Combating Compound Interference in Phenotypic High Content Screening: Strategies for AI-Driven, Reproducible Drug Discovery

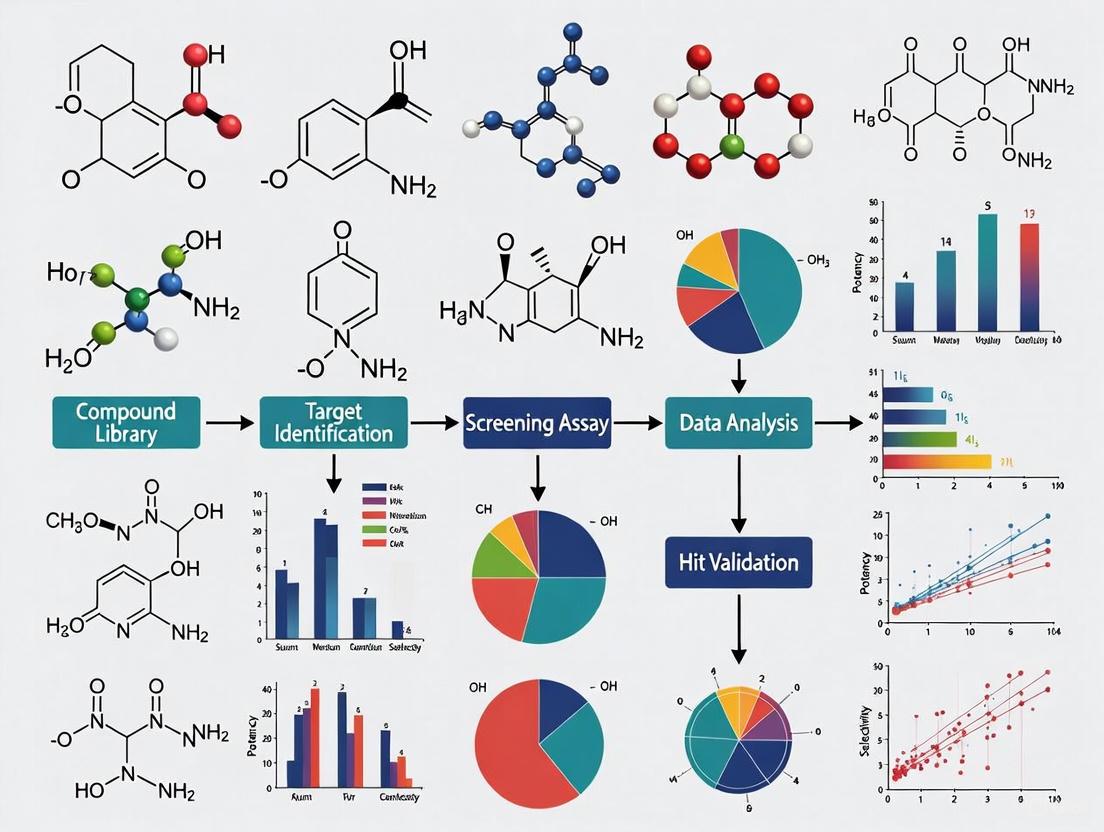

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of compound interference in phenotypic High Content Screening (HCS).

Combating Compound Interference in Phenotypic High Content Screening: Strategies for AI-Driven, Reproducible Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of compound interference in phenotypic High Content Screening (HCS). It covers foundational concepts of how compounds can disrupt assays, explores advanced methodological and AI-powered applications to mitigate interference, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and discusses validation frameworks for ensuring data quality and reproducibility. With the global HCS market projected for significant growth, driven by advances in 3D models and AI, mastering these aspects is essential for accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics.

Understanding Compound Interference: The Silent Saboteur in HCS Data Quality

In phenotypic high-content screening (HCS), the term "compound interference" refers to a range of artifactual effects caused by test compounds that can lead to false positives or false negatives, ultimately compromising data integrity and research validity. Unlike simple toxicity, which manifests as clear cellular damage or death, compound interference encompasses more subtle, technology-specific interactions that can mimic or obscure genuine biological signals [1]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in this field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the main types of compound interference in HCS, and how can I identify them?

Compound interference in HCS generally falls into several key categories, each with distinct characteristics and identification strategies.

Table 1: Common Types of Compound Interference and Their Identification

| Interference Type | Description | Common Indicators in HCS |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Interference | Compounds interfere with the detection system itself, e.g., through autofluorescence or quenching of fluorescent signals. [2] [1] | Unexpected fluorescence in control channels; signal loss inconsistent with biology; concentration-dependent signal quenching. |

| Chemical Reactivity | Compounds exhibit promiscuous, non-specific reactivity with biomolecules, such as covalent binding to thiol groups. [3] | Irreversible activity; activity across diverse, unrelated assay targets; presence of known toxicophore substructures. |

| Colloidal Aggregation | Compounds form sub-micron aggregates that non-specifically inhibit proteins by sequestering or adsorbing them. [3] | Sharp concentration-response curves; loss of activity upon addition of mild detergents like Triton X-100; non-competitive inhibition patterns. |

| Assay Technology Interference | Compounds interfere with the specific chemistry of the assay technology, e.g., by redox cycling or singlet oxygen quenching. [1] [3] | Signal generation or quenching in the absence of biological components; interference detected in specific counter-screens. |

| Cellular Toxicity | Off-target cytotoxic effects that are not related to the intended target but confound the phenotypic readout. [4] [3] | Decreased cell count; changes in gross morphology (e.g., membrane blebbing); induction of stress responses. |

FAQ 2: I have identified potential hit compounds in my HCS. What experimental protocols can I use to rule out compound interference?

A robust confirmation protocol is essential to de-risk your hit compounds. The following workflow outlines a multi-step approach to rule out common interference mechanisms.

Experimental Protocol for Hit Confirmation:

Dose-Response Analysis:

- Objective: To determine if the compound's activity is concentration-dependent and to calculate a half-maximal inhibitory value (IC50). A shallow or irregular curve can be indicative of interference.

- Method: Re-test the hit compound in a dilution series (e.g., from 10 µM to 1 nM) in the original HCS assay. Run the assay in replicates (at least n=3) to ensure reproducibility. [5]

- Acceptance Criteria: A clean, sigmoidal dose-response curve with a well-defined plateau is expected for a specific bioactive compound.

Confirmatory Orthogonal Assay:

- Objective: To verify the biological activity using a different assay technology that is not susceptible to the same interference mechanisms.

- Method: Develop a secondary assay that measures the same biological pathway but uses a different readout. For example, if the primary HCS uses an imaging readout, a secondary assay could be a biochemical assay (e.g., TR-FRET, AlphaScreen) or a gene-expression assay (L1000). [1] [6]

- Acceptance Criteria: The compound should show consistent activity (a similar rank order of potency) in the orthogonal assay.

Counter-Screens for Assay Artifacts:

- Objective: To directly test for common interference mechanisms.

- Methods:

- For Fluorescence Interference: Include the compound in the assay in the absence of the biological system (e.g., in buffer with fluorophores only) to detect autofluorescence or quenching. [2] [1]

- For Aggregation: Add non-ionic detergents (e.g., 0.01% Triton X-100) to the assay buffer. True bioactive compounds will retain activity, while aggregators often lose it. [3]

- For Redox Activity: Use specific assays to detect redox cycling or generation of reactive oxygen species. [3]

- Acceptance Criteria: The compound should show no significant activity in these interference counter-screens.

Chemical Structure Analysis:

- Objective: To identify chemical substructures (toxicophores) known to be associated with promiscuous activity or assay interference.

- Method: Virtually screen the compound's structure against published libraries of nuisance compounds, such as Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) and other toxicophore lists, using cheminformatics tools like RDKit. [3]

- Interpretation: A flag for a nuisance substructure is not an automatic disqualification but indicates a need for more rigorous experimental validation.

FAQ 3: How can I leverage high-content data itself to identify and filter out interfering compounds?

High-content screening generates multiparametric data, which is a powerful asset for identifying interference. Unlike single-parameter assays, HCS allows you to detect unintended "off-target" phenotypes.

- Strategy: Use multivariate statistical and machine learning approaches to classify compound profiles.

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: Ensure your image analysis extracts multiple features per cell (e.g., intensity, texture, morphology, and spatial relationships for each channel).

- Control Signatures: Establish phenotypic signatures for known biological activities (e.g., a positive control for your target) and for common interference patterns (e.g., a cytotoxic profile from a known toxic compound).

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Use unsupervised learning methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize all tested compounds in a 2D or 3D space. Compounds with similar phenotypic profiles will cluster together. [7] This allows you to see if your hits cluster with true actives or with known interference classes (e.g., cytotoxic compounds, fluorescent compounds). [7]

- Supervised Modeling: For more robust classification, build a model using methods like Random Forests or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). Train the model on a manually curated subset of data where compounds have been verified as true actives or false positives. The model can then classify new hits based on their multi-parametric profile, significantly improving the accuracy of hit selection over simple, single-parameter thresholds. [7]

FAQ 4: My assay uses homogeneous, "mix-and-read" formats like TR-FRET or AlphaScreen. What specific interferences should I worry about?

Homogeneous proximity assays are particularly susceptible to certain interferences because there are no wash steps to remove the compound before reading. [1]

- Signal Attenuation (Quenching/Inner Filter Effect): The compound absorbs the excitation or emission light, reducing the detectable signal.

- Signal Generation (Autofluorescence): The compound itself fluoresces at wavelengths similar to the assay's reporter, creating a false-positive signal.

- Disruption of Affinity Capture: The compound interferes with the antibody-epitope or tag-ligand interactions (e.g., with glutathione-S-transferase or GST tags) that are central to the assay. [1]

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Run Interference Counter-Screens: As described in FAQ 2, test compounds in the absence of one or more critical biological components.

- Use Tag-Specific Controls: Test if the compound interferes with the binding of the affinity tag itself.

- Consider Technology Switch: If interference is persistent, re-develop the assay in a heterogeneous format (with wash steps) or an orthogonal technology to confirm key findings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and tools used in the development and execution of HCS assays designed to be robust against compound interference.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Managing Compound Interference

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Role in Mitigating Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines (Validated) | Immortalized or primary cells used in the HCS assay. | Using genotypically and phenotypically validated cell lines ensures functional pathways and reduces background variability that can mask interference. [5] |

| STR Profiling | Short Tandem Repeat analysis for cell line authentication. | Prevents misidentification and contamination, a source of irreproducible results that can be mistaken for compound-specific effects. [5] |

| Z'-factor | A statistical parameter (range 0-1) for assessing assay quality and robustness. | An assay with a Z' > 0.4 (preferably >0.6) is sufficiently robust to be less susceptible to minor compound interference effects. [5] |

| PAINS/Toxicophore Filters | Computational filters (e.g., in RDKit) based on structural alerts for nuisance compounds. | Allows for virtual screening of compound libraries prior to testing to flag and deprioritize compounds with high-risk substructures. [3] |

| Counter-Assay Reagents | Reagents for orthogonal assays (e.g., TR-FRET, AlphaScreen components). | Provides a different technological readout to confirm biological activity and rule out technology-specific interference. [1] [6] |

| Triton X-100 | A non-ionic detergent. | Used in experiments to test for colloidal aggregation; its addition often abolishes the activity of aggregating compounds. [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of autofluorescence in high-content screening? Autofluorescence in high-content screening arises from both endogenous and exogenous sources. Key endogenous sources include culture media components like riboflavins, which fluoresce in the ultraviolet through green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant spectral ranges, and intracellular molecules within cells and tissues, such as flavins, flavoproteins, lipofuscin, NADH, and FAD [8]. Extracellular components like collagen and elastin are also common causes [9]. Exogenous sources can include lint, dust, plastic fragments from labware, and microorganisms introduced during sample processing [8].

2. How does compound-mediated interference lead to false results? Test compounds can cause optical interference through autofluorescence or fluorescence quenching, producing artifactual bioactivity readouts that are not related to the intended biological target [8] [2]. These compounds can alter light transmission or reflection, leading to false positives or false negatives that obscure whether a compound truly modulates the desired target or cellular phenotype [8] [10]. In one reported high-content screen, all 1130 initial hits were ultimately determined to be the result of optical interference rather than specific biological activity [2].

3. What is spectral overlap (bleed-through) and how can it be resolved? Spectral overlap, or bleed-through, occurs when the emission spectra of multiple fluorophores in a sample overlap significantly, making it difficult or impossible to distinguish their individual signals using traditional filter sets [11]. This is common when using fluorescent proteins like ECFP, EGFP, and EYFP, which have strongly overlapping emission spectra [11]. Advanced techniques like spectral imaging coupled with linear unmixing can segregate these mixed fluorescent signals by gathering the entire emission spectrum and computationally separating the signals based on their unique "emission fingerprints" [11].

4. What strategies can mitigate autofluorescence in fixed tissue samples? Several chemical treatments can effectively reduce tissue autofluorescence. A 2023 study systematically evaluated multiple methods in adrenal cortex tissue, with the most effective treatments being TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher (reducing autofluorescence by 89–93%) and MaxBlock Autofluorescence Reducing Reagent Kit (reducing autofluorescence by 90–95%) [9]. Other methods include Sudan Black B, copper sulfate, ammonia/ethanol, and trypan blue, though their efficacy varies (12% to 88% reduction) depending on the excitation wavelength and tissue type [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Issues

Problem 1: High Background Flufficiency Compromising Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Potential Cause: Media autofluorescence or endogenous tissue autofluorescence.

Solutions:

- For live-cell imaging: Consider using phenol-red free media or fluorophore-free media, as components like riboflavins can elevate fluorescent backgrounds [8].

- For fixed tissues: Apply autofluorescence quenching reagents. The table below summarizes the efficacy of various treatments based on experimental data [9]:

Table 1: Efficacy of Autofluorescence Quenching Reagents in Fixed Tissue

| Treatment Reagent | Excitation Wavelength | Average Reduction in Autofluorescence | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | 405 nm & 488 nm | 89% - 93% | Preserves specific fluorescence signals and tissue integrity [9]. |

| MaxBlock Autofluorescence Reducing Reagent Kit | 405 nm & 488 nm | 90% - 95% | Effective across entire tissue section; produces homogeneous background [9]. |

| Sudan Black B (SBB) | 405 nm & 488 nm | ~82% - 88% | Reduction may be heterogeneous, depending on local staining intensity [9]. |

| TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit | 405 nm & 488 nm | ~62% - 70% | Less effective than TrueBlack or MaxBlock [9]. |

| Ammonia/Ethanol (NH3) | 405 nm & 488 nm | ~65% - 70% | Does not eliminate autofluorescence completely [9]. |

| Copper(II) Sulfate (CuSO4) | 405 nm & 488 nm | ~52% - 68% | Moderate efficacy [9]. |

| Trypan Blue (TRB) | 405 nm | ~12% | Ineffective at 488 nm excitation; shifts emission to longer wavelengths [9]. |

Problem 2: Unexpected Signal Loss or Gain in Compound-Treated Wells

Potential Cause: Compound-mediated optical interference (autofluorescence or quenching).

Solutions:

- Statistical Flagging: Analyze fluorescence intensity data across the plate. Compounds causing interference often produce outlier values compared to the normal distribution of control wells [8].

- Image Review: Manually review images from outlier wells for signs of compound precipitation, abnormal cell morphology, or uniform fluorescence not associated with cellular structures [8].

- Implement Orthogonal Assays: Confirm hits using a secondary assay with a fundamentally different detection technology (e.g., luminescence instead of fluorescence) that is not susceptible to the same interference mechanisms [8] [10].

- Use Interference Counter-Screens: Employ dedicated assays to profile compound libraries for autofluorescence and luciferase inhibition, enabling the identification and filtering of problematic compounds [10].

Table 2: Profiling Compound Interference in HTS

| Interference Type | Assay Format | Key Findings from HTS | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Inhibition | Cell-free biochemical assay | 9.9% of ~8,300 tested compounds showed activity [10]. | Treat luciferase-based assay hits with low confidence; confirm with orthogonal assay. |

| Autofluorescence (Blue, Green, Red) | Cell-based & cell-free | 0.5% (red) to 4.2% (green) of compounds showed autofluorescence in cell-based formats [10]. | Flag autofluorescent compounds for the corresponding channel; use alternative probes or detection channels. |

Problem 3: Inability to Distinguish Multiple Fluorescent Labels Due to Spectral Overlap

Potential Cause: Bleed-through between channels due to overlapping emission spectra of fluorophores.

Solutions:

- Microscope-Based Solutions:

- Sequential Acquisition with Narrow Bandpass Filters: Acquire each fluorophore separately using narrow bandpass emission filters to minimize bleed-through, though this can reduce signal intensity [11].

- Laser Multitracking (Confocal Microscopy): Use fast laser switching to excite only one fluorophore at a time, either line-by-line or frame-by-frame, to prevent simultaneous excitation of spectrally overlapping probes [11].

- Spectral Imaging and Linear Unmixing: This is the most robust solution. It involves capturing the entire emission spectrum at each pixel and using software to "unmix" the signals based on the reference spectrum of each individual fluorophore, effectively separating even highly overlapping signals [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a decision path for diagnosing and resolving these common issues:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quenching Autofluorescence in Fixed Tissue Sections with TrueBlack

This protocol is adapted from a 2023 study that successfully quenched autofluorescence in mouse adrenal cortex tissue [9].

Materials:

- TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher (Biotium, Cat. No. 23007)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Mounting medium

- Glass slides with fixed tissue sections

Method:

- Prepare Working Solution: Dilute TrueBlack reagent 1:20 in 70% ethanol. For example, add 1 mL of TrueBlack to 19 mL of 70% ethanol. Mix thoroughly.

- Apply Solution: Completely cover the fixed tissue sections with the diluted TrueBlack solution.

- Incubate: Incubate at room temperature for 30 seconds. Note: Do not exceed 2 minutes, as longer incubation times may quench specific signal.

- Rinse: Rinse the slides thoroughly with PBS (3 x 5 minutes each) to remove any residual quenching solution.

- Mount and Image: Proceed with standard mounting procedures using an appropriate mounting medium. Acquire images using your standard fluorescence microscopy parameters.

Validation: The efficacy can be validated by comparing the fluorescence intensity in the channel of interest before and after treatment. The protocol above achieved an 89-93% reduction in autofluorescence intensity [9].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Flagging Compound Interference in HCS

This protocol outlines steps to identify and triage compounds causing optical interference [8] [10].

Materials:

- HCS imaging system

- Image analysis software with statistical capabilities

- Data from a completed HCS run, including negative/positive controls and compound-treated wells

Method:

- Analyze Nuclear Counts: Perform statistical analysis on the number of cells (nuclear counts) per well. Compounds that are cytotoxic or disrupt cell adhesion will be outliers with significantly lower cell counts [8].

- Analyze Fluorescence Intensity: Perform statistical analysis on the raw fluorescence intensity values (e.g., from the nuclear or cytoplasmic channel). Compounds that are autofluorescent or act as quenchers will appear as statistical outliers [8].

- Manual Image Inspection: For all compounds flagged in steps 1 or 2, manually review the images. Look for:

- Fluorescence not associated with cellular structures.

- Compound precipitation or crystallization.

- Dramatic changes in cell morphology or confluency.

- Confirm with Orthogonal Assay: Subject the flagged compounds to a counter-screen or an orthogonal assay that uses a different detection method (e.g., a luminescent reporter assay for a screen that was originally fluorescent) to confirm if the observed activity is real or an artifact [8] [10].

The following diagram visualizes this multi-step filtering process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Managing Fluorescence Interference

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | Reduces tissue autofluorescence by quenching lipofuscin-like pigments [9]. | Ideal for fixed tissue sections with high intrinsic autofluorescence (e.g., adrenal cortex, liver). |

| MaxBlock Autofluorescence Reducing Reagent Kit | Reduces autofluorescence across a broad spectrum [9]. | Effective for various tissue types, providing a homogeneous background. |

| Sudan Black B | Stains lipids and reduces associated autofluorescence [9]. | Useful for lipid-rich tissues; can result in heterogeneous quenching. |

| TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit | Quenches autofluorescence from aldehyde-based fixation [9]. | A common method, though with lower efficacy than TrueBlack or MaxBlock. |

| D-Luciferin / Firefly Luciferase | Key reagents for luciferase-based reporter assays, an orthogonal technology to fluorescence [10]. | Used in counter-screens to rule out fluorescence-based compound interference. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Identifying and Mitigating Compound Autofluorescence

Description: Compound autofluorescence occurs when test compounds themselves fluoresce, emitting light within the detection range of your assay's fluorophores. This interference can produce false-positive signals or mask true biological activity, leading to incorrect conclusions about compound efficacy [8].

Detection Protocols:

- Statistical Analysis: Perform outlier analysis on fluorescence intensity data across all assay wells. Compounds showing intensity values significantly outside the distribution of negative controls may be autofluorescent [8].

- Image Review: Manually inspect images from compound-treated wells. Look for uniformly elevated background fluorescence or signal patterns that do not correspond to expected biological structures.

- Control Experiments: Run compound-only controls (compound in medium without cells) using the same imaging settings. The presence of signal confirms autofluorescence.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Wavelength Shift: If possible, switch to fluorophores with excitation/emission spectra outside the autofluorescence range of the compound.

- Orthogonal Assays: Confirm bioactivity using a non-image-based assay technology, such as a luminescence or absorbance-based readout [8] [12].

- Quenching/Bleaching: For fixed-cell assays, consider using autofluorescence quenching kits.

- Washing: Implement more stringent washing steps after compound treatment, though note that intracellular compound may not be fully removed [12].

Addressing Compound-Induced Cytotoxicity and Morphological Changes

Description: Test compounds may cause general cellular injury, death, or severe morphological alterations that are not related to the specific phenotypic target. This cytotoxicity can obscure the primary readout, reduce cell numbers below analysis thresholds, and be misinterpreted as a positive hit [8].

Detection Protocols:

- Cell Count Analysis: Monitor the number of cells per well. A substantial reduction compared to controls indicates cell loss due to death or detachment [8].

- Morphological Markers: Extract and analyze features indicative of cell health, such as nuclear size and condensation, membrane integrity, and actin cytoskeleton organization.

- Dedicated Cytotoxicity Assays: Run parallel assays for cell viability (e.g., ATP content) and membrane integrity (e.g., LDH release) on compound-treated cells.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Adaptive Imaging: Use an automated microscope setting that acquires images until a pre-set minimum number of cells is analyzed, though this can be time-consuming for highly cytotoxic compounds [8].

- Multiparametric Analysis: In your primary assay, include specific readouts for cytotoxicity (e.g., intensity of a dead cell stain) to flag and filter out toxic compounds early.

- Counter-Screens: Implement a cytotoxicity profiling assay against a relevant cell line to identify and deprioritize generally toxic compounds [8].

Correcting for Environmental and Preparation Artifacts

Description: Assay interference can originate from sources other than the compound, including media components, contaminants (dust, lint, microorganisms), and uneven staining or illumination [8].

Detection Protocols:

- Quality Control Checks:

- Illumination Correction: Image control wells without cells or fluorescent dyes to create a flat-field correction image that identifies optical irregularities [13].

- Artifact Identification: Train image analysis algorithms to recognize and exclude non-cellular objects based on size, shape, and intensity parameters [13].

- Background Measurement: Quantify fluorescence background in blank wells (media only) to assess interference from media components like riboflavins [8].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Use Optically Clean Plates: Select assay plates with low autofluorescence.

- Filter Media: Consider filtering media to reduce particulate contaminants.

- Include Controls: Distribute positive and negative controls across plates to control for edge effects and plate-to-plate variation [13].

- Standardize Protocols: Adhere to consistent cell culture, staining, and washing protocols to minimize technical variability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can a fluorescent compound still represent a viable HCS hit/lead? Yes. A compound that interferes with the assay technology via fluorescence may still be biologically active. Its viability as a hit should be confirmed using an orthogonal assay with a fundamentally different detection technology (e.g., luminescence, radiometric, or bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-BRET) to de-risk follow-up efforts. For structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies, it is preferable to use assays with minimal technology interference to avoid optimizing for fluorescence rather than bioactivity [12].

Q2: If washing steps are included in an HCS assay, why are technology interferences still present? Washing steps cannot be assumed to completely remove compound from within the cells. Just as intracellular stains are not washed away, small molecules can remain bound to cellular components or trapped inside organelles, leading to persistent interference during image acquisition [12].

Q3: Can technology-related compound interferences like fluorescence and quenching be predicted by chemical structure? To some extent. Compounds with extensive conjugated electron systems (aromatic rings) are more likely to be fluorescent. However, prediction is not always straightforward. Fluorescence can arise from sample impurities or degradation products, and otherwise non-fluorescent compounds can form fluorescent species due to cellular metabolism or the local biochemical environment (e.g., pH). Empirical testing under actual HCS assay conditions is recommended for definitive identification [12].

Q4: What should be done if an orthogonal assay is not available? In the absence of an orthogonal assay, the following steps can help de-risk a hit:

- Perform interference-specific counter-screens to characterize the compound's properties.

- Run selectivity assays in related and unrelated biological systems to see if the effect is specific.

- Use genetic perturbations (e.g., knockout, knockdown, or overexpression) of the putative target to see if it modulates the compound's effect. While these methods reduce risk, developing an orthogonal assay is highly recommended to confidently confirm bioactivity [12].

Q5: How does compound-mediated cytotoxicity appear in HCS data, and how can it be distinguished from a specific phenotype? Cytotoxicity often manifests as a significant reduction in cell count or dramatic, widespread changes in cellular morphology, such as cell rounding, shrinkage, or disintegration. It can be distinguished from a more specific phenotype by:

- Multiparametric Analysis: A cytotoxic compound will affect nearly all measured features (nuclear size, membrane integrity, metabolic markers) negatively and severely.

- Specific Phenotype: A compound with a specific MoA may alter a specific subset of features (e.g., only cytoskeletal structure) while leaving general health parameters unaffected.

- Dedicated Viability Markers: Incorporating a live/dead stain into the HCS panel provides a direct readout of cytotoxicity alongside the phenotypic readout [8].

The tables below summarize key quantitative information and thresholds relevant to identifying and managing interference in phenotypic screens.

Table 1: Thresholds for Identifying Common Interference Types from HCS Data

| Interference Type | Key Metric to Analyze | Statistical Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Autofluorescence | Fluorescence intensity across channels [8] | Values are extreme outliers from the negative control distribution |

| Fluorescence Quenching | Signal intensity in specific stained channels [8] | Values are extreme outliers from the negative control distribution |

| Cytotoxicity / Cell Loss | Number of cells identified per well (nuclear count) [8] | Values are extreme outliers from the negative control distribution |

| Altered Cell Adhesion | Number of cells identified per well [8] | Values are extreme outliers from the negative control distribution |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Profiling Modalities for Bioactivity Prediction

| Profiling Modality | Number of Assays Accurately Predicted (AUROC > 0.9) [6] | Key Strengths and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure (CS) Alone | 16 | Always available; no wet-lab work required. |

| Morphological Profiles (MO) Alone | 28 | Captures complex, biologically relevant information; largest number of unique predictions. |

| Gene Expression (GE) Alone | 19 | Provides direct readout of transcriptional pathways. |

| CS + MO (Combined) | 31 | ~2x improvement over CS alone; demonstrates high complementarity of data types. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for an Orthogonal Counterscreen to Confirm Hit Bioactivity

Purpose: To validate the bioactivity of hits identified in a primary HCS campaign, particularly those flagged for potential technology interference (e.g., autofluorescence), using a non-image-based detection method [8] [12].

Procedure:

- Select Orthogonal Technology: Choose a detection method orthogonal to HCS, such as:

- Luminescence (e.g., ATP quantification for viability, luciferase reporters)

- Time-Resolved Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (TR-FRET)

- Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET)

- Absorbance (e.g., tetrazolium reduction assays like MTT)

- Mass Spectrometry to measure a metabolic product

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed the same cell line used in the primary HCS assay into an appropriate plate for the orthogonal technology. Treat cells with the hit compounds, including the same positive and negative controls from the HCS.

- Assay Execution: Perform the orthogonal assay according to its optimized protocol, measuring the relevant biological endpoint.

- Data Analysis: Compare the dose-response curves and potency (EC50/IC50) of the hits between the HCS and the orthogonal assay. A true bioactive compound will show congruent activity in both assays, though the absolute potency may vary.

Protocol for a Hit Triage Workflow to Prioritize Phenotypic Hits

Purpose: To systematically prioritize hits from a primary HCS by filtering out compounds that act through undesirable or nonspecific mechanisms [8].

Procedure:

- Primary HCS: Conduct the initial phenotypic screen.

- In-Silico Triage:

- Chemical Property Filter: Remove compounds with undesirable physicochemical properties (e.g., reactive functional groups, poor solubility).

- Structural Similarity: Cluster hits and flag those structurally similar to known promiscuous or interfering compounds (e.g., frequent hitters).

- Interference Counter-Screens:

- Autofluorescence/Quenching Assay: Test hits in a cell-free system using the same fluorescence channels as the HCS.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Test hits in a general cell health/viability assay (e.g., ATP content) on the same cell line.

- Orthogonal Confirmation: Subject compounds that pass the above filters to the orthogonal assay protocol (4.1) for bioactivity confirmation.

- Selectivity Assessment: Test confirmed hits in a panel of unrelated cellular assays to assess selectivity versus general toxicity. Compounds causing modulation across unrelated assays may have nonspecific mechanisms.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Hit Triage and Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: MoA Deconvolution for Kartogenin

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HCS Assay Development and Counterscreening

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Dye Set | A multiplexed fluorescent dye kit staining nuclei, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleoli, Golgi/plasma membrane, actin cytoskeleton, and mitochondria [13] [14]. | Generating unbiased, high-dimensional morphological profiles for MoA prediction and hit identification. |

| L1000 Assay Kit | A high-throughput gene expression profiling method that measures 978 "landmark" transcripts [6]. | Providing transcriptomic profiles for MoA analysis and bioactivity prediction, complementary to imaging. |

| ATP Quantification Assay | A luminescence-based kit that measures ATP levels as a indicator of cell viability and metabolic activity. | Orthogonal counterscreen for cytotoxicity to triage HCS hits [8]. |

| TR-FRET or BRET Assay Kits | Assay technologies that use energy transfer between donors and acceptors, minimizing interference from compound autofluorescence. | Orthogonal confirmation of hits suspected of autofluorescence in standard HCS [12]. |

| shRNA/CRISPR Libraries | Collections of vectors for targeted gene knockdown or knockout to perturb specific cellular pathways. | Used in genetic modifier screens for MoA deconvolution and target identification [15]. |

The Economic and Timeline Costs of Overlooked Interference in Drug Discovery Pipelines

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Interference in Phenotypic High-Content Screening

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify, mitigate, and account for compound interference in phenotypic high-content screening (HCS). These artifacts can lead to false results, wasted resources, and significant economic costs in the drug discovery pipeline.

The Economic and Timeline Impact of Interference

Overlooked interference directly contributes to the high costs and extended timelines of drug discovery. The table below summarizes key cost drivers.

| Cost Factor | Economic Impact | Timeline Impact |

|---|---|---|

| False Positives/Negatives | Pursuing non-viable leads wastes screening and follow-up resources [8]. | Adds months of wasted effort on confirmatory screening, SAR, and orthogonal assays [8]. |

| Late-Stage Attrition | The cost of failure in clinical phases is immense; a single late-stage failure can represent a loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in R&D spending [16]. | Can result in a loss of 5-10 years of development time for a program that was doomed from the start by an artifactual early hit [8]. |

| Hit Triage & Deconvolution | Requires significant investment in counter-screens and orthogonal assays to distinguish true bioactivity from interference [8]. | Adds weeks or months to the early discovery timeline for secondary profiling and data analysis [8] [17]. |

| Overall R&D Intensity | Pharmaceutical R&D intensity (R&D spending as a percentage of sales) has increased from 11.9% to 17.7% (2008-2019), partly due to inefficiencies and the high cost of failure [16]. | The entire discovery process is prolonged, reducing the number of viable programs a research group can pursue per year. |

Troubleshooting Common Interference Artifacts

What is compound interference in high-content screening?

Compound interference refers to substances that produce artifactual bioactivity readouts without genuinely modulating the intended biological target or phenotype. This can be caused by the compound's optical properties, chemical reactivity, or general cellular toxicity, leading to both false positives and false negatives [8].

How do I troubleshoot autofluorescence interference?

Autofluorescence occurs when test compounds themselves fluoresce, emitting light in a similar range to your detection probes [8].

- Step 1: Assess the Signal. Review raw images from compound-treated wells. If you see elevated signal in channels where no fluorescent probe was added, autofluorescence is likely.

- Step 2: Confirm with a Control Experiment. Incubate the suspect compounds with your assay media in the absence of cells and acquire images. A clear signal confirms compound autofluorescence.

- Step 3: Mitigate the Issue.

- Spectral Scanning: If your microscope has this capability, scan the emission spectrum of the compound to identify its unique signature.

- Shift Wavelengths: If possible, switch to a fluorescent probe with excitation and emission spectra outside the autofluorescence range of the compound.

- Statistical Flagging: Perform statistical analysis of fluorescence intensity data; autofluorescent compounds will typically be outliers relative to control wells [8].

My data shows high cell loss; what could be the cause?

Substantial cell loss is often due to compound-mediated cytotoxicity or disruption of cell adhesion [8].

- Step 1: Check Morphology. Manually review images for classic signs of toxicity: cell rounding, membrane blebbing, and debris.

- Step 2: Analyze Nuclear Counts. Perform statistical analysis on the number of nuclei per well. Compounds causing significant cell loss will be clear outliers [8].

- Step 3: Implement a Viability Counter-Screen. Run a parallel assay using a dedicated cell viability or cytotoxicity probe (e.g., a live/dead stain) to confirm and quantify the toxic effect.

- Step 4: Mitigate for Analysis. For your primary screen, consider implementing an adaptive image acquisition process that captures multiple fields until a preset minimum number of cells is analyzed. This can help mitigate data loss from moderate cell loss [8].

How can I identify and confirm fluorescence quenching?

Quenching occurs when a compound absorbs emitted light, reducing the detectable signal from your fluorescent probe [8].

- Step 1: Identify Signal Drop. Look for wells where the fluorescence signal is unexpectedly low or absent, especially in a dose-dependent manner.

- Step 2: Perform a Control Experiment. Pre-incubate a solution of your fluorescent probe with the suspect compound in a microtube, then measure fluorescence with a plate reader. A reduction in signal compared to probe-alone controls confirms quenching.

- Step 3: Mitigate the Issue.

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Interference

Protocol 1: Autofluorescence and Quenching Counter-Screen

This protocol is designed to be run on all compounds in a library to create an interference profile.

Objective: To identify compounds that autofluoresce or quench signals in the spectral ranges used in your primary HCS assays.

Materials:

- Compound library

- Assay medium (without phenol red or other fluorescent components)

- Black-walled, clear-bottom 384-well microplates

- Multi-channel pipettes

- Fluorescent plate reader or HCS microscope

Method:

- Plate Preparation: Dilute compounds to the same concentration used in your primary screens. Dispense into wells containing only assay medium (no cells or probes).

- Image Acquisition: Using your HCS microscope, acquire images of the compound plates using all the fluorescence channels (wavelengths) employed in your phenotypic screens.

- Data Analysis:

- For autofluorescence: Calculate the mean fluorescence intensity per well in each channel. Flag compounds with intensity values >3 standard deviations above the plate median.

- For quenching: Add a control fluorescent dye (e.g., a free fluorophore) to all wells after the initial read. Re-acquire images. Flag compounds that reduce the control dye's signal by >30% compared to control wells.

Protocol 2: Orthogonal Viability Assay to Confirm Cytotoxicity

This protocol uses a different detection technology to confirm that cell loss is due to toxicity.

Objective: To confirm compound-induced cytotoxicity using an orthogonal, non-image-based method.

Materials:

- Cells and media from the primary screen

- White-walled 384-well cell culture microplates

- CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (or equivalent)

- Luminescence plate reader

Method:

- Cell Plating: Plate cells at the same density used in your HCS assay and treat with compounds using the same protocol.

- Assay Execution: At the HCS assay endpoint, equilibrate the plate to room temperature. Add a volume of CellTiter-Glo Reagent equal to the volume of media in the well.

- Measurement: Shake the plate for 2 minutes to induce cell lysis, then incubate for 10 minutes to stabilize the luminescent signal. Record luminescence on a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Normalize luminescence to untreated control wells. A significant decrease in luminescence confirms a loss of viable cells, validating the cytotoxicity observed in the HCS assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay | An unbiased, high-content morphological profiling technique that can be leveraged to predict compound bioactivity and mechanism of action, providing a rich dataset to contextualize interference [6]. |

| L1000 Gene Expression Assay | A scalable transcriptomic profiling method that provides complementary information to image-based profiling for predicting assay outcomes and understanding compound MOA [6]. |

| Reference Interference Compounds | A set of well-characterized compounds known to cause autofluorescence, quenching, or cytotoxicity. Used as positive controls in counter-screens to validate assay performance [8]. |

| Phenol Red-Free Medium | Reduces background fluorescence from media components, which is crucial for live-cell imaging and for running autofluorescence counter-screens [8]. |

| Orthogonal Assay Kits | Kits using non-optical readouts (e.g., luminescence for viability, AlphaScreen for binding) are essential for confirming true bioactivity when interference is suspected [8]. |

| Data Fusion & Machine Learning | Computational approaches that integrate chemical structure (CS) with phenotypic profiles like morphology (MO) and gene expression (GE) can significantly improve the prediction of true bioactivity over any single data source alone [6]. |

FAQs on Interference and Screening Economics

Why is phenotypic screening particularly vulnerable to interference?

HCS assays detect perturbations in cellular targets and phenotypes regardless of whether they arise from desirable or undesirable mechanisms. Since they rely on the transmission and reflectance of light for signal detection, optically active substances (autofluorescent compounds, quenchers, colored compounds) can alter readouts independent of a true biological effect [8].

What is the single biggest source of artifacts in HCS?

The major source of artifacts and interference in HCS assays are the test compounds themselves. This can be divided into fluorescence detection technology-related issues (autofluorescence, quenching) and non-technology-related issues (cytotoxicity, dramatic morphology changes) [8].

How can computational methods help reduce costs from interference?

Computational methods can predict compound activity by integrating chemical structure with phenotypic profiles (Cell Painting, L1000). One study showed that while chemical structures alone could predict 16 assays, combining them with phenotypic data allowed accurate prediction of 44 assays. This "virtual screening" can prioritize compounds less likely to cause interference, saving wet-lab resources [6].

What are the key differences between technology-related and biology-related interference?

This troubleshooting diagram outlines the two main categories and how to diagnose them.

How does the cost of early-stage interference compare to late-stage failure?

While the direct cost of a single early-stage screening failure is relatively small, the cumulative cost of pursuing false leads is substantial. More critically, a compound with overlooked interference that progresses undetected into development can lead to a late-stage failure, which is catastrophic. The expected capitalized cost to develop a new drug, accounting for failures and capital, is estimated at $879.3 million. A single late-stage failure wastes a significant portion of this investment and many years of work [16].

Advanced Assay Design and AI Integration for Interference-Resistant HCS

Leveraging Multiplexed and Label-Free Assays to Minimize Interference

FAQs: Addressing Common Questions on Interference

What are the primary advantages of using label-free assays in high-content screening? Label-free techniques enable the monitoring of biomolecular interactions with native binding partners, without the interference from fluorescent or other tags. This avoids altered chemical properties, steric hindrance, and complex synthetic steps, leading to more accurate biochemical data. Many label-free platforms also provide real-time kinetic information on association and dissociation events [18].

How can multiplexed assays help in overcoming challenges with heterogeneous biological samples? Biological samples like small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are highly heterogeneous, and a single biomarker is often insufficient for accurate diagnostics. Multiplexed assays, which simultaneously detect multiple biomarkers, ensure a more comprehensive capture of target populations and improve diagnostic accuracy by accounting for patient-to-patient variability in biomarker expression levels [19].

What are common sources of compound-mediated interference in phenotypic screening? Compound interference can be broadly divided into technology-related and biology-related effects. A major technology-related effect is compound autofluorescence or fluorescence quenching, which can produce artifactual readouts. Common biology-related effects include cellular injury or cytotoxicity, and dramatic changes in cell morphology or adhesion, which can lead to false positives or negatives [8].

My assay is showing high background signal. Could this be due to my reagents? Yes, media components can be a source of autofluorescence. For instance, riboflavins in culture media fluoresce in the ultraviolet through green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant spectral ranges and can elevate fluorescent backgrounds in live-cell imaging applications [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Label-Free and Multiplexed Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | - Low sensitivity of technique for small molecules.- Receptor not properly immobilized on sensor surface. | - For SPR, use high-quality optics or an allosteric receptor to amplify refractive index change [18].- Ensure proper surface chemistry and confirmation of receptor binding [20]. |

| Low Specificity in Complex Samples | - Complex SERS spectra in label-free detection.- Non-specific binding to the sensor surface. | - Employ label-based SERS nanotags for clearer, quantifiable signals [19].- Implement rigorous blocking steps and control experiments to differentiate specific from non-specific binding [20]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | - Instability of SERS nanotags.- Inconsistent cell seeding density. | - Standardize nanotag synthesis (structure, Raman reporter, bioconjugation) [19].- Optimize and control cell seeding density during assay development [8]. |

| High Background Noise | - Autofluorescence from media or cell components.- Insufficient washing steps. | - Use label-free methods or media with low autofluorescence [8] [18].- Follow recommended washing procedures, ensuring complete drainage between steps [21]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Runs | - Fluctuations in incubation temperature or timing.- Variation in reagent preparation. | - Maintain consistent incubation temperature and timing as per protocol [21].- Check pipetting technique and double-check dilution calculations [21]. |

Troubleshooting Compound Interference in Phenotypic Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Cytotoxicity | - Compound-mediated cell death or detachment. | - Statistical analysis of nuclear counts and intensity to identify outliers [8].- Use adaptive image acquisition to image until a threshold cell count is met [8]. |

| False Positive/Negative Results | - Compound autofluorescence or fluorescence quenching.- Undesirable compound mechanisms (e.g., chemical reactivity, aggregation). | - Identify outliers via statistical analysis of fluorescence intensity data [8].- Manually review images and implement orthogonal, label-free assays [8]. |

| Dramatic Morphological Changes | - Desirable or undesirable compound-mediated effects on cell morphology. | - Deploy a testing paradigm with appropriate counter-screens and orthogonal assays to confirm hits [8]. |

| Assay Signal Too High (Signal Saturation) | - Dead cells rounding up can concentrate fluorescence probes, saturating the camera detector. | - Optimize cell seeding density and probe concentration during assay development [8]. |

Table 1: Comparison of Label-Free Detection Techniques [20]

| Technique | Principle | Key Applications | Sensitivity | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures changes in refractive index near a metal surface. | Studying association/dissociation kinetics, drug discovery. | ~10 ng/mL for casein | Medium (++)) |

| SPR Imaging (SPRi) | Captures an image of reflected polarized light to detect multiple interactions simultaneously. | DNA-protein interaction, disease marker detection on microarrays. | ~64.8 zM (best achievable) | High (+++)) |

| Ellipsometry | Measures change in polarization state of incident light. | Real-time biomolecular interaction measurement, clinical diagnosis. | ~1 ng/mL | Low (+)) |

| Optical Interferometry | Detection of optical phase difference due to biomolecular mass accumulation. | Protein-protein interaction monitoring. | ~19 ng/mL | Medium (++)) |

| Nanowires/Nanotubes | Detects changes in electrical conductance after target binding. | Cancer marker detection in human serum. | ~1 fM (best achievable) | Low (+)) |

Table 2: Performance of Data Modalities in Predicting Compound Bioactivity [6]

| Profiling Modality | Number of Assays Accurately Predicted (AUROC > 0.9) |

|---|---|

| Chemical Structure (CS) alone | 16 |

| Morphological Profiles (MO) alone | 28 |

| Gene Expression (GE) alone | 19 |

| CS + MO (combined via data fusion) | 31 |

| Best of CS or MO (retrospective) | 44 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Setting up a Label-Free SPR Binding Assay

Objective: To measure the binding kinetics of a small molecule drug to its immobilized protein target using Surface Plasmon Resonance.

Materials:

- SPR instrument (e.g., Biacore series)

- Sensor chip (e.g., CM5 for gold surface)

- Running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% v/v Surfactant P20, pH 7.4)

- Purified target protein

- Compounds for screening (dissolved in DMSO)

- Amine-coupling kit (containing N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), and ethanolamine)

Method:

- Surface Preparation: Dock the sensor chip and prime the system with running buffer.

- Ligand Immobilization:

- Activate the carboxymethylated dextran surface by injecting a 1:1 mixture of NHS and EDC for 7 minutes.

- Dilute the target protein in a sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0-5.0, optimized for your protein) and inject it over the activated surface until the desired immobilization level (Response Units, RU) is achieved.

- Block any remaining activated groups by injecting ethanolamine-HCl for 7 minutes.

- Use one flow cell as a reference surface, activated and blocked without protein.

- Analyte Binding Kinetics:

- Dilute compounds in running buffer, ensuring the final DMSO concentration matches that in the running buffer (typically ≤1%).

- Set the instrument method to include a 60-second baseline, a 60-180 second association phase (compound injection), and a 120-300 second dissociation phase (running buffer only).

- Inject each compound over both the reference and protein surfaces at a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the reference cell sensorgram from the ligand cell sensorgram.

- Fit the double-referenced data to a 1:1 binding model to calculate the association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = kd/ka).

Troubleshooting Notes: If no binding is observed for a positive control, check protein activity post-immobilization and ensure DMSO concentrations are perfectly matched to prevent bulk shift effects [18].

Protocol: Multiplexed SERS Immunoassay for Extracellular Vesicle Detection

Objective: To simultaneously detect multiple protein biomarkers on the surface of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) nanotags.

Materials:

- SERS-active substrate (e.g., gold nanostar-coated plate)

- Capture antibodies (e.g., anti-CD63, anti-HER2, anti-EpCAM)

- SERS nanotags: Gold nanoparticles conjugated with unique Raman reporter molecules and specific detection antibodies.

- Washing buffers (e.g., PBS with Tween)

- Blocking buffer (e.g., BSA in PBS)

Method:

- Substrate Functionalization: Spot the different capture antibodies onto distinct locations on the SERS substrate. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Wash the substrate and incubate with blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature to minimize non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Isolate sEVs from plasma or cell culture supernatant. Add the sEV sample to the substrate and incubate for 2 hours, allowing vesicles to be captured by their cognate antibodies.

- Labeling with SERS Nanotags: Wash away unbound sEVs. Incubate the substrate with a mixture of SERS nanotags for 1 hour. Each nanotag type targets a different sEV surface marker.

- Signal Acquisition and Reading: Perform a final wash to remove unbound nanotags. Air dry the substrate and acquire SERS spectra from each spot using a Raman microscope. The unique Raman signature of each nanotag allows for multiplexed detection.

Troubleshooting Notes: Issues with specificity can arise from cross-reactivity of antibodies or non-specific adsorption of nanotags. Include controls without sEVs and with isotype-matched antibodies. Reproducibility issues can stem from batch-to-batch variations in nanotag synthesis; characterize nanotags thoroughly before use [19].

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Assay Interference Pathway

Multiplexed sEV Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Label-Free and Multiplexed Assays

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5) | Gold surface with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent immobilization of protein targets. | Immobilizing kinases or GPCRs for small molecule binding studies in drug discovery [18]. |

| SERS-Active Substrates | Nanostructured metal surfaces (Au, Ag) that create "hot spots" for massive enhancement of Raman signals. | Ultrasensitive, multiplexed detection of cancer-derived extracellular vesicle (sEV) biomarkers [19]. |

| SERS Nanotags | Gold nanoparticles encoded with a unique Raman reporter and conjugated to a detection antibody. | Acting as a multiplexed, photostable label in immunoassays to simultaneously detect CD63, HER2, and EpCAM on sEVs [19]. |

| Label-Free Cell-Based Biosensors | Microplates with embedded sensors to monitor cell status in real-time without labels. | Monitoring dynamic cell responses, such as adhesion and morphology changes, to compounds like EGCG [22]. |

| Antibody/Aptamer Pairs | High-specificity capture and detection molecules for target biomolecules. | Capturing specific sEV subpopulations or proteins in multiplexed microarray or SERS assays [20] [19]. |

The Role of High-Content Cytometry and 3D Organoids in Creating More Physiologically Relevant, Robust Assays

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting 3D Organoid High-Content Screening

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | High morphological variability between organoids | Inconsistent generation protocols; inter-operator variability [23] | Implement AI-driven micromanipulators (e.g., SpheroidPicker) for pre-selection of morphologically homogeneous 3D-oids [23]. |

| Poor stain penetration | Dyes and antibodies cannot effectively penetrate the dense 3D structure [24] | Increase dye concentration (e.g., 2X-3X for Hoechst) and extend staining duration (e.g., 2-3 hours instead of 15-20 minutes) [24]. | |

| Imaging & Acquisition | Blurry images, high background | Use of non-confocal widefield microscopy; light scattering in thick samples [24] | Use confocal imaging (e.g., spinning disk confocal) to acquire optical sections and reduce background haze [25] [24] [26]. |

| Organoid not in field of view | Spheroids drifting in flat-bottom plates [24] | Use U-bottom plates to keep samples centered; employ targeted acquisition features (e.g., QuickID) to locate objects [24] [26]. | |

| Long acquisition times | Excessive number of z-steps; slow exposure times [24] | Optimize z-step distance (e.g., 3-5 µm for 20X objective); use water immersion objectives and high-intensity lasers to shorten exposure [24] [26]. | |

| Data Analysis | Low sensitivity in detecting phenotypic changes | Reliance on biochemical viability assays instead of image-based read-outs [25] [27] | Use high-content, image-based phenotypic analysis, which is more sensitive for assessing organoid drug response [25] [27]. |

| Inaccurate 3D quantification | Using 2D analysis tools on 3D structures [24] | Use analysis software with 3D capabilities (e.g., "Find round object" tool, 3D volumetric analysis) [24] or AI-based custom 3D data analysis workflows [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is robotic liquid handling preferred over manual pipetting for 3D organoid screening assays? Robotic liquid handling demonstrates improved precision and offers automated randomization capabilities, making it more consistent and amendable to high-throughput experimental designs compared to manual pipetting [25] [27].

Q2: What is the key advantage of using image-based phenotyping over traditional biochemical assays for 3D organoid screening? Image-based techniques are more sensitive for detecting phenotypic changes within organoid cultures following drug treatment. They can provide differential read-outs from complex models, such as single-well co-cultures, which biochemical viability assays might miss [25] [27].

Q3: How can I reduce the high variability of organoids in my screening assay? Variability can be addressed at multiple stages. During generation, strict protocol adherence is key, though some inter-operator variability may persist [23]. Post-generation, utilize AI-driven tools to select morphologically homogeneous 3D-oids for screening, ensuring a more uniform starting population [23].

Q4: What type of multi-well plate is best for 3D organoid imaging? 96- or 384-well clear bottom plates with a U-bottom design are recommended. These plates help keep the spheroid centered and in place during image acquisition, unlike flat-bottom plates which can lead to samples drifting out of the field of view [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated High-Content Screening of Organoids

This protocol is adapted from the development of an automated 3D high-content cell screening platform for organoid phenotyping [25] [27].

1. Organoid Generation and Seeding:

- Generate organoids from primary human biopsies or patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models.

- Seed organoids into a 384-well U-bottom plate optimized for 3D imaging.

2. Compound Treatment:

- Use a robotic liquid handler for consistent and precise dispensing of drug compounds or other treatments into the multi-well plates. This improves precision and enables automated randomization [25] [27].

3. Staining and Fixation:

- Fix organoids as required by the assay.

- Note that staining 3D structures requires optimization. For nuclear stains like Hoechst, use a 2X-3X greater concentration and allow for extended staining times of 2-3 hours to ensure deep penetration [24].

4. High-Content Confocal Imaging:

- Use a confocal high-content imaging system (e.g., ImageXpress Confocal HT.ai) [26].

- Acquire z-stacks through the entire volume of the organoids. A suggested starting point for a 20X objective is a 3-5 µm distance between z-steps [24].

- Use water immersion objectives to improve image resolution and minimize aberrations for brighter intensity at lower exposure times [24] [26].

5. Image and Data Analysis:

- Use maximum projection algorithms to collapse z-stacks into a single 2D image for simpler analysis, or perform full 3D analysis [24].

- Leverage AI-driven software (e.g., IN Carta Software) for complex segmentation, phenotypic classification, and 3D volumetric measurements [23] [26].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Spheroid Model Variability

This protocol is used to quantify the heterogeneity in spheroid generation, a critical factor for robust screening [23].

1. Spheroid Generation:

- Monoculture: Seed 100 cells per well in a 384-well U-bottom cell-repellent plate. Incubate for 48 hours before fixation.

- Co-culture: Seed 40 cancer cells (e.g., HeLa Kyoto) per well. After 24 hours, add 160 fibroblast cells (e.g., MRC-5). Incubate for another 24 hours before fixation.

- To assess variability, have multiple experts generate spheroids using the same protocol and equipment.

2. Image Acquisition:

- Image each spheroid using different magnification objectives (e.g., 2.5x, 5x, 10x, and 20x) to compare the accuracy of feature extraction at different resolutions.

3. Feature Extraction:

- Manually annotate each spheroid in the acquired images.

- Use image analysis software (e.g., BIAS, ReViSP) to extract 2D morphological features such as Diameter, Perimeter, Area, Volume 2D, Circularity, Sphericity 2D, and Convexity.

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare the extracted features between different operators and between mono- and co-cultures.

- Statistical analysis (e.g., significance testing) will reveal the degree of inter-operator and inter-model variability.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D Organoid Screening

| Item | Function in the Assay | Example or Specification |

|---|---|---|

| U-Bottom Microplates | To form and hold spheroids/organoids in a centered position for reliable imaging [24]. | 96- or 384-well clear bottom plates (e.g., Corning round U-bottom plates) [24]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handler | For consistent, precise dispensing of compounds and reagents to minimize variability in high-throughput designs [25] [27]. | Automated systems with randomization capabilities. |

| Confocal HCS System | For acquiring high-resolution optical sections of 3D samples, reducing background haze [25] [24] [26]. | Systems with water immersion objectives and spinning disk confocal technology (e.g., ImageXpress Confocal HT.ai) [26]. |

| Water Immersion Objectives | To improve image resolution and geometric accuracy by matching the refractive index of the sample, allowing lower exposure times [24] [26]. | 20X, 40X, and 60X water immersion objectives [26]. |

| AI-Based Analysis Software | For complex segmentation, phenotypic classification, and 3D volumetric analysis of large, heterogeneous image datasets [23] [26]. | Software with machine learning capabilities (e.g., IN Carta, BIAS) [23] [26]. |

| SpheroidPicker | An AI-driven micromanipulator for selecting and transferring morphologically homogeneous 3D-oids to ensure experimental reproducibility [23]. | Custom AI-guided 3D cell culture delivery system [23]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

3D Organoid HCS Workflow

Troubleshooting Decision Pathway

Automated Detection and Filtration of Interference Patterns in Image-Based Data

Core Interference Concepts & FAQs

This section addresses the fundamental types of interference encountered in high-content screening (HCS) and provides initial troubleshooting guidance.

Interference in HCS can be broadly categorized into two groups: technology-related detection interference and biological interference [8].

Technology-Related Detection Interference: This occurs when the physical or chemical properties of a test compound disrupt the optical detection system.

- Compound Autofluorescence: The test compound itself fluoresces, creating a background signal that can mask the specific fluorescent signal from your probes or labels [8].

- Fluorescence Quenching: The test compound absorbs the excitation or emission light from fluorophores, reducing or eliminating the detectable signal [8].

- Optical Interference: Colored or pigmented compounds can alter light transmission and reflection, while insoluble compounds can scatter light [8].

Biological Interference (Undesirable MOAs): This occurs when the compound induces biological effects that confound the specific phenotypic readout.

- Cytotoxicity: Compound-induced cell death or injury leads to a substantial loss of cells, making statistical analysis unreliable [8].

- Altered Cell Morphology/Adhesion: Compounds that cause cells to round up, detach, or dramatically change shape can disrupt image segmentation and analysis algorithms [8].

- Nonspecific Mechanisms: This includes chemical reactivity, colloidal aggregation, redox-cycling, and chelation, which can produce phenotypes not related to the target's modulation [8].

My positive controls are working, but my screen is yielding an unusually high hit rate. What should I check?

A high hit rate often indicates widespread interference. Follow this initial troubleshooting flowchart to diagnose the issue.

AI & Deep Learning Solutions

This section details specific algorithms and workflows for automating the detection and filtration of interference patterns.

Which deep learning algorithms are best suited for detecting interference in HCS image data?

Different algorithms excel at identifying specific types of interference. The table below summarizes the top algorithms for this application, their key mechanisms, and primary use cases in HCS interference detection.

Table 1: Deep Learning Algorithms for HCS Interference Detection

| Algorithm | Category | Key Mechanism | Best for HCS Interference Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [28] | Deep Learning | Uses convolutional layers to learn spatial hierarchies of features directly from pixels [28]. | General-purpose autofluorescence detection, classifying whole-well image patterns. |

| Auto-Encoder (AE) [28] | Deep Learning, Unsupervised | Encodes input data into a compressed representation (bottleneck) and decodes it back, learning efficient data patterns [28]. | Anomaly Detection: Identifying outlier images with interference by reconstructing "normal" images and flagging high-reconstruction-error wells [28]. |

| You Only Look Once (YOLO) [29] | Deep Learning, Real-Time | A single-stage object detector that predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities directly from full images in one evaluation [29]. | Rapidly locating and classifying debris, lint, or aggregates within a well. |

| Mask R-CNN [29] | Deep Learning, Instance Segmentation | Extends Faster R-CNN by adding a branch to predict segmentation masks for each object instance [29]. | Precisely segmenting individual cells in the presence of interference to check for cytotoxicity (cell count) or morphological anomalies. |

| Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [29] | Classical Computer Vision | Detects and describes local keypoints that are robust to image scaling, rotation, and illumination changes [29]. | Identifying and matching specific interference patterns (e.g., consistent fiber shapes) across multiple wells. |

What is a typical AI-powered workflow for filtering interference?

An effective workflow integrates multiple AI models to sequentially filter different types of interference, ensuring only high-quality, biologically relevant data proceeds to downstream analysis. The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage process.

Experimental Protocols & Validation

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing counter-screens and validating potential hits.

What is the definitive experimental protocol to confirm autofluorescence or quenching?

This protocol uses a compound-only control to isolate technology-based interference from biological effects [8].

Objective: To determine if a compound's activity is due to genuine biological modulation or technology-based interference (autofluorescence or quenching).

Materials:

- Test compound(s)

- Assay plates (identical to those used in primary HCS)

- Complete cell culture medium (with serum)

- All fluorescent dyes/probes used in the primary HCS assay

- HCS imaging system

Procedure:

- Prepare Compound Plates: Create a duplicate of your assay plate, but do not seed any cells.

- Dispense Compounds: Add your test compounds to the cell-free plate using the same concentrations and volumes as your primary screen.

- Add Media and Probes: Add complete cell culture medium and all fluorescent dyes/probes exactly as you would in the live-cell assay. Incubate the plate under the same conditions (time, temperature, CO₂).

- Image Acquisition: Image the plate using the identical channel settings, exposure times, and light sources as your primary HCS.

- Data Analysis:

- Autofluorescence Positive: If a well shows a significantly elevated signal in a specific channel compared to negative control wells (containing only medium and dyes), the compound is autofluorescent in that channel [8].

- Quenching Positive: If a well shows a significantly reduced signal from the fluorescent dyes compared to negative controls, the compound is a quencher [8].

How can I use orthogonal assays to validate hits from a phenotypic screen?

Orthogonal assays use a fundamentally different detection technology (non-image-based) to verify the biological activity of a compound, thereby ruling out image-specific artifacts [8] [6].

Objective: To confirm the biological activity of primary HCS hits using a non-image-based readout.

Rationale: If a compound produces a congruent activity in an orthogonal assay, it is highly likely to be a true bioactive molecule and not an artifact of the HCS imaging process [6].

Table 2: Orthogonal Assay Strategies for Common HCS Readouts

| HCS Readout (Phenotypic) | Example Orthogonal Assay Technology | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Reporter (e.g., GFP expression) | Luciferase Reporter Assay | Measures a bioluminescent signal, which is not affected by fluorescent compound interference [8]. |

| Protein Translocation (e.g., NF-κB nuclear translocation) | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) or qPCR of target genes | Measures DNA-binding activity or downstream transcriptional effects biochemically/molecularly [8]. |

| Cell Viability / Cytotoxicity | ATP-based Assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) | Quantifies ATP levels as a luminescent readout, independent of fluorescent dye incorporation or morphological analysis [8]. |

| Second Messenger Signaling (e.g., Ca²⁺ flux) | Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) | Uses energy transfer between a luciferase and a fluorescent protein, which is less prone to certain types of interference than direct fluorescence [8]. |

| General Phenotypic Profiling | Transcriptomic Profiling (L1000 assay) | Provides a complementary, high-dimensional biological signature that can be used to predict compound bioactivity and confirm mechanism [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogs essential materials and their functions for developing robust HCS assays and interference counter-screens.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HCS and Interference Mitigation

| Item | Function in HCS | Role in Interference Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Dye Set (e.g., MitoTracker, Concanavalin A, Phalloidin, etc.) [6] | Generates a multi-parametric morphological profile for phenotypic screening and Mechanism of Action (MOA) prediction [6]. | Provides a rich, multi-channel dataset. AI models can be trained on this data to identify interference as an "anomalous" profile that doesn't match known MOAs [6]. |

| Cell Viability Indicator (Luminescent) (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) | Quantifies ATP content as a bioluminescent readout of metabolically active cells. | Serves as a key orthogonal assay to confirm that effects seen in fluorescent viability dyes (e.g., propidium iodide) are real and not caused by fluorescence quenching [8]. |

| Reference Interference Compounds [8] | A set of well-characterized compounds known to cause autofluorescence, quenching, cytotoxicity, or aggregation. | Used as positive controls during assay development and AI model training to teach algorithms what interference "looks like" [8]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) / Extracellular Matrix (ECM) [8] | Coating for microplates to enhance cell adhesion and spreading. | Mitigates artifacts from compound-induced cell detachment, ensuring a consistent number of cells for image analysis [8]. |

| Graph Convolutional Net (GCN) Software Libraries [6] | Used to compute chemical structure profiles (CS) from compound structures. | Enables the integration of chemical structure data with phenotypic profiles (MO/GE) to improve the prediction of true bioactivity and filter out interference [6]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Question 1: How much sequencing data is required for one sample in a CRISPRi screen?

It is generally recommended that each sample achieves a sequencing depth of at least 200x [30]. The required data volume can be estimated using the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate [30]. For example, when using a human whole-genome knockout library, the typical sequencing requirement per sample is approximately 10 Gb [30].

Question 2: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance?

Gene editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence [30]. To enhance the reliability and robustness of screening results, it is recommended to design at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene [30]. For even more reliable hit-gene calling in bacterial systems, 10 sgRNAs per gene is sufficient, with priority given to those located within the first 5% of the ORF proximal to the start codon [31].

Question 3: If no significant gene enrichment is observed, could it be a problem with statistical analysis?

In most cases, the absence of significant gene enrichment is less likely due to statistical analysis errors, and more commonly a result of insufficient selection pressure during the screening process [30]. When the selection pressure is too low, the experimental group may fail to exhibit the intended phenotype, thereby weakening the signal-to-noise ratio [30]. To address this, increase the selection pressure and/or extend the screening duration [30].

Question 4: What is the difference between negative and positive screening in CRISPRi?