Breaking the Barrier: Outer Membrane Permeability as the Key to Overcoming Gram-Negative Antibiotic Resistance

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane as a formidable permeability barrier and a major contributor to antibiotic resistance.

Breaking the Barrier: Outer Membrane Permeability as the Key to Overcoming Gram-Negative Antibiotic Resistance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane as a formidable permeability barrier and a major contributor to antibiotic resistance. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of the asymmetric outer membrane, detailing the roles of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and porins. It further examines methodological approaches for enhancing compound penetration, troubleshooting common resistance phenotypes, and validating strategies through comparative studies across pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with recent advances in permeabilization and efflux inhibition, this review aims to inform the rational design of next-generation antimicrobials effective against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens.

The Gram-Negative Fortress: Deconstructing the Outer Membrane Barrier

The lipid bilayer constitutes the fundamental barrier of the cell, but its performance is not merely a function of its bulk properties. Compositional asymmetry—the non-random distribution of lipid species between the two leaflets of the bilayer—is a highly conserved and energetically costly feature of the plasma membrane in eukaryotes and the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria. This review posits that asymmetry is a critical structural adaptation that optimizes the membrane for the conflicting demands of forming a robust permeability barrier while enabling efficient cellular signaling and, in bacteria, conferring intrinsic antibiotic resistance. We synthesize recent advances demonstrating that the exoplasmic or outer leaflet is specialized for low permeability, rich in saturated lipids and cholesterol (or lipopolysaccharides in bacteria), forming a tightly packed, ordered phase. In contrast, the cytoplasmic or inner leaflet is enriched in unsaturated lipids, creating a more fluid, disordered environment that facilitates the diffusion and interaction of signaling molecules. This guide provides a quantitative dissection of this model, detailing the experimental and computational methodologies driving this field forward, and frames the implications for overcoming membrane-based antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative pathogens.

Biological membranes are not symmetric. The plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells and the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria exhibit profound lipid asymmetry, a nonequilibrium state where the lipid composition of the outer (exoplasmic) and inner (cytoplasmic) leaflets are distinct [1] [2]. Cells invest substantial free energy, in the form of tens to hundreds of ATP hydrolysis events per translocated lipid, to establish and maintain this asymmetry via active transporters like flippases and floppases [1]. Such a significant energetic investment implies a critical functional benefit.

The core hypothesis of this article is that lipid asymmetry represents an evolutionary solution to a fundamental design challenge: the membrane must be both an impermeable barrier and a fluid matrix for dynamic processes. This guide will explore the structural basis of how asymmetry resolves this conflict, with a specific focus on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria as a primary determinant of antibiotic resistance. The asymmetric outer membrane, with its lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-rich outer leaflet, provides a "formidable barrier" that restricts the passive influx of antibiotics, making these pathogens particularly challenging to treat [3] [4] [5].

Structural and Compositional Foundations of the Asymmetric Barrier

The two leaflets of the cellular plasma membrane have distinct lipid compositions tailored for their specific functions. This asymmetry is a hallmark of plasma membranes across eukaryotes and many prokaryotes [1].

The Exoplasmic (Outer) Leaflet: This leaflet is predominantly enriched in lipids with saturated fatty acyl chains, such as sphingomyelin and phosphocholine lipids. These lipids pack tightly due to their straight hydrocarbon chains, forming a dense, liquid-ordered phase. In Gram-negative bacteria, this role is taken to an extreme with the exclusive presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane. The complex, bulky structure of LPS, anchored by lipid A, creates a nearly impenetrable hydrophobic barrier [3] [4] [5].

The Cytoplasmic (Inner) Leaflet: This leaflet is primarily composed of lipids with (poly-)unsaturated fatty acids, such as the aminophospholipids phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). The kinks in the unsaturated hydrocarbon chains prevent tight packing, resulting in a liquid-disordered phase that is more fluid and dynamic [1] [6].

Table 1: Characteristic Lipid Compositions of Asymmetric Membrane Leaflets

| Leaflet | Representative Lipid Components | Physical State | Primary Functional Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exoplasmic/Outer | Sphingomyelin, Phosphocholine, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS in bacteria) | Liquid-ordered phase | Impermeable Barrier Function |

| Cytoplasmic/Inner | Phosphatidylserine (PS), Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), Polyunsaturated lipids | Liquid-disordered phase | Signaling & Molecular Dynamics |

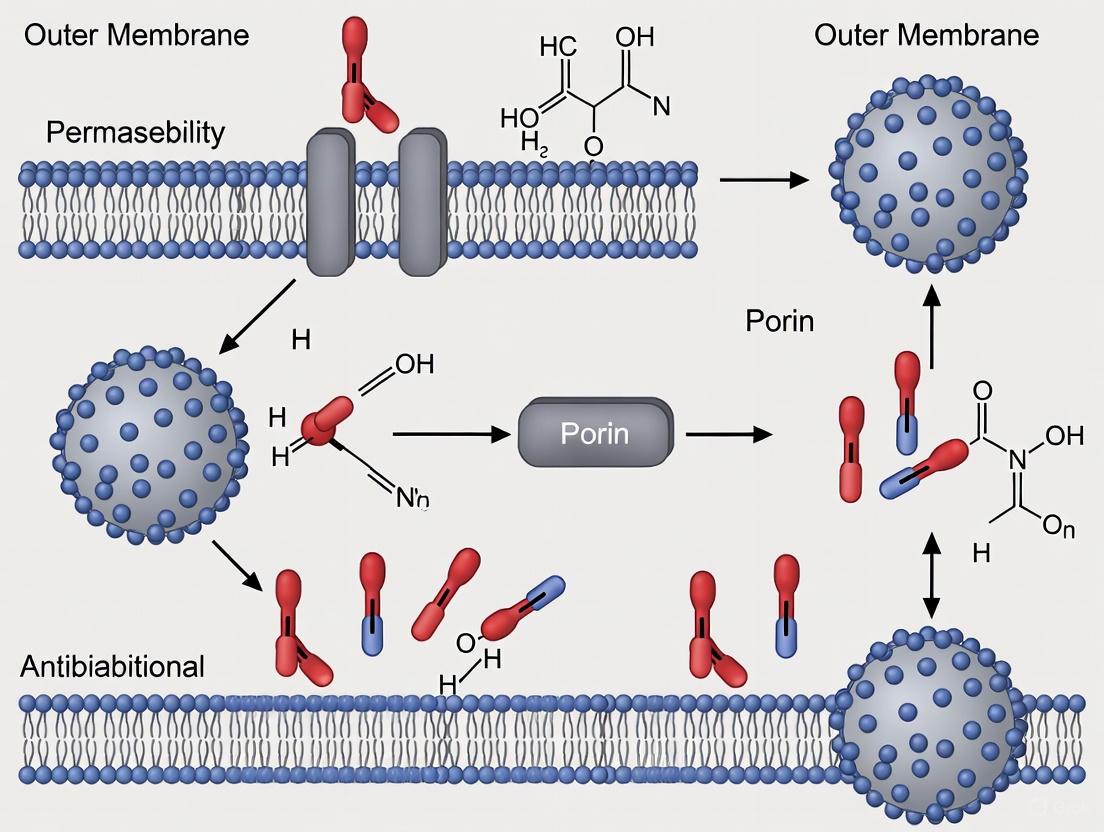

This compositional divide is not merely a static separation; it creates a composite material with emergent properties. The two leaflets can be viewed as acting as two resistances in series, where the overall permeability is dominated by the least permeable leaflet [1]. This conceptual framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The two leaflets of the asymmetric plasma membrane form a composite material, with the outer leaflet providing a tight barrier and the inner leaflet enabling fluidity for signaling.

Quantitative Basis of Permeability

The barrier function of a membrane is quantitatively described by its permeability coefficient (P), governed by the Meyer-Overton rule: P = K·D/d, where K is the partition coefficient, D is the diffusion constant within the membrane, and d is the membrane thickness [1]. For an asymmetric bilayer, the total permeability (P~total~) is the reciprocal sum of the permeabilities of the individual leaflets, acting as resistances in series: 1/P~total~ = 1/P~o.l.~ + 1/P~i.l.~ (where o.l. and i.l. denote outer and inner leaflets) [1].

When the permeability difference between leaflets is large, the overall membrane permeability is effectively determined by the less permeable leaflet: P~total~ ≈ P~o.l.~. This is precisely the case in the cellular plasma membrane, where the tightly packed outer leaflet dominates barrier function.

Experimental data robustly supports this model. A comparative study using liposomes with lipid compositions mimicking the exoplasmic versus cytoplasmic leaflets found that the cytoplasmic-mimic membranes were 18 to 90 times more permeable to various polar substances [1]. This dramatic difference is attributed to key physical properties:

- Area Per Lipid: This is a dominant factor controlling permeability, particularly for water. The saturated lipids and high cholesterol content of the exoplasmic leaflet minimize the area per lipid, creating a densely packed structure that is difficult for solutes to penetrate [1].

- Membrane Phase: The exoplasmic leaflet's ability to form a liquid-ordered phase is critical. Water permeability in a fluid-phase DPPC bilayer can be 2000 times lower than in a gel-phase bilayer, and a 7-fold difference persists between liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phases [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Permeability Differences Between Leaflet Compositions

| Parameter | Exoplasmic/Outer Leaflet Mimic | Cytoplasmic/Inner Leaflet Mimic | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Permeability | 1X (Baseline) | 18X to 90X higher | Liposome studies with polar substances [1] |

| Phase State | Liquid-ordered (L~o~) | Liquid-disordered (L~d~) | Fluorescent packing reporters [1] |

| Key Physical Trait | Small area per lipid, high packing density | Large area per lipid, low packing density | Molecular dynamics & biophysical studies [1] [6] |

| Cholesterol Content | High | ~1/2 to 1/3 of L~o~ phase | Domain formation studies [1] |

In Gram-negative bacteria, the barrier is even more extreme. The outer membrane's permeability to hydrophilic antibiotics is largely governed by porin channels, as the LPS layer itself is a formidable barrier to hydrophobic molecules [3] [5]. Modifications to LPS structure, such as the addition of 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to lipid A, can further reduce its negative charge and decrease the binding and uptake of cationic antimicrobial peptides and antibiotics like polymyxin, constituting a major resistance mechanism [5].

Methodologies for Investigating Asymmetric Membranes

Studying asymmetric bilayers is methodologically challenging, as traditional model membranes are often symmetric. Below are key experimental and computational approaches driving progress in the field.

Computational Modeling with Molecular Dynamics (MD)

MD simulations provide atomic-resolution insights into membrane properties and are an indispensable tool for studying asymmetry [6]. A critical challenge is the initial construction of the asymmetric bilayer model, as the chosen protocol heavily influences the results, particularly regarding differential stress—a non-zero leaflet tension arising from mismatched leaflet properties [6].

Table 3: Protocols for Constructing Asymmetric Bilayers in MD Simulations

| Construction Protocol | Core Principle | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| Equal Numbers (EqN) | Ensure an equal number of lipid molecules in each leaflet. | Initial studies, systems with minimal compositional disparity. |

| Surface Area (SA) | Match the leaflet surface areas to those from cognate symmetric bilayers. | Investigating properties sensitive to lateral pressure and packing. |

| Zero Differential Stress (0-DS) | Adjust lipid numbers to achieve zero leaflet tension (τ = 0). | Simulating a relaxed, natural membrane state; studying mechanical properties. |

| P21 Boundary Conditions | Use specialized periodic boundaries that allow lipid flip-flop between leaflets. | Studying systems where slow lipid exchange is relevant. |

The choice of construction method is paramount, as it determines the presence and magnitude of differential stress, which in turn can affect membrane properties like thickness, area per lipid, and the lateral diffusion of lipids and proteins [6]. The general workflow for this computational analysis is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Workflow for molecular dynamics simulation of asymmetric lipid bilayers, highlighting the critical step of selecting a bilayer construction protocol.

Experimental Assessment of Barrier Permeability

In both biological and model membrane systems, quantifying permeability is essential. In clinical and preclinical settings, Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DCE-MRI) is a gold standard for assessing blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, a key example of a specialized barrier function [7].

Advanced DCE-MRI methods involve acquiring T1-weighted images before and after intravenous injection of a Gadolinium-based contrast agent (Gd-DTPA). The "post-pre comparison" method involves a pixel-wise statistical comparison (e.g., t-test with false discovery rate correction) between pre- and post-contrast scans. Pixels with statistically significant intensity changes within a defined enhancement range (calibrated using reference tissues like muscle and eyeball) are identified as regions with a leaky BBB [7]. This method provides a semi-quantitative assessment of barrier integrity with a less demanding imaging protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methods

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric Liposomes/Vesicles | Model membranes with controlled, asymmetric lipid distribution in each leaflet. | Essential for in vitro study of true membrane asymmetry, enabling permeability and diffusion assays [2]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, CHARMM, NAMD) | Simulates atomic-level dynamics of asymmetric bilayers over time. | Allows investigation of lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions, differential stress, and permeability pathways [6]. |

| Fluorescent Lipid Analogs & Lipid-Anchored Proteins | Probes for measuring lateral diffusion and dynamics in the membrane leaflets. | Used in FRAP and other live-cell imaging techniques to demonstrate higher fluidity in the cytoplasmic leaflet [1]. |

| General Diffusion Porins (e.g., OmpF, OmpC) | Bacterial outer membrane proteins forming water-filled channels for hydrophilic solute influx. | Critical for studying antibiotic uptake in Gram-negative bacteria; mutations here are a common resistance mechanism [3] [4]. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Primary component of the outer leaflet of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. | Key reagent for modeling the formidable permeability barrier of bacteria and studying resistance mechanisms like LPS modification [3] [5]. |

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents (e.g., Gd-DTPA) | Tracer for in vivo permeability assessment using imaging techniques like DCE-MRI. | Used to quantitatively evaluate the integrity of biological barriers like the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) [7]. |

The asymmetric bilayer is not a passive, static wall but a sophisticated, actively maintained composite material. Its structural design elegantly solves the fundamental problem of integrating a resilient, impermeable barrier with a dynamic, fluid signaling platform. In the context of antibiotic resistance, the Gram-negative outer membrane represents a perfected example of this principle, where extreme asymmetry and unique molecular components like LPS create a formidable defense.

Future research will continue to deepen our quantitative understanding of interleaflet coupling—how the physical state of one leaflet influences the other—and its role in cellular physiology and drug resistance. Advancing experimental methods to create more complex and tunable asymmetric model membranes, combined with increasingly powerful molecular dynamics simulations, will be crucial [2]. Furthermore, a detailed molecular understanding of the outer membrane permeability barrier opens the door to rational drug design strategies aimed at bypassing or disrupting this barrier, thereby resensitizing resistant pathogens to conventional antibiotics. The study of membrane asymmetry thus stands as a critical frontier at the intersection of cell biology, biophysics, and pharmaceutical science.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the defining molecular component of the outer membrane (OM) of most Gram-negative bacteria [8]. This complex glycolipid fulfills a critical dual function: it provides crucial structural integrity to the bacterial cell while simultaneously forming a formidable permeability barrier that protects against external threats, including many antimicrobial compounds [9] [8]. The effectiveness of this barrier, particularly its ability to exclude hydrophobic molecules, is a direct consequence of the unique chemical structure of LPS and its precise packing within the membrane [8] [10]. Understanding the relationship between LPS composition, membrane packing, and the resulting hydrophobic exclusion is fundamental to research aimed at overcoming innate antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative pathogens.

Structural Composition of LPS

An LPS molecule is architecturally divided into three distinct domains, each contributing specific properties to the overall function of the OM.

- Lipid A: This is the hydrophobic anchor of the LPS molecule, embedding it in the outer leaflet of the OM [11] [9]. Lipid A is a conserved glucosamine-based disaccharide that is phosphorylated and typically acylated with four to seven saturated fatty acids [9] [8] [10]. This domain is the endotoxic principle of LPS, primarily responsible for triggering a potent immune response in hosts through the TLR4/MD-2 receptor complex [11] [12].

- Core Oligosaccharide: Attached to lipid A, this domain consists of a short chain of sugars, including unusual ones like keto-deoxyoctulosonate (Kdo) and heptose [11] [9]. The core region can be subdivided into the inner and outer core. The inner core is often phosphorylated or substituted with charged molecules like phosphoethanolamine, contributing significantly to the overall negative charge of the OM [9] [10].

- O-Antigen (O-Ag): This is a highly variable polymer of repeating oligosaccharide units that extends distally from the core [11]. The presence and length of the O-antigen determine whether LPS is classified as "smooth" (with O-Ag) or "rough" (without O-Ag or with a truncated core) [11] [8]. The O-antigen is a key virulence factor, protecting bacteria from host immune responses such as complement-mediated lysis [8].

Table 1: Domains of the LPS Molecule and Their Key Characteristics

| Domain | Chemical Nature | Function | Variability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid A | Hydrophobic; glucosamine disaccharide with saturated acyl chains | Membrane anchor; endotoxic activity; permeability barrier | Conserved, but modifications (acylation, phosphorylation) occur and impact immune activation [9] [8]. |

| Core Oligosaccharide | Hydrophilic; contains Kdo, heptoses, hexoses | Structural integrity; contributes to membrane charge | Moderately variable; truncations create "rough" phenotypes [11] [8]. |

| O-Antigen | Highly hydrophilic; repeating sugar units | Protects from host defenses; serological specificity; adhesion | Highly variable; defines serotypes; length is polymorphic [11] [8]. |

LPS Packing and the Hydrophobic Barrier

The exceptional ability of the OM to exclude hydrophobic toxins and antibiotics is not due to a typical phospholipid bilayer but arises from the unique physicochemical properties of LPS and its tight packing in the outer leaflet [8] [10].

Molecular Basis of the Barrier

The barrier function is a direct result of two key characteristics of the LPS layer:

- Low Membrane Fluidity: The lipid A domain typically contains saturated fatty acids (often 6 in E. coli), which engage in extensive lateral interactions with neighboring LPS molecules. This results in a membrane with very low fluidity, creating a tightly packed, quasi-crystalline surface that is difficult for hydrophobic molecules to penetrate [8] [10].

- Dense Packing via Electrostatic Cross-linking: The LPS molecule carries multiple negative charges from phosphate and carboxyl groups on lipid A and the core oligosaccharide [8]. Strong electrostatic repulsion between these charges would normally prevent dense packing. This repulsion is neutralized by divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) that intercalate between adjacent LPS molecules, forming ionic bridges that dramatically enhance the packing density and stability of the OM [8] [10].

Impact of LPS Structure on Packing and Permeability

The precise structure of LPS directly influences the integrity of the permeability barrier.

- Core Oligosaccharide Length and Charge: Mutants with truncated LPS cores ("deep rough" mutants) exhibit a markedly more permeable OM [10]. A shorter core reduces the distance over which electrostatic repulsion acts, weakening the cross-bridging by divalent cations [13]. Furthermore, a reduction in core length and charge has been experimentally shown to increase bacterial sensitivity to hydrophobic solvents like butanol, as it compromises OM integrity [13].

- O-Antigen Length: Contrary to traditional understanding, recent research indicates that the presence of a long O-antigen polysaccharide can compromise the OM barrier to antibiotics. Transport and assembly of the bulky O-antigen at the cell surface appears to create defects that increase permeability, revealing a critical trade-off for bacteria between protection from host immunity and maintaining membrane integrity [14].

The following diagram illustrates how LPS structure and composition contribute to its barrier function.

Diagram 1: The relationship between LPS structure, its molecular properties, and the resulting hydrophobic barrier function. The O-antigen's role is complex, as its assembly can sometimes disrupt the dense packing.

Role in Hydrophobic Exclusion and Antibiotic Resistance

The OM asymmetric bilayer, with its dense LPS matrix, is exceptionally effective at hindering the penetration of hydrophobic antibiotics, which are often potent against Gram-positive bacteria [10]. This intrinsic resistance mechanism is termed hydrophobic exclusion.

- Mechanism of Exclusion: In a conventional phospholipid bilayer, hydrophobic molecules can dissolve and diffuse through the hydrophobic core. The tightly packed, hydrophilic surface of the LPS layer prevents this. The saturated acyl chains of lipid A create a rigid, ordered environment, while the extensive sugar network of the core and O-antigen presents a polar shell, making the initial entry of hydrophobic compounds thermodynamically unfavorable [8] [10].

- Evidence from Mutants: The critical role of a full-length, charged LPS core is demonstrated by "deep rough" mutants. These strains, which produce severely truncated LPS, show a dramatic increase in sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics (e.g., novobiocin, fusidic acid), macrolides, and dyes because their OM is compromised and contains patches of phospholipids that are more easily traversed [10].

- Bacterial Countermeasures to Host Defenses: Bacteria can further refine their LPS barrier to resist host-derived antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs). A common modification is the addition of cationic groups like 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (Ara4N) or phosphoethanolamine to the phosphate groups on lipid A [12] [10]. This reduces the net negative charge of the OM, decreasing the initial electrostatic attraction of cationic peptides and resulting in a more tightly packed, impermeable LPS layer that is resistant to compounds like polymyxin B [10].

Table 2: LPS Modifications and Their Impact on Antibiotic Permeability

| LPS Modification | Mechanism | Effect on OM Permeability | Resistance Conferred |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truncation of Core (Rough mutants) | Reduced charge and length; incorporation of phospholipids in outer leaflet [10]. | Greatly Increased | Increased sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics (e.g., novobiocin, fusidic acid, macrolides) [10]. |

| Ara4N/PEtn addition to Lipid A | Neutralizes negative charge on phosphates; enhances packing [12] [10]. | Decreased | Resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (e.g., Polymyxin B) [10]. |

| Alteration of O-Antigen Length | Long O-Ag may disrupt efficient packing and transport during assembly [14]. | Context-dependent increase | Shorter O-Ag can improve resistance to some antibiotics by improving barrier integrity [14]. |

| Reduction of Acyl Chains (e.g., to penta/tetra-acylated) | Alters geometry and packing density of Lipid A [8] [15]. | Can decrease immune recognition (evasion) but may alter fluidity [8]. | Evasion of TLR4-mediated immune response; variable effect on antibiotic resistance [8] [15]. |

Experimental Methods for Analysis

Research on LPS-driven hydrophobic exclusion relies on a suite of biochemical, genetic, and biophysical techniques.

Genetic Manipulation of LPS Structure

A core methodology involves the creation and analysis of bacterial mutants with defined alterations in their LPS.

- Objective: To directly test the contribution of specific LPS domains (O-antigen, core, lipid A) to OM barrier function.

- Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Use targeted gene knockouts (e.g., of waa genes involved in core biosynthesis or wba genes for O-antigen synthesis) to generate isogenic strains that produce truncated "rough" LPS or lack the O-antigen entirely [14] [10].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Antibiotic Sensitivity Assay: Perform minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays using a range of hydrophobic (e.g., novobiocin, erythromycin) and hydrophilic antibiotics. Rough mutants are expected to show significantly lower MICs for hydrophobic drugs [10].

- Chemical Sensitivity Assay: Test sensitivity to detergents (e.g., SDS) and bile salts, which also indicate OM integrity [10].

- LPS Characterization: Verify the LPS structure of mutants using SDS-PAGE and silver staining, which reveals the size and ladder-like pattern of smooth LPS versus the truncated bands of rough LPS [14].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

In silico modeling provides atomic-level insights into how LPS packing creates a barrier.

- Objective: To simulate the dynamic behavior of the asymmetric OM and quantify the energetics of solute penetration.

- Protocol:

- Membrane Model Construction: Build a computational model of the OM bilayer with LPS in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet. Models can include LPS with varying core lengths and charges [13].

- Simulation Setup: Place the model in a solvated box with ions (including Mg²⁺) and energy-minimize it. Run production simulations under controlled temperature and pressure.

- Analysis:

- *Lateral Packing and Fluidity: Calculate the lateral spacing between LPS molecules and the order parameter of the lipid A acyl chains. Tighter packing and higher order indicate a better barrier [13].

- Free Energy Calculations: Use umbrella sampling or similar methods to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF) for the translocation of a hydrophobic probe (e.g., butanol) across the OM. A high energy barrier indicates effective hydrophobic exclusion [13].

Permeabilization Assays

These assays use agents that specifically disrupt LPS packing to sensitize bacteria to antibiotics.

- Objective: To experimentally compromise the LPS layer and measure the resultant increase in antibiotic susceptibility.

- Protocol:

- Treatment with Chelators: Use EDTA to chelate the divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) that cross-bridge LPS molecules. This disrupts electrostatic stabilization, increases membrane permeability, and leads to the release of some LPS [10].

- Treatment with Cationic Peptides: Use polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), a derivative that lacks direct bactericidal activity but retains the ability to bind LPS and displace cross-bridging cations. This "permeabilizes" the OM without killing the cell [10].

- Checkerboard Assay: Combine sub-lethal concentrations of a permeabilizer (EDTA or PMBN) with a dilution series of an antibiotic. A synergistic reduction in the MIC of the antibiotic confirms the role of the OM as a permeability barrier [10].

The workflow for a comprehensive experimental analysis of LPS-mediated barrier function is summarized below.

Diagram 2: A combined experimental and computational workflow for analyzing the role of LPS in hydrophobic exclusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and tools used in LPS and OM permeability research.

Table 3: Key Reagents for LPS and Outer Membrane Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Polymyxin B Nonapeptide (PMBN) | OM permeabilizer; used to sensitize cells to hydrophobic antibiotics by disrupting LPS packing [10]. | Lacks the fatty acid tail of polymyxin B, thus non-bactericidal but retains LPS-binding activity [10]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Metal chelator; strips Mg²⁺/Ca²⁺ from LPS, disrupting ionic cross-links and increasing permeability [10]. | Commonly used in combination assays with antibiotics or detergents to test OM integrity. |

| Deep Rough Mutant Strains (e.g., E. coli K-12 derivatives, Salmonella Re mutants) | Models for studying the effect of severely truncated LPS cores on OM permeability and antibiotic resistance [14] [10]. | Produce lipooligosaccharide (LOS) lacking O-antigen and most of the core; highly sensitive to hydrophobic drugs [10]. |

| Anti-LPS Antibodies | Detection and serotyping of LPS; used in Western blot, ELISA, and immunofluorescence. | Specific to the O-antigen polysaccharide; allows for identification of bacterial serovars [8]. |

| TLR4/MD-2 Reporter Cell Lines (e.g., HEK-Blue hTLR4) | In vitro assessment of the endotoxic activity (immunostimulatory potential) of different LPS or lipid A structures [16] [15]. | Cells engineered to express the human TLR4/MD-2 complex and an inducible reporter gene for NF-κB activation. |

| LpxC Inhibitors (e.g., CHIR-090) | Potent, specific inhibitors of the LpxC enzyme; used to study the essentiality of LPS and as a starting point for novel antibiotic development [12]. | Targets the first committed step in lipid A biosynthesis; bactericidal for most Gram-negative bacteria [12]. |

The outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria constitutes a formidable permeability barrier, serving as a primary intrinsic resistance mechanism against antimicrobial agents [17] [18]. This asymmetric lipid bilayer, with its lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-enriched outer leaflet, provides exceptional protection while still allowing the selective passage of essential nutrients and ions [19]. The gatekeepers of this selective permeability are porins—integral membrane proteins that form water-filled channels facilitating the passive diffusion of hydrophilic molecules across the otherwise impermeable OM [19] [20]. Porins fundamentally function as molecular sieves, with pore diameters typically restricting passage to molecules under 600 Da, thereby balancing the membrane's protective role with the cellular need for nutrient uptake and waste expulsion [21].

The clinical significance of porins extends far beyond their basic physiological functions, as they represent critical determinants in bacterial pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance [19]. Modifications in porin expression, structure, or function can dramatically alter bacterial susceptibility to multiple antibiotic classes, positioning these proteins at the forefront of antimicrobial resistance research [20] [17]. The escalating global health threat posed by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens has intensified scientific interest in understanding porin biology, with the ultimate goal of developing novel therapeutic strategies that either exploit or counteract porin-mediated permeability mechanisms [18].

This technical guide comprehensively examines the structural and functional dichotomy between general diffusion porins and substrate-specific channels, detailing their respective roles in hydrophilic influx. By integrating recent advances in porin research with established foundational knowledge, we provide researchers with a sophisticated framework for understanding how porin pathways influence antibiotic permeability and resistance phenotypes, ultimately informing future drug development efforts against resistant Gram-negative infections.

Structural Architecture of Porin Channels

The β-Barrel Fold: A Conserved Structural Motif

Porins exhibit a characteristic transmembrane β-barrel architecture that distinguishes them from the α-helical bundles typical of inner membrane proteins [19] [21]. This structural motif consists of 14 to 22 antiparallel β-strands arranged in a cylindrical formation, with the first and last strands connected in an antiparallel fashion to complete the barrel closure [19]. The β-strands themselves are amphipathic, featuring an alternating pattern of hydrophobic residues facing the lipid bilayer and hydrophilic residues lining the central aqueous pore [22] [21]. This strategic arrangement creates a thermodynamically stable interface with the membrane environment while facilitating the passage of water-soluble compounds through the channel interior.

The dimensions of the porin β-barrel are remarkably conserved, with a height of approximately 25-30 Å corresponding to the thickness of the lipid bilayer, and an oval cross-section with diameters ranging from 30-35 Å laterally [19]. A key structural feature stabilizing porins within the membrane is the presence of aromatic girdles—clusters of tyrosine and phenylalanine residues—positioned at both the extracellular and periplasmic membrane interfaces [19]. These girdles serve as molecular anchors, with tyrosine predominating at the extracellular face and phenylalanine at the periplasmic side, creating distinct aromatic symmetry that enhances structural integrity [19].

The Constriction Zone: Molecular Basis for Selectivity

Perhaps the most functionally significant structural element within porins is the constriction zone, which dictates the size exclusion limit and charge selectivity of the channel [19] [17]. This narrow region is formed primarily by the inward folding of the third extracellular loop (L3), which bends back into the barrel at approximately half the height of the channel [19]. The constriction zone creates the narrowest part of the pore, effectively determining the molecular weight cutoff for permeating solutes—typically 600 Da or less for general porins in Enterobacterales [18].

The molecular discrimination at the constriction zone arises from both steric and electrostatic factors. The physical dimensions of this region create a molecular sieve that excludes molecules based on size, while the specific arrangement of charged amino acid residues along the constriction lining establishes an electrostatic field that preferentially attracts or repels solutes based on their charge [17]. For instance, in the general porin OmpF, the constriction zone features clustered acidic residues that create a net negative charge, weakly favoring cation permeation [21]. In contrast, specific porins like PhoE contain positively charged residues that enhance anion selectivity [22].

Table 1: Structural Classification of Major Porins in Gram-Negative Bacteria

| Porin Type | β-Strand Count | Oligomeric State | Exclusion Limit (Da) | Representative Examples | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Porins | 16 | Trimeric | ~600 | OmpF, OmpC (E. coli) | Moderate constriction zone, slight charge preferences |

| Specific Porins | 18 | Trimeric | Variable | LamB (maltodextrins), ScrY (sucrose) | Specialized binding sites, "greasy slide" for aromatics |

| Monomeric Porins | 14-16 | Monomeric | Variable | OmpA, OmpG | Smaller pores, some with signaling/structural roles |

| Eukaryotic Porins | 19 | Monomeric (can oligomerize) | ~1500-3000 | VDAC (mitochondria) | Voltage-gated, N-terminal α-helix regulation |

Oligomeric Assembly and Stability

Most bacterial porins form stable homotrimers in the native outer membrane, with each monomer constituting an independent translocation pathway [19] [21]. The trimeric assembly is stabilized by extensive interactions between monomer subunits, particularly through the pairing of the first β-strand of one monomer with the last β-strand of an adjacent monomer, creating a continuous β-sheet network across the trimer interface [21]. Additional stabilization is provided by surface loops, especially L2, which latch adjacent subunits together [21].

This quaternary structure confers significant thermodynamic stability, with wild-type trimeric porins exhibiting melting temperatures around 72°C—remarkably high for membrane proteins [21]. The exceptional stability of porins can be attributed to several factors: the extensive hydrogen-bonding network within the β-barrel that satisfies backbone polar groups; the precise interactions between hydrophobic barrel edges and membrane lipids; and in some porin variants, the presence of intramolecular disulfide bonds that provide additional rigidity [21]. This robustness allows porins to maintain structural integrity in the harsh extracellular environment and withstand physical and chemical stresses encountered during infection.

Functional Classification of Porin Pathways

General Diffusion Porins: Molecular Sieves of the Outer Membrane

General diffusion porins function as relatively non-selective molecular sieves that facilitate the passive diffusion of small, hydrophilic molecules according to concentration gradients [19] [20]. These porins, exemplified by OmpF and OmpC in Escherichia coli, form water-filled channels that allow the passage of various nutrients, ions, waste products, and unfortunately, many antibiotics [20] [21]. The permeability through these channels is governed primarily by physicochemical properties of the solute—including molecular size, hydrophilicity, and charge—rather than specific molecular recognition events [17].

The size exclusion limit for general porins typically falls below 600 Da, effectively preventing the passage of larger molecules while permitting rapid diffusion of smaller compounds [18]. Quantitative measurements using planar bilayer electrophysiology have demonstrated that single porin channels can achieve impressive transport rates, typically ranging from 10³ to 10⁶ molecules per second depending on solute characteristics [21]. For example, approximately 600 molecules of cephalosporin antibiotics can pass through a single OmpF monomer per second under physiological conditions [21]. This high throughput capacity ensures adequate nutrient supply while simultaneously creating a vulnerability to antibiotic penetration that bacteria must carefully regulate.

Substrate-Specific Porins: Facilitated Diffusion with Molecular Recognition

In contrast to general porins, substrate-specific channels employ sophisticated molecular recognition mechanisms to facilitate the selective uptake of particular nutrient classes [19] [21]. These specialized porins, such as maltoporin (LamB) for maltodextrins or ScrY for sucrose, incorporate specific binding sites within their channel interiors that selectively interact with target substrates [21]. This architecture enables a facilitated diffusion mechanism wherein the porin not only provides a physical passage but actively enhances the transport efficiency for cognate substrates while excluding unrelated molecules.

The structural basis for this specificity often involves strategically positioned aromatic residues that create a "greasy slide"— a continuous track of hydrophobic side chains that guides and binds specific substrates through the channel [21]. In LamB, for instance, arrays of tryptophan and tyrosine residues form stacking interactions with the glucose rings of maltooligosaccharides, significantly accelerating their diffusion rates compared to non-specific molecules of similar size [21]. This specialized transport mechanism allows bacteria to efficiently scavenge preferred nutrient sources from competitive environments, providing a selective growth advantage under nutrient-limited conditions.

Table 2: Functional Characteristics of Major Porin Types in Escherichia coli

| Porin | Type | Primary Substrates | Regulation | Role in Antibiotic Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OmpF | General diffusion | Small hydrophilic molecules <600 Da | Osmolarity, pH, temperature | Major route for β-lactam, fluoroquinolone influx |

| OmpC | General diffusion | Small hydrophilic molecules <600 Da | Osmolarity, growth phase | Alternative route for antibiotic influx |

| LamB | Specific (maltodextrin) | Maltose, maltodextrins | Maltose regulon | Minor role; can permit antibiotic passage |

| PhoE | Specific (anion) | Phosphates, anions | Phosphate starvation | Enhanced anion antibiotic uptake |

| OmpA | Monomeric (slow porin) | Small molecules | Constitutive, stress-responsive | Mainly structural; deletion increases susceptibility |

| OmpG | Monomeric (non-specific) | Small peptides, nutrients | Stress conditions | Alternative pathway when major porins downregulated |

Methodologies for Porin Functional Characterization

Planar Lipid Bilayer Electrophysiology

The characterization of porin channel properties has been revolutionized by planar lipid bilayer electrophysiology, a technique that enables precise quantification of single-channel conductance and gating behavior [23] [22]. This method involves reconstituting purified porin proteins into artificial lipid membranes that separate two electrolyte-filled chambers, allowing researchers to measure current fluctuations associated with ion passage through individual porin channels [22].

Experimental Protocol:

- Membrane Formation: Create an artificial lipid bilayer across a small aperture (typically 100-200 μm in diameter) separating two buffered salt solutions.

- Porin Incorporation: Add purified porin proteins, solubilized in a mild detergent, to one chamber. Porin molecules spontaneously incorporate into the artificial membrane.

- Current Measurement: Apply a constant voltage across the membrane and monitor current flow with a high-gain amplifier.

- Data Analysis: Observe stepwise increases in conductance as individual porin channels insert into the bilayer. Each step corresponds to the opening of a single channel.

- Pore Characterization: Calculate pore size from conductance measurements using established theoretical models. Determine ionic selectivity by measuring reversal potentials under salt gradients.

This technique has been instrumental in establishing the size exclusion limits of various porins—approximately 1.7 nm for mitochondrial porins and 3 nm for chloroplast porins, for example [22]. Furthermore, electrophysiological studies have revealed the voltage-dependent gating behavior of certain porins, such as the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) in mitochondrial membranes, which transitions between high-conductance anion-selective states at low membrane potentials and low-conductance cation-selective states at higher voltages [22].

Fluorescent Tracer Permeability Assays

Recent advances in porin research have leveraged fluorescent antibiotic analogues and other tracer molecules to investigate porin permeability in living bacterial cells [24]. This approach provides real-time information about porin function in native membranes under physiologically relevant conditions.

Experimental Protocol (2NBDG Uptake Assay):

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow bacterial cultures to mid-log phase under defined conditions appropriate for the porins being studied.

- Tracer Incubation: Add the fluorescent glucose analogue 2-deoxy-2-[(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]-D-glucose (2NBDG) to the bacterial suspension at concentrations typically ranging from 10-100 μM.

- Uptake Monitoring: Measure fluorescence accumulation over time using flow cytometry or time-lapse fluorescence microscopy for single-cell analysis.

- Ion Modulation: Test the effects of periplasmic ions on porin permeability using ionophores (e.g., CCCP for H+, valinomycin for K+) or genetically encoded ion pumps (e.g., ArchT for targeted periplasmic acidification).

- Mutant Analysis: Compare tracer uptake between wild-type and porin-deficient strains to determine the contribution of specific porins to overall permeability.

This methodology was pivotal in demonstrating the metabolic control of porin permeability, revealing how changes in periplasmic H+ and K+ concentrations dynamically regulate porin conductance in response to metabolic status [24]. The technique offers the significant advantage of assessing porin function in situ, capturing potential regulatory interactions and compensatory mechanisms that might be absent in purified reconstitution systems.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Fluorescent Tracer Permeability Assays. This diagram illustrates the key components and regulatory influences in porin permeability measurements using fluorescent tracers like 2NBDG.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Profiling

Systematic analysis of antibiotic susceptibility in porin-deficient mutants provides critical information about the contribution of specific porins to antibiotic influx [20]. This approach involves constructing isogenic strains with targeted deletions in porin genes and comparing their antibiotic resistance profiles to wild-type parents.

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Create in-frame deletion mutants of specific porin genes using λ Red recombinase-mediated homologous recombination or similar methods.

- Growth Standardization: Prepare bacterial suspensions to a standardized density (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard, approximately 1.5 × 10⁸ CFU/mL).

- Agar Dilution Assay: Incorporate two-fold serial dilutions of antibiotics into Mueller-Hinton agar plates.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Spot 10⁴ to 10⁵ CFU of each strain onto antibiotic-containing plates and incubate at 37°C for 16-20 hours.

- MIC Determination: Identify the lowest antibiotic concentration that completely inhibits visible growth.

This systematic approach revealed distinct roles for various porins: OmpF deficiency conferred resistance to multiple β-lactam antibiotics; OmpA deletion increased susceptibility to diverse drug classes due to compromised membrane integrity; while other porins like LamB and YddB played more specialized roles in transporting specific antibiotic molecules [20]. The methodology provides functional data that directly links specific porins to antibiotic resistance phenotypes, information crucial for understanding clinical resistance mechanisms.

Porins in Antibiotic Resistance and Therapeutic Development

Porin-Mediated Resistance Mechanisms

Porins contribute to antibiotic resistance through several distinct mechanisms, with modifications in porin expression or structure representing a common adaptive strategy in Gram-negative pathogens [20] [17]. The downregulation of major porin pathways, particularly OmpF and OmpC in Enterobacteriaceae, significantly reduces the intracellular accumulation of hydrophilic antibiotics, including β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and chloramphenicol [20]. This transcriptional regulation often occurs in response to environmental triggers, such as antibiotic exposure or oxidative stress, effectively diminishing the drug influx rate to levels that can be managed by efflux pumps or enzymatic inactivation systems.

Beyond quantitative changes in porin expression, structural modifications arising from mutations in porin-encoding genes can alter channel properties to limit antibiotic permeability while preserving essential nutrient uptake [17]. These mutations typically affect regions critical for channel function—particularly the constriction zone and loop structures—by reducing pore diameter, introducing charged residues that electrostatically repel antibiotics, or modifying gating behavior [17]. The remarkable adaptability of porins is evidenced by the low sequence identity (typically 20-30%) among porins from different bacterial species, despite conservation of the fundamental β-barrel architecture [21]. This sequence variability provides ample opportunity for evolutionary selection of resistance-conferring mutations while maintaining essential transport functions.

Metabolic Regulation of Porin Permeability

Emerging research has revealed sophisticated metabolic control mechanisms that dynamically regulate porin permeability in response to nutritional status and metabolic activity [24]. Single-cell imaging studies have demonstrated that porin conductance in Escherichia coli is controlled by changes in periplasmic H+ and K+ concentrations, which in turn are influenced by electron transport chain activity and inner membrane voltage-gated potassium channels (Kch) [24].

This ionic regulation operates through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Periplasmic Acidification: During growth on fatty acids, periplasmic pH decreases, promoting protonation of charged residues on the periplasmic surface of porins and reducing pore diameter through electrostatic effects.

- Potassium Modulation: High metabolic activity during glucose metabolism activates Kch channels, increasing periplasmic K+ concentration that enhances porin permeability, potentially to dissipate reactive oxygen species.

- Membrane Potential Coupling: Changes in inner membrane voltage correlate with porin activity, with depolarization events triggering increased porin permeability.

This metabolic regulation creates a paradigm where bacteria balance nutrient uptake needs against the vulnerability to antibiotic influx, effectively tuning outer membrane permeability according to metabolic status. This explains observed correlations between bacterial metabolic states and antibiotic susceptibility, such as the increased ciprofloxacin resistance of bacteria catabolizing lipids compared to those utilizing glucose [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Porin Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | Key Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Tracers | 2NBDG, Bocillin FL, Hoechst | Porin permeability quantification | Monitor solute influx through porin channels in live cells |

| Ion Modulators | CCCP, valinomycin, oligomycin | Ion regulation of porin conductance | Selectively alter H+ or K+ gradients across membranes |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | pHluorin, pHuji, GINKO1/2, QuasAr2 | Real-time ion and membrane potential monitoring | Measure dynamic changes in periplasmic/cytoplasmic ions and voltage |

| Optogenetic Tools | ArchT (light-activated proton pump) | Targeted periplasmic acidification | Precisely control periplasmic pH with temporal resolution |

| Genetic Tools | λ Red recombinase, pKD46, pCP20 | Isogenic porin mutant construction | Create targeted gene deletions and modifications for functional studies |

| Antibiotic Libraries | Diverse β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, others | MIC profiling and resistance assessment | Determine permeability coefficients and resistance contributions |

Porins as Therapeutic Targets and Adjuvants

The critical role of porins in antibiotic permeability has positioned them as attractive targets for novel therapeutic interventions against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens [18]. Two primary strategies have emerged: developing compounds that directly target porins to enhance antibiotic influx, and exploiting porin biology to improve existing antibiotics.

Polymyxin- and Aminoglycoside-Based Outer Membrane Permeabilizers: These established antibiotic classes possess inherent outer membrane-disrupting properties independent of their primary antimicrobial mechanisms [18]. Structural modification of these compounds has generated novel permeabilizers that synergize with conventional antibiotics:

- Polymyxin Derivatives: Engineered analogs with reduced intrinsic toxicity that disrupt LPS organization through electrostatic interactions with lipid A, compromising OM integrity.

- Aminoglycoside Variants: Modified structures that maintain the cationic properties necessary for OM disruption while minimizing ribosomal binding and associated toxicity.

These permeabilizers function primarily by displacing the divalent cations that bridge adjacent LPS molecules, thereby disrupting the ordered LPS lattice and increasing general permeability to hydrophobic compounds [18]. When administered in combination with conventional antibiotics, they can potentiate activity against resistant strains by enabling increased drug influx, effectively bypassing porin-related resistance mechanisms.

Figure 2: Porin-Mediated Resistance and Therapeutic Bypass Strategies. This diagram illustrates the relationship between porin-based resistance mechanisms and interventional approaches that utilize outer membrane permeabilizers.

The intricate architecture and regulated permeability of porin pathways represent a fundamental determinant of outer membrane barrier function in Gram-negative bacteria. The structural and functional distinction between general diffusion porins and substrate-specific channels establishes a sophisticated permeability network that balances nutritional requirements with protection against environmental threats, including antimicrobial agents. The emerging understanding of metabolic regulation of porin activity reveals an additional layer of complexity, demonstrating how bacteria dynamically adjust membrane permeability in response to nutritional status and metabolic demands.

From a clinical perspective, porin modifications constitute a significant resistance mechanism that diminishes the intracellular concentration of antibiotics, contributing to the escalating challenge of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections. The methodological advances in porin research—particularly single-cell imaging techniques and systematic genetic approaches—have unveiled the dynamic regulation and functional diversity of these channels, providing new insights into bacterial adaptation mechanisms under antibiotic pressure.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the structural basis of porin regulation by periplasmic ions, developing high-throughput screening methods for porin-targeted permeabilizers, and exploring the therapeutic potential of manipulating porin expression or function. As our understanding of porin biology continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for innovative therapeutic strategies that exploit these essential gateway proteins to overcome antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative pathogens.

The intrinsic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria presents a formidable challenge in clinical settings, primarily mediated by the sophisticated architecture of the outer membrane (OM). This asymmetric lipid bilayer, densely packed with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and punctuated by selective porin channels, acts as a potent permeability barrier that restricts antibiotic penetration. Combined with efflux pump systems, this native structure defines baseline antibiotic susceptibility profiles and contributes significantly to the multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype prevalent in pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii. This technical review examines the molecular determinants of OM-mediated intrinsic resistance, explores experimental methodologies for its investigation, and discusses emerging strategies to overcome this barrier for therapeutic intervention.

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria represents a unique biological interface that performs the dual function of providing protection while permitting selective exchange with the environment. This asymmetrical bilayer contains phospholipids in the inner leaflet and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in the outer leaflet, creating a chemically distinct boundary [10]. The intrinsic resistance afforded by this structure significantly limits treatment options for Gram-negative infections, with estimates indicating that more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur annually in the U.S. alone, resulting in approximately 35,000 deaths each year [25].

The clinical urgency is further highlighted by the World Health Organization's classification of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa as critical priority pathogens [26]. Understanding the molecular basis of OM-mediated resistance is therefore paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies to overcome this pervasive clinical challenge.

Structural Foundations of the Outer Membrane

Lipopolysaccharide Architecture and Barrier Function

The LPS layer forms the primary interface between Gram-negative bacteria and their environment, creating a formidable permeability barrier. Each LPS molecule consists of three structural domains:

- Lipid A: A glucosamine-based phospholipid anchor containing six saturated fatty acid chains (compared to two in typical phospholipids) that strongly interact laterally, creating a dense, low-fluidity membrane surface [10]

- Core oligosaccharide: A branched structure containing 6-10 sugars plus two Kdo (3-deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid) residues linked to lipid A

- O-antigen: A distal polysaccharide of varying length (1-40 repeating units) that contributes to strain-specific immunity and surface properties [10]

The tight packing of saturated fatty acid chains in Lipid A, combined with strong electrostatic interactions between anionic groups bridged by divalent cations (Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺), creates a hydrophobic barrier with exceptionally low fluidity that effectively excludes many hydrophobic antibiotics [10] [26]. Mutants with truncated LPS cores ("deep rough" mutants) demonstrate significantly increased sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics, bile salts, and detergents, confirming the critical protective role of intact LPS structure [10].

Porin-Mediated Permeation Pathways

For hydrophilic antibiotics, the primary penetration route occurs through general diffusion porins—β-barrel proteins that form water-filled channels across the OM. In E. coli, the major porins OmpF and OmpC form trimers, with each monomer creating a distinct channel:

- OmpF: Forms larger channels (approximately 1.16 nm diameter) preferentially expressed under low osmolarity conditions

- OmpC: Forms slightly narrower channels (approximately 1.08 nm diameter) dominant under high osmolarity [27]

These porins function as molecular sieves with size exclusion limits of approximately 600 Da, effectively preventing larger molecules from entering the periplasmic space [27]. The specificity and abundance of these porins are regulated by sophisticated systems including the OmpR-EnvZ two-component system and small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) such as MicF and MicC that fine-tune porin expression in response to environmental conditions [27].

Table 1: Major Porins in Escherichia coli and Their Regulatory Elements

| Porin | Channel Size | Expression Conditions | Primary Regulators | Permeability Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OmpF | ~1.16 nm | Low osmolarity, nutrient limitation | OmpR-EnvZ, MicF RNA | Larger pore, more permeable to β-lactams |

| OmpC | ~1.08 nm | High osmolarity, nutrient abundance | OmpR-EnvZ, MicC RNA | Smaller pore, restrictive barrier |

| OmpA | Variable | Constitutive | σE-dependent sRNAs | Primarily structural, limited pore activity |

Complementary Resistance Mechanisms

Efflux Pump Synergy with OM Barrier

Even when antibiotics successfully traverse the OM, Gram-negative bacteria employ a second line of defense through multidrug efflux pumps. The most clinically significant are the Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family pumps, which are unique to Gram-negative bacteria [26]. These sophisticated protein complexes span the entire cell envelope:

- Inner membrane component: Energy-dependent transporter (e.g., AcrB in E. coli)

- Periplasmic adaptor: Membrane fusion protein (e.g., AcrA) that bridges the inner and outer membranes

- Outer membrane component: Channel-forming protein (e.g., TolC) that provides exit conduit to extracellular space [27]

The synergy between the OM permeability barrier and efflux systems creates a highly effective defense mechanism. The restricted penetration through the OM allows efflux pumps more time to intercept and export antibiotics, significantly reducing the intracellular concentrations achievable by many drug classes [10] [26].

Antibiotic-Inactivating Enzymes

For compounds that successfully achieve intracellular accumulation, Gram-negative bacteria possess numerous antibiotic-inactivating enzymes including:

- β-lactamases (e.g., ESBLs, KPC, NDM, OXA) that hydrolyze β-lactam rings

- Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (acetyltransferases, phosphotransferases, nucleotidyltransferases)

- Ribosome-modifying methyltransferases that alter drug target sites [26]

These enzymatic systems provide a third layer of defense that works in concert with permeability barriers and efflux mechanisms to establish the characteristic intrinsic resistance profile of Gram-negative pathogens.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Intrinsic Resistance

Genome-Wide Mutant Screening

Systematic identification of genetic determinants governing intrinsic resistance has been facilitated by comprehensive mutant libraries. The Keio collection of E. coli single-gene knockouts (~3,800 strains) has enabled genome-wide screens for hypersusceptibility mutants [28] [29].

Protocol: Genome-wide susceptibility screening using the Keio collection

- Culture preparation: Grow knockout strains in 96-well format with LB media supplemented with antibiotic at IC₅₀ concentrations

- Growth assessment: Measure optical density at 600 nm after 18-24 hours incubation

- Data normalization: Express growth as fold-change compared to wild-type controls

- Hit identification: Classify strains with growth lower than two standard deviations from median as hypersensitive

- Validation: Confirm hypersusceptibility on solid media containing MIC, MIC/3, and MIC/9 antibiotic concentrations [28]

This approach identified 35 trimethoprim-hypersensitive and 57 chloramphenicol-hypersensitive mutants, with enrichment in genes involved in cell envelope biogenesis, membrane transport, and information transfer pathways [28] [29]. Particularly strong sensitization occurred with knockouts of:

- acrB (efflux pump component)

- rfaG and lpxM (LPS biosynthesis)

- nudB (folate metabolism, trimethoprim-specific) [28]

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for genome-wide identification of intrinsic resistance genes using the Keio collection of E. coli knockouts.

Transposon Sequencing (Tn-seq) for Resistance Gene Discovery

Tn-seq represents a powerful complementary approach that enables genome-wide assessment of gene contributions to antibiotic resistance under various selective conditions.

Protocol: Tn-seq for susceptibility determinant identification

- Library construction: Generate random transposon insertion mutant pools (>60,000 unique mutants)

- Selective pressure: Grow pools in sub-MIC antibiotics (typically causing 20-30% growth inhibition)

- Sample collection: Isolate DNA from start point and after 8 population doublings

- Sequencing & analysis: Amplify transposon insertion sites by PCR, sequence, and map to reference genome

- Fitness calculation: Determine gene-level fitness values based on insertion abundance changes [30]

Application in Acinetobacter baumannii identified 327 candidate susceptibility determinants, including ten genes affecting resistance to at least half of 20 tested antibiotics, highlighting both specific and broad-spectrum resistance elements [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for Intrinsic Resistance Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Outer Membrane-Mediated Resistance

| Resource/Tool | Specifications | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keio Collection [28] [29] | ~3,800 single-gene E. coli K-12 knockouts | Genome-wide susceptibility screening, identification of intrinsic resistome | Arrayed format, precise gene deletions, kanamycin-marked |

| Transposon Mutant Libraries [30] | >60,000 unique Tn10 or mariner insertions | Tn-seq fitness profiling, essentiality assessment under antibiotic pressure | Pooled format, deep coverage, quantitative fitness measurements |

| CARD Database [31] | 8,582 ontology terms, 6,442 reference sequences | AMR gene annotation, resistome prediction, mutation analysis | Curated resistance ontology, RGI prediction tool, regular updates |

| Porin-Specific Antibodies [27] | Anti-OmpF, Anti-OmpC, Anti-OmpA | Porin expression quantification, localization studies | Monitor porin regulation under different conditions |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors [28] | Chlorpromazine, PAβN, CCCP | Efflux activity assays, combination therapy studies | Chemical inhibition of RND-type pumps, synergy testing |

Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome OM-Mediated Resistance

Permeabilization Approaches

Several strategies aim to disrupt the OM barrier to enhance antibiotic penetration:

- Membrane-active agents: Polymyxin derivatives like polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN) compete for LPS binding sites, displacing stabilizing divalent cations and increasing membrane permeability [10]

- Chelators: EDTA and related compounds remove Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ ions from LPS, disrupting cross-bridging and creating phospholipid patches in the outer leaflet that are more permeable to hydrophobic compounds [10]

- Cationic peptides: Natural and synthetic peptides that target LPS and create transient disruptions in OM integrity

Efflux Pump Inhibition

Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) offer a complementary approach by blocking the active removal of antibiotics. However, recent research reveals limitations to this strategy:

- Genetic vs. pharmacological inhibition: While ΔacrB knockouts show dramatically reduced resistance evolution, pharmacological inhibition with chlorpromazine led to rapid resistance development against the EPI itself [28]

- Multidrug adaptation: Exposure to EPI-antibiotic combinations can select for mutations conferring broad-spectrum resistance beyond the target antibiotic [28]

Exploiting Native Transport Pathways

Structural-guided drug design aims to create antibiotics with improved penetration properties through native porin pathways. Molecular modeling of porin-antibiotic interactions enables optimization of key physicochemical parameters including:

- Molecular size/weight (preferably <600 Da)

- Hydrophilicity (favoring porin permeation)

- Charge distribution (minimizing interactions with porin constriction zones) [27] [26]

Figure 2: Strategic approaches to overcome outer membrane-mediated intrinsic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria.

Evolutionary Considerations and Resistance Development

Laboratory evolution experiments reveal that bacteria can adapt to perturbations in intrinsic resistance pathways through diverse genetic mechanisms:

- Sub-inhibitory antibiotic exposure: ΔacrB, ΔrfaG, and ΔlpxM mutants exposed to sub-MIC trimethoprim developed resistance through drug-specific mutations rather than compensatory evolution of the disrupted pathways [28]

- Differential adaptability: Resistance-conferring mutations could bypass defects in LPS biosynthesis more effectively than efflux deficiencies, suggesting efflux inhibition may provide more durable resistance prevention [28]

- Evolutionary constraints: Under high drug concentrations, intrinsic resistance knockouts were driven to extinction more frequently than wild-type strains, supporting the potential of targeting these pathways for "resistance-proofing" [28]

The native structure of the Gram-negative outer membrane constitutes a sophisticated, multifunctional barrier that defines baseline antibiotic susceptibility. Its asymmetric organization, combining a densely packed LPS leaflet with selective porin channels, creates a formidable physical and chemical obstacle to antimicrobial penetration. When combined with efflux systems and antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, this intrinsic resistome presents a challenging landscape for antibiotic development.

Advanced genetic tools and screening methodologies have enabled systematic dissection of the components comprising this resistance network, revealing both expected and unexpected genetic determinants. While strategies to disrupt this barrier show promise, evolutionary experiments highlight the remarkable adaptability of bacterial pathogens to circumvent these interventions. Future therapeutic approaches will likely require combination strategies that target multiple resistance mechanisms simultaneously while considering the evolutionary trajectories that enable resistance development. The ongoing characterization of the intrinsic resistome at molecular and structural levels continues to provide critical insights for developing next-generation antimicrobials capable of overcoming these native defense systems.

The intrinsic antibiotic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria presents a formidable challenge in clinical settings, largely due to the synergistic actions of two core defensive systems: the outer membrane (OM) permeability barrier and multidrug efflux pumps [32] [33]. Independently, each system provides a measure of protection; however, their functional interplay creates a highly effective, dual-layered defense that can profoundly reduce the intracellular concentration of antimicrobial agents [32] [33]. This synergy between passive permeability control and active efflux establishes a robust resistance phenotype that is difficult to overcome. The World Health Organization has identified antibiotic resistance as a critical global threat, with estimates attributing 4.95 million deaths to antimicrobial resistance in 2019, a figure projected to rise dramatically without effective interventions [32]. Understanding the molecular details of this collaborative defense is not merely an academic exercise but an urgent necessity to inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies, including efflux pump inhibitors and OM permeabilizers, aimed at resensitizing resistant pathogens [34].

Fundamental Mechanisms of the Outer Membrane Barrier

Structural Organization and Composition

The Gram-negative outer membrane is a unique asymmetric bilayer that serves as a formidable physical barrier. Its outer leaflet is predominantly composed of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which confers rigidity and a strong negative surface charge, while the inner leaflet consists of phospholipids [32] [5] [4]. A typical LPS molecule contains three structural domains: lipid A (a glucosamine-based phospholipid anchoring the molecule to the membrane), a core oligosaccharide, and the distal O-antigen polysaccharide [5] [4]. This specialized organization is crucial to the membrane's barrier function. The LPS layer forms a tightly packed, gel-like mesh that is reinforced by divalent cations (Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺) that bridge adjacent LPS molecules through electrostatic interactions [32] [5]. This structure severely restricts the penetration of hydrophobic compounds and provides an exceptional level of innate resistance to many antimicrobial agents.

Pathways for Antibiotic Permeation

Antibiotics and other solutes primarily traverse the outer membrane through two distinct pathways, each with specific physicochemical requirements:

- Porin-mediated pathway: General diffusion porins such as OmpF, OmpC, and OprD form water-filled channels that allow the passive diffusion of small, hydrophilic antibiotics like β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides [3] [5] [4]. These porins typically exhibit size exclusion limits, often permitting passage of molecules up to approximately 600 Da [4].

- Lipid-mediated pathway: Hydrophobic antibiotics such as macrolides and rifamycins traverse the OM by passive diffusion through the lipid bilayer itself [3] [5] [4]. Their permeation depends on physicochemical properties including lipophilicity, molecular size, and polarity [32].

Table 1: Major Outer Membrane Porins and Their Antibiotic Substrates

| Porin | Bacterial Species | Antibiotic Substrates |

|---|---|---|

| OmpF/OmpC | Escherichia coli | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol [33] [4] |

| OprD | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem) [33] |

| OmpK36/OmpK35 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones [4] |

| Omp36 | Enterobacter aerogenes | Cephalosporins, carbapenems [4] |

Multidrug Efflux Pump Systems

Architectural Diversity and Energy Coupling

Efflux pumps are active transporters that expel toxic compounds, including antibiotics, from the bacterial cell. They are classified into five major superfamilies based on their structure and energy source [34] [35] [36]:

- Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND): Proton motive force-dependent; often form tripartite complexes spanning both inner and outer membranes (e.g., AcrAB-TolC in E. coli, MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa) [34] [35].

- Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS): Proton motive force-dependent; primarily found in Gram-positive bacteria but present in Gram-negatives [34] [35].

- ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC): ATP hydrolysis-dependent; the only primary active transporters among efflux pumps [35] [36].

- Small Multidrug Resistance (SMR): Proton motive force-dependent; compact size with broad substrate recognition [34] [35].

- Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE): Sodium or proton motive force-dependent [34].

Of these, RND-type pumps are particularly significant in Gram-negative pathogens due to their broad substrate specificity and contribution to clinical multidrug resistance [34].

Physiological Functions Beyond Antibiotic Resistance

While efflux pumps are widely recognized for their role in antibiotic resistance, their fundamental physiological functions predate clinical antibiotic use [34] [35]. These natural roles include:

- Removal of bile acids and fatty acids in intestinal pathogens (e.g., AcrAB in E. coli) [35]

- Export of virulence factors and bacterial metabolites [34]

- Heavy metal detoxification and stress response modulation [34] [35]

- Biofilm formation and quorum sensing signal transport [35]

- Transport of cell envelope components [34]

The ability of these pumps to recognize antibiotics likely represents an accidental exploitation of their inherent capacity to identify molecules based on general physicochemical properties such as hydrophobicity, aromaticity, and ionizable character, rather than specific molecular structures [35].

Table 2: Major RND Efflux Pumps in Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens

| Efflux Pump | Bacterial Species | Regulator | Antibiotic Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| AdeABC | Acinetobacter baumannii | AdeRS, BaeSR | Aminoglycosides, β-lactams, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, tigecycline* [34] |

| MexAB-OprM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MexR | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, tetracyclines, macrolides [33] |

| AcrAB-TolC | Escherichia coli | AcrR, MarA, SoxS | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, tetracyclines, oxazolidinones [33] [35] |

| MexXY-OprM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MexZ | Aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones [33] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Permeability and Efflux

Quantitative Assessment of Antibiotic Accumulation

Direct measurement of intracellular antibiotic accumulation provides crucial insights into the efficiency of compound penetration and efflux. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) enables simultaneous quantitation of multiple antibiotics within bacterial cells [37].

Protocol: LC-MS-based Antibiotic Accumulation Assay

- Bacterial culture: Grow bacterial strains of interest to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5-0.6) in appropriate medium.

- Antibiotic exposure: Incubate bacteria with therapeutic concentrations of target antibiotics (e.g., 10× MIC) for 4 hours at 37°C with shaking.

- Sample processing: Harvest cells by rapid centrifugation (10,000 × g, 2 min, 4°C), wash twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline to remove extracellular antibiotic.

- Cell lysis: Lyse cell pellets using mechanical disruption (bead beating) or chemical lysis in acetonitrile:water (1:1) with 0.1% formic acid.

- LC-MS analysis: Separate antibiotics using reverse-phase chromatography (C18 column) with gradient elution (water:acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid). Perform detection using a high-resolution mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode.

- Data analysis: Normalize antibiotic signals to total cellular protein and compare to standard curves for absolute quantitation [37].

This approach has revealed striking variations in antibiotic accumulation in Mycobacterium abscessus, with greater than 1000-fold differences between the highest and lowest accumulating compounds, and a significant negative correlation between intracellular accumulation and MIC for drugs with intracellular targets [37].

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Reduction Assays

Evaluating the potentiation effects of OM-disrupting agents provides functional evidence of synergistic interactions between permeability barriers and efflux systems.

Protocol: MIC Reduction Assay with OM Permeabilizers

- Bacterial preparation: Prepare standardized bacterial inoculum (∼5×10⁵ CFU/mL) from mid-log phase cultures.

- Permeabilizer selection: Utilize OM-disrupting agents from different mechanistic classes:

- Cationic peptides: Colistin (0.35 μM) displaces divalent cation bridges between LPS molecules [32]

- Cationic steroids: Squalamine (5 μM) integrates into OM via electrostatic interactions [32]

- Chelators: EDTA (1 mM) extracts Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ ions that stabilize LPS [32]

- Polyaminoisoprenyl derivatives: NV716 (10 μM) binds to LPS and induces OM destabilization [32]

- MIC determination: Perform broth microdilution following CLSI guidelines with antibiotic serial dilutions in the presence and absence of sub-inhibitory concentrations of permeabilizers.

- Data interpretation: Consider a ≥4-fold reduction in MIC in the presence of permeabilizer as indicative of significant potentiation [32].

This methodology has demonstrated dramatic potentiation effects, such as a 128-fold reduction in doxycycline MIC against P. aeruginosa when combined with NV716 [32].

Computational Approaches for Studying Permeation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into antibiotic permeation across the OM. These computational methods complement empirical approaches by modeling molecular interactions between antibiotics and membrane components.

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Simulation of OM Permeation

- Membrane modeling: Construct an asymmetric OM bilayer with LPS in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet, incorporating relevant ion concentrations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) to stabilize LPS organization [33] [38].