Gene Family Evolution: Methods for Expansion and Contraction Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to gene family expansion and contraction analysis, a cornerstone of evolutionary genomics with profound implications for understanding drug metabolism, disease mechanisms, and adaptive traits.

Gene Family Evolution: Methods for Expansion and Contraction Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to gene family expansion and contraction analysis, a cornerstone of evolutionary genomics with profound implications for understanding drug metabolism, disease mechanisms, and adaptive traits. We detail the complete analytical workflow—from foundational concepts and core bioinformatics methodologies to advanced troubleshooting and validation strategies. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this resource bridges theoretical population genetics with practical application, empowering studies of pharmacogenomic loci, immune gene families, and pathogen adaptation using current genomic datasets and tools.

The Evolutionary Why: Core Principles and Biological Significance of Gene Family Dynamics

Defining Gene Family Expansion and Contraction in Evolutionary Genomics

Gene families are sets of homologous genes that originate from a single ancestral gene through duplication events and typically share similar sequences and biochemical functions [1]. The evolution of gene families is characterized by dynamic processes of expansion and contraction, primarily driven by gene duplication and loss [2]. These dynamics represent a crucial evolutionary mechanism, generating genetic novelty that enables organisms to adapt to changing environments, develop new biological functions, and undergo diversification [3] [4].

Analyzing gene family expansion and contraction provides critical insights into evolutionary adaptations across diverse species. For instance, in the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens), gene family expansions are enriched for digestive, immunity, and olfactory functions, explaining its remarkable efficiency in decomposing organic waste [5]. Similarly, in plants of the Anacardiaceae family, expansions in defense-related gene families like WRKY transcription factors and NLR genes correlate with adaptive responses to biotic stresses [6].

This protocol outlines comprehensive methodologies for identifying and analyzing gene family expansion and contraction, providing researchers with standardized approaches to investigate these fundamental evolutionary genomic processes.

Quantitative Foundations of Gene Family Dynamics

Gene family dynamics vary significantly across major eukaryotic lineages. Large-scale comparative analyses of 1,154 yeast genomes, alongside plant, animal, and filamentous fungal genomes, reveal distinct evolutionary trajectories [3] [4]. Yeasts exhibit smaller overall gene numbers yet maintain larger gene family sizes for a given gene number compared to animals and filamentous ascomycetes [4].

Table 1: Gene Family Characteristics Across Major Eukaryotic Lineages

| Lineage | Average Gene Number | Weighted Average Gene Family Size | Number of Core Gene Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeasts (Saccharomycotina) | 5,908 | 1.12 genes/family | 5,551 |

| Filamentous Ascomycetes | Not specified | Smaller than animals/plants | 9,473 |

| Animals | Not specified | Larger than yeasts/fungi | 11,076 |

| Plants | Not specified | Largest among major lineages | 8,231 |

The correlation between gene content and family size is particularly strong in certain lineages. Phylogenetic independent contrasts (PICs) reveal strong positive correlations between weighted average gene family size and protein-coding gene number in plants (rho = 0.97), yeasts (rho = 0.82), and filamentous ascomycetes (rho = 0.88) [3].

Table 2: Evolutionary Patterns in Faster-Evolving vs. Slower-Evolving Yeast Lineages

| Characteristic | Faster-Evolving Lineages (FELs) | Slower-Evolving Lineages (SELs) |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Family Size | Smaller | Larger |

| Evolutionary Rate | Higher | Lower |

| Gene Loss Rate | Significantly higher | Lower |

| Metabolic Niche | Narrowed | Broader |

| Speciation Rate | Higher | Lower |

The functional consequences of these dynamics are profound. Faster-evolving yeast lineages experience significantly higher rates of gene loss, particularly affecting gene families involved in mRNA splicing, carbohydrate metabolism, and cell division [3] [4]. These contractions correlate with biological phenomena such as intron loss, reduced metabolic breadth, and non-canonical cell cycle processes [4].

Standard Analytical Protocol for Gene Family Analysis

Orthology Inference and Family Identification

The foundational step in gene family analysis involves identifying homologous genes and grouping them into families. OrthoFinder is widely used for this purpose, as it employs a scalable algorithm to infer orthogroups across multiple species [5] [7]. The protocol proceeds as follows:

Input Data Preparation: Collect protein sequences for all genes from all study species. For genome annotations containing multiple transcripts per gene, filter to retain only the longest transcript to ensure phylogenetic independence [5] [8].

Orthogroup Inference: Run OrthoFinder with default parameters. The algorithm performs an all-versus-all BLAST search, applies inflation factors for clustering, and resolves orthologous relationships [7].

Family Size Calculation: For each species, calculate gene family size as the number of genes assigned to each orthogroup. These counts form the basis for expansion/contraction analyses [7].

Detecting Expansion and Contraction with CAFE

The Computational Analysis of Gene Family Evolution (CAFE) is a standard tool for identifying statistically significant changes in gene family sizes across phylogenetic trees [7]. The methodology includes:

Input Preparation: Prepare two input files: (1) the gene family counts per species table, and (2) an ultrametric phylogenetic tree with divergence times. The tree can be reconstructed using tools like r8s [7].

Model Selection: CAFE employs a probabilistic model that accounts for random gene birth and death processes across the phylogeny. The global birth (λ) and death (μ) rates can be set as fixed parameters or allowed to vary across branches [7].

Statistical Testing: CAFE calculates p-values for significant expansion or contraction of each gene family using a Monte Carlo simulation approach. Families with p-values below a significance threshold (typically 0.05) are considered to have undergone significant changes.

Lineage-Specific Analysis: Advanced CAFE implementations can identify lineages with accelerated rates of gene family evolution and test for branch-specific shifts in evolutionary rates [7].

Functional Annotation Integration

To interpret the biological significance of expanding or contracting gene families, functional annotation is essential:

Annotation Tools: Use InterProScan or similar tools to assign functional domains and Gene Ontology terms to each gene [7].

Enrichment Analysis: Perform statistical enrichment tests (e.g., Fisher's exact test) to identify functional categories overrepresented in expanding or contracting families [5].

Contextual Interpretation: Relate enriched functions to species-specific biology. For example, in black soldier flies, expanded digestive and metabolic gene families correlate with their decomposing lifestyle [5].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Detection of Selection in Gene Families

Identifying natural selection acting on gene families provides crucial insights into adaptive evolution. The FUSTr (Finding Families Under Selection in Transcriptomes) pipeline offers a comprehensive approach [8]:

Data Preprocessing: Validate input FASTA files and remove spurious characters that may disrupt analyses [8].

Isoform Detection: Automatically detect isoforms by analyzing header patterns and naming conventions. Retain only the longest isoform for each gene to ensure phylogenetic independence [8].

Gene Prediction: Use TransDecoder to identify open reading frames (ORFs) and extract coding sequences. Default parameters include a minimum coding sequence length of 30 codons [8].

Homology Assessment: Perform homology searches using DIAMOND BLASTP with an e-value cutoff of 10⁻⁵ [8].

Family Inference: Cluster sequences into gene families using SiLiX with recommended parameters (35% minimum identity, 90% minimum overlap) [8].

Selection Tests: Apply the FUBAR (Fast Unconstrained Bayesian Approximation) method to identify sites under pervasive positive or negative selection. For families with at least 15 sequences, FUBAR provides statistical power to detect selection [8].

Proteogenomic Integration for Mutation Detection

Advanced proteogenomic approaches can identify genetic mutations expressed at the protein level. The moPepGen tool addresses this challenge [9]:

Graph-Based Modeling: moPepGen uses graph-based approaches to efficiently process diverse genetic variations, including single amino acid substitutions, alternative splicing, gene fusions, and RNA editing [9].

Variant Peptide Detection: The tool systematically models how genetic variants are transcribed and translated, enabling detection of protein-level variations that traditional genomic approaches miss [9].

Validation: In prostate and kidney tumor analyses, moPepGen detected four times more unique protein variants than previous methods, demonstrating enhanced sensitivity [9].

Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

Gene Family Analysis Workflow

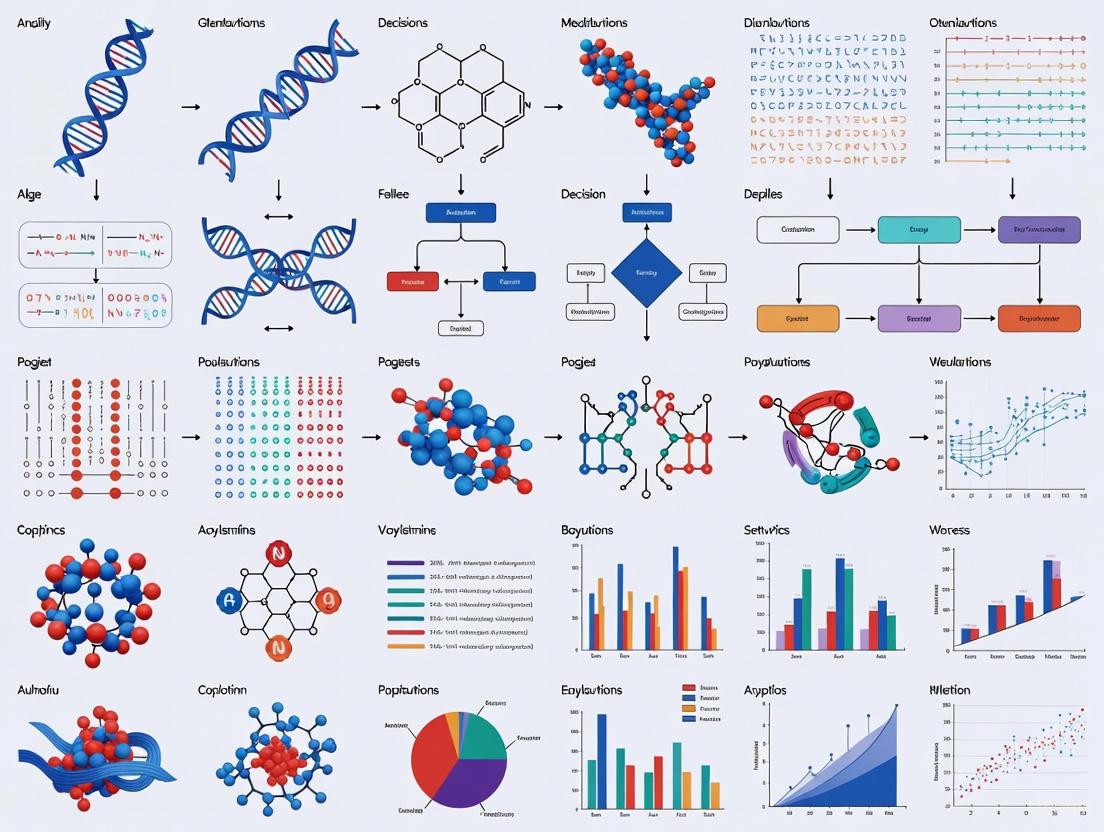

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for analyzing gene family expansion and contraction:

Gene Family Evolutionary Dynamics

This diagram illustrates the evolutionary processes governing gene family expansion and contraction:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Gene Family Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Software | Orthogroup inference | Groups genes into families based on homology; essential initial step [5] [7] |

| CAFE | Software | Gene family evolution | Models birth/death processes; detects significant expansion/contraction [7] |

| FUSTr | Software | Selection detection | Identifies families under positive selection; optimized for transcriptomes [8] |

| moPepGen | Software | Proteogenomic analysis | Detects genetic mutations at protein level; graph-based approach [9] |

| TransDecoder | Software | Gene prediction | Identifies coding regions in transcripts; crucial for transcriptome data [8] |

| DIAMOND | Software | Homology search | Accelerated BLAST-like tool; fast processing of large datasets [8] |

| SiLiX | Software | Gene family clustering | Transitive clustering algorithm; reduces domain chaining issues [8] |

| BUSCO | Software | Genome assessment | Evaluates completeness of genome assemblies; quality control step [5] |

| Earl Grey | Software | Repetitive element analysis | Identifies transposable elements; understands duplication mechanisms [5] |

The analysis of gene family expansion and contraction provides powerful insights into evolutionary mechanisms driving adaptation and diversification across the tree of life. The standardized protocols outlined here—from orthology inference and statistical detection of family size changes to selection analysis and functional interpretation—offer researchers a comprehensive methodological framework.

These approaches have revealed fundamental patterns, such as the prevalence of gene family contractions in faster-evolving yeast lineages [3] [4] and the expansion of digestive and olfactory gene families in adaptively successful insects [5]. As genomic data continue to accumulate, these methods will remain essential for deciphering the molecular basis of evolutionary innovation.

The birth-and-death evolution model represents a fundamental paradigm for understanding how multigene families evolve and diversify over time. In contrast to the earlier prevailing theory of concerted evolution, in which all member genes of a family evolve as a unit through homogenization processes, the birth-and-death model proposes that new genes are created by gene duplication, with some duplicate genes persisting in the genome for long periods while others are inactivated or deleted [10]. This model successfully explains the evolutionary patterns observed in numerous gene families, including those encoding MHC molecules, immunoglobulins, and various disease-resistance genes [10]. The model's particular strength lies in its ability to provide insights into the origins of new genetic systems and phenotypic characters that underlie biological innovation and adaptation.

The controversy between concerted and birth-and-death evolutionary models emerged prominently around the 1990s, when phylogenetic analyses of immune system genes revealed patterns inconsistent with concerted evolution [10]. While concerted evolution effectively described the behavior of ribosomal RNA genes and other tandemly repeated sequences, many protein-coding genes exhibited evolutionary trajectories better explained by the birth-and-death process. This model has since been shown to govern the evolution of most non-rRNA genes, including highly conserved families such as histone and ubiquitin genes [10]. The distinction between the two models becomes particularly challenging when sequence differences are small, contributing to the ongoing scientific discourse in this field.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Core Principles of the Model

The birth-and-death model operates on several fundamental principles that distinguish it from other evolutionary frameworks. First, it posits that gene duplication serves as the primary mechanism for generating new genetic material, creating the raw substrate upon which evolutionary forces can act [10] [11]. Second, the model recognizes that following duplication, duplicate genes experience diverse evolutionary fates mediated by a combination of stochastic processes and natural selection. Third, the long-term evolutionary dynamics are characterized by differential retention and loss of gene copies across lineages, resulting in gene family expansions and contractions that reflect both historical contingencies and adaptive pressures [12].

The conceptual distinction between three critical phases in the lifecycle of duplicated genes is essential for understanding birth-and-death evolution: (1) the mutational event of duplication itself, (2) the fixation of duplicates within a population, and (3) the long-term maintenance or preservation of functional duplicates [12]. Each of these stages is influenced by different evolutionary forces and population genetic parameters. Fixation refers to the process by which a duplicate spreads through a population, while maintenance describes the stabilization of a duplicate over evolutionary timescales. The probability of a gene duplicate transitioning through these stages depends on multiple variables, including population size, selection regimes, and the functional characteristics of the gene involved [12].

Evolutionary Fates of Duplicated Genes

Table 1: Evolutionary Fates of Duplicated Genes

| Fate | Mechanism | Outcome | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfunctionalization | Accumulation of degenerative mutations in one copy | Loss of function, pseudogenization, eventual deletion | Most common fate; majority of vertebrate duplicates [12] |

| Neofunctionalization | One copy acquires a novel beneficial function through mutation | Both copies preserved: original and new function | Drosophila bithorax complex; plant cytochrome P450 genes [11] |

| Subfunctionalization | Both copies undergo complementary degenerative mutations | Partition of original functions between duplicates | Duplication-degeneration-complementation model [13] |

| Hypofunctionalization | Reduced expression in both copies while maintaining total output | Dosage sharing; maintained due to insufficient individual output | Common trajectory for dosage-sensitive genes [11] |

The evolutionary trajectories available to duplicated genes are diverse and context-dependent. Nonfunctionalization represents the most common fate, wherein one duplicate copy accumulates deleterious mutations and eventually becomes a pseudogene or is deleted from the genome [12]. This outcome is particularly likely when the duplicate is functionally redundant and not subject to strong purifying selection. In contrast, neofunctionalization occurs when one duplicate acquires a mutation conferring a novel, beneficial function that is subsequently preserved by natural selection [11]. This process, championed by Susumu Ohno, provides a mechanism for evolutionary innovation and has been documented in diverse gene families, including those governing developmental patterning and metabolic diversity.

Subfunctionalization describes an alternative pathway where both duplicates undergo complementary degenerative mutations that collectively partition the ancestral gene's functions or expression patterns [13]. In this scenario, both copies are preserved because neither can independently perform the full complement of ancestral functions. The duplication-degeneration-complementation model formalizes this process, which involves a waiting time for multiple mutations to accumulate in both copies before the complementary functions become essential for maintaining fitness [13]. Additionally, hypofunctionalization represents a pathway where both duplicates experience reduced expression, with the combined output maintained at a level that selection preserves both copies because loss of either would reduce total expression below a critical threshold [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Birth-and-Death Evolution

Mathematical Modeling Approaches

The development of probabilistic models has significantly enhanced our ability to analyze birth-and-death evolution quantitatively. The birth-death (BD) model, adapted from population biology and phylogenetics, provides a mathematical framework for describing the stochastic processes of gene duplication and loss [13]. In its basic formulation, the BD model treats gene duplication as a "birth" event and gene loss or pseudogenization as a "death" event, with rates that can be estimated from comparative genomic data.

Advanced modeling approaches have incorporated age-dependent birth-death processes where the loss rate varies depending on the time since duplication [13]. This refinement allows different gene retention mechanisms to be distinguished based on their characteristic hazard functions—the instantaneous rate of duplicate loss over time. For nonfunctionalization, the hazard rate remains constant, while for neofunctionalization, it declines convexly as the probability of acquiring a beneficial mutation increases. For subfunctionalization, the hazard function exhibits a sigmoidal shape, initially increasing as deleterious mutations accumulate before decreasing once complementary functions become established [13].

Table 2: Parameters in Birth-Death Evolutionary Models

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation in Different Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Duplication rate (λ) | Probability of duplication per gene per unit time | Generally assumed constant across mechanisms [13] |

| Loss rate (μ) | Probability of loss per duplicate per unit time | Constant for nonfunctionalization; time-dependent for other mechanisms [13] |

| Hazard function | Instantaneous rate of duplicate loss | Distinct shapes differentiate mechanisms: constant (nonfunctionalization), convexly declining (neofunctionalization), sigmoidal (subfunctionalization) [13] |

| Retention probability | Probability that a duplicate is maintained long-term | Higher for genes with complex regulation, dosage sensitivity, or potential for functional diversification [12] |

Comparative Genomic Analysis

Empirical analysis of birth-and-death evolution relies heavily on comparative genomics approaches that examine gene family dynamics across multiple species. The typical workflow begins with orthology assignment, in which genes are clustered into orthologous groups (orthogroups) descending from a common ancestor [5]. Tools such as OrthoFinder implement sophisticated algorithms for identifying orthogroups across multiple genomes, providing the fundamental data structure for subsequent analysis of gene family expansion and contraction [5].

The CAFE (Computational Analysis of gene Family Evolution) software represents a widely used method for detecting statistically significant changes in gene family size across phylogenetic trees [14]. This approach compares observed gene counts to expectations under a stochastic birth-death process, identifying families that have expanded or contracted more rapidly than expected by chance. Applications of this methodology have revealed, for instance, that the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) exhibits significant expansions of digestive, immunity, and olfactory gene families, likely contributing to its ecological success and adaptive capabilities [5]. Similarly, studies of the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) have documented 3066 gene family expansion events, including significant expansion of histone, cuticula, and CYP450 gene superfamilies that underpin its invasive characteristics [14].

Experimental Protocols for Gene Family Analysis

Protocol 1: Orthology Assignment and Phylogenomic Profiling

Objective: To identify orthologous gene families and reconstruct their evolutionary history across multiple species.

Materials:

- Genome assemblies and annotation files for target species

- Computational resources: High-performance computing cluster with sufficient memory and storage

- Software tools: OrthoFinder, BUSCO, MAFFT, ModelFinder

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Quality Control

- Download genome assemblies and annotation files from public databases (NCBI, InsectBase, etc.)

- Assess genome completeness using BUSCO with lineage-specific datasets

- Filter annotations to retain only the longest transcript per gene using primary_transcript.py script from OrthoFinder

Orthology Assignment

- Run OrthoFinder with default parameters:

orthofinder -f [input_directory] -M msa -t [number_of_threads] - OrthoFinder will perform: (a) BLAST all-vs-all comparisons, (b) Orthogroup inference, (c) Multiple sequence alignment, (d) Gene tree inference, and (e) Species tree reconstruction

- Run OrthoFinder with default parameters:

Phylogenomic Analysis

- Extract single-copy orthologs from OrthoFinder results

- Concatenate alignments using appropriate utilities

- Perform phylogenetic reconstruction using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., IQ-TREE) with ModelFinder for best-fit model selection

Interpretation

- Identify species-specific gene family expansions/contractions from orthogroup size statistics

- Map gene family dynamics to the species phylogeny to infer evolutionary timing

Troubleshooting: Incomplete genomes may bias orthogroup inference; consider using only high-quality genomes with >90% BUSCO completeness. Large phylogenies may require substantial computational resources; consider subsetting or using approximate methods for initial analysis [5].

Protocol 2: Detecting Significantly Expanded Gene Families

Objective: To identify gene families that have undergone statistically significant expansion in specific lineages.

Materials:

- Orthogroup count matrix from OrthoFinder output

- Species tree with divergence times

- Software tools: CAFE, R with appropriate packages

Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Format orthogroup count matrix according to CAFE requirements

- Prepare ultrametric species tree, calibrating branch lengths with divergence times where available

CAFE Analysis

- Run CAFE with base model:

cafe [script_file] - The analysis will: (a) Estimate global birth-and-death parameters (λ), (b) Compute expected gene family sizes, (c) Identify families deviating from expectations

- Run CAFE with base model:

Statistical Testing

- CAFE computes p-values for expansion/contraction using a probabilistic framework

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing

- Set significance threshold at p < 0.05 after correction

Functional Enrichment Analysis

- Extract significantly expanded gene families

- Perform Gene Ontology enrichment analysis using appropriate tools (e.g., clusterProfiler)

- Identify overrepresented biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components

Troubleshooting: Large variations in genome quality can bias results; consider normalization approaches. Absence of divergence times may reduce precision; use published timetrees or approximate with molecular clock methods when necessary [14].

Protocol 3: Mechanistic Analysis of Gene Retention

Objective: To distinguish between different mechanisms of duplicate gene retention (nonfunctionalization, neofunctionalization, subfunctionalization).

Materials:

- Sequence data for duplicated gene pairs

- Expression data (RNA-seq) across multiple tissues/conditions

- Software tools: PAML, computational tools for dN/dS calculation, R for statistical analysis

Procedure:

Evolutionary Rate Analysis

- Identify recently duplicated gene pairs within species (paralogs)

- Calculate synonymous (dS) and nonsynonymous (dN) substitution rates using codeml in PAML

- Compute dN/dS ratio (ω) for each duplicate pair

Expression Pattern Analysis

- Extract expression values for duplicate genes across multiple tissues/conditions

- Calculate expression divergence using correlation coefficients or specialized metrics

- Test for tissue-specific or condition-specific expression patterns

Tests for Different Mechanisms

- Nonfunctionalization: Elevated dN/dS in one copy, reduced expression breadth

- Neofunctionalization: Signatures of positive selection, novel expression contexts, functional innovations

- Subfunctionalization: Complementary degenerative mutations, partitioned expression patterns

Statistical Framework

- Implement likelihood ratio tests to compare evolutionary models

- Use appropriate multiple testing corrections

- Integrate evidence from evolutionary and expression analyses

Troubleshooting: Incomplete expression data may limit detection of subfunctionalization; seek comprehensive tissue/condition coverage. Recent duplicates may show limited divergence; focus on older duplicates for clearer signal of preservation mechanisms [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Birth-and-Death Evolution Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | NCBI RefSeq, InsectBase, Darwin Tree of Life | Source of genome assemblies and annotations | Curated genomes, standardized annotations, phylogenetic breadth [5] [14] |

| Quality Assessment | BUSCO | Assessment of genome completeness | Lineage-specific benchmarks, quantitative completeness metrics [5] |

| Orthology Assignment | OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic orthology inference | Scalable, integrated MSA and tree inference, user-friendly output [5] |

| Gene Family Evolution | CAFE | Detection of significant expansions/contractions | Phylogenetic framework, statistical testing, branch-specific models [14] |

| Selection Analysis | PAML (codeml) | Detection of selection signatures | Site models, branch models, branch-site models for positive selection [13] |

| Expression Analysis | RNA-seq pipelines | Expression pattern comparison | Tissue-specificity, condition-responsiveness, complementary expression |

Applications and Case Studies

Evolutionary Innovations in Black Soldier Fly

Comparative genomics of eight Asilidae and six Stratiomyidae species revealed how gene family expansions underpin functional adaptation in the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) [5]. The analysis demonstrated that gene families showing more duplications in Stratiomyidae are enriched for metabolic functions, consistent with their role as active decomposers. In contrast, Asilidae, which are predators with longer lifespans, showed expansions in longevity-associated gene families. Specific to H. illucens, researchers observed expansions in olfactory and immune response gene families, while across Stratiomyidae more broadly, there was enrichment of digestive and metabolic functions such as proteolysis [5]. These findings provide a compelling explanation for the higher decomposing efficiency and adaptive ability of H. illucens compared to related species, illustrating how birth-and-death evolution drives ecological specialization.

Histone Family Expansion in Spodoptera frugiperda

Analysis of 46 lepidopteran species revealed that the invasive pest Spodoptera frugiperda (fall armyworm) has experienced the highest number of gene family expansion events among studied species, with 3066 expanded gene families [14]. Particularly noteworthy was the expansion of histone gene families resulting from chromosome segmental duplications that occurred after divergence from closely related species. Expression analysis demonstrated that specific histone family members play roles in growth and reproduction processes, potentially contributing to the remarkable reproductive capacity and environmental adaptability of this invasive species [14]. This case study exemplifies how birth-and-death evolution of even highly conserved gene families like histones can contribute to the evolution of invasive traits and ecological success.

Implications for Drug Development and Human Health

The birth-and-death model has significant implications for drug development, particularly in understanding the evolution of drug targets and metabolic pathways. Gene families involved in drug metabolism, such as cytochrome P450 enzymes, frequently evolve via birth-and-death processes, resulting in substantial interspecific differences that complicate drug safety evaluation and dosage determination [11] [15]. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics enables more informed selection of animal models for preclinical testing and helps explain cases of species-specific drug toxicity or efficacy.

Furthermore, the expansion of gene families involved in immune recognition and xenobiotic metabolism through birth-and-death evolution directly impacts drug discovery and development [10] [15]. For instance, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes, which play crucial roles in immune recognition and personalized medicine, evolve primarily through birth-and-death processes, generating extensive polymorphism that influences individual variation in drug responses [10]. Similarly, the expansion of olfactory and taste receptor families in various species illustrates how birth-and-death evolution shapes sensory systems that can influence medication palatability and compliance [5]. These insights underscore the importance of considering evolutionary history when designing therapeutic interventions and interpreting interspecific differences in drug responses.

Understanding the link between genomic changes and organismal phenotype is a central goal in modern biology, with profound implications for drug discovery, functional genomics, and evolutionary biology. Gene family expansion and contraction represent key evolutionary mechanisms that generate genetic novelty and enable adaptive traits. This application note examines how comparative genomics and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) reveal the molecular basis of specialized functions across different species and human populations. We present three detailed case studies focusing on digestive adaptation in the black soldier fly, olfactory receptor diversity in humans, and immune-related gene expansion in plants, providing experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers investigating genotype-phenotype relationships.

Case Studies in Phenotype-Genotype Linking

Digestive and Metabolic Adaptation in Hermetia illucens

Background: The black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) possesses remarkable abilities to convert organic waste into biomass, exhibiting exceptional digestive efficiency compared to related species [5]. A comparative genomics analysis across Stratiomyidae (soldier flies) and Asilidae (robber flies) revealed that gene families showing significant expansion in H. illucens are predominantly enriched for digestive and metabolic functions [5].

Key Genomic Findings:

- Gene Family Expansions: Stratiomyidae genomes contain significantly expanded gene families related to proteolysis and metabolic processes [5].

- Lineage-Specific Adaptations: H. illucens shows specific expansions in olfactory and immune response genes, while digestive adaptations are conserved across Stratiomyidae [5].

- Genomic Mechanisms: Transposable elements contribute substantially to genome size variation, with Stratiomyidae genomes being generally larger than Asilidae and containing a higher proportion of recently expanded transposable elements [5].

Table 1: Genomic Features Associated with Digestive Adaptation in Stratiomyidae

| Genomic Feature | Stratiomyidae | Asilidae | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | Larger | Smaller | Correlation with transposable element content |

| Digestive Gene Families | Expanded | Less expanded | Enhanced decomposition capability |

| Metabolic Gene Duplications | Enriched | Limited | Waste conversion efficiency |

| Transposable Elements | Higher proportion, recently expanded | Lower proportion | Genome evolution and adaptation |

Olfactory Function in Human Populations

Background: Olfactory dysfunction serves as an early marker for neurodegenerative diseases and has been associated with increased mortality in older adults [16]. Recent large-scale genomic studies have elucidated the genetic architecture underlying human olfactory perception.

Key Genomic Findings:

- Novel Genetic Loci: GWMA of 22,730 individuals of European ancestry identified a novel genome-wide significant locus (rs11228623 at 11q12) associated with olfactory dysfunction [16].

- Sex-Specific Effects: Sex-stratified analysis revealed female-specific loci (e.g., rs116058752 associated with orange odor identification) and sex-differential genetic effects [17].

- Olfactory Receptor Enrichment: Gene-based analysis demonstrated significant enrichment for olfactory receptor genes, particularly in associated regions [16] [17].

- Pleiotropic Effects: Variants associated with olfactory dysfunction demonstrate significant associations with blood cell counts, kidney function, skeletal muscle mass, cholesterol levels, and cardiovascular disease [16].

Table 2: Genome-Wide Significant Loci Associated with Human Olfactory Perception

| Locus | Key SNP | Phenotypic Association | Candidate Gene/Region | Special Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs73252922 | Fish odor identification | FIP1L1/GSX2 | - |

| 2 | rs116058752 | Orange odor identification | ADCY2 | Female-specific |

| 11q12 | rs11228623 | General olfactory dysfunction | Olfactory receptor gene cluster | Novel discovery |

Immune and Defense-Related Genes in Plants

Background: The Anacardiaceae plant family exhibits substantial genomic diversity and adaptive complexity, with lineage-specific expansions in defense-related genes [6]. Gene family expansions provide molecular flexibility for environmental adaptation.

Key Genomic Findings:

- Defense Gene Expansions: WRKY transcription factors and NLR (nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat) genes show substantial expansions in Rhus species, with 31 WRKY genes significantly upregulated during aphid infestation [6].

- Genomic Clustering: NLR genes cluster on specific chromosomes (4/12) and show signatures of positive selection [6].

- Evolutionary Trajectories: Different evolutionary strategies were observed - Mangifera/Anacardium underwent lineage-specific whole-genome duplications, while Rhus/Pistacia retained only the ancestral gamma duplication [6].

- Transposable Element Activation: Long terminal repeat retrotransposons exhibited Pleistocene-era activation bursts, potentially linked to climatic adaptation [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Comparative Genomics for Gene Family Analysis

Purpose: To identify expanded/contracted gene families and correlate with phenotypic adaptations.

Materials:

- High-quality genome assemblies for multiple related species

- High-performance computing cluster

- OrthoFinder software (v2.5.5+) [5]

- BUSCO (v5.8.2+) for genome quality assessment [5]

- R packages for statistical analysis and visualization

Procedure:

- Genome Quality Assessment

- Assess completeness using BUSCO with lineage-appropriate databases

- Filter annotations to retain only the longest transcript per gene

- Verify consistency of gene naming formats across genomes

Orthogroup Identification

- Run OrthoFinder with default parameters:

OrthoFinder -f [fasta_directory] -M msa - Extract orthogroup statistics and single-copy orthologs for phylogeny

- Run OrthoFinder with default parameters:

Gene Family Expansion/Contraction Analysis

- Generate species tree using STAG method from single-copy orthologs [5]

- Calculate gene birth-death rates using CAFE model

- Identify significantly expanded/contracted gene families (p < 0.05)

Functional Enrichment Analysis

- Perform GO enrichment analysis on expanded gene families

- Conduct KEGG pathway mapping for metabolic adaptations

- Correlate gene family expansions with phenotypic data

Expected Results: Identification of lineage-specific gene family expansions correlated with phenotypic adaptations (e.g., digestive genes in Stratiomyidae, defense genes in Anacardiaceae).

Protocol: Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis (GWAMA) for Olfactory Traits

Purpose: To identify genetic variants associated with olfactory perception and dysfunction.

Materials:

- Genotype and phenotype data from multiple cohorts

- Standardized olfactory assessment (e.g., Sniffin' Sticks 12-item test) [16] [17]

- High-performance computing resources

- PLINK (v1.9+) for quality control and association testing [16]

- METAL software for meta-analysis

Procedure:

- Cohort Preparation and Quality Control

Phenotype Harmonization

- Apply consistent olfactory dysfunction definition across cohorts

- Define cases based on 12-item smell identification test scores [16]

- Account for covariates: age, sex, genetic principal components

Association Analysis and Meta-Analysis

- Perform GWAS in each cohort separately using logistic/linear regression

- Meta-analyze results using fixed-effect inverse-variance weighting

- Apply genomic control to correct for residual population stratification

Post-Association Analyses

Expected Results: Identification of genome-wide significant loci (p < 5×10⁻⁸) associated with olfactory function, replication in independent cohorts, and characterization of pleiotropic effects.

Visualization of Genomic Workflows

Diagram 1: Genomic Analysis Workflow for Gene Family Studies. This workflow outlines the key steps from data collection through biological interpretation, highlighting the integration of comparative genomics and association studies.

Diagram 2: From Genomic Changes to Phenotypic Outcomes. This diagram illustrates the mechanistic links between different types of genomic changes and their resulting phenotypic manifestations across the case studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic-Phenotypic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Key Features | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sniffin' Sticks Odor Identification Test | Olfactory phenotyping | 12-16 item odor identification test, standardized assessment | Human olfactory GWAS [16] [17] |

| OrthoFinder Software | Orthogroup inference | Scalable orthogroup assignment, species tree inference | Comparative genomics of Stratiomyidae and Asilidae [5] |

| Earl Grey TE Annotation Pipeline | Transposable element analysis | Integrates RepeatMasker and RepeatModeler2 | TE analysis in Anacardiaceae [5] [6] |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | Whole genome sequencing | Clinical-grade sequencing, ≥30× mean coverage | All of Us Research Program [18] |

| 10X Visium Spatial Transcriptomics | Spatial gene expression | RNA-templated ligation, spatial barcode mapping | PERTURB-CAST method [19] |

| PLINK | Genotype data analysis | Quality control, association testing, data management | GWAS quality control [16] |

This application note demonstrates how integrating comparative genomics, genome-wide association studies, and functional validation enables researchers to bridge the gap between genomic variation and complex phenotypes. The case studies highlight conserved evolutionary principles: gene family expansions through duplication mechanisms create genetic raw material for adaptation, whether for digestive specialization in insects, olfactory perception in humans, or defense responses in plants. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks provided here offer researchers comprehensive methodologies for investigating genotype-phenotype relationships in their own systems, accelerating discovery in functional genomics and providing foundations for translational applications in medicine and biotechnology.

The Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) family of enzymes represents a critical interface between organisms and their chemical environments, processing both exogenous compounds like pharmaceuticals and toxins, and endogenous substances including lipids, hormones, and neurotransmitters [20]. The evolutionary trajectories of these drug-metabolizing enzymes have been shaped by complex interactions between endogenous physiological requirements and exogenous environmental pressures. Gene family evolution analysis reveals that these enzymes have undergone significant expansion and contraction through processes like tandem duplication and retroposition, with differential selective pressures acting on various sub-families [21] [22]. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics through comparative genomic approaches provides fundamental insights for predicting drug response variability and advancing personalized medicine.

Quantitative Framework for Gene Family Evolution Analysis

Birth-Death Models in Evolutionary Analysis

Stochastic birth-death (BD) processes provide a statistical null model for quantifying gene family evolution, enabling researchers to distinguish random duplication and loss events from those driven by natural selection [23]. This model incorporates branch lengths from phylogenetic trees along with duplication and deletion rates, establishing expectations for gene family size divergence among lineages [23]. The birth-death model can be represented as a probabilistic graphical model that computes the likelihood of observed gene family data across species, allowing inference of ancestral states and identification of lineage-specific expansions or contractions [23].

Table 1: Estimated Gene Duplication and Loss Rates in Vertebrates

| Lineage | Duplication Rate (×10⁻³ per gene/MY) | Loss Rate (×10⁻³ per gene/MY) | Data Source | Time Frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 0.515-1.49 | 7.40 | Genome-wide analysis [21] | Last 200 MY |

| Mouse | 1.23-4.23 | 7.40 | Genome-wide analysis [21] | Last 200 MY |

| Vertebrates | 1.15 | 7.40 | Constant-rate birth-death model [24] | Last 200 MY |

Mechanisms of Gene Duplication

Different duplication mechanisms contribute unequally to the evolution of gene families. Unequal crossover generates tandemly arrayed genes, while retroposition creates dispersed duplicates through RNA intermediates [21]. These mechanisms operate independently and show different retention patterns, with unequal crossover contributing more significantly to the overall duplication content in mammalian genomes [21].

Table 2: Relative Contributions of Duplication Mechanisms in Mammals

| Mechanism | Contribution to Entire Genome | Contribution to Two-Copy Families | Sensitivity to Gene Conversion | Retention Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unequal Crossover | ~20% of genes [21] | Significantly less [21] | High [21] | Higher [21] |

| Retroposition | Substantial (exact % not specified) | Moderate [21] | Low [21] | Lower [21] |

| Genome Duplication | Negligible for recent duplications [21] | Negligible for recent duplications [21] | Varies | High for ancient events |

Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary Analysis of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes

Phylogenetic Gene Family Analysis

Objective: Reconstruct evolutionary history of drug-metabolizing enzyme gene families to identify expansion/contraction patterns and selective pressures.

Workflow:

- Gene Family Identification: Retrieve sequences of interest from genomic databases using conserved domain searches or homology-based methods

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Generate alignments using tools like ClustalW with default parameters, followed by manual curation to remove fragments and ensure alignment quality [24]

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction:

- Molecular Dating: Apply non-parametric rate smoothing (e.g., using R8s software) to generate ultrametric trees, calibrating with known speciation nodes [24]

- Duplication Event Mapping: Analyze ultrametric trees in applications like GeneTree to identify dates and locations of gene duplication events on species trees [24]

Humanized CYP450 Mouse Model Development

Objective: Create in vivo models expressing human drug-metabolizing enzymes to study human-specific metabolic profiles [25].

Workflow:

- Gene Targeting: Use embryonic stem cell targeting and CRISPR-Cas9 technology to insert human wild-type CYP2D6 gene while knocking out the mouse Cyp2d locus [25]

- Model Validation:

- Exogenous Metabolism Profiling:

- Conduct pharmacokinetic studies with substrate probes

- Analyze tissue distribution and in situ metabolism of humanized enzyme [25]

- Endogenous Metabolite Characterization: Perform untargeted and quantitative metabolomics comparing endogenous substance metabolism between humanized and wild-type models [25]

- Biomarker Identification: Identify significantly differentially regulated metabolites associated with enzyme activity changes (e.g., triglyceride TG(14:022:622:6) for CYP2D6) [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Evolutionary and Functional Analysis of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| ClustalW | Multiple sequence alignment generation | Creating alignments for phylogenetic reconstruction [24] |

| Tree-Puzzle | Maximum-likelihood distance estimation | Calculating genetic distances between sequences with rate heterogeneity modeling [24] |

| R8s Software | Molecular dating of evolutionary events | Applying non-parametric rate smoothing to generate ultrametric trees [24] |

| GeneTree | Gene duplication mapping and analysis | Identifying duplication events on species trees [24] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Genome editing for model development | Creating humanized CYP450 mouse models [25] |

| Metoprolol | CYP2D6 substrate probe | Assessing enzyme activity and metabolic capacity in humanized models [25] |

| HPLC-MS/MS | Metabolite identification and quantification | Untargeted and targeted metabolomics in model systems [25] |

Integration of Multi-Omics and Artificial Intelligence

Advanced computational approaches are revolutionizing our ability to interpret the evolutionary dynamics of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Multi-omics integration captures genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data layers, providing a comprehensive view of patient-specific biology [26]. Artificial intelligence methods, including deep neural networks and graph neural networks, enhance this landscape by detecting hidden patterns in complex datasets, filling gaps in incomplete data, and enabling in silico simulations of treatment responses [26]. These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding how gene-gene and gene-environment interactions shape therapeutic outcomes across diverse populations [26].

Exposome Influence on CYP450 Enzyme Evolution and Function

The exposome—the cumulative measure of environmental influences and biological responses throughout lifespan—significantly shapes CYP450 function and evolution [20]. Key exposome components include:

- External Factors: Dietary substances (e.g., grapefruit juice inhibiting CYP3A4), lifestyle choices, environmental pollutants (e.g., tobacco smoke inducing CYP1A1/1A2), and pharmaceuticals [20]

- Internal Factors: Gut microbiota composition, hormone fluctuations, disease states, oxidative stress, and inflammation [20]

These exposures modify CYP450 expression and activity through molecular pathways that connect environmental cues to alterations in drug metabolizing enzymes, creating dynamic interindividual variability that cannot be explained by genetic polymorphisms alone [20]. The ongoing adaptation of drug-metabolizing enzymes to changing environmental pressures illustrates the continuous interplay between exogenous and endogenous evolutionary drivers.

The differential evolution of drug-metabolizing enzymes reflects complex interactions between endogenous physiological requirements and exogenous environmental pressures. Birth-death models applied to gene family evolution provide a statistical framework for identifying significant expansion and contraction events, revealing both neutral evolution and selective adaptation in enzyme families. The integration of phylogenetic methods with functional studies in humanized models offers powerful insights into the evolutionary forces shaping pharmacogenomic variation. As multi-omics technologies and artificial intelligence approaches mature, they promise to further illuminate the intricate evolutionary history of these critical enzymes, enabling more precise prediction of drug responses and advancing the goals of personalized medicine.

Application Notes

Core Evolutionary Forces in Gene Family Analysis

The analysis of gene family expansion and contraction relies on understanding three fundamental evolutionary forces: purifying selection, positive selection, and neutral drift. These forces shape gene sequences and copy numbers over time, creating distinct genomic signatures that can be detected through comparative genomics and statistical analysis. Purifying selection conserves essential functions by removing deleterious mutations, while positive selection drives adaptive evolution by favoring beneficial variants. Neutral drift allows for the random fluctuation of mutation frequencies, particularly in regions not under strong selective constraints [27] [28].

Biological Significance in Genomic Studies

In the context of gene family evolution, these forces explain observed patterns of gene gain and loss. For example, gene families involved in critical cellular processes typically show strong purifying selection with minimal changes between distantly related species [27]. Conversely, families experiencing repeated gene duplications and functional diversification, such as those involved in digestion, immunity, and olfactory functions in black soldier flies, often show signatures of positive selection and adaptive expansion [5]. Neutral processes, including constructive neutral evolution (CNE), can explain the emergence of non-adaptive complexity through mechanisms like gene duplication followed by subfunctionalization [28].

Quantitative Framework for Selection Analysis

The standard metric for detecting selection pressure is the dN/dS ratio (also denoted as ω), which compares the rate of non-synonymous substitutions (dN, altering amino acid sequence) to synonymous substitutions (dS, functionally neutral) [27] [29]. This ratio serves as a molecular clock for neutral evolution, with significant deviations indicating selective pressures.

Table 1: Interpretation of dN/dS Ratios and Statistical Signals

| Evolutionary Force | dN/dS Value | Statistical Signature | Genomic Pattern in Gene Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purifying Selection | dN/dS < 1 | Significant excess of synonymous over non-synonymous changes | Few functional changes between distant species; gene sequence conservation [27] |

| Positive Selection | dN/dS > 1 | Significant excess of non-synonymous over synonymous changes | Excess of functional changes; radical amino acid substitutions in specific lineages [27] |

| Neutral Drift | dN/dS = 1 | Non-synonymous and synonymous changes occur at equal rates | Mutation accumulation proportional to neutral expectations; no significant functional constraint [27] |

Table 2: Correlation Between Evolutionary Forces and Genomic Features

| Evolutionary Force | Impact on Genome Size | Effect on Transposable Elements | Role in Gene Family Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purifying Selection | Constrains genome size by removing deleterious insertions | Suppresses TE accumulation through selective removal [29] | Maintains gene functional integrity; prevents unnecessary expansion [27] |

| Positive Selection | Can increase genome size through adaptive duplications | May utilize TE-derived sequences for novel regulatory functions | Drives gene family expansion through selective advantage of duplicates [5] |

| Neutral Drift | Permits genome size increase through neutral accumulation | Allows TE proliferation when selection is ineffective [29] | Enables subfunctionalization and non-adaptive complexity through CNE [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Detection of Selection Forces in Gene Family Evolution

Objective and Principle

This protocol outlines a computational workflow to identify signatures of purifying selection, positive selection, and neutral drift in gene families using comparative genomic data. The approach relies on ortholog identification, sequence alignment, and evolutionary model testing to detect deviations from neutral expectations [5] [30].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup inference across multiple species | Identies groups of orthologous genes; prerequisite for comparative analysis [5] |

| BUSCO | Assessment of genome completeness | Evaluates assembly quality; ensures reliable gene content analysis [5] |

| CodeML (PAML package) | dN/dS calculation and selection detection | Implements codon substitution models; tests site-specific or branch-specific selection [29] |

| Variance Component Models | Association testing in familial data | Accounts for kinship in population-based studies; controls for relatedness [31] |

| Earl Grey/RepeatMasker | Transposable element annotation | Identifies repetitive elements; assesses TE content correlation with selection efficacy [5] [29] |

| GENESPACE | Synteny analysis across genomes | Visualizes genomic context and identifies conserved gene blocks [5] |

Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Obtain genome assemblies and annotation files (GFF/GTF format) for all study species.

- Assess genome completeness using BUSCO with lineage-specific datasets (e.g., diptera_odb10 for flies) [5].

- Filter gene annotations to retain only primary transcripts using tools like the

primary_transcript.pyscript from OrthoFinder [5].

Step 2: Ortholog Identification and Alignment

- Run OrthoFinder with protein sequences from all species to identify orthogroups.

- Extract single-copy orthologs for phylogenetic construction and multi-copy gene families for expansion/contraction analysis.

- Generate multiple sequence alignments for target gene families using appropriate tools (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE).

- Curate alignments to remove poorly aligned regions using tools like Gblocks or trimAl.

Step 3: Phylogenetic Tree Construction

- Construct a species tree using single-copy orthologs with the STAG method in OrthoFinder [5].

- Build gene trees for each gene family of interest using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., RAxML, IQ-TREE).

- Compare gene trees with species tree to identify discordance suggesting selective pressures.

Step 4: Selection Analysis using dN/dS Ratios

- Prepare codon-aligned sequences for orthologous gene sets.

- Run CodeML with different evolutionary models:

- Site models to identify specific amino acid positions under positive selection.

- Branch models to detect lineages with elevated evolutionary rates.

- Branch-site models to identify positive selection affecting specific sites on particular lineages.

- Compare nested models using likelihood ratio tests with significance threshold of p < 0.05.

- Correct for multiple testing using False Discovery Rate (FDR) methods.

Step 5: Gene Family Expansion/Contraction Analysis

- Estimate gene birth and death rates across phylogeny using CAFE software.

- Identify significantly expanded or contracted gene families relative to background rates.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., GO term enrichment) on expanded families to identify biological processes under selection [5].

Step 6: Integration with Genomic Features

- Annotate transposable elements using Earl Grey or RepeatMasker pipelines [5].

- Correlate TE content with dN/dS ratios using phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) to test for relaxed selection [29].

- Perform synteny analysis using GENESPACE to identify conserved genomic contexts [5].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Purifying Selection Signature: Significantly lower dN/dS across most sites with conserved gene copy numbers and strong syntenic conservation.

- Positive Selection Signature: Significantly elevated dN/dS at specific sites or lineages coupled with gene family expansion and functional diversification [5].

- Neutral Drift Signature: dN/dS not significantly different from 1 with random patterns of gene gain and loss without functional enrichment.

Protocol: Experimental Evolution to Study Neutral Drift and Threshold Selection

Objective and Principle

This protocol describes an experimental evolution approach to investigate how neutral drift under threshold-like selection promotes phenotypic variation, as demonstrated in β-lactamase antibiotic resistance evolution [32]. The principle leverages non-linear relationships between phenotype and fitness, where variants above a functional threshold have equal fitness despite phenotypic differences.

Materials and Reagents

- Gene of interest (e.g., VIM-2 β-lactamase)

- Escherichia coli expression system

- Selective agent (e.g., ampicillin)

- Mutagenesis reagents (e.g., error-prone PCR kit)

- Agar plates with concentration gradients of selective agent

- Growth media and incubation facilities

Procedure

Step 1: Establish Baseline Phenotype

- Clone gene of interest into expression vector.

- Transform into host organism (e.g., E. coli).

- Determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of selective agent for wild-type gene.

Step 2: Design Evolutionary Trajectories

- Adaptive Walk (AW): Apply gradually increasing concentrations of selective agent over multiple rounds.

- Neutral Drift at High Concentration (NDHi): Maintain constant high selective pressure (e.g., 4× MIC of wild-type).

- Neutral Drift at Low Concentration (NDLo): Maintain constant low selective pressure (e.g., 20-fold below MIC of wild-type) [32].

Step 3: Perform Evolution Experiment

- For each round, apply mutagenesis to gene library (e.g., error-prone PCR).

- Plate library on selective media at designated concentration.

- Harvest sufficient colonies (e.g., 1000 CFUs) to maintain diversity.

- Extract gene variants for subsequent round.

- Continue for 100+ rounds for neutral drift lineages [32].

Step 4: Phenotypic Characterization

- For each population, perform dose-response assays to determine EC10, EC50, and EC90 values.

- Calculate phenotypic diversity metric: EC90/EC10 ratio.

- Iscrete individual variants and determine MIC values.

- Correlate population-level diversity metrics with individual variant characteristics [32].

Step 5: Genotypic Analysis

- Sequence representative variants from each population.

- Calculate genetic diversity metrics (e.g., amino acid sequence divergence from wild-type).

- Estimate selection pressure using Na/Nt ratio (nonsynonymous/synonymous mutations) [32].

Visualizations

Workflow for Gene Family Selection Analysis

Evolutionary Forces and Genomic Signatures

Experimental Evolution for Neutral Drift

The Analytical How: A Step-by-Step Guide to Bioinformatics Tools and Pipelines

OrthoFinder is a fast, accurate, and comprehensive platform for comparative genomics that solves fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons through phylogenetic orthology inference. Unlike heuristic methods that rely solely on sequence similarity scores, OrthoFinder implements a novel phylogenetic approach that infers rooted gene trees for all orthogroups, identifies gene duplication events, and reconstructs the rooted species tree for the analyzed species [33] [34]. This represents a significant methodological advancement over traditional approaches such as OrthoMCL, which exhibited substantial gene length bias in orthogroup detection, resulting in low recall rates for short sequences and low precision for long sequences [35]. According to independent benchmarks on the Quest for Orthologs reference dataset, OrthoFinder demonstrates 3-30% higher ortholog inference accuracy compared to other methods, establishing it as the most accurate orthology inference method available [34].

The core concept of orthogroup inference addresses the critical need to identify homology relationships between sequences across multiple species. An orthogroup represents the set of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of all species being analyzed, containing both orthologs and paralogs [35]. This phylogenetic framework provides the foundation for comparative genomics, enabling researchers to trace evolutionary relationships, understand gene family evolution, and extrapolate biological knowledge between organisms. OrthoFinder's implementation provides unprecedented accuracy in resolving these relationships through its unique integration of graph-based clustering and phylogenetic tree inference.

Table 1: Key Advantages of OrthoFinder Over Traditional Methods

| Feature | Traditional Methods (e.g., OrthoMCL) | OrthoFinder |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Sequence similarity heuristics | Phylogenetic gene trees |

| Gene Length Bias | Significant bias affecting accuracy | Solved via novel score normalization |

| Ortholog Inference | Pairwise similarity scores | Gene tree-based with duplication events |

| Output Comprehensiveness | Basic orthogroups | Orthogroups, gene trees, species tree, duplication events |

| Benchmark Accuracy | Lower F-scores | 3-30% higher accuracy on reference datasets |

Installation and Implementation Framework

System Requirements and Installation

OrthoFinder is implemented in Python and can be installed on Linux, Mac, and Windows systems. The recommended installation method is via Bioconda, which automatically handles dependencies:

Alternative installation methods include downloading precompiled bundles or source code directly from the GitHub repository [33]. For Windows users, the most efficient approach utilizes the Windows Subsystem for Linux or Docker containers. The software requires input files in FASTA format containing protein sequences for each species to be analyzed, with supported extensions including .fa, .faa, .fasta, .fas, and .pep [33].

Core Algorithmic Innovations

OrthoFinder introduces two fundamental algorithmic improvements that address critical limitations in traditional orthogroup inference methods. First, it implements a novel score transformation that eliminates gene length bias in BLAST scores. This transformation uses linear modeling in log-log space to normalize bit scores across different sequence lengths, ensuring equivalent scores for orthologous sequences regardless of length variations [35]. Second, OrthoFinder employs reciprocal best BLAST hits using these length-normalized scores to construct the orthogroup graph with significantly improved precision and recall rates [35].

The phylogenetic framework of OrthoFinder extends beyond basic orthogroup inference through several key processes: (a) orthogroup inference from sequence data, (b) inference of gene trees for each orthogroup, (c-d) analysis of gene trees to infer the rooted species tree, (e) rooting of gene trees using the species tree, and (f-h) duplication-loss-coalescence analysis of rooted gene trees to identify orthologs and gene duplication events [34]. This comprehensive approach enables OrthoFinder to provide a complete phylogenetic interpretation of the relationships between genes across species.

OrthoFinder Protocol for Orthogroup Inference

Input Preparation and Basic Execution

The foundational step in OrthoFinder analysis involves preparing input protein sequences in FASTA format, with one file per species. To execute a basic OrthoFinder analysis:

This command initiates the complete OrthoFinder pipeline, which includes: (1) performing all-vs-all sequence searches using DIAMOND (default) or BLAST, (2) normalizing sequence similarity scores to correct for gene length and phylogenetic distance biases, (3) inferring orthogroups using the MCL algorithm, (4) generating gene trees for each orthogroup, (5) inferring the rooted species tree from the gene trees, and (6) identifying orthologs, paralogs, and gene duplication events [33] [34].

For larger analyses, OrthoFinder provides a scalable workflow option where users can run an initial analysis on a core set of species and subsequently add new species using the --assign option, which directly adds the new species to the previous orthogroups without recomputing the entire analysis [33]. This significantly reduces computational time for incremental analyses.

Advanced Configuration for Specialized Applications

For research requiring higher precision, particularly in studies of gene family expansion and contraction, OrthoFinder provides several advanced configuration options:

This command utilizes 40 CPU threads for both BLAST (-t) and gene tree inference (-a), implements multiple sequence alignment (-M msa) with MAFFT for alignment generation (-A), FastTree for tree inference (-T), and the ultra-sensitive mode of DIAMOND for sequence searches [33]. These parameters are particularly valuable for detecting distant homologs in evolutionary studies and generating high-quality gene trees for accurate duplication event dating.

Table 2: Critical OrthoFinder Parameters for Gene Family Analysis

| Parameter | Default | Alternative | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| -S | diamond | blast, diamondultrasens | Sensitive for distant homologs |

| -M | dendroblast | msa | Higher quality alignments |

| -A | - | mafft, muscle | Alignment method for -M msa |

| -T | - | iqtree, raxml, fasttree | Tree inference method for -M msa |

| -y | False | True | Split hierarchical orthogroups |

| --assign | - | Previous results | Add species to existing analysis |

Output Interpretation and Analytical Applications

Hierarchical Orthogroups and Evolutionary Interpretation

From version 2.4.0 onward, OrthoFinder infers Hierarchical Orthogroups (HOGs) by analyzing rooted gene trees at each node in the species tree. This represents a significantly more accurate orthogroup inference method compared to the graph-based approach used by other methods and earlier versions of OrthoFinder [33]. According to Orthobench benchmarks, these phylogenetically-informed orthogroups are 12-20% more accurate than OrthoFinder's previous orthogroups [33].

The primary output file Phylogenetic_Hierarchical_Orthogroups/N0.tsv contains orthogroups defined at the last common ancestor of all analyzed species. Additional files N1.tsv, N2.tsv, etc., contain orthogroups defined at progressively more specific clades within the species tree. This hierarchical structure enables researchers to trace orthogroup evolution through the species phylogeny, identifying precisely when gene duplications and losses occurred. When outgroup species are included, they significantly improve root inference and consequently increase HOG accuracy by up to 20% [33].

Gene Duplication Analysis and Comparative Genomics

A particularly powerful application for gene family expansion/contraction research is OrthoFinder's ability to identify and map all gene duplication events to both the gene trees and species tree. The Gene_Duplication_Events directory contains comprehensive data on duplication events, including their timing relative to species divergence and their distribution across the genome [34]. This enables researchers to:

- Distinguish between species-specific and shared ancestral duplications

- Identify periods of accelerated gene family expansion in evolutionary history

- Correlate duplication events with evolutionary innovations or environmental adaptations

- Calculate comparative genomics statistics including duplication rates per branch

The Comparative_Genomics_Statistics directory provides precomputed statistics including orthogroup sizes per species, gene counts per orthogroup, and percentages of species-specific, core, and shared orthogroups, facilitating immediate comparative analyses across species [33] [34].

Research Reagent Solutions for Orthogroup Analysis

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Orthogroup-Based Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Orthogroup Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic orthology inference | Core analysis platform for orthogroup identification |

| DIAMOND | Accelerated sequence similarity | Default search tool for all-vs-all comparisons |

| MCL | Markov clustering algorithm | Graph-based clustering of normalized scores |

| DendroBLAST | Rapid gene tree inference | Default method for gene tree construction |

| MAFFT/MUSCLE | Multiple sequence alignment | Alternative alignment methods for precision |

| FastTree/RAxML | Phylogenetic inference | Alternative tree inference methods |

| BUSCO | Genome completeness assessment | Complementary quality assessment tool [36] |

Integration with Gene Family Expansion/Contraction Research

For thesis research focused on gene family expansion and contraction analysis, OrthoFinder provides critical foundational data. The orthogroups identified serve as the evolutionary units for tracking gene family dynamics across species. The gene duplication events mapped to the species tree identify precisely when expansions occurred, while orthogroup size variations across species reveal contractions through gene loss [34].

Recent studies have demonstrated the power of this approach in diverse biological contexts. Research on transposable element evolution has utilized network analyses of orthogroup data to reveal how epigenetic silencing mechanisms shape TE content across species [37]. Similarly, investigations of male germ cell development have employed orthogroup-based phylostratigraphy to identify an ancient, conserved genetic program underlying spermatogenesis across metazoans [38]. These applications highlight how OrthoFinder-derived orthogroups provide the evolutionary framework for understanding gene family dynamics in diverse biological processes.

When designing experiments for gene family analysis, researchers should consider incorporating multiple closely-related and divergent species to improve orthogroup inference accuracy. The inclusion of outgroup species significantly enhances root inference in gene trees, which is particularly important for accurate dating of duplication events [33]. Additionally, leveraging the hierarchical orthogroup structure enables researchers to focus analyses on specific clades of interest while maintaining evolutionary context from broader taxonomic sampling.

Identifying Repetitive Elements and Transposable Elements with Earl Grey and RepeatMasker

The comprehensive annotation of transposable elements (TEs) represents a critical foundation for genomic studies focused on gene family evolution. These repetitive sequences, often constituting large portions of eukaryotic genomes, significantly influence genomic architecture and can drive expansions and contractions in gene families through various mutational mechanisms [39]. Accurate TE identification enables researchers to distinguish genuine gene family changes from artifacts caused by undetected repetitive elements. This protocol details two complementary approaches for TE annotation—Earl Grey, a recently developed fully automated pipeline, and RepeatMasker, an established standard in the field—both of which provide essential data for interpreting evolutionary patterns in gene families.

Within the context of gene family analysis, TEs can directly contribute to evolutionary dynamics. Recent research on blood-feeding insects revealed that specific gene families like heat shock proteins (HSP20) and chemosensory proteins underwent convergent expansions in independently-evolved hematophagous lineages, while other families experienced contractions [40]. Similarly, studies of Mycobacterium species demonstrated that gene family contraction represents a primary genomic alteration associated with growth rate and pathogenicity transitions [41]. These findings underscore the importance of robust TE annotation as a prerequisite for accurate evolutionary inference.

Tool Selection and Comparative Performance

Selecting appropriate TE annotation tools requires careful consideration of research objectives, genomic context, and technical expertise. RepeatMasker represents the longstanding benchmark for homology-based TE detection, utilizing curated libraries such as Dfam and Repbase to identify repetitive elements through sequence similarity [42]. In contrast, Earl Grey is a recently developed, fully automated pipeline specifically designed to address common challenges in TE annotation, including fragmented annotations and poor capture of TE terminal regions [43].

The choice between these tools depends on several factors. For established model organisms with comprehensive TE libraries, RepeatMasker offers proven reliability and extensive community support. For non-model organisms or projects requiring minimal manual curation, Earl Grey's automated approach provides significant advantages. Many researchers employ both tools in complementary workflows, using Earl Grey for de novo annotation and RepeatMasker for library-based classification.

Performance Comparison and Technical Considerations

Benchmarking analyses using simulated genomes and Drosophila melanogaster annotations demonstrate that Earl Grey outperforms existing methodologies in reducing annotation fragmentation and improving terminal sequence capture while maintaining high classification accuracy [43]. The pipeline specifically addresses issues of overlapping TE annotations that can lead to erroneous estimates of TE count and coverage—a critical consideration for gene family studies where accurate copy number quantification is essential.

RepeatMasker continues to be actively developed, with recent updates enhancing its functionality. Version 4.1.7 introduced the ability to use custom TE libraries without additional database downloads, while version 4.1.6 adopted the partitioned FamDB format featured in Dfam 3.8 [42]. These improvements maintain RepeatMasker's relevance in evolving genomic research contexts.

Table 1: Comparative Tool Specifications for TE Annotation

| Feature | Earl Grey | RepeatMasker |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Fully automated curation and annotation | Homology-based screening against curated libraries |

| Library Dependencies | Integrated (Dfam) | Dfam, Repbase, or custom libraries |

| Key Advantage | Reduced fragmentation, improved end coverage | Extensive curation, established community standards |

| Output Format | Standard formats, paper-ready summary figures | Detailed annotation tables, modified sequences |

| Ideal Use Case | Non-model organisms, automated workflows | Model organisms, manual curation pipelines |

| Recent Updates | Initial release (2024) [43] | Continuous updates (4.2.2 in 2025) [42] |

Experimental Protocols

Earl Grey Protocol for Automated TE Annotation

Earl Grey provides a user-friendly, automated solution for TE annotation that requires minimal bioinformatics expertise while delivering comprehensive results.

Software Installation and Setup:

Genome Assembly Preparation:

- Input: Genome assembly in FASTA format

- Quality control: Assess assembly completeness using BUSCO scores (target: ≥95%) [44]