Comparative Analysis of Structural Variants in Mosquito Genomes: Insights for Vector Biology and Disease Control

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of structural variants (SVs) in mosquito genomes, exploring their impact on vector biology, evolution, and disease transmission mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis of Structural Variants in Mosquito Genomes: Insights for Vector Biology and Disease Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of structural variants (SVs) in mosquito genomes, exploring their impact on vector biology, evolution, and disease transmission mechanisms. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we examine foundational genomic architecture across Anopheles species, evaluate cutting-edge SV detection methodologies from short-read to long-read sequencing, address troubleshooting in complex repetitive regions, and present validation through comparative phylogenomics. The synthesis highlights how SV research enables innovative vector control strategies, including CRISPR-based gene drives, and outlines future directions for translating genomic discoveries into clinical applications against mosquito-borne diseases like malaria.

Unraveling Mosquito Genome Architecture: Structural Variants as Drivers of Evolution and Adaptation

Structural variants (SVs) represent a significant class of genetic mutations that include large deletions, insertions, inversions, and translocations. In disease vectors like mosquitoes, these variants play crucial roles in genome evolution, adaptation, and potentially in vector competence. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches for SV detection, focusing on their applications in mosquito genomics research. We evaluate the performance of leading protocols based on sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation requirements, providing researchers with objective data to select appropriate methodologies for their specific research objectives.

Experimental Protocols for SV Detection

Hi-C for Chromatin Architecture and SV Analysis

Principle: Hi-C (High-throughput Chromosome Conformation Capture) identifies genome-wide chromatin interactions by crosslinking spatially proximal DNA regions, followed by sequencing and computational reconstruction of three-dimensional genome organization. This method can reveal SVs through distinctive patterns in interaction maps [1].

Detailed Protocol:

- Crosslinking: Use 1-2% formaldehyde to fix 15-18 hour mosquito embryos or adult tissue for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells and digest chromatin with a restriction enzyme (e.g., DpnII, HindIII, or MboI).

- Fill-in and Marking: Fill in restriction fragment overhangs with nucleotides containing biotin.

- Ligation: Perform proximity ligation under dilute conditions to favor junctions between crosslinked fragments.

- Reverse Crosslinking: Purify DNA and remove biotin from unligated ends.

- Shearing and Pull-down: Shear DNA to 300-500 bp fragments and isolate biotin-labeled ligation junctions using streptavidin beads.

- Library Prep and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries and perform paired-end sequencing on Illumina platforms (aim for 60-194 million alignable reads as in [1]).

Data Analysis: Process reads using pipelines like 3D-DNA or Juicer. Align to a reference genome, filter PCR duplicates, and generate contact matrices. Identify SVs from abnormal contact patterns (e.g., "butterfly" patterns for inversions) and assemble using tools like 3D-DNA.

Structural Variant Search (SVS) for Low-Abundance SVs

Principle: SVS detects ultra-rare, non-clonal somatic SVs from low-coverage sequencing data by leveraging a chimera-free library protocol and a non-consensus split-read algorithm, requiring only a single supporting read [2].

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high molecular weight DNA from mosquito samples (e.g., whole adults or specific tissues).

- Chimera-free Library Prep: Use the MuPlus transposon-based library preparation protocol to avoid ligation-mediated artifacts.

- Sequencing: Sequence on platforms like Ion Proton with low coverage (~0.3x per library). Multiplex 6-12 libraries per run.

- SV Calling:

- Step 1 - Identification: Use a split-read approach to find potential SV breakpoints.

- Step 2 - Filtering: Remove potential technical and mapping artifacts.

- Step 3 - Classification: Distinguish somatic from germline SVs by identifying variants recurring in independent libraries (germline) versus unique events (somatic).

Data Analysis: Manually inspect split reads for breakpoint microhomology (≥5 nt). An elevated microhomology frequency in treated samples (e.g., 4.9% for bleomycin) suggests specific DNA repair mechanisms [2].

Comparative Performance Analysis of SV Detection Methods

The following tables summarize the quantitative performance and operational characteristics of the primary SV detection methods discussed.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Metrics of SV Detection Methods

| Method | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Variant Size Range | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hi-C for SV Detection | Not explicitly quantified for SVs | Identifies polymorphic inversions via "butterfly" patterns [1] | Large SVs (>10 kb) | Can detect heterozygous inversions in populations [1] |

| SVS (Structural Variant Search) | 36.2% (for CaSki HPV integrations) [2] | 95% (for CaSki HPV integrations) [2] | >200 nt (to avoid polymerase slippage) [2] | 47 SVs per cell at ~0.3x sequencing coverage [2] |

| Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., ONT) | Varies by caller and size; higher for ≥250 bp SVs [3] | FDR: 6.91% (deletions ≥250 bp), 19.14% (deletions <250 bp) [3] | 50 bp - Several kb | Not explicitly stated |

Table 2: Operational and Application Characteristics

| Method | Required Input Material | Typical Coverage | Key Applications in Mosquito Research | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hi-C for SV Detection | 15-18 h embryos or adult mosquitoes [1] | 60-194 million unique alignable reads [1] | - Chromosome-level scaffolding- Inversion polymorphism detection- 3D genome evolution studies [1] | - Complex data analysis- High sequencing depth required- Distinguishing topological boundaries from SVs |

| SVS (Structural Variant Search) | High molecular weight DNA [2] | Ultra-low coverage (~0.3x per library) [2] | - Quantifying clastogen-induced somSVs- Studying SV spectra under different insults [2] | - Requires specialized MuPlus protocol- Lower absolute sensitivity- Distinguishing unique somatic events from artifacts |

| Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., ONT) | High molecular weight DNA [3] | Intermediate coverage (median 16.9x) [3] | - Population-scale SV discovery- MEI and complex SV characterization [3] | - High DNA quantity/quality needs- Computational resources for analysis |

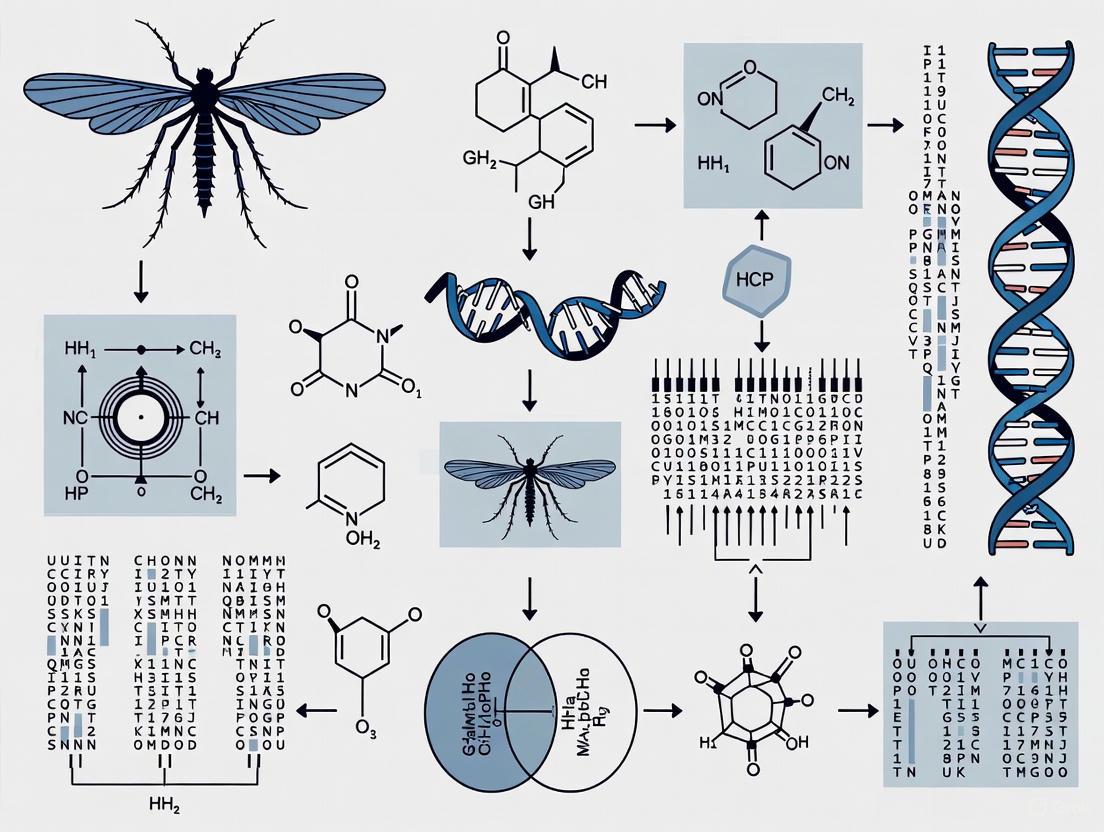

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the key experimental protocols discussed, providing researchers with clear procedural overviews.

Hi-C Workflow for 3D Genome and SV Analysis

SVS Workflow for Low-Abundance SVs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for SV Studies in Mosquito Vectors

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde (1-2%) | Crosslinking agent for spatial genome organization | Fixing chromatin conformations in mosquito embryos for Hi-C [1] |

| Restriction Enzymes (DpnII, MboI, HindIII) | Digest crosslinked DNA into manageable fragments | Creating cohesive ends for biotin fill-in during Hi-C library prep [1] |

| Biotin-dNTPs | Labeling DNA ends for selective purification | Marking ligation junctions in Hi-C to pull down chimeric fragments [1] |

| Streptavidin Beads | Affinity purification of biotinylated molecules | Isulating biotin-labeled ligation products in Hi-C protocol [1] |

| MuPlus Transposase | Fragmentation and adapter ligation without chemical ligation | Creating chimera-free sequencing libraries for SVS to reduce false positives [2] |

| Clastogens (e.g., Bleomycin, Etoposide) | Inducing DNA double-strand breaks | Generating positive control somatic SVs for assay validation in mosquito cells [2] |

| PacBio HiFi / ONT Ultra-Long Reads | Long-read sequencing technologies | Resolving complex genomic regions and SVs in mosquito genome assemblies [4] [3] |

The comparative analysis of structural variant detection methods reveals a trade-off between resolution, sensitivity, and throughput in mosquito genomics research. Hi-C provides unparalleled insights into 3D genome architecture and large inversions but requires specialized computational expertise. SVS offers unique capability for quantifying low-frequency somatic variants but has lower absolute sensitivity. Emerging long-read sequencing technologies show promise for comprehensive SV discovery, though their application in mosquitoes currently lags behind human genomics. The optimal methodological choice depends critically on the specific research question—whether investigating population-level polymorphisms, rare somatic events, or evolutionary structural genomics. Future directions will likely involve integrating these complementary approaches to fully elucidate the functional impact of structural variants on mosquito vector competence and genome evolution.

Chromatin Organization and 3D Genome Architecture in Anopheles Species

The study of three-dimensional (3D) genome architecture has emerged as a crucial frontier in understanding gene regulation in malaria vectors. 3D chromatin organization refers to the spatial arrangement of genetic material within the nucleus, a hierarchical structure encompassing chromosome territories, domains, and subdomains that profoundly influence gene expression [5]. While principles of chromatin organization have been extensively studied in model organisms like Drosophila melanogaster, research in Anopheles mosquitoes has accelerated recently, revealing both conserved features and unique evolutionary adaptations [5] [6]. This architectural framework plays a pivotal role in vector competence, environmental adaptation, and insecticide resistance—factors that directly impact malaria transmission dynamics. The comparative analysis of chromatin organization across multiple Anopheles species provides not only fundamental biological insights but also potential avenues for novel vector control strategies by uncovering the regulatory genome underlying mosquito biology and parasite interactions.

Experimental Approaches for Mapping 3D Genome Architecture

Core Methodological Frameworks

Investigating 3D genome organization in Anopheles species relies on a suite of complementary technologies that collectively provide a multi-scale view of chromatin architecture. Hi-C, a high-throughput derivative of chromosome conformation capture (3C), serves as the cornerstone method, enabling genome-wide profiling of chromatin interactions through crosslinking, digestion, ligation, and sequencing of spatially proximate DNA fragments [6]. This approach has been instrumental in generating chromosome-level assemblies for multiple Anopheles species, overcoming challenges posed by highly repetitive DNA clusters that traditional sequencing methods struggle to resolve [6]. The integration of Hi-C with PacBio long-read sequencing has proven particularly powerful for de novo genome assembly, as demonstrated in studies of An. coluzzii, An. merus, and An. stephensi [6].

Supplementary techniques provide critical validation and functional insights. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) enables direct visualization of chromosomal territories and specific genomic loci within intact nuclei, confirming organizational patterns observed in Hi-C data [5] [6]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) maps the genomic distribution of histone modifications and chromatin-associated proteins, revealing epigenetic signatures that correlate with architectural features [6]. Additionally, RNA-seq profiles transcriptional outputs, allowing researchers to connect spatial genome organization with gene expression patterns [6]. This multi-modal approach has been successfully applied across five Anopheles species representing approximately 100 million years of evolutionary divergence, providing an unprecedented comparative view of mosquito chromatin architecture [6].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for comparative 3D genome analysis in Anopheles species:

Comparative Analysis of 3D Genome Features Across Anopheles Species

Fundamental Organizational Principles

Comprehensive comparative studies across five Anopheles species representing approximately 100 million years of evolutionary divergence have revealed both conserved and divergent features of 3D genome architecture [6]. All examined species display a Rabl-like configuration, where centromeres and telomeres attach to opposite nuclear poles, potentially reducing DNA entanglement [5]. This organization is characterized by the partitioning of genomes into chromosomal territories corresponding to the X, 2R, 2L, 3R, and 3L arms, with intra-chromosomal interactions dominating over inter-chromosomal contacts [6]. The compartmentalization of chromatin into active (A) and inactive (B) compartments follows principles observed in other eukaryotes, with A-compartments enriched in expressed genes and open chromatin marks, while B-compartments associate with heterochromatic regions and gene repression [6].

Unlike mammalian systems where CTCF-mediated loop extrusion plays a dominant organizational role, Anopheles genomes appear to rely more heavily on compartment-driven segregation of active and repressed chromatin [6]. This mechanism shares similarities with Drosophila but exhibits distinct features, including the identification of extremely long-ranged looping interactions that have remained conserved for approximately 100 million years [6]. These stable long-range loops operate through mechanisms distinct from Polycomb-dependent interactions or clustering of active chromatin, suggesting mosquito-specific innovations in genome folding [6]. The conservation of these architectural principles across diverse Anopheles lineages indicates fundamental functional importance, potentially related to developmental gene regulation or environmental response mechanisms critical for vectorial capacity.

Quantitative Comparison of Genomic and Architectural Features

Table 1: Genomic Features and Hi-C Sequencing Metrics Across Anopheles Species

| Species | Subgenus | Assembly Version | Hi-C Reads (Millions) | Synteny Block Conservation | Chromosomal Inversions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. coluzzii | Cellia | AcolN2 | 194 | 93% (vs. An. merus) | 2.8-16 Mb polymorphic |

| An. merus | Cellia | AmerM5 | 168 | 93% (vs. An. coluzzii) | Multiple detected |

| An. stephensi | Cellia | AsteI4 | 158 | ~70% (vs. An. coluzzii) | 2Rb polymorphism |

| An. atroparvus | Anopheles | AatrE4 | 142 | ~45% (vs. An. coluzzii) | Species-specific |

| An. albimanus | Nyssorhynchus | AalbS4 | 60 | ~19% (vs. An. coluzzii) | Distinct patterns |

Table 2: Conserved Long-Range Chromatin Loops in Anopheles Genomes

| Genomic Feature | Evolutionary Conservation | Functional Association | Mechanistic Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely long-range loops | ~100 million years | Unknown regulatory functions | Non-Polycomb, non-active chromatin |

| TAD-like domains | Retained within synteny blocks | Gene expression regulation | Compartment-driven segregation |

| Inversion breakpoints | Associated with boundaries | Chromosomal rearrangements | "Butterfly" contact patterns |

| X-chromosome organization | Reduced synteny block size | Rapid evolution | Elevated gene shuffling |

Relationship Between Genome Architecture and Structural Variants

Chromosomal Rearrangements and 3D Folding

The interplay between structural variants and 3D genome organization represents a crucial aspect of Anopheles evolutionary genomics. Hi-C contact maps have revealed that balanced inversions produce distinctive "butterfly" patterns due to the reorganization of spatial contacts within rearranged chromosomal segments [6]. These polymorphic inversions, ranging from 2.8 to 16 Mb in length, have been identified across multiple species, with the 2Rb inversion in An. stephensi representing a particularly well-characterized example [7] [6]. This 16.5 Mbp inversion exists in three genotypes—homozygous standard (2R+b/2R+b), heterozygous (2R+b/2Rb), and homozygous inverted (2Rb/2Rb)—with differential associations to ecological adaptation and insecticide resistance [7].

Comparative analyses demonstrate that synteny breakpoints between species are frequently enriched in regions of increased genomic insulation, suggesting a potential relationship between chromatin architecture and chromosomal rearrangement hotspots [6]. However, detailed investigation has revealed a confounding effect of gene density on both insulation and breakpoint distribution, indicating limited causal relationship between insulation and rearrangement predisposition [6]. The X chromosome exhibits notably smaller synteny blocks compared to autosomes across all species comparisons, consistent with previously observed elevated gene shuffling rates on this chromosome [6] [8]. This accelerated structural evolution may reflect distinctive organizational constraints or adaptive pressures on sex chromosomes.

Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) in Mosquito Genomes

The organization of Anopheles genomes into topologically associating domains (TADs) represents a fundamental level of 3D genome architecture that facilitates specific enhancer-promoter interactions while insulating neighboring regulatory landscapes [9]. While comprehensive TAD annotation across Anopheles species remains ongoing, studies have revealed both similarities and distinctions compared to other model insects. Unlike mammals where CTCF-mediated loop extrusion drives TAD formation, Anopheles TADs appear more dependent on compartment-driven mechanisms similar to those observed in Drosophila [6]. However, comparative analyses indicate that chromatin architecture demonstrates remarkable stability within synteny blocks over evolutionary timescales, with TAD-like structures potentially retained for tens of millions of years [6].

The relationship between TAD organization and chromosomal rearrangements reveals important evolutionary dynamics. Synteny breakpoints show enrichment at TAD boundaries, consistent with patterns observed in both vertebrate and Drosophila lineages [9] [6]. This association may reflect increased susceptibility to double-strand breaks in regions under topological stress, providing mechanistic insight into chromosomal rearrangement processes [9]. Despite this enrichment, the functional conservation of TAD organization appears substantial, with studies demonstrating that 3D chromatin contacts remain notably stable within syntenic blocks even as linear genome sequences diverge [6]. This preservation suggests selective maintenance of spatial genome organization likely due to functional constraints on gene regulation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Architecture Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Anopheles Chromatin Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Application | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Hi-C Library Kits | 3D chromatin interaction profiling | Genome-wide mapping of spatial contacts |

| PacBio Sequel System | Long-read sequencing | De novo genome assembly improvement |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kits | Epigenetic mark mapping | Protein-DNA interaction analysis |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | Transcriptome profiling | Gene expression correlation with architecture |

| Anopheles Genome Assemblies | Reference sequences | Comparative genomic analysis |

| 3D-DNA Pipeline | Hi-C data analysis | Chromosome-level scaffolding |

| BUSCO Tools | Assembly completeness assessment | Quality validation of genome assemblies |

Functional Implications and Evolutionary Dynamics

Regulatory Consequences of 3D Genome Organization

The 3D architecture of Anopheles genomes has profound implications for gene regulation and phenotypic expression. Spatial genome organization facilitates specific enhancer-promoter interactions that coordinate developmental gene expression, immune responses, and environmental adaptations [5] [9]. Studies of the An. gambiae bithorax complex (Hox genes) have revealed conserved regulatory landscapes with insulator elements that orchestrate precise spatiotemporal expression patterns, highlighting the functional importance of chromatin folding for proper development [5]. These architectural features enable mosquitoes to maintain transcriptional precision despite high genetic diversity and strong anthropogenic selection pressures, including insecticide exposure [10].

The relationship between chromatin architecture and insecticide resistance represents a particularly compelling research direction. Genome-wide analyses have documented extensive genetic variation in natural populations, with 57 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms and numerous copy number variants identified across 1142 wild-caught mosquitoes from 13 African countries [10]. These genetic variations are embedded within specific 3D architectural contexts that likely influence their phenotypic expression. For instance, the 2Rb inversion in An. stephensi has been implicated in adaptation to environmental heterogeneity and potentially resistance phenotypes, though the precise mechanistic connections between spatial genome organization and resistance evolution require further investigation [7].

Evolutionary Conservation and Innovation

Comparative analyses across Anopheles species reveal a complex landscape of evolutionary conservation and innovation in 3D genome architecture. On one hand, certain features exhibit remarkable stability over deep evolutionary timescales—extremely long-range looping interactions have persisted for approximately 100 million years, suggesting crucial functional roles that maintain these spatial configurations despite extensive sequence divergence [6]. Similarly, chromatin architecture within synteny blocks remains largely conserved, with contact patterns retained through tens of millions of years of evolution [6]. This preservation indicates strong selective constraints on spatial genome organization, likely due to impacts on essential gene regulatory functions.

Conversely, the X chromosome demonstrates accelerated evolutionary dynamics in both sequence and architecture. Compared to autosomes, the X chromosome exhibits smaller synteny blocks and elevated rearrangement rates across all species comparisons [6] [8]. This distinctive evolutionary pattern may reflect different selective pressures, mutation rates, or recombination dynamics on sex chromosomes. The presence of species-specific inversions and structural variants further highlights the dynamic nature of mosquito genomes, with chromosomal rearrangements potentially serving as substrates for ecological adaptation and speciation [6]. These evolutionary dynamics occur within a framework of general architectural conservation, illustrating how both stability and change in 3D genome organization have shaped Anopheles diversity and vectorial capacity.

Transposable Elements and Repeat Landscapes in Mosquito Genomes

In the field of mosquito genomics, understanding repetitive elements—particularly transposable elements (TEs) and structural variants (SVs)—is crucial for unraveling the evolutionary mechanisms underlying mosquito adaptation, insecticide resistance, and disease transmission capacity. Mosquito genomes, like those of other eukaryotes, contain substantial repetitive content that significantly influences genome architecture, size, and function [11]. These repetitive components include both transposable elements, which can move within the genome, and satellite DNA, which forms tandem repeats [11]. The comprehensive analysis of these elements, known as the "repeatome," provides critical insights into mosquito genome evolution and its functional consequences [11].

Recent research has highlighted the dynamic nature of repetitive elements in mosquito genomes, revealing their substantial contributions to adaptive evolution. For instance, in the invasive urban malaria vector Anopheles stephensi, genome structural variants have been shown to play a pivotal role in adaptations to environmental challenges and insecticides [12]. These findings underscore the importance of comparative analyses of TE landscapes across mosquito species, which can reveal patterns of genome evolution directly relevant to vector control strategies and drug development efforts.

Comparative Analysis of Repetitive Element Diversity

Methodological Framework for Comparative Analysis

The comparative analysis of transposable elements across mosquito genomes requires standardized methodologies to ensure valid interspecies comparisons. Current approaches utilize multiple bioinformatic pipelines to identify and classify repetitive elements, with Earl Grey and RepeatModeler2/RepeatMasker emerging as widely adopted tools [13]. These pipelines employ a combination of library-based, signature-based, and de novo approaches to characterize TE diversity and abundance [13].

Long-read sequencing technologies have revolutionized repeat element analysis by enabling more accurate resolution of highly repetitive genomic regions that were previously challenging to assemble [13]. For TE classification, elements are broadly categorized based on their replication mechanisms: Class I elements (retrotransposons, including LTR and non-LTR elements) replicate via an RNA intermediate using a "copy-and-paste" mechanism, while Class II elements (DNA transposons) typically employ a "cut-and-paste" mechanism, though some like Helitrons use a rolling-circle replication strategy [13] [14].

Quantitative Comparison of Repetitive Elements Across Insect Genomes

Table 1: Comparative Repeatome Statistics Across Insect Species

| Species | Family/Order | Genome Size | Total Repetitive Content | Key Dominant TE Types | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anopheles stephensi (invasive population) | Diptera (Culicidae) | Not specified | 2,988 duplications and 16,038 deletions of SVs identified | Duplications associated with insecticide resistance | [12] |

| Xylocopa violacea | Hymenoptera (Apidae) | Not specified | 82.1% | Not specified | [13] |

| Apis dorsata | Hymenoptera (Apidae) | Not specified | 4.4% | Not specified | [13] |

| Saussurella cornuta | Orthoptera (Tetrigidae) | 2.836 Gb | 60.86% | LINEs, LTR/Gypsy, LTR/Copia, DNA transposons | [11] |

| Thoradonta yunnana | Orthoptera (Tetrigidae) | 1.044 Gb | 42.82% | LINEs, LTR/Gypsy, LTR/Copia, DNA transposons | [11] |

| Antarctic midge | Diptera (Chironomidae) | Not specified | ~1% | Not specified | [14] |

| Morabine grasshoppers | Orthoptera (Acrididae) | Not specified | ~75% | Not specified | [14] |

Table 2: Transposable Element Classification and Characteristics

| TE Category | Transposition Mechanism | Key Structural Features | Representative Examples | Impact on Genome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (Retrotransposons) | Copy-and-paste via RNA intermediate | |||

| LTR Retrotransposons | Reverse transcription with RNA intermediate | Long terminal repeats | Gypsy, Copia | Significant impact on genome size expansion |

| Non-LTR Retrotransposons | Reverse transcription with RNA intermediate | Lack long terminal repeats | LINEs, SINEs | Insertional mutations, regulatory changes |

| Class II (DNA Transposons) | Cut-and-paste or peel-and-paste | |||

| TIR Transposons | Cut-and-paste | Terminal inverted repeats, transposase gene | Various DNA transposons | Excision and reinsertion events |

| Helitrons | Peel-and-paste (rolling circle) | No terminal inverted repeats, RepHel protein | Helitrons | Gene sequence capture and amplification |

The data reveal striking variation in repetitive element content across insect genomes, with notable implications for genome size and organization. While comprehensive quantitative data specifically for major mosquito species is limited in the available literature, the patterns observed in related insect groups suggest that similar dynamics likely operate in mosquito genomes. The high-frequency structural variants in Anopheles stephensi demonstrate the adaptive potential of these genomic features in malaria vectors [12].

Experimental Methodologies for Repeatome Analysis

Genome-Wide Structural Variant Detection

The identification of structural variants in mosquito genomes employs sophisticated computational approaches applied to whole genome sequencing data. In a recent study of Anopheles stephensi, researchers analyzed 115 mosquitoes from both invasive island populations and ancestral mainland India locations [12]. The methodology involved comprehensive genome sequencing followed by specialized bioinformatic analyses to detect structural variants including duplications and deletions.

The analytical workflow for SV detection typically employs tools like CNVnator, which specializes in discovering, genotyping, and characterizing typical and atypical copy number variations from population genome sequencing [12]. For selective sweep analysis—identifying genomic regions under recent positive selection—methods such as RAiSD are employed, which detects multiple signatures of selective sweeps using SNP vectors [12]. These approaches allow researchers to distinguish neutral structural variants from those potentially contributing to adaptive evolution.

Transposable Element Annotation and Characterization

The characterization of transposable elements follows established bioinformatic pipelines optimized for repetitive element annotation. As demonstrated in large-scale bee genome analyses, the Earl Grey and RepeatModeler2/RepeatMasker pipelines provide complementary approaches for TE annotation [13]. While both yield consistent estimates of total repeat content, Earl Grey has been shown to classify a significantly greater proportion of repetitive elements, making it particularly valuable for comprehensive repeatome characterization [13].

For species without high-quality reference genomes, alternative approaches like RepeatExplorer2 and dnaPipeTE can be applied to low-coverage short-read data to identify genomic repeats, including transposable elements and satellite DNA [11]. These tools employ graph-based clustering of reads to reconstruct repetitive sequences without requiring a reference assembly, making them accessible for non-model organisms.

Phylogenetic Analysis Using Repetitive Elements

Beyond their functional implications, transposable elements have emerged as valuable phylogenetic markers, particularly for resolving relationships at lower taxonomic levels. As demonstrated in Drosophiloidea, TE-based phylogenies can effectively distinguish closely related species, with improved accuracy when using TEs exhibiting strong phylogenetic signals (Retention Index > 0.5) [14]. The methodology involves identifying species-specific TE families, quantifying their copy numbers across species, and constructing phylogenetic trees based on TE presence/absence patterns using Maximum Parsimony, Maximum Likelihood, and Bayesian Inference methods [14].

This approach has shown particular utility for species delimitation and for resolving relationships where traditional markers provide insufficient resolution. Notably, studies have found no significant difference in TE performance between genomes generated by next-generation and third-generation sequencing platforms, enhancing the methodological flexibility for mosquito phylogenetic studies [14].

Functional Implications of Repetitive Elements in Mosquito Biology

Adaptive Evolution and Insecticide Resistance

Structural variants and transposable elements play crucial roles in mosquito adaptation to environmental challenges, particularly insecticide pressure. Research on Anopheles stephensi has revealed candidate duplication mutations associated with recurrent evolution of resistance to diverse insecticides [12]. These mutations exhibit distinct population genetic signatures of recent adaptive evolution, suggesting different mechanisms of rapid adaptation involving both hard and soft selective sweeps that enable mosquito populations to thwart chemical control strategies [12].

The functional significance of these SVs is underscored by their enrichment in genomic regions with signatures of selective sweeps, despite the general tendency for structural variants to be more deleterious than amino acid polymorphisms [12]. This pattern highlights how a subset of SVs with adaptive value can rise to high frequency through positive selection, contributing to the evolutionary success of invasive mosquito populations.

Environmental Adaptation and Invasive Success

Repetitive elements also contribute to ecological adaptations that facilitate mosquito range expansion and invasion success. In Anopheles stephensi, researchers have identified candidate structural variants associated with larval tolerance to brackish water, representing a crucial adaptation in island and coastal populations [12]. This finding demonstrates how TE-mediated genomic variation can enable colonization of new ecological niches by altering physiological tolerances.

Notably, nearly all high-frequency structural variants and candidate adaptive variants in invasive island populations of Anopheles stephensi are derived from mainland populations, suggesting a substantial contribution of standing genetic variation to invasion success rather than solely relying on new mutations [12]. This pattern emphasizes the importance of characterizing repetitive element diversity across the native range of mosquito species to predict and manage future invasion pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions for TE Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for TE Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Earl Grey | De novo repeat annotation | Comprehensive TE identification and classification |

| RepeatModeler2/RepeatMasker | Library-based repeat identification | Comparative repeat masking across species | |

| CNVnator | Structural variant discovery and genotyping | Detection of CNVs from population sequencing data | |

| RAiSD | Selective sweep detection | Identification of genomic regions under selection | |

| Analytical Frameworks | RepeatExplorer2 | Graph-based repeat characterization | TE analysis without reference genome |

| dnaPipeTE | Repeat content estimation from low-coverage data | Rapid assessment of repeat composition | |

| Experimental Resources | Whole genome sequencing data | Variant discovery and genotyping | Population genomic analyses of TEs and SVs |

| Mitochondrial genomes (MitoZ) | Phylogenetic framework | Evolutionary analysis of TE dynamics |

The comparative analysis of transposable elements and repeat landscapes in mosquito genomes reveals the dynamic evolutionary processes shaping vector biology and disease transmission potential. Methodological advances in genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis have enabled researchers to move beyond simply documenting TE abundance to understanding the functional consequences of this genomic variation. The evidence from Anopheles stephensi demonstrates how structural variants and repetitive elements contribute to adaptive traits including insecticide resistance and environmental tolerance, highlighting their importance in vector control strategies.

Future research directions should include more comprehensive comparative analyses across major malaria vector species, integrated functional validation of candidate adaptive TEs, and development of targeted approaches to manipulate repetitive elements for vector control. As methodological approaches continue to advance, the study of transposable elements in mosquito genomes will undoubtedly yield further insights into vector evolution and novel opportunities for intervention.

Synteny Blocks and Chromosomal Rearrangements Across Mosquito Phylogeny

The study of genomic architecture, specifically the conservation of synteny blocks and the occurrence of chromosomal rearrangements, provides critical insights into the evolutionary history, adaptive processes, and functional genomics of mosquito vectors. Comparative genomic analyses across multiple Anopheles species have revealed that chromosomes are hierarchically folded within cell nuclei, and patterns observed on chromatin interaction maps are closely associated with evolutionary dynamics, epigenetic profiles, and gene expression levels [1]. Understanding these elements is not only fundamental to evolutionary biology but also has practical implications for vector control, as chromosomal rearrangements are implicated in insecticide resistance and adaptation to environmental stresses [15] [16].

Mosquitoes of the family Culicidae are evolutionarily ancient, with the Anophelinae and Culicinae subfamilies diverging approximately 147–213 million years ago (MYA) [15]. Despite this deep divergence, the karyotype (chromosome number) is remarkably conserved; most mosquito species possess six chromosomes (2n=6) [15]. However, genome composition, including chromosome arm associations (e.g., whole-arm translocations) and size, differs dramatically between subfamilies, driven by large-scale structural variations [15]. The study of synteny and rearrangements allows researchers to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships, trace migration routes, and identify genomic regions associated with epidemiologically important traits.

Methodologies for Delineating Synteny and Rearrangements

Advanced sequencing technologies and bioinformatic pipelines are required to detect and validate structural variants (SVs), which include chromosomal rearrangements such as inversions, translocations, and copy number variants [17] [18]. The following section details the key experimental and computational protocols used in contemporary mosquito genomics research.

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Generating high-quality, chromosome-level genome assemblies is the foundational step for comparative analysis.

- Long-Read Sequencing (LRS): Technologies such as PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) generate reads that are 10 kb to over 100 kb in length. These long reads are essential for spanning highly repetitive regions and large structural variants, thereby enabling more complete and accurate genome assemblies [19] [4]. Hi-C data, which captures chromatin conformation, is often used to scaffold contigs into chromosome-length assemblies [1].

- Assembly and Phasing: De novo assembly pipelines (e.g., Verkko, 3D-DNA) are employed to reconstruct genomes from long reads. Phasing information to resolve both haplotypes is achieved using methods such as Strand-seq, trio-based approaches, or Hi-C data [4]. The resulting chromosome-level assemblies are validated against available physical genome maps and assessed for completeness using metrics like BUSCO scores [1].

Detection of Structural Variants and Synteny Blocks

Once assemblies are generated, comparative genomics methods are applied.

- Structural Variant Calling: A combination of SV detection algorithms (e.g., cuteSV, Sniffles, pbsv for long-read data) is used to identify deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations. To ensure high-confidence call sets, a common practice is to consider SVs identified by multiple algorithms [19].

- Synteny Block Identification: Genomes of different species are aligned using whole-genome aligners. Blocks of conserved synteny are defined as homologous genomic regions where the gene order is conserved between species. Synteny breakpoints mark the boundaries between these blocks and are often associated with chromosomal rearrangements [1]. This analysis can reveal evolutionary breakpoint regions and the stability of different chromosomal arms over time.

Table 1: Key Experimental Methodologies for Mosquito Genomics

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Outcome Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi / ONT Sequencing | Generate long, accurate reads for assembly | Read length N50, base-level accuracy (Quality Value) |

| Hi-C Sequencing | Scaffold contigs into chromosomes; study 3D genome | Percentage of assembly anchored to chromosomes; N50 |

| Strand-seq | Phasing of haplotypes | Phasing accuracy and contiguity |

| Whole-Genome Alignment | Identify syntenic regions and breakpoints | Number and length of synteny blocks; rearrangement types |

| Multiple SV Caller Integration | Generate high-confidence SV sets | Recall (sensitivity) and precision of SV detection |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from sample preparation to evolutionary inference, integrating the methodologies described above.

Comparative Analysis of Mosquito Genomes

Applying these methodologies to multiple mosquito species has yielded quantitative insights into the dynamics of genome evolution.

Synteny Block Conservation and Evolutionary Distance

An analysis of five Anopheles species—An. coluzzii, An. merus, An. stephensi, An. atroparvus, and An. albimanus—which represent divergence times up to 100 million years, demonstrates a clear relationship between evolutionary time and genomic architecture [1].

- Synteny Block Number and Length: The number of synteny blocks increases with evolutionary distance, while their average length decreases. For example, closely related species like An. coluzzii and An. merus (diverged ~0.5 MYA) have fewer, longer synteny blocks. In contrast, more distantly related species, such as the comparison between An. coluzzii and An. albimanus, exhibit a higher number of shorter blocks due to an accumulation of rearrangements over time [1].

- Chromosomal Differences: The X chromosome consistently shows smaller synteny blocks and a higher rate of gene shuffling compared to autosomes across all studied species, indicating it is a hotspot for chromosomal rearrangements [1] [15].

Table 2: Synteny Block Dynamics Across Anopheles Phylogeny

| Species Comparison | Evolutionary Distance (Million Years) | Trend in Synteny Block Number | Trend in Synteny Block Length | Observations on X Chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. coluzzii vs An. merus | ~0.5 | Lower | Longer | Elevated shuffling relative to autosomes |

| An. coluzzii vs An. stephensi | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Smaller synteny blocks than autosomes |

| An. coluzzii vs An. albimanus | ~100 | Higher | Shorter | Highest rearrangement rate; smallest blocks |

Macroevolutionary Impact of Chromosomal Rearrangements

At the macroevolutionary scale (between species and above), chromosomal rearrangements, particularly whole-arm translocations and inversions, have shaped the distinct genomic landscapes of mosquito lineages.

- Subfamily Differences: A comparison between Anophelinae and Culicinae subfamilies reveals dramatic differences. Culicinae genomes can be up to five times larger, primarily due to the expansion of transposable elements. Furthermore, the sex-determination systems differ, with Anophelinae having heteromorphic X and Y chromosomes, while in Culicini and Aedini tribes, the sex-determining locus is located on an autosome [15].

- Phylogenomics and Migration: Phylogenomic analysis of the Holarctic Maculipennis Group (e.g., An. freeborni, An. quadrimaculatus, An. atroparvus, An. messeae) using 1271 orthologous genes supports a migration event from North America to Eurasia via the Bering Land Bridge approximately 20–25 MYA. This was followed by adaptive radiation, giving rise to the Palearctic species [20]. These studies rely on accurately identified orthologs, for which synteny is a reliable method [21].

Microevolutionary Impact of Chromosomal Inversions

At the microevolutionary scale (within species), polymorphic inversions are a major driver of local adaptation.

- Adaptation to Environmental Stress: Autosomal inversions maintain sets of co-adapted alleles as "supergenes," allowing mosquito populations to rapidly adapt to environmental pressures, including insecticides [15] [16].

- Detection via Hi-C: Hi-C contact maps can identify polymorphic inversions in population samples by their characteristic "butterfly" pattern. For instance, a ~16 Mb polymorphic inversion on the 2R arm of An. stephensi (inversion 2Rb) was detected this way, showing both standard and inverted arrangements in the population [1].

Cut-edge research in this field relies on a suite of biological materials, data resources, and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mosquito Genomics

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | VectorBase, NCBI Genome | Baseline for variant calling, comparative genomics, and synteny analysis. |

| Biological Samples | Cell lines (e.g., lymphoblastoid), live specimens from populations [4] | Source of genomic DNA for sequencing and functional validation studies. |

| Variant Databases | dbSNP, dbVar, DGV, gnomAD-SV [17] [22] | Catalog known polymorphisms and SVs; filter benign variants in disease studies. |

| Clinical/Evolutionary Databases | DECIPHER, ClinVar, HGSVC [4] [17] | Correlate SVs with phenotypic outcomes and evolutionary patterns. |

| Specialized Software | OrthoFinder (orthology), Minimap2 (alignment), ASTRAL (species tree) [21] | Identify orthologs, align sequences, and reconstruct phylogenetic relationships. |

The comparative analysis of synteny blocks and chromosomal rearrangements across mosquito phylogeny reveals a dynamic genomic landscape shaped by evolutionary forces over millions of years. Key findings indicate that synteny is largely conserved within blocks over long evolutionary periods, while rearrangement breakpoints are non-randomly distributed, with the X chromosome being a rearrangement hotspot [1] [15]. These rearrangements have profound implications, from facilitating adaptive radiation following continental migration [20] to enabling rapid microevolutionary adaptation to vector control measures [15]. The continued refinement of sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools will further enhance our resolution of structural variation, deepening our understanding of mosquito evolution and empowering more effective vector management strategies.

The study of genomic structural variants (SVs) is crucial for understanding the evolutionary dynamics of both disease vectors and plant genomes. In the context of mosquito research, SVs—including duplications and deletions—have been identified as key drivers of adaptive success in major malaria vectors like Anopheles stephensi, facilitating insecticide resistance and larval tolerance to brackish water [12] [23]. Similarly, in the model legume Medicago truncatula, a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 4 and 8 in the reference accession A17 provides a powerful system for investigating the mechanisms and consequences of balanced chromosomal rearrangements [24] [25]. This case study examines the M. truncatula A17 translocation as a model for SV analysis, with methodologies and insights directly relevant to comparative genomic studies in mosquito populations.

The A17 Reciprocal Translocation: Characterization and Detection

Discovery and Cytogenetic Evidence

The reciprocal translocation in M. truncatula accession A17 was initially identified through observations of semisterility in intraspecific hybrids. Genetic mapping revealed unexpected linkage between markers on chromosomes 4 and 8, indicating an apparent genetic connection between the lower arms of these chromosomes [24]. This rearrangement represents a large-scale balanced translocation involving approximately 30 Mb of exchanged sequence [25].

Pollen viability tests using Alexander's stain provided key biological evidence, with F1 hybrids from crosses involving A17 consistently showing 50% or less pollen viability—a classic indicator of heterozygous translocation [24]. This reduction occurs because translocation heterozygotes produce unbalanced gametes due to aberrant meiosis segregation patterns.

Genomic Confirmation and Comparative Assembly

Advanced genomic technologies have precisely characterized this translocation. Hi-C sequencing of the R108 accession enabled chromosome-scale assembly and clear visualization of the translocation when compared to A17 [25]. The integration of optical mapping and genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) maps further validated the chromosomal rearrangement [26]. These approaches revealed that the A17 genome contains a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 4 and 8, while other accessions like R108 maintain the ancestral chromosomal configuration [25].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Medicago truncatula Accessions

| Accession | Chromosomal Configuration | Transformation Efficiency | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jemalong A17 | Reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 4 and 8 [24] [25] | Low [25] | Reference genome sequence [25] |

| R108 | Standard chromosomal arrangement (no 4/8 translocation) [25] | High [25] | Preferred for functional genomics and Tnt1 mutant studies [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Translocation Analysis

Genetic Mapping and Phenotypic Screening

The initial detection of the A17 translocation followed a well-established protocol:

- Crossing Scheme: Generate intraspecific hybrids between A17 and other accessions representing diverse genetic backgrounds [24].

- Pollen Viability Assessment: Collect flowers from F1 plants and stain pollen with Alexander's stain, which differentially stains viable (red) versus aborted (green) pollen grains [24].

- Microscopic Evaluation: Examine stained pollen under light microscopy and calculate the percentage of viable pollen. Semisterility (approximately 50% viability) suggests heterozygous translocation [24].

- Genetic Linkage Analysis: Construct genetic maps using molecular markers and identify unexpected linkages between non-homologous chromosomes [24].

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Structural Variant Detection

Modern approaches utilize sequencing-based methods for translocation detection:

- Library Preparation: Generate paired-end sequencing libraries with insert sizes appropriate for detecting chromosomal rearrangements (typically 300-500bp) [27].

- Sequencing: Sequence to a minimum of 20x coverage using short-read platforms (Illumina) for reliable SV detection [27].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to a reference genome

- Identify discordant read pairs (mates mapping to different chromosomes or unexpected orientations)

- Detect split reads (single reads spanning breakpoints)

- Use SV calling tools like DELLY to identify translocation breakpoints [27]

Validation: Confirm predicted breakpoints using PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing across junction regions [27].

Hi-C for Chromosome-Scale Assembly

For comprehensive translocation characterization:

- Cross-linking: Fix chromatin with formaldehyde in intact nuclei [25].

- Digestion and Marking: Digest DNA with restriction enzymes and label cleavage ends [25].

- Proximity Ligation: Ligate cross-linked DNA fragments to capture three-dimensional genomic contacts [25].

- Sequence and Analyze: Generate high-throughput sequencing data and construct contact probability maps [25].

- Scaffolding: Use contact maps to anchor, order, and orient contigs into chromosome-scale assemblies, revealing large-scale rearrangements like the A17 translocation [25].

Comparative Genomic Analysis: A17 versus R108

The comparison between A17 and R108 genomes provides unique insights into translocation effects:

Table 2: Genomic Assembly Statistics for M. truncatula Accessions

| Assembly Metric | A17 (Mt5.0) | R108 (v1.0) | R108 (MedtrR108_hic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Assembly Size | ~400 Mb [25] | 402 Mb [25] | ~400 Mb [25] |

| Chromosome-length Scaffolds | 8 [25] | 0 (909 total scaffolds) [25] | 8 [25] |

| Anchored Sequence | Not specified | Not specified | 97.62% [25] |

| Protein-coding Genes | 44,623 [25] | 55,706 [25] | 39,027 [25] |

| Complete BUSCOs | Comparable to R108_hic [25] | 91.94% [25] | 96.73% [25] |

The reciprocal translocation in A17 has significant implications for genetic studies:

- Aberrant Recombination: Genetic crosses between A17 and other accessions show distorted recombination patterns [25]

- Synteny Disruption: Complicates comparative genomics with other legume species [24] [25]

- Transformation Efficiency: A17 has low transformation efficiency compared to R108, limiting its utility for functional genomics [25]

Research Toolkit for Translocation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Example in Current Context |

|---|---|---|

| Alexander's Stain | Differential staining of viable vs. non-viable pollen [24] | Detection of semisterility in translocation heterozygotes [24] |

| Hi-C Technology | Capturing chromatin conformation for chromosome-scale scaffolding [25] | Anchoring R108 genome assembly and visualizing A17 translocation [25] |

| Tnt1 Insertion Lines | Gene disruption and functional genomics [25] | R108 mutant population for legume functional analysis [25] |

| DELLY Software | Structural variant calling from sequencing data [27] | Detection of balanced reciprocal translocations in sequenced genomes [27] |

| Optical Mapping | Physical mapping of large DNA molecules [26] | Validation and scaffolding of genome assemblies [26] |

| GBS (Genotyping-by-Sequencing) | High-density genetic marker discovery [26] | Genetic map construction for genome anchoring [26] |

Implications for Mosquito Genomic Research

The methodologies and insights from M. truncatula translocation studies directly inform mosquito genomic research:

SV Detection Protocols: The sequencing and bioinformatic approaches used to characterize the A17 translocation are equally applicable to identifying SVs in mosquito genomes, including the duplications linked to insecticide resistance in Anopheles stephensi [12] [23].

Adaptive Evolution: Similar to how the A17 translocation affects fertility and genome organization, SVs in mosquito populations show signatures of positive selection and contribute to rapid adaptation to environmental challenges [12].

Comparative Genomics: The synteny disruption observed between A17 and R108 parallels findings in mosquito studies, where SVs create population-specific genomic architectures that influence invasive potential and insecticide resistance [12] [23].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Reciprocal Translocation Analysis. This diagram illustrates the complementary approaches for identifying chromosomal translocations, integrating both classical genetic and modern genomic methods.

Diagram 2: Mechanism and Consequences of Reciprocal Translocation. This diagram illustrates the chromosomal exchange in A17 and its meiotic implications, explaining the observed semisterility.

The reciprocal translocation in M. truncatula A17 serves as an exemplary model for investigating balanced chromosomal rearrangements, with direct methodological and conceptual relevance to SV research in mosquito genomes. The integrated approaches developed for its characterization—combining classical genetics, modern sequencing technologies, and bioinformatic analyses—provide a powerful framework for identifying and understanding the functional significance of SVs across diverse species. As demonstrated in both plant and mosquito systems, structural variants represent crucial mechanisms of rapid adaptation, with profound implications for agricultural productivity and disease vector control.

Advanced Technologies for SV Detection: From Hi-C Scaffolding to CRISPR Screening Platforms

Hi-C Data for Chromosome-Scale Genome Assembly in Anopheles

The study of mosquito genomes is critical for understanding their role as disease vectors and for developing targeted control strategies. For Anopheles mosquitoes, the primary vectors of malaria, chromosome-scale genome assemblies are indispensable for researching fundamental biological processes such as insecticide resistance, gene drive systems, and chromosomal evolution [28]. Hi-C sequencing, a genome-wide chromosome conformation capture technique, has revolutionized this field by enabling researchers to transform fragmented draft assemblies into complete, chromosome-length sequences. This guide provides a comparative analysis of Hi-C methodologies and their application in Anopheles genomic research, offering experimental data and protocols to inform researchers' experimental design.

Experimental Protocols for Hi-C in Anopheles

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

Successful Hi-C scaffolding begins with proper sample preparation and library construction. The process starts with chromatin fixation using formaldehyde to preserve the 3D architecture of the genome inside the nucleus [29]. The fixed chromatin is then digested with restriction enzymes—commonly targeting GATC and GANTC sites—followed by fill-in of the 5'-overhangs with biotinylated nucleotides to label the digested ends [30]. Spatially proximal ends are then ligated before the DNA is purified, sheared, and prepared for paired-end sequencing on Illumina platforms [30].

Multiple commercial kits are available, each with specific advantages. The traditional protocol by Rao et al. uses MboI (cuts at "GATC") with a 2-hour to overnight digestion, while iconHi-C uses HindIII (cuts at "AAGCTT") or DpnII (cuts at "GATC") with overnight digestion [29]. Commercial kits like the Arima-HiC Kit employ optimized enzyme cocktails for more efficient digestion (30-60 minutes) [29]. The Omni-C kit differs by using a sequence-independent endonuclease and dual crosslinking with DSG and formaldehyde to capture more proximal contacts [29].

For Anopheles species, researchers have successfully employed these methods across various life stages. One comprehensive study utilized 15-18 hour embryos from five Anopheles species, while another generated a high-quality assembly using a pool of adult mosquitoes from the FUMOZ colony [1] [31]. The library construction typically yields 60-194 million unique alignable reads per species, providing sufficient coverage for chromosome-scale scaffolding [1].

Genome Assembly and Scaffolding Workflow

The computational process of transforming sequencing data into chromosome-scale assemblies involves multiple steps of increasing scale and complexity, as illustrated below:

The process begins with generating long-read sequencing data (PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) to create a primary contig assembly [31] [28]. Hi-C reads are then aligned to these contigs, and pairs mapping to different contigs are used to construct a scaffold graph [30]. Contigs are clustered, ordered, and oriented into chromosome-scale scaffolds using the contact frequency information [32]. The final assembly undergoes rigorous evaluation using metrics such as BUSCO completeness scores, contact map visualization, and comparison to physical maps [1] [31].

Advanced methods like SALSA2 incorporate the assembly graph to correct orientation errors, particularly valuable when working with shorter contigs where biological factors like topologically associated domains (TADs) can confound analysis [30]. This approach uses an iterative scaffolding method with a novel stopping condition that naturally terminates when accurate Hi-C links are exhausted, without requiring a priori knowledge of chromosome number [30].

Performance Comparison of Hi-C Scaffolding Approaches

Assembly Metrics Across Anopheles Species

Hi-C scaffolding has been successfully applied to multiple Anopheles species, significantly improving assembly continuity and completeness. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from published studies:

Table 1: Performance of Hi-C scaffolding across Anopheles species

| Species | Contig N50 (pre-Hi-C) | Scaffold N50 (post-Hi-C) | BUSCO Completeness | Chromosomes Assembled | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An. funestus (AfunF3) | 631.7 kb | 93.8 Mb | 99.2% | 3 | [31] |

| An. stephensi (UCISS2018) | 38.0 Mb | 88.7 Mb | 99.2% | 3 (plus Y contigs) | [28] |

| An. coluzzii (AcolN2) | ~3.5 Mb (scaffold) | Chromosome-level | N/A | 5 arms | [1] |

| An. albimanus (AalbS4) | Scaffold-level | Chromosome-level | N/A | 5 arms | [1] |

The data demonstrates dramatic improvements in assembly continuity, with scaffold N50 values increasing to megabase scales. The An. stephensi assembly represents particular success, achieving a contig N50 of 38 Mb and scaffold N50 of 88.7 Mb, making it comparable to the Drosophila melanogaster reference genome considered a gold standard for metazoan genomes [28]. This 1044-fold and 56-fold increase in contig N50 and scaffold N50, respectively, over the previous draft assembly enabled the discovery of previously hidden genomic features, including 29 new members of insecticide resistance genes and 2.4 Mb of Y chromosome sequence [28].

Comparison of Computational Methods

Various computational tools are available for Hi-C scaffolding, each with different strengths and requirements:

Table 2: Comparison of Hi-C scaffolding algorithms

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SALSA2 | Uses assembly graph to guide scaffolding; iterative approach with automatic stopping condition | Minimizes orientation errors; doesn't require chromosome number estimate | Performance depends on Hi-C data coverage | [30] |

| 3D-DNA | Corrects assembly errors first; iteratively orients and orders contigs into megascaffold | Demonstrated on Aedes aegypti; breaks megascaffold into chromosomes | Sensitive to input assembly contiguity | [30] |

| LACHESIS | Clusters contigs into specified chromosome groups; orients and orders independently | Early established method | Requires chromosome number estimate; inherits assembly errors | [30] |

Beyond scaffolding algorithms, specialized tools have been developed for identifying chromatin loops from Hi-C data. A comprehensive comparison of 11 loop-calling methods revealed significant differences in performance [33]. SIP (Significant Interaction Peak caller) employs image processing techniques including Gaussian blur, contrast enhancement, and regional maxima detection to identify loops, demonstrating superior efficiency using only 1 GB of memory and completing analysis in 46 minutes for a full human dataset [34]. In contrast, methods like HiCCUPS, HOMER, and cLoops required 62-103 GB of memory for the same task [34].

When evaluating scaffolding results, researchers should consider multiple metrics. The BUSCO score assesses gene space completeness by quantifying the presence of universal single-copy orthologs [31] [28]. The contact map visualization should show clear separation between chromosomes with strong diagonal signals and minimal off-diagonal artifacts [1] [28]. Additionally, comparison to known physical maps or synteny blocks with related species provides validation of assembly accuracy [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and resources for Hi-C in Anopheles

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Function in Protocol | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Agent | Formaldehyde (1-2%) or DSG + Formaldehyde | Preserves 3D chromatin structure by crosslinking proteins and DNA | Sigma-Aldrich, Commercial kits [29] |

| Restriction Enzymes | 6-cutter (e.g., HindIII) or 4-cutter (e.g., DpnII) | Digests chromatin at specific sequences to enable proximity ligation | NEB, Arima Genomics [30] [29] |

| Biotinylated Nucleotides | Biotin-14-dCTP or similar | Labels digested DNA ends for enrichment of ligation products | Thermo Fisher, Commercial kits [30] |

| Chromatin Capture Beads | Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads | Enriches for biotinylated ligation products | Phase Genomics, Dovetail Genomics [29] |

| Assembly Algorithms | SALSA2, 3D-DNA, LACHESIS | Computational scaffolding using Hi-C contact frequencies | GitHub repositories [30] |

| Validation Tools | BUSCO, Merqury, Hi-C contact maps | Assess assembly completeness, accuracy, and scaffolding quality | Open source bioinformatics tools [31] [28] |

Technical Considerations for Optimal Results

Experimental Design Factors

Successful Hi-C scaffolding depends on several technical factors beginning with sample quality. For Anopheles species, the tissue type selected can impact results, with recommendations favoring tissues with low endogenous nuclease activity such as embryos or whole adults [1] [29]. The input assembly quality significantly affects scaffolding outcomes, with longer contigs producing more reliable scaffolds [30]. The sequencing depth should be sufficient, with recommendations of approximately 100 million read pairs per gigabase of genome, though Anopheles studies have successfully used 60-194 million unique alignable reads [1] [29].

The restriction enzyme choice affects the resolution of the contact map. Six-cutters (like HindIII) provide broader genomic coverage but lower resolution, while four-cutters (like DpnII) generate higher resolution contact maps but may be affected by DNA methylation [29]. For Anopheles, studies have successfully used enzymes targeting GATC and GANTC sites [30].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common challenges arise in Hi-C scaffolding. Inversion errors frequently occur when input contigs are short, as biological features like TADs can create misleading contact patterns [30]. The integration of assembly graphs in tools like SALSA2 helps correct these errors by using sequence overlap information [30]. Polymorphic inversions natural to Anopheles populations can create "butterfly" contact patterns on Hi-C maps, which should be recognized as biological features rather than assembly errors [1].

Haplotype variation presents another challenge, particularly when pooling multiple individuals to obtain sufficient high-molecular-weight DNA for library preparation. In the An. funestus AfunF3 assembly, initial contigs totaled 446 Mbp due to haplotype separation, which was reduced to 211 Mbp after deduplication, much closer to the expected 250 Mbp haploid genome size [31]. Methods for identifying and removing these alternative alleles are crucial for obtaining accurate primary assemblies.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between experimental steps and the corresponding quality control checkpoints:

Hi-C data has revolutionized chromosome-scale genome assembly for Anopheles mosquitoes, enabling reference-grade resources that support advanced research into vector biology and control. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that while multiple experimental and computational approaches exist, they share common principles of proximity ligation and contact frequency analysis. Successful implementation requires careful attention to sample preparation, appropriate choice of restriction enzymes, sufficient sequencing depth, and selection of computational methods matched to assembly goals. As evidenced by the dramatically improved assemblies of An. stephensi, An. funestus, and other malaria vectors, these technologies continue to reveal previously hidden genomic features—from insecticide resistance genes to Y chromosome sequences—that advance our understanding of mosquito biology and create new opportunities for intervention strategies.

Long-read sequencing technologies have revolutionized genomics by enabling the analysis of DNA fragments thousands to millions of bases in length, providing unprecedented ability to resolve complex genomic regions that were previously inaccessible with short-read technologies [35] [36]. In the context of mosquito genome research, these technologies have become indispensable tools for assembling high-quality reference genomes, identifying structural variants, and understanding genome evolution in disease vectors [37]. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) have emerged as the two leading platforms in this space, each employing distinct biochemical principles to generate long reads [38]. The application of these technologies has been particularly transformative for studying mosquitoes with large, complex genomes rich in repetitive elements, such as Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus [37] [39]. This comparative analysis examines the technical capabilities, performance characteristics, and practical applications of both platforms within mosquito genomic research, providing researchers with objective data to inform their technology selection.

PacBio Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing

PacBio's SMRT sequencing technology utilizes zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) - nanoscale holes that contain a single DNA polymerase molecule attached to the bottom [38]. As the polymerase synthesizes a complementary DNA strand, fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are incorporated, with each nucleotide type emitting a distinct light signal as it enters the detection zone [35] [38]. The key advantage of this approach is the ability to generate highly accurate consensus sequences through circular consensus sequencing (CCS), where the same molecule is sequenced repeatedly to produce HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads with accuracy exceeding 99.9% [35] [40]. This technology also enables direct detection of DNA modifications such as 5mC methylation without bisulfite treatment, as the polymerase kinetics are sensitive to epigenetic modifications [35]. Read lengths typically range from 10-25 kb for HiFi reads, with newer systems capable of generating reads over 20 kb, sufficient to span many repetitive elements and complex genomic regions found in mosquito genomes [35] [41].

Oxford Nanopore Electrical Signal Sensing

Oxford Nanopore technology employs a fundamentally different approach based on the modulation of electrical currents. The system measures changes in ionic current as single strands of DNA or RNA pass through protein nanopores embedded in a synthetic membrane [35] [38]. Each nucleotide composition causes a characteristic disruption in current flow, allowing base identification in real time [35]. A notable advantage of this platform is its capacity to generate ultra-long reads, frequently exceeding 100 kb and sometimes reaching megabase lengths, which can span massive repetitive blocks and complex structural variants in a single read [38] [40]. The technology can sequence native DNA and RNA without amplification, preserving base modification information that can be detected through analysis of current signatures [35] [42]. Recent improvements in chemistry and basecalling algorithms have significantly enhanced raw read accuracy, which now exceeds 99% with Q20+ chemistry and updated models like Dorado [40].

Performance Comparison and Technical Specifications

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of PacBio and Oxford Nanopore technologies

| Feature | PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Fluorescently labeled dNTPs + ZMW detection [38] | Nanopore current sensing [38] |

| Typical Read Length | 10-25 kb (HiFi reads) [40] [41] | 20 kb to >1 Mb [40] [36] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | ~85% (initial) [38] | ~93.8% (R10 chip) [38] |

| Consensus Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30+) [35] [40] | ~99.996% (consensus at 50X depth) [38] |

| Typical Yield | 60-120 Gb per SMRT Cell [35] | 50-100 Gb (PromethION flow cell) [35] |

| Run Time | 24 hours [35] | Up to 72 hours [35] |

| Structural Variant Detection | SNVs, Indels, SVs [35] | SNVs, SVs (limited indel calling) [35] |

| Epigenetic Detection | 5mC, 6mA (simultaneous with sequencing) [35] | 5mC, 5hmC, 6mA (requires additional analysis) [35] |

| Portability | Benchtop systems only [38] | Portable options (MinION, Flongle) [35] [38] |

| Data Output Size | 30-60 GB (BAM format) [35] | ~1300 GB (FAST5/POD5 format) [35] |

Table 2: Application-based comparison for mosquito genomics research

| Research Application | PacBio Strengths | Oxford Nanopore Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Genome Assembly | High accuracy for reference-grade assemblies [39] | Ultra-long reads for resolving complex repeats [37] |

| Structural Variant Detection | Superior indel detection [35] [41] | Enhanced large SV discovery [40] |

| Epigenetic Modification Analysis | Direct 5mC detection with high accuracy [35] | Broad modification detection (5mC, 5hmC) [35] |

| Field Sequencing | Not applicable | Portable sequencing with MinION [38] [37] |

| Transcriptome Analysis | Full-length isoform sequencing with high accuracy [43] | Direct RNA sequencing without cDNA conversion [38] |

| Rapid Pathogen Surveillance | Limited by run time | Real-time data streaming for rapid analysis [35] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Genome Assembly Workflow for Mosquito Genomes

The application of long-read technologies to mosquito genome assembly follows established computational workflows with platform-specific adaptations. For PacBio-based assemblies, the high accuracy of HiFi reads enables efficient variant detection and consensus formation, with platforms like the Revio system generating sufficient data for large mosquito genomes (e.g., ~1.3 Gb for Aedes aegypti) in a single run [35] [39]. ONT sequencing, particularly with ultra-long read protocols, facilitates the resolution of complex repetitive regions, as demonstrated in the Culex quinquefasciatus genome project where ONT reads were combined with Hi-C scaffolding to achieve chromosome-scale assembly [37]. Both technologies typically require complementary approaches such as optical mapping (Bionano) or chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) to scaffold contigs into chromosome-scale assemblies [37].

Diagram Title: Mosquito Genome Assembly Workflow

Structural Variant Detection in Mosquito Genomes

The detection of structural variants (SVs) - including insertions, deletions, inversions, duplications, and complex rearrangements - represents a major application of long-read sequencing in mosquito genomics [40]. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that PacBio HiFi sequencing consistently delivers high performance in SV detection, with F1 scores exceeding 95% in the PrecisionFDA Truth Challenge V2 [40]. This high accuracy stems from the exceptional base-level quality (Q30-Q40) of HiFi reads, which minimizes false positives and enables confident variant calling in both unique and repetitive genomic regions [40]. ONT sequencing, while historically limited by higher error rates, has shown substantial improvements with Q20+ chemistry and updated basecalling models, currently achieving SV calling F1 scores of 85-90% [40]. The platform's capacity for ultra-long reads provides distinct advantages for detecting large or complex rearrangements that may be incompletely resolved with shorter reads [40].

Case Study: Culex quinquefasciatus Genome Assembly

Experimental Protocol and Reagent Solutions

A recent study demonstrating the power of long-read sequencing for mosquito genomics presented an improved chromosome-scale genome assembly for the West Nile vector Culex quinquefasciatus [37]. The research employed a combination of ONT sequencing, Hi-C scaffolding, Bionano optical mapping, and cytogenetic mapping to overcome challenges posed by the genome's size (~579 Mb) and high heterozygosity [37]. The experimental design utilized a trio-binning approach, sequencing F0 parents with Illumina technology and F1 male siblings with ONT to separate paternal and maternal haplotypes [37]. This strategy effectively leveraged the platform's ultra-long read capability while addressing assembly complications arising from sequence polymorphism.

Table 3: Research reagents and computational tools for mosquito genome assembly

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in Cx. quinquefasciatus Study |

|---|---|---|

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | Library preparation for nanopore sequencing | Generation of ~89 Gb long-read data from F1 mosquitoes [37] |

| Bionano Saphyr System | Optical genome mapping | Scaffolding assistance for chromosome-scale assembly [37] |

| Hi-C Library Kit | Chromatin conformation capture | Determining spatial proximity of genomic regions [37] |

| Canu Assembler | Long-read de novo assembly | Initial genome assembly from ONT reads [37] |

| 3D-DNA | Hi-C scaffolding pipeline | Chromosome-scale scaffolding with manual correction [37] |

| Pilon | Genome polishing tool | Polish assembly using Illumina short-read data [37] |

Key Findings and Biological Insights