Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance: Core Mechanisms, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Breakthroughs

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the fundamental mechanisms underpinning intrinsic antibiotic resistance, a critical and growing challenge in clinical microbiology and drug development.

Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance: Core Mechanisms, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the fundamental mechanisms underpinning intrinsic antibiotic resistance, a critical and growing challenge in clinical microbiology and drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and pharmaceutical professionals, it explores the innate, chromosomally encoded defenses that render bacterial species impervious to certain antimicrobial agents from the outset. The scope ranges from foundational concepts—detailing the roles of impermeable membranes, constitutive efflux pumps, and innate enzymatic inactivation—to advanced methodological approaches for studying these barriers. It further investigates innovative strategies to circumvent resistance, including antibiotic potentiators and structure-based drug design, and concludes with a comparative evaluation of resistance across priority pathogens and future directions for revitalizing the antibacterial pipeline. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this review serves as a vital resource for navigating the complexities of intrinsic resistance and developing next-generation therapeutics.

The Innate Fortress: Deconstructing Fundamental Mechanisms of Intrinsic Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a severe global health threat, projected to cause 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if left unaddressed [1]. A comprehensive understanding of resistance mechanisms is fundamental to combating this crisis. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the core distinctions between intrinsic and acquired resistance, with particular focus on the interplay between constitutive and inducible traits. We explore the genetic basis, molecular mechanisms, and experimental approaches for investigating these resistance forms, framing our discussion within the context of intrinsic antibiotic resistance research. For researchers and drug development professionals, we present quantitative data, detailed methodologies, and essential research tools to advance the development of novel therapeutic strategies against resistant pathogens.

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria evolve mechanisms to evade the effect of antimicrobial agents [2]. This multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype undermines decades of progress in infectious disease control and threatens modern medical procedures [1]. Resistance mechanisms are broadly categorized as either intrinsic or acquired, based on their genetic origin and evolutionary history.

Simultaneously, resistance traits can be classified by their expression patterns as constitutive (always expressed) or induced (expressed only upon encountering specific stimuli, such as an antibiotic) [2]. Understanding the relationship between these classifications is crucial for designing effective countermeasures. The intrinsic resistome—the collection of all chromosomally encoded elements that contribute to intrinsic resistance—has emerged as a promising target for novel antibiotics and resistance breakers [3] [4].

Defining Resistance Categories

Intrinsic vs. Acquired Resistance

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Intrinsic and Acquired Resistance

| Feature | Intrinsic Resistance | Acquired Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Chromosomal genes present in all strains of a bacterial species [2] [4] | Horizontal gene transfer (plasmids, transposons) or chromosomal mutations [5] [2] |

| Prevalence | Universal within a species; independent of antibiotic exposure [4] | Variable; depends on selective pressure and transmission [5] |

| Evolutionary Origin | Predates antibiotic chemotherapy; ancient [4] | Arises during antibiotic therapy or through contact with resistant bacteria [2] |

| Examples | Gram-negative outer membrane; efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [5] [4] | MRSA (mecA gene); ESBL-producing E. coli [1] [5] |

Intrinsic resistance refers to the innate ability of a bacterial species to withstand antibiotic action due to its inherent structural or functional characteristics [2] [6]. This resistance is genetically hardwired, independent of horizontal gene transfer or previous antibiotic exposure [4]. The conventional example is the multi-drug resistant phenotype exhibited by Gram-negative bacteria, attributed to the presence of a protective outer membrane and constitutive expression of efflux pumps [4].

Acquired resistance develops when previously susceptible bacteria gain the ability to survive antibiotic treatment through genetic changes [2] [6]. This can occur via spontaneous mutations in chromosomal genes or through horizontal acquisition of resistance genes on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, transposons, or integrons [5] [2]. A prominent example is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which acquires the mecA gene encoding an altered penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a) with low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics [1] [5].

Constitutive vs. Induced Resistance

Table 2: Comparison of Constitutive and Induced Resistance Traits

| Characteristic | Constitutive Resistance | Induced Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Pattern | Constant, baseline expression [2] | Triggered by environmental signals (e.g., antibiotic presence) [2] |

| Genetic Regulation | Not subject to conditional regulation | Tightly regulated by specific inducer systems |

| Energy Cost | Constant metabolic burden [7] | Temporary burden only during induction |

| Response Time | Immediate protection | Delayed protection until induction occurs |

| Examples | Porins in Gram-negative outer membrane [4] | WhiB7 regulon in Mycobacterium abscessus [8] |

Constitutive resistance traits are consistently expressed at a baseline level, providing constant protection regardless of environmental conditions [2]. From an evolutionary perspective, constitutive expression is maintained when the threat of antibiotic exposure is constant or unpredictable, justifying the continuous metabolic expenditure [7].

Induced resistance traits are expressed only when triggered by specific environmental signals, such as antibiotic exposure [2]. This inducible expression provides an adaptive advantage by minimizing metabolic costs in the absence of threats while enabling rapid protection when challenged [7]. A sophisticated example is the WhiB7 "resistome" in Mycobacterium abscessus, a master regulator activated by ribosomal stress that controls over 100 proteins involved in antimicrobial resistance when antibiotics target the ribosome [8].

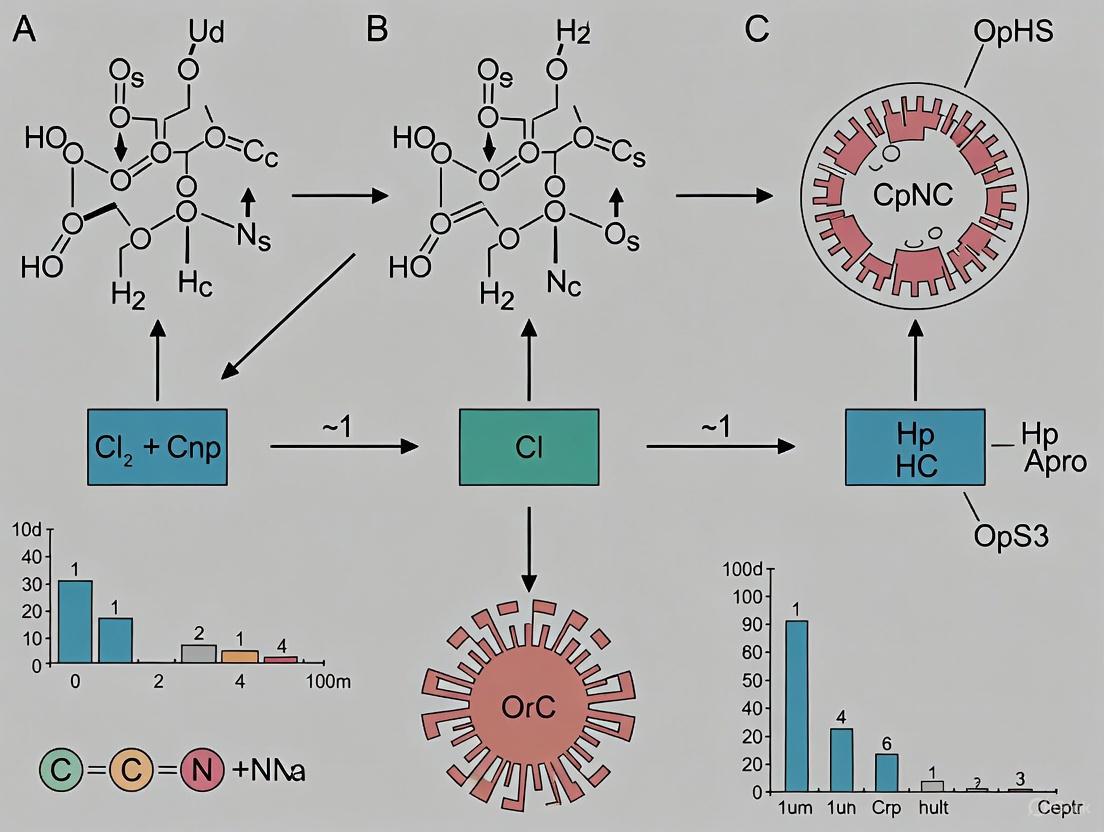

Diagram 1: Relationship between resistance classification systems. The conceptual frameworks of intrinsic/acquired and constitutive/induced represent different axes for classifying resistance mechanisms, with significant overlap between categories.

Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance

Fundamental Resistance Mechanisms

Bacteria employ four primary biochemical strategies to circumvent antibiotic activity, which can operate through either constitutive or induced systems:

Enzymatic Inactivation or Modification: Production of enzymes that degrade or modify antibiotics, rendering them ineffective [1] [5]. β-lactamases represent the most prominent example, with extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) constituting a major clinical concern [5]. Expression can be constitutive or induced upon antibiotic exposure.

Target Site Modification: Alteration of antibiotic binding sites through mutation or enzymatic modification [1] [5]. In MRSA, the acquired mecA gene constitutively produces PBP2a, an alternative penicillin-binding protein with low affinity for β-lactams [5].

Reduced Permeability or Enhanced Efflux: Decreased antibiotic accumulation via impaired uptake or active efflux [1] [5] [4]. Gram-negative bacteria intrinsically resist many antibiotics due to their outer membrane barrier and constitutively expressed efflux pumps like AcrAB-TolC in E. coli [3] [4].

Bypass Pathways or Target Protection: Development of alternative metabolic pathways or production of proteins that protect antibiotic targets [1].

The Intrinsic Resistome of Gram-Negative Bacteria

The intrinsic resistome of Gram-negative pathogens presents a formidable clinical challenge due to its multi-layered architecture:

Outer Membrane Permeability Barrier: The Gram-negative outer membrane, with its asymmetric lipid bilayer containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), functions as a formidable constitutive barrier to many antibiotics [4]. The flexibility and packing of LPS molecules determine membrane fluidity and permeability, with tighter packing reducing penetration of hydrophobic compounds [4]. Porins facilitate selective uptake of nutrients and small molecules, but their expression and characteristics can limit antibiotic penetration [4].

Active Efflux Systems: Resistance-nodulation-division (RND) superfamily efflux pumps, such as AcrAB-TolC in E. coli and MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa, contribute substantially to intrinsic resistance through constitutive expression [5] [4]. These tripartite systems span both membrane layers and actively extrude diverse antibiotics, often exhibiting broad substrate specificity [4]. Research demonstrates that knocking out efflux pump genes like acrB creates hypersusceptibility to multiple antibiotic classes [3].

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Intrinsic Resistance Mechanisms in E. coli

| Genetic Modification | Antibiotic Tested | Effect on Susceptibility | Key Findings | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔacrB (efflux pump) | Trimethoprim | Hypersusceptibility | Most compromised in evolving resistance; promising for "resistance proofing" [3] | Genome-wide knockout screen |

| ΔrfaG (cell envelope biogenesis) | Trimethoprim | Hypersusceptibility | High drug regimes drove knockout to extinction more frequently than wild type [3] | Genome-wide knockout screen |

| ΔlpxM (cell envelope biogenesis) | Trimethoprim | Hypersusceptibility | Adapted at sub-inhibitory concentrations via target mutations [3] | Genome-wide knockout screen |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Screening for Intrinsic Resistance Factors

Objective: Identify chromosomal genes contributing to intrinsic antibiotic resistance through systematic screening of mutant libraries.

Protocol (adapted from Balachandran et al., 2025 [3]):

- Library Preparation: Utilize a comprehensive single-gene knockout collection (e.g., Keio collection for E. coli with ~3,800 mutants).

- Growth Conditions: Culture knockout strains in duplicate in LB media supplemented with antibiotic at predetermined IC₅₀ values alongside antibiotic-free controls.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) after incubation period to quantify growth inhibition.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate fold growth relative to wild type for each knockout.

- Generate Gaussian distribution of drug susceptibilities with mean ≈1.

- Classify hypersensitive mutants as those showing growth lower than two standard deviations from the median in antibiotic media but normal growth in control media.

- Functional Enrichment: Categorize identified genes into functional pathways (e.g., cell envelope biogenesis, membrane transport, information transfer) using databases such as Ecocyc.

Key Outputs: Identification of drug-specific and drug-agnostic gene targets; revelation of network interactions within the intrinsic resistome.

Experimental Evolution for Resistance Proofing

Objective: Evaluate the potential of intrinsic resistance targets to prevent or delay evolution of antibiotic resistance.

Protocol (adapted from Balachandran et al., 2025 [3]):

- Strain Selection: Compare wild-type and knockout strains (e.g., ΔacrB, ΔrfaG, ΔlpxM) hypersusceptible to target antibiotic.

- Evolution Conditions: Propagate strains in serial passages under high and sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations.

- Monitoring: Track population survival and extinction events across passages.

- Genomic Analysis: Sequence adapted strains to identify resistance-conferring mutations (e.g., in folA for trimethoprim resistance).

- Comparison: Assess differential adaptability between wild-type and knockout strains.

Key Outputs: Determination of which intrinsic resistance mechanisms, when targeted, most effectively constrain evolutionary pathways to resistance; identification of compensatory mutations.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for identifying and validating intrinsic resistance targets. The pipeline integrates genome-wide screening with experimental evolution to pinpoint targets with potential for resistance-proofing therapeutic strategies.

Research Tools and Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Intrinsic Resistance Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keio Knockout Collection | Genome-wide single-gene knockout library for E. coli | Systematic identification of intrinsic resistance genes [3] | ~3,800 non-essential gene knockouts; systematic coverage |

| Conditional Expression Systems | Inducible control of gene expression | Study essential resistance genes; mimic induction [3] | Tight regulation; tunable expression levels |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | Chemical inhibition of efflux activity | Potentiate antibiotic efficacy; study efflux contributions [3] | e.g., Chlorpromazine, Piperine; mechanism validation |

| High-Throughput Screening | Automated susceptibility testing | Parallel assessment of mutant libraries [3] | 96-well/384-well formats; robotic automation |

| Genome Sequencing | Identification of resistance mutations | Track evolutionary adaptation [3] | Whole-genome or targeted sequencing |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | Global gene expression profiling | Identify induced resistance regulons [8] | RNA-seq; microarray analysis |

Emerging Concepts and Research Directions

Resistance Hacking: Exploiting Resistance Mechanisms

A groundbreaking approach termed "resistance hacking" involves structurally modifying antibiotics to exploit bacterial resistance mechanisms against themselves [8]. Proof-of-concept research demonstrates that a modified version of florfenicol exploits the WhiB7-induced Eis2 protein in Mycobacterium abscessus to perpetually amplify the antibiotic effect [8]. Specifically, the prodrug is activated by Eis2, whose expression increases as WhiB7 is activated, creating a perpetual cascade that continuously amplifies antibiotic concentration [8].

This approach represents a paradigm shift from circumventing resistance to weaponizing the resistance machinery itself, offering species-specific targeting that minimizes collateral damage to the host microbiome and reduces toxicity [8].

Evolutionary Constraints and Resistance Proofing

Research increasingly focuses on "resistance proofing" strategies that target intrinsic resistance mechanisms to constrain bacterial evolvability [3]. Studies comparing different hypersusceptible E. coli knockouts reveal that ΔacrB (efflux-deficient) strains are most compromised in their ability to evolve resistance, establishing efflux inhibition as a promising resistance-proofing strategy [3].

However, at sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations, hypersusceptible knockouts can adapt through mutations in drug-specific resistance pathways rather than compensatory evolution, frequently involving upregulation of the drug target [3]. This highlights the importance of considering evolutionary dynamics when targeting intrinsic resistance mechanisms.

Quantitative Prediction of Resistance Evolution

Systems biology approaches integrating quantitative models with multiscale data from microbial evolution experiments show promise for predicting AMR evolution [9]. The predictability of an evolutionary process can be defined by the existence of a probability distribution of outcomes, while repeatability relates to the likelihood of specific events within that distribution [9].

Measures such as Shannon entropy can quantify evolutionary repeatability, with higher entropy indicating greater uncertainty in evolutionary outcomes [9]. Research indicates that larger selection pressures generate more repeatable evolution, and resistance evolution demonstrates considerable predictability at the phenotypic level despite genetic heterogeneity [9].

The distinction between intrinsic and acquired resistance, coupled with the constitutive versus induced expression of resistance traits, provides essential frameworks for understanding bacterial adaptation to antibiotics. The intrinsic resistome represents a complex network of chromosomal elements that contribute to baseline resistance, extending beyond the traditional concepts of permeability barriers and efflux pumps.

Experimental approaches combining genome-wide screens with experimental evolution offer powerful methodologies for identifying and validating targets within the intrinsic resistome. Emerging strategies such as resistance hacking and resistance proofing leverage these insights to develop novel therapeutic interventions that constrain evolutionary pathways to resistance.

For researchers and drug development professionals, targeting the intrinsic resistome offers the promise of rejuvenating existing antibiotics against resistant pathogens while imposing evolutionary constraints that delay the emergence of new resistance mechanisms. As our understanding of the intricate relationships between constitutive and induced resistance deepens, so too will our capacity to develop innovative solutions to the antimicrobial resistance crisis.

The outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria constitutes a formidable and sophisticated barrier that is fundamental to the organism's intrinsic resistance to many antimicrobial agents [10] [11]. This membrane operates as a highly selective filter, permitting the influx of essential nutrients while effectively excluding a wide array of harmful substances, including antibiotics [10]. The permeability properties of this barrier are therefore a critical determinant of bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics, a significant challenge in modern healthcare as underscored by the World Health Organization, which identifies antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as a top global health threat [12] [13]. Understanding the molecular basis of the OM's barrier function, encompassing both lipid-mediated and porin-mediated pathways, is essential for researching resistance mechanisms and developing strategies to overcome them [10] [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the OM's role in antibiotic resistance, framed within the broader context of intrinsic resistance research, and is intended for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Structural Organization of the Gram-Negative Outer Membrane

The Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane is an asymmetric bilayer, a unique characteristic that is central to its barrier function [10] [11]. The inner leaflet is composed primarily of phospholipids (approximately 80% phosphatidylethanolamine, 15% phosphatidylglycerol, and 5% cardiolipin), while the outer leaflet is predominantly constituted by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [10]. This asymmetry is a key determinant of the membrane's low permeability.

A typical LPS molecule consists of three domains:

- Lipid A: A glucosamine-based phospholipid that anchors the LPS into the membrane.

- Core Oligosaccharide: A relatively short, branched carbohydrate chain.

- O-Antigen: A distal polysaccharide of variable length that contributes to serotype specificity [10].

The LPS layer is stabilized by strong lateral interactions between molecules and by divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) that cross-bridge the anionic groups on adjacent LPS molecules, creating a dense, tightly packed surface [10]. The resulting structure is markedly less fluid and more hydrophobic than a typical phospholipid bilayer, presenting a formidable physical and chemical barrier.

Embedded within this membrane is a diverse array of outer membrane proteins (Omps). Some of the most abundant, such as murein lipoprotein (Lpp) and OmpA, play crucial structural roles in maintaining membrane integrity and cell shape [10] [12]. Among the most functionally significant Omps for antibiotic permeability are the porins, which form water-filled channels for the passive diffusion of hydrophilic molecules [10] [14].

Pathways of Antibiotic Permeation and Associated Resistance Mechanisms

The Lipid Bilayer Pathway and Hydrophobic Antibiotic Resistance

Hydrophobic antibiotics, such as macrolides (e.g., erythromycin), rifamycins, novobiocin, and fusidic acid, traverse the OM by passive diffusion through the lipid bilayer itself [10]. The integrity of the LPS layer is therefore critical in determining resistance to these compounds.

Table 1: Antibiotics Utilizing Lipid-Mediated Uptake and Associated Resistance Modifications

| Antibiotic Class | Examples | Primary Resistance Mechanism | Molecular Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | LPS core truncation; cationic substitution on Lipid A | Altered membrane packing; reduced affinity for cationic agents |

| Rifamycins | Rifampin | Addition of 4-aminoarabinose to Lipid A | Reduction of net negative charge on LPS; tighter packing |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin, Kanamycin | Not fully detailed in search results; likely involves reduced uptake | Likely reduced passive diffusion through bilayer |

| Polymyxins | Polymyxin B, Colistin | Esterification of lipid A phosphates with 4-aminoarabinose or phosphoethanolamine [10] | Decreased negative charge; reduced initial binding and uptake |

Key Resistance Mechanisms:

- Deep Rough LPS Mutants: Mutants with truncated core oligosaccharides ("deep rough" or Re chemotypes) exhibit heightened sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics and detergents because their OM is destabilized. This destabilization can lead to the incorporation of phospholipid patches in the outer leaflet, which are significantly more permeable to lipophilic compounds [10].

- Cationic Substitutions: Polymyxin-resistant mutants of Salmonella typhimurium and E. coli modify their Lipid A by adding 4-aminoarabinose or phosphoethanolamine. This modification reduces the net negative charge of the LPS, decreasing electrostatic interactions with cationic antibiotics like polymyxin B and promoting a more closely packed LPS layer, thereby enhancing resistance [10].

- Permeabilizer Action: Compounds like polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN) and Tris/EDTA compete with divalent cations for LPS binding sites. Their action disrupts the LPS lattice, destabilizes the membrane, and creates pathways for hydrophobic antibiotics to penetrate, effectively sensitizing the bacteria [10].

The Porin Pathway and Hydrophilic Antibiotic Resistance

Hydrophilic antibiotics, including β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and some carbapenems, rely on porin channels to cross the OM [10] [15] [11]. Porins are β-barrel proteins that form trimeric, water-filled pores, facilitating the passive diffusion of small, hydrophilic molecules [14]. Resistance via this pathway often involves alterations that reduce porin-mediated influx.

Table 2: Major Porins and Their Role in Antibiotic Permeability and Resistance

| Porin | Structural Features | Role in Antibiotic Uptake | Documented Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| OmpF | Larger channel, cation-selective [15] | Major route for β-lactams, fluoroquinolones [15] | Downregulation; mutation of charged residues altering conductance [15] |

| OmpC | Smaller channel, cation-selective [15] | Uptake of β-lactams, fluoroquinolones [15] | Downregulation; mutation of charged periplasmic residues [15] |

| OmpA | Monomeric β-barrel, small channel [10] [12] | Diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules (e.g., β-lactams) [12] | Loss-of-function mutations; altered expression [12] |

| OmpW | Monomeric β-barrel | Implicated in drug transport [12] | Not fully detailed in search results |

| OmpX | Small β-barrel | May contribute to reduced permeability [12] | Overexpression linked to resistance [12] |

Key Resistance Mechanisms:

- Porin Loss or Downregulation: Complete loss or reduced expression of major porins like OmpF and OmpC is a common clinical resistance mechanism. This directly decreases the number of available channels for antibiotic entry [12] [11].

- Porin Mutation: Mutations can alter the physicochemical properties of the porin channel. For instance, mutations in charged residues on the periplasmic surface of OmpC can affect its conductance and ion selectivity, thereby modulating antibiotic permeability [15].

- Ionic Regulation of Porin Permeability: Recent research reveals that porin permeability is dynamically regulated by periplasmic ions. Acidification of the periplasm reduces porin conductance, while an increase in periplasmic K⁺ concentration enhances it. This metabolic control directly impacts antibiotic uptake, explaining, for example, increased ciprofloxacin resistance in bacteria catabolizing lipids [15].

Experimental Methodologies for Assessing Outer Membrane Permeability

Protocol 1: Quantifying Porin Permeability Using Fluorescent Tracers

This protocol utilizes fluorescent probes to measure porin-mediated uptake in real-time, adapted from single-cell imaging studies [15].

Objective: To measure the permeability of the outer membrane via porins in live E. coli cells using the fluorescent glucose analogue 2-NBDG. Principle: 2-NBDG is a hydrophilic molecule whose entry into the cell is mediated by porins. Its accumulation, quantified by fluorescence, serves as a proxy for porin permeability [15].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Wild-type and porin mutant (e.g., ΔompCΔompF) E. coli.

- Growth Medium: Appropriate broth (e.g., LB, M9).

- Fluorescent Tracer: 100 µM 2-NBDG (from a 20 mM stock in DMSO) [15].

- Ionophores: 50 µM Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP, protonophore) and 10 µM Valinomycin (K⁺ ionophore) to manipulate internal ion concentrations [15].

- Equipment: Microfluidic perfusion system for single-cell imaging or flow cytometer; fluorescence microscope; temperature-controlled incubator.

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Grow bacterial cultures to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) in the desired medium.

- Cell Loading: Wash and resuspend the cells in an appropriate buffer (e.g., potassium phosphate buffer) to an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.1.

- Ionophore Pre-treatment (Optional): Incubate aliquots of the cell suspension with CCCP or valinomycin for 10 minutes at 37°C with shaking.

- Tracer Uptake: Add 2-NBDG to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 10-100 µM. Immediately transfer the mixture to a microfluidic chamber for imaging or load into a flow cytometer.

- Real-Time Imaging/Acquisition:

- For single-cell imaging: Perfuse the cells with buffer containing 2-NBDG and acquire time-lapse fluorescence images every 30-60 seconds for 20-30 minutes using a 488 nm laser for excitation and a 525/50 nm emission filter [15].

- For flow cytometry: Take samples at specific time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30 min), wash, and resuspend in ice-cold buffer to stop uptake. Analyze fluorescence immediately using flow cytometry (FITC channel).

- Data Analysis: Quantify the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per cell over time. Compare the initial rates of uptake and the plateau MFI between wild-type and mutant strains or between treated and untreated conditions.

Protocol 2: Assessing LPS-Mediated Barrier Function via Sensitivity Assays

Objective: To evaluate the integrity of the LPS barrier by measuring bacterial sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics and detergents. Principle: Mutations that truncate the LPS core (rough mutants) destabilize the OM, increasing its permeability to hydrophobic compounds and thereby increasing susceptibility [10].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: Wild-type (smooth LPS) and isogenic deep-rough mutant (e.g., lpcA or rfaC mutant).

- Antimicrobials: Novobiocin (10 mg/mL stock), Erythromycin (10 mg/mL stock), Sodium deoxycholate (10% w/v stock).

- Growth Medium: Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB).

- Equipment: 96-well microtiter plates, plate reader, multichannel pipette.

Procedure:

- Culture Standardization: Grow overnight cultures of test strains and dilute to ~1 x 10⁶ CFU/mL in CAMHB.

- Broth Microdilution: In a 96-well plate, perform two-fold serial dilutions of the antimicrobials (e.g., novobiocin: 0.5-256 µg/mL; deoxycholate: 0.001%-1%).

- Inoculation: Add an equal volume of the standardized bacterial inoculum to each well. Include growth control (bacteria + medium) and sterility control (medium only).

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 16-20 hours without shaking.

- Analysis: Determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial that completely inhibits visible growth. A ≥4-fold decrease in the MIC of the rough mutant compared to the wild-type strain indicates a compromised LPS barrier function.

Regulatory Pathways and Metabolic Control of Porin Permeability

Recent research has unveiled a sophisticated regulatory network where bacterial metabolism dynamically controls porin permeability via changes in periplasmic ion concentrations [15]. This represents a novel, rapid response mechanism that complements traditional transcriptional regulation.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Control of Porin Permeability. This diagram illustrates how bacterial metabolic states influence periplasmic ion concentrations (H⁺ and K⁺) to dynamically regulate porin conductance, thereby balancing nutrient uptake with energy conservation and impacting antibiotic resistance [15].

Genetic Regulation of Porin Expression

Beyond immediate metabolic control, porin expression is regulated at the transcriptional level. Key regulatory systems include:

- SmpB Protein: In Aeromonas veronii, the SmpB protein binds to specific regions of the OmpA promoter, acting as a positive regulator of ompA expression, particularly during the stationary phase [12].

- Anti-Repressors: In A. baumannii, the A1S_0316 protein acts as an anti-repressor by binding the OmpA promoter with higher affinity than the global repressor H-NS, preventing H-NS-mediated repression [12].

- Sigma Factor Circuits: In Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, peptidoglycan stress triggered by the loss of OmpA-peptidoglycan interaction upregulates sigma factor σP, leading to a cascade that ultimately modulates β-lactamase expression and antibiotic resistance [12].

Diagram 2: Genetic Regulation of Resistance. This diagram outlines the sigma(P)-NagA regulatory circuit that connects outer membrane integrity to β-lactamase expression, illustrating a multi-layer resistance response [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Outer Membrane Permeability

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-NBDG | Fluorescent Tracer | Porin-permeable glucose analog for tracking OM permeability [15] | Quantifying real-time porin-mediated uptake using flow cytometry or microscopy [15] |

| Bocillin FL | Fluorescent Tracer | Penicillin-based fluorescent probe for β-lactam uptake studies [15] | Visualizing and quantifying penetration of β-lactam-like molecules [15] |

| Ionophores (CCCP, Valinomycin) | Chemical Modulator | Disrupts H⁺ or K⁺ gradients across membranes [15] | Manipulating periplasmic ion concentrations to study their effect on porin conductance [15] |

| pHuji & pHluorin | Genetically Encoded Sensor | Fluorescent proteins for ratiometric measurement of periplasmic and cytoplasmic pH, respectively [15] | Real-time monitoring of pH changes in specific cellular compartments in single cells [15] |

| GINKO1 & GINKO2 | Genetically Encoded Sensor | Fluorescent biosensors for monitoring cytoplasmic and periplasmic K⁺ levels [15] | Tracking dynamic changes in potassium ion concentration in response to metabolic shifts [15] |

| ArchT | Optogenetic Tool | Light-activated proton pump expressed in the inner membrane [15] | Precisely and reversibly acidifying the periplasm to directly test its effect on porin permeability [15] |

| Microfluidic Perfusion System | Equipment | Enables high-resolution imaging of single cells under controlled conditions [15] | Conducting long-term, real-time imaging of ion fluctuations and tracer uptake in individual bacteria [15] |

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is a dynamic and complex barrier whose permeability is a cornerstone of intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Its function is determined by the intricate interplay between the LPS layer and a diverse set of porin channels. Resistance arises not only from classic genetic mutations that alter the abundance or structure of these components but also from a newly appreciated layer of metabolic regulation that dynamically controls porin permeability in response to the cell's energetic state. Overcoming this barrier requires a deep and nuanced understanding of these pathways. Future research and drug development must account for this complexity, potentially targeting the regulatory systems themselves (e.g., Kch channel) or designing novel agents that can bypass or disrupt the barrier, thereby revitalizing our arsenal in the fight against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections.

Constitutive efflux pumps represent a fundamental component of intrinsic antibiotic resistance in bacteria, enabling survival amid antimicrobial agents from the earliest exposure. These membrane-associated transport proteins, expressed at baseline levels across bacterial species, function as frontline defenses by actively extruding toxic compounds from bacterial cells. This whitepaper examines the structural classification, regulatory mechanisms, and physiological roles of constitutively expressed efflux systems, with particular focus on their clinical significance in multidrug-resistant pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The document further details experimental methodologies for investigating efflux pump activity and provides a strategic framework for developing efflux pump inhibitors as therapeutic adjuvants. Within the broader context of intrinsic resistance mechanisms research, understanding these constitutive systems provides critical insights for overcoming treatment failures and designing novel antimicrobial strategies.

Constitutive efflux pumps are transport proteins consistently expressed at baseline levels in bacterial cells, providing inherent protection against antimicrobial compounds without requiring prior exposure or genetic adaptation [16] [17]. Unlike inducible resistance mechanisms that activate only under antibiotic pressure, these pumps maintain a constant vigilance system, contributing significantly to what is termed intrinsic resistance - the innate ability of a bacterial species to resist antibiotic classes due to its core genomic makeup [18]. This fundamental defense mechanism predates clinical antibiotic use, suggesting these pumps evolved primarily for physiological functions beyond antibiotic extrusion [16] [17].

The clinical significance of constitutive efflux extends beyond providing baseline protection. When overexpressed, often through mutations in regulatory genes, these same pumps can confer elevated multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotypes in clinical isolates, expelling chemically diverse antibiotics and contributing to treatment failures [16] [17] [19]. The Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family efflux pumps in Gram-negative pathogens represent particularly effective constitutive systems due to their tripartite structure that spans both inner and outer membranes, allowing direct extrusion of antibiotics to the extracellular environment [16] [19]. For opportunistic pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which possess numerous chromosomal efflux pump genes, this intrinsic resistance mechanism presents a major therapeutic challenge, especially in healthcare settings where carbapenem resistance rates continue to rise globally [16].

Classification and Mechanisms of Major Efflux Pump Families

Bacterial efflux pumps are categorized into superfamilies based on their structural characteristics, energy coupling mechanisms, and phylogenetic relationships. The table below summarizes the key features of major efflux pump families with constitutive expression profiles.

Table 1: Major Families of Bacterial Efflux Pumps with Constitutive Expression

| Family | Energy Source | Typical Structure | Primary Substrates | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) | Proton motive force | Tripartite complex (inner membrane transporter, periplasmic adapter, outer membrane factor) | Broad spectrum: β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, macrolides, chloramphenicol, dyes, detergents | AdeABC, AdeIJK in A. baumannii; AcrAB-TolC in E. coli; MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa |

| MFS (Major Facilitator Superfamily) | Proton motive force | Single component (12-14 transmembrane segments) | Tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, β-lactams | TetA, Tet(B) in A. baumannii; NorA in S. aureus |

| MATE (Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion) | Proton/sodium motive force | Single component (12 transmembrane segments) | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, dyes | AbeM in A. baumannii |

| SMR (Small Multidrug Resistance) | Proton motive force | Small tetramer (4 transmembrane segments) | Disinfectants, dyes, fluoroquinolones | AbeS in A. baumannii; EmrE in E. coli |

| ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) | ATP hydrolysis | Two transmembrane domains + two nucleotide binding domains | Aminoglycosides, macrolides, glycopeptides | MsbA in E. coli |

| PACE (Proteobacterial Antimicrobial Compound Efflux) | Proton motive force | Four transmembrane segments | Chlorhexidine, acriflavine, propanol | AceI in A. baumannii |

The RND family represents the most clinically significant constitutive efflux system in Gram-negative pathogens due to its broad substrate profile and efficient extrusion mechanism [16] [19]. These pumps form sophisticated tripartite architectures that traverse the entire cell envelope: an inner membrane RND transporter (e.g., AdeB, AdeI), a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP, e.g., AdeA, AdeJ), and an outer membrane factor (OMF, e.g., AdeC, AdeK) [16]. This continuous conduit allows direct antibiotic extrusion from the cell interior or periplasm to the external environment, effectively reducing intracellular drug concentrations below inhibitory levels [16] [19].

The operational mechanism involves a proton antiport process where the influx of protons down their electrochemical gradient provides energy for substrate extrusion [16]. RND transporters typically contain 12 transmembrane segments with two large loops between transmembrane segments 1-2 and 7-8, forming proximal and distal binding pockets that accommodate structurally diverse compounds [16] [19]. These pumps cycle through loose, tight, and open conformations to capture and expel substrates, with some evidence suggesting they can directly efflux compounds from the cytoplasm despite primarily functioning in the periplasm [16].

Diagram 1: RND family efflux pump structure and mechanism

Regulation and Expression of Efflux Pumps

Constitutive efflux pump expression is governed by sophisticated regulatory networks that maintain baseline levels while allowing adaptive responses to environmental stresses. These systems integrate local regulators specific to individual pump operons with global regulators that coordinate multiple cellular responses [17].

In Acinetobacter baumannii, the clinically significant AdeABC pump is regulated by the AdeRS two-component system, where AdeS acts as a sensor kinase and AdeR as a response regulator [16]. Under normal conditions, this system maintains modest expression levels sufficient for intrinsic resistance functions. Mutations in adeRS, particularly in AdeS, can lead to constitutive overexpression, resulting in significantly enhanced multidrug resistance phenotypes in clinical isolates [16]. Similarly, the AdeIJK pump, which demonstrates substantial basal activity even without induction, is regulated by the AdeN repressor and the BaeSR two-component system [16]. The AdeFGH system is controlled by the AdeL LysR-type transcriptional regulator, with additional modulation by quorum sensing molecules such as the abaI autoinducer [16].

The evolutionary conservation of efflux pumps across bacterial species indicates they serve fundamental physiological roles beyond antibiotic resistance [17]. Research suggests constitutive efflux activity contributes to:

- Virulence modulation: Export of virulence factors and toxins

- Stress response: Protection against oxidative stress, bile salts, and host-derived antimicrobial peptides

- Cell-to-cell communication: Transport of quorum sensing molecules and intercellular signals

- Metabolic waste removal: Elimination of toxic metabolic byproducts

- Homeostasis maintenance: Regulation of internal pH and ion concentrations [16] [17] [19]

The tight integration of efflux pump regulation with stress response pathways explains why antibiotic exposure often selects for mutants with constitutively overexpressed pumps, as these adaptations provide simultaneous resistance to multiple drug classes while maintaining bacterial fitness in hostile environments [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Efflux Pump Investigation

Efflux Pump Activity Assays

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination with EPIs

- Principle: Compare MIC values of antibiotics with and without efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) to detect efflux-mediated resistance [20] [21]

- Protocol:

- Prepare serial dilutions of test antibiotic in Mueller-Hinton broth

- Inoculate with standardized bacterial suspension (~5×10^5 CFU/mL)

- Add subinhibitory concentrations of EPI (e.g., Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone, or plant-derived inhibitors like berberine or curcumin) [21]

- Incubate at 35°C for 16-20 hours

- Determine MIC as lowest antibiotic concentration inhibiting visible growth

- Interpret results: ≥4-fold MIC reduction with EPI indicates significant efflux contribution [20] [21]

Ethidium Bromide Accumulation and Efflux Assays

- Principle: Measure fluorescence changes as ethidium bromide (EtBr) accumulates in cells or is actively extruded [16]

- Protocol:

- Grow bacterial culture to mid-logarithmic phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5)

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Resuspend in PBS with glucose (0.2% w/v) as energy source

- Load cells with EtBr (0.5-2 μg/mL) and incubate 30 minutes

- Measure baseline fluorescence (excitation 530 nm, emission 600 nm)

- Add energy inhibitor (e.g., carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone) or EPI

- Monitor fluorescence increase (accumulation) or decrease (efflux) over time

- Calculate initial efflux rates from fluorescence decay curves [16]

Gene Expression Analysis

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

- Principle: Quantify efflux pump mRNA levels to assess constitutive expression and regulatory responses [22]

- Protocol:

- Extract total RNA from bacterial cultures using guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method

- Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random hexamers

- Perform qPCR with gene-specific primers for target efflux pumps (e.g., adeB, adeJ, adeG)

- Include housekeeping gene controls (e.g., rpoB, gyrB)

- Calculate relative expression using 2^(-ΔΔCt) method [22]

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq)

- Principle: Comprehensive transcriptome profiling to identify differentially expressed genes in efflux pump mutants [23]

- Protocol:

- Extract high-quality total RNA (RIN > 8.0)

- Deplete ribosomal RNA using target-specific probes

- Prepare sequencing libraries with polyA selection or rRNA depletion

- Sequence on high-throughput platform (Illumina)

- Map reads to reference genome and quantify transcript abundance

- Identify differentially expressed genes with statistical significance (FDR < 0.05) [23]

Genetic Approaches for Functional Characterization

Gene Knockout Construction

- Principle: Create isogenic mutants to directly assess efflux pump contribution to resistance [23]

- Protocol:

- Amplify upstream and downstream flanking regions of target gene

- Clone fragments into suicide vector with selectable marker

- Introduce plasmid into target strain via conjugation or transformation

- Select for single-crossover integrants using appropriate antibiotics

- Counter-select for double-crossover events yielding gene deletions

- Verify mutants by PCR and sequencing [23]

Complementation Studies

- Principle: Restore gene function in mutants to confirm phenotype linkage [23]

- Protocol:

- Amplify complete target gene with native promoter

- Clone into stable expression vector

- Introduce recombinant plasmid into knockout mutant

- Verify complementation by restored gene expression and phenotypic reversal [23]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Efflux Pump Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN), carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), verapamil, reserpine | Functional characterization of efflux activity, EPI development | Varying specificity for different pump families; potential cytotoxicity at high concentrations |

| Fluorescent Substrates | Ethidium bromide, Hoechst 33342, rhodamine 6G, Nile red | Real-time efflux kinetics, pump activity quantification | Differential substrate preferences among pumps; fluorescence properties affect detection sensitivity |

| Plant-Derived EPIs | Berberine, curcumin, palmatine, piperine, capsaicin | Natural product screening, combination therapy development | Dual antibacterial and EPI activity; potential Sortase A inhibition; lower cytotoxicity profiles |

| Gene Expression Tools | RT-PCR primers for efflux pump genes, RNA extraction kits, RNA-seq library prep kits | Expression profiling, regulatory mechanism studies | Primer specificity critical for homologous pump genes; RNA quality affects results |

| Antibiotic Substrates | Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, β-lactams | Susceptibility testing, substrate range determination | Use clinical isolates with defined resistance profiles; include EPI controls |

| Bacterial Strains | ATCC type strains, clinical isolates with characterized efflux mutations, isogenic knockout mutants | Mechanistic studies, comparative analyses | Verify genetic background; include appropriate controls for mutant studies |

Connection to Virulence and Pathogenesis

Emerging evidence demonstrates that constitutive efflux pumps function at the intersection of antibiotic resistance and bacterial virulence, influencing host-pathogen interactions through multiple mechanisms [17] [23]. Research on Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals that mutations inactivating the MexEF-OprN efflux pump unexpectedly increase virulence during infection through enhanced quorum sensing (QS) signaling [23]. These efflux pump mutants exhibit elevated production of QS-regulated virulence factors including elastase and rhamnolipids, leading to more severe infection outcomes in murine models [23].

Efflux pumps also contribute to virulence through:

- Biofilm formation: Export of biofilm matrix components and signaling molecules

- Stress adaptation: Protection against host immune effectors like antimicrobial peptides

- Toxin secretion: Extrusion of cytolytic compounds and exoenzymes

- Metabolic fitness: Maintenance of cellular homeostasis during infection [17] [19]

The relationship between efflux and virulence displays pathogen-specific characteristics. In Salmonella enterica, the AcrAB-TolC system facilitates adhesion and invasion of host cells, while in Escherichia coli, efflux pumps contribute to colonization competence [19]. This functional integration suggests that therapeutic targeting of efflux pumps may simultaneously restore antibiotic susceptibility and attenuate virulence, providing dual therapeutic benefits [17] [23].

Diagram 2: Efflux pump modulation of virulence and resistance

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Directions

Efflux Pump Inhibitor Development

The strategic inhibition of constitutive efflux pumps represents a promising approach to revitalizing existing antibiotics and overcoming multidrug resistance [16] [20] [21]. Current EPI development strategies include:

Natural Product Screening Plant-derived compounds including berberine, curcumin, and palmatine demonstrate dual antibacterial and efflux inhibition activity, potentially acting as both antimicrobials and resistance breakers [21]. These compounds exhibit effects on bacterial growth kinetics and morphology while inhibiting efflux function, making them attractive candidates for combination therapies [21].

Synthetic Chemistry Approaches Structure-based drug design targeting conserved regions of efflux pumps, particularly the binding pockets and proton translocation domains, enables development of potent inhibitors with improved pharmacological properties [16] [19]. Recent efforts have identified specific binding boxes in the periplasmic adapter proteins of RND pumps as promising therapeutic targets [19].

Dual-Target Inhibitors Compounds capable of inhibiting both bacterial efflux pumps and mammalian MDR transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein) offer potential for concurrent treatment of infectious diseases and cancer, though selectivity considerations remain challenging [20].

Technological Innovations

Advanced methodologies are enhancing EPI discovery and development:

Machine Learning Applications Computational approaches analyze chemical libraries to predict EPI activity, identify structural features associated with efflux inhibition, and optimize lead compounds, accelerating the discovery pipeline [19].

Structural Biology Techniques Cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography provide high-resolution structures of efflux pumps, enabling rational drug design through detailed understanding of substrate binding and transport mechanisms [16] [19].

Chemical Informatics Database development systematizes known EPI structures and activities, facilitating quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and virtual screening of compound libraries [20] [19].

The continued investigation of constitutive efflux pumps remains essential for addressing the growing threat of multidrug-resistant infections. By integrating fundamental knowledge of pump structure-function relationships with innovative therapeutic approaches, researchers can develop effective strategies to counteract this primordial bacterial defense mechanism and preserve the efficacy of existing antimicrobial agents.

Antimicrobial resistance represents one of the most pressing challenges to modern healthcare, contributing significantly to global morbidity and mortality [18]. While acquired resistance through horizontal gene transfer often dominates clinical concerns, intrinsic resistance mechanisms encoded by chromosomal genes provide a fundamental "enzymatic armor" that enables bacterial survival against antimicrobial agents. This innate resistance predates antibiotic chemotherapy and is present in all bacterial species [24].

The concept of the "resistome" encompasses all antibiotic resistance genes, both intrinsic and acquired, within bacterial populations. Within this framework, chromosomal genes encoding enzymatic inactivation systems represent a sophisticated first line of defense that does not require external genetic acquisition [25]. These intrinsic mechanisms are particularly problematic in clinical settings as they are ubiquitous within specific bacterial species and not dependent on the selective pressures that drive the spread of acquired resistance.

This review examines the chromosomal gene-encoded enzymatic systems that confer intrinsic antibiotic resistance, with a focus on their biochemical mechanisms, genetic regulation, and experimental characterization. Understanding these native resistance elements is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies to overcome treatment failures and combat the escalating antimicrobial resistance crisis.

Core Mechanisms of Enzymatic Antibiotic Inactivation

Bacteria employ several sophisticated enzymatic strategies to neutralize antibiotics, including modification of the drug molecule itself, target site alterations, and protection of vulnerable cellular components. The major enzymatic mechanisms encoded by chromosomal genes include:

Antibiotic-Modifying Enzymes

Chromosomal genes encode various enzymes that chemically modify antibiotics, rendering them ineffective against their cellular targets. These modifications include:

- Hydrolytic inactivation: Enzymes such as β-lactamases cleave critical bonds in antibiotic structures. The AmpC β-lactamase, chromosomally encoded in many Gram-negative bacteria, hydrolyzes the β-lactam ring of penicillins and cephalosporins [18].

- Group transfer reactions: Transferases catalyze the covalent attachment of chemical groups to antibiotics. This includes aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes such as acetyltransferases, phosphotransferases, and nucleotidyltransferases [26].

- Redox-based inactivation: Some enzymes catalyze redox reactions that alter essential components of antibiotic molecules.

Target Modification Systems

Beyond direct antibiotic modification, bacteria utilize enzymatic systems to alter the molecular targets of antibiotics:

- Enzyme mutation and evolution: Chromosomal genes encoding target proteins can mutate to reduce antibiotic binding affinity while maintaining cellular function. Mutations in genes for DNA gyrase (gyrA, gyrB) and topoisomerase IV (parC, parE) confer resistance to quinolones by altering the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) [25].

- Target protection proteins: Some chromosomal genes encode proteins that physically protect antibiotic targets without modifying them, such as the Qnr proteins that protect DNA gyrase from quinolones [26].

Efflux Pump Systems

While not direct inactivation mechanisms, efflux pumps function as enzymatic armor by reducing intracellular antibiotic concentrations. Chromosomal multidrug efflux systems like AcrAB-TolC in Enterobacteriaceae provide intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotic classes [27] [18].

Table 1: Major Chromosomal Enzymatic Systems for Antibiotic Inactivation

| Enzyme Class | Representative Enzymes | Antibiotic Targets | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactamases | AmpC, SHV | β-Lactams | Hydrolysis of β-lactam ring |

| Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes | AAC, APH, ANT | Aminoglycosides | Acetylation, phosphorylation, adenylation |

| Target-Altering Enzymes | Mutated PBP2a, Altered DNA gyrase | β-Lactams, Quinolones | Reduced drug-target binding affinity |

| Drug-Modifying Enzymes | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase | Chloramphenicol | Acetylation |

| Ribosomal Methyltransferases | Erm family | Macrolides, Lincosamides, Streptogramins | Methylation of 23S rRNA |

Key Chromosomal Resistance Genes and Their Regulation

mecA/mecC-Mediated Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus

The mecA gene represents a paradigm of chromosomal antibiotic resistance, encoding the alternative penicillin-binding protein PBP2a in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [28]. This protein possesses low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics due to structural differences in its active site, allowing it to maintain bacterial cell wall synthesis when native PBPs are inhibited [28] [25].

The mecA gene is part of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), a mobile genetic element that integrates into the bacterial chromosome [28]. Its expression is regulated by the mecA regulatory system (mecR1-mecI) and the β-lactamase regulatory system (blaR1-blaI), which respond to the presence of β-lactam antibiotics [28]. A homologous gene, mecC, has also been identified and encodes PBP2c with similar function [28].

Auxiliary Factor Genes (fem Factors)

The expression of methicillin resistance in MRSA requires the coordinated activity of auxiliary factors encoded by fem (factor essential for methicillin resistance) genes [28]. These chromosomal genes, including femA, femB, femC, femD, femE, and femF, participate in cell wall biosynthesis and synergistically regulate resistance levels without directly affecting PBP2a production [28].

Insertional inactivation of femA and femB results in complete loss of methicillin resistance, demonstrating their essential role in the resistance phenotype [28]. These genes are dispersed throughout the bacterial chromosome and represent potential targets for novel anti-MRSA therapies aimed at disrupting the native enzymatic armor.

Enzymatic Targets and Modifications

Chromosomal genes encoding antibiotic targets can develop mutations that confer resistance while maintaining essential cellular functions:

- RNA polymerase mutations: Mutations in the rpoB gene, particularly in codons 507-533, alter the β-subunit of RNA polymerase and confer resistance to rifamycins [25].

- DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutations: Mutations in gyrA/gyrB and parC/parE genes reduce binding affinity for fluoroquinolones while maintaining enzymatic function [25].

- Ribosomal RNA methyltransferases: Chromosomal erm genes encode methyltransferases that modify 23S rRNA, preventing binding of macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins [18].

Table 2: Experimentally Characterized Chromosomal Resistance Genes

| Gene | Bacterial Species | Encoded Enzyme/Protein | Resistance Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| mecA | Staphylococcus aureus | PBP2a | β-lactams |

| mecC | Staphylococcus aureus | PBP2c | β-lactams |

| femA | Staphylococcus aureus | Fem factor A | β-lactams (auxiliary) |

| blaA | Bacteroides fragilis | β-lactamase | β-lactams |

| ampC | Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas | β-lactamase | β-lactams |

| vanA | Enterococcus faecium | D-Ala-D-Lac ligase | Glycopeptides |

| erm(B) | Various Gram-positives | rRNA methyltransferase | Macrolides |

| aac(6')-Ib | Various Gram-negatives | Aminoglycoside acetyltransferase | Aminoglycosides |

| gyrA | Multiple species | DNA gyrase subunit A | Quinolones |

| rpoB | Multiple species | RNA polymerase subunit B | Rifamycins |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Gene Inactivation and Functional Analysis

Understanding chromosomal resistance genes requires robust methods for genetic manipulation. The one-step inactivation method using PCR products provides an efficient approach for disrupting chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli and other bacteria [29]. This technique employs the phage λ Red recombinase system to facilitate homologous recombination between the chromosome and PCR products containing selectable markers flanked by homology regions [29].

Protocol: One-Step Chromosomal Gene Inactivation

- Amplify a selectable antibiotic resistance cassette (e.g., kanamycin or chloramphenicol) using primers with 36-50 nucleotide extensions homologous to the target gene.

- Introduce the PCR product into bacteria expressing the λ Red recombinase system (encoded on a temperature-sensitive plasmid).

- Select for transformants on appropriate antibiotic-containing media.

- Verify gene disruption by PCR analysis using primers flanking the target region and internal cassette primers.

- Eliminate the antibiotic resistance cassette using FLP recombinase acting on FRT sites if desired [29].

This method allows for systematic functional analysis of chromosomal genes suspected to contribute to intrinsic resistance, including fem factors and regulatory elements.

Experimental Evolution for Studying Resistance Emergence

Experimental evolution approaches allow direct observation of how chromosomal genes contribute to resistance development under selective pressure:

Protocol: Experimental Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance

- Initiate multiple independent bacterial lineages in subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics.

- Propagate cultures through serial passages (typically 28+ days) with increasing antibiotic concentrations.

- Monitor population dynamics through regular sampling and determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs).

- Identify genetic changes through whole-genome sequencing of isolates from different time points.

- Validate causal mutations by reintroducing specific changes into naive backgrounds [30].

This approach has demonstrated how chromosomal genes facilitate adaptation, such as the integration of carbapenemase genes into the chromosome of E. coli ST38 under antibiotic selection [30].

Molecular Characterization of Resistance Mechanisms

Protocol: Characterization of β-Lactam Resistance Mechanisms

- Determine MICs to various β-lactams using broth microdilution according to CLSI guidelines.

- Detect PBP2a production using immunoassays or latex agglutination tests.

- Amplify mecA and mecC genes by PCR with specific primers.

- Assess expression levels of mecA and regulatory genes using quantitative RT-PCR.

- Evaluate the impact of auxiliary factors through gene inactivation and complementation studies [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Chromosomal Resistance Genes

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Inactivation Systems | λ Red recombinase system [29], FLP/FRT system | Targeted gene disruption | Temperature-sensitive replicon, high efficiency |

| Selective Markers | Kanamycin resistance (kan), Chloramphenicol resistance (cat) | Selection of recombinants | FRT-flanked for excision, various resistance profiles |

| Expression Vectors | pANTSγ, pINT-ts, pBAD18 | Complementation, heterologous expression | Inducible promoters, temperature-sensitive replication |

| PCR Enzymes | Taq polymerase, Pfu polymerase | Amplification of disruption cassettes | High fidelity, proofreading activity |

| Antibiotics for Selection | Ampicillin, Kanamycin, Chloramphenicol | Selective pressure, mutant selection | Various concentrations for different bacterial species |

| Bacterial Strains | E. coli BW25113, S. aureus strains with SCCmec | Host for genetic manipulations | Defined genetic background, recA+ for recombination |

| Sequencing Primers | Custom oligonucleotides with homology extensions | Verification of constructs | 36-50 nt homology regions, verification primers |

| Growth Media | SOB, SOC media | Transformation efficiency | High transformation efficiency, recovery after electroporation |

Visualization of Key Concepts

PBP2a-Mediated Resistance Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for Resistance Gene Analysis

Chromosomal genes encoding enzymatic armor represent a fundamental component of bacterial defense systems against antibiotics. The mecA/mecC-mediated production of PBP2a in MRSA exemplifies how native genetic elements can be co-opted or modified to provide robust resistance mechanisms. Together with auxiliary factors and regulatory systems, these chromosomal genes create sophisticated networks that enable bacterial survival under antimicrobial pressure.

Understanding these intrinsic resistance mechanisms at molecular, genetic, and biochemical levels provides critical insights for developing next-generation antimicrobial agents and combination therapies that can bypass or inhibit these native defense systems. As the antimicrobial resistance crisis continues to escalate, decoding the complexities of chromosomal resistance genes will be essential for preserving the efficacy of existing antibiotics and informing the design of novel therapeutic approaches.

Intrinsic resistance is the innate, chromosomally encoded ability of a bacterial species to withstand the action of a particular antibiotic class without prior exposure or horizontal gene transfer [31] [32]. This phenomenon is a cornerstone of the natural phenotype of susceptibility in bacteria and is distinct from acquired resistance. The World Health Organization (WHO) has prioritized antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens into critical, high, and medium priority groups to guide research and development of new strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [33]. Understanding the intrinsic resistome—the full complement of chromosomal elements that contribute to intrinsic resistance—is vital for developing novel therapeutic interventions and is the focus of this technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals [31].

The clinical and ecological impact of intrinsic resistance is profound. Bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths in 2019 and contributed to nearly 5 million more [34]. The WHO's 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (WHO BPPL) updates the prioritization of antibiotic-resistant pathogens to address these evolving challenges, categorizing 24 pathogens across 15 families [33]. This guide delves into the intrinsic resistance mechanisms of the most critical pathogens on this list, providing structured data and methodologies to advance research in this field.

The WHO Critical Priority Pathogens List

The 2024 WHO BPPL is a critical tool in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance [33]. Building on the 2017 edition, the list refines the prioritization of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research and public health interventions. The pathogens categorized as critical priority are of utmost concern due to their global impact in terms of disease burden, transmissibility, treatability, and gaps in the R&D pipeline for new effective treatments [33] [35]. These bacteria are often multidrug-resistant, posing severe threats in healthcare settings.

The critical priority group primarily encompasses Gram-negative bacteria resistant to last-resort antibiotics, including carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa [33]. Also included are Enterobacteriaceae—such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter spp.—that are resistant to both third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems [35]. These pathogens are frequently associated with hospital-acquired infections like pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in critically ill patients requiring medical devices such as ventilators and blood catheters [35].

Table 1: WHO Critical Priority Bacterial Pathogens and Key Intrinsic Resistances

| Bacterial Pathogen | Family | Key Intrinsic Resistance Profiles [32] [35] |

|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Moraxellaceae | Intrinsic resistance to many beta-lactams (e.g., ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, 1st/2nd gen. cephalosporins), aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, macrolides. Often displays multi- or pan-drug resistance. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pseudomonadaceae | Intrinsic resistance to many beta-lactams (e.g., ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, 1st/2nd gen. cephalosporins, many tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. |

| Enterobacteriaceae (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp.) | Enterobacteriaceae | K. pneumoniae: Intrinsic resistance to ampicillin. E. coli: Intrinsic resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, some 1st-gen. cephalosporins. Enterobacter spp.: Intrinsic resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, 1st-gen. cephalosporins. |

Core Mechanisms of Intrinsic Resistance

The intrinsic resistance phenotype is an emergent property resulting from the concerted action of several chromosomal elements [31]. The primary mechanisms include reduced antibiotic permeability, efflux pump activity, and enzymatic inactivation.

Figure 1: Core mechanisms conferring intrinsic antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens.

Impermeability and Efflux Pumps

The synergy between low outer membrane permeability and broad-spectrum efflux pumps is a fundamental mechanism of intrinsic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria, particularly in critical pathogens like P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii [31]. The Gram-negative outer membrane acts as a formidable barrier, limiting the penetration of many antibiotic classes, including beta-lactams, macrolides, and glycopeptides [32]. This innate impermeability is powerfully complemented by multidrug efflux pumps.

These efflux systems, which often have a wide range of substrates, actively transport antibiotics out of the cell, preventing intracellular accumulation to effective concentrations [35]. In A. baumannii, for instance, several efflux pump families—including the Resistance Nodulation Division (RND) superfamily (e.g., AdeABC), the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS), and the Small Multidrug Resistance (SMR) family—contribute to resistance against aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and beta-lactams [35]. The AdeABC pump, in particular, has been linked to tigecycline resistance [35]. Similarly, in E. coli, the AcrAB efflux system is a major contributor to its intrinsic resistance to macrolides and other drug classes [31].

Enzymatic Inactivation and Target Modification

The production of chromosomally encoded antibiotic-inactivating enzymes is another key strategy. Many bacteria possess innate genes for enzymes that chemically modify or degrade antibiotics [31]. A classic example is the intrinsic production of various β-lactamases, such as the AmpC cephalosporinase found in A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, which hydrolyzes and inactivates a broad range of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics [35].

Furthermore, intrinsic resistance can arise from the lack of a specific target or structural modifications to the target site that reduce antibiotic binding. For example, the absence of a cell wall in Mycoplasma pneumoniae makes it intrinsically resistant to all beta-lactam antibiotics, which target cell wall synthesis [32]. Enterococcus species exhibit intrinsic low-level resistance to aminoglycosides due to impaired drug uptake, though this can be overcome by synergism with cell-wall active agents [32].

Experimental Analysis of the Intrinsic Resistome

Elucidating the components of the intrinsic resistome requires high-throughput, genome-wide approaches. These methodologies allow for the systematic identification of genes that, when inactivated or overexpressed, alter the bacterial susceptibility profile.

Genome-Wide Mutagenesis and Phenotypic Screening

The most direct method for analyzing the intrinsic resistome involves screening comprehensive gene knockout or insertion libraries (e.g., transposon mutant libraries) [31]. This approach determines the contribution of each individual gene to the baseline antibiotic susceptibility of a bacterium. Mutants are arrayed in multi-well plates and screened for changes in the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) to a panel of antibiotics. Genes whose inactivation leads to a decreased MIC (hypersusceptibility) are classified as components of the intrinsic resistome, as they are necessary for the wild-type level of resistance [31].

Figure 2: Workflow for identifying intrinsic resistome genes via mutant library screening.

Resistance Induction Through In Vitro Selection Pressures

Experimental induction of resistance under sustained laboratory selection pressure can reveal potential pathways for resistance development and identify genes that may become relevant in a clinical setting over time. This involves serially passaging bacteria in the presence of sub-inhibitory and progressively increasing concentrations of an antimicrobial agent [36].

For example, a 2016 study successfully induced resistance to the antimicrobial peptide Tachyplesin I in Aeromonas hydrophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli through two methods: long-term exposure to escalating drug concentrations and UV mutagenesis followed by selection on peptide-containing plates [36]. The study noted that resistance was stable and observed cross-resistance to other antimicrobials in some mutants, highlighting the potential risks associated with the clinical use of even potent antimicrobial peptides [36].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Intrinsic Resistance Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function & Application in Resistance Research |

|---|---|

| Transposon Mutant Library | Genome-wide collection of random gene knockouts for identifying genes that confer hypersusceptibility when inactivated. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 / RNAi Libraries | Functional genomics tools for targeted or systematic gene knockout/knockdown to validate resistance genes. |

| Standard Broth Microdilution | CLSI-standardized method for determining Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), the gold standard for susceptibility testing. |

| Conditional Expression Plasmids | For controlled overexpression (gain-of-function) of candidate genes to confirm their role in elevating MIC. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | To quantify intracellular antibiotic accumulation and assess efflux pump activity or membrane permeability. |

Correlative Genomics and Transcriptomics

Leveraging large-scale pharmacogenomic datasets is a powerful computational and experimental approach. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and drug sensitivity data from hundreds of bacterial isolates or cell lines, researchers can identify correlations between basal gene expression levels and antibiotic potency [37]. This method hinges on the hypothesis that the overexpression of an intrinsic resistance driver (e.g., an efflux pump component) is inversely correlated with drug sensitivity.

A key advancement in this area involves applying stringent filters to these correlations to distinguish specific, mechanistic drivers from general, non-specific correlates. This includes removing genes that are mere proxies for co-expressed gene networks and filtering for gene-drug relationships with high selectivity, thereby excluding genes that simply mark tissue lineage or general metabolic state [37]. Candidate genes identified through this bioinformatic analysis must then be functionally validated through gene knockout (to enhance susceptibility) or overexpression (to confer resistance) in model bacterial strains [37].

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite advances in understanding the intrinsic resistome, significant challenges remain. A major hurdle is the distinction between genes that specifically confer resistance and those that indirectly affect susceptibility through broad impacts on cellular fitness and metabolism [31] [37]. Furthermore, the interplay between intrinsic resistance mechanisms and the acquisition of mobile genetic elements carrying resistance genes is complex and not fully elucidated.

Future research should prioritize:

- Defining the Resistome-Phenotype Link: Systematically linking specific genetic elements within the intrinsic resistome to measurable phenotypic resistance outcomes across different genetic backgrounds and environmental conditions.

- Exploring Inhibitors of Intrinsic Resistance: Targeting components of the intrinsic resistome, such as efflux pumps or regulatory proteins, to re-sensitize bacteria to existing antibiotics [31]. This approach could revitalize older drugs and enhance the efficacy of new ones.

- Integrating Multi-Omics Data: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to build a holistic model of how intrinsic resistance emerges from networked cellular systems, rather than from isolated genes.

Overcoming these challenges requires a sustained global commitment. AMR demands a coordinated "One Health" approach that integrates surveillance and control strategies across human health, animal health, agriculture, and the environment [34]. The WHO's BPPL serves as a critical guide for focusing these research efforts and investments on the most threatening pathogens, aiming to mitigate the global public health crisis of antimicrobial resistance [33].

From Bench to Insight: Advanced Techniques for Profiling and Targeting Intrinsic Barriers

Genomic and Metagenomic Mining for Predicting Intrinsic Resistomes