Evolutionary Arms Race: Comparative Mechanisms of Toxin Resistance in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

This review provides a systematic comparison of the fundamental and applied aspects of toxin resistance mechanisms across the prokaryotic and eukaryotic domains.

Evolutionary Arms Race: Comparative Mechanisms of Toxin Resistance in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

Abstract

This review provides a systematic comparison of the fundamental and applied aspects of toxin resistance mechanisms across the prokaryotic and eukaryotic domains. We explore the foundational principles, from enzymatic inactivation and efflux pumps in bacteria to target-site insensitivity and immune responses in complex organisms. The article assesses modern methodological approaches for studying these systems, including in silico analyses and database resources, and addresses key challenges such as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). By validating and contrasting these divergent evolutionary strategies, we highlight their direct implications for overcoming current bottlenecks in drug development, offering a roadmap for novel therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Core Defense Strategies: From Bacterial Enzymes to Eukaryotic Target-Site Mutations

In the continuous struggle for survival, organisms across all kingdoms of life produce a diverse arsenal of natural toxins. These compounds serve as key mediators of interference competition, defense, and pathogenesis by targeting fundamental cellular processes. The evolutionary arms race between toxin producers and their intended targets has shaped intricate resistance mechanisms at the molecular level. This comparative analysis examines the cellular targets of natural toxins and the corresponding resistance strategies evolved by prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, providing a framework for understanding these ancient biological battles and their applications in drug development and biotechnology.

Classification and Mechanisms of Natural Toxins

Natural toxins can be systematically categorized based on their origin, chemical structure, and molecular mechanisms of action. The following sections provide a detailed overview of the major toxin classes and their cellular targets.

Bacterial Toxins: Precision Molecular Weapons

Bacterial toxins represent sophisticated weaponry developed through evolutionary time to disrupt cellular function. They are broadly classified into pore-forming toxins and toxins with enzymatic activity, each employing distinct strategies to compromise target cells.

Pore-Forming Toxins disrupt cellular integrity by creating pores in the plasma membrane of target cells. Water-soluble monomers released by pathogenic bacteria bind to specific cellular receptors (lipids, glycolipids, glycoproteins, or proteins) and undergo oligomerization in the membrane [1]. This process is accompanied by remarkable conformational changes leading to the formation of water-filled pores, alteration of membrane potential, and eventual cell death due to ion imbalance and osmotic lysis [1]. Notable examples include:

- Cholesterol-Dependent Cytolysins (CDCs): These β-pore forming toxins, including streptolysin O and perfringolysin O, bind to cholesterol-rich membrane domains and create large pores ranging from 1-100 nm in diameter [1].

- Cytolysin A (ClyA): An α-pore-forming toxin produced by Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica that forms pores via membrane-spanning α-helices [1].

Toxins with Enzymatic Activity function as precision tools that enter target cells and modify specific intracellular components. Their enzymatic activities are diverse and highly specific:

- ADP-Ribosyltransferases (e.g., Cholera toxin, Pertussis toxin, Diphtheria toxin) modify target proteins by transferring ADP-ribose groups, altering their function [1].

- Proteases (e.g., Botulinum neurotoxin, Anthrax Lethal Factor) cleave specific cellular proteins essential for neuronal function or signaling pathways [1].

- Adenylyl Cyclases (e.g., Anthrax Edema Factor, Bordetella pertussis CyaA) dramatically increase intracellular cAMP levels, disrupting cellular signaling [1].

- Glycosyltransferases (e.g., Clostridioides difficile Toxins A and B) modify Rho GTPases through glucosylation, disrupting cytoskeletal organization [1].

- Deamidases (e.g., Cytotoxic necrotizing factors from E. coli) deamidate Rho GTPases, leading to constitutive activation and cellular dysfunction [1].

Table 1: Major Bacterial Toxin Classes and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Toxin Class | Representative Examples | Bacterial Source | Molecular Target | Enzymatic Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pore-forming | Streptolysin O, Perfringolysin O | Streptococcus pyogenes, Clostridium perfringens | Plasma membrane cholesterol | Forms membrane pores (25-30 nm diameter) |

| ADP-Ribosyltransferases | Cholera toxin, Diphtheria toxin | Vibrio cholerae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae | G-proteins, Elongation Factor 2 | NAD-dependent ADP-ribosylation |

| Proteases | Botulinum neurotoxin, Anthrax Lethal Factor | Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus anthracis | SNARE proteins, MAPKKs | Zinc-dependent metalloprotease |

| Adenylyl Cyclases | Edema Factor, CyaA | Bacillus anthracis, Bordetella pertussis | intracellular ATP | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase |

| Glycosyltransferases | Toxin A, Toxin B | Clostridioides difficile | Rho GTPases | UDP-glucose-dependent glycosyltransferase |

| Deamidases | Cytotoxic necrotizing factor | Escherichia coli | Rho GTPases | Glutamine deamidation |

Plant Toxins: Diverse Chemical Defenses

Plants have evolved numerous toxic proteins as defense mechanisms against herbivores, insects, and pathogens. These compounds target essential biological processes and represent powerful chemical deterrents [2].

Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins (RIPs) are cytotoxic enzymes that inhibit protein synthesis by catalytically inactivating ribosomes. They are classified into three types based on their structure:

- Type I RIPs (e.g., pokeweed antiviral protein, trichosanthin, saporin) are single-chain proteins of approximately 30 kDa with RNA N-glycosidase activity [2].

- Type II RIPs (e.g., ricin, abrin) consist of an enzymatic A-chain and a lectin-like B-chain that facilitates cellular entry through binding to galactose residues on cell surfaces [2].

- Type III RIPs (e.g., maize b32) contain an N-terminal domain with glycosidase activity and a C-terminal domain of uncertain function [2].

The primary mechanism of RIP toxicity involves the enzymatic removal of a specific adenine residue (A-4324) from the 28S rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit, which inhibits the binding of elongation factors and consequently blocks protein synthesis [2]. Additionally, many RIPs exhibit polynucleotide adenine glycosylase (PAG) activity on various nucleic acid substrates and may possess other enzymatic activities including chitinase, lipase, and superoxide dismutase functions [2].

Other Plant Toxic Proteins include:

- Lectins: Carbohydrate-binding proteins that can agglutinate cells and disrupt cellular recognition.

- Protease Inhibitors: Interfere with digestive enzymes in herbivores.

- α-Amylase Inhibitors: Block carbohydrate digestion.

- Ureases and Arcelins: Exhibit insecticidal and defensive properties.

- Antimicrobial Peptides: Broad-spectrum defense molecules against microorganisms [2].

Trans-Kingdom Toxin Systems

Recent research has identified sophisticated toxin delivery systems that operate across kingdom boundaries. The Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) functions as a molecular syringe that injects effector proteins directly into both prokaryotic and eukaryotic target cells [3]. For example, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis secretes TseR, a trans-kingdom T6SS RNase effector that contains an Ntox44 domain and exhibits divalent cation-dependent RNase activity [3]. This effector preferentially cleaves single-stranded RNA and can mediate bacterial killing through both contact-dependent and contact-independent mechanisms, with OmpC facilitating its entry during contact-independent killing [3]. During infection, TseR alters the host gut microbiome and directly targets eukaryotic host cells, demonstrating how single toxin effectors can function across biological kingdoms [3].

Figure 1: Trans-kingdom toxin mechanism of T6SS RNase effector TseR in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis

Cellular Targets of Natural Toxins

Fundamental Processes as Toxin Targets

Natural toxins have evolved to target conserved cellular components and processes essential for life. The most critical targets include:

Protein Synthesis Machinery: Multiple toxins directly target the translation apparatus. RIPs depurinate specific adenine residues in the α-sarcin/ricin loop (α-SRL) of 28S rRNA, preventing elongation factor binding and inhibiting protein synthesis [2]. Diphtheria toxin ADP-ribosylates elongation factor 2 (EF-2), rendering it inactive and halting polypeptide chain elongation [1].

Membrane Integrity: Pore-forming toxins directly compromise the plasma membrane's barrier function by creating aqueous channels. The size of these pores varies significantly, with cholesterol-dependent cytolysins forming particularly large pores (25-30 nm) that allow uncontrolled passage of ions and small molecules [1].

Signal Transduction Pathways: Many bacterial toxins modulate key signaling molecules. Cytotoxic necrotizing factors (CNF1, CNF2, CNF3) from E. coli and CNFY from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis deamidate Rho GTPases, leading to constitutive activation and disruption of cytoskeletal dynamics [1]. Similarly, Pasteurella multocida toxin and Bordetella bronchiseptica dermonecrotic toxin target Rho GTPases through deamidation and transglutamination, respectively [1].

Ion Homeostasis: Plant-derived cardenolides from milkweed and foxglove target the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase) in animal cells [4]. These compounds bind to a specific site on the pump protein, turning it off and disrupting the critical ion gradient necessary for numerous cellular functions, including neuronal transmission and muscle contraction [4].

Gene Expression: The newly discovered T6SS RNase effector TseR from Y. pseudotuberculosis targets RNA molecules in both bacterial and eukaryotic cells [3]. This divalent cation-dependent RNase preferentially cleaves single-stranded RNA, disrupting gene expression globally and mediating pathogenesis through alteration of the host gut microbiome [3].

Comparative Target Vulnerability

The essential nature of certain cellular processes makes them vulnerable targets for toxin action across biological systems. Protein synthesis, being universally essential and highly conserved, represents the most frequently targeted process. Membrane integrity represents another fundamental target, as all cells require intact membranes to maintain homeostasis. Signaling pathways show more kingdom-specific targeting, with eukaryotic-specific signaling components (e.g., heterotrimeric G proteins) being targeted by certain bacterial toxins, while conserved GTPases (Rho family) are targeted across kingdoms.

Table 2: Cellular Targets of Natural Toxins Across Biological Kingdoms

| Target Category | Specific Target | Toxin Examples | Producer Organisms | Effect on Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation Machinery | 28S rRNA | Ricin, Abrin | Plants (Ricinus communis, Abrus precatorius) | Adenine depurination, inhibits EF binding |

| Elongation Factor 2 | Diphtheria toxin | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | ADP-ribosylation, inhibits function | |

| Membrane Integrity | Plasma membrane cholesterol | Streptolysin O, Perfringolysin O | Streptococcus pyogenes, Clostridium perfringens | Forms large pores (25-30 nm), osmotic lysis |

| General membrane lipids | Cytolysin A (ClyA) | Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica | Forms α-helical pores, membrane disruption | |

| Signaling Molecules | Rho GTPases | Cytotoxic necrotizing factor, Toxin B | Escherichia coli, Clostridioides difficile | Deamidation/glucosylation, constitutive activation |

| G-proteins | Cholera toxin, Pertussis toxin | Vibrio cholerae, Bordetella pertussis | ADP-ribosylation, altered signaling | |

| MAP Kinase Kinases | Anthrax Lethal Factor | Bacillus anthracis | Proteolytic cleavage, disrupts signaling | |

| Ion Transport | Na+/K+ ATPase | Cardenolides | Plants (milkweed, foxglove) | Inhibits pump function, disrupts ion gradients |

| Gene Expression | Cellular RNA | TseR RNase effector | Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | RNA cleavage, disrupts gene expression |

Defense and Resistance Mechanisms

Prokaryotic Resistance Strategies

Bacteria have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to resist toxins from competitors and environmental challenges:

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: These abundant genetic elements encode a toxin protein that inhibits cell growth and an antitoxin that counteracts the toxin [5]. The majority of toxins are enzymes that interfere with translation or DNA replication, but a wide variety of molecular activities and cellular targets have been described [5]. Antitoxins are proteins or RNAs that often control their cognate toxins through direct interactions and, in conjunction with other signaling elements, through transcriptional and translational regulation of TA module expression [5]. These systems function in post-segregational killing ("plasmid addiction"), abortive infection (bacteriophage immunity through altruistic suicide), and persister formation (antibiotic tolerance through dormancy) [5].

Second Messenger Signaling: Bacteria utilize various low-molecular-weight non-proteinaceous molecules, called alarmones or second messengers, to coordinate cellular responses to stress and toxin exposure [6]. These include:

- (p)ppGpp: The effector of the stringent response, activated upon nutrient limitation and various stresses, which reprograms cellular metabolism toward survival [6].

- c-di-GMP: Generally known to regulate bacterial lifestyle transition from motile to sedentary, biofilm formation, cell cycle, and virulence [6].

- c-di-AMP: Involved in potassium and cell wall homeostasis [6].

- cAMP: Governs carbon source utilization in Gram-negative bacteria through binding to the CRP regulator [6].

DNA Repair and Genomic Integrity: Bacteria maintain genome stability through control of DNA replication and repair processes, which is indispensable for maintaining cellular functions under toxin-induced stress [6].

Arsenic-Specific Resistance: Prokaryotes have evolved elaborate mechanisms for arsenic resistance involving dedicated pathways for detoxification and extrusion [7] [8]. These include:

- Arsenite extrusion via ArsB and ACR3 membrane transporters [7] [8].

- Arsenate reduction to arsenite by arsenate reductases (ArsC) [8].

- Arsenite methylation to less toxic forms by arsenite methyltransferases (ArsM) [7].

Eukaryotic Resistance Strategies

Eukaryotes have developed distinct countermeasures against natural toxins:

Target Site Insensitivity: Some herbivores evolve resistant versions of target proteins through mutations that prevent toxin binding while maintaining normal function [4]. For example, insects feeding on milkweed and foxglove plants make versions of the sodium-potassium pump with amino acid substitutions in the cardenolide-binding site, rendering them insensitive to these toxins while maintaining ion transport function [4].

Detoxification Enzymes: Eukaryotes employ specialized enzyme systems, particularly cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs), to metabolize and neutralize toxins [4]. These enzymes begin the process by which cells turn toxic compounds into harmless molecules that the body can use or excrete [4]. Most insects have a large collection of CYP genes (some over 150), each coding for proteins that interact with different sets of molecules [4].

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Some eukaryotes have acquired resistance genes from bacterial sources through horizontal gene transfer [9] [7]. For example, the alga Galdieria sulphuraria, which lives in highly acidic environments rich in arsenic, acquired the arsenic efflux protein ArsB through HGT from bacteria, facilitating niche adaptation [7]. Multiple transfers of arsenite methyltransferases (ArsM) have also increased arsenic tolerance in various eukaryotic lineages [7].

Vacuolar Sequestration: Plants and fungi can compartmentalize toxins away from sensitive cellular components. In response to arsenic exposure, both prokaryotes and higher plants reduce cytosolic arsenic concentration through transporters that operate either in arsenite extrusion out of cells or by sequestering arsenic into vacuoles [8].

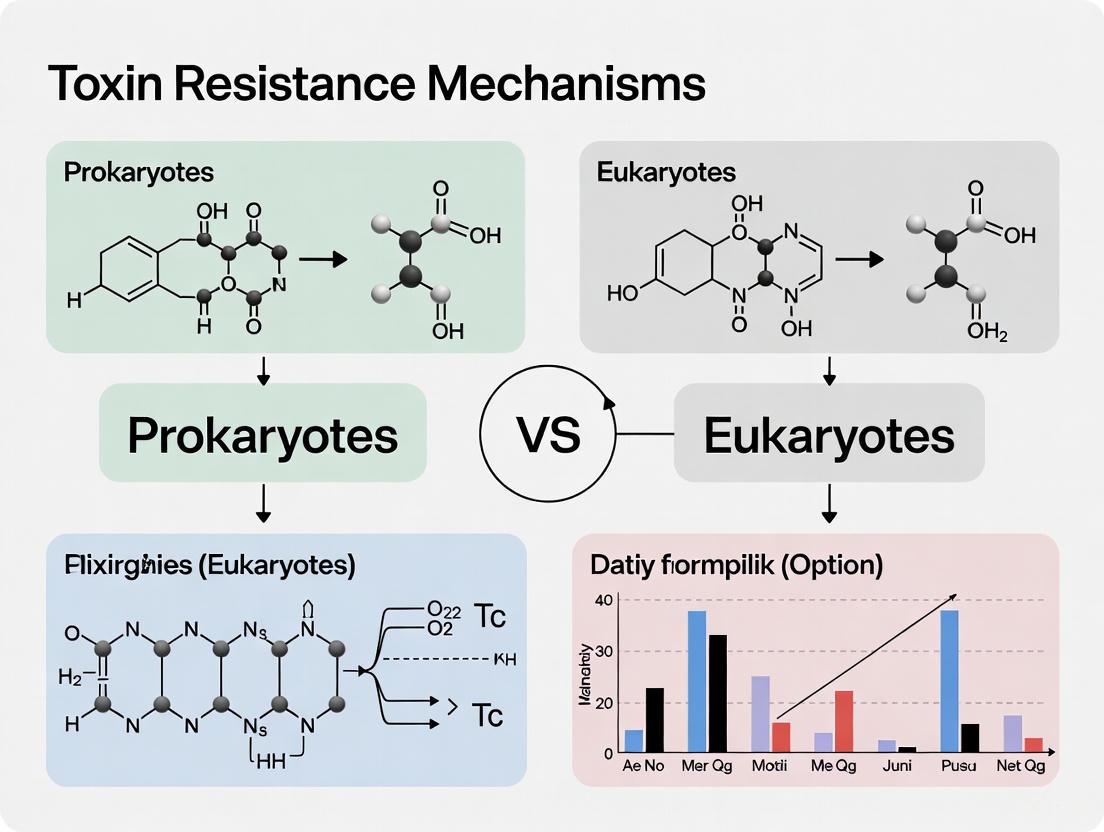

Figure 2: Comparative resistance mechanisms in prokaryotes and eukaryotes

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Research on toxin mechanisms and resistance employs specialized methodologies:

Bacterial Competition Assays: For studying T6SS-mediated toxicity, researchers employ both contact-dependent and contact-independent competition assays [3]. In contact-dependent assays, donor and recipient bacterial strains are co-cultured on solid media for direct physical interaction, while contact-independent assays use culture supernatants or purified toxins added to recipient cultures, with OmpC facilitating toxin entry in some systems [3]. Viability is measured through colony-forming unit counts or fluorescent viability stains.

RNA-Seq Analysis of Toxin Targets: To identify global RNA targets of RNase effectors like TseR, researchers perform RNA sequencing on toxin-treated cells [3]. The protocol involves: (1) treatment of E. coli cultures with purified TseR effector, (2) RNA extraction at multiple time points, (3) library preparation and sequencing, (4) bioinformatic analysis to identify cleavage sites and preferential targets [3].

Membrane Permeabilization Measurements: Pore-forming toxin activity is quantified using black lipid membrane (BLM) experiments that determine biophysical properties including ion selectivity and channel size [1]. Additional methods include dye release assays from lipid vesicles, and measurement of ion flux in eukaryotic cells using patch-clamp electrophysiology [1].

Arsenic Resistance Phenotyping: Comprehensive assessment of arsenic tolerance involves growth assays under arsenic stress, measurement of intracellular arsenic accumulation via atomic absorption spectroscopy, and speciation analysis of arsenic compounds using HPLC-ICP-MS [7] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Toxin Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore-Forming Toxins | Streptolysin O, Perfringolysin O | Membrane permeabilization studies | Creates controlled pores for intracellular delivery of small molecules, peptides, or drugs [1] |

| Engineered Toxin Systems | Modified Anthrax Protective Antigen | Targeted drug delivery | Engineered to recognize specific cell surface markers (e.g., EGFR, Her2) for cancer cell targeting [1] |

| Toxin Domains as Biosensors | Domain 4 of Perfringolysin O (PFO) | Cholesterol domain visualization | Binds specifically to cholesterol-rich membrane nanodomains for imaging [1] |

| Plant RIPs | Ricin, Abrin, Saporin | Ribosome function studies, anticancer research | Inhibits protein synthesis; studied for apoptotic effects on cancer cells [2] |

| Second Messenger Analogs | (p)ppGpp, c-di-GMP, cAMP | Bacterial stress response studies | Modulates transcriptional networks in bacterial homeostasis and stress response [6] |

| Detoxification Enzyme Assays | CYP enzyme substrates | Insecticide resistance research | Measures metabolic capability against plant toxins and synthetic pesticides [4] |

The comparative analysis of natural toxins and their cellular targets reveals fundamental principles of biological conflict and adaptation. The evolutionary arms race between toxin producers and target organisms has generated remarkable molecular diversity in both offensive weapons and defensive countermeasures. Understanding these intricate interactions provides valuable insights for therapeutic development, including the engineering of toxins for targeted cancer therapies [1] [10], the development of novel antibiotics targeting bacterial-specific systems [6], and strategies to overcome pesticide resistance in agriculture [4]. The continued study of these natural molecular battles will undoubtedly yield new tools for medicine and biotechnology while enhancing our understanding of fundamental biological processes across the kingdoms of life.

Prokaryotes have evolved a sophisticated arsenal of molecular mechanisms to manage toxins, including antibiotics, environmental stressors, and metabolic by-products. This guide provides a comparative assessment of three core mechanisms—enzymatic degradation, efflux pumps, and toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems—contrasting their operation in prokaryotic cells with the fundamentally different biology of eukaryotic cells. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for drug development, as they contribute significantly to bacterial pathogenicity and antibiotic resistance [11] [12]. For researchers, appreciating the distinct structural and functional biology of prokaryotes versus eukaryotes is the first step in designing targeted therapeutic strategies [13]. This comparison lays the groundwork for developing novel antibacterial agents that exploit unique prokaryotic pathways while minimizing off-target effects in human hosts.

Comparative Analysis of Core Resistance Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary toxin resistance mechanisms in prokaryotes, providing a direct comparison of their functions and components.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Prokaryotic Toxin Resistance Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Primary Function | Key Components | Energy Source | Key Experimental Substrates/Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Degradation | Chemical modification or breakdown of toxic molecules [12] | Bacterial enzymes (e.g., β-lactamases) [12] | Chemical energy from reaction | Antibiotic susceptibility testing, HPLC/MS for degradation products [12] |

| Efflux Pumps | Active transport of toxins out of the cell [14] [15] | Membrane transport proteins (e.g., AcrB, TolC) [14] | Proton motive force or ATP [15] | Ethidium bromide accumulation assays, MIC determination with EPIs [14] |

| Toxin-Antitoxin Systems | Stress response, persistence formation, phage defense [11] [16] | Toxic protein and its cognate antitoxin (RNA or protein) [17] | N/A (Constitutive or stress-induced expression) | Bacterial two-hybrid assays, spot dilution assays, microscopy for persistence [17] [18] |

Mechanism 1: Enzymatic Degradation

Functional and Comparative Analysis

Enzymatic degradation involves the production of specific bacterial enzymes that inactivate toxic compounds, most notably antibiotics, through modification or hydrolysis [12]. A classic example is the production of β-lactamases, enzymes that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of penicillin and related antibiotics, rendering them ineffective [12]. This mechanism is highly efficient and specific, but its major limitation is that each enzyme typically targets a single class or a limited range of antibiotic structures.

From a comparative perspective, this mechanism is largely unique to prokaryotes as a defense against antibiotics. While eukaryotes possess vast arrays of detoxifying enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 family), these generally target environmental toxins or metabolic waste and do not confer resistance to classical antibiotics. The fundamental difference lies in the targets: prokaryotic enzymes often directly attack the core chemical structure of synthetic or semi-synthetic antibacterial compounds, whereas eukaryotic detoxification systems are adapted to a different set of natural products and xenobiotics.

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Characterization

Protocol 1: Measuring Antibiotic Degradation Kinetics

- Culture the bacterial strain of interest to mid-log phase in an appropriate broth.

- Incubate a standardized inoculum with a known concentration of the antibiotic in a liquid medium.

- Sample the supernatant at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Assay for remaining antibiotic activity using a bioassay with a susceptible indicator strain or via analytical methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to detect the intact antibiotic and its breakdown products [12].

- Calculate the degradation rate based on the reduction of antibiotic concentration or activity over time.

Protocol 2: Confirmatory Disk Diffusion Assay for Enzyme Production

- Spread a lawn of a standardized, antibiotic-susceptible indicator strain on an agar plate.

- Place an antibiotic-impregnated disk in the center.

- Apply the bacterial culture supernatant or a purified enzyme preparation adjacent to the disk.

- Incubate and observe for a distortion or indentation in the zone of inhibition around the disk, indicating enzymatic inactivation of the antibiotic diffusing from the disk [12].

Mechanism 2: Multidrug Efflux Pumps

Functional, Structural, and Comparative Analysis

Multidrug efflux pumps are membrane-spanning transporter proteins that actively export a wide range of structurally unrelated toxic compounds from the bacterial cell, thereby reducing the intracellular concentration to sub-lethal levels [14] [15]. These pumps are major contributors to intrinsic and acquired multidrug resistance (MDR) in bacteria. They are classified into several families based on their structure and energy source, with the Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family being particularly clinically significant in Gram-negative bacteria [14] [15].

Table 2: Classification and Characteristics of Major Bacterial Efflux Pump Families

| Efflux Pump Family | Representative Example | Primary Energy Source | Typical Substrate Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC (ATP-binding cassette) | MacAB (E. coli) [14] | ATP Hydrolysis | Macrolides, peptides [14] |

| MFS (Major Facilitator Superfamily) | EmrB (E. coli) [15] | Proton Motive Force | Various antibiotics, dyes, detergents [15] |

| RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) | AcrB (E. coli), MexB (P. aeruginosa) [14] [15] | Proton Motive Force | Broad range: β-lactams, quinolones, macrolides, dyes, detergents [14] |

| MATE (Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion) | NorM (V. parahaemolyticus) [14] | Proton/Sodium Ion Gradient | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides [14] |

| SMR (Small Multidrug Resistance) | EmrE (E. coli) [14] | Proton Motive Force | Small, hydrophobic cations, disinfectants [14] |

The RND-type pumps in Gram-negative bacteria, such as the AcrAB-TolC system in E. coli, form complex tripartite structures that span the entire cell envelope. The inner membrane component (e.g., AcrB) captures substrates from the cytoplasm and periplasm, the periplasmic adapter protein (e.g., AcrA) forms a bridge, and the outer membrane protein (e.g., TolC) forms a channel to the exterior [14]. This architecture allows them to expel drugs directly into the external medium, bypassing the permeability barrier of the outer membrane.

In contrast, eukaryotic cells possess their own set of efflux pumps, most notably the P-glycoprotein (MDR1), which is an ABC transporter that contributes to MDR in cancer cells [14]. While the function of expelling toxins is analogous, the prokaryotic and eukaryotic pumps are structurally and evolutionarily distinct. They exhibit no sequence homology and utilize different energy-coupling mechanisms. This divergence presents a drug development opportunity, as inhibitors can be designed to specifically target prokaryotic pumps without cross-reacting with human counterparts.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Analysis

Protocol 1: Ethidium Bromide Accumulation Assay

- Prepare a bacterial suspension in a suitable buffer with a known OD600.

- Load the cells with Ethidium Bromide (EtBr), a fluorescent efflux pump substrate.

- Add an energy source (e.g., glucose) to initiate active efflux.

- Monitor fluorescence over time in a spectrofluorometer. A decrease in fluorescence indicates active efflux of EtBr. The assay can be repeated in the presence and absence of an efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) like Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) to confirm the energy-dependent nature of the efflux [15].

- Calculate accumulation ratios by comparing fluorescence levels with and without an energy source or inhibitor.

Protocol 2: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Profiling with Inhibitors

- Determine the MIC of various antibiotics against the target strain using standard broth microdilution methods.

- Repeat the MIC determination in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of a known EPI (e.g., Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide for RND pumps).

- A significant reduction (e.g., ≥4-fold) in the MIC of an antibiotic in the presence of the EPI is indicative of that antibiotic being a substrate for the efflux pump system [14].

Diagram 1: RND-type efflux pump mechanism. The diagram illustrates the tripartite structure and proton-driven export of antibiotics.

Mechanism 3: Toxin-Antitoxin Systems

Functional, Genetic, and Comparative Analysis

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic modules composed of a stable toxin protein that disrupts essential cellular processes and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [17]. Under normal growth conditions, the antitoxin is produced in excess, forming a complex that represses the TA operon. Under stress (e.g., nutrient starvation, antibiotic exposure), the labile antitoxin is degraded, freeing the toxin to act on its target and induce a state of growth arrest or persistence, which is thought to promote survival under adverse conditions [11] [17] [16]. These systems are categorized into six types (I-VI) based on the nature and mode of action of the antitoxin.

Table 3: Classification of Major Toxin-Antitoxin System Types

| TA System Type | Antitoxin Nature | Mechanism of Antitoxin Action | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Non-coding RNA [17] | Binds toxin mRNA, preventing translation [17] | hok/sok (Plasmid R1) [17] |

| Type II | Protein [17] | Binds toxin protein, neutralizes activity [17] | RelB/RelE (E. coli), Kid/Kis (Plasmid R1) [17] [18] |

| Type III | Non-coding RNA [17] | Directly binds toxin protein [17] | ToxN/ToxI (B. subtilis) [17] |

| Type IV | Protein [17] | Binds toxin target, preventing toxin action [17] | CbtA/CbeA (E. coli) [17] |

| Type V | Protein [17] | Cleaves toxin mRNA [17] | GhoS/GhoT (E. coli) [17] |

The physiological role of TA systems is complex and includes functions in phage defense, stabilization of genomic parasites, and stress response [16]. Recent research suggests that TA systems do not induce uniform growth stasis across a population but rather create phenotypic heterogeneity, leading to subpopulations of cells with different metabolic states and stress tolerance levels [16].

Strikingly, some prokaryotic TA systems have been shown to function efficiently in eukaryotes. The Kid toxin from the parD system of plasmid R1 inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in human cells, while its cognate antitoxin Kis neutralizes this effect [18]. This cross-kingdom functionality highlights the conservation of some fundamental cellular targets and pathways. For drug development, TA systems represent attractive targets for novel antibacterial strategies that could disrupt the toxin-antitoxin balance to trigger bacterial cell death or sensitize persistent cells to conventional antibiotics.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: Bacterial Two-Hybrid Assay for Protein-Protein Interaction

- Clone the toxin and antitoxin genes into the appropriate two-hybrid vectors (e.g., encoding complementary fragments of adenylate cyclase in the BACTH system).

- Co-transform the constructs into an E. coli reporter strain.

- Plate transformants on selective media containing X-Gal.

- A positive protein-protein interaction between the toxin and antitoxin is indicated by the restoration of adenylate cyclase activity, leading to β-galactosidase production and blue colonies [17].

Protocol 2: Spot Dilution Assay for Toxicity and Neutralization

- Clone the toxin gene under a tightly regulated, inducible promoter (e.g., araBAD, rhamnose) on a plasmid.

- Clone the antitoxin gene under a constitutive or independently inducible promoter on a compatible plasmid.

- Transform the plasmids into the appropriate bacterial strain.

- Induce toxin expression in serial dilutions of the culture spotted on agar plates.

- Assess cell growth: Toxicity is evidenced by lack of growth upon induction, which is rescued by co-expression of the antitoxin [18].

Diagram 2: Type II TA system regulation. The diagram shows stress-induced antitoxin degradation leading to toxin activation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and their applications for studying the prokaryotic toxin resistance mechanisms discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Prokaryotic Defense Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function/Application | Specific Use-Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) | Protonophore; dissipates proton motive force [15] | Positive control in efflux pump assays to inhibit energy-dependent efflux [15]. |

| Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN) | Broad-spectrum efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) for RND pumps [14] | Used in MIC assays to potentiate antibiotic activity and identify pump substrates [14]. |

| pBAD or pRham Vectors | Tightly regulated, inducible expression systems | Controlled expression of toxin genes for toxicity assays in bacteria and eukaryotes [18]. |

| Bacterial Adenylate Cyclase-Based Two-Hybrid (BACTH) System | In vivo detection of protein-protein interactions [17] | Validation of direct binding between Type II toxin and antitoxin proteins [17]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Ethidium Bromide) | Substrates for many multidrug efflux pumps [15] | Used in real-time fluorometric assays to quantify efflux pump activity. |

| Anti-Serial Dilution Plating | Method for quantifying bacterial persistence | Measuring the fraction of persister cells surviving antibiotic treatment, a phenotype linked to TA systems [16]. |

The comparative assessment of enzymatic degradation, efflux pumps, and toxin-antitoxin systems reveals a multi-layered defensive strategy in prokaryotes. Enzymatic degradation offers high specificity, efflux pumps provide broad-spectrum protection, and TA systems contribute to population survival under extreme stress. The functional conservation of some systems, like TA modules, in eukaryotes [18] underscores the presence of ancient, fundamental cellular pathways, while the structural divergence of others, like efflux pumps [14], highlights unique evolutionary paths. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative framework is invaluable. It identifies vulnerable nodes—such as the protein-protein interface in Type II TA systems, the energy-coupling mechanism of RND efflux pumps, and the active sites of inactivating enzymes—that can be targeted for the rational design of next-generation antimicrobials and potentiators capable of overcoming multidrug resistance.

The continuous exposure to environmental toxins, antimicrobial compounds, and chemical weapons produced by competitors has driven the evolution of sophisticated defense mechanisms across the tree of life. Eukaryotes and prokaryotes have developed distinct yet sometimes convergent strategies to detect, neutralize, and eliminate these toxic threats. Eukaryotic systems have evolved complex, multi-layered defenses that integrate transcriptional regulation, protein trafficking, and immune surveillance pathways to maintain cellular integrity against toxic assaults. Meanwhile, prokaryotes employ more direct mechanisms centered on toxin-immunity protein pairs and efflux transporters. Understanding these divergent strategies provides crucial insights for addressing pressing challenges in drug development, pesticide resistance, and antimicrobial therapy. This review comprehensively compares the molecular machinery underlying toxin resistance, highlighting both the fundamental distinctions and remarkable convergences between eukaryotic and prokaryotic systems, with emphasis on the clinical and agricultural applications of these findings.

Eukaryotic Detoxification Pathways: Multi-Layered Defense Systems

Transcriptional Regulation of Detoxification Genes

Eukaryotic cells employ sophisticated transcriptional programs to regulate detoxification genes, allowing them to rapidly adapt to xenobiotic challenges. Key transcriptional pathways identified in insects and fungi demonstrate remarkable evolutionary convergence with mammalian systems. In insects, several well-characterized transcriptional pathways regulate the expression of detoxification enzymes, including cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), carboxyl esterases (CarE), and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters [19] [20]. The principal transcriptional regulators include:

- AhR/ARNT Pathway: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its partner ARNT that bind xenobiotic response elements

- CncC/Keap1 Pathway: Conserved cap'n'collar transcription factor and its negative regulator Keap1 that responds to oxidative stress

- Nuclear Receptors: Ligand-activated transcription factors that directly bind xenobiotics

- MAPK/CREB and GPCR/cAMP/PKA Pathways: Signal transduction cascades that connect extracellular signals to transcriptional activation [19] [20]

Similar regulatory mechanisms operate in fungi. Research on the filamentous fungus Sclerotinia homoeocarpa revealed that a fungus-specific transcription factor, ShXDR1, coordinately regulates both phase I (CYPs) and phase III (ABC transporters) detoxification genes [21]. A gain-of-function mutation (M853T) in ShXDR1 causes constitutive overexpression of these genes, resulting in multidrug resistance to various fungicidal chemicals [21]. This system represents a functional analog to the mammalian pregnane X receptor (PXR) pathway, demonstrating convergent evolution between fungal and mammalian lineages in regulating xenobiotic detoxification [21].

Figure 1: Transcriptional regulation of detoxification genes in eukaryotic systems. Insects utilize the CncC/Keap1 pathway where xenobiotics inactivate Keap1, releasing Nrf2/CncC to activate gene expression. Fungi employ XDR1 transcription factors, with gain-of-function mutations leading to constitutive detoxification gene expression.

Post-Transcriptional Regulation by Non-Coding RNAs

Eukaryotes employ extensive post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms mediated by non-coding RNAs that fine-tune detoxification responses. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as crucial regulators of insecticide resistance in various insect species [19] [20]. These small non-coding RNAs, typically 18-25 nucleotides in length, regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences in target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [20]. miRNAs typically bind to the 3'-untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs through imperfect base pairing, with the "seed" sequence (nucleotides 2-8 at the 5' end) playing a critical role in target recognition [19].

In resistant insect populations, specific miRNAs have been shown to target detoxification genes, including P450 enzymes, GSTs, and esterases [19]. The expression of these miRNAs is influenced by oxidative and cellular stress, creating a dynamic regulatory network that allows insects to rapidly adapt to insecticide exposure [20]. Beyond miRNAs, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and epitranscriptomic modifications such as RNA methylation also contribute to insecticide resistance, although their mechanisms are less well-characterized [19].

Protein Trafficking and Cellular Defense Mechanisms

Eukaryotic cells have evolved sophisticated protein trafficking systems that contribute to toxin defense. Recent research in yeast has revealed that the conserved oligomeric Golgi (COG) complex is essential for resistance to the AB toxin K28 [22]. The COG complex mediates the retrograde trafficking of the defense factor Ktd1, which surveys endolysosomal compartments for toxins and provides protection [22]. In cog mutants, mis-localization of Ktd1 results in hypersensitivity to K28 toxin, demonstrating the critical importance of precise cellular trafficking in toxin defense [22].

Eukaryotic cells also employ ribosome-mediated stress surveillance systems. Recent research has revealed that ribosomes not only synthesize proteins but also function as sophisticated stress sensors. When ribosomes stall and collide due to cellular stress—such as limited amino acids, damaged mRNA, or viral infections—they activate the ribotoxic stress response (RSR) [23]. This response is mediated by the kinase ZAK, which detects ribosome collisions and initiates signaling cascades that trigger protective responses, including DNA repair mechanisms or programmed cell death [23]. The discovery of this "hidden alarm system" reveals how eukaryotic cells quickly detect trouble at the translational level and mount an appropriate defense.

Prokaryotic Defense Mechanisms: Direct and Efficient Countermeasures

Toxin-Immunity Protein Systems

Prokaryotes employ primarily toxin-immunity protein systems as their fundamental defense strategy against antimicrobial toxins produced by competitors. These systems consist of antimicrobial toxins that inhibit the growth of competing strains and cognate immunity proteins that protect the producer cells from self-intoxication [24]. The genes encoding toxin-immunity pairs are typically located adjacent to each other in bacterial genomes, ensuring coordinated expression [24]. The Prokaryotic Antimicrobial Toxin database (PAT) currently contains 441 experimentally validated antimicrobial toxin proteins from 70 prokaryotic genera, with over 40% reported in the past five years, reflecting the rapid expansion of this field [24].

Prokaryotic antimicrobial toxins exhibit remarkable functional diversity, including:

- Nucleases that target DNA or RNA of competitor cells

- Phospholipases or pore-forming toxins that disrupt cell membranes

- Glycoside hydrolases or proteases that degrade cell walls

- NADases that disrupt cellular energy balance

- ADP-ribosyltransferases that target tubulin-like proteins to prevent cell division [24]

These toxin-immunity systems are distributed across diverse secretion mechanisms, including contact-dependent systems like T6SS, T4SS, and T7SS, as well as contact-independent secretion of bacteriocins [24].

Complement-Like Killing Mechanisms in Bacteria

Recent research has revealed unexpected complexity in prokaryotic toxin systems, including mechanisms that resemble eukaryotic immune effectors. In the Gram-negative Bacteroidota, a family of two-component CDC-like (CDCL) toxins functions similarly to the mammalian membrane attack complex (MAC) [25]. Unlike their CDC relatives that target eukaryotic cells, CDCLs bind to and kill closely related bacterial species [25].

The CDCL system requires proteolytic activation of two components (CDCLL and CDCLS) that then interact to form a pore, resulting in bacterial cell death [25]. The producing bacteria protect themselves from their own CDCL toxins through surface lipoproteins that block pore formation [25]. Genomic analyses reveal that these CDCL genes are widespread in human gut Bacteroidales species and are often located on mobile genetic elements, facilitating their distribution across diverse bacterial populations [25].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Toxin Resistance Mechanisms in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

| Feature | Prokaryotic Systems | Eukaryotic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Defense Strategy | Toxin-immunity protein pairs | Transcriptional regulation of detoxification enzymes |

| Key Regulatory Components | Adjacent gene organization | Transcription factors (CncC/Keap1, XDR1, nuclear receptors) |

| Detoxification Phases | Limited phase variation | Coordinated phase I-III detoxification |

| Cellular Surveillance | Restriction-modification systems | Ribotoxic stress response (ZAK kinase) |

| Export Mechanisms | Specialized secretion systems (T6SS, T4SS) | ABC transporters, membrane trafficking |

| Intercellular Signaling | Contact-dependent inhibition | Hormonal signaling, paracrine factors |

| Evolutionary Adaptation | Horizontal gene transfer | Gene duplication, alternative splicing |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols in Toxin Resistance Research

RNA Sequencing for Detoxification Gene Profiling: Next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has been instrumental in identifying detoxification genes involved in multidrug resistance. The protocol typically involves treating sensitive and resistant strains with sublethal concentrations of the toxic compound (e.g., 0.1 µg/ml propiconazole for fungi) for short periods (1 hour), followed by RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [21]. Bioinformatics analyses then identify differentially expressed genes, particularly focusing on detoxification enzyme families such as CYPs, GSTs, and ABC transporters [21]. This approach revealed the coordinated overexpression of phase I and III detoxification genes in multidrug-resistant fungal strains [21].

Molecular Docking for Detoxification Enzyme Discovery: Computational approaches, particularly molecular docking, have become valuable tools for identifying potential detoxification enzymes. Reverse molecular docking platforms screen a given ligand (e.g., a toxin) against numerous potential protein targets [26]. Software such as AutoDock, VINA, GOLD, and FRED use conformation search algorithms and scoring functions to predict binding modes and affinities [26]. A consensus strategy employing multiple docking algorithms often provides more reliable predictions than single software approaches [26]. These methods have been successfully used to identify key residues in enzymes that interact with toxins, such as the interaction between QDDH and deoxynivalenol (DON) [26].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy for Structural Analysis: Structural biology techniques, particularly cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have been crucial for understanding the mechanisms of toxin resistance and defense. In the study of ZAK kinase activation by ribosome collisions, researchers combined biochemical experiments with cryo-EM to demonstrate how ZAK attaches to collided ribosomes and identified the structural features necessary for its activation [23]. This approach revealed that ZAK interacts with specific ribosomal proteins, causing dimerization that initiates cellular signaling cascades [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in Toxin Resistance Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Propiconazole | Demethylation inhibitor fungicide | Used to induce detoxification gene expression in fungal strains [21] |

| Carboxyfluorescein | Fluorescent dye for pore formation assays | Loaded into liposomes to monitor CDCL toxin activity [25] |

| Trypsin | Proteolytic enzyme for toxin activation | Required for proteolytic activation of CDCL toxins [25] |

| POPC Liposomes | Artificial membrane systems | Used to study pore-forming activity of toxins in controlled environments [25] |

| α-rhamnosidase/β-glucosidases | Detoxification enzymes | Sequentially hydrolyze antifungal saponins in plant-pathogen interactions [26] |

| iKIX1 | Protein-protein interaction inhibitor | Disrupts PDR1-mediator interaction to combat multidrug resistance in fungi [21] |

Comparative Analysis and Evolutionary Perspectives

The comparative analysis of toxin resistance mechanisms reveals both striking divergences and remarkable convergences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic strategies. Prokaryotes employ direct, efficient systems centered on toxin-immunity protein pairs that provide immediate protection against specific threats [24]. These systems are often encoded on mobile genetic elements, facilitating rapid horizontal transfer through microbial communities [24]. In contrast, eukaryotes have evolved multi-layered regulatory networks that integrate transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and protein trafficking mechanisms to provide flexible, inducible responses to diverse toxic challenges [19] [20].

Despite these fundamental differences, examples of convergent evolution are evident. The fungal XDR1 regulatory system shows functional analogy to the mammalian PXR pathway, though these transcription factors share no sequence homology [21]. Similarly, the CDCL toxin system in Bacteroidota has evolved a pore-forming mechanism strikingly similar to the eukaryotic complement membrane attack complex, despite originating from a completely different phylogenetic background [25]. These convergent solutions highlight the power of natural selection to arrive at similar mechanistic answers to the universal challenge of toxin defense.

The evolutionary trajectories of these systems also differ significantly. Prokaryotes primarily rely on horizontal gene transfer to acquire new resistance traits, allowing rapid adaptation but potentially costing more cellular resources to maintain numerous specific immunity proteins [24] [27]. Eukaryotes tend to employ gene duplication and regulatory network expansion, creating layered systems that can be fine-tuned to specific threats while minimizing fitness costs [19] [20]. This fundamental difference in evolutionary strategy has profound implications for addressing toxin resistance in clinical and agricultural settings.

Figure 2: Evolutionary pathways of toxin defense strategies. Prokaryotes rely on horizontal gene transfer and mobile genetic elements to disseminate toxin-immunity pairs, while eukaryotes utilize gene duplication and regulatory network expansion to create layered defense systems, with convergent evolution leading to similar solutions.

Applications and Future Directions

The comparative understanding of toxin resistance mechanisms has significant implications for addressing pressing challenges in medicine and agriculture. In antifungal drug development, targeting the interaction between transcription factors like ShXDR1 and mediator complexes represents a promising strategy for overcoming multidrug resistance in fungal pathogens [21]. The discovery of iKIX1, a compound that disrupts the PDR1-mediator interaction in yeast, provides a proof-of-concept for this approach [21].

In agriculture, understanding the transcriptional regulation of detoxification genes in insect pests enables the development of novel pest management strategies. RNA interference (RNAi) technology can be employed to silence specific resistance-related genes, potentially restoring insecticide sensitivity in resistant populations [19] [20]. Similarly, modulating the CncC/Keap1 pathway could alter the expression of multiple detoxification genes simultaneously, providing a broader approach to insecticide resistance management [19].

The discovery of complement-like killing mechanisms in bacteria opens new avenues for developing narrow-spectrum antimicrobials that target specific bacterial species while preserving beneficial microbiota [25]. As our understanding of these diverse defense mechanisms continues to grow, so too will our ability to manipulate them for human health and agricultural productivity.

The evolutionary arms race between organisms and toxins has driven the development of sophisticated resistance mechanisms. This comparative guide examines two fundamental processes underpinning resistance: horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which enables rapid dissemination of genetic traits across contemporary populations, and natural selection, which acts on vertical inheritance and mutation over generational timescales. While HGT dominates as the primary mechanism for rapid resistance acquisition in prokaryotes, particularly against antibiotics, eukaryotes rely more heavily on natural selection acting on existing genetic variation and rare beneficial mutations. Through analysis of experimental data and emerging research, we demonstrate how these distinct pathways shape resistance landscapes across the tree of life, with critical implications for antimicrobial development, cancer therapeutics, and managing treatment resistance.

The capacity to withstand toxic compounds represents a fundamental survival challenge that has shaped evolutionary pathways across all life forms. In prokaryotes, resistance mechanisms primarily emerge through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), the non-sexual movement of genetic information between organisms, enabling virtually instantaneous acquisition of resistance traits across species boundaries [28] [29]. This process stands in stark contrast to the slower, generational process of natural selection acting on random mutations and vertical inheritance—a mechanism that dominates in eukaryotic resistance evolution [30]. The distinction between these pathways has profound implications for how resistance develops and spreads in different biological contexts.

The clinical and ecological significance of understanding these mechanisms cannot be overstated. In prokaryotic systems, HGT facilitates the rapid spread of antibiotic resistance genes among bacterial pathogens, contributing to the global health crisis of multidrug-resistant infections [28] [31]. In eukaryotic systems, natural selection drives the emergence of treatment resistance in contexts ranging from cancer therapeutics to antifungal applications, though through fundamentally different genetic mechanisms [31]. This comparative analysis examines the genetic foundations, operational mechanisms, and experimental evidence for these distinct resistance pathways, providing researchers with a structured framework for understanding and investigating resistance evolution across biological systems.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: The Prokaryotic Paradigm

Mechanisms and Molecular Processes

Horizontal gene transfer encompasses three primary mechanisms that enable prokaryotes to acquire genetic material from contemporary organisms in their environment. Transformation involves the uptake and incorporation of exogenous DNA fragments from the environment, a process facilitated by competence factors that allow bacterial cells to bind and internalize extracellular DNA [32]. Naturally competent bacteria like Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Streptococcus pneumoniae exemplify this mechanism, which typically involves homologous recombination of DNA fragments approximately 10 genes in length [32].

Conjugation represents the most common form of HGT, particularly between distantly related bacterial species, involving direct cell-to-cell contact and transfer of mobile genetic elements [32] [31]. This process is mediated by conjugative plasmids, integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), and conjugative transposons that encode the necessary machinery for DNA transfer between cells. The clinical significance of conjugation is profound, as it enables cross-species transfer of antibiotic resistance genes, with certain plasmids capable of transferring across genera, phyla, and even domains [31].

Transduction involves the transfer of bacterial DNA via bacteriophages (bacterial viruses), which occasionally package host DNA instead of viral DNA during infection cycles [32] [29]. When these transducing particles infect new bacterial cells, they inject the previous host's DNA, which may then recombine into the recipient's genome. Both generalized transduction (where any bacterial DNA fragment can be transferred) and specialized transduction (where specific bacterial genes adjacent to prophage integration sites are transferred) contribute to this process [32].

Table 1: Primary Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer in Prokaryotes

| Mechanism | Genetic Material Transferred | Key Elements | Transfer Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformation | Environmental DNA fragments | Competence proteins, DNA uptake systems | Typically within same or closely related species |

| Conjugation | Plasmids, conjugative transposons | Conjugative pilus, transfer genes | Broad range, including distant species |

| Transduction | Bacterial DNA via viruses | Bacteriophages, pac sites | Usually within same bacterial species |

| Gene Transfer Agents | Random DNA fragments | Virus-like particles encoded by host | Primarily within alphaproteobacteria |

Mobile Genetic Elements as HGT Vehicles

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) serve as the primary vehicles for HGT, functioning as natural genetic engineering systems that facilitate the movement and reorganization of DNA within and between genomes. Plasmids are extrachromosomal DNA elements that replicate independently and frequently carry accessory genes conferring selective advantages, such as antibiotic resistance and toxin production [33] [31]. The ability of plasmids to transfer between bacteria via conjugation makes them particularly effective in spreading resistance traits through microbial populations.

Transposons (jumping genes) are DNA sequences that can change position within a genome, sometimes carrying additional genes such as those encoding antibiotic resistance [29]. Horizontal transposon transfer (HTT) represents a specialized form of HGT that enables these mobile elements to colonize new genomes, with DNA transposons and LTR retroelements being most likely to undergo HTT due to their stable double-stranded DNA intermediates [29]. Integrons are genetic systems that capture and express gene cassettes, frequently accumulating multiple antibiotic resistance genes in clinical isolates [31]. These platforms significantly contribute to the assembly of multidrug resistance clusters in pathogenic bacteria.

The mobilome—the collective mobile genetic elements within a genome—provides prokaryotes with access to a shared gene pool, enabling extremely rapid adaptation to selective pressures like antibiotic exposure. This dynamic genetic reservoir stands in stark contrast to the relatively static chromosomal background, highlighting the dual nature of prokaryotic genomes as both inherited and acquired genetic entities.

Natural Selection: The Eukaryotic Foundation

Vertical Inheritance and Mutation Accumulation

In contrast to prokaryotes, eukaryotic resistance primarily emerges through natural selection acting on genetic variation generated through vertical inheritance and mutation. The sexual reproduction cycle in eukaryotes provides a mechanism for generating genetic diversity through meiotic recombination and gamete fusion, creating novel genetic combinations upon which natural selection can act [31]. This process, while slower than HGT, enables the gradual accumulation of beneficial mutations that enhance resistance to toxins and other environmental stressors.

Eukaryotes employ sophisticated epigenetic modifications as rapid-response mechanisms to environmental challenges, including toxin exposure. These include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-mediated regulation that can alter gene expression patterns without changing the underlying DNA sequence [31]. While not permanent genetic changes, these epigenetic adjustments can provide provisional protection while slower genetic adaptations evolve through selection on random mutations.

The expansion of gene families through duplication and divergence represents another key mechanism by which eukaryotes evolve resistance through natural selection. Gene duplication creates genetic redundancy that allows one copy to maintain original function while others accumulate mutations that may confer novel protective functions [31]. This process has been instrumental in the evolution of detoxification systems like cytochrome P450 enzymes, which play crucial roles in metabolizing various toxins and drugs.

Limited Horizontal Gene Transfer in Eukaryotes

While HGT is less prevalent in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes, growing evidence indicates that it does occur and contributes to eukaryotic evolution, including resistance traits [30] [29]. Documented cases of HGT in eukaryotes include the transfer of mitochondrial genes between parasitic plants and their hosts [30], the acquisition of bacterial genes for toxin degradation in some arthropods [31], and the integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA into the genome of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) and other plants [30].

The barriers to HGT in eukaryotes include the nuclear envelope, which separates the genome from the cytoplasm; the presence of germline-soma separation in multicellular organisms, which requires foreign DNA to enter germ cells to be heritable; and RNA interference pathways that silence foreign genetic elements [30]. Despite these barriers, some eukaryotic lineages have experienced significant HGT, such as tardigrades, in which approximately 17.5% of genes originate from foreign sources like bacteria, fungi, and plants [31].

The functional domains of transferred genes in eukaryotes often involve toxin resistance and metabolic adaptation, suggesting that HGT may provide selective advantages similar to those in prokaryotes, albeit through different mechanistic pathways. The investigation of these rare transfer events provides valuable insights into the potential for engineering HGT-based solutions for eukaryotic disease management.

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Data and Evidence

Quantitative Resistance Patterns Across Organisms

Recent genomic studies reveal distinct patterns in how resistance genes are distributed and maintained across prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Analysis of 24,102 complete bacterial genomes shows that duplicated antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are highly enriched in bacteria isolated from humans and livestock—environments with high antibiotic exposure—with further enrichment in antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates [33]. This pattern demonstrates how HGT, combined with strong selection, rapidly amplifies resistance genes in prokaryotic populations facing toxin pressure.

In contrast, eukaryotic resistance typically emerges through the selection of pre-existing genetic variations or rare beneficial mutations. For instance, the Fhb7 resistance gene in wheat, which provides resistance to Fusarium head blight, originated from an HGT event between the Epichloë fungus and Thinopyrum elongatum, but this represents a rare exception rather than the norm [30]. Most eukaryotic resistance evolves through selection on standing variation or new mutations within the species' own gene pool.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Resistance Mechanisms in Prokaryotes vs. Eukaryotes

| Characteristic | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Horizontal Gene Transfer | Natural Selection on Mutations |

| Timescale | Immediate to days | Generational to evolutionary |

| Genetic Source | Global gene pool | Species gene pool |

| Key Elements | Plasmids, transposons, integrons | Gene duplications, regulatory changes |

| Spread Pattern | Epidemic, network-based | Clonal, tree-based |

| Environmental Response | Gene acquisition | Gene expression changes, epigenetics |

| Experimental Evidence | Duplicated ARGs in clinical isolates [33] | Fhb7 transfer in wheat [30] |

Molecular and Biochemical Distinctions

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic resistance systems show fundamental differences at the molecular level. Bacterial toxins used in interference competition are often encoded within gene cassettes on mobile elements and exhibit distinctive amino acid compositions, with over-representation of histidine and arginine compared to non-toxic secreted proteins [34]. Eukaryotic toxin resistance systems frequently involve enzyme families like cytochrome P450s and glutathione S-transferases that have expanded through gene duplication and divergence.

The two-component CDC-like (CDCL) toxins produced by Gram-negative Bacteroidota illustrate how prokaryotic systems employ horizontally transferred toxin genes in bacterial antagonism [25]. These CDCL genes are distributed on mobile genetic elements among gut microbiota species and function similarly to the mammalian complement membrane attack complex, representing an HGT-dependent armory system [25]. Eukaryotic systems lack such portable toxin arsenals, instead relying on immune recognition and programmed cell death pathways.

The empirical data reveal that HGT provides prokaryotes with a rapid-response capability to novel toxins, while eukaryotes depend on selection acting on existing genetic toolkits—a fundamental distinction with profound implications for clinical practice and resistance management.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Investigating HGT-mediated resistance typically involves experimental evolution studies where bacteria are exposed to sublethal antibiotic concentrations, followed by genomic analysis of evolved populations. One such protocol exposed E. coli strains containing a minimal transposon with a tetracycline resistance gene to 50 μg/mL tetracycline for 9 days, with control populations propagated without antibiotics [33]. Whole-genome sequencing of resistant colonies revealed tetA duplications through intragenomic transposition in selected populations, while control populations showed no such duplications.

A modified short-term protocol using wild-type E. coli K-12 MG1655 demonstrated that just one day (~10 bacterial generations) of tetracycline selection was sufficient to drive resistance gene duplications to observable frequencies across all replicate populations [33]. Replacement of the tetA gene with genes conferring resistance to spectinomycin, kanamycin, carbenicillin, and chloramphenicol yielded similar results, with antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) duplications observed in 8 out of 8 evolved populations across all four antibiotics [33].

For studying natural selection-based resistance in eukaryotes, mutation accumulation lines combined with whole-genome sequencing provide insights into the rate and spectrum of spontaneous mutations. These approaches typically involve propagating multiple independent lines through single-organism bottlenecks for hundreds of generations, followed by genomic sequencing to identify accumulated mutations and phenotypic assays to assess their functional consequences.

Detection and Analysis Methods

Bioinformatic detection of HGT events employs both parametric methods (identifying atypical sequence signatures like GC content, codon usage bias) and phylogenetic methods (identifying discrepancies between gene trees and species trees) [29]. The availability of thousands of complete bacterial genomes enables robust detection of recently transferred genes, particularly those associated with mobile genetic elements.

Shotgun metagenomics provides a powerful approach for identifying HGT events in complex microbial communities without cultivation. This method involves fragmenting and sequencing all DNA in a sample, then assembling contiguous regions and searching for phylogenetic mismatches that indicate horizontal transfer [29]. For eukaryotes, detecting HGT requires additional safeguards to exclude contamination and account of the complexity of eukaryotic genomes with abundant repeat-rich regions [30].

Functional validation of candidate resistance genes involves heterologous expression in model organisms followed by toxin sensitivity assays. For example, cloning putative resistance genes into susceptible strains and measuring changes in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) provides direct evidence of resistance function. For eukaryotic systems, RNA interference or CRISPR-based gene editing can establish whether candidate genes confer resistance through loss-of-function experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Resistance Mechanisms

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| PAT Database | Catalog of experimentally validated antimicrobial toxins | 441 toxins with delivery mechanisms [24] |

| Tn5 Transposase System | Experimental evolution of HGT | tetA-Tn5 transposition assay [33] |

| Long-read Sequencers | Resolving duplicated resistance genes | PacBio, Oxford Nanopore [33] |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | HGT mechanism analysis | Plasmids, conjugative transposons [31] |

| Antibiotic Selection Media | Experimental evolution | Tetracycline, carbenicillin [33] |

| Competent Bacterial Strains | Transformation studies | E. coli DH5α, MG1655 [33] [32] |

| Phage Lysates | Transduction experiments | P1, λ phage [32] |

| Metagenomic Datasets | Natural HGT detection | Earth Microbiome Project [24] |

The comparative analysis of horizontal gene transfer and natural selection as resistance mechanisms reveals a fundamental dichotomy in evolutionary strategy between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. HGT provides prokaryotes with a rapid-response system to immediately address novel toxin threats through gene acquisition from a global genetic commons. In contrast, eukaryotes primarily rely on natural selection acting on existing genetic variation, resulting in slower but potentially more stable resistance evolution.

These distinctions have profound implications for clinical practice and drug development. The HGT-driven spread of antibiotic resistance necessitates approaches that target the mobile genetic elements themselves, such as compounds that disrupt conjugation or plasmid maintenance. For eukaryotic resistance, as seen in cancer chemotherapy and antifungal treatments, combination therapies that target multiple pathways simultaneously may help overcome the slower but inevitable emergence of resistance through selection.

Future research directions should include developing HGT-inhibiting therapeutics that specifically target conjugation machinery or plasmid replication, thus preserving antibiotic efficacy. For eukaryotic systems, leveraging rare natural HGT events, such as the Fhb7 transfer in wheat, might inspire novel biotechnological approaches to engineer resistance in crops and animals. The continued development of databases like PAT (Prokaryotic Antimicrobial Toxin database) provides essential resources for tracking the evolution and spread of resistance elements across microbial ecosystems [24].

Understanding these complementary evolutionary pathways—horizontal gene transfer's rapid gene sharing versus natural selection's gradual optimization—provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for addressing the growing challenge of treatment resistance across medical, agricultural, and environmental contexts.

From Discovery to Therapy: Methodologies and Biomedical Applications

This guide provides an objective comparison of computational tools for molecular docking and genomic analysis, with experimental data framed within research on toxin resistance mechanisms across prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Molecular Docking Tools: Performance and Precision

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of computational drug design, simulating how small molecules (ligands) interact with biological targets like proteins. This is crucial for understanding toxin resistance mechanisms, as it can reveal how certain proteins neutralize toxic compounds or how mutations confer resistance [35].

Comparative Performance of Docking Methodologies

A 2025 comprehensive benchmark evaluated traditional and deep learning (DL)-based docking methods across multiple dimensions, including pose prediction accuracy and physical validity [36]. The results reveal a clear performance stratification.

Table 1: Performance Benchmark of Molecular Docking Tools (Success Rate %)

| Method Category | Specific Tool | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2 Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Combined Success (RMSD ≤ 2 Å & PB-Valid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Methods | Glide SP | Data Not Provided | >94% | Data Not Provided |

| Generative Diffusion Models | SurfDock | 91.76 (Astex) | 63.53 (Astex) | 61.18 (Astex) |

| DiffBindFR | 75.30 (Astex) | 46.73 (Astex) | 34.58 (PoseBusters) | |

| Regression-Based Models | KarmaDock, GAABind, QuickBind | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| Hybrid Methods | Interformer | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

Key Findings:

- Traditional methods like Glide SP consistently excel in producing physically plausible poses, with validity rates above 94% across diverse datasets [36].

- Generative diffusion models, such as SurfDock, achieve superior pose accuracy but often generate structures with steric clashes or incorrect bond lengths, leading to moderate combined success rates [36].

- Regression-based models frequently fail to produce physically valid poses and generally occupy the lowest performance tier [36].

Experimental Protocol for Docking Evaluation

The benchmark data in Table 1 was derived from a rigorous, multi-dataset evaluation protocol [36]:

- Datasets: The Astex diverse set (known complexes), the PoseBusters benchmark set (unseen complexes), and the DockGen dataset (novel protein binding pockets) were used to test generalization.

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Pose Accuracy: Measured by Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD). A prediction with RMSD ≤ 2 Å relative to the experimental structure is considered successful.

- Physical Validity: Assessed using the PoseBusters toolkit, which checks for chemical and geometric consistency, including bond lengths, angles, and absence of steric clashes.

- System Environment: Benchmarks were conducted in a controlled Docker environment restricted to a single CPU core and a maximum of 12GB memory to ensure a fair and reproducible evaluation [36].

Genomic Analysis Tools for Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics relies on efficient tools to query and analyze genomic intervals, which is fundamental for identifying genetic elements involved in toxin production and resistance across different species [37].

Benchmarking Genomic Interval Query Tools

A systematic evaluation of genomic interval query tools assessed their runtime performance and memory efficiency using simulated datasets of varying sizes [37].

Table 2: Benchmark of Genomic Interval Query Tools

| Tool | Core Data Structure | Indexing Required? | Data Sorting Required? | Supported Formats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEDTools | Hierarchical binning | No | No | BED, GFF, VCF |

| tabix | Binning & linear index | Yes | Yes | BED, GTF, VCF |

| BEDOPS | Flat interval set | No | Yes | BED (.starch) |

| GIGGLE | B+ tree | Yes | Yes | BED, VCF (.bgz) |

| bedtk | Implicit interval tree | No | No | BED (.gz) |

| gia | Flat interval set | No | No (for unsorted data) | BED (.gz, .bgz) |

Key Findings:

- Tools like BEDTools and bedtk offer flexibility as they do not require pre-sorted or pre-indexed data, making them suitable for rapid, ad-hoc analyses [37].

- tabix and GIGGLE, which require indexing, can provide faster query speeds on large, static datasets but incur an upfront computational cost [37].

- The benchmarking framework, segmeter, is publicly available, facilitating reproducibility and custom comparative analyses [37].

Application to Toxin Resistance Research

The curated computational toolkit enables a comparative assessment of toxin resistance mechanisms in prokaryotes versus eukaryotes. Key differences in toxin proteins can be leveraged to design selective inhibitors.

Curated Toxin Datasets for Robust Modeling

Research highlights the importance of using high-quality, segregated datasets for bacterial and animal toxins, as they possess intrinsic biophysical differences [34]:

- Amino Acid Composition: Animal toxins are significantly enriched in cysteine (which contributes to stability), while bacterial toxins show higher prevalence of histidine and arginine [34].

- Sequence Length: Animal toxins are, on average, significantly shorter than bacterial toxins [34].

- Isoelectric Point (pI): Bacterial toxin distributions are shifted toward acidic pI values, with about a third having pI below 5, potentially related to their mechanism of action in acidic endosomes [34].

Mixing these distinct toxin groups in bioinformatics models can introduce noise and compromise predictive performance. Therefore, using specialized, curated datasets is critical for reliability [34].

Workflow for Toxin Resistance Mechanism Investigation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow that integrates the discussed tools for studying toxin resistance.

This section details key databases, software, and computational resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Toxicology

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Toxin Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of protein-toxin complex structures for analysis and docking template [35]. |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Database | Expertly curated protein sequence and functional information. | Foundational resource for obtaining accurate sequences of toxins and resistance-related proteins [34]. |

| Curated Toxin Datasets | Dataset | Specialized collections of bacterial exotoxins and animal toxins. | Provides high-quality, non-redundant data for training predictive models and comparative studies [34]. |