Cross-Validation in Phenotypic Screening: A Practical Guide for Robust and Predictive Assay Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of cross-validation in phenotypic screening.

Cross-Validation in Phenotypic Screening: A Practical Guide for Robust and Predictive Assay Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of cross-validation in phenotypic screening. It covers foundational concepts, demonstrating how cross-validation safeguards against over-optimistic model performance by rigorously testing predictive ability on unseen data [citation:10]. The guide details methodological implementations, from k-fold to cross-cohort validation, and explores advanced applications in modern, high-content screens like Cell Painting and pooled perturbation assays [citation:1][citation:8]. It addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as preventing data leakage during feature selection and choosing appropriate validation splits. Finally, it establishes a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of screening models, emphasizing performance metrics and data fusion strategies to enhance predictive accuracy and ensure reliable hit identification in drug discovery campaigns.

Why Cross-Validation is Non-Negotiable in Modern Phenotypic Screening

Estimating the real-world performance of a therapeutic candidate from limited experimental data remains one of the most significant challenges in pharmaceutical research. The high attrition rates in clinical development—with an average 14.3% likelihood of approval from Phase I to market—highlight the critical need for more predictive screening methodologies [1]. Phenotypic screening has re-emerged as a powerful approach for identifying biologically active compounds, potentially offering more physiologically relevant data than target-based methods. However, translating rich phenotypic profiles into accurate predictions of clinical success requires sophisticated computational integration and validation strategies. This guide objectively compares current methodologies for cross-validating phenotypic screening results, examining their experimental foundations, performance metrics, and utility in de-risking drug development.

Quantitative Comparison of Predictive Approaches

The following table summarizes key performance indicators and characteristics across major methodological paradigms for estimating therapeutic potential.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Predictive Methodologies in Drug Discovery

| Methodology | Reported Advantages | Key Limitations | Validation Approach | Therapeutic Area Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Benchmarks [2] | Real-time data updates; Advanced filtering (modality, MoA, biomarker) | Legacy solutions often provide overly optimistic POS | Historical clinical trial success rates; Path-by-path analysis | Oncology (HER2- breast cancer); 67,752 phase transitions analyzed |

| PDGrapher (AI Model) [3] | Direct perturbagen prediction (inverse problem); 25× faster training than indirect methods | Assumes no unobserved confounders; Performance varies by cancer type | Identified 13.37% more ground-truth targets in chemical interventions | 19 datasets across 11 cancer types; Competitive in genetic perturbation |

| Traditional Benchmarking [2] [4] | Industry-standard POS calculations | Static data; Overly simplistic POS multiplication; Underestimates risk | Phase-to-phase transition probabilities | Industry-wide: 3.4% success rate in oncology vs. 5.1% in prior studies [4] |

| High-Content Phenotypic Screening [5] | Single-pass classification across drug classes; Systems-level responses in individual cells | Limited biomarkers monitored simultaneously; Scalability challenges | Phenotypic profiling via Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics; GO-annotated functional pathways | Cancer-related drug classes; A549 non-small cell lung cancer cell line |

| Model-Informed Drug Development [6] | Quantitative prediction throughout development lifecycle; Shortened development cycles | Requires multidisciplinary expertise; Model must be "fit-for-purpose" | Regulatory acceptance via FDA FFP initiative; Dose-finding across multiple disease areas | Applied from early discovery to post-market lifecycle management |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

High-Content Phenotypic Screening Workflow

The ORACL (Optimal Reporter cell line for Annotating Compound Libraries) method provides a systematic approach for identifying reporter cell lines that best classify compounds into functional drug classes [5]:

Reporter Cell Line Construction: A library of triply-labeled live-cell reporter cell lines was created using the A549 non-small cell lung cancer cell line. The labeling system included:

- pSeg plasmid for cell image segmentation (mCherry RFP for whole cell, H2B-CFP for nucleus)

- Central Dogma (CD)-tagging with YFP to monitor expression of endogenous proteins

Image Acquisition and Processing: Cells were treated with compounds and imaged every 12 hours for 48 hours. Approximately 200 features of morphology and protein expression were measured for each cell, including:

- Nuclear and cellular shape characteristics

- Protein intensity, localization, and texture properties

Phenotypic Profile Generation: Feature distributions for each condition were transformed into numerical scores using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics to quantify differences between perturbed and unperturbed conditions. The resulting scores were concatenated into phenotypic profile vectors that succinctly summarized compound effects.

Classification Accuracy Assessment: The optimal reporter cell line (ORACL) was selected based on its ability to accurately classify training drugs across multiple mechanistic classes in a single-pass screen, validated through orthogonal secondary assays.

PDGrapher Model Architecture and Training

PDGrapher addresses the inverse problem in phenotypic screening—directly predicting perturbagens needed to achieve a desired therapeutic response rather than forecasting responses to known perturbations [3]:

Network Embedding: Disease cell states are embedded into protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks or gene regulatory networks (GRNs) as approximations of causal graphs.

Representation Learning: A graph neural network (GNN) learns latent representations of cellular states and structural equations defining causal relationships between nodes (genes).

Perturbagen Prediction: The model processes a diseased sample and outputs a set of therapeutic targets predicted to reverse the disease phenotype by shifting gene expression from diseased to treated states.

Validation Framework: Performance was evaluated across 38 datasets spanning chemical and genetic perturbations in 11 cancer types, with held-out folds containing either new samples in trained cell lines or entirely new cancer types.

Dynamic Benchmarking Methodology

Intelligencia AI's Dynamic Benchmarks address shortcomings of traditional benchmarking through several methodological innovations [2]:

Data Curation Pipeline: Incorporates new clinical development data in near real-time, drawing on decades of sponsor-agnostic interventional trials for unbiased historical benchmarking.

Advanced Filtering Capabilities: Proprietary ontologies enable filtering by modality, mechanism of action, disease severity, line of treatment, biomarker status, and population characteristics.

Path-by-Path Analysis: Accounts for non-standard drug development paths (e.g., skipped phases or dual phases) rather than assuming typical phase progression, providing more accurate probability of success assessments.

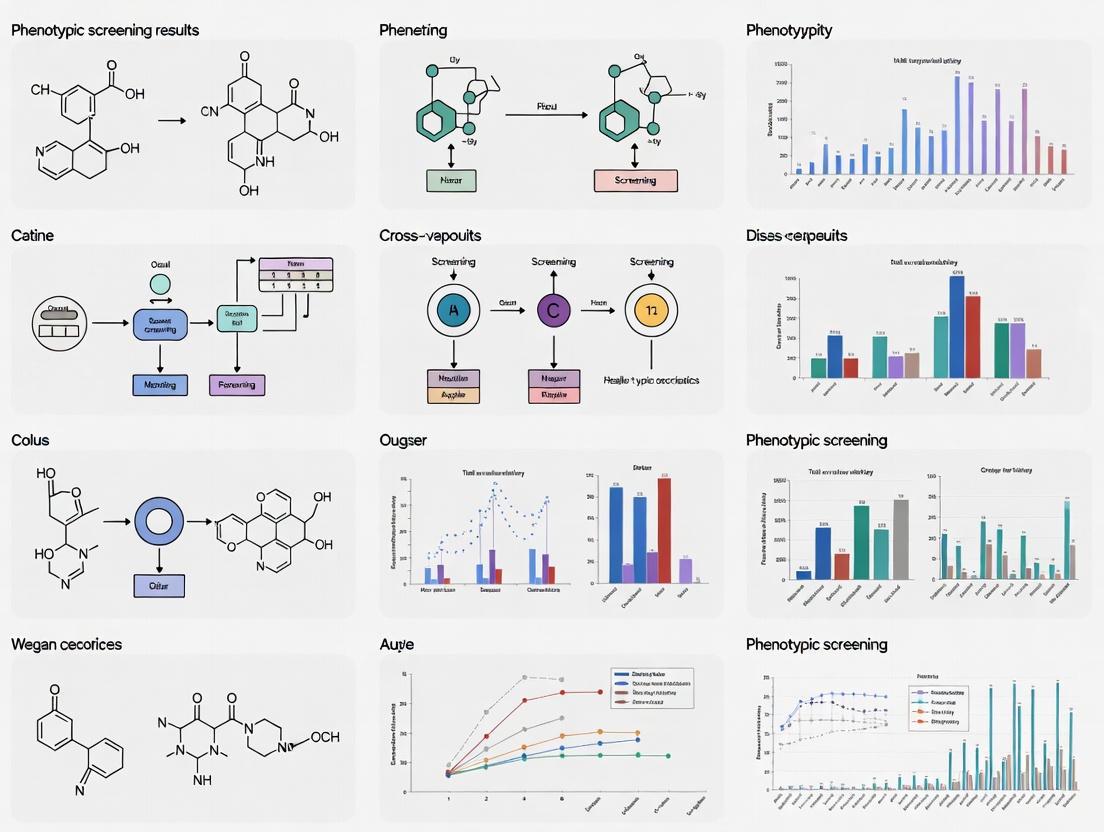

Visualizing Methodological Relationships and Workflows

Figure 1: Methodological Pathways for Performance Prediction

Figure 2: Validation Strategies for Predictive Performance

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for implementing the described methodologies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORACL Reporter Cells [5] | Live-cell phenotypic profiling | High-content screening for drug classification | Triply-labeled (H2B-CFP, mCherry-RFP, CD-YFP); Endogenous protein expression |

| PDGrapher Algorithm [3] | Combinatorial therapeutic target prediction | Phenotype-driven drug discovery | Graph neural network; Causal inference; Direct perturbagen prediction |

| Dynamic Benchmarks [2] | Clinical development risk assessment | Portfolio strategy and resource allocation | Real-time data updates; Advanced filtering; Path-by-path analysis |

| LINCS/CMap Databases [3] | Reference perturbation signatures | Mechanism of action identification | Gene expression profiles from chemical/genetic perturbations |

| BioGRID PPI Network [3] | Causal graph approximation | Network-based target identification | 10,716 nodes; 151,839 undirected edges for contextual embedding |

| Cell Painting Assay [7] | Morphological profiling | Phenotypic screening and mechanism prediction | Fluorescent dyes visualizing multiple organelles; High-content imaging |

The challenge of estimating real-world performance from limited data requires integrating multiple complementary approaches. High-content phenotypic screening provides rich biological context, AI models like PDGrapher enable direct target prediction, and dynamic benchmarking grounds these predictions in historical clinical outcomes. The most promising path forward involves strategically combining these methodologies—using phenotypic profiling to identify biologically active compounds, AI approaches to elucidate their mechanisms, and dynamic benchmarking to assess their clinical development risk. This integrated approach offers the potential to significantly improve the accuracy of translating limited experimental data into meaningful predictions of therapeutic success, ultimately addressing the high attrition rates that have long plagued drug development.

In the high-stakes field of drug discovery, where phenotypic screening serves as a crucial method for identifying first-in-class therapies, robust validation of predictive models is not merely a technical step but a fundamental requirement for success [8]. Phenotypic screening involves measuring compound effects in complex biological systems without prior knowledge of specific molecular targets, generating multidimensional data that demands statistically sound evaluation methods [9] [8]. Traditional single train-test splits, often called holdout validation, pose significant risks in this context, including high-variance performance estimates and potential overfitting to a particular data subset [10] [11] [12]. These limitations are particularly problematic when working with the expensive, hard-won data typical in pharmaceutical research, where reliable model assessment directly impacts resource allocation and project direction.

Cross-validation has emerged as the statistical answer to these challenges, with k-fold and repeated k-fold cross-validation representing two refined approaches that offer more dependable performance estimates [10] [13] [12]. These methods are especially valuable in phenotypic screening research, where they help researchers discern true biological signals from random fluctuations, thereby increasing confidence in predictions of compound bioactivity and mechanism of action [9]. By thoroughly evaluating model generalizability, these validation techniques provide a more accurate picture of how well a model will perform on new, unseen compounds – a critical consideration when prioritizing candidates for further development.

Understanding the Core Validation Methods

K-Fold Cross-Validation

K-fold cross-validation operates on a straightforward yet powerful principle: the dataset is randomly partitioned into k equal-sized subsets, or "folds" [11] [14]. The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining single fold for validation. This process ensures that every observation in the dataset is used exactly once for validation [11]. The final performance estimate is calculated as the average of the k validation scores, providing a more comprehensive assessment of model performance than a single split [14].

The choice of k represents a classic bias-variance tradeoff. Common practice typically employs 5 or 10 folds, with k=10 being widely recommended as a standard default [11] [13] [15]. With k=10, the model is trained on 90% of the data and validated on the remaining 10% in each iteration, striking a practical balance between computational expense and reliable performance estimation [11]. As k increases, the bias of the estimate decreases because each training set more closely resembles the full dataset, but the variance may increase due to higher correlation between the training sets [13] [12]. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) represents an extreme case where k equals the number of observations, providing an almost unbiased but potentially high-variance estimate that is computationally prohibitive for large datasets [13] [15].

Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation

Repeated k-fold cross-validation extends the standard approach by performing multiple iterations of k-fold cross-validation with different random partitions of the data into folds [10] [13]. For example, a 10-fold cross-validation repeated 5 times would generate 50 performance estimates (10 folds × 5 repeats) that are then aggregated to produce a final, more stable performance measure [15]. This approach addresses a key limitation of standard k-fold: the potential for variability in performance estimates based on a single, potentially fortunate or unfortunate, random partition of the data [10].

The primary advantage of repeated k-fold cross-validation lies in its ability to reduce variance in the performance estimate and provide a more reliable measure of model performance [10] [13]. By averaging across multiple random splits, the influence of any particularly favorable or unfavorable data partition is diminished, yielding a more robust estimation of how the model would perform on truly unseen data [13]. This comes at the obvious cost of increased computational requirements, as the model must be trained and evaluated multiple times compared to standard k-fold [13]. However, for medium-sized datasets typical in early drug discovery, this additional computational investment often pays dividends through more reliable model selection [15].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Cross-Validation Methods

| Characteristic | K-Fold Cross-Validation | Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Data split into k folds; each fold serves as validation set once | Multiple runs of k-fold with different random splits |

| Performance Estimate | Average of k validation scores | Average of (k × number of repeats) scores |

| Variance of Estimate | Moderate | Lower due to averaging across repetitions |

| Computational Cost | Lower (k model trainings) | Higher (k × number of repetitions model trainings) |

| Best Application Context | Large datasets, initial model screening | Medium-sized datasets, final model evaluation |

Comparative Analysis in Research Contexts

Performance and Stability Comparison

Direct comparisons between k-fold and repeated k-fold cross-validation reveal meaningful differences in their performance characteristics, particularly regarding stability and reliability. In a comprehensive study comparing cross-validation techniques across multiple machine learning models, repeated k-fold demonstrated distinct advantages in certain scenarios [13]. When applied to imbalanced datasets without parameter tuning, repeated k-fold cross-validation achieved a sensitivity of 0.541 and balanced accuracy of 0.764 for Support Vector Machines, showing robust performance despite the class imbalance [13]. Standard k-fold cross-validation, in contrast, showed higher variance across different models, with sensitivity ranging from 0.784 for Random Forest but with notable fluctuations in precision metrics [13].

The stability advantage of repeated k-fold becomes particularly evident in scenarios with limited data or high-dimensional feature spaces, both common characteristics in phenotypic screening research [9] [13]. One study noted that "repeated k-folds cross-validation enhances the reliability by providing the average of several results" but appropriately noted the accompanying increase in computational requirements [13]. This tradeoff between reliability and computational expense must be carefully considered based on the specific research context and resources.

Application to Phenotypic Screening Data

The application of these validation methods in phenotypic screening research demonstrates their practical importance in drug discovery. A notable study published in Nature Communications applied 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate predictors of compound activity using chemical structures, morphological profiles from Cell Painting, and gene expression profiles from the L1000 assay [9]. The researchers used scaffold-based splits during cross-validation, ensuring that structurally dissimilar compounds were placed in training versus validation sets, thus providing a more challenging and realistic assessment of model generalizability [9].

This study revealed that morphological profiles could predict 28 assays individually, compared to 19 for gene expression and 16 for chemical structures when using a high-accuracy threshold (AUROC > 0.9) [9]. More importantly, the combination of these data modalities through late fusion approaches predicted 31 assays with high accuracy – nearly double the best single modality – demonstrating how cross-validation helps identify complementary information sources in phenotypic screening [9]. Without robust validation methods like k-fold cross-validation, such insights into modality complementarity would be less reliable, potentially leading to suboptimal resource allocation in assay development.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Phenotypic Screening Applications

| Validation Scenario | Data Modality | Performance (AUROC > 0.9) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Modality K-Fold | Chemical Structures | 16 assays | Baseline performance |

| Single Modality K-Fold | Morphological Profiles | 28 assays | Highest individual predictor |

| Single Modality K-Fold | Gene Expression | 19 assays | Intermediate performance |

| Fused Modalities K-Fold | Chemical + Morphological | 31 assays | Near-additive improvement |

| Lower Threshold (AUROC > 0.7) | All Combined | 64% of assays | Useful for early screening |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard K-Fold Cross-Validation Protocol

Implementing k-fold cross-validation requires careful attention to data partitioning and model evaluation procedures. The following protocol outlines the key steps for proper implementation in a phenotypic screening context:

Data Preparation: Begin with a complete dataset of compound profiles, including features (e.g., chemical descriptors, morphological profiles) and assay outcomes. For phenotypic data, ensure proper normalization and batch effect correction [9].

Fold Creation: Randomly partition the data into k folds (typically k=5 or 10), ensuring that each fold maintains similar distribution of important characteristics. For imbalanced datasets, use stratified k-fold to preserve class distribution in each fold [11] [12].

Model Training and Validation: For each fold i (i = 1 to k):

- Use folds {1, 2, ..., i-1, i+1, ..., k} as training data

- Use fold i as validation data

- Train model on training set

- Calculate performance metrics on validation set

Performance Aggregation: Compute the average and standard deviation of performance metrics across all k folds [11] [14].

For datasets with compound structures, use scaffold-based splitting instead of random splitting to group compounds with similar structural frameworks, providing a more challenging test of model generalizability to novel chemotypes [9].

Diagram 1: K-Fold Cross-Validation Workflow

Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation Protocol

The protocol for repeated k-fold cross-validation extends the standard approach with additional iterations:

Initial Setup: Determine the number of repeats (r) – commonly 3 to 10 repetitions – in addition to the number of folds (k) [13] [15].

Data Partitioning Iterations: For each repetition j (j = 1 to r):

- Randomly reshuffle the entire dataset

- Partition the shuffled data into k folds

- Perform standard k-fold cross-validation as described in section 4.1

Comprehensive Evaluation: After all repetitions, collect all k × r performance estimates [13].

Statistical Summary: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of all performance estimates to obtain the final model assessment with confidence intervals [10] [13].

This approach is particularly valuable for medium-sized datasets where a single random split might yield misleading results due to the specific composition of the folds [15]. The multiple repetitions help average out this randomness, providing a more stable performance estimate [10].

Advanced Considerations for Research Applications

Nested Cross-Validation for Hyperparameter Optimization

When performing both model selection and hyperparameter tuning, standard k-fold cross-validation can produce optimistically biased performance estimates due to information leakage between training and validation phases [16] [12]. Nested cross-validation addresses this issue by implementing two layers of cross-validation: an inner loop for parameter optimization and an outer loop for performance estimation [16] [12].

In the context of phenotypic screening, this approach might involve using the inner loop to optimize parameters for predicting assay outcomes from morphological profiles, while the outer loop provides an unbiased estimate of how well this tuning process generalizes to new compounds [9]. Although computationally intensive, nested cross-validation provides the most reliable performance estimates when both model selection and hyperparameter tuning are required [12].

Specialized Cross-Validation for Phenotypic Data

Phenotypic screening data often possesses unique characteristics that necessitate specialized validation approaches:

Temporal Validation: For time-series phenotypic data, standard random splitting may be inappropriate. Instead, use forward-chaining validation where models are trained on earlier timepoints and validated on later ones [12].

Plate Effects Correction: In high-content screening, plate-based artifacts can confound models. Implement plate-wise cross-validation where all wells from particular plates are held out together to ensure models generalize across plating variations [9].

Concentration Response Relationships: For datasets with multiple compound concentrations, ensure that all concentrations of a particular compound reside in the same fold to prevent information leakage [9].

Diagram 2: Nested Cross-Validation Structure

The Researcher's Toolkit

Implementing robust cross-validation in phenotypic screening requires both specialized software and thoughtful experimental design:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Cross-Validation in Phenotypic Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Approaches | Application in Phenotypic Research |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Frameworks | Python scikit-learn, R caret | Provide built-in functions for k-fold and repeated k-fold validation [17] [11] |

| Specialized Validation | Stratified k-fold, Scaffold splitting | Maintains class balance or chemical diversity across folds [9] [12] |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel processing, Cloud resources | Accelerates repeated k-fold and nested cross-validation [13] |

| Performance Metrics | AUROC, Sensitivity, Precision | Comprehensive assessment for imbalanced screening data [13] |

| Data Modalities | Chemical, Morphological, Gene Expression | Multi-modal predictor fusion improves performance [9] |

K-fold and repeated k-fold cross-validation represent sophisticated approaches to model validation that address critical limitations of simple holdout methods in phenotypic screening research. While standard k-fold offers a practical balance between computational efficiency and reliable performance estimation, repeated k-fold provides enhanced stability through averaging across multiple data partitions – a particularly valuable characteristic when working with the complex, multidimensional datasets typical in drug discovery.

The choice between these methods should be guided by dataset characteristics, computational resources, and the specific stage of the research process. For initial model screening and feature selection, standard k-fold often suffices, while repeated k-fold becomes more valuable for final model evaluation and comparison. Ultimately, the implementation of these robust validation methods helps build greater confidence in predictive models, supporting more informed decision-making in the resource-intensive journey of drug discovery.

As phenotypic screening continues to evolve with increasingly complex assay technologies and data modalities, rigorous validation approaches like k-fold and repeated k-fold cross-validation will remain essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional data and translating these insights into successful therapeutic candidates.

The transition from first-in-class (FIC) drug discovery to clinical success hinges on reducing attritions rates that have traditionally plagued the pharmaceutical industry. While traditional drug discovery methods often suffer from validation gaps that become apparent only during costly late-stage clinical trials, emerging approaches that integrate rigorous cross-validation (CV) throughout the discovery pipeline are demonstrating significantly improved outcomes. This guide compares traditional, AI-integrated, and multi-method validation approaches, examining how strategic implementation of cross-validation frameworks directly impacts the viability of novel therapeutic programs. The analysis focuses on practical implementation across different discovery paradigms, providing researchers with actionable insights for strengthening their validation strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Discovery Approaches with Validation Rigor

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Drug Discovery Validation Approaches

| Discovery Approach | Target Identification Method | Validation Framework | Reported Success Rate | Development Timeline | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Discovery | Experimental methods (SILAC, CRISPR-Cas9) [18] | Sequential validation (biology → chemistry) | ~15.4% (84.6% failure rate) [18] | ~10 years [18] | Established methodology; Direct experimental evidence | High resource consumption; Validation gaps between stages; Susceptible to information leakage [19] |

| AI-Integrated Discovery (Insilco Medicine) | PandaOmics AI platform (multi-omics analysis + NLP) [20] [18] | Integrated biological and chemical validation | 90% clinical success for AI-identified candidates [21] | 18 months to PCC nomination [20] | Rapid hypothesis generation; Simultaneous target and molecule validation | Black box concerns; Training data dependencies; Limited clinical track record |

| Multi-Method Validation (Osteoarthritis Study) | DEGs from GEO database + aging-related genes [22] | Three machine learning methods (LASSO, SVM-RFE, RF) with cross-validation | AUC >0.8 for all 5 identified biomarkers [22] | Not specified | Redundant validation; Minimized overfitting; Clinically validated biomarkers | Computational complexity; Requires substantial training data |

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Validation

AI-Driven Target Discovery and Validation Protocol (Insilco Medicine)

The following workflow illustrates the integrated AI-driven discovery and validation process:

Protocol Details:

- Multi-omics Data Integration: Collect and process transcriptomics, proteomics, and genomics data from disease-relevant samples [18]

- Target Identification: Utilize PandaOmics' 20+ prediction models and natural language processing to analyze millions of data points from research publications, patents, and clinical trials [20]

- Compound Generation: Employ Chemistry42 generative chemistry platform to design novel small molecules targeting identified proteins [20]

- Biological Validation: Conduct iterative testing using human patient cells, tissues, and animal models to confirm efficacy and safety [20]

- Key Performance Metrics: Design and synthesize <80 molecules to achieve clinical candidate nomination, significantly higher than industry standards [20]

Multi-Method Machine Learning Validation Protocol (Osteoarthritis Biomarkers)

The following workflow illustrates the multi-method machine learning validation process:

Protocol Details:

- Data Sourcing and Integration: Obtain young OA and elderly OA microarray gene profiles from GEO database; collect aging-related genes (ARGs) from Human Aging Genome Resource (HAGR) [22]

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify DEGs between young and elderly OA patients using limma R package with adj.P<0.05 and |log2FC|≥1 as thresholds [22]

- Multi-Method Machine Learning Validation:

- LASSO Regression: Implement using glmnet R package with α=1, determining optimal λ through 5-fold cross-validation [22]

- SVM-RFE: Execute using e1071 R package with recursive feature elimination to identify optimal variables [22]

- Random Forest: Run with 500 decision trees, selecting features with relative importance >1 [22]

- Clinical Correlation: Validate identified biomarkers in 60 patient samples (20 normal, 20 young OA, 20 elderly OA) measuring CRP, ESR, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6 levels and performing qRT-PCR for gene expression [22]

The Impact of Proper Cross-Validation Frameworks

Consequences of Validation Missteps

Table 2: Impact of Cross-Validation Strategies on Model Performance

| Validation Approach | Information Leakage Risk | Generalizability to New Data | Reported Clinical Translation Success | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Feature Screening | High - features selected using entire dataset [19] | Poor - performance drops with new datasets [19] | Not reported; high clinical failure rates | Traditional differential expression analysis [19] |

| Internal CV (Nested) | Minimal - features selected within each fold [19] | Excellent - maintains performance with new data [19] | Higher success in clinical validation [22] | Multi-method ML approaches [22] |

| Integrated AI Validation | Low - continuous validation across pipeline [20] | Promising - early clinical successes reported [20] [18] | ISM001-055 advancing to Phase II trials [18] | AI-driven discovery platforms [20] [18] |

Implementation Guidelines for Proper Cross-Validation

The fundamental principle underlying rigorous cross-validation is preventing information leakage between training and testing phases. Traditional approaches that conduct feature selection prior to data splitting inherently leak global information about the dataset into what should be an independent testing process [19]. This creates models that appear highly accurate during development but fail to generalize to new clinical samples.

Critical Implementation Considerations:

- Internal Feature Selection: Conduct all feature selection steps (differential gene expression, pathway analysis) within each cross-validation fold using only training data [19]

- Independent Test Sets: Maintain completely independent validation sets that never participate in any aspect of model training or feature selection

- Multi-Dataset Validation: Test identified targets or biomarkers across diverse patient cohorts and experimental conditions to confirm generalizability [22]

- Clinical Correlation: Early and continuous correlation with clinical parameters and phenotypes to ensure biological relevance [22]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Cross-Validation Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PandaOmics Platform | AI-driven target discovery [20] [18] | Multi-omics integration and target prioritization | Identification of novel targets for IPF [20] |

| Chemistry42 | Generative chemistry compound design [20] | De novo molecular generation against novel targets | Design of small molecule inhibitors for AI-identified targets [20] |

| LASSO Regression (glmnet) | Feature selection with regularization [22] | Identification of most predictive biomarkers from high-dimensional data | Selection of core osteoarthritis biomarkers from 45 candidates [22] |

| SVM-RFE Algorithm | Recursive feature elimination [22] | Ranking feature importance and optimal subset selection | Identification of OA inflamm-aging biomarkers [22] |

| Random Forest with RFE | Ensemble-based feature selection [22] | Determining feature importance through multiple decision trees | Validation of robust osteoarthritis biomarkers [22] |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Gene expression quantification [22] | Clinical validation of identified biomarkers in patient samples | Confirmation of FOXO3, MCL1, SIRT3 expression patterns [22] |

| ELISA Kits | Protein level quantification [22] | Measurement of SASP factors and inflammatory markers | Detection of IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6 in patient serum [22] |

The evidence from multiple drug discovery paradigms demonstrates that rigorous cross-validation is not merely a technical formality but rather the critical bridge connecting novel target discovery to clinical success. Traditional approaches that treat validation as a discrete downstream step consistently demonstrate higher failure rates, while integrated validation frameworks—whether through AI-platforms or multi-method machine learning—show markedly improved outcomes. The key differentiator for first-in-class drug success appears to be the systematic implementation of validation throughout the entire discovery pipeline, from initial target identification through compound design and clinical testing. As pharmaceutical research continues to tackle increasingly complex diseases, this integrated validation mindset will be essential for translating novel biological insights into transformative medicines for patients.

In the field of machine learning for drug discovery, the method used to split data into training and test sets profoundly impacts the reliability and real-world applicability of predictive models. Data splitting strategies serve as the foundational framework for benchmarking artificial intelligence (AI) models in virtual screening (VS) and molecular property prediction. Traditional random splitting approaches often lead to overly optimistic performance estimates because structurally similar molecules frequently appear in both training and test sets, creating an artificial scenario that fails to represent the true chemical diversity encountered in real-world screening libraries [23]. This disconnect between benchmark performance and prospective utility represents a significant challenge in computational drug discovery, particularly in phenotypic screening research where generalizability to novel chemical structures is paramount.

The core issue lies in information leakage—when models perform well on test data because they have encountered highly similar structures during training, rather than learning generalizable structure-activity relationships. Recent studies have demonstrated that this problem pervades biomedical machine learning research, leading to inflated performance metrics and overoptimistic conclusions about model capabilities [24]. When similarity between training and test sets exceeds the similarity between training data and the compounds researchers actually intend to screen, models appear to perform well during evaluation but generalize poorly to真正的 deployment scenarios [25]. This review systematically compares prevalent data splitting methodologies, evaluates their effectiveness at mitigating information leakage, and provides experimental evidence to guide researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for robust model evaluation in phenotypic screening contexts.

Data Splitting Methodologies: Mechanisms and Implementation

Common Splitting Strategies

Multiple data splitting strategies have been developed to create more realistic evaluation scenarios for AI models in drug discovery. Each method employs a distinct mechanism for partitioning data, with varying degrees of chemical rationale and computational complexity.

Random Splits: The most straightforward approach involves randomly assigning molecules to training and test sets, typically with 70-80% of data用于训练 and the remainder for testing [26]. While simple to implement, this method frequently places structurally similar molecules in both sets, leading to potential information leakage and overoptimistic performance assessments [23].

Scaffold Splits: This strategy groups molecules by their core Bemis-Murcko scaffolds, ensuring that molecules sharing the same scaffold are assigned to the same set [23]. By forcing models to predict properties for molecules with entirely different core structures from those seen during training, scaffold splits provide a more challenging evaluation scenario. However, a significant limitation exists: molecules with different scaffolds can still be highly chemically similar if their scaffolds differ by only a single atom or if one scaffold is a substructure of the other [23] [26].

Butina Clustering Splits: This approach clusters molecules based on structural similarity using molecular fingerprints and the Butina clustering algorithm implemented in RDKit [26]. Molecules within the same cluster are assigned to the same data fold, creating more chemically distinct partitions between training and test sets than scaffold-based approaches [23].

UMAP-based Clustering Splits: This method projects molecular fingerprints into a lower-dimensional space using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), then performs agglomerative clustering on the reduced representations to generate structurally dissimilar clusters [23] [26]. By maximizing inter-cluster molecular dissimilarity, UMAP splits introduce more realistic distribution shifts that better mimic the chemical diversity encountered in real-world screening libraries like ZINC20 [23].

DataSAIL Splits: DataSAIL formulates leakage-reduced data splitting as a combinatorial optimization problem, solved using clustering and integer linear programming [24]. This approach can handle both one-dimensional (e.g., molecular property prediction) and two-dimensional datasets (e.g., drug-target interaction prediction) while minimizing similarity-based information leakage [24].

Technical Implementation Workflows

The implementation of advanced splitting strategies typically follows structured workflows. The diagram below illustrates the generalized process for similarity-based splitting methods:

For scaffold-based splitting approaches, the process differs slightly but follows the same general principle of creating chemically distinct partitions:

In practice, implementations often leverage existing computational chemistry toolkits. For example, scaffold splitting can be implemented using RDKit's Bemis-Murcko method, while Butina clustering also utilizes RDKit's clustering capabilities [26]. The scikit-learn package's GroupKFold method can then be employed to ensure molecules from the same group (scaffold or cluster) are not split between training and test sets [26].

Comparative Performance Analysis Across Splitting Methods

Quantitative Benchmarking Results

Rigorous evaluation across multiple datasets and AI models reveals significant performance differences when employing various splitting strategies. A comprehensive study examining four representative AI models across 60 NCI-60 datasets, each comprising approximately 33,000–54,000 molecules tested on different cancer cell lines, demonstrated clear stratification of model performance based on splitting methodology [23]. The table below summarizes the key findings from this large-scale benchmarking effort:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models Across Different Data Splitting Methods

| Splitting Method | Relative Challenge Level | Model Performance Assessment | Similarity Between Train/Test Sets | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Split | Least Challenging | Overoptimistic, inflated | High similarity | Baseline comparisons |

| Scaffold Split | Moderately Challenging | Still overly optimistic | Moderate similarity | Initial model screening |

| Butina Clustering | Challenging | More realistic assessment | Lower similarity | Intermediate evaluation |

| UMAP-based Clustering | Most Challenging | Most realistic assessment | Lowest similarity | Final model validation |

The same study trained a total of 8,400 models using Linear Regression, Random Forest, Transformer-CNN, and GEM algorithms, evaluating them under four different splitting methods [23]. Results demonstrated that UMAP splits provide the most challenging and realistic benchmarks for model evaluation, followed by Butina splits, then scaffold splits, with random splits proving least challenging [23]. This performance hierarchy highlights how conventional splitting methods fail to adequately capture the chemical diversity challenges present in real-world virtual screening applications.

Structural Similarity Analysis

The fundamental issue driving performance differences between splitting methods lies in the structural similarity preserved between training and test sets. Scaffold splitting, while ensuring different core structures, often groups dissimilar molecules together while separating highly similar compounds:

Table 2: Structural Relationships in Different Splitting Methods

| Splitting Method | Similarity Within Splits | Similarity Between Splits | Ability to Separate Analogues | Chemical Space Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Split | High | High | Poor | Represents dataset well |

| Scaffold Split | Variable | Moderate to High | Limited (separates same scaffold) | Can be biased |

| Butina Clustering | High within clusters | Lower than scaffold | Better than scaffold | Depends on threshold |

| UMAP-based Clustering | High within clusters | Lowest | Best among methods | Most comprehensive |

The limitation of scaffold splits becomes evident when considering that "molecules with different chemical scaffolds are often similar because such non-identical scaffolds often only differ on a single atom, or one may be a substructure of the other" [23]. This observation has crucial implications for model evaluation, as it means scaffold splits may not adequately prevent similarity-based information leakage.

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Evaluation

Benchmarking Framework Design

To conduct meaningful comparisons of splitting methodologies, researchers should implement standardized benchmarking protocols. A robust framework includes the following components:

Dataset Selection: Utilize diverse molecular datasets with varying sizes and structural diversity. The NCI-60 dataset, comprising 33,118 unique molecules across 60 cancer cell lines with 1,764,938 pGI50 determinations (88.8% completeness), provides an excellent benchmark due to its scale and diversity [23].

Model Representation: Include multiple AI model architectures with different inductive biases. The comprehensive study referenced earlier employed Linear Regression, Random Forest, Transformer-CNN, and GEM models to ensure findings were not architecture-specific [23].

Evaluation Metrics: Move beyond ROC AUC, which is misaligned with virtual screening goals as early-recognition performance only makes a small contribution to this metric [23]. Instead, prioritize hit rate or similar early-recognition metrics that better reflect VS objectives. Implement a binarization approach that defines the top 100-ranked molecules as positive predictions to mimic prospective VS tasks where purchasing many molecules for in vitro testing is prohibitive [23].

Cross-Validation Strategy: Employ multi-fold cross-validation with consistent cluster assignments. For UMAP splits, merge predictions from all held-out folds before calculating metrics rather than simply averaging results from different folds [23].

Implementation Considerations

Practical implementation of advanced splitting methods requires attention to several technical details:

Fingerprint Selection: Morgan fingerprints with radius 2 and 2048 bits provide a robust molecular representation for similarity calculations and UMAP projection [26].

Cluster Optimization: For UMAP-based splitting, the number of clusters significantly impacts test set size variability. Evidence suggests that test set size becomes less variable when the number of clusters exceeds 35 [26].

Stratification: Maintain consistent distribution of important molecular properties (e.g., activity, molecular weight) across splits when possible, though this must be balanced against the primary goal of creating chemically distinct partitions.

The following workflow illustrates the comprehensive experimental protocol for comparing splitting methodologies:

Implementation of robust data splitting strategies requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table catalogues key research reagents and their applications in methodological implementation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Data Splitting Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Chemical informatics and machine learning | Scaffold extraction, fingerprint generation, Butina clustering |

| scikit-learn | Software Library | Machine learning utilities | GroupKFold implementation, agglomerative clustering, model training |

| UMAP | Algorithm | Dimension reduction | Projecting molecular fingerprints for clustering |

| DataSAIL | Python Package | Leakage-reduced data splitting | Optimization-based splitting for 1D and 2D datasets |

| NCI-60 Dataset | Benchmark Data | Experimental bioactivity data | Evaluation of splitting methods across diverse chemical space |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Molecular Representation | Capturing molecular features | Structural similarity calculation for clustering |

These tools collectively enable researchers to implement and compare the full spectrum of data splitting methodologies, from basic scaffold splits to advanced UMAP-based approaches. RDKit provides essential cheminformatics functionality for scaffold analysis and fingerprint generation [26], while scikit-learn's GroupKFold implementation facilitates the actual data partitioning [26]. DataSAIL offers a specialized solution for scenarios requiring rigorous prevention of information leakage, particularly for complex data types like drug-target interactions [24].

Implications for Phenotypic Screening Research

The choice of data splitting strategy has particularly significant implications for phenotypic screening research, where models often integrate multiple data modalities including chemical structures, morphological profiles (Cell Painting), and gene expression profiles (L1000) [9]. Studies have demonstrated that combining phenotypic profiles with chemical structures improves assay prediction ability—adding morphological profiles to chemical structures increased the number of well-predicted assays from 16 to 31 compared to chemical structures alone [9].

However, the benefits of multimodal integration can be misrepresented if improper data splitting strategies are employed. Scaffold-based splits, while improving upon random splits, may still overestimate model generalizability in phenotypic screening contexts. The more rigorous separation provided by UMAP-based splits or DataSAIL offers a more realistic assessment of how models will perform when presented with truly novel chemical matter in prospective screening campaigns.

Furthermore, the field must address the critical issue of coverage bias in small molecule machine learning [27]. Many widely-used datasets lack uniform coverage of biomolecular structures, limiting the predictive power of models trained on them [27]. Without representative data coverage, even sophisticated splitting strategies cannot ensure model generalizability across diverse chemical spaces.

The rigorous evaluation of AI models for drug discovery requires data splitting strategies that accurately reflect the challenges of real-world virtual screening. While scaffold splits represent an improvement over random splits, evidence now clearly demonstrates that they still introduce substantial similarities between training and test sets, leading to overestimated model performance [23]. Butina clustering provides more challenging benchmarks, while UMAP-based clustering splits currently offer the most realistic assessment for molecular property prediction.

Future methodological development should focus on several key areas: (1) improving computational efficiency of sophisticated splitting methods to accommodate gigascale chemical spaces; (2) developing standardized benchmarking protocols that all studies can adopt for fair model comparison; (3) creating domain-specific splitting strategies that account for multimodal data integration in phenotypic screening; and (4) establishing guidelines for matching splitting strategy to specific application contexts.

As the field progresses, researchers should transparently report the data splitting methodologies employed and justify their selection based on the intended application context. By adopting more rigorous evaluation practices, the drug discovery community can develop AI models with truly generalizable predictive capabilities, ultimately accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic compounds.

Implementing Cross-Validation: From Standard k-Fold to Advanced Phenotypic Protocols

In drug discovery, accurately predicting compound bioactivity from phenotypic profiles and chemical structures is paramount. The choice of how to validate these predictive models—k-fold cross-validation, Leave-One-Out cross-validation, or bootstrap methods—directly impacts the reliability of performance estimates and the confidence in subsequent hit-prioritization decisions. These internal validation techniques help quantify model optimism and prevent overfitting, a critical consideration when working with the high-dimensional, multi-modal datasets typical in modern phenotypic screening [28] [9] [29]. This guide objectively compares these strategies within the context of cross-validation for phenotypic screening results, providing researchers with the data and protocols needed to select an optimal approach.

Cross-Validation Strategy Comparison

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary validation strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of k-Fold, Leave-One-Out, and Bootstrap Validation Methods

| Feature | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) | Bootstrap Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Randomly partition data into k equal-sized folds; iteratively use k-1 folds for training and the remaining 1 for testing [28] [29]. | For n samples, create n folds; each iteration uses a single sample as the test set and the remaining n-1 for training [30] [29]. | Repeatedly draw random samples with replacement from the original dataset to create training sets, with the non-selected samples forming test sets [31] [32]. |

| Typical Number of Iterations | k times (common values: k=5 or k=10) [33]. | n times (equal to the total number of data points) [30]. | Arbitrary number of bootstrap samples (e.g., 200 or 1000) [32]. |

| Best-Suited Data Scenarios | General-purpose; works well with most dataset sizes, particularly moderate to large [33]. | Very small datasets (e.g., <50 samples) where maximizing training data is critical [30]. | Clustered data or for estimating confidence intervals of model performance [32]. |

| Key Advantages | Good balance of bias-variance trade-off; reduced computational cost compared to LOOCV; robust performance estimate [28] [33]. | Low bias; uses maximum data for training in each iteration; deterministic results for a given dataset [30]. | Useful for assessing optimism and stability of model parameters; effective with clustered data when resampling on the cluster level [32]. |

| Key Limitations / Risks | Higher variance in estimate with small k; results can depend on the random partitioning of folds [33]. | Computationally expensive for large n; high variance in the performance estimate due to correlated training sets [30] [29]. | Can produce overoptimistic estimates with high-dimensional or complex non-linear models [31]. |

| Impact on Performance Estimate | Provides an averaged performance metric (e.g., AUC, RMSE) across k folds, offering a stable estimate [28] [33]. | Final performance metric is the average of n iterations; can be almost unbiased for AUC estimation in certain cases [31]. | Can be used to compute optimism-corrected performance estimates (e.g., .632 or .632+ bootstrap) [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation in Phenotypic Screening

The methodologies below are adapted from real-world studies that rigorously evaluated predictors for compound bioactivity, highlighting the application of different validation techniques.

Protocol 1: Large-Scale Assay Prediction with k-Fold Cross-Validation

This protocol is derived from a large-scale study published in Nature Communications that integrated chemical structures (CS), morphological profiles (MO) from Cell Painting, and gene-expression profiles (GE) from L1000 to predict bioactivity in 270 assays [9].

- Dataset Curation: Compile a complete matrix of experiment-derived profiles for all compounds. The referenced study used 16,170 compounds with CS, MO, and GE profiles, tested in 270 assays for 585,439 total readouts [9].

- Assay Selection: Filter assays to reduce similarity, ensuring a representative set not selected based on metadata to avoid bias [9].

- Model Training with Scaffold Split: To rigorously evaluate the model's ability to generalize to novel chemical structures, implement a 5-fold cross-validation scheme using scaffold-based splits. This ensures that compounds in the test set have dissimilar chemical structures (different molecular scaffolds) to those in the training set, preventing over-optimism from evaluating structurally analogous compounds [9].

- Performance Evaluation: Train assay predictors (e.g., using multi-task settings or graph convolutional nets) and evaluate them on the held-out folds. The primary evaluation metric in the cited study was the count of assays predicted with high accuracy (AUROC > 0.9). The performance measure reported is the average of the values computed across the k folds [9].

- Data Fusion for Multi-Modal Profiles: To combine predictions from different data modalities (e.g., CS, MO, GE), use a late data fusion strategy. This involves building assay predictors for each modality independently and then combining their output probabilities, for instance, via max-pooling. The cited study found this superior to early fusion (feature concatenation) [9].

Protocol 2: Leave-Pair-Out Cross-Validation for Unbiased AUC Estimation

For binary classification tasks, particularly with small sample sizes, standard cross-validation methods like LOO can be biased for Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) estimation. Leave-Pair-Out (LPO) cross-validation is a specialized, nearly unbiased method recommended for this purpose [31].

- Problem Formulation: Define the binary classification task, such as discriminating between active and inactive compounds in a specific assay.

- LPO Iteration: For every possible pair of samples consisting of one positive unit (e.g., an active compound) and one negative unit (e.g., an inactive compound), train a model on all data except this specific pair.

- Pairwise Comparison: Use the trained model to predict the held-out pair. Apply the Heaviside step function, ( H(a) ), to the difference in predictions for the positive and negative sample: ( H(f(i) - f(j)) ), where a result of 1 is assigned if the positive unit is ranked higher, 0.5 if tied, and 0 otherwise [31].

- AUC Calculation: The final AUC estimate is calculated as the average of these pairwise comparison results across all positive-negative pairs, equivalent to the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney statistic [31]. ( \hat{A}(f) = \frac{1}{|I^+||I^-|} \sum{i \in I^+} \sum{j \in I^-} H(f(i) - f(j)) )

- Tournament LPO (TLPO) for ROC Curves: To enable full ROC analysis while preserving the unbiased nature of LPO, use Tournament LPO. This method creates a tournament from the paired comparisons to produce a ranking for all data points, allowing for the plotting and analysis of ROC curves [31].

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

k-Fold Cross-Validation for Assay Data

Multi-Modal Data Fusion with Scaffold Split

Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiment

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Modal Phenotypic Screening

| Item / Solution | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | A high-content, image-based morphological profiling assay that uses up to six fluorescent dyes to label key cellular components, generating rich phenotypic profiles for each compound [9] [7]. |

| L1000 Assay | A high-throughput gene expression profiling technology that measures the expression of ~1,000 landmark genes, used to create transcriptomic profiles for compounds [9]. |

| Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) | A type of deep learning model used to compute informative numerical representations (profiles) directly from the chemical structure of compounds [9]. |

| Late Data Fusion (e.g., Max-Pooling) | A computational strategy to combine predictions from models trained on different data modalities (CS, MO, GE) by integrating their output probabilities, which was found to outperform simple feature concatenation [9]. |

| Scaffold-Based Splitting | A data partitioning method used during cross-validation that groups compounds by their core molecular structure, ensuring that the model is tested on chemically novel compounds and provides a more realistic performance estimate [9]. |

In artificial intelligence-driven drug discovery, a model's perceived performance is only as robust as the strategy used to evaluate it. Scaffold-based splits have emerged as a crucial methodological approach for assessing a model's ability to generalize to novel chemical structures. This method groups molecules by their core molecular frameworks (scaffolds) and ensures that compounds sharing a scaffold are contained within the same training or test set, thereby forcing models to predict activities for structurally distinct compounds never encountered during training [23] [34]. This approach directly addresses a fundamental challenge in drug discovery: the reality that virtual screening libraries contain vastly diverse compounds, and successful models must identify active molecules from entirely new structural classes [23]. The practice is particularly vital during the lead optimization stage, where understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) across different chemical series is paramount [34].

However, the field is undergoing a significant evolution. Recent comprehensive studies reveal that while scaffold splits provide a more challenging evaluation than simple random splits, they may still overestimate real-world performance because molecules with different scaffolds can remain structurally similar [23]. This article provides a comparative analysis of scaffold-based splitting against emerging alternatives, examining its role not in isolation, but within the broader context of creating predictive models that genuinely translate to successful prospective compound identification.

Comparative Analysis of Data Splitting Strategies

The choice of how to partition a chemical dataset into training and test sets fundamentally influences the reported performance of a predictive model. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the primary data splitting strategies used in the field.

Table 1: Comparison of Data Splitting Strategies in Molecular Property Prediction

| Splitting Method | Core Principle | Reported Performance (Typical AUROC Drop vs. Random) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Split | Compounds assigned randomly to train/test sets. | Baseline (0% drop) | Simple to implement; Maximizes data usage. | Severe overestimation of real-world performance; Structurally similar molecules leak between sets. [23] |

| Scaffold Split | Groups molecules by Bemis-Murcko scaffold; different scaffolds in train/test sets. [23] [34] | Moderate drop | More realistic than random splits; Tests inter-scaffold generalization. [23] [35] | May overestimate performance; different scaffolds can be structurally similar. [23] |

| Butina Clustering Split | Clusters molecules by fingerprint similarity; whole clusters assigned to sets. [23] | Larger drop than Scaffold Split | Higher train-test dissimilarity than scaffold splits. | May not fully capture the chemical diversity of gigascale libraries like ZINC20. [23] |

| UMAP-Based Clustering Split | Uses UMAP dimensionality reduction and clustering to maximize train-test dissimilarity. [23] | Largest drop | Provides the most challenging and realistic benchmark; best simulates screening diverse libraries. [23] | Computationally more intensive; requires careful parameter selection. |

The data from comparative benchmarks paints a clear picture: as the splitting strategy becomes more rigorous, the reported model performance drops accordingly. A systematic study of AI methods for predicting cyclic peptide permeability found that models validated via the more rigorous scaffold split exhibited lower generalizability compared to random splits [35]. This counterintuitive result was attributed to the reduced chemical diversity in the training data after stringent splitting, highlighting a key trade-off.

Pushing the boundary further, a 2025 study introduced UMAP-based clustering splits, arguing that even scaffold and Butina splits are not realistic enough. This method aims to most closely mirror the chemical dissimilarity between historical training compounds and novel, gigascale screening libraries. The study found that UMAP splits provide the most challenging evaluation, followed by Butina, then scaffold splits, with random splits being the most optimistic [23]. This establishes a new benchmark for what constitutes a realistic assessment of model utility in prospective virtual screening.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

Implementation of a Standard Scaffold Split

The standard protocol for a scaffold-based split involves a series of reproducible steps to ensure distinct scaffolds are separated between training and test sets. The following workflow outlines this general process, as implemented in tools like the splito library [34]:

Diagram 1: Scaffold Split Workflow

The methodology can be summarized as follows:

- Input Preparation: Begin with a dataset of molecules, typically represented by their Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings.

- Scaffold Generation: For each molecule, compute its Bemis-Murcko scaffold. This process involves removing all non-ring side chains and retaining only the ring systems and the linker atoms that connect them [23].

- Grouping: Group all molecules that share an identical scaffold.

- Partitioning: Assign entire groups of molecules (scaffolds) to the training, validation, or test sets. A common practice is to sort scaffolds by frequency and assign the most common scaffolds to the training set to ensure it captures dominant chemical patterns, while the most diverse, rare scaffolds are assigned to the test set [35].

- Output: The final split datasets, where the test set contains molecules with scaffolds completely unseen during training.

Quantitative Benchmarking in Key Studies

The performance of predictive models is highly dependent on the splitting strategy, as shown by rigorous benchmarking across different domains and datasets.

Table 2: Performance Impact of Data Splitting Strategy in Cyclic Peptide Permeability Prediction

| Model Architecture | Molecular Representation | Random Split AUROC | Scaffold Split AUROC | Performance Drop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMPNN | Molecular Graph | 0.803 | 0.724 | -9.8% |

| Random Forest | Fingerprints (ECFP) | 0.792 | 0.715 | -9.7% |

| SVM | Fingerprints (ECFP) | 0.785 | 0.701 | -10.7% |

| Transformer-CNN | SMILES String | 0.776 | 0.693 | -10.7% |

Data adapted from the systematic benchmark of 13 AI methods for predicting cyclic peptide membrane permeability [35].

This comprehensive benchmark, which trained 13 different models on nearly 6000 cyclic peptides from the CycPeptMPDB database, consistently showed that scaffold splits lead to a substantial drop in the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) compared to random splits—approximately a 10% decrease on average [35]. This indicates that while models may appear highly accurate under optimistic splits, their ability to generalize to new scaffold classes is significantly lower.

Another large-scale study on the prediction of compound activity from phenotypic profiles and chemical structures utilized scaffold-based splits in its 5-fold cross-validation scheme. This evaluation aimed to "quantify the ability of the three data modalities to independently identify hits in the set of held-out compounds (which had compounds of dissimilar structures to the training set, to prevent learning assay outcomes for highly structurally similar compounds)" [9]. The study found that while chemical structures alone could predict 16 assays with high accuracy (AUROC > 0.9), combining them with morphological profiles (Cell Painting) increased the number of well-predicted assays to 31, demonstrating the power of data fusion even under rigorous evaluation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully implementing scaffold splits and building robust predictive models relies on a suite of computational tools and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics toolkit for generating molecular scaffolds, descriptors, and fingerprints. [23] [35] | Core component for scaffold computation and molecular representation in custom pipelines. |

| splito | Software Library | Dedicated Python library for implementing various chemical data splitting strategies, including scaffold splits. [34] | Simplifies and standardizes the creation of training/test sets based on scaffolds. |

| ECFP/FCFP | Molecular Representation | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints; circular fingerprints encoding molecular substructures. [36] | Used as model inputs and for calculating molecular similarity in clustering splits. |

| Cell Painting | Phenotypic Profiling Assay | High-content, image-based assay that provides unbiased morphological profiles of compound effects. [9] | Provides a complementary data modality to chemical structure for activity prediction. |

| L1000 | Gene Expression Profiling | High-throughput transcriptomic assay that measures the expression of 978 landmark genes. [9] | Provides gene-expression profiles that can be fused with chemical structures to improve prediction. |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

The principle of scaffold-based generalization is not only an evaluation tool but is increasingly being built into the core of model architecture and generation strategies. Emerging frameworks are tackling the challenge of structural imbalance, where certain active scaffolds dominate the training data, causing models to overlook active compounds with underrepresented scaffolds [37].

One novel approach, ScaffAug, is a scaffold-aware generative augmentation and reranking framework. It uses a graph diffusion model to generate new synthetic molecules conditioned on the scaffolds of known active compounds. Crucially, it employs a scaffold-aware sampling algorithm to produce more samples for active molecules with underrepresented scaffolds, thereby directly mitigating structural bias and helping models learn more comprehensive structure-activity relationships [37].

Similarly, in de novo molecular design, ScafVAE is a scaffold-aware variational autoencoder that generates molecules through a "bond scaffold-based" process. This approach first assembles a core scaffold structure before decorating it with specific atoms, effectively expanding the accessible chemical space while maintaining a high degree of chemical validity. This method represents a promising compromise between fragment-based and atom-based generation approaches [38].

Scaffold-based splits represent a critical evolution beyond random splits, providing a more rigorous and realistic benchmark for the generalizability of AI models in drug discovery. The evidence shows that they effectively prevent the over-optimistic performance estimates that result from having structurally similar molecules in both training and test sets. However, the field is rapidly advancing, with studies demonstrating that even scaffold splits may be insufficiently challenging. Newer methods, such as UMAP-based clustering splits, are setting a higher bar for what constitutes a realistic evaluation [23].

The future of reliable AI in drug discovery lies in the adoption of these more rigorous evaluation standards. Furthermore, the integration of scaffold-awareness directly into model training—through advanced data augmentation [37] and generation techniques [38]—presents a promising path forward. Ultimately, the combination of tough, realistic data splitting and innovative, scaffold-conscious modeling approaches will be key to building predictive tools that successfully translate from retrospective benchmarks to the discovery of novel, clinically relevant therapeutics.

Cross-Cohort and Leave-One-Dataset-Out (LODO) Validation for Multi-Source Data

In the field of phenotypic screening for drug development, the transition from initial hit identification to clinically viable candidates represents a formidable challenge. Traditional validation approaches, particularly single-cohort cross-validation, often produce overoptimistic performance estimates that fail to translate when models encounter data from new populations or experimental conditions [39]. This validation gap becomes critically important in pharmaceutical research and development, where the generalizability of a phenotypic model directly impacts downstream investment decisions and clinical success rates [40]. The increasing availability of multi-source datasets now enables more robust validation paradigms that better simulate real-world performance. Among these, cross-cohort and Leave-One-Dataset-Out (LODO) validation have emerged as essential methodologies for assessing model generalizability across diverse biological contexts and experimental conditions [41]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these advanced validation techniques, offering experimental protocols and implementation frameworks to enhance the rigor of phenotypic screening research.

Comparative Framework: Cross-Cohort vs. LODO Validation

Core Conceptual Definitions

Cross-cohort validation involves training a model on data from one source population and evaluating its performance on a distinct population, such as different geographic locations, institutions, or experimental batches [42] [41]. This approach tests whether a model can transcend the specific characteristics of its training data.

Leave-One-Dataset-Out (LODO) validation represents a more exhaustive approach where a model is trained on all available datasets except one, which is held out for testing. This process rotates through all datasets, with each serving as the test set exactly once [41]. LODO provides the most comprehensive assessment of model generalizability across multiple sources.

Key Methodological Differences and Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Cohort and LODO Validation Approaches

| Characteristic | Cross-Cohort Validation | LODO Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | Train on one complete cohort, test on another | Iteratively leave out entire datasets for testing |

| Minimum Datasets Required | 2 | 3 or more |

| Performance Estimate Stability | Moderate (depends on specific cohort pair) | High (averaged across multiple left-out datasets) |

| Computational Intensity | Lower | Higher (grows with number of datasets) |

| Primary Use Case | Assessing portability between specific populations | Evaluating generalizability across diverse sources |

| Risk of Data Leakage | Lower (clear separation between cohorts) | Moderate (requires careful implementation) |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Metrics

Empirical Findings from Clinical ECG Classification

A systematic evaluation of cross-validation methods in clinical electrocardiogram classification demonstrated that standard k-fold cross-validation significantly overestimates model performance when the goal is generalization to new data sources. In this study, k-fold cross-validation produced overoptimistic performance claims, while leave-source-out cross-validation (conceptually similar to LODO) provided more reliable generalization estimates with close to zero bias, though with greater variability [39]. This highlights the critical limitation of conventional validation approaches and underscores the necessity of source-level validation methods.

Phenotype Classifier Portability Across Medical Centers

Research on electronic phenotyping classifiers developed using the OHDSI common data model revealed important insights about cross-cohort performance. When classifiers were shared across medical centers, performance metrics showed measurable degradation: mean recall decreased by 0.08 and precision by 0.01 at a site within the USA, while an international site experienced more substantial decreases of 0.18 in recall and 0.10 in precision [42]. This demonstrates that classifier generalizability may have geographic limitations and that performance portability should not be assumed.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Bias in Performance Estimation | Variance of Estimate | Representativeness of Real-World Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard k-Fold CV | High (overoptimistic) | Low | Poor |

| Cross-Cohort Validation | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| LODO Validation | Low (near zero bias) | Higher | Excellent |

| Holdout Validation | Variable (depends on representativeness) | High | Poor to Moderate |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Cross-Cohort Validation

Step 1: Cohort Selection and Characterization

- Select at least two distinct cohorts with potential differences in demographic, technical, or experimental parameters

- Document all relevant cohort characteristics including source institution, data collection protocols, and population demographics

- Ensure cohorts have sufficient sample size for meaningful statistical power

Step 2: Model Training and Evaluation

- Train the phenotypic classifier exclusively on data from the source cohort

- Apply the trained model to the entirely separate target cohort without any retraining

- Calculate performance metrics (precision, recall, accuracy, AUC-ROC) on the target cohort

- Compare performance between source and target cohorts to assess portability

In the OHDSI phenotype study, this approach revealed that "classifier generalizability may have geographic limitations, and, consequently, sharing the classifier-building recipe, rather than the pretrained classifiers, may be more useful for facilitating collaborative observational research" [42].

Protocol for LODO Validation

Step 1: Dataset Collection and Harmonization

- Assemble multiple datasets (minimum of 3, preferably more) from distinct sources

- Perform necessary data harmonization while preserving source-specific characteristics

- Ensure consistent outcome definitions and feature representations across datasets

Step 2: Iterative Training and Testing

- For each dataset Di in the collection of datasets {D1, D2, ..., Dk}:

- Designate Di as the test set

- Combine all remaining datasets {D1, D2, ..., D{i-1}, D{i+1}, ..., Dk} as the training set

- Train model on the combined training set

- Evaluate model performance on the held-out test set D_i

- Calculate average performance metrics across all iterations

This approach is particularly valuable when "merging multiple data sets leads to improved performance and generalizability by allowing an algorithm to learn more general patterns" [41].

Workflow Visualization