Cross-Species Validation of Candidate Genes for Chicken Economic Traits: From Genomic Discovery to Biomedical Application

This article synthesizes the latest genomic strategies for identifying and validating candidate genes governing economically vital traits in chickens, with direct implications for poultry science and biomedical research.

Cross-Species Validation of Candidate Genes for Chicken Economic Traits: From Genomic Discovery to Biomedical Application

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest genomic strategies for identifying and validating candidate genes governing economically vital traits in chickens, with direct implications for poultry science and biomedical research. We explore the foundational principles of comparative genomics and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that underpin gene discovery for traits like growth, reproduction, and disease resistance. The content details advanced methodological frameworks, including multi-omics integration and CRISPR/Cas9 editing, for functional characterization. Furthermore, it addresses critical challenges in validation, such as resolving linkage disequilibrium and accounting for non-coding regulatory variation, and establishes a rigorous paradigm for cross-species validation of genetic mechanisms. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for translating avian genomic insights into advancements in agriculture and human medicine.

The Genomic Landscape of Chicken Economic Traits: Key Genes and Discovery Frameworks

The genetic improvement of poultry represents a cornerstone of global food security, with chicken serving as both a primary source of animal protein and a critical model organism in evolutionary biology. Understanding the genetic architecture underlying key economic traits—growth, meat quality, reproduction, and disease resistance—enables more precise breeding strategies and enhanced production efficiency. Recent advances in genomic technologies have facilitated the identification of candidate genes and molecular pathways controlling these complex polygenic traits. This review synthesizes current research on validating candidate genes for chicken economic traits across species, providing a comparative analysis of experimental approaches, key findings, and methodological frameworks that bridge poultry science with broader evolutionary biology.

Decoding the Genetic Architecture of Key Economic Traits

Growth Traits: From Quantitative Genetics to Candidate Genes

Growth performance remains a paramount selection target in broiler breeding programs worldwide, with body weight and feed efficiency serving as primary breeding objectives. Quantitative genetic analyses consistently demonstrate high heritability estimates for growth traits, with body weight at different ages showing h² values ranging from 0.28 to 0.45 [1]. Advanced genomic approaches have enabled researchers to move beyond traditional selection methods to identify specific genetic variants underlying these traits.

Table 1: Key Candidate Genes Associated with Growth Traits in Chickens

| Gene Symbol | Chromosomal Location | Associated Trait | Proposed Function | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCAPG | Not specified | Muscle development | Cell division and growth | [2] |

| LDB2 | Multiple chromosomes | General growth | Transcription factor | [2] [1] |

| IGF2BP1 | Not specified | Body weight | RNA binding and regulation | [1] |

| TGFBR2 | Not specified | General growth | Transforming growth factor beta signaling | [1] |

| MYF5 | Not specified | Muscle development | Myogenic factor | [2] |

| MYF6 | Not specified | Muscle development | Myogenic factor | [2] |

| GLI3 | Not specified | General growth | Hedgehog signaling pathway | [1] |

| GATA4 | Not specified | General growth | Transcription factor | [1] |

| AKT1 | Not specified | Muscle development | Insulin signaling pathway | [2] |

| LCORL | Not specified | General growth | Transcription factor | [3] |

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have emerged as a powerful tool for identifying quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) associated with growth variations. One comprehensive analysis identified 113 QTNs significantly associated with eight growth traits distributed across multiple chromosomes, with particularly notable concentrations on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, and 4 [1]. The LDB2 gene, repeatedly identified in multiple studies, encodes a transcription factor that regulates various developmental processes [2] [1]. Similarly, TGFBR2 functions within the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway, which plays crucial roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [1].

The development of multi-locus GWAS methods, including mrMLM, FASTmrMLM, and FASTmrEMMA, has enhanced statistical power for detecting small-effect QTNs that collectively explain significant portions of phenotypic variance [1]. These approaches have successfully identified genes such as IGF2BP1 (insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1) and GATA4 (GATA binding protein 4), which are involved in fundamental growth regulation pathways [1].

Meat Quality Attributes: Molecular Determinants and Genetic Markers

Meat quality encompasses multiple sensory, nutritional, and technological attributes, including tenderness, color, flavor, and composition. Consumer preferences for specific meat characteristics have driven research into the genetic basis of these traits, particularly in indigenous chicken breeds known for superior meat quality.

Table 2: Candidate Genes Associated with Meat Quality Traits in Chickens

| Gene Symbol | Associated Trait | Proposed Function | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2RX5 | Meat quality (a* value, cooking loss) | Purinergic receptor | [4] |

| A-FABP | Meat quality | Fatty acid binding protein | [3] |

| H-FABP | Meat quality | Fatty acid binding protein | [3] |

| PRKAB2 | Meat quality | AMP-activated protein kinase subunit | [3] |

| ELOVL6 | Fat deposition | Fatty acid elongation | [2] |

| KLF6 | Fat deposition | Transcription factor | [2] |

Recent integrative approaches combining metabolomics, lipidomics, and transcriptomics have identified the purinergic receptor P2RX5 as a key regulator of meat quality traits [4]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the P2RX5 gene show significant associations with critical meat quality parameters including a* value (redness) and cooking loss [4]. Additionally, genes involved in lipid metabolism such as A-FABP (adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein) and H-FABP (heart fatty acid-binding protein) influence intramuscular fat deposition and fatty acid composition, directly affecting meat flavor and juiciness [3].

Fat deposition traits, which directly impact meat quality, are modulated by genes including ELOVL6 (fatty acid elongase) and KLF6 (Kruppel-like factor 6), both identified through runs of homozygosity (ROH) analysis in specialized breeds [2]. The PRKAB2 gene, encoding a subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase, serves as a central regulator of cellular energy metabolism and has been implicated in meat quality variations [3].

Reproductive Efficiency: Genetic Controls of Egg Production

Reproductive performance in layer chickens encompasses multiple traits, including age at first egg (AFE), egg number (EN), and clutch characteristics. Understanding the genetic architecture of these traits is essential for improving egg production efficiency, particularly in indigenous breeds where genetic diversity remains high but productivity is often lower than in commercial lines.

Table 3: Candidate Genes Associated with Reproductive Traits in Chickens

| Gene Symbol | Associated Trait | Proposed Function | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCUBE1 | Age at first egg | Follicular development | [5] |

| KRAS | Age at first egg | Metabolic pathways | [5] |

| IGF1 | Clutch size, egg number | mTOR and insulin signaling | [5] |

| PTK2 | Clutch size, egg number | mTOR and insulin signaling | [5] |

| SOX5 | Egg production | Transcriptional regulation | [5] |

| PPFIBP1 | Egg production | Cell adhesion | [5] |

GWAS analyses in Wuhua yellow chickens, an indigenous breed, have identified 871 significant SNPs associated with egg production traits, annotating 379 candidate genes [5]. The SCUBE1 (signal peptide, CUB domain, and EGF-like domain containing 1) and KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) genes have emerged as important regulators of AFE, primarily through their roles in follicular development and metabolic pathways [5]. Similarly, IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) and PTK2 (protein tyrosine kinase 2) associate with clutch size and total egg number via the mTOR and insulin signaling pathways, which coordinate nutrient sensing with reproductive investment [5].

Notably, 13 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with reproductive traits overlap with known reproductive loci, including SOX5 (SRY-box transcription factor 5) and PPFIBP1 (PPFIA binding protein 1), highlighting conserved genetic mechanisms across chicken populations [5]. Functional enrichment analyses further reveal that these candidate genes participate in critical biological processes including cell adhesion, hormone signaling, and oocyte maturation pathways [5].

Disease Resistance: Immunogenetic Foundations of Host Defense

Disease resistance represents a crucial economic trait in poultry production, with genetic factors significantly influencing susceptibility to various pathogens. Immunogenetic research has identified numerous candidate genes associated with enhanced disease resistance, offering potential for marker-assisted selection to improve flock health and reduce antibiotic dependence.

Comparative genomic analyses have identified several genes associated with disease resistance traits, including C1QBP (complement C1q binding protein), VAV2 (vav guanine nucleotide exchange factor 2), and IL12B (interleukin 12B) [3]. These genes function within innate and adaptive immune pathways, modulating pathogen recognition, immune cell activation, and inflammatory responses. Functional annotation of disease resistance candidates reveals enrichment for pathways including the B-cell receptor and T-cell receptor signaling pathways, highlighting the importance of both humoral and cellular immunity in avian host defense [6].

Methodological Framework: Experimental Approaches for Trait Validation

Genomic Technologies and Breeding Applications

Modern poultry genetics employs diverse methodological approaches to identify and validate candidate genes for economic traits. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, with multi-faceted approaches providing the most comprehensive insights.

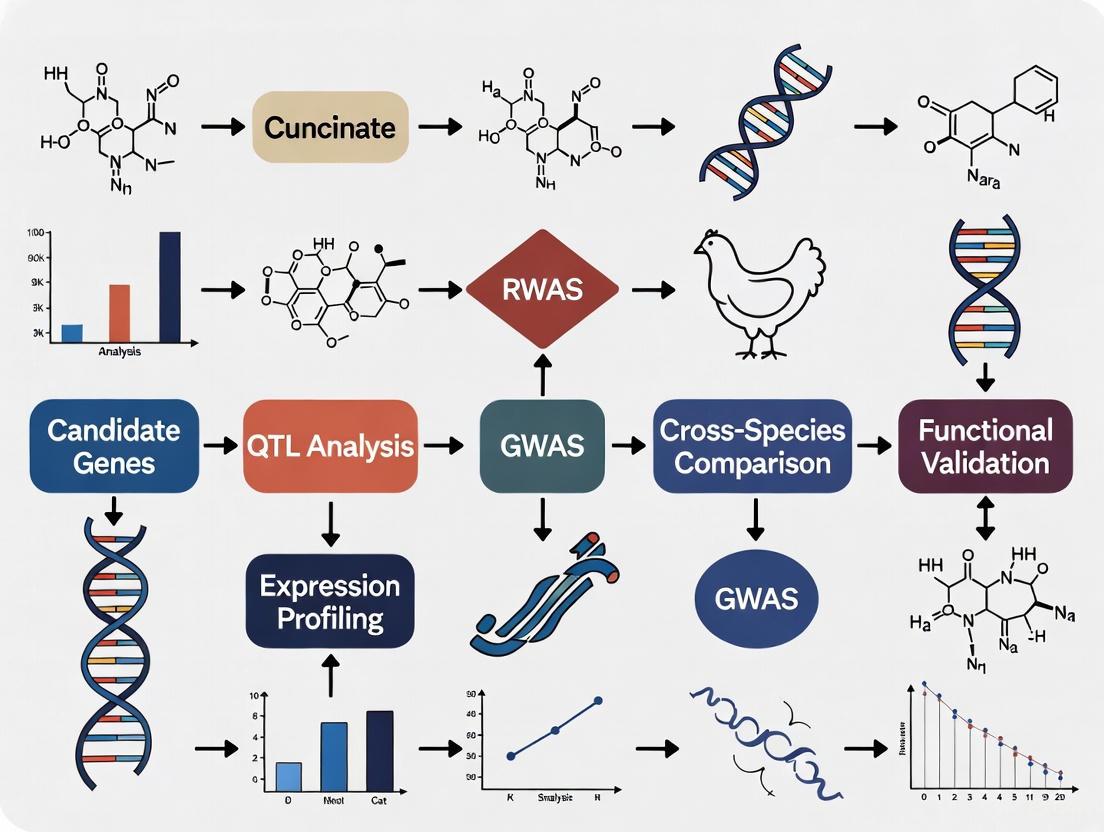

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying and validating candidate genes for economic traits in chickens, integrating multiple genomic approaches.

Genome-Wide Association Studies: Protocols and Applications

GWAS represents a foundational approach for identifying genetic variants associated with complex traits. The standard protocol involves:

Population Selection: Studies typically employ distinct populations, such as the Chengkou mountain chicken A-lineage (n=464) [2] [6] or F2 crosses between different breeds (n=319) [7], to ensure sufficient genetic diversity for association detection.

Genotyping and Quality Control: High-density SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing generate genotype data. For example, studies utilizing the 600K Affymetrix Axiom HD genotyping array or Illumina 60K SNP Beadchip implement rigorous quality control filters, including individual missing rate <0.01, site missing rate <0.01, and minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.01 [8].

Association Analysis: Mixed linear models (MLM) account for population structure and genetic relationships, with principal components included as covariates. Multi-locus methods like mrMLM, FASTmrMLM, and FASTmrEMMA employ a logarithm of odds (LOD) threshold ≥3 for significance detection without overly stringent multiple testing corrections [1].

Candidate Gene Annotation: Significantly associated SNPs are mapped to the reference genome, with genes within proximity (typically ±500 kb) considered candidates. Functional annotation follows using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases [6].

Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) Analysis

ROH analysis identifies long, continuous homozygous segments in the genome, reflecting inbreeding and selective signatures. The standard methodology includes:

ROH Detection: Software like PLINK identifies ROH segments using sliding window approaches with parameters accounting for SNP density, heterozygous calls, and segment length [2].

ROH Island Identification: Genomic regions with high ROH frequency across individuals (top 0.5%) indicate selection signatures. For example, analysis of 464 CMC-A chickens identified 414 ROH islands containing 317 candidate genes [6].

Functional Annotation: Genes within ROH islands undergo functional enrichment analysis to identify biological processes under selection. Studies consistently find ROH islands enriched for genes involved in stress resistance, muscle development, and metabolic processes [2].

Cross-Species Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomic approaches leverage evolutionary conservation to identify functionally important genes. The standard analytical pipeline includes:

Ortholog Identification: Software such as OrthoFinder clusters protein sequences from multiple species (e.g., chicken, duck, goose, cow, sheep, pig, human, zebrafish) into orthologous groups using sequence similarity searches with E-value thresholds of 0.001 [3].

Phylogenetic Analysis and Divergence Time Estimation: Single-copy orthologs undergo multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT, with phylogenetic trees constructed using maximum likelihood methods in IQ-TREE [3].

Selection Analysis: The CodeML module of PAML implements branch-site models to detect positive selection, with likelihood ratio tests identifying genes showing evidence of adaptive evolution [3].

Synteny Analysis: Genomic collinearity between species identifies conserved regulatory blocks, with algorithms like interspecies point projection (IPP) identifying orthologous regulatory elements despite sequence divergence [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Poultry Genomics Research

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Example | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | 600K Affymetrix Axiom HD, Illumina 60K SNP Beadchip | Genome-wide variant detection | [8] |

| Reference Genomes | GRCg6a, GRCg7b (Gallus gallus) | Read alignment and annotation | [8] [6] |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | MAFFT (v7.205) | Multiple sequence alignment | [3] |

| Orthology Detection | OrthoFinder (v2.4.0) | Gene family clustering | [3] |

| GWAS Software | PLINK (v1.9), GCTA (v1.94), mrMLM (v4.0.2) | Association analysis | [2] [8] [1] |

| Selection Analysis | PAML (v4.9i) CodeML module | Positive selection detection | [3] |

| Functional Annotation | GO, KEGG databases | Pathway enrichment analysis | [3] [6] |

Conserved Biological Pathways Across Economic Traits

Integration of candidate gene analyses reveals several conserved biological pathways that recurrently associate with multiple economic traits in chickens:

Figure 2: Key biological pathways and their associations with multiple economic traits in chickens. Solid lines indicate primary associations; dashed lines represent secondary connections.

The insulin/IGF signaling pathway emerges as a central regulator connecting growth, reproduction, and metabolism. Genes including IGF1 and IGF2BP1 influence growth traits through the regulation of cellular proliferation and protein synthesis [1] [5], while simultaneously affecting reproductive efficiency through nutrient-sensing mechanisms that coordinate energy allocation [5]. Similarly, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling components such as TGFBR2 participate in skeletal muscle development [1], while also modulating immune responses that contribute to disease resistance [3].

The mTOR pathway serves as another integrative node, connecting nutrient availability with reproductive investment through genes including IGF1 and PTK2 [5]. Lipid metabolism pathways, involving genes such as A-FABP, H-FABP, and ELOVL6, directly impact meat quality through intramuscular fat deposition [2] [3], while also influencing energy availability for growth processes [2].

The validation of candidate genes for core economic traits in chickens has progressed substantially through integrated genomic approaches. GWAS, ROH analyses, and comparative genomics have identified numerous candidate genes with verified effects on growth, meat quality, reproduction, and disease resistance. The emergence of conserved biological pathways across these traits highlights the interconnected nature of avian physiology and the potential for multi-trait selection approaches.

Future research directions should prioritize functional validation of candidate genes through gene editing and functional genomics, integration of multi-omics data to refine transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, and development of improved genomic prediction models that incorporate functional annotations. Furthermore, expanding comparative genomic analyses across broader evolutionary distances will enhance our understanding of conserved genetic mechanisms underlying economically important traits.

The continued identification and validation of candidate genes will enable more precise genomic selection in poultry breeding, enhancing production efficiency while maintaining genetic diversity. This progress supports the development of sustainable poultry production systems capable of meeting global food demands in changing environmental conditions.

The genetic improvement of chickens, a critical source of global animal protein, increasingly relies on identifying and validating genes that control economically important traits. This guide provides a comparative analysis of validated candidate genes for key traits—growth, meat quality, feed efficiency, reproductive performance, and melanin deposition—synthesized from recent genomics studies. We objectively compare the supporting experimental data and methodologies, framing this within the broader thesis that cross-species comparative genomics and multi-omics integration are revolutionizing the validation of causal genes in avian species.

Comparative Tables of Validated Candidate Genes

Table 1: Candidate Genes for Primary Economic Traits in Chickens

| Trait Category | Candidate Gene | Key Supporting Evidence | Associated Phenotype / Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Traits | TBX22 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Skeletal and body growth development |

LCORL |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Stature and body size regulation | |

GH |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Overall growth rate and metabolism | |

| Meat Quality Traits | A-FABP |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Fat deposition and intramuscular fat content |

H-FABP |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Fatty acid composition and marbling | |

PRKAB2 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Energy sensing, impacting meat quality | |

| Feed Efficiency | PLCE1 |

GWAS in Wenchang Chickens [11] | Residual Feed Intake (RFI) |

LAP3 |

GWAS in Wenchang Chickens [11] | Body weight and feed efficiency | |

MED28 |

GWAS in Wenchang Chickens [11] | Body weight and feed efficiency | |

| Reproductive Traits | IGF-1 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Egg production and maturation |

SLC25A29 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Reproductive efficiency | |

WDR25 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Egg-laying performance | |

| Disease Resistance | C1QBP |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Immune response and pathogen defense |

VAV2 |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Immune cell signaling | |

IL12B |

Comparative Genomic Analysis [3] [10] | Inflammation and immune regulation |

Table 2: Key Candidate Genes for Melanin Deposition in Chicken Muscle and Skin

| Candidate Gene | Key Supporting Evidence | Proposed Molecular Function |

|---|---|---|

TYR |

Transcriptome profiling in Tengchong Snow chicken [12]; Whole-transcriptome sequencing in Xichuan black-bone chicken [13]; Dynamic transcriptome analysis in Yugan chicken [14] | Key enzyme in melanin synthesis pathway; rate-limiting step of tyrosine conversion. |

TYRP1 |

Transcriptome & metabolome analysis in Yanjin & Jinling chickens [15]; Dynamic transcriptome analysis in Yugan chicken [14] | Stabilizes TYR enzyme; modulates eumelanin synthesis. |

DCT |

Transcriptome profiling in Tengchong Snow chicken [12]; Whole-transcriptome sequencing in Xichuan black-bone chicken [13]; Dynamic transcriptome analysis in Yugan chicken [14] | Melanogenic enzyme involved in eumelanin synthesis. |

EDNRB2 |

Transcriptome profiling in Tengchong Snow chicken [12]; Transcriptome & metabolome analysis in Yanjin & Jinling chickens [15]; Dynamic transcriptome analysis (signaling pathway) [14] | Receptor in endothelin signaling; promotes melanocyte proliferation/differentiation. |

KIT |

Transcriptome & metabolome analysis in Yanjin & Jinling chickens [15] | Receptor for stem cell factor; critical for melanocyte survival and migration. |

MITF |

Transcriptome profiling in Tengchong Snow chicken [12] | Master regulator of melanocyte development and melanogenic gene transcription. |

GPNMB |

Dynamic transcriptome analysis in Yugan chicken [14] | Involved in melanosome maturation and pigment cell differentiation. |

Experimental Data and Validation Protocols

Genomic Selection and Cross-Species Comparison

Protocol Overview: This approach identifies genes under selection or conserved across species that are associated with traits of interest.

- Gene Family Clustering: Protein sequences from multiple species (e.g., chicken, duck, cow, human, zebrafish) are clustered into orthologous groups using tools like OrthoFinder [3].

- Phylogenetic and Divergence Time Analysis: Single-copy orthologs are used to construct a phylogenetic tree and estimate species divergence times [3].

- Analysis of Gene Family Expansion/Contraction: Software like CAFE identifies gene families that have significantly expanded or contracted in specific lineages, potentially related to trait evolution [3].

- Positive Selection Analysis: The branch-site model in PAML's CodeML is used to detect genes with a high ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (ω > 1), indicating positive selection [3].

- Functional Annotation: Candidate genes are annotated using GO and KEGG databases to identify enriched biological processes and pathways [3] [10].

Transcriptome Profiling for Melanin Deposition

Protocol Overview: RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) compares gene expression in tissues with high vs. low melanin content to identify key regulators.

- Sample Collection: Skin or breast muscle samples are collected from chickens with divergent pigmentation phenotypes (e.g., black meat vs. white meat) [12] [15].

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Total RNA is extracted, library preparation is performed, and sequencing is conducted on platforms like Illumina HiSeq [12] [14].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Reads are mapped to a reference genome, and statistical tools are used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with high stringency (e.g., fold change ≥ 2.0, FDR < 0.05) [12] [14].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: DEGs are analyzed for enrichment in specific biological pathways, such as melanogenesis and tyrosine metabolism, using KEGG [12] [15].

- qPCR Validation: The expression patterns of key candidate genes are validated using quantitative real-time PCR [12].

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) for Complex Traits

Protocol Overview: GWAS correlates genome-wide genetic markers with phenotypic variation to pinpoint genomic regions and candidate genes.

- Population Design: Large populations (e.g., >1,000 birds) with recorded precise phenotypes are established [16] [11].

- Genotyping: High-density SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing are used for genotyping [16] [11].

- Quality Control (QC): Genotype data is filtered based on individual/genotype call rate, minor allele frequency (MAF), and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [11].

- Association Analysis: Mixed-model GWAS is performed to identify significant marker-trait associations, accounting for population structure [16] [11].

- Fine Mapping: Advanced populations like Advanced Intercross Lines (AILs) are used to increase recombination and narrow down quantitative trait loci (QTLs) to single-gene resolution [16].

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

Protocol Overview: Combining transcriptomics and metabolomics provides a systems-level view of the molecular networks underlying a trait.

- Concurrent Profiling: The same tissue samples are subjected to both RNA-seq and LC-MS/MS-based metabolomic profiling [15].

- Integrated Data Mining: Differential expression (genes) and abundance (metabolites) are analyzed to identify common enriched pathways [15].

- Network Construction: A joint network is built to connect significant metabolites with key genes, offering a more comprehensive regulatory picture [15].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks

Core Melanogenesis Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the central pathway of melanin synthesis and its key regulatory inputs, integrating information from multiple studies on black-bone chickens [15] [13] [14].

Advanced Intercross Line (AIL) Workflow for Gene Fine-Mapping

The diagram below outlines the strategic breeding and analysis pipeline used to achieve high-resolution mapping of QTLs, as demonstrated in a 16-generation chicken study [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Category | Item / Reagent | Specific Example / Model | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing & Genotyping | High-Throughput Sequencer | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 [11] | Whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. |

| Custom SNP Array | Chicken 55K SNP array [11] | Cost-effective genome-wide genotyping for GWAS. | |

| Low-Coverage Sequencing | Protocol from AIL study [16] | Genotyping large populations cost-effectively. | |

| Phenotypic Measurement | Colorimeter | Minolta CR-400 [15]; NR20XE [14] | Objectively measures skin/muscle lightness (L* value). |

| Melanin ELISA Kits | Commercial ELISA Kits [12] | Quantifies eumelanin and pheomelanin content in tissues. | |

| Electronic Scale | Precision 0.1 g [11] | Accurate body weight measurement for growth traits. | |

| Bioinformatics Software | Ortholog Finder | OrthoFinder (v2.4.0) [3] | Clusters protein sequences into orthologous groups. |

| Phylogenetic Tool | IQ-TREE (v2.2.0) [3] | Constructs maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees. | |

| Gene Family Analysis | CAFE (v4.2) [3] | Models gene family expansion/contraction. | |

| Selection Analysis | PAML/CodeML (v4.9i) [3] | Detects genes under positive selection. | |

| GWAS & QC Software | PLINK (v2.0) [11] | Standard tool for genome-wide association analysis. | |

| Laboratory Consumables | RNA Extraction Kit | TRIzol Reagent [14]; Commercial Kits [12] | High-quality total RNA isolation for transcriptomics. |

| qPCR Reagents | SYBR Green kits [12] | Validates gene expression patterns from RNA-seq data. | |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Column | Anion exchange columns [15] | Purifies melanin metabolites for LC-MS/MS analysis. |

Comparative genomics has emerged as a powerful methodology for identifying functionally important regions in genomes by analyzing evolutionary conservation across species. The fundamental premise is that sequences performing critical biological functions—including both protein-coding genes and regulatory elements—demonstrate significant conservation between evolutionarily distant species, distinguishing them from non-functional surrounding sequences [17]. This approach has been successfully applied across the tree of life, from mammals to birds, providing insights into shared and specialized biological traits.

In agricultural genomics, comparative approaches are revolutionizing our understanding of economically important traits in domesticated species. For chickens (Gallus gallus), a vital global food source providing meat and eggs, comparative genomics offers powerful tools for identifying candidate genes associated with key production traits such as growth rate, meat quality, egg production, and disease resistance [18] [3]. By examining genomic similarities and differences across multiple species, researchers can identify conserved genes, expanded gene families, and genes that have undergone positive selection—all of which may be linked to biological characteristics and key traits [18].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of methodologies, tools, and applications in comparative genomics, with a specific focus on validating candidate genes for chicken economic traits through multi-species genomic alignment approaches.

Comparative Genomics Methodologies: A Technical Comparison

Comparative genomics employs diverse computational methods to investigate genomic similarities and differences among species. These approaches span multiple analytical domains, each contributing unique insights into genome evolution and function.

Core Analytical Frameworks in Comparative Genomics

Table 1: Comparative Genomics Methods and Their Applications

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Primary Applications | Key Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Alignment | Global alignment, Local alignment | Identifying conserved coding and noncoding sequences | VISTA, PipMaker, AVID, BLASTZ [17] |

| Gene Family Analysis | Gene family clustering, Expansion/contraction analysis | Orthologous gene identification, Evolutionary trajectory | OrthoFinder, CAFE [18] [3] |

| Evolutionary Analysis | Phylogenetic reconstruction, Divergence time estimation, Positive selection detection | Evolutionary relationships, Selective pressures | IQ-TREE, PAML/CodeML [18] [3] |

| Genome Structure Analysis | Synteny analysis, Whole-genome duplication detection | Genomic rearrangements, Structural variations | JCVI, WGD [18] [3] |

Practical Implementation Considerations

The evolutionary distance between compared species significantly impacts the analytical outcomes. As demonstrated in studies of the ApoE genomic region, human-chimpanzee comparisons revealed limited informative conservation due to recent divergence, while human-mouse comparisons successfully identified functional coding and noncoding sequences [17]. This highlights the importance of selecting appropriate species for comparison based on the specific biological questions being investigated.

Different visualization tools offer complementary advantages. PipMaker displays linear blocks of ungapped alignments, which helps distinguish coding sequences (less tolerant to insertions/deletions) from functional noncoding DNA. In contrast, VISTA generates peak-like features that readily identify candidate gene-regulatory elements and conserved coding domains [17].

Experimental Protocols for Candidate Gene Validation in Chickens

Multi-Species Genomic Alignment Workflow

Diagram 1: Comparative genomics workflow for candidate gene identification.

Genome Data Acquisition and Processing

The foundational step involves collecting high-quality genome assemblies from multiple species. A typical analysis might include chickens (Gallus gallus), ducks (Anas platyrhynchos), geese (Anser cygnoides), and evolutionarily distant reference species such as cows (Bos taurus), pigs (Sus scrofa), humans (Homo sapiens), and zebrafish (Danio rerio) [18] [3]. These data are sourced from public databases including NCBI Genome Database and Ensembl. For each species, researchers download the reference genome assembly, protein sequences, and annotation files in GFF format, prioritizing the most recent reference genome versions available.

Orthologous Gene Identification

Protein sequences corresponding to the longest transcripts of protein-coding genes are extracted for gene family clustering. Orthologous gene families are identified using OrthoFinder (v2.4.0) with sequence similarity searches performed using DIAMOND and an E-value threshold of 0.001 [18] [3]. This process groups genes into families based on evolutionary relationships, distinguishing between orthologs (genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene) and paralogs (genes related by duplication within a genome).

Phylogenetic Analysis and Divergence Time Estimation

The protein sequences of single-copy orthologous genes identified using OrthoFinder are used for phylogenetic tree construction. Multiple sequence alignments are performed using MAFFT (v7.205) with parameters --localpair and --maxiterate 1000 [18] [3]. Poorly aligned or highly divergent regions are removed using Gblocks (v0.91b) with parameter -b5 = h. The filtered alignments are concatenated into a supergene sequence for each species, and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree is constructed using IQ-TREE (v2.2.0) with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess node support.

Gene Family Evolution and Positive Selection Analysis

Based on identified gene families and the species phylogenetic tree, gene family expansion and contraction analyses are performed using CAFE software (v4.2) [18] [3]. Families with conditional p-values less than 0.05 are considered to have undergone significant expansion or contraction. For positive selection analysis, single-copy orthologous gene families are analyzed using the CodeML module of PAML (v4.9i). The branch-site model compares Model A (allowing positive selection on specific sites in the foreground branch, ω > 1) against a null model (no sites with ω > 1). A likelihood ratio test determines statistical significance (p < 0.05), with sites showing posterior probability > 0.95 considered under significant positive selection.

Advanced Intercross Line Design for High-Resolution Mapping

Diagram 2: Advanced intercross line design for trait mapping.

Advanced intercross lines (AILs) represent a powerful approach for enhancing mapping resolution of complex traits. In chicken research, a 16-generation AIL was developed through reciprocal crosses between Huiyang Bearded chicken and High-Quality Chicken Line A, which exhibit significant phenotypic differences in growth traits [16]. Subsequent generations (F3 to F16) were derived through random mating with maintained population diversity. This design rapidly accumulates recombination events, breaking down linkage disequilibrium and enabling quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping at the single-gene level.

The AIL approach demonstrates remarkable effectiveness, with linkage disequilibrium decaying rapidly across generations (r²₀.₁ = 143 kb in F16 compared to 259 kb in F2) [16]. This enhanced resolution allows QTL intervals to be refined to an average length of 244 ± 343 kb, with 84.2% of QTLs shorter than 500 kb—significantly improving the ability to identify candidate genes.

Validated Candidate Genes for Chicken Economic Traits

Comparative genomic analyses across multiple species have identified numerous candidate genes associated with economically important traits in chickens. These findings are further validated through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and advanced intercross line approaches.

Comprehensive Candidate Gene Catalog

Table 2: Validated Candidate Genes for Chicken Economic Traits

| Trait Category | Candidate Genes | Biological Function | Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Traits | TBX22, LCORL, GH | Transcription regulation, Growth hormone signaling | Comparative genomics, Positive selection [18] [3] |

| Meat Quality | A-FABP, H-FABP, PRKAB2 | Fatty acid binding, Energy metabolism | Gene family expansion, Functional annotation [18] [3] |

| Reproductive Performance | IGF-1, SLC25A29, WDR25, YY1 | Follicular development, Oocyte maturation | GWAS, Comparative genomics [18] [3] [19] |

| Egg Production | SCUBE1, KRAS, NELL2, KITLG | Hormone signaling, Follicle development | GWAS, Selective sweep analysis [5] [19] |

| Disease Resistance | C1QBP, VAV2, IL12B | Immune response, Inflammation regulation | Positive selection, Functional annotation [18] [3] |

| Egg Weight | ATF6, CSPG4, BSG, CFD | Cellular stress response, Hormone regulation | Multi-omics integration, ChickenGTEx [20] |

Key Signaling Pathways for Economic Traits

Functional enrichment analyses reveal that candidate genes for chicken economic traits are significantly involved in specific biological pathways. For growth traits, genes are predominantly enriched in transcription and signal transduction mechanisms [18] [3]. Meat quality genes participate in fatty acid metabolism and energy sensing pathways. Reproductive trait genes, particularly those associated with egg production, are frequently involved in hormonal signaling, follicular development, and oocyte maturation pathways [5] [19].

Notably, mTOR and insulin signaling pathways have been identified as crucial regulators of clutch size and egg number through genes such as IGF1 and PTK2 [5]. Similarly, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) signaling, mediated through genes like MAP2K2 and FSHB, influences egg weight by regulating gonadotropin expression [20].

The effectiveness of comparative genomics depends heavily on the selection of appropriate tools and resources. Current genomic analysis platforms offer complementary strengths for different research applications.

Genomic Visualization and Analysis Platforms

Table 3: Comparative Genomics Tools and Their Applications

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| VISTA Browser | Genome alignment visualization | Global alignment strategy, Peak-based conservation display | Identifying conserved coding and noncoding regions [17] [21] |

| PipMaker | Local alignment visualization | Block-based alignment display, Distinguishes coding/noncoding | Analyzing regions with insertions/deletions [17] |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Whole-genome annotation | Multiple track display, L-score conservation metric | Integrating multiple data types for genomic intervals [17] |

| MOSGA 2 | Genome quality control | Quality validation, Phylogenetic analysis | Quality assessment of genome assemblies [22] |

| Zoonomia Project | Mammalian genomic alignment | 240 species alignment, Evolutionary constraint analysis | Cross-species constraint identification [23] |

- NCBI Genome Database: Primary source for reference genome assemblies, protein sequences, and annotation files in GFF format [18] [3]

- Ensembl: Comprehensive genome annotation with comparative genomics capabilities and ortholog prediction [18] [3]

- Animal QTLdb: Repository of documented quantitative trait loci for agricultural species, enabling comparison with newly identified regions [19]

- VISTA Enhancer DB: Database of experimentally validated human noncoding fragments with gene enhancer activity, useful for regulatory element analysis [21]

Analytical Software and Pipelines

- OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics, using protein sequences to identify orthologous gene families [18] [3]

- CAFE: Computational analysis of gene family evolution, detecting expansions and contractions across phylogenetic trees [18] [3]

- PAML/CodeML: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood, particularly for detecting positive selection using codon substitution models [18] [3]

- IQ-TREE: Efficient software for maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree construction, with model selection and branch support assessment [18] [3]

Comparative genomics, particularly through multi-species genomic alignment, provides powerful approaches for identifying and validating candidate genes associated with economically important traits in chickens. The integration of evolutionary analyses—including gene family evolution, positive selection detection, and conserved noncoding element identification—with population genetics approaches such as advanced intercross lines and genome-wide association studies creates a robust framework for candidate gene prioritization.

These methods have successfully identified genes influencing growth (TBX22, LCORL), meat quality (A-FABP, H-FABP), reproduction (IGF-1, WDR25), and disease resistance (C1QBP, VAV2) in chickens [18] [3]. The continuing development of genomic resources, including expanded genome assemblies, functional annotations, and multi-omics datasets, will further enhance the resolution and accuracy of these approaches.

For researchers investigating complex traits in agricultural species, a combined strategy leveraging both cross-species comparative analyses and within-species high-resolution mapping offers the most promising path forward. This integrated approach facilitates the identification of causal genes and variants, ultimately accelerating genetic improvement programs for chicken and other agricultural species.

The advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has revolutionized genetic research by enabling the systematic identification of genetic variants underlying complex traits. In poultry genetics, these approaches have become indispensable for elucidating the genetic architecture of economically important traits such as body weight, feed efficiency, and egg production. However, single-population GWAS often suffer from limited sample sizes, resulting in reduced statistical power to detect variants with small to moderate effects. This limitation has spurred the adoption of meta-analysis techniques, which combine results from multiple studies to enhance detection power and improve the reliability of identified associations. The integration of these methods has accelerated genetic progress in chicken breeding by providing robust molecular markers for selection programs while offering insights into biological mechanisms governing polygenic traits.

GWAS and Meta-Analysis: Methodological Foundations and Comparative Power

Fundamental Principles of GWAS

Genome-wide association studies operate on the fundamental principle of testing associations between genetic markers (typically single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs) and phenotypes across the entire genome. In chicken populations, this approach has successfully identified numerous quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for production traits. The basic genetic model for GWAS can be represented as:

y = Xb + Za + e

Where y is the vector of phenotypic values, X is the design matrix for fixed effects (e.g., sex, batch), b is the vector of fixed effect coefficients, Z is the genotype matrix, a is the vector of SNP effects, and e is the vector of residual errors [8]. For accurate implementation, researchers must account for population stratification through principal component analysis (PCA) and consider relatedness among individuals using a genomic relationship matrix (G) [8] [11].

Meta-Analysis Approaches and Their Advantages

Meta-analysis quantitatively combines summary statistics from multiple independent GWAS, effectively increasing sample size and statistical power. The fixed-effect inverse variance weighting method is commonly implemented in tools like METAL [8]. This approach provides several key advantages over single-population studies, including enhanced power to detect novel variants, minimized false positives, and ability to investigate heterogeneity of effects across populations [24]. For example, a meta-analysis of three genetically distinct chicken populations identified 77 novel independent variants associated with body weight traits that were not detected in individual population analyses [8].

Empirical Comparisons of Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of GWAS Methodological Approaches for Complex Trait Analysis

| Method | Statistical Power | Population Structure Control | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Population GWAS | Limited by cohort size | Principal components analysis | Individual-level genotype and phenotype data | Simple implementation; optimal for homogeneous populations | Low power for small-effect variants; limited generalizability |

| GWAS Meta-Analysis | Enhanced through sample size expansion | Study-level correction combined across studies | Summary statistics from multiple studies | Increased discovery power; practical for consortia | Challenging for admixed individuals; potential heterogeneity |

| Mega-Analysis (Pooled) | Highest when allele frequencies vary across populations | Global principal components across all data | Individual-level data from all studies | Maximizes sample size; accommodates admixed individuals | Complex data harmonization; privacy and consent limitations |

| Gene-Based Meta-Analysis | Improved for rare variants and genes with multiple signals | Can incorporate ancestry-specific LD patterns | Summary statistics and linkage disequilibrium matrices | Aggregates signals across multiple variants in a gene; reduces multiple testing burden | Computationally intensive; requires accurate LD estimation |

Empirical comparisons demonstrate that pooled mega-analysis (jointly analyzing raw data from multiple studies) generally provides superior statistical power compared to meta-analysis, particularly when allele frequencies vary across ancestral groups [25]. However, meta-analysis remains a valuable approach when data sharing restrictions prevent individual-level data pooling, offering comparable results for main effect detection while effectively controlling for population structure [26]. For gene-environment interactions, both methods produce largely consistent results, making meta-analysis a practical choice for consortia with data sharing limitations [26].

Experimental Protocols in Avian Genomics

Standard GWAS Protocol in Chicken Populations

A comprehensive GWAS protocol for chicken economic traits involves multiple standardized steps. First, phenotypic measurements are collected for target traits (e.g., body weights at 56, 70, and 84 days; feed intake records; or egg production parameters) [8] [11]. For body weight traits, measurements are typically recorded electronically with precision to 0.1 g, with careful standardization of fasting periods before weighing [11]. Blood samples are then collected for DNA extraction, usually from wing veins using EDTA-K2 as an anticoagulant, followed by genomic DNA extraction via phenol-chloroform or commercial kit methods [11].

Genotyping is performed using medium- to high-density SNP arrays, such as the 600K Affymetrix Axiom HD array or Illumina 60K SNP BeadChip [8]. Quality control procedures eliminate markers with high missing rates (>1%), low minor allele frequency (MAF <1%), and deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.0001) [8] [11]. For whole-genome sequencing studies, similar QC thresholds are applied, requiring individual genotype detection rates ≥90% and MAF ≥5% [11]. Genotype imputation to a reference panel (e.g., ChickenGTEx) enhances genomic coverage, with accuracy filtering based on DR2 scores >0.4 [8].

Population stratification is addressed through principal component analysis, with the optimal number of PCs (determined by genomic inflation factors) included as covariates in association models [8] [19]. Association testing typically employs mixed linear models implemented in software such as GCTA-fastGWA or GEMMA, which account for relatedness and population structure [8] [19]. Significance thresholds are established based on the number of independent SNPs, with genome-wide significance typically set at p < 5×10^(-8) and suggestive significance at p < 1×10^(-5) [8] [19].

Meta-Analysis Implementation Framework

Implementing a robust meta-analysis requires coordinated efforts across participating studies. The process begins with developing a detailed protocol specifying dataset eligibility criteria, phenotype and genotype standardization methods, quality control procedures, and analytical plans [24]. Each participating study conducts GWAS using harmonized models, adjusting for study-specific covariates and population structure.

Summary statistics (effect sizes, standard errors, p-values, and allele frequencies) are shared for all variants passing quality control. For imputed variants, imputation accuracy scores should be included. The meta-analysis then combines these statistics using inverse variance-weighted fixed-effects models in software such as METAL [8]. Heterogeneity across studies should be quantified using I² statistics or Cochran's Q tests to identify potentially problematic associations with inconsistent effects [24].

Advanced Population Designs for Fine-Mapping

Advanced intercross lines (AILs) represent a powerful approach for enhancing mapping resolution in chicken genomics. These populations are created through multiple generations of random mating, which increases recombination events and breaks down linkage disequilibrium [16]. For example, a 16-generation chicken AIL demonstrated rapid LD decay (r²₀.₁ = 143 kb in F16 versus 259 kb in F2), enabling the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) at single-gene resolution [16]. The maintenance of such populations requires careful management of effective population size to minimize genetic drift and inbreeding, typically requiring hundreds of mating pairs per generation [16].

Key Findings and Genetic Architecture of Chicken Economic Traits

Body Weight and Growth Traits

GWAS and meta-analysis have substantially advanced our understanding of the genetic basis for body weight in chickens. A multi-population meta-analysis focusing on body weight at 56, 70, and 84 days identified 77 novel independent variants and 59 candidate genes, with specific SNPs (1170526144G>T and 1170642110A>G) showing enrichment in enhancer and promoter elements of KPNA3 and CAB39L in muscle, adipose, and intestinal tissues [8]. Genomic studies across 25 diverse chicken breeds have highlighted IGF1 and SMC1B as potent drivers of body size variation, with SOX5 emerging as another key regulator [27].

Table 2: Key Genetic Loci for Chicken Economic Traits Identified Through GWAS and Meta-Analysis

| Trait Category | Key Candidate Genes | Chromosomal Regions | Biological Functions | Study Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight & Growth | KPNA3, CAB39L, IGF1, SOX5, SMC1B | GGA1, GGA5, GGA27 | Muscle development, adipose regulation, insulin signaling | Multi-population meta-analysis [8]; Genomic diversity analysis [27] |

| Feed Efficiency | PLCE1, LAP3, MED28, QDPR, LDB2, SEL1L3 | Multiple regions | Feed intake regulation, metabolic efficiency | Single-breed GWAS [11] |

| Egg Production | SCUBE1, KRAS, IGF1, PTK2, NELL2, KITLG | GGA5 (48.61-48.84 Mb), GGA13 | Follicular development, hormone signaling, oocyte maturation | Mixed-breed GWAS [5] [19] |

| Sperm Storage Capacity | NEDD4, SMC1B | Not specified | Fertilization efficiency, reproductive performance | Genomic diversity analysis [27] |

Heritability estimates for growth traits vary considerably across populations and measurement timepoints. For Wenchang chickens, the heritability of body weight traits ranges from 0.30 to 0.44, while feed efficiency traits show lower heritability (e.g., residual feed intake at 0.05) [11]. In advanced intercross lines, growth and development traits demonstrate moderate heritability (0.31 ± 0.16), similar to tissue and carcass phenotypes (0.30 ± 0.13) [16].

Feed Efficiency and Metabolism

Feed efficiency represents a crucial economic trait in poultry production, with feed costs accounting for over 70% of total production expenses [11]. GWAS in Wenchang chickens have identified several candidate genes, including PLCE1, LAP3, MED28, QDPR, LDB2, and SEL1L3, which influence residual feed intake and average daily food intake [11]. The genetic architecture of feed efficiency appears highly polygenic, with genomic heritability estimates substantially lower than for growth traits (0.05 for RFI versus 0.21-0.44 for growth traits) [11].

Egg Production and Reproductive Traits

Egg production traits exhibit complex genetic architecture influenced by numerous small-effect variants. GWAS in Wuhua yellow chickens identified 871 significant SNPs (51 genome-wide, 820 suggestive) and 379 candidate genes for egg-laying performance [5]. Key regulators include SCUBE1 and KRAS for age at first egg through follicular development and metabolic pathways, while IGF1 and PTK2 associate with clutch size and egg number primarily through mTOR and insulin signaling pathways [5]. A separate study focusing on egg number differences between commercial and indigenous chickens identified the 48.61-48.84 Mb region on GGA5 as the most significant genomic region, containing candidate genes YY1 and WDR25 which function in oocyte growth and reproductive tissue development [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chicken Genomic Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application in Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | 600K Affymetrix Axiom HD Array; Illumina 60K SNP BeadChip; Custom 55K SNP arrays | Genome-wide variant screening; Genotype data generation | High-density coverage; Standardized platforms; Cost-effective |

| Reference Genomes | GRCg6a (Gallus gallus reference genome) | Variant mapping; Coordinate standardization | Improved annotation; LiftOver compatibility |

| Genotype Imputation | ChickenGTEx panel; Beagle 5.1/5.2 software | Enhancing genomic coverage from array data | Improved variant discovery; Cross-platform harmonization |

| GWAS Software | GCTA-fastGWA; REGENIE; GEMMA; PLINK | Association analysis; Population structure control | Efficient mixed models; Relatedness adjustment; Large dataset handling |

| Meta-Analysis Tools | METAL; REMETA; RAREMETAL | Combining summary statistics; Gene-based tests | Inverse variance weighting; Efficient LD handling; Multi-trait support |

| Functional Annotation | Chicken FAANG; Chicken GTEx; Animal QTLdb | Biological interpretation; Regulatory element annotation | Tissue-specific regulation; Comparative genomics; QTL integration |

| Specialized Populations | Advanced Intercross Lines (AILs); F2 crosses; Commercial and indigenous breeds | Fine-mapping; Genetic architecture studies | Enhanced recombination; Reduced LD; Phenotypic diversity |

Cross-Species Validation and Conservation of Genetic Mechanisms

Comparative genomic analyses reveal remarkable conservation of growth and reproductive pathways across avian and mammalian species. Studies of chicken growth genes have identified orthologous relationships with human developmental genes, highlighting fundamental biological pathways shared across vertebrate lineages [16]. For instance, IGF1 represents a conserved regulator of body size in both chickens and humans, while SOX5 influences developmental processes across diverse species [27]. However, regulatory mechanisms demonstrate both conserved and divergent features between mammals and birds, with species-specific elements contributing to unique phenotypic adaptations [16].

The chicken model provides particular value for understanding the functional genomics of economic traits, with advanced resources including the global chicken reference panel (GCRP), functional annotation datasets from the FAANG initiative, and regulatory maps from chicken GTEx projects [16]. These resources enable precise mapping of regulatory elements and their conservation across species, facilitating the identification of core biological pathways underlying growth, metabolism, and reproduction.

The integration of GWAS with meta-analysis has fundamentally transformed our understanding of complex polygenic traits in chickens, moving from single-gene discovery to comprehensive network-based understanding of biological systems. These approaches have successfully identified hundreds of genomic regions associated with economically important traits while revealing the complex regulatory architecture underlying phenotypic variation. Future research will increasingly focus on integrating multi-omics data, refining functional validation through genome editing, and developing improved statistical methods for cross-species translation of findings. As genomic resources continue to expand and analytical methods evolve, the power to unravel the genetic complexity of polygenic traits will further accelerate genetic improvement in poultry and enhance our fundamental understanding of biological systems across species.

In the pursuit of sustainable global food security, research into the genetic architecture of economically valuable traits in farmed animals has become paramount. For chickens, a vital source of protein and a key model organism, validating candidate genes requires leveraging large-scale public data resources. Three projects form the cornerstone of this research landscape: the ChickenGTEx Atlas, the Animal QTL Database (QTLdb), and the Functional Annotation of Animal Genomes (FAANG) project. Each provides distinct yet complementary data types and tools. This guide offers an objective comparison of these resources, framed within the context of validating candidate genes for complex economic traits, to aid researchers in selecting the most appropriate resources for their investigative workflows.

The table below summarizes the core attributes, strengths, and primary applications of the three resources to facilitate a direct comparison.

Table 1: Core Features of Chicken Genomic Resources

| Feature | ChickenGTEx Atlas | Animal QTL Database (QTLdb) | FAANG Project |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Mapping genetic variants that regulate molecular phenotypes (eQTLs, etc.) [28] | Cataloging published QTLs, associations, and candidate genes for complex traits [29] | Defining functional genomic elements (e.g., open chromatin, histone marks) in farmed animals [30] |

| Key Data Types | - Whole-genome sequencing (2,869 samples)- Bulk RNA-seq (7,015 samples, 28 tissues)- Single-cell RNA-seq (10 tissues)- Cis-molQTLs (~1.5 million)- Epigenomic profiles (257 datasets) [28] | - Curated QTLs from publications- GWAS associations- Candidate gene associations- Copy Number Variations (CNVs)- Breed information [29] | - Histone modification ChIP-seq- Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq)- DNA methylation- Gene expression (RNA-seq)- CAGE tags [30] |

| Number of Chicken QTLs/Associations | Millions of molecular QTLs (e.g., 2.97M cis-eQTLs) [28] | 29,328 QTL/association entries from 420 publications [29] | Not a QTL repository; provides foundational annotation for interpretation |

| Trait & Tissue Context | Focus on molecular phenotypes across 52 tissues; context-dependent QTLs (sex, tissue, cell-type) [28] | Diverse complex traits (e.g., growth, meat quality, egg production, disease) [29] | Foundational annotation across key tissues, cell types, and developmental stages [30] |

| Major Strength | Unravels the regulatory mechanism linking non-coding variants to transcriptomic diversity and phenotypes [28] | Comprehensive repository of genotype-to-phenotype associations; directly links genomic regions to measured complex traits [29] | Provides the foundational "rules" of the genome for interpreting the functional potential of genetic variants [30] |

| Consideration | Pilot phase; some tissues and biological contexts are under-represented [28] | Funding is uncertain; the database is no longer actively updated [29] | Data generation is often from a few individuals, limiting population-level inference [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Candidate Gene Validation

Candidate gene validation is a multi-step process. The following experimental frameworks, which synthesize typical methodologies from the literature, demonstrate how these resources can be integrated into a cohesive workflow.

Protocol 1: From GWAS Hit to Causal Gene and Variant

This protocol is ideal for fine-mapping a genomic region associated with a growth or production trait to identify the causal gene and its regulatory mechanism.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Genomic Validation Experiments

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|

| Advanced Intercross Line (AIL) Population | A chicken population with enhanced recombination for fine-mapping QTLs to very narrow genomic intervals [31]. |

| High-Quality Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Data | Provides a comprehensive set of genetic variants for association testing and imputation [28]. |

| Cis-molQTL Data (from ChickenGTEx) | Identifies which genetic variants are associated with changes in gene expression in specific tissues [28]. |

| Epigenomic Mark Data (from FAANG) | Annotates regulatory elements (e.g., promoters, enhancers) to prioritize variants in functional regions [30]. |

| Colocalization Analysis | A statistical method to determine if GWAS and QTL signals in a genomic region share a common causal variant [31]. |

Workflow Description: The process begins with a GWAS conducted on a population, such as an Advanced Intercross Line (AIL), to identify loci associated with a complex economic trait [31]. The resulting QTL interval is then cross-referenced with public QTLdb data to check for previously reported associations and evidence of pleiotropy [29]. Subsequent colocalization analysis is performed using ChickenGTEx cis-molQTL data (e.g., eQTLs, sQTLs) to test if the trait-associated variant also regulates a molecular phenotype, thereby nominating a candidate gene [31]. To establish a causal regulatory mechanism, the variant is examined within FAANG chromatin state annotations (e.g., H3K27ac for active enhancers, ATAC-seq for open chromatin) from relevant tissues [30]. Finally, the variant-to-gene-to-trait hypothesis can be functionally tested in vitro using systems like organoids [30].

Diagram 1: From GWAS Hit to Causal Gene

Protocol 2: Functional Annotation of a Prioritized Gene

This protocol is used when a candidate gene is already known, and the goal is to understand its regulatory landscape and potential role in complex traits.

Workflow Description: This pathway starts with a single prioritized candidate gene. Its expression profile is first characterized across a wide range of tissues using ChickenGTEx bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data, which helps identify the most relevant tissues and cell types for its function [28]. Next, its regulation is investigated by extracting all cis-molQTLs associated with the gene from ChickenGTEx, revealing genetic variants that modulate its expression or splicing [28]. The genomic region is then annotated using FAANG data to map its promoters, potential enhancers, and other regulatory features [30]. Finally, the gene's link to complex traits is established by checking for its presence in QTLdb records or by performing a Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS) using ChickenGTEx data, which connects gene expression to trait associations [28].

Diagram 2: Functional Annotation of a Gene

Supporting Experimental Data and Applications

The utility of these resources is best demonstrated through real-world research applications and performance benchmarks.

Case Study: Fine-Mapping Growth Traits in an Advanced Intercross Line

A 2025 study utilized a 16-generation chicken AIL to dissect the genetic architecture of growth traits [31]. This research exemplifies the power of combining specialized populations with public resources.

- Experimental Workflow: The researchers performed whole-genome sequencing on 4,671 samples across generations. They conducted GWAS for 75 complex traits, identifying 682 QTLs. Due to the high recombination in the AIL, the average QTL interval was fine-mapped to 244 ± 343 kb, a significant improvement in resolution [31].

- Data Integration for Validation: They used multiple colocalization methods to link these fine-mapped trait QTLs with regulatory variants, establishing a network of tissue-specific regulatory mutations. This systematic approach allowed them to move beyond simple association to propose functional mechanisms [31].

- Key Outcome: The study highlighted that 84.2% of the identified QTLs were less than 500 kb in length, and 20.38% of them were novel discoveries not present in the Animal QTLdb at the time, underscoring the value of such fine-mapping designs for expanding knowledge of trait genetics [31].

Performance of Statistical Methods for Complex Trait Analysis

The choice of statistical model significantly impacts the power and accuracy of GWAS, especially for complex longitudinal traits (e.g., growth over time). The table below compares different methods based on a simulation study.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of GWAS Models for Longitudinal Traits [32]

| GWAS Model | Description | False Positive Rate Control | Statistical Power | Estimation Accuracy of QTN effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fGWAS-C / fGWAS-F | Functional GWAS models fitting time-varied SNP effects [32] | Excellent (close to threshold) | Highest among all models | Most accurate, unbiased |

| GWAS-EBV-P / GWAS-DRP-P | Uses Estimated Breeding Value/Deregressed Proof as response, with polygenic effect [32] | Excellent (close to threshold) | Moderate | Underestimated |

| GWAS-Residual | Uses estimated residuals as response variable [32] | Conservative (lower than threshold) | Relatively High | Underestimated |

| GWAS-EBV-NP / GWAS-DRP-NP | Uses EBV/DRP as response, without polygenic effect [32] | Poor (clearly inflated) | High (but unreliable due to high FPR) | Underestimated |

Experimental Context: This simulation study evaluated methods for analyzing traits measured at multiple time points. The superior performance of the fGWAS models demonstrates the importance of using specialized statistical methods that can directly model the time-dependent nature of the phenotype, rather than relying on pre-processed summary values like EBVs [32].

The ChickenGTEx Atlas, Animal QTLdb, and FAANG project are powerful, complementary resources for the validation of candidate genes. FAANG provides the essential foundational annotation of the genome's regulatory grammar. The ChickenGTEx Atlas dynamically connects genetic variation to molecular phenotypes, revealing the cis-regulatory logic of the genome. The Animal QTLdb serves as a comprehensive repository of established genotype-to-complex-phenotype associations.

For researchers, the optimal strategy involves a synergistic use of all three. One can start with a QTL from the QTLdb, use FAANG data to annotate the region for functional elements, and then leverage ChickenGTEx to identify which of those elements have activity that is both variable and linked to the trait of interest through molQTLs. As the field moves towards higher resolution—embracing single-cell data, pangenomes, and in vitro functional models—these integrated resources will remain indispensable for accelerating precision breeding and understanding the fundamental biology of economically important traits in chickens.

Advanced Techniques for Gene Characterization and Functional Validation

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of genetic variants associated with complex traits and diseases. In chicken genomics, GWAS has revealed numerous quantitative trait loci (QTLs) influencing economically important traits such as egg production, body size, and disease resistance [27] [19]. However, despite these successes, significant challenges remain in moving from statistical associations to biological mechanisms. The majority of trait-associated variants fall in non-coding regions of the genome, making their functional interpretation difficult [33] [34]. Often, researchers assign function to the nearest gene, a method that frequently implicates incorrect genes and leads to weak assumptions about relevant molecular pathways [33].

The transition from single-layer genomic analyses to integrated multi-omics approaches represents a paradigm shift in biological research. By combining genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, researchers can now bridge the gap between genetic association and biological function [35] [34]. This integration is particularly valuable in agricultural genomics, where understanding the molecular basis of economic traits in chickens can accelerate breeding programs and improve animal health and productivity [27] [16]. The complex polygenic nature of most economic traits in chickens requires a systems biology approach that can capture the dynamic interactions between different molecular layers [16].

Methodological Framework: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

Correlation-Based Integration Methods

Correlation-based strategies apply statistical correlations between different types of omics data to uncover and quantify relationships between various molecular components. These methods create data structures, such as networks, to visually and analytically represent these relationships [35].

Gene Co-Expression Analysis with Metabolomics Data: This approach identifies co-expressed gene modules from transcriptomics data and links them to metabolites from metabolomics data. The correlation between metabolite intensity patterns and the eigengenes of each co-expression module can reveal which metabolites are strongly associated with specific gene modules, providing insights into the regulation of metabolic pathways [35].

Gene-Metabolite Network Analysis: This method visualizes interactions between genes and metabolites in a biological system. Researchers collect gene expression and metabolite abundance data from the same biological samples and integrate them using correlation analyses to identify co-regulated genes and metabolites. These networks help identify key regulatory nodes and pathways involved in metabolic processes [35].

Similarity Network Fusion: This technique builds a similarity network for each omics data type separately, then merges all networks, highlighting edges with high associations in each omics network [35].

Machine Learning Integration Approaches

Machine learning strategies utilize one or more types of omics data to comprehensively understand biological responses at classification and regression levels. These methods enable identification of complex patterns and interactions that might be missed by single-omics analyses [35].

Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA): A machine learning framework that captures latent factors driving variation across multiple omics layers, identifying shared and specific patterns of variation [36].

Sparse Partial Least-Squares Discriminant Analysis (sPLS-DA): This method has been successfully used to integrate proteomic and metabolomic data, enabling segregation of subjects with specific conditions from healthy controls when principal component analysis fails to separate groups [37].

Combined Omics Integration Approaches

These approaches attempt to explain what occurs within each type of omics data in an integrated manner, generating independent data sets that can be jointly interpreted [35].

Pathway Integration: Combining proteomic signals with metabolomic readouts makes pathway analysis more accurate and reduces false positives in enrichment studies. A pathway supported by both protein abundance and metabolite concentration changes is more likely to be biologically relevant [36].

Constraint-Based Models: These models integrate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data with genome-scale metabolic models to predict metabolic fluxes and identify key regulatory nodes [35].

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

| Integration Approach | Key Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Gene co-expression analysis, Gene-metabolite networks, Similarity Network Fusion | Identifies co-regulation patterns, Visualizes complex relationships | May detect correlations without causal relationships, Sensitive to data normalization |

| Machine Learning | MOFA, sPLS-DA, MixOmics | Identifies complex non-linear patterns, Handles high-dimensional data | Requires substantial computational resources, Risk of overfitting without proper validation |

| Pathway-Centric | Pathway enrichment, Constraint-based models | Provides biological context, Leverages prior knowledge | Dependent on completeness of pathway databases, May miss novel mechanisms |

Experimental Designs and Workflows for Multi-Omics Studies

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful multi-omics integration. For studies integrating proteomics and metabolomics, joint extraction protocols that enable simultaneous recovery of proteins and metabolites from the same biological material are preferred [36]. This approach minimizes technical variation and ensures that different molecular layers are captured from the same biological context. Samples should be processed rapidly on ice to minimize degradation, and internal standards should be included to allow accurate quantification across runs [36].

The experimental design must account for the specific requirements of each omics technology. For transcriptomics, RNA integrity is paramount, while proteomics requires preservation of protein modifications and prevention of degradation. Metabolomics demands immediate quenching of metabolic activity to capture accurate snapshots of metabolite levels [38] [36]. For chicken studies, careful consideration of tissue selection, developmental stage, and environmental conditions is essential, as these factors significantly influence molecular profiles [27] [16].

Data Acquisition Technologies

Transcriptomics: RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides comprehensive profiling of transcript abundance. Bulk RNA-Seq measures average expression across cell populations, while single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) resolves cellular heterogeneity [35] [34].

Proteomics: Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables identification and quantification of thousands of proteins. Data-independent acquisition (DIA) strategies offer high reproducibility and broad proteome coverage, while tandem mass tags (TMT) enable multiplexed quantification across multiple samples [36] [34].

Metabolomics: Both gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) are widely used. GC-MS provides excellent resolution for volatile compounds, while LC-MS offers broader metabolite coverage, including lipids and polar metabolites [38] [36].

Data Processing and Integration Workflows

Data processing typically involves multiple steps: (1) quality control of raw data; (2) preprocessing including normalization, transformation, and missing value imputation; (3) batch effect correction to minimize technical variation; and (4) statistical integration [35] [36]. Normalization techniques such as log-transformation, quantile normalization, or variance stabilization help harmonize datasets with different scales and dynamic ranges [36].

Figure 1: Multi-Omics Integration Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a typical multi-omics study, from sample collection through data acquisition, preprocessing, integration, and biological interpretation.

Case Studies in Chicken Genomics

Advanced Intercross Line for Growth Traits

A sophisticated example of multi-omics integration in chicken genomics comes from a 16-generation advanced intercross line (AIL) study designed to enhance informative recombination and identify single-gene quantitative trait loci [16]. This resource population, established through reciprocal crosses between Huiyang Bearded chickens and High-Quality Chicken Line A, accumulated recombination events over generations, dramatically improving mapping resolution.

Researchers collected 4,671 samples across different generations for genome sequencing and phenotyping of 75 traits, including growth and development, tissue and carcass characteristics, feed intake and efficiency, blood biochemistry, and feather characteristics [16]. By integrating GWAS with molecular QTL mapping and epigenetic feature annotation, they established a network landscape of tissue-specific regulatory mutations and functional gene relationships. This systems genetics approach revealed that complex traits in chickens are driven by the accumulation of minor effects on tissue-specific genes and regulatory pathways, consistent with the omnigenic model [16].

Egg Number Traits Across Diverse Populations

A genome-wide association study investigating egg number traits utilized genomic information from various chicken breeds differing in average annual egg production [19]. The study compared commercial egg-type chickens with high production (approximately 300 eggs annually) against Chinese indigenous chickens with lower production (less than 200 eggs annually).

The research identified 148 SNPs associated with egg number traits and 32 candidate genes based on gene function [19]. These genes were primarily involved in regulating hormones, follicle formation and development, and reproductive system development. Key candidates included:

- NELL2: Involved in neural development and fertility

- KITLG: Essential for germ cell development

- GHRHR: Regulates growth hormone release

- CAMK4: Plays roles in calcium signaling and fertility