Ensuring Data Integrity: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing robust quality control (QC) protocols in chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows.

Ensuring Data Integrity: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for implementing robust quality control (QC) protocols in chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges the gap between foundational QC principles and their specific application in studying drug-genome interactions. The content systematically guides the reader from establishing foundational knowledge and methodological applications to advanced troubleshooting and rigorous validation strategies. By synthesizing current best practices, regulatory considerations, and comparative analyses of NGS methods, this guide empowers scientists to generate high-quality, reproducible data crucial for target discovery, resistance mechanism identification, and biomarker development.

The Critical Role of Quality Control in Chemogenomic NGS

Defining Chemogenomic NGS and Its Unique QC Challenges

Chemogenomics is a strategic approach in drug discovery that involves the systematic screening of libraries of small molecules against families of biologically related drug targets (such as GPCRs, kinases, or proteases) to identify novel drugs and drug targets [1]. The ultimate goal is to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all potential therapeutic targets derived from the human genome [1].

Chemogenomic NGS applies next-generation sequencing to this paradigm, expediting the discovery of therapeutically relevant targets from complex phenotypic screens [2]. This powerful combination allows researchers to analyze the vast interactions between chemical compounds and the genome on an unprecedented scale. However, the fusion of these fields introduces unique quality control (QC) challenges that are critical for generating reliable, actionable data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What exactly is a "chemogenomic NGS library" and how does it differ from a standard NGS library? A chemogenomic NGS library is prepared from biological samples that have been perturbed by small molecule compounds from a targeted chemical library [2] [1]. Unlike standard NGS libraries which often sequence a static genome or transcriptome, chemogenomic libraries are designed to capture the dynamic molecular changes—in genes, transcripts, or epigenetic marks—induced by these chemical probes. The uniqueness lies in the experimental design and the subsequent need to accurately link observed phenotypic changes to specific molecular targets.

2. Why is library quantification so critical in chemogenomic NGS, and which method is best? Accurate quantification is the key to a successful sequencing run because it directly impacts cluster generation on the flow cell [3] [4]. Underestimation of amplifiable molecules leads to mixed signals and poor data quality, while overestimation results in poor cluster yield and wasted sequencing capacity [3]. For most applications, qPCR-based quantification is recommended as it selectively quantifies only DNA fragments that have the required adapter sequences on both ends and are therefore capable of amplification during sequencing [3] [4].

3. What are the most common sources of bias in a chemogenomic NGS experiment? Bias can be introduced at multiple points:

- Library Preparation: Protocols can introduce biases in gene body coverage evenness, GC content, and insert size [5].

- Compound Interference: The small molecules used to perturb the biological system can sometimes interfere with enzymatic reactions during library construction.

- Quantification Inaccuracy: Using non-specific quantification methods (like spectrophotometry) that measure total nucleic acids instead of just adapter-ligated, amplifiable fragments can lead to loading inaccuracies [3] [4].

4. My chemogenomic screen yielded a high number of unexplained hits. Could this be a QC issue? Potentially, yes. Inconsistent library quality or concentration across different compound screens in a panel can create false positives or negatives. A common culprit is the use of non-specific quantification methods, which provide an inaccurate measure of usable library fragments. This can cause some samples to be under-sequenced (missing real hits) while others are over-sequenced (increasing background noise). Implementing qPCR or digital PCR for precise, amplifiable-specific quantification is crucial for normalizing sequencing power across all samples in a screen [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Library Diversity & High Duplicate Rates

Potential Cause: Inaccurate library quantification leading to over-clustering [3]. When too many amplifiable library molecules are loaded onto the flow cell, multiple identical molecules form clusters in close proximity, which the sequencer cannot resolve as distinct reads.

Solution:

- Validate Quantification Method: Switch from fluorometric methods to qPCR for accurate quantification of adapter-ligated, amplifiable fragments [3] [4].

- Titrate Load: Perform a loading calibration experiment using qPCR-quantified libraries to determine the optimal loading concentration for your specific system.

Problem 2: High Adapter-Dimer Formation

Potential Cause: Inefficient purification after adapter ligation during library prep, leaving an excess of free adapters that ligate to each other.

Solution:

- Improve Size Selection: Use bead-based cleanups with optimized sample-to-bead ratios to remove short fragments effectively.

- Implement Rigorous QC: Use a microfluidics-based electrophoresis system (e.g., Bioanalyzer or TapeStation) before sequencing to visually inspect the library profile for a clean peak and the presence of a low-molecular-weight adapter-dimer peak [3] [4]. Do not sequence if adapter-dimer content is high.

Problem 3: Inconsistent Results Across Multi-Plate Chemogenomic Screens

Potential Cause: Inter-plate variability in library quality and concentration, making it difficult to compare phenotypic outcomes fairly.

Solution:

- Standardize QC Pipeline: Implement a uniform, sensitive QC protocol for every library in the screen. The table below compares common methods.

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Library QC and Quantification Methods

| Method | What It Measures | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Recommendation for Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Spectrophotometry | Total nucleic acid concentration | Fast, easy | Cannot distinguish adapter-ligated fragments; inaccurate [4] | Not Recommended [4] |

| Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | Total dsDNA or ssDNA concentration | More specific for DNA than UV | Cannot distinguish adapter-ligated fragments [3] [4] | Use for rough pre-qPCR assessment |

| qPCR | Concentration of amplifiable, adapter-ligated fragments | High accuracy; specific to sequencer-compatible molecules [3] [4] | Requires standard curve | Highly Recommended [3] [4] |

| Digital PCR | Absolute concentration of amplifiable, adapter-ligated fragments | Ultimate accuracy; no standard curve needed; single-molecule sensitivity [3] | Expensive equipment; not yet widespread [3] | Gold standard for critical assays |

| Electropherogram (e.g., Bioanalyzer) | Library fragment size distribution and qualitative assessment | Excellent for visualizing adapter-dimer contamination and size profile [3] [4] | Not recommended as a primary quantification method [4] | Essential for quality assessment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Chemogenomic NGS Library QC

| Item | Function | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Chemical Library | Small molecule probes | A collection of compounds designed to interact with specific protein target families (e.g., kinases), used to perturb the biological system [2] [1]. |

| qPCR Quantification Kit | Library quantification | Selectively amplifies and quantifies only DNA fragments that have the required sequencing adapters, ensuring accurate loading [3]. |

| Microfluidics-based Electrophoresis Kit | Library quality control | Provides a sensitive, automated assessment of library average fragment size and distribution, and detects contaminants like adapter dimers [3]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Library purification | Magnetic beads used to purify and select for DNA fragments within a desired size range, removing unwanted short fragments and reaction components. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Library construction | A ready-to-use kit containing the necessary enzymes and buffers for the end-to-end process of converting sample DNA or RNA into a sequencer-compatible library [6]. |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

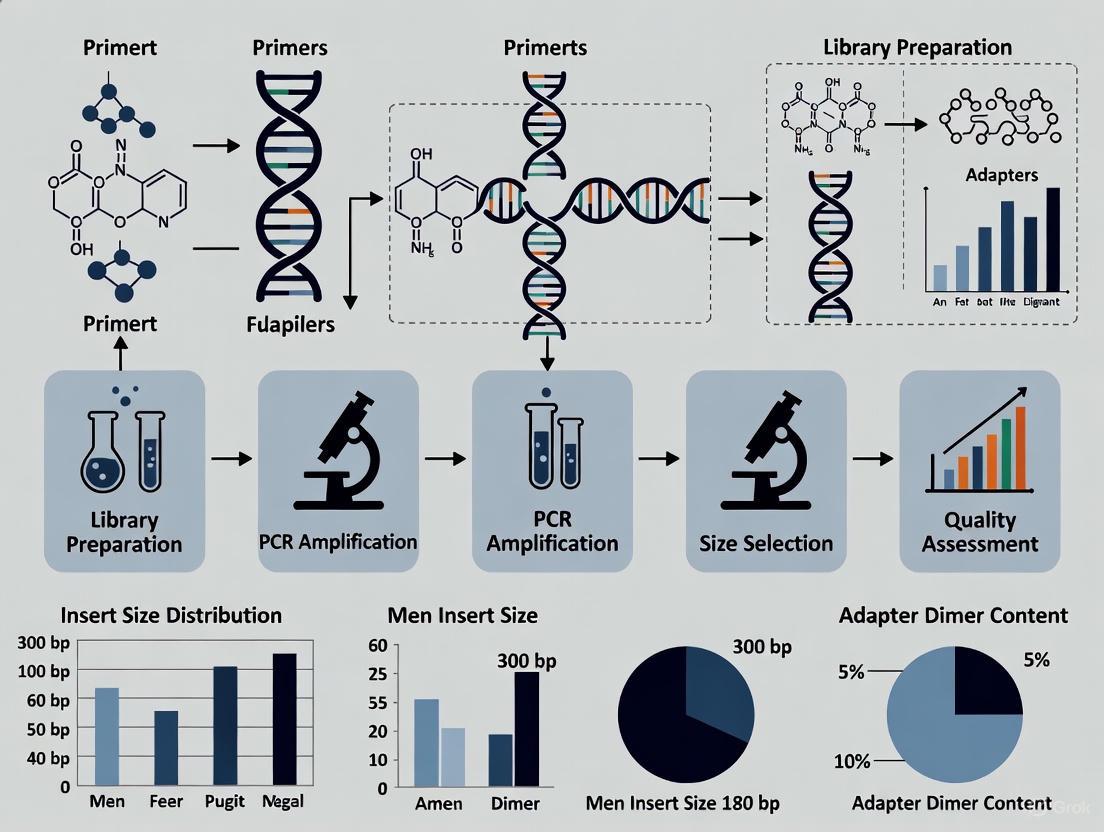

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for a reverse chemogenomics approach, a common strategy in the field, and highlights the critical QC checkpoints.

Detailed Protocol for Key QC Steps:

1. Nucleic Acid Extraction and QC (Post-Step D)

- Methodology: Extract DNA/RNA using standard kits appropriate for your sample type (e.g., cell lines, tissues).

- Purity Check: Use UV spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) to assess protein or solvent contamination. Acceptable 260/280 ratios are ~1.8 for DNA and ~2.0 for RNA.

- Quantity Check: Use fluorometry (e.g., Qubit with dsDNA HS or RNA HS assay) for accurate concentration measurement [6].

2. Library Profiling (Post-Step E)

- Methodology: Use a microfluidics-based electrophoresis instrument (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer or Fragment Analyzer).

- Procedure: Load 1 µL of the undiluted library. The instrument will provide an electropherogram and data table.

- Interpretation: Look for a tight, single peak in the expected size range (e.g., 300-500 bp for DNA-seq). A clean library will have no or a very small peak below 150 bp, indicating minimal adapter-dimer contamination [3].

3. Quantification of Amplifiable Fragments (Critical QC Step F)

- Methodology: Use a qPCR-based kit designed for NGS library quantification.

- Procedure:

- Dilute the library appropriately (e.g., 1:10,000 to 1:100,000) in a low-EDTA TE buffer.

- Prepare a standard curve using the provided standards.

- Run the qPCR reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Calculation: The qPCR software will provide a concentration (in nM) based on the standard curve. This is the concentration you will use to dilute your library for sequencing [3] [4].

In the high-stakes field of chemogenomic NGS library research, quality control is the fundamental barrier between reliable discovery and costly misdirection. For researchers and drug development professionals, robust QC protocols ensure that the data underlying critical decisions is complete, accurate, and trustworthy. Neglecting data integrity can invalidate years of research, lead to regulatory penalties, and ultimately compromise patient safety [7]. This technical support center provides the foundational principles and practical tools to embed uncompromising quality into every step of your NGS workflow.

The Data Integrity Foundation: ALCOA+

Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA enforce strict data integrity standards, often defined by the ALCOA+ framework. Adherence to these principles is non-negotiable for GMP compliance and regulatory audits [8].

ALCOA+ Principles for QC in NGS Research

| Principle | Description | Application in NGS Library Prep |

|---|---|---|

| Attributable | Clearly record who did what and when. | Electronic signatures in LIMS, user-specific login for instruments. |

| Legible | Ensure all data is readable for its entire lifecycle. | Permanent, secure data storage; no handwritten notes as primary records. |

| Contemporaneous | Document at the time of the activity. | Direct data capture from instruments; use of Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELN). |

| Original | Maintain original records or certified copies. | Storage of raw sequencing data files; certified copies of analysis reports. |

| Accurate | No errors or undocumented edits. | Automated data capture; audit trails that log all changes. |

| + Complete | Capture all data including deviations and re-tests. | Documenting all QC runs, including failures and repeated experiments. |

| + Consistent | Follow chronological order and standardized formats. | Using standardized SOPs and data formats for all library preps. |

| + Enduring | Protect data from loss or damage. | Secure, backed-up, and validated data storage systems. |

| + Available | Make data accessible for review or audit. | Data archiving in searchable, retrievable formats for the required lifetime. |

NGS Library Preparation: Market and Technology Trends

Understanding the evolving landscape of tools and technologies is crucial for selecting the right QC strategies. The market is rapidly advancing towards automation and higher throughput.

Global NGS Library Preparation Market Overview

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Market Size in 2025 | USD 2.07 Billion [9] |

| Market Size in 2026 | USD 2.34 Billion [9] |

| Forecasted Market Size by 2034 | USD 6.44 Billion [9] |

| CAGR (2025-2034) | 13.47% [9] |

| Dominating Region (2024) | North America (44% share) [9] |

| Fastest Growing Region | Asia Pacific [9] |

| Dominating Product Type | Library Preparation Kits (50% share in 2024) [9] |

| Fastest Growing Product Type | Automation & Library Prep Instruments (13% CAGR) [9] |

Key Technological Shifts Influencing QC [9]:

- Automation of Workflows: Reduces manual intervention, increases throughput and reproducibility.

- Integration of Microfluidics Technology: Enables precise microscale control of samples and reagents.

- Advancement in Single-Cell and Low-Input Kits: Allows high-quality sequencing from minimal DNA/RNA, expanding applications in oncology and personalized medicine.

Troubleshooting QC Failures in NGS Library Prep

A structured approach to troubleshooting is essential. Do not automatically re-run or recalibrate; instead, follow a logical process to identify the root cause [10].

Troubleshooting QC Failures Flowchart

Systematic Error Investigation Protocol

When initial checks don't resolve the issue, a detailed investigation is required.

Methodology:

- Review Instrument Performance:

- Check calibration records and status.

- Verify that all scheduled maintenance has been performed and documented.

- Look for any unusual patterns in internal instrument QC data.

- Audit Reagents and Consumables:

- Confirm that all reagents are within their expiration dates.

- Document the lot numbers of all reagents used in the failed QC run.

- Check for any prior issues associated with specific reagent lots.

- Evaluate QC Materials:

- Verify the preparation and storage of the QC samples themselves.

- Ensure the QC materials are appropriate for the test and have not degraded.

- Analyze the Failure Pattern:

- Determine if the error is systematic (affecting all samples in a predictable way, often due to calibration or reagent issues) or random (sporadic, often due to pipetting error or sample-specific problems) [10].

- Apply Westgard Rules or other multi-rule QC procedures to interpret control data and identify the type of error [11].

Post-Failure Action Protocol

Once the root cause is identified and corrected, specific actions must be taken.

Methodology:

- Assay Correction: Perform necessary actions such as recalibration, reagent replacement, or instrument maintenance.

- Re-run Validation: After correction, re-run the failed QC sample to confirm the process is back in control.

- Patient/Result Impact Assessment: Crucially, evaluate all patient or research sample data generated since the last acceptable QC. This data may need to be invalidated and the samples re-run [10].

- Documentation: Record the failure, the investigation process, the root cause, corrective actions taken, and the impact on sample results in the laboratory's deviation management system.

Implementing a Risk-Based QC Strategy with Westgard Rules

Applying the correct QC rules based on the performance of your method is a best practice that moves beyond one-size-fits-all compliance to true quality assurance [11].

Risk-Based QC Strategy Selection

Sigma-Metric Calculation Protocol

The Sigma-metric is a powerful tool for quantifying the performance of your testing process.

Methodology:

- Define the Quality Requirement (TEa): Establish the total allowable error (TEa) for your NGS assay. This can be derived from:

- CLIA proficiency testing criteria.

- Clinical decision intervals based on physician input.

- Biological variation data [11].

- Determine Method Bias: Calculate the systematic error of your method compared to a reference method or peer group performance in a proficiency testing scheme. Bias (%) = (Your Method's Mean - Reference Mean) / Reference Mean * 100.

- Determine Method Imprecision (CV): Calculate the coefficient of variation of your method from internal QC results. CV (%) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100.

- Calculate Sigma: Sigma = (TEa - |Bias|) / CV [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries [9]

| Item | Function in NGS Library Prep |

|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Provides all necessary enzymes, buffers, and master mixes for end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification in a standardized, optimized format. |

| Automated Library Prep Instruments | Reduces manual intervention and human error, enabling high-throughput, reproducible processing of hundreds of samples. |

| Single-Cell/Low-Input Kits | Allows for the generation of sequencing libraries from minimal starting material, crucial for rare cell populations or limited clinical samples. |

| Lyophilized (Dry) Kits | Removes cold-chain shipping and storage constraints, improving reagent stability and accessibility in labs with limited freezer capacity. |

| Platform-Specific Kits | Kits optimized for compatibility with major sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina, Oxford Nanopore), ensuring optimal performance and data output. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Integrity and Compliance

Q1: What are the real-world consequences of poor data integrity in a research lab? The consequences are severe and multifaceted. They include regulatory penalties (FDA warning letters, fines, lab shutdowns), loss of research credibility, invalidation of clinical trials, and most critically, compromised patient safety if erroneous data leads to misdiagnosis or unsafe therapeutics [7]. In fiscal year 2023, the FDA issued 180 warning letters, with a significant portion involving data integrity issues [7].

Q2: What is the difference between compliance and quality? Compliance means meeting the minimum regulatory standards—it's retrospective and about proving what was done. Quality is proactive; it's about ensuring processes are capable, controlled, and consistently produce reliable results. You can be compliant without having high quality, but you cannot have sustainable quality without compliance [12].

QC Protocols and Troubleshooting

Q3: What is the most common mistake labs make when QC fails? The most common mistake is to automatically re-run the controls or recalibrate without first performing a structured investigation to find the root cause. This can mask underlying problems with instruments, reagents, or processes, allowing them to persist and affect future results [10].

Q4: How do I choose the right QC rules for my NGS assay? Avoid a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, calculate the Sigma-metric for your assay. Use simple single rules (e.g., 1:3s) for high Sigma performance (≥5.5) and multi-rules (e.g., 1:3s/2:2s/R:4s) for methods with moderate to low Sigma performance (<5.5) to increase error detection [11].

Technology and Market

Q5: Is automating NGS library preparation worth the investment? For labs focused on scalability, reproducibility, and minimizing human error, yes. The automation segment is the fastest-growing product type in the NGS library prep market (CAGR of 13%). Automation increases throughput, standardizes workflows, and frees up highly skilled personnel for data analysis and other complex tasks [9].

Q6: What are the emerging trends in NGS library preparation? Key trends include the move towards automation, the integration of microfluidics for precise miniaturization of reactions, and the development of advanced kits for single-cell and low-input samples, which are expanding applications in oncology and personalized medicine [9].

A robust Quality Management System (QMS) is foundational for any Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) laboratory, ensuring the generation of reliable, accurate, and reproducible data. For chemogenomic research, where NGS libraries are used to explore compound-genome interactions, a QMS directly impacts the validity of scientific conclusions and drug development decisions. Adherence to established QMS standards, such as ISO 17025, provides a framework for laboratories to demonstrate their technical competence and the validity of their results [13]. This system encompasses all stages of the NGS workflow, from sample reception to data reporting, and is critical for meeting the rigorous demands of regulatory compliance and high-quality scientific research.

Core Components of a QMS for NGS

A comprehensive QMS for NGS laboratories is built on several interconnected pillars. The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and relationships between these core components.

Personnel and Training

Laboratory personnel must be competent, impartial, and have the appropriate education, training, and skills for their assigned activities [13]. The laboratory must maintain records of all personnel's competency, including the requirements for each position and the qualifications fulfilling those requirements. For NGS laboratories, this includes specific training on sequencing platforms, library preparation protocols, and bioinformatics analysis. A key QMS requirement is the clear definition of roles and responsibilities for all staff, with access to systems restricted based on user-level controls to ensure data integrity [13].

Equipment and Infrastructure Management

NGS relies on sophisticated instrumentation, from sequencers to bioinformatics servers. The QMS must ensure all equipment is suitable for its purpose and properly maintained.

- Calibration and Maintenance: Equipment requires regular calibration and maintenance, with records retained for each piece of equipment, including a unique ID, calibration dates, and service history [13]. Equipment marked for repair should not be used for generating results.

- Environmental Monitoring: Laboratory conditions must not compromise the validity of results. This includes monitoring and recording environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity, which is critical for sensitive NGS reactions and server hardware [13] [14].

- Infrastructure for Bioinformatics: Local bioinformatics platforms require robust hardware. The choice between a high-performance server or a multi-node computer cluster should be based on local clinical analysis needs, report turnaround times, and sample volume [14]. A dedicated server room with an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) is recommended for stability [14].

Process Control and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Every critical step in the NGS workflow must be governed by a detailed Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). SOPs ensure consistency and reproducibility, which are vital for chemogenomic studies where experimental conditions must be tightly controlled.

Data Management and Security

Data integrity and security are paramount in clinical NGS. The QMS must enforce strict data handling protocols.

- Data Confidentiality: The laboratory must ensure the confidentiality of all client and patient information [13]. This is often managed through role-based access controls within laboratory information systems.

- Data Storage and Backup: NGS data storage must be planned for the long term. It is recommended that original data backups be stored for at least 15 years [14]. A multi-layered backup strategy (e.g., Grandfather-Father-Son) should be implemented, and data integrity should be verified using checksum tools like SHA-256 [14].

- Audit Trails: The QMS must include an audit trail system that logs all changes to data, allowing for the tracking of any modifications, who made them, and when [13].

Documentation and Record Control

A QMS runs on its documentation. This includes the controlled management of SOPs, forms, and results. All testing and calibration activities must be recorded in a way that allows for full traceability from the final result back to the original sample [13].

Implementing QMS Across the NGS Workflow

Quality control must be integrated into every stage of the NGS process. The following workflow diagram maps key QMS activities and QC checkpoints to the primary NGS steps.

Nucleic Acid Extraction and QC

The first critical QC checkpoint occurs after nucleic acid extraction. For DNA intended for NGS, the following quality parameters are essential [15]:

- Purity: Assessed by A260/A280 ratio, which should be between 1.6 and 2.2.

- Quantity: Measured by fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for greater accuracy than UV spectrophotometry.

- Integrity: Checked by gel electrophoresis to confirm the DNA is high molecular weight and not degraded.

Extracted DNA should be stored appropriately: 4°C for 4 weeks, -20°C for 1 year, or -80°C for long-term storage (up to 7 years), with fewer than 3 freeze-thaw cycles [15].

Library Preparation and QC

Library construction is a complex step where quality control is vital. Key QMS considerations include [15]:

- Establishing a Validated Protocol: The laboratory must determine the minimum input DNA required for a reliable library (e.g., 200 ng for hybrid capture, 10 ng for amplicon-based approaches) and validate all reagents.

- Use of Controls: Each library preparation batch should include a blank negative control and a positive control (e.g., a commercial reference standard or a previously validated sample) to monitor for contamination and assess batch-to-batch reproducibility.

- Library QC: The final library must be quantified and its fragment size distribution analyzed (e.g., via Bioanalyzer) before sequencing.

Sequencing Run and QC

During the sequencing run, several quality metrics are monitored to assess performance. Key metrics include [15]:

- Q30 Score: The percentage of bases with a base call accuracy of 99.9% or higher. A common threshold is ≥70%.

- Cluster Density: Must be within the optimal range specified by the sequencer manufacturer.

- Error Rates and Intensity: Monitored in real-time on some platforms.

- Instrument and Reagent Monitoring: It is recommended to use standard品libraries at fixed intervals or with new reagent batches to monitor the stability of the sequencer and reagents over time [15].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Data Management

The bioinformatic pipeline is a critical part of the NGS workflow and must be rigorously controlled.

- Pipeline Validation: The entire analysis流程, from raw data (FASTQ) to variant calls (VCF), must be validated for accuracy and precision using established reference materials [14].

- Data Storage and Naming: Files should follow a standard naming convention including sample ID, date, and data type. A structured directory system is mandatory for organization [14]. FASTQ files are recommended to be stored for at least 5 years, while原始数据备份 should be kept for 15 years or more [14].

- Data Security: Data should be encrypted both in transit and at rest using Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Access should be governed by a "least privilege" model, and data should be de-identified to protect patient privacy [14].

Troubleshooting Common NGS Issues within a QMS Framework

When problems arise, a QMS provides a structured approach for investigation and resolution, known as Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA).

FAQ: Frequently Asked Troubleshooting Questions

Q1: Our sequencing run yield is low. What are the primary causes and how do we investigate? A: A low yield can stem from multiple sources. Follow a systematic investigation:

- Library QC: Re-check the library concentration and size profile. A poorly constructed library is a common cause.

- Cluster Generation: Verify that the cluster generation step on the flow cell was successful. Check for optimal cluster density.

- Sequencing Reagents: Ensure reagents were loaded correctly, are within expiration dates, and were handled properly.

- Image Analysis: Check the instrument's real-time analysis reports for any errors in fluorescence detection or base calling. A documented investigation using this checklist helps identify the root cause.

Q2: We are observing a high rate of duplicate reads in our data. What does this indicate and how can it be mitigated? A: A high duplication rate often indicates a lack of library complexity, meaning there was insufficient starting material or the amplification during library prep was excessive.

- Mitigation: Optimize the input DNA quantity to the validated level. If working with limited DNA, use library prep kits designed for low input to reduce PCR cycles. Ensure accurate quantification of the library before loading onto the sequencer to avoid overloading the flow cell.

Q3: Our positive control is failing in the library prep batch. What is the immediate action and long-term solution? A: This is a critical QC failure.

- Immediate Action: Do not process patient or research samples from the failed batch. Initiate a non-conformance report. Repeat the library preparation for the control and a test sample if possible.

- Long-Term Solution (CAPA): Investigate root causes: Were reagents stored and handled correctly? Was the protocol followed exactly? Has the control material degraded? Validate new lots of critical reagents. Retrain staff if a procedural error is identified. This CAPA process is a core tenet of QMS.

Q4: The instrument reports a fluidics or initialization error during a run. What are the first steps? A: As per manufacturer guidelines, initial steps often include [16]:

- Check Consumables: Confirm that all solutions (e.g., wash buffers) are present in sufficient volumes and that bottles are properly seated.

- Restart the Process: Soft-restart the initialization or calibration process. Power cycling the instrument and associated server can resolve connectivity or software glitches [16].

- Inspect for Physical Issues: Check for loose cables, chip clamps not being fully closed, or visible leaks or bubbles in the fluidics system [16]. If simple checks fail, contact technical support and document the issue and all actions taken in the equipment log.

Essential Reagents and Materials for Quality-Assured NGS

The following table details key reagents and materials used in NGS workflows, along with their critical quality attributes and functions from a QMS perspective.

Research Reagent Solutions for NGS

| Item | Function in NGS Workflow | Key Quality Attributes & QMS Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation and purification of DNA/RNA from sample types (tissue, blood, cells). | Purity and Yield: Validated for specific sample types. Inhibitor Removal: Critical for downstream PCR efficiency. Traceability: Lot number must be recorded. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and amplification of DNA/RNA to create sequencer-compatible libraries. | Conversion Efficiency: Ratio of input DNA to final library. Bias: Representation of original genome. Validation: Kit must be fully validated for its intended use (e.g., whole genome, targeted). |

| Hybridization Capture Probes | For targeted sequencing, these probes (e.g., biotinylated oligonucleotides) enrich specific genomic regions of interest. | Specificity: Ability to bind intended targets with minimal off-target capture. Coverage Uniformity: Evenness of sequencing depth across targets. Lot-to-Lot Consistency. |

| Sequencing Primers & Adapters | Universal and index adapter sequences are essential for proper cluster amplification on the flow cell and sample multiplexing [17]. | Sequence Fidelity: Oligos must have the correct sequence. Purity: Free from truncated products or contaminants. Compatibility: Must match the sequencing platform and library prep kit. |

| Control Materials | Used for quality control and validation. Includes positive controls (e.g., reference standards) and negative controls (e.g., blank, non-template control). | Characterization: Well-defined variant spectrum (for positive controls). Stability: Must be stable over time. Commutable: Should behave like a real patient sample. QMS Use: Essential for monitoring process stability [15]. |

| Quantitation Kits | Fluorometric-based quantification of DNA, RNA, and final libraries (e.g., Qubit assays). | Specificity: Ability to distinguish DNA from RNA or single vs. double-stranded DNA. Accuracy and Precision: Compared to a standard curve. Dynamic Range: Must cover expected sample concentrations. |

Quality Evaluation and Continuous Improvement

A QMS is not static; it requires ongoing evaluation and improvement.

- Internal Audits: Regular internal audits must be conducted to assess compliance with the QMS and identify areas for improvement.

- External Quality Assessment (EQA)/Proficiency Testing (PT): Laboratories should participate in EQA/PT programs, such as those organized by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) or national health authorities, at least annually or biennially [15]. A failed EQA must trigger a thorough investigation and CAPA.

- Management Review: Laboratory management must periodically review the QMS, including audit results, EQA outcomes, customer feedback, and non-conformities, to ensure its continuing suitability, adequacy, and effectiveness.

By implementing and adhering to these core principles, an NGS laboratory can build a culture of quality that ensures the reliability of its data, which is the ultimate foundation for robust chemogenomic research and confident drug development.

For clinical laboratories in the United States, the primary regulatory framework is established by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 [18]. CLIA regulations apply to all facilities that test human specimens for health assessment, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of disease [18]. The program is jointly administered by three federal agencies: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each with distinct responsibilities [19] [18].

A significant recent development occurred on March 31, 2025, when a U.S. District Court vacated the FDA's Final Rule on Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs) [20] [21]. This ruling concluded that LDTs constitute professional services rather than manufactured devices, placing them outside FDA's regulatory jurisdiction under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [21]. Consequently, CLIA remains the principal regulatory framework for laboratories developing and performing their own tests, including chemogenomic NGS libraries for clinical use [20].

Agency Roles and Responsibilities

Table: CLIA Program Responsibilities by Agency

| Agency | Primary Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) | Issues laboratory certificates, collects user fees, conducts inspections, enforces regulatory compliance, approves accreditation organizations [19]. |

| Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Categorizes tests based on complexity, reviews requests for CLIA waivers, develops rules for CLIA complexity categorization [19]. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Provides analysis, research, and technical assistance; develops technical standards and laboratory practice guidelines; monitors proficiency testing practices [19] [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What type of CLIA certificate does our lab need for NGS-based testing?

All laboratories performing non-waived testing on human specimens must have an appropriate CLIA certificate before accepting samples [19]. For NGS-based tests, which are classified as high-complexity, your laboratory typically needs a Certificate of Compliance or Certificate of Accreditation [22]. A Certificate of Compliance is issued after a successful state survey, while a Certificate of Accreditation is granted to laboratories accredited by a CMS-approved organization like the College of American Pathologists (CAP) [22].

We perform both RUO and clinical NGS. How does the recent LDT ruling affect us?

The March 2025 court decision vacating the FDA's LDT Rule means that laboratories offering LDTs are no longer subject to FDA medical device regulations for those tests [20] [21]. This means for your clinical LDTs:

- No FDA premarket review is required

- Test registration and listing with the FDA is not mandatory

- FDA quality system regulations do not apply

- Focus returns to compliance with CLIA requirements for high-complexity testing [20]

Your Research Use Only (RUO) tests remain outside CLIA jurisdiction as long as no patient-specific results are reported for clinical decision-making [18].

What is the most common reason for NGS library preparation failure?

The most common points of failure in NGS library preparation include:

- Insufficient or degraded input DNA/RNA: Starting material with low quantity, purity, or integrity produces poor libraries [23]

- Inefficient library construction: Characterized by a low percentage of fragments with correct adapters, leading to decreased data output and increased chimeric fragments [24]

- Excessive PCR amplification bias: Over-amplification introduces duplicates and uneven coverage [24]

Our NGS results are inconsistent across runs. Where should we look?

Inconsistent results typically stem from pre-analytical or analytical variables:

- Review nucleic acid quality control metrics: Ensure consistent DNA/RNA quantity, purity (A260/280 ratios), and integrity (intact bands on gel) [23]

- Standardize library preparation protocols: Implement calibrated pipetting, consistent reagent lots, and standardized fragmentation methods [25]

- Enhance personnel competency assessments: Ensure all staff demonstrate semiannual competency in all testing phases [26]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Library Complexity in NGS Libraries

Potential Causes and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Poor NGS Library Complexity

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High PCR duplicate rates, uneven coverage [24] | Insufficient starting material | Increase input DNA/RNA within kit specifications; use specialized low-input protocols [24] |

| Over-amplification during PCR | Optimize PCR cycle number; use high-fidelity polymerases that minimize bias [24] | |

| DNA degradation | Verify DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis; use fresh, properly stored samples [23] | |

| Low library yield with good input DNA [24] | Inefficient adapter ligation | Verify A-tailing efficiency; use fresh ligation reagents; optimize adapter concentration [24] |

| Size selection too stringent | Widen size selection range; verify fragment size distribution pre- and post-cleanup [24] |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Library QC Assessment

- Quantity Assessment: Using a DNA binding dye (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay), measure library concentration. Ensure values exceed minimum threshold (typically > 10 nM) [23]

- Fragment Size Analysis: Using automated electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation), verify library fragment distribution meets platform specifications (e.g., 350-430 bp for Illumina) [23]

- Adapter Validation: Confirm successful adapter ligation through qPCR with adapter-specific primers if needed [25]

- Functional QC: For clinical tests, include positive control samples with known variants to confirm library functionality [26]

Problem: CLIA Compliance Issues for NGS Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions

Table: Addressing Common CLIA Compliance Gaps

| Compliance Area | Common Deficiencies | Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Test Validation | Incomplete verification of performance specifications [26] | Document accuracy, precision, reportable range, and reference ranges using ≥20 specimens spanning reportable range [26] |

| Quality Control | Inadequate daily QC procedures [26] | Establish and document daily QC with at least two levels of controls; define explicit acceptance criteria [26] |

| Proficiency Testing | Failure to enroll in approved PT programs [20] | Enroll in CMS-approved PT programs for each analyte; investigate and document corrective actions for unsatisfactory results [20] |

| Personnel Competency | Incomplete competency assessment documentation [26] | Implement semiannual (first year) then annual assessments for all testing personnel across all 6 CLIA-required components [26] |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Method Verification for Clinical NGS Assays

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare results from 20-30 clinical samples with a validated reference method or certified reference materials [26]

- Precision Evaluation: Perform within-run and day-to-day replication (minimum 20 replicates each) to determine standard deviation and CV [26]

- Reportable Range Verification: Establish the range of reliable results using samples spanning clinical decision points [26]

- Reference Range Determination: Establish normal values for your laboratory's patient population using appropriate statistical methods [26]

- Documentation: Compile comprehensive verification report signed and dated by the Laboratory Director [26]

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

NGS Library Preparation Quality Control Protocol

Purpose: To ensure consistent production of high-quality sequencing libraries for chemogenomic applications

Reagents and Equipment:

- Extracted genomic DNA/RNA (meeting QC specifications)

- Library preparation kit (e.g., Illumina, Thermo Fisher)

- Magnetic bead-based cleanup reagents

- DNA binding dye (Qubit assay or equivalent)

- Automated electrophoresis system (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation)

- Real-time PCR instrument (for quantification)

- Adapter-specific primers (if performing qPCR QC)

Procedure:

- Input Material QC:

- Quantify nucleic acids using fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit)

- Assess purity via spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio: 1.8-2.0)

- Verify integrity via gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis (DNA Integrity Number >7 for DNA; RIN >8 for RNA) [23]

- Acceptance Criteria: DNA concentration ≥15 ng/μL, no degradation, minimal contamination

Library Construction:

- Fragment DNA to target size (e.g., 200-500bp) via acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation

- Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation according to manufacturer protocols

- Clean up using magnetic bead-based purification (0.8-1.0X ratio typically)

- Amplify library with optimal PCR cycles (determined empirically to minimize bias) [24]

Library QC:

- Quantify library yield using fluorometric methods

- Assess fragment size distribution using automated electrophoresis

- Verify adapter ligation efficiency through qPCR if needed

- Acceptance Criteria: Library concentration ≥10 nM, fragment size within platform specifications, minimal adapter dimer [23]

Functional Validation (For Clinical Assays):

- Sequence control samples with known variants

- Assess sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility

- Document all validation data for regulatory compliance [26]

NGS Quality Control Workflow: This diagram illustrates the complete quality control pathway for NGS testing, highlighting critical checkpoints and decision points where CLIA compliance is essential for clinical applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Quality NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from diverse sample types | Select based on sample type (blood, tissue, cells); verify yield and purity specifications [24] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert nucleic acids to sequencer-compatible format | Choose platform-specific kits; consider input requirements and application needs [9] |

| Quality Control Assays | Verify quantity, size, and integrity of nucleic acids and libraries | Fluorometric quantification (Qubit), spectrophotometry (NanoDrop), automated electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer) [23] |

| Adapter/Oligo Sets | Enable sample multiplexing and platform recognition | Ensure unique dual indexing to prevent cross-contamination; verify compatibility with sequencing platform [25] |

| Enzymatic Mixes | Perform fragmentation, ligation, and amplification | Use high-fidelity polymerases to minimize errors; optimize enzyme-to-template ratios [24] |

| Purification Beads | Clean up reactions and select size ranges | Magnetic bead-based systems offer reproducibility; optimize bead-to-sample ratios [24] |

Regulatory Compliance Checklist

Pre-Analytical Phase

- Verify CLIA certificate appropriate for test complexity [22]

- Document specimen acceptance/rejection criteria [26]

- Establish nucleic acid extraction and QC protocols [23]

- Validate sample storage conditions to preserve integrity [26]

Analytical Phase

- Perform and document method validation/verification [26]

- Establish quality control procedures with acceptance criteria [26]

- Implement calibrated instrument maintenance schedules [26]

- Document all procedures in approved manual [26]

Post-Analytical Phase

- Establish result reporting protocols including critical values [26]

- Implement data storage and retention systems [20]

- Ensure patient access to test results as required by HIPAA [20]

- Maintain systems for result interpretation and consultation [26]

Quality Systems

- Perform semiannual/annual personnel competency assessments [26]

- Participate in approved proficiency testing programs [20]

- Establish comprehensive quality assessment program [26]

- Maintain documentation for all regulatory requirements [26]

Regulatory Relationships: This diagram shows the key components of CLIA compliance and how the recent LDT ruling reinforces CLIA as the primary regulatory framework for laboratory-developed tests.

Glossary of Essential QC Terminology

Table 1: Core QC Terminology for NGS Libraries

| Term | Definition | Importance in QC |

|---|---|---|

| Library Complexity | The number of unique DNA fragments in a library prior to amplification [27]. | High complexity ensures greater sequencing coverage and reduces the need for high redundancy, which is critical for detecting rare variants [27]. |

| Adapter Dimers | Artifacts formed by the ligation of two adapter molecules without an insert DNA fragment [28] [29]. | They consume sequencing throughput and can significantly reduce the quality of data. Their presence indicates inefficient library purification [28] [3]. |

| Duplication Rate | The fraction of mapped sequencing reads that are exact duplicates of another read (same start and end coordinates) [30]. | A high rate indicates low library complexity and potential over-amplification during PCR, which can bias variant calling [30]. |

| On-target Rate | The percentage of sequencing reads or bases that map to the intended target regions [30]. | Measures the efficiency and specificity of target enrichment (e.g., hybrid capture); a low rate signifies wasted sequencing capacity [30]. |

| Fold-80 Base Penalty | A metric for coverage uniformity, indicating how much more sequencing is required to bring 80% of target bases to the mean coverage [30]. | A score of 1 indicates perfect uniformity. Higher scores reveal uneven coverage, often due to probe design or capture issues [30]. |

| Depth of Coverage | The average number of times a given nucleotide in the target region is sequenced [30]. | Critical for variant calling confidence; lower coverage increases the chance of missing true variants (false negatives) [30]. |

| GC Bias | The non-uniform representation of genomic regions with high or low GC content in the sequencing data [30]. | Can lead to gaps in coverage and missed variants. Often introduced during library amplification [30]. |

| Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) | Measurable values that demonstrate how effectively a process, like an NGS workflow, is achieving key objectives [31] [32]. | Allow labs to track performance, identify bottlenecks, and ensure consistent, high-quality results over time [31]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most critical checkpoints for QC in an NGS library prep workflow? Implementing QC at multiple stages is crucial for success. The key checkpoints are [29]:

- Sample QC: Assess the quantity, purity (A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios), and integrity (e.g., RIN for RNA) of the starting material [33] [29].

- Fragmentation QC: Verify that the fragmentation process yielded the desired fragment size distribution [29].

- Final Library QC: Analyze the library for size distribution, concentration, and the absence of adapter dimers before sequencing [29] [3].

My final library yield is low. What are the most likely causes? Low yield can stem from issues at several steps. The primary causes and their fixes are summarized in the table below [28]:

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants like phenol, salts, or EDTA [28]. | Re-purify the input sample using clean columns or beads. Ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8, 260/280 ~1.8) [28]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Over- or under-estimating input concentration leads to suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry [28]. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV spectrophotometry for template quantification [4] [29]. |

| Inefficient Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or an incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio [28]. | Titrate adapter concentrations, ensure fresh ligase and buffer, and maintain optimal reaction conditions [28]. |

My sequencing data shows a high duplication rate. What does this mean and how can I prevent it? A high duplication rate indicates that many of your sequencing reads are not unique, which reduces the effective coverage of your genome. This is often a result of low library complexity [30]. To prevent it [27] [30]:

- Avoid Over-amplification: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary during library prep.

- Use Adequate Input: Ensure you are using sufficient input DNA to capture the original diversity of fragments.

- Employ Unique Molecular Barcodes: For ultrasensitive applications (e.g., ctDNA detection), use barcoding to label individual molecules before amplification, allowing bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates [27].

NGS Library Preparation and QC Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for NGS Library QC

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Fluorometric Dyes (Qubit) | Accurately quantifies double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or RNA without interference from contaminants, unlike UV spectrophotometry [4] [29]. |

| qPCR Quantification Kits | Specifically quantifies only DNA molecules that have adapters ligated to both ends, providing a count of "amplifiable" library molecules for accurate cluster generation [4] [3]. |

| Microfluidics-based Electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) | Provides high-sensitivity analysis of library fragment size distribution and identifies contaminants like adapter dimers [33] [29] [3]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | A collection of enzymes (ligases, polymerases), buffers, and adapters optimized for a specific sequencing platform and application [33]. |

| Molecular Barcodes (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to uniquely tag individual molecules before amplification, allowing bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates and errors [27]. |

| Target Enrichment Probes | Biotinylated oligonucleotides designed to capture genomic regions of interest via hybridization, crucial for targeted sequencing panels and exome sequencing [30]. |

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for the NGS Laboratory

Monitoring KPIs helps transform a reactive lab into a proactive, continuously improving operation.

Table 4: Key Performance Indicators for an NGS Lab

| KPI Category | Example KPIs | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Process & Data Quality | Assay-specific precision/accuracy; Library conversion efficiency; First-pass yield success rate [27] [31]. | Tracks the technical robustness of your workflows and the reliability of the final data [31]. |

| Operational & Business | Turn-around time per library; Consumable cost per analysis; Device uptime (e.g., sequencer, Bioanalyzer) [31]. | Measures efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and resource utilization to ensure project timelines and budgets are met [31]. |

| Inventory & Environment | Amount of wasted consumables; Free space in critical storage; Temperature in refrigerators/freezers [31]. | Prevents workflow interruptions and protects valuable samples and reagents by ensuring stable storage conditions [31]. |

Building a Robust QC Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

In the field of chemogenomics research, where understanding the complex interactions between small molecules and biological systems is paramount, the quality of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data is critical. The library preparation phase serves as the foundation for all subsequent analysis, and rigorous quality control (QC) at specific checkpoints is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data. Effective QC minimizes costly errors, reduces sequencing artifacts, and ensures that the resulting data accurately represents the biological system under investigation [29]. This guide provides a structured, step-by-step framework for implementing robust QC protocols throughout the NGS library preparation workflow, specifically tailored to support high-quality chemogenomic research.

The NGS Library Preparation Workflow: A Visual Guide

The following diagram illustrates the complete NGS library preparation workflow with its integrated quality control checkpoints, showing the sequence of steps and where critical QC interventions should occur.

Essential QC Checkpoints and Parameters

Implementing QC at the following critical junctures ensures the integrity of your NGS library throughout the preparation process.

Checkpoint 1: Starting Material QC

Purpose: To verify that the input nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) are of sufficient quality and quantity to proceed with library construction. High-quality starting material is the foundation for successful library preparation [29].

Critical Parameters and Methods:

Table: QC Parameters for Starting Material

| Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Assessment Methods | Impact of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Meets kit requirements (typically 1-1000 ng) | Fluorometry (Qubit), spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) | Low yield: insufficient material for library prep; High yield: potential over-representation |

| Purity | A260/A280 ~1.8 (DNA), ~2.0 (RNA); A260/A230 ~2.0 | Spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) | Contaminants (phenol, salts) inhibit enzymatic reactions in downstream steps [29] [33] |

| Integrity | High RIN/RQN >7 (RNA); intact genomic DNA | Capillary electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) | Degraded samples yield biased, fragmented libraries with reduced complexity [29] [33] |

Protocol:

- Quantification: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate concentration measurement of double-stranded DNA. Avoid relying solely on UV spectrophotometry, which can overestimate concentration due to contamination [34].

- Purity Assessment: Measure absorbance at 230nm, 260nm, and 280nm. Calculate A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios.

- Integrity Check: For RNA, use the Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to generate an RNA Integrity Number (RIN). For DNA, examine the electrophoregram for a tight, high-molecular-weight distribution.

Checkpoint 2: Fragmentation QC

Purpose: To confirm successful fragmentation and verify that the fragment size distribution aligns with the requirements of your sequencing platform and application.

Critical Parameters:

- Fragment Size Distribution: Should match the expected range for your application (e.g., 200-500bp for many Illumina applications).

- Fragment Homogeneity: Fragments should be uniformly sized without significant smearing or multiple peaks.

Protocol:

- After fragmentation, run a small aliquot (1 μL) on a Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, or agarose gel.

- Analyze the resulting electrophoregram for the primary peak size and distribution.

- Adjust fragmentation parameters (time, enzyme concentration) if the size distribution is not optimal.

Checkpoint 3: Post-Ligation QC

Purpose: To validate efficient adapter ligation and detect the formation of adapter dimers, which can compete with library fragments during sequencing and significantly reduce useful data output [29].

Critical Parameters:

- Adapter Ligation Efficiency: The majority of fragments should have adapters successfully ligated.

- Adapter Dimer Formation: Minimal to no adapter dimer peaks (~70-90bp) should be visible.

Protocol:

- Post-ligation, analyze the library using a high-sensitivity DNA assay on the Bioanalyzer or TapeStation.

- Look for a shift in fragment size corresponding to the addition of adapters.

- Check for a small peak around 70-90bp, indicating adapter dimers. If present, perform additional cleanup or size selection.

Checkpoint 4: Amplification QC

Purpose: To verify that PCR amplification was efficient without introducing significant bias or duplicates. Over-amplification can result in increased duplicates and biases, while under-amplification can lead to insufficient yield [29].

Critical Parameters:

- Amplification Efficiency: Library concentration should increase appropriately after PCR.

- PCR Bias: The size distribution and complexity should remain similar to pre-amplification profiles.

- Minimal Duplication: Avoid excessive PCR cycles that increase duplicate rate.

Protocol:

- Quantify the library before and after amplification using fluorometry.

- Check the size profile post-amplification to ensure it hasn't shifted significantly.

- Limit PCR cycles to the minimum necessary (typically 4-15 cycles) to maintain library complexity.

Checkpoint 5: Final Library QC

Purpose: To comprehensively assess the quality, quantity, and size distribution of the final library before sequencing. This is the last opportunity to identify issues that could compromise the entire sequencing run [29] [3].

Critical Parameters and Methods:

Table: QC Methods for Final NGS Libraries

| Method | What It Measures | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | Concentration of amplifiable molecules (with both adapters) | Molarity (nM) for accurate pooling | Most accurate for clustering; required for patterned flow cells [34] [3] |

| Fluorometry (Qubit) | Total double-stranded DNA concentration | Mass concentration (ng/μL) | Overestimates functional library if adapter dimers present [34] |

| Electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer) | Size distribution and profile | Fragment size, adapter dimer contamination, profile quality | Essential for visual quality assessment; not ideal for quantification of broad distributions [29] [34] |

Protocol:

- Quantification: Use qPCR for the most accurate quantification of amplifiable library fragments, especially when pooling multiple libraries [34] [3].

- Size Profiling: Run the final library on a Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to confirm the expected size distribution and check for adapter dimers or other contaminants.

- Normalization: Precisely normalize libraries based on qPCR-derived molarity to ensure equal representation in multiplexed sequencing.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and kits are fundamental to successful NGS library preparation and quality control.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA/RNA from various sample types | Choose based on sample source (e.g., tissue, cells, FFPE) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment, end-repair, A-tail, and ligate adapters | Select platform-specific (Illumina, MGI) and application-specific kits [35] [36] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplify library fragments with minimal errors | Essential for maintaining sequence accuracy and reducing bias [35] |

| Magnetic Beads | Purify and size-select fragments between steps | Bead-to-sample ratio is critical for optimal size selection [35] |

| QC Assay Kits (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) | Analyze size distribution and integrity | Use high-sensitivity assays for final library QC [29] |

| Quantification Kits (Qubit, qPCR) | Accurately measure concentration | qPCR provides most accurate quantification for pooling [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my final library yield low, and how can I fix this? A: Low library yield can result from several issues:

- Poor input quality: Degraded DNA/RNA or contaminants (phenol, salts) inhibit enzymes. Re-purify input material and verify purity ratios (A260/280 ~1.8, A260/230 ~2.0) [29] [28].

- Inefficient ligation: Ensure fresh ligase, optimal adapter-to-insert ratio, and proper reaction conditions (temperature, time) [37] [28].

- Overly aggressive cleanup: Magnetic bead ratios that are too high can exclude desired fragments. Precisely follow recommended bead:sample ratios [28].

Q2: How can I prevent adapter dimers in my library? A: Adapter dimers form when excess adapters ligate to each other instead of library fragments. Prevent them by:

- Optimizing adapter concentration using correct molar ratios during ligation [37].

- Incorporating dual-size selection bead cleanups to remove small fragments before and after amplification [35].

- Using fresh, properly prepared adapters and ensuring they are not degraded [37].

- Validating each preparation with a high-sensitivity electrophoresis assay to detect dimers early [29].

Q3: What is the most accurate method for quantifying my final library before sequencing? A: qPCR is the gold standard for final library quantification because it specifically measures amplifiable molecules containing both adapter sequences [34] [3]. This is crucial for determining optimal cluster density on the flow cell. Fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) measure total dsDNA, including non-functional fragments, and can lead to overestimation, while UV spectrophotometry should be avoided for final library quantification due to poor sensitivity and specificity [34].

Q4: My Bioanalyzer trace shows a broad size distribution. Is this acceptable? A: It depends on your application. For amplicon or small RNA sequencing, a tight size distribution is expected. For whole genome or transcriptome sequencing, a broader distribution (e.g., 200-500bp) is normal. However, an abnormally broad distribution with multiple peaks could indicate uneven fragmentation, contamination, or poor size selection, which may require protocol optimization [34].

Q5: How does automation improve NGS library preparation QC? A: Automation significantly enhances reproducibility and reduces human error by:

- Standardizing pipetting volumes and reaction setups, minimizing technician-to-technician variability [37].

- Providing precise temperature control for enzymatic steps (ligation, amplification).

- Reducing cross-contamination through non-contact dispensing.

- Enabling detailed audit trails for troubleshooting and regulatory compliance [37].

Why is starting material QC critical for NGS success?

The quality of your DNA or RNA starting material is the foundational step upon which your entire Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) experiment is built. Success in NGS heavily relies on the quality of the starting materials used in the library preparation process [29]. High-quality starting materials ensure accurate and representative sequencing data, while compromised samples can lead to biased results, loss of valuable sequencing material, and compromised library complexity, ultimately wasting reagents, sequencing cycles, and research time [28] [29].

The core parameters you must assess for any starting material are Quantity, Purity, and Integrity. Failure to properly evaluate these can lead to a cascade of problems in downstream library preparation, including enzyme inhibition during fragmentation or ligation, biased representation of your sample, and ultimately, failed or unreliable sequencing runs [28].

How do I quantify DNA/RNA, and what methods should I avoid?

Accurate quantification is essential to determine the appropriate amount of starting material for your specific NGS library prep kit. Using too little DNA or RNA can lead to low library yield and poor coverage, while too much can cause over-amplification artifacts and bias [28].

The table below summarizes the common quantification methods and their recommended use cases.

Table: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Quantification Methods for NGS

| Method | Principle | What It Measures | Recommended for NGS? |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) | Measures UV absorbance at 260 nm [33]. | Total nucleic acid concentration; also assesses purity via 260/280 and 260/230 ratios [33]. | Not recommended for final library quantification. Can overestimate usable material by counting non-template background like contaminants or free nucleotides [28] [4]. |

| Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | Fluorescent dye binding specifically to DNA or RNA [4]. | Concentration of specific nucleic acid type (e.g., dsDNA, ssDNA, RNA) [4]. | Yes, highly recommended. Provides more accurate quantification of the target nucleic acid than spectrophotometry [28] [4]. |

| qPCR-based Methods | Amplification of adapter-ligated sequences using real-time PCR [3]. | Concentration of amplifiable library molecules with adapters on both ends [3]. | Yes, essential for final library quantification. Specifically quantifies the molecules that will actually cluster on the flow cell [3] [4]. |

Key Takeaway: For starting material QC, use fluorometric methods (Qubit) for accurate concentration measurement. Avoid relying solely on NanoDrop for quantification, though it is useful for a quick purity check. For the final library, qPCR-based quantification is considered the gold standard for most Illumina-based workflows [3] [4].

How do I assess sample purity, and what are the acceptable values?

Purity assessment ensures your sample is free of contaminants that can inhibit the enzymes (e.g., polymerases, ligases) used in library preparation. This is typically done using UV spectrophotometry [33] [29].

Table: Interpreting Spectrophotometric Ratios for Sample Purity

| Absorbance Ratio | Target Value | What It Indicates | Common Contaminants |

|---|---|---|---|

| A260/A280 | ~1.8 (DNA)~2.0 (RNA) [33] [29] | Protein contamination. | Residual phenol or protein from the extraction process [28]. |

| A260/A230 | >2.0 [29] | Chemical contamination. | Salts, EDTA, guanidine, carbohydrates, or organic solvents [28]. |

Troubleshooting Purity Issues: If your ratios are outside the ideal ranges, it is recommended to re-purify your input sample using clean columns or beads to remove inhibitors before proceeding with library preparation [28].

How is sample integrity measured, and why does it matter?

Integrity refers to the degree of degradation of your nucleic acids. Using degraded starting material is a primary cause of low library complexity and yield, as it provides fragmented templates for library construction [28] [29].

- DNA Integrity: Visually assessed using gel electrophoresis (agarose) or automated electrophoresis systems (e.g., Agilent TapeStation, Bioanalyzer). High-quality genomic DNA should appear as a single, high-molecular-weight band with minimal smearing below it [28].

- RNA Integrity: Quantified using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation), which generates an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or (RQN). This score ranges from 1 (completely degraded) to 10 (perfectly intact) [33]. A high RIN/RQN score indicates intact RNA molecules, which is crucial for representative transcriptome data [33] [29].

FAQ: Troubleshooting Common Starting Material QC Issues

Q1: My Bioanalyzer trace shows a smear instead of a sharp band. What should I do? This indicates sample degradation [28]. If the smear is severe, the sample should not be used for NGS as it will result in a low-complexity library. For RNA, a low RIN score (e.g., below 7) confirms degradation. It is best to repeat the nucleic acid extraction, paying close attention to RNase-free techniques for RNA and avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Q2: My sample has good concentration but poor 260/230 ratio. Can I still use it? A low 260/230 ratio suggests chemical contamination that can inhibit enzymatic reactions [28]. Do not proceed without cleaning up the sample. Re-purify the DNA or RNA using column-based or bead-based clean-up protocols to remove salts and other chemical contaminants. After clean-up, re-quantify and re-assess the purity ratios [28].

Q3: I have a limited amount of a precious sample with low concentration. How can I proceed? For low-input protocols, quantification and QC become even more critical. Use highly sensitive fluorometric assays (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). For RNA, consider a qPCR assay during library generation to assess the quality and quantity of the input prior to final library preparation, as traditional QC methods may not be sensitive enough [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential QC Instruments & Reagents

Table: Key Equipment and Reagents for Starting Material QC

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) | Accurate quantification of specific nucleic acid types (dsDNA, RNA). | More specific than spectrophotometry; requires specific assay kits for different nucleic acids. |

| Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) | Rapid assessment of sample concentration and purity (A260/A280 & A260/230). | Useful for initial screening but can overestimate concentration; not suitable for low-concentration samples. |

| Automated Electrophoresis System (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation, Fragment Analyzer) | Gold-standard for assessing nucleic acid integrity and size distribution. | Provides a RIN for RNA and visual profile for DNA; higher throughput systems (e.g., Fragment Analyzer) are available for large-scale projects [38]. |

| qPCR Instrument | Accurate quantification of amplifiable library molecules; can be used for QC during low-input library generation [38]. | Essential for final library quantification; targets adapter sequences to count only functional molecules [3]. |

Workflow Diagram: Starting Material QC for NGS

The following diagram summarizes the decision-making workflow for assessing DNA and RNA starting material quality before NGS library preparation.

In the construction of high-quality chemogenomic NGS libraries, Quality Control (QC) following fragmentation and adapter ligation is not merely a recommended step—it is a fundamental determinant of experimental success. These checkpoints serve to validate that the library molecules have been properly prepared for the subsequent sequencing process, ensuring that the resulting data is both reliable and reproducible. Efficient post-fragmentation and post-ligation QC directly mitigates the risk of costly sequencing failures, biased data, and inconclusive results in downstream drug discovery analyses [29].

The core objective at this stage is to confirm two key parameters: that the nucleic acid fragments fall within the optimal size range for your specific sequencing platform and application, and that the adapter ligation step has been efficient, with minimal formation of by-products like adapter dimers that can drastically reduce usable sequencing output [28] [3]. This guide provides a structured troubleshooting framework and detailed protocols to diagnose and rectify common issues encountered after fragmentation and ligation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

The table below outlines frequent problems, their root causes, and corrective actions based on established laboratory practices and guidelines [28].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Post-Fragmentation and Post-Ligation Issues

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Fragment Size Distribution [28]► Overly short or long fragments► High size heterogeneity (smeared profile) | ► Fragmentation Inefficiency: Over- or under-shearing due to miscalibrated equipment or suboptimal enzymatic reaction conditions [28]. | ► Optimize Fragmentation: Re-calibrate sonication/covaris settings or titrate enzymatic fragmentation mix concentrations. Run a fragmentation optimization gradient [28]. |

| High Adapter Dimer Peak (~70-90 bp) [28]► Sharp, dominant peak in electropherogram at ~70-90 bp, crowding out the library peak. | ► Suboptimal Adapter Ligation: Excess adapters in the reaction promote self-ligation [28].► Inefficient Cleanup: Incomplete removal of un-ligated adapters after the ligation step [28]. | ► Titrate Adapter Ratio: Optimize the adapter-to-insert molar ratio to find the ideal balance for your input DNA [28].► Optimize Cleanup: Increase bead-to-sample ratio during post-ligation cleanup to more efficiently remove short fragments and adapter dimers [28]. |

| Low Library Yield Post-Ligation [28]► Low concentration after ligation and cleanup, despite sufficient input. | ► Poor Ligation Efficiency: Caused by inhibited ligase, degraded reagents, or improper reaction buffer conditions [28].► Overly Aggressive Cleanup: Sample loss during bead-based size selection or purification [28]. | ► Check Reagents: Use fresh ligase and buffer, ensure correct reaction temperature.► Review Cleanup Protocol: Avoid over-drying magnetic beads and ensure accurate pipetting to prevent sample loss [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Analyses

Protocol: Assessing Fragment Size and Distribution

Principle: Microfluidics-based capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) provides a digital, high-resolution profile of fragment size distribution, replacing traditional, time-consuming agarose gel methods [3].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute 1 µL of the post-fragmentation or post-ligation library according to the manufacturer's specifications for the relevant assay (e.g., High Sensitivity DNA kit).

- Instrument Operation: Load the sample onto the designated chip or cartridge. The system automatically separates fragments via electrophoresis and detects them with an intercalating fluorescent dye.

- Data Analysis: The software generates an electropherogram and a virtual gel image. Key data outputs include:

- Peak Profile: A sharp, single peak indicates a tight size distribution. A broad or multi-peak profile suggests uneven fragmentation [28] [29].

- Average Fragment Size: Confirms the library is within the optimal range for your sequencing platform (e.g., 300-500 bp for many Illumina systems).

- Presence of Adapter Dimers: A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp indicates significant adapter-dimer formation [28].

Protocol: Quantifying Amplifiable Libraries via qPCR

Principle: While fluorometry (Qubit) measures total DNA concentration, quantitative PCR (qPCR) specifically quantifies only library fragments that have adapters ligated to both ends—the "amplifiable" molecules that will actually cluster on the flow cell [3]. This is critical for accurate loading and optimal cluster density.

Methodology:

- Standard Curve: Prepare a dilution series of a library standard with known concentration.

- Reaction Setup: Mix diluted, unknown library samples with a qPCR master mix containing primers that bind to the adapter sequences.

- Amplification & Quantification: Run the qPCR program. The cycle threshold (Ct) values for unknown samples are interpolated from the standard curve to determine the molar concentration of amplifiable molecules [3].

- Interpretation: A significant discrepancy between Qubit (ng/µL) and qPCR (nM) concentrations suggests a high proportion of molecules are not properly ligated or are adapter dimers, requiring further optimization.

Visual Guide to the QC Workflow