Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Hydrolysate Toxin Tolerance in Bioproduction

The efficient bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into high-value chemicals and biofuels is a cornerstone of sustainable industrial processes.

Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Hydrolysate Toxin Tolerance in Bioproduction

Abstract

The efficient bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into high-value chemicals and biofuels is a cornerstone of sustainable industrial processes. However, pretreatment-generated hydrolysate toxins—including organic acids, furan derivatives, and phenolic compounds—severely inhibit microbial growth and productivity, posing a major economic bottleneck. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and bio-process engineers, synthesizing foundational knowledge of toxin mechanisms with cutting-edge strain engineering methodologies. We systematically explore the cellular targets of major inhibitors, evaluate rational and non-rational engineering strategies from cell envelope remodeling to transcriptional reprogramming, and present troubleshooting frameworks for optimizing tolerance phenotypes. By integrating validation techniques and comparative analyses of engineering approaches, this review aims to equip scientists with the tools to develop next-generation, robust microbial cell factories capable of thriving in inhibitory environments, thereby advancing the industrial translation of lignocellulosic bioprocesses.

Understanding the Adversary: Mechanisms of Hydrolysate Toxicity in Microbial Cell Factories

Welcome to the Hydrolysate Toxin Troubleshooting Center

This resource is designed to assist researchers in diagnosing and resolving common experimental challenges related to inhibitor toxicity in lignocellulosic hydrolysates. The following guides and protocols are framed within the broader thesis of optimizing strain engineering for improved hydrolysate toxin tolerance.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Q: My fermentative strain shows significantly reduced hydrogen production and slowed glucose consumption. I suspect inhibitor toxicity, but don't know the primary cause. How can I diagnose this?

A: This pattern typically indicates strong inhibition from phenolic compounds. Based on comparative studies, phenolic compounds like vanillin and syringaldehyde cause more severe inhibition than furan derivatives under the same concentration (15mM). Key diagnostic indicators include [1]:

- Delayed peak times of hydrogen production rate and glucose consumption

- Persistent presence of phenolic compounds (>55% remaining after 108h fermentation)

- Decreased carbon conversion efficiency and soluble metabolite production

Recommended Action: Quantify the degradation profiles of potential inhibitors. Furan derivatives are typically completely degraded within 72h, while phenolic compounds persist much longer. Focus on engineering strategies that enhance degradation of phenolic compounds specifically.

Q: I am working with S. cerevisiae and observe dramatic sensitivity to synthetic hydrolysate toxins (synHTs). Which genetic targets should I prioritize for engineering improved tolerance?

A: Recent QTL analysis of toxin-tolerant natural S. cerevisiae strains has identified several key genetic targets. Deletion of VMS1, YOS9, MRH1, and KCS1 genes resulted in significantly greater hydrolysate toxin sensitivity, confirming their importance in tolerance mechanisms [2].

Recommended Engineering Strategies:

- Replace VMS1 and MRH1 with natural strain alleles from toxin-tolerant strains

- Focus on the endoplasmic-reticulum-associated protein degradation pathway (VMS1, YOS9)

- Consider plasma membrane protein association (MRH1) and phosphatidylinositol signaling system (KCS1)

Experimental Validation: Knock-in strains with VMS1 and MRH1 replacements from the BCC39850 strain showed significantly increased ethanol production titers in the presence of synHTs compared to the parental CEN.PK2-1C strain [2].

Q: Electricity generation in my microbial fuel cells (MFCs) is inhibited by hydrolysate components. Which compounds are most problematic and what solutions exist?

A: Electricity generation inhibition varies significantly by compound type [3]:

- Phenolic compounds like syringaldehyde, vanillin, and certain cinnamic acids inhibit electricity generation at concentrations above 5mM

- Compounds including 2-furaldehyde, benzyl alcohol and acetophenone inhibit electricity generation even at concentrations less than 0.2mM

- 5-HMF and some phenolic compounds (trans-cinnamic acid, 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid) do not affect electricity generation from glucose at concentrations up to 10mM

Mitigation Strategies:

- Employ hydrolysis methods with low furan derivatives and phenolic compounds production

- Remove strong inhibitors prior to MFC operation

- Enrich for bacterial cultures with natural tolerance or genetically modify strains for improved tolerance

Quantitative Inhibition Data

Table 1: Comparative Inhibitory Effects on Dark Hydrogen Fermentation [1]

| Inhibitor Class | Specific Compound | Inhibition Coefficient | Hydrogen Yield Decrease | Degradation Profile (Time for Complete Removal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Vanillin | 14.05 | 17% | >55% remains after 108h |

| Phenolic Compounds | Syringaldehyde | 11.21 | Not specified | >55% remains after 108h |

| Furan Derivatives | 5-HMF | 4.35 | Not specified | Complete degradation after 72h |

| Furan Derivatives | Furfural | 0.64 | Not specified | Complete degradation after 72h |

Table 2: Organic Acid Toxicity Profiles in E. coli [4]

| Organic Acid | Typical Hydrolysate Concentration | IC50 in E. coli | Primary Mechanism of Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | 1-10 g/L | 2.75-8 g/L | Transmembrane pH disruption, anion accumulation |

| Formic acid | ~1 g/L (tenth of acetic) | Lower than acetate | High membrane permeability, intracellular pH drop |

| Levulinic acid | Lower than formic | Not specified | Weak acid uncoupling, anion-specific effects |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Inhibitor Effects on Hydrogen Fermentation [1]

Objective: Quantify the inhibitory effects of furan derivatives and phenolic compounds on dark hydrogen fermentation.

Materials:

- Fermentation medium with glucose as primary carbon source

- Standard anaerobic fermentation setup

- Pure compounds: furfural, 5-HMF, vanillin, syringaldehyde (15mM working concentration)

- HPLC system for metabolite analysis

- Gas collection apparatus for hydrogen quantification

Methodology:

- Set up parallel fermentation batches with each inhibitor compound at 15mM concentration

- Maintain control batch without inhibitors

- Monitor hydrogen production volumetrically every 12 hours

- Sample liquid phase every 24h for:

- Glucose consumption (HPLC)

- Inhibitor degradation profiles (HPLC)

- Soluble metabolite production

- Continue monitoring for minimum 108h to capture differential degradation rates

- Calculate inhibition coefficients based on hydrogen production delays

Key Parameters:

- Peak time of hydrogen production rate

- Glucose consumption rate

- Carbon conversion efficiency

- Inhibitor degradation half-life

Protocol 2: QTL Analysis for Hydrolysate Toxin Tolerance in S. cerevisiae [2]

Objective: Identify genetic loci controlling hydrolysate toxin tolerance in natural S. cerevisiae strains.

Materials:

- Toxin-tolerant natural S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., BCC39850)

- Laboratory strain (e.g., CEN.PK2-1C)

- Synthetic hydrolysate toxins (synHTs) mixture

- Standard yeast genetics tools for crossing and segregant analysis

- Phenotypic screening platform (microplate readers)

Methodology:

- Cross toxin-tolerant natural strain with toxin-sensitive laboratory strain

- Generate and array segregants

- Perform phenotypic screening of segregants for growth (OD600) and glucose consumption in presence of synHTs

- Conduct QTL mapping using phenotypic scores and genotypic data

- Identify candidate genes within significant QTL regions

- Validate through knockout and knock-in experiments in sensitive background

- Test ethanol production in validated strains with synHTs present

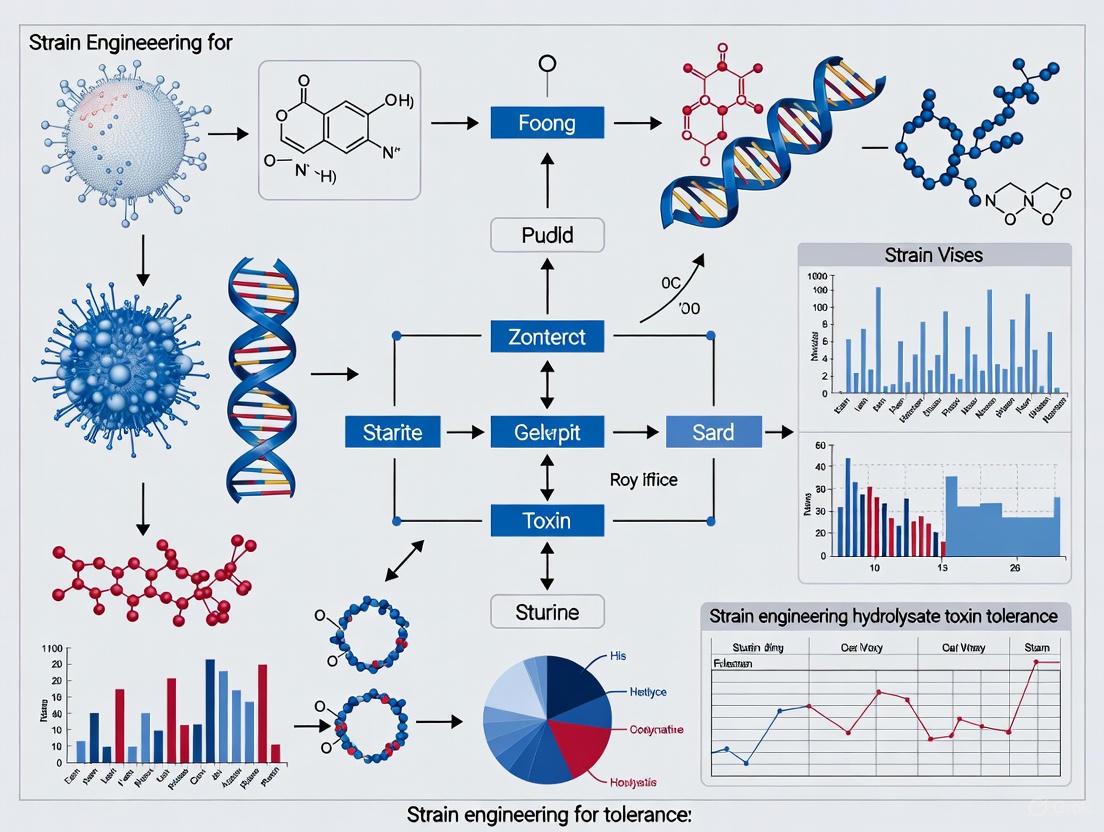

Visualization of Toxicity Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Figure 1: Hydrolysate Toxin Mechanisms and Engineering Targets

Figure 2: Genetic Analysis Workflow for Tolerance Traits

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hydrolysate Toxin Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Hydrolysate Toxins (synHTs) | Standardized screening of toxin tolerance | Enables reproducible phenotypic assessment without hydrolysate variability [2] |

| Vanillin (15mM stock) | Representative phenolic compound inhibitor | Use for maximal inhibition studies; monitor persistence beyond 108h [1] |

| 5-HMF (15mM stock) | Representative furan derivative inhibitor | Less persistent than phenolics; degrades within 72h [1] |

| Acetic acid (1-10 g/L) | Primary organic acid inhibitor | Concentration-dependent effect; consider external pH in experimental design [4] |

| QTL Mapping Toolkit | Genetic analysis of tolerance traits | Requires crossing of tolerant/sensitive strains and segregant analysis [2] |

| VMS1 and MRH1 natural alleles | Engineering targets for improved tolerance | Replacement in sensitive backgrounds increases ethanol production in synHTs [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Which inhibitor class has the most severe impact on fermentation performance?

A: Phenolic compounds demonstrate the strongest inhibition. At equal concentrations (15mM), vanillin and syringaldehyde show inhibition coefficients of 14.05 and 11.21 respectively, compared to 4.35 for 5-HMF and 0.64 for furfural. Vanillin causes up to 17% decrease in hydrogen yield and exhibits the maximum delay in peak hydrogen production rates [1].

Q: What are the primary genetic mechanisms recently identified for hydrolysate toxin tolerance?

A: Key genetic mechanisms involve multiple cellular pathways:

- Endoplasmic-reticulum-associated protein degradation (VMS1, YOS9)

- Plasma membrane protein association (MRH1)

- Phosphatidylinositol signaling system (KCS1)

These were identified through QTL analysis of a toxin-tolerant natural S. cerevisiae strain, with deletion of any single gene increasing sensitivity, and replacement with natural alleles improving ethanol production in inhibitor presence [2].

Q: How do inhibitor degradation profiles differ between compound classes?

A: Significant differences exist in degradation kinetics. Furan derivatives (furfural, 5-HMF) are typically completely degraded within 72h of fermentation. In contrast, phenolic compounds (vanillin, syringaldehyde) persist much longer, with over 55% remaining unconverted after 108h fermentation. This persistence contributes to their stronger inhibitory effects [1].

Q: What practical approaches can mitigate inhibitor effects in bioreactor operations?

A: Three primary strategies have demonstrated effectiveness:

- Employ hydrolysis methods that minimize formation of furan derivatives and phenolic compounds during pretreatment

- Implement physical or chemical removal of strong inhibitors prior to fermentation

- Develop bacterial cultures with enhanced tolerance through enrichment or genetic modification [3]

Genetic engineering approaches focusing on the identified tolerance genes provide promising routes for improved industrial strains.

FAQ: Troubleshooting Membrane Integrity Assays

Q: In my membrane integrity assays, I am observing unexpected cell lysis in the control groups. What could be the cause?

Unexpected lysis in control groups often points to issues with the experimental setup or reagent toxicity. The table below summarizes common problems and solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background lysis in untreated cells [5] | The assay buffer or medium itself is toxic to the cell line. | Titrate all buffer components and run a viability assay on the buffer alone. |

| Detergent-like effects [6] | Solvents used to dissolve toxins (e.g., DMSO) are affecting membrane lipids. | Use the lowest possible concentration of solvent and include a vehicle control. |

| Pore-forming toxin contamination [5] | Residual toxins from previous experiments contaminate equipment. | Implement strict decontamination protocols for labware and work surfaces. |

| Variable results between replicates | Inconsistent cell culture conditions leading to varying membrane composition. | Standardize culture media, passage number, and cell confluency at the time of assay. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Membrane Potential for Functional Pore Detection A more sensitive functional assay is to measure membrane depolarization, a direct consequence of pore formation by many toxins [5].

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate and grow to 70-80% confluency.

- Dye Loading: Incubate cells with a cationic, membrane-potential-sensitive fluorescent dye (e.g., DiBAC₄(3)) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Baseline Measurement: Read fluorescence (excitation ~488 nm, emission ~515 nm) to establish a baseline.

- Toxin Application: Add your toxin or hydrolysate of interest to the wells.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately measure fluorescence every 1-2 minutes for 60-90 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence over time. An increase in fluorescence indicates membrane depolarization, as the dye enters and binds to intracellular components upon pore formation [5].

FAQ: Investigating Energy Depletion and ATP Dysregulation

Q: My data suggests a toxin is depleting cellular ATP, but I cannot detect significant membrane pores. What other mechanisms should I investigate?

ATP depletion without overt membrane rupture suggests toxins are targeting internal metabolic processes. Key areas to investigate are summarized below.

| Observation | Implicated Mechanism | Investigation Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid ATP drop [5] | Pore formation causing ion gradient collapse and uncontrolled ATP synthase activity. | Repeat membrane potential assays with higher sensitivity; use patch-clamping to detect small pores. |

| Gradual ATP depletion [7] | Disruption of mitochondrial function (e.g., electron transport chain) or direct inhibition of metabolic enzymes. | Measure mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1 assay, TMRM) and oxygen consumption rate (Seahorse Analyzer). |

| Impaired nutrient uptake [6] | Toxin-induced internalization or inhibition of specific nutrient transporters (e.g., glucose, amino acids). | Perform radiolabeled or fluorescent nutrient uptake assays in the presence and absence of the toxin. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) A collapse in ΔΨm is a key event in toxin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and intrinsic apoptosis [8].

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a multi-well plate as for the membrane potential assay.

- Staining: Incubate cells with a ΔΨm-sensitive dye like JC-1. In healthy cells with high ΔΨm, JC-1 forms aggregates (red fluorescence). In depolarized cells, it remains as monomers (green fluorescence).

- Toxin Treatment: Expose cells to the toxin for a predetermined time.

- Analysis: Measure fluorescence using a microplate reader or analyze by flow cytometry. Calculate the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio. A decrease in this ratio indicates mitochondrial depolarization.

Toxin-Induced Energy Disruption Pathways

FAQ: Addressing Oxidative Stress and Macromolecular Damage

Q: How can I distinguish between primary oxidative stress (a direct toxin effect) and secondary oxidative stress resulting from energy collapse?

Determining the sequence of events is key. The following workflow and table can guide your experimental design.

| Experimental Approach | Primary Oxidative Stress | Secondary Oxidative Stress |

|---|---|---|

| Time-course measurement of ROS and ATP/ΔΨm | ROS increase precedes ATP depletion and ΔΨm collapse. | ATP depletion/ΔΨm collapse precedes ROS increase. |

| Antioxidant pre-treatment (e.g., N-Acetylcysteine) | Protects against both ROS and subsequent cell death. | Fails to prevent initial ATP depletion and cell death. |

| Inhibitor studies | Inhibiting ROS does not prevent energy collapse. | Inhibiting energy collapse (if possible) prevents ROS generation. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) This protocol uses the common fluorescent probe H₂DCFDA to detect general ROS levels in cells [8].

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate.

- Dye Loading: Wash cells with PBS and load with 10-20 µM H₂DCFDA in a serum-free buffer. Incubate for 30-45 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Carefully wash cells twice with PBS to remove excess extracellular dye.

- Treatment and Measurement: Add fresh buffer containing your toxin or hydrolysate. Immediately begin measuring fluorescence (excitation ~485 nm, emission ~535 nm) kinetically. Include a positive control (e.g., menadione or tert-butyl hydroperoxide).

- Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence to the initial reading. An increase in the normalized fluorescence over time indicates ROS generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for investigating toxin mechanisms and engineering tolerant strains.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Cationic Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., DiBAC₄(3)) | Detection of membrane depolarization by measuring fluorescence changes upon entry into depolarized cells [5]. |

| ΔΨm-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., JC-1, TMRM) | Assessment of mitochondrial health; a loss of potential indicates dysfunction and is a key apoptotic signal [8]. |

| ROS-Sensitive Probes (e.g., H₂DCFDA) | Quantification of general oxidative stress levels within live cells [8]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing System | Enables targeted knockout or knock-in of genes identified in QTL studies (e.g., VMS1, KCS1) to validate their role in toxin tolerance [9]. |

| HPLC-MS Systems | Identification and quantification of specific toxic compounds within complex hydrolysates, and analysis of metabolic changes in engineered strains [8]. |

Experimental Workflow for Strain Optimization

A streamlined Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is the most effective framework for optimizing strain tolerance [10].

Strain Optimization DBTL Workflow

Detailed DBTL Cycle Protocols

Design Phase: Generating Diversity

- Rational Design: Based on QTL analysis or known mechanisms (e.g., genes involved in ERAD, membrane composition, or phosphatidylinositol signaling) [9], design specific gene edits (knock-outs, knock-ins, promoter swaps).

- Random/Diversity Generation: Use Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) [10] [11]. Serial passage strains in increasing concentrations of the toxic hydrolysate for many generations. For a more targeted approach, create a CRISPR-based genomic library to saturate specific genomic regions of interest with mutations.

Build Phase: Strain Construction

Test Phase: High-Throughput Phenotyping

- Culture the engineered strain library in 96- or 384-well plates with sub-lethal concentrations of the hydrolysate.

- Use automated systems (e.g., colony pickers with phenotyping, plate readers) to measure key parameters [11]:

- Growth: Optical density (OD600) over time.

- Membrane Integrity: Fluorescence-based assays with membrane-impermeant dyes.

- Energy Status: Luminescence-based ATP assays.

- Product Yield: e.g., Ethanol titer for yeast strains [9].

Learn Phase: Data Analysis and Target Identification

- Sequence the genomes of the top-performing strains to identify causal mutations.

- For a systems-level view, perform transcriptomic or metabolomic profiling on tolerant vs. sensitive strains.

- Use machine learning to integrate the genotypic and phenotypic data, building predictive models to inform the design of the next, more effective DBTL cycle [10].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my microbial production strain show inhibited growth and reduced product yield in lignocellulosic hydrolysates? Weak organic acids (e.g., acetic, sorbic) present in lignocellulosic hydrolysates are a primary cause. At low external pH (below the acid's pKa), the undissociated acid form diffuses passively across the plasma membrane. Once inside the neutral cytosol, it dissociates, releasing protons (H+) that acidify the cytoplasm and anions that accumulate to toxic levels. This dual assault disrupts pH homeostasis, inhibits metabolic enzymes, and compromises cell viability, leading to poor performance [12] [13].

Q2: What are the primary intracellular targets of weak acid anions? Recent research has identified specific, conserved enzymatic targets. In Staphylococcus aureus, acetate anions directly bind to and inhibit D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase (Ddl), an essential enzyme for peptidoglycan biosynthesis. This inhibition depletes intracellular D-Ala-D-Ala pools, compromising cell wall integrity [14]. Systems-level analyses in cancer cells (a model for metabolic vulnerabilities) suggest that enzymes in glycolysis (e.g., GAPDH), the pentose phosphate pathway, and fatty acid metabolism are particularly susceptible to pH fluctuations and anion inhibition [15].

Q3: How can I experimentally measure intracellular pH (pHi) changes in response to weak acids in my microbial culture? You can use ratiometric, genetically encoded pH reporters like pHluorin. The following protocol is adapted from a Bacillus subtilis study [16]:

- Strain Engineering: Genetically modify your target strain to express a ratiometric pH-sensitive fluorescent protein (e.g., pHluorin, IpHluorin) under a constitutive or inducible promoter.

- Culture and Stress: Grow the engineered strain to the exponential phase in an appropriate buffered medium. Expose the culture to your weak acid stressor (e.g., 3 mM potassium sorbate or 25 mM potassium acetate at an external pH of 6.4).

- Live Imaging: Use fluorescence time-lapse microscopy with a temperature-controlled incubation chamber (e.g., 37°C). Immobilize cells on a thin agarose-medium pad within a sealed chamber to maintain aerobic conditions.

- Data Acquisition: Capture images using a wide-field fluorescence microscope with a high-resolution objective (e.g., 100x/1.3 oil). Take sequential exposures at two excitation wavelengths (e.g., 390 nm and 470 nm).

- Ratiometric Analysis: Calculate the ratio of fluorescence emissions (typically 510 nm) from the two excitation wavelengths for individual cells over time. Convert this ratio to a specific pHi value using a calibration curve generated for the reporter.

Q4: Which engineering strategies can enhance microbial tolerance to weak acids? Multiple synthetic biology strategies have proven effective [17] [18]:

- Cell Envelope Engineering: Modify membrane lipid composition to increase saturation, enhancing stability. Engineer membrane proteins and efflux pumps to expel anions and protons.

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Overexpress or engineer master regulators of the stress response, such as Haa1p in yeast, which controls a regulon of genes involved in weak acid tolerance [12].

- Targeted Pathway Engineering: Boost the capacity of specific pathways to counteract anion toxicity. For example, increasing alanine racemase (Alr1) activity in S. aureus elevates the intracellular D-Ala pool, outcompeting acetate for binding to Ddl and restoring peptidoglycan synthesis [14].

- Global Cellular Fitness: Employ evolutionary engineering or global transcription machinery engineering (gTME) to select for mutants with inherently higher robustness to acidic stress [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Growth Inhibition in Bioreactor

- Symptoms: Extended lag phase, reduced specific growth rate, and decreased final biomass in a fermentation using a hydrolysate feedstock.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause 1: Accumulation of toxic weak acid anions (e.g., acetate) from the hydrolysate or as a metabolic by-product.

- Solution 1: Implement in situ product recovery (ISPR). Integrate a membrane-based reactive extraction system that continuously removes the weak acid from the fermentation broth. This reduces product inhibition and allows for sustained microbial activity [19].

- Solution 2: Engineer your production strain for enhanced tolerance using the strategies outlined in FAQ A4, focusing on membrane transporters and anion efflux systems.

Problem: Inconsistent Intracellular pH Measurements

- Symptoms: High variability in calculated pHi values between cells in a population or between experimental replicates.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause 1: Inherent single-cell heterogeneity in the weak acid stress response.

- Solution 1: This is a biological reality, not just noise. Use single-cell microscopy methods (as in A3) to quantify this heterogeneity, as it can reveal subpopulations critical for survival [16]. Ensure consistent and controlled imaging conditions to minimize technical variability.

- Cause 2: Phototoxicity from repeated exposure to excitation light during live imaging.

- Solution 2: Perform a phototoxicity control experiment. Compare the generation times of fluorescent reporter strains with and without repetitive light exposure. Optimize exposure times and intervals to ensure growth is not significantly affected [16].

Table 1: Inhibitory Effects of Common Weak Acids on Microorganisms

| Weak Acid | Typical Inhibitory Concentration | Primary Organism Studied | Key Inhibitory Mechanisms & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid | 25 mM - 100 mM [16] [12] | Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Lowers pHi, accumulates anions; inhibits Ddl in S. aureus [14]; induces osmotic stress and metabolic disruption. |

| Sorbic Acid | ~3 mM [16] | Bacillus subtilis | Acts as a protonophore uncoupler, dissipating the membrane potential more effectively than less lipophilic acids [16]. |

| Lactic Acid | Varies by process | Engineered Yeasts | Accumulation during fermentation inhibits cell growth and productivity; often targeted for removal via extraction [19]. |

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid (3-HP) | >28 g/L (~0.27 M) [19] | Fermentation Processes | Accumulation increases organic phase viscosity by 50% during reactive extraction, complicating downstream processing [19]. |

Table 2: Key Metabolic Enzymes Identified as Vulnerable to Low pHi and Anion Inhibition

| Enzyme | Pathway | Function | Vulnerability & Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase (Ddl) | Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis | Catalyzes the formation of the D-Ala-D-Ala dipeptide for cell wall cross-linking. | Directly inhibited by binding of acetate anions; leads to reduced peptidoglycan cross-linking and compromised cell wall integrity [14]. |

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | Glycolysis | Catalyzes the 6th step of glycolysis, producing 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. | In silico models predict its activity is highly sensitive to acidic pHi; inhibition reverses the Warburg effect in cancer models, suggesting a key control point in carbon metabolism [15]. |

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) | Glycolysis | Catalyzes the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to fructose-6-phosphate. | Predicted by systems analysis to be a potential target whose inhibition has amplified anti-proliferative effects at acidic pHi [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Weak Acid Tolerance via Growth Kinetics This fundamental protocol measures the direct impact of a weak acid on microbial growth.

- Medium Preparation: Prepare a minimal defined medium buffered to your desired pH (e.g., pH 6.4 using MOPS or another suitable buffer).

- Acid Supplementation: Supplement the medium with a range of concentrations of the weak acid salt (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 50 mM potassium acetate). Include a no-acid control.

- Inoculation and Cultivation: Inoculate the media with a dilute culture of your test strain in the early exponential phase. Use multiple biological replicates.

- Monitoring: Grow cultures under optimal conditions (e.g., 37°C with agitation). Monitor optical density (OD600) periodically until the control culture reaches stationary phase.

- Analysis: Calculate the specific growth rate (μ) for each condition during the exponential phase and the final biomass yield. Plot these parameters against the weak acid concentration to determine the inhibitory threshold [16].

Protocol 2: Testing the Role of Specific Genes in Weak Acid Tolerance This uses gene deletion or overexpression to confirm the function of a candidate tolerance gene.

- Strain Construction: Use targeted genetic methods (e.g., CRISPR-Cas, homologous recombination) to create a deletion mutant or an overexpression strain for your gene of interest (e.g.,

alr1orHAA1). Include an empty-vector or wild-type isogenic control. - Phenotypic Screening: Subject the engineered and control strains to the growth kinetics protocol (Protocol 1) under weak acid stress.

- Genetic Complementation: For deletion mutants, reintroduce a functional copy of the gene on a plasmid to confirm that the observed phenotype is due to the specific gene deletion and not an off-target effect [14].

- Metabolic Rescue: If the gene is involved in metabolite synthesis (e.g.,

alr1producing D-Ala), supplement the growth medium with the metabolite (e.g., 5 mM D-Ala) to test if it rescues the growth defect [14].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Weak Acid Toxicity. Weak acids diffuse into the cell and dissociate in the neutral cytoplasm, leading to intracellular acidification and toxic anion accumulation.

Diagram 2: Strain Engineering and Troubleshooting Workflow. A systematic approach for diagnosing weak acid toxicity and implementing solutions to enhance microbial tolerance.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Weak Acid Toxicity Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ratiometric pHluorin (IpHluorin) | Genetically encoded reporter for single-cell intracellular pH (pHi) measurement. | Enables direct, localized, and dynamic quantification of pHi in individual cells using fluorescence microscopy [16]. |

| Tri-n-octylamine (TOA) in n-decanol | Organic phase for reactive extraction of acids from fermentation broth. | Used in membrane contactors for in situ recovery of inhibitory acids like 3-HP, reducing product toxicity [19]. |

| Hollow-Fiber Membrane Contactors | Device for dispersion-free reactive extraction integrated with a bioreactor. | Provides high surface area for acid transfer, maintains biocatalyst viability by limiting direct solvent contact, and prevents emulsion formation [19]. |

| Machine Learning Medium Optimization (e.g., ART) | Computational tool for optimizing culture medium composition to improve acid tolerance. | Can identify non-intuitive medium formulations that enhance production dynamics, such as revealing sensitivity to trace elements like boron [13]. |

| Cell-Specific Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMM) | Computational framework for predicting pHi-dependent metabolic vulnerabilities. | Integrates enzyme pH-activity profiles to simulate how pHi alters metabolic flux, identifying selective anti-proliferative targets [15]. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

Why is my microbial fermentation inhibiting despite low sugar concentrations?

Problem: Reduced microbial growth and metabolic activity in lignocellulosic hydrolysates, not attributable to nutrient deficiency or low sugar availability.

Root Cause: The presence of furan derivatives, primarily furfural (from pentose dehydration) and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) (from hexose dehydration), which are formed during the chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass [20] [4]. These compounds inhibit essential microbial functions.

Solution: Implement a multi-faceted approach to mitigate toxicity:

- Biological Detoxification: Employ microbial strains such as Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 or engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae that can convert furfural and HMF into less toxic alcohols and acids [21] [22].

- Genetic Engineering: Overexpress oxidoreductase genes (e.g., ADH6, ADH7, GRE2 in yeast) to enhance the microbe's innate capacity to reduce furanic aldehydes to their less inhibitory alcohol forms [21].

- Media Modulation: Adjust extracellular conditions by elevating potassium levels (e.g., +50 mM KCl) and pH (to ~6.0) to stabilize membrane potential and counteract alcohol toxicity [21].

- Process Optimization: Utilize adapted microbial strains through Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) to select for mutants with inherent tolerance to hydrolysate inhibitors [23] [24].

Why does my engineered strain lose productivity in actual hydrolysates compared to synthetic media?

Problem: A strain engineered for furan tolerance performs well in defined laboratory media but fails in genuine lignocellulosic hydrolysates.

Root Cause: Synergistic inhibition. The toxicity in real hydrolysates results from the combined effect of multiple inhibitors, not just furans. Furfural and HMF are rarely present in isolation; they co-occur with weak acids (e.g., acetic acid) and phenolic compounds [20]. This combination can disrupt multiple cellular targets simultaneously, overwhelming engineered single-mechanism tolerances.

Solution:

- Comprehensive Hydrolysate Profiling: Quantify all major inhibitor classes (furans, weak acids, phenolics) in your specific hydrolysate to understand the complete stress landscape.

- Engineer Multi-Tolerance: Combine several tolerance mechanisms in a single host. For example, integrate furan-converting reductases with efflux pump regulators and weak acid tolerance, as achieved in engineered Pseudomonas taiwanensis [23].

- Two-Stage Evolution: Subject your rationally engineered strain to a second stage of adaptive evolution directly in the target hydrolysate. This selects for mutations that confer robustness to the complex, synergistic inhibitor cocktail, as demonstrated in S. cerevisiae [24].

How do I confirm that furan derivatives are the primary cause of enzyme inhibition in my experiment?

Problem: Difficulty in directly attributing observed enzymatic inhibition to furan derivatives.

Root Cause: Furan aldehydes like furfural and HMF are highly reactive and can directly inhibit key fermentative enzymes by binding to active sites or causing redox imbalances [4].

Solution: Implement the following experimental workflow to confirm and characterize the inhibition:

Specific Protocols:

In Vitro Enzyme Activity Assay:

- Purify the target enzyme (e.g., from a central metabolic pathway like glycolysis).

- Perform the standard enzyme activity assay in the presence of varying, physiologically relevant concentrations of furfural or HMF (e.g., 0.5 - 5 mM).

- Compare the reaction rates (Vmax) and substrate affinity (Km) to control assays without inhibitors. A significant change in these kinetic parameters confirms direct inhibition [4].

In Vivo Metabolite Analysis:

- Cultivate your microbe in a medium with furans and perform rapid sampling.

- Quench metabolism instantly (e.g., cold methanol).

- Analyze intracellular metabolites using LC-MS. The accumulation of substrates upstream of a potentially inhibited enzyme, and a decrease in its products, pinpoints the metabolic bottleneck [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary molecular mechanisms by which furan derivatives inhibit cellular function?

Furan derivatives exert toxicity through multiple, concurrent mechanisms [4]:

- Enzyme Inhibition: Furfural and HMF can directly inhibit key dehydrogenases and aldolases in glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways, disrupting energy (ATP) and redox (NADH/NADPH) production.

- Redox Imbalance: Microbial reduction of furfural to furfuryl alcohol (FF-OH) and HMF to 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF) consumes cellular reductants (NAD(P)H). This drains the pool of reducing power essential for anabolic reactions and stress responses [21].

- Macromolecule Damage: These aldehydes can cause DNA damage and protein carbonylation, leading to mutagenesis and loss of protein function.

- Membrane Disruption: While more commonly associated with phenolic compounds, furan alcohols can also contribute to membrane fluidity issues, especially when combined with other inhibitors [20].

What are the key metabolic conversion products of furfural and HMF in microbes, and how do their toxicities compare?

Microbes detoxify furan aldehydes through sequential oxidation or reduction reactions. The end products are typically less toxic than the parent aldehydes. The table below summarizes the primary conversion pathways and the relative toxicity of these metabolites.

Table 1: Microbial Conversion Products of Furan Aldehydes and Their Relative Toxicity

| Precursor | Intermediate Product | Final Product | Typical Microbial Host | Toxicity Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furfural | Furfuryl Alcohol (FF-OH) | Furoic Acid | S. cerevisiae, A. baylyi ADP1 [22] [4] | Furfural > FF-OH > Furoic Acid [21] [22] |

| HMF | 2,5-Bis(Hydroxymethyl)Furan (BHMF, HMF-OH) | 5-Hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic Acid (HMFCA) | S. cerevisiae, A. baylyi ADP1 [22] [4] | HMF > BHMF > HMFCA [21] [22] |

| HMF | 5-Formyl-2-furancarboxylic Acid (FFA) | 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid (FDCA) | Various Oxidases [25] | HMF > FFA > FDCA |

Which genetic engineering strategies are most effective for improving furan tolerance?

The most robust strategies involve a combination of rational engineering and directed evolution:

Rational Engineering:

- Overexpression of Reductases: Introduce genes like GRE2, ADH6, or ADH7 (from S. cerevisiae) or ADH4 (from Scheffersomyces stipitis) to accelerate the conversion of furfural and HMF to their less toxic alcohols [21].

- Knock-out of Side-Activity Genes: Deleting the native GRE3 aldose reductase in S. cerevisiae minimizes the production of xylitol from xylose, which itself can inhibit xylose metabolism, thereby improving overall xylose fermentation in hydrolysates [24].

- Modulation of Regulators: In Pseudomonas, loss-of-function mutations in the transcriptional regulator mexT prevent expression of the mexEF-oprN efflux pump, conferring enhanced aldehyde tolerance [23].

Directed Evolution:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Furan Toxicity and Tolerance Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Furfural & HMF Standards | Analytical quantification and dose-response studies. | HPLC/LC-MS calibration for measuring inhibitor concentration in hydrolysates [22]. |

| Engineered Reductases (e.g., ADH6, GRE2) | Key enzymes for in vivo detoxification. | Overexpression in S. cerevisiae to enhance conversion of furans to less inhibitory alcohols [21]. |

| Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 | Model bacterium for studying detoxification pathways. | Investigating the complete oxidation of furfural to furoic acid and HMF to HMFCA [22]. |

| Adapted Industrial Strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Hosts for fermentation with innate robustness. | Serving as a chassis for further metabolic engineering for hydrolysate fermentation [21] [24]. |

| Ionic Liquids / Biphasic Systems | Solvents for pre-treatment and product recovery. | Used in chemical conversion of sugars to HMF/furfural; can also be used for in-situ extraction of inhibitors from fermentation broth [26]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) under Furan Aldehyde Stress

This protocol outlines the steps for generating tolerant microbial strains using ALE.

Detailed Steps:

- Inoculum and Medium:

- Prepare a chemically defined medium (e.g., Yeast Synthetic Complete or Mineral Salts Medium) containing a sub-inhibitory concentration of a furan aldehyde (e.g., 1 mM HMF) or a low percentage (e.g., 10%) of the target lignocellulosic hydrolysate [23].

- Serial Passaging:

- Inoculate the medium with the parent strain and incubate under optimal conditions (e.g., 30°C for yeast, 300 rpm shaking).

- Once the culture reaches mid- to late-exponential phase, use it to inoculate a fresh medium of the same or a slightly higher inhibitor concentration. The transfer volume should be calculated to maintain a constant initial cell density (e.g., OD600 = 0.1).

- Increasing Selection Pressure:

- Gradually increase the concentration of the furan aldehyde or the percentage of hydrolysate in the medium as the population adapts and its growth rate recovers. This process should be repeated for dozens to hundreds of generations [24].

- Isolation and Screening:

- After significant adaptation, plate the final population to obtain single colonies.

- Screen these isolated clones in microtiter plates or small shake flasks for improved performance metrics, such as growth rate, maximum biomass, and most importantly, product (e.g., ethanol) yield and productivity under inhibitory conditions.

- Genomic Analysis:

Protocol for Quantifying Furan Detoxification Metabolites

This method details the analysis of furan aldehydes and their conversion products in microbial cultures using HPLC and LC-MS [22].

Materials:

- Culture supernatants from time-course experiments.

- HPLC system with Photo-Diode Array (PDA) detector.

- C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- LC-MS system for metabolite identification.

- Mobile Phase: 0.1% Formic acid in water and methanol (95:5, v/v).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect culture samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 3, 6, 12, 24 h). Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 13,500 x g for 3 min) to pellet cells. Filter the supernatant through a 0.2 µm membrane.

- HPLC Analysis:

- Inject the filtered supernatant onto the HPLC system.

- Use an isocratic elution with the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

- Monitor absorbance at 220 nm and 254 nm to detect different metabolites (e.g., acids vs. aldehydes).

- Quantify compounds by comparing peak areas to external standards of furfural, HMF, FF-OH, BHMF, furoic acid, and HMFCA.

- LC-MS Identification:

- For unknown metabolites, analyze samples using LC-MS with electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative modes.

- Identify compounds by their exact mass and fragmentation pattern (e.g., [M-H]⁻ for furoic acid at m/z 111.00877).

Phenolic compounds are a major class of plant-derived bioactive molecules recognized for their antimicrobial properties. Their effectiveness stems primarily from their ability to disrupt microbial membranes and interact with key hydrophobic targets within the cell. For researchers in strain engineering, understanding these mechanisms is crucial for designing robust microbial systems with enhanced tolerance to phenolic inhibitors found in lignocellulosic hydrolysates. This guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides practical protocols to support your work in optimizing strain performance.

FAQs: Mechanisms of Action

1. How do phenolic compounds primarily disrupt bacterial membranes? Phenolic compounds act through multiple mechanisms to compromise membrane integrity. Their resonance-stabilized structure allows them to embed within the lipid bilayer, causing permeabilization and destabilization. This action increases membrane fluidity and disrupts its function as a protective barrier, leading to leakage of cellular contents and impaired energy metabolism [27] [28]. The number and position of hydroxyl groups on the phenolic ring significantly influence this activity by determining their hydrophobicity and ability to integrate into membrane structures [28].

2. Why are Gram-positive bacteria generally more susceptible to phenolic antimicrobials than Gram-negative bacteria? The structural differences in cell envelopes dictate susceptibility. Gram-positive bacteria like Bacillus subtilis possess a single membrane and a thick peptidoglycan cell wall, but the absence of a protective outer membrane makes them more vulnerable to hydrophobic toxins like many phenolic compounds [29]. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli have a dual-membrane structure; their outer membrane contains lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that act as a formidable barrier against many hydrophobic antimicrobials [29].

3. What role does hydrophobicity play in the antimicrobial activity of phenolics? Hydrophobicity is a critical determinant of antimicrobial potency. More hydrophobic phenolic compounds can more effectively partition into the lipid core of microbial membranes [27]. Once incorporated, they can cause disorder in the lipid bilayer, compromise membrane integrity, and inhibit membrane-bound enzymes and proteins. This hydrophobicity-driven mechanism differs from traditional antibiotics, making phenolics effective against some drug-resistant pathogens [27].

4. Beyond membrane disruption, what other cellular targets do phenolic compounds affect? Phenolic compounds exhibit multi-target activity. They can:

- Inhibit critical extracellular microbial enzymes [27]

- Interfere with quorum sensing systems, reducing biofilm formation and virulence [27]

- disrupt energy metabolism by affecting membrane potential [27]

- Bind to and inactivate key proteins through non-covalent interactions (hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) [30]

5. How can understanding these mechanisms inform strain engineering for hydrolysate tolerance? Elucidating these mechanisms enables rational engineering strategies. Knowledge of membrane disruption guides modifications to membrane lipid composition (e.g., adjusting phospholipid head groups, fatty acid chain unsaturation) to enhance stability [29]. Understanding efflux mechanisms supports the engineering of transporter proteins to actively export toxic phenolics [29]. Additionally, targeting intracellular regulatory networks and repair pathways can improve overall cellular fitness in inhibitory environments [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Antimicrobial Assay Results

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Variations in phenolic compound solubility and stability.

Cause: Differences in microbial growth phase and inoculum preparation.

- Solution: Standardize inoculum preparation by using mid-log phase cultures and normalizing to a specific optical density (e.g., OD600 = 0.5). Use consistent cultivation media and conditions across experiments [27].

Cause: Inadequate control for pH-dependent activity.

- Solution: Phenolic activity can vary with pH. Always monitor and adjust the pH of your assay medium and include appropriate buffer controls (e.g., phosphate buffer pH 7.0) [31].

Problem: Difficulty Assessing Membrane Integrity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Non-specific dye interference in membrane permeability assays.

- Solution: When using propidium iodide or similar dyes, include proper controls: unstained cells, cells stained without treatment, and a positive control (e.g., cells treated with 70% isopropanol). Confirm dye stability and avoid light exposure during assays [27].

Cause: Overinterpretation of single-method membrane damage assessment.

Problem: Engineering Strains with Enhanced Phenolic Tolerance

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Limited understanding of specific phenolic compounds in your hydrolysate.

- Solution: Characterize your hydrolysate using HPLC or GC-MS to identify and quantify specific phenolic inhibitors (e.g., ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, vanillin, syringaldehyde) [31]. This enables targeted tolerance engineering.

Cause: Trade-offs between tolerance and production phenotypes.

- Solution: Implement iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles with appropriate screening strategies. Use multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) approaches to efficiently explore the engineering space and balance multiple objectives [33].

Cause: Ineffective transporter engineering for phenolic export.

- Solution: Screen both endogenous and heterologous transporter proteins. For example, overexpression of specific transporters in S. cerevisiae has shown 5-8 fold increases in secretion of toxic compounds like fatty alcohols and β-carotene [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Membrane Disruption via Cytoplasmic Leakage

Principle: This method quantifies the release of intracellular components (e.g., ATP, nucleic acids, ions) following phenolic compound exposure, indicating membrane integrity loss.

Materials:

- Microbial culture in mid-log phase

- Phenolic compound stock solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL in DMSO)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0)

- ATP detection kit or UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Water bath or incubator shaker

Procedure:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min) and wash twice with potassium phosphate buffer.

- Resuspend cells to OD600 = 0.5 in fresh buffer.

- Divide suspension into aliquots:

- Test group: Add phenolic compound at desired concentrations

- Negative control: Add equivalent volume of solvent alone

- Positive control: Add 70% isopropanol

- Incubate at cultivation temperature with shaking for 2-4 hours.

- Collect samples at regular intervals (0, 30, 60, 120, 240 min):

- Centrifuge immediately (12,000 × g, 5 min)

- Collect supernatant for analysis

- Quantification options:

- Nucleic acid leakage: Measure A260 of supernatant

- ATP leakage: Use luciferase-based ATP detection kit

- Protein leakage: Measure A280 or use Bradford assay

- Calculation: Express leakage as percentage of positive control:

% Leakage = (Atest - Anegative)/(Apositive - Anegative) × 100

Technical Notes:

- Maintain consistent cell density across experiments

- Include replicate samples (n ≥ 3)

- Account for potential absorption of phenolic compounds at measured wavelengths

- For time-course studies, ensure consistent sampling intervals [27]

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Phenolic Compound Toxicity in Hydrolysate-Mimicking Conditions

Principle: This protocol determines MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) of specific phenolic compounds or hydrolysate fractions under controlled conditions relevant to industrial fermentation.

Materials:

- Sterile 96-well microtiter plates

- Phenolic compounds: vanillin, syringaldehyde, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid

- Defined mineral medium or diluted hydrolysate

- Microbial inoculum (OD600 = 0.1)

- Microplate reader with temperature control

Procedure:

- Prepare phenolic compound stock solutions at 100× final desired concentration in appropriate solvent.

- Create two-fold serial dilutions directly in microplate wells using defined medium.

- Include controls:

- Growth control: Medium + inoculum + solvent

- Sterility control: Medium + phenolics (no inoculum)

- Solvent control: Medium + maximum solvent concentration used

- Add standardized inoculum (final OD600 = 0.01).

- Incubate with continuous shaking in microplate reader at optimal growth temperature.

- Monitor optical density (OD600) every 30-60 minutes for 24-48 hours.

- Analysis:

- MIC: Lowest concentration showing no growth

- IC50: Calculate from growth curves using nonlinear regression (sigmoidal dose-response model)

- Additional assessments:

Technical Notes:

- Use at least 6-8 concentrations for accurate IC50 determination

- Include replicate wells (n ≥ 4)

- For anaerobic cultures, use sealed plates or anaerobic chamber

- Confirm compound stability under assay conditions via HPLC sampling [31] [27]

Data Presentation

Table 1: Membrane Disruption Efficacy of Common Phenolic Compounds

| Phenolic Compound | Class | MIC against E. coli (μg/mL) | MIC against S. aureus (μg/mL) | Primary Mechanism | Relative Hydrophobicity (log P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | Phenolic acid | 500-1000 | 250-500 | Membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition | Low (0.98) |

| Caffeic acid | Phenolic acid | 250-500 | 125-250 | Membrane permeabilization, antioxidant | Medium (1.47) |

| Ferulic acid | Phenolic acid | 500-1000 | 250-500 | Membrane disruption, quorum sensing inhibition | Medium (1.51) |

| p-Coumaric acid | Phenolic acid | 1000-2000 | 500-1000 | Membrane integrity loss | Medium (1.46) |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | 125-250 | 62-125 | Membrane disruption, DNA intercalation | High (2.16) |

| Catechin | Flavonoid | 250-500 | 125-250 | Membrane damage, protein binding | Medium (1.46) |

Table 2: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Phenolic Tolerance in Microbial Systems

| Engineering Target | Specific Modification | Toxin/Stress | Microbial Host | Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane lipid composition | Modified phospholipid head groups | Octanoic acid | E. coli | 66% increase in product titer | [29] |

| Transport systems | Overexpression of endogenous transporter | β-carotene | S. cerevisiae | 5.8-fold increase in secretion | [29] |

| Transport systems | Overexpression of heterologous transporter | Fatty alcohols | S. cerevisiae | 5-fold increase in secretion | [29] |

| Cell wall engineering | Enhanced peptidoglycan cross-linking | Ethanol | E. coli | 30% increase in product titer | [29] |

| Adaptive evolution | Sequential cultivation under inhibitor stress | Lignin-derived aromatics | S. bombicola | 36.32% higher SLs production | [34] |

| Regulatory networks | Feedback-regulated stress response | Hydrolysate inhibitors | E. coli | 40% increase in hydroquinone titer | [29] |

Pathway Visualization

Mechanisms of Phenolic Toxicity and Engineering Solutions

Membrane Integrity Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenolic Compound Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phenolic compound standards (gallic, ferulic, caffeic, p-coumaric acids) | Quantitative analysis, calibration standards, bioactivity assays | Obtain high-purity (>95%) standards; store at -20°C protected from light |

| HPLC-grade solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, water) | Chromatographic separation and analysis of phenolic compounds | Use with 0.1% formic or acetic acid for improved peak shape in reverse-phase HPLC |

| Protonophores (CCCP, valinomycin) | Positive controls for membrane disruption studies | Prepare fresh solutions in DMSO; handle with care due to toxicity |

| Membrane integrity dyes (propidium iodide, SYTOX Green) | Assessment of membrane permeability in live cells | Validate staining protocol for each microbial strain; include proper controls |

| ATP detection kit (luciferase-based) | Quantitative measurement of cytoplasmic leakage | Follow manufacturer's protocol precisely; measure luminescence immediately |

| Defined mineral medium | Standardized cultivation for toxicity assays | Enables precise control of experimental conditions; repeatable results |

| Lignocellulosic hydrolysate | Real-world substrate for tolerance assessment | Characterize phenolic content via HPLC; store at -20°C to prevent degradation |

| Solid-phase extraction cartridges (C18, polymeric) | Clean-up and concentration of phenolic compounds from complex matrices | Condition with methanol and water before use; optimize elution solvent |

| Reducing agents (ascorbic acid, NaBH4) | Prevention of phenolic oxidation during extraction and analysis | Add to extraction solvents and buffers; particularly important for alkaline hydrolysis |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which microbial strain is most suitable for initiating research on hydrolysate toxin tolerance? Your choice of microbial strain should align with your specific research goals. Zymomonas mobilis exhibits high native tolerance to ethanol and fermentation inhibitors, making it an excellent candidate for rapid ethanol production processes, with yields up to 98% of the theoretical maximum [35]. Saccharomyces cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) demonstrates superior robustness in undetoxified lignocellulosic hydrolysates and possesses the ability to co-ferment both glucose and xylose, which is a critical advantage for comprehensive biomass utilization [36]. Escherichia coli KO11 offers a highly versatile and genetically tractable system, ideal for foundational studies and engineering novel tolerance pathways [36].

Q2: What are the primary physiological changes observed in these microbes under ethanol stress? A common critical response across these bacteria is the remodeling of their cell membranes to reduce fluidity. In Z. mobilis, this involves a decrease in the unsaturated-to-saturated (U/S) fatty acid ratio and changes in hopanoid content [37]. Similarly, E. coli adapts by decreasing its U/S fatty acid ratio [37]. In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the response includes an upregulation of genes responsible for ergosterol biosynthesis (e.g., erg24, erg3, erg2), reinforcing membrane integrity under high ethanol concentrations (>10%) [37].

Q3: Which non-rational engineering method is most effective for improving hydrolysate tolerance? Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) is a highly effective and widely used non-rational engineering approach. This technique involves the serial passaging of microbes in progressively higher concentrations of toxic hydrolysate, selecting for spontaneous mutations that confer a growth advantage. For instance, ALE has been successfully applied to evolve Bacillus subtilis strains capable of robust growth in 100% DDGS-hydrolysate medium, where the growth of the parent strain was inhibited. Whole-genome resequencing of evolved isolates frequently revealed mutations in global regulators like codY, as well as in genes related to oxidative stress (e.g., katA, perR) [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Growth in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate Fermentations

Problem: Inadequate microbial growth and prolonged fermentation times when using lignocellulosic hydrolysates.

Solution: Implement a systematic diagnostic and mitigation strategy.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Specific Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Analyze Inhibitor Profile | Quantify levels of common inhibitors like furans (furfural, HMF), weak acids (acetic acid), and phenolics. High concentrations can halt metabolism. |

| 2 | Consider Hydrolysate Detoxification | If inhibitor levels are high, physically or chemically detoxify the hydrolysate. Over-liming or adsorption with activated charcoal are common methods to remove inhibitors for initial experiments. |

| 3 | Apply Nutrient Supplementation | Supplement the hydrolysate with a nitrogen source. Protocol: Use Corn Steep Liquor (CSL) at 2% w/v. Prepare a 20% w/v CSL stock by dissolving 200 g in 1L distilled water, adjust pH to 7.0, centrifuge (5000 × g, 30 min), and sterile-filter (0.22 μm) the supernatant [36]. |

| 4 | Use an Adapted Inoculum | Pre-adapt cells to the hydrolysate. Protocol: For Z. mobilis AX101, prepare a seed culture in a low-concentration hydrolysate (e.g., 3% glucan loading equivalent) without extra nutrients to force adaptation [36]. |

| 5 | Verify Strain Choice | If problems persist, re-evaluate your strain. Switch to a strain with proven hydrolysate robustness like S. cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) for complex hydrolysates [36]. |

Low Ethanol Yield and Productivity

Problem: Despite reasonable growth, the final ethanol titer, yield, or production rate is below industrial targets (e.g., < 40 g/L, < 0.42 g/g sugars, < 0.7 g/L/h).

Solution: Optimize fermentation parameters and strain physiology.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Specific Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm Metabolic Capacity | Verify that your strain is engineered for your target carbon sources. Wild-type Z. mobilis only consumes glucose, fructose, and sucrose. For xylose fermentation, you must use a metabolically engineered strain like Z. mobilis AX101 or S. cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) [36] [35]. |

| 2 | Control Fermentation pH | Maintain an optimal pH to prevent metabolic slowdown. Protocol: Conduct fermentations in pH-controlled bioreactors. For Z. mobilis, a pH range of 3.8 to 7.5 is tolerable, but a specific setpoint (e.g., pH 5.5) should be maintained [36] [35]. |

| 3 | Evaluate Solids Loading | Use a high solids loading to achieve high sugar and subsequent ethanol titers. Protocol: Perform enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation at 15-18% w/w solids loading. For example, hydrolyze AFEX-pretreated corn stover with Spezyme CP (15 FPU/g cellulose) and Novozyme 188 (32 pNPGU/g cellulose) at 50°C, pH 4.8 for 96 hours [36]. |

| 4 | Profile Sugar Consumption | Monitor glucose and xylose consumption rates. In hydrolysates, xylose consumption is often the major bottleneck. If xylose remains at the end of fermentation, it significantly reduces overall yield, confirming the need for a superior xylose-fermenting strain [36]. |

Comparative Quantitative Data

Table 1: Fermentation Performance in CSL Media and Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate

| Parameter | E. coli KO11 | S. cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST) | Z. mobilis AX101 | Notes & Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol Yield (g/g) | > 0.42 | > 0.42 | > 0.42 | Co-fermentation on CSL media with 100 g/L total sugars [36]. |

| Final Ethanol Titer (g/L) | > 40 | > 40 | > 40 | Co-fermentation on CSL media with 100 g/L total sugars [36]. |

| Max Productivity (g/L/h) | > 0.7 (0-48h) | > 0.7 (0-48h) | > 0.7 (0-48h) | Co-fermentation on CSL media [36]. |

| Xylose Fermentation Rate | 5-8x faster than yeast | Baseline (slowest) | 5-8x faster than yeast | Rate comparison in CSL media [36]. |

| Growth in Hydrolysate | High robustness | Highest robustness | Lower robustness | Performance in 15% w/v solids AFEX-CS water extract [36]. |

| Xylose Consumption in Hydrolysate | Limited | Greatest extent and rate | Limited | Performance in 18% w/w AFEX-CS enzymatic hydrolysate [36]. |

| Theoretical Ethanol Yield | Engineered | Engineered | Up to 98% | Native yield for Z. mobilis on glucose [35]. |

Table 2: Physiological and Molecular Responses to Ethanol Stress

| Characteristic | Z. mobilis | E. coli | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Lipid Response | ↓ U/S ratio; Altered hopanoid content [37] | ↓ U/S ratio (~40% decrease) [37] | ↑ Ergosterol biosynthesis genes [37] |

| Key Membrane Components | Vaccenic acid, Hopanoids (e.g., THBH) [37] | Vaccenic acid, Palmitic acid [37] | Ergosterol, Oleic acid, Stearic acid [37] |

| Primary Stressor | High ethanol, ROS from Fe-S enzymes [37] | High ethanol [37] | High ethanol, ROS [37] |

| Genetic Tractability | Improved (CRISPR, recombineering) [35] | Excellent [36] | Excellent [36] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Hydrolysate Tolerance

This protocol is adapted from the method used to evolve Bacillus subtilis for DDGS-hydrolysate tolerance [38].

Objective: To generate microbial strains with enhanced tolerance to a specific lignocellulosic hydrolysate and improved growth performance.

Materials:

- Microorganism: Wild-type or starting strain of E. coli, Z. mobilis, or S. cerevisiae.

- Growth Media: Standard rich medium (e.g., LB for E. coli).

- Evolution Media: Lignocellulosic hydrolysate (e.g., DDGS-hydrolysate) at a concentration that inhibits but does not completely prevent growth of the starting strain. This can be supplemented with base nutrients if necessary.

- Equipment: Automated bioreactor or shake flasks, spectrophotometer for OD measurement, incubator, sterile cryovials for glycerol stocks.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow the starting strain overnight in standard rich medium.

- Initial Passage: Inoculate the evolution media at a low starting OD (e.g., 0.05-0.1). Incubate under standard conditions (temperature, agitation).

- Serial Transfer: Monitor growth. When the culture reaches the late exponential phase or a predetermined OD, use it to inoculate a fresh batch of evolution media at the same starting OD. The hydrolysate concentration can be maintained or gradually increased over successive transfers.

- Repetition and Monitoring: Repeat the serial transfer for multiple generations (e.g., 50-200+). Periodically check for improved growth metrics (e.g., maximum OD, growth rate) compared to the starting strain.

- Isolation and Archiving: After significant improvement is observed, streak the culture onto solid media to isolate single colonies. Create glycerol stocks of evolved isolates.

- Genomic Analysis: Perform whole-genome resequencing of evolved isolates to identify mutations associated with the tolerant phenotype (e.g., mutations in global regulators like codY or oxidative stress genes like katA) [38].

Protocol for Fermentation Performance Assessment in pH-Controlled Bioreactors

This protocol is based on the comparative fermentation study of E. coli KO11, S. cerevisiae 424A(LNH-ST), and Z. mobilis AX101 [36].

Objective: To systematically compare the fermentation kinetics (growth, sugar consumption, product formation) of different ethanologens under controlled conditions.

Materials:

- Strains: The ethanologens to be compared.

- Seed Media: Liquid media containing nitrogen source, 50 g/L total sugar, appropriate buffer, and antibiotics if required.

- Fermentation Media: Contains 2% w/v CSL, 100 g/L total sugar, designated buffer, and antibiotics.

- Equipment: pH-controlled fleaker fermentors or bench-top bioreactors (200 mL working volume), pH probe, sampling needles, water bath with recirculation heater, magnetic stirring plate.

Procedure:

- Seed Culture: Transfer a frozen glycerol stock of each strain to 100 mL of seed media. Grow overnight under largely anaerobic conditions at the respective optimal temperature and 150 rpm agitation.

- Fermentor Inoculation: Centrifuge the seed culture, resuspend the cell pellet in fermentation media, and transfer to the fermentor to achieve an initial OD600 of 0.5.

- Fermentation Conditions: Maintain temperature via water bath. Control pH by automatic addition of acid/base. Stir at 150 rpm.

- Sampling: Take periodic samples (e.g., every 4-12 hours) for analysis.

- Analysis:

- Cell Growth: Measure optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

- Substrates and Products: Analyze sample supernatant via HPLC to quantify sugar consumption (glucose, xylose) and product formation (ethanol, organic acids).

- Data Calculation: Calculate key performance parameters including ethanol yield (g ethanol / g sugar consumed), final titer (g/L), and volumetric productivity (g/L/h).

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Strain Engineering Workflow for Toxin Tolerance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Hydrolysate Toxin Tolerance Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate | Provides the real-world mixture of fermentable sugars and inhibitors for stress studies. | DDGS-hydrolysate (from steam-exploded Distiller's Dried Grains with Solubles) or AFEX-pretreated corn stover hydrolysate [38] [36]. |

| Corn Steep Liquor (CSL) | A cost-effective and complex nitrogen source for fermentation media supplementation. | FermGold CSL, used at 2% w/v in fermentation media. Prepare a 20% w/v stock, pH to 7.0, clarify by centrifugation [36]. |

| Enzyme Cocktails | For the saccharification of pretreated biomass to produce fermentable hydrolysate. | Spezyme CP (cellulase, 15 FPU/g cellulose) and Novozyme 188 (β-glucosidase, 32 pNPGU/g cellulose) for cellulose hydrolysis [36]. |

| Adaptive Evolution Setup | Platform for serial passaging of microbes to select for spontaneous tolerance mutations. | Can use simple shake flasks or automated bioreactor systems for continuous culture [38]. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | For targeted genetic modifications to delete, insert, or overexpress specific genes. | CRISPR-Cas9 systems and recombineering tools are under development for Z. mobilis [35]. Standard tools are well-established for E. coli and S. cerevisiae. |

| Analytical HPLC | For precise quantification of substrates (sugars) and products (ethanol, organic acids) in fermentation broths. | Essential for calculating key performance metrics like yield and productivity [36]. |

Building Defenses: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Tolerance and Robustness

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides

Cell Envelope Integrity Issues

Q1: My engineered strain shows poor survival in hydrolysate despite good laboratory performance. What could be causing this?

A: This common issue often stems from compromised cell envelope integrity in complex environments. The cell envelope, comprising membranes and cell walls, is the first line of defense against hydrolysate toxins. Failure often indicates insufficient reinforcement of structural components.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform a Membrane Integrity Assay: Use propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry. A viability drop of >20% compared to control conditions indicates significant membrane damage.

- Analyze Cell Wall Thickness: Use transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on samples from both standard and hydrolysate media. Visually compare the peptidoglycan layer; engineered strains should maintain or increase thickness under stress.

- Check for Protein Mislocalization: As highlighted in spatial proteomics, mislocalization of membrane transporters can impair function [39]. Confirm the correct localization of your engineered efflux pumps using fluorescence tagging.

Solution: If damage is confirmed, consider reinforcing the envelope by overexpressing genes for cardiolipin synthesis (for membrane stability) or OmpA-like proteins (for outer membrane integrity). Re-run the assays to verify a reduction in PI-positive cells to within 10% of control levels.

Q2: How can I verify that my genetic modification to the cell wall is actually increasing toxin tolerance?

A: Direct measurement of mechanical strength and permeability is required, as genetic changes do not always translate to functional improvements.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Permeability: Use a nitrocefin assay. Nitrocefin is a chromogenic β-lactam that changes color upon hydrolysis by β-lactamase in the periplasm. Monitor the rate of color change spectrophotometrically at 486 nm. A slower rate in your engineered strain indicates reduced permeability.

- Test for Mechanical Strength: Use microfluidic or micromanipulation techniques to apply shear stress. Note the pressure point at which lysis occurs. A successful modification should increase the lysis threshold by at least 15%.

Solution: Correlate these physical measurements with growth assays in hydrolysate. A successful modification should show a direct correlation between increased mechanical strength/reduced permeability and improved growth rate or yield.

Intracellular Engineering and Mislocalization

Q3: My strain expresses a detoxifying enzyme, but toxin clearance remains low. Why?

A: This typically indicates a problem with spatial organization inside the cell. The enzyme may be expressed but not localized to the correct subcellular compartment where the toxin is most concentrated or active [39].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Intracellular Localization: Fuse your enzyme of interest (e.g., a lactonase) with a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP). Use confocal microscopy to confirm it localizes to the cytoplasm as intended. Aggregation or mislocalization to inclusion bodies is a common failure point.

- Measure Enzyme Specific Activity in Cell Lysates: Compare the activity in your engineered strain versus a control strain expressing a cytosolic version of the same enzyme. A significant drop in specific activity suggests improper folding or aggregation.

Solution: If mislocalization or aggregation is detected, address protein folding and trafficking. Strategies include:

- Using stronger or different ribosomal binding sites.

- Co-expressing chaperone proteins (e.g., GroEL/GroES).

- Adding compatible solutes (e.g., betaine) to the growth medium to improve folding under stress.

Q4: How can I map the intracellular response to toxins with high resolution?

A: Leverage spatial transcriptomic and proteomic methods to understand the cell's reaction at the single-molecule level.

Troubleshooting Steps & Protocol:

- Adapt a High-Resolution Mapping Protocol: Methods like CMAP (Cellular Mapping of Attributes with Position) can be adapted for single-cell analysis to map molecular events spatially [40]. The core workflow involves:

- Domain Division: Partition cells under toxin stress into distinct physiological states (e.g., stressed, adapting, dying) based on transcriptomic profiles.

- Optimal Spot Assignment: Map specific metabolic fluxes or enzyme activities to these predefined states.

- Precise Location: Pinpoint the subcellular localization of key responses.

- Validate with Imaging: Correlate the mapped data with imaging techniques like FISH or immunofluorescence to confirm the spatial distribution of key mRNAs or proteins.

Extracellular Matrix and Community Interactions

Q5: My engineered strain performs well in monoculture but fails in a co-culture or biofilm setting. What's wrong?

A: The failure is likely in the extracellular domain. The engineered trait might disrupt the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) or quorum-sensing molecules, which are critical for community survival and division of labor [41].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quantify EPS Production: Use the Congo red binding assay. Pellet cells from culture, resuspend in a Congo red solution, and incubate. After removal of cells, measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 490 nm. A decrease in absorbance indicates more Congo red has bound to the EPS, implying higher production. Compare your strain to a wild-type control.

- Analyze Biofilm Architecture: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or confocal microscopy to visualize biofilms formed on a relevant surface (e.g., a polymer bead). Look for differences in thickness and density compared to the control.

Solution: If EPS production is impaired, consider engineering the regulatory pathways that control EPS synthesis (e.g., the csg or pel operons in relevant species). The goal is to restore EPS production without compromising the primary engineered trait.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the most critical parameter to measure when assessing strain tolerance in hydrolysates? A: There is no single parameter. A robust assessment requires a spatially-informed multi-scale approach. You must evaluate:

- Cell Envelope: Membrane integrity (via staining) and permeability.

- Intracellular: Vitality (ATP levels), enzyme activity, and protein localization.

- Extracellular: Community structure and metabolite sharing.

Q: Which spatial omics technique is best for my tolerance research? A: The choice depends on your resolution needs and the model organism. The table below compares key methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Spatial Analysis Techniques for Strain Engineering

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Molecular Resolution | Key Application in Tolerance Research | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMAP [40] | Single-cell | Genome-wide transcripts | Maps single-cell heterogeneity in response to toxin gradients. | TRL 4-5 (Established for tissues, adapting for microbes) |

| Spatial Proteomics [39] | Subcellular | Proteins & complexes | Identifies mislocalization of detoxification enzymes under stress. | TRL 4 (Emerging for dynamic studies) |

| seqFISH/+ [40] | Subcellular | 10s-100s of transcripts | Visualizes the spatial organization of key stress response genes. | TRL 6 (Established for targeted panels) |

Q: How can I quickly test if my intervention at one spatial level (e.g., intracellular) is affecting another (e.g., extracellular)? A: Implement a three-layer assay cascade:

- Envelope: PI staining and flow cytometry (24h assay).

- Intracellular: Metabolite profiling via LC-MS from cell lysates (48h assay).

- Extracellular: Measure the composition of the spent medium (e.g., organic acids, polysaccharides) and its ability to support growth of a reporter strain (72h assay). Changes in the spent medium indicate an altered extracellular environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Spatial Engineering and Toxin Tolerance Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|