CGF vs. MLST: A Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Subtyping Performance for Outbreak Detection and Surveillance

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) and Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) for bacterial subtyping, tailored for researchers and public health professionals.

CGF vs. MLST: A Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Subtyping Performance for Outbreak Detection and Surveillance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) and Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) for bacterial subtyping, tailored for researchers and public health professionals. We explore the foundational principles of each method, detailing their transition from traditional to whole-genome sequencing-based applications. The methodological comparison covers discriminatory power, epidemiological concordance, and practical implementation through available software tools. We address common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for handling mixed samples and variable sequencing coverage. Finally, we synthesize validation studies and performance metrics from real-world outbreak investigations to guide method selection for specific research and surveillance objectives, underscoring the pivotal role of advanced subtyping in modern epidemiology.

Understanding the Core Principles: From Housekeeping Genes to Genomic Fingerprints

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) has stood as a cornerstone technique in molecular epidemiology since its introduction in 1998, providing a standardized, portable approach for the precise identification and differentiation of bacterial strains [1] [2]. This method revolutionized bacterial typing by moving from fragment-based sizing to unambiguous DNA sequence analysis, enabling robust interlaboratory comparisons and global surveillance of bacterial pathogens. By focusing on the nucleotide sequences of approximately seven carefully selected housekeeping genes—essential genes required for basic cellular functions—MLST generates unique allele profiles that facilitate accurate strain identification and in-depth evolutionary analysis [3]. The stability and conservation of these genetic loci provide the foundation for a typing system that balances sufficient variation for discrimination with enough conservation to reveal meaningful evolutionary relationships, establishing MLST as the historical "gold standard" against which newer methods are often measured, particularly in the context of epidemiological research and outbreak investigations.

The MLST Methodology: A Detailed Workflow

The conventional MLST process follows a meticulously defined pathway to transform bacterial isolates into comparable sequence types (STs). The workflow can be broken down into several critical stages, each contributing to the method's renowned reproducibility.

Experimental Protocol

The wet-lab procedure begins with the preparation of high-quality genomic DNA from bacterial isolates, requiring a total amount >500 ng and a concentration >10 ng/μL, with optimal purity (OD260/280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0) and no degradation or contamination [3]. The subsequent steps are:

- PCR Amplification: Using sequence-specific primers, each of the seven housekeeping gene loci is amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primer sets are designed to target internal fragments of approximately 400-600 base pairs in length [3] [1].

- Purification and Sequencing: The PCR amplicons are purified to remove enzymes, primers, and nucleotides that could interfere with sequencing. Historically, this has been performed using Sanger sequencing technology with BigDye Terminator chemistry on platforms such as the ABI 3100 or 3730 DNA analyzers [4].

- Sequence Assembly and Quality Control: The resulting sequences for each locus are assembled and checked for errors and overall quality using specialized software such as the SeqMan program within the Lasergene suite [4].

Data Analysis and Sequence Type Assignment

The bioinformatics phase translates raw sequence data into a standardized genotype:

- Allele Assignment: For each of the seven loci, the determined sequence is compared against a curated database of known alleles (e.g., on PubMLST). If the sequence perfectly matches a known allele, it is assigned the corresponding allele number. If it is a novel sequence, a new allele number is issued by the database [2].

- Profile and ST Determination: The combination of the seven allele numbers forms the isolate's allelic profile. This unique profile is then mapped to a Sequence Type (ST). Each unique profile receives a unique ST number, creating a portable and unambiguous identifier for the strain [3] [2].

- Advanced Analysis: Further bioinformatics analyses can include identifying polymorphic sites, population structure analysis, phylogenetic analysis, and recombination analysis, which help elucidate the genetic relationships and evolutionary history of the strains under investigation [3].

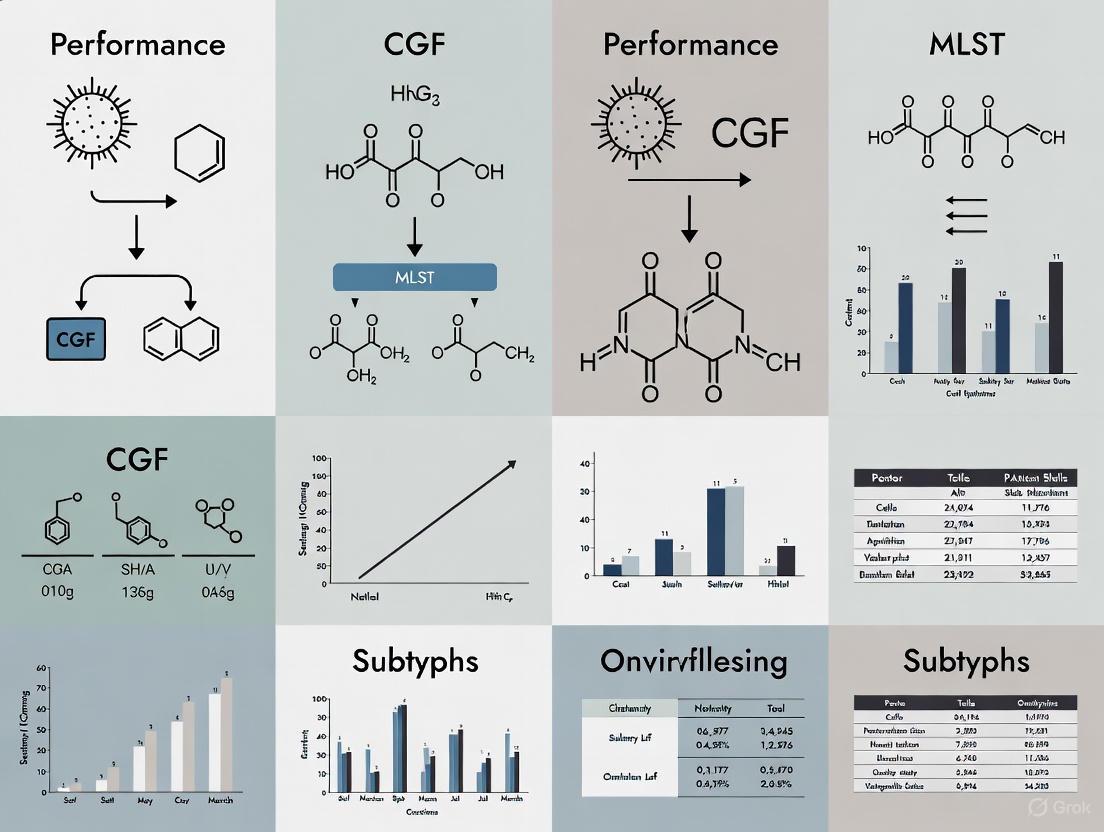

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from isolate to final sequence type.

MLST in a Evolving Typing Landscape: Comparison with CGF

While MLST has been a foundational tool, the field of molecular epidemiology continues to advance, leading to the development of new methods with higher resolution. One such method is Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF), which provides a contrasting approach to bacterial subtyping. The table below summarizes the core differences between these two techniques.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between MLST and CGF

| Feature | Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) | Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Target | Nucleotide sequence of ~7 core housekeeping genes [3] | Presence/absence of ~40 accessory genomic genes [4] [5] |

| Basis of Discrimination | Sequence variation (point mutations) in conserved genes [3] | Variation in gene content (insertions/deletions) in the accessory genome [4] |

| Primary Application | Long-term epidemiological and population studies, evolutionary analysis [4] [3] | Short-term outbreak investigations and high-resolution surveillance [4] [5] |

| Key Advantage | High portability, excellent for interlab comparisons and building global databases [4] [6] | Higher discriminatory power for distinguishing closely related isolates [4] |

| Typical Technology | Sanger sequencing [3] | Multiplex PCR [4] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The theoretical distinctions between MLST and CGF translate into measurable differences in performance. A validation study on Campylobacter jejuni directly compared the two methods using a set of 412 isolates from various sources. The key quantitative findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance comparison of CGF40 and MLST for C. jejuni subtyping [4]

| Method | Simpson's Index of Diversity (ID) | Clonal Complex (CC) ID | Sequence Type (ST) ID | Concordance with Reference Phylogeny |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGF40 | 0.994 | - | - | High (CGF and MLST are highly concordant) [4] |

| MLST | - | 0.873 | 0.935 | High [6] |

The significantly higher Simpson's index of diversity for CGF40 highlights its superior discriminatory power compared to MLST, which sometimes lacks the resolution needed for short-term investigations [4]. This enhanced resolution allows CGF to differentiate between closely related isolates that share an identical MLST Sequence Type, a capability crucial for pinpointing transmission routes in acute outbreak scenarios [4] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of MLST and CGF relies on a suite of specific reagents and materials. The following table details the key components required for the core experimental workflows.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for MLST and CGF

| Item | Function/Description | Typical Example/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Purification Kit | Extracts high-quality genomic DNA from bacterial cultures, free of contaminants that inhibit PCR or sequencing. | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [7], PureGene Genomic DNA Purification Kit [4] |

| PCR Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides designed to amplify the target loci (7 housekeeping genes for MLST; ~40 accessory genes for CGF). | Custom-designed primers [4] [7] |

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and buffers for efficient amplification of target genes. | Not specified in results, but essential for workflow. |

| PCR Purification Kit | Removes excess primers, enzymes, and dNTPs from PCR products prior to sequencing. | Montage PCR Centrifugal Filter Devices [4], QIAquick PCR Purification Kit [7] |

| Sequencing Chemistry | Fluorescently labeled di-deoxy terminators used in cycle sequencing reactions. | BigDye Terminator 3.1 [4] |

| Genetic Analyzer | Capillary electrophoresis instrument for separating and detecting fluorescently labeled DNA fragments. | ABI 3100 or 3730 DNA Analyzer [4] |

| Bioinformatics Software | For sequence assembly, quality control, allele calling, and phylogenetic analysis. | SeqMan (Lasergene) [4], BLAST [3] |

Advancements and Future Directions: The Evolution Beyond 7 Genes

The principle of multi-locus analysis established by MLST has evolved with technological progress. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has facilitated the development of more powerful, genome-scale typing methods [3] [8].

- Core Genome MLST (cgMLST): This approach expands the MLST concept to include hundreds of genes present in the core genome of a species, providing significantly higher resolution and discriminatory power than traditional 7-gene MLST [8] [1]. It is particularly valuable for distinguishing highly clonal outbreak strains.

- Whole Genome MLST (wgMLST): wgMLST goes a step further by analyzing variation across both the core and accessory genome, offering the highest possible resolution for strain typing by effectively comparing nearly the entire gene repertoire [3] [1].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) as the Ultimate Gold Standard: WGS is increasingly considered the new benchmark for microbial characterization. It provides a complete dataset from which any molecular type (MLST, cgMLST, CGF) can be derived in silico, and it enables the most comprehensive phylogenetic analyses and transmission tracking [6] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical and technological progression from traditional MLST to these more advanced genome-based typing methods.

MLST, with its foundation in the sequences of seven housekeeping genes, has earned its status as a gold standard in bacterial typing through its standardization, portability, and profound contribution to our understanding of bacterial population genetics and epidemiology. However, the escalating demands of public health surveillance and outbreak investigation for ever-greater resolution are steadily shifting the field toward genome-based methods like cgMLST and WGS. In this evolving landscape, methods like CGF have demonstrated that targeting the accessory genome can provide a high-resolution, highly deployable alternative for specific short-term applications. Therefore, while the seven genes of MLST remain a fundamental and historically crucial tool, the future of bacterial subtyping lies in the comprehensive and unparalleled power of the entire genome.

In the ongoing battle against bacterial pathogens, accurate strain typing is crucial for effective surveillance and outbreak investigations. Molecular subtyping methods allow researchers to differentiate bacterial isolates beyond the species level, enabling the tracking of contamination sources and the identification of transmission pathways. For decades, methods like Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) have served as valuable tools, but they can lack the resolution needed for short-term epidemiological investigations. To address this gap, Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) emerges as a rapid, high-resolution multiplex PCR approach that targets variable genomic regions, offering enhanced discriminatory power for bacterial subtyping.

What is Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)?

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting is a multiplex PCR-based method that exploits genetic variability in the accessory genome content of bacteria. Unlike MLST, which sequences segments of a few (typically seven) housekeeping genes, CGF simultaneously targets multiple loci (e.g., 40 genes in the CGF40 assay) distributed across the genome that demonstrate presence/absence variation among strains. This approach captures strain-to-strain relationships inferred from whole-genome comparative analysis, providing a higher-resolution fingerprint at a lower cost and faster turnaround than whole-genome sequencing.

The development of a CGF assay involves careful selection of target genes based on specific criteria: they should be accessory genes (absent in some strains), represent unbiased genes with adequate carriage across populations, be distributed across hypervariable genomic regions, and enable the reproduction of strain relationships seen in whole-genome analyses [4].

Head-to-Head: CGF Versus MLST Performance

Extensive validation studies have directly compared CGF with MLST, revealing important performance differences that researchers must consider when selecting a subtyping method.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CGF and MLST for Bacterial Subtyping

| Parameter | CGF (CGF40 Assay) | MLST | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discriminatory Power | Higher (Simpson's ID = 0.994) [4] | Lower (Simpson's ID = 0.935 for ST) [4] | CGF better differentiates closely related isolates within the same ST |

| Methodology Basis | Presence/absence of 40 accessory genes via multiplex PCR [4] | Nucleotide sequences of ~7 housekeeping genes [4] | CGF captures more genomic diversity; MLST focuses on core genome |

| Concordance with MLST | High (Wallace coefficient supports high concordance) [4] | N/A | CGF maintains phylogenetic relationships identified by MLST |

| Cost & Speed | Rapid, lower cost [4] | More expensive, slower [9] | CGF more suitable for high-throughput or resource-limited settings |

| Epidemiological Resolution | Superior for short-term investigations [4] | Better for long-term evolutionary studies [4] | CGF ideal for outbreak tracking; MLST for population genetics |

The significantly higher Simpson's index of diversity values obtained with CGF40 highlights its enhanced ability to distinguish between closely related bacterial isolates. This is particularly valuable for differentiating highly prevalent sequence types such as ST21 and ST45 in Campylobacter jejuni, where MLST may lack sufficient resolution [4]. Despite this higher discrimination, CGF and MLST show high concordance, meaning that CGF maintains the broader phylogenetic relationships established by MLST while providing additional resolution.

Inside the Black Box: Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CGF Assay Workflow

The technical implementation of CGF involves a structured process from gene selection to data analysis, each step critical to ensuring reproducible, high-quality results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CGF Implementation

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in CGF Protocol | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR Primers | Simultaneous amplification of multiple target loci | 40 gene-specific primers pooled in 8 multiplex reactions [4] |

| DNA Purification Kit | High-quality genomic DNA extraction | PureGene genomic DNA purification kit [4] |

| PCR Enzymes/Master Mix | Amplification of target genes | Phusion High-fidelity DNA Polymerase [10] |

| Thermal Cycler | Precise temperature cycling for PCR | Standard PCR thermal cycler |

| Electrophoresis System | Size separation of amplification products | Agarose gel electrophoresis or microfluidic chips |

Diagram 1: CGF experimental workflow for bacterial subtyping.

MLST Methodology

In contrast to CGF, MLST follows a different analytical pathway focused on sequence-based typing of core housekeeping genes:

Diagram 2: MLST methodology based on housekeeping gene sequencing.

The fundamental difference lies in what each method detects: CGF identifies the presence or absence of accessory genes through amplification pattern analysis, while MLST identifies sequence variations in core housekeeping genes through nucleotide sequencing [4].

Contextualizing CGF Within the Broader Molecular Typing Landscape

While CGF shows superior performance compared to MLST, it's important to understand how it fits alongside other typing methods used in modern microbiology laboratories.

Table 3: CGF Positioned Among Current Bacterial Typing Methods

| Method | Resolution | Turnaround Time | Cost | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGF | High | Days | $$ | Outbreak investigation, source tracking |

| MLST | Moderate | Days-Weaks | $$ | Population studies, long-term epidemiology |

| PFGE | Moderate | 3-4 days | $$ | Outbreak investigation (historical gold standard) |

| rep-PCR | High | <4 hours [9] | $ | Rapid screening, local surveillance |

| cgMLST | Very High | Weeks | $$$ | High-resolution outbreak investigation |

| WGS | Highest | Weeks | $$$$ | Comprehensive genetic analysis |

This comparison reveals CGF as a balanced option offering high resolution with moderate cost and time requirements, positioned between rapid but lower-resolution methods like rep-PCR and comprehensive but resource-intensive approaches like whole-genome sequencing (WGS) [8] [11].

The choice between CGF and MLST ultimately depends on the specific research question and practical constraints. CGF offers clear advantages when high discriminatory power is needed for short-term epidemiological investigations, such as outbreak detection and source tracking, particularly for highly diverse pathogens like Campylobacter jejuni [4]. Its cost-effectiveness and rapid turnaround make it deployable for routine surveillance.

MLST remains valuable for long-term epidemiological studies, evolutionary analysis, and global comparisons, as its sequence-based data are highly portable and standardized [4] [11]. The established MLST databases facilitate international collaboration and clone recognition.

For comprehensive surveillance programs, a tiered approach may be most effective: using CGF for high-resolution screening of potential outbreaks and MLST for placing isolates into global context. As sequencing costs continue to decline, WGS-based methods are becoming more accessible, but CGF remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for laboratories requiring high-resolution subtyping without the bioinformatics burden of whole-genome analysis.

The field of bacterial molecular subtyping has undergone a revolutionary shift with the advent of whole-genome sequencing (WGS). This transition has enabled the development of highly discriminatory in silico typing methods that are transforming outbreak investigation, pathogen surveillance, and phylogenetic studies. Among these methods, in silico Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) and Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) represent two powerful approaches that leverage WGS data to provide unprecedented resolution for strain differentiation [4] [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and technical requirements of these methods, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their selection of subtyping approaches for bacterial pathogen research.

Methodological Foundations and Principles

In Silico Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

Traditional MLST schemes characterize bacterial isolates based on the sequences of approximately seven housekeeping genes, assigning unique sequence types (STs) based on allele profiles [11] [12]. The in silico adaptation of this method extracts these allele sequences directly from WGS data, maintaining backward compatibility with established MLST databases while dramatically reducing turnaround time. This approach preserves the standardized nomenclature and global classification system that has made MLST invaluable for long-term epidemiological studies and population genetics [12]. Core genome MLST (cgMLST) expands this concept by utilizing hundreds to thousands of core genes distributed across the genome, offering significantly enhanced discriminatory power while maintaining the benefits of a standardized, portable nomenclature system [8] [13] [12].

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting represents a different philosophical approach, targeting genetic variability in the accessory genome content rather than conserved housekeeping genes. The CGF method employs multiplex PCR or in silico analysis of multiple loci widely distributed around the genome that demonstrate presence-absence variation among strains [4]. For example, the CGF40 assay for C. jejuni utilizes 40 gene targets selected based on five criteria: confirmed absence in one or more isolates from genomic surveys, unbiased distribution across populations, representative genomic distribution, ability to capture strain relationships from whole-genome analysis, and presence in multiple public genomes to enable SNP-free primer design [4]. This strategic selection of accessory gene targets provides resolution for differentiating closely related strains that may be indistinguishable by conventional MLST.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Discrimination Power and Typing Resolution

Multiple studies have quantitatively compared the discriminatory power of these subtyping methods, with CGF generally demonstrating superior resolution for short-term epidemiological investigations.

Table 1: Comparison of Discriminatory Power for Campylobacter jejuni Subtyping

| Typing Method | Simpson's Index of Diversity | Target Loci | Epidemiological Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGF40 | 0.994 | 40 accessory genes | High for outbreak detection |

| MLST (Sequence Type) | 0.935 | 7 housekeeping genes | Moderate for outbreak detection |

| MLST (Clonal Complex) | 0.873 | 7 housekeeping genes | Lower for outbreak detection |

As evidenced in a study of 412 C. jejuni isolates from various sources, CGF40 exhibited significantly higher discriminatory power than MLST, capable of differentiating within highly prevalent sequence types such as ST21 and ST45 that are challenging to resolve with conventional MLST [4]. The CGF approach effectively captures strain-to-strain relationships inferred from whole-genome comparative genomic analysis, making it particularly valuable for investigating potential outbreak clusters.

For other pathogens, cgMLST has demonstrated resolution comparable to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based analyses while offering advantages in standardization. In a study of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, cgMLST analysis was congruent with SNP-based phylogeny and epidemiological data, successfully contextualizing a multi-country outbreak [12]. Similarly, both cgMLST and coreSNP analyses showed superior discrimination compared to PFGE for Klebsiella pneumoniae surveillance, though cgMLST appeared inferior to coreSNP in phylogenetic reconstruction of the CG258 clonal group [8].

Technical Implementation and Workflow Considerations

The practical implementation of these methods varies significantly in terms of technical requirements, turnaround time, and data portability.

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Subtyping Method Implementation

| Parameter | In Silico MLST/cgMLST | Enhanced CGF |

|---|---|---|

| Primary data source | Whole-genome sequencing | Whole-genome sequencing or multiplex PCR |

| Analysis workflow | Assembly-based or read-mapping | Presence/absence calling of target loci |

| Scheme scalability | Highly scalable (7 to >2,000 loci) | Typically fixed (e.g., 40-50 loci) |

| Interlaboratory reproducibility | High with standardized schemes | High with defined gene targets |

| Database infrastructure | PubMLST, EnteroBase | Custom databases |

| Computational requirements | Moderate to high | Moderate |

In silico MLST and cgMLST typically employ either assembly-based approaches using tools like SPAdes, Shovill, or Unicycler, or read-mapping approaches using tools like Mentalist [13] [14]. The assembly-based approach can be impacted by genome composition characteristics such as repetitive sequences, insertion sequences, and GC content, potentially introducing variability in cgMLST results [13]. In contrast, CGF utilizes a more targeted analysis, assessing the presence or absence of predefined accessory gene targets, which can be implemented through PCR or in silico analysis of sequencing data [4].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

CGF40 Assay Development and Validation Protocol

The development and validation of the CGF40 method for C. jejuni provides a template for implementing enhanced CGF approaches:

Step 1: Marker Selection

- Identify prospective marker genes from comparative genomic surveys based on bimodal log ratio distributions indicating clear presence-absence patterns [4]

- Apply population frequency analysis to select unbiased genes with adequate carriage across datasets

- Ensure representative genomic distribution across hypervariable regions

- Verify ability to capture strain relationships inferred from whole-genome analysis

Step 2: Assay Design

- Extract orthologous sequences from available complete and draft genomes using BLAST

- Generate multiple sequence alignments for each set of orthologues using ClustalX

- Design SNP-free PCR primers using Primer3 for compatibility with both laboratory and in silico implementation [4]

- Assemble genes into multiplex PCRs (e.g., 8 multiplex PCRs targeting 5 loci each)

Step 3: Validation

- Compare performance against established typing methods (MLST, PFGE) using appropriate diversity measures

- Calculate Simpson's index of diversity to quantify discriminatory power

- Determine Wallace coefficients to assess concordance with existing methods

- Validate epidemiological concordance using isolates with known relationships [4]

cgMLST Implementation Protocol

For cgMLST implementation, the following protocol ensures reproducible results:

Step 1: Scheme Selection

- Select appropriate cgMLST scheme from public repositories (PubMLST, cgmlst.org)

- For A. baumannii, schemes containing 2,390 loci have been successfully implemented [14]

- For Salmonella enterica, schemes with 500-3,000 loci provide sufficient resolution

Step 2: Data Processing

- Perform quality control on sequencing reads using FastQC and multiQC [15] [14]

- Assemble genomes using optimized pipelines (SPAdes, Shovill, or Unicycler)

- Assess assembly quality using CheckM2 for completeness and contamination [14]

Step 3: Allele Calling

- Utilize chewBBACA or similar software for allele calling against the selected scheme [13] [14]

- Apply appropriate quality thresholds for allele calling

- Export allelic profiles for cluster analysis

Step 4: Cluster Analysis

- Use ReporTree with MSTreeV2 method for clustering at defined allelic difference thresholds (e.g., ≤9 alleles for closely related isolates) [14]

- Construct minimum spanning trees using GrapeTree

- Validate clusters with epidemiological data

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Bacterial Subtyping

| Item | Function | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| DNA extraction kits | High-quality genomic DNA isolation | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, Maxwell 16 Cell DNA Purification Kit |

| Whole-genome sequencing platforms | Generate raw sequence data | Illumina NextSeq500, NovaSeq 6000; PacBio |

| Assembly tools | Reconstruct genomes from sequencing reads | SPAdes, Shovill, Unicycler |

| cgMLST analysis software | Allele calling and profile generation | chewBBACA, Ridom SeqSphere+ |

| CGF analysis tools | Presence/absence calling of target loci | Custom scripts, BLAST-based pipelines |

| Typing databases | Scheme storage and profile comparison | PubMLST, EnteroBase, cgmlst.org |

| Phylogenetic visualization | Tree construction and annotation | GrapeTree, iTOL |

Analysis Workflow and Technical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows for implementing in silico MLST and enhanced CGF methods:

The transition to whole-genome sequencing has fundamentally transformed bacterial subtyping, enabling the development of highly discriminatory in silico methods like MLST/cgMLST and enhanced CGF. The experimental data and performance comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that CGF generally offers superior discriminatory power for outbreak investigations and short-term epidemiological studies, particularly for genetically diverse pathogens like Campylobacter jejuni [4]. In contrast, in silico MLST and cgMLST provide excellent resolution for population studies and long-term epidemiology while maintaining standardized nomenclature essential for global surveillance [11] [12].

The choice between these methods ultimately depends on research objectives, technical resources, and the specific pathogen under investigation. For outbreak investigations requiring high resolution among closely related strains, CGF approaches provide exceptional discriminatory power. For broader population studies and surveillance programs, cgMLST offers an optimal balance of resolution, standardization, and data portability. As WGS continues to become more accessible and bioinformatics tools further mature, both approaches will play increasingly important roles in public health microbiology and bacterial pathogen research.

Molecular subtyping of bacterial pathogens is a cornerstone of modern public health epidemiology, enabling outbreak detection, source tracking, and evolutionary studies. For years, Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) has served as the gold standard, providing a portable and reproducible system for classifying bacterial strains based on the sequences of a limited set of housekeeping genes [16]. However, the advent of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has facilitated the development of high-resolution methods, including Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) and core genome MLST (cgMLST), which offer significantly enhanced discrimination between closely related bacterial isolates [4] [17]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of CGF and MLST, focusing on the critical metrics of discriminatory power and epidemiological concordance, to inform researchers and public health professionals in selecting appropriate subtyping tools for outbreak investigations and surveillance.

Performance Comparison: CGF vs. MLST

The efficacy of a subtyping method is primarily evaluated based on its ability to distinguish between unrelated strains (discriminatory power) and its capacity to correctly group isolates from a common outbreak (epidemiological concordance). The table below summarizes a direct, quantitative comparison between a 40-gene CGF assay (CGF40) and standard MLST for Campylobacter jejuni [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CGF40 and MLST for Campylobacter jejuni Subtyping

| Performance Metric | CGF40 | MLST (Sequence Type) | MLST (Clonal Complex) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson's Index of Diversity | 0.994 | 0.935 | 0.873 |

| Primary Typing Method Wallace Coefficient (Concordance with MLST) | - | 0.82 (to Clonal Complex) | - |

| Secondary Typing Method Wallace Coefficient (Concordance with CGF40) | 0.99 (to Sequence Type) | - | - |

| Principle of Method | Presence/absence of 40 accessory genes | Nucleotide sequences of 7 housekeeping genes | Groups of related Sequence Types |

The data demonstrates that CGF40 exhibits a higher discriminatory power than MLST, as indicated by its superior Simpson's Index of Diversity (0.994 for CGF40 vs. 0.935 for MLST Sequence Types) [4]. This means CGF40 is more likely to distinguish between two unrelated C. jejuni isolates picked at random from the population. Furthermore, the high Wallace coefficient (0.99) indicates that isolates with an identical CGF40 profile almost always belong to the same MLST sequence type, confirming high concordance between the methods while the CGF40 provides finer resolution [4].

In the context of public health surveillance for outbreak detection, cgMLST (a method conceptually similar to CGF) has been validated for national surveillance systems. For Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), the U.S. PulseNet system defines a national cluster as five or more clinical cases within 60 days that are related within 0-10 allelic differences based on cgMLST [17]. This high-resolution clustering is crucial for identifying potential outbreaks rapidly and accurately.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Protocol for CGF40 Assay and Validation

The development and validation of a CGF assay, as exemplified for C. jejuni, involve a structured bioinformatics and laboratory workflow [4]:

- Marker Selection: Prospective gene targets are identified from comparative genomic surveys based on five criteria:

- Variable presence/absence across isolates (accessory genome).

- Unbiased carriage frequency (avoiding genes that are almost always present or absent).

- Representative genomic distribution across known hypervariable regions.

- Ability to recapitulate strain relationships inferred from whole-genome analysis.

- Conservation in multiple reference genomes to facilitate SNP-free primer design.

- Assay Design: For the CGF40 assay, 40 genes meeting the above criteria were selected. Orthologous sequences from available genomes are aligned, and PCR primers are designed in conserved regions to avoid single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The 40 targets are divided into 8 multiplex PCRs, each targeting 5 loci [4].

- Wet-Lab Analysis: Genomic DNA is extracted from bacterial isolates. The multiplex PCRs are run, and the presence or absence of each of the 40 amplicons is scored to generate a unique fingerprint for each isolate.

- Validation and Comparison: The performance of the CGF assay is validated against a established method like MLST. A collection of hundreds of isolates from diverse sources (e.g., agricultural, environmental, retail, clinical) is typed by both methods. Simpson's Index of Diversity is calculated for each method, and Wallace coefficients are determined to measure concordance [4].

Protocol for MLST and cgMLST Analysis

The standard and core-genome MLST workflows are as follows:

- Classical MLST:

- Locus Amplification and Sequencing: Seven designated housekeeping genes are PCR-amplified and sequenced using standard protocols [4] [18].

- Sequence Type Assignment: The sequence for each locus is compared to a curated database (e.g., PubMLST). Each unique sequence is assigned an allele number, and the combination of alleles across the seven loci defines a Sequence Type (ST) [16] [18].

- Clonal Complex Definition: Related STs are grouped into Clonal Complexes (CCs) using algorithms such as eBURST, which identifies groups of STs that share a recent common ancestor [19] [18].

- cgMLST for Outbreak Surveillance (as used in PulseNet 2.0):

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Isolate genomes are sequenced to high quality.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: The WGS data is processed through a standardized pipeline (e.g., the PulseNet 2.0 workflow) that includes quality assessment, de novo assembly, and allele calling for a scheme of hundreds to thousands of core genes [17].

- Cluster Detection: Genetic relatedness is assessed based on the number of allelic differences across the core genome. For STEC, an outbreak threshold of 0-10 allele differences is used to define a cluster [17].

- Concordance Validation: The performance of cgMLST is validated against other WGS-based methods like high-quality SNP (hqSNP) analysis and whole-genome MLST (wgMLST) by analyzing known outbreak isolates. Parameters such as pairwise genomic differences and clustering concordance (using tanglegrams and indices like Baker's Gamma Index) are evaluated to ensure epidemiological accuracy [17].

Workflow Diagram: Subtyping Method Evaluation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for evaluating and comparing bacterial subtyping methods, from isolate collection to performance metric calculation.

Subtyping Method Evaluation Workflow - This diagram shows the parallel processing of bacterial isolates through MLST and CGF/cgMLST protocols, followed by integrated analysis using epidemiological data to calculate key performance metrics.

Successful implementation and comparison of subtyping methods rely on specific laboratory reagents, bioinformatics tools, and reference databases.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Bacterial Subtyping Studies

| Category | Item | Function in Subtyping Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Reagents | Commercial DNA extraction kits | High-quality, pure genomic DNA is essential for reliable PCR and sequencing. |

| PCR Master Mix & Primers | For amplification of target loci in MLST and CGF assays. | |

| Sequencing Reagents/Kits | For determining nucleotide sequences of MLST amplicons or whole genomes. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BLAST Suite | For comparing sequence data against allele databases for MLST assignment [18]. |

| PYANI | For calculating Average Nucleotide Identity to assess genomic similarity [18]. | |

| GetHomologues/GetPhylomarkers | For identifying core genes and phylogenetic markers from WGS data [18]. | |

| RGI & CARD Database | For in silico prediction of antibiotic resistance genes from WGS data [18]. | |

| Reference Databases | PubMLST | Curated public repository for MLST allele and sequence type definitions [16]. |

| Kaptive | For capsule (K) and lipooligosaccharide (OCL) locus typing from WGS data [18]. | |

| NCBI GenBank/RefSeq | Primary databases for depositing and retrieving whole-genome sequence data. |

The comparative data clearly demonstrates that CGF and related core-genome methods offer superior discriminatory power for bacterial subtyping compared to traditional MLST, while maintaining high epidemiological concordance. This enhanced resolution is critical for detecting and investigating outbreaks, particularly for closely related strains where standard MLST may lack sufficient differentiation. The choice between methods depends on the specific application: MLST remains valuable for long-term phylogenetic and population structure studies, while CGF and cgMLST are better suited for high-resolution outbreak detection and short-term epidemiological investigations. The ongoing integration of these WGS-based methods into national surveillance networks, such as PulseNet 2.0, underscores their reliability and establishes them as the new benchmark for public health pathogen subtyping.

Implementation in the Lab and Field: A Practical Guide to Typing Workflows

The field of bacterial subtyping has been revolutionized by whole-genome sequencing (WGS), enabling a transition from traditional molecular techniques to comprehensive in silico analysis. This shift is particularly relevant in the broader context of comparing core genome MLST (cgMLST) against conventional multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) for bacterial subtyping research. While traditional MLST relies on sequencing 6-8 housekeeping genes, cgMLST expands this to hundreds or thousands of core genes, providing significantly enhanced resolution for outbreak investigation and population studies [20] [21]. Several computational tools have been developed to extract this typing information directly from raw sequencing data, bypassing the need for complete genome assembly. Among these, ARIBA, SRST2, and stringMLST have emerged as prominent solutions, each employing distinct algorithmic approaches with implications for their performance characteristics and suitability for different research scenarios [22] [23]. This review provides a comparative analysis of these three tools, evaluating their methodologies, performance metrics, and practical implementation to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate solution for their bacterial subtyping needs.

The fundamental algorithmic differences between ARIBA, SRST2, and stringMLST underlie their varied performance in accuracy, speed, and resource consumption.

SRST2: Read Mapping-Based Typing

SRST2 (Short Read Sequence Typing) represents a pioneering read mapping-based approach for gene detection and MLST typing. Its workflow begins by mapping Illumina sequencing reads against reference allele sequences using Bowtie2 with sensitive parameters [24] [25]. Following mapping, SAMtools generates pileups, which SRST2 analyzes using a sophisticated statistical scoring system. This system performs binomial tests at each position in the reference sequence to quantify evidence against the presence of each reference allele, accounting for sequencing error rates. The results are visualized using a quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot, where the slope of the fitted linear model serves as the allele score [25]. The allele with the lowest score (flattest slope) is identified as the best match, with outliers in the Q-Q plot typically indicating single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or indels relative to the reference. SRST2 reports the closest matching allele, average read depth, and flags potential novel alleles when exact matches are not found [25] [26].

ARIBA: Local Assembly-Based Typing

ARIBA (Antibiotic Resistance Identification By Assembly) employs a fundamentally different strategy centered on local de novo assembly. Rather than mapping reads directly to reference databases, ARIBA first maps reads to clustered reference sequences using Minimap, then performs local assembly of the mapped reads for each cluster using Fermi-lite [22] [26]. The resulting contigs are aligned to the best-matched reference sequence within each cluster using nucmer from the MUMmer package. This assembly-based approach provides ARIBA with several unique capabilities, including the determination of whether a queried coding sequence is complete and functional, or potentially disrupted by insertions or other structural variations [26]. ARIBA generates comprehensive flags for each allele call, detailing assembly quality and sequence characteristics, and provides functional predictions by distinguishing between synonymous and non-synonymous mutations [26].

stringMLST: k-mer Based Typing

stringMLST represents a third algorithmic paradigm, utilizing exact k-mer matching to completely bypass both read mapping and assembly processes. The tool builds a hash table data structure indexing all k-mers present in the MLST allele database [23] [20]. For each k-mer in the sequencing reads, stringMLST casts "votes" for all alleles containing that k-mer. The allele with the highest vote count for each locus is selected as the best match [20]. This k-mer counting approach eliminates computationally intensive alignment steps, making stringMLST exceptionally fast for traditional MLST schemes. However, this method may not scale efficiently to larger cgMLST schemes containing thousands of genes, a limitation addressed by next-generation k-mer tools like MentaLiST and STing [23] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Algorithmic Approaches

| Tool | Core Algorithm | Key Dependencies | Primary Input | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRST2 | Read mapping + statistical scoring | Bowtie2, SAMtools, SciPy | Raw sequencing reads (paired/single-end) | Best-matching alleles, consensus sequences, coverage metrics |

| ARIBA | Local assembly + contig alignment | Minimap, Fermi-lite, MUMmer, CD-HIT | Paired-end sequencing reads | Best-matching alleles, assembly flags, variant annotations |

| stringMLST | k-mer counting + voting | Custom k-mer index | Raw sequencing reads | Best-matching alleles, allele scores |

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of MLST Typing Tools

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Multiple studies have conducted systematic evaluations of MLST typing tools using both real and simulated datasets, providing insights into the relative performance of ARIBA, SRST2, and stringMLST across various metrics.

Accuracy and Typing Resolution

In comprehensive benchmarking studies, all three tools demonstrate high accuracy when evaluating traditional 7-gene MLST schemes under optimal sequencing conditions. A 2017 comparison of eight MLST software applications against real and simulated data found that SRST2 and ARIBA both achieved high accuracy in calling sequence types from WGS data [22]. SRST2 specifically demonstrated superior performance in detecting genes and alleles compared to assembly-based methods in its original validation [25].

For traditional MLST schemes, stringMLST achieves 100% accuracy in less than 10 seconds per isolate according to some reports [23]. However, its performance may degrade with larger cgMLST schemes containing thousands of genes, where tools like MentaLiST (a successor to stringMLST) show superior scalability while maintaining accuracy [20].

When evaluating the capability to identify both correct alleles and new alleles, a 2019 study comparing SRST2, stringMLST, and STRAIN on 540 samples found varying performance levels. SRST2 demonstrated approximately 90% accuracy for correct allele identification, while stringMLST achieved slightly lower accuracy at 85-90% for traditional schemes [27]. ARIBA's local assembly approach provides advantages in identifying structural variations and gene disruptions, offering functional insights beyond mere sequence presence [26].

Computational Performance and Resource Requirements

Computational efficiency varies substantially between the three tools, reflecting their different algorithmic approaches:

Table 2: Computational Performance Comparison

| Tool | Processing Speed | Memory Usage | Scalability to cgMLST | Ease of Installation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRST2 | Moderate (minutes per sample) | Moderate | Limited due to mapping overhead | Moderate (multiple dependencies) |

| ARIBA | Slower due to assembly step | Higher due to assembly | Moderate | Complex (multiple dependencies) |

| stringMLST | Very fast (seconds for traditional MLST) | Low | Limited for large schemes | Straightforward |

stringMLST typically demonstrates the fastest processing times for traditional MLST schemes, often completing typing in under 10 seconds per sample due to its efficient k-mer counting approach [23]. SRST2 requires moderate processing time (minutes per sample) due to the read mapping and statistical analysis steps [25]. ARIBA generally has the longest runtime due to its computationally intensive local assembly process [22] [26].

In terms of memory usage, stringMLST is the most efficient, followed by SRST2, while ARIBA typically requires the most memory due to its assembly component [22] [23]. For large-scale studies involving hundreds or thousands of isolates, these differences in computational requirements can significantly impact workflow feasibility.

Robustness to Challenging Sequencing Conditions

The performance of these tools under suboptimal sequencing conditions represents a crucial practical consideration for real-world applications:

Depth of Coverage: SRST2 has demonstrated reliable performance at coverages as low as 30x, though accuracy decreases substantially below this threshold [25]. stringMLST maintains accuracy down to approximately 20x coverage for traditional MLST schemes [23]. ARIBA's assembly-based approach requires higher coverage (typically >50x) for optimal performance, as low coverage can result in fragmented assemblies [26].

Sequence Contamination and Mixed Samples: SRST2 includes mechanisms to detect and flag mixed infections or contaminated samples by identifying multiple alleles at individual loci [25]. ARIBA's assembly approach can potentially separate contaminating sequences through its clustering algorithm [22]. stringMLST may struggle with mixed samples as its k-mer voting system assumes a pure isolate [23].

Novel Allele Detection: SRST2 flags potential novel alleles when exact matches are not found and can generate consensus sequences for further investigation [25]. ARIBA provides detailed information about variations from reference sequences, facilitating novel allele identification [26]. stringMLST has limited capability for novel allele characterization compared to the other tools [27].

Experimental Design and Implementation

Benchmarking Protocols

Robust evaluation of MLST typing tools requires carefully designed benchmarking approaches that assess performance across diverse conditions:

Reference Dataset Validation: Studies typically employ datasets with known sequence types determined by conventional methods. For example, one comprehensive comparison used datasets from the Gen-FS WGS Standards and Analysis Working Group, including C. jejuni, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and S. enterica [22]. The validation of SRST2 utilized over 900 genomes from common pathogens with known MLST types [25].

Simulated Data Analysis: To systematically evaluate tool performance under controlled conditions, researchers often employ simulated reads with varying coverage depths (e.g., from 10x to 100x) and known contamination levels [22]. This approach allows for precise assessment of accuracy limits and failure modes.

Computational Resource Profiling: Benchmarking studies typically execute tools on standardized computing infrastructure while monitoring runtime, peak memory usage, and disk I/O through multiple iterations to ensure reproducible performance measurements [23] [20].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MLST Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in MLST Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | PubMLST, BIGSdb, CARD, EnteroBase | Provide curated allele sequences and ST profiles for accurate typing |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq, Nanopore | Generate raw sequencing data for input to typing tools |

| Alignment Tools | Bowtie2, Minimap, BWA | Perform read alignment for mapping-based approaches (SRST2, ARIBA) |

| Assembly Algorithms | SPAdes, Velvet, Fermi-lite | Reconstruct contiguous sequences from reads (ARIBA) |

| k-mer Counters | KAnalyze, Jellyfish | Index and count k-mers for k-mer-based approaches (stringMLST) |

| Programming Environments | Python, R, Julia, Perl | Provide execution environments for analysis tools and scripts |

Discussion and Practical Recommendations

Within the broader context of comparing CGF (cgMLST) versus traditional MLST for bacterial subtyping research, the selection of an appropriate typing tool depends on several factors, including the research question, scale of the study, available computational resources, and required resolution.

For traditional MLST schemes (6-8 genes) where speed is prioritized, stringMLST provides the fastest processing time with minimal computational resources, making it suitable for high-throughput screening of large isolate collections [23]. However, researchers should be aware of its limitations in detecting novel alleles and scaling to larger schemes.

For studies requiring comprehensive gene detection with functional interpretation, ARIBA offers advantages through its local assembly approach, which provides information about gene completeness and disruption [26]. This makes it particularly valuable for antimicrobial resistance studies where gene integrity correlates with phenotype.

For balanced performance across accuracy, novel allele detection, and reasonable computational requirements, SRST2 remains a robust choice, particularly for clinical and public health laboratories [25]. Its mapping-based approach provides reliable typing while flagging potential novel variants for further investigation.

For large-scale cgMLST schemes involving hundreds to thousands of genes, next-generation tools like MentaLiST and STing may be more appropriate than the three tools reviewed here, as they implement optimized k-mer algorithms specifically designed for scalability [23] [20]. These tools represent the evolving landscape of in silico typing methods that can keep pace with expanding genome-scale typing schemes.

As the field moves toward core genome and whole genome MLST approaches, computational efficiency and scalability become increasingly critical. The methodological differences between mapping-based, assembly-based, and k-mer-based approaches will continue to influence tool selection as typing schemes expand in size and complexity. Researchers should consider both their immediate typing needs and future directions when selecting tools for bacterial subtyping workflows.

Molecular typing methods are fundamental to bacterial subtyping for epidemiological surveillance, outbreak detection, and source attribution. The selection of an appropriate method balances discriminatory power, reproducibility, cost, and throughput. This guide objectively compares two established approaches: Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) and Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST), framing them within a broader thesis on their comparative performance for bacterial subtyping research. We detail the experimental workflows from raw sequencing data to final typings, supported by performance data and protocol details to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The evolution from traditional methods like pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) towards sequence-based techniques has marked a paradigm shift in molecular epidemiology. MLST has provided a portable, reproducible system based on the sequences of internal fragments of housekeeping genes. In contrast, CGF leverages the presence or absence of accessory genes to generate highly discriminatory genetic fingerprints, offering a potentially more deployable solution for large-scale surveillance [28] [29] [5].

Methodological Principles and Workflows

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST)

Principle: MLST is a nucleotide sequence-based approach that characterizes bacterial isolates using the sequences of internal fragments of typically seven housekeeping genes. Each unique sequence for a gene is assigned an allele number, and the combination of alleles across all loci defines the Sequence Type (ST), providing an unambiguous profile for each isolate [30].

Workflow: The standard MLST workflow can be applied to both assembled genomes and raw sequencing reads.

- Input: The process begins with either assembled draft genomes/contigs in FASTA format or raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format. For paired-end reads, two files per sample are required, distinguished by patterns (e.g.,

_1and_2) [30]. - Processing: For raw reads, the first step involves quality control, including trimming of low-quality bases and adapter sequences. The target loci are then identified within the data.

- Alignment & Typing: The sequences of the housekeeping genes are extracted and aligned against a species-specific scheme of known alleles from a database like PubMLST. For each locus, the algorithm determines the best-matching allele based on identity and coverage [30].

- Result Interpretation: The output specifies the Sequence Type and flags any discrepancies:

- Matched: Complete match with all alleles (100% identity and coverage).

- Partial: Potential errors or novel SNPs detected (average identity/coverage ≤99%).

- Not Matched: No match found, often due to an incorrect MLST scheme selection [30].

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)

Principle: CGF is a multiplex PCR-based method that detects the presence or absence of a carefully selected set of accessory genes. These genes, identified through comparative genomic analysis as having high intraspecies variability, create a unique binary fingerprint for each strain. This method focuses on the accessory genome, which can provide higher resolution than methods targeting only core genes [28] [5].

Workflow: The development and application of CGF involve a structured process.

- Assay Development: This foundational phase involves whole-genome sequencing of diverse reference strains. Comparative genomic analysis identifies accessory genes with variable presence across the population. A final set of targets (e.g., 40 genes for CGF40) is selected through optimization to ensure high discrimination and concordance with a reference phylogeny [5].

- Sample Processing: DNA is extracted from bacterial isolates.

- Multiplex PCR: A multiplex PCR reaction is performed targeting the predefined set of accessory genes.

- Detection & Profiling: The presence or absence of each amplicon is detected, typically using capillary electrophoresis or microarrays, to generate a binary profile [28] [5].

- Cluster Analysis: Profiles are compared, and isolates are grouped into clades based on profile similarity (e.g., ≥90%) for epidemiological interpretation [5].

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways from raw data to final output for both methods, highlighting their parallel yet distinct processes.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice between CGF and MLST involves trade-offs between resolution, throughput, and cost. The table below summarizes their performance characteristics based on experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CGF and MLST for Bacterial Subtyping

| Feature | Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) | Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) |

|---|---|---|

| Typing Principle | Presence/absence of accessory genes [28] [5] | Allelic profile of 7-8 housekeeping genes [29] [30] |

| Discriminatory Power | High; can differentiate closely related strains with distinct epidemiology [28] [5] | Medium; may lack resolution within common Sequence Types [29] |

| Throughput | High; suitable for large-scale surveillance [5] | Medium; more resource-intensive and lower throughput than CGF [5] |

| Reproducibility | High (98.6% reproducibility demonstrated) [5] | Very high; unambiguous sequence-based data [29] |

| Cost & Deployment | Lower cost; highly deployable for routine use [5] | Higher cost; can be cost-prohibitive for large studies [29] [5] |

| Data Portability | Binary profile; requires standardized gene set | Excellent; standardized, portable STs via curated databases (e.g., PubMLST) [28] [29] |

| Epidemiological Concordance | High concordance with outbreaks; identifies relevant clusters [28] | Good for long-term epidemiology; may miss recent outbreaks [28] |

| Representative Performance Metric | Simpson's Index of Diversity (ID) > 0.969 for CGF40 assay on A. butzleri [5] | Found 25% of isolates part of clusters in a sentinel surveillance study [28] |

Experimental data directly comparing these methods highlights their respective strengths. In a study on Campylobacter, CGF was identified as one of the optimal methods for detecting epidemiologically relevant clusters of cases. It could be effectively supplemented by flaA SVR sequencing, with or without MLST. The study concluded that different methods are optimal for uncovering different aspects of source attribution, and using multiple methods reveals more about a population than any single method alone [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: MLST from Raw Reads

This protocol is adapted from standard procedures used in public health and research laboratories [28] [30].

- DNA Extraction & Input Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from bacterial isolates. The input for an MLST pipeline can be either:

- Raw Sequencing Reads: in FASTQ format (single or paired-end).

- Assembled Draft Genome: in FASTA format.

- Quality Control (for Raw Reads): Process raw reads using tools like Trimmomatic to remove low-quality bases, adapter sequences, and short reads. This step is crucial for ensuring accurate sequence alignment [31] [30].

- Scheme Selection: Select the appropriate species-specific MLST scheme from a curated database (e.g., PubMLST). Using an incorrect scheme will result in failed typing [30].

- Locus Identification & Allele Calling: The analysis tool (e.g., a dedicated MLST software) maps the reads or assembled contigs to the reference alleles for the seven housekeeping genes. For each locus, it determines the best-matching allele based on percentage identity and coverage [30].

- Sequence Type Assignment: The combination of the seven allele numbers defines the Sequence Type (ST). This ST is queried against the database to determine if it is a known or novel type. Results are often categorized as "Matched," "Partial" (indicating potential novel SNPs), or "Not Matched" [30].

Protocol: CGF Assay Implementation

This protocol is based on the development and application of CGF for pathogens like Campylobacter jejuni and Arcobacter butzleri [28] [5].

- CGF Assay Selection: Utilize a pre-defined set of accessory gene targets validated for the specific bacterial species. For example, the CGF40 assay for A. butzleri uses 40 genes selected for high discrimination and concordance with a reference phylogeny [5].

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from bacterial isolates.

- Multiplex PCR: Perform a single, optimized multiplex PCR reaction that amplifies all target accessory genes simultaneously.

- Amplicon Detection & Scoring: Separate and detect the PCR amplicons using a platform such as capillary electrophoresis. Score each gene in the assay as "present" (1) or "absent" (0) based on the detection of its respective amplicon.

- Profile Analysis & Clustering: Analyze the binary profile of the isolate. Use a similarity coefficient (e.g, Jaccard) and cluster analysis (e.g., UPGMA) to group isolates into clades. A similarity threshold of ≥90% is often used to define clusters of genetically related isolates for epidemiological investigations [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these typing workflows requires specific laboratory and bioinformatics reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Typing Workflows

| Item | Function in Workflow | Application |

|---|---|---|

| PureGene DNA Purification Kit | Genomic DNA purification from bacterial isolates, providing high-quality template for PCR or sequencing [28]. | CGF & MLST |

| PubMLST Database | Centralized repository for MLST schemes, allele sequences, and Sequence Type profiles, ensuring standardization and portability [28] [30]. | MLST |

| Trimmomatic | Bioinformatics tool for pre-processing raw FASTQ files; removes adapter sequences and trims low-quality bases to improve downstream analysis [31]. | MLST |

| Medifuge MF200 Centrifuge | Specialized centrifuge used in the preparation of samples, such as for concentrating growth factors or bacterial cells, prior to DNA extraction [32]. | Sample Prep |

| Bowtie 2 / Kraken 2 | Bioinformatics tools for read alignment and taxonomic classification, useful for filtering out contaminating reads from samples before targeted assembly or analysis [31]. | MLST |

| CGF Optimizer Software | Bioinformatic tool used to select an optimal subset of accessory genes for a CGF assay that maintains high concordance with a reference phylogeny [5]. | CGF |

| ChromatoGate | Open-source software for semi-automatic inspection of chromatograms from Sanger sequencing, aiding in the detection and correction of base mis-calls to ensure sequence accuracy [33]. | MLST (Sanger) |

Both CGF and MLST offer robust pathways from raw sequencing data to a definitive strain type or fingerprint, yet they serve complementary roles in the molecular epidemiologist's toolkit. MLST provides a standardized, portable, and phylogenetically meaningful framework ideal for global surveillance and population biology studies. In contrast, CGF offers a higher-resolution, high-throughput, and cost-effective alternative that is exceptionally well-suited for rapid outbreak detection and source tracking where fine-scale discrimination is required.

The decision between them should be guided by the specific research question, available resources, and desired balance between portability and discriminatory power. As whole-genome sequencing becomes increasingly accessible, methods like core-genome MLST (cgMLST) are emerging as new gold standards [29]. However, until WGS is universally deployable, CGF and MLST remain vital and highly effective methods for bacterial subtyping.

Sentinel surveillance systems are a cornerstone of public health, serving as an early-warning mechanism to detect clusters of infectious diseases before they become widespread outbreaks. For bacterial pathogens like Campylobacter and Salmonella, the effectiveness of these systems hinges on the resolution and speed of the molecular subtyping methods used to distinguish between strains [ [28]]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two prominent subtyping methods—Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)—evaluating their performance, protocols, and applicability within modern sentinel surveillance frameworks.

To understand their comparative performance, it is essential to first define the fundamental principles and technical execution of each method.

Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

MLST is a gold-standard, sequence-based technique that characterizes bacterial isolates by sequencing approximately 450-500 bp internal fragments of seven housekeeping genes. The sequences for each locus are assigned as distinct alleles, and the combination of alleles across the seven genes defines the sequence type (ST) of the isolate. This method is highly reproducible and portable, making it excellent for long-term, global epidemiological studies and population genetics [ [4] [28]].

Workflow Diagram: MLST

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)

CGF is a higher-resolution, PCR-based method that targets genomic variation within the accessory genome. Instead of sequencing, it detects the presence or absence of multiple, highly variable marker genes distributed across the genome. The CGF40 assay, for example, uses a 40-gene multiplex PCR panel to generate a binary fingerprint for each isolate. This fingerprint reflects strain-specific genetic content and has been shown to provide greater discriminatory power than MLST [ [4]].

Workflow Diagram: CGF

Head-to-Head Performance Comparison

The core of this guide lies in the direct, data-driven comparison of CGF and MLST, focusing on metrics critical for sentinel surveillance.

Key Performance Metrics for Sentinel Surveillance

The table below summarizes experimental data from a validation study of 412 C. jejuni isolates from various sources, directly comparing CGF40 and MLST [ [4]].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CGF40 and MLST

| Feature | MLST (Sequence Type) | MLST (Clonal Complex) | CGF40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson's Index of Diversity (ID) | 0.935 | 0.873 | 0.994 |

| Primary Target | Core genome (housekeeping genes) | Core genome (housekeeping genes) | Accessory genome (variable genes) |

| Methodology | Sequencing & allele assignment | Sequencing & clonal complex assignment | Multiplex PCR & presence/absence profiling |

| Discriminatory Power | High | Moderate | Very High |

| Cost & Speed | Higher cost, slower turnaround | Higher cost, slower turnaround | Lower cost, rapid results |

| Best Application | Long-term epidemiology, population structure | Long-term epidemiology, population structure | Short-term outbreak detection, cluster investigation |

Interpretation of Comparative Data

- Discriminatory Power: The significantly higher Simpson's Index of Diversity for CGF40 (0.994) demonstrates its superior ability to differentiate between closely related bacterial isolates. This is crucial in sentinel surveillance for distinguishing outbreak clusters from a background of sporadic cases, particularly for common sequence types like ST21 and ST45 of C. jejuni [ [4]].

- Epidemiological Concordance: Despite its higher resolution, CGF maintains high concordance with MLST. Isolates that are identical by MLST often resolve into distinct but highly similar CGF profiles, confirming their relatedness while revealing finer-scale transmission patterns [ [4]].

- Operational Utility: CGF is noted for being rapid, lower in cost, and more easily deployable for routine surveillance compared to the more laborious and expensive sequencing required for MLST [ [4] [28]].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

For researchers seeking to validate or implement these methods, the following summarized protocols are essential.

Detailed CGF40 Assay Protocol

The CGF40 method for C. jejuni, as described by Taboada et al., can be broken down into key stages [ [4]]:

- Marker Selection and Assay Design: Forty target genes were selected based on five criteria:

- Documented absence in one or more strains from prior genomic surveys.

- Unbiased carriage across population datasets (avoiding universally present/absent genes).

- Representative genomic distribution across 16 major hypervariable regions.

- Ability to recapitulate strain relationships from whole-genome analysis.

- Presence in multiple reference genomes to allow for SNP-free PCR primer design.

- Primer Design and Multiplexing: SNP-free PCR primers were designed for each of the 40 targets. These were assembled into 8 multiplex PCRs, each targeting 5 distinct loci.

- Wet-Lab Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit (e.g., PureGene) for high-quality genomic DNA.

- Multiplex PCR: Perform the 8 parallel PCR reactions under optimized conditions.

- Data Generation: Analyze PCR products to generate a binary presence/absence profile for all 40 loci.

- Data Analysis and Fingerprinting: The combined profile is used to generate a comparative genomic fingerprint for cluster analysis.

Standard MLST Protocol

The standard MLST protocol for C. jejuni, as referenced in the studies, follows these steps [ [4] [28]]:

- DNA Extraction: Use a standardized method (e.g., PureGene kit) for genomic DNA preparation.

- PCR Amplification: Independently amplify the seven housekeeping genes (aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt, uncA).

- Sequencing and Assembly: Purify PCR amplicons (e.g., using Montage PCR centrifugal filters) and perform Sanger sequencing. Assemble and check sequences for quality using software like SeqMan.

- Allele and ST Assignment: Query the curated Campylobacter PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/) to assign allele numbers and determine the final Sequence Type.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for CGF and MLST Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Purification Kit | Isolation of high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA from bacterial isolates. | PureGene Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems) [ [4]] |

| PCR Primers | Specific amplification of target loci (7 for MLST, 40 for CGF). | Custom-designed primers; for CGF, assembled into multiplex reactions [ [4]] |

| PCR Purification Kit | Post-amplification cleanup of PCR products prior to sequencing (for MLST). | Montage PCR Centrifugal Filter Devices [ [4]] |

| Cycle Sequencing Kit | Sanger sequencing of amplified gene fragments (for MLST). | BigDye Terminator 3.1 Chemistry (Applied Biosystems) [ [4]] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Separation and detection of sequenced fragments (for MLST). | ABI 3100 or 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) [ [4]] |

| Sequence Assembly & Analysis Software | Assembly of sequencing reads, quality control, and allele calling. | SeqMan (DNASTAR Lasergene suite) [ [4]] |

| Curated MLST Database | Centralized resource for allele and sequence type assignment. | PubMLST (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/) [ [28]] |

The choice between CGF and MLST for sentinel surveillance is not a matter of identifying a single superior technique, but of selecting the right tool for the specific public health question. CGF offers a powerful, high-resolution, and cost-effective solution for the real-time detection and investigation of disease clusters, making it highly suitable for routine surveillance and outbreak management. In contrast, MLST remains the definitive method for understanding long-term, global population structures and evolutionary relationships.

The field continues to evolve, with Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)-based methods like core genome MLST (cgMLST) emerging as powerful successors that offer ultimate resolution and standardization [ [34]]. However, for many laboratories, the balance of speed, cost, and discriminatory power ensures that CGF remains a highly relevant and effective tool for protecting public health through robust sentinel surveillance.

Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most common bacterial causes of gastroenteritis worldwide, representing a significant public health and socioeconomic burden [35] [36]. Despite its high incidence, tracking the sources of sporadic campylobacteriosis remains challenging, primarily due to the limitations of existing molecular typing methods in unambiguously linking genetically related strains [35]. The genomic evolution of Campylobacter is characterized by frequent rearrangements and interstrain genetic exchange, which complicates the interpretation of molecular typing data for outbreak investigations [35] [6].

Multiple molecular subtyping methods have been developed for Campylobacter, including multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), flagellin gene typing (flaA-SVR), porA gene typing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [35] [28]. While these methods have advanced our understanding of Campylobacter epidemiology, they present limitations for routine surveillance and outbreak detection, including insufficient discriminatory power, high costs, technical complexity, and prolonged turnaround times [37] [28].

This case study examines Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) as an optimal method for Campylobacter outbreak detection. We evaluate its performance against established typing methods, with a particular focus on its application in public health surveillance and epidemiological investigations.

Understanding the Typing Landscape for Campylobacter

Established Typing Methods and Their Limitations

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), which analyzes DNA sequences of seven housekeeping genes, has become a leading method for Campylobacter subtyping due to its portability and ease of interlaboratory comparison [35] [4]. However, MLST may lack sufficient resolution for short-term investigations aimed at identifying temporally and spatially related clusters from common sources [4]. Additionally, MLST is resource-intensive and relatively low-throughput, limiting the number of isolates that can be analyzed in most laboratory settings [5].

Single-locus methods such as flaA-SVR and porA typing offer simpler alternatives but provide less discriminatory power than multi-locus approaches [35] [28]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) has been valuable for outbreak investigations but is of limited value for Campylobacter due to chromosomal rearrangements and high genetic diversity that may limit the clustering of related isolates [4].

The Emergence of Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF)

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting was developed to overcome the technical and logistical hurdles of implementing Campylobacter typing in routine surveillance [37] [4]. This method uses a multiplex PCR approach to detect the presence or absence of multiple genes in the accessory genome, creating a binary fingerprint that distinguishes strains based on differences in genome content [4].

The CGF40 assay, which targets 40 accessory genes, was specifically designed as a rapid, low-cost, and high-resolution subtyping method suitable for large-scale epidemiological surveillance [4] [38]. The selection of target genes was based on comprehensive genomic analyses, choosing markers with adequate carriage across populations and a representative genomic distribution to ensure optimal discrimination of strains [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Campylobacter Subtyping Methods

| Method | Target | Discriminatory Power | Throughput | Cost | Technical Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGF40 | Accessory genome (40 genes) | High (ID: 0.994) [4] | High | Low | Moderate |

| MLST | Core genome (7 housekeeping genes) | Moderate (ID: 0.935) [4] | Low | High | High |

| flaA-SVR | Single locus (flagellin gene) | Low [35] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| porA | Single locus (porin gene) | Low [35] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| PFGE | Whole genome macrorestriction | Variable [4] | Low | Moderate | High |

Comparative Performance: CGF Versus MLST

Discriminatory Power and Resolution

Multiple studies have demonstrated that CGF40 provides superior discriminatory power compared to MLST. In a comprehensive validation study analyzing 412 C. jejuni isolates from various sources, CGF40 exhibited a Simpson's index of diversity (ID) of 0.994, significantly higher than MLST at both the sequence type (ST) level (ID = 0.935) and clonal complex (CC) level (ID = 0.873) [4].