High-Resolution Subtyping with Multiplex PCR: A Comprehensive Guide for Pathogen Characterization and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multiplex PCR assays for high-resolution subtyping, a critical methodology for researchers and drug development professionals.

High-Resolution Subtyping with Multiplex PCR: A Comprehensive Guide for Pathogen Characterization and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multiplex PCR assays for high-resolution subtyping, a critical methodology for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles that enable discrimination between closely related pathogen strains, details cutting-edge methodological approaches including high-resolution melting curve analysis and digital PCR multiplexing, and offers solutions for common design and optimization challenges. The content further explores rigorous validation frameworks and comparative performance against other molecular techniques, synthesizing insights from recent applications in bacteriology, virology, and respiratory pathogen detection. This resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement robust subtyping assays that enhance epidemiological surveillance, therapeutic development, and clinical diagnostics.

The Fundamentals of High-Resolution Subtyping: Principles and Diagnostic Power

Defining High-Resolution Subtyping in Pathogen Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

High-resolution subtyping represents a critical advancement in molecular epidemiology, enabling researchers to differentiate pathogen strains beyond the species or serovar level. This granularity is fundamental for effective outbreak investigation, transmission tracking, and pathogen surveillance. In the context of a broader thesis on multiplex PCR assays, this document details how these techniques provide the resolution, speed, and throughput necessary for modern public health responses. These methods allow for the precise identification of genetic variants, facilitating the detection of outbreak clusters and informing targeted control measures. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of subtyping methods, detailed protocols for key assays, and a strategic framework for their application in outbreak settings.

Comparative Analysis of Subtyping Methods

The choice of subtyping method is dictated by the required resolution, throughput, cost, and available laboratory infrastructure. A systematic comparison of 12 typing methods for Salmonella along the poultry production chain demonstrated varying discriminatory powers [1]. The evaluation used the Discrimination Index (DI) to quantify each method's ability to distinguish between closely related isolates [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Pathogen Subtyping Methods

| Method | Discrimination Index (DI) | Resolution | Key Application | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-MVLST | 0.9628 [1] | High | Traceability and virulence assessment [1] | Medium |

| cgMLST (Core Genome MLST) | 0.8541 [1] | High (Gold Standard) | Long-term epidemiological surveillance [1] | High (with WGS) |

| Serotyping | Not Quantified | Low | Basic serogroup identification [1] | High |

| AMR Gene Profile Typing | Not Quantified | Variable | Tracking antimicrobial resistance [1] | High |

| HRM-PCR | 100% Sensitivity & Specificity [2] | High | Differentiation of closely related strains [2] | High |

| Multiplex RT-PCR | 100% Correlation with Serotyping [3] | Medium to High | Simultaneous detection and subtyping of multiple viruses [3] | High |

The data show that CRISPR-MVLST exhibited a higher discriminatory power (DI = 0.9628) than the gold-standard cgMLST method (DI = 0.8541) for the studied Salmonella isolates, making it a powerful tool for traceability along the food chain [1]. Meanwhile, techniques like HRM-PCR and multiplex RT-PCR offer high resolution and are ideally suited for rapid response scenarios.

Experimental Protocols for High-Resolution Subtyping

Protocol: CRISPR-MVLST forSalmonellaSubtyping

This protocol is adapted from a study assessing subtyping methods for tracking Salmonella transmission [1].

1. Principle: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) regions and Multi-Virulence Locus Sequence Typing (MVLST) are sequenced and analyzed. The combination of fast-evolving CRISPR arrays with virulence gene loci provides high discriminatory power for distinguishing closely related bacterial strains [1].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [4])

- PCR reagents: primers for CRISPR and virulence loci, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer

- Thermal cycler

- Sanger or next-generation sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics software for sequence assembly and type assignment

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: DNA Extraction. Extract genomic DNA from pure bacterial cultures using a standardized kit. Quantify DNA concentration and assess purity via spectrophotometry.

- Step 2: PCR Amplification. Perform multiplex PCR to amplify the target CRISPR arrays and specific virulence genes. Use published primer sequences and cycling conditions [1].

- Step 3: Sequencing. Purify PCR amplicons and subject them to Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. Assemble sequence reads and align them to reference databases. Assign a CRISPR-MVLST Sequence Type (CST) based on the combined profile of CRISPR spacers and virulence gene alleles [1].

4. Interpretation: Isolates with identical CSTs are considered closely related and likely part of the same transmission chain. The close correlation between CSTs and the presence of specific antimicrobial resistance (AMR) or virulence factor (VF) genes can also provide functional insights into the characterized strains [1].

Protocol: Multiplex HRM-PCR for DiarrheagenicE. coli(DEC) Subtyping

This protocol is based on a method developed for subtyping five diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes in a single well [2].

1. Principle: Target genes specific to different DEC pathotypes are co-amplified in a single multiplex PCR reaction. Following amplification, High-Resolution Melting (HRM) curve analysis distinguishes the different amplicons based on their unique melting temperature (Tm) values and curve profiles [2].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- HRM-capable real-time PCR instrument

- HRM master mix (including saturating DNA intercalating dye)

- Forward and reverse primers for each DEC pathotype target gene

- Template DNA (limit of detection: 0.5 to 1 ng/μL [2])

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. Prepare a single PCR reaction mix containing all primer sets and the template DNA. The study demonstrated that different DNA concentrations do not influence the subtyping results, confirming reliability [2].

- Step 2: Amplification and Melting. Run the combined multiplex PCR and HRM analysis on a real-time PCR system. The typical cycling and melting conditions are:

- PCR Amplification: 40-45 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension.

- HRM Analysis: Denature at 95°C, cool to a pre-defined temperature (e.g., 60°C), and then slowly increase the temperature (e.g., 0.1°C/sec to 95°C) while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

- Step 3: Analysis. Analyze the resulting melting curves. Different pathotypes are identified by their characteristic peak profiles and distinct Tm values on the derivative melt curve plot [2].

4. Interpretation: The assay demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity for subtyping the five DEC pathotypes [2]. Each pathotype produces a unique HRM signature, allowing for definitive identification from a single reaction.

Protocol: Dual-Target qRT-PCR for Influenza A(H5) Subtyping

This protocol describes an internally controlled, dual-target assay for specific detection of influenza A(H5) viruses, crucial for pandemic preparedness [5].

1. Principle: Two distinct regions of the influenza A(H5) hemagglutinin (HA) gene are targeted simultaneously in a multiplex qRT-PCR. This dual-target design reduces the likelihood of false negatives due to viral evolution and point mutations [5]. The assay includes primers/probes for the influenza A matrix (M) gene for pan-influenza A detection and RNase P as an internal control for sample adequacy.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., EZ1 virus mini kit 2.0 [5])

- One-step qRT-PCR master mix

- Primer-probe sets for H5 Target 1, H5 Target 2, influenza A M gene, and RNase P

- Real-time PCR instrument

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Influenza A(H5) Subtyping

| Reagent | Function | Example | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer-Probe Set 1 | Detects first region of H5 HA gene | GDR4, GDR5, GDR6 [4] [5] | Designed for conserved regions of clade 2.3.4.4b |

| Primer-Probe Set 2 | Detects second region of H5 HA gene | Custom designed [5] | Reduces false negatives via dual-target design |

| Pan-Influenza A Primers-Probe | Broad influenza A detection | Targets M gene [5] | Confirms influenza A virus presence |

| Internal Control | Monitors extraction & inhibition | RNase P primers-probe [5] | Ensures sample quality and reaction validity |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Purifies RNA from specimens | EZ1 virus mini kit 2.0 [5] | Ensures high-quality template for PCR |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: RNA Extraction. Extract total nucleic acids from 400 μL of clinical upper respiratory specimen (e.g., swab in viral transport media). Elute in 60 μL of elution buffer [5].

- Step 2: qRT-PCR Setup. Combine eluted RNA with the master mix and the multiplexed primer-probe sets. The final reaction contains primers and probes for the two H5 targets, the influenza A M gene, and RNase P.

- Step 3: Amplification. Run the qRT-PCR with the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 10 min (reverse transcription), 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min [5].

- Step 4: Analysis. A sample is considered positive for influenza A(H5) if one or both H5 targets amplify with a cycle threshold (Ct) value below the validated cutoff, and the influenza A M gene is also detected. The RNase P signal confirms adequate nucleic acid extraction and absence of significant PCR inhibitors.

4. Interpretation: The assay showed a 95% lower limit of detection (LLOD) of <0.5 to 2.5 copies/μL for different H5 clades and demonstrated 100% specificity with no cross-reactivity against non-H5 influenza A viruses [5]. Continuous sequence surveillance is recommended to ensure primer-probe sets remain matched to circulating strains.

Strategic Implementation in Outbreak Investigation

Integrating high-resolution subtyping into field epidemiology requires a structured approach. The following workflow aligns with the CDC's Field Epidemiology Manual, illustrating how these methods are embedded in the investigative process [6].

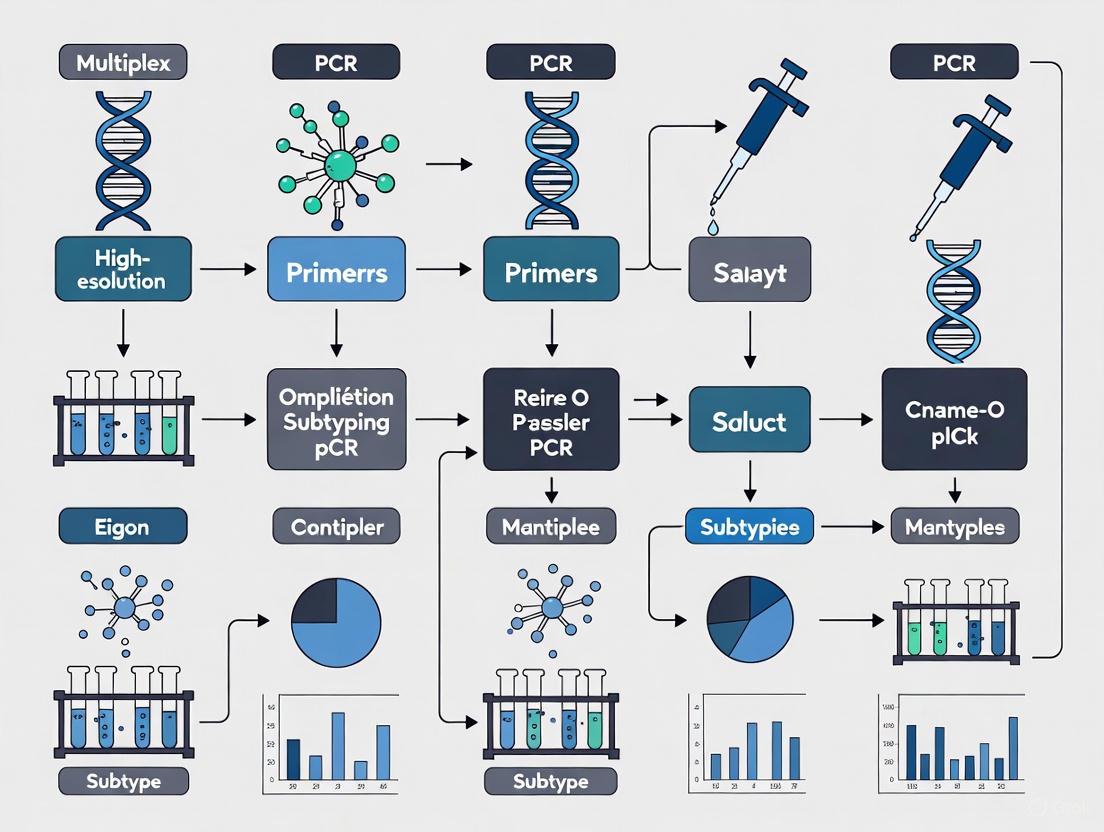

Diagram 1: Integration of high-resolution subtyping into the field investigation workflow. The process begins with standard epidemiological steps (yellow) [6], leading to analytics where subtyping (blue) is applied to define clusters and guide targeted control measures (red).

The utility of subtyping is maximized when it directly informs public health action. As shown in Diagram 1, data from methods like CRISPR-MVLST or HRM-PCR are critical for defining an outbreak cluster with precision, moving beyond temporal and spatial associations to genetic relatedness [1] [6]. This high-resolution confirmation enables the implementation of more targeted and effective control measures, potentially interrupting transmission with greater efficiency.

High-resolution subtyping methods, particularly advanced multiplex PCR assays and next-generation sequencing techniques, are indispensable tools in the modern molecular epidemiology toolkit. As demonstrated, methods like CRISPR-MVLST, HRM-PCR, and dual-target qRT-PCR provide the discriminatory power necessary for precise pathogen tracking, source attribution, and resistance profiling. Their integration into a structured field investigation framework ensures that molecular data translates directly into actionable public health interventions, ultimately strengthening global health security and pandemic preparedness.

Multiplex PCR assays represent a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics, enabling the simultaneous detection and subtyping of multiple pathogens or genetic markers in a single reaction. For high-resolution subtyping research, the core of a successful multiplex assay lies in the careful selection of target genes, including conserved regions for broad detection and strain-specific markers for precise differentiation [7]. This protocol details the application of these core components through a pan-genome analysis approach for the specific detection of Bacillus anthracis, a critical pathogen for public health and biodefense [8]. The methodologies described herein provide a framework for developing robust, specific, and informative multiplex PCR assays suitable for demanding applications in research and drug development.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and their functions for the development and execution of multiplex PCR assays as discussed in this application note.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Multiplex PCR Assay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Primer/Probe Sets | BA1698, BA5354, BA5361 primers [8] | Target strain-specific chromosomal markers for precise identification. |

| Detection Probes | 6-FAM, ROX-labeled TaqMan probes [9] [5] | Enable multiplexed, real-time detection of different targets via distinct fluorescent signals. |

| Enzyme Master Mix | Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase [7] | Enhances specificity by preventing non-specific amplification during reaction setup. |

| PCR Additives | Betaine, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) [7] | Destabilize GC-rich secondary structures, improving amplification efficiency of complex templates. |

| Nucleic Acid Controls | Synthesized ssDNA/ssRNA targets [5] | Act as quantitative standards for determining the limit of detection (LOD) and assay validation. |

Core Genetic Components for Subtyping

The discriminatory power of any multiplex PCR assay is founded on the strategic choice of genetic targets. These can be broadly classified into conserved regions and variable, strain-specific markers.

Conserved Genetic Regions

Conserved genes are typically housekeeping genes or essential functional genes that are present across all members of a species or genus. In multiplex assays, they serve as indispensable internal controls, confirming the presence of the target organism's DNA and the success of the amplification reaction itself. For instance, in an influenza A subtyping assay, the matrix (M) gene is a classic conserved target used for pan-influenza A detection, ensuring that all typeable influenza A viruses are captured before subtyping is attempted [5].

Strain-Specific Markers and Virulence Determinants

Strain-specific markers are genetic sequences unique to a particular strain, clade, or serotype. They are the key to high-resolution subtyping and are often located on pathogenicity islands, virulence plasmids, or prophage regions.

Table 2: Strain-Specific Targets for Pathogen Subtyping

| Pathogen | Assay Purpose | Strain-Specific Targets | Genetic Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus anthracis [8] | Specific detection | BA1698, BA5354, BA5361 | Chromosome (novel and prophage regions) |

| Salmonella Typhimurium [9] | Virulence & Resistance Genotyping | spvC (virulence), sul1, blaTEM (resistance), DT104 spacer | Virulence plasmid (pSLT), SGI1, Chromosome |

| Influenza A Virus (Swine) [10] | Hemagglutinin (HA) Subtyping | H1, H3 | Viral RNA genome |

| Influenza A Virus (Swine) [10] | Neuraminidase (NA) Subtyping | N1, N2 | Viral RNA genome |

| Avian Influenza A(H5) [5] | Dual-Target Subtyping | Two distinct regions of the H5 Hemagglutinin gene | Viral RNA genome |

The selection of these markers requires comprehensive genomic analysis. In the case of B. anthracis, a pan-genome analysis of 151 genomes identified 30 chromosome-encoded genes exclusive to this species, overcoming the challenge of genetic similarity with B. cereus and B. thuringiensis [8]. For Salmonella, targets were chosen from Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands (SPIs) like SPI-2 (ssaQ), SPI-5 (sopB), and the Salmonella Genomic Island 1 (SGI1), which harbors antimicrobial resistance genes [9].

Experimental Protocol: Pan-Genome Analysis for Marker Discovery

This protocol outlines the methodology for identifying strain-specific chromosomal markers, as demonstrated for Bacillus anthracis [8].

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflow for the identification and validation of strain-specific genetic markers.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Genome Dataset Curation

- Obtain a diverse set of complete genome sequences from public databases like NCBI. For the referenced study, this included 50 genomes each of B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis, plus one B. weihenstephanensis as an outgroup [8].

- Ensure metadata (e.g., strain, source, date) is recorded for downstream analysis.

Step 2: De Novo Genome Annotation

- Annotate all genomes uniformly using a tool such as Prokka version 1.11 [8].

- Prokka rapidly annotates prokaryotic genomes, identifying genes, RNAs, and other features, producing standard output files (GFF, GBK) for each genome.

Step 3: Pan-Genome Analysis

- Input the Prokka-generated annotation files into Roary version 3.13.0 [8].

- Roary constructs the pan-genome, classifying genes into core (present in all strains), soft core, shell, and cloud (strain-specific) genes.

- The key output is a gene presence/absence matrix (CSV file) that details which genes are found in which strains.

Step 4: Identification of Exclusive Genes

- Parse the gene presence/absence matrix using a custom script (e.g., Perl script as used in the study) [8].

- The script flags genes that are present in all B. anthracis strains but completely absent from all B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains in the dataset.

Step 5: In silico Specificity Validation

- Perform a nucleotide BLAST (BLASTn) search for each candidate exclusive gene against the entire NCBI database, excluding B. anthracis [8].

- Confirm that the sequences have no significant homology to genes from any other organism to ensure specificity.

Step 6: Confirmatory Local BLAST Alignment

- Perform a local BLAST alignment against a larger, independent set of B. anthracis genomes (e.g., 132 chromosomally complete genomes from GenBank) [8].

- This step verifies that the identified marker genes are consistently present and well-conserved across a wide population of the target strain.

Step 7: Functional Analysis (Optional)

- Use databases like STRING v.12.0 to predict physical and functional protein-protein interactions among the proteins encoded by the newly identified genes [8].

- This can provide insights into the potential biological roles and pathways these genes are involved in.

Experimental Protocol: Multiplex PCR Assay Validation

Once candidate markers are identified, they must be incorporated into a validated multiplex PCR assay.

The subsequent workflow details the critical steps for establishing and validating the multiplex PCR assay.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Primer and Probe Design

- Design primers and probes to have similar melting temperatures (Tm) to ensure uniform amplification efficiency [7].

- Aim for primers 18-30 bp long with a GC content of 35-60% [7].

- For real-time PCR, select fluorophores with non-overlapping emission spectra (e.g., FAM, HEX/VIC, ROX, Cy5) [11] [9].

- Critical: Check for self-complementarity and primer-primer interactions to minimize dimer formation.

Step 2: Reaction Optimization and Setup

- Use a hot-start Taq DNA polymerase to minimize non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation [7].

- Optimize the concentration of MgCl₂, primers, and probes. Multiplex reactions may require higher enzyme concentrations than uniplex PCR [7].

- Consider adding PCR enhancers like betaine or DMSO to assist in the amplification of templates with secondary structures or high GC content [7].

- The final reaction mix typically includes:

- 1X PCR Buffer

- Hot-start Taq DNA Polymerase

- dNTPs (e.g., 200 µM each)

- Optimized concentrations of MgCl₂, primers, and probes

- Template DNA (2-5 µL)

- Nuclease-free water to volume.

Step 3: Determine Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

- Serially dilute quantified target nucleic acid (e.g., synthesized single-stranded DNA [5] or genomic RNA from cultured isolates [10]).

- Test a high number of replicates (e.g., 20 replicates per dilution) to statistically determine the 95% LOD.

- For the B. anthracis study, multiplex PCR was established using three identified genes (BA1698, BA5354, BA5361) [8].

Step 4: Determine Analytical Specificity

- Test the assay against a panel of genomic DNA or RNA from closely related non-target strains and other common flora.

- For the avian influenza A(H5) assay, specificity was confirmed using non-H5 influenza A viruses and clinical samples positive for other respiratory pathogens [5].

Step 5: Assay Evaluation with Clinical or Environmental Specimens

- Validate the assay's performance using a collection of well-characterized strains or clinical samples.

- The B. anthracis multiplex PCR was tested on 17 strains, including vaccine and virulent strains from diverse geographic and temporal origins [8].

Quantitative Data from Multiplex Assay Applications

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Representative Multiplex PCR Assays

| Assay Description | Targets | Analytical Sensitivity (LOD) | Specificity / Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. anthracis Chromosomal Detection | BA1698, BA5354, BA5361 | Established | 30 exclusive genes identified; assay differentiated B. anthracis from B. cereus/thuringiensis. | [8] |

| Influenza A(H5) Subtyping (qRT-PCR) | H5 (dual-target), M gene, RNase P | Clade 1: 2.5 copies/µLClade 2.3.4.4b: <0.5 copies/µL | 100% specificity on non-H5 panel (n=16); no false positives in 155 clinical samples. | [5] |

| Swine IAV Subtyping (RT-qPCR) | H1, H3, N1, N2 | 5.09 × 10¹ to 5.09 × 10³ copies/µL | 100% diagnostic sensitivity on 85 IAVs; subtyped 74% of clinical samples. | [10] |

| S. Typhimurium Virulence/Resistance | 10 markers (e.g., ssaQ, sopB, sul1, blaTEM) | Established | Distinguished 34 genotypes; detected markers in 538 strains with varying prevalence. | [9] |

In the evolving landscape of molecular diagnostics and research, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has emerged as a transformative methodology, particularly for high-resolution subtyping research. This technique enables the simultaneous amplification of multiple DNA or RNA targets in a single reaction, using multiple primer sets in one tube. For researchers and drug development professionals focused on detailed genetic characterization, multiplex PCR offers a powerful tool for uncovering complex biological signatures that singleplex methods cannot efficiently reveal.

The fundamental distinction lies in the reaction design: where singleplex PCR amplifies one target per reaction, multiplex PCR can simultaneously detect numerous targets—from a handful to dozens—within the same sample volume. This capability is particularly valuable for comprehensive profiling of pathogens, genetic variants, and expression patterns, which forms the cornerstone of advanced research in oncology, infectious diseases, and personalized medicine. As research demands more data from limited samples, multiplex PCR provides an efficient solution that conserves precious materials while accelerating discovery timelines.

Comparative Advantages of Multiplex PCR

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Multiplex PCR delivers significant advantages across key performance parameters essential for research efficiency and data quality. The table below summarizes the core benefits quantified from recent market analyses and technical studies:

Table 1: Performance advantages of multiplex PCR over singleplex approaches

| Parameter | Multiplex PCR Advantage | Impact on Research Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Consumption | Up to 80% reduction in sample volume required [12] | Enables more tests from biobanked/rare samples |

| Data Point Cost | Significant reduction in cost per data point [12] | Makes large-scale studies more economically viable |

| Throughput Time | 50% faster procedure compared to running multiple singleplex reactions [12] | Accelerates research timelines and data generation |

| Workflow Efficiency | Fewer pipetting steps and reduced hands-on time [13] | Minimizes manual errors and increases reproducibility |

| Information Yield | Multiple data points from a single sample [12] | Provides more comprehensive profiling from limited material |

Applications in High-Resolution Subtyping

The advantages of multiplex PCR translate directly into enhanced capabilities for specific research applications critical to drug development and molecular characterization:

Pathogen Subtyping and Co-infection Detection: Multiplex PCR enables simultaneous identification of multiple pathogen strains or species from a single sample, providing comprehensive profiles that singleplex methods cannot efficiently generate. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, this capability was leveraged to differentiate between SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, and other respiratory pathogens in a single test, demonstrating its utility for syndromic testing and surveillance [13].

Genetic Variant Profiling: In oncology research, multiplex PCR facilitates the simultaneous detection of multiple single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations, and fusion genes. For example, the USE-PCR approach enables 32 single nucleotide variants to be called simultaneously with up to 86.5% accuracy in cancer cell lines, making it invaluable for comprehensive tumor genotyping [14].

Avirulence Gene Monitoring: In plant pathogen research, tools combining multiplex PCR with high-throughput sequencing enable characterization of allelic variants for eight avirulence genes in fungal populations. This approach allows large-scale monitoring of pathogen evolution and early detection of resistance breakdowns in agricultural settings [15].

Figure 1: Workflow comparison showing efficiency gains with multiplex PCR

Experimental Design and Protocol Optimization

Critical Considerations for Multiplex Assay Development

Designing effective multiplex PCR assays requires addressing several technical challenges that are less pronounced in singleplex formats:

Primer Compatibility: All primers in the reaction must function efficiently under identical thermal cycling conditions and buffer composition without forming primer-dimers or cross-hybridizing. This requires careful in silico analysis of potential interactions before experimental validation [13].

Reagent Competition: Multiple targets compete for shared reagents (dNTPs, enzymes, magnesium ions), which can lead to imbalanced amplification. Without optimization, this may result in preferential amplification of certain targets and reduced sensitivity for others [16].

Detection System Capacity: Multiplex assays require advanced fluorescence detection systems and non-overlapping fluorophores to accurately distinguish multiple signals. The number of targets is ultimately limited by the instrument's optical channels and the availability of spectrally distinct fluorophores [13].

Protocol for Multiplex PCR in Avirulence Gene Subtyping

The MPSeqM protocol exemplifies a sophisticated application of multiplex PCR for high-resolution subtyping in plant pathology research [15]. This method enables characterization of eight avirulence genes in the fungal pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans through pooled sample analysis:

Table 2: Key research reagents for multiplex PCR subtyping

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Multiplex PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Master Mix | NUHI Pro NGS PCR Mix [17] | Provides optimized enzyme blend for balanced multi-target amplification |

| Primer Design Tools | ecoPrimers software [18] | Enables in silico design of compatible primer sets |

| Universal Probe Systems | USE-PCR color-coded tags [14] | Decouples detection from target amplification for standardized signal generation |

| Sample Preservation Kits | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [18] | Maintains DNA integrity from limited or precious samples |

| Library Preparation | Hieff NGS DNA Selection Beads [17] | Enables efficient target enrichment for downstream sequencing |

Procedure:

DNA Extraction: Grind pathogen samples (e.g., fungal-infected leaf tissue) with homogenization beads. Extract DNA using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit with modified elution (75µL initial elution, 15-minute incubation, followed by 100µL second elution, 1-minute incubation) [18].

Multiplex PCR Assembly: Prepare 25µL reactions containing:

- 50ng template DNA

- 4µL primer mix (containing 8 AvrLm gene primer pairs and Actin control)

- 12.5µL PCR master mix

- Optimized primer concentrations to balance amplification efficiency

Thermal Cycling: Execute amplification with parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10-15 minutes

- 30-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10-20 seconds

- Annealing: Optimized temperature (e.g., 63°C) for 45-60 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1-5 minutes

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

Pooling and Sequencing: Combine PCR products from multiple samples, then sequence using Illumina MiSeq technology. Analyze reads by mapping to an AvrLm sequence database with thresholds defined from control samples [15].

Figure 2: End-to-end workflow for multiplex PCR-based subtyping

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Performance Trade-offs in Multiplexing

While multiplex PCR offers substantial benefits, researchers must acknowledge and address its limitations through careful experimental design:

Detection Sensitivity Disparities: Comparative studies between singleplex and multiplex approaches have revealed performance variations across target types. In vector-host-parasite detection systems, singleplex clearly outperformed multiplex for the parasite component, despite similar performances for host and vector detection [18]. This suggests that lower-abundance targets may require special optimization in multiplex formats.

Primer Competition Effects: When multiple targets are amplified in a single reaction, they compete for dNTPs, enzymes, and other reaction components. If one target amplifies more efficiently, it may deplete reagents needed for other targets, potentially leading to poor amplification of less abundant sequences [16].

Initial Development Investment: Developing and validating a multiplex PCR assay involves greater time and resource investment compared to singleplex assays. However, these upfront efforts yield significant time and cost savings once the assay is optimized and routinely implemented [13].

Mitigation Strategies for Multiplex PCR Challenges

Several approaches can address the technical challenges associated with multiplex PCR:

Primer Limiting: For targets that outcompete others for reagents, significantly reducing the primer concentration causes early plateauing, preserving reagents for other targets in the reaction [16].

Universal Probe Systems: Technologies like USE-PCR employ universal hydrolysis probes with amplitude modulation and multispectral encoding, enabling higher-order multiplexing while standardizing data analysis across platforms [14].

Comprehensive Validation: Always compare multiplex results with singleplex configurations using 5-6 samples from both experimental and control groups. If results are comparable between configurations, it is safe to proceed with multiplexing; if not, further optimization is required [16].

Emerging Applications in Research and Diagnostics

Multiplex PCR continues to evolve with technological advancements, opening new possibilities for high-resolution subtyping research:

Universal Signal Encoding PCR (USE-PCR): This novel approach combines universal hydrolysis probes, amplitude modulation, and multispectral encoding to overcome traditional limitations in multiplexing. USE-PCR has demonstrated 92.6% ± 10.7% mean target identification accuracy at high template copy and 97.6% ± 4.4% at low template copy, with a dynamic range spanning four orders of magnitude [14].

High-Resolution HLA Genotyping: Optimized multiplex PCR combined with next-generation sequencing enables comprehensive HLA genotyping across six loci (HLA-A, -B, -C, -DPB1, -DQB1, -DRB1) with ≥95% accuracy at four-digit resolution. This approach offers a reliable, cost-effective method for donor-recipient matching in transplantation medicine [17].

Multiplexed Pathogen Surveillance: The combination of multiplex PCR with high-throughput sequencing enables large-scale monitoring of pathogen populations. The MPSeqM tool successfully characterized eight avirulence genes in field populations of Leptosphaeria maculans, with proportions of virulent isolates perfectly correlating with phenotypic data [15].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning further enhances multiplex PCR applications, improving classification accuracy of experiments utilizing synthetic DNA templates by combining ML algorithms with real-time digital PCR systems [19]. These advancements position multiplex PCR as an increasingly powerful tool for high-resolution subtyping across diverse research domains.

Application Note: Multiplex PCR for Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Profiling

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant global health threat, necessitating robust surveillance methods. Multiplex PCR has emerged as a powerful tool for high-throughput screening and identification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) across diverse samples, from clinical isolates to environmental microbiomes [20].

Protocol: Standard Uniplex PCR for Antibiotic Resistance Determinants

This protocol details the detection of four key antibiotic resistance determinants: sul1 (sulfonamide resistance), erm(B) (erythromycin resistance), ctx-m-32 (cefotaxime resistance, an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase), and intI1 (class 1 integron integrase, a marker associated with human-impacted samples and mobile genetic elements) [21].

- Sample Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from samples (e.g., bacterial cultures, environmental biomass) using a commercial kit. Ensure DNA purity (1.8 < OD260/280 < 2.0) and absence of degradation [20].

- Primer Design: Utilize specific primers with known sequences and melting temperatures (Tm) as listed in [21].

- PCR Master Mix Preparation: For a 20 µL reaction, combine components as specified in the table below. Prepare a master mix sufficient for all reactions, including positive and negative controls.

Table 1: PCR Master Mix Recipe for Uniplex ARG Detection

| Component | Description | Volume/RXN (µL) | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer 1 | Forward Primer (100µM) | 0.4 | 2µM |

| Primer 2 | Reverse Primer (100µM) | 0.4 | 2µM |

| TAQ | JumpStart RedTaq ReadyMix | 10 | 1X |

| PCR Water | Nuclease-free Water | 4.2 | N/A |

| Sample | Template DNA | 5.0 | - |

| Total Volume | 20.0 |

- Thermal Cycling: Perform amplification in a thermal cycler under the following conditions, optimized for each gene [21]:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (35 cycles): Denature at 94°C for 30 seconds, anneal at the primer-specific Tm (see Table 2) for 30 seconds, and extend at 72°C for 2 minutes.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Analysis: Resolve PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (e.g., 3.5% gel) and visualize under UV light after staining with SYBR SAFE or ethidium bromide. Compare amplicon sizes to a DNA ladder and positive controls for confirmation.

Table 2: Primer Sequences and Amplicon Sizes for ARG Detection

| Gene | Sequence (5' to 3') | Tm (°C) | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sul1 | F: GACGAGATTGTGCGGTTCTTR: GAGACCAATAGCGGAAGCC | 64 | 185 |

| erm(B) | F: GATACCGTTTACGAAATTGGR: GAATCGAGACTTGAGTGTGC | 58 | 364 |

| ctx-m-32 | F: CGTCACGCTGTTGTTAGGAAR: CGCTCATCAGCACGATAAAG | 63 | 156 |

| intI1 | F: ACATGCGTGTAAATCATCGTCGR: CTGGATTTCGATCACGGCACG | 60 | 473 |

Performance and Comparison with Alternative Methods

Multiplex and uniplex PCR are highly sensitive for targeted ARG detection. A 2023 study comparing quantitative PCR (qPCR) and metagenomics for AMR screening found that qPCR (a fluorescence-based multiplexable PCR method) offers superior sensitivity and quantitative accuracy for specific, low-abundance targets in complex samples like wastewater and animal faeces [22]. In contrast, metagenomics provides a much broader, untargeted overview of the resistome but with lower sensitivity for individual genes [22]. This makes multiplex PCR ideal for focused surveillance of priority resistance genes.

Application Note: Family-Wide Multiplex PCR for Viral Evolution and Discovery

Tracking viral evolution and identifying novel zoonotic pathogens require assays that can detect both known and unknown viruses. Family-wide multiplex PCR targets highly conserved regions within viral families (e.g., Coronaviridae, Orthomyxoviridae), enabling the detection of known members and the discovery of novel variants through subsequent sequencing [23].

Protocol: Multiplex RT-PCR and Nanopore Sequencing (FP-NSA)

This protocol, termed Family-wide PCR and Nanopore Sequencing of Amplicons (FP-NSA), is designed for surveillance of zoonotic respiratory viruses like influenza and coronaviruses [23].

- Target Selection and Primer Design: Identify conserved genomic regions (e.g., RNA-dependent RNA polymerase ORF1ab for coronaviruses, matrix M gene for influenza viruses) from a diverse set of reference sequences. Design primers to these regions to ensure broad reactivity within the target viral family [23].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total RNA from clinical specimens (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs) using a kit such as the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Include a DNase treatment step to remove contaminating genomic DNA.

- Multiplex RT-PCR:

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction containing:

- 4 µL of One-Step RT-PCR Buffer 5X

- 0.8 µL One-Step RT-PCR Enzyme Mix

- Primers at optimized concentrations (e.g., 900 nM for coronavirus primers, 100 nM for influenza virus primers)

- 2 µL of RNA template

- Perform amplification with the following cycling conditions [23]:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 30 minutes

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 15 minutes

- 40 Cycles: 94°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction containing:

- Nanopore Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the multiplex PCR amplicons using a portable MinION device. The resulting data can be analyzed in real-time for pathogen identification and used for phylogenetic analysis to track viral evolution and identify novel strains, such as the novel γ-coronavirus discovered using this method [23].

Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Surveillance

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Viral Surveillance Workflows

| Item | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| One-Step RT-PCR Kit | Combined reverse transcription and PCR amplification | Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR Kit [23] |

| Family-Wide Primers | Broadly target conserved regions of viral families | Custom primers for CoV ORF1ab, IAV M gene [23] |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kit | Library preparation and barcoding for multiplex sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding Kit [23] [24] |

| Portable Sequencer | Real-time, long-read sequencing in field settings | MinION device (Oxford Nanopore) [23] [24] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Taxonomic classification and phylogenetic analysis | Centrifuge, BLAST, autoMLST [23] [25] |

Application Note: High-Resolution Subtyping of Bacterial Clones

Strain-level typing of bacterial pathogens is critical for hospital infection control and outbreak investigation. Multiplex PCR-based methods offer a rapid, cost-effective, and high-resolution alternative to traditional techniques like Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) for discerning bacterial clones [26] [25].

Protocol: XbaI-based Multiplex PCR forKlebsiella pneumoniaeTyping

This novel method exploits single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variations in and around XbaI-restriction sites within bacterial genomes to generate strain-specific amplification profiles, integrating the discrimination power of PFGE with the simplicity of PCR [25].

- In Silico Analysis and Primer Design: Analyze whole genome sequences of target species (e.g., K. pneumoniae) to map XbaI-restriction sites (5'...T↓CTAGA...3'). Identify syntenic regions (conserved gene neighborhoods) around these sites and design primers that flank these regions. Select a set of primers that provide high discriminatory power [25].

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from a pure bacterial culture. A protocol involving mechanical lysis (e.g., using a TissueLyser with glass beads) followed by purification with a kit like the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) is suitable [25].

- Multiplex PCR Amplification:

- Prepare a 25 µL reaction containing [25]:

- 5 µL of 5X Taq DNA Polymerase Buffer

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 1 mM MgCl₂

- 0.5 µM of each primer

- 2.5 U of Taq DNA Polymerase

- 2.5 µL of DNA template

- Perform amplification with the following cycling conditions [25]:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 40 Cycles: 93°C for 30 seconds, 57°C for 40 seconds, 72°C for 40 seconds

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Prepare a 25 µL reaction containing [25]:

- Data Analysis: Resolve PCR products on a high-percentage agarose gel (e.g., 3.5%). Create a dendrogram based on the banding pattern using software like PyElph 1.3. The resulting clusters can be compared to known sequence types (STs) for validation, demonstrating concordance with established typing methods like MLST [25].

Advanced Technique: Melting Curve Analysis for Plasmid Replicon Typing

For rapid identification of plasmids carrying AMR genes, real-time PCR with melting curve analysis can be employed. This method uses SYBR Green dye and primers specific to plasmid replicon types. Post-amplification, the amplicon is melted, generating a unique melting temperature (Tm) peak for each replicon type. This technique is fast, sensitive, and reduces contamination risk by eliminating the need for gel electrophoresis [27].

Table 4: Comparison of Bacterial Typing Methods

| Method | Principle | Discriminatory Power | Turnaround Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XbaI-multiplex PCR [25] | Amplification of genomic regions flanking XbaI sites | High (clusters with MLST) | 4-6 hours | Cost-effective, high resolution, simple equipment |

| rep-PCR [26] | Amplification of repetitive intergenic sequences | High | ~1 hour (automated) | High-throughput, automated (DiversiLab system) |

| Melting Curve Analysis [27] | Tm analysis of plasmid replicon amplicons | Targeted (plasmid typing) | ~2 hours | Closed-tube system, high sensitivity, no gel needed |

| PFGE [25] | Macrorestriction digestion and pulsed-field electrophoresis | Very High (Gold Standard) | 2-4 days | High discrimination, well-established |

| Whole Genome Sequencing [25] | Determination of complete DNA sequence | Highest | Days to weeks, plus bioinformatics | Ultimate resolution, identifies all genetic variation |

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Research and Diagnostics

High-Resolution Melting (HRM) Curve Analysis for Genotype Discrimination

High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis is a powerful, post-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique that enables precise genotyping, species identification, and sequence variant detection based on the disassociation characteristics of double-stranded DNA. This method leverages the fact that DNA melting behavior is determined by its nucleotide sequence, length, and GC content, allowing even single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to be distinguished through their unique melting profiles [28]. The technique involves amplifying target DNA in the presence of a saturating DNA-binding fluorescent dye, followed by gradual heating while monitoring fluorescence loss as double-stranded DNA denatures [29]. The resulting melting curves provide distinctive fingerprints that can discriminate between different genotypes, species, or strains with high accuracy and resolution.

Within multiplex PCR assays for high-resolution subtyping research, HRM analysis offers significant advantages as a rapid, closed-tube, cost-effective approach that requires no additional probes or processing steps after amplification. This makes it particularly valuable for applications requiring high-throughput screening, such as microbial pathogen detection, species authentication, and genetic variation studies [30]. The technology has proven effective across diverse fields, from clinical diagnostics to food authenticity testing, providing researchers with a robust tool for precise genotype discrimination.

Principles of HRM Technology

Fundamental Mechanism

HRM analysis operates on the principle that the melting temperature (Tm) of a DNA fragment—the temperature at which half of the duplex DNA dissociates into single strands—is determined by its length, GC content, and nucleotide sequence. During the HRM process, amplified PCR products are subjected to a temperature gradient while fluorescence is continuously monitored using specialized instruments capable of precise temperature control and sensitive detection [31]. The intercalating dye fluoresces strongly when bound to double-stranded DNA but loses fluorescence as the DNA strands separate, generating characteristic melting curves for each genetic variant.

The discriminatory power of HRM stems from its ability to detect minute differences in melting behavior between amplicons with variant sequences. These differences manifest as shifts in melting temperature or alterations in curve shape when compared to reference samples [29]. Normalization algorithms enhance these differences by setting pre- and post-melting regions to defined values, while difference plots further amplify distinctions by subtracting a control curve from all samples, facilitating visual interpretation of variants [28].

Critical Design Considerations

Successful HRM assay design requires careful consideration of several factors. Amplicon length typically ranges from 50-300 base pairs, with shorter fragments often providing better resolution [31]. Primer design must avoid secondary structures and ensure specificity, while GC content significantly influences melting temperature and curve shape [32]. The choice of saturating DNA dye is crucial, with EvaGreen and SYTO9 being commonly used options that provide uniform binding without inhibiting PCR amplification [30].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing HRM Assay Performance

| Factor | Impact on HRM Analysis | Optimal Range/Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Amplicon Length | Determines melting transition sharpness | 50-300 bp (shorter preferred) |

| GC Content | Affects melting temperature | Varies by application |

| Sequence Composition | Influences curve shape and Tm | Target regions with diagnostic SNPs |

| DNA Dye | Affects resolution and PCR efficiency | Saturating dyes (EvaGreen, SYTO9) |

| DNA Quality/Quantity | Impacts reproducibility | 5-8 ng/μL typical sensitivity [28] |

| Instrument Precision | Determines data quality | High-resolution real-time PCR systems |

Applications in Genotype Discrimination and Species Identification

HRM analysis has been successfully implemented across diverse research fields for genotype discrimination and species identification, demonstrating particular utility in multiplex assay formats.

Microbial Pathogen Detection

In clinical microbiology, HRM enables simultaneous detection and differentiation of multiple pathogens from complex samples. A multiplex HRM assay developed for urinary tract infections simultaneously detects five bacterial pathogens (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, and group B streptococci) directly from urine samples with sensitivity of 100% and specificity ranging from 99.3-100% for all test pathogens [31]. The assay generates five distinct melt curves with detection limits of 1.5 × 10³ CFU/ml for E. coli and K. pneumoniae and 1.5 × 10² CFU/ml for the other targets, providing results within 5 hours compared to 24-48 hours for conventional culture.

For zoonotic abortifacient agents, a novel multiplex qPCR-HRM assay simultaneously detects Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii, Leptospira spp., and Listeria monocytogenes in cattle, sheep, and goats [29]. The assay generates four well-separated melting peaks with Tm values of 83.2°C, 80.6°C, 77.4°C, and 75.6°C, respectively, enabling identification of individual and co-infections. The method demonstrated high analytical sensitivity with detection limits between 4.26-10.20 copies per reaction across the different targets.

Food Authenticity and Species Authentication

HRM analysis has proven valuable for enforcing food labeling regulations and preventing species substitution. For mussel authentication, a panel of 10 highly informative SNPs genotyped by PCR-HRM accurately identifies M. chilensis, M. edulis, M. galloprovincialis, and M. trossulus in fresh, frozen, and canned products [28]. The method demonstrated high robustness against variations in DNA quality, annealing time and temperature, primer concentration, and reaction volume, with zero false-positive and false-negative rates and sensitivity ranging between 5-8 ng/μL.

In food safety applications, a multiplex HRM assay targeting invA, stn, and fimA genes reliably detects Salmonella with three specific, well-separated melting peaks at average Tm values of 77.21°C, 81.43°C, and 85.44°C, respectively [30]. This multi-target approach reduces false negatives from strains lacking one target gene and minimizes false positives from non-Salmonella strains possessing only one gene, achieving detection of 10³ CFU/g in most food samples after 6-hour enrichment.

Parasite Identification and Genetic Variation

HRM facilitates rapid discrimination of medically important parasites, including Plasmodium species causing malaria. An HRM assay targeting the 18S SSU rRNA region differentiates Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax with a significant Tm difference of 2.73°C [33]. The method demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, with complete agreement with sequencing results in tested samples, providing a cost-effective alternative for species identification in endemic regions.

Viral genotyping also benefits from HRM analysis, as demonstrated by an assay differentiating variant groups of Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GLRaV-3), a significant plant pathogen [32]. The universal primer set targeting the Hsp70h gene detected and differentiated GLRaV-3 variant groups I, II, III, and VI, though groups I and II required a subsequent real-time RT-PCR HRM with a different primer set for discrimination due to their similar melting temperatures.

Table 2: Representative HRM Applications in Genotype Discrimination

| Application Field | Targets Discriminated | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Tract Infections | 5 bacterial pathogens | Sensitivity: 100%, Specificity: 99.3-100% | [31] |

| Zoonotic Abortifacients | 4 bacterial pathogens | Detection limit: 4.26-10.20 copies/reaction | [29] |

| Mussel Authentication | 4 Mytilus species | False-positive/negative rates: 0%, Sensitivity: 5-8 ng/μL | [28] |

| Salmonella Detection | 3 target genes | Detects 10³ CFU/g after 6h enrichment | [30] |

| Malaria Diagnosis | 2 Plasmodium species | Complete agreement with sequencing | [33] |

| Plant Virus Typing | 4 GLRaV-3 variant groups | Successful differentiation of groups I, II, III, VI | [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplex HRM for Bacterial Pathogen Detection

This protocol adapts the methodology for simultaneous detection of four zoonotic abortifacient agents (Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii, Leptospira spp., and Listeria monocytogenes) [29].

Reagent Preparation

- Reaction Mix: 4 μL of 5x HOT FIREPol EvaGreen HRM Mix (no ROX)

- Primers: 0.5 μL of each primer (10 pmol) for all four targets

- Template DNA: 1 μL (10-20 ng/μL)

- Nuclease-free water: to 20 μL total reaction volume

PCR Amplification and HRM Conditions

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 15 minutes

- Amplification (45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: 63°C for 20 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 25 seconds

- HRM Analysis:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Renaturation: 60°C for 1 minute

- Melting: Continuous monitoring from 60°C to 95°C with 0.2°C increments

Data Analysis

- Normalize melting curves by pre- and post-melting regions

- Generate difference plots by subtracting reference curve

- Identify pathogens based on characteristic Tm values:

- Brucella spp.: ~83.2°C

- Coxiella burnetii: ~80.6°C

- Listeria monocytogenes: ~77.4°C

- Leptospira spp.: ~75.6°C

Protocol 2: SNP-Based Species Identification

This protocol follows the approach for mussel species identification using informative SNPs [28].

Assay Design and Validation

- SNP Selection: Identify highly informative SNPs using FST outlier and MAFMAX criteria

- Primer Design: Design primers flanking target SNPs (amplicons <150 bp)

- In Silico Validation: Predict Tm differences using uMelt or similar software

- Experimental Validation: Test specificity with reference samples

HRM Reaction Setup

- Reaction Mix: 10 μL 2x HRM Master Mix

- Primers: 0.5 μL each (10 μM)

- DNA Template: 2 μL (5-20 ng/μL)

- Total Volume: 20 μL with nuclease-free water

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Activation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- Amplification (40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute

- HRM Step:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Renaturation: 60°C for 1 minute

- Melting: 60°C to 95°C with 0.1°C/s ramp rate

Genotype Calling

- Analyze normalized melting curves

- Use cluster analysis to group samples by genotype

- Assign species based on reference genotype profiles

- Apply threshold (typically >95% probability) for species assignment

HRM Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in HRM analysis from sample collection to result interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for HRM Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Products/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Saturating DNA Dye | Fluorescent detection of dsDNA during melting | EvaGreen, SYTO9, LCGreen PLUS |

| HRM Master Mix | Optimized buffer system for amplification and melting | HOT FIREPol EvaGreen HRM Mix, Type-It HRM PCR Kit |

| Species-Specific Primers | Target amplification with discrimination capability | Custom-designed primers (10-20 bp, Tm ~60°C) |

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality DNA isolation from various samples | Qiagen DNA Mini Kit, Favorgen DNA Extraction Kit |

| Positive Controls | Reference samples for melting curve comparison | Genomic DNA from target species/variants |

| Optical Plates/Stripes | Reaction vessels compatible with HRM instruments | White/clear 96-well plates with optical seals |

| Quantitation Standard | DNA concentration measurement | NanoDrop spectrophotometer, Qubit dsDNA HS assay |

Method Validation and Quality Assurance

Robust validation is essential for implementing HRM assays in research and diagnostic settings. Key performance parameters must be established to ensure reliable genotype discrimination.

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

The limit of detection (LOD) should be determined using serial dilutions of target DNA. For multiplex HRM assays, LOD typically ranges from 4-10 copies/reaction for each target [29]. Specificity must be verified against closely related non-target species and potential cross-reactants. The mussel authentication assay demonstrated zero false-positive and false-negative rates through extensive validation [28].

Repeatability and Reproducibility

Intra-assay and inter-assay variability should be assessed using multiple replicates across different runs. Coefficients of variation for Tm values are typically below 2% for well-optimized assays [29]. Inter-laboratory transferability strengthens validation, as demonstrated by the "almost perfect agreement" (κ = 0.925, p < 0.001) achieved for the mussel identification assay across different laboratories [28].

Robustness Testing

Assay performance should be evaluated under varying conditions, including:

- DNA quality and concentration

- Annealing temperature and time variations

- Primer concentration fluctuations

- Different reaction volumes

- Various HRM kit lots

The mussel identification method demonstrated robustness against all these variables, maintaining accurate species identification across conditions [28].

HRM Validation Parameters: This diagram outlines the key validation components required for implementing robust HRM assays in research and diagnostic settings.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Successful implementation of HRM analysis requires addressing several technical challenges that may impact assay performance and result interpretation.

Common Issues and Solutions

- Poor Curve Separation: Optimize amplicon design to increase Tm differences; target regions with higher GC content variation; reduce amplicon length for sharper transitions.

- Low Sensitivity: Verify DNA quality and concentration; optimize primer concentrations; increase cycle number for low-abundance targets; include PCR enhancers if needed.

- Irreproducible Melting Profiles: Standardize DNA extraction methods; ensure consistent thermal cycling conditions; use fresh dye preparations; verify instrument calibration.

- Non-Specific Amplification: Redesign primers with stricter parameters; optimize annealing temperature using gradient PCR; incorporate touchdown PCR protocols; increase stringency with additives like DMSO or betaine.

Multiplex Assay Optimization

For multiplex HRM applications, careful balancing of primer concentrations is essential to ensure uniform amplification of all targets. Primer pairs should be tested individually before combining, with adjustments made to concentrations to achieve balanced amplification [31]. The annealing temperature should be optimized to work efficiently with all primer sets, potentially requiring compromise between ideal temperatures for individual assays.

Cross-Platform Compatibility

HRM results may vary between different real-time PCR instruments due to differences in thermal uniformity, optical detection systems, and data collection algorithms [29]. When transferring methods between platforms, re-optimization may be necessary, and platform-specific Tm value ranges should be established. For clinical applications, establish confidence intervals for melting points that include at least 90% of observed melting points for each variant [32].

High-Resolution Melting analysis represents a versatile, robust, and cost-effective technology for genotype discrimination and species identification in multiplex PCR assays. Its closed-tube nature, minimal reagent requirements, and rapid turnaround time make it particularly valuable for high-throughput applications across diverse research fields. The continuing refinement of HRM methodologies, coupled with advances in real-time PCR instrumentation and saturating DNA dyes, promises to further expand its applications in both basic research and diagnostic settings. As evidenced by the successful implementations across microbiology, food authentication, and parasitology, HRM analysis has established itself as an indispensable tool in the molecular researcher's toolkit for high-resolution subtyping research.

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a powerful molecular biology technique that enables the simultaneous amplification of multiple target DNA sequences in a single reaction tube. By incorporating multiple primer sets specific to different DNA targets, this method allows researchers to gain more information from limited starting materials, making it substantially more cost-effective and time-efficient than performing multiple uniplex PCR reactions [34] [35]. First described in 1988 for detecting deletion mutations in the dystrophin gene, multiplex PCR has evolved into an indispensable tool for applications ranging from pathogen identification and genotyping to mutation analysis and forensic studies [34] [35].

The technique is particularly valuable in high-resolution subtyping research, where distinguishing between closely related pathogens or genetic variants is essential. For instance, during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, real-time PCR multiplex assays were designed to increase diagnostic capabilities by combining multiple gene targets into a single reaction [34]. The success of multiplex PCR hinges on careful experimental design, particularly in primer selection and reaction optimization, to ensure uniform amplification of all targets while minimizing unwanted interactions between the numerous primer pairs sharing the same reaction environment [36].

Multiplex PCR Primer Design

Fundamental Principles and Parameters

The design of specific primer sets is the most critical factor determining the success of a multiplex PCR reaction. Effective primer design must balance several competing parameters to ensure all primers function harmoniously under a single set of reaction conditions [36]. The key considerations for multiplex primer design include:

- Primer Length: Primers are typically 18-22 bases long, providing an optimal balance between specificity and binding efficiency [34] [35].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Primers should have similar Tm values, preferably between 55°C-60°C. For sequences with high GC content, primers with a higher Tm (75°C-80°C) may be required. A Tm variation of 3°C-5°C between primers is generally acceptable [35].

- Specificity: Primers must be highly specific to their intended targets to avoid cross-hybridization, especially given the competition when multiple target sequences are present in a single reaction [35].

- Dimer Formation: Primers should be checked for potential dimer formation with all other primers in the reaction mixture. Primer dimers consist of two primer molecules that hybridize to each other and can be amplified by DNA polymerase, competing for reagents and potentially inhibiting target DNA amplification [34].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Multiplex PCR Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-22 bases | Balances specificity and binding efficiency |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55-60°C (standard); 75-80°C (high GC content) | Ensures all primers function at common annealing temperature |

| GC Content | 25-75% | Prevents overly stable or unstable hybrids |

| Amplicon Size | Varying lengths (e.g., 100-500 bp) | Allows clear differentiation by electrophoresis |

| ΔG° of Binding | -10.5 to -12.5 kcal/mol | Optimizes amplification efficiency and uniformity |

Advanced Computational Design Approaches

As the level of multiplexing increases, the complexity of primer design grows exponentially. For highly multiplexed panels, manual primer design becomes impractical, necessitating sophisticated computational approaches. The number of potential primer dimer interactions grows quadratically with the number of primers, while the sequence selection choices grow exponentially [37].

The Simulated Annealing Design using Dimer Likelihood Estimation (SADDLE) algorithm represents a significant advancement in highly multiplexed primer design. This stochastic algorithm systematically minimizes primer dimer formation by evaluating a loss function that estimates the severity of primer dimer interactions across the entire primer set [37]. In practice, SADDLE has demonstrated remarkable efficacy, reducing the fraction of primer dimers from 90.7% in a naively designed 96-plex primer set (192 primers) to just 4.9% in an optimized set. The approach remains effective even when scaling to 384-plex (768 primers) reactions [37].

Specialized software tools like PrimerPlex and FastPCR incorporate these principles to facilitate multiplex primer design. These programs automatically check oligos for cross-reactivity, minimize Tm mismatches, and identify compatible primer sets from millions of possible combinations [35] [38]. FastPCR can calculate multiplex PCR primer pairs for given target sequences or different targets inside a sequence, with the speed of calculation depending on the amount of target sequence and primer pairs required [38].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Reaction Setup and Optimization

Establishing a robust multiplex PCR protocol requires careful optimization of several reaction components. The following protocol provides a general framework that can be adapted for specific applications:

Table 2: Typical Multiplex PCR Reaction Components

| Component | Final Concentration | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Buffer | 1X | May require optimization of salt concentrations |

| MgCl₂ | 1.5-4.0 mM | Must be balanced with dNTP concentration |

| dNTPs | 200-400 µM each | Concentration proportional to MgCl₂ |

| Primers | 0.1-1.0 µM each | Often requires individual concentration optimization |

| DNA Polymerase | 0.5-2.5 U/µL | Use enzymes validated for multiplex applications |

| Template DNA | 1-100 ng | Quality and quantity affect amplification efficiency |

| BSA or Betaine | Optional | Can improve amplification of GC-rich targets |

A standardized thermal cycling protocol for multiplex PCR includes:

- Initial Denaturation: 94-95°C for 2-5 minutes

- Amplification Cycles (30-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94-95°C for 30-60 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C for 30-90 seconds (requires optimization)

- Extension: 72°C for 60-90 seconds (adjust based on amplicon size)

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Hold: 4-10°C indefinitely [39] [36]

The annealing temperature is particularly critical and must be optimized to ensure specific binding of all primer pairs. Gradient PCR is recommended during optimization to identify the temperature that provides the best balance of specificity and efficiency for all targets [36].

Multiplex qPCR and Advanced Detection Methods

Multiplex quantitative PCR (qPCR) extends the capabilities of conventional multiplex PCR by enabling real-time detection and quantification of multiple targets. In multiplex qPCR, two or more target genes are amplified in the same reaction using the same reagent mix, with each target detected using probes labeled with distinct fluorescent dyes [40].

The simplest and most common form is duplexing, where two genes are amplified in a single reaction. With careful optimization, it is possible to measure the expression of three or four genes simultaneously, providing substantial savings in cost, reagents, and time [40]. Successful multiplex qPCR requires:

- Selection of dyes with minimal spectral overlap (e.g., FAM, VIC, ABY, JUN)

- Matching dye intensity with target abundance (brightest dyes with low-abundance targets)

- Using master mixes specifically formulated for multiplex applications

- Potential implementation of primer limitation for highly abundant targets [40]

Fluorescence Melting Curve Analysis (FMCA) has emerged as a versatile detection method for multiplex PCR. This technique leverages the unique melting temperatures (Tm) of specific hybridization probes bound to their complementary DNA sequences to differentiate between multiple pathogens in a single reaction tube [41]. Recent advancements have demonstrated FMCA-based multiplex assays capable of simultaneously detecting six respiratory pathogens with limits of detection between 4.94 and 14.03 copies/μL and exceptional precision (intra-/inter-assay CVs ≤ 0.70% and ≤ 0.50%) [41].

Multiplex PCR Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for multiplex PCR experiments, from initial primer design through reaction optimization to final amplification and analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of multiplex PCR requires careful selection of reagents and specialized kits designed to address the unique challenges of amplifying multiple targets simultaneously. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions for multiplex PCR applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex PCR

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR Kits (e.g., Qiagen, Agilent) | Pre-optimized master mixes with enhanced specificity | Qiagen's kit works with up to 16 primer pairs; Agilent's hybrid capture amplifies >100 fragments [34] |

| Specialized DNA Polymerases | Engineered for robust amplification in multiplex conditions | Reduced primer dimer formation; improved processivity |

| dNTP Mixes | Balanced nucleotides for efficient incorporation | Prevents biased amplification of certain targets |

| MgCl₂ Solutions | Cofactor for DNA polymerase activity | Concentration must be balanced with dNTPs [36] |

| PCR Additives (BSA, Betaine, DMSO) | Enhance amplification efficiency | Reduce secondary structure; improve GC-rich target amplification [36] |

| Multiplex qPCR Master Mixes | Optimized for real-time multiplex detection | Contains passive reference dyes; balanced for multiple probe types [40] |

| Fluorescent Probes/Dyes (FAM, VIC, ABY, JUN) | Enable multiplex detection in real-time PCR | Distinct emission spectra allow target discrimination [40] |

Commercial multiplex PCR kits provide significant advantages for researchers, as they typically include pre-optimized reaction components and validated primer sets for specific applications. These ready-to-use solutions can dramatically reduce development time and improve reproducibility. For instance, Qiagen's multiplex PCR kit is useful for typing transgenic organisms or microsatellite analysis, while Agilent has optimized a hybrid capture-based target enrichment approach that amplifies more than 100 fragments simultaneously [34].

For qPCR applications, TaqMan Multiplex Master Mix, TaqPath 1-Step Multiplex Master Mix, and TaqPath ProAmp Master Mixes are all specifically optimized for multiplexing reactions. These formulations typically include Mustang Purple dye as a passive reference dye instead of ROX to accommodate the use of JUN dye in high-level multiplexing [40].

Applications in High-Resolution Subtyping Research

Multiplex PCR has proven particularly valuable in high-resolution subtyping research, where distinguishing between closely related pathogens or genetic variants is essential for both clinical management and public health surveillance. The technique's ability to simultaneously detect multiple targets in a single reaction makes it ideal for comprehensive pathogen identification and characterization.

In respiratory virus surveillance, a multiplex reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method has been developed that can detect and subtype influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and B viruses as well as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B in clinical samples. This approach enables the differentiation of five distinct amplification products of different sizes on agarose gels, providing critical information for epidemiological monitoring and vaccine development [3]. More recently, FMCA-based multiplex PCR assays have been designed to simultaneously detect six respiratory pathogens (SARS-CoV-2, influenza A and B, RSV, adenovirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae), demonstrating 98.81% agreement with reference methods in clinical validation studies [41].

In food safety applications, a rapid multiplex real-time PCR high-resolution melt curve assay has been developed for the simultaneous detection of Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus in food matrices. The assay successfully distinguishes these pathogens based on their distinct melting temperatures (76.23°C, 80.19°C, and 74.01°C, respectively), providing an efficient tool for food safety monitoring [42].

For bacterial subtyping, multiplex PCR assays have been developed to detect CRISPR-Cas subtypes I-F1 and I-F2 in Acinetobacter baumannii, an important ESKAPE pathogen. This method achieved a 100% detection rate for isolates containing these Cas subtypes, providing a valuable tool for monitoring CRISPR-Cas systems and developing novel strategies to manage multidrug-resistant A. baumannii [39].

Multiplex PCR Challenges and Solutions: This diagram illustrates common challenges in multiplex PCR experiments and corresponding optimization strategies to address them.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Despite careful planning, multiplex PCR assays often require extensive optimization to achieve balanced amplification of all targets. Common challenges include spurious amplification products, uneven or no amplification of some target sequences, and difficulties in reproducing results [36].

Addressing Amplification Biases

Several factors can lead to preferential amplification of certain targets in multiplex reactions:

- Primer Concentration Optimization: The relative concentration of primers for each target often needs individual adjustment. While standard singleplex PCR typically uses primer concentrations of 900nM each, multiplex reactions may require reduction to 150nM for highly abundant targets to prevent them from dominating the reaction (primer limitation) [40].

- Magnesium Concentration: Magnesium chloride concentration needs to be proportional to the amount of dNTPs in the reaction. Increasing magnesium concentration can improve yields but may decrease specificity [36].

- Thermal Cycling Parameters: An optimal combination of annealing temperature and buffer concentration is essential. Gradient PCR is recommended to determine the optimal annealing temperature that provides specific amplification for all targets [36].

- Template Quality and Quantity: The quality of the template may be determined more effectively in multiplex than in simple PCR reactions. Degraded templates may show preferential amplification of smaller targets [35].

Validation and Quality Control

Rigorous validation is essential for any new multiplex PCR procedure. The sensitivity and specificity must be thoroughly evaluated using standardized purified nucleic acids [36]. Validation should include:

- Comparison with singleplex reactions to ensure multiplexing doesn't alter Ct values

- Assessment of precision (intra- and inter-assay variability)

- Evaluation of limits of detection for each target

- Testing against panels of non-target organisms to confirm specificity

Where available, full use should be made of external and internal quality controls, which must be rigorously applied. For clinical applications, this is particularly important to ensure reliable results that can inform patient management decisions [36].

Multiplex PCR represents a powerful approach for high-throughput genetic analysis in research and diagnostic settings. While the development of robust multiplex assays requires significant optimization, the benefits in terms of efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and comprehensive data generation make it an indispensable tool in modern molecular biology. As computational design methods continue to advance and reagent formulations improve, the scalability and applications of multiplex PCR will undoubtedly expand, further solidifying its role in high-resolution subtyping research and beyond.

The detection and identification of foodborne pathogens represent a critical challenge in ensuring food safety. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) constitutes a group of foodborne pathogens that pose a significant threat to both food safety and human health, with milk and dairy products serving as potential transmission vehicles [2]. Traditional methods for subtyping DEC are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require multiple separate reactions, presenting challenges for laboratories handling large sample volumes.

This application note details a case study utilizing an innovative method that combines multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis to subtype five major DEC pathotypes in a single reaction well directly from milk samples [2] [43]. This methodology aligns with the broader thesis that advanced multiplex PCR assays provide powerful tools for high-resolution subtyping in microbiological research, offering streamlined procedures, reduced detection time, and enhanced reliability for food safety testing.