Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling in 2025: How NGS is Powering the Next Generation of Drug Discovery

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemical-genetic interaction profiling, providing an unparalleled high-throughput lens to decipher how small molecules affect biological systems.

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling in 2025: How NGS is Powering the Next Generation of Drug Discovery

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemical-genetic interaction profiling, providing an unparalleled high-throughput lens to decipher how small molecules affect biological systems. This article offers researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a comprehensive guide, from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications. It explores how NGS enables the systematic identification of drug targets and mechanisms of action, details robust methodological workflows for profiling, provides actionable strategies to overcome common data analysis bottlenecks, and validates NGS approaches against traditional methods. By synthesizing these core intents, this article serves as a critical resource for leveraging NGS to accelerate and refine the drug discovery pipeline.

The NGS Revolution: Foundational Principles for Decoding Chemical-Genetic Landscapes

The systematic elucidation of gene function and chemical mechanism of action (MOA) has been revolutionized by fitness-based interaction profiling, a method that quantifies how genetic perturbations alter susceptibility to chemical compounds or other environmental stresses [1]. At the heart of this transformative approach lies the continuous evolution of DNA sequencing technologies, which have progressed from Frederick Sanger's chain-termination method to today's massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms [2] [3]. This technical evolution has enabled unprecedented scalability in profiling chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs), allowing researchers to simultaneously assess thousands of compound-by-mutant combinations in pooled formats [1] [4]. The recent introduction of Roche's Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology promises to further accelerate this field by addressing fundamental limitations in signal detection and processing [5] [6] [7]. Within the context of a broader thesis on NGS for chemical-genetic interaction profiling research, this review examines the technical progression of sequencing technologies that underpin this powerful discovery platform, with particular emphasis on their application in drug discovery and functional genomics.

The Sequencing Technology Landscape: From First to Next-Generation

Sanger Sequencing: The Foundational Technology

Sanger sequencing, developed in 1977, established the principle of chain termination using dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) to halt DNA synthesis at specific bases [3] [8]. This method involves a DNA polymerase reaction incorporating fluorescently-labeled ddNTPs alongside normal dNTPs, generating DNA fragments of varying lengths that are separated by capillary electrophoresis to determine the sequence [8]. Despite its relatively low throughput, Sanger sequencing maintains relevance as a gold standard for validation due to its exceptional accuracy (exceeding 99.99%) and long read lengths (800-1000 bp) [3] [8]. In chemical-genetic interaction studies, it serves primarily for confirming critical hits or validating constructs, while NGS handles the high-throughput discovery screening [8].

Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms

The emergence of NGS in the early 21st century introduced massively parallel sequencing, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing costs [2]. These technologies can be broadly categorized by their underlying biochemistry:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Sequencing Technologies

| Technology | Sequencing Principle | Amplification Method | Read Length | Key Applications in Interaction Profiling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger | Chain termination | PCR | 800-1000 bp | Target validation, confirmatory sequencing [3] [8] |

| Illumina | Sequencing by synthesis | Bridge PCR | 36-300 bp | Genome-wide mutant barcode sequencing [2] [1] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | Emulsion PCR | 200-400 bp | Targeted interaction screens [2] |

| PacBio SMRT | Real-time sequencing | None | 10,000-25,000 bp | De novo genome assembly for model organisms [2] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore conductance | None | 10,000-30,000 bp | Direct RNA sequencing, large structural variants [2] |

| Roche SBX | Expansion & nanopore | None | Not specified | Emerging technology for future profiling applications [5] [7] |

Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis has become the dominant platform for chemical-genetic interaction profiling due to its high accuracy and capacity for multiplexing thousands of samples in a single run [2] [1]. The technology utilizes fluorescently-labeled reversible terminator nucleotides imaged during incorporation on clonally-amplified DNA clusters [2]. This approach enables the highly parallel quantification of genetic barcodes from pooled mutant collections exposed to various compounds [1].

Emerging technologies like Pacific Biosciences' Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore sequencing offer distinctive advantages for specific applications. PacBio provides exceptionally long reads valuable for de novo genome assembly of model organisms used in screening [2]. Oxford Nanopore's protein nanopores detect nucleotide sequences through changes in ionic current as DNA or RNA molecules pass through, enabling direct RNA sequencing and detection of epigenetic modifications [2].

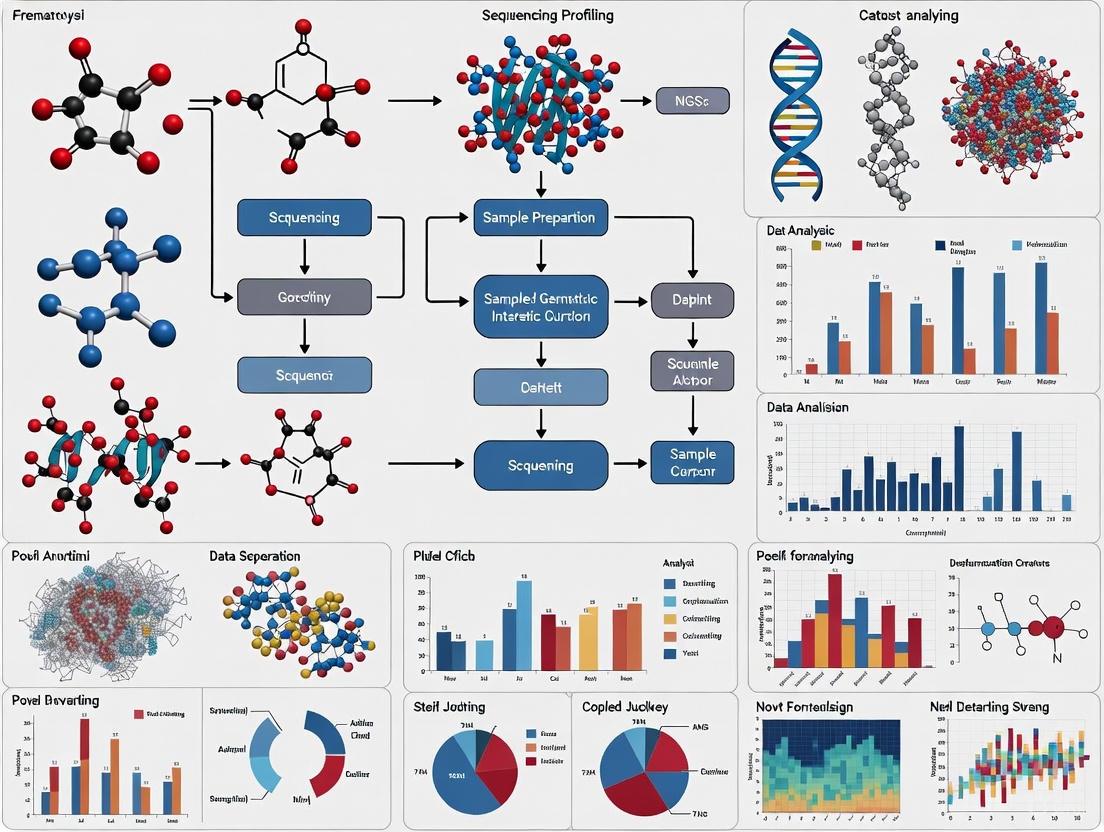

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary relationships and core technological principles of major sequencing platforms:

Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling: A Technical Workflow

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling represents a powerful application of NGS technology that enables systematic mapping of functional relationships between genes and small molecules [1] [4]. The core methodology involves monitoring the fitness of a pooled collection of genetically barcoded mutants under chemical perturbation, with NGS enabling massively parallel quantification of strain abundances [1].

Experimental Protocol for High-Throughput Profiling

The PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform exemplifies a sophisticated implementation of this approach for antibiotic discovery in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4]. The detailed methodology comprises:

Strain Pool Preparation: A collection of hypomorphic M. tuberculosis strains, each engineered for proteolytic depletion of an essential gene and tagged with unique DNA barcodes, is pooled to create the screening library [4].

Chemical Perturbation: The pooled mutant library is exposed to chemical compounds in 96- or 384-well microtiter plates, with each well representing a unique compound-dose combination. Negative control conditions (DMSO-only) are included for baseline comparison [1] [4].

Competitive Growth: Cultures undergo competitive growth for a defined period (typically 48-72 hours), during which strains hypersensitive to specific compounds become depleted in the pool [4].

Barcode Amplification and Sequencing: Genetic barcodes are amplified using indexed primers, creating PCR amplicons that uniquely identify both the mutant strain and experimental condition. These are multiplexed in a single Illumina sequencing run [1] [4].

Data Processing with BEAN-counter: The Barcoded Experiment Analysis for Next-generation sequencing (BEAN-counter) pipeline processes raw sequencing data to quantify barcode abundances, remove low-quality mutants/conditions, and compute interaction z-scores for each mutant-condition pair [1].

Mechanism of Action Prediction: The Perturbagen CLass (PCL) analysis method compares CGI profiles of unknown compounds to a curated reference set of compounds with annotated MOAs, enabling target prediction [4].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process of chemical-genetic interaction profiling:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Mutant Collections | Provides uniquely tagged strains for pooled screening | S. cerevisiae deletion collection (≈4,000 mutants) [1]; M. tuberculosis hypomorph collection (≈600 essential genes) [4] |

| Indexed PCR Primers | Enables multiplexed sequencing of barcodes from different conditions | Illumina-compatible primers with unique index sequences for each sample [1] |

| BEAN-counter Software | Processes raw sequencing data into interaction scores | Python-based pipeline for barcode quantification, normalization, and z-score calculation [1] |

| Reference Compound Set | Enables mechanism of action prediction | Curated collection of 437 compounds with annotated MOAs for M. tuberculosis [4] |

| KAPA Library Preparation Kits | Optimized reagents for NGS library construction | Roche's KAPA products for high-performance DNA and RNA library prep [7] |

Roche's SBX Technology: A Potential Paradigm Shift

Roche's Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology represents a novel approach that addresses fundamental signal-to-noise challenges in DNA sequencing [6] [7]. Developed by Mark Kokoris and commercialized following Roche's acquisition of Stratos Genomics in 2020, SBX introduces a unique biochemical process that encodes target DNA sequence information into synthetic surrogate polymers called Xpandomers [6] [7].

Technical Principles of SBX

The SBX method employs a sophisticated two-component system:

Xpandomer Synthesis: Through a proprietary biochemical process, SBX converts native DNA into Xpandomers—expanded surrogate polymers that are approximately fifty times longer than the original DNA molecule. These Xpandomers encode the sequence information into high signal-to-noise reporters, providing clearer signals with minimal background noise [6] [7].

CMOS-Based Detection: The Xpandomers are sequenced using a Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS)-based sensor module with nanopore detection. This combination enables highly accurate single-molecule sequencing with parallel processing capabilities [7] [9].

The key innovation lies in solving the signal-to-noise challenge that has limited previous sequencing technologies. By creating expanded molecules with larger reporter elements, SBX enhances detection clarity while maintaining sequencing accuracy [6]. This approach enables ultra-rapid, high-throughput sequencing that is both flexible and scalable across different project sizes [7].

Potential Applications in Chemical-Genetic Profiling

While SBX technology is newly unveiled in 2025, its technical capabilities suggest significant potential for chemical-genetic interaction profiling:

Accelerated Screening Cycles: The ultra-rapid sequencing capabilities could reduce the time from sample preparation to genomic analysis from days to hours, potentially increasing screening throughput [7].

Enhanced Multiplexing Capacity: The scalable architecture using CMOS sensor modules may enable processing of larger mutant collections or more complex experimental designs [7] [9].

Integrated Workflows: Compatibility with Roche's AVENIO Edge automated library preparation system could streamline entire profiling workflows from sample to analysis [7].

The progression from Sanger sequencing to NGS platforms has fundamentally transformed chemical-genetic interaction profiling from a targeted, small-scale approach to a comprehensive, systems-level discovery tool. The integration of massively parallel sequencing with pooled mutant screening has enabled the systematic mapping of gene function and compound mechanism of action at unprecedented scale [1] [4]. Emerging technologies like Roche's SBX promise to further accelerate this field by addressing core limitations in signal detection and processing speed [7] [9]. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new dimensions in our understanding of biological systems and enhance our ability to develop targeted therapeutics for complex diseases. The ongoing integration of these technological advances with sophisticated computational methods like BEAN-counter and PCL analysis represents a powerful paradigm for functional genomics and drug discovery in the coming decade [1] [4].

Chemical-genetic interaction (CGI) profiling represents a powerful systems biology approach that quantifies how genetic alterations modulate cellular responses to chemical compounds. When integrated with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, this method enables high-throughput dissection of compound mechanisms of action (MOA) at unprecedented scale and resolution. This synergy is particularly transformative in antimicrobial discovery, where understanding how small molecules inhibit pathogenic organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is crucial for overcoming drug resistance [4]. The core principle hinges on a simple but profound biological observation: mutants partially depleted of essential gene products (hypomorphs) exhibit heightened sensitivity to compounds that target the corresponding gene product, its pathway, or functionally related processes [4]. NGS acts as the engine for phenotypic readout, precisely measuring the fitness of each mutant in a pooled library under chemical treatment by quantifying the change in abundance of DNA barcodes unique to each strain [4] [10]. This technical guide explores the core concepts, methodologies, and applications of CGI profiling within the broader context of leveraging NGS for modern chemical-genetics research.

Core Principles and Definitions

What is a Chemical-Genetic Interaction?

A chemical-genetic interaction occurs when the effect of a chemical compound on a cell is modulated by a specific genetic alteration. In a typical screening setup, this is measured as a significant deviation in the fitness of a mutant strain compared to a wild-type control when exposed to the compound.

In essential gene knockdowns (hypomorphs), a negative CGI (fitness defect) often suggests the compound's mechanism of action directly or indirectly involves the depleted gene product. The resulting CGI profile for a compound—a vector of fitness scores across hundreds of mutants—serves as a unique, high-dimensional fingerprint that can be used to predict its MOA [4] [11].

The Role of NGS in Phenotypic Readouts

Next-generation sequencing provides the multiplexing capability required to scale CGI profiling to genome-wide levels. Unlike microarray-based detection or manual colony counting, NGS enables the simultaneous tracking of thousands of bacterial mutants in a single pooled experiment through the quantification of unique DNA barcodes associated with each strain [4] [10] [12].

The process, often referred to as Transposon Insertion Sequencing (TnSeq) in prokaryotic systems, involves sequencing the inserts of a saturated transposon mutant library after competitive growth under chemical stress. The change in frequency of each mutant, represented by its barcode count, is calculated as a log~2~ fold change (LFC) or related Z-score, quantifying its relative sensitivity or resistance to the compound [10] [11]. This NGS-based readout provides the quantitative data that forms the basis for all subsequent MOA analysis.

Key Experimental Platforms and Workflows

The PROSPECT Platform for Targeted Screening

A prime example of a focused CGI platform is PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets). This platform is designed for high-sensitivity primary compound screening while simultaneously providing MOA insights [4].

- Library Design: PROSPECT utilizes a pooled library of M. tuberculosis hypomorphs, each engineered to be proteolytically depleted of a different essential protein. Each strain is tagged with a unique DNA barcode.

- Screening Process: The pooled library is exposed to a chemical compound. Hypomorphs whose depleted proteins are functionally related to the compound's target often show hypersensitivity.

- NGS Readout: Genomic DNA is extracted from the pool before and after compound exposure. The abundance of each barcode is quantified via NGS, generating a fitness profile for the compound across all hypomorphs [4].

Diagram: PROSPECT Screening Workflow

Genome-Wide TnSeq for Unbiased Discovery

For an unbiased, genome-wide survey of intrinsic resistance factors, TnSeq-based CGI profiling is employed. This method uses a highly complex library of random transposon mutants, offering near-complete coverage of non-essential genes and essential gene domains [10].

- Library Construction: A Mariner-based transposon library is created with ~10^5^ unique mutants in M. tuberculosis, achieving approximately 65% coverage of possible insertion sites [10].

- Selection and Sequencing: The library is grown in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of an antibiotic. Genomic DNA is isolated, and the transposon-genome junctions are amplified and sequenced using NGS.

- Data Analysis: Specialized software like TRANSIT analyzes sequence reads to calculate the log~2~ fold change in abundance for each mutant (LTnSeq-FC). A negative LTnSeq-FC indicates a mutant with increased sensitivity, pointing to a gene involved in intrinsic resistance [10].

Data Analysis and MOA Prediction Methods

Reference-Based MOA Prediction with PCL Analysis

Perturbagen CLass (PCL) analysis is a computational reference-based method to infer a compound's MOA by comparing its CGI profile to a curated database of profiles from compounds with known MOAs [4].

- Curated Reference Set: A reference set is assembled, containing hundreds of compounds with published, annotated MOAs (e.g., inhibitors of cell wall synthesis, DNA replication, or respiration).

- Similarity Scoring: The CGI profile (Z-scores or LFCs across all mutant strains) of an uncharacterized compound is compared to every profile in the reference set using similarity metrics.

- MOA Assignment: The compound is assigned the MOA of the reference compound(s) with the most similar profile. This method achieved 69% sensitivity and 87% precision when validating against a set of known GlaxoSmithKline antitubercular compounds [4].

Diagram: PCL Analysis Workflow for MOA Prediction

Deep Learning for CGIP-Based MOA Prediction

Advanced computational methods now leverage graph-based deep learning to predict MOAs directly from chemical structures and CGI profiles (CGIPs) [11].

- Input Representation: Molecular structures are represented as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) or via fingerprints (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints).

- Model Architecture: A Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) is used to learn features from the molecular graph. These features are used to predict bioactivity against predefined clusters of functionally related genes.

- Gene Clustering: To improve model efficiency and biological interpretability, genes are first clustered into groups based on the biological similarity of their products, often using homology information from well-annotated model organisms like E. coli [11].

- Output: The model outputs a multi-label prediction, indicating which gene clusters (and thus which biological processes) a compound is likely to inhibit.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The performance of NGS-based CGI profiling is quantified through its accuracy in predicting known biological mechanisms and its ability to identify novel targets.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Reference-Based MOA Prediction (PCL Analysis)

| Validation Set | Sensitivity | Precision | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-one-out cross-validation | 70% | 75% | Validated on a curated reference set of 437 known molecules [4] |

| Independent test set (GSK compounds) | 69% | 87% | 75 compounds with known MOA; 29 of 60 predicted QcrB inhibitors validated [4] |

Table 2: Key Quantitative Features in CGI Profile Analysis

| Data Feature | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Log~2~ Fold Change (LFC) | Log~2~ ratio of mutant abundance in treated vs. control samples [11] | Negative LFC indicates hypersensitivity; positive LFC indicates resistance |

| Wald Test Z-score | LFC divided by its standard error [11] | More significant growth inhibition is indicated by smaller (more negative) Z-scores |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) q-value | Corrected p-value accounting for multiple hypothesis testing [10] | q < 0.05 typically signifies a statistically significant chemical-genetic interaction |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of NGS-based CGI profiling requires a suite of specialized biological and computational reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CGI Profiling

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic Mutant Library | Collection of strains with inducible depletion of essential genes; each has a unique DNA barcode [4] | Core screening reagent for targeted platforms like PROSPECT |

| Saturated Transposon Mutant Library | Complex library of random transposon insertions for genome-wide screening [10] | Used in TnSeq for unbiased discovery of intrinsic resistance factors |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares pooled barcode or transposon amplicons for high-throughput sequencing | Must be compatible with the sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent) [2] |

| TRANSIT Software | Open-source computational pipeline for TnSeq data analysis [10] | Identifies conditionally essential genes and significant fitness defects |

| Curated MOA Reference Database | Collection of CGI profiles from compounds with validated mechanisms of action [4] | Essential for reference-based prediction methods like PCL analysis |

The integration of chemical-genetic interaction profiling with next-generation sequencing has created a robust framework for elucidating the mechanism of action of small molecules directly in a physiologically relevant, whole-cell context. Platforms like PROSPECT and TnSeq provide complementary strengths, enabling both targeted, high-sensitivity screening and unbiased genome-wide discovery. The resulting high-dimensional CGI profiles serve as rich functional fingerprints, which can be deciphered using computational methods ranging from reference-based similarity matching (PCL analysis) to advanced graph neural networks. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, becoming faster, more accurate, and more cost-effective, their application in chemical genetics will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of biological systems and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics, particularly against recalcitrant pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Why NGS? Advantages in Throughput, Cost, and Sensitivity for High-Throughput Screening

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research by providing unparalleled capabilities for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner. [2] This transformative technology has swiftly propelled genomics advancements across diverse domains, but its impact is particularly profound in the field of chemical-genetic interaction (CGI) profiling. In contrast to first-generation Sanger sequencing, which sequences only a single DNA fragment at a time, NGS is massively parallel, sequencing millions of fragments simultaneously per run. [13] This fundamental difference in scale has established NGS as the technological backbone for sophisticated research methodologies like the PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets (PROSPECT) platform, which leverages CGI profiling to elucidate small molecule mechanism of action (MOA) in complex biological systems such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. [4]

For researchers investigating chemical-genetic interactions, NGS provides three decisive advantages over conventional sequencing: unmatched throughput that enables comprehensive profiling of entire mutant libraries, superior sensitivity for detecting subtle phenotypic changes across genetic variants, and dramatically lower cost-per-sample that makes large-scale screens financially feasible. This technical guide examines these advantages in detail, provides experimental frameworks for implementation, and demonstrates how NGS-powered platforms are accelerating drug discovery through rapid MOA identification.

Core Advantages of NGS in Screening Applications

Unmatched Throughput and Scalability

The massively parallel nature of NGS enables screening capabilities that are simply unattainable with traditional sequencing methods. Where Sanger sequencing interrogates a single gene or small genomic region, targeted NGS can simultaneously sequence hundreds to thousands of genes across numerous samples. [13] This scalability is critical for chemical-genetic interaction studies, which require monitoring thousands of genetic perturbations in response to chemical treatments.

Table 1: Throughput Comparison Between Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Targeted NGS |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Scale | Single DNA fragment at a time | Millions of fragments simultaneously [13] |

| Typical Read Depth | 50-100 reads per sample [13] | Tens to hundreds of thousands of reads per sample [13] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | High (multiple samples pooled in one run) [13] |

| Genes Interrogated | 1-20 targets cost-effectively [13] | Hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously [13] |

| Application in CGI | Low throughput, limited discovery power | Comprehensive mutant library profiling |

Enhanced Sensitivity and Discovery Power

NGS provides significantly greater sensitivity for detecting multiple variants across targeted genomic regions. The high sequencing depth achievable with NGS enables detection of low-frequency variants with limits of detection down to 1%, a crucial capability for identifying rare genetic interactions or minor subpopulations in heterogeneous samples. [13] Furthermore, NGS offers greater discovery power—the ability to identify novel variants—and higher mutation resolution that can identify everything from large chromosomal rearrangements down to single nucleotide variants. [13]

In chemical-genetic interaction profiling, this enhanced sensitivity allows researchers to detect even subtle hypersensitivity responses in hypomorphic strains, enabling the discovery of active small molecules that would elude conventional wild-type screening. [4] The PROSPECT platform leverages this capability to identify compounds with previously undetectable activity by measuring minute changes in hypomorph abundance through NGS-based barcode quantification. [4]

Cost-Effectiveness for Large-Scale Studies

While Sanger sequencing remains cost-effective for interrogating small regions (1-20 targets), NGS becomes increasingly economical as scale increases. [13] The paradigm of "do more with less" has been extremely impactful across the research community, enabling more 'omics' data to be generated with higher quality at lower cost. [14] A systematic review of NGS cost-effectiveness in oncology found that targeted panel testing (2-52 genes) reduces costs compared to conventional single-gene assays when four or more genes require testing. [15]

Table 2: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of NGS vs. Single-Gene Testing

| Testing Scenario | Cost-Effectiveness Outcome | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| 1-3 genes | Single-gene testing generally more cost-effective [15] | Lower direct testing costs for simple assays |

| 4+ genes | Targeted NGS panels more cost-effective [15] | Efficiency of simultaneous testing |

| Holistic analysis | NGS consistently provides cost savings [15] | Reduced turnaround time, staff requirements, hospital visits |

| Large panels (hundreds of genes) | Generally not cost-effective for routine use [15] | Higher reagent and analysis costs |

NGS-Driven Methodologies for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

Experimental Workflow for PROSPECT-Based Screening

The PROSPECT platform represents a cutting-edge application of NGS for chemical-genetic interaction profiling. This systems chemical biology strategy couples small molecule discovery to MOA information by screening compounds against a pooled library of hypomorphic Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains, each engineered to be proteolytically depleted of a different essential protein. [4] The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Diagram 1: PROSPECT Workflow for MOA Identification. This NGS-based approach identifies chemical-genetic interactions by quantifying barcode abundances from pooled hypomorphic strains after small molecule treatment.

Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Based Screening

Successful implementation of NGS-based chemical-genetic interaction profiling requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for establishing these screening platforms:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-Based Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Experimental Workflow | Application in CGI Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Hypomorphic Strain Library | Engineered mutants with depleted essential proteins; sensitized background for detecting chemical interactions [4] | Core component of PROSPECT platform; enables detection of compound hypersensitivity |

| DNA Barcodes | Unique nucleotide sequences that tag each strain for multiplexed tracking [4] | Enables quantification of strain abundance in pooled screens via NGS |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Reagents for fragmenting DNA/RNA, adding adapters, and preparing sequencing libraries [2] | Processes barcode amplicons for high-throughput sequencing |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Probes to enrich specific genomic regions of interest; reduce sequencing costs [15] | Focuses sequencing on barcode regions; improves efficiency and cost-effectiveness |

| Automated Liquid Handling | Robotics for consistent sample and reagent dispensing in high-throughput formats [16] | Enables screening of thousands of compound-dose conditions with minimal variability |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Computational tools for processing raw NGS data, variant calling, and interaction scoring [2] [14] | Converts sequencing data into chemical-genetic interaction profiles and MOA predictions |

Application in Drug Discovery: From CGI Profiling to Mechanism of Action

Reference-Based MOA Prediction Using PCL Analysis

The true power of NGS in chemical-genetic interaction profiling emerges when the massive datasets are analyzed using sophisticated computational approaches. Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis represents a reference-based method that infers a compound's mechanism of action by comparing its chemical-genetic interaction profile to those of a curated reference set of known molecules. [4] In practice, researchers have achieved 70% sensitivity and 75% precision in MOA prediction using leave-one-out cross-validation with a reference set of 437 compounds with annotated MOAs. [4]

This approach demonstrates how NGS-derived CGI profiles serve as fingerprints of chemical perturbations, enabling rapid classification of novel compounds without requiring complete understanding of all biological interactions within the cell. The methodology has successfully identified novel inhibitors targeting QcrB, a subunit of the cytochrome bcc-aa3 complex involved in respiration, including the validation of a pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold that initially lacked wild-type activity but was optimized through chemistry efforts to achieve potent antitubercular activity. [4]

Integration with Multiomics and AI for Enhanced Discovery

The future of NGS in chemical-genetic interaction profiling lies in its integration with multiomic datasets and artificial intelligence. The year 2025 is expected to mark a revolution in genomics, driven by the power of multiomics—the integration of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic data from the same sample—and AI-powered analytics. [14] This synergy enables researchers to unravel complex biological mechanisms, accelerating breakthroughs in rare diseases, cancer, and infectious disease research.

AI and machine learning are having a profound impact on the NGS field by helping accelerate biomarker discovery, identify new pathways for drug development, and offer a more defined path toward precision medicine. [14] The intersection of NGS and AI/ML is becoming critical for generating the large datasets required to drive AI-scale breakthroughs, for which the cost and quality of sequencing data will be paramount. [14]

Next-Generation Sequencing has established itself as an indispensable technology for high-throughput screening applications, particularly in the realm of chemical-genetic interaction profiling. The trifecta of advantages—massive parallelization, exceptional sensitivity, and compelling cost-effectiveness at scale—positions NGS as the foundational technology for platforms like PROSPECT that aim to accelerate drug discovery through early MOA identification. As NGS technologies continue to evolve toward long-read sequencing, single-molecule resolution, and tighter integration with multiomics and AI, their impact on understanding chemical-biological interactions will only intensify. For researchers investigating the complex interplay between small molecules and cellular networks, NGS provides the technological framework to move beyond simple potency measurements toward truly mechanism-driven discovery paradigms.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized pharmaceutical research by providing powerful, high-throughput methods to elucidate the complex interactions between chemicals and biological systems. By enabling the detailed profiling of chemical-genetic interactions (CGIs), NGS technologies allow researchers to systematically identify drug targets, decipher mechanisms of action (MOA), and uncover resistance pathways with unprecedented scale and precision [4] [16]. This technical guide explores the core applications of NGS in chemical-genetic interaction profiling, providing methodologies, data interpretation frameworks, and essential tools for researchers in drug discovery and development.

Core Concepts of Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling is a powerful systems biology approach that quantifies how genetic alterations modulate the sensitivity of cells to chemical compounds. The core principle is that strains of an organism, each with a different mutated or depleted essential gene, will show differential fitness—hypersensitivity or resistance—when treated with a small molecule. The pattern of these fitness changes across a comprehensive library of mutants, known as the chemical-genetic interaction profile, serves as a unique fingerprint that can reveal the biological pathways affected by the compound [4] [10].

The advent of NGS has been pivotal to this field. It allows for the simultaneous quantification of the abundance of thousands of unique mutants within a pooled screening culture by sequencing DNA barcodes associated with each mutant. This provides a highly sensitive, quantitative, and comprehensive readout of CGI profiles [4] [10]. Platforms like Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis and PacBio's single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing are commonly employed for their high accuracy and throughput [2].

Application 1: Uncovering Novel Drug Targets

A primary application of NGS-based CGI profiling is the de novo identification of novel drug targets. This is achieved by screening compounds against a comprehensive library of hypomorphic (gene-knockdown) mutants. When a mutant with reduced levels of a specific essential protein is hypersensitive to a compound, it strongly suggests that the compound's target is either that protein, a member of its pathway, or a functionally related pathway [4].

The PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a leading example. PROSPECT uses a pooled library of hypomorphic Mtb mutants, each depleted of a different essential protein. The screening readout is a vector of chemical-genetic interactions that can pinpoint the compound's target directly or through pathway context [4].

Case Study: Discovery of a Novel QcrB Inhibitor From a screen of ~5,000 compounds, a novel pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold was identified. Its CGI profile showed high similarity to known inhibitors of the cytochrome bcc-aa₃ complex, a key component in the respiratory chain. The QcrB subunit was predicted as the target. This prediction was subsequently validated by demonstrating that the compound lost activity against strains with a resistant qcrB allele and showed increased activity against a mutant lacking the alternative cytochrome bd oxidase, a hallmark of QcrB inhibitors [4].

Application 2: Elucidating Mechanism of Action

Rapid and accurate mechanism of action (MOA) determination is a major bottleneck in drug discovery. NGS-based CGI profiling addresses this through reference-based computational approaches. The core idea is that compounds with similar MOAs will produce similar CGI profiles. By comparing the profile of an uncharacterized compound to a curated reference set of profiles from compounds with known MOAs, the MOA of the unknown compound can be inferred [4].

Perturbagen CLass (PCL) Analysis This computational method, developed for PROSPECT data, infers a compound's MOA by comparing its CGI profile to a reference set of 437 known molecules. The performance of this approach is robust, as demonstrated in the table below [4].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of PCL Analysis for MOA Prediction

| Validation Method | Sensitivity | Precision | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leave-one-out cross-validation | 70% | 75% | Internal validation with curated reference set |

| Independent test set | 69% | 87% | 75 antitubercular compounds from GSK |

In a practical application on 98 uncharacterized antitubercular compounds from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), PCL analysis assigned putative MOAs to 60 compounds. Twenty-nine of these, predicted to target bacterial respiration, were functionally validated [4].

Application 3: Deciphering Antimicrobial Resistance Pathways

Understanding intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms is critical for combating drug-resistant infections. NGS-based CGI profiling can systematically identify genes that, when mutated, confer increased sensitivity or resistance to an antimicrobial, thus revealing the genetic basis of intrinsic resistance and potential targets for combination therapy [10] [17].

TnSeq for Intrinsic Resistance Determinants A study using Transposon Insertion Sequencing (TnSeq) in Mtb identified mutants with altered fitness under sub-inhibitory concentrations of five antibiotics. The screen identified 251 mutants with significant fitness changes, revealing the cell envelope as a major determinant of antibiotic susceptibility. The analysis identified 17 genes linked to intrinsic resistance to at least 4 of the 5 antibiotics tested. A key finding was FecB, a gene not involved in iron acquisition as previously thought, but a critical mediator of general cell envelope integrity; its mutation led to hypersensitivity to all five antibiotics tested [10].

Table 2: Key Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance Genes Identified by TnSeq in M. tuberculosis

| Gene | Function | Antibiotic Sensitivity Profile | Validated Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| fecB | Putative iron dicitrate-binding protein | Rifampin, Isoniazid, Ethambutol, Vancomycin, Meropenem | Cell envelope integrity |

| lcp1 | Peptidoglycan-arabinogalactan ligase | Multiple antibiotics | Cell wall synthesis |

| mmaA4 | Mycolic acid synthase | Multiple antibiotics | Mycolic acid synthesis |

| secA2 | Protein translocase | Multiple antibiotics | Protein export |

| caeA/hip1 | Cell envelope-associated protease | Multiple antibiotics | Envelope protein homeostasis |

NGS is also instrumental in identifying resistance mechanisms in cancer. For instance, in HER2-positive gastric cancer, NGS analysis of patient tumors revealed that specific genetic alterations like ERBB2 L755S mutation, CDKN2A insertions, and RICTOR amplification were enriched in patients who did not respond to trastuzumab, uncovering potential drivers of primary resistance [18].

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Workflow

The following detailed protocol outlines a standard workflow for NGS-based chemical-genetic interaction screening, drawing from established methods in mycobacterial research [4] [10].

Stage 1: Library Preparation and Screening

- Pooled Mutant Library Construction: Generate a comprehensive mutant library. For Mtb, this can be a saturated transposon mutant library (e.g., ~10⁵ unique Mariner transposon mutants) or a pooled collection of hypomorphic strains (as in PROSPECT), each with a unique DNA barcode [4] [10].

- Compound Treatment: Inoculate the pooled library into culture medium and divide it into treatment and control arms. Expose the treatment arm to a pre-determined, partially inhibitory concentration of the test compound (causing a 25-40% reduction in overall growth). The control arm grows in the absence of the compound [10].

- Competitive Outgrowth: Allow both cultures to grow for a set number of generations (e.g., ~6.5 generations, resulting in a 100-fold population expansion) to enable fitness differences between mutants to become apparent [10].

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Barcode Amplification: Harvest cells from both cultures. Extract genomic DNA and use PCR to amplify the unique barcodes from each mutant with primers that also add Illumina sequencing adapters [4] [19].

Stage 2: Sequencing and Data Analysis

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Pool the amplified barcode libraries from control and treated samples and sequence them on an NGS platform such as an Illumina NextSeq or NovaSeq, following color balance best practices to ensure high-quality data [4] [20].

- Sequence Alignment and Quantification: Demultiplex the sequencing reads and map them to a reference file of known barcodes to obtain a count for each mutant in the control and treated samples [19].

- Fitness Calculation: For each mutant, calculate a fitness score. This is typically the Log₂ Fold Change (LTnSeq-FC) in its abundance in the treated library compared to the control library. A negative score indicates hypersensitivity, while a positive score indicates resistance [10].

- Statistical Analysis: Use specialized software like TRANSIT (for TnSeq data) to perform statistical testing (e.g., resampling or ZINB methods) to identify mutants with fitness scores that are significantly different from the neutral expectation [10].

Stage 3: Interpretation and Target Prediction

- Profile Generation and Clustering: Compile the significant fitness scores for all mutants into a single CGI profile for the compound. Use hierarchical clustering to compare and group compounds with similar profiles [10].

- Reference-Based MOA Prediction: Compare the compound's CGI profile to a curated reference database of profiles from compounds with known MOAs using a method like PCL analysis to generate a hypothesis about its MOA [4].

- Functional Validation: Conduct downstream experiments to confirm the predicted target or MOA. This may include:

- MIC Shift Assays: Determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against individual deletion mutants predicted to be hypersensitive [10].

- Resistance Mutant Isolation: Generate spontaneous resistant mutants and sequence their genomes to identify mutations in the putative target gene [4].

- Biochemical Assays: Demonstrate direct binding or inhibition of the purified target protein [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Kits for NGS-Based CGI Profiling

| Item | Function | Example Product/Source |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares DNA barcodes for sequencing by adding adapters and indices. | Illumina DNA Prep [17] |

| Targeted Sequencing Panel | For focused sequencing of resistance genes or specific genomic regions. | AmpliSeq for Illumina Antimicrobial Resistance Panel (targets 478 AMR genes) [17] |

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Kits | Allows multiplexing of many samples by tagging each with a unique barcode pair, minimizing index hopping. | Illumina UD Index Plates, NEXTFLEX UDI Adapters [20] |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Kit | For comprehensive genome analysis to identify resistance mutations in evolved strains. | Illumina Microbial WGS solutions [17] [21] |

| TnSeq Analysis Software | Statistical tool for identifying essential genes and conditionally important genes from TnSeq data. | TRANSIT [10] |

The integration of NGS into chemical-genetic interaction profiling has created a powerful, data-driven pipeline for modern drug discovery and development. By systematically linking chemical perturbations to genetic backgrounds, this approach accelerates the identification of novel targets, deconvolutes the mechanism of action of new chemical entities, and reveals the complex networks underlying drug resistance, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective therapeutics.

From Cells to Data: Methodological Workflows and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research by providing unprecedented capacity to analyze genetic material in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [2]. In the specific context of chemical-genetic interaction profiling, which seeks to understand how genetic background influences response to chemical compounds, the choice of sequencing approach is paramount. Each method—whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and targeted sequencing—offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully balanced against research goals, resources, and analytical capabilities [22] [23] [24]. This technical guide provides a structured framework for selecting the optimal NGS approach to illuminate the complex relationships between genetics and chemical response, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development.

Technical Comparison of NGS Approaches

The three primary NGS approaches interrogate different portions of the genome with varying levels of comprehensiveness and resolution. Understanding their technical specifications is the first step in experimental design.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of WGS, WES, and Targeted Sequencing

| Parameter | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Entire genome (coding + non-coding) [24] [25] | Protein-coding exons only (~2% of genome) [23] [24] | Selected genes/regions of interest [22] [25] |

| Approximate Region Size | 3 Gb (human) [23] | ~30 Mb [23] | Tens to thousands of genes [23] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | > 30X [23] | 50-150X [23] | > 500X [23] |

| Data Output per Sample | > 90 GB [23] | 5-10 GB [23] | Varies, but significantly less than WES [24] |

| Detectable Variants | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Structural Variants, Fusions [23] | SNPs, InDels, some CNVs, Fusions [23] | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions [23] |

Table 2: Strategic Advantages and Limitations in Drug Research Context

| Aspect | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strengths | Most comprehensive view; detects variants in regulatory regions and structural variants; enables novel discovery [24] [25]. | Cost-effective for coding regions; high depth on known disease-associated areas; simpler data analysis [22] [24]. | Highest depth for sensitive mutation detection; most cost-effective for focused questions; simplest data handling [22] [25]. |

| Key Limitations | Highest cost; massive data storage/analysis challenges; may generate more false positives for low-frequency variants [22] [24]. | Misses non-coding and regulatory variants; low sensitivity for structural variants; coverage uniformity issues [22] [24]. | Limited to pre-defined genes; impossible to re-analyze for genes not on the panel after sequencing [22]. |

| Ideal for Drug Discovery Phase | Target identification & novel biomarker discovery [16] [26]. | First-tier test for rare diseases and validating targets in coding regions [22] [21]. | Patient stratification, therapy selection, and pharmacogenomics in clinical trials [27] [16]. |

Experimental Design Framework

Selecting the optimal sequencing approach requires a systematic evaluation of the research objective. The following decision framework and workflow can guide this process.

Defining the Research Objective

The first step is to articulate the precise scientific question, as this directly dictates the most suitable NGS method.

- Target Identification and Novel Biomarker Discovery: If the goal is to uncover novel genetic associations with drug response, including variations in non-coding regulatory regions, promoter sites, or intergenic regions that might influence gene expression, WGS is the unequivocal choice [16] [26]. Its unbiased nature allows for hypothesis-free exploration, which is critical in the early stages of discovery.

- Validation and Association in Coding Regions: For studies focused on validating targets where the hypothesis is confined to protein-altering variants, or for large-cohort association studies where cost-effectiveness is key, WES provides an optimal balance of comprehensiveness and practicality [22] [24]. It is particularly powerful for rare disease diagnosis and identifying pathogenic coding variants linked to drug efficacy or adverse events [22].

- Clinical Diagnostics and High-Throughput Screening: When the application demands high-throughput, cost-effective screening of specific gene sets—such as in patient stratification for clinical trials, companion diagnostic development, or monitoring minimal residual disease—targeted panels are the most efficient tool [27] [16] [21]. Their high depth allows for sensitive detection of low-frequency variants in a defined genetic space.

Practical Considerations and Constraints

Beyond the research question, several practical factors critically influence the decision.

- Budget and Resources: The total cost includes not only sequencing but also data storage, transfer, and computational analysis. WGS generates data an order of magnitude larger than WES, requiring significant investment in bioinformatics infrastructure and expertise [22] [24]. Targeted panels minimize these downstream costs.

- Data Analysis Expertise: The complexity of data analysis escalates from targeted panels to WES to WGS. Interpreting non-coding variants from WGS remains particularly challenging due to insufficient research on these regions [22] [28]. The availability of bioinformatics support is a crucial deciding factor.

- Sample Throughput and Timelines: For studies requiring rapid turnaround on hundreds or thousands of samples, the streamlined data analysis of targeted panels and, to a lesser extent, WES, offers a significant logistical advantage over WGS.

Methodologies for Key Experiments in Drug Development

The following section outlines detailed protocols for applying these NGS approaches to common scenarios in chemical-genetic interaction research.

Protocol 1: Unbiased Target Identification Using WGS

Objective: To identify novel genetic variants (SNPs, indels, SVs) across the entire genome associated with resistance or sensitivity to a lead compound [16] [26].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from case (e.g., drug-resistant cell lines or patient samples) and control (e.g., drug-sensitive) groups.

- Library Construction: Fragment DNA and prepare sequencing libraries using standard kits (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep). Avoid amplification if possible to reduce bias.

- Sequencing: Sequence on a platform capable of long-insert paired-end reads (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a minimum depth of 30X for confident variant calling and structural variant detection [23].

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Primary & Secondary Analysis: Perform quality control (FastQC), align reads to a reference genome (BWA-MEM), and call variants (GATK) for SNPs/indels. Use specialized tools (e.g., Manta, DELLY) for structural variant calling [28].

- Tertiary Analysis: Annotate variants (ANNOVAR, VEP). Integrate with functional genomics data (e.g., ChIP-Seq, ATAC-Seq) to prioritize non-coding variants affecting regulatory elements. Conduct pathway enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) to identify biological processes enriched for mutations in the case group.

Protocol 2: Profiling Coding Variants for Mechanism of Action Using WES

Objective: To comprehensively profile coding variants and expression changes in a large set of tumor samples to understand drug mechanism of action and identify patient subgroups [27] [21].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Extract DNA and RNA from matched tumor and normal samples (e.g., FFPE tissue).

- Library Preparation & Target Enrichment:

- For DNA: Prepare libraries and perform hybridization-based capture using a whole-exome probe set (e.g., Illumina Nexome, Roche KAPA HyperExome).

- For RNA: Prepare RNA-Seq libraries to correlate genetic variants with gene expression changes.

- Sequencing: Sequence to a high depth of coverage (>100X for DNA) to reliably detect somatic mutations present in a subpopulation of cells [23].

- Bioinformatics Analysis:

- DNA Analysis: Align sequences, call variants, and filter for somatic mutations by comparing tumor vs. normal. Focus on protein-coding consequences (missense, nonsense, splice-site).

- RNA Analysis: Align RNA-Seq reads, quantify gene expression (FPKM/TPM), and perform differential expression analysis between genetic subgroups.

- Integration: Correlate specific mutations with transcriptional profiles to infer pathway activation and propose drug combination strategies.

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Pharmacogenomic Screening Using Targeted Panels

Objective: To rapidly screen clinical trial participants for pre-defined pharmacogenomic markers that predict drug response or risk of adverse events [27] [16].

Workflow:

- Panel Selection: Choose a clinically validated targeted panel that encompasses genes relevant to the drug's metabolism (e.g., CYP450 family), mechanism of action, and known toxicity pathways.

- Library Preparation: Use a multiplex PCR or hybridization-based approach for target enrichment. This workflow is highly amenable to automation in 96- or 384-well plates.

- Sequencing: Sequence on a benchtop instrument (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) to a very high depth (>500X) to enable ultra-sensitive detection of low-allele-fraction variants [23].

- Bioinformatics & Reporting: Use a streamlined, validated bioinformatics pipeline for rapid turnaround. The analysis is focused on a shortlist of clinically actionable variants. Generate a clear report for each sample to guide patient stratification or dosing decisions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful execution of NGS experiments relies on a suite of trusted reagents, platforms, and software.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Experiments

| Category | Item | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep | KAPA HyperPrep Kit | Construction of sequencing-ready libraries from genomic DNA. |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina Nextera Flex for EnrichmentRoche KAPA HyperExome Probe Panels | Hybridization-based capture of whole exome or custom gene panels. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq & MiSeqPacBio Sequel & OnsoOxford Nanopore PromethION | High-throughput short-read, accurate long-read, and real-time sequencing, respectively [2]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Illumina DRAGEN PlatformGATKANNOVAR | Accelerated secondary analysis; variant calling and filtering; functional annotation of variants [21] [28]. |

| Data Management | DNAnexus, Seven Bridges Genomics | Cloud-based platforms for secure, scalable, and reproducible NGS data analysis [28]. |

The strategic selection between WGS, WES, and targeted sequencing is a cornerstone of effective experimental design in chemical-genetic interaction research. WGS offers an unparalleled comprehensive view for discovery, WES provides a cost-effective balance for coding region analysis, and targeted panels deliver precision and depth for applied clinical questions. By aligning the research objective with the technical capabilities and practical constraints of each method, scientists can robustly profile genetic interactions with chemical compounds, thereby de-risking and accelerating the entire drug development pipeline. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational tools become more sophisticated, the integration of these multi-scale genomic approaches will undoubtedly yield deeper insights and more personalized therapeutic interventions.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, providing a high-throughput, cost-effective method for deciphering genetic information [12]. This technical guide details the core Illumina NGS workflow, a foundational technology enabling sophisticated research approaches such as chemical-genetic interaction (CGI) profiling, which is critical for elucidating small molecule mechanisms of action in drug discovery [4].

Library Preparation: From Sample to Sequence-Ready Fragments

Library preparation is the critical first step that converts a generic nucleic acid sample into a platform-specific, sequence-ready library [29]. This process ensures that DNA or RNA fragments can be efficiently recognized and sequenced by the NGS instrument.

Detailed Methodology

The standard library preparation protocol involves a series of enzymatic and purification steps [29] [30]:

- Fragmentation: Isolated genomic DNA is fragmented into smaller, manageable pieces. This can be achieved through:

- Physical Methods: Such as sonication (using sound waves) or acoustic shearing.

- Enzymatic Methods: Using transposases that simultaneously fragment and tag the DNA with adapter sequences, streamlining the workflow. The optimal fragment size range is typically 100–800 base pairs, depending on the application [30].

- Adapter Ligation: Special oligonucleotide sequences, known as adapters, are ligated to both ends of the fragmented DNA. These adapters are multifunctional [30]:

- Platform Binding: Contain sequences complementary to the oligonucleotides bound on the flow cell.

- Sequencing Primers: Provide the binding sites for the primers used in the sequencing-by-synthesis reaction.

- Sample Indexing: Include unique molecular barcodes (indexes) that allow multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a single run (multiplexing), then computationally separated after sequencing.

- Library Amplification & Quality Control: The adapter-ligated fragments are amplified by PCR to generate a sufficient quantity of the library for sequencing. Finally, the prepared library is quantified using methods like fluorometry or qPCR to ensure optimal loading onto the sequencer [29].

Diagram: The NGS Library Preparation Workflow

Application in Chemical-Genetic Profiling

In CGI profiling studies like the PROSPECT platform, library preparation is performed not on the human genome, but on the DNA barcodes of a pooled microbial mutant library [4]. Each mutant strain, engineered with a unique DNA barcode, is pooled and subjected to a small molecule. After exposure, genomic DNA is extracted, and the barcode regions are specifically amplified and prepared for NGS. The change in abundance of each barcode, measured by sequencing, reveals which genetic mutants are most sensitive or resistant to the compound, providing a "fitness profile" that serves as a fingerprint for its mechanism of action [4].

Cluster Generation: In Situ Amplification on the Flow Cell

Before sequencing can begin, the library must be clonally amplified to create strong enough signals for detection. On Illumina platforms, this is achieved through cluster generation on a flow cell [29].

Detailed Methodology: Bridge Amplification

The process of bridge amplification occurs on a glass flow cell coated with oligonucleotides complementary to the library adapters [29].

- Loading and Annealing: The diluted library is loaded onto the flow cell. Single-stranded DNA fragments from the library bind randomly to the complementary primers on the flow cell surface.

- Bridge Formation and Amplification: The flow cell is flooded with enzymes and nucleotides for PCR. The bound template bends over and "bridges" to an adjacent complementary primer on the flow cell surface, forming a double-stranded bridge.

- Denaturation and Cycling: The double-stranded bridge is denatured, leaving two single-stranded copies attached to the flow cell. This process repeats over many cycles, with each copy creating new bridges with nearby primers, ultimately amplifying a single original fragment into a dense, clonal cluster containing millions of identical copies.

Diagram: Cluster Generation via Bridge Amplification

Sequencing by Synthesis: The Core Imaging Technology

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) is the biochemistry that enables the simultaneous, massive parallel sequencing of all clusters on the flow cell [29] [12]. Illumina's method utilizes fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides.

Detailed Methodology: Cyclic Reversible Termination

The SBS process is a cyclic, automated process occurring inside the sequencer [29]:

- Nucleotide Incorporation: All four fluorescently labeled dNTPs (each with a distinct color) are flowed into the flow cell simultaneously. Each nucleotide also contains a reversible terminator, which blocks the addition of the next nucleotide after a single base is incorporated. DNA polymerase adds a single nucleotide to each growing DNA strand complementary to the template.

- Imaging: After incorporation, unincorporated nucleotides are washed away. The flow cell is then imaged with lasers. The fluorescent color detected at each cluster identifies the base that was just incorporated.

- Cleavage: The fluorescent dye and the terminator group are chemically cleaved from the nucleotide, leaving a native DNA strand and removing the block to further synthesis.

- Cycle Repetition: Steps 1-3 are repeated "n" times to achieve a read length of "n" bases. This cyclic process generates millions of short sequences, or "reads," in parallel.

Diagram: Sequencing by Synthesis Chemistry

Application in Chemical-Genetic Profiling

In the PROSPECT platform, SBS is used to quantitatively sequence the DNA barcodes from the pooled mutant library [4]. The raw output is a digital count of reads per barcode, which is proportional to the abundance of that mutant in the pool after compound treatment. By comparing barcode counts from compound-treated samples to untreated controls, a quantitative chemical-genetic interaction profile is generated for each small molecule. Computational methods like Perturbagen Class (PCL) analysis then compare these profiles to a reference database of compounds with known mechanisms to predict the target of uncharacterized molecules [4].

Quantitative Data and Platform Comparisons

The NGS workflow generates massive amounts of data. Key quantitative metrics and a comparison of sequencing technologies are summarized below.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Outputs from an NGS Run

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Length of a single DNA fragment read. | 36-300 bp (Short-Read) [2] |

| Read Depth | Number of times a genomic region is sequenced. | Varies by application (e.g., 30x for WGS) |

| Throughput | Total data generated per run. | 300 kilobases to multiple Terabases [12] |

| Accuracy | Raw accuracy per base. | >99.9% (Q30 score) [30] |

| Q30 Score | Quality score indicating a 0.1% error rate. | Industry standard for high-quality data [30] |

Table 2: Comparison of Short-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Amplification Type | Read Length (bp) | Key Limitations [2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis | Bridge PCR | 36-300 | Overcrowding can spike error rate to ~1% |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor (H+ detection) | Emulsion PCR | 200-400 | Signal degradation with homopolymer sequences |

| 454 Pyrosequencing | Pyrosequencing (PPi detection) | Emulsion PCR | 400-1000 | Insertion/deletion errors in homopolymers |

| SOLiD | Sequencing by Ligation | Emulsion PCR | 75 | Substitution errors, under-represents GC-rich regions |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the NGS workflow relies on a suite of specialized reagents and kits.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for NGS Workflows

| Item | Function | Application in Chemical-Genetic Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits | Extract high-quality, pure DNA/RNA from sample source. | Extracting genomic DNA from pooled microbial mutant cultures [4]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Fragment DNA/RNA and ligate platform-specific adapters. | Preparing sequencing libraries from amplified barcode regions [4]. |

| PCR Enzymes & Master Mixes | Amplify adapter-ligated libraries or specific target regions. | Amplifying mutant barcodes prior to library prep [29]. |

| Indexing (Barcoding) Oligos | Unique nucleotide sequences to tag individual samples. | Multiplexing hundreds of compound screens in a single sequencing run [30]. |

| Target Enrichment Probes | Biotinylated probes to capture genomic regions of interest. | Not typically used; PROSPECT relies on whole-barcode sequencing [4]. |

| Quality Control Kits | Fluorometric or qPCR-based kits for quantifying libraries. | Ensuring accurate library quantification before loading onto the flow cell [29]. |

| Sequencing Chemistries | Reagent kits containing enzymes and nucleotides for SBS. | Essential for all sequencing runs to generate the interaction profile data [12]. |

The standardized NGS workflow of library preparation, cluster generation, and sequencing by synthesis provides a powerful and reliable engine for modern genomics. By enabling the quantitative, parallel analysis of millions of DNA fragments, it forms the technological foundation for advanced research methodologies like chemical-genetic interaction profiling. This application directly accelerates drug discovery by providing deep mechanistic insights into compound action, facilitating the prioritization of hits, and guiding the development of novel therapeutics against critical targets such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4]. As NGS technology continues to evolve towards greater speed, lower cost, and longer reads, its impact on functional genomics and personalized medicine will only intensify.

The selection of an appropriate next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform is a critical decision that directly impacts the quality, depth, and applicability of data generated in chemical-genetic interaction profiling research. This field, which systematically explores how genetic perturbations influence cellular responses to chemical compounds, demands sequencing technologies that can deliver specific capabilities ranging from high accuracy to long read lengths. The current NGS landscape features established second-generation short-read technologies from Illumina, third-generation long-read platforms from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), and the emerging Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology from Roche. Each technology presents distinct trade-offs in terms of read length, accuracy, throughput, cost, and operational flexibility, making platform selection highly dependent on specific research objectives and experimental constraints.

Chemical-genetic interaction studies have been transformed by NGS, enabling high-throughput assessment of how chemical compounds affect pools of genetically barcoded mutants. Technologies such as QMAP-Seq (Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing) leverage Illumina-based sequencing to precisely measure how drug response changes across hundreds of genetic perturbations simultaneously [31]. Similarly, the PROSPECT platform (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) utilizes NGS to identify chemical-genetic interactions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by tracking the abundance of DNA barcodes in hypomorphic strains after compound treatment [4]. As these applications continue to evolve, understanding the technical capabilities and limitations of available sequencing platforms becomes essential for designing effective experiments and accurately interpreting results in chemical-genetic research.

Technology Comparison & Performance Metrics

Core Sequencing Technologies

Illumina technology employs sequencing-by-synthesis with bridge amplification, generating billions of short reads (typically 50-300 bp) with exceptional accuracy exceeding 99.9% [32]. This high accuracy makes it particularly suitable for applications requiring precise variant detection, such as single-nucleotide polymorphism identification in chemical-genetic interaction studies. However, its short read length presents challenges for resolving complex genomic regions or detecting large structural variations that may be relevant in drug response studies.

PacBio Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing generates long reads averaging 15-20 kb through its circular consensus sequencing (CCS) approach, which produces high-fidelity (HiFi) reads with accuracy exceeding 99.9% by repeatedly sequencing the same molecule [33] [32]. This combination of long reads and high accuracy enables precise resolution of complex genomic regions, making it valuable for identifying structural variants and haplotype phasing in chemical-genetic studies.

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) utilizes protein nanopores to sequence single DNA or RNA molecules in real-time as they pass through the pore, producing ultra-long reads that can exceed 100 kb [32]. While historically associated with higher error rates, recent improvements in chemistry (R10.4.1 flow cells) and basecalling algorithms have increased accuracy to over 99% [33]. The platform's ability to perform real-time sequencing and its extreme portability (particularly the MinION device) offer unique experimental flexibility.

Roche SBX (Sequencing by Expansion), scheduled for launch in 2026, represents a novel approach that converts DNA information into a longer "expanded" molecule (Xpandomer) before sequencing through proprietary nanopores [34] [35]. This technology is designed to offer a combination of high accuracy (>99.8% for SNVs), flexible read lengths (50bp to >1000bp), and very high throughput, potentially making it suitable for large-scale chemical-genetic interaction studies when it becomes commercially available [34].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Read Length | Accuracy | Throughput Range | Run Time | Key Applications in Chemical-Genetic Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 50-300 bp | >99.9% | 0.1M - 5B reads | 1-3.5 days | QMAP-Seq [31], PROSPECT [4], targeted NGS for drug resistance [36] |

| PacBio | 15-20 kb (HiFi) | >99.9% (HiFi) | 0.5-4M reads (Revio) | 0.5-30 hours | Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing [33], structural variant detection, haplotype phasing |

| Oxford Nanopore | Up to 100+ kb | >99% (latest) | 10-290 Gb (PromethION) | Real-time (minutes to days) | Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing [37], direct RNA sequencing, rapid diagnostics |

| Roche SBX | 50-1000+ bp | >99.8% (SNV) | Up to 5B duplex reads/hour | <5 hours (workflow) | Whole genome sequencing (planned) [34] [35], rapid clinical applications |

Table 2: Performance in Microbial Community Profiling (16S rRNA Sequencing)

| Platform | Target Region | Species-Level Classification Rate | Key Findings in Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | V3-V4 (300-600 bp) | 47-48% | Clear clustering by soil type except for V4 region alone (p=0.79) [33] |

| PacBio | Full-length (1.4 kb) | 63% | Comparable to ONT, slightly better at detecting low-abundance taxa [33] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Full-length (1.4 kb) | 76% | Highest species-level resolution despite higher error rate [37] |

Performance characteristics vary significantly across platforms depending on the specific application. In 16S rRNA sequencing for microbiome studies, which shares methodological similarities with barcode sequencing in chemical-genetic interaction profiling, ONT demonstrated the highest species-level classification rate at 76%, followed by PacBio at 63%, and Illumina at 47-48% [37]. Notably, a comparative study of soil microbiomes found that both PacBio and ONT provided comparable assessments of bacterial diversity, with PacBio showing slightly higher efficiency in detecting low-abundance taxa [33]. Importantly, the study demonstrated that regardless of the sequencing technology used, microbial community analysis ensured clear clustering of samples based on soil type, with the exception of the V4 region alone where no soil-type clustering was observed (p=0.79) [33].

Applications in Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling

Established Methodologies and Workflows

Chemical-genetic interaction profiling has emerged as a powerful strategy for elucidating compound mechanism of action and gene function. The QMAP-Seq (Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing) platform exemplifies how Illumina sequencing enables large-scale chemical-genetic studies in mammalian systems [31]. This approach leverages short-read sequencing to quantify the abundance of genetic barcodes in pooled cell populations following chemical treatment, generating precise quantitative measures of drug response across thousands of genetic perturbations simultaneously.

The typical QMAP-Seq workflow involves: (1) engineering barcoded cell lines with inducible genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 knockouts); (2) treating pooled cells with compound libraries across multiple doses; (3) preparing crude cell lysates with spike-in standards for quantification; (4) amplifying target barcodes with indexed primers for multiplexing; and (5) sequencing on Illumina platforms with a single-read strategy to capture sgRNA and cell line barcodes [31]. The resulting data enables quantification of chemical-genetic interactions through comparison of barcode abundances between treated and control samples, revealing both synthetic lethal and synthetic rescue interactions that provide insights into drug mechanism of action.

Similarly, the PROSPECT (PRimary screening Of Strains to Prioritize Expanded Chemistry and Targets) platform employs Illumina sequencing to identify chemical-genetic interactions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4]. This system screens compounds against a pool of hypomorphic Mtb strains, each depleted of a different essential protein, using NGS to quantify changes in strain-specific DNA barcodes after compound treatment. The resulting chemical-genetic interaction profiles serve as fingerprints for mechanism of action prediction through comparison to reference compounds with known targets.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Chemical-genetic interaction profiling workflow using NGS. This generalized workflow underpins platforms like QMAP-Seq [31] and PROSPECT [4].

Experimental Design & Implementation

Platform Selection Guidelines

Selecting the appropriate sequencing platform for chemical-genetic interaction research requires careful consideration of multiple experimental parameters. For large-scale chemical-genetic screens involving thousands of compound-genotype combinations, Illumina platforms offer the required throughput, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness for barcode sequencing applications [31] [4]. The high accuracy of Illumina sequencing (>99.9%) is particularly important for distinguishing subtle differences in barcode abundance that indicate chemical-genetic interactions.

For applications requiring long-range sequencing to resolve complex genomic regions or detect structural variants resulting from chemical treatments, PacBio HiFi reads provide the combination of length and accuracy needed [33] [32]. Similarly, when real-time analysis or rapid turnaround is critical for experimental decision-making, Oxford Nanopore platforms offer unique advantages due to their streaming data capabilities [32].

The emerging Roche SBX technology promises to deliver an exceptional combination of accuracy, speed, and throughput when it becomes commercially available, potentially enabling ultra-rapid chemical-genetic profiling for time-sensitive applications [34] [35]. Its demonstrated ability to generate variant call files in less than 5 hours could significantly accelerate therapeutic discovery pipelines.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical-Genetic Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Perturbation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, hypomorphic strains [4] [31] | Introduction of specific genetic modifications to test gene-compound interactions |