High-Content Imaging in Phenotypic Screening: A Chemogenomic Approach to Modern Drug Discovery

This article explores the integration of high-content imaging (HCI) and chemogenomic libraries in phenotypic screening, a powerful strategy revitalizing drug discovery.

High-Content Imaging in Phenotypic Screening: A Chemogenomic Approach to Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the integration of high-content imaging (HCI) and chemogenomic libraries in phenotypic screening, a powerful strategy revitalizing drug discovery. It covers the foundational principles of this synergy, detailing how annotated chemical libraries help deconvolute mechanisms of action from complex phenotypic readouts. We provide a comprehensive guide to methodological workflows, from live-cell multiplexed assays to automated image analysis using tools like CellProfiler and machine learning. The article further addresses critical troubleshooting for assay optimization and data quality control, and examines statistical frameworks for phenotypic validation and hit prioritization. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource outlines how these technologies are reducing attrition rates by enabling the early identification of specific, efficacious, and safe therapeutic candidates.

The Synergy of Chemogenomics and Phenotypic Screening: Foundations for Target-Agnostic Discovery

Resurgence of Phenotypic Screening in Modern Drug Discovery

Phenotypic drug discovery (PDD), an approach based on observing the effects of compounds in biologically relevant systems without a pre-specified molecular target, is experiencing a major resurgence in modern pharmaceutical research. After decades of dominance by target-based drug discovery (TDD), the paradigm has shifted back toward phenotypic screening following a surprising observation: between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class medicines were discovered empirically without a specific target hypothesis [1]. This renaissance is not merely a return to historical methods but represents a fundamental evolution, combining the original concept with sophisticated modern tools including high-content imaging, functional genomics, artificial intelligence, and advanced disease models [2] [3]. The modern incarnation of PDD uses these technologies to systematically pursue drug discovery based on therapeutic effects in realistic disease models, enabling the identification of novel mechanisms of action and expansion of druggable target space [1].

The strategic advantage of phenotypic screening lies in its capacity to identify compounds that produce therapeutic effects in disease-relevant models without requiring complete understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms beforehand. This approach has proven particularly valuable for complex diseases where validated molecular targets are lacking or the disease biology is insufficiently understood [1]. As noted by Fabien Vincent, an Associate Research Fellow at Pfizer, "If we start testing compounds in cells that closely represent the disease, rather than focusing on one single target, then odds for success may be improved when the eventual candidate compound is tested in patients" [3]. This biology-first strategy has led to breakthrough therapies across multiple therapeutic areas, reinvigorating interest in phenotypic approaches throughout both academia and the pharmaceutical industry.

Technological Drivers of the Phenotypic Screening Renaissance

High-Content Imaging and Analysis

High-content imaging (HCI) transforms fluorescence microscopy into a high-throughput, quantitative tool for investigating spatial and temporal aspects of cell biology [4]. This technology combines automated microscopy with sophisticated image processing and data analysis to extract rich multiparametric information from cellular samples. The foundational element of high-content analysis is segmentation—the computational identification of specific cellular elements—which is typically achieved using fluorescent dyes that label nuclei (e.g., HCS NuclearMask stains), cytoplasm (e.g., HCS CellMask stains), or plasma membranes [4].

The market for high-content screening is projected to grow from $3.1 billion in 2023 to $5.1 billion by 2029, reflecting its expanding role in drug discovery [5]. This growth is fueled by several technological advancements:

- High-resolution fluorescence microscopy: Systems like the ImageXpress Micro Confocal enable high-speed, automated imaging of cellular structures with remarkable clarity [5].

- Live-cell imaging: Technologies such as the Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System allow continuous monitoring of cell behavior over extended periods, capturing dynamic biological processes [5].

- 3D cell culture and organoid screening: Platforms using Nunclon Sphera Plates facilitate the formation of 3D spheroids and organoids that better recapitulate tissue physiology [5].

- Advanced image processing software: AI-powered solutions like Harmony Software enhance cell segmentation, feature extraction, and multivariate analysis [5].

AI and Multi-Omics Integration

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have become indispensable for interpreting the massive, complex datasets generated by phenotypic screening [2]. AI/ML models enable the fusion of multimodal data sources—including high-content imaging, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—that were previously too heterogeneous to analyze in an integrated manner [2]. Deep learning approaches can detect subtle, disease-relevant patterns in high-dimensional data that escape conventional analysis methods.

Multi-omics integration provides crucial biological context to phenotypic observations. Each omics layer reveals different aspects of cellular physiology: transcriptomics captures active gene expression patterns; proteomics clarifies signaling and post-translational modifications; metabolomics contextualizes stress response and disease mechanisms; and epigenomics gives insights into regulatory modifications [2]. The integration of these diverse data dimensions enables a systems-level view of biological mechanisms that single-omics analyses cannot detect, significantly improving prediction accuracy, target selection, and disease subtyping for precision medicine applications [2].

Functional Genomics and Chemogenomics

Chemogenomics represents a powerful framework for phenotypic discovery that systematically explores the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems. This approach uses targeted compound libraries designed to perturb specific protein families or pathways, enabling mechanistic follow-up from phenotypic observations [6]. Recent methodologies in this field include:

- NanoBRET live-cell kinase selectivity profiling: Adapted for high-throughput screening, this technology enables real-time assessment of kinase engagement in live cells [6].

- HiBiT Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (HiBiT CETSA): A modern target engagement method that monitors compound-induced protein stabilization or destabilization in cellular contexts [6].

- CRISPR-based functional screening: Enables genome-wide or focused interrogation of gene function through precise gene editing, facilitating the identification of mechanisms underlying phenotypic observations [5].

These approaches are particularly valuable for deconvoluting the mechanisms of action of phenotypic hits, historically one of the most significant challenges in PDD.

Table 1: Key Technology Platforms Enabling Modern Phenotypic Screening

| Technology Category | Representative Platforms | Key Applications in PDD |

|---|---|---|

| High-Content Imaging Systems | ImageXpress Micro Confocal, CellInsight CX7 LZR, CellVoyager CQ1 | Multiparametric analysis of cell morphology, subcellular localization, and temporal dynamics |

| Live-Cell Analysis | Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System | Long-term monitoring of phenotypic changes, cell migration, proliferation, and death |

| 3D Model Systems | Nunclon Sphera Plates, organoid platforms | Physiologically relevant screening in tissue-like contexts |

| AI/Image Analysis | Harmony Software, PhenAID platform, HCS Studio | Automated feature extraction, pattern recognition, and multivariate analysis |

| Functional Genomics | CRISPR libraries, Chemogenomic sets | Target identification and validation, mechanism of action studies |

Methodological Framework: Implementing Phenotypic Screening

Experimental Design and Workflow

A robust phenotypic screening workflow incorporates multiple stages from assay development through hit validation. The critical first step involves selecting or developing biologically relevant models that faithfully recapitulate disease pathophysiology. Modern approaches emphasize human-based systems, including patient-derived cells, iPSC-derived models, and increasingly complex 3D systems such as organoids and microphysiological systems [7] [3].

The implementation of a phenotypic screening campaign follows a structured workflow that ensures the identification of biologically meaningful hits:

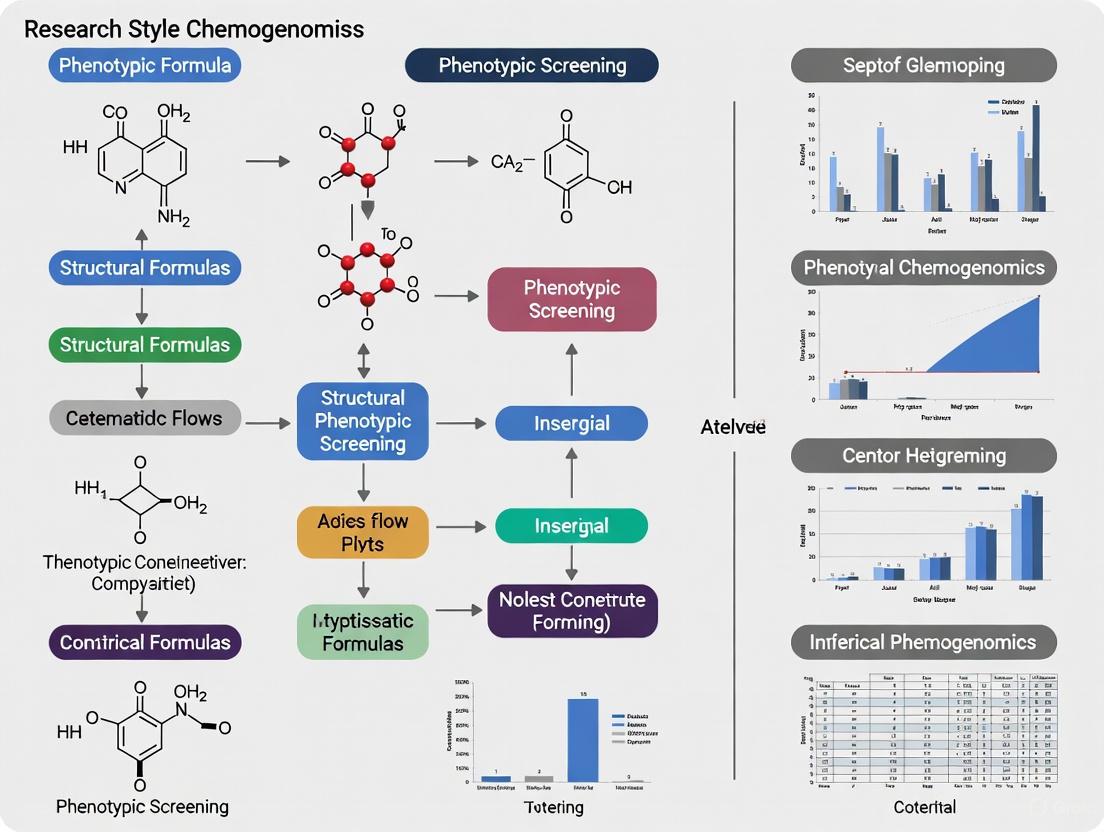

Diagram 1: Phenotypic Screening Workflow

Core Assay Protocols

Multiparametric Cell Health and Cytotoxicity Assessment

This protocol provides a comprehensive assessment of compound effects on fundamental cellular processes, enabling early identification of cytotoxic or nuisance compounds [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell type relevant to disease biology (e.g., primary cells, iPSC-derived cells)

- Invitrogen HCS Mitochondrial Health Kit

- Invitrogen CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent

- HCS NuclearMask Blue stain (Hoechst 33342)

- Cell culture medium appropriate for selected cell type

- Compound library dissolved in DMSO with concentration ≤0.1%

Procedure:

- Plate cells in 96-well or 384-well microplates at optimized density and culture for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with compound library for desired exposure time (typically 24-72 hours).

- Prepare staining solution containing:

- 1:1000 dilution of HCS NuclearMask Blue stain (cell number reference)

- 1:500 dilution of mitochondrial membrane potential dye (from HCS Mitochondrial Health Kit)

- 1:1000 dilution of CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent

- 1:2000 dilution of viability dye (from HCS Mitochondrial Health Kit)

- Replace compound-containing medium with staining solution and incubate for 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

- Image plates using high-content imager with appropriate filters:

- Nuclear stain: DAPI channel (ex350/em461)

- Mitochondrial potential: TRITC channel (ex555/em576)

- Caspase 3/7: FITC channel (ex492/em517)

- Viability dye: Cy5 channel (ex650/em668)

- Analyze images using integrated morphometric analysis including:

- Cell count and confluence from nuclear channel

- Mitochondrial membrane potential intensity per cell

- Caspase 3/7 activation (percentage of positive cells)

- Viability (percentage of viable cells)

High-Content Autophagy Flux Analysis

This protocol enables quantitative assessment of autophagic activity through measurement of LC3B-positive puncta formation, a key marker of autophagosomes [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Appropriate cell line (U2OS or disease-relevant cells)

- Anti-LC3B antibody

- Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody

- Hoechst 33342 for nuclear counterstaining

- Autophagy modulators (e.g., chloroquine for flux inhibition, PP242 for mTOR-dependent induction)

- Permeabilization and blocking buffers

Procedure:

- Plate cells in 96-well microplates and culture until 70-80% confluent.

- Treat cells with test compounds alone or in combination with chloroquine (20 μM) for 4-24 hours.

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Block with 5% BSA in PBS for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary anti-LC3B antibody (1:500) overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Counterstain nuclei with Hoechst 33342 (1:1000) for 10 minutes.

- Image plates using high-content imager with 40x objective.

- Quantify LC3B-positive puncta using spot detection algorithm:

- Identify nuclei using Hoechst channel

- Define cytoplasmic region based on nuclear expansion

- Detect and count LC3B-positive puncta within cytoplasmic region

- Normalize puncta count to cell number

Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function in Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Stains | HCS NuclearMask Blue stain, Hoechst 33342 | Cell segmentation, nuclear morphology analysis, cell counting |

| Cytoplasmic & Plasma Membrane Stains | HCS CellMask stains, CellMask Plasma Membrane stains | Cytoplasmic segmentation, cell shape analysis, membrane integrity assessment |

| Viability and Cytotoxicity Reagents | LIVE/DEAD reagents, HCS Mitochondrial Health Kit | Multiparametric assessment of cell health, mitochondrial function, and viability |

| Apoptosis Detection | CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent | Early apoptosis detection through caspase activation monitoring |

| Phenotypic Perturbation Tools | CRISPR libraries, Chemogenomic compound sets | Targeted pathway perturbation for mechanism investigation |

| Cell Line Models | Patient-derived cells, iPSC-differentiated cells, 3D organoid cultures | Biologically relevant systems for disease modeling |

Success Stories: Phenotypic Screening in Action

Cystic Fibrosis Modulators

The development of transformative therapies for cystic fibrosis (CF) stands as a landmark achievement of modern phenotypic screening. CF is caused by mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that decrease CFTR function or disrupt intracellular folding and membrane insertion [1]. Target-agnostic compound screens using cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants identified multiple compound classes with unexpected mechanisms of action:

- Potentiators such as ivacaftor that improve CFTR channel gating properties

- Correctors including tezacaftor and elexacaftor that enhance CFTR folding and plasma membrane insertion [1]

The combination therapy elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor, approved in 2019, addresses 90% of the CF patient population and originated directly from phenotypic screening approaches [1]. Pfizer's cystic fibrosis program further exemplifies this approach, using patient-derived cells to identify "compounds that can re-establish the thin film of liquid" critical for proper lung function, providing confidence that these compounds would perform similarly in patients [3].

Spinal Muscular Atrophy Therapeutics

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 1 is a rare neuromuscular disease with historically high mortality. SMA is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SMN1 gene, but humans possess a closely related SMN2 gene that predominantly produces an unstable shorter SMN variant due to a splicing mutation [1]. Phenotypic screens independently conducted by two research groups identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase levels of functional full-length SMN protein [1].

The resulting compound, risdiplam, was approved by the FDA in 2020 as the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA. Both risdiplam and the related compound branaplam function through an unprecedented mechanism—they bind two sites at SMN2 exon 7 and stabilize the U1 snRNP complex, representing both a novel drug target and mechanism of action [1] [1]. This case exemplifies how phenotypic strategies can expand "druggable target space" to include previously unexplored cellular processes like pre-mRNA splicing.

Novel Anticancer Mechanisms

Phenotypic screening has revealed multiple innovative anticancer mechanisms with clinical potential:

Lenalidomide: Originally discovered through phenotypic observations of thalidomide's efficacy in leprosy and multiple myeloma, lenalidomide's molecular target and mechanism were only elucidated several years post-approval. The drug binds to the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cereblon and redirects its substrate specificity to promote degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 [1]. This novel mechanism has spawned an entirely new class of therapeutics—targeted protein degraders including 'bifunctional molecular glues' [1].

ARCHEMY Phenotypic Platform: This AI-powered approach identified AMG900 and novel invasion inhibitors in lung cancer using patient-derived phenotypic data integrated with multi-omics information [2].

idTRAX Machine Learning Platform: This platform has been used to identify cancer-selective targets in triple-negative breast cancer, demonstrating how computational approaches can enhance phenotypic screening [2].

Integrated Data Analysis and Target Deconvolution

Chemogenomics and Mechanism of Action Studies

The integration of chemogenomics—the systematic study of compound-target interactions across entire gene families—has dramatically improved our ability to deconvolute mechanisms of action from phenotypic screens [6]. This approach uses targeted compound libraries with known activity against specific protein families to create phenotypic signatures that can be compared against phenotypic screening hits.

The process of phenotypic screening data analysis and target identification involves multiple integrated steps:

Diagram 2: Target Deconvolution Workflow

Modern computational approaches are increasingly powerful for predicting mechanisms directly from phenotypic data. For example, MorphDiff—a transcriptome-guided latent diffusion model—accurately predicts cell morphological responses to perturbations, enhancing mechanism of action identification and phenotypic drug discovery [8]. Similarly, deep metric learning approaches have been used to characterize 650 neuroactive compounds by zebrafish behavioral profiles, successfully identifying compounds acting on the same human receptors as structurally dissimilar drugs [8].

AI-Enhanced Phenotypic Profiling

Artificial intelligence has transformed phenotypic data analysis through several key applications:

Morphological Profiling: AI algorithms such as those employed in the PhenAID platform can detect subtle phenotypic patterns that correlate with mechanism of action, efficacy, or safety [2]. These systems use high-content data from assays like Cell Painting, which visualizes multiple cellular components, to generate quantitative profiles that enable comparison of phenotypic effects across compound libraries.

Predictive Modeling: Tools like IntelliGenes and ExPDrug exemplify how AI platforms make integrative discovery accessible to non-experts, enabling prediction of drug response and biomarker identification [2]. These systems can integrate heterogeneous data sources including electronic health records, imaging, multi-omics, and sensor data into unified models [2].

Hit Triage and Prioritization: AI approaches help address key challenges in phenotypic screening by enabling more efficient processing and prioritization of hits, thereby reducing progression of poorly qualified leads and preventing advancement of compounds with undesirable mechanisms [7].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Emerging Trends and Opportunities

The future of phenotypic drug discovery will be shaped by several converging technological trends:

Advanced Human Cell Models: The development of more physiologically relevant models, including microphysiological systems (organ-on-a-chip), advanced organoids, and patient-derived cells, will enhance the translational predictive power of phenotypic screening [7] [3]. As noted by Pfizer researchers, "We really need to make sure that these cell models are of high value and not just some random cell line. We need to find a way to recreate the disease in a microplate" [3].

Integration with Functional Genomics: Combining phenotypic screening with CRISPR-based functional genomics enables systematic investigation of gene function alongside compound screening, facilitating immediate follow-up on interesting phenotypes [5].

AI and Automation Convergence: The marriage of advanced AI algorithms with fully automated screening systems will enable increasingly sophisticated experimental designs and analyses, potentially allowing for continuous adaptive screening approaches [2] [5].

Expansion of Druggable Target Space: Phenotypic screening continues to reveal novel therapeutic mechanisms, as exemplified by the recent discovery of molecular glue degraders that redirect E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [8]. A high-throughput proteomics platform has revealed "a much larger cereblon neosubstrate space than initially thought," suggesting substantial untapped potential for targeting previously undruggable proteins [8].

Ongoing Challenges and Resolution Strategies

Despite considerable advances, phenotypic screening still faces significant challenges that require continued methodological development:

Target Identification: Mechanism deconvolution remains difficult, though increasingly addressed through integrated approaches combining chemogenomics, functional genomics, and computational methods [1] [6].

Data Heterogeneity and Complexity: The multidimensional data generated by modern phenotypic screening creates analytical challenges. Efforts to establish standardized phenotypic metrics and data sharing frameworks are addressing these issues [2].

Translation to Clinical Success: While phenotypic screening has generated notable successes, ensuring consistent translation to clinical outcomes requires careful attention to assay design and biological relevance throughout the discovery process [7].

Resource Intensity: Modern phenotypic screening remains resource-intensive, though advances in compressed phenotypic screens using pooled perturbations with computational deconvolution are dramatically reducing sample size, labor, and cost requirements while maintaining information-rich outputs [2].

As these challenges are addressed through continued methodological innovation, phenotypic screening is poised to become an increasingly central approach in drug discovery, particularly for complex diseases and those without validated molecular targets. The integration of phenotypic strategies with target-based approaches represents a powerful balanced strategy for identifying first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action.

The drug discovery paradigm has significantly evolved, shifting from a reductionist "one target—one drug" vision to a more complex systems pharmacology perspective that acknowledges a single drug often interacts with several targets [9]. This shift is partly driven by the recognition that complex diseases like cancers, neurological disorders, and diabetes are frequently caused by multiple molecular abnormalities rather than a single defect [9]. Within this context, phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful approach for identifying novel therapeutic agents based on their observable effects on cells or tissues, without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [9]. Advanced technologies in cell-based phenotypic screening, including the development of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell technologies, gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas, and high-content imaging assays, have been instrumental in this PDD resurgence [9].

However, a significant challenge remains: while phenotypic screening can identify compounds that produce desirable effects, it does not automatically reveal the specific protein targets or mechanisms of action (MoA) responsible for those effects [9]. This "target identification gap" can hinder the rational optimization of hit compounds and their development into viable drug candidates. Chemogenomic libraries have emerged as a strategic solution to this problem. These are carefully curated collections of small molecules—including known drugs, chemical probes, and inhibitors—with annotated activities against specific biological targets [10] [11]. By screening these target-annotated libraries in phenotypic assays, researchers can directly link observed phenotypes to potential molecular targets, effectively bridging the critical gap between phenotypic observation and target identification.

Chemogenomic Libraries: Design, Composition, and Integration with Phenotypic Profiling

Library Design Strategies and Core Characteristics

The construction of a high-quality chemogenomic library is a deliberate process that prioritizes target coverage, cellular potency, and chemical diversity over sheer library size [10]. Design strategies often involve a multi-objective optimization approach to maximize the coverage of biologically relevant targets while minimizing redundancy and eliminating compounds with undesirable properties [10].

Two primary design strategies are commonly employed:

- Target-Based Approach: This method starts with a defined set of proteins implicated in disease and identifies small molecule inhibitors or modulators for those targets. This yields collections of experimental probe compounds (EPCs) that are often in preclinical stages [10].

- Drug-Based Approach: This complementary strategy begins with clinically used compounds, including approved drugs and those in advanced clinical development, to create an approved and investigational compounds (AIC) collection. This set is particularly valuable for drug repurposing applications [10].

A key application of these libraries involves integrating them with high-content morphological profiling. Assays like the Cell Painting assay provide a powerful method for characterizing compound effects [9]. In this assay, cells are stained with fluorescent dyes targeting major cellular compartments, imaged via high-throughput microscopy, and then analyzed computationally to extract hundreds of morphological features [9]. This generates a detailed "morphological profile" for each compound, creating a fingerprint that can connect unknown compounds to annotated ones based on profile similarity [9].

The table below summarizes key characteristics of several chemogenomic library designs as reported in recent scientific literature:

Table 1: Composition and Target Coverage of Representative Chemogenomic Libraries

| Library Name / Study | Final Compound Count | Target Coverage | Key Design Criteria | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System Pharmacology Network Library [9] | ~5,000 | Large panel of drug targets involved in diverse biological effects and diseases | Scaffold diversity, integration with Cell Painting data, target-pathway-disease relationships | General phenotypic screening and target deconvolution |

| Comprehensive anti-Cancer small-Compound Library (C3L) - Theoretical Set [10] | 336,758 | 1,655 cancer-associated proteins | Comprehensive coverage of cancer target space, includes mutant targets | In silico exploration of anticancer target space |

| C3L - Large-Scale Set [10] | 2,288 | 1,655 cancer-associated proteins | Activity and similarity filtering of theoretical set | Large-scale screening campaigns |

| C3L - Screening Set [10] | 1,211 | 1,386 anticancer proteins (84% coverage) | Cellular potency, commercial availability, target selectivity | Practical phenotypic screening in complex assays |

| EPC Collection (Typical) [10] | Varies | ~1,000-2,000 targets | High potency, selectivity, primarily preclinical compounds | Target discovery and validation |

| AIC Collection (Typical) [10] | Varies | Varies, focused on druggable genome | Clinical relevance, known safety profiles | Drug repurposing, probe development |

It is important to recognize that even the most comprehensive chemogenomic libraries interrogate only a fraction of the human genome—approximately 1,000–2,000 targets out of 20,000+ genes—highlighting both the progress and limitations of current chemical screening efforts [12].

Experimental Methodologies: From Library Assembly to Phenotypic Annotation

Protocol 1: Building a System Pharmacology Network for Phenotypic Screening

This protocol outlines the development of an integrated knowledge base that connects compounds to their targets, pathways, and associated disease biology, as described by [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for System Pharmacology Network Construction

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications/Version | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Version 22 (1,678,393 molecules, 11,224 unique targets) | Source of bioactivity data (Ki, IC50, EC50) and drug-target relationships [9] |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Release 94.1 (May 1, 2020) | Provides manually drawn pathway maps for molecular interactions and disease pathways [9] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Release 2020-05 (44,500+ GO terms) | Annotation of biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components [9] |

| Human Disease Ontology (DO) | Release 45 (v2018-09-10, 9,069 DOID terms) | Standardized classification of human disease terms and associations [9] |

| Cell Painting Morphological Data | BBBC022 dataset (20,000 compounds, 1,779 features) | Source of high-content morphological profiles for compound annotation [9] |

| ScaffoldHunter Software | Deterministic rule-based algorithm | Deconstruction of molecules into representative scaffolds and fragments for diversity analysis [9] |

| Neo4j Graph Database | NoSQL graph database platform | Integration of heterogeneous data sources into a unified network pharmacology model [9] |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Acquisition and Integration: Extract bioactivity data from ChEMBL, including compounds with at least one bioassay result (503,000 molecules). Integrate pathway context from KEGG, functional annotations from GO, and disease associations from the Disease Ontology [9].

Morphological Profiling Integration: Incorporate morphological data from the Cell Painting assay (BBBC022 dataset). Process the data by averaging feature values for compounds tested multiple times, retaining features with non-zero standard deviation and less than 95% correlation with other features [9].

Scaffold Analysis: Process each compound using ScaffoldHunter to systematically decompose molecules into core scaffolds and fragments through:

- Removal of all terminal side chains while preserving double bonds directly attached to rings.

- Sequential removal of one ring at a time using deterministic rules to identify characteristic core structures.

- Organization of scaffolds into different levels based on their hierarchical relationship to the original molecule [9].

Graph Database Construction: Implement the integrated data in a Neo4j graph database structure where nodes represent distinct entities (molecules, scaffolds, proteins, pathways, diseases) and edges define the relationships between them (e.g., "molecule targets protein," "target acts in pathway") [9].

Enrichment Analysis: Utilize R packages (clusterProfiler, DOSE) for GO, KEGG, and DO enrichment analyses to identify biologically relevant patterns, using Bonferroni adjustment method with a p-value cutoff of 0.1 [9].

Diagram 1: System Pharmacology Network Workflow

Protocol 2: HighVia Extend - A Multiplexed Live-Cell Assay for Comprehensive Compound Annotation

This protocol details a live-cell multiplexed assay designed to characterize the effects of chemogenomic library compounds on fundamental cellular functions, providing critical annotation of compound suitability for phenotypic screening [11].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HighVia Extend Live-Cell Assay

| Reagent | Working Concentration | Cellular Target/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst33342 | 50 nM | DNA/nuclear staining for cell count, viability, and nuclear morphology assessment [11] |

| BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye | Manufacturer's recommended concentration | Microtubules/tubulin network visualization for cytoskeletal integrity assessment [11] |

| MitotrackerRed | Manufacturer's recommended concentration | Mitochondrial mass and membrane potential indicator for health/toxicity assessment [11] |

| MitotrackerDeepRed | Manufacturer's recommended concentration | Additional mitochondrial parameter for extended kinetic profiling [11] |

| Reference Compounds (e.g., Camptothecin, Staurosporine, JQ1, Paclitaxel) | Varying concentrations based on IC50 | Assay validation and training set for machine learning classification [11] |

| Cell Lines (HeLa, U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9) | N/A | Representative cellular models for assessing compound effects across different genetic backgrounds [11] |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Dye Concentration Optimization: Titrate fluorescent dyes to determine the minimal concentration that provides robust detection without inducing cellular toxicity. For Hoechst33342, 50 nM was identified as optimal [11].

Cell Plating and Compound Treatment: Plate appropriate cell lines (e.g., U2OS, HEK293T, MRC9) in multiwell plates and allow adherence. Treat cells with reference compounds and chemogenomic library members across a range of concentrations [11].

Staining and Continuous Imaging: Simultaneously stain live cells with the optimized dye cocktail (Hoechst33342, BioTracker 488, MitotrackerRed, MitotrackerDeepRed). Initiate continuous imaging immediately after compound addition and continue at regular intervals over an extended period (e.g., 72 hours) [11].

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction: Use automated image analysis to identify individual cells and quantify morphological features related to:

- Nuclear morphology (size, shape, texture, intensity)

- Cytoskeletal structure

- Mitochondrial mass and distribution

- Overall cell count and viability [11]

Cell Population Classification: Employ a supervised machine-learning algorithm to categorize cells into distinct phenotypic classes based on the extracted features:

- Healthy

- Early apoptotic

- Late apoptotic

- Necrotic

- Lysed [11]

Kinetic Profile Generation: Analyze time-dependent changes in population distributions to generate kinetic profiles of compound effects, distinguishing between rapid cytotoxic responses and slower, more specific phenotypic alterations [11].

Diagram 2: HighVia Extend Assay Workflow

In Silico Tools for Enhanced Target Identification

Computational approaches have become indispensable for augmenting experimental target identification efforts. The CACTI (Chemical Analysis and Clustering for Target Identification) tool represents a significant advancement by enabling automated, multi-database analysis of compound libraries [13].

Key Functionality of CACTI:

Cross-Database Integration: Unlike tools limited to a single database, CACTI queries multiple chemogenomic resources including ChEMBL, PubChem, BindingDB, and scientific literature through their REST APIs [13].

Synonym Expansion and Standardization: The tool addresses the critical challenge of compound identifier inconsistency across databases by implementing a cross-referencing method that maps given identifiers based on chemical similarity scores and known synonyms [13].

Analog Identification and Similarity Analysis: CACTI uses RDKit to convert query structures to canonical SMILES representations, then identifies structural analogs through Morgan fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficient calculations (typically using an 80% similarity threshold) [13].

Bulk Compound Analysis: The tool enables high-throughput analysis of multiple compounds simultaneously, generating comprehensive reports that include known evidence, close analogs, and target prediction hints—drastically reducing the time required for preliminary compound prioritization [13].

Case Study: Phenotypic Screening in Glioblastoma Stem Cells

A practical application of chemogenomic library screening was demonstrated in a study profiling patient-derived glioblastoma (GBM) stem cell models [10]. Researchers employed a physically arrayed library of 789 compounds targeting 1,320 anticancer proteins to identify patient-specific vulnerabilities. The cell survival profiling revealed highly heterogeneous phenotypic responses across patients and GBM subtypes, underscoring the value of target-annotated compound libraries in identifying patient-specific vulnerabilities in complex disease models [10]. This approach successfully bridged the target identification gap by connecting specific phenotypic responses (reduced cell survival) to known molecular targets of the active compounds.

Chemogenomic libraries represent a powerful strategic solution to one of the most persistent challenges in phenotypic drug discovery: the identification of molecular mechanisms responsible for observed phenotypic effects. By integrating carefully curated, target-annotated compound collections with advanced high-content screening technologies and sophisticated computational tools, researchers can systematically bridge the target identification gap. The continued refinement of these libraries—through expanded target coverage, improved compound selectivity, and enhanced phenotypic annotation—will further accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and mechanisms in complex human diseases.

High-Content Imaging as a Multidimensional Profiling Tool

High-content imaging (HCI), also known as high-content screening (HCS) or high-content analysis (HCA), represents a transformative approach in biological research and drug discovery that combines automated microscopy with multiparametric image analysis to extract quantitative data from cellular systems [14]. This technology has emerged as a powerful method for identifying substances such as small molecules, peptides, or RNAi that alter cellular phenotypes in a desired manner, providing spatially resolved information on subcellular events while enabling systematic analysis of complex biological processes [14]. Unlike traditional high-throughput screening which typically relies on single endpoint measurements, high-content imaging enables the simultaneous evaluation of multiple biochemical and morphological parameters in intact biological systems, creating rich multidimensional datasets that offer profound insights into drug effects and cellular mechanisms [15] [14].

Within the context of chemogenomics and phenotypic drug discovery, high-content imaging has experienced growing importance as drug discovery paradigms have shifted from a reductionist "one target—one drug" vision to a more complex systems pharmacology perspective recognizing that complex diseases are often caused by multiple molecular abnormalities rather than single defects [9]. This technological approach is particularly valuable for phenotypic screening strategies that do not rely on prior knowledge of specific drug targets but instead focus on observable changes in cellular morphology, protein localization, and overall cell health [9] [16]. The resurgence of phenotypic screening in drug discovery, facilitated by advances in cell-based screening technologies including induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, gene-editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas, and sophisticated imaging assays, has positioned high-content imaging as an essential tool for deconvoluting the mechanisms of action induced by bioactive compounds and associating them with observable phenotypes [9] [11].

Technical Foundations of High-Content Imaging

Core Instrumentation and Imaging Modalities

High-content screening technology is primarily based on automated digital microscopy and flow cytometry, combined with sophisticated IT systems for data analysis and storage [14]. The fundamental principle underlying HCI involves the acquisition of spatially or temporally resolved information on cellular events followed by automated quantification [14]. Modern HCI instruments range from automated digital microscopy systems to high-throughput confocal imagers, with key differentiators including imaging speed, environmental control capabilities for live-cell imaging, integrated pipettors for kinetic assays, and available imaging modes such as confocal, bright field, phase contrast, and FRET (Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer) [14] [17].

Confocal imaging represents a significant advancement in HCI technology, enabling higher image signal-to-noise ratios and superior resolution compared to conventional epi-fluorescence microscopy through the rejection of out-of-focus light [14]. Contemporary implementations include laser scanning systems, single spinning disk with pinholes or slits, dual spinning disk technology such as the AgileOptix system, and virtual slit approaches, each with distinct trade-offs in sensitivity, resolution, speed, phototoxicity, photobleaching, instrument complexity, and cost [18] [14] [17]. These systems typically integrate into large robotic cell and medium handling platforms, enabling fully automated screening workflows that can process thousands of compounds in a single experiment while maintaining consistent environmental conditions for cell viability [14].

Image Analysis and Data Processing

The analytical backbone of high-content imaging relies on sophisticated software algorithms that transform raw image data into quantitative measurements of cellular features [4] [15]. The process begins with segmentation, which serves as the cornerstone of high-content analysis by identifying specific cellular elements such as nuclei, cytoplasm, or entire cells as distinct objects for analysis [4]. Nuclear segmentation, typically achieved using DNA-binding dyes such as Hoechst 33342 or HCS NuclearMask stains, enables the HCA software to identify individual cells, while cytoplasmic segmentation can often be performed without additional labels in most cell types [4]. For more complex analyses, whole-cell segmentation using HCS CellMask stains or plasma membrane stains provides additional morphological information [4].

Following segmentation, the software extracts multiple features from each identified object, including morphological parameters (size, shape, texture), intensity measurements (expression levels), and spatial relationships (subcellular localization, co-localization) [15]. Modern HCI platforms increasingly incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to handle complex analytical challenges, particularly in heterogeneous cell populations or three-dimensional model systems [18] [17]. These advanced analytical capabilities enable researchers to obtain valuable insights into diverse cellular features, including cell morphology, protein expression levels, subcellular localization, and comprehensive cellular responses to various treatments or stimuli [17].

High-Content Imaging Applications in Phenotypic Screening and Chemogenomics

Phenotypic Profiling and Mechanism of Action Deconvolution

High-content imaging has become an indispensable tool for phenotypic screening approaches that aim to identify biologically active compounds without requiring prior knowledge of their molecular targets [16] [11]. Technologies such as Cell Painting leverage high-content imaging to capture disease-relevant morphological and expression signatures by using multiple fluorescent dyes to label various cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles that serve as cellular fingerprints for different biological states and compound treatments [9]. These profiles enable the detection of subtle phenotypic changes induced by small molecules, facilitating the grouping of compounds into functional pathways and the identification of signatures associated with specific diseases [9].

In chemogenomic studies, high-content imaging provides a powerful approach for annotating chemical libraries by characterizing the effects of small molecules on basic cellular functions [11]. This application is particularly valuable given that many compounds in chemogenomic libraries, while designed for specific targets, may cause non-specific effects through compound toxicity or interference with fundamental cellular processes [11]. Comprehensive phenotypic profiling using HCI enables researchers to differentiate between target-specific and off-target effects by simultaneously monitoring multiple cellular health parameters, including nuclear morphology, cytoskeletal organization, cell cycle status, and mitochondrial health [11]. This multidimensional assessment provides a robust framework for evaluating compound suitability for subsequent detailed phenotypic and mechanistic studies, addressing a critical need in the annotation of chemogenomic libraries [11].

Network Pharmacology and Systems Biology Integration

The integration of high-content imaging data with network pharmacology approaches represents a cutting-edge application in chemogenomics research [9]. By combining morphological profiles from imaging-based assays with drug-target-pathway-disease relationships from databases such as ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, and Human Disease Ontology, researchers can construct comprehensive systems pharmacology networks that facilitate target identification and mechanism deconvolution for phenotypic screening hits [9]. These integrated networks enable the prediction of proteins modulated by chemicals that correlate with specific morphological perturbations observed through high-content imaging, ultimately linking these changes to relevant phenotypes and disease states [9].

This systems-level approach is particularly valuable for addressing complex diseases such as cancers, neurological disorders, and diabetes, which often involve multiple molecular abnormalities rather than single defects [9] [16]. The development of specialized chemogenomic libraries containing 5,000 or more small molecules representing diverse drug targets involved in various biological effects and diseases, when combined with high-content imaging and network pharmacology, creates a powerful platform for advancing phenotypic drug discovery [9]. This integrated strategy supports the identification of novel therapeutic avenues while providing insights into the systems-level mechanisms underlying drug action, moving beyond the limitations of traditional reductionist approaches in drug discovery [9] [16].

Experimental Design and Workflow Implementation

Core Methodologies for High-Content Cellular Profiling

The implementation of robust high-content imaging assays requires careful experimental design and optimization across multiple parameters. The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized approach for high-content imaging in phenotypic screening and chemogenomics:

Figure 1: High-content imaging workflow for phenotypic screening

Cell Culture and Model Systems

The selection of appropriate cellular models is fundamental to successful high-content imaging studies. While conventional two-dimensional cell cultures remain widely used due to their convenience and compatibility with automated imaging systems, there is growing interest in implementing more physiologically relevant three-dimensional models such as spheroids and organoids [19]. These three-dimensional systems better recapitulate the arrangement of cells in complex tissues and organs, providing more accurate models for events such as cell-cell signaling, interactions between different cell types, and therapeutic transit across cellular layers [19]. However, working with three-dimensional models presents significant challenges for high-content imaging, including heterogeneity in spheroid size and shape, inconsistent staining throughout the structure, optical aberrations deep within spheroids, and massive data storage requirements due to the need for extensive z-plane sampling [19]. For example, imaging approximately 750 small spheroids in a single well of a 96-well plate may require at least 50 optical slices in the z-direction, generating up to 45GB of data per well and 4.3TB for an entire plate [19].

Multiplexed Staining and Labeling Strategies

Comprehensive cellular profiling through high-content imaging typically employs multiplexed staining approaches using fluorescent dyes and antibodies with non-overlapping emission spectra. The selection of appropriate fluorescent probes depends on the specific cellular features and processes under investigation, with different classes of dyes targeting distinct cellular compartments and functions:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for High-Content Imaging

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Ex/Em (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Stains | Hoechst 33342, HCS NuclearMask Blue, Red, Deep Red stains | Nuclear segmentation, DNA content analysis, cell cycle assessment | 350/461, 350/461, 622/645, 638/686 [4] |

| Cytoplasmic & Whole Cell Stains | HCS CellMask Blue, Green, Orange, Red, Deep Red stains | Whole cell segmentation, cell shape and size analysis | 346/442, 493/516, 556/572, 588/612, 650/655 [4] |

| Plasma Membrane Stains | CellMask Green, Orange, Deep Red plasma membrane stains | Plasma membrane segmentation, membrane integrity assessment | 522/535, 554/567, 649/666 [4] |

| Mitochondrial Dyes | Mitotracker Red, Mitotracker Deep Red, HCS Mitochondrial Health Kit | Mitochondrial mass, membrane potential, health assessment | Varies by specific dye [4] [11] |

| Cytoskeletal Labels | BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye, Alexa Fluor phalloidin | Microtubule and actin organization, morphological analysis | 490/516 (BioTracker), varies for phalloidin conjugates [4] [11] |

| Viability & Apoptosis Markers | CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Reagent, LIVE/DEAD reagents, CellROX oxidative stress reagents | Cell viability, apoptosis detection, oxidative stress measurement | ~520 (CellEvent), varies for other reagents [4] |

Optimizing dye concentrations is critical for successful live-cell imaging applications, as excessively high concentrations may cause cellular toxicity or interfere with normal cellular functions, while insufficient concentrations yield weak signals that compromise data quality [11]. For example, Hoechst 33342 demonstrates robust nuclear staining at concentrations as low as 50nM while avoiding significant cytotoxicity observed at higher concentrations (≥1μM) [11]. Similarly, systematic validation of Mitotracker Red and BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye has confirmed minimal effects on cell viability at recommended working concentrations, enabling their use in extended live-cell imaging experiments [11].

Advanced High-Content Assay Protocols

Comprehensive Cellular Health Assessment

The HighVia Extend protocol represents an advanced live-cell multiplexed assay for comprehensive characterization of compound effects on cellular health [11]. This method classifies cells based on nuclear morphology as an indicator for cellular responses such as early apoptosis and necrosis, combined with the detection of other general cell damaging activities including changes in cytoskeletal morphology, cell cycle progression, and mitochondrial health [11]. The protocol enables time-dependent characterization of compound effects in a single experiment, capturing kinetics of diverse cell death mechanisms and providing multi-dimensional annotation of chemogenomic libraries [11].

The implementation of this protocol involves several key steps. First, cells are plated in multi-well plates at appropriate densities and allowed to adhere overnight. Subsequently, cells are treated with experimental compounds and stained with a carefully optimized dye cocktail containing Hoechst 33342 (50nM) for nuclear labeling, Mitotracker Deep Red for mitochondrial mass assessment, and BioTracker 488 Green Microtubule Cytoskeleton Dye for microtubule visualization [11]. Live-cell imaging is then performed at multiple time points using an automated high-content imaging system equipped with environmental control to maintain optimal temperature, humidity, and CO2 levels [11]. The acquired images are analyzed using supervised machine-learning algorithms that gate cells into distinct populations based on morphological features, typically classifying them as "healthy," "early apoptotic," "late apoptotic," "necrotic," or "lysed" [11]. This approach has demonstrated excellent correlation between overall cellular phenotype and nuclear morphology changes, enabling simplified assessment based solely on nuclear features when necessary, though multi-parameter analysis provides greater robustness against potential compound interference such as autofluorescence [11].

Cell Painting for Morphological Profiling

The Cell Painting assay represents a powerful high-content imaging approach for comprehensive morphological profiling that has gained significant adoption in phenotypic screening and chemogenomics [9]. This method uses up to six fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular components, including the nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, actin cytoskeleton, and plasma membrane, creating rich morphological profiles that serve as cellular fingerprints [9]. The standard Cell Painting protocol involves several key steps, beginning with cell plating in multi-well plates followed by treatment with experimental compounds. Cells are then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with a standardized dye cocktail before being imaged using automated high-content microscopy [9]. Image analysis typically involves the extraction of hundreds to thousands of morphological features measuring intensity, size, shape, texture, entropy, correlation, granularity, and spatial relationships across different cellular compartments [9]. For example, the BBBC022 dataset from the Broad Bioimage Benchmark Collection includes 1,779 morphological features measuring various parameters across cells, cytoplasm, and nuclei [9]. Advanced computational approaches, including machine learning and deep learning algorithms, are then employed to analyze these complex multidimensional datasets, identifying patterns and similarities between compound treatments and grouping compounds with similar mechanisms of action based on their morphological profiles [9].

Data Analysis and Interpretation in Chemogenomic Studies

Multidimensional Data Processing and Feature Extraction

The analysis of high-content imaging data in chemogenomic studies involves sophisticated computational approaches to extract meaningful biological insights from complex multidimensional datasets. The process typically begins with image preprocessing and quality control to identify and exclude images with technical artifacts, followed by cell segmentation to identify individual cells and subcellular compartments [4] [15]. Feature extraction then generates quantitative measurements for hundreds to thousands of morphological parameters for each cell, creating rich phenotypic profiles that serve as the foundation for subsequent analysis [9] [15]. Dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) are often employed to visualize and explore these high-dimensional datasets, enabling researchers to identify patterns and groupings among different treatment conditions [9].

Machine learning approaches play an increasingly important role in analyzing high-content imaging data from chemogenomic studies, with both supervised and unsupervised methods finding application [11]. Supervised machine learning algorithms can be trained to classify cells into distinct phenotypic categories based on reference compounds with known mechanisms of action, as demonstrated in the HighVia Extend protocol where a supervised algorithm gates cells into five different populations (healthy, early/late apoptotic, necrotic, lysed) using nuclear and cellular morphology features [11]. Unsupervised approaches such as clustering algorithms enable the identification of novel compound groupings based solely on morphological similarities, potentially revealing shared mechanisms of action or unexpected connections between compounds [9] [11]. These computational methods transform raw image data into quantitative phenotypic profiles that can be integrated with other data types, such as chemical structures, target affinities, and genomic information, to build comprehensive systems pharmacology models that enhance our understanding of compound mechanisms [9].

Integration with Chemogenomic Libraries and Target Annotation

High-content imaging data plays a crucial role in the annotation and validation of chemogenomic libraries, which contain well-characterized inhibitors with narrow but not exclusive target selectivity [11]. The integration of morphological profiling data with chemogenomic library screening enables more comprehensive compound annotation by capturing both intended target effects and potential off-target activities [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing the challenge of phenotypic screening, where the lack of detailed mechanistic insight complicates hit validation and development [11]. By screening chemogenomic libraries with known target annotations against a panel of phenotypic assays, researchers can build reference maps that connect specific morphological profiles to target modulation, facilitating mechanism of action prediction for uncharacterized compounds [9] [11].

The following diagram illustrates how high-content imaging integrates with chemogenomic screening for mechanism of action deconvolution:

Figure 2: High-content imaging in chemogenomic screening workflow

The integration of high-content imaging data with network pharmacology approaches creates powerful frameworks for target identification and mechanism deconvolution [9]. By combining morphological profiles from imaging-based assays with drug-target-pathway-disease relationships from databases such as ChEMBL, KEGG, Gene Ontology, and Human Disease Ontology, researchers can construct comprehensive systems pharmacology networks that facilitate the identification of proteins modulated by chemicals and their relationship to observed morphological perturbations [9]. These integrated networks enable the prediction of potential mechanisms of action for phenotypic screening hits and their connection to relevant disease biology, addressing a critical challenge in phenotypic drug discovery [9]. The development of specialized chemogenomic libraries representing diverse drug targets, when combined with high-content imaging and network pharmacology, creates a powerful platform for advancing phenotypic drug discovery for complex diseases [9].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Technical and Analytical Challenges

Despite its significant potential, the implementation of high-content imaging in chemogenomic research presents several substantial challenges. Data management represents a critical hurdle, as HCI generates massive datasets that strain storage capacity and computational resources [15] [19]. For example, imaging a single 96-well plate of three-dimensional spheroids may require acquisition of 50 or more z-planes per well, potentially generating up to 12TB of data per plate [19]. These massive datasets not only present storage challenges but also complicate data transfer, processing, and mining [15] [19]. Additionally, the lack of standardized image and data formats creates interoperability issues between different platforms and analytical tools, complicating data integration and comparison across studies [15].

The transition from traditional two-dimensional cell cultures to more physiologically relevant three-dimensional models introduces additional complexities for high-content imaging [19]. Three-dimensional cell models such as spheroids and organoids present challenges related to heterogeneity in size, shape, and cellular distribution, inconsistent staining throughout the structure, optical aberrations deep within tissue-like structures, and difficulties in segmenting individual cells within dense three-dimensional environments [19]. Furthermore, manipulations and perturbations such as transfection and drug treatment may not distribute evenly throughout three-dimensional models, potentially creating gradients of effect that complicate data interpretation [19]. Standardizing three-dimensional model production through methods such as micropatterning offers promising approaches to address some of these challenges by generating more uniform structures, but widespread implementation requires further development and validation [19].

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The future evolution of high-content imaging in chemogenomics will likely be shaped by several emerging trends and technological advancements. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are poised to revolutionize image analysis capabilities, particularly for complex three-dimensional models and subtle phenotypic changes that challenge traditional analytical approaches [18] [17]. These advanced computational methods will enable more accurate segmentation of individual cells within complex tissues, identification of rare cellular events, and detection of subtle morphological patterns that may escape human observation or conventional analysis [18]. Additionally, the integration of high-content imaging with other omics technologies, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, will provide increasingly comprehensive views of cellular responses to chemical perturbations, enabling more robust mechanism of action determination and enhancing the predictive power of in vitro models [9] [16].

The development of more sophisticated three-dimensional model systems represents another important direction for advancing high-content imaging in drug discovery [19]. While significant challenges remain in imaging and analyzing these complex models, they offer tremendous potential for bridging the knowledge gap between classical monolayer cultures and in vivo tissues, potentially reducing late-stage drug failures by providing more predictive models of drug efficacy and toxicity [19]. Advanced imaging technologies, including light-sheet microscopy and improved confocal systems with reduced phototoxicity, will facilitate the interrogation of these complex models while managing the substantial data burdens associated with three-dimensional imaging [19] [17]. Furthermore, the continued expansion and refinement of annotated chemogenomic libraries, coupled with increasingly sophisticated phenotypic profiling approaches, will enhance our ability to connect chemical structure to biological function, ultimately advancing both drug discovery and fundamental understanding of cellular biology [9] [11].

High-content imaging (HCI) has revolutionized phenotypic screening by enabling the quantitative capture of complex cellular responses to pharmacological and genetic perturbations. This whitepaper details the evolution from endpoint assays like Cell Painting to dynamic live-cell multiplexing, highlighting their critical application in chemogenomics and drug discovery. We provide a comprehensive technical examination of methodological workflows, data analysis pipelines, and reagent solutions that empower researchers to decode mechanisms of action and identify novel therapeutic candidates through morphological profiling.

Phenotypic screening has emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying novel small molecules and characterizing gene function in biological systems [20] [21]. Unlike target-based approaches, phenotypic screening observes compound effects in intact cellular systems, potentially revealing unexpected mechanisms of action. The development of high-content imaging (HCI) and analysis technologies has transformed this field by enabling the systematic quantification of morphological features at scale. Morphological profiling represents a paradigm shift from conventional screening, which typically extracts only one or two predefined features, toward capturing hundreds to thousands of measurements in a relatively unbiased manner [22]. This approach generates rich, information-dense profiles that serve as cellular "fingerprints" for characterizing chemical and genetic perturbations.

The global HCI market, valued at $3.4 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $5.1 billion by 2029, reflects the growing adoption of these technologies across pharmaceutical and academic research [23]. This growth is fueled by several factors: the need for more physiologically relevant models, advances in automated microscopy, sophisticated informatics solutions, and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for image analysis. Furthermore, the rise of complex biological systems such as 3D organoids and spheroids in screening cascades demands the multidimensional data capture that HCI uniquely provides [23] [24]. Within this landscape, profiling assays have become indispensable tools for functional annotation of chemogenomic libraries, bridging the gap between phenotypic observations and target identification [20].

Core Methodologies: From Cell Painting to Live-Cell Dynamics

The Cell Painting Assay

Cell Painting is a powerful, standardized morphological profiling assay that multiplexes six fluorescent dyes to visualize eight core cellular components across five imaging channels [25] [21]. This technique aims to "paint" the cell with a rich set of stains, revealing a comprehensive view of cellular architecture in a single experiment. The assay was designed to be generalizable, cost-effective, and compatible with standard high-throughput microscopes, making it accessible to non-specialized laboratories [22].

Table 1: Cell Painting Staining Reagents and Cellular Targets

| Dye Name | Imaging Channel | Cellular Target | Function in Profiling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | FITC/Green | Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) & Golgi Apparatus | Maps secretory pathway organization |

| Phalloidin (e.g., Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate) | TRITC/Red | Actin Cytoskeleton | Reveals cell shape, adhesion, and structural dynamics |

| Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA), Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate | Cy5/Far-Red | Plasma Membrane & Golgi | Outlines cell boundaries and surface features |

| SYTO 14 (or similar) | Green (DNA) | Nucleus & Nucleolus | Quantifies nuclear morphology and DNA content |

| MitoTracker (e.g., Deep Red) | Far-Red | Mitochondria | Assesses metabolic state and network organization |

| Hoechst 33342 (or similar) | Blue (DNA) | Nucleus | Segments cells and analyzes nuclear shape |

The workflow for a typical Cell Painting experiment involves a series of standardized steps. Cells are first plated in multiwell plates (96- or 384-well format) at the desired confluency. Following attachment, they are subjected to chemical or genetic perturbations for a specified duration. Cells are then fixed, permeabilized, and stained using the multiplexed dye combination, either with individual reagents or a pre-optimized kit [25]. Image acquisition is performed on a high-content screening system, with acquisition time varying based on sampling density, brightness, and z-dimensional sampling. Finally, automated image analysis software identifies individual cells and extracts approximately 1,500 morphological features per cell, including measurements of size, shape, texture, intensity, and inter-organelle correlations [25] [21].

Figure 1: Cell Painting Experimental Workflow. The standardized process from cell plating to phenotypic profiling, with key analytical steps highlighted.

Live-Cell Multiplexed Assays

While Cell Painting provides an exceptionally rich snapshot of cellular state, it is an endpoint assay requiring fixation. In contrast, live-cell multiplexing enables the dynamic tracking of phenotypic changes over time, capturing transient biological events and kinetic responses [20] [26]. These assays typically utilize fewer fluorescent channels optimized for cell health and viability, balancing information content with minimal cellular perturbation.

A representative live-cell multiplex screen for chemogenomic compound annotation monitors several key parameters over 48-72 hours. These include nuclear morphology as an excellent indicator of cellular responses like early apoptosis and necrosis, cytoskeletal organization through tubulin binding assessments, mitochondrial health via membrane potential dyes, and overall cell viability and proliferation [20]. This multi-parameter approach provides a time-dependent characterization of compound effects on fundamental cellular functions, allowing researchers to distinguish specific mechanisms from general toxicity.

The protocol for such assays involves plating cells in multiwell plates compatible with environmental control, followed by compound treatment with carefully planned plate layouts to control for edge effects. Time-lapse image acquisition is performed on systems equipped with environmental chambers (maintaining 37°C, 5% CO₂), with imaging intervals tailored to the biological process under investigation. Data analysis leverages machine learning techniques to classify cellular states and quantify treatment effects across multiple dimensions [26].

Figure 2: Live-Cell Multiplex Screening Workflow. The process for dynamic tracking of phenotypic changes, highlighting continuous monitoring and temporal profiling.

Data Analysis and Computational Approaches

The power of high-content imaging lies not only in image acquisition but in the computational extraction of biologically meaningful information from complex image datasets. The analysis pipeline begins with image preprocessing, including illumination correction and background subtraction to ensure data quality [21]. Subsequent cell segmentation identifies individual cells and their subcellular compartments, which is particularly challenging in complex models like 3D cultures.

Following segmentation, feature extraction algorithms quantify morphological characteristics across multiple dimensions. The Cell Painting assay typically generates approximately 1,500 features per cell, which can be categorized as follows [25]:

Table 2: Categories of Morphological Features in High-Content Analysis

| Feature Category | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Intensity-Based Features | Mean, median, and total fluorescence intensity per compartment | Reflects target protein abundance or localization |

| Shape Descriptors | Area, perimeter, eccentricity, form factor of cellular structures | Indicates structural changes and organizational state |

| Texture Metrics | Haralick features, granularity patterns, spatial relationships | Reveals subcellular patterning and organizational quality |

| Spatial Features | Distance between organelles, radial distribution | Captures inter-organelle interactions and positioning |

| Correlation Measures | Intensity correlations between different channels | Uncovers coordinated changes across cellular compartments |

For analysis, dimensionality reduction techniques (such as PCA or t-SNE) are often applied to visualize high-dimensional data, while machine learning algorithms (including clustering and classification methods) identify patterns and group perturbations with similar phenotypic effects [20] [26]. The application of deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has shown remarkable success in identifying disease-specific signatures, as demonstrated in studies discriminating Parkinson's disease patient fibroblasts from healthy controls based on morphological profiles [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of high-content phenotypic screening requires careful selection of reagents and tools optimized for imaging applications. The following table details key solutions for researchers establishing these capabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Content Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Kits | Image-iT Cell Painting Kit | Pre-optimized reagent set for standardized morphological profiling [25] |

| Live-Cell Fluorescent Probes | MitoTracker, CellMask, SYTO dyes | Enable dynamic tracking of organelles and cellular structures without fixation [20] |

| Cell Health Indicator Dyes | Caspase sensors, membrane integrity dyes | Assess viability and detect apoptosis/necrosis in live-cell assays [20] |

| High-Content Screening Instruments | CellInsight CX7 LZR Pro, Yokogawa CQ1 | Automated imaging systems with environmental control for multiwell plates [25] [26] |

| Image Analysis Software | CellProfiler, CellPathfinder, IN Carta | Open-source and commercial platforms for feature extraction and analysis [21] [26] |

Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

The integration of high-content morphological profiling with chemogenomic libraries has created powerful opportunities for functional annotation of compounds and target identification [20]. In this framework, comprehensive phenotypic characterization serves as a critical quality control step, distinguishing compounds with specific biological effects from those causing general cellular toxicity. Well-characterized small molecules with narrow target selectivity enable more confident association of phenotypic readouts with molecular targets [20].

Cell Painting and live-cell multiplexing have demonstrated particular utility in several key applications:

Mechanism of Action Identification: By clustering compounds based on phenotypic similarity, researchers can infer mechanisms of action for uncharacterized molecules based on their proximity to well-annotated references in morphological space [21] [22].

Lead Optimization and Hopping: Morphological profiles can identify structurally distinct compounds that produce similar phenotypic effects, enabling movement from initial hits to more favorable chemical series while maintaining desired biological activity [22].

Functional Gene Annotation: Genetic perturbations (RNAi, CRISPR, overexpression) can be profiled to cluster genes by functional similarity, revealing novel pathway relationships and characterizing the impact of genetic variants [21].

Disease Signature Reversion: Disease models exhibiting strong morphological signatures can be screened against compound libraries to identify candidates that revert the phenotype toward wild-type, potentially revealing new therapeutic applications for existing drugs [21] [22].

Library Enrichment: Profiling diverse compound collections enables the selection of screening sets that maximize phenotypic diversity while eliminating inert compounds, improving screening efficiency and cost-effectiveness [22].

The evolution from static endpoint assays like Cell Painting to dynamic live-cell profiling represents a significant advancement in our ability to capture complex phenotypes in chemogenomic research. These complementary approaches provide multidimensional data that enrich our understanding of compound and gene function, bridging the gap between phenotypic observations and target identification. As the field progresses, several emerging trends are poised to further transform high-content screening.

The integration of HCI data with other omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics) creates powerful multi-modal profiles for deeper biological insight [24]. Similarly, the application of artificial intelligence and deep learning continues to advance, enabling the detection of subtle morphological patterns beyond human perception [25] [23]. The shift toward more physiologically complex models, including 3D organoids and microtissues, presents both challenges and opportunities for image-based profiling [23]. Finally, the development of standardized image data repositories and analysis pipelines promotes reproducibility and collaborative mining of large-scale screening datasets [24].

Together, these advancements solidify the role of high-content morphological profiling as an indispensable component of modern chemogenomics and drug discovery, providing an unbiased window into cellular state and function that accelerates the identification and characterization of therapeutic candidates.

Deconvoluting Mechanism of Action (MoA) from Morphological Profiles

Deconvoluting the mechanism of action (MoA) of small molecules is a central challenge in modern drug discovery. While target-based screening strategies have long dominated, phenotypic screening, particularly using high-content imaging, has re-emerged as a powerful approach for identifying first-in-class therapeutics with novel mechanisms. Morphological profiling, via assays such as Cell Painting, enables the unbiased identification of a compound's MoA by comparing its induced cellular phenotype to a reference library of annotated compounds, irrespective of chemical structure or predetermined biological target [27] [1]. This technical guide details the core concepts, methodologies, and data integration strategies for deconvoluting MoA from morphological profiles within the context of high-content imaging phenotypic screening and chemogenomics research.

The molecular biology revolution of the 1980s shifted drug discovery towards a reductionist approach focused on specific molecular targets. However, an analysis of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2008 revealed that a majority were discovered empirically without a predefined target hypothesis, catalyzing a major resurgence in phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) [1]. Modern PDD uses realistic disease models and sophisticated tools to systematically discover drugs based on therapeutic effects.