Chemogenomics Meets NGS: A Revolutionary Partnership in Modern Drug Discovery

This article explores the powerful synergy between chemogenomics and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in accelerating drug discovery and development.

Chemogenomics Meets NGS: A Revolutionary Partnership in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the powerful synergy between chemogenomics and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in accelerating drug discovery and development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview—from foundational principles and core methodologies to advanced optimization strategies and comparative validation of technologies. We examine how NGS enables high-throughput genetic analysis to identify drug targets, understand mechanisms of action, and advance personalized medicine, while also addressing key challenges like data analysis and workflow optimization to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage these integrated approaches effectively.

The Foundations of Chemogenomics and the NGS Revolution

Chemogenomics, also known as chemical genomics, represents a systematic approach in chemical biology and drug discovery that involves the screening of targeted chemical libraries of small molecules against families of biological targets, with the ultimate goal of identifying novel drugs and drug targets [1]. This field strategically integrates combinatorial chemistry with genomic and proteomic biology to study the response of a biological system to a set of compounds, thereby facilitating the parallel identification of biological targets and biologically active compounds [2]. The completion of the human genome project provided an abundance of potential targets for therapeutic intervention, and chemogenomics strives to study the intersection of all possible drugs on all these potential targets, creating a comprehensive ligand-target interaction matrix [1] [3].

At its core, chemogenomics uses small molecules as probes to characterize proteome functions. The interaction between a small compound and a protein induces a phenotype, and once this phenotype is characterized, researchers can associate a protein with a molecular event [1]. Compared with genetic approaches, chemogenomics techniques can modify the function of a protein rather than the gene itself, offering the advantage of observing interactions and reversibility in real-time [1]. The modification of a phenotype can be observed only after the addition of a specific compound and can be interrupted after its withdrawal from the medium, providing temporal control that genetic modifications often lack [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Chemogenomics

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Systematic identification of small molecules that interact with gene products and modulate biological function [1] [4] |

| Scope | Investigation of classes of compounds against families of functionally related proteins [5] |

| Core Principle | Integration of target and drug discovery using active compounds as probes to characterize proteome functions [1] |

| Data Structure | Comprehensive ligand-target SAR (structure-activity relationship) matrix [3] |

| Key Advantage | Enables temporal and spatial control in perturbing cellular pathways compared to genetic approaches [1] [4] |

Core Chemogenomic Strategies and Approaches

Forward vs. Reverse Chemogenomics

Currently, two principal experimental chemogenomic approaches are recognized: forward (classical) chemogenomics and reverse chemogenomics [1]. These approaches represent complementary strategies for linking chemical compounds to biological systems, each with distinct methodologies and applications.

Forward chemogenomics begins with a particular phenotype of interest where the molecular basis is unknown. Researchers identify small compounds that interact with this function, and once modulators are identified, they are used as tools to identify the protein responsible for the phenotype [1]. For example, a loss-of-function phenotype such as the arrest of tumor growth might be studied. The primary challenge of this strategy lies in designing phenotypic assays that lead immediately from screening to target identification [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for discovering novel biological mechanisms and unexpected drug targets.

Reverse chemogenomics takes the opposite pathway. It begins with small compounds that perturb the function of an enzyme in the context of an in vitro enzymatic test [1]. After modulators are identified, the phenotype induced by the molecule is analyzed in cellular systems or whole organisms. This method serves to identify or confirm the role of the enzyme in the biological response [1]. Reverse chemogenomics used to be virtually identical to target-based approaches applied in drug discovery over the past decade, but is now enhanced by parallel screening and the ability to perform lead optimization on many targets belonging to one target family [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Forward and Reverse Chemogenomics Approaches

| Characteristic | Forward Chemogenomics | Reverse Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotype with unknown molecular basis [1] | Known protein or molecular target [1] |

| Screening Focus | Phenotypic assays on cells or organisms [1] | In vitro enzymatic or binding assays [1] |

| Primary Challenge | Designing assays that enable direct target identification [1] | Connecting target engagement to relevant phenotypes [1] |

| Typical Applications | Target deconvolution, discovery of novel biological pathways [1] | Target validation, lead optimization across target families [1] |

| Throughput Capacity | Generally lower due to complexity of phenotypic assays [1] | Generally higher, amenable to parallel screening [1] |

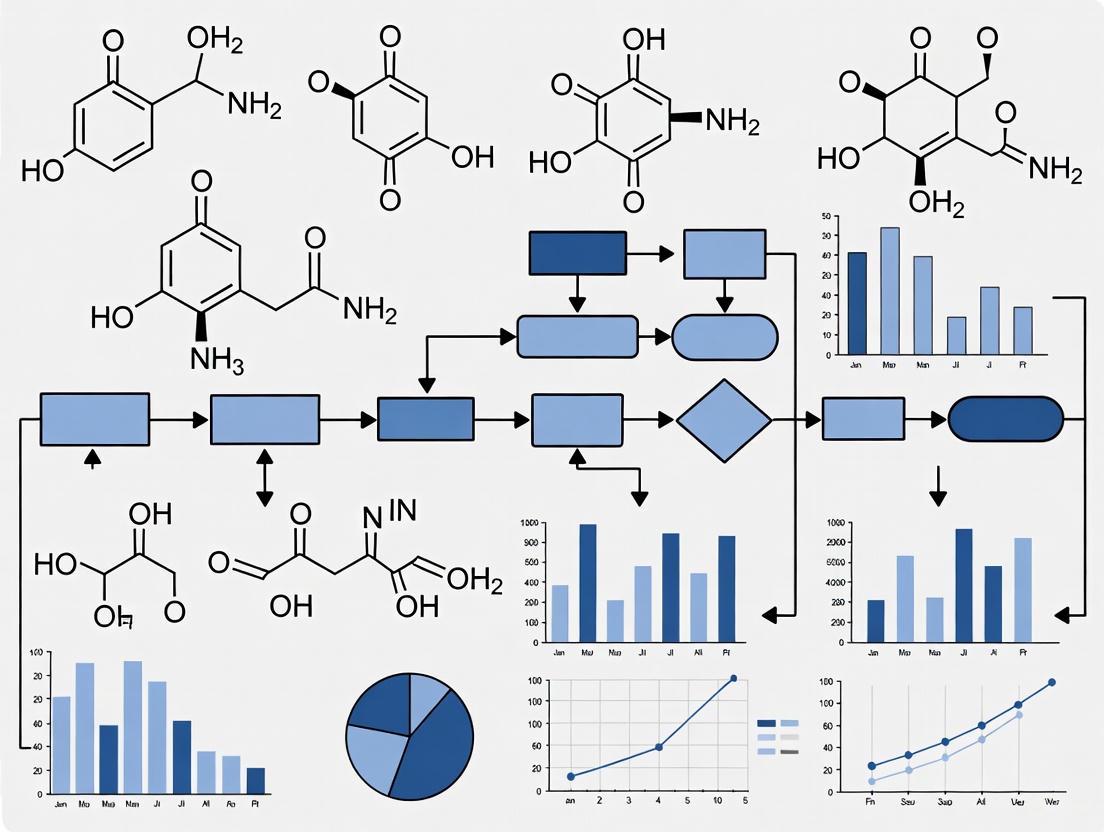

Diagram 1: Chemogenomics Workflow Strategies. This diagram illustrates the parallel pathways of forward (phenotype-first) and reverse (target-first) chemogenomics approaches, ultimately converging on validated target-compound pairs.

The Chemogenomics Library

Central to both chemogenomics strategies is a collection of chemically diverse compounds, known as a chemogenomics library [2]. The selection and annotation of compounds for inclusion in such a library present a significant challenge, as optimal compound selection is critical for success [2]. A common method to construct a targeted chemical library is to include known ligands of at least one, and preferably several, members of the target family [1]. Since a portion of ligands designed and synthesized to bind to one family member will also bind to additional family members, the compounds in a targeted chemical library should collectively bind to a high percentage of the target family [1].

The concept of "privileged structures" has emerged as an important consideration in chemogenomics library design [5]. These are scaffolds, such as benzodiazepines, that frequently produce biologically active analogs within a target family [5]. Similarly, compounds from traditional medicine sources like Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda are often included in chemogenomics libraries because they tend to be more soluble than synthetic compounds, have "privileged structures," and have more comprehensively known safety and tolerance factors [1].

Key Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Determining Mechanism of Action

Chemogenomics has proven particularly valuable in determining the mode of action (MOA) for therapeutic compounds, including those derived from traditional medicine systems [1]. For Traditional Chinese Medicine class of "toning and replenishing medicine," chemogenomics approaches have identified sodium-glucose transport proteins and PTP1B (an insulin signaling regulator) as targets linking to hypoglycemic phenotypes [1]. Similarly, for Ayurvedic anti-cancer formulations, target prediction programs enriched for targets directly connected to cancer progression such as steroid-5-alpha-reductase and synergistic targets like the efflux pump P-gp [1].

Beyond traditional medicine, chemogenomics can be applied early in drug discovery to determine a compound's mechanism of action and take advantage of genomic biomarkers of toxicity and efficacy for application to Phase I and II clinical trials [1]. The ability to systematically connect chemical structures to biological targets and phenotypes makes chemogenomics particularly powerful for MOA elucidation.

Identifying New Drug Targets

Chemogenomics profiling enables the identification of novel therapeutic targets through systematic analysis of chemical-biological interactions [1] [4]. In one application to antibacterial development, researchers capitalized on an existing ligand library for the enzyme murd, which participates in peptidoglycan synthesis [1]. Relying on the chemogenomics similarity principle, they mapped the murd ligand library to other members of the mur ligase family (murC, murE, murF, murA, and murG) to identify new targets for known ligands [1]. Structural and molecular docking studies revealed candidate ligands for murC and murE ligases that would be expected to function as broad-spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors since peptidoglycan synthesis is exclusive to bacteria [1].

The application of chemogenomics to target identification has been enhanced by integrating multiple perturbation methods. As noted in recent research, "the use of both chemogenomic and genetic knock-down perturbation accelerates the identification of druggable targets" [4]. In one illustrative example, integration of CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi and chemogenomic screening identified XPO1 and CDK4 as potential therapeutic targets for a rare sarcoma [4].

Elucidating Biological Pathways

Chemogenomics approaches can also help identify genes involved in specific biological pathways [1]. In one notable example, thirty years after the posttranslationally modified histidine derivative diphthamide was identified, chemogenomics was used to discover the enzyme responsible for the final step in its synthesis [1]. Researchers utilized Saccharomyces cerevisiae cofitness data, which represents the similarity of growth fitness under various conditions between different deletion strains [1]. Under the assumption that strains lacking the diphthamide synthetase gene should have high cofitness with strains lacking other diphthamide biosynthesis genes, they identified ylr143w as the strain with the highest cofitness to all other strains lacking known diphthamide biosynthesis genes [1]. Subsequent experimental assays confirmed that YLR143W was required for diphthamide synthesis and was the missing diphthamide synthetase [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemogenomic Screening Workflow

A standardized chemogenomic screening protocol involves multiple carefully orchestrated steps from assay design through data analysis. The following protocol outlines the key stages in a typical chemogenomics screening campaign:

Step 1: Assay Design and Validation

- Define screening objectives and select appropriate assay format (phenotypic or target-based)

- For phenotypic screens: Develop robust cell-based assays with relevant phenotypic endpoints

- For target-based screens: Establish purified protein or cell-based target engagement assays

- Validate assay performance parameters (Z-factor > 0.5, signal-to-background ratio > 3) [6]

Step 2: Compound Library Management

- Select appropriate chemogenomics library based on target family or diversity requirements

- Prepare compound stocks in DMSO (typically 10 mM concentration)

- Implement quality control measures to verify compound identity and purity [6]

- Reformulate compounds in appropriate assay buffer, ensuring final DMSO concentration is <1%

Step 3: High-Throughput Screening Execution

- Dispense compounds and reagents using automated liquid handling systems

- Note: Screening technology (e.g., tip-based vs. acoustic dispensing) can significantly influence experimental responses and must be consistent [6]

- Include appropriate controls on each plate (positive, negative, vehicle)

- Perform primary screen in single-point format with appropriate concentration (typically 1-10 μM)

Step 4: Hit Confirmation and Counter-Screening

- Retest primary hits in dose-response format (typically 8-12 point dilution series)

- Exclude promiscuous binders/aggregators through counter-screens

- Confirm chemical structure and purity of confirmed hits [6]

Step 5: Data Analysis and Triaging

- Normalize data using plate-based controls

- Calculate activity metrics (IC50, EC50, % inhibition/activation)

- Apply chemoinformatic analysis for structural clustering and SAR

- Prioritize hits based on potency, selectivity, and chemical attractiveness

Data Curation and Standardization Protocols

The exponential growth of chemogenomics data has highlighted the critical importance of rigorous data curation. As noted in recent literature, "there is a growing public concern about the lack of reproducibility of experimental data published in peer-reviewed scientific literature" [6]. To address this challenge, researchers have developed standardized workflows for chemical and biological data curation:

Chemical Structure Curation

- Remove incomplete or confusing records (inorganics, organometallics, counterions, biologics, mixtures)

- Perform structural cleaning (detection of valence violations, extreme bond lengths/angles)

- Standardize tautomeric forms using empirical rules to account for the most populated tautomers [6]

- Verify correctness of stereochemistry assignment

- Apply standardized representation using tools such as Molecular Checker/Standardizer (Chemaxon), RDKit, or LigPrep (Schrodinger) [6]

Bioactivity Data Standardization

- Process bioactivities for chemical duplicates: "Often, the same compound is recorded multiple times in chemogenomics depositories" [6]

- For compounds with multiple activity records for the same target, aggregate records so that one compound has only one record per target, selecting the best potency as the final aggregated value [7]

- Unify activity data with various result types to make them comparable across tests

- Standardize target identifiers using controlled vocabularies (Entrez ID, gene symbol) [7]

- Filter compounds by physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight <1000 Da, heavy atoms >12) to maintain drug-like chemical space [7]

Table 3: Standardized Activity Data Types in Chemogenomics

| Activity Type | Description | Standard Units | Typical Threshold for "Active" |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Concentration causing 50% inhibition | μM (log molar) | ≤ 10 μM [7] |

| EC50 | Concentration causing 50% response | μM (log molar) | ≤ 10 μM [7] |

| Ki | Inhibition constant | μM (log molar) | ≤ 10 μM |

| Kd | Dissociation constant | μM (log molar) | ≤ 10 μM |

| Percent Inhibition | % inhibition at fixed concentration | % | ≥ 50% at 10 μM |

| Potency | Generic potency measurement | μM (log molar) | ≤ 10 μM [7] |

Essential Research Tools and Databases

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful chemogenomics research requires access to comprehensive tools and resources. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for conducting chemogenomics studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemogenomics

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Targeted chemical libraries, Diversity-oriented synthetic libraries, Natural product collections [1] [2] | Provide chemical matter for screening against biological targets; targeted libraries enriched for specific protein families increase hit rates [1] |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, BindingDB, ExCAPE-DB [6] [7] | Public repositories of compound bioactivity data used for building predictive models and validating approaches [6] [7] |

| Structure Curation Tools | RDKit, Chemaxon JChem, AMBIT, LigPrep [6] | Software for standardizing chemical structures, handling tautomers, verifying stereochemistry, and preparing compounds for virtual screening [6] |

| Target Annotation Resources | UniProt, Gene Ontology, NCBI Entrez Gene [7] | Databases providing standardized target information, including gene symbols, protein functions, and pathway associations [7] |

| Screening Technologies | High-throughput screening assays, High-content imaging, Acoustic dispensing [6] [4] | Experimental platforms for testing compound libraries; technology selection (e.g., tip-based vs. acoustic dispensing) influences results [6] |

Major Public Chemogenomics Databases

The expansion of chemogenomics has been facilitated by the development of large-scale public databases that aggregate chemical and biological data:

ChEMBL: A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing data extracted from numerous peer-reviewed journal articles [7]. ChEMBL provides bioactivity data (binding constants, pharmacology, and ADMET information) for a significant number of drug targets.

PubChem: A public repository storing small molecules and their biological activity data, originally established as a central repository for the NIH Molecular Libraries Program [6] [7]. PubChem contains extensive screening data from high-throughput experiments.

ExCAPE-DB: An integrated large-scale dataset specifically designed to facilitate Big Data analysis in chemogenomics [7]. This resource combines data from both PubChem and ChEMBL, applying rigorous standardization to create a unified chemogenomics dataset containing over 70 million SAR data points [7].

BindingDB: A public database focusing mainly on protein-ligand interactions, providing binding affinity data for drug targets [7].

Diagram 2: Chemogenomics Data Curation Pipeline. This workflow illustrates the process of transforming raw data from multiple sources into standardized, analysis-ready chemogenomics databases through sequential curation steps.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, chemogenomics faces several important challenges that represent opportunities for future development. A primary limitation is that "the vast majority of proteins in the proteome lack selective pharmacological modulators" [4]. While chemogenomics libraries typically contain hundreds or thousands of pharmacological agents, their target coverage remains relatively narrow [4]. Even within well-studied gene families such as protein kinases, coverage is still limited, and many families such as solute carrier (SLC) transporters are poorly represented in screening libraries [4].

To address these limitations, new technologies are being developed to significantly expand chemogenomic space. Chemoproteomics has emerged as a robust platform to map small molecule-protein interactions in cells using functionalized chemical probes in conjunction with mass spectrometry analysis [4]. Exploration of the ligandable proteome using these approaches has already led to the development of new pharmacological modulators of diverse proteins [4].

The increasing volume of chemogenomics data also presents both opportunities and challenges for Big Data analysis. As noted by researchers, "Preparing a high quality data set is a vital step in realizing this goal" of building predictive models based on Big Data [7]. The heterogeneity of data sources and lack of standard annotation for biological endpoints, mode of action, and target identifiers create significant barriers to data integration [7]. Future work in chemogenomics will likely focus on developing improved standards for data annotation, more sophisticated computational models for predicting polypharmacology and off-target effects, and expanding the structural diversity of screening libraries to cover more of the chemical and target space relevant to therapeutic development.

In conclusion, chemogenomics represents a powerful integrative approach that systematically links chemical compounds to biological systems through the comprehensive analysis of chemical-biological interactions. By leveraging both experimental and computational methods, this field continues to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and bioactive compounds, ultimately enhancing the efficiency of drug discovery and our fundamental understanding of biological systems.

The evolution of DNA sequencing represents one of the most transformative progressions in modern biological science, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. From its inception with the chain termination method developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977 to today's massively parallel sequencing technologies, each advancement has dramatically increased our capacity to decipher genetic information with increasing speed, accuracy, and affordability [8] [9]. This technological revolution has served as the cornerstone for chemogenomics and modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to identify novel therapeutic targets, understand drug mechanisms, and develop personalized treatment strategies with unprecedented precision [10] [11]. The journey from reading single genes to analyzing entire genomes in a single experiment has unlocked new frontiers in understanding disease pathogenesis, drug resistance, and individual treatment responses, making genomic analysis an indispensable tool in contemporary pharmaceutical research and development [12] [10].

First-Generation Sequencing: The Sanger Method

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles

The Sanger method, also known as the chain termination method, was developed by English biochemist Frederick Sanger and his colleagues in 1977 [8] [13]. This groundbreaking work earned Sanger his second Nobel Prize in Chemistry and established the foundational technology that would dominate DNA sequencing for more than three decades [8]. The method became the workhorse of the landmark Human Genome Project, where it was used to determine the sequences of relatively small fragments of human DNA (900 base pairs or less) that were subsequently assembled into larger DNA fragments and eventually entire chromosomes [13].

The core principle of Sanger sequencing relies on the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) during DNA replication catalyzed by a DNA polymerase enzyme [8]. These modified nucleotides lack the 3'-hydroxyl group necessary for forming a phosphodiester bond with the next incoming nucleotide. When incorporated into a growing DNA strand, they terminate DNA synthesis at specific positions, generating a series of DNA fragments of varying lengths that can be separated to reveal the DNA sequence [8] [13].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The Sanger sequencing process involves a series of precise laboratory steps to determine the nucleotide sequence of DNA templates [8]:

- DNA Template Preparation: The target DNA is extracted and purified to prepare a single-stranded DNA template using methods like chemical or column-based extractions [8].

- Primer Annealing: A short, single-stranded DNA primer complementary to a known sequence on the template DNA is attached, providing a starting point for DNA synthesis [8] [13].

- DNA Polymerase Reaction: The sequencing reaction is set up containing the DNA template, primer, DNA polymerase, standard deoxynucleotides (dNTPs), and fluorescently labeled ddNTPs. Historically, four separate reactions were run, each with a small quantity of one type of ddNTP (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP), though modern capillary electrophoresis methods typically use a single reaction with differentially labeled ddNTPs [8] [13].

- Chain Termination and Fragment Generation: During DNA synthesis, ddNTPs are incorporated randomly, producing DNA fragments of different lengths, with each fragment ending with a fluorescently labeled ddNTP corresponding to one of the four nucleotide bases [8].

- Fragment Separation: The resulting DNA fragments are separated based on size using capillary electrophoresis, which offers high-resolution separation in a single reaction tube [8].

- Sequence Detection and Analysis: Fluorescent signals from the terminated fragments are detected by a laser to identify the nucleotide at each position. The sequence is determined from the order of fluorescence peaks in a chromatogram and then assembled for final analysis [8].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the Sanger sequencing method:

Key Research Reagents for Sanger Sequencing

Table 1: Essential reagents for Sanger sequencing experiments

| Reagent | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | The DNA to be sequenced; can be plasmid DNA, PCR products, or genomic DNA | Typically 1-10 ng for plasmid DNA, 5-50 ng for PCR products; should be high-purity (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0) |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes DNA synthesis; adds nucleotides to the growing DNA strand | Thermostable enzymes (e.g., Thermo Sequenase) preferred for cycle sequencing; optimized for high processivity and minimal bias |

| Primer | Short oligonucleotide that provides starting point for DNA synthesis | Typically 18-25 nucleotides; designed with Tm of 50-65°C; must be complementary to known template sequence |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotides (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP) that are the building blocks of DNA | Added at concentrations of 20-200 μM each; quality critical for low error rates |

| Fluorescent ddNTPs | Dideoxynucleotides (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, ddTTP) that terminate DNA synthesis | Each labeled with distinct fluorophore (e.g., ddATP - green, ddTTP - red, ddCTP - blue, ddGTP - yellow); added at optimized ratios to dNTPs (typically 1:100) |

| Sequencing Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment for polymerase activity | Contains Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), KCl, MgCl2; concentration optimized for specific polymerase |

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technologies

The Paradigm Shift to Massively Parallel Sequencing

The advent of next-generation sequencing in the mid-2000s marked a revolutionary departure from Sanger sequencing, introducing a fundamentally different approach based on massively parallel sequencing [9] [11]. While Sanger sequencing processes a single DNA fragment at a time, NGS technologies simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments per run, creating an unprecedented increase in data output and efficiency [14] [9]. This paradigm shift has dramatically reduced the cost and time required for genomic analyses, enabling ambitious projects like whole-genome sequencing that were previously impractical with first-generation technologies [9].

The core principle unifying NGS technologies is the ability to fragment DNA into libraries of small pieces that are sequenced simultaneously, with the resulting short reads subsequently assembled computationally against a reference genome or through de novo assembly [9] [15]. This massively parallel approach has transformed genomics from a specialized discipline focused on individual genes to a comprehensive science capable of interrogating entire genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes in a single experiment [14] [9].

Major NGS Platforms and Their Methodologies

Several NGS platforms have emerged, each with distinct biochemical approaches to parallel sequencing [9]:

Illumina Sequencing-by-Synthesis: This dominant NGS technology uses reversible dye-terminators in a cyclic approach. DNA fragments are amplified on a flow cell to create clusters, then fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated one base at a time across millions of clusters. After each incorporation cycle, the fluorescent signal is imaged, the terminator is cleaved, and the process repeats [9] [15].

Ion Torrent Semiconductor Sequencing: This unique platform detects the hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization rather than using optical detection. When a nucleotide is incorporated into a growing DNA strand, a hydrogen ion is released, causing a pH change that is detected by an ion sensor [9].

454 Pyrosequencing: This early NGS method (now discontinued) relied on detecting the release of pyrophosphate during nucleotide incorporation. The released pyrophosphate was converted to ATP, which fueled a luciferase reaction producing light proportional to the number of nucleotides incorporated [9].

SOLiD Sequencing: This platform employed a ligation-based approach using fluorescently labeled di-base probes. DNA ligase rather than polymerase was used to determine the sequence, offering potential advantages in accuracy but limited by shorter read lengths [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis, representing the most widely used NGS technology:

Key Research Reagents for NGS Experiments

Table 2: Essential reagents for next-generation sequencing experiments

| Reagent | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kit | Fragments DNA and adds platform-specific adapters | Contains fragmentation enzymes/beads, ligase, adapters with barcodes; enables sample multiplexing |

| Cluster Generation Reagents | Amplifies single DNA molecules on flow cell to create sequencing features | Includes flow cell with grafted oligonucleotides, polymerase, nucleotides for bridge amplification |

| Sequencing Kit | Provides enzymes and nucleotides for sequencing-by-synthesis | Contains DNA polymerase, fluorescently-labeled reversible terminators; formulation specific to platform (Illumina, etc.) |

| Flow Cell | Solid surface that hosts immobilized DNA clusters for sequencing | Glass slide with lawn of oligonucleotides; patterned or non-patterned; determines total data output |

| Index/Barcode Adapters | Enable sample multiplexing by adding unique sequences to each library | 6-10 basepair unique molecular identifiers; allows pooling of hundreds of samples in one run |

| Cleanup Beads | Size selection and purification of libraries between steps | SPRI or AMPure magnetic beads with specific size cutoffs; remove primers, adapters, and small fragments |

Comparative Analysis: Sanger Sequencing vs. NGS

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

The selection between Sanger sequencing and NGS depends heavily on project requirements, with each technology offering distinct advantages for specific applications [14] [15]. The following table provides a detailed comparison of key performance metrics and technical specifications:

Table 3: Comprehensive comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS technologies

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination using ddNTPs [15] [13] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis, ligation, or ion detection) [15] |

| Throughput | Low throughput; processes DNA fragments one at a time [14] | Extremely high throughput; sequences millions to billions of fragments simultaneously [14] [15] |

| Read Length | Long reads: 500-1,000 bp [15] [13] | Short reads: 50-300 bp (Illumina); Long reads: 10,000-30,000+ bp (PacBio, Nanopore) [9] [15] |

| Accuracy | Very high per-base accuracy (>99.99%); "gold standard" for validation [15] [13] | High overall accuracy achieved through depth of coverage; single-read accuracy lower than Sanger [15] |

| Cost Efficiency | Cost-effective for single genes or small targets (1-20 amplicons) [14] | Lower cost per base for large projects; higher capital and reagent costs [14] [15] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Limited sensitivity (~15-20% allele frequency) [14] | High sensitivity (down to 1% or lower for rare variants) [14] |

| Applications | Single gene analysis, mutation confirmation, plasmid verification [14] [15] | Whole genomes, exomes, transcriptomes, epigenomics, metagenomics [14] [9] [15] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited to no multiplexing capability | High-level multiplexing with barcodes (hundreds of samples per run) [14] |

| Turnaround Time | Fast for small numbers of targets | Faster for high sample volumes; requires longer library prep and analysis [14] |

| Bioinformatics Requirements | Minimal; basic sequence analysis tools [15] | Extensive; requires sophisticated pipelines for alignment, variant calling, data storage [15] |

| Variant Discovery Power | Limited to known or targeted variants | High discovery power for novel variants, structural variants [14] |

Application-Specific Considerations for Technology Selection

The optimal choice between Sanger and NGS technologies is primarily dictated by the specific research question and experimental design [14] [15]:

Sanger sequencing remains the preferred choice for:

- Targeted confirmation of variants identified through NGS screening [8] [15]

- Simple variant screening in known loci, such as specific disease-associated SNPs or small indels [15]

- Sequencing of isolated PCR products for microbial identification or genotyping [15]

- Plasmid or clone validation in molecular biology workflows [15]

- Clinical diagnostics of single genes with high accuracy requirements [8]

NGS provides superior capabilities for:

- Whole-genome sequencing for comprehensive variant discovery [15]

- Whole-exome sequencing for identifying causative mutations in Mendelian diseases [15]

- Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq) for quantitative gene expression analysis [9] [15]

- Epigenetics including DNA methylation studies and ChIP-Seq [9] [15]

- Clinical oncology with tumor sequencing, liquid biopsies, and minimal residual disease monitoring [15] [10]

- Metagenomics and microbiome analysis of complex microbial communities [9]

- Pharmacogenomics studies analyzing drug response variants [11]

The following case study illustrates how both technologies can be complementary in advanced research settings:

Case Study: Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of Historical Remains

A 2025 study comparing Sanger and NGS for mitochondrial DNA analysis of WWII skeletal remains demonstrates the complementary strengths of both technologies [16]. Researchers analyzed degraded DNA from mass grave victims using identical extraction methods to minimize pre-sequencing variability. The study found that NGS demonstrated higher sensitivity in detecting low-level heteroplasmies (mixed mitochondrial populations) that were undetectable by Sanger sequencing, particularly in length heteroplasmy in the hypervariable regions [16]. However, the study also noted that certain NGS variants had to be disregarded due to platform-specific errors, highlighting how Sanger sequencing maintains value as a validation tool even when NGS provides greater discovery power [16].

NGS Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

Transformative Impact on Target Identification and Validation

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionized chemogenomics by enabling comprehensive analysis of the complex relationships between genetic variations, biological systems, and chemical compounds [10]. In target identification, NGS facilitates rapid whole-genome sequencing of individuals with and without specific diseases to identify potential therapeutic targets through association studies [10]. For example, a study published in Nature investigated 10 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in over 100,000 subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis (RA), identifying 42 new risk indicators for the disease [10]. This research demonstrated that many of these risk indicators were already targeted by existing RA drugs, while also revealing three cancer drugs that could potentially be repurposed for RA treatment [10].

In target validation, NGS technologies enable researchers to understand DNA-protein interactions, analyze DNA methylation patterns, and conduct comprehensive RNA sequencing to confirm the functional relevance of potential drug targets [10]. The massively parallel nature of NGS allows for the simultaneous investigation of multiple targets and pathways, significantly accelerating the early stages of drug discovery [10].

Overcoming Drug Resistance and Enabling Personalized Oncology

NGS has become an indispensable tool in oncology drug development, particularly in addressing the challenge of drug resistance that accounts for approximately 90% of chemotherapy failures [10]. By sequencing tumors before, during, and after treatment, researchers can identify biomarkers associated with resistance and develop strategies to overcome these mechanisms [10].

The development of precision cancer treatments represents one of the most significant clinical applications of NGS. In a clinical trial for bladder cancer, researchers discovered that tumors with a specific TSC1 mutation showed significantly better response to the drug everolimus, with improved time-to-recurrence, while patients without this mutation showed minimal benefit [10]. This finding illustrates the power of NGS in identifying patient subgroups most likely to respond to specific therapies, even when those therapies do not show efficacy in broader patient populations [10]. Such insights are transforming clinical trial design and drug development strategies, moving away from one-size-fits-all approaches toward more targeted, effective treatments.

Pharmacogenomics and Drug Safety Assessment

Pharmacogenomics applications of NGS enable researchers to understand how genetic variations influence individual responses to medications, optimizing both drug efficacy and safety profiles [11]. By sequencing genes involved in drug metabolism, transport, and targets, researchers can identify genetic markers that predict adverse drug reactions or suboptimal responses [11]. This approach allows for the development of companion diagnostics that guide treatment decisions based on a patient's genetic makeup, maximizing therapeutic benefits while minimizing risks [11].

The integration of NGS in safety assessment also extends to toxicogenomics, where gene expression profiling using RNA-Seq can identify potential toxicity mechanisms early in drug development. This application enables more informed go/no-go decisions in the pipeline and helps researchers design safer chemical entities by understanding their effects on gene expression networks and pathways [10].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Third-Generation Sequencing and Multi-Omics Integration

The sequencing landscape continues to evolve with the emergence and refinement of third-generation sequencing technologies that address limitations of short-read NGS platforms [9] [11]. These technologies, including Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing from PacBio and nanopore sequencing from Oxford Nanopore Technologies, offer significantly longer read lengths (typically 10,000-30,000 base pairs) that enable more accurate genome assembly, resolution of complex repetitive regions, and detection of large structural variations [9] [11].

The year 2025 is witnessing a paradigm shift toward multi-omics integration, combining genomic data with transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic information from the same sample [12] [17]. This comprehensive approach provides unprecedented insights into biological systems by linking genetic variations with functional consequences across multiple molecular layers [12]. For drug discovery, multi-omics enables more accurate target identification by revealing how genetic variants influence gene expression, protein function, and metabolic pathways in specific disease states [17].

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Bioinformatics

The massive datasets generated by NGS and multi-omics approaches have created an urgent need for advanced computational tools, driving the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into genomic analysis pipelines [12] [17]. AI algorithms are transforming variant calling, with tools like Google's DeepVariant demonstrating higher accuracy than traditional methods [12]. Machine learning models are also being deployed to analyze polygenic risk scores for complex diseases, identify novel drug targets, and predict treatment responses based on multi-omics profiles [12].

The future of genomic data analysis will increasingly rely on cloud computing platforms to manage the staggering volume of sequencing data, which often exceeds terabytes per project [12]. Cloud-based solutions provide scalable infrastructure for data storage, processing, and analysis while enabling global collaboration among researchers [12]. These platforms also address critical data security requirements through compliance with regulatory frameworks like HIPAA and GDPR, which is essential for handling sensitive genomic information [12].

Spatial Transcriptomics and Single-Cell Genomics

The year 2025 is poised to be a breakthrough period for spatial biology, with new sequencing-based technologies enabling direct genomic analysis of cells within their native tissue context [17]. This approach preserves critical spatial information about cellular interactions and tissue microenvironments that is lost in conventional bulk sequencing methods [17]. For drug discovery, spatial transcriptomics provides unprecedented insights into complex disease mechanisms, cellular heterogeneity in tumors, and the distribution of drug targets within tissues [17].

Single-cell genomics represents another transformative frontier, enabling researchers to analyze genetic and gene expression heterogeneity at the individual cell level [12]. This technology is particularly valuable for understanding tumor evolution, identifying resistant subclones in cancer, mapping cellular differentiation during development, and unraveling the complex cellular architecture of neurological tissues [12]. The combination of single-cell analysis with spatial context is creating powerful new frameworks for understanding disease biology and developing more effective therapeutics [17].

The evolution from Sanger sequencing to next-generation technologies represents one of the most significant technological transformations in modern science, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of biological research and drug discovery. While Sanger sequencing maintains its vital role as a gold standard for validation of specific variants and small-scale sequencing projects, NGS has unlocked unprecedented capabilities for comprehensive genomic analysis at scale [14] [15] [13]. The ongoing advancements in third-generation sequencing, multi-omics integration, artificial intelligence, and spatial genomics promise to further accelerate this transformation, enabling increasingly sophisticated applications in personalized medicine and targeted drug development [12] [17] [11].

For researchers in chemogenomics and drug discovery, understanding the technical capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each sequencing technology is essential for designing effective research strategies. The complementary strengths of established and emerging sequencing platforms provide a powerful toolkit for addressing the complex challenges of modern therapeutic development, from initial target identification to clinical implementation of precision medicine approaches [10] [11]. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward greater accessibility, affordability, and integration, their role in illuminating the genetic underpinnings of disease and enabling more effective, personalized treatments will undoubtedly expand, solidifying genomics as an indispensable foundation for 21st-century biomedical science.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, providing unparalleled capabilities for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [9]. This transformative technology has rapidly advanced diverse domains, from clinical diagnostics to fundamental biological research, by enabling the rapid sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [9]. In the specific context of chemogenomics and drug discovery research, NGS technologies provide critical insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications that underlie disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses [9] [12]. The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of genomics research, facilitating studies on rare genetic diseases, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, infectious diseases, and population genetics [9]. This technical guide examines the three core NGS platforms—Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)—focusing on their underlying technologies, performance characteristics, and applications in chemogenomics and drug development research.

Technology Platforms: Core Principles and Specifications

Illumina Sequencing-by-Synthesis

Illumina's technology utilizes a sequencing-by-synthesis approach with reversible dye-terminators [9]. The process begins with DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation, followed by bridge amplification on a flow cell that creates clusters of identical DNA fragments [18]. During sequencing cycles, fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are incorporated, with imaging after each incorporation detecting the specific base added [9]. The termination is reversible, allowing successive cycles to build up the sequence read. This technology produces short reads typically ranging from 36-300 base pairs [9] but offers exceptional accuracy with error rates below 1% [9]. Illumina's recently introduced NovaSeq X has redefined high-throughput sequencing, offering unmatched speed and data output for large-scale projects [12]. For complex genomic regions, Illumina offers "mapped read" technology that maintains the link between original long DNA templates and resulting short sequencing reads using proximity information from clusters in neighboring nanowells, enabling enhanced detection of structural variants and improved mapping in low-complexity regions [18].

Pacific Biosciences Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing

PacBio's SMRT technology employs a fundamentally different approach based on real-time observation of DNA synthesis [9]. The core component is the SMRT Cell, which contains millions of microscopic wells called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [9]. Individual DNA polymerase molecules are immobilized at the bottom of each ZMW with a single DNA template. As nucleotides are incorporated, each nucleotide carries a fluorescent label that is detected in real-time [9]. The key innovation is that the ZMWs confine observation to the very bottom of the well, allowing detection of nucleotide incorporation events against background fluorescence. PacBio's HiFi (High Fidelity) sequencing employs circular consensus sequencing (CCS), where the same DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly, generating multiple subreads that are consolidated into one highly accurate read with precision exceeding 99.9% [19]. PacBio offers both the large-scale Revio system, delivering 120 Gb per SMRT Cell, and the benchtop Vega system, delivering 60 Gb per SMRT Cell [19]. The platform also provides the Onso system for short-read sequencing with exceptional accuracy, leveraging sequencing-by-binding (SBB) chemistry for a 15x improvement in error rates compared to traditional sequencing-by-synthesis [19].

Oxford Nanopore Electrical Signal-Based Sequencing

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) employs a revolutionary approach that detects changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [20]. The technology involves applying a voltage across a membrane containing nanopores, which causes DNA molecules to unwind and pass through the pores [20]. As each nucleotide passes through the nanopore, it creates a characteristic disruption in ionic current that can be decoded to determine the DNA sequence [20]. Unlike other technologies, nanopore sequencing does not require DNA amplification or synthesis, enabling direct sequencing of native DNA or RNA molecules. ONT devices range from the portable MinION to the high-throughput PromethION and GridION platforms [20]. Recent advancements including R10.4 flow cells with dual reader heads and updated chemistries have significantly improved raw read accuracy to over 99% (Q20) [20] [21]. A distinctive advantage of nanopore technology is its capacity for real-time sequencing and ultra-long reads, with sequences exceeding 100 kilobases routinely achieved, allowing complete coverage of expansive genomic regions in single reads [20].

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of Major NGS Platforms

| Parameter | Illumina | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Chemistry | Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators [9] | Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing with circular consensus [9] [19] | Nanopore electrical signal detection [20] |

| Typical Read Length | 36-300 bp [9] | 10,000-25,000 bp [9] | 10,000-30,000+ bp [9] [20] |

| Accuracy | <1% error rate [9] | >99.9% (Q27) [22] [19] | >99% raw read accuracy with latest chemistries (Q20+) [20] |

| Throughput Range | Scalable from focused panels to terabases per run [18] | Revio: 120 Gb/SMRT Cell; Vega: 60 Gb/SMRT Cell [19] | MinION: ~15-30 Gb; PromethION: terabases per run [20] |

| Key Applications in Chemogenomics | Targeted sequencing, transcriptomics, variant detection [9] [12] | Full-length transcript sequencing, structural variant detection, epigenetic modification detection [19] [23] | Real-time pathogen surveillance, direct RNA sequencing, complete plasmid assembly [20] [23] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Comparative Performance in Microbiome Profiling Studies

Recent comparative studies have evaluated the performance of Illumina, PacBio, and ONT platforms for 16S rRNA gene sequencing in microbiome research, a critical application in chemogenomics for understanding drug-microbiome interactions. A 2025 study comparing these platforms for rabbit gut microbiota analysis demonstrated significant differences in species-level resolution [22]. The research employed DNA from four rabbit does' soft feces, sequenced using Illumina MiSeq for the V3-V4 regions, and full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using PacBio HiFi and ONT MinION [22]. Bioinformatic processing utilized the DADA2 pipeline for Illumina and PacBio sequences, while ONT sequences were analyzed using Spaghetti, a custom pipeline employing an OTU-based clustering approach due to the technology's higher error rate and lack of internal redundancy [22].

Another 2025 study evaluated these platforms for soil microbiome profiling, using three distinct soil types with standardized bioinformatics pipelines tailored to each platform [21]. The experimental design included sequencing depth normalization across platforms (10,000, 20,000, 25,000, and 35,000 reads per sample) to ensure comparability [21]. For PacBio sequencing, the full-length 16S rRNA gene was amplified from 5 ng of genomic DNA using universal primers (27F and 1492R) tagged with sample-specific barcodes over 30 PCR cycles [21]. ONT sequencing employed similar primers with library preparation using the Native Barcoding Kit, while Illumina targeted the V4 and V3-V4 regions following standard protocols [21].

Diagram 1: Comparative NGS workflow for 16S rRNA sequencing

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for NGS Workflows

| Reagent/Kits | Platform | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) | All platforms [22] | Environmental DNA extraction | Efficient inhibitor removal for challenging samples |

| 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) | Illumina [22] | Library preparation for 16S sequencing | Optimized for V3-V4 amplification with minimal bias |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | PacBio [22] [21] | Library preparation for SMRT sequencing | Creates SMRTbell templates for circular consensus sequencing |

| 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-RAB204/16S024) | Oxford Nanopore [22] | 16S amplicon sequencing with barcoding | Enables multiplexing of full-length 16S amplicons |

| Native Barcoding Kit 96 (SQK-NBD109) | Oxford Nanopore [21] | Multiplexed library preparation | Allows barcoding of up to 96 samples for nanopore sequencing |

| KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase | PacBio [22] | High-fidelity PCR amplification | Provides high accuracy for full-length 16S amplification |

Performance Comparison and Applications

Taxonomic Resolution in Microbial Community Analysis

The 2025 comparative study of rabbit gut microbiota revealed significant differences in taxonomic resolution across platforms [22]. At the species level, ONT exhibited the highest resolution (76%), followed by PacBio (63%), with Illumina showing the lowest resolution (48%) [22]. However, the study noted a critical limitation across all platforms: at the species level, most classified sequences were labeled as "Uncultured_bacterium," indicating persistent challenges in reference database completeness rather than purely technological limitations [22].

The soil microbiome study demonstrated that ONT and PacBio provided comparable bacterial diversity assessments, with PacBio showing slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa [21]. Despite differences in sequencing accuracy, ONT produced results that closely matched PacBio, suggesting that ONT's inherent sequencing errors do not significantly affect the interpretation of well-represented taxa [21]. Both platforms enabled clear clustering of samples based on soil type, whereas Illumina's V4 region alone failed to demonstrate such clustering (p = 0.79) [21].

Table 3: Performance Metrics from Comparative Microbiome Studies

| Metric | Illumina (V3-V4) | PacBio (Full-Length) | ONT (Full-Length) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Resolution | 48% [22] | 63% [22] | 76% [22] |

| Genus-Level Resolution | 80% [22] | 85% [22] | 91% [22] |

| Average Read Length | 442 ± 5 bp [22] | 1,453 ± 25 bp [22] | 1,412 ± 69 bp [22] |

| Reads After QC (per sample) | 30,184 ± 1,146 [22] | 41,326 ± 6,174 [22] | 630,029 ± 92,449 [22] |

| Differential Abundance Detection | Limited by short reads | Enhanced by long reads | Enhanced by long reads |

| Soil-Type Clustering | Not achieved with V4 region alone (p=0.79) [21] | Clear clustering observed [21] | Clear clustering observed [21] |

Applications in Antimicrobial Resistance and Infectious Disease

Long-read sequencing technologies have demonstrated particular utility in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, a crucial area of chemogenomics. A 2025 study utilizing PacBio sequencing for hospital surveillance of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial isolates revealed that "more than a decade of bacterial genomic surveillance missed at least one-third of all AMR transmission events due to plasmids" [23]. The analysis uncovered 1,539 plasmids in total, enabling researchers to identify intra-host and patient-to-patient transmissions of AMR plasmids that were previously undetectable with short-read technologies [23].

Nanopore sequencing has revolutionized AMR research by enabling complete bacterial genome construction, rapid resistance gene detection, and analysis of multidrug resistance genetic structure dynamics [20]. The technology's long reads can span entire mobile genetic elements, allowing precise characterization of the genetic contexts of antimicrobial resistance genes in both cultured bacteria and complex microbiota [20]. The portability and real-time sequencing capabilities of devices like MinION make them ideal for point-of-care detection and rapid intervention in hospital outbreaks [20].

Diagram 2: Long-read sequencing applications in AMR research

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The NGS market continues to evolve rapidly, with projections estimating growth from $12.13 billion in 2023 to approximately $23.55 billion by 2029, representing a compound annual growth rate of about 13.2 percent [24]. This growth is fueled by strategic partnerships and automation that streamline workflows and enhance reproducibility [24]. Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools like Google's DeepVariant has improved variant calling accuracy, enabling more precise identification of genetic variants [12].

Multi-omics approaches that combine genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics provide a more comprehensive view of biological systems [12]. PacBio's HiFi sequencing now enables simultaneous generation of phased genomes, methylation profiling, and full-length RNA isoforms in a single workflow [23]. Similarly, Oxford Nanopore's platform provides multiomic capabilities including native methylation detection, structural variant analysis, haplotyping, and direct RNA sequencing on a single scalable platform [25].

Single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics are advancing precision medicine applications by revealing cellular heterogeneity within tissues [12]. In cancer research, these approaches help identify resistant subclones within tumors, while in neurodegenerative diseases, they enable mapping of gene expression patterns in affected brain tissues [12]. The Human Pangenome Reference Consortium continues to expand diversity in genomic references, with the second data release featuring high-quality phased genomes from over 200 individuals, nearly a fivefold increase over the first release [23].

Cloud computing platforms have become essential for managing the enormous volumes of data generated by NGS technologies, providing scalable infrastructure for storage, processing, and analysis while ensuring compliance with regulatory frameworks such as HIPAA and GDPR [12]. As these technologies continue to converge, they promise to further accelerate drug discovery and personalized medicine approaches in chemogenomics.

The convergence of personalized medicine, the growing chronic disease burden, and strategic government funding is creating a transformative paradigm in biomedical research and drug development. This whitepaper examines these key market drivers within the context of modern chemogenomics and next-generation sequencing (NGS) applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these dynamics is crucial for navigating the current landscape and leveraging emerging opportunities. Personalized medicine represents a fundamental shift from the traditional "one-size-fits-all" approach to healthcare, instead tailoring prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies to individual patient characteristics based on genetic, genomic, and environmental information [26]. This approach is gaining significant traction driven by technological advancements, compelling market needs, and supportive regulatory and funding environments.

Market Drivers and Quantitative Analysis

Personalized Medicine Market Growth

The personalized medicine market is experiencing robust global expansion, fueled by advances in genomic technologies, increasing demand for targeted therapies, and supportive policy initiatives. The market projections and growth trends are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Personalized Medicine Market Projections

| Region | 2024/2025 Market Size | 2033/2034 Projected Market Size | CAGR | Primary Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | $169.56 billion (2024) [26] | $307.04 billion (2033) [26] | 6.82% [26] | Advances in NGS, government policy support, rising chronic disease prevalence [26] |

| Global | $572.93 billion (2024) [27] | $1.264 trillion (2034) [27] | 8.24% [27] | Technological innovations, rising healthcare demands, increasing investment [27] |

| North America | 41-45% market share (2023) [27] [28] | Maintained dominance | ~8% [28] | Advanced healthcare infrastructure, regulatory support, substantial institutional funding [27] [28] |

Key growth segments within personalized medicine include personalized nutrition and wellness, which held the major market share in 2024, and personalized medicine therapeutics, which is projected to be the fastest-growing segment [27]. The personalized genomics segment is forecasted to expand from $12.57 billion in 2025 to over $52 billion by 2034 at a remarkable CAGR of 17.2% [28].

Chronic Disease Burden

Chronic diseases represent a significant driver for personalized medicine development, creating both an urgent need for more effective treatments and a substantial market opportunity. The economic and prevalence data for major chronic conditions are summarized below.

Table 2: Chronic Disease Prevalence and Economic Impact

| Disease Category | Prevalence in US | Annual US Deaths | Economic Impact | Projected Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Disease | 523 million people worldwide (2020) [29] | 934,509 (2021) [29] | $233.3 billion in healthcare, $184.6B lost productivity [30] | ~$2 trillion by 2050 (US) [30] |

| Cancer | 1.8 million new diagnoses annually [30] | 600,000+ [30] | $180 billion (2015) [29] | $246 billion by 2030 (US) [29] |

| Diabetes | 38 million Americans [30] | 103,000 (2021) [29] | $413 billion (2022) [30] | $966 billion global health expenditure (2021) [29] |

| Alzheimer's & Dementia | 6.7 million Americans 65+ [30] | 7th leading cause of death [29] | $345 billion (2023) [29] | Nearly $1 trillion by 2050 [30] |

Chronic diseases account for 90% of the nation's $4.9 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures, with interventions to prevent and manage these conditions offering significant health and economic benefits [30]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the chronic disease burden, as people with conditions like diabetes and heart disease faced elevated risks for severe morbidity and mortality, while many others delayed or avoided preventive care [29].

Technological Foundations: Chemogenomics and NGS

Chemogenomics in Target Discovery

Chemogenomics represents an innovative approach in chemical biology that synergizes combinatorial chemistry with genomic and proteomic biology to systematically study biological system responses to compound libraries [2]. This methodology is particularly valuable for deconvoluting biological mechanisms and identifying therapeutically relevant targets from phenotypic screens.

Table 3: Chemogenomics Experimental Components

| Component | Description | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemogenomic Library | A collection of chemically diverse compounds annotated for biological activity [2] | Target identification and validation, phenotypic screening, mechanism deconvolution [2] |

| Perturbation Strategies | Small molecules used in place of mutations to temporally and spatially disrupt cellular pathways [4] | Pathway analysis, functional genomics, systems pharmacology [4] |

| Multi-dimensional Data Sets | Combining compound mixtures with phenotypic assays and functional genomic data [4] | Correlation of chemical and biological space, predictive modeling [4] |

The chemogenomics workflow typically involves several critical stages: library design and compound selection, high-throughput phenotypic screening, target deconvolution through chemoproteomic approaches, and validation using orthogonal genetic and chemical tools [2]. A key challenge in chemogenomics is that the vast majority of proteins in the proteome lack selective pharmacological modulators, necessitating technologies that significantly expand chemogenomic space [4].

Next-Generation Sequencing Applications

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionized personalized medicine by providing comprehensive genetic data that informs multiple stages of the drug development pipeline. The applications of NGS span from initial target discovery to clinical trial optimization and companion diagnostic development.

Table 4: NGS Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

| Drug Development Stage | NGS Application | Specific Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Association of genetic variants with disease phenotypes [31] | Population-wide studies, electronic health record analysis [31] |

| Target Validation | Confirming target relevance through loss-of-function mutations [31] | Phenotype studies combined with mutation detection [31] |

| Patient Stratification | Selection of appropriate patients for clinical trials [31] | Genetic profiling, companion diagnostic development [32] |

| Pharmacogenomics | Understanding drug absorption, metabolism, and dosing variations [31] | Variant analysis in genes affecting drug metabolism [31] |

Technological advancements in NGS continue to enhance its utility in drug discovery. Long-read sequencing improves resolution of complex structural variants, while single-cell sequencing provides insights into cellular heterogeneity [31]. Spatial transcriptomics, liquid biopsy sequencing, and epigenome sequencing represent additional innovative techniques advancing oncology and other therapeutic areas [31].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Chemogenomic Screening Protocol

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for target identification using chemogenomic libraries and NGS technologies.

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemogenomic compound library (e.g., 500-10,000 annotated compounds)

- Cell line models relevant to disease pathology

- NGS library preparation kits

- Cell culture reagents and assay plates

- RNA/DNA extraction kits

- CRISPR-Cas9 components for validation

Procedure:

- Library Design and Compound Selection: Curate a diverse collection of compounds with known target annotations, focusing on pharmacologically relevant gene families [2].

- High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening: Plate cells in 384-well format and treat with compound libraries at multiple concentrations. Incubate for 72-144 hours depending on assay readout [4].

- Multi-Parametric Readout Acquisition: Implement high-content imaging, transcriptomic profiling, and cell viability assays to capture comprehensive phenotypic responses.

- NGS Sample Preparation: Extract RNA/DNA from compound-treated cells following manufacturer protocols. Prepare sequencing libraries using compatible kits [32].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Perform whole transcriptome sequencing on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million reads per sample). Process data through bioinformatic pipeline for variant calling, differential expression, and pathway analysis [31].

- Target Validation: Integrate chemogenomic and CRISPR screening data to identify high-confidence targets. Confirm using orthogonal approaches including siRNA and small-molecule probes [4].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For low hit rates in phenotypic screens, consider expanding chemical diversity and increasing screening concentrations

- When NGS data quality is suboptimal, check RNA integrity numbers (RIN >8.0 recommended) and library fragment size distribution

- To address false positives in target identification, implement counter-screens and use multiple chemogenomic libraries

NGS-Guided Patient Stratification Protocol

This methodology enables precision oncology approaches through comprehensive genomic profiling.

Materials and Reagents:

- TruSight Oncology 500 assay or similar comprehensive profiling panel

- FFPE tissue sections or blood samples for liquid biopsy

- DNA/RNA extraction kits optimized for low input samples

- NGS library preparation reagents

- Bioinformatics software for variant interpretation

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing: Obtain tumor tissue (FFPE or fresh frozen) or blood samples (for ctDNA analysis). Extract DNA and RNA using validated methods [32].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries according to manufacturer instructions. For liquid biopsy samples, use specialized kits designed for low variant allele fractions [32].

- Variant Calling and Annotation: Process sequencing data through bioinformatics pipeline to identify single nucleotide variants, indels, copy number alterations, and gene fusions. Annotate variants for clinical significance [31].

- Interpretation and Reporting: Classify variants according to AMP/ASCO/CAP guidelines (Tier I-IV). Generate comprehensive molecular report with therapeutic implications [32].

- Clinical Decision Support: Present findings in molecular tumor board for therapeutic recommendation. Match identified alterations to targeted therapy options [28].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Chemogenomic Screening Workflow

Diagram 1: Chemogenomic Screening

NGS in Drug Discovery Pipeline

Diagram 2: NGS Drug Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics and NGS

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Focused Chemogenomic Libraries | Collections of compounds annotated for specific target families [2] | Target identification, phenotypic screening [2] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Prepare DNA/RNA samples for sequencing [32] | Whole genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis [32] |

| Companion Diagnostic Assays | Validate biomarkers and identify patient subgroups [32] | Patient stratification, treatment selection [32] |

| Organoid Culture Systems | Patient-derived 3D models for drug testing [31] | Drug repurposing, personalized treatment planning [31] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | Gene editing for target validation [28] | Functional genomics, mechanistic studies [28] |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Analyze and interpret NGS data [31] | Variant calling, pathway analysis, predictive modeling [31] |

The convergence of personalized medicine, chronic disease burden, and government funding represents a powerful catalyst for innovation in drug discovery and development. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging chemogenomics approaches and NGS technologies is essential for translating this potential into improved patient outcomes. The ongoing advancements in AI and machine learning, single-cell technologies, and spatial omics will further accelerate progress in this field. To fully realize the promise of personalized medicine, continued investment in cross-sector collaboration, education and training, and supportive regulatory frameworks will be critical. By strategically addressing these areas, the research community can drive the next wave of innovation in personalized medicine and deliver lasting value to patients and healthcare systems worldwide.

Chemogenomics, the systematic study of the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems, represents a powerful paradigm in modern drug discovery. The advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed this field, providing unprecedented insights into the complex relationships between small molecules, cellular targets, and genomic responses. This whitepaper examines the synergistic potential between NGS and chemogenomics, detailing how massively parallel sequencing technologies accelerate target identification, validation, mechanism-of-action studies, and patient stratification. By enabling comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic profiling, NGS provides the multidimensional data necessary to decode the complex mechanisms underlying drug response and resistance, ultimately advancing the development of targeted therapeutics and personalized medicine approaches.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS), also known as massively parallel sequencing, is a transformative technology that rapidly determines the sequences of millions of DNA or RNA fragments simultaneously [31]. This high-throughput capability, combined with dramatically reduced costs compared to traditional Sanger sequencing, has revolutionized genomics research and its applications in drug discovery [33]. The core innovation of NGS lies in its ability to generate vast amounts of genetic data in a single run, providing researchers with comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications [9].

Chemogenomics represents a systematic approach to understanding the complex interactions between small molecule compounds and biological systems, particularly focusing on how chemical perturbations affect cellular pathways and phenotypes. The integration of NGS into chemogenomics has created a powerful synergy that enhances every stage of the drug discovery pipeline. By providing a comprehensive view of the genomic landscape, NGS enables researchers to identify novel drug targets, validate their biological relevance, understand mechanisms of drug action and resistance, and ultimately develop more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies [31] [10].

The evolution from first-generation Sanger sequencing to modern NGS platforms has been remarkable. While the Human Genome Project took 13 years and cost nearly $3 billion using Sanger sequencing, current NGS technologies can sequence an entire human genome in hours for under $1,000 [33]. This dramatic reduction in cost and time has democratized genomic research, making large-scale chemogenomic studies feasible and enabling the integration of genomic approaches throughout the drug discovery process.

NGS Technologies and Platforms for Chemogenomic Applications

The NGS landscape encompasses multiple technology platforms, each with distinct strengths suited to different chemogenomic applications. Understanding these platforms is essential for selecting the appropriate sequencing approach for specific research questions in drug discovery.

Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

Short-read sequencing technologies from Illumina dominate the NGS landscape due to their high accuracy and throughput. These platforms utilize sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry with reversible dye-terminators, enabling parallel sequencing of millions of clusters on a flow cell [9]. The Illumina platform achieves over 99% base call accuracy, making it ideal for applications requiring precise variant detection, such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) identification in pharmacogenomic studies [34]. Common Illumina systems include the NovaSeq 6000 and NovaSeq X series, with the latter capable of sequencing more than 20,000 whole genomes annually at approximately $200 per genome [35]. This platform excels in whole-genome sequencing, whole-exome sequencing, transcriptomics, and targeted sequencing panels for comprehensive genomic profiling in chemogenomics.

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

Long-read sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) address the limitations of short-read sequencing by generating reads that span thousands to millions of base pairs [33]. PacBio's Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing employs zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) to monitor DNA polymerase activity in real-time, producing reads with an average length of 10,000-25,000 base pairs [9]. This technology is particularly valuable for resolving complex genomic regions, detecting structural variations, and characterizing full-length transcript isoforms in response to compound treatment.

Oxford Nanopore sequencing measures changes in electrical current as DNA or RNA molecules pass through protein nanopores, enabling real-time sequencing with read lengths that can exceed 2 megabases [12]. The portability of certain Nanopore devices (MinION, GridION, PromethION) facilitates direct, real-time sequencing in various environments. While long-read technologies historically had higher error rates (5-20%) compared to short-read platforms, recent improvements have significantly enhanced their accuracy, making them indispensable tools for comprehensive genomic characterization in chemogenomics [34].

Emerging Sequencing Methodologies

The NGS field continues to evolve with emerging methodologies that expand chemogenomic applications. Single-cell sequencing enables gene expression profiling at the level of individual cells, providing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity within complex biological systems [31]. This is particularly valuable in cancer research, where tumor subpopulations may exhibit differential responses to therapeutic compounds. Spatial transcriptomics preserves the spatial context of gene expression within tissues, allowing researchers to map compound effects within the architectural framework of organs or tumors [12]. Additionally, epigenome sequencing techniques facilitate the study of DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and protein-DNA interactions, revealing how compound treatments influence the epigenetic landscape and gene regulation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms for Chemogenomics Applications

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Key Applications in Chemogenomics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-Synthesis | 50-300 bp | Variant detection, expression profiling, target validation | High accuracy ( >99%), high throughput | Short reads struggle with repetitive regions |

| PacBio | Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | 10,000-25,000 bp | Structural variant detection, complex region resolution, isoform sequencing | Long reads, direct epigenetic modification detection | Higher cost, lower throughput than Illumina |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | 1 kb->2 Mb | Real-time sequencing, structural variants, metagenomic analysis | Ultra-long reads, portability, direct RNA sequencing | Higher error rate, requires specific analysis approaches |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp | Targeted sequencing, pharmacogenomic screening | Fast run times, simple workflow | Homopolymer errors, lower throughput |

NGS in Target Identification and Validation