gDNA vs. cfDNA in NGS for Chemogenomics: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of genomic DNA (gDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) based Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methodologies within chemogenomic studies.

gDNA vs. cfDNA in NGS for Chemogenomics: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of genomic DNA (gDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) based Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methodologies within chemogenomic studies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology and distinct origins of these analytes—gDNA from intact cells and cfDNA from apoptotic or necrotic cells. The scope covers their methodological applications from target discovery to treatment monitoring, addresses key challenges like host DNA depletion and low cfDNA yield, and offers a direct performance comparison on sensitivity, specificity, and clinical utility. By synthesizing current trends and data, this guide aims to inform strategic decisions in assay selection to accelerate precision medicine and oncology research.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding the Origins and Characteristics of gDNA and cfDNA

In chemogenomic studies and drug development, the choice of genetic analyte is fundamental. Genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated from cellular nuclei and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) circulating in blood plasma represent two distinct sources of biological information with different origins, characteristics, and applications [1]. gDNA provides a comprehensive blueprint of an organism's genetic makeup, typically extracted from intact cells. In contrast, cfDNA consists of short, fragmented DNA molecules released into bodily fluids through cellular processes such as apoptosis and necrosis [2] [1]. These differences directly influence their utility in research settings, particularly for next-generation sequencing (NGS) applications in cancer research, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic monitoring.

The fragmentation pattern of cfDNA is non-random and provides a rich source of biological information. The most frequent fragment size is approximately 167 base pairs (bp), corresponding to DNA wrapped around a single histone complex [2]. Other complexes like transcription factors and transcription machinery also protect DNA from degradation, resulting in unique fragmentation patterns specific to genomic locations where these complexes are bound [2]. This fragmentomics data can infer epigenetic and transcriptional information about the tissue of origin, which is particularly valuable in cancer research for identifying tumor subtypes and responses to treatment.

Fundamental Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

gDNA and cfDNA differ significantly in their physical properties, molecular origins, and the type of biological information they yield. The table below summarizes the key distinctions between these two analytes:

Table 1: Core Characteristics of gDNA vs. cfDNA

| Characteristic | gDNA from Cellular Nuclei | cfDNA as Circulating Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

| Source Material | Intact cells (tissue biopsies, blood cells) | Bodily fluids (plasma, serum, CSF) [1] |

| Isolation Difficulty | Moderate (requires cellular material) | High (low concentration, requires careful handling) [1] |

| DNA Fragment Size | Long, high molecular weight strands | Short, fragmented (∼167 bp is most common) [2] |

| Primary Origin | Nuclei of all sampled cells | Apoptosis, necrosis of various cells [1] |

| Tumor Representation | Limited to sampled tissue site | May represent heterogeneous tumor clones [3] |

| Application in NGS | Whole genome, exome, targeted sequencing | Liquid biopsy, fragmentomics, methylation studies [2] [3] |

The analytical approaches for gDNA and cfDNA have diverged to leverage their unique properties. gDNA is typically used for comprehensive variant discovery, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs) across the entire genome or exome [3]. cfDNA analysis, while also used for variant detection, has expanded to include fragmentomics—the study of DNA fragmentation patterns—which can infer epigenetic and transcriptional data from the cell of origin [2]. Additionally, methylation profiling of cfDNA is increasingly used for cancer detection and monitoring, as methylation changes are early events in tumorigenesis [4].

Table 2: Analytical Approaches for gDNA and cfDNA in NGS

| Analytical Method | gDNA Applications | cfDNA Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Calling | Primary application (SNVs, indels, CNVs) [3] | Possible but limited by low tumor fraction [4] |

| Fragmentomics | Not applicable | Emerging method for inferring epigenetic state [2] |

| Methylation Analysis | Possible but requires bisulfite conversion | Tumor-agnostic detection; early cancer signals [4] |

| Copy Number Analysis | Standard approach | Possible via shallow whole-genome sequencing [4] |

Experimental Protocols: From Sample to Data

Sample Collection and Isolation Methods

Proper sample collection and processing is particularly critical for cfDNA analysis due to its low concentration in circulation. For cfDNA isolation from blood, samples should be collected in tubes containing stabilizers (e.g., EDTA, Streck, or CellSave tubes) and processed within a narrow timeframe (within 4 hours for EDTA tubes up to 96 hours for CellSave/Streck tubes) [4]. Plasma must be separated through a two-step centrifugation process to remove intact cells and debris [4] [1]. The choice of extraction methodology significantly impacts cfDNA yield and quality, with automated systems like the Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit demonstrating high efficiency and reproducibility compared to manual kits [1] [5].

For gDNA isolation from tissue, the process begins with tissue homogenization followed by cell lysis. DNA is then purified using various methods including silica-based membrane columns, magnetic beads, or organic extraction, with quality and quantity assessed via spectrophotometry or fluorometry [6].

DNA Quantification Methods

Accurate DNA quantification is essential for successful NGS library preparation. The table below compares common quantification methods:

Table 3: DNA Quantification Methods for NGS Applications

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Absorption of UV light by nucleic acids [6] | Low (2-5 ng/μL) | Concentration; protein/salt contamination [6] |

| Fluorometry | Fluorescent dyes binding to dsDNA [6] | High (<0.5 ng/μL) | Specific dsDNA concentration [6] |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitioning and endpoint PCR detection [7] | Very High (single copy) | Absolute quantification of specific targets [7] |

| qPCR | Real-time fluorescence during PCR [7] | High | Relative quantification via standard curve [7] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | Electrokinetic separation in capillaries [6] | Moderate | Size distribution and quantitation [6] |

Digital PCR has demonstrated superior sensitivity and quantification precision, particularly at low DNA concentrations (<1 copy/μL), making it especially suitable for cfDNA analysis and rare mutation detection [7].

Sequencing Approaches and Workflows

NGS applications for both gDNA and cfDNA can be divided into several approaches: whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), targeted sequencing panels, and RNA sequencing [3] [8]. For cfDNA, two additional approaches are metagenomic sequencing (mNGS) and targeted NGS (tNGS) [9].

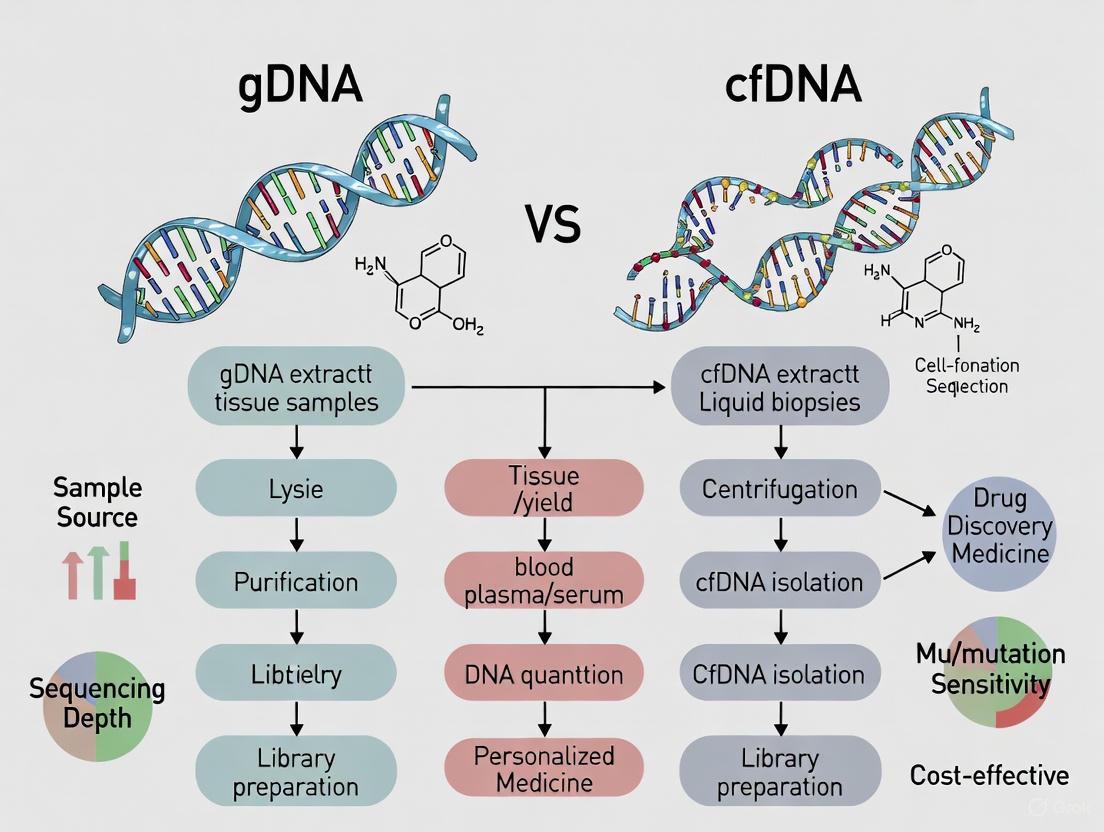

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for preparing gDNA and cfDNA for NGS analysis:

For targeted NGS panels—commonly used in clinical settings for their cost-effectiveness and high coverage depth—the process involves either amplicon-based or hybridization capture-based approaches to enrich for genes of interest before sequencing [3]. Fragmentomics analysis, an emerging application for cfDNA, utilizes various metrics including fragment length proportions, normalized fragment read depth, end motif diversity, and patterns around transcription factor binding sites or open chromatin regions to infer epigenetic information [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Kits

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for DNA Isolation and Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Manual cfDNA isolation from plasma | High efficiency; labor-intensive [1] [5] |

| Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit | Automated cfDNA isolation | High yield; reproducible [1] [5] |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | gDNA isolation from tissues/cells | Standard for cellular DNA extraction [7] |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Fluorometric DNA quantification | Specific for dsDNA; highly sensitive [1] |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Fragment size analysis | Essential for cfDNA quality control [1] |

| Digital PCR Systems | Absolute DNA quantification | Superior for low-abundance targets [7] [1] |

Application in Chemogenomic Studies and Cancer Research

In chemogenomic studies, gDNA and cfDNA offer complementary insights. gDNA from tumor biopsies remains the gold standard for comprehensive molecular profiling, enabling the detection of a wide variety of genetic alterations and providing material for transcriptomic and proteomic analyses [3]. However, cfDNA analysis through liquid biopsies addresses several limitations of tissue biopsies, including invasiveness, tumor heterogeneity, and the inability to perform serial monitoring [1].

Fragmentomics-based analysis of cfDNA has recently emerged as a powerful method for cancer phenotyping. Research has demonstrated that multiple fragmentomics metrics can predict cancer types and subtypes using commercially available targeted sequencing panels, with normalized read depth across all exons providing the best overall performance (AUROC of 0.943-0.964 across cohorts) [2]. This approach successfully differentiates between various cancer types (bladder, breast, prostate, renal cell, lung) and subtypes (ER-positive vs. ER-negative breast cancer, adenocarcinoma vs. neuroendocrine prostate cancer) [2].

The following diagram illustrates how gDNA and cfDNA analysis can be integrated in cancer research and therapeutic monitoring:

For therapeutic monitoring, cfDNA offers unique advantages. Studies have shown that changes in ctDNA levels during neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for breast cancer are associated with treatment response and survival outcomes [4]. Tumor-agnostic methods for ctDNA detection, including methylation profiling (MeD-Seq) and fragmentomics, show promise for monitoring treatment response without requiring prior knowledge of tumor-specific mutations [4].

gDNA from cellular nuclei and cfDNA as a circulating biomarker represent complementary analytes that together provide a more complete picture of tumor genetics and dynamics in chemogenomic research. gDNA remains essential for comprehensive initial molecular profiling, while cfDNA enables non-invasive serial monitoring of treatment response and clonal evolution. The emerging field of fragmentomics adds another dimension to cfDNA analysis, allowing inference of epigenetic information from fragmentation patterns.

The choice between these analytes depends on research objectives, sample availability, and required sensitivity. As isolation methods improve and sequencing costs decrease, the integration of both gDNA and cfDNA analysis will likely become standard practice in precision oncology and chemogenomic studies, providing a holistic approach to understanding tumor biology and therapeutic response.

In the landscape of chemogenomic studies and drug development, the choice of genetic material for next-generation sequencing (NGS) is pivotal. While genomic DNA (gDNA) has traditionally been the cornerstone of genetic analysis, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as a powerful alternative, offering a non-invasive window into physiological and pathological states. The biological origins of cfDNA—primarily through apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion—fundamentally shape its characteristics and analytical utility. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to appropriately select and interpret gDNA-based versus cfDNA-based NGS approaches. This guide objectively compares these DNA sources within chemogenomic research, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform your study designs.

Core Release Mechanisms of cfDNA

Cell-free DNA is released into bodily fluids through distinct pathways, each imparting unique molecular signatures. These origins influence fragment characteristics, molecular features, and ultimately, the applications in clinical and research settings.

Apoptotic Cell Death

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is a major source of cfDNA, particularly in healthy individuals [10]. This process is executed by caspases, leading to cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and systematic fragmentation of cellular contents [10].

- Mechanism: During apoptosis, caspase-activated nucleases (such as CAD, DNaseI L-3, NM23-H1, and EndoG) are activated. These enzymes cleave DNA at internucleosomal regions, creating fragments wrapped around nucleosomal structures [10].

- Fragment Characteristics: Apoptosis produces cfDNA with a distinctive ladder-like pattern on gel electrophoresis. The dominant fragment size is approximately 167 base pairs (bp), which corresponds to the length of DNA wrapped around one nucleosome (147 bp) plus a linker DNA [10] [11]. This population is often described as short-sized fragments.

- Biological Significance: As the primary source of background cfDNA in circulation, apoptotic fragments form the baseline against which tumor-derived signals must be detected. In chemogenomic studies, drugs that induce apoptosis may cause a transient increase in this short-fragment cfDNA population.

Necrotic Cell Death

Necrosis is an unprogrammed form of cell death resulting from cellular damage, often prevalent in tumor microenvironments due to factors like hypoxia and nutrient deprivation [10].

- Mechanism: Unlike the controlled process of apoptosis, necrosis involves organelle dysfunction and plasma membrane rupture, leading to the random release of cellular contents, including DNA, into the extracellular space [10]. This DNA is exposed to intracellular and extracellular degradative agents.

- Fragment Characteristics: Necrosis releases longer, more heterogeneous DNA fragments, ranging up to many kilo-base pairs (kbp) in size [10] [11]. The fragmentation is non-systematic.

- Biological Significance: The presence of longer cfDNA fragments can indicate pathological conditions, such as tumor progression or treatment-induced cytotoxicity. In cancer patients, necrosis within tumors contributes significantly to the pool of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [10].

Active Secretion

Beyond passive release from dead cells, viable cells can actively release DNA through regulated processes.

- Mechanisms: Active secretion primarily occurs via extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes and apoptotic bodies [10]. DNA can be packaged within these vesicles, which protect it from degradation during circulation.

- Fragment Characteristics: The size profile of actively secreted DNA is less well-defined but is likely heterogeneous, as vesicles can encapsulate DNA of varying lengths.

- Biological Significance: Active secretion represents a potential pathway for intercellular communication and may contribute to the spread of oncogenic material in cancer [12]. Its role is an emerging area of focus in liquid biopsy research.

The following diagram illustrates the pathways and resulting cfDNA fragments from these core release mechanisms:

Comparative Analysis: gDNA vs. cfDNA in Sequencing

The distinct origins of cfDNA create fundamental differences in its properties and performance in NGS compared to traditional gDNA. A 2025 study directly compared cfDNA and gDNA from 186 healthy individuals using the same sequencing platform, revealing critical performance distinctions [13].

Sequencing Performance and Coverage

- gDNA Advantages: gDNA sequencing typically provides more uniform coverage across the genome and identifies a greater number of variants due to its intact, high-molecular-weight nature [13].

- cfDNA Challenges: cfDNA exhibits a higher duplication rate and achieves a lower effective sequencing depth at the same raw sequencing output, partly due to its fragmented state. Significant coverage differences are particularly noted in centromeric regions [13].

Despite these technical differences, the allele frequency (AF) spectra, population structure analysis, and genomic association results (e.g., from genome-wide association studies or expression quantitative trait locus analysis) were largely consistent between the two DNA types, supporting the utility of cfDNA for many genetic studies [13].

Fragment Length and Integrity

The following table summarizes key differences in DNA characteristics that impact sequencing:

Table 1: Characteristic Differences Between gDNA and cfDNA

| Characteristic | Genomic DNA (gDNA) | Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Nucleated blood cells (e.g., leukocytes) | Mixed cellular turnover, tumor cells (in cancer) [10] |

| Dominant Release Mechanism | N/A (extracted from cells) | Apoptosis (major), Necrosis, Active Secretion [10] |

| Typical Fragment Length | High molecular weight, intact | Short, fragmented (~167 bp peak) [11] [14] |

| Half-Life | N/A (stable in cells) | Short (16 min to several hours) [12] [14] |

| Key Challenge in NGS | Cellularity requirements, represents a single time point | Low abundance of target DNA (e.g., ctDNA), requires high-sensitivity assays [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Comparison

Robust experimentation is required to characterize cfDNA and validate its performance against gDNA. Below are summarized protocols from key studies and a comparative table of quantitative findings.

Pre-analytical and Extraction Methods

The pre-analytical phase is critical for cfDNA analysis due to its low concentration and short half-life.

- Blood Collection Tubes: Studies compare standard K3EDTA tubes with specialized cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT). While cfDNA levels in K3EDTA tubes increase with processing delay due to white blood cell lysis, they remain stable in BCT tubes for up to 96 hours and even after shipment [15].

- Centrifugation Protocols: A two-step centrifugation is standard. A first, slow-speed step (e.g., 820-1600 × g for 10 minutes) separates plasma from cells, followed by a high-speed step (e.g., 14,000-16,000 × g for 10 minutes) to remove any remaining cellular debris [15]. Studies show that a second centrifugation at 3000 × g yields similar cfDNA results as higher-speed protocols [15].

- Extraction Kits: Performance varies significantly. A 2020 study comparing the Qiagen CNA, Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma, and Zymo Quick ccfDNA kits found that the Qiagen CNA kit consistently yielded the highest quantity of ccfDNA from cancer patient plasma [11]. However, the Maxwell RSC kit often resulted in higher variant allelic frequencies (VAFs) for tumor-specific mutants, which is crucial for detecting low-frequency variants in ctDNA [11].

Sequencing Technologies and Performance

The choice of sequencing platform profoundly impacts the ability to leverage the unique features of cfDNA.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Short-read Illumina platforms are widely used. They provide high accuracy but struggle to capture long fragments from necrosis and require bisulfite conversion for methylation analysis, which damages DNA [14].

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT): A emerging powerful alternative for cfDNA. ONT sequences single molecules in real-time, providing long reads, direct detection of epigenetic modifications (like methylation) without bisulfite conversion, and the ability to integrate multi-omics data (fragmentomics, epigenetics, genetics) in a single assay [12] [14]. Low-coverage ONT sequencing (~0.8X) has been successfully used to determine tissue-of-origin and detect pathogens in critically ill patients, demonstrating its sensitivity [16]. For reliable detection of low-abundance tissues or microbes, a minimum coverage of 5X is recommended [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of gDNA and cfDNA Sequencing Performance

| Performance Metric | gDNA-based NGS | cfDNA-based NGS | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Call Concordance | High (Reference) | Largely consistent | 186 healthy individuals; same platform [13] |

| Effective Sequencing Depth | Higher | Lower (at same raw output) | 186 healthy individuals; higher duplication in cfDNA [13] |

| Coverage Uniformity | More uniform | Less uniform; gaps in centromeres | 186 healthy individuals [13] |

| Input Material Yield | Micrograms | Nanograms (from milliliters of plasma) | Standard extraction protocols [11] |

| Ability to Infer Tissue of Origin | No | Yes (via methylation profiling) | ONT sequencing of ICU patients [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful cfDNA analysis requires careful selection of reagents and tools throughout the workflow. The table below details key solutions for different stages of experimentation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for cfDNA Analysis

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT | Blood collection; stabilizes nucleated cells for delayed plasma processing. | Maintains cfDNA levels for up to 96+ hours at room temp; crucial for multi-site trials [15]. |

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Silica-membrane-based extraction of cfDNA from plasma/serum. | Often provides high yields of total cfDNA; widely used as a benchmark [11] [15]. |

| Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit | Automated, magnetic bead-based extraction of cfDNA. | May provide higher variant allelic frequency for ctDNA, improving mutation detection sensitivity [11]. |

| Oxford Nanopore LSK114 Kit | Library preparation for nanopore sequencing of cfDNA. | Enables PCR-free, multi-omics (genetic, epigenetic, fragmentomic) data from a single run [12] [14]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Molecular barcodes to tag original DNA molecules pre-amplification. | Reduces sequencing artifacts and enables accurate quantification of rare variants [14]. |

The decision to use gDNA or cfDNA in chemogenomic studies is not a matter of simple superiority but of strategic alignment with research goals. gDNA remains the standard for comprehensive variant discovery due to its uniform coverage and high integrity. In contrast, cfDNA, with its origins in apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion, offers a dynamic, non-invasive snapshot of systemic biology, including insights from tissues inaccessible to biopsy.

The emergence of long-read sequencing technologies like ONT, capable of simultaneously querying genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic features from a single cfDNA sample, is poised to unlock deeper layers of biological information [12] [14]. This multi-modal approach is particularly promising for monitoring drug response and understanding resistance mechanisms in oncology and beyond. As standardization in pre-analytical procedures and bioinformatic analysis continues to improve, cfDNA-based NGS is set to become an indispensable tool in the pipeline of modern drug development and personalized medicine.

The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as a cornerstone of liquid biopsy applications in oncology and other fields, offering a non-invasive window into disease dynamics. In chemogenomic studies, which explore the interplay between chemical compounds and the genome, understanding the fundamental physical and chemical properties of cfDNA is paramount for effective research design and data interpretation. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these properties, focusing on fragment size, half-life, and molecular integrity, with particular emphasis on how cfDNA differs from genomic DNA (gDNA) in next-generation sequencing (NGS) applications. The distinct biological origins of these DNA types—with gDNA representing intact cellular DNA and cfDNA deriving primarily from apoptotic or necrotic cells—result in markedly different molecular characteristics that significantly influence experimental outcomes [17] [18].

Fundamental Properties of cfDNA vs. gDNA

Biological Origins and Structural Implications

Table 1: Core Physical Properties of cfDNA vs. gDNA

| Property | Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) | Genomic DNA (gDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Apoptosis, necrosis, active release [17] [18] | Intact cells from tissue or blood |

| Typical Fragment Size | 150-180 bp (mononucleosomal); multiples (di-/tri-nucleosomal) common [17] [18] | High molecular weight (>20,000 bp) |

| Size Range | 100-250 bp (majority); up to 700 bp [18] | Essentially unrestricted |

| Half-Life | 16 minutes - 2.5 hours [19] [20] | Not applicable (within intact cells) |

| Molecular Integrity | Highly fragmented; size patterns reflect tissue of origin [21] [22] | Intact strands |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Features | Often shorter fragments (90-150 bp) than non-mutant cfDNA [21] | Not applicable |

Fragment Size Distribution and Significance

The fragment size distribution of cfDNA is not random but reflects its nucleosomal origin. A prominent peak at approximately 167 bp corresponds to DNA wrapped around a single nucleosome plus a short linker region [17] [22]. This pattern differs significantly from the high molecular weight of gDNA, which remains largely intact during extraction from cellular material.

Notably, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) often exhibits a different fragmentation profile than non-malignant cfDNA. Multiple studies have demonstrated enrichment of tumor-derived fragments in the 90-150 bp range [21]. This size difference can be exploited to enhance tumor detection sensitivity; selecting for shorter fragments (90-150 bp) through in vitro or in silico methods can improve ctDNA detection, with one study reporting more than 2-fold median enrichment in >95% of cases and more than 4-fold enrichment in >10% of cases [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Fragment Size Differences in Health and Disease

| Sample Type | Peak Fragment Size (Mode) | Notable Size Characteristics | Clinical/Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Individuals | 167 bp [17] [22] | Predominantly mononucleosomal peak | Baseline fragmentation pattern |

| Advanced Cancer Patients | Variable | Increased shorter fragments (<150 bp) | Shorter fragments associated with poorer prognosis [23] |

| Pancreatic Cancer (Pre-treatment) | ≤167 bp vs >167 bp | Shorter fragment size associated with worse prognosis | Shorter size: median OS 4.3 mo vs 9.6 mo (longer) [23] |

| ctDNA-Enriched Fractions | 90-150 bp | 2-4 fold enrichment of mutant alleles possible | Enhances detection of tumor-specific alterations [21] |

Experimental Methodologies for Property Analysis

Determining cfDNA Half-Life

Protocol: Exercise-Induced cfDNA Clearance Measurement [19]

- Objective: Determine the half-life of cfDNA fragments (100-250 bp) following exercise-induced elevation.

- Participants: Healthy adult men (n=5, age 40±4.1 years).

- Exercise Regimen: 30-minute treadmill exercise at controlled speed of 8 km/h.

- Sample Collection:

- Blood collected at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 minutes post-exercise.

- Use of PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tubes to stabilize cfDNA and prevent nuclease-mediated degradation.

- cfDNA Isolation:

- Double centrifugation: 15 min at 1,900×g followed by 15 min at 1,900×g.

- Extraction with QuickGene cfDNA isolation kit on QuickGene-Mini8L system.

- Quantification & Size Analysis:

- Electrophoresis-based quantification using 4150 TapeStation system.

- Specific focus on 100-250 bp fragments.

- Half-Life Calculation:

- Measured rate of concentration decline post-exercise.

- Reported Result: cfDNA half-life of 24.2 minutes [19].

Analyzing Fragment Size Distribution

Protocol: Multiplex ddPCR for cfDNA Fragment Sizing [22]

- Principle: Simultaneous amplification of three size ranges (73-165 bp; 166-253 bp; >253 bp) from olfactory receptor (OR) genes, with STAT6 as a diploid reference.

- Assay Design:

- Targets multiple OR genes with high sequence conservation.

- Enables absolute quantification via STAT6 reference.

- Procedure:

- Partition cfDNA sample into ~20,000 nanodroplets.

- Amplify with size-specific probes.

- Count positive droplets for each target.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate ratio of short to medium fragments (73-165 bp / 166-253 bp).

- Healthy controls typically show ratio of 1.0-1.20.

- Elevated ratios indicate higher fragmentation, potentially suggesting tumor origin.

- Validation: Strong correlation with capillary electrophoresis (R²=0.725) and high-throughput sequencing (R²=0.766) [22].

Fragment Size Selection for ctDNA Enrichment

Protocol: Enhancing ctDNA Detection by Fragment Size Selection [21]

- Background: ctDNA fragments are enriched in 90-150 bp range compared to non-mutant cfDNA.

- Method 1: In Vitro Size Selection

- Use microfluidic devices to physically separate shorter DNA fragments.

- Process plasma samples to enrich 90-150 bp fraction.

- Continue with standard NGS library preparation.

- Method 2: In Silico Size Selection

- Perform standard shallow whole-genome sequencing (0.4× coverage).

- Bioinformatically filter aligned reads to retain only those with 90-150 bp insert sizes.

- Performance Metrics:

- t-MAD score: Quantifies copy number alteration detection power.

- Enrichment factor: Ratio of tumor DNA signal after/before size selection.

- Results: >2-fold median enrichment in >95% of cases; >4-fold in >10% of cases [21].

Impact on Chemogenomic Study Outcomes

Pre-analytical Considerations

The significant differences in physical properties between cfDNA and gDNA necessitate distinct handling protocols throughout the research workflow.

Table 3: Pre-analytical Requirements for cfDNA vs. gDNA in NGS Studies

| Parameter | cfDNA-Based NGS | gDNA-Based NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Plasma from blood collected in specialized tubes (EDTA, Streck, PAXgene) [4] [19] | Tissue biopsies or blood for cellular DNA |

| Processing Time | Critical: within 4h (EDTA) or 96h (Streck) [4] | Less critical; standard tissue preservation |

| Extraction Method | Optimized for low concentrations/small fragments (QIAamp CNA kit) [24] [23] | Standard phenol-chloroform or column-based |

| Quality Assessment | Fragment size analysis (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) [22] [23]; ddPCR for quantification | Spectrophotometry (A260/280); gel electrophoresis |

| Input Requirements | Often limited (nanograms); may require whole genome amplification | Typically sufficient (micrograms) |

Analytical Performance in NGS Applications

The molecular integrity and fragment size of cfDNA directly impact sequencing library construction and data quality:

- Library Complexity: Fragmented nature of cfDNA reduces library complexity compared to gDNA, potentially affecting mutation detection sensitivity.

- Amplification Bias: Smaller fragment sizes may amplify more efficiently, potentially skewing variant allele frequency measurements.

- Error Rates: cytosine deamination damage in short cfDNA fragments can increase C>T/G>A errors, requiring specialized bioinformatic correction.

- Coverage Uniformity: Nucleosomal protection patterns can create coverage biases across the genome, unlike the more uniform coverage from fragmented gDNA.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for cfDNA Analysis

| Category | Product/Technology | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection | PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tubes [19] | Stabilize cfDNA, inhibit nucleases | Critical for half-life studies; prevents in vitro degradation |

| Blood Collection | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes [4] | Stabilize blood cells, preserve cfDNA profile | Enables extended processing windows (up to 96h) |

| Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [24] [23] | Optimized recovery of short cfDNA fragments | Higher yields for low-concentration samples |

| Size Analysis | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer/TapeStation [22] [23] | Fragment size distribution and quantification | Essential quality control step |

| Quantification | Multiplex ddPCR Assay [22] | Absolute quantification and size distribution | More accurate than fluorometry; detects gDNA contamination |

| Size Selection | Microfluidic Systems [21] | Physical separation of fragment sizes | Enriches ctDNA by selecting 90-150 bp fragments |

The physical and chemical properties of cfDNA—particularly its characteristic fragment size around 167 bp, short half-life of minutes to hours, and distinct molecular integrity patterns—fundamentally differentiate it from gDNA in chemogenomic research applications. These differences necessitate specialized methodologies throughout the experimental workflow, from sample collection through data analysis. Researchers can leverage these property differences to enhance experimental outcomes, such as using size selection to enrich for tumor-derived fragments or employing appropriate stabilization methods to account for rapid clearance. Understanding these core properties enables more informed experimental design, improves data interpretation, and ultimately enhances the reliability of cfDNA-based liquid biopsy approaches in chemogenomic studies and drug development programs.

In the era of precision oncology, molecular profiling of tumors has become indispensable for guiding therapeutic decisions. Traditionally, this profiling has relied on genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from tumor tissue obtained via invasive biopsies. However, these procedures carry inherent risks, are not always feasible, and often fail to capture the full spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the tumor. The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA)—short fragments of DNA circulating in the bloodstream—presents a transformative, minimally invasive alternative. A critical subset of cfDNA is circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), which is shed by tumor cells and carries tumor-specific genetic alterations. The clinical significance of ctDNA analysis lies in its ability to provide a real-time, comprehensive snapshot of the tumor's genomic landscape, enabling applications in treatment selection, response monitoring, minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, and tracking the emergence of resistance. This guide objectively compares the performance of ctDNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) to traditional gDNA-based tissue testing, framing the discussion within chemogenomic research for drug development professionals and scientists.

Fundamental Concepts: gDNA vs. cfDNA/ctDNA

To appreciate the technical and clinical comparisons, it is essential to understand the fundamental differences between the analyte sources.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) from Tissue Biopsy: Derived from intact tumor cells obtained through a tissue biopsy. This source provides high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA but represents a single snapshot of a specific lesion at a single point in time. It is susceptible to sampling bias, particularly in heterogeneous tumors, and serial sampling to monitor evolution is challenging [25] [26].

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): cfDNA is released into the bloodstream primarily through cellular apoptosis and necrosis; in cancer patients, the fraction derived from tumor cells is termed ctDNA. ctDNA is highly fragmented (~167 bp), has a short half-life (from 16 minutes to several hours), and reflects the molecular characteristics of all tumor subclones across different disease sites, thereby capturing tumor heterogeneity. Its low concentration in early-stage disease (often <0.1% of total cfDNA) presents a significant analytical challenge [25] [26] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the origin and analysis pathways of gDNA and ctDNA.

Performance Comparison: Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

The analytical performance of ctDNA-NGS assays is a critical focus of research, as it must overcome the challenge of detecting very low VAF mutations amidst a background of wild-type cfDNA. Direct comparative studies and analytical validations provide key performance metrics.

Direct Assay Comparison

A landmark study directly compared five major large-panel (≥500 genes) ctDNA NGS assays using validated reference samples. The results highlight that performance is highly dependent on input DNA quantity and mutation allele frequency [28].

Table 1: Performance of Five ctDNA-NGS Assays on Reference Samples [28]

| Assay | Panel Size | Sensitivity at 0.5% VAF | Sensitivity at 0.1% VAF | Key Technical Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay A | 500 genes | ≥90% | Decreased & Variable | Depth of coverage, background noise |

| Assay B | 600 genes | ≥90% | Decreased & Variable | Depth of coverage, background noise |

| Assay C | 500 genes | ≥90% | Decreased & Variable | Depth of coverage, background noise |

| Assay D | ~500 genes | ≥90% | Decreased & Variable | Depth of coverage, background noise |

| Assay E | ~100 genes | ≥90% | Decreased & Variable | Depth of coverage, background noise |

The study concluded that while all assays demonstrated high sensitivity (≥90%) and reproducibility for mutations at 0.5% or 1.0% VAF with optimal DNA input (30-50 ng), performance decreased dramatically at a 0.1% VAF and/or with lower DNA input (10 ng). The depth of coverage and background noise were identified as critical factors influencing performance [28].

gDNA (Tissue) vs. ctDNA (Plasma) Concordance

Multiple clinical studies have investigated the concordance of mutation profiles between tissue-based gDNA-NGS and plasma-based ctDNA-NGS.

A study of 190 NSCLC patients undergoing concurrent tissue and plasma testing with a 168-gene panel found a high overall concordance of 78.9%. Crucially, in the subset of patients with detectable ctDNA, the concordance rate rose to 91.2%, with plasma-NGS sensitivity reaching 93.5% for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions/deletions (indels). However, plasma-NGS was significantly less capable of detecting copy number variations (CNVs) and gene fusions compared to tissue-NGS [29].

Another study in the Netherlands involving 59 advanced NSCLC patients reported a 71.2% concordance between standard-of-care tissue genotyping and ctDNA-NGS. In a minority of cases (3.4%), ctDNA-NGS missed an actionable driver alteration, underscoring that tissue testing remains the gold standard when available [30].

Table 2: Tissue vs. Plasma NGS Concordance in Advanced NSCLC [30] [29]

| Study | Cohort Size | Overall Concordance | Concordance When ctDNA Detectable | Plasma Sensitivity for SNV/Indel | Plasma Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. (2023) | 190 | 78.9% | 91.2% | 93.5% | CNVs, Fusions |

| LICA Study (2025) | 59 | 71.2% | N/R | N/R | May miss low-VAF actionable drivers |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Robust and sensitive methodologies are paramount for reliable ctDNA analysis. The following section details the key experimental protocols cited in the performance comparisons.

- Reference Samples: Two sets of reference materials (Seracare Life Sciences) were used. Set one contained 40 mutations relevant to solid tumors; set two contained 23 mutations related to myeloid malignancy. Each set included samples with variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of 1%, 0.5%, 0.125%, and a negative control.

- DNA Input: Vendors were supplied with samples at different DNA concentrations (e.g., 10 ng and 30/50 ng) to evaluate input impact.

- Testing Procedure: Each vendor processed the samples according to their proprietary protocols for library preparation, target enrichment (hybrid capture for most), and sequencing.

- Data Analysis: A minimum of 4 variant-supporting reads was required for a positive call. Sensitivity was defined as the number of reference mutations detected divided by the total number of expected mutations.

- Assay: TruSight Oncology 500 ctDNA assay.

- Input: The primary validation used 30 ng of cfDNA.

- Performance Metrics: The assay demonstrated high sensitivity and low variability for SNVs, indels, and fusions down to 0.5% VAF. Sensitivity was considerably lower, and variability increased, at reduced input amounts (20, 15, and 5 ng) and VAFs below 0.5%.

- Sample Collection: Blood collected in Roche Cell-Free DNA collection tubes, processed within five days.

- ctDNA Isolation: Using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit.

- Library Prep & Target Enrichment: Used an in-house developed hybrid-capture probe set (117 kb, covering 45 genes) with Twist Library Preparation Kit. Incorporated Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for error correction.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq6000. Bioinformatic pipelines (GATK Mutect2) were used with stringent filters, including a requirement that the VAF be >20 times higher than the average VAF in healthy control samples to reduce background noise.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful ctDNA analysis requires careful selection of reagents and materials throughout the workflow. The table below details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA-NGS

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes blood cells to prevent lysis and genomic DNA contamination during transport and storage. | Roche Cell-Free DNA BCTs [30], Streck BCTs [31]. Roche tubes demonstrated superior prevention of WBC lysis over 14 days [31]. |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify short-fragment cfDNA from plasma. | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [30]. Optimized for low-concentration, fragmented DNA. |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare NGS libraries from low-input, fragmented cfDNA. | Twist Library Preparation Kit (Twist Biosciences) [30]. Often used with UMIs for error correction. |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Hybrid-capture or amplicon-based panels to enrich for cancer-related genes. | Custom probe sets (e.g., Twist Biosciences) [30]. Panel sizes range from ~100 to >500 genes [28] [32]. |

| UMI Adapters | Molecular barcodes ligated to DNA fragments pre-amplification to distinguish true mutations from PCR/sequencing errors. | xGEN dual-index UMI adapters (Integrated DNA Technologies) [30]. Critical for achieving high specificity in low-VAF detection. |

Clinical Applications and Limitations

The primary clinical value of ctDNA analysis lies in its dynamic monitoring capabilities, which complement the more comprehensive but static profile from a tissue biopsy.

Key Clinical Applications

- Treatment Monitoring and Response Assessment: ctDNA levels can serve as a highly sensitive metric for tumor burden. A decrease or clearance of ctDNA (molecular response) often precedes radiographic response, while a rise can indicate emerging resistance, sometimes months before clinical progression [25].

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection: Following curative-intent therapy, the presence of ctDNA is a highly specific indicator of residual disease and a powerful predictor of future relapse, offering a significant advantage over imaging, which cannot detect microscopic disease [25] [26].

- Identifying Resistance Mechanisms: Serial ctDNA analysis can uncover the molecular drivers of treatment resistance (e.g., EGFR T790M mutation after first-line EGFR inhibitor therapy), allowing for timely intervention and therapy modification [25].

- Comprehensive Genotyping when Tissue is Unavailable: For patients where tissue biopsy is infeasible or insufficient, ctDNA analysis can identify actionable genomic alterations to guide therapy [30] [29].

Current Limitations and Challenges

- Lower Sensitivity for Certain Alterations: As noted in performance comparisons, ctDNA-NGS has reduced sensitivity for detecting copy number variations (CNVs) and gene fusions compared to tissue-NGS [29].

- False Negatives and Low Shedding: Not all tumors shed sufficient DNA into the bloodstream, leading to false-negative results, particularly in early-stage, low-burden, or certain tumor types [25] [29].

- Background Noise and Clonal Hematopoiesis: Sequencing artifacts and mutations originating from clonal hematopoiesis (CH) of indeterminate potential can be misclassified as tumor-derived, leading to false positives. Specialized bioinformatic filters and sequencing of matched white blood cells can help mitigate this [30].

- Lack of Standardization: Differences in pre-analytical variables (collection tubes, processing time), analytical methods (panels, UMIs), and bioinformatic pipelines pose challenges for cross-assay comparisons and universal clinical adoption [25] [30].

The integration of cfDNA and ctDNA analysis into the oncology landscape represents a paradigm shift from static, invasive biopsies to dynamic, minimally invasive disease monitoring. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between gDNA-based and cfDNA-based NGS is not a binary one but rather a strategic decision based on the clinical or research question.

gDNA from tissue biopsies remains the gold standard for initial diagnosis and provides the most comprehensive genomic profile, including reliable detection of CNVs and fusions. ctDNA from liquid biopsies excels in longitudinal monitoring, assessing tumor heterogeneity, detecting MRD, and profiling tumors when tissue is unavailable.

Future directions in the field will focus on overcoming current limitations. This includes standardizing pre-analytical and analytical protocols, improving the sensitivity for all variant types through techniques like duplex sequencing [25], and exploring the potential of long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) to simultaneously capture genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic information from a single cfDNA molecule [27]. For chemogenomic studies, the ability to non-invasively track the evolution of tumor genomes under therapeutic pressure will be invaluable for understanding drug resistance and developing next-generation targeted therapies.

gDNA as a Static Snapshot vs. cfDNA as a Dynamic Monitor of Disease

In chemogenomic studies and cancer drug development, the choice of genomic material for analysis is paramount. Genomic DNA (gDNA) from tissue biopsies and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from liquid biopsies offer fundamentally different perspectives on the disease. gDNA provides a static, historical snapshot of a tumor's genotype from a single site at a single point in time. In contrast, cfDNA analysis offers a dynamic, real-time monitor that captures the evolving genomic landscape of the entire disease burden. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and clinical applications of these complementary approaches within the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS), providing researchers with the data necessary to inform their study designs.

Performance Comparison: Analytical Characteristics

The intrinsic biological properties of gDNA and cfDNA directly translate to distinct performance characteristics in analytical workflows. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of gDNA and cfDNA in NGS Analysis

| Characteristic | gDNA (Tissue Biopsy) | cfDNA (Liquid Biopsy) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) or fresh frozen tissue [33] | Plasma derived from peripheral blood [33] [34] |

| Representativeness | Single-site, subject to spatial heterogeneity [33] | Cross-sectional, captures spatial (multi-site) heterogeneity [35] |

| Temporal Resolution | Single time point; repeat sampling difficult [33] | Enables repeated sampling for longitudinal monitoring [35] |

| Turnaround Time (Typical) | ~60 days (for re-biopsy) [33] | ~29 days [33] |

| DNA Fragmentation | Highly fragmented (especially FFPE), variable size [33] | Regularly fragmented (~167 bp peak), nucleosome-derived [2] [34] |

| Limit of Detection (VAF) | ~5% (for standard NGS panels) [36] | 0.01% - 0.08% (with high-depth NGS/ddPCR) [36] [34] |

| Analytical Sensitivity | High for high tumor purity samples | Dependent on ctDNA fraction (often 0.01%-10%) [35] [34] |

| Primary Clinical Use | Gold standard for diagnosis and initial genomic profiling [33] | Identification of actionable mutations, therapy monitoring, MRD detection [35] |

Beyond these core characteristics, the difference in dynamic monitoring is profound. One study noted that archival tissue "might not represent the current malignancy due to clonal evolution," a limitation directly addressed by the serial assessment capability of cfDNA [33]. Furthermore, while tissue biopsies are unusable in 20-30% of non-small cell lung cancer patients, cfDNA profiling provides a feasible alternative [33].

Experimental Data: Supporting Evidence from Clinical Studies

Empirical data from clinical studies underscores the practical performance differences summarized above.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Data from Analytical Studies

| Study Context | gDNA Performance | cfDNA Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal Cancer (ddPCR vs NGS) [36] | N/A | ddPCR: 58.5% (24/41) detection in baseline plasma.NGS Panel: 36.6% (15/41) detection (p=0.00075). | ddPCR showed a significantly higher detection rate for ctDNA in localized rectal cancer compared to an NGS panel. |

| Feasibility in Phase I Setting [33] | Turnaround: Median 60 days (n=6). | Turnaround: Median 29 days (n=24). | Selected cancer-associated alterations were identified in 70% (31/44) of patients via cfDNA, primarily by WES. |

| Cancer Phenotyping (UW Cohort) [2] | N/A | Normalized depth across all exons achieved an average AUROC of 0.943 for predicting cancer types/subtypes. | Fragmentomics patterns from targeted cfDNA panels enable accurate cancer phenotyping. |

| Healthy Individual Screening [34] | N/A | Pathogenic cancer mutations detected in donors up to 10 years before clinical diagnosis. | Demonstrated the technical feasibility of cfDNA analysis for early detection, with a LOD of 0.08% VAF. |

A critical finding from a 2025 study is that fragmentomics analysis, which infers epigenetic and transcriptional data from cfDNA fragmentation patterns, can be successfully applied to the targeted sequencing panels already in clinical use, without requiring whole-genome sequencing [2]. This significantly broadens the potential applications of existing clinical datasets.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for gDNA and cfDNA NGS

gDNA Workflow from Tissue Biopsies

The standard protocol for gDNA-based NGS begins with tissue acquisition.

- Tissue Collection and DNA Extraction: A tumor specimen is obtained via surgical resection or core needle biopsy. For archival material, DNA is extracted from 4-5 sections of 10 µm thick FFPE tissue after deparaffinization using a column-based recovery kit [34]. DNA quantity is assessed using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit).

- NGS Library Preparation: Depending on the assay, 5-40 ng of input DNA is used. For targeted panels (e.g., Oncomine Solid Tumor or Focus Assay), libraries are prepared through a series of amplification steps to attach sequencing adapters and sample barcodes. The resulting libraries are purified using bead-based cleanup [34].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Libraries are quantified by qPCR, diluted to a standard concentration, and sequenced. Bioinformatic analysis pipelines are used for variant calling, with a typical detection threshold around 5% Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) for standard panels [36].

cfDNA Workflow from Liquid Biopsies

The cfDNA workflow emphasizes sensitivity and handling of low-input material.

- Blood Collection and Plasma Separation: Blood is drawn into specialized collection tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or K2EDTA tubes). The plasma fraction is separated from cellular components by two consecutive centrifugation steps (e.g., 1600 x g for 30 minutes) [34]. Plasma is aliquoted and stored at -80°C.

- cfDNA Extraction and QC: cfDNA is extracted from plasma volumes (0.4-5.5 mL) using a magnetic bead-based nucleic acid isolation kit. The eluted cfDNA is quantified by fluorometry. Quality control is critical and is performed using a High Sensitivity microfluidic system to confirm a dominant fragment size peak between 140-200 bp [34].

- Ultra-Sensitive NGS Library Preparation: For plasma cfDNA, NGS libraries are prepared from a small input (e.g., 2.5-105.5 ng) using molecular barcoding techniques. A two-cycle multiplex touch-down PCR first amplifies target regions and introduces unique molecular identifiers. After a bead-based cleanup, a second PCR (e.g., 18 cycles) adds sequencing adapters and sample barcodes [34]. This method allows for a limit of detection as low as 0.08% VAF [34].

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Libraries are quantified, pooled, and sequenced at high depth (often >50,000x coverage). Bioinformatics pipelines use the molecular barcodes to error-correct and accurately call variants at very low frequencies.

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural differences and logical relationship between the two workflows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of gDNA and cfDNA NGS requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for gDNA and cfDNA NGS

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Blood collection tubes that stabilize nucleated blood cells to prevent background gDNA release, preserving the native cfDNA profile. | Preserving cfDNA fragmentomics patterns during blood sample transport and storage [36] [34]. |

| Magnetic Bead-based cfDNA Kits | (e.g., MagMax Cell-Free Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit). Optimized for high-efficiency isolation of short, low-concentration cfDNA fragments from plasma. | Extracting high-quality cfDNA for ultra-sensitive downstream NGS or ddPCR applications [34]. |

| Molecular Barcoding Kits | (e.g., Oncomine Pan-Cancer Cell-Free Assay). NGS library prep kits that incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to tag original DNA molecules for error correction. | Achieving a low limit of detection (0.01%-0.08% VAF) by distinguishing true low-frequency variants from sequencing errors [34]. |

| Targeted NGS Panels | (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2). Focused gene panels enabling deep sequencing for variant discovery in specific genomic regions. | Profiling somatic alterations in tumor gDNA or cfDNA for hotspot mutations in 50+ genes [36]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | An absolute quantification method that partitions samples into thousands of droplets for endpoint PCR, detecting rare mutations with high sensitivity. | Ultra-sensitive validation and tracking of specific known mutations in cfDNA [36] [35]. |

| Agilent High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape | A microfluidic electrophoresis system used to quality control cfDNA extracts, confirming the characteristic ~170 bp fragmentation pattern. | QC step to ensure cfDNA sample integrity before proceeding to costly NGS library preparation [34]. |

The choice between gDNA and cfDNA is not a matter of selecting a superior technology, but of applying the right tool for the specific research question. gDNA from tissue biopsies remains the unparalleled static snapshot, providing the foundational histopathological and molecular diagnosis. However, for a dynamic monitor of disease evolution, treatment response, and resistance mechanisms, cfDNA is transformative. Its capacity for non-invasive, repeated sampling captures the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of cancer, making it an indispensable tool in modern chemogenomic research and the development of personalized cancer therapies. The future lies in the integrated interpretation of both the detailed, static landscape from gDNA and the evolving, systemic view from cfDNA.

From Bench to Biomarker: Practical NGS Workflows and Chemogenomic Applications

In the realm of chemogenomic studies and precision medicine, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for elucidating disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. The choice of source material—genomic DNA (gDNA) from whole blood or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma—fundamentally shapes experimental design, analytical capabilities, and clinical applicability. Whole blood provides a stable source of germline genetic information through gDNA, while plasma offers a dynamic, minimally invasive window into pathologic states through cfDNA, particularly circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in oncology [12]. This guide objectively compares these two approaches by synthesizing current experimental data and methodologies, providing researchers with a evidence-based framework for selecting the appropriate sample type for their specific NGS applications in drug development and biomarker discovery.

Fundamental Characteristics and Experimental Workflows

The divergence between gDNA and cfDNA analysis begins at the biological level and extends throughout the entire NGS workflow. gDNA represents intact genomic material extracted from white blood cells, providing a comprehensive blueprint of an individual's hereditary genetic makeup. In contrast, cfDNA consists of short, fragmented DNA molecules (typically ~167 bp) released into the bloodstream primarily through cellular apoptosis and necrosis, with a minor contribution from active secretion [12]. In cancer patients, a subset of cfDNA originates from tumors (ctDNA), carrying genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic information about the malignancy.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of gDNA and cfDNA

| Characteristic | gDNA from Whole Blood | cfDNA from Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Leukocytes | Mixed cellular sources (apoptosis/necrosis) |

| Typical Fragment Size | High molecular weight, intact | ~167 bp dominant peak |

| Half-life | Stable long-term with proper storage | 16 minutes to several hours [12] |

| Representative Information | Germline genetics | Somatic alterations, tumor heterogeneity |

| Key Preparative Step | Cell lysis and DNA precipitation | Centrifugation for plasma separation |

The experimental workflows for processing these sample types differ significantly, particularly in the pre-analytical phase. Proper sample handling is critical for both, but requires distinct optimization strategies.

Workflow Diagram: gDNA vs cfDNA NGS Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences in processing whole blood for gDNA analysis versus plasma for cfDNA analysis:

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Whole Blood Processing for gDNA Extraction

Effective gDNA extraction from whole blood requires careful sample stabilization and processing. Blood samples should be collected in EDTA or specialized DNA stabilization tubes and processed within 24-48 hours when stored at 4°C. For long-term storage, freezing at -80°C is recommended [37]. The initial centrifugation step typically occurs at 1,900×g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from the cellular fraction [38]. The buffy coat layer containing leukocytes is then collected for DNA extraction.

Mechanical homogenization methods, such as bead-based systems (e.g., Bead Ruptor Elite), can enhance DNA recovery from challenging starting materials while minimizing shearing [37]. Following extraction, gDNA quality control should assess concentration (via fluorometry), purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8), and integrity (via gel electrophoresis or automated systems like Agilent TapeStation) [39] [40]. Intact gDNA should show a high molecular weight band without smearing.

Plasma Processing for cfDNA Isolation

cfDNA analysis demands rigorous pre-analytical conditions to prevent contamination by cellular genomic DNA. Blood samples require double centrifugation: first at 1,900×g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from blood cells, followed by a second centrifugation at 16,000×g for 10 minutes to remove remaining cellular debris [38]. Plasma should be frozen at -80°C if not processed immediately, with avoidance of repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Specialized cfDNA extraction kits employing silica-membrane technology are recommended to recover short fragments efficiently. For library preparation, specific optimizations are needed for short cfDNA fragments, including adjusted bead-to-sample ratios (typically increased to 1.8×) during clean-up steps to enhance recovery of molecules <200 bp [12]. Quality assessment should include fragment size analysis (peak ~167 bp) and quantification using sensitive fluorescence-based methods compatible with low DNA concentrations.

Diagnostic Performance and Analytical Capabilities

The functional differences between gDNA and cfDNA analysis become particularly evident when examining their diagnostic performance across clinical applications. Multiple studies have systematically compared the sensitivity, specificity, and limitations of each approach in various disease contexts.

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance Comparison in Clinical Studies

| Application | Sample Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Febrile Illness in Immunocompromised Patients | Plasma cfDNA (mNGS) | 84.4% (positivity rate) | Lower specificity | Higher false positives; multiple pathogens detected in 68.5% of positive samples | [38] |

| Febrile Illness in Immunocompromised Patients | Blood Cell gDNA (mNGS) | 46.9% (positivity rate) | Higher specificity | Causative pathogens identified in 76.7% of mNGS-positive cases | [38] |

| Periprosthetic Joint Infection | mNGS (various sources) | 89% | 92% | Superior sensitivity for infection detection | [41] |

| Periprosthetic Joint Infection | Targeted NGS (various sources) | 84% | 97% | Higher specificity for confirming infection | [41] |

| Advanced NSCLC (EGFR mutations) | Tissue gDNA | 93% | 97% | High accuracy for point mutations | [42] |

| Advanced NSCLC (EGFR mutations) | Liquid biopsy cfDNA | 80% | 99% | Effective for point mutations but limited sensitivity for fusions | [42] |

The data reveals a consistent pattern: plasma cfDNA analyses generally offer higher sensitivity but may sacrifice specificity, while cellular gDNA approaches provide more specific but less sensitive detection. This trade-off has significant implications for clinical and research applications.

Multiomics Analytical Potential

Beyond simple pathogen detection or mutation identification, both sample types offer distinct advantages for multiomics approaches:

gDNA from Whole Blood provides comprehensive germline information including:

- Constitutional genetic variants and polymorphisms

- Structural variants and copy number variations

- Mitochondrial DNA sequences

- Stable genetic markers for pharmacogenomics

cfDNA from Plasma enables multidimensional analysis through:

- Fragmentomics: Non-random fragmentation patterns can infer gene expression and chromatin organization [2]. Tumor-derived cfDNA shows different fragmentation profiles than healthy cfDNA.

- Methylation Analysis: Cancer-specific methylation patterns in ctDNA serve as biomarkers for early detection and tumor typing [12]. Nanopore sequencing allows direct methylation detection without bisulfite conversion.

- Copy Number Variations (CNVs): Somatic CNVs in ctDNA can monitor tumor evolution and therapy response [12].

- Combined Approaches: Integrating fragmentomics with mutation detection improves cancer phenotyping accuracy in targeted panels [2].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Pathogen Detection in Febrile Illness

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 study comparing plasma cfDNA and blood cell gDNA for pathogen detection in immunocompromised children [38].

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect 2-5 mL whole blood in EDTA tubes within 6 hours of fever onset

- Centrifuge at 1,900×g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Carefully transfer supernatant (plasma) to a new tube without disturbing the buffy coat

- Aliquot plasma for cfDNA extraction

- Transfer the buffy coat layer to a separate tube for cellular gDNA extraction

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Plasma cfDNA: Extract using a commercial cfDNA kit with a minimum input of 1-3 mL plasma

- Blood Cell gDNA: Perform host depletion using differential lysis before DNA extraction [38]

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Construct libraries using compatible kits for cfDNA or gDNA

- Sequence on Illumina platforms (≥20 million reads per sample)

- For blood cell gDNA, include steps to enrich for microbial DNA

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control of raw reads (FastQC)

- Remove human sequences by alignment to hg19

- Classify non-human reads using Kraken2 against a curated pathogen database

- Apply threshold filters: RPTM ≥3 for viruses, ≥8 for bacteria/fungi [38]

Protocol: Fragmentomics Analysis from Targeted cfDNA Sequencing

This protocol enables extraction of fragmentomic features from targeted cfDNA sequencing data, adapted from a 2025 Nature Communications study [2].

Wet Lab Procedures:

- Extract cfDNA from 3-10 mL plasma using optimized bead-based cleanups (1.8× ratio)

- Prepare libraries using targeted cancer gene panels (e.g., 55-822 gene panels)

- Sequence to high depth (>3000×)

Computational Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data through standard alignment pipelines

- Calculate multiple fragmentomics metrics:

- Normalized fragment depth across all exons

- Shannon entropy of fragment size distribution

- End motif diversity score (MDS)

- Proportion of small fragments (<150 bp)

- Fragment size distribution binnings

- Build predictive models using GLMnet elastic net with 10-fold cross-validation

- Validate performance via AUROC for cancer type classification

Key Finding: Normalized fragment read depth across all exons provides the best overall performance for cancer phenotyping (AUROC: 0.943-0.964) compared to first-exon only metrics [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of gDNA and cfDNA NGS requires specialized reagents and tools optimized for each sample type.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Category | Product/Technology | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Bead Ruptor Elite | Mechanical homogenization for tough samples | Precise control of speed, cycle duration, temperature; minimizes DNA shearing [37] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Silica-membrane cfDNA kits | Optimized cfDNA isolation | Enhanced recovery of short fragments; removal of contaminants |

| Library Preparation | ONT SQK-LSK114 | Nanopore cfDNA sequencing | Direct methylation detection; PCR-free option; long-read capabilities [12] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep | gDNA library preparation | Efficient fragmentation and adapter ligation; high complexity libraries |

| Quality Control | Agilent TapeStation | Nucleic acid integrity | RNA Integrity Number (RIN); DNA integrity assessment [39] |

| Quality Control | Fragment Analyzer | cfDNA size distribution | Precise sizing of short fragments; quantification of tumor-derived fragments |

| Target Enrichment | Commercial targeted panels (Guardant360, FoundationOne) | ctDNA mutation detection | Clinically validated; optimized for variant calling in background of wild-type DNA [2] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | FastQC | Raw read quality control | Per base sequence quality; adapter content; GC distribution [39] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Kraken2 | Taxonomic classification | Rapid metagenomic analysis; pathogen identification [38] |

The choice between whole blood gDNA and plasma cfDNA for NGS applications represents a fundamental strategic decision in experimental design for chemogenomic studies. Whole blood gDNA provides stable, comprehensive germline genetic information ideal for constitutional variant analysis, pharmacogenomics, and establishing genetic baselines. Its higher specificity in pathogen detection makes it valuable for confirmatory diagnostics. Conversely, plasma cfDNA offers a dynamic, minimally invasive window into current pathological states, particularly in oncology, with superior sensitivity for detecting active infections and tumor-derived alterations. The emerging field of cfDNA fragmentomics further expands its utility beyond mutation detection to include epigenetic and transcriptomic inference.

Researchers should select whole blood gDNA when analyzing hereditary variants, requiring high specificity, or working with stable genetic markers. Plasma cfDNA is preferable for monitoring dynamic processes, detecting minimal residual disease, capturing tumor heterogeneity, or when minimally invasive serial sampling is needed. Future directions point toward integrated approaches that leverage both sample types to provide complementary information, as well as technological advances in long-read sequencing and multiomics analysis that will further enhance the informational yield from each source.

In chemogenomic studies, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for understanding drug mechanisms and cellular responses. The choice between genomic DNA (gDNA) and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as a sequencing source presents researchers with distinct technical challenges, particularly during library preparation. While gDNA from white blood cells has traditionally been the cornerstone of genomic investigations, cfDNA from bodily fluids is increasingly recognized as a valuable biomarker that reflects physiological and pathological states [43]. The nuanced handling of GC-bias and fragment length distribution during library preparation represents a pivotal factor determining the success of downstream applications, from variant calling to nucleosome profiling.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of library preparation strategies for managing these technical variables, with a specific focus on their impact within chemogenomic research. We present structured experimental data and methodological frameworks to empower researchers in selecting and optimizing protocols that ensure data integrity and maximize the unique informational content of their cfDNA samples.

A direct comparison of gDNA and cfDNA from the same individuals reveals both consistencies and critical technical divergences that must be addressed during library preparation. At equivalent effective sequencing depths (~37x), both DNA types demonstrate highly comparable quality metrics, allele frequency spectra, population structure, and genomic association results [43]. This foundational consistency underscores the reliability of cfDNA for genetic analyses.

However, key technical differences directly impact library preparation requirements:

- Fragmentation Origin: gDNA requires in vitro fragmentation (mechanical or enzymatic) during library prep, whereas cfDNA is naturally pre-fragmented in vivo (~167 bp) [44].

- Input Material: cfDNA samples typically yield minute quantities (5-10 ng/mL of plasma) [44], demanding kits compatible with low-input protocols.

- Duplication Rates: cfDNA demonstrates higher duplication rates, leading to lower effective sequencing depth after duplicate removal [43].

- Coverage Bias: Significant depth differences between cfDNA and gDNA are predominantly observed in centromeric regions [43].

These inherent differences necessitate tailored approaches for cfDNA library construction, particularly concerning bias mitigation.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of gDNA vs. cfDNA in Sequencing

| Characteristic | gDNA (White Blood Cells) | cfDNA (Blood Plasma) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical State | Long, complete double-helix strands [43] | Short, fragmented DNA (~167 bp) [44] |

| Fragmentation | In vitro (sonication/enzymatic) during prep | In vivo (apoptosis, necrosis) prior to extraction |

| Typical Input | Micrograms (e.g., 100-1000 ng) [45] | Nanograms (e.g., 1-100 ng) [45] |

| Variant Detection | Identifies ~100K more SNPs than cfDNA [43] | High genotype concordance with gDNA [43] |

| Primary Challenge | Uniform coverage and fragmentation | GC-bias correction; utilizing fragment length signatures |

The GC-Bias Challenge in cfDNA Library Preparation

GC bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and GC content, which can dominate the genuine biological signal in analyses measuring fragment abundance [46]. This bias manifests as a unimodal curve where both GC-rich and AT-rich fragments are underrepresented in sequencing results [46]. In the context of cfDNA, this bias is particularly problematic for two reasons: it complicates copy number estimation, and it can obscure the subtle fragmentation patterns that are informative for cancer detection and nucleosome profiling [47] [48].

The underlying mechanisms of GC bias are rooted in the library preparation process itself. PCR amplification is identified as a major contributor, as fragments with extreme GC content amplify less efficiently [46] [49]. Furthermore, the GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced read, influences final coverage counts [46]. This effect varies between samples and even between different fragment lengths within a single sample, creating a complex bias landscape that requires sophisticated correction methods [48].

Experimental Data on GC-Bias Correction Methods

Recent methodological advances have produced specialized tools for GC-bias correction in cfDNA data. GCfix represents one such approach, developed following an in-depth analysis of cfDNA GC bias at the region and fragment length levels [47]. This method generates correction factors, tagged BAM files, and corrected coverage tracks, outperforming existing methods on two orthogonal performance metrics: (1) comparing the fragment count density distribution of GC content between expected and corrected samples, and (2) evaluating coverage profile improvement post-correction [47].

The Griffin framework implements a different strategy, employing a GC correction procedure tailored to variable cfDNA fragment sizes [48]. This approach computes genome-wide fragment-based GC bias for each sample, then reweights fragment midpoint coverage at sites of interest to remove these biases. The method has demonstrated significant improvements in nucleosome profiling, with correlations between central coverage at transcription factor binding sites and tumor fraction strengthening substantially after GC correction (e.g., for blood-specific TF LYL1, Pearson's r improved from 0.41 to 0.63) [48].

Table 2: Comparison of GC-Bias Correction Methods for cfDNA

| Method | Core Principle | Input Data | Key Advantage | Demonstrated Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCfix [47] | Fragment length-specific GC correction | WGS cfDNA data | Fast and accurate; works across diverse coverages | Outperforms existing methods on fragment count density and coverage profile metrics |

| Griffin Framework [48] | Fragment-based GC bias correction per sample; reweights midpoint coverage | ULP-WGS/WGS cfDNA data | Optimized for nucleosome profiling; suitable for ULP-WGS (0.1x) | Strengthened correlation between TFBS coverage and tumor fraction (e.g., r=0.41 to 0.63) |

| Benjamini & Speed Method [46] | Global expected coverage per fragment length/GC; assigns weights | Genomic DNA sequencing data | Foundational model for full-fragment GC bias correction | Inspired specialized cfDNA methods; identifies PCR as primary bias source |

Diagram 1: GC bias in cfDNA analysis arises from multiple sources during library preparation, particularly PCR amplification. It creates a unimodal coverage curve and can be addressed through both computational correction tools and optimized wet-lab protocols.

Fragment Length as an Informative Biomarker

Beyond its technical challenges, fragment length in cfDNA represents a rich source of biological information, particularly in oncology applications. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) demonstrates distinct fragment length signatures compared to background cfDNA from healthy cells [50]. In xenograft models, human ctDNA in rat plasma derived from glioblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma cells showed a shorter principal fragment length than the background rat cfDNA (134-144 bp vs. 167 bp, respectively) [50]. This size difference provides a potential mechanism for enriching the ctDNA fraction through experimental or bioinformatic size selection.