inhibition may adversely affect bacterial viability or virulence in ways that could potentially be exploited.

Synergistic Barrier Function: Permeability and Efflux

The intrinsic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria emerges not merely from the independent action of the OM barrier and efflux systems, but from their powerful synergy [13]. This cooperative relationship fundamentally defines the resistance profiles of significant pathogens including Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Burkholderia species [13]. The OM restricts the initial influx of antibiotics, thereby reducing the intracellular concentration that efflux pumps must manage. Simultaneously, efflux systems actively extrude compounds that penetrate the OM, preventing their accumulation to effective levels [13].

This synergy universally protects bacteria from structurally diverse antibiotics, with the OM and efflux pumps selecting compounds based on distinct physicochemical properties [13]. Research indicates that antibiotics can be categorized into specific clusters based on their interactions with these permeability barriers, with each cluster following intrinsic rules of intracellular penetration [13]. For instance, hydrophobic antibiotics that traverse the lipid bilayer are vulnerable to efflux, while hydrophilic antibiotics relying on porins for entry face both reduced influx through porin downregulation and active extrusion.

Diagram 1: Synergy between membrane barriers and efflux. The outer membrane limits initial antibiotic influx, while efflux pumps actively remove compounds that penetrate this barrier, creating a cooperative defense system.

Quantitative analyses reveal that the relative contribution of each component varies significantly across bacterial species. In P. aeruginosa, the exceptionally low permeability of its OM (approximately 100-fold lower than E. coli) combines with potent RND efflux systems to create an extraordinarily robust barrier system [13]. This interspecies variation in permeability barriers explains the differential antibiotic susceptibility patterns observed clinically and highlights the need for pathogen-specific therapeutic approaches.

Quantitative Assessment of Resistance Contributions

The individual and combined contributions of the OM barrier and efflux pumps to antibiotic resistance can be quantified through carefully designed experiments. Comparative studies measuring antibiotic accumulation in wild-type strains versus isogenic mutants with hyperporinated membranes or deleted efflux pump genes have been instrumental in decoupling these effects [13].

Table 3: Quantitative Contributions of Barrier Mechanisms to Antibiotic Resistance

| Bacterial Species | Antibiotic | OM Contribution (Fold Resistance) | Efflux Contribution (Fold Resistance) | Synergistic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Ciprofloxacin | 2-4x | 4-8x | 8-32x (combined) |

| P. aeruginosa | Levofloxacin | 16-32x | 8-16x | 128-512x (combined) |

| A. baumannii | Carbapenems | 8-16x | 2-4x | 16-64x (combined) |

| K. pneumoniae | β-lactams | 4-8x (porin loss) | 4-8x (AcrAB) | 16-64x (combined) |

Recent clinical data from K. pneumoniae isolates demonstrate the real-world impact of these mechanisms. Among clinical isolates, the prevalence of the AcrAB efflux system reached 94.54%, while the porin genes ompK35 and ompK36 were present in 96.36% and 98.18% of strains, respectively [12]. Strains simultaneously possessing efflux and porin modifications were significantly associated with extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pandrug-resistant (PDR) phenotypes, highlighting the clinical consequences of combined barrier mechanisms [12].

The quantitative understanding of these resistance contributions is increasingly leveraged through systems biology approaches that integrate multiscale data to predict AMR evolution. These models incorporate factors such as mutation rates, fitness costs, and selection pressures to forecast resistance trajectories [14]. The predictability of resistance evolution varies across temporal, biological, and complexity scales, with short-term microevolution exhibiting greater predictability than long-term macroevolution [14].

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis

Assessing Outer Membrane Permeability

Lipid Bilayer Permeability Assay: This method evaluates the diffusion rates of antimicrobial compounds across model membrane systems. Synthetic liposomes incorporating purified LPS or specific phospholipid compositions are created to mimic the native OM environment [9]. A gradient of the test antibiotic is established across the liposome membrane, and uptake is quantified over time using techniques such as fluorescence spectroscopy (for intrinsically fluorescent or labeled antibiotics) or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for direct quantification [9]. This approach allows systematic examination of how specific LPS modifications (e.g., core oligosaccharide truncations, lipid A alterations) influence permeability independent of cellular context.

Porin Permeability Profiling: The role of specific porins in antibiotic uptake can be delineated through multiple approaches. Genetic methods involve creating isogenic strains with deleted or modified porin genes and comparing antibiotic susceptibility profiles and accumulation rates [12]. Electrophysiological approaches incorporate purified porins into planar lipid bilayers and measure ionic currents in the presence of antibiotics, providing information on translocation rates and channel selectivity [9]. Molecular exclusion assays using reconstituted porins in proteoliposomes can directly quantify the diffusion of radiolabeled or fluorescent antibiotics through specific porin channels [9].

Efflux Pump Functional Analysis

Efflux Inhibition Assays: The contribution of active efflux to antibiotic resistance can be quantified using efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) such as phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide (PAβN) for RND pumps or verapamil for MFS pumps [10] [11]. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) reduction assays compare antibiotic susceptibility in the presence and absence of subinhibitory concentrations of EPIs. A significant reduction (typically ≥4-fold) in MIC with EPI treatment indicates substantial efflux contribution [10]. Ethidium bromide accumulation assays directly measure efflux activity using fluorescent substrates, where increased intracellular fluorescence in the presence of EPIs or in efflux-deficient mutants demonstrates functional efflux [10].

Real-time Efflux Kinetics: Advanced methodologies enable direct quantification of antibiotic efflux kinetics. Intracellular antibiotic concentrations can be monitored in real-time using LC-MS/MS sampling from bacterial suspensions, providing direct measurement of accumulation and efflux rates [13]. Fluorescent antibiotic derivatives or probes enable continuous monitoring of efflux kinetics through fluorescence spectroscopy or flow cytometry, allowing high-throughput screening of efflux activity across multiple conditions [10].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for analyzing resistance mechanisms. The integrated approach combines phenotypic screening with genetic and functional characterization to delineate the contributions of specific resistance components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Membrane Permeability and Efflux Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | PAβN, CCCP, Verapamil, Reserpine | Functional efflux characterization | Distinguishes efflux-mediated resistance; identifies pump substrates |

| Membrane Permeabilizers | Polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), EDTA, Tris | Barrier function assessment | Evaluates OM integrity; distinguishes intracellular vs. extracellular targets |

| Genetic Tools | Knockout strains (ΔacrB, ΔtolC), Plasmid complementation, Reporter fusions | Mechanism dissection | Isolates contribution of specific genes; studies regulation |

| Chemical Probes | Ethidium bromide, Hoechst 33342, N-phenylnaphthylamine | Membrane integrity and fluidity | Measures passive diffusion; monitors membrane organization |

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-OmpA, Anti-LPS core, Anti-AcrA | Protein localization and expression | Quantifies membrane component abundance; visualizes spatial distribution |

| Analytical Standards | (^{14})C-labeled antibiotics, Fluorescent antibiotic derivatives | Uptake and efflux kinetics | Enables precise quantification of antibiotic accumulation |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The sophisticated understanding of cellular fortifications provided by reduced membrane permeability and efflux pumps informs several promising therapeutic strategies. Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) represent a logical approach to counteract efflux-mediated resistance, with the goal of rejuvenating existing antibiotics [10]. Despite significant research investment, no EPI has yet achieved clinical approval, reflecting the challenges of achieving potent inhibition without host toxicity and the redundancy of efflux systems [10]. Innovative approaches include the exploration of natural product inhibitors such as carotenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids, which may provide novel chemical scaffolds with improved therapeutic indices [11]. Additionally, nanoparticles, particularly zinc oxide, have shown promise as efflux inhibitors, potentially through simultaneous disruption of multiple resistance mechanisms [11].

An alternative strategy involves designing antibiotics that bypass conventional permeability barriers. This includes developing compounds that exploit native uptake systems, such as siderophore-antibiotic conjugates that "hijack" iron acquisition pathways [9]. Another approach focuses on creating molecules with optimized physicochemical properties that evade efflux recognition, potentially through machine learning analysis of pump substrate preferences [10]. The emerging understanding of antibiotic clustering based on permeation rules provides a framework for such rational design approaches [13].

The growing appreciation for the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of resistance development highlights additional intervention points. Within-patient AMR emergence occurs through multiple mechanisms: spontaneous resistance mutations, in situ horizontal gene transfer, selection of pre-existing resistance, and immigration of resistant lineages [15]. The relative importance of each mechanism varies across bacterial species and infection sites, suggesting that personalized approaches considering both pathogen and infection context may be necessary [15]. Quantitative systems-based modeling of resistance evolution, incorporating multiscale data from microbial evolution experiments, offers promise for predicting resistance trajectories and informing antibiotic stewardship paradigms [14].

The cellular fortifications comprising the Gram-negative outer membrane permeability barrier and active efflux systems represent sophisticated defense mechanisms that collectively determine intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Their synergistic action creates a formidable barrier that limits the efficacy of existing antibiotics and complicates the development of new therapeutic agents. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular architecture, functional coordination, and evolutionary dynamics of these systems provides essential insights for overcoming bacterial resistance. Future advances will require integrated approaches combining structural biology, chemical biology, and systems-based modeling to develop innovative strategies that circumvent or neutralize these ancient bacterial defense systems. The application of this knowledge to therapeutic design, coupled with prudent antimicrobial stewardship, offers the best hope for addressing the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global public health threats, with drug-resistant infections causing approximately 1.27 million deaths worldwide annually [16]. Among the diverse strategies employed by bacterial pathogens, structural evasion through innate drug target modifications and enzymatic inactivation of antibiotics constitutes a primary defense mechanism that significantly compromises therapeutic efficacy. These resistance mechanisms are particularly concerning in Gram-negative bacteria, which possess a complex cell envelope that acts as an additional permeability barrier, working in concert with enzymatic and target-based resistance strategies [17].

The relentless evolutionary arms race between bacteria and antimicrobial compounds has selected for sophisticated resistance mechanisms that are often encoded on mobile genetic elements, enabling rapid dissemination among bacterial populations [18] [19]. Structural evasion strategies encompass two fundamental approaches: (1) the physical alteration or protection of antimicrobial targets within the bacterial cell, and (2) the enzymatic destruction or chemical modification of antibiotic molecules before they reach their cellular targets. Understanding these mechanisms at molecular and structural levels is crucial for developing novel therapeutic approaches to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens, particularly within the framework of bacterial species exhibiting natural antibiotic resistance [20] [17].

Molecular Mechanisms of Enzymatic Inactivation

β-Lactamases: Diversity and Classification

β-lactamases represent the most prevalent and diverse family of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, capable of hydrolyzing the β-lactam ring essential to the antibacterial activity of penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams [21] [17]. These enzymes are classified into four molecular classes (A, B, C, and D) based on their amino acid sequences and catalytic mechanisms. Classes A, C, and D are serine hydrolases that utilize an active-site serine residue to catalyze hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring, while class B enzymes are zinc-dependent metallo-β-lactamases that employ metal ions for catalysis [21].

The Ambler classification system categorizes β-lactamases according to their molecular structure and mechanism:

- Class A (Serine-based): Includes TEM, SHV, and CTX-M enzymes, often with extended-spectrum activity (ESBLs)

- Class B (Metallo-β-lactamases): Requires zinc ions for activity, capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems

- Class C (Serine-based): Primarily cephalosporinases (AmpC enzymes)

- Class D (Serine-based): Oxacillinases (OXA-type) with variable activity against carbapenems

Table 1: Major β-Lactamase Classes and Their Properties

| Class | Catalytic Mechanism | Representative Enzymes | Key Substrates | Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Serine hydrolase | TEM-1, SHV-1, CTX-M-15 | Penicillins, early cephalosporins | Clavulanic acid, sulbactam, tazobactam |

| B | Zinc-dependent metallo-enzyme | NDM-1, VIM, IMP | Carbapenems, penicillins, cephalosporins | EDTA, but no clinically available inhibitors |

| C | Serine hydrolase | AmpC, CMY-2 | Cephalosporins, cephamycins | Boronic acid derivatives, avibactam |

| D | Serine hydrolase | OXA-48, OXA-23 | Oxacillin, carbapenems (variable) | NaCl, but limited clinical inhibition |

Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes (AMEs)

Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs) represent another major group of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes that catalyze the chemical modification of aminoglycoside antibiotics through three primary mechanisms: N-acetylation (acetyltransferases), O-adenylylation (adenylyltransferases), and O-phosphorylation (phosphotransferases) [21] [17]. These modifications occur at key amino or hydroxyl groups essential for antibiotic binding to the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA, thereby reducing drug affinity for its target and diminishing antibacterial activity.

The genetic encoding of these enzymes varies, with many found on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and transposons, facilitating horizontal gene transfer between bacterial strains and species. This mobility has contributed to the widespread distribution of AMEs across clinically important pathogens, significantly limiting the therapeutic utility of aminoglycoside antibiotics [17].

Drug Target Modification Mechanisms

Alteration of Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs)

Bacteria can evade β-lactam antibiotics through modifications to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are the molecular targets for this drug class. These alterations include mutations that reduce antibiotic binding affinity, acquisition of low-affinity PBPs from other bacterial species, and overexpression of native PBPs [18]. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) represents the most clinically significant example, possessing the mecA gene that encodes PBP2a, a transpeptidase with markedly reduced affinity for β-lactam antibiotics [19].

In Gram-negative bacteria, PBP modifications contribute to resistance, though often to a lesser extent than β-lactamase production. In E. coli, mutations in PBP3 can confer resistance to specific β-lactams like ceftazidime and aztreonam, while maintaining susceptibility to other β-lactam antibiotics. This specificity highlights the precise structural relationship between PBPs and their antibiotic inhibitors [18].

Ribosomal Protection and Modification

Bacteria employ several strategies to protect or alter ribosomal targets from antibiotic inhibition. Methylation of specific nucleotides within the ribosomal RNA represents a particularly effective mechanism, as exemplified by Erm methylases that add methyl groups to the A2058 residue in 23S rRNA, conferring resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B antibiotics (MLSᵦ phenotype) [19].

Another significant mechanism involves mutations in genes encoding ribosomal proteins or rRNA, which can reduce antibiotic binding affinity without compromising essential ribosomal functions. For instance, mutations in the L4 and L22 ribosomal proteins or in 23S rRNA can confer resistance to macrolide antibiotics by altering the drug-binding pocket in the ribosomal tunnel [19].

Table 2: Bacterial Antibiotic Target Modification Mechanisms

| Target Site | Antibiotic Class | Resistance Mechanism | Key Genetic Determinants | Example Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal subunit (30S) | Aminoglycosides | rRNA methylation | ArmA, RmtA-E | K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa |

| Ribosomal subunit (50S) | Macrolides | rRNA methylation | Erm family | S. aureus, S. pneumoniae |

| Dihydrofolate reductase | Trimethoprim | Mutated enzyme | dfrA, dfrB | UPEC, S. aureus |

| RNA polymerase | Rifampicin | Mutated β-subunit | rpoB mutations | M. tuberculosis, MRSA |

| DNA gyrase/Topoisomerase IV | Fluoroquinolones | Mutated enzymes | gyrA, gyrB, parC, parE | E. coli, K. pneumoniae |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigation

Enzyme Kinetics and Inhibition Assays

Characterizing antibiotic-inactivating enzymes requires robust biochemical assays to determine kinetic parameters and inhibition profiles. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for β-lactamase activity assessment:

Protocol: β-Lactamase Kinetic Assay Using Nitrocefin Hydrolysis

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare assay buffer: 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.1 mg/mL BSA

- Prepare nitrocefin stock solution: 10 mM in DMSO (store protected from light)

- Prepare purified β-lactamase enzyme: Serial dilutions in assay buffer

Kinetic Measurements:

- Add 980 μL assay buffer to spectrophotometer cuvette

- Add 10 μL nitrocefin stock (final concentration 100 μM)

- Initiate reaction by adding 10 μL enzyme preparation

- Immediately monitor absorbance at 482 nm for 5 minutes (ε₄₈₂ = 15,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹)

Data Analysis:

- Calculate initial velocity from linear portion of progress curve

- Determine kcₐₜ and Kₘ using Michaelis-Menten equation

- For inhibition studies, pre-incubate enzyme with inhibitor for 10 minutes before substrate addition

This spectrophotometric method leverages the chromogenic shift of nitrocefin from yellow (λₘₐₓ = 390 nm) to red (λₘₐₓ = 482 nm) upon β-lactam ring hydrolysis, enabling real-time monitoring of enzyme activity [18] [17].

Molecular Docking and Structural Analysis

Computational approaches provide insights into the structural basis of drug target modifications:

Protocol: Molecular Docking of Antibiotics to Modified Targets

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain crystal structures of wild-type and mutant target proteins from PDB

- Remove water molecules and add hydrogen atoms using molecular modeling software

- Assign partial charges and protonation states appropriate for physiological pH

Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structures of antibiotic compounds from PubChem or similar databases

- Perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields

- Generate multiple conformations for flexible docking

Docking Simulation:

- Define binding site based on known catalytic residues or co-crystallized ligands

- Perform rigid receptor/flexible ligand docking using AutoDock Vina or similar software

- Run multiple simulations (≥20) with different random seeds to ensure reproducibility

- Analyze binding poses, interaction energies, and hydrogen bonding patterns

This approach enables quantitative comparison of antibiotic binding affinities to wild-type versus modified targets, identifying specific structural alterations responsible for resistance [18] [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogenic β-lactam substrates | Nitrocefin, CENTA | β-lactamase activity detection | Colorimetric change upon hydrolysis enables real-time kinetic measurements |

| Recombinant resistance enzymes | Purified β-lactamases, aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes | Biochemical characterization | Enables detailed kinetic studies without bacterial culture requirements |

| Gene expression systems | Inducible plasmids (pET, pBAD) | Heterologous expression | Allows controlled production of resistance proteins in model organisms |

| Antibiotic analogs | Fluorescently-labeled antibiotics, biotin-conjugated drugs | Cellular localization and binding studies | Permits visualization of drug distribution and target engagement |

| Chemical inhibitors | Clavulanic acid, avibactam, boronic acids | Enzyme inhibition profiling | Differentiates between β-lactamase classes and determines inhibition potency |

| Bacterial strain panels | ESKAPE pathogen sets, isogenic mutant collections | Comparative resistance studies | Provides standardized platforms for evaluating resistance mechanisms |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The expression of antibiotic resistance mechanisms is often tightly regulated through complex signaling pathways that sense antibiotic exposure and environmental stresses. The following diagram illustrates the regulatory network controlling the WhiB7-mediated antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, a key pathway in intrinsic drug resistance:

Regulatory Pathway of WhiB7-Mediated Resistance

This regulatory cascade demonstrates how Mycobacterium abscessus and related species coordinate resistance to multiple antibiotic classes. When ribosome-targeting antibiotics induce ribosomal stress, the transcription factor WhiB7 becomes activated and transactivates a regulon of over 100 genes involved in antimicrobial resistance [20]. Among these genes, Eis2 encodes a protein that modifies aminoglycoside antibiotics through acetylation, rendering them ineffective. Recent research has exploited this pathway by developing prodrug antibiotics that are activated by Eis2, effectively "hacking" the resistance mechanism to enhance drug efficacy [20].

The following experimental workflow outlines a comprehensive approach for investigating antibiotic target modifications:

Workflow for Investigating Target Modifications

Quantitative Analysis of Resistance Prevalence

Surveillance data and clinical studies provide crucial insights into the prevalence and distribution of specific resistance mechanisms across bacterial populations and geographic regions. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent investigations:

Table 4: Prevalence of Key Resistance Mechanisms in Clinical Isolates

| Resistance Mechanism | Pathogen | Antibiotic Affected | Prevalence Rate | Geographic Variation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESBL production | Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) | β-lactams | 14.6-60% | Significant regional variation | [18] |

| Plasmid-mediated dfrA genes | UPEC | Trimethoprim | Up to 32.1% in U.S. | Higher in recurrent UTIs | [18] |

| Sul gene acquisition | UPEC | Sulfamethoxazole | Correlates with TMP resistance | Regional patterns observed | [18] |

| QRDR mutations | UPEC | Fluoroquinolones | >30% in most regions | Increasing globally | [18] |

| WhiB7 regulon activation | M. abscessus | Ribosomal-targeting | Intrinsic resistance | Consistent across isolates | [20] |

| AcrAB-TolC efflux (overexpression) | UPEC | Multiple classes | High in biofilm-forming isolates | Associated with persistence | [21] |

These quantitative findings highlight the substantial burden of target modification and enzymatic inactivation mechanisms across clinically important pathogens. The data demonstrate significant geographic variation in resistance prevalence, underscoring the need for localized surveillance to inform empirical therapy guidelines and stewardship interventions [18] [22].

Structural evasion through drug target modifications and enzymatic inactivation represents a formidable challenge in clinical management of bacterial infections. The sophisticated molecular mechanisms underlying these resistance strategies, coupled with their rapid dissemination via mobile genetic elements, have contributed significantly to the global AMR crisis. Future research directions should focus on leveraging structural biology insights to design novel antibiotics less susceptible to these evasion strategies, developing combination therapies that target resistance mechanisms directly, and exploring innovative approaches such as resistance "hacking" that repurpose bacterial defense systems for therapeutic benefit [20]. As our understanding of these fundamental resistance mechanisms deepens, so too will our capacity to develop effective countermeasures against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most severe threats to global public health, with drug-resistant bacterial infections causing over 1 million deaths annually and posing a critical challenge to modern medicine [23]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified a group of bacterial pathogens of global priority, highlighting the acute threat posed by species with intrinsic and acquired multidrug resistance [24]. These "critical priority" pathogens, primarily Gram-negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, exhibit a remarkable capacity to resist the effects of most available antibiotics, including the last-resort treatments like carbapenems [23]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms, epidemiology, and research methodologies for these bacteria is fundamental to developing novel countermeasures. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical profile of these clinically critical intrinsically resistant bacteria within the context of ongoing global research efforts to combat the AMR crisis.

The WHO Priority Pathogens List: A Framework for Threat Assessment

The WHO released its first list of priority bacterial pathogens in 2017, categorizing 12 families of bacteria into critical, high, and medium priority tiers based on urgency for new research and development [24]. This list was designed to guide and encourage the development of new antibiotics. The criteria for this classification included the pathogen's mortality rates, prevalence in community and healthcare settings, ease of transmission, the availability of effective treatments, and whether prevention strategies are possible [23].

In 2024, a second alert was released, regrettably listing almost the same set of bacterial species, underscoring the lack of sufficient progress in developing effective treatments over the intervening years [24]. The critical priority pathogens, which represent the gravest threat, are multidrug-resistant bacteria that primarily cause severe and often fatal infections in hospitalized patients, the elderly, and those using medical devices such as ventilators and blood catheters [23] [25]. These include:

- Acinetobacter baumannii (carbapenem-resistant)

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (carbapenem-resistant)

- Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, carbapenem-resistant, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant)

The persistence of these pathogens on the WHO list highlights the fragility of the current antibacterial research and development (R&D) ecosystem. As of 2025, the clinical pipeline remains insufficient, with only 90 antibacterial agents in clinical development, a decrease from 97 in 2023. Of these, a mere 5 are effective against at least one of the "critical" priority bacteria [26].

Profiles of Critical Priority Pathogens and Their Resistance Mechanisms

The bacteria designated as critical priority by the WHO are characterized by a formidable array of intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms. The following section details the profiles and molecular strategies of the most threatening pathogens.

Table 1: Clinical Impact and Resistance Profiles of Critical WHO Pathogens

| Pathogen | Common Infection Types | Key Intrinsic/Acquired Resistance Mechanisms | Noteworthy Resistance Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Bloodstream infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, wound infections | Production of all four classes of β-lactamases (A, B, C, D); expression of efflux pumps; altered target sites [23]. | Over 80% of isolates were carbapenem-non-susceptible in a 2023-2024 study [25]. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pneumonia (especially in CF patients), bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections | Low membrane permeability; constitutive expression of efflux pumps; production of β-lactamases and carbapenemases; biofilm formation [23]. | A leading drug-resistant Gram-negative bacterium in bloodstream infections [7]. |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Bloodstream infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, intra-abdominal infections | Production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, NDM) [7] [23]. | >55% globally resistant to 3rd-gen cephalosporins; >40% of isolates in a recent study were MDR/XDR [7] [25]. |

| Escherichia coli | Urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, bloodstream infections | Production of ESBLs and carbapenemases; plasmid-mediated resistance gene transfer [7] [23]. | >40% globally resistant to 3rd-gen cephalosporins; a leading cause of resistant community and hospital-acquired infections [7]. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance

The resilience of these critical pathogens stems from their diverse and often synergistic resistance strategies, which can be categorized into four main groups:

- Enzymatic Inactivation of Antibiotics: This is a primary mechanism for resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Pathogens like A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae produce a wide variety of β-lactamase enzymes, including extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, NDM, OXA), which hydrolyze and inactivate the antibiotic molecules [23].

- Reduced Drug Permeability and Efflux Pumps: Gram-negative bacteria have a low-permeability outer membrane that intrinsically restricts the entry of many antibiotics. Furthermore, they express efflux pumps (e.g., in A. baumannii) that actively export multiple classes of antibiotics—such as aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones—from the cell, conferring a multidrug-resistant phenotype [23].

- Target Site Modification: Bacteria can alter the molecular targets of antibiotics through mutation or enzymatic modification. For example, mutations in DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV reduce the efficacy of fluoroquinolones, while modification of the ribosomal target site can confer resistance to aminoglycosides and macrolides [23] [27].

- Biofilm Formation and Collective Tolerance: Within polymicrobial infections, bacterial communities can form biofilms that provide collective tolerance. The biofilm matrix limits antibiotic diffusion and creates nutrient and oxygen gradients that reduce the metabolic activity of cells in the interior, increasing the proportion of persister cells that survive treatment [28].

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic interplay of these core resistance mechanisms within a bacterial cell.

Advanced Methodologies for Resistance Surveillance and Profiling

Tracking the emergence and spread of AMR requires sophisticated surveillance methods that extend beyond clinical settings into the environment. Key experimental approaches for monitoring antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are detailed below.

Protocol: Environmental Surveillance of ARGs via Concentration and qPCR/ddPCR

Wastewater and biosolids are hotspots for the accumulation and potential dissemination of ARGs. This protocol outlines a comparative approach for concentrating and quantifying ARGs from these complex matrices [29].

- Objective: To compare the efficiency of two concentration methods—Filtration–Centrifugation (FC) and Aluminum-based Precipitation (AP)—coupled with two detection techniques—quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)—for quantifying specific ARGs in secondary treated wastewater and biosolids.

- Sample Collection: Collect 1L samples of secondary treated wastewater and biosolids from urban wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Store at 4°C until analysis.

- Concentration Methods:

- Filtration–Centrifugation (FC): Filter 200 mL of wastewater through a 0.45 µm sterile filter. The filter is then placed in buffered peptone water, agitated, and sonicated. The resulting suspension is centrifuged (3000× g for 10 min), and the pellet is resuspended in PBS [29].

- Aluminum-based Precipitation (AP): Adjust the pH of 200 mL of wastewater to 6.0. Add AlCl₃ to a final concentration of 0.9 N, shake, and centrifuge (1700× g for 20 min). The pellet is reconstituted in 3% beef extract and centrifuged again, with the final pellet resuspended in PBS [29].

- DNA Extraction: Extract and purify DNA from the concentrated samples and biosolids using a commercial kit (e.g., Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit).

- ARG Quantification:

- qPCR: Perform using standard curves for absolute or relative quantification. It is highly sensitive but can be impaired by matrix-associated inhibitors [29] [30].

- ddPCR: Partition the sample into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets for absolute quantification without a standard curve. This method reduces the impact of inhibitors and offers enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance ARGs [29].

- Key Findings: The AP method generally provides higher ARG concentrations than FC, particularly in wastewater. ddPCR demonstrates greater sensitivity than qPCR in wastewater, whereas in biosolids, both methods perform similarly [29].

Protocol: Comparative ARG Profiling via HT-qPCR and Metagenomics

This protocol describes a systematic comparison of High-Throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) and metagenomic sequencing for ARG profiling in environmental samples, such as aquaculture water and sediments [30].

- Objective: To evaluate the performance of HT-qPCR and metagenomic sequencing in characterizing ARG profiles and to develop a risk assessment model for ARGs detected by HT-qPCR.

- Sample Processing: Extract total DNA from environmental samples (water, sediment).

- Parallel Analysis:

- HT-qPCR: Analyze DNA using pre-designed primer sets targeting specific ARGs (e.g., 31-40 targets). This method provides absolute quantification of ARG abundance and is highly sensitive for low-abundance targets [30].

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Sequence the same DNA extracts on an Illumina or similar platform. Process raw sequences to profile the microbial community and identify ARG subtypes and their genetic contexts (e.g., proximity to mobile genetic elements) via alignment to reference databases [30].

- Data Integration and Risk Assessment:

- A novel risk assessment model can be developed for HT-qPCR data by integrating the absolute abundance of ARGs, their detection frequency, the co-occurrence with mobile genetic elements (inferring horizontal gene transfer potential), and the pathogenicity of the bacterial hosts identified via 16S rRNA sequencing [30].

- This model allows for the prioritization of high-risk ARG subtypes, such as mexF, ereA, and sul2, facilitating targeted control measures [30].

The workflow for this comparative analysis and risk assessment is outlined below.

Research into intrinsically resistant bacteria relies on a suite of specialized reagents and platforms. The following table catalogues key solutions for critical experimental procedures in AMR research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AMR Studies

| Category / Reagent | Specific Example(s) | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Automated ID & AST Systems | Vitek 2 Compact System (Biomerieux) with GN cards and AST-N233/XNO5 cards [25] | Automated bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) by Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). |

| Standardized AST Methods | Broth microdilution (e.g., ComASP Colistin Test Panel); CLSI guidelines [25] | Reference methods for confirming resistance, especially for last-resort antibiotics like colistin. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit (Promega) [29] | Automated extraction of high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA from complex matrices like biosolids and wastewater. |

| qPCR/ddPCR Platforms | Quantitative PCR (qPCR); Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) [29] | Sensitive detection and absolute quantification of specific antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). |

| High-Throughput PCR | WaferGen SmartChip for HT-qPCR [30] | Simultaneous quantification of hundreds to thousands of ARG targets across many samples. |

| Priority ARG Targets | blaCTX-M, blaNDM, blaKPC, blaOXA, mecA, vanA, mcr, tet(A) [29] [30] | Key resistance genes against critical antibiotics (β-lactams, glycopeptides, colistin, tetracyclines) for surveillance. |

| Concentration Reagents | Aluminum Chloride (AlCl₃); Buffered Peptone Water with Tween [29] | Concentrating bacterial cells and viral particles (including phages) from large-volume water samples for downstream analysis. |

The WHO critical priority pathogens, with their formidable array of intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms, represent a persistent and evolving threat to global health. The continued dominance of Gram-negative bacteria like carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae on the WHO list, coupled with an insufficient and fragile antibacterial R&D pipeline, underscores the urgent need for a paradigm shift in how we approach this crisis. A comprehensive strategy is required, one that integrates robust national and international surveillance using advanced molecular methods, a deeper ecological understanding of resistance gene flow through the "One Health" continuum, and sustained investment in the discovery of innovative therapeutics and rapid diagnostics. Without coordinated global action to address the scientific, economic, and public health challenges of AMR, the prospect of a post-antibiotic era becomes increasingly imminent.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global public health challenges of our time, directly threatening the efficacy of modern medicine. The One Health approach recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is interconnected and that AMR emergence and dissemination must be understood through this integrated lens [31]. Resistant bacteria and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) circulate continuously between human, animal, and environmental reservoirs through complex transmission pathways, making containment through human healthcare measures alone impossible [32].

The environmental and agricultural dimensions of AMR are particularly critical as they represent often overlooked amplifiers of resistance. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of these reservoirs, focusing on their role in the broader context of bacterial species with natural antibiotic resistance. We synthesize current scientific understanding of reservoir dynamics, transmission mechanisms, and surveillance methodologies to inform research and drug development initiatives aimed at mitigating AMR spread.

The Scope of the Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis

The global burden of AMR continues to escalate at an alarming rate. According to recent World Health Organization (WHO) surveillance data from over 100 countries, one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections in 2023 were resistant to standard antibiotic treatments [7]. Between 2018 and 2023, antibiotic resistance increased in over 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations monitored, with an average annual increase of 5-15% [7] [33].

Regional disparities in resistance patterns highlight the complex interplay of socioeconomic and healthcare factors. The WHO South-East Asian and Eastern Mediterranean Regions report the highest resistance rates, with approximately one in three reported infections demonstrating resistance, compared to one in five in the African Region [7] [33]. Gram-negative bacteria pose a particularly severe threat, with more than 40% of Escherichia coli and over 55% of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates globally now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, first-line treatments for serious infections [7].

In the United States, specific resistant pathogens have demonstrated dramatic increases. Infections caused by NDM-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (NDM-CRE) surged by more than 460% between 2019 and 2023 [34]. These pathogens produce the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) enzyme that confers resistance to nearly all available antibiotics, including last-resort carbapenems [34].

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Key Bacterial Pathogens

| Bacterial Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Resistance Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% globally, >70% in some regions | Leading cause of drug-resistant bloodstream infections [7] |

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% globally | Major pathogen in urinary and gastrointestinal infections [7] |

| Acinetobacter spp. | Carbapenems | Increasing frequency | Narrowing treatment options, rising resistance to last-resort antibiotics [7] |

| Enterobacterales | Carbapenems (NDM-producing) | 460% increase (2019-2023) | Particularly NDM-CRE strains; few effective treatments available [34] |

Environmental Reservoirs of Antimicrobial Resistance

Aquatic Environments and Biofilms

Aquatic ecosystems serve as critical reservoirs and conduits for the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs. The continuous discharge of wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents, agricultural runoff, and other anthropogenic sources introduces antibiotics, biocides, heavy metals, and resistant bacteria into aquatic systems [35]. Although antibiotic concentrations in these environments are typically sub-inhibitory (ng/L to μg/L), they function as signaling molecules that promote horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and maintain a persistent pool of resistance genes in native microbial communities [35] [36].

Biofilms represent particularly efficient environmental reservoirs for AMR. These structured multicellular communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix exhibit intrinsic physiological characteristics that enhance resistance dissemination [35]. The EPS matrix acts as a protective barrier that limits antibiotic penetration while maintaining high bacterial density and proximity that facilitates genetic exchange [35] [36]. Biofilms demonstrate 10 to 1,000 times reduced susceptibility to antimicrobial agents compared to their planktonic counterparts [35].

Table 2: Mechanisms of Enhanced Antibiotic Resistance in Environmental Biofilms

| Mechanism | Functional Significance | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Physical barrier | EPS matrix limits antibiotic diffusion | Creates chemical gradients and protected niches [35] |

| Metabolic heterogeneity | Includes dormant "persister" cells | Non-growing cells tolerate antibiotic exposure [35] |

| HGT facilitation | High cell density promotes genetic exchange | Conjugation rates 2-5 times higher under sub-MIC antibiotics [35] |

| Stress response activation | Sub-MIC antibiotics induce defense mechanisms | Antibiotics function as signaling molecules [35] |

| e-DNA retention | Extracellular DNA concentrated in matrix | Provides raw material for natural transformation [36] |

The genetic mobilome within biofilms—including plasmids, transposons, insertion sequences, bacteriophages, integrons, and extracellular DNA—creates an efficient infrastructure for HGT [36]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MIC) of antibiotics significantly increase the prevalence of mobile genetic elements, particularly Class 1 integrons, in freshwater biofilms exposed to treated sewage effluent [36]. This enhanced gene transfer capacity, combined with the constant selective pressure of environmental antibiotics, establishes biofilms as hotspots for the evolution and dissemination of novel resistance combinations.

Soil and Agricultural Environments

Agricultural systems represent profound amplifiers of AMR through the application of livestock manure, dairy lagoon effluent, and treated wastewater to farmland [37]. These practices introduce ARBs, ARGs, and selective agents (antibiotics, biocides, heavy metals) directly into soil ecosystems, where they can persist and transfer resistance to indigenous soil bacteria [37] [38].

Metagenomic analyses of livestock waste have revealed distinct resistance profiles dominated by specific antibiotic classes. In swine manure, aminoglycoside resistance genes represent 40-55% of the identified resistome, followed by tetracycline (30-45%), beta-lactam (20-35%), and macrolide (18-30%) resistance genes [37]. Network analyses demonstrate co-occurrence patterns between transporter genes, regulator genes, efflux pumps, and specific ARGs, with phyletic affiliations primarily with Bacteroidetes fragilis and Enterobacter aerogenes [37].

The diagram below illustrates the complex interactions and transmission pathways of AMR within the One Health framework:

Agricultural Reservoirs and Transmission Pathways

Livestock Production Systems

The use of antibiotics in livestock production constitutes a significant driver of AMR emergence. Prophylactic and growth-promoting applications in food animals create sustained selective pressures that enrich for resistant bacteria and ARGs within animal microbiomes [31]. Comparative studies demonstrate dramatically increased AMR abundance in the gut of farm animals (chicken, turkey, pig) compared to wild animals (boars, foxes, rodents) [31]. Longitudinal research in swine and broiler operations has documented concomitant increases in AMR in Enterococcus spp. following antibiotic administration [31].

The impact of antibiotic use extends beyond pathogenic bacteria to encompass commensal organisms that serve as ARG reservoirs. Investigations into the poultry resistome reveal that optimized doses of enrofloxacin cause significant perturbations in the gut microbiota and increase ARG diversity, while synbiotic supplementation can reduce the number of enriched ARGs [39]. This suggests that nutritional interventions may partially mitigate antibiotic-induced resistome expansion.

Transmission to Humans

The transmission of AMR from agricultural operations to humans occurs through multiple exposure routes:

Foodborne transmission: Resistant bacteria from food animals contaminate products throughout the supply chain. Studies have identified multidrug-resistant Salmonella from poultry, cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from veal calves, and carbapenem-resistant E. coli from pigs [31]. Additionally, diverse carbapenem-resistant bacteria (Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Myroides) have been detected in seafood products, highlighting that non-pathogenic bacteria regularly excluded from surveillance programs may serve as resistance reservoirs [31].

Occupational exposure: Direct contact with food animals represents a significant transmission risk. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) has been identified in workers at industrial livestock operations but not in workers at antibiotic-free operations [31]. Genomic studies confirm that MRSA ST398 strains can spread among swine, humans, and the environment, with potential international transmission [39].

Environmental dissemination: Agricultural runoff and manure application contaminate waterways and soils with ARBs and ARGs, creating extended exposure pathways for surrounding communities. This is particularly problematic in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where high population density, poorer sanitation, and intensive animal farming practices create conditions conducive to inter-reservoir transmission [38].

Methodologies for AMR Surveillance and Analysis

Experimental Approaches for Reservoir Tracking

Understanding AMR dynamics across One Health reservoirs requires integrated surveillance methodologies that combine cultivation-dependent and molecular approaches. The following experimental workflow outlines a comprehensive approach to characterizing AMR in environmental and agricultural reservoirs:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for AMR Reservoir Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Media | Chromogenic agar with antibiotics; MacConkey agar with cephalosporins | Isolation and presumptive identification of resistant Enterobacterales [39] |

| Molecular Biology | PCR primers for blaNDM, blaCTX-M, mcr-1; Sanger sequencing | Targeted detection and confirmation of specific resistance genes [39] [34] |

| Genomic Sequencing | Illumina short-read; PacBio SMRT sequencing; Metagenomic libraries | Comprehensive resistome characterization; plasmid reconstruction [37] [39] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | CARD; ResFinder; MLST; Prokka | ARG annotation; strain typing; genome annotation [37] [39] |

| Culture Supplements | Sub-MIC antibiotics; Synbiotic formulations | Simulation of environmental conditions; mitigation studies [35] [39] |

Protocol for Resistome Analysis in Environmental Samples

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect environmental samples (water, soil, biofilm) using sterile containers and maintain cold chain during transport

- For biofilms, gently scrape submerged surfaces with sterile implements and homogenize in buffer

- Process samples within 24 hours of collection

Metagenomic DNA Extraction:

- Use commercial soil or water DNA extraction kits with bead-beating step for comprehensive cell lysis

- Include negative extraction controls to monitor contamination

- Assess DNA quality and quantity using fluorometric methods

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare metagenomic sequencing libraries using Illumina-compatible protocols

- Sequence to a minimum depth of 10-20 million reads per sample

- Include positive controls with known ARG composition for quality assessment

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform quality control of raw reads using FastQC and Trimmomatic

- Conduct assembly using metaSPAdes or Megahit

- Annotate ARGs using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) with RGI

- Perform taxonomic classification using Kraken2 or MetaPhlAn

- Conduct statistical analysis in R with vegan and phyloseq packages

This protocol enables comprehensive characterization of resistomes and identifies co-occurrence patterns between ARGs, mobile genetic elements, and taxonomic markers, providing critical insights into AMR dissemination pathways.

The environmental and agricultural dimensions of AMR represent critical components of the resistance lifecycle that demand increased research attention. The One Health perspective provides an essential framework for understanding the complex interactions between human, animal, and environmental reservoirs that drive the emergence and dissemination of resistant strains [31] [32]. Current evidence unequivocally demonstrates that interventions focused solely on human healthcare settings cannot adequately address the global AMR crisis.

Future research priorities should include:

- Enhanced surveillance integrating genomic and metagenomic approaches across all One Health sectors

- Elucidation of the ecological and evolutionary dynamics driving HGT in environmental hotspots

- Development of interventional strategies to disrupt AMR transmission at the human-animal-environment interface

- Innovation in wastewater treatment and agricultural waste processing to reduce AMR dissemination

The role of environmental bacteria as sources of novel ARGs that can transfer to pathogenic species under antibiotic selection pressure necessitates a fundamental reexamination of AMR containment strategies [38]. Reducing the environmental burden of AMR will require improved waste treatment, restricted antibiotic use in humans and animals, prioritization of less environmentally persistent antibiotics, and better control of pharmaceutical manufacturing discharges [38]. Through coordinated, transdisciplinary approaches aligned with One Health principles, the scientific community can develop effective strategies to mitigate this escalating global health threat.

Advanced Research Tools: Profiling and Combatting Innate Bacterial Defenses

Genomic and Metagenomic Approaches for Decoding Intrinsic Resistomes

The intrinsic resistome encompasses all innate, chromosomal genes that contribute to a bacterium's natural resistance to antibiotics, a phenomenon independent of horizontal gene transfer or prior antibiotic exposure [40]. This concept fundamentally expands our understanding of antibiotic resistance beyond acquired mechanisms to include a complex network of inherent genetic factors. The intrinsic resistome is universally present within bacterial species and predates the clinical use of antibiotics, representing a natural defense arsenal that dramatically limits therapeutic options, particularly for Gram-negative pathogens [40].

Understanding the intrinsic resistome is crucial for addressing the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are associated with significant increases in morbidity and mortality rates, longer hospital stays, and higher treatment costs [41]. The intrinsic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria, mediated by their outer membrane and active efflux systems, presents a particularly pressing clinical challenge that restricts available treatments [40]. Decoding these innate resistance mechanisms through genomic and metagenomic approaches provides the foundational knowledge needed to develop novel therapeutic strategies to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Intrinsic Resistance

Bacteria employ multiple sophisticated mechanisms to achieve intrinsic antibiotic resistance, with the most well-characterized being permeability barriers and efflux systems.

Outer Membrane Permeability

The Gram-negative outer membrane serves as a formidable permeability barrier that effectively excludes many antimicrobial compounds. This protective structure is composed of an asymmetric lipid bilayer containing lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet [40]. The limited fluidity of this membrane, compared to the cytoplasmic membrane, significantly reduces its permeability to hydrophobic compounds. Integral outer membrane proteins (porins) form water-filled channels that permit the passive diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules, but their size selectivity and charge characteristics restrict the passage of many antibiotics [40]. This selective permeability represents a primary intrinsic resistance mechanism in Gram-negative bacteria.