Chemical Genomic Screens in S. cerevisiae: A Comprehensive Guide to Deletion Library Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genomic screening using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion library, a foundational resource in functional genomics.

Chemical Genomic Screens in S. cerevisiae: A Comprehensive Guide to Deletion Library Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical genomic screening using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion library, a foundational resource in functional genomics. We explore the construction and design principles of the yeast deletion collection, detail step-by-step methodological workflows for high-throughput phenotypic screening, and address common troubleshooting challenges. Furthermore, we present a comparative analysis with modern CRISPR-Cas screening technologies, validating the enduring utility of deletion libraries while contextualizing them within the current genomic toolkit. This guide is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these powerful screens for gene function discovery, pathway mapping, and drug target identification.

The Yeast Deletion Collection: A Foundational Tool for Functional Genomics

Historical Context and Project Conception

The conception of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion project was a direct outcome of the pioneering yeast genome sequencing consortium of the late 1980s and early 1990s [1]. As the first complete eukaryotic genome sequence neared fulfillment, a pressing need emerged to assign biological function to the multitude of newly discovered genes revealed by the sequencing effort [1]. The yeast deletion collection, often termed the Yeast KnockOut (YKO) set, was conceived to address this fundamental challenge, representing the first and only complete, systematically constructed deletion collection for any organism [1]. Its development provided an unprecedented functional genomics resource that would later become foundational for chemical genomic screening, enabling researchers to systematically identify gene function and gene-compound interactions on a genome-wide scale [1] [2].

Historical Development of the Yeast Deletion Collection

Project Inception and Execution

The ambitious vision for a complete yeast deletion collection confronted significant funding obstacles, requiring a creative solution from its principal investigators, Davis and Johnston [1]. They secured separate grants totaling approximately $2.3 million USD over three years, launching the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project [1]. The project employed a PCR-based, microhomology-mediated recombination strategy to efficiently generate precise start-to-stop codon deletions [1]. The technical execution proceeded in three distinct rounds, with successive rounds addressing problematic deletions from previous rounds, ultimately achieving a remarkable success rate of over 97% for targeted open reading frames (ORFs) [1].

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Yeast Deletion Project

| Year | Milestone | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| ~1998 | Project Launch | Funding secured from multiple grants; systematic construction begins [1]. |

| 1999 | Early Collection | Initial description of the deletion collection and its barcoding strategy published [2]. |

| 2002 | Project Completion | Collection finalized with ~6000 ORFs deleted; strains made available to community [1]. |

| 2014 | Widespread Adoption | Over 1000 genome-wide screens performed using the collection, demonstrating massive utility [1]. |

Strain Engineering and Barcoding Innovation

A critical design feature of the collection was the use of the S288c strain background, ensuring consistency with the reference genome sequence [1]. Each deletion strain was engineered by replacing a target ORF with a KanMX cassette, which confers resistance to the antibiotic G418 [1]. The most transformative innovation, however, was the incorporation of unique, 20-base-pair molecular "barcodes" flanking the deletion cassette [1] [2]. These barcodes, later augmented with both "Up" and "Down" tags to hedge against synthesis errors, served as unique strain identifiers [1]. This design enabled the application of oligonucleotide microarray technology to quantitatively measure the relative abundance of each mutant strain in a pooled culture through parallel amplification and hybridization of these barcodes, making large-scale fitness profiling feasible [3] [2].

Conceptual Foundation of Chemical Genomic Screening

The yeast deletion collections provided the essential physical reagent that enabled the development of chemical genomic screens. These screens operate on the principle that observing which gene deletion strains are most sensitive or resistant to a compound reveals the compound's mechanism of action and the biological pathways it perturbs [2] [4]. The core methodologies that emerged are:

- Homozygous Profiling (HOP): Screens the pool of ~4,800 haploid strains with deletions of non-essential genes. Sensitive mutants are depleted from the pool over time in the presence of a compound [3] [2].

- Heterozygous Profiling (HIP): Screens the pool of ~1,100 diploid strains, each heterozygous for a deletion of an essential gene. Reduced dosage of a drug target can confer hypersensitivity, helping to identify the protein target of a compound [3] [2].

- Differential Chemical Genetics: A screening method, applicable in various organisms, that compares the growth responses of two different genotypes (e.g., wild-type vs. a specific mutant) to identify compounds that induce genotype-specific phenotypes [5].

Table 2: Core Chemical Genomic Screening Methodologies

| Method | Strain Pool | Key Application | Example Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous Profiling (HOP) | ~4,800 haploid non-essential deletion strains [3]. | Identify pathways buffering the cell against compound-induced stress [2]. | Mutants in RIM101 pathway show extreme fitness defects against antimicrobial peptides [3]. |

| Heterozygous Profiling (HIP) | ~1,100 diploid heterozygous essential gene deletion strains [3]. | Identify potential protein targets of inhibitory compounds [2]. | Heterozygous mutation in ERG11 mimics effect of fluconazole [4]. |

| High-Throughput Profiling | Diagnostic subset of ~300 strains in sensitized background [4]. | Rapid, functional annotation of large compound libraries [4]. | 768-plex barcode sequencing to profile hundreds of compounds simultaneously [4]. |

The power of this approach was elegantly demonstrated in a study screening four different cationic antimicrobial peptides (MUC7 12-mer, histatin 12-mer, KR20, and hLF1-11) [3]. Despite structural differences, their chemical-genetic fitness profiles were highly similar, revealing a shared cellular response and implicating the RIM101 signaling pathway—which regulates response to alkaline pH—in the protective response against these peptides [3].

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Genomic Fitness Screen

The following protocol details a standard method for conducting a chemical-genetic fitness screen using a pooled deletion collection, based on established methodologies [3] [4].

Reagents and Equipment

- Yeast Pools: Frozen stocks of the homozygous non-essential deletion pool and/or heterozygous essential deletion pool.

- Growth Medium: Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB) or appropriate synthetic medium.

- Compound Solution: Compound of interest dissolved in suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO, water).

- DNA Isolation Kit: Kit for genomic DNA extraction from yeast.

- PCR Reagents: Taq polymerase, dNTPs, and primers for amplification of the molecular barcodes.

- Microarray Scanner or Sequencer: Depending on the detection method (e.g., Axon GenePix 4200AL scanner for microarrays or NGS platform for sequencing) [3].

Procedure

- Inoculation and Growth: Thaw frozen stock of the mutant pool and grow overnight in standard SDB medium.

- Compound Treatment: Dilute the overnight culture to an OD600 of ~0.05 in fresh, diluted medium (e.g., 1/2SDB) containing a predetermined concentration of the test compound. The concentration should inhibit wild-type growth by 20-50% [3]. Include a no-compound control.

- Pooled Competition: Grow the culture for multiple cycles (e.g., 2-4 cycles of 24 hours each) with periodic dilution to maintain logarithmic growth. This ensures sufficient time for fitness differences to manifest [3] [4].

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells from both the treated and control cultures at the end-point and extract genomic DNA.

- Barcode Amplification: Perform an asymmetric PCR to amplify the unique Up and Down barcodes from the genomic DNA. The primers used should flank the barcode sequences and can include adapters for downstream detection [3].

- Barcode Quantification and Normalization:

- Microarray Method: Hybridize the amplified barcode products to a custom oligonucleotide tag array. Scan the array and use software (e.g., NimbleScan) to obtain raw intensity values. Quantile normalize the data and calculate the treated/control intensity ratio for each barcode [3].

- Sequencing Method: Use high-throughput sequencing to count barcodes. Normalize sequence counts and calculate a fold-change for each strain [4].

- Fitness Score Calculation: For each strain, compute a fitness score as the log₂-transformed mean of the normalized ratios from its Up and Down tags. A positive score indicates hypersensitivity (fitness defect), while a negative score indicates resistance (fitness gain) [3].

Data Analysis

- Hit Selection: Apply a threshold to identify significant chemical-genetic interactions (e.g., fitness score >1 for hypersensitivity; < -1 for resistance) [3].

- Functional Enrichment: Subject the list of sensitive/resistant mutants to Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis to identify biological processes, molecular functions, or cellular compartments over-represented among the hits [3].

- Profile Comparison: Compare the chemical-genetic interaction profile of your compound to a compendium of genetic interaction profiles or other chemical-genetic profiles to infer the mode of action [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genomic Screens

| Research Reagent | Function and Application in Screens |

|---|---|

| YKO Collection | The core resource; complete set of barcoded deletion strains for genome-wide fitness profiling [1] [2]. |

| KanMX Cassette | The dominant selectable marker used to replace each ORF, conferring resistance to G418 for strain selection and maintenance [1]. |

| Molecular Barcodes (Up/Down Tags) | Unique 20-mer DNA sequences that serve as strain-specific identifiers, enabling parallel quantification of strain abundance in pooled assays via microarrays or sequencing [3] [1]. |

| Drug-Sensitized Strains | Engineered backgrounds (e.g., pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ) that enhance sensitivity to compounds, increasing assay hit rates and signal strength [4]. |

| Diagnostic Mutant Subset | A curated pool of ~300 non-essential deletion mutants that retains predictive power for functional annotation while enabling highly multiplexed screening [4]. |

| Tag Microarrays / NGS | Platforms for detecting and quantifying barcode abundances from pooled screens, translating population dynamics into quantitative fitness data [3] [4]. |

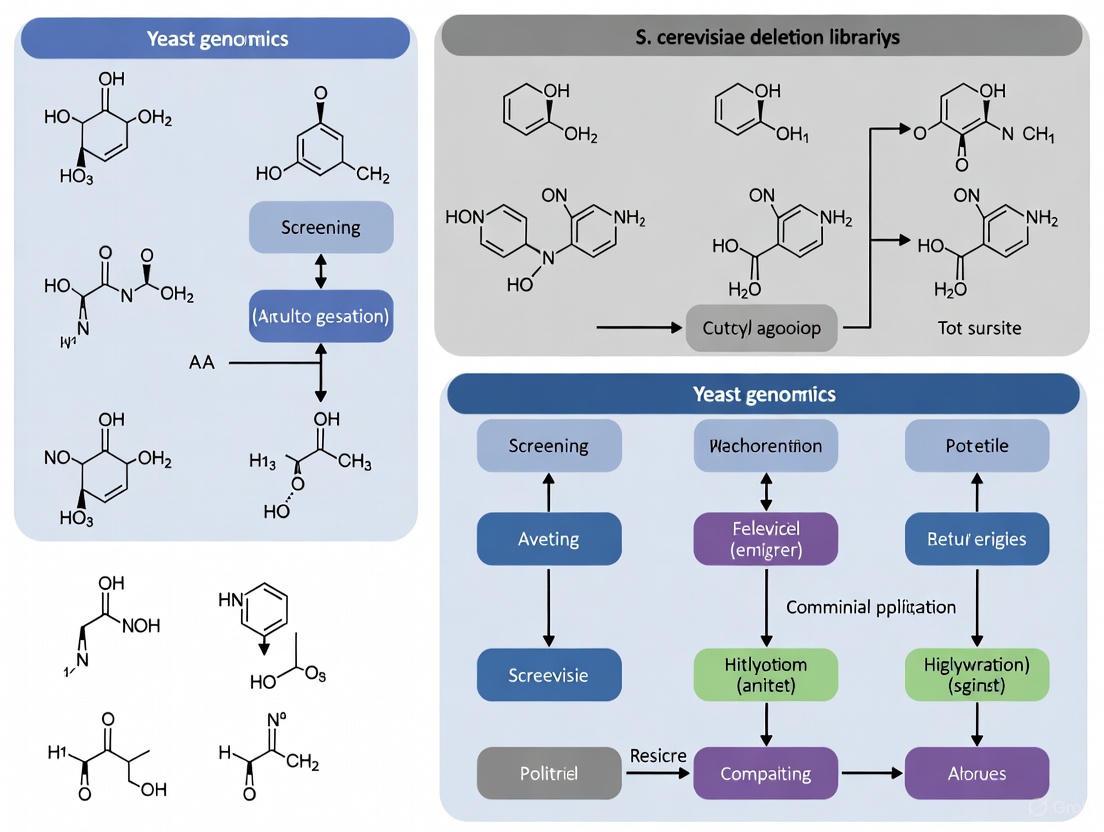

Visualizing the Screening Workflow and RIM101 Pathway

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow of a chemical genomic screen and a key signaling pathway frequently identified in such screens.

Chemical Genomic Screen Workflow

RIM101 Pathway in Stress Response

Chemical genomic screens in S. cerevisiae deletion libraries are powerful tools for discovering genotype-phenotype relationships and identifying drug targets. These screens involve systematically testing how a chemical compound affects a comprehensive collection of yeast deletion mutants. The yeast deletion collection, a pioneering whole-genome knockout library in S. cerevisiae, enables high-throughput functional genomic screens by allowing researchers to identify genes essential for survival under specific conditions, such as drug treatment or various stress factors [6].

The core of this methodology relies on using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to amplify unique molecular barcodes embedded in each deletion strain. These barcodes allow for the precise identification and tracking of individual mutants within a pooled culture, enabling the quantitative assessment of each mutant's fitness in the presence of a bioactive compound. This protocol details the application of PCR, barcode verification, and subsequent analysis within the context of chemical genomic screening.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required for the execution of PCR and barcode verification in chemical genomic screens.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for PCR and Barcode Verification

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae Deletion Collection | A pooled library of yeast strains, each with a specific gene deletion tagged with unique upstream and downstream molecular barcodes (UPTAG and DNTAG) [6]. |

| PCR Reagents | Includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, magnesium chloride, and reaction buffer for the amplification of barcode sequences from genomic DNA [7]. |

| Barcoded Primers | Sequence-specific primers designed to amplify the unique molecular barcodes from the deletion library. A universal forward primer and a mix of barcode-specific reverse primers are often used. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | For the isolation of high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA from the pooled yeast culture after chemical treatment. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kit | For the high-throughput parallel sequencing of amplified barcodes to quantify mutant abundance [7]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Tools for mapping sequenced barcodes to reference databases (e.g., BOLD, GenBank) to identify the corresponding deletion strain and quantify fitness [7]. |

Quantitative Data and Specifications

The table below summarizes the key quantitative aspects and specifications for the major steps in the workflow.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Specifications for PCR and Barcode Verification

| Parameter | Specification / Typical Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Barcode Length | ~20 nucleotides | Standardized short sequences for unique strain identification [7]. |

| PCR Cycle Number | 25-35 cycles | Optimized to prevent amplification bias and remain in the exponential phase. |

| Contrast Ratio for Diagrams | ≥ 4.5:1 | Minimum for standard text and graphical objects in diagrams to ensure accessibility [8]. |

| NGS Read Depth | 100-200 reads per barcode | Ensures sufficient coverage for accurate quantification of each mutant in the pool. |

| Fitness Score Calculation | Log₂(Fold Change) | Calculated by comparing barcode abundance in treated vs. control samples. |

Experimental Protocol

Genomic DNA Extraction from Pooled Yeast Culture

Principle: To isolate pure genomic DNA from the pooled S. cerevisiae deletion library after exposure to a chemical compound or control condition.

Procedure:

- Culture Harvesting: Grow the pooled deletion library in appropriate media with (test) and without (control) the chemical compound. Harvest cells by centrifugation during the mid-logarithmic growth phase.

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in a lysis buffer containing a lytic enzyme (e.g., zymolyase) to break down the cell wall.

- DNA Purification: Use a commercial DNA extraction kit. This typically involves:

- Proteinase K treatment to digest proteins.

- Binding of DNA to a silica membrane column.

- Washing with ethanol-based buffers to remove contaminants.

- Elution of pure genomic DNA in nuclease-free water or elution buffer.

- DNA Quantification: Measure the DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop) or fluorometer. Assess purity by the A260/A280 ratio (target ~1.8).

PCR Amplification of Molecular Barcodes

Principle: To specifically amplify the unique UPTAG and DNTAG sequences from the purified genomic DNA, incorporating platform-specific sequencing adapters.

Reaction Setup:

- Template DNA: 10-100 ng of purified genomic DNA.

- Primers: A mix of universal and barcode-specific primers. Modern approaches often use a single primer pair that flanks the barcode region and adds full NGS adapter sequences.

- PCR Master Mix: Includes heat-stable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffer.

- Total Reaction Volume: 50 µL.

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes.

- Amplification (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 55-60°C for 30 seconds (temperature is primer-specific).

- Extend: 72°C for 30 seconds.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

Post-Amplification: Verify PCR success and specificity by running 5 µL of the product on an agarose gel. The expected result is a single band of the correct size. Purify the PCR product using magnetic beads or a column-based kit to remove primers, enzymes, and salts.

Barcode Verification and Sequencing Analysis

Principle: To identify the relative abundance of each deletion strain in the pool by sequencing the amplified barcodes and mapping them to a reference database.

Procedure:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The purified PCR product is ready for sequencing on an NGS platform. The concentration of the library is normalized and loaded onto the sequencer.

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Demultiplexing: Assign raw sequence reads to the specific sample (control vs. treated).

- Barcode Extraction: Identify and extract the UPTAG and DNTAG sequences from each read.

- Strain Mapping: Map each barcode pair to a reference database (e.g., the Saccharomyces Genome Database) to identify the corresponding gene deletion.

- Abundance Quantification: Count the number of reads for each unique barcode in the control and treated samples.

- Fitness Calculation:

- Calculate a fitness score for each strain, typically as the log₂ ratio of its normalized abundance in the treated sample versus the control sample.

- Strains with significantly negative fitness scores are "hypersensitive" and indicate that the deleted gene is essential for survival in the presence of the chemical compound, potentially revealing the drug's mechanism of action or cellular target.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Chemical Genomics Screen Workflow

Barcode Verification Logic

In the field of yeast chemical genomics, the strategic use of haploid, diploid, and heterozygous diploid strain sets has revolutionized the systematic identification of drug targets and the functional annotation of genes. The foundational resource enabling these studies is the yeast deletion collection, a comprehensive set of over 21,000 mutant strains encompassing precise start-to-stop deletions of approximately 6,000 open reading frames [1]. This collection includes heterozygous diploids and homozygous diploids, plus haploids of both MATa and MATα mating types, providing an unparalleled toolkit for probing gene function [1] [9]. Chemical genomic screens exploit the distinct properties of these strain compositions to identify genetic interactions, pinpoint mechanisms of drug action, and discover novel therapeutic targets. The integration of these systematic deletion libraries with high-throughput screening technologies has established Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a premier model for functional genomics research directly relevant to human disease and drug development [1] [9].

Strain Compositions and Their Applications

Haploid Strains

Haploid yeast strains contain a single set of chromosomes and are primarily used in chemical genomic screens to identify genes essential for viability under specific conditions and to characterize drug-sensitive genetic interactions. In haploid deletion collections, each strain carries a single gene deletion, allowing researchers to directly link fitness defects in the presence of a chemical compound to the deleted gene's function [9]. This approach has been instrumental in identifying genes involved in DNA repair pathways, cell cycle checkpoints, and various stress response mechanisms [9]. However, a significant limitation of haploid strains is their inability to assess the function of essential genes, as deletion of such genes is lethal [9].

Homozygous Diploid Strains

Homozygous diploid strains carry two identical copies of each chromosome with the same gene deletion in both alleles. These strains enable the analysis of non-essential gene function in a diploid context and are particularly valuable for identifying synthetic lethal interactions and gene redundancies [1]. In chemical genomic screening, homozygous diploid profiling helps distinguish between haploinsufficient and recessive resistance mechanisms, providing deeper insights into compound mode of action [9]. The construction of a remarkable collection of 23 million yeast strains with two gene deletions per strain has enabled the systematic characterization of approximately 550,000 negative and 350,000 positive genetic interactions, dramatically expanding our understanding of genetic networks [9].

Heterozygous Diploid Strains

Heterozygous diploid strains contain one wild-type allele and one deleted (or mutant) allele for each targeted gene, creating a condition of reduced gene dosage ideal for haploinsufficiency profiling [1] [9]. This approach is exceptionally powerful for chemical genomic screens because it can identify direct protein targets of bioactive compounds—when the drug target is heterozygous, the reduced expression often confers heightened sensitivity to compounds that inhibit the same pathway [9]. Heterozygous diploid strains have demonstrated substantially greater tolerance to genome restructuring techniques compared to haploid strains, with survival rates generally exceeding 70% following induced genomic rearrangements versus less than 30% for haploids [10]. This robustness enables more complex genetic manipulations and screens that would be lethal in haploid contexts.

Table 1: Characteristics of Yeast Strain Types in Chemical Genomic Screens

| Strain Type | Chromosome Composition | Primary Screening Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haploid | Single copy of each chromosome | Fitness profiling, synthetic dosage lethality, drug sensitivity screens [9] | Direct genotype-phenotype linkage, simple interpretation | Cannot study essential genes, more sensitive to lethal mutations [10] |

| Homozygous Diploid | Two identical copies with same deletion | Analysis of non-essential genes in diploid context, synthetic lethality screens [1] [9] | Enables study of recessive mutations, more robust to single mutations | Masks heterozygous effects, cannot assess haploinsufficiency |

| Heterozygous Diploid | One wild-type and one deleted allele | Haploinsufficiency profiling, target identification [1] [9] | Identifies direct drug targets, more tolerant to genomic manipulations [10] | May miss recessive resistance mechanisms |

Experimental Protocols for Chemical Genomic Screening

Protocol: Haploinsufficiency Profiling with Heterozygous Diploid Collection

Purpose: To identify cellular targets of bioactive compounds by detecting heterozygous deletions that confer hypersensitivity.

Materials:

- Yeast heterozygous diploid deletion collection (commercially available from Euroscarf)

- Chemical compound for screening

- YPD medium: 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose [11]

- Synthetic complete (SC) medium: 6.7 g/L Yeast Nitrogen Base with ammonium sulfate, 2 g/L SC Amino Acid mixture, 20 g/L glucose [12]

- 384-well microplates

- High-throughput plate reader

- Automated pinning tools

Procedure:

- Grow the heterozygous diploid collection in 384-well format for 48 hours at 30°C in YPD medium [12].

- Using an automated pinning tool, transfer strains to fresh SC medium containing the test compound at multiple concentrations, including a no-compound control.

- Incubate plates in a high-throughput plate reader at 30°C with continuous shaking.

- Monitor optical density at 600 nm (OD600) every 15-60 minutes for 24-72 hours [12].

- Extract growth parameters (lag time, doubling time, yield) using analysis tools such as GATHODE (Growth Analysis Tool for High-throughput Optical Density Experiments) [12].

- Identify hypersensitive strains by comparing growth rates in compound versus control conditions, typically applying a threshold of 50% reduced fitness in the presence of compound.

- Validate putative targets through secondary assays and genetic approaches.

Protocol: High-Throughput Growth Phenotyping in 384-Well Format

Purpose: To quantitatively assess fitness of deletion strains in the presence of chemical perturbagens.

Materials:

- Yeast deletion collection (haploid, homozygous diploid, or heterozygous diploid)

- YPD or defined minimal media

- 384-well microplates

- Thermostated microplate reader with shaking capability

- Software tools (GATHODE for growth parameters, CATHODE for chronological lifespan) [12]

Procedure:

- Inoculate single colonies into 96-well or 384-well microplates in biological duplicates and grow overnight [12].

- Transfer 2 μL aliquots of overnight cultures into a final volume of 80 μL in 384-well microplates (initial OD ≈ 0.005-0.02) [12].

- Include wells with medium only for background correction.

- Incubate plates in a thermostated microplate reader at 30°C for 280 cycles of orbital shaking with OD600 measurements taken at regular intervals [12].

- Analyze growth curves using GATHODE software to determine key parameters: lag time, doubling time, and maximum biomass yield [12].

- Normalize data to control conditions and identify strains with statistically significant fitness defects or enhancements.

- For chronological lifespan assays, use the CATHODE tool to determine viability over time based on outgrowth kinetics [12].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Chemical Genomic Screens

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection | Comprehensive set of ~6,000 gene deletions in heterozygous diploid, homozygous diploid, and haploid backgrounds [1] | Euroscarf (http://web.) [1] |

| YPD Medium | Rich growth medium for routine yeast propagation (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 20 g/L glucose) [11] | Commercially available or prepared from components |

| Synthetic Complete Medium | Defined medium for selective growth and compound screening [12] | Formulation available in published protocols [12] |

| 384-Well Microplates | High-throughput format for growth assays and chemical screens [12] | Various commercial suppliers |

| GATHODE Software | Open-source tool for automated analysis of growth parameters from plate reader data [12] | https://platereader.github.io/ [12] |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

SCRaMbLE in Heterozygous Diploids for Phenotype Enhancement

The SCRaMbLE (Synthetic Chromosome Rearrangement and Modification by LoxP-mediated Evolution) system enables inducible genome restructuring in strains containing synthetic chromosomes with strategically positioned loxPsym sites [10]. When applied to heterozygous diploid strains, SCRaMbLE generates genomic rearrangements that would be lethal in haploid contexts, significantly expanding the accessible mutant space. In one application, SCRaMbLE of a heterozygous diploid strain composed of a sake-brewing Y12 strain mated with a synX-bearing strain yielded thermotolerant isolates capable of growth at 42°C [10]. Whole-genome sequencing revealed deletions in specific genomic regions, including the essential TIM17 gene, demonstrating that heterozygous diploids can tolerate and benefit from rearrangements involving essential genes [10].

Integration with CRISPR-Cas Technologies

Recent advances have integrated classical deletion collections with CRISPR-Cas technologies to enable more precise genetic manipulations and higher-throughput screens. CRISPR-Cas-mediated gene knockout studies allow rapid generation of additional mutant strains and complementation of existing deletions [9]. The CHAnGE (Homology Directed-Repair-Assisted Genome-Scale Engineering) method, for instance, was used to generate a large deletion collection screened for furfural tolerance [9]. Furthermore, CRISPR/dCas9 systems enable targeted transcriptional perturbations that can be combined with chemical treatments to dissect gene regulatory networks in drug response.

Visualizing Strain Construction and Screening Workflows

Strain Construction and Screening Workflow

The strategic application of haploid, diploid, and heterozygous diploid strain sets has established S. cerevisiae as a powerful platform for chemical genomic screening and drug target discovery. The integration of comprehensive deletion collections with high-throughput phenotyping methods enables systematic dissection of gene function and chemical-genetic interactions. Continuing developments in genome engineering technologies, including CRISPR-Cas systems and synthetic biology approaches like SCRaMbLE, promise to further enhance the resolution and utility of yeast-based chemical genomics for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Key Biological Insights and Early Discoveries

The Yeast Deletion Collection, also known as the yeast knockout (YKO) set, represents the first and only complete, systematically constructed deletion collection for any organism [1]. Conceived during the Saccharomyces cerevisiae sequencing project, this landmark resource comprises over 21,000 mutant strains with precise start-to-stop deletions of approximately 6,000 open reading frames, including heterozygous and homozygous diploids, and haploids of both MATa and MATα mating types [1]. Work began in 1998 and was completed in 2002, providing the research community with an unparalleled tool for functional genomics [1]. The collection has since been used in over 1,000 genome-wide screens, enabling systematic investigation of gene function, genetic interactions, and gene-environment transactions [1]. Its development inspired numerous genome-wide technologies across diverse organisms and led to notable spinoff technologies such as Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) and HIP/HOP chemogenomics [1].

Key Biological Insights from Yeast Deletion Library Screens

Unveiling Gene Function and Essentiality

Initial analysis of the yeast deletion collection provided fundamental insights into the yeast genome. Early studies revealed that approximately 20% of yeast genes are essential for viability in standard laboratory conditions [1]. However, essentiality exists on a spectrum rather than as a binary distinction, with 39% of genes on chromosome V showing some degree of growth defect when disrupted [1]. The project also demonstrated that duplicated genes are frequently not redundant, as deletion of one copy often produces distinct fitness phenotypes compared to its paralog [1].

Mapping Mechanisms of Antifungal Action

Screening the nonessential gene deletion library has proven particularly valuable for elucidating mechanisms of antifungal compounds. A 2019 study screened the yeast deletion collection against four plant defensins (NaD1, DmAMP1, NbD6, and SBI6) to identify their novel mechanisms of action [13]. The screen identified a previously unknown role for the vacuole in the mechanisms of NbD6 and SBI6, which was subsequently confirmed through confocal microscopy in both S. cerevisiae and the cereal pathogen Fusarium graminearum [13]. This demonstrated how unbiased screening of the deletion library can reveal unexpected cellular targets and pathways.

Table 1: Key Insights from Plant Defensin Screening Using the Yeast Deletion Collection

| Defensin | IC₇₀ (μM) | Key Finding | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaD1 | 4.0 | Distinct fitness profile suggesting unique mechanism | Antifungal assays with resistant mutant strains [13] |

| DmAMP1 | 4.0 | Distinct fitness profile different from other defensins | Antifungal assays with resistant mutant strains [13] |

| NbD6 | 3.0 | Novel involvement of vacuolar function | Confocal microscopy in S. cerevisiae and F. graminearum [13] |

| SBI6 | 5.0 | Novel involvement of vacuolar function; similar mechanism to NbD6 | Confocal microscopy in S. cerevisiae and F. graminearum [13] |

Discovering Genetic Markers of Robustness

Recent research has utilized the deletion collection to identify genetic determinants of microbial robustness—the ability to maintain stable performance under perturbation. A 2024 study re-analyzed fitness data from over 4,000 mutants across 14 conditions, identifying genes associated with increased robustness (e.g., MET28, involved in sulfur metabolism) and decreased robustness (e.g., TIR3 and WWM1, involved in stress response and apoptosis) [14]. This approach demonstrated how phenomics datasets can reveal relationships between phenotypic stability and underlying genetic architecture, with potential applications in engineering industrial strains with more consistent performance in bioreactor environments [14].

Table 2: Genes Identified as Markers of Robustness in S. cerevisiae

| Gene | Function | Effect on Robustness | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| MET28 | Sulfur metabolism | Increased | Biosynthetic process [14] |

| QDR1 | Multidrug transporter | Increased | Drug transport [14] |

| MRP31 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein | Increased | Mitochondrial translation [14] |

| TIR3 | Stress response | Decreased | Apoptosis/Cell death [14] |

| WWM1 | Stress response | Decreased | Apoptosis/Cell death [14] |

| BCH1 | Bud emergence | Decreased | Cell polarity [14] |

| HLJ1 | Protein folding | Decreased | Chaperone activity [14] |

Revealing Regulatory Networks

Large-scale genetic perturbation studies have provided systems-level insights into regulatory networks. One comprehensive resource reported expression signatures for 1,484 yeast gene knockouts, revealing pathway connectivity, branching points, and network responsiveness to genetic perturbation [15]. The analysis demonstrated an unexpected abundance of gene-specific repressors, suggesting that yeast chromatin is not as generally restrictive to transcription as previously assumed [15]. The study also found that four types of feed-forward loops were overrepresented in the genetic perturbation network, providing insights into the design principles of biological regulatory systems [15].

Experimental Protocols for Chemical-Genetic Screening

High-Throughput Chemical-Genetic Screening Protocol

The following protocol describes a highly parallelized approach for functional annotation of chemical libraries using a diagnostic subset of the yeast deletion collection [4].

Strain Collection and Growth Conditions

- Drug-sensitized background: Use the pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ (3Δ) strain background to enhance detection of bioactive compounds. This sensitized background increases the hit rate approximately 5-fold compared to wild-type strains [4].

- Diagnostic mutant pool: Use a pool of 310 deletion mutant strains representing major biological processes. This subset captures the functional diversity of the full collection while enabling higher multiplexing [4].

- Culture conditions: Grow pooled mutants in appropriate selective medium at 30°C with shaking.

Compound Treatment and Fitness Measurement

- Compound preparation: Prepare compounds in DMSO or appropriate solvent. Include solvent-only controls.

- Inoculation and incubation: Inoculate pooled mutants at optimized density and incubate for 48 hours with compound treatment. The 48-hour timepoint provides optimal signal-to-noise ratio for detecting chemical-genetic interactions [4].

- Fitness quantification: Isolate genomic DNA from pre- and post-treatment cultures. Amplify unique molecular barcodes with 18-20 PCR cycles to maintain linear amplification [4]. Sequence barcodes using high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina platform).

Data Analysis and Target Prediction

- Fitness score calculation: Calculate fitness scores as log₂ ratios of barcode counts in treated versus untreated samples.

- Chemical-genetic profiles: Compare chemical-genetic interaction profiles to a compendium of genome-wide genetic interaction profiles to predict compound functionality [4].

- Functional annotation: Annotate compounds to specific biological processes based on profile similarity to known genetic perturbations.

Mechanism of Action Screening for Antifungal Compounds

This protocol details the use of the nonessential deletion collection to identify novel mechanisms of antifungal action [13].

Library Preparation and Treatment

- Strain pool: Use the commercially available nonessential gene deletion set (~4,800 strains) in the BY4741 background.

- Growth conditions: Grow pooled mutants in YPD medium at 30°C with shaking.

- Compound treatment: Treat with compound at IC₇₀ concentration (e.g., 70% growth inhibition relative to untreated controls). For defensins NaD1, DmAMP1, NbD6, and SBI6, use 4.0, 4.0, 3.0, and 5.0 μM concentrations, respectively [13].

- Controls: Include untreated controls and wild-type strain (BY4741) to measure growth inhibition.

Barcode Amplification and Sequencing

- DNA extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from treated and untreated pools.

- Amplicon generation: Amplify upstream and downstream barcodes using primers targeting conserved flanking regions.

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing (e.g., MiSeq) with mean read depth of ~1.7 million reads per sample [13].

Data Analysis and Hit Validation

- Fitness calculation: Calculate fitness scores as log₂(treated/untreated) for each strain. Positive scores indicate resistance; negative scores indicate sensitivity [13].

- Functional enrichment: Use tools such as FunSpec to identify biological processes enriched among resistant or sensitive strains [13].

- Independent validation: Confirm hits using individual antifungal assays with selected resistant mutants.

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Biological Relationships

Workflow for Chemical-Genetic Screening

Diagram 1: Chemical-genetic screening workflow for functional annotation of compound libraries.

Mechanism of Action Screening for Antifungal Compounds

Diagram 2: Mechanism of action screening for antifungal compounds using the yeast deletion library.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Yeast Deletion Library Screens

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collections | Complete sets of knockout strains for genome-wide screening | Heterozygous diploid, homozygous diploid, and haploid (MATa and MATα) collections [1] |

| Drug-Sensitized Strains | Enhanced sensitivity for detecting compound bioactivity | pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ (3Δ) background [4] |

| Molecular Barcodes | Unique DNA sequences for tracking strain abundance in pools | Upstream and downstream 20-nucleotide barcodes for each deletion strain [1] [13] |

| Barcode Amplification Primers | Conserved primers for amplifying barcode sequences from pooled samples | Primers targeting common sequences flanking unique barcodes [13] |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Platform for quantifying barcode abundance | Illumina MiSeq or similar platform [13] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data analysis for fitness scoring and functional enrichment | Bowtie2 for alignment, FunSpec for enrichment analysis [13] [4] |

| Genetic Interaction Network | Reference database for interpreting chemical-genetic profiles | Global yeast genetic interaction network for functional annotation [4] |

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion libraries represent a cornerstone of modern functional genomics, enabling systematic analysis of gene function at an unprecedented scale. Conceived during the yeast genome sequencing project, this collection comprises over 21,000 mutant strains with precise start-to-stop deletions of approximately 6,000 open reading frames, making it the first and only complete, systematically constructed deletion collection for any organism [1]. These resources have transformed yeast into a powerful model system for chemical genomic screens, allowing researchers to identify gene functions, drug targets, and genetic interactions through high-throughput phenotypic analysis.

The development and distribution of these libraries through centralized repositories like EUROSCARF (European Saccharomyces cerevisiae Archive for Functional Analysis) has been instrumental in their adoption by the global research community. EUROSCARF was established specifically for the deposit and delivery of biological materials generated in genome analysis networks, including critical projects such as the BMBF project, EUROFAN I, and the worldwide yeast gene deletion project (EUROFAN II) [16]. This infrastructure addressed a critical need in the scientific community, as individual laboratories previously struggled to manage the overwhelming demand for reagents, exemplified by one group of less than 40 scientists receiving hundreds of reagent requests before outsourcing distribution to EUROSCARF [17].

The Yeast Deletion Collections: Technical Specifications and Historical Development

Project Lineages and Strain Backgrounds

The yeast deletion collections available through EUROSCARF originated from several key international collaborations, each contributing specific genetic resources with distinct characteristics [16]:

Table 1: Major Projects Contributing to Yeast Deletion Collections

| Project Name | Time Period | Key Contributions | Genetic Backgrounds | Strain Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| German Yeast Functional Analysis (BMBF) | 1994-1997 | 325 gene deletions; collaboration of 15 laboratories | CEN.PK2 | Accession numbers with preceding "B" followed by 4-digit code and terminal letter |

| EUROFAN I | 1996 onwards | 800 ORF deletions; involved 115 research groups | FY1679 (isogenic to S288C), CEN.PK2, W303 | 5-digit numerical code followed by terminal mating type letter |

| Worldwide Gene Deletion Project (EUROFAN II) | 1998-2002 | ~6,000 ORF deletions; global consortium effort | BY series (isogenic to S288C) | Preceding "Y" followed by record number from genome deletion project |

The complete deletion collection includes heterozygous and homozygous diploids, and haploids of both MATa and MATα mating types, providing researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for genetic analysis [1]. For essential genes, only heterozygous diploids are available, as homozygous deletions would be lethal [16]. The strategic decision to create deletions in multiple genetic backgrounds (including S288C, CEN.PK2, and W303) demonstrates foresight in ensuring the cassettes would have general utility across different laboratory strains [16].

Molecular Design and Verification

The deletion strains were constructed using a sophisticated PCR-based gene replacement strategy that replaced each open reading frame with a KanMX cassette, which confers resistance to the antibiotic G418 [1]. This cassette also contains unique "barcode" sequences that enable identification and tracking of individual strains in pooled experiments—a feature that has proven invaluable for high-throughput fitness profiling [1].

Each deletion mutant underwent rigorous verification through a quality control process involving multiple PCR tests to confirm proper replacement of the target gene with the KanMX cassette at the correct genomic location [1]. The project achieved remarkable success, with 96.5% of annotated ORFs of 100 codons or larger successfully disrupted [1]. Interestingly, of the approximately 5% of yeast genes that could not be deleted, 62% remain without known biological function, suggesting potential undiscovered essential genes [1].

Accessing the Collections: Distribution Pathways and Practical Considerations

EUROSCARF Distribution Infrastructure

EUROSCARF serves as the primary distribution hub for these valuable biological resources, providing reliable access to researchers worldwide. The repository has implemented a structured pricing model to ensure sustainable operation while maintaining accessibility [18]:

Table 2: EUROSCARF Handling Fees (Effective October 2022)

| Number of Items Ordered | Price per Item (Euros) | Total Cost Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 item | €70 | €70 |

| 2-4 items | €58 each | €116-€232 |

| 5-7 items | €50 each | €250-€350 |

| 8-10 items | €43 each | €344-€430 |

| 11+ items | €20 each additional | €430 + €20 per additional strain |

This tiered pricing structure makes the collection increasingly accessible for large-scale screens while ensuring the repository's operational sustainability. Researchers can order strains through the EUROSCARF website, which has recently undergone updates to improve user experience and functionality [18].

Strain Selection Considerations

When designing chemical genomic screens using these collections, researchers must consider several critical factors in strain selection:

- Genetic Background: Different strain backgrounds (S288C-derived, CEN.PK2, W303) may exhibit varying phenotypic responses to chemical compounds due to differences in their genetic makeup [16].

- Mating Type: The availability of both MATa and MATα haploid strains enables studies of mating-type-specific effects and genetic crosses [1].

- Auxotrophic Markers: The presence of auxotrophic markers (e.g., in the BY series) can influence metabolic states and potentially affect chemical sensitivity [1]. Some studies have shown that these markers have nontrivial effects on experimental outcomes, particularly in metabolic studies [1].

- Verification Status: Researchers should consult current EUROSCARF documentation for the latest verification data on specific strains of interest.

Experimental Protocols: Utilization in Chemical Genomic Screens

Chemical Genomic Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for chemical genomic screens using yeast deletion collections:

This workflow leverages the unique molecular barcodes embedded in each deletion strain, enabling precise tracking of strain abundance in pooled competitive growth assays [1]. The relative fitness of each strain under chemical treatment conditions can be quantified by monitoring barcode abundance changes through microarray or sequencing-based detection methods.

Protocol: Pooled Competitive Growth Assay

Materials Required:

- Yeast deletion pool (homozygous diploid or haploid as appropriate)

- Chemical compound of interest dissolved in suitable solvent

- Appropriate growth medium (YPD or synthetic complete)

- G418 antibiotic for selection maintenance

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents for barcode amplification

- Sequencing library preparation reagents

Procedure:

Strain Pool Preparation: Combine equal numbers of cells from each deletion strain to create a representative pool. Verify pool complexity by checking representation of all barcodes [1] [19].

Chemical Treatment:

- Inoculate the pooled strains into medium containing the test compound at desired concentration(s). Include solvent-only controls.

- Culture with appropriate aeration for approximately 10-20 generations to allow fitness differences to manifest [1].

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect samples at multiple time points (T₀, T₁, T₂, etc.) to monitor dynamic changes.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and extract genomic DNA using standard protocols [19].

Barcode Amplification and Sequencing:

- Amplify the unique barcode sequences from genomic DNA samples using fluorescently-labeled primers.

- Alternatively, prepare sequencing libraries for high-throughput analysis [1].

- Quantify barcode abundance through microarray hybridization or next-generation sequencing.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate fitness scores for each strain by comparing barcode abundance changes between treatment and control conditions.

- Identify sensitive strains (negative fitness scores) and resistant strains (positive fitness scores).

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes affected by the chemical compound.

This protocol enables the systematic identification of gene deletions that confer sensitivity or resistance to chemical compounds, providing insights into mechanism of action and potential cellular targets.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Deletion Library Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Deletion Library Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Collections | EUROSCARF deletion strains (haploid a/α, heterozygous/homozygous diploid) | Chemical genomic screens, functional analysis | Select appropriate genetic background and mating type for experimental goals [16] [1] |

| Growth Media Components | YPD, Synthetic Complete (SC) media, G418 antibiotic | Strain maintenance, selection pressure | Auxotrophic markers in BY strains require supplemented media [1] [19] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | DNA extraction kits, PCR reagents, barcode amplification primers | Strain verification, barcode quantification | Optimize protocols for high-throughput processing [19] |

| Analysis Tools | Microarray platforms, sequencing reagents | Barcode abundance quantification | Barcode sequences enable pooled fitness analysis [1] |

| Plasmid Collections | Complementation vectors, CRISPR/Cas9 constructs | Follow-up validation, mechanistic studies | Available through Addgene and EUROSCARF [20] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The yeast deletion collections continue to enable innovative research approaches beyond traditional chemical genomics. Recent advances include:

Integration with Omics Technologies

Modern proteomic approaches have leveraged the deletion collections for deep functional characterization. As demonstrated in recent studies, isobaric tag-based sample multiplexing (e.g., TMTpro16) enables high-throughput profiling of deletion strain proteomes, revealing covariance networks and functional relationships [19]. This approach has been used to quantify nearly 5,000 yeast proteins across 75 deletion strains, generating rich datasets for network-based analyses [19].

CRISPR-Enabled Enhancements

While the original deletion collections remain invaluable, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technologies now complement these resources by enabling more sophisticated genetic manipulations [20] [6]. CRISPR systems facilitate the introduction of multiple genetic modifications simultaneously, allowing for complex genotype-phenotype studies in both conventional and non-conventional yeast species [20] [6]. These tools are particularly valuable for hypothesis testing following initial hits from deletion library screens.

The yeast deletion collections, distributed globally through EUROSCARF, continue to serve as fundamental resources for understanding gene function and chemical-genetic interactions. Their systematic construction and accessibility have democratized functional genomics, enabling researchers worldwide to pursue sophisticated questions about biological systems and chemical mode of action. As new technologies emerge, these carefully curated collections remain relevant through integration with advanced analytical methods and editing tools, ensuring their continued contribution to scientific discovery.

Executing High-Throughput Chemical Genomic Screens: A Step-by-Step Workflow

Chemical-genetic screening in S. cerevisiae represents a powerful functional genomics approach for annotating compound mode-of-action and identifying novel gene functions. These screens systematically quantify how genetic perturbations, such as gene deletions, alter a cell's sensitivity to chemical compounds [4]. The design of such screens—spanning from the selection of chemical conditions to the quantitative definition of phenotypes—is critical for generating meaningful, high-quality data. When performed in pooled formats with barcoded yeast deletion libraries, these screens require careful optimization of both biological and computational methodologies to accurately detect chemical-genetic interactions [4] [21]. This protocol details the establishment of a high-throughput screening pipeline, from library preparation and condition selection to data analysis and phenotype definition, within the context of a drug-hypersensitized yeast background that significantly increases the detection of bioactive compounds [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials and reagents for executing a chemical-genetic screen in S. cerevisiae.

TABLE 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function and Description |

|---|---|

Drug-Sensitized Yeast Strain (e.g., pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ) |

A genetic background that disrupts pleiotropic drug response, increasing sensitivity to compounds and enhancing hit rates approximately 5-fold [4]. |

| Diagnostic Mutant Pool (e.g., 310-strain subset) | A optimized, barcoded collection of non-essential gene deletion mutants representing all major biological processes, enabling efficient profiling without screening the entire deletion collection [4]. |

| Pooled Chemical Libraries | Collections of compounds for screening; reported hit rates can reach ~35% in the drug-sensitized background [4]. |

| dCas9-Mxi1 Repressor System | A CRISPRi plasmid system for inducible, targeted gene repression, useful for validating hits or screening essential genes [22]. |

| BEAN-counter Software | A computational pipeline for processing multiplexed barcode sequencing data into quantitative chemical-genetic interaction scores (z-scores) [21]. |

| Anhydrotetracycline (ATc) | An inducer for the Tet-ON system regulating gRNA expression in the referenced CRISPRi plasmid [22]. |

Protocol: A High-Throughput Chemical-Genetic Screening Pipeline

This protocol describes the steps for performing a pooled chemical-genetic screen, from library cultivation to data analysis.

Stage 1: Preparation of the Pooled Mutant Library

- Culture Inoculation: Thaw the diagnostic mutant pool (see Table 1) and inoculate into an appropriate selective liquid medium. Grow the culture to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.5-0.8) under standard conditions (e.g., 30°C with shaking).

- Cell Pooling and Normalization: Ensure uniform representation of all barcoded mutants in the culture. The use of a pre-selected pool with near-equivalent fitness is critical for minimizing growth-based biases from the outset [4].

Stage 2: Compound Treatment and Competitive Growth

- Compound Dilution and Plating: Prepare working concentrations of compounds from screening libraries in DMSO or appropriate solvent. Dispense into 96- or 384-well microtiter plates. Include solvent-only negative controls.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Dilute the prepared cell pool and aliquot into the compound plates. The initial inoculum size is flexible, but a standardized density must be used across the screen [4].

- Incubation: A key parameter is incubation time. Grow the plates for 48 hours at 30°C. This duration has been demonstrated to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting chemical-genetic interactions, allowing for clear depletion or enrichment of sensitive strains [4].

Stage 3: Barcode Sequencing and Data Generation

- Genomic DNA Extraction: After incubation, harvest cells from each well and extract genomic DNA.

- Multiplexed PCR Amplification: Amplify the unique molecular barcodes from each sample using primers with indexing tags to allow for multiplexing. The number of PCR cycles should be optimized to avoid over-amplification but is generally a robust parameter [4].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Pool the PCR products and perform NGS to quantify barcode abundance.

Stage 4: Data Analysis and Phenotype Definition

- Raw Data Processing with BEAN-counter: Use the BEAN-counter software pipeline to process the raw sequencing data.

- Inputs: (a) Sequencing reads, (b) Barcode-to-strain mapping file, (c) Index-to-chemical condition mapping file [21].

- Processing: The pipeline performs quality control, normalizes data to correct for technical artifacts and systematic biases, and calculates a chemical-genetic interaction score for each strain in each condition [21].

- Phenotype Definition via Z-scores: The primary phenotype is defined as a chemical-genetic interaction z-score. BEAN-counter computes these z-scores based on the standardized change in strain abundance relative to the population, providing a quantitative measure of a mutant's sensitivity or resistance to a compound [21].

- Functional Annotation: Compare the resulting chemical-genetic interaction profile (the vector of z-scores for all mutants in the pool for a given compound) to a compendium of genome-wide genetic interaction profiles. Compounds with similar profiles to known gene deletions are predicted to target the same biological pathway or process [4].

Results and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Data from Screening Optimization

The following table summarizes critical parameters and their impact on the outcome of the screen, based on experimental optimizations.

TABLE 2: Impact of Key Experimental Parameters on Screen Performance

| Parameter | Tested Range | Optimal Value | Impact on Screen Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation Time | 0 - 48 hours | 48 hours | Most pronounced effect on signal-to-noise. 48-hour incubation enables clear depletion of sensitive mutants (e.g., microtubule mutants on benomyl) [4]. |

| Genetic Background | Wild-type vs. pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ |

pdr1Δ pdr3Δ snq2Δ |

~5-fold increase in bioactive compound detection. Enables identification of specific chemical-genetic interactions (e.g., with TUB3 or BCK1) that are not detectable in wild-type [4]. |

| Strain Pool Complexity | Full (~5,000 mutants) vs. Diagnostic (~310 mutants) | Diagnostic Subset | Reduces noise and increases multiplexing capability while maintaining predictive power for all major biological processes [4]. |

| Compound Concentration | Variable | Library/compound dependent | Must be titrated; the use of a drug-sensitized strain allows for lower, more specific concentrations (e.g., 25 nM micafungin) to be effective [4]. |

Expected Results and Validation

- Identification of Chemical-Genetic Interactions: Successful screens will yield a set of strains with significant z-scores (e.g., |z-score| > 3) for specific compounds. For example, repression of

ERG11orERG25should confer hypersensitivity to fluconazole, serving as a positive control [22] [4]. - Mode-of-Action Prediction: A compound's chemical-genetic interaction profile can be correlated with a database of genetic interaction profiles. A high correlation with the profile of a specific gene (e.g., a partial loss-of-function mutation in

ERG11) strongly suggests the compound acts on that pathway (e.g., the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway) [4]. - Discovery of Novel Interactions: The unbiased nature of the screen allows for the discovery of unexpected chemical-genetic interactions, such as the suppression of fluconazole toxicity upon repression of

ERG25, revealing new cellular resistance mechanisms [22].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete screening pipeline, from library construction to functional annotation.

Applications in Drug Discovery

The methodology outlined herein enables systematic functional annotation of chemical libraries. The primary applications include:

- Target Identification and Validation: The core application is predicting the biological pathway or specific protein target of uncharacterized bioactive compounds by matching their chemical-genetic profiles to known genetic defect profiles [4].

- Identification of Compound Synergy or Toxicity: Chemical-genetic profiles can reveal if a compound affects multiple pathways, suggesting potential mechanisms of off-target toxicity or polypharmacology [4].

- Unbiased Discovery of Resistance Mechanisms: Screening can identify gene deletions that confer resistance to a compound, revealing new insights into a drug's mechanism and potential compensatory pathways in the cell [22].

- Chemical Probe Development: This pipeline is ideal for characterizing and validating chemical probes that selectively modulate specific cellular processes, a key need in functional genomics and early drug discovery [4].

Within the context of chemical genomic screens using S. cerevisiae deletion libraries, robust library handling techniques are not merely procedural necessities but fundamental to data integrity and experimental reproducibility. The ability to accurately replicate, stamp, and store source plates ensures the consistent performance required for high-throughput screening, where subtle variations in protocol execution can significantly impact the assessment of gene-chemical interactions and compound toxicity profiles. This application note details standardized methodologies for handling yeast libraries, with a focus on techniques validated through recent functional genomics research.

Core Techniques and Protocols

Replica Plating for Genotype Validation

Replica plating serves as a critical technique for validating strain genotypes, such as confirming the successful generation of respiration-deficient strains, without the need for individual colony purification.

Detailed Protocol: Replica Plating for Mitochondrial DNA Knockout Validation

- Objective: To validate the loss of mitochondrial DNA (Rho- mutation) in S. cerevisiae strains, ensuring the yeast exhibits a fermentative-only metabolic phenotype [23].

- Principle: This stamping technique transfers an array of colonies from a master plate to secondary plates with different carbon sources. Growth on fermentable carbon sources (e.g., maltose) but not on non-fermentable sources (e.g., glycerol) confirms the respiratory deficiency [23].

Workflow:

- Preparation: Pour two agar plates: one with YPD (or maltose) medium and one with YPGlycerol medium. Ensure the master plate containing the yeast colonies to be tested is freshly grown (24-48 hours old).

- Transfer: Use a sterile velveteen pad or a specialized replicator tool. Press the tool gently onto the surface of the master plate to pick up a tiny amount of each colony.

- Stamping: Press the tool gently and evenly onto the surfaces of the two new plates (YPD/Maltose and YPGlycerol) in the same orientation. This transfers the colony pattern.

- Incubation: Incubate the secondary plates at 30°C for 2-3 days.

- Analysis: Compare growth between plates. Colonies that grow on YPD/Maltose but not on YPGlycerol have successfully lost their mitochondrial DNA (Rho-) and are respiration-deficient [23].

Visual Workflow: Replica Plating

Library Replication and Storage

Maintaining the viability and genetic stability of source libraries is paramount for long-term chemical genomics projects.

Protocol: High-Density Plate Replication for Screening

- Objective: To create working copies from a master source plate for use in chemical genomic screens.

- Procedure:

- Source Plate Thawing: Rapidly thaw frozen source plates (e.g., -80°C glycerol stocks) at room temperature or in a water bath just until the ice melts.

- Inoculation: Using a 96- or 384-pin replicator, gently dip the sterilized pins into the source plate wells.

- Transfer: Stamp the pins onto fresh agar plates containing the appropriate selective medium. Ensure even contact to transfer a consistent inoculum.

- Growth: Incubate the new plates at 30°C until colonies are of sufficient size (typically 1-2 mm in diameter, often 48-72 hours).

- Documentation: Clearly label all replicated plates with strain library identifiers, date, and passage number.

Protocol: Long-Term Storage of Source Plates

- Objective: To preserve yeast library strains for future use without genetic drift or loss of viability.

- Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Grow strains in the appropriate liquid medium to saturation or pick fresh colonies from a plate.

- Glycerol Stock Preparation: Mix the cell culture with sterile glycerol to a final concentration of 15-25% (v/v). For example, add 700 µL of culture to 300 µL of sterile 50% glycerol in a cryovial.

- Homogenization: Vortex the mixture thoroughly to ensure glycerol is evenly distributed.

- Freezing: Store the cryovials at -80°C. A slow freezing rate is not necessary for S. cerevisiae.

- Quality Control: After 24-48 hours, thaw a representative vial from each batch to verify viability and absence of contamination.

Quantitative Data for Protocol Planning

Table 1: Key Parameters for Yeast Library Handling Protocols

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Application Notes | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica Plating Incubation | 2-3 days at 30°C | Time for clear phenotypic distinction on selective media (e.g., glycerol). | [23] |

| SWAP-Tag Library Efficiency | 89.5% - 94.5% | Efficiency of strain survival and correct tag integration in modern library construction. | [24] |

| Final Glycerol Concentration | 15% - 25% (v/v) | Standard range for cryopreservation of S. cerevisiae at -80°C. | Common Protocol |

| Liquid Culture for Storage | Saturation (OD~600~ ~2.0-3.0) | Ensures high cell density for robust recovery after thawing. | Common Protocol |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Yeast Library Handling

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile Velveteen Pads / Replicator | Transfer of microbial colonies from a master plate to secondary plates for phenotypic screening. | Enables high-throughput genotype-phenotype validation, e.g., Rho- strain confirmation [23]. |

| SWAP-Tag Acceptor Library | A foundational resource for creating new proteome-wide tagged libraries with high efficiency. | Used to generate HA-tagged libraries with ~90% success rate, diversifying functional genomics tools [24]. |

| Nourseothricin (Nat) Resistance Cassette | A common selectable marker for maintaining plasmid or genomic integration in engineered yeast strains. | Used in the construction of the N-terminally HA-tagged yeast library [24]. |

| YPD & YPGlycerol Media | Complete media for general growth (YPD) and for identifying respiratory-deficient mutants (YPGlycerol). | Glycerol is a non-fermentable carbon source; used in replica plating to validate Rho- strains [23]. |

| Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) | Induction of Rho- mutations by intercalating into and promoting the loss of mitochondrial DNA. | Critical for generating fermentative-specific yeast strains for co-culture systems [23]. |

Mastering the fundamental techniques of replicating, stamping, and storing yeast source plates is a critical component of robust chemical genomic research. The protocols and data outlined herein provide a standardized framework that supports the reliability and reproducibility of high-throughput screens, directly contributing to the accurate mapping of genotype to chemical phenotype in S. cerevisiae.

Phenotypic profiling of Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion libraries provides a powerful framework for understanding gene function by measuring observable traits—fitness, biofilm formation, and cellular morphology. This approach is fundamental to chemical genomic screens, enabling researchers to identify gene-drug interactions and characterize mechanisms of action for novel compounds. The systematic interrogation of homozygous diploid yeast deletion collections allows for high-throughput screening under diverse conditions, from standard growth to chemical stress, linking genetic perturbations to complex phenotypic outcomes [6].

Key Phenotypic Assays and Their Quantitative Outputs

Phenotypic profiling in yeast involves quantifying specific cellular traits to determine gene essentiality, compound sensitivity, and biological function. The following assays are central to chemical genomic screens.

Fitness and Growth Profiling

Fitness is the most fundamental phenotype, typically measured as growth rate or final biomass yield in pooled competition experiments. In chemical genomic screens, fitness defects (sensitivity) or advantages (resistance) in the presence of a compound reveal potential drug targets and cellular defense mechanisms [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Fitness and Growth Profiling

| Metric | Description | Typical Assay Format | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Rate of population doubling over time | Liquid culture, continuous monitoring | Doubling time (minutes/hours) |

| Relative Fitness | Growth of a mutant strain relative to a reference | Pooled competition, spot assays | Fitness score (normalized value) |

| Colony Size | Area of colony formation on solid media | Solid agar plates, colony imaging | Pixel count or area (mm²) |

| Growth Curve Parameters | Features derived from entire growth curve | High-throughput spectrophotometry | Parameters: AUC, max OD, lag time |

Biofilm and Colony Architecture Profiling

Biofilm formation represents a complex phenotype involving adhesion, extracellular matrix production, and structured community growth. Variation in colony biofilm architecture serves as a readily assayed indicator of underlying genetic variation affecting these processes [25].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Biofilm Profiling

| Metric | Description | Typical Assay Format | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to Plastic | Capacity for surface attachment | Microtiter plate assay, crystal violet staining | Absorbance (OD570-600 nm) |

| Colony Complexity | Architectural intricacy of colony biofilms | Solid agar plates, macroscopic imaging | Morphotype classification, fractal dimension |

| Extracellular Matrix Production | Secretion of polysaccharides and proteins | Staining assays (e.g., Calcofluor white) | Fluorescence intensity |

| Structured Community Biomass | Total biomass in structured biofilms | Confocal microscopy, biomass staining | Biomass volume (μm³/area) |

Cellular Morphology Profiling

Image-based profiling captures subtle changes in cellular and subcellular morphology using high-content screening and automated image analysis. This approach can reveal specific mechanisms of action for chemical compounds [26].

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for Morphology Profiling

| Metric | Description | Typical Assay Format | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Shape Features | Size, elongation, eccentricity | Fluorescence microscopy, Cell Painting | Numerical descriptors (e.g., aspect ratio) |

| Subcellular Organization | Spatial arrangement of organelles | Organelle-specific staining, confocal microscopy | Texture, correlation features |

| Cellular Population Context | Spatial relationships between cells | High-content imaging, segmentation | Nearest-neighbor distances, clustering indices |

Experimental Protocols for Phenotypic Profiling

Protocol 1: Chemical Genomic Fitness Screen

This protocol describes a pooled competition assay to identify yeast deletion strains with altered fitness in the presence of a test compound.

Materials:

- Yeast deletion library (arrayed or pooled format)

- Test compound dissolved in appropriate solvent

- YPD or synthetic complete (SC) media

- 96-well or 384-well microplates

- Automated liquid handling system

- Microplate spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Library Preparation: Inoculate yeast deletion library in liquid media and grow to mid-log phase.

- Compound Exposure: Dispense cultures into microplates containing serial dilutions of test compound or solvent control.

- Growth Measurement: Incubate with shaking at 30°C while monitoring optical density (OD600) every 15-60 minutes for 24-48 hours.

- Data Collection: Record growth curves for each strain in each condition.

- Fitness Calculation: Calculate relative fitness for each strain as the area under the curve (AUC) in compound condition normalized to the control condition.

Data Analysis:

- Compute Z-scores for fitness values to identify significant sensitivity or resistance.

- Apply statistical cutoffs (e.g., Z-score > 2 or < -2) to identify hits.

- Cluster sensitivity profiles across multiple compounds to identify functional relationships.

Protocol 2: Colony Biofilm Architecture Assay

This protocol quantifies variation in complex colony biofilm formation in yeast deletion strains, based on methods used to identify genetic architecture of biofilm formation [25].

Materials:

- Yeast deletion strains to be tested

- YPD or YEPLD media (for glucose limitation)

- Low glucose agar plates (0.1%-1% glucose)

- Flat-bottom petri dishes

- Stereomicroscope or high-resolution scanner

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ)

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Grow test strains to saturation in liquid YPD.

- Spot Inoculation: Spot equal cell numbers (typically 5-10 μL) onto low glucose agar plates.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 25-30°C for 5-10 days without disturbance.

- Imaging: Capture high-resolution images of colonies under standardized lighting conditions.

- Phenotypic Scoring: Classify colony architecture using standardized morphotype categories (simple, complex, structured).

Data Analysis:

- Quantify architectural features: surface wrinkling, invasion, aerial structures.

- Score adherence to plastic by growing strains in microtiter plates and measuring OD after washing [25].

- Correlate biofilm phenotypes with genetic profiles to identify functional gene networks.

Protocol 3: High-Content Morphological Profiling (Cell Painting)

This protocol adapts the Cell Painting assay for yeast deletion libraries to capture comprehensive morphological features [26].

Materials:

- Yeast deletion strains in 384-well imaging plates

- Fixative (formaldehyde or similar)

- Cell Painting dye set:

- Mitotracker (mitochondria)

- Phalloidin (actin)

- Concanavalin A (cell wall)

- Hoechst or DAPI (nucleus)

- Wheat Germ Agglutinin (glycoproteins)

- High-content microscope with environmental control

- Image analysis software (e.g., CellProfiler)

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Grow deletion strains to mid-log phase in appropriate media.

- Compound Treatment: Add test compounds or controls to each well.

- Fixation and Staining: After appropriate incubation, fix cells and apply Cell Painting dye cocktail.

- Image Acquisition: Automatically acquire multi-channel images for each well.

- Feature Extraction: Use image analysis software to extract morphological features for each cell.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize features across plates and batches.

- Use machine learning approaches to classify morphological profiles.

- Compare profiles to reference databases to predict gene function or compound mechanism.

Signaling Pathways in Yeast Phenotypic Variation

The cAMP-PKA Pathway in Biofilm Regulation

Genetic analysis of biofilm formation in clinical S. cerevisiae isolates has identified the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A (cAMP-PKA) pathway as a central regulator of colony architecture [25]. The following diagram illustrates this pathway and key regulatory relationships:

Pathway Title: cAMP-PKA Signaling Regulates Biofilm Formation

Pathway Description: Natural variation in colony biofilm architecture is largely controlled by the cAMP-PKA pathway. CYR1 (adenylate cyclase) catalyzes cAMP production, activating PKA, which then regulates transcription factors controlling the expression of FLO11, encoding a key adhesion protein [25]. Allelic variation in pathway components, including CYR1, SFL1, FLO8, YAK1, and MSN2 contributes to phenotypic heterogeneity in biofilm formation through epistatic interactions [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Yeast Phenotypic Profiling

| Reagent/Category | Function/Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection | Genome-wide set of knockout strains | Fitness profiling, gene essentiality [6] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Library | Pooled guide RNA libraries for gene knockout | High-throughput functional genomics [6] |

| Cell Painting Dye Set | Multi-channel fluorescent dyes for organelles | Morphological profiling [26] |

| cAMP Analogues | Cell-permeable cAMP pathway modulators | Probing cAMP-PKA signaling in biofilms [25] |

| Low Glucose Agar | Media inducing biofilm formation | Colony architecture assays [25] |

| YPD Media | Standard rich growth medium | Routine culture and fitness assays [27] |

| Microtiter Plates | 96-well or 384-well plates | High-throughput phenotypic screening |

| Automated Imaging Systems | High-content microscopes | Morphological profiling and quantification |

Data Integration and Analysis Strategies