Breaking the Bottleneck: Strategies to Overcome NGS Data Analysis Challenges in Chemogenomics

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become indispensable in chemogenomics for uncovering the genetic basis of drug response and toxicity.

Breaking the Bottleneck: Strategies to Overcome NGS Data Analysis Challenges in Chemogenomics

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become indispensable in chemogenomics for uncovering the genetic basis of drug response and toxicity. However, the transition from raw sequence data to clinically actionable insights is hampered by significant bottlenecks, including data deluge, rare variant interpretation, and analytical inconsistencies. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these challenges from foundational principles to advanced applications. We explore the unique data analysis demands in chemogenomics, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches leveraging AI and automation, provide proven optimization strategies for robust workflows, and discuss validation frameworks to ensure reliable, clinically translatable results. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accelerate drug discovery and development through more efficient and accurate NGS data analysis.

The Chemogenomics Data Deluge: Understanding the Scale and Source of NGS Bottlenecks

The Unique Data Analysis Demands of Chemogenomics

Core Concepts of Chemogenomics

What is chemogenomics and what kind of data does it generate?

Chemogenomics is a powerful approach that studies cellular responses to chemical perturbations. In the context of genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens, it identifies genes whose knockout sensitizes or suppresses growth inhibition induced by a compound [1]. This generates a genetic signature that can decipher a compound's mechanism of action (MOA), identify off-target effects, and reveal chemo-resistance or sensitivity genes [1].

What are the primary goals of a chemogenomic screen?

The primary goals are to:

- Confirm the mechanism of action (MOA) of a compound.

- Identify potential secondary off-target effects.

- Discover genetic vulnerabilities suggesting innovative drug combination strategies.

- Identify novel gene functions involved in the cellular mechanism targeted by a compound [1].

Troubleshooting NGS Data Analysis in Chemogenomics

How do I address low sequencing library yield from my chemogenomic screen?

Low library yield can halt progress. The following table outlines common causes and corrective actions based on established NGS troubleshooting guidelines [2].

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality / Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition from residual salts, phenol, or EDTA [2]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure wash buffers are fresh; target high purity (260/230 > 1.8) [2]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Under-estimating input concentration leads to suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry [2]. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV absorbance; calibrate pipettes; use master mixes [2]. |

| Fragmentation Inefficiency | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation efficiency [2]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragmentation profile before proceeding [2]. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect molar ratios reduce adapter incorporation [2]. | Titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; maintain optimal temperature [2]. |

My chemogenomic data shows high duplicate reads and potential batch effects. How can I fix this?

Over-amplification during library prep is a common cause of high duplication rates, which reduces library complexity and statistical power [2]. Batch effects from processing samples across different days or operators can also introduce technical variation.

Solutions:

- Optimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for library amplification to avoid over-amplification artifacts [2].

- Randomize Samples: Process samples randomly across batches to prevent confounding technical effects with biological conditions.

- Automate Library Prep: Consider automated liquid handlers to improve reproducibility. For example, the ExpressPlex kit requires only two pipetting steps prior to thermocycling, significantly reducing manual error [3].

- Use Multiplexing Kits: Employ kits with high auto-normalization capabilities to achieve consistent read depths across samples without individual normalization, reducing preparation variability [3].

What are the best practices for ensuring my bioinformatics workflows are robust and reproducible?

Inefficient or error-prone bioinformatics pipelines can become a major bottleneck, leading to delays, increased costs, and inconsistent results [4].

Methodology for Robust Workflow Development:

- Adopt Modern Frameworks: Migrate legacy in-house workflows to modern, cloud-friendly frameworks like Nextflow and utilize community resources like nf-core for standardized, version-controlled pipelines [4].

- Implement Continuous Integration/Deployment (CI/CD): Set up automated testing for your bioinformatics pipelines to ensure any changes do not break existing functionality and to guarantee reproducibility [4].

- Enable Cross-Platform Deployment: Design workflows to be portable across different computing environments (e.g., Local HPC, Cloud like AWS/Azure) without modification for scalable and flexible analysis [4].

- Utilize Workflow Automation: Implement automatic pipeline triggers upon data arrival to reduce manual intervention and tracking errors, ensuring a consistent analysis path for every dataset [4].

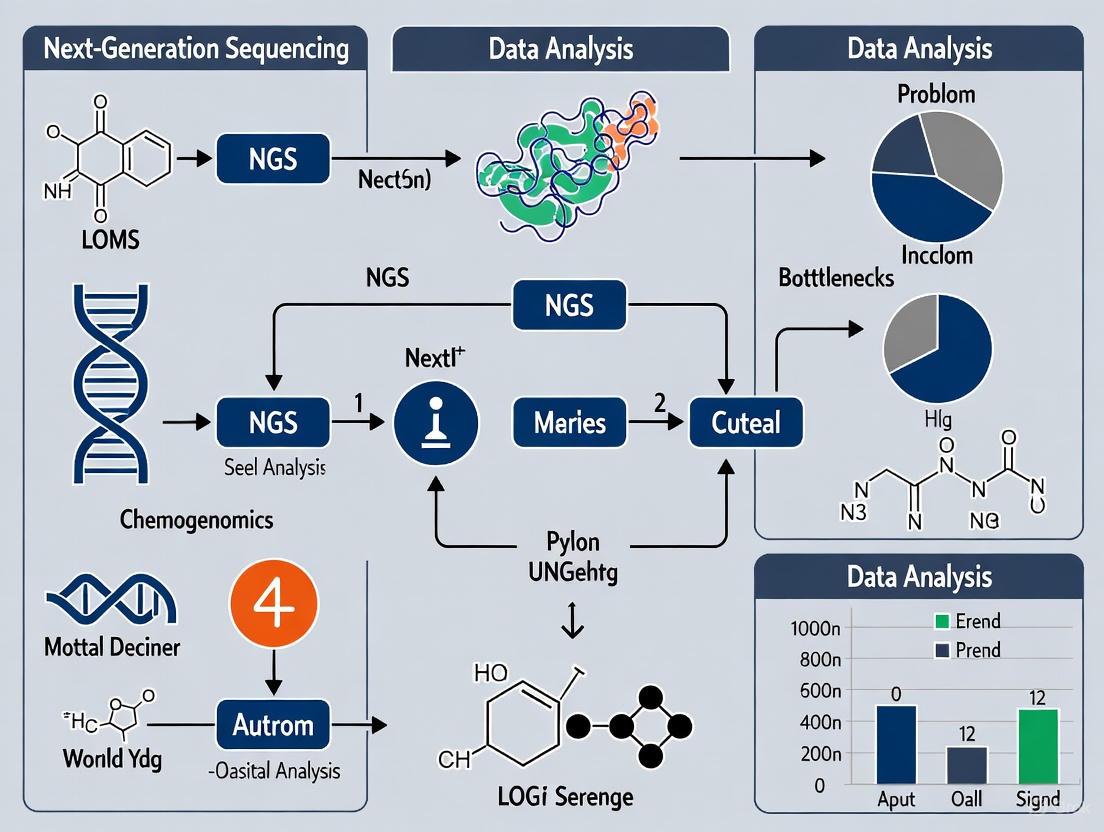

Chemogenomic NGS Analysis Pipeline

FAQs on Experimental Design & Interpretation

What defines a high-quality chemical probe for a chemogenomic screen?

A high-quality chemical probe is a selective small-molecule modulator – usually an inhibitor – of a protein’s function that allows mechanistic and phenotypic questions about its target in cell-based or animal research [5]. Unlike drugs, probes prioritize selectivity over pharmacokinetics.

Key criteria include [5]:

- Selectivity: Demonstrated activity against the intended target with minimal interaction against a panel of related targets.

- Potency: Sufficient cellular activity at the intended dose.

- Target Engagement: Validation that the probe binds to its intended target in the model system used.

- Negative Controls: Availability of an inactive, structurally related control compound.

Why is the use of orthogonal probes and negative controls critical?

The use of two structurally distinct chemical probes (orthogonal probes) is critical because they are unlikely to share the same off-target activities. If both probes produce the same phenotypic result, confidence increases that the effect is due to on-target modulation [5]. Negative controls help distinguish specific on-target effects from non-specific or off-target effects inherent to the chemical scaffold [5].

How do I determine the correct concentration for my compound in a cellular screen?

For a chemogenomic screen in NALM6 cells, the platform typically performs a dose-response curve to determine the IC50 (the concentration that inhibits 50% of cell growth). An intermediate dose close to the IC50 is often used to capture both genes that confer resistance (enriched) and sensitivity (depleted) in a single screen [1]. It is crucial to re-validate target engagement when moving a probe to a new cellular system, as protein expression and accessibility can differ [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Library | Enables genome-wide screening of gene knockouts. | Designed for human cancer cells; contains sgRNAs targeting genes. |

| Chemical Probe | Selectively modulates a protein's function to study its role. | Must be selective, potent, and have a demonstrated negative control compound [5]. |

| NALM6 Cell Line | A standard cellular model for suspension cell screens. | Derived from human pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia; features high knockout efficiency and easy lentiviral infection [1]. |

| High-Throughput Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from amplified sgRNA pools. | Kits like ExpressPlex enable rapid, multiplexed preparation with minimal hands-on time and auto-normalization for consistent coverage [3]. |

| Nextflow Pipeline | Orchestrates the bioinformatics analysis of NGS data. | A workflow management system that ensures portability and reproducibility across computing environments [4]. |

From Compound to Genetic Signature

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics research, enabling comprehensive analysis of genomic variations that influence drug response. However, the journey from raw sequencing data to clinically actionable insights is fraught with technical challenges. Two primary bottlenecks dominate this landscape: persistent sequencing errors that risk confounding downstream analysis and increasing computational limitations as data volumes grow exponentially. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance to help researchers navigate these critical roadblocks in their pharmacogenomics workflows.

Section 1: Understanding and Correcting Sequencing Errors

Sequencing errors originate from multiple sources throughout the NGS workflow. During sample preparation, artifacts may be introduced via polymerase incorporation errors during amplification. The sequencing process itself introduces approximately 0.1-1% of errors, which are more common in reads with poor-quality bases where sequencers misinterpret signals. Additional errors accumulate during library preparation stages. These errors manifest as base substitutions, insertions, or deletions, with error profiles varying significantly across sequencing platforms. Illumina platforms typically produce approximately one error per thousand nucleotides, primarily substitutions, while third-generation technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio historically had higher error rates (>5%) distributed across substitution, insertion, and deletion types [6] [7].

How can I computationally correct sequencing errors in heterogeneous datasets?

Computational error correction employs specialized algorithms to identify and fix sequencing errors. The performance of these methods varies substantially across different dataset types, with no single method performing best on all data. For highly heterogeneous datasets like T-cell receptor repertoires or viral quasispecies, the following correction methods have been benchmarked:

Table: Computational Error-Correction Methods for NGS Data [6]

| Method | Best Application Context | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Coral | Whole genome sequencing data | Balanced precision and sensitivity |

| Bless | Various dataset types | k-mer based approach |

| Fiona | Diverse applications | Good performance across datasets |

| Pollux | Experimental datasets | Effective error correction |

| BFC | Multiple data types | Efficient computational correction |

| Lighter | Large-scale data | Fast processing capability |

| Musket | General purpose | High accuracy correction |

| Racer | Recommended replacement for HiTEC | Improved error correction |

| RECKONER | Sequencing reads | Sensitivity-focused approach |

| SGA | Assembly applications | Effective for genomic assembly |

Evaluation metrics for these tools include:

- Gain: Quantifies overall performance (1.0 = perfect correction)

- Precision: Proportion of proper corrections among all corrections performed

- Sensitivity: Proportion of fixed errors among all existing errors [6]

What experimental protocols can eliminate sequencing errors?

Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI)-based high-fidelity sequencing protocols (safe-SeqS) can eliminate sequencing errors from raw reads. This method:

- Attaches UMIs to DNA fragments prior to amplification

- Groups reads into clusters based on UMI tags after sequencing

- Generates consensus sequences within each UMI cluster

- Requires at least 80% of reads to support a nucleotide call, otherwise disregards the cluster [6]

This approach is particularly valuable for creating gold standard datasets to benchmark computational error-correction methods, especially for highly heterogeneous populations like immune repertoires and viral quasispecies [6].

Section 2: Computational and Analytical Limitations

Why has computation become a major bottleneck in NGS analysis?

Computational analysis has transformed from a negligible cost to a significant bottleneck due to several converging trends. While sequencing costs have plummeted to approximately $100-600 per genome, computational advances have not kept pace with Moore's Law. Analytical pipelines are now overwhelmed by massive data volumes from single-cell sequencing and large-scale re-analysis of public datasets. This shift means researchers must now explicitly consider trade-offs between accuracy, computational resources, storage, and infrastructure complexity that were previously insignificant when sequencing costs dominated budgets [7].

What strategies address computational bottlenecks in genomic analysis?

Several innovative approaches help mitigate computational limitations:

Data Sketching: Uses lossy approximations that sacrifice perfect fidelity to capture essential data features, providing orders-of-magnitude speedups [7]

Hardware Acceleration: Leverages FPGAs and GPUs for significant speed improvements, though requires additional hardware investment [7]

Domain-Specific Languages: Enables programmers to handle complex genomic operations more efficiently [7]

Cloud Computing: Provides flexible resource allocation, allowing researchers to make hardware choices for each analysis rather than during technology refresh cycles [7]

Table: Computational Trade-offs in NGS Analysis [7]

| Approach | Advantages | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sketching | Orders of magnitude faster | Loss of perfect accuracy |

| Hardware Accelerators (FPGAs/GPUs) | Significant speed improvements | Expensive hardware requirements |

| Domain-Specific Languages | Reproducible handling of complex operations | Steep learning curve |

| Cloud Computing | Flexible resource allocation | Ongoing costs, data transfer issues |

How can I extract accurate pharmacogenotypes from clinical NGS data?

The Aldy computational method can extract pharmacogenotypes from whole genome sequencing (WGS) and whole exome sequencing (WES) data with high accuracy. Validation studies demonstrate:

- Aldy v3.3 achieved 99.5% concordance with panel-based genotyping for 14 major pharmacogenes using WGS

- Aldy v4.4 reached 99.7% concordance for WGS and similar accuracy for WES data

- The method identified additional clinically actionable star alleles not covered by targeted genotyping in CYP2B6, CYP2C19, DPYD, SLCO1B1, and NUDT15 [8]

Key challenges in clinical NGS data include low read depth, incomplete coverage of pharmacogenetically relevant loci, inability to phase variants, and difficulty resolving large-scale structural variations, particularly for CYP2D6 copy number variation [8].

Section 3: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

How do I troubleshoot low library yield in NGS preparations?

Low library yield stems from several root causes with specific corrective actions:

Table: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield [2]

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor input quality/contaminants | Enzyme inhibition from salts, phenol, or EDTA | Re-purify input sample; ensure 260/230 >1.8, 260/280 ~1.8 |

| Inaccurate quantification | Suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) instead of UV; calibrate pipettes |

| Fragmentation inefficiency | Reduced adapter ligation efficiency | Optimize fragmentation parameters; verify size distribution |

| Suboptimal adapter ligation | Poor adapter incorporation | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase/buffer |

| Overly aggressive purification | Desired fragment loss | Optimize bead:sample ratios; avoid bead over-drying |

What are the most common sequencing preparation failures and their solutions?

Frequent sequencing preparation issues fall into distinct categories:

Sample Input/Quality Issues

- Failure signals: Low starting yield, smear in electropherogram, low library complexity

- Root causes: Degraded DNA/RNA, sample contaminants, inaccurate quantification, shearing bias

- Solutions: Re-purify input samples, use fluorometric quantification, optimize fragmentation [2]

Fragmentation/Ligation Failures

- Failure signals: Unexpected fragment size, inefficient ligation, adapter-dimer peaks

- Root causes: Over/under-shearing, improper buffer conditions, suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio

- Solutions: Optimize fragmentation parameters, titrate adapter ratios, maintain optimal temperature [2]

Amplification/PCR Problems

- Failure signals: Overamplification artifacts, bias, high duplicate rate

- Root causes: Too many PCR cycles, inefficient polymerase, primer exhaustion

- Solutions: Reduce cycle number, use high-efficiency polymerase, optimize primer design [2]

Section 4: The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

Table: Essential Materials for NGS Experiments [6] [2] [8]

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Error correction via molecular barcoding | Attached prior to amplification for high-fidelity sequencing |

| High-fidelity polymerases | Accurate DNA amplification | Reduces incorporation errors during PCR |

| Fluorometric quantification reagents | Accurate nucleic acid measurement | Superior to absorbance methods for template quantification |

| Size selection beads | Fragment purification | Critical for removing adapter dimers; optimize bead:sample ratio |

| Commercial NGS libraries | Standardized sequencing preparation | CLIA-certified options for clinical applications |

| TaqMan genotyping assays | Orthogonal variant confirmation | Validates computationally extracted pharmacogenotypes |

| KAPA Hyper prep kit | Library construction | Used in clinical WGS workflows |

Section 5: Workflow Diagrams

NGS Error Correction and Analysis Workflow

Computational Bottlenecks and Solutions Framework

Section 6: Frequently Asked Questions

How do I choose between computational error correction and UMI-based methods?

The choice depends on your research objectives and resources. Computational correction offers a practical solution for routine analyses where perfect accuracy isn't critical, with tools like Fiona and Musket providing a good balance of precision and sensitivity. UMI-based methods are preferable when creating gold standard datasets or working with highly heterogeneous populations like viral quasispecies or immune repertoires, where error-free reads are essential for downstream interpretation. For clinical applications requiring the highest accuracy, combining both approaches provides optimal results [6].

What are the key considerations for implementing NGS in clinical pharmacogenomics?

Clinical NGS implementation requires addressing several critical factors:

- Validation: Computational genotype extraction methods must demonstrate >99% accuracy compared to reference standards, as shown with Aldy for major pharmacogenes [8]

- Coverage: Ensure mean read depth >30x for all pharmacogenetically relevant variant regions [8]

- Variant Phasing: Utilize tools that can resolve haplotype phases for accurate star allele calling [8]

- Structural Variants: Implement methods capable of detecting copy number variations, particularly for challenging genes like CYP2D6 [8]

- Actionability: Focus on pharmacogenes with established clinical guidelines (CPIC) and FDA-recognized associations [9] [8]

How can I optimize computational workflows for large-scale NGS data?

Optimization strategies include:

- Performance Profiling: Identify bottlenecks in your specific analysis pipeline (alignment, variant calling, etc.)

- Tool Selection: Choose algorithms with appropriate speed-accuracy tradeoffs for your research question

- Resource Allocation: Leverage cloud computing for burst capacity and specialized hardware (FPGAs/GPUs) for repetitive tasks

- Data Management: Implement efficient storage solutions for intermediate files and final results

- Pipeline Parallelization: Design workflows to process samples independently when possible to maximize throughput [7]

Impact of Pharmacogenetic Complexity on Analysis Pipelines

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Configuration & Validation

Issue: Inconsistent variant calling across different sample batches.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate pipeline validation or batch effects.

- Solution: Adhere to joint AMP/CAP recommendations for NGS bioinformatics pipeline validation [10]. Implement a rigorous quality control (QC) protocol that includes:

- Using validated reference materials with known variants for each batch.

- Regularly re-running control samples to monitor pipeline drift.

- Establishing and monitoring key performance metrics like sensitivity, specificity, and precision for variant detection [10].

Issue: High number of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in pharmacogenes.

- Potential Cause: Standard computational prediction tools trained on pathogenic datasets perform poorly on pharmacogenes, which are under less evolutionary constraint [11].

- Solution: Utilize pharmacogenomics-specific functional prediction pipelines. This involves:

- High-Throughput Experimental Data: Incorporate data from large-scale functional assays that characterize the consequences of rare variants in genes like CYP450 family members [11].

- Specialized Computational Tools: Use tools designed for pharmacogenomic (PGx) variants, as traditional tools like SIFT and PolyPhen-2 may misclassify functionally important but non-pathogenic variants [11].

- Leverage TDM Data: Correlate genetic findings with large, retrospective therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) datasets to validate the clinical impact of VUS [11].

Data Analysis & Interpretation

Issue: Difficulty analyzing complex gene loci (e.g., CYP2D6, HLA).

- Potential Cause: Short-read NGS platforms struggle with highly homologous regions, segmental duplications, and copy number variations (CNVs) [11].

- Solution: Implement a multi-technology approach.

- Targeted Long-Read Sequencing: Use technologies like Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing or Nanopore sequencing for targeted haplotyping and accurate CNV profiling of complex loci [11].

- Specialized Bioinformatics Pipelines: Employ variant calling pipelines specifically designed and validated for these complex regions to accurately resolve star (*) alleles [11].

Issue: Algorithm fails to predict a known drug-response phenotype.

- Potential Cause: The analysis may be missing key rare or structural variants, or the model may not account for population-specific alleles [12] [11].

- Solution:

- Ensure your variant calling pipeline includes comprehensive coverage of rare variants and CNVs, as recommended by the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) [13].

- For dose prediction algorithms (e.g., for warfarin), verify that the model includes alleles relevant to your patient's ancestry. For example, the CYP2C9*8 allele is important for patients of African ancestry but is often missing from standard algorithms [12].

Clinical Implementation & Reporting

Issue: Challenges integrating PGx results into the Electronic Health Record (EHR) for clinical decision support.

- Potential Cause: Lack of standardized data formats for genomic information and insufficiently designed clinical decision support (CDS) tools [13].

- Solution:

- Advocate for the adoption of data and application standards for genomic information (e.g., HL7 FHIR) to improve data portability and EHR integration [13].

- Design CDS tools that are seamlessly integrated into clinician workflows and provide clear, actionable recommendations, not just raw genetic data [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between validating a germline pipeline versus a somatic pipeline for pharmacogenomics?

A: The primary focus in PGx is on accurate germline variant calling to predict an individual's inherent drug metabolism capacity. The validation must ensure high sensitivity and specificity for a predefined set of clinically relevant PGx genes and their known variant types, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), and complex variants like hybrid CYP2D6/CYP2D7 alleles [10] [11]. Somatic pipelines, used in oncology, are optimized for detecting low-frequency tumor variants and often require different validation metrics.

Q2: Our pipeline works well for European ancestry populations but has poor performance in other groups. How can we fix this?

A: This is a common issue due to the underrepresentation of diverse populations in genomic research [13] [12]. Solutions include:

- Utilize Pan-Ethnic Allele Frequency Databases: Use reference databases like the All of Us Research Program, which has enrolled a diverse cohort, to ensure your pipeline and interpretation tools are informed by global genetic diversity [13].

- Incorporate Population-Specific Alleles: Actively curate and include alleles with higher frequency in underrepresented populations (e.g., CYP2C9*8 in African ancestry) into your genotyping panels and interpretation algorithms [12].

- Validate Pipeline Performance: Specifically validate your bioinformatics pipeline's performance across diverse ancestral backgrounds to identify and correct for biases [13].

Q3: What is the most effective way to handle the thousands of rare variants discovered by NGS in pharmacogenes?

A: Adopt a two-pronged interpretation strategy [11]:

- For characterized variants: Rely on curated knowledgebases like PharmGKB and CPIC guidelines for which there is existing clinical or functional evidence.

- For uncharacterized rare variants: Combine high-throughput experimental characterization data (when available) with computational predictions from tools specifically tuned for pharmacogenes. Correlating findings with large-scale TDM data can provide retrospective clinical validation for these variants.

Q4: How can Artificial Intelligence (AI) help overcome PGx analysis bottlenecks?

A: AI and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing PGx by [14]:

- Improving Variant Calling: Tools like DeepVariant use deep learning to identify genetic variants with higher accuracy than traditional methods.

- Predicting Drug Response: ML models can integrate multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic) to predict whether a patient will be a responder or non-responder to a specific drug.

- Interpreting Complex Patterns: AI can help interpret the combined effect of multiple variants across different genes to predict complex drug response phenotypes, moving beyond single gene-drug pairs.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

High-Throughput Functional Characterization of PGx Variants

Purpose: To experimentally determine the functional impact of numerous rare variants in a pharmacogene (e.g., CYP2C9) discovered via NGS. Methodology:

- Variant Selection: Select missense and loss-of-function variants from NGS data with a focus on rare variants (MAF < 1%) of uncertain significance.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Create plasmid constructs for each variant allele.

- Heterologous Expression: Express the variant proteins in a standardized cell system (e.g., mammalian cell lines).

- Enzyme Kinetics Assay: Measure the enzymatic activity (e.g., V~max~, K~m~) for each variant against a model substrate and compare to the wild-type enzyme.

- Data Integration: Classify variants based on functional impact (e.g., normal, decreased, or no function) and integrate this data into a curated database for clinical interpretation [11].

NGS Bioinformatics Pipeline Validation

Purpose: To establish the performance characteristics of a clinical NGS pipeline for PGx testing as per professional guidelines [10]. Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Use a validation set of samples with known variants, confirmed by an orthogonal method (e.g., Sanger sequencing). This set should include a range of variant types (SNVs, indels, CNVs) across all relevant PGx genes.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Process the validation samples through the entire NGS workflow, from library preparation to bioinformatics analysis.

- Performance Calculation: Calculate the following metrics for each variant type and each gene:

- Accuracy: (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Samples

- Precision (Positive Predictive Value): True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives)

- Analytical Sensitivity (Recall): True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)

- Specificity: True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives)

- Establish Reportable Range: Define the minimum coverage and quality thresholds for confidently calling a variant [10].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Pharmacogenomic Analysis Bottlenecks and Strategic Solutions

| Bottleneck Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Research | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Interpretation | High volume of rare variants & VUS [11] | Delays in determining clinical relevance; inconclusive reports. | Integrate high-throughput functional data and PGx-specific computational tools [11]. |

| Pipeline Accuracy | Inconsistent performance across complex loci (CYP2D6, HLA) [11] | Mis-assignment of star alleles; incorrect phenotype prediction. | Supplement with long-read sequencing for targeted haplotyping [11]. |

| Population Equity | Underrepresentation in reference data [13] [12] | Algorithmic bias; reduced clinical utility for non-European populations. | Utilize diverse biobanks (e.g., All of Us); include population-specific alleles in panels [13] [12]. |

| Clinical Integration | Lack of standardized EHR integration [13] | PGx data remains siloed; fails to inform point-of-care decisions. | Adopt data standards (HL7 FHIR); develop workflow-integrated CDS tools [13]. |

| Evidence Generation | Difficulty proving clinical utility [13] [12] | Sparse insurance coverage; slow adoption by clinicians. | Leverage real-world data (RWD) and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for retrospective studies [11]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PGx Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in PGx Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Materials | Provides a truth set for validating NGS pipeline accuracy and reproducibility [10]. | Must include variants in key PGx genes (e.g., CYP2C19, DPYD, TPMT) and complex structural variants. |

| Targeted Long-Read Sequencing Kits | Resolves haplotypes and accurately calls variants in complex genomic regions (e.g., CYP2D6) [11]. | Higher error rate than short-reads requires specialized analysis; ideal for targeted enrichment. |

| Pan-Ethnic Genotyping Panels | Ensures inclusive detection of clinically relevant variants across diverse ancestral backgrounds [13]. | Panels must be curated with population-specific alleles (e.g., CYP2C9*8) to avoid healthcare disparities. |

| Functional Assay Kits | Provides experimental characterization of variant function for VUS resolution [11]. | Assays should be high-throughput and measure relevant pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., enzyme activity). |

| Curated Knowledgebase Access | Provides essential, evidence-based clinical interpretations for drug-gene pairs [13]. | Reliance on frequently updated resources like PharmGKB and CPIC guidelines is critical. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

PGx NGS Analysis Pipeline

Pharmacogenomic Variant Interpretation

Drug Metabolism Pathway Impact

The Challenge of Rare and Structural Variants in Drug Response

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my PGx genotyping pipeline failing on complex pharmacogenes like CYP2D6? Complex pharmacogenes often contain high sequence homology with non-functional pseudogenes (e.g., CYP2D6 and CYP2D7) and tandem repeats, which cause misalignment of short sequencing reads [15] [16]. This leads to inaccurate variant calling and haplotype phasing. To resolve this, consider supplementing your data with long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) for the problematic loci. Long-read technologies can span repetitive regions and resolve full haplotypes, significantly improving accuracy [15].

How can I accurately determine star allele haplotypes from NGS data? Accurate haplotyping requires statistical phasing of observed small variants followed by matching to known star allele definitions [16]. Use specialized PGx genotyping tools like PyPGx, which implements a pipeline to phase single nucleotide variants and insertion-deletion variants, and then cross-references them against a haplotype translation table for the target gene. The tool combines this with a machine learning-based approach to detect copy number variations and other structural variants that define critical star alleles [16].

My variant calling workflow is running out of memory. How can I fix this?

Genes with a high density of variants or very long genes can cause memory errors during aggregation steps [17]. This can be mitigated by increasing the memory allocation for specific tasks in your workflow definition file (e.g., a WDL script). For example, you may increase the memory for first_round_merge from 20GB to 32GB, and for second_round_merge from 10GB to 48GB [17].

What is the most cost-effective sequencing strategy for comprehensive PGx profiling? The choice involves a trade-off between cost, completeness, and accuracy [7].

- Targeted Panels: Cost-effective for focused analysis of a predefined set of ADME genes but miss novel variants and complex structural variations outside the targeted regions [15].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Provides a comprehensive view of coding and non-coding regions, capturing known and novel variants. With costs now as low as $100 per genome, WGS is an increasingly viable option for population-level PGx studies [16] [7].

- Hybrid Approach: Use short-read WGS for broad variant discovery and supplement with long-read sequencing for complex loci to resolve haplotypes accurately [15].

How do I interpret a hemizygous genotype call on an autosome? A haploid (hemizygous-like) call for a variant on an autosome (e.g., genotype '1' instead of '0/1') typically indicates that the variant is located within a heterozygous deletion on the other chromosome [17]. This is not an error but a correct representation of the genotype. You should inspect the gVCF file for evidence of a deletion call spanning the variant's position on the other allele [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Structural Variants in Complex Pharmacogenes

Problem: Inaccurate detection of star alleles due to structural variants (SVs) like gene deletions, duplications, and hybrids in genes such as CYP2A6, CYP2D6, and UGT2B17.

Investigation & Solution:

- Confirm Data Quality: Check alignment (BAM) files around the gene of interest. Look for low mapping quality scores and dropped coverage, which signal alignment ambiguity in complex regions [15] [16].

- Employ SV-aware Tools: Standard variant callers often miss SVs. Use PGx-specialized tools like PyPGx, which uses a support vector machine (SVM) to detect SVs from read depth and copy number variation data [16].

- Validate with Long-Read Sequencing: If possible, use long-read sequencing (10–40 kb reads) to span repetitive regions and resolve the haplotype structure unambiguously. Studies show this method can fully resolve haplotypes for the majority of guideline pharmacogenes [15].

Guide 2: Managing Computational Bottlenecks in Population-Scale PGx Analysis

Problem: Processing whole-genome sequencing data for thousands of samples is computationally prohibitive, causing long delays.

Investigation & Solution:

- Profile Your Pipeline: Identify which steps (e.g., read alignment, variant calling, joint genotyping) consume the most time and memory [7] [18].

- Leverage Hardware Acceleration: For standard secondary analysis (alignment and variant calling), consider using hardware-accelerated solutions like the Illumina Dragen system, which can process a 30x genome in under an hour, though at a higher compute cost [7].

- Utilize Data Sketching: For specific analyses like comparative k-mer studies, use efficient "sketching" algorithms (e.g., Mash) that sacrifice perfect fidelity for massive speed-ups, enabling rapid initial surveys [7].

- Optimize Memory Allocation: As detailed in the FAQ, manually adjust memory for specific tasks in your workflow scripts to prevent crashes on large genes [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Genotyping Technologies for PGx

| Technology | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations in PGx SV Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR/qPCR | Amplification of specific DNA sequences | Cost-effective, fast, high-throughput [15] | Limited to known, pre-defined variants; cannot detect novel SVs [15] |

| Microarrays | Hybridization to predefined oligonucleotide probes | Simultaneously genotypes hundreds to thousands of known SNVs and CNVs [15] | Cannot detect novel variants or balanced SVs (e.g., inversions); poor resolution for small CNVs [15] [19] |

| Short-Read NGS (Illumina) | Parallel sequencing of millions of short DNA fragments | Detects known and novel SNVs/indels; high accuracy [15] [7] | Struggles with phasing, large SVs, and highly homologous regions due to short read length [15] [20] |

| Long-Read NGS (PacBio, Nanopore) | Sequencing of single, long DNA molecules | Resolves complex loci, fully phases haplotypes, detects all SV types [15] | Higher raw error rates and cost per sample, though improving [7] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in PGx Analysis |

|---|---|

| PyPGx | A Python package for predicting PGx genotypes (star alleles) and phenotypes from NGS data. It integrates SNV, indel, and SV detection using a machine-learning model [16]. |

| PharmVar Database | The central repository for curated star allele nomenclature, providing haplotype definitions essential for accurate genotype-to-phenotype translation [16]. |

| PharmGKB | The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase, a resource that collects, curates, and disseminates knowledge about the impact of genetic variation on drug response [16]. |

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) | A widely used software package for aligning sequencing reads against a reference genome, a critical first step in most NGS analysis pipelines [15]. |

| 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) Data | A public repository of high-coverage whole-genome sequencing data from diverse populations, serving as a critical resource for studying global PGx variation [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Population-Level Star Allele and Phenotype Calling with PyPGx

Objective: To identify star alleles and predict metabolizer phenotypes from high-coverage whole-genome sequencing data across a diverse cohort.

Methodology:

- Data Input: Obtain high-coverage WGS data (BAM/FASTQ) aligned to GRCh37 or GRCh38 [16].

- Variant Phasing: Use the PyPGx pipeline, which employs the Beagle program to statistically phase observed small variants (SNVs and indels) into two haplotypes per sample [16].

- Star Allele Matching: Cross-reference the phased haplotypes against the target gene's haplotype translation table. The pipeline selects the final star allele based on priority: allele function, number of core variants, protein impact, and reference allele status [16].

- SV Detection: Compute per-base copy number from read depth via intra-sample normalization. Detect SVs (deletions, duplications) from this data using a pre-trained support vector machine (SVM) classifier [16].

- Diplotype Assignment: Combine the candidate star alleles and SV results to make the final diplotype call (e.g.,

CYP2D6*1/*4) and translate it to a predicted phenotype (e.g., Poor Metabolizer) using database guidelines [16].

Protocol 2: Validating SVs with Long-Read Sequencing

Objective: To confirm the structure and phase of complex SVs identified in pharmacogenes by short-read WGS.

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Select samples where short-read analysis suggests a complex or ambiguous SV (e.g., a hybrid gene or duplication with uncertain breakpoints) [15].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare high molecular weight DNA libraries. Sequence using a long-read platform (PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore) to generate reads of 10 kb or longer [15].

- Variant Calling & Phasing: Align long reads and call variants. The length of the reads will allow for direct observation of the co-occurrence of variants on a single DNA molecule, providing unambiguous haplotype phasing and precise SV breakpoint identification [15] [19].

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Analysis Workflow for PGx Variants

Technology Selection Logic

Understanding the 40 Exabyte Challenge

In the era of large-scale chemogenomics studies, the management of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data has become a critical bottleneck. By 2025, an estimated 40 exabytes of storage capacity will be required to handle the global accumulation of human genomic data [21] [22]. This unprecedented volume presents significant challenges for storage, transfer, and computational analysis, particularly in drug discovery pipelines where rapid iteration is essential.

Quantifying the NGS Data Challenge

| Data Metric | Scale & Impact |

|---|---|

| Global Genomic Data Volume (2025) | 40 Exabytes (EB) [21] [22] |

| NGS Data Storage Market (2024) | USD 1.6 Billion [23] |

| Projected Market Size (2034) | USD 8.5 Billion [23] |

| Market Growth Rate (CAGR) | 18.6% [23] |

| Primary Data Type | Short-read sequencing data dominates the market [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary factors contributing to the massive data volumes in NGS-based chemogenomics?

The 40 exabyte challenge stems from multiple, concurrent advances in sequencing technology and its application:

- Throughput of Modern Sequencers: Platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X generate terabytes of data per run, enabling large-scale projects but creating immediate storage pressures [24].

- Shift to Multiomic Analyses: Modern chemogenomics does not rely on genomics alone. Integrating epigenomic (e.g., methylation), transcriptomic (RNA expression), and proteomic data from the same sample multiplies the data volume and complexity for a more comprehensive view of drug response [25] [26] [24].

- Population-Scale Studies: Initiatives like the UK Biobank and the Alliance for Genomic Discovery are sequencing hundreds of thousands of genomes to discover therapeutic targets, generating petabytes of raw data [25].

- Advanced Applications: Techniques like single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, which profile gene expression at the individual cell level within a tissue context, are exceptionally data-intensive but critical for understanding tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance [25] [24].

FAQ 2: Our lab is experiencing severe bottlenecks in transferring and sharing large NGS datasets. What are the best solutions?

Data transfer is a common physical bottleneck. The following strategies and tools can help mitigate this issue:

- Implement Data Compression: Use specialized tools like

CRAMfor raw sequencing data (which offers better compression than BAM) andBGZFfor compressed, indexed genomic files to minimize the physical size of datasets for transfer. - Leverage Cloud-Based Platforms: Utilize secure, cloud-based bioinformatics platforms like DNAnexus, Terra, or Illumina BaseSpace [26] [24]. These platforms allow collaborators to access and analyze data in a centralized location, eliminating the need for repeated large-scale transfers. They comply with security frameworks like HIPAA and GDPR, ensuring data privacy [24].

- Aspera or Similar High-Speed Transfer Protocols: For moving data to and from the cloud, use high-speed transfer protocols that bypass the inherent latency of standard TCP/IP, significantly accelerating upload/download times.

FAQ 3: How can we ensure the quality and integrity of our NGS data when dealing with such large datasets?

Maintaining data quality at scale requires a robust Quality Management System (QMS). The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI) provides essential tools for this purpose [27].

- Use NGS QI Resources: Implement the NGS QMS Assessment Tool and the Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) SOP to establish a framework for continuous quality monitoring [27].

- Establish Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): Track metrics like read depth (coverage), base call quality scores (Q-score), alignment rates, and duplication rates for every run. A sudden shift in these KPIs can indicate issues with library preparation, the sequencer, or the analysis pipeline [27].

- Validate and Lock Down Workflows: Once an NGS method is validated for a specific chemogenomics assay, it is crucial to "lock down" the entire workflow—from library prep to bioinformatics analysis—to ensure reproducibility. Any change (e.g., new reagent lot, software update) requires careful revalidation [27].

FAQ 4: What computational strategies are most effective for analyzing large-scale chemogenomics data?

Traditional computing methods often fail at this scale. The key is to leverage scalable, automated, and intelligent solutions.

- Adopt AI/ML for Variant Calling: Replace traditional heuristic methods with AI-powered tools like DeepVariant, which uses deep learning to identify genetic mutations with superior accuracy, reducing false positives and manual review time [26] [24].

- Utilize Cloud and High-Performance Computing (HPC): Cloud platforms (AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure) offer scalable computational power on demand. They are essential for running resource-intensive tasks like genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and multi-omics integration without local infrastructure bottlenecks [24].

- Automate Bioinformatics Pipelines: Use workflow management systems (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) to create reproducible, scalable, and portable analysis pipelines. This automates the data flow from raw fastq files to final variant calls, minimizing manual intervention and human error [28].

FAQ 5: How can our research group cost-effectively store and manage 40 exabytes of data?

The economic burden of data storage is significant. A strategic approach is required.

- Evaluate Hybrid Storage Models: A combination of on-premises storage for active projects and low-cost cloud storage (e.g., Amazon S3 Glacier, Google Cloud Coldline) for archiving infrequently accessed data can be highly cost-effective [29].

- Implement Data Lifecycle Policies: Not all data needs to be kept forever. Establish clear policies that define which data must be retained (e.g., final variant calls, analysis-ready BAMs) and which can be deleted (e.g., raw intermediate files) after a defined period and project completion.

- Leverage Vendor Solutions: Explore vendors specializing in NGS data storage, such as Qumulo for scalable file storage or DNAnexus and Illumina for integrated analysis platforms that manage storage and computation together [29] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item / Solution | Function in NGS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X Series | High-throughput sequencing platform for generating whole-genome data at a massive scale, foundational for large chemogenomics screens [24]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Provides long-read sequencing capabilities, crucial for resolving complex genomic regions, detecting structural variations, and direct RNA/epigenetic modification detection [27] [24]. |

| DNAnexus/Terra Platform | Cloud-based bioinformatics platforms that provide secure, scalable environments for storing, sharing, and analyzing NGS data without advanced computational expertise [26] [22]. |

| DeepVariant | An AI-powered tool that uses a deep neural network to call genetic variants from NGS data, dramatically improving accuracy over traditional methods [26] [24]. |

| NGS QI Validation Plan SOP | A standardized template from the NGS Quality Initiative for planning and documenting assay validation, ensuring data quality and regulatory compliance (e.g., CLIA) [27]. |

| CRISPR Design Tools (e.g., Synthego) | AI-powered platforms for designing and validating CRISPR guides in functional genomics screens to identify drug targets [26]. |

| Nextflow | Workflow management software that enables the creation of portable, reproducible, and scalable bioinformatics pipelines, automating data analysis from raw data to results [28]. |

Advanced Analytical Frameworks: AI and Machine Learning Solutions for Chemogenomics Data

Technical Foundation: Understanding AI-Based Variant Calling

Variant calling is a fundamental step in genomic analysis that involves the identification of genetic variations, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (InDels), and structural variants, from high-throughput sequencing data [30]. Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), has revolutionized this field by introducing tools that offer higher accuracy, efficiency, and scalability compared to traditional statistical methods [30].

Performance Comparison of AI-Powered Variant Callers

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prominent AI-based variant calling tools.

| Tool Name | Primary AI Methodology | Key Strengths | Common Sequencing Data Applications | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant [30] [31] | Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | High accuracy; automatically produces filtered variants; supports multiple technologies [30]. | Short-read, PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore [30] | High computational cost [30] |

| DeepTrio [30] | Deep CNNs | Enhances accuracy for family trios; improved performance in challenging genomic regions [30]. | Short-read, various technologies [30] | Designed for trio analysis, not single samples [30] |

| DNAscope [30] | Machine Learning (ML) | High computational speed and accuracy; reduced memory overhead [30]. | Short-read, PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore [30] | Does not leverage deep learning architectures [30] |

| Clair/Clair3 [30] [31] | Deep CNNs | High speed and accuracy, especially at lower coverages; optimized for long-read data [30] [31]. | Short-read and long-read data [30] | Predecessor (Clairvoyante) was inaccurate with multi-allelic variants [30] |

| Medaka [30] | Neural Networks | Designed for accurate variant calling from Oxford Nanopore long-read data [30]. | Oxford Nanopore [30] | Specialized for one technology (ONT) [30] |

| NeuSomatic [31] | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Specialized for detecting somatic mutations in heterogeneous cancer samples [31]. | Tumor and normal paired samples [31] | Focused on somatic, not germline, variants [31] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the key differences between traditional and AI-powered variant callers, and why should I switch?

Answer: Traditional variant callers rely on statistical and probabilistic models that use hand-crafted rules to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors [31]. In contrast, AI-powered tools use deep learning models trained on large genomic datasets to automatically learn complex patterns and subtle features associated with real variants [30]. This data-driven approach typically results in superior accuracy, higher reproducibility, and a significant reduction in false positives, especially in complex genomic regions where conventional methods often struggle [30] [31]. The switch is justified when your research demands higher precision, such as in clinical diagnostics or the identification of low-frequency somatic mutations in cancer [31] [32].

FAQ 2: My AI variant caller is extremely slow and resource-intensive. How can I improve its performance?

Answer: High computational demand is a common bottleneck, particularly with deep learning models. To mitigate this:

- Check Hardware Compatibility: Ensure you are using a GPU-equipped system. While some tools like DeepVariant can run on a CPU, a GPU drastically accelerates computation [30]. Note that some efficient tools, like DNAscope, are optimized for multi-threaded CPU processing and do not require a GPU [30].

- Optimize Input Data: For tools like DeepVariant that use pileup images, verify that the input region is not excessively large. Consider processing the genome in smaller, parallelized chunks if supported by the workflow.

- Evaluate Alternatives: If runtime is critical, benchmark alternative tools. For instance, DNAscope and Clair3 are noted for their computational efficiency and faster runtimes compared to other deep learning methods [30].

FAQ 3: I am working with long-read sequencing data (Oxford Nanopore/PacBio). Which AI caller is most suitable?

Answer: Long-read technologies have specific error profiles that require specialized tools. The most recommended AI-based callers for long-read data are:

- Clair3: Specifically designed for long-read data, it integrates pileup and full-alignment information to achieve high speed and accuracy, even at lower coverages [30] [31].

- Medaka: Developed by Oxford Nanopore, it employs neural networks to perform haploid-aware variant calling, accounting for the inherent error rates of ONT sequencing [30].

- DeepVariant: Its ongoing development includes support for both PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore data, maintaining high accuracy across platforms [30].

- PEPPER-Margin-DeepVariant: A comprehensive pipeline that combines AI-powered components for long-read data, addressing challenges in structural variant detection [31].

FAQ 4: How do I handle variant calling for family-based or cancer somatic mutation studies?

Answer: The study design dictates the choice of the variant caller.

- For Family Trios (e.g., child and parents): Use DeepTrio. It is an extension of DeepVariant that jointly analyzes sequencing data from all three family members. This familial context allows it to better distinguish sequencing errors from true de novo mutations, significantly enhancing accuracy [30].

- For Somatic Mutations in Cancer: Use a tool specifically designed for somatic calling, such as NeuSomatic. These tools use CNN architectures trained to detect low variant allele frequencies in a background of tumor heterogeneity, which is a common challenge in cancer genomics [31].

FAQ 5: What is the role of Transformer models in variant calling and NGS analysis?

Answer: While many established variant callers are based on CNNs, Transformer models represent the next wave of AI innovation in genomics. Drawing parallels between biological sequences and natural language, Transformers are now being applied to critical tasks in the NGS pipeline [33] [34]. Their powerful self-attention mechanism allows them to understand long-range contextual relationships within DNA or protein sequences. In genomics, Transformers are currently making a significant impact in:

- Neoantigen Detection: Predicting how peptides (potential neoantigens) bind to the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), a crucial step for developing personalized cancer vaccines [33].

- Basecalling: Tools like Bonito and Dorado from Oxford Nanopore are beginning to use transformer architectures to improve the accuracy of converting raw electrical signals into nucleotide sequences [26] [31].

- Nucleotide Sequence Analysis: More broadly, Transformer-based language models are being adapted for a wide range of tasks in bioinformatics, including the analysis of DNA and RNA sequences [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Germline Variant Calling with DeepVariant

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying germline SNPs and small InDels from whole-genome sequencing data using the DeepVariant pipeline [30].

1. Input Preparation:

- Input File: A coordinate-sorted BAM file containing reads aligned to a reference genome. The BAM file should be generated following standard preprocessing steps (quality control, adapter trimming, alignment, and duplicate marking) [32].

- Reference Genome: The same reference genome (in FASTA format) used for read alignment.

2. Variant Calling Execution:

- Run the DeepVariant command, specifying the input BAM, reference genome, and output directory.

- DeepVariant will process the aligned reads, creating "pileup images" of the data. These images represent the sequencing data at each potential variant site.

- The pre-trained deep convolutional neural network (CNN) then analyzes these images to distinguish true genetic variants from sequencing artifacts [30].

3. Output and Filtering:

- Output File: The primary output is a VCF (Variant Call Format) file containing the identified variants and their genotypes.

- A key strength of DeepVariant is that it outputs high-quality, filtered calls directly, often eliminating the need for additional hard-filtering steps that are common with traditional callers [30].

Protocol 2: Somatic Variant Calling with an AI-Based Workflow

This protocol describes a workflow for identifying somatic mutations from paired tumor-normal samples, which is essential in cancer genomics [31] [32].

1. Sample and Input Preparation:

- Sample Pairs: Obtain matched BAM files from a tumor tissue sample and a normal (e.g., blood) sample from the same patient.

- Data Preprocessing: Ensure both BAM files have undergone identical and rigorous preprocessing, including local realignment and base quality score recalibration (BQSR), as per best practices (e.g., GATK Best Practices) [32].

2. Somatic Variant Calling:

- Use a specialized somatic caller like NeuSomatic.

- Provide the tool with the paired tumor and normal BAM files. The model, often a CNN, is trained to identify the subtle signals of somatic mutations against the complex background of tumor heterogeneity and sequencing noise [31].

3. Output and Annotation:

- The output is a VCF file containing the somatic variants.

- Prioritization: Annotate the VCF file using databases (e.g., dbSNP, ClinVar) to filter common polymorphisms and identify variants with potential clinical or functional impact [32]. This is critical for narrowing down candidate driver mutations in chemogenomics research.

Workflow Visualization

AI Variant Calling in Chemogenomics

NGS Data to Variant Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and tools required for implementing AI-powered variant calling in a research pipeline.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Tools/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality NGS Library | The starting material for sequencing. Library preparation quality directly impacts variant calling accuracy [35]. | Kits for DNA/RNA extraction, fragmentation, and adapter ligation. |

| Sequencing Platform | Generates the raw sequencing data. Platform choice (e.g., Illumina, ONT, PacBio) influences the selection of the optimal AI caller [30] [36]. | Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, PacBio systems. |

| Computational Infrastructure | Essential for running computationally intensive AI models. A GPU significantly accelerates deep learning inference [30]. | High-performance servers with GPUs. |

| Reference Genome | A standardized genomic sequence used as a baseline for aligning reads and calling variants [32]. | FASTA files (e.g., GRCh38/hg38). |

| Aligned Read File (BAM) | The standard input file for variant callers. Contains sequencing reads mapped to the reference genome [32]. | BAM or CRAM file format. |

| AI Variant Calling Software | The core tool that uses a trained model to identify genetic variants from the aligned reads. | DeepVariant, Clair3, DNAscope, NeuSomatic [30] [31]. |

| Variant Call Format (VCF) File | The standard output file containing the list of identified genetic variants, their genotypes, and quality metrics [30] [32]. | VCF file format. |

| Annotation Databases | Used to add biological and clinical context to raw variant calls, helping prioritize variants for further study [32]. | dbSNP, ClinVar, COSMIC, gnomAD. |

Overcoming Rare Variant Interpretation with Computational Prediction Tools

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Diagnostic Yield in Rare Disease Analysis

- Problem: Exome or genome sequencing of a rare disease patient has been completed, but no clinically relevant variants were identified in known disease-associated genes.

- Diagnosis: The analysis likely failed to correctly prioritize a rare, pathogenic missense variant. This is a common bottleneck, as affected individuals often carry multiple variations in disease-associated genes, with only a fraction being truly pathogenic [37].

- Solution:

- Re-analyze with updated databases: The sheer re-analysis of exomic data after 1–3 years, updating major disease variant and disease-gene association databases, is reported to increase diagnosed cases by over 10% [37].

- Reanalyze in collaboration with the clinician: A further improvement in yields could be obtained by reanalyzing the data with the clinical context provided by the diagnosing physician [37].

- Employ a high-performing predictor: Use a top-tier computational variant effect predictor like AlphaMissense to re-score all rare missense variants. Recent unbiased benchmarking in population cohorts has shown it outperforms many other tools in correlating rare variants with human traits [38].

Issue 2: High Computational Cost and Slow Analysis Times

- Problem: Secondary analysis of whole-genome sequencing data (alignment, variant calling) is taking too long, becoming a significant bottleneck and cost center.

- Diagnosis: Traditional analytical pipelines can be overwhelmed by the massive amount of data produced by modern sequencers. With sequencing costs falling, computation is now a considerable part of the total cost [7].

- Solution:

- Evaluate trade-offs: Consider the trade-offs between accuracy, compute time, and infrastructure complexity [7].

- Utilize hardware acceleration: Leverage hardware-accelerated solutions (e.g., Illumina Dragen on cloud platforms like AWS) which can reduce analysis time from tens of hours to under an hour, though at a higher compute cost [7].

- Consider targeted analysis: For specific clinical questions, a more targeted analysis (e.g., looking for specific marker genes) using faster, alignment-free methods might be sufficient, trading some accuracy for speed [7].

Issue 3: Adapter Contamination in Sequencing Data

- Problem: Sequencing run returns data with abnormal adapter dimer signals, impacting data quality and variant calling accuracy.

- Diagnosis: Inefficient ligation or an imbalance in the adapter-to-insert molar ratio during library preparation, leading to adapter-dimers being sequenced [2].

- Solution:

- Bioinformatic trimming: Reanalyze the run with the correct barcode settings selected (e.g., "RNABarcodeNone") to automatically trim the adapter sequence from the reads [39].

- Wet-lab optimization: For future runs, titrate the adapter-to-insert ratio to find the optimal balance. Excess adapters promote adapter dimers, while too few reduce ligation yield [2]. Ensure thorough purification and size selection to remove small fragments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: After initial analysis fails, what is the most effective first step to identify a causative variant? A: The most effective first step is the periodic re-analysis of sequencing data. Re-analyzing exome data after updating disease and variant databases can increase diagnostic yields by over 10%. Collaboration with the diagnosing clinician to incorporate updated clinical findings further enhances this process [37].

Q: Which computational variant effect predictor should I use for rare missense variants? A: Based on recent unbiased benchmarking using population cohorts like the UK Biobank and All of Us, AlphaMissense was the top-performing predictor, outperforming 23 other tools in inferring human traits from rare missense variants [38]. It was either the best or tied for the best predictor in 132 out of 140 gene-trait combinations evaluated [38].

Q: My NGS library yield is unexpectedly low. What are the primary causes? A: The primary causes and their fixes are summarized in the table below [2]:

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (phenol, salts). | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8). |

| Quantification Errors | Overestimating usable material. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV absorbance (NanoDrop). |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces ligation efficiency. | Optimize fragmentation time/energy; verify fragment distribution. |

| Suboptimal Ligation | Poor ligase performance or wrong adapter:insert ratio. | Titrate adapter ratios; ensure fresh ligase/buffer. |

Q: What amount of sequencing data is recommended for Hi-C genome scaffolding? A: For genome scaffolding using Hi-C data (e.g., with the Proximo platform), the recommended amount of sequencing data (2x75 bp or longer) is [40]:

- Genome size <400 Mb: 100 million read-pairs

- Genome size 400 Mb – 1.5 Gb: 150 million read-pairs

- Genome size 1.5 Gb – 3 Gb: 250 million read-pairs For larger genomes or assemblies with low contiguity, scale accordingly.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking Variant Effect Predictors using a Population Cohort

This protocol outlines a method for the unbiased evaluation of computational variant effect predictors, avoiding the circularity and bias that can limit traditional benchmarks that use clinically classified variants [38].

Cohort and Gene-Trait Set Curation:

- Assemble a set of established gene-trait combinations from rare-variant burden association studies (e.g., from published literature or biobank studies).

- Obtain whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing data and corresponding phenotype data for a large population cohort (e.g., UK Biobank, All of Us) that was not used in the training of the predictors being evaluated.

Variant Extraction and Filtering:

- Extract all missense variants for the trait-associated genes from the cohort data.

- Filter variants to include only those with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.1% to focus on rare variants with potentially larger phenotypic effects.

Computational Prediction:

- Collect predicted functional scores for all extracted missense variants from the computational predictors being benchmarked (e.g., AlphaMissense, CADD, ESM1-v, etc.).

Performance Measurement:

- For each gene-trait combination, evaluate the correlation between the summed predicted variant scores for each participant and their trait value.

- For binary traits (e.g., medication use), calculate the Area Under the Balanced Precision-Recall Curve (AUBPRC).

- For quantitative traits (e.g., LDL cholesterol levels), calculate the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC).

- Use bootstrap resampling (e.g., 10,000 iterations) to estimate the uncertainty (mean and 95% CI) for each performance measure.

Statistical Comparison:

- Perform pairwise statistical comparisons between predictors across all gene-trait combinations using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, adjusting for false discovery rate (FDR) with Storey's q-value. A predictor is considered superior if the FDR < 10% [38].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Rare Variant Analysis Workflow

Predictor Benchmarking Logic

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and resources for rare variant interpretation in chemogenomics research.

| Tool/Resource Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaMissense | A computational variant effect predictor that outperforms others in inferring human traits from rare missense variants in unbiased benchmarks [38]. | Prioritizing pathogenic missense variants in patient cohorts. |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | A standardized vocabulary of phenotypic abnormalities, structured as a directed acyclic graph, containing over 13,000 terms for describing patient phenotypes [37]. | Standardizing phenotype data for genotype-phenotype association studies. |

| Paraphase | A computational tool for haplotype-resolved variant calling in homologous genes (e.g., SMN1/SMN2) from both WGS and targeted sequencing data [41]. | Analyzing genes with high sequence homology or pseudogenes. |

| pbsv | A suite of tools for calling and analyzing structural variants (SVs) in diploid genomes from HiFi long-read sequencing data [41]. | Comprehensive detection of SVs, which are often involved in rare diseases. |

| Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) | A comprehensive, authoritative knowledgebase of human genes and genetic phenotypes, freely available and updated daily [37]. | Curating background knowledge on gene-disease relationships. |

| Prokrustean graph | A data structure that allows rapid iteration through all k-mer sizes from a sequencing dataset, drastically reducing computation time for k-mer-based analyses [42]. | Optimizing k-mer-based applications like metagenomic profiling or genome assembly. |

Integrating Multi-Omics Data for Comprehensive Drug Response Profiling

Integrating multi-omics data is imperative for studying complex biological processes holistically. This approach combines data from various molecular levels—such as genome, epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome—to highlight interrelationships between biomolecules and their functions. In chemogenomics research, this integration helps bridge the gap from genotype to phenotype, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how tumors respond to therapeutic interventions. The advent of high-throughput techniques has made multi-omics data increasingly available, leading to the development of sophisticated tools and methods for data integration that significantly enhance drug response prediction accuracy and provide deeper insights into the biological mechanisms underlying treatment efficacy [43].

Analysis of multi-omics data alongside clinical information has taken a front seat in deriving useful insights into cellular functions, particularly in oncology. For instance, integrative approaches have demonstrated superior performance over single-omics analyses in identifying driver genes, understanding molecular perturbations in cancers, and discovering novel biomarkers. These advancements are crucial for addressing the challenges of tumor heterogeneity, which often reduces the efficacy of anticancer pharmacological therapy and results in clinical variability in patient responses [43] [44]. Multi-omics integration provides an additional perspective on biological systems, enabling researchers to develop more accurate predictive models for drug sensitivity and resistance.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why should I integrate multi-omics data instead of relying on single-omics analysis for drug response prediction? A: Integrated multi-omics approaches provide a more holistic view of biological systems by revealing interactions between different molecular layers. Studies have consistently shown that combining omics datasets yields better understanding and clearer pictures of the system under study. For example, integrating proteomics data with genomic and transcriptomic data has helped prioritize driver genes in colon and rectal cancers, while combining metabolomics and transcriptomics has revealed molecular perturbations underlying prostate cancer. Multi-omics integration can significantly improve the prognostic and predictive accuracy of disease phenotypes, ultimately aiding in better treatment strategies [43].

Q: What are the primary technical challenges in preparing sequencing libraries for multi-omics studies? A: The most common challenges fall into four main categories: (1) Sample input and quality issues including degraded nucleic acids or contaminants that inhibit enzymes; (2) Fragmentation and ligation failures leading to unexpected fragment sizes or adapter-dimer formation; (3) Amplification problems such as overcycling artifacts or polymerase inhibition; and (4) Purification and cleanup errors causing incomplete removal of small fragments or significant sample loss. These issues can result in poor library complexity, biased representation, or complete experimental failure [2].

Q: Which computational approaches show promise for integrating heterogeneous multi-omics data? A: Gene-centric multi-channel (GCMC) architectures that transform multi-omics profiles into three-dimensional tensors with an additional dimension for omics types have demonstrated excellent performance. These approaches use convolutional encoders to capture multi-omics profiles for each gene, yielding gene-centric features for predicting drug responses. Additionally, multi-layer network theory and artificial intelligence methods are increasingly being applied to dissect complex multi-omics datasets, though these approaches require large, systematic datasets to be most effective [44] [45].

Q: What public data repositories are available for accessing multi-omics data? A: Several rich resources exist, including:

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): One of the largest collections of multi-omics data for over 33 cancer types.

- International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC): Coordinates large-scale genome studies from 76 cancer projects.

- Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE): Contains gene expression, copy number, and sequencing data from 947 human cancer cell lines.

- Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC): Hosts proteomics data corresponding to TCGA cohorts.

- Omics Discovery Index: A consolidated resource providing datasets from 11 repositories in a uniform framework [43].

Troubleshooting Guide: NGS Library Preparation

Table: Common NGS Library Preparation Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input/Quality | Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low library complexity | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) instead of UV only; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8) [2] |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks | Over- or under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and optimal temperature [2] |

| Amplification/PCR | Overamplification artifacts; bias; high duplicate rate | Too many PCR cycles; inefficient polymerase; primer exhaustion | Reduce cycle number; use high-fidelity polymerases; optimize primer design and concentration [2] |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incomplete removal of small fragments; sample loss; carryover of salts | Wrong bead ratio; bead over-drying; inefficient washing; pipetting error | Calibrate bead:sample ratios; avoid over-drying beads; implement pipette calibration [2] |

Case Study: Troubleshooting Sporadic Failures in a Core Facility A core laboratory performing manual NGS preparations encountered inconsistent failures across different operators. The issues included samples with no measurable library or strong adapter/primer peaks. Root cause analysis identified deviations in protocol execution, particularly in mixing methods, timing differences between operators, and degradation of ethanol wash solutions. The implementation of standardized operating procedures with highlighted critical steps, master mixes to reduce pipetting errors, operator checklists, and temporary "waste plates" to catch accidental discards significantly reduced failure frequency and improved consistency [2].

Diagnostic Strategy Flow: When encountering NGS preparation problems, follow this systematic approach:

- Examine electropherograms for sharp 70-90 bp peaks (indicating adapter dimers) or abnormal size distributions.

- Cross-validate quantification using both fluorometric (Qubit) and qPCR methods rather than relying solely on absorbance measurements.

- Trace backwards through each preparation step—if ligation failed, examine fragmentation and input quality.

- Run appropriate controls to detect contamination or reagent issues.

- Review protocol details including reagent logs, kit lots, enzyme expiry dates, and equipment calibration records [2].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies