Chemogenomic Libraries vs. Chemical Probes: A Strategic Guide for Phenotypic Screening in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic application of chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes in phenotypic screening.

Chemogenomic Libraries vs. Chemical Probes: A Strategic Guide for Phenotypic Screening in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic application of chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes in phenotypic screening. It explores the foundational definitions, distinct roles, and operational criteria for each tool. The content covers methodological integration with advanced disease models and omics technologies, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes a rigorous framework for experimental validation and tool selection. By synthesizing current best practices and future directions, this guide aims to enhance the effectiveness of phenotypic screening campaigns for identifying novel therapeutic targets and mechanisms.

Defining the Tools: Chemical Probes and Chemogenomic Libraries in Phenotypic Discovery

What Are Chemical Probes? Defining Potency, Selectivity, and Cellular Activity Criteria

Chemical probes are highly characterized small molecules that represent essential tools for investigating the function of specific proteins in biochemical assays, cellular models, and complex organisms [1]. These reagents allow researchers to perform pharmacological perturbation studies with temporal control and dose-dependent effects, enabling the dissection of complex biological processes and the validation of novel therapeutic targets [2] [3]. Unlike early tool compounds or clinical drugs, chemical probes must satisfy stringent experimental criteria to ensure they produce biologically meaningful and interpretable results [4] [1].

The fundamental importance of chemical probes has been magnified by the reproducibility challenges in biomedical research, where poorly characterized compounds have contributed to the robustness crisis [4]. The scientific community has responded by establishing minimal criteria, or "fitness factors," that define high-quality chemical probes and by creating curated resources to guide researchers in probe selection and use [5] [1]. This article delineates the defining criteria for chemical probes, compares their performance characteristics, details experimental validation methodologies, and contextualizes their application within chemogenomic and phenotypic screening paradigms.

Defining Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

The Fundamental "Fitness Factors"

According to consensus within the chemical biology community, high-quality chemical probes must satisfy three fundamental criteria: potency, selectivity, and demonstrated cellular activity [4] [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

| Criterion | Biochemical Standard | Cellular Standard | Validation Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | IC50 or Kd < 100 nM | EC50 < 1 μM | Dose-response curves in relevant assays |

| Selectivity | >30-fold selectivity within target family against closely related proteins | Similar selectivity profile in cellular context | Broad profiling against related targets and diverse off-targets |

| Cellular Activity | Evidence of target engagement | Modulation of pathway or phenotype at recommended concentrations | Use within recommended concentration range (typically ≤1 μM) |

Potency refers to the strength of the interaction between the chemical probe and its intended protein target, typically measured as half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) or dissociation constant (Kd) in biochemical assays [1]. For cellular applications, the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) must fall below 1 micromolar (μM) to ensure practical utility without requiring concentrations that promote off-target effects [4] [1].

Selectivity demands that a chemical probe preferentially engages its intended target over other proteins, particularly those within the same family or with structural similarities. The benchmark requires at least 30-fold selectivity against closely related proteins, complemented by extensive profiling to identify potential off-target interactions beyond the immediate target family [1]. This ensures that observed phenotypes can be confidently attributed to modulation of the intended target rather than confounding off-target effects.

Cellular Activity necessitates that the chemical probe not only binds its target in a test tube but also engages the target in live cells and produces a measurable biological effect at concentrations that maintain selectivity [4]. Even highly selective compounds become promiscuous when used at excessive concentrations, making adherence to recommended concentration ranges a critical aspect of proper probe use [4].

Additional Quality Considerations

Beyond the core criteria, several additional factors contribute to defining a high-quality chemical probe:

- Availability of Matched Target-Inactive Control Compounds: Structurally similar but target-inactive analogs provide crucial negative controls that help distinguish true on-target effects from non-specific or off-target phenotypes [4] [1].

- Availability of Orthogonal Probes: Structurally distinct compounds targeting the same protein enable confirmation of phenotypes through complementary chemical scaffolds [4].

- Absence of Promiscuous Behaviors: High-quality probes should not function as nonspecific electrophiles, redox cyclers, chelators, or colloidal aggregators that modulate biological targets promiscuously through undesirable mechanisms [1].

Performance Comparison: Chemical Probes vs. Alternative Chemical Tools

The rigorous characterization distinguishing chemical probes from other small-molecule reagents represents a critical differentiator in experimental outcomes. The table below compares key performance characteristics across compound categories.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Chemical Probes vs. Alternative Chemical Tools

| Characteristic | High-Quality Chemical Probes | Early Tool Compounds | Clinical Drugs | Uncharacterized Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | <100 nM (biochemical); <1 μM (cellular) | Variable, often >1 μM | Optimized for therapeutic window | Often unverified |

| Selectivity | >30-fold against related targets; extensively profiled | Limited or uncharacterized | May be optimized for polypharmacology | Typically unknown |

| Cellular Activity | Demonstrated at recommended concentrations | May require high concentrations | Optimized for in vivo efficacy | Not systematically evaluated |

| Control Compounds | Available (inactive analogs) | Rarely available | Not typically provided | Not available |

| Orthogonal Probes | Often available | Limited availability | Not applicable | Rarely available |

| Documentation | Detailed use recommendations (concentration, assays) | Limited guidance | Prescribing information | Minimal information |

| Typical Use Concentration | ≤1 μM (maintains selectivity) | Often >10 μM (promotes off-target effects) | Variable | Variable, often high |

The consequences of these differences manifest directly in research quality. A systematic review of 662 publications employing chemical probes in cell-based research revealed that only 4% used the probes within the recommended concentration range while also including appropriate negative controls and orthogonal probes [4]. This suboptimal implementation highlights the critical need for clearer standards and education regarding chemical probe use.

Experimental Protocols for Chemical Probe Validation

Assessing Cellular Target Engagement

Confirming that a chemical probe engages its intended target in a cellular environment represents a crucial validation step. Several advanced technologies enable direct measurement of cellular target engagement:

NanoBRET Target Engagement Assays leverage bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) between NanoLuc-tagged target proteins and target-binding fluorescent probes [6]. This approach directly and quantitatively measures apparent compound affinity and target occupancy via probe displacement in live cells without requiring cell lysis [6].

Protocol: NanoBRET Target Engagement Assay

- Construct Preparation: Generate expression vectors encoding target proteins fused to NanoLuc luciferase.

- Cell Transfection: Introduce constructs into appropriate mammalian cell lines.

- Probe Incubation: Add a cell-permeable, fluorescently-labeled probe that binds the target protein.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with varying concentrations of the chemical probe.

- BRET Measurement: Add furimazine substrate and measure both luminescence (NanoLuc signal) and BRET (fluorescence) ratios.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage target engagement from the reduction in BRET ratio caused by probe displacement.

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) monitors protein stabilization upon compound binding by measuring the resistance to thermal denaturation [6].

Protocol: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay

- Compound Treatment: Incuminate intact cells with chemical probe or vehicle control.

- Heat Challenge: Subject aliquots of cell suspension to different temperatures.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells and separate soluble protein from aggregates.

- Target Detection: Quantify remaining soluble target protein by immunoblotting or CETSA-MS (coupled with mass spectrometry).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the shift in thermal stability (ΔTm) induced by compound binding.

Chemical Proteomics uses modified versions of chemical probes as affinity baits to capture and identify protein targets directly from cell lysates or in live cells [2] [6].

Protocol: Chemical Proteomics with Live-Cell Compatibility

- Probe Design: Synthesize a probe derivative containing a bio-orthogonal reactive group (e.g., azide).

- Live-Cell Labeling: Incubate probes with intact cells to allow target engagement.

- Cell Lysis and Capture: Lyse cells and couple a capture handle (e.g., biotin) to the probe via bio-orthogonal chemistry.

- Affinity Enrichment: Isolate probe-bound protein complexes using streptavidin beads.

- Protein Identification: Digest captured proteins and identify by quantitative mass spectrometry.

- Competition Experiments: Validate specific targets by reduced enrichment in the presence of parent compound.

Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

Phenotypic screening represents a complementary approach to target-based discovery, particularly for complex biological processes and "undruggable" targets [2] [7]. The following workflow illustrates the integrated process for developing chemical probes from phenotypic screening:

Cell Painting represents a powerful morphological profiling approach that can support target deconvolution [7]. This high-content imaging method uses multiple fluorescent dyes to label various cellular components, generating rich morphological profiles that can be compared to reference compounds with known mechanisms of action.

Protocol: Cell Painting for Morphological Profiling

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells in multiwell plates suitable for high-content imaging.

- Compound Treatment: Apply chemical probes or screening hits at appropriate concentrations.

- Staining: Simultaneously stain with:

- Hoechst 33342 (nuclei)

- Concanavalin A (endoplasmic reticulum)

- Phalloidin (actin cytoskeleton)

- Wheat Germ Agglutinin (Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane)

- SYTO 14 (mitochondria and RNA)

- Image Acquisition: Automatically capture images using a high-throughput microscope.

- Feature Extraction: Use CellProfiler or similar software to quantify morphological features.

- Pattern Matching: Compare morphological profiles to reference databases to hypothesize mechanisms of action.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Chemical Probe Selection and Validation

| Resource | Type | Key Features | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Curated Database | Expert-reviewed probes, 4-star rating system, use recommendations | Probe selection and best practice guidance [5] |

| Probe Miner | Data-Driven Platform | Statistical ranking of >1.8M compounds, objective assessment | Comparative probe evaluation [4] [1] |

| EU-OPENSCREEN | Research Infrastructure | Collaborative screening, compound collection, hit-to-probe optimization | Probe discovery and development [3] |

| NanoBRET Target Engagement | Experimental Platform | Live-cell target engagement profiling, quantitative binding measurements | Cellular selectivity profiling [6] |

| CETSA-MS | Experimental Platform | Proteome-wide target engagement, thermal stability profiling | Unbiased identification of cellular targets [6] |

| Cell Painting | Phenotypic Profiling | High-content morphological profiling, mechanism of action prediction | Phenotypic screening and target hypothesis generation [7] |

Chemical probes represent indispensable tools for modern biomedical research when they satisfy stringent criteria for potency, selectivity, and cellular activity. The distinction between high-quality chemical probes and less characterized tool compounds has profound implications for research reproducibility and biological insight. As the field advances, the integration of chemogenomic libraries with phenotypic screening approaches, coupled with rigorous target deconvolution methodologies, promises to expand the repertoire of high-quality chemical probes across the human proteome. By adhering to established best practices—including using probes at recommended concentrations, incorporating inactive controls, and employing orthogonal probes—researchers can significantly enhance the validity and impact of their findings in chemical biology and drug discovery.

In the modern drug discovery landscape, chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes represent two distinct but complementary classes of research tools for investigating biological systems and validating therapeutic targets. While both are small molecules used to modulate protein function, they differ fundamentally in their design philosophy and application. Chemical probes are characterized by their high selectivity for a single protein target, adhering to strict criteria including potency (IC50 or Kd < 100 nM), selectivity (>30-fold within the target family), and demonstrated cellular activity [1] [4]. In contrast, chemogenomic compounds embrace a philosophy of selective polypharmacology—they are designed to interact with multiple specific targets within a related pathway or protein family, intentionally modulating several nodes in a biological network simultaneously [8] [9]. This deliberate multi-target activity makes chemogenomic compounds particularly valuable for studying complex diseases where modulating a single target proves therapeutically insufficient.

The distinction between these tools has significant implications for phenotypic screening research. Phenotypic screens, which test compounds in complex biological systems without preconceived molecular targets, face the challenge of target deconvolution—identifying which specific protein interactions cause the observed phenotypic effects [8]. The choice between highly selective chemical probes and deliberately polypharmacological chemogenomic libraries directly influences this process and the subsequent biological interpretations researchers can make.

Quantitative Landscape: Coverage and Polypharmacology Profiles

Proteome and Pathway Coverage

Current chemical tools provide incomplete but strategically valuable coverage of human biology. Quantitative analysis reveals that only a small fraction of the human proteome is targeted by high-quality chemical tools, with chemical probes covering approximately 2.2% of human proteins, while chemogenomic compounds cover about 1.8% [10]. Despite this limited proteome coverage, these tools collectively cover over 50% of human biological pathways, representing a versatile toolkit for dissecting a substantial portion of human biology [10]. This disparity suggests that existing compounds strategically target key proteins across many pathways rather than providing comprehensive coverage of the proteome.

Table 1: Proteome and Pathway Coverage of Chemical Tools

| Metric | Chemical Probes | Chemogenomic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Proteome Coverage | 2.2% | 1.8% |

| Pathway Coverage | ~53% of human pathways | Contributes to ~53% total pathway coverage |

| Primary Design Strategy | Target single proteins with high specificity | Target multiple related proteins intentionally |

| Key Protein Families | Kinases, GPCRs, epigenetic regulators | Kinases, GPCRs, and other druggable families |

Polypharmacology Profiles

The polypharmacology of chemogenomic libraries can be quantified using a polypharmacology index (PPindex), which measures the target-specificity of compound collections through analysis of target annotation distributions [8]. Comparative studies of prominent libraries reveal distinct polypharmacology profiles:

Table 2: Polypharmacology Index (PPindex) of Selected Compound Libraries

| Compound Library | PPindex (All Targets) | PPindex (Without 0-target compounds) | Library Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | 0.9594 | 0.7669 | Broad collection of drugs; appears target-specific due to data sparsity |

| LSP-MoA | 0.9751 | 0.3458 | Optimized for kinome coverage; shows significant polypharmacology |

| MIPE 4.0 | 0.7102 | 0.4508 | Mechanism Interrogation Plate; moderate polypharmacology |

| Microsource Spectrum | 0.4325 | 0.3512 | Bioactive collection; shows broad polypharmacology |

The PPindex analysis demonstrates that chemogenomic libraries exhibit substantial polypharmacology, with many compounds interacting with multiple molecular targets [8]. This characteristic creates both challenges and opportunities for phenotypic screening approaches.

Experimental Applications and Best Practices

Phenotypic Screening and Target Deconvolution

In phenotypic screening, the fundamental challenge is identifying the molecular targets responsible for observed phenotypic effects after discovering active compounds. Chemogenomic libraries offer a strategic advantage for this process when compounds have well-annotated target profiles. The underlying principle is that if a compound's target interactions are known, any phenotype it induces can be logically connected to its target portfolio [8].

However, the utility of this approach depends heavily on the quality of target annotations and the actual specificity of the compounds. Studies have shown that many compounds in chemogenomic libraries exhibit more extensive polypharmacology than initially assumed, complicating straightforward target deconvolution [8]. The presence of a significant number of compounds with incomplete or inaccurate target annotations further challenges this paradigm.

Best Practice Guidelines for Chemical Tool Usage

Robust experimental design requires adherence to established best practices for using chemical tools:

The Rule of Two: Implement at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes, and/or a pair of a chemical probe and matched target-inactive compound) in every study [4]. This approach controls for off-target effects and strengthens mechanistic conclusions.

Concentration Optimization: Use chemical probes strictly within their validated concentration range. Even highly selective compounds become promiscuous at excessive concentrations [4]. Current data indicates alarmingly low compliance (approximately 4% of publications) with this fundamental requirement [4].

Control Compounds: Always include structurally matched target-inactive control compounds where available to distinguish target-specific from non-specific effects [1] [4].

Orthogonal Validation: Employ multiple chemogenomic compounds with overlapping target profiles but distinct chemical scaffolds to confirm observations across different compound classes [4].

Computational Approaches for Polypharmacology

Predicting and Designing Multi-Target Compounds

Computational methods have become indispensable for understanding and exploiting polypharmacology. Both ligand-based and structure-based approaches enable researchers to predict the polypharmacological profiles of bioactive compounds:

Ligand-based methods operate on the principle that similar chemical structures often share biological activities. These include:

- 2D similarity searching using molecular fingerprints to identify potential targets based on structural similarity to compounds with known activities [11]

- 3D similarity and pharmacophore mapping to identify common three-dimensional molecular features that drive interactions with multiple targets [11]

- Machine learning models trained on large chemogenomic datasets to predict novel compound-target interactions [9] [12]

Structure-based methods leverage protein three-dimensional structures:

- Inverse docking approaches that dock a single compound against multiple protein targets to identify potential off-target interactions [11]

- Binding site similarity analysis to identify unexpected target relationships based on similar structural features in otherwise unrelated proteins [11]

- Molecular dynamics simulations to study compound binding and unbinding kinetics across multiple targets

Generative AI for Polypharmacology Design

Recent advances in generative artificial intelligence have enabled the deliberate design of multi-target compounds. The POLYGON (POLYpharmacology Generative Optimization Network) system represents a cutting-edge approach that combines variational autoencoders with reinforcement learning to generate novel chemical structures optimized for multiple targets simultaneously [9].

The POLYGON workflow begins with training a variational autoencoder on over one million diverse small molecules from the ChEMBL database to create a continuous chemical embedding space [9]. The system then uses reinforcement learning to sample this space, rewarding compounds predicted to inhibit multiple targets of interest while maintaining favorable drug-like properties. This approach has demonstrated 82.5% accuracy in recognizing polypharmacology interactions in benchmarking studies and has successfully generated novel compounds targeting synthetically lethal cancer protein pairs, with several candidates showing significant biological activity in experimental validation [9].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemogenomic Research

| Resource/Solution | Type | Key Features/Applications | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Database | Expert-curated chemical probes with quality ratings; covers >400 protein targets | https://www.chemicalprobes.org |

| SGC Chemical Probes | Compound Collection | 100+ unencumbered chemical probes for epigenetic proteins, kinases, GPCRs | https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes |

| Probe Miner | Database | Statistically-based ranking of >1.8M compounds from literature data | https://probeminer.icr.ac.uk |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactivity data on drug-like small molecules; critical for predictive modeling | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| DrugBank | Database | Comprehensive drug and drug target information | https://go.drugbank.com |

| POLYGON | Generative AI | De novo design of multi-target compounds using deep learning | Research implementation |

| LSP-MoA Library | Compound Library | Optimized for kinome coverage; used for phenotypic screening | Research use |

| MIPE 4.0 | Compound Library | Small molecule probes with known mechanisms of action | Research use |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of chemogenomics is rapidly evolving with several emerging technologies poised to expand capabilities for selective polypharmacology research:

Advanced Profiling Technologies combine chemical structures with high-throughput phenotypic profiling (Cell Painting, L1000 gene expression) to predict compound bioactivity across multiple assays. Integrated models using all three data modalities can predict 21% of assays with high accuracy (AUROC > 0.9), significantly outperforming single-modality approaches [12]. This multi-modal profiling represents a powerful approach for comprehensive compound characterization.

Protein Degradation Technologies, including PROTACs and molecular glues, represent a growing class of chemical tools that exploit polypharmacology in a unique way—by simultaneously engaging a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase to induce target degradation [1]. These bifunctional molecules can achieve remarkable selectivity even when their target-binding components exhibit some promiscuity, expanding the druggable proteome to include proteins without functional binding pockets [1].

Automated Synthesis and Screening platforms are increasing the throughput of chemogenomic compound production and testing. Integrated systems combining automated synthesis with high-throughput screening and multi-omics readouts are accelerating the characterization of compound polypharmacology and biological effects [13].

As these technologies mature, they will enhance researchers' ability to deliberately design compounds with precisely tuned polypharmacological profiles, advancing both fundamental biological understanding and therapeutic development for complex diseases.

In the landscape of phenotypic screening and target identification, chemical probes and chemogenomic libraries represent two complementary but distinct toolkits. Chemical probes are highly selective, well-validated small molecules designed to modulate a specific protein target with high confidence, making them ideal for mechanistic validation [14]. In contrast, chemogenomic libraries consist of collections of pharmacological agents with annotated but often overlapping target profiles, enabling systematic exploration of broader biological target space and accelerated hypothesis generation [15]. This guide objectively compares their performance characteristics, experimental applications, and appropriate contexts for use in drug discovery pipelines.

Defining Characteristics and Performance Standards

Chemical Probes: The Gold Standard for Target Validation

Chemical probes are characterized by stringent validation criteria essential for confident target validation. According to community standards, high-quality chemical probes must demonstrate potency below 100 nM in vitro, selectivity of at least 30-fold against related proteins, and cellular target engagement at concentrations ideally below 1 μM [16] [14]. These compounds are peer-reviewed by expert panels through resources like the Chemical Probes Portal and are typically accompanied by structurally similar inactive control compounds to confirm on-target effects [16] [14].

The EUbOPEN consortium, a major contributor to the Target 2035 initiative, further stipulates that chemical probes should have a reasonable cellular toxicity window (unless cell death is target-mediated) and be profiled in patient-derived disease assays for relevant biological contexts [16]. This rigorous characterization ensures that observed phenotypes can be reliably attributed to modulation of the intended target rather than off-target effects.

Chemogenomic Libraries: Tools for Broad Exploration

Chemogenomic libraries employ a different strategy, utilizing compounds that may bind to multiple targets but with well-characterized activity profiles [16]. Rather than pursuing exclusive selectivity for single targets, these libraries leverage compounds with overlapping target profiles that enable target deconvolution through pattern recognition across multiple screening hits [16] [7]. The European EUbOPEN consortium has developed a chemogenomic library covering approximately one-third of the druggable proteome, demonstrating the scalability of this approach [16].

These libraries are particularly valuable for phenotypic screening campaigns where the molecular targets underlying observable phenotypes are unknown [7] [15]. When screening a chemogenomic library, a hit suggests that the annotated target(s) of that pharmacological agent may be involved in perturbing the observed phenotype, providing immediate starting points for further investigation [15].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Chemical Probes vs. Chemogenomic Libraries

| Characteristic | Chemical Probes | Chemogenomic Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity Profile | High selectivity (≥30-fold against related targets) | Overlapping target profiles enabling pattern recognition |

| Primary Application | Target validation and mechanistic studies | Target discovery and hypothesis generation |

| Proteome Coverage | Limited (~2.2% of human proteins) but deep | Broad (covering ~1/3 of druggable proteome) |

| Control Requirements | Matched target-inactive control compounds essential | Less dependent on controls for individual compounds |

| Validation Timeline | Long development (often years per probe) | Rapid deployment of existing compound collections |

| Data Interpretation | Direct causal inference to single target | Statistical inference from multiple compound activities |

Experimental Applications and Workflows

Target Validation with Chemical Probes

The optimal use of chemical probes in target validation follows the "rule of two" recommendation: employing at least two orthogonal chemical probes (with different chemical structures) targeting the same protein, along with matched inactive control compounds, at their recommended concentrations [14]. This approach controls for off-target effects and increases confidence that observed phenotypes result from on-target modulation.

A workflow for proper chemical probe application involves:

- Probe Selection: Identifying recommended chemical probes through expert resources (Chemical Probes Portal, Probe Miner)

- Concentration Optimization: Using probes within their validated concentration range (typically 1 μM or below for cellular assays)

- Control Implementation: Including structurally matched inactive compounds and orthogonal probes

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measuring specific phenotypic endpoints relevant to the biological question

- Data Triangulation: Comparing results across multiple probe and control conditions

Recent studies indicate suboptimal implementation of these practices, with only 4% of publications analyzing chemical probes using all three best practices: recommended concentrations, inactive controls, and orthogonal probes [14]. This highlights the need for improved experimental design in target validation studies.

Broad Target Exploration with Chemogenomic Libraries

Chemogenomic library screening follows a different workflow focused on pattern recognition across multiple compounds:

- Library Design: Assembling compounds with annotated activities across target families

- Phenotypic Screening: Testing compounds in disease-relevant phenotypic assays

- Hit Identification: Selecting compounds that modulate the phenotype of interest

- Target Hypothesis Generation: Analyzing annotated targets of hit compounds

- Pathway Analysis: Identifying biological pathways enriched among hit compound targets

Advanced implementations incorporate high-content readouts such as Cell Painting morphology analysis or single-cell RNA sequencing to capture complex phenotypic responses [7] [17]. Recent methodological innovations include compressed screening approaches that pool compounds to increase throughput while computationally deconvoluting individual compound effects [17].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Proteome Coverage and Pathway Analysis

Current chemical tools have achieved differential coverage of human biological pathways. While available chemical tools target only 3% of the human proteome collectively, they already cover 53% of human biological pathways, representing a versatile toolkit for dissecting a vast portion of human biology [10]. Breaking this down further:

Table 2: Proteome and Pathway Coverage of Chemical Tools

| Tool Category | Proteome Coverage | Pathway Coverage | Key Target Families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | 2.2% of human proteins | ~50% of pathways | Kinases, GPCRs, E3 ligases |

| Chemogenomic Compounds | 1.8% of human proteins | ~50% of pathways | Diverse target families |

| Approved Drugs | 11% of human proteins | Not specified | Established drug targets |

This data indicates that while chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds cover a small percentage of the proteome individually, they collectively enable investigation of most biological pathways due to strategic targeting of key pathway components [10].

Experimental Success Rates and Efficiency

In direct screening comparisons, chemogenomic libraries demonstrate efficiency in identifying mechanistically relevant hits. One study screening a selective compound library against the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel found that 26% of tested compounds (10 of 38) exhibited more than 80% growth inhibition in at least one cell line, with most hits showing selective activity against limited cell lines rather than broad cytotoxicity [18]. This pattern-specific activity facilitates the identification of novel therapeutic targets and mechanisms.

Chemical probes, while more resource-intensive to develop and implement properly, provide higher confidence in target-phenotype relationships when used according to best practices. However, the finding that only 4% of publications employ chemical probes with recommended concentrations, inactive controls, AND orthogonal probes indicates significant room for improvement in implementation [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Key Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probe Repositories | EUbOPEN Donated Chemical Probes Project, SGC Chemical Probes, Chemical Probes Portal | Peer-reviewed chemical probes with usage guidelines | https://www.eubopen.org/chemical-probes |

| Chemogenomic Libraries | EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library, Pfizer Chemogenomic Library, NCATS MIPE Library | Annotated compound collections for phenotypic screening | Various access models (academic, commercial) |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, Probe Miner, Probes & Drugs | Bioactivity data for compound selection and validation | Publicly accessible |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Chemical Probes Portal star ratings, Probe Miner global scores | Expert and data-driven compound quality assessment | Online platforms |

| Phenotypic Profiling Assays | Cell Painting, High-content imaging, scRNA-seq | Multiparametric readouts for complex phenotype capture | Protocol publications and core facilities |

Chemical probes and chemogenomic libraries serve distinct but complementary roles in modern drug discovery. Chemical probes provide the specificity and validation confidence required for definitive mechanistic studies and advanced target validation, particularly for programs approaching candidate selection. Chemogenomic libraries offer broad target space coverage and efficient hypothesis generation for early discovery phases, especially in phenotypic screening campaigns where molecular targets are unknown.

The most effective drug discovery pipelines strategically employ both tools: using chemogenomic libraries for initial target identification and hypothesis generation, followed by chemical probes for rigorous validation and mechanistic studies of prioritized targets. This integrated approach leverages the respective strengths of each tool class while mitigating their individual limitations, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics.

The systematic exploration of human disease biology has been fundamentally transformed by the development and application of two complementary classes of chemical tools: chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds. These reagents have enabled researchers to bridge the gap between genetic information and biological function, moving beyond observation to active perturbation of biological systems. Chemical probes are characterized by their high potency and selectivity for specific protein targets, allowing precise mechanistic studies [16]. In contrast, chemogenomic compounds exhibit broader polypharmacology across related targets, enabling the interrogation of entire protein families and biological pathways through overlapping activity patterns [16]. The strategic deployment of these tools in phenotypic screening has unveiled novel disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities that were previously inaccessible to target-based approaches. This article examines the historical impact of these chemical tools, comparing their capabilities, applications, and contributions to unlocking novel disease biology.

Quantitative Comparison of Tool Coverage and Characteristics

The fundamental differences between chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds can be understood through their distinct roles in biological exploration. Current analysis reveals that only a small fraction of the human proteome is covered by high-quality chemical tools—approximately 2.2% by chemical probes, 1.8% by chemogenomic compounds, and 11% by drugs [10]. Despite this limited direct coverage, these tools collectively impact a substantially greater proportion of biological pathways—approximately 53%—demonstrating their powerful network effects [10].

Table 1: Proteome and Pathway Coverage of Chemical Tools

| Tool Category | Proteome Coverage | Pathway Coverage | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | 2.2% | ~53% (collectively) | Target validation, mechanistic studies |

| Chemogenomic Compounds | 1.8% | ~53% (collectively) | Pathway interrogation, polypharmacology studies |

| Approved Drugs | 11% | Not specified | Therapeutic development |

Table 2: Characteristic Profiles of Chemical Tools

| Attribute | Chemical Probes | Chemogenomic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | <100 nM in vitro [16] | Variable, typically <10 μM [16] |

| Selectivity | ≥30-fold over related proteins [16] | Designed with overlapping target profiles |

| Cell Activity | Target engagement <1 μM [16] | Well-characterized cellular activity |

| Key Initiatives | EUbOPEN (50 new probes), Donated Chemical Probes project [16] | EUbOPEN CG library (covers 1/3 of druggable proteome) [16] |

| Data Standards | Peer-reviewed, information sheets for proper use [16] | Family-specific criteria for different target classes [16] |

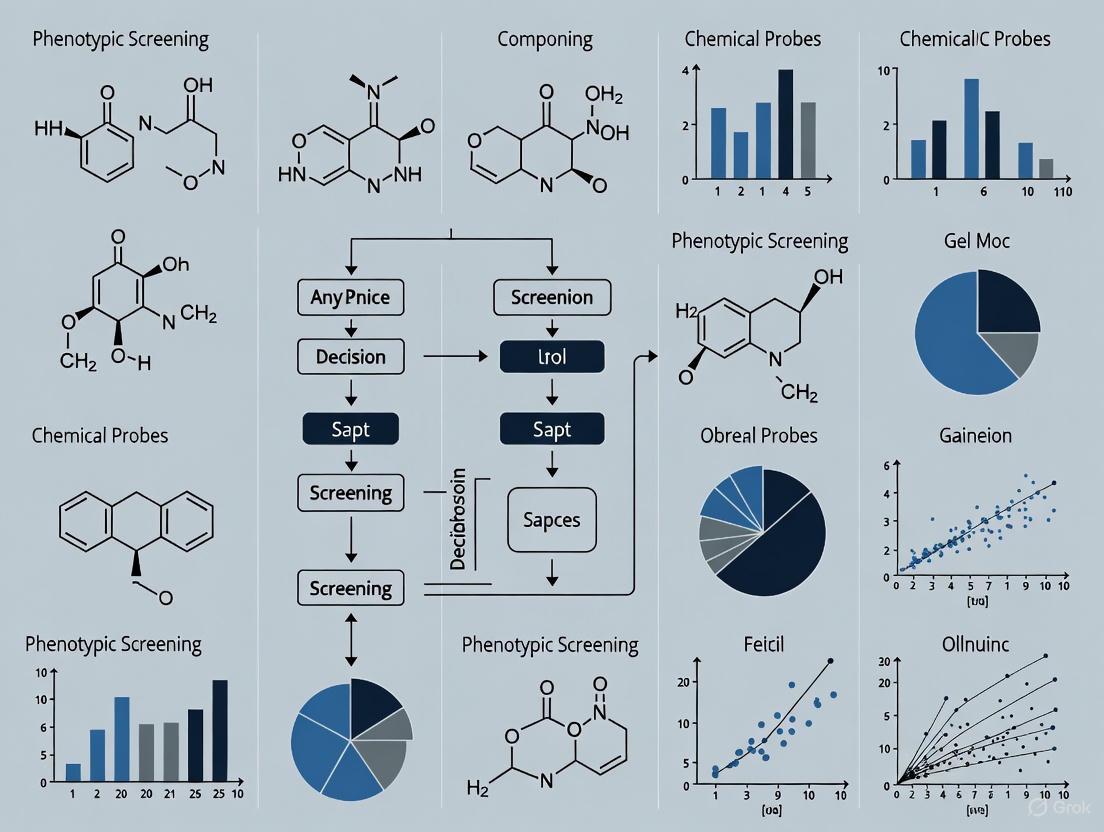

The following diagram illustrates the key characteristics and selection criteria for these two classes of chemical tools:

Figure 1: Characteristics and selection criteria for chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds.

Applications in Phenotypic Screening for Novel Biology

Phenotypic screening represents a powerful approach for discovering novel biology without presupposing molecular targets. These screens observe how cells or organisms respond to chemical or genetic perturbations, capturing complex disease-relevant phenotypes [19]. The integration of chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds has significantly enhanced this approach by providing well-characterized perturbation tools.

High-Content Phenotypic Screening Platforms

Advanced phenotypic screening platforms utilize high-content imaging to capture multiparametric measures of cellular responses to chemical perturbations. The ORACL (Optimal Reporter cell line for Annotating Compound Libraries) method systematically identifies reporter cell lines whose phenotypic profiles most accurately classify known drugs [20]. This approach involves:

- Reporter Cell Line Construction: Creating triply-labeled live-cell reporter lines with markers for cell segmentation (mCherry for whole cell), nuclear identification (H2B-CFP), and protein monitoring (YFP-tagged endogenous proteins) [20]

- Phenotypic Profiling: Transforming compound-induced cellular responses into quantitative vectors using image analysis and Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics to compare feature distributions between treated and untreated cells [20]

- Pattern Recognition: Identifying similarity in phenotypic profiles among compounds sharing mechanisms of action, enabling classification of novel compounds into functional categories [20]

Chemogenomic Library Screening in Phenotypic Discovery

Chemogenomic libraries enable systematic exploration of biological pathways through their designed polypharmacology. In phenotypic screening, these libraries offer distinct advantages:

- Target Family Coverage: Well-annotated chemogenomic libraries interrogate approximately 1,000-2,000 human genes, significantly expanding beyond the limited coverage of individual target-based screens [21]

- Pathway Deconvolution: By employing multiple compounds with overlapping target profiles within a protein family, researchers can distinguish target-specific effects from off-target activities [16]

- Network Biology Insights: The polypharmacology of chemogenomic compounds often mirrors the complexity of biological systems, revealing synergistic effects and network relationships [16]

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for phenotypic screening that integrates both chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds:

Figure 2: Integrated phenotypic screening workflow using chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of chemical tool-based research requires access to well-characterized reagents and platforms. The following table details key resources available to researchers:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Chemical Biology

| Reagent/Platform | Type | Key Features | Access Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUbOPEN Chemical Probes | Chemical Tools | 50+ peer-reviewed probes; potency <100 nM; selectivity ≥30-fold; includes negative controls [16] | EUbOPEN Consortium |

| EUbOPEN Chemogenomic Library | Compound Collection | Covers 1/3 of druggable proteome; annotated with biochemical/cell-based assays; includes patient-derived cell data [16] | EUbOPEN Consortium |

| ORACL Reporter Cells | Cell Lines | Triply-labeled (nuclear, cellular, protein markers); enables live-cell phenotypic profiling [20] | Academic collaborators |

| EU-OPENSCREEN | Screening Infrastructure | Provides HTS, chemoproteomics, spatial MS-based omics, and medicinal chemistry support [22] | EU-OPENSCREEN ERIC |

| Cell Painting Assay | Phenotypic Platform | Fluorescent staining of cellular components; reveals morphological changes [19] | Broad Institute |

| PhenAID | AI-Phenotypic Platform | Integrates cell morphology, omics data, and metadata for MoA prediction [19] | Ardigen |

Experimental Protocols for Tool Application

To ensure reproducible and informative results from chemical tool experiments, researchers should follow established protocols for tool characterization and application:

Protocol 1: Chemical Probe Validation for Phenotypic Screening

This protocol ensures that chemical probes are properly validated before use in phenotypic assays:

- In Vitro Potency Assessment: Determine IC50 or Kd values using biochemical assays, with criteria requiring potency <100 nM [16]

- Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate against related targets (same family or structurally similar off-targets) to confirm minimum 30-fold selectivity window [16]

- Cellular Target Engagement: Confirm compound reaches and engages intended target in cellular context at relevant concentrations (<1 μM for most targets, <10 μM for challenging targets) [16]

- Phenotypic Profiling: Implement in phenotypic screening platform with appropriate controls, including:

- Specificity Validation: Use orthogonal approaches (CRISPR, RNAi, alternative chemical probes) to confirm phenotypic specificity [21]

Protocol 2: Chemogenomic Library Screening for Pathway Discovery

This protocol outlines the application of chemogenomic compound sets for pathway identification:

- Library Design: Select compounds with overlapping target profiles within protein families of interest, ensuring multiple chemotypes per target where possible [16]

- Multiplexed Phenotypic Screening: Implement high-content imaging with the Cell Painting assay or specific pathway reporters to capture diverse phenotypic features [19] [20]

- Profile Generation and Analysis:

- Pattern Recognition and Target Inference:

- Validation: Confirm putative targets through orthogonal approaches (genetic perturbation, additional selective compounds) [21]

Impact on Disease Biology and Therapeutic Discovery

The application of chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds in phenotypic screening has led to significant advances in understanding disease mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic strategies:

Oncology Applications

In cancer research, these tools have revealed novel vulnerabilities and resistance mechanisms:

- Identification of WRN helicase as a synthetic lethal target in microsatellite instability-high cancers through functional genomic screening [21]

- Discovery of selective modulators of esophageal cancer phenotypes through multiparametric high-content screening with copper ionophores [21]

- Uncovering novel targets for triple-negative breast cancer through machine learning approaches applied to phenotypic data [19]

Neuroscience and Rare Diseases

Chemical tools have enabled breakthroughs in challenging disease areas:

- Discovery of pharmacological chaperones for cystic fibrosis (e.g., lumacaftor) through phenotypic screening [21]

- Identification of splicing modifiers for spinal muscular atrophy (e.g., risdiplam) without predefined molecular targets [21]

- Revelation of dopamine neuron-specific stress responses in Parkinson's disease models through single-cell transcriptomics of chemically perturbed systems [21]

The strategic application of chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds has fundamentally expanded our ability to explore disease biology through phenotypic screening. As these approaches continue to evolve, several trends are shaping their future development. International initiatives such as Target 2035 aim to develop chemical tools for most human proteins by 2035, dramatically expanding the toolbox available for biological discovery [10] [16]. The integration of artificial intelligence with phenotypic screening data is enhancing pattern recognition and target prediction capabilities, enabling more efficient extraction of biological insights from complex datasets [19] [23]. Furthermore, the emergence of new modalities including molecular glues, PROTACs, and covalent binders is expanding the druggable proteome and creating opportunities to target previously inaccessible disease pathways [16]. Through the continued refinement and strategic application of these chemical tools, researchers are positioned to unlock previously inaccessible aspects of disease biology, paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies across a broad spectrum of human diseases.

Strategic Implementation: Integrating Probes and Chemogenomic Libraries in Screening Workflows

Designing Phenotypic Screens: When to Deploy Focused Probes vs. Diverse Chemogenomic Sets

Phenotypic screening remains a powerful empirical strategy for uncovering novel biological insights and first-in-class therapies. The critical initial decision in designing these screens—whether to use focused chemical probes or diverse chemogenomic libraries—significantly impacts the biological questions that can be answered and the success of downstream development. This guide compares these approaches to help researchers select the optimal strategy for their specific project goals.

Core Definitions and Strategic Applications

Chemical Probes are highly selective, potent, and well-characterized small molecules used to modulate specific protein targets in cells. To qualify as a true chemical probe, a molecule must meet stringent criteria: in vitro potency typically below 100 nM, at least 30-fold selectivity against related proteins, and demonstrated on-target activity in cells at reasonable concentrations, ideally below 1 μM [24] [4]. These tools allow researchers to make confident conclusions about the function of specific proteins they target.

Chemogenomic Libraries are collections of compounds designed to interrogate a broad spectrum of biological targets. These libraries aim for diversity, often spanning thousands of gene targets, though even comprehensive collections cover only a fraction of the human proteome—typically 1,000–2,000 out of 20,000+ genes [21]. They include compounds with varying levels of characterization, from well-annotated bioactive molecules to those with unknown targets and mechanisms.

The decision between these approaches hinges on the research objective. Focused chemical probes are ideal for target validation, where the goal is to establish a causal relationship between a specific protein's activity and a phenotypic outcome. Conversely, diverse chemogenomic sets excel in novel target discovery, where the aim is to identify previously unknown proteins or pathways involved in a biological process without preconceived hypotheses [21] [25].

Table 1: Strategic Applications of Screening Approaches

| Screening Approach | Primary Research Goal | Typical Library Size | Target Coverage | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focused Chemical Probes | Target validation, mechanism of action studies | 1 - 10s of compounds | Single or few closely related targets | Confirming a specific target's role in phenotype; pathway dissection |

| Diverse Chemogenomic Sets | Novel target discovery, hypothesis generation | 100s - 100,000s of compounds | 1,000 - 2,000 targets | Unbiased discovery; systems-level interrogation; phenotypic mining |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Implementing Chemical Probes: Best Practices and Controls

Proper experimental design is crucial when using chemical probes to generate reliable data. The "Rule of Two" framework recommends employing at least two orthogonal validation strategies in every study [4]:

- Use at least two orthogonal chemical probes with different chemical structures that target the same protein.

- Include matched target-inactive control compounds that are structurally similar but pharmacologically inactive against the intended target.

- Always use probes within their validated concentration range, as even highly selective probes become non-specific at excessive concentrations.

A striking systematic review revealed that only 4% of analyzed publications adhered to all these best practices, highlighting the need for improved experimental design [4]. For example, when studying EZH2 function, optimal practice would use both UNC1999 and GSK343 (orthogonal probes) alongside the inactive control UNC2400, with all compounds maintained at concentrations ≤1μM to ensure target specificity [4].

Phenotypic Screening with Chemogenomic Libraries

Chemogenomic library screening follows a different workflow focused on hit identification and subsequent target deconvolution. A representative protocol for screening a library to identify modulators of cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) activation [26]:

Primary Screening Protocol:

- Cell model preparation: Seed primary human lung fibroblasts in 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well) and allow adherence overnight.

- Co-culture establishment: Add MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and THP-1 monocytes at optimized ratios (e.g., 1:2:0.5 fibroblast:cancer:monocyte ratio).

- Compound treatment: Add chemogenomic library compounds at 1-10μM, typically in DMSO vehicle (final concentration ≤0.1%).

- Incubation: Maintain cells at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48-72 hours.

- Phenotypic readout: Fix cells and stain for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) as a marker of CAF activation.

- High-content imaging and analysis: Quantify α-SMA intensity per cell using automated microscopy and image analysis.

- Hit selection: Identify compounds that significantly reduce α-SMA expression compared to DMSO controls (Z' factor >0.5 indicates robust assay).

Target deconvolution for hits from chemogenomic screens often involves techniques like affinity purification, cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA), or proteomic profiling to identify the specific molecular targets responsible for the observed phenotype [21] [27].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Each screening approach presents distinct advantages and limitations that directly impact their performance in different research contexts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Performance Metric | Focused Chemical Probes | Diverse Chemogenomic Sets |

|---|---|---|

| Target Specificity | High (validated selectivity) | Variable (requires confirmation) |

| Novel Target Discovery | Limited | High (unbiased approach) |

| Interpretability of Results | High (known mechanism) | Low initially (requires deconvolution) |

| Development Timeline | Shaper (known starting point) | Longer (target ID required) |

| Risk of Off-target Effects | Low (when used properly) | High (polypharmacology common) |

| Chemical Optimization Required | Minimal (pre-validated) | Extensive (hit-to-probe optimization) |

Key limitations of small molecule screening include limited target coverage, as even the best libraries address only 5-10% of the human proteome. Additionally, compounds may exhibit poor aqueous solubility, membrane permeability, or cellular stability, and false positives from promiscuous inhibitors or assay interference compounds remain a significant challenge [21].

Notable successes from phenotypic screening include the discovery of immunomodulatory drugs like thalidomide analogs. Phenotypic screening of thalidomide analogs led to lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which were later found to function by binding cereblon and modulating the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [27].

Integrated Workflows and Emerging Solutions

Advanced Screening Methodologies

Compressed screening represents an innovative approach that pools multiple perturbations to enhance throughput. In this method [17]:

- N perturbations are combined into unique pools of size P

- Each perturbation appears in R distinct pools overall

- This enables P-fold compression, reducing sample number, cost, and labor

- Effects of individual perturbations are deconvoluted using computational approaches like regularized linear regression

Informer sets are strategically designed subsets of larger compound collections that capture their chemical or biological diversity. These include [28]:

- Target-focused informer sets (e.g., kinase-focused or PPI-focused libraries)

- Phenotype-focused informer sets selected based on phenotypic profiling data

- Generally bioactive sets maximizing historical bioactivity and chemical diversity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Curated resource for high-quality chemical probes | Identifying recommended probes for specific targets; accessing usage guidelines |

| Cell Painting Assay | High-content morphological profiling using multiplexed dyes | Detecting nuanced phenotypic changes across multiple cellular compartments |

| EUbOPEN Compound Collection | Open-access chemogenomic library | Screening ~1,000 biologically relevant targets; hit identification |

| BRET-Based Target Engagement | Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer technology | Confirming cellular target engagement of hit compounds |

| High-Content Live-Cell Imaging | Machine learning-powered image analysis | Quantifying complex phenotypes; detecting phospholipidosis |

Decision Framework and Visual Guide

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points in selecting the appropriate screening strategy:

Decision Framework for Screening Strategy Selection

Both focused chemical probes and diverse chemogenomic libraries offer distinct advantages for phenotypic screening. Chemical probes provide precision and mechanistic insight for target validation, while chemogenomic libraries enable unbiased discovery of novel biology. The most successful screening campaigns often integrate both approaches—using chemogenomic libraries for initial discovery followed by chemical probes for target validation—creating a powerful iterative workflow for advancing both basic biology and therapeutic development.

In modern drug discovery, the choice of disease model critically influences the translatability of research, especially in the context of phenotypic screening for chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, while cost-effective and scalable, suffer from significant limitations as they lack the physiological tissue architecture and cell-microenvironment interactions found in vivo [29] [30]. This gap has accelerated the development of more sophisticated three-dimensional (3D) models, including primary cell cultures, patient-derived organoids (PDOs), and various patient-derived assays, which better recapitulate the complexity of human tissues and tumors [31] [32]. These advanced models are proving indispensable for evaluating compound efficacy, understanding drug resistance mechanisms, and developing personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately providing more predictive platforms for decision-making in preclinical research [32] [33].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Advanced Disease Models

| Model Type | Key Features | Stem Cell Source | Physiological Relevance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Primary Cell Cultures | Monolayer culture; simplified microenvironment; easy maintenance [30] | Not required | Low to Moderate; lacks native tissue architecture [30] | Basic mechanistic studies; initial high-throughput toxicity screening [34] |

| 3D Multicellular Spheroids | Cell aggregates; generate nutrient/oxygen gradients; self-assembly [31] | Not required | Moderate; mimics tumor micro-regions and chemoresistance [31] [30] | Intermediate-throughput drug screening; studies of tumor hypoxia and metabolism [31] |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | Self-organizing 3D structures; multiple cell lineages; genetically stable [35] [36] | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) or Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs) [35] [36] | High; recapitulates original tumor architecture and patient-specific responses [35] [29] | Biobanking; personalized therapy prediction; large-scale drug discovery [35] [32] |

| iPSC-Derived Organoids | Models developmental stages; scalable; genetically tractable [36] | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [36] | High for development and genetic diseases; can lack full maturity [36] | Disease modeling (especially genetic disorders); developmental biology; toxicology studies [36] |

Comparative Analysis of Model Systems for Drug Screening

Architectural and Functional Fidelity

The transition from 2D to 3D culture systems represents a fundamental shift towards greater physiological relevance. In 2D monolayers, cells adopt flattened morphologies, lose polarity, and exhibit altered gene expression profiles, which disturbs their native functionality [30]. For instance, hepatocytes in 2D culture show markedly different cytochrome P450 (CYP) profiles compared to their 3D counterparts, which has profound implications for drug metabolism studies [34]. In contrast, 3D models, whether spheroids or organoids, preserve tissue-specific architecture and cell-cell interactions, creating microenvironments with gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolites that closely mirror conditions in human tumors [31] [30]. This architectural fidelity directly impacts cellular responses, with 3D-cultured cells frequently demonstrating chemoresistance patterns observed in vivo, unlike their 2D-cultured counterparts [31].

Practical Considerations: Scalability, Reproducibility, and Throughput

While 3D models offer superior biological relevance, practical implementation requires careful consideration of scalability, reproducibility, and throughput. Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) stand out for their ability to be biobanked, enabling long-term expansion and repeat studies without compromising genetic identity [35]. However, they can exhibit variability and may be less amenable to the highest tiers of high-throughput screening (HTS) [31]. 3D spheroids, particularly those formed using low-adhesion plates, offer higher reproducibility and are more readily scalable to different plate formats, making them compliant with HTS and high-content screening (HCS) applications [31]. iPSC-derived organoids provide remarkable scalability and the ability to work within a traceable donor-specific genetic background, but challenges remain regarding prolonged differentiation protocols and variability in maturation levels [36].

Table 2: Practical Application in Drug Discovery Screening

| Parameter | 2D Primary Cultures | 3D Spheroids | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput Potential | High; suitable for 384/1536-well formats [34] | Intermediate to High; scalable with standardized plates [31] | Lower; can be variable and harder to adapt to ultra-HTS [31] |

| Reproducibility | High performance and reproducibility [30] | High reproducibility with defined protocols [31] | Can be variable; requires standardized culture protocols [31] [36] |

| Long-term Maintenance | Short-lived; cells become senescent over passages [35] [30] | Limited long-term culture potential | Long-term expansion possible; suitable for biobanking [35] [29] |

| Cost & Technical Demand | Low cost; simple protocols [29] [30] | Moderate cost; requires specialized plates/materials [30] | Higher cost; demands greater technical expertise [34] |

| Key Advantage in Screening | Cost-effective for large-scale repetitive studies [34] | Balances physiological relevance with HTS compatibility [31] | High clinical predictive value for patient-specific responses [32] |

Application in Phenotypic Screening: Chemogenomic Compounds vs. Chemical Probes

Within phenotypic screening paradigms, the distinction between chemogenomic compounds (often targeting specific gene families or pathways) and chemical probes (tool compounds used to interrogate specific biological targets) necessitates careful model selection. For chemical probe validation, where understanding precise on-target effects is paramount, the more uniform conditions of 2D cultures or simpler 3D spheroids can be advantageous, as they reduce complexity and facilitate mechanistic interpretation [34]. Conversely, for chemogenomic compound screening, where the goal is often to identify compounds that modulate complex disease phenotypes, the physiological context provided by PDOs is invaluable. PDOs preserve the genetic heterogeneity of the original tumor, enabling the identification of compounds effective across diverse genetic backgrounds and capturing patient-specific differential responses [32] [37].

The workflow for utilizing these models in screening involves establishing the model system, treating with compound libraries, and employing sophisticated endpoint analyses. For PDOs, high-resolution confocal imaging permits tracking of cellular changes like cell birth and death in individual organoids, while also measuring morphological features such as volume and sphericity. This allows for the determination of differential responses (cytotoxic vs. cytostatic) to therapeutic interventions [37].

Diagram: Model Selection Workflow for Phenotypic Screening. This workflow guides the selection of advanced disease models based on the specific objective of the phenotypic screen, whether for targeted chemical probe validation or broader chemogenomic compound discovery.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Establishing Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids (PDTOs) for Drug Screening

The generation of PDTOs enables highly patient-relevant drug testing. The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [35] [29] [32]:

- Tissue Processing: Obtain fresh tumor tissue via surgical resection or biopsy. Mechanically mince the tissue followed by enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase/dispase) at 37°C for 30-120 minutes to create a single-cell suspension or small fragments.

- Matrix Embedding: Resuspend the cell pellet in a basement membrane matrix (e.g., Matrigel or BME). Plate the cell-matrix suspension as small droplets in pre-warmed culture plates and allow polymerization at 37°C for 20-30 minutes.

- Organoid Culture: Overlay the polymerized droplets with a defined culture medium optimized for the tissue of origin. This medium typically includes a cocktail of growth factors, agonists (e.g., Wnt agonists, R-spondin), and inhibitors (e.g., TGF-β inhibitor) to support stem cell maintenance and organoid growth [35].

- Maintenance and Expansion: Culture the organoids at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium should be refreshed every 2-3 days. For passaging (every 1-2 weeks), dissociate organoids using mechanical disruption or gentle enzymatic treatment and re-embed the fragments/cells into fresh matrix.

- Cryopreservation: For biobanking, dissociate organoids, mix with cryoprotectant solution (e.g., containing DMSO), and freeze slowly before transferring to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage [35].

Protocol 2: High-Content Analysis of Drug Response in 3D Cultures

Quantifying drug response in 3D models requires specialized imaging and analysis. This protocol leverages high-content confocal imaging [37]:

- Model Preparation: Establish 3D models (spheroids or organoids) in optically clear, black-walled 96- or 384-well plates suitable for imaging.

- Compound Treatment: Treat models with a dilution series of chemogenomic compounds or chemical probes. Include appropriate controls (vehicle and positive cytotoxicity controls). Incubation times may vary from 72 hours to 7 days based on the model and target.

- Staining: At assay endpoint, stain live cells with a nuclear dye (e.g., H2B-GFP, Hoechst) and a viability indicator (e.g., DRAQ7, propidium iodide). Alternatively, fix and permeabilize cultures for immunostaining of specific markers (e.g., cleaved caspase-3 for apoptosis, Ki-67 for proliferation).

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution z-stack images of each organoid using an automated confocal or high-content microscope. A minimum of 10-20 organoids per condition is recommended for robust statistics.

- Image Analysis: Use 3D analysis software to quantify parameters at both the cellular and organoid level:

- Organoid-level: Measure total volume, sphericity, and ellipticity.

- Cell-level: Quantify total live cell count (H2B-GFP+/DRAQ7-), dead cell count (DRAQ7+), and specific biomarker intensities.

- Data Analysis: Calculate growth rates based on live cell count or volume over time (if using live imaging) or determine IC50 values from dose-response curves. Compare morphological changes (e.g., loss of sphericity) to distinguish cytostatic from cytotoxic effects [37].

Diagram: PDTO Screening Workflow. The end-to-end process for establishing Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids (PDTOs) and utilizing them in a high-content drug screening pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

The successful implementation of advanced 3D models relies on a suite of specialized reagents and technologies. The following table details key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced 3D Models

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Provides a physiologically relevant 3D scaffold for cell growth and organization; rich in extracellular matrix proteins like laminin and collagen [35] [32]. | Matrigel, Cultrex BME, synthetic hydrogels. Lot-to-lot variability is a key consideration [35] [31]. |

| Defined Culture Media | Supports the growth and maintenance of stem cells and their differentiated progeny within organoids; often requires tissue-specific cytokine/growth factor cocktails [35]. | Commercially available organoid media or lab-formulated mixes containing R-spondin, Noggin, Wnt agonists, etc. [35]. |

| Low-Adhesion Plates | Promote the self-assembly of cells into 3D spheroids by preventing attachment to the plastic surface; often feature round or v-shaped bottoms [31]. | Ultra-low attachment (ULA) spheroid microplates. Essential for scaffold-free spheroid formation [31] [30]. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Dyes | Enable real-time, non-invasive monitoring of cell viability, death, and other dynamic processes within 3D structures during drug treatment [37]. | Nuclear labels (H2B-GFP, Hoechst), viability indicators (DRAQ7, Calcein AM), and tetrazolium-based assays (CCK-8, MTS) [37]. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopes capable of capturing high-resolution z-stack images of 3D models, enabling quantitative analysis of complex phenotypes [37]. | Confocal or spinning disk systems coupled with advanced 3D image analysis software (e.g., from ImageJ, CellProfiler, or commercial platforms) [37]. |

The integration of advanced disease models like 3D primary cultures and patient-derived organoids into phenotypic screening platforms marks a significant leap forward in preclinical research. By offering unparalleled physiological relevance and patient specificity, these models bridge the critical gap between traditional 2D cell cultures and clinical outcomes. For research focused on both chemogenomic compounds and chemical probes, the strategic selection and application of these models—guided by the specific screening objective—enable more accurate efficacy assessment, better prediction of drug resistance, and the development of truly personalized therapeutic strategies. As protocols become standardized and technologies like AI-driven image analysis mature, these 3D models are poised to fundamentally accelerate the drug discovery pipeline and improve its success rate [36] [38] [33].

Phenotypic screening, an empirical strategy for interrogating incompletely understood biological systems, has led to novel biological insights and first-in-class therapies [21]. This approach allows researchers to identify compounds that produce a measurable effect on cells or organisms without prior bias toward a specific protein target, keeping proteins in their native environment and enabling the discovery of compounds with unprecedented targets or novel mechanisms of action [39]. However, a significant challenge in phenotypic screening remains the translation of compound-induced phenotypes into well-defined cellular targets and modes of action [39].

The integration of transcriptomics and proteomics technologies has revolutionized phenotypic screening by enabling deep phenotypic profiling at multiple molecular layers. This multi-omics approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of cellular responses to chemical probes and chemogenomic compounds by capturing both genetic regulatory programs and their functional protein effectors. While transcriptomics reveals RNA expression patterns and alternative splicing events, proteomics delivers crucial information about the actual executors of cellular functions—proteins—including their abundance, post-translational modifications, and interactions [40] [41]. This synergistic combination allows researchers to move beyond superficial phenotypic observations to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms, significantly accelerating both target identification and validation in modern drug discovery.

Technology Comparison: Transcriptomics vs. Proteomics in Phenotypic Screening

Fundamental Principles and Measurement Approaches

Transcriptomics involves systematically investigating RNA transcripts produced by the genome and how these transcripts are altered in response to regulatory processes. As the bridge between genotype and phenotype, transcriptomic analysis provides insights into gene expression regulation, alternative splicing, and non-coding RNA functions [41]. Key technologies include RNA microarrays, next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods such as Illumina-based RNA-Seq, and third-generation sequencing platforms like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) that offer long-read capabilities for improved isoform detection [40].

Proteomics focuses on the large-scale study of proteins, their structures, functions, and dynamics. The proteome is highly dynamic, as proteins can be modified in response to internal and external cues, with different proteins produced as circumstances change [41]. Mass spectrometry (MS) represents the core technological platform for proteomics, with Orbitrap, FT-ICR, and MALDI-TOF-TOF instruments providing high-resolution protein identification and quantification [40]. Advanced tandem MS techniques including CID, ECD, ETD, and EID enable detailed characterization of post-translational modifications and protein structures [40].

Table 1: Core Technology Comparison for Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis

| Feature | Transcriptomics | Proteomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Analytical Platforms | Next-generation sequencing, microarrays | Mass spectrometry, antibody arrays |

| Readout Information | RNA abundance, splice variants, fusion transcripts, novel transcripts | Protein abundance, post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions |

| Temporal Resolution | Minutes to hours | Hours to days |

| Coverage Depth | ~20,000 coding genes | ~10,000-15,000 proteins (typical profiling) |

| Key Advantages | Sensitive detection of low-abundance transcripts, comprehensive isoform information | Direct measurement of functional effectors, post-translational modification information |

| Primary Limitations | Poor correlation with protein abundance, misses regulatory events at protein level | Limited dynamic range, more complex sample preparation |

Performance in Gene Function Prediction and Coexpression Analysis

Comparative analyses reveal fundamental differences in the biological information captured by transcriptomic and proteomic profiling. A systematic investigation constructing gene coexpression networks from matched mRNA and protein profiling data for breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancers demonstrated that protein coexpression was driven primarily by functional similarity between coexpressed genes, while mRNA coexpression was influenced by both cofunction and chromosomal colocalization of the genes [42].

This study found that proteome profiling strengthened the link between gene expression and function for at least 75% of Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes and 90% of KEGG pathways, demonstrating that proteomics outperforms transcriptomics for coexpression-based gene function prediction [42]. Functionally coherent mRNA modules were more likely to have their edges preserved in corresponding protein networks than functionally incoherent mRNA modules, suggesting that protein coexpression networks provide more reliable information for inferring gene function from expression data.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Between Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling

| Performance Metric | Transcriptomics | Proteomics | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Similarity Prediction | Moderate (driven by cofunction + chromosomal colocalization) | High (primarily driven by functional similarity) | Coexpression network analysis across 3 cancer types [42] |

| Connection to Pathway Annotations | 75% of GO processes strengthened with proteomics | 90% of KEGG pathways strengthened vs. transcriptomics | Gold standard gene pairs based on GO semantic similarity [42] |

| Single-Cell Clustering Performance (ARI) | scDCC: 0.781, scAIDE: 0.773, FlowSOM: 0.770 | scAIDE: 0.795, scDCC: 0.789, FlowSOM: 0.785 | Benchmarking of 28 algorithms on 10 paired datasets [43] |

| Technology Reproducibility | Pearson correlation: 0.983-0.997 (MHCC97H cell line) | Pearson correlation: 0.966-0.988 (DDA), 0.970-0.994 (DIA) | Multi-omics dataset stability assessment across generations [44] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Phenotypic Screening

The following workflow diagram illustrates a standardized pipeline for integrating transcriptomic and proteomic profiling in phenotypic screening campaigns:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Transcriptomic Profiling Protocol

For comprehensive transcriptome analysis in phenotypic screening applications, the following standardized protocol is recommended:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate total RNA using TRIzol-based methods, ensuring RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.5 for sequencing applications. Treat samples with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination [44].

Library Preparation: Utilize stranded mRNA-seq library preparation kits with poly-A selection for coding transcript analysis. Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias and enable accurate digital counting of transcripts.