Benchmarking Phenotypic Screening Assays: A Framework for Validation, AI Integration, and Translational Success

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking phenotypic screening assays, a critical process in modern drug discovery.

Benchmarking Phenotypic Screening Assays: A Framework for Validation, AI Integration, and Translational Success

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking phenotypic screening assays, a critical process in modern drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of phenotypic screening and its value in identifying first-in-class therapies. The content delves into advanced methodological approaches, including the integration of high-content imaging, multi-omics data, and artificial intelligence. It addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, from assay design to hit validation, and establishes rigorous standards for assay validation and comparative analysis against target-based methods. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance the reliability, efficiency, and translational impact of phenotypic screening campaigns in biomedical research.

The Resurgence of Phenotypic Screening: Principles and Proven Success

Modern Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful, systematic strategy for identifying novel therapeutics based on observable changes in physiological systems rather than predefined molecular targets. Historically, drug discovery relied on observing therapeutic effects on disease phenotypes, but this approach was largely supplanted by target-based methods following the molecular biology revolution. However, analysis revealing that a majority of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999-2008 were discovered empirically without a target hypothesis sparked a major resurgence in PDD beginning around 2011 [1]. Today's PDD represents a sophisticated evolution from its serendipitous origins, integrating advanced technologies including high-content imaging, artificial intelligence, complex disease models, and multi-omics approaches to systematically bridge biological complexity with therapeutic discovery [2] [3].

Table 1: Evolution of Phenotypic Drug Discovery

| Era | Primary Approach | Key Characteristics | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical (Pre-1980s) | Observation of therapeutic effects in humans or whole organisms | Serendipitous discovery, complex models | Penicillin, thalidomide |

| Target-Based Dominance (1980s-2000s) | Molecular target modulation | Reductionist, hypothesis-driven | Imatinib, selective kinase inhibitors |

| Modern PDD (2011-Present) | Systematic phenotypic screening with integrated technologies | Unbiased discovery with advanced tools for target deconvolution | Ivacaftor, risdiplam, lenalidomide analogs |

Core Principles: Phenotypic vs. Target-Based Screening

The fundamental distinction between phenotypic and target-based screening lies in their discovery bias and starting point. Phenotypic screening begins with measuring biological effects in systems modeling disease, without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets, enabling unbiased identification of novel mechanisms [3]. In contrast, target-based screening begins with a predefined molecular target and identifies compounds that modulate it, following a hypothesis-driven approach limited to known biological pathways [2].

This distinction creates significant methodological differences. Phenotypic screening evaluates compounds based on functional outcomes in biologically complex systems, often using high-content imaging and complex cellular models. Target-based screening relies heavily on structural biology, computational modeling, and enzyme assays focused on specific molecular interactions [3]. The strategic advantage of modern PDD is its ability to capture complex biological mechanisms and discover first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action, particularly for diseases with poorly understood pathophysiology or polygenic origins [1].

Table 2: Systematic Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Parameter | Phenotypic Screening | Target-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Bias | Unbiased, allows novel target identification | Hypothesis-driven, limited to known pathways |

| Mechanism of Action | Often unknown at discovery, requires deconvolution | Defined from the outset |

| Biological Complexity | Captures complex interactions and polypharmacology | Reductionist, single-target focus |

| Technological Requirements | High-content imaging, functional genomics, AI analytics | Structural biology, computational modeling, enzyme assays |

| Success Profile | Higher rate of first-in-class drug discovery | More efficient for best-in-class drugs following validation |

| Primary Challenge | Target deconvolution and validation | Relevance of target to human disease |

Key Technological Advances Enabling Modern PDD

Advanced Biological Model Systems

Modern PDD utilizes increasingly sophisticated biological models that better recapitulate human disease physiology. Three-dimensional organoids and spheroids have emerged as crucial tools that mimic tissue architecture and function more accurately than traditional 2D cultures, particularly in cancer and neurological research [3]. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived models enable patient-specific drug screening and disease modeling, while organ-on-chip systems recapitulate human physiological processes by merging cell culture with microengineering techniques [3]. These advanced models provide the physiological relevance necessary for phenotypic screening to capture meaningful biological responses that translate to clinical efficacy.

High-Content Analysis and Artificial Intelligence

The integration of high-content imaging with AI-powered data analysis has revolutionized phenotypic screening by enabling quantitative assessment of complex cellular features at scale [2] [3]. Machine learning algorithms can identify subtle phenotypic patterns in high-dimensional datasets that might escape human detection, enabling systematic identification of predictive patterns and emergent mechanisms [2]. These technologies have transformed phenotypic screening from a qualitative observation method to a quantitative, data-rich discovery platform.

Automated High-Throughput Screening

Automation innovations have enabled phenotypic screening to achieve the throughput necessary for industrial-scale drug discovery. Modern platforms can systematically screen hundreds of thousands of compounds in complex cellular models, making PDD feasible for early-stage discovery programs [3]. The cell-based assay market, valued at USD 19.45 billion in 2025, reflects substantial investment in these technologies, with high-throughput screening accounting for 42.19% of market share in 2024 [4].

Experimental Framework: Methodologies and Protocols

Standardized Phenotypic Screening Workflow

The modern phenotypic screening workflow follows a systematic, multi-stage process designed to identify and validate compounds based on functional therapeutic effects.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Content Phenotypic Screening in 3D Organoid Models

Application: Oncology drug discovery, regenerative medicine, toxicity assessment [3] [4]

Methodology:

- Organoid Generation: Seed primary cells or stem cells in extracellular matrix scaffolds and culture with specific growth factor cocktails to promote self-organization into 3D structures (7-21 days)

- Compound Treatment: Apply compound libraries using automated liquid handlers with concentration ranges (typically 1 nM - 10 μM) and include appropriate controls (DMSO vehicle, reference compounds)

- Phenotypic Endpoint Staining: Fix and immunostain for relevant markers (viability, apoptosis, differentiation, cell-type specific proteins)

- High-Content Imaging: Acquire images using automated confocal microscopy (≥10 fields per well, multiple channels)

- Quantitative Image Analysis: Extract features using AI-based segmentation and classification algorithms (morphology, intensity, texture, spatial relationships)

- Hit Selection: Identify compounds inducing desired phenotype using statistical criteria (Z-score > 3, effect size > 50% of control)

Protocol 2: Mechanism-of-Action Deconvolution Using Functional Genomics

Application: Target identification for phenotypic hits [2] [5]

Methodology:

- Resistance Generation: Culture cells with phenotypic hits at increasing concentrations over 4-8 weeks to generate resistant populations

- Whole Exome Sequencing: Sequence parental and resistant clones (minimum 100x coverage) to identify acquired mutations

- CRISPR Screening: Perform genome-wide knockout or activation screens in the presence of phenotypic hits to identify genetic modifiers of compound sensitivity

- Chemical Proteomics: Immobilize active compounds on solid support for pull-down experiments with cell lysates; identify binding partners via mass spectrometry

- Computational Target Prediction: Apply tools like DePick [5] to integrate multi-omics data and predict drug target-phenotype associations

- Validation:

- Gene editing to confirm target necessity

- Cellular thermal shift assays to verify direct binding

- Rescue experiments with wild-type vs. mutant targets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Platforms for Modern Phenotypic Screening

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC Differentiation Kits | Generate patient-specific cell types for disease modeling | Neurological disorders, cardiac toxicity screening |

| Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels | Support 3D organoid formation and maintenance | Tumor organoids, tissue morphogenesis studies |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence Kits | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein markers | High-content analysis of complex phenotypes |

| Live-Cell Fluorescent Reporters | Real-time monitoring of signaling pathway activity | GPCR signaling, kinase activation, calcium flux |

| CRISPR Modification Tools | Gene editing for target validation and model generation | Isogenic cell lines, functional genomics screens |

| Spectral Flow Cytometry Panels | High-parameter single-cell analysis | Immune cell profiling, rare cell population identification |

| AI-Powered Image Analysis Software | Automated quantification of complex morphological features | Phenotypic hit identification, mechanism classification |

Case Studies: Successful Clinical Applications

Immunomodulatory Drugs (Thalidomide Analogs)

The discovery and optimization of thalidomide analogs represents a classic example where both the parent compound and subsequent analogs were developed exclusively through phenotypic screening [2]. Phenotypic screening of thalidomide analogs identified lenalidomide and pomalidomide, which exhibited significantly increased potency for downregulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production with reduced sedative and neuropathic side effects [2]. Only subsequent studies identified cereblon as the primary binding target, with the mechanism involving altered substrate specificity of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex leading to degradation of lymphoid transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 [2]. This novel mechanism has now become foundational for targeted protein degradation strategies, including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [2].

Cystic Fibrosis Correctors and Potentiators

Target-agnostic compound screens using cell lines expressing disease-associated CFTR variants identified both potentiators (ivacaftor) that improve channel gating and correctors (tezacaftor, elexacaftor) that enhance CFTR folding and membrane insertion through unexpected mechanisms [1]. The triple combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor and ivacaftor was approved in 2019 and addresses 90% of the CF patient population [1]. This case exemplifies how phenotypic screening can identify compounds with novel mechanisms that would have been difficult to predict through target-based approaches.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy Therapeutics

Phenotypic screens identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing to increase levels of full-length SMN protein [1]. The compounds function by engaging two sites at the SMN2 exon 7 and stabilizing the U1 snRNP complex—an unprecedented drug target and mechanism of action [1]. Risdiplam, resulting from this approach, gained FDA approval in 2020 as the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA, demonstrating how phenotypic screening can expand druggable target space to previously unexplored cellular processes [1].

Integrated Approaches: The Future of PDD

The most advanced modern PDD workflows integrate phenotypic and targeted approaches to leverage the strengths of both strategies. Target-based workflows increasingly incorporate phenotypic assays to validate candidate molecules, creating a feedback loop between mechanistic precision and biological complexity [2]. Conversely, phenotypic screening coupled with advanced analytical platforms can reveal nuanced biological responses that inform target identification and hypothesis refinement [2].

This integrated approach is accelerated by advances in computational modeling, artificial intelligence, and multi-omics technologies that are reshaping drug discovery pipelines [2]. Leveraging both paradigms, future immune drug discovery will depend on adaptive, integrated workflows that enhance efficacy and overcome resistance [2].

Modern phenotypic drug discovery has evolved from its serendipitous origins into a systematic, technology-driven approach that complements target-based strategies. By focusing on therapeutic effects in biologically relevant systems, PDD continues to deliver first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action, expanding the druggable genome to include previously inaccessible targets. The ongoing integration of advanced model systems, AI-powered analytics, and multi-omics technologies positions PDD as an essential component of comprehensive drug discovery portfolios, particularly for complex diseases with polygenic origins or poorly understood pathophysiology. As the field continues to mature, standardized benchmarking of phenotypic screening approaches will be crucial for optimizing discovery workflows and maximizing the translational potential of this powerful strategy.

Innovation in pharmaceutical research has been below expectations for a generation, despite the promise of the molecular biology revolution. Surprisingly, an analysis of first-in-class small-molecule drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 1999 and 2008 revealed that more were discovered through phenotypic drug discovery (PDD) strategies than through contemporary molecular targeted approaches [6]. This unexpected finding, in conjunction with persistent challenges in validating molecular targets, has sparked a grassroots movement and broader trend in pharmaceutical research to reconsider the application of modern physiology-based PDD strategies [6]. This neoclassic vision for drug discovery combines phenotypic and functional approaches with technology innovations resulting from the genomics-driven era of target-based drug discovery (TDD) [6].

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their starting points. PDD involves identifying compounds that modify disease phenotypes without prior knowledge of specific molecular targets, screening candidates based on their ability to elicit desired therapeutic effects in cellular or animal models [7]. In contrast, TDD aims to find drugs that interact with a specific target molecule believed to play a crucial role in the disease process [7]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these divergent strategies, examining their respective strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications within the context of modern drug development.

Fundamental Principles and Philosophical Frameworks

Core Conceptual Differences

The philosophical divergence between PDD and TDD represents one of the most fundamental schisms in drug discovery strategy. PDD approaches do not rely on knowledge of the identity of a specific drug target or a hypothesis about its role in disease, in contrast to the target-based strategies that have dominated pharmaceutical industry efforts for decades [8]. This empirical, biology-first strategy provides tool molecules to link therapeutic biology to previously unknown signaling pathways, molecular mechanisms, and drug targets [1].

Target-based strategies rely on a profound understanding of underlying biological pathways and molecular targets associated with disease, offering the advantage of increased specificity and reduced off-target effects [7]. However, this reductionist approach potentially limits serendipitous discoveries of novel mechanisms and depends entirely on the validity of the target hypothesis [1]. The chain of translatability—from molecular target to cellular function to tissue physiology to clinical benefit—represents a significant vulnerability in the TDD paradigm, where failure at any link invalidates the entire approach [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of PDD and TDD Approaches

| Characteristic | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease phenotype or biomarker | Specific molecular target |

| Knowledge Requirement | No target hypothesis needed | Deep understanding of target biology |

| Mechanism of Action | Often identified post-discovery | Defined before screening begins |

| Druggable Space | Includes novel, unexpected targets | Limited to known, validated targets |

| Historical Success | Majority of first-in-class medicines [1] | Majority of follower drugs |

| Technical Challenge | Target deconvolution difficult | Target validation critical |

The Biological Complexity Argument

The resurgence of interest in PDD approaches is largely based on their potential to address the incompletely understood complexity of diseases [8]. Biological systems exhibit emergent properties that cannot be fully predicted from their individual components, creating a fundamental challenge for reductionist approaches. Complex diseases like cancer, neurodegenerative conditions, and metabolic disorders involve polygenic interactions, compensatory pathways, and non-linear dynamics that may be better addressed through phenotypic approaches that preserve system-level biology [1].

The concept of a "chain of translatability" has been introduced to contextualize how PDD can best deliver value to drug discovery portfolios [8]. This framework emphasizes that the predictive power of any discovery approach depends on maintaining biological relevance throughout the discovery pipeline, from initial screening to clinical application. Phenotypic assays that more closely recapitulate human disease pathophysiology may offer superior translatability by capturing complex interactions between multiple cell types, tissue structures, and physiological contexts that are lost in reductionist target-based approaches [8].

Recent Successes and Notable Case Studies

Phenotypic Drug Discovery Breakthroughs

PDD has demonstrated remarkable success in delivering first-in-class medicines across diverse therapeutic areas. Notable examples include ivacaftor and lumicaftor for cystic fibrosis, risdiplam and branaplam for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), SEP-363856 for schizophrenia, KAF156 for malaria, and crisaborole for atopic dermatitis [1]. These successes share a common theme: the identification of therapeutic agents through their effects on disease-relevant phenotypes without predetermined target hypotheses.

The treatment of cystic fibrosis (CF) has been revolutionized by PDD approaches. CF is a progressive and frequently fatal genetic disease caused by various mutations in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that decrease CFTR function or interrupt CFTR intracellular folding and plasma membrane insertion [1]. Target-agnostic compound screens using cell lines expressing wild-type or disease-associated CFTR variants identified compound classes that improved CFTR channel gating properties (potentiators such as ivacaftor), as well as compounds with an unexpected mechanism of action: enhancing the folding and plasma membrane insertion of CFTR (correctors such as tezacaftor and elexacaftor) [1]. A combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor and ivacaftor was approved in 2019 and addresses 90% of the CF patient population [1].

Similarly, type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a rare neuromuscular disease with 95% mortality by 18 months of age, has been transformed by phenotypically-discovered therapeutics. SMA is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SMN1 gene, which encodes the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein essential for neuromuscular junction formation and maintenance [1]. Humans have a closely related SMN2 gene, but a mutation affecting its splicing leads to exclusion of exon 7 and production of an unstable shorter SMN variant. Phenotypic screens identified small molecules that modulate SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing and increase levels of full-length SMN protein [1]. One such compound, risdiplam, was approved by the FDA in 2020 as the first oral disease-modifying therapy for SMA, working through the unprecedented mechanism of stabilizing the U1 snRNP complex to promote correct SMN2 splicing [1].

Target-Based Discovery Achievements

While PDD has excelled in delivering first-in-class medicines, TDD has proven highly effective for developing optimized follower drugs with improved specificity and safety profiles. The most successful examples come from oncology, where targeted therapies have transformed treatment for specific molecularly-defined patient subgroups.

Imatinib, the first rationally designed kinase inhibitor approved by the FDA for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), represents a landmark achievement for TDD [1]. Initially developed as an inhibitor of the BCR-ABL fusion protein driving CML pathogenesis [1], imatinib also exhibits activity toward c-KIT and PDGFR receptor tyrosine kinases, which contribute to its efficacy in other cancers [1]. This example highlights how even target-based approaches can yield agents with unanticipated polypharmacology that may contribute to clinical efficacy.

Direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C represent another TDD success story. Through precise targeting of specific viral proteins including NS3/4A protease, NS5A, and NS5B polymerase, these agents achieve cure rates exceeding 90% with minimal side effects [1]. The development of these agents was facilitated by prior knowledge of the viral lifecycle and essential pathogen-specific targets, creating an ideal scenario for target-based approaches.

Table 2: Representative Drug Discovery Successes by Approach

| Therapeutic Area | PDD-Derived Agents | TDD-Derived Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Diseases | Ivacaftor, lumacaftor, elexacaftor (cystic fibrosis); Risdiplam (spinal muscular atrophy) | Nusinersen (spinal muscular atrophy) |

| Infectious Diseases | KAF156 (malaria) | Direct-acting antivirals (hepatitis C); Antibiotics |

| Oncology | Lenalidomide (multiple myeloma) | Imatinib (CML); Kinase inhibitors; PARP inhibitors |

| Neuroscience | SEP-363856 (schizophrenia) | SSRIs; Antipsychotics |

| Dermatology | Crisaborole (atopic dermatitis) | JAK inhibitors |

Experimental Platforms and Methodological Comparisons

Phenotypic Screening Workflows and Platforms

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated biological systems and readouts that capture disease-relevant complexity. The typical workflow begins with developing a physiologically-relevant disease model that exhibits a measurable phenotype connected to human disease pathophysiology. These platforms range from primary human cell cultures to complex three-dimensional organoids and microphysiological systems [9].

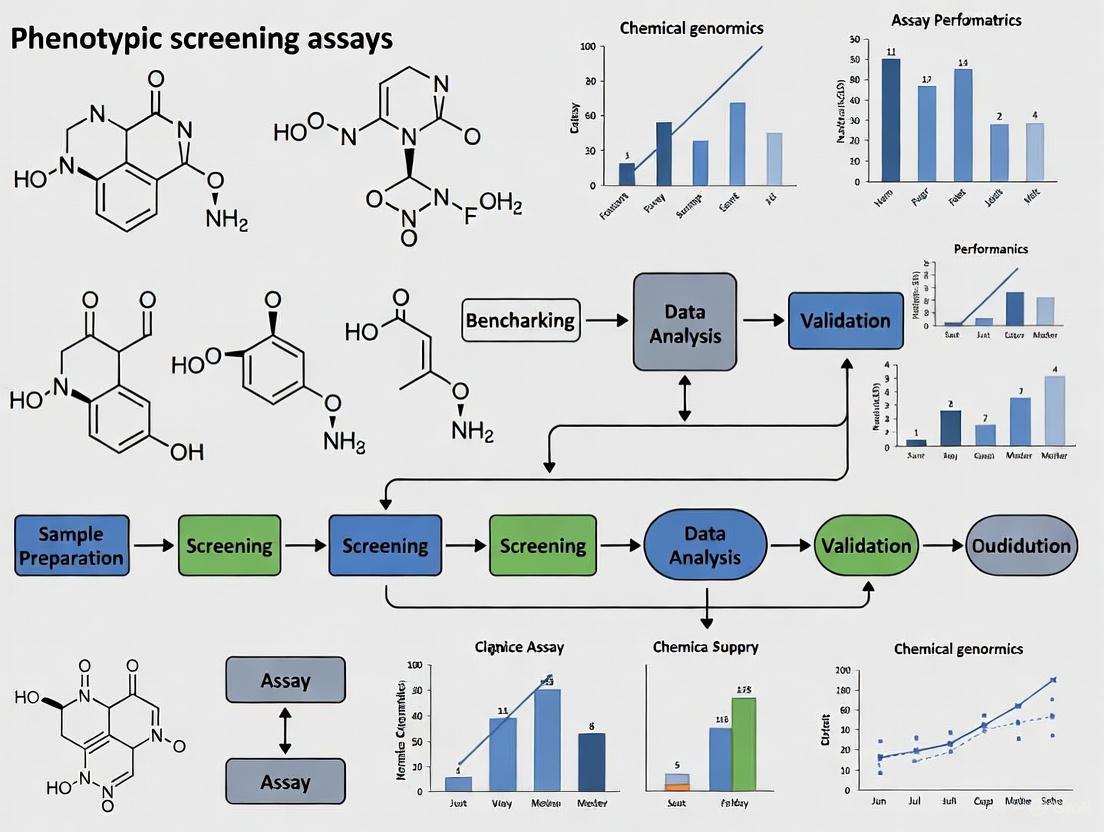

Diagram 1: Phenotypic screening workflow with key challenges. Target deconvolution remains a primary bottleneck.

Advanced phenotypic platforms now include human primary cells, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived models, microphysiological systems ("organ-on-a-chip" technologies), and high-content imaging approaches such as Cell Painting that capture multidimensional morphological profiles [9] [10]. These systems aim to bridge the translational gap between traditional cell lines and human pathophysiology by preserving more relevant cellular contexts, interactions, and disease phenotypes.

The "Phenotypic Screening Rule of 3" framework has been proposed to enhance the predictive validity of these assays, emphasizing three key elements: (1) inclusion of disease-relevant human cellular contexts, (2) measurement of disease-relevant phenotypes, and (3) demonstration of pharmacological responses to known agents [8]. Implementation of this framework helps ensure that phenotypic screens generate clinically translatable results.

Target-Based Screening Methodologies

Target-based screening employs highly controlled reductionist systems designed to isolate specific molecular interactions. The typical TDD workflow begins with target identification and validation, followed by development of screening assays that directly measure compound binding or functional modulation of the target.

Diagram 2: Target-based screening workflow highlighting key risk points in target validation and translational relevance.

Standard TDD methodologies include biochemical assays using purified protein targets, binding assays (SPR, FRET, TR-FRET), enzymatic activity assays, and cellular reporter systems. The common feature across these approaches is the precise knowledge of the molecular target being modulated, which enables structure-based drug design and optimization.

Recent innovations in TDD include chemoproteomics platforms such as IMTAC (Isobaric Mass-Tagged Affinity Characterization), which enables screening of small molecules against the entire proteome of live cells [7]. This approach combines aspects of both PDD and TDD by allowing target-agnostic screening in physiologically relevant environments while simultaneously identifying specific molecular targets through mass spectrometry analysis [7].

Technological Innovations and Emerging Solutions

Bridging the Divide: Hybrid Approaches

The historical dichotomy between PDD and TDD is increasingly being bridged by hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both strategies. These integrated workflows typically begin with phenotypic screening to identify compounds with desired functional effects, followed by target identification and mechanistic studies to understand the molecular basis of activity.

The IMTAC platform represents one such hybrid approach, consisting of three key components: (1) designing and synthesizing high-quality libraries of covalent small molecules, (2) screening against the entire proteome of live cells, and (3) qualitative and quantitative mass spectrometry analysis to identify and characterize interacting proteins [7]. This platform has successfully identified small molecule ligands for over 4,000 proteins, approximately 75% of which lacked known ligands prior to discovery, including many traditionally "undruggable" targets such as transcription factors and E3 ligases [7].

CRISPR screening technology has also emerged as a powerful tool for bridging phenotypic and target-based approaches. By enabling systematic investigation of gene-drug interactions across the genome, CRISPR screening provides a precise and scalable platform for functional genomics [11]. Integration of CRISPR screening with organoid models and artificial intelligence expands the scale and intelligence of drug discovery, offering robust support for uncovering new therapeutic targets and mechanisms [11].

Artificial Intelligence and Computational Tools

Computational approaches are playing an increasingly important role in both PDD and TDD. DeepTarget is an open-source computational tool that integrates large-scale drug and genetic knockdown viability screens with omics data to determine cancer drugs' mechanisms of action [12]. Benchmark testing revealed that DeepTarget outperformed currently used tools such as RoseTTAFold All-Atom and Chai-1 in seven out of eight drug-target test pairs for predicting drug targets and their mutation specificity [12].

PhenoModel represents another computational innovation specifically designed for phenotypic drug discovery. This multimodal molecular foundation model uses a unique dual-space contrastive learning framework to connect molecular structures with phenotypic information [10]. The model is applicable to various downstream drug discovery tasks, including molecular property prediction and active molecule screening based on targets, phenotypes, and ligands [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phenotypic and Target-Based Screening

| Technology/Reagent | Primary Application | Key Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | PDD | Disease modeling with patient-specific genetic backgrounds | Neuronal disease models, cardiac toxicity assessment |

| Organ-on-a-Chip | PDD | Microphysiological systems mimicking human organ complexity | Glomerulus-on-a-chip for diabetic nephropathy [8] |

| Cell Painting | PDD | High-content morphological profiling using multiplexed dyes | Phenotypic profiling, mechanism of action studies [10] |

| CRISPR Libraries | Both | Genome-wide functional screening | Target identification/validation, synthetic lethality screens [11] |

| Chemoproteomic Platforms | Both | Target identification and engagement in live cells | IMTAC for covalent ligand discovery [7] |

| Covalent Compound Libraries | TDD | Targeting shallow or transient protein pockets | KRAS G12C inhibitors, targeted protein degraders [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Studies

Protocol 1: Phenotypic Screening for Compound Hit Identification

Objective: To identify compounds that reverse a disease-associated phenotype in a physiologically relevant cell-based model.

Materials and Reagents:

- Disease-relevant cell model (primary cells, iPSC-derived cells, or engineered cell lines)

- Compound library (typically 10,000-100,000 compounds)

- Phenotypic readout reagents (cell viability assays, high-content imaging dyes, functional reporters)

- Cell culture media and supplements appropriate for the cell type

- Automation-compatible microplates (96-well or 384-well format)

Procedure:

- Culture cells under conditions that promote expression of the disease-relevant phenotype.

- Dispense cells into microplates using automated liquid handling (1,000-5,000 cells/well for 384-well format).

- Incubate plates overnight under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Transfer compound libraries using pintool or acoustic dispensing systems (final concentration typically 1-10 μM).

- Incubate for an appropriate duration based on the phenotypic readout (24-72 hours).

- Apply phenotypic assay reagents according to established protocols.

- Acquire readouts using appropriate instrumentation (plate readers, high-content imagers).

- Analyze data using specialized software (cell classification algorithms, pathway mapping tools).

Validation Metrics:

- Z'-factor >0.5 for robust assay performance

- Signal-to-background ratio >3:1

- Coefficient of variation <10% for control wells

- Demonstration of expected responses to control compounds with known mechanisms [8]

Protocol 2: Target Deconvolution for Phenotypic Hits

Objective: To identify the molecular target(s) responsible for phenotypic effects of confirmed hits.

Materials and Reagents:

- Phenotypic hit compounds (with appropriate chemical handles for immobilization if needed)

- Cell lysates or live cells for binding studies

- Affinity chromatography resins (sepharose, magnetic beads)

- Chemoproteomic probes (if using IMTAC or similar platforms)

- Mass spectrometry reagents and instrumentation

- CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing components (for functional validation)

Procedure:

- Design and synthesize chemical probes based on hit compound structure (e.g., with biotin or fluorescent tags).

- Incubate probes with live cells or cell lysates to allow target engagement.

- Crosslink bound targets if using reversible binders (optional).

- Isplicate probe-target complexes using affinity purification.

- Wash extensively to remove non-specific binders.

- Elute bound proteins using competitive compound or denaturing conditions.

- Digest proteins with trypsin and prepare for mass spectrometry.

- Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS using data-dependent acquisition.

- Process raw data using search engines (MaxQuant, Spectronaut) against appropriate databases.

- Validate putative targets through orthogonal approaches (genetic knockdown, biophysical binding assays).

Validation Metrics:

- Dose-dependent competition with free compound

- Correlation between binding affinity and phenotypic potency

- Genetic perturbation reproduces phenotypic effect

- Target engagement demonstrated in cellular context [7]

The historical competition between phenotypic and target-based drug discovery is evolving toward a more integrated future. Rather than positioning PDD and TDD as mutually exclusive alternatives, the most productive approach strategically combines both methodologies to address different aspects of the drug discovery pipeline. PDD excels at identifying novel mechanisms and first-in-class therapies, while TDD provides efficient optimization and development of follower drugs with improved properties.

The expanding toolkit for drug discovery—including human iPSC models, organ-on-a-chip systems, CRISPR functional genomics, chemoproteomics, and artificial intelligence—is blurring the traditional boundaries between phenotypic and target-based approaches [9] [11]. These technologies enable researchers to preserve biological complexity while still obtaining mechanistic insights, potentially overcoming historical limitations of both strategies.

For the drug discovery professional, the key consideration is not which approach is universally superior, but which strategy or combination of strategies is most appropriate for a specific therapeutic question. Factors including the complexity of the disease biology, the availability of validated targets, the need for novel mechanisms, and the available toolset should inform this strategic decision. By thoughtfully integrating the strengths of both phenotypic and target-based approaches, researchers can address biological complexity with unprecedented sophistication, potentially accelerating the delivery of transformative medicines to patients.

The development of novel therapeutics has been profoundly influenced by two primary screening strategies: target-based and phenotypic screening. While target-based approaches focus on modulating a specific, pre-identified protein, phenotypic screening identifies compounds that elicit a desired cellular or tissue-level response without prior knowledge of the specific molecular target[s] [13]. This article benchmarks these approaches through three case studies: ivacaftor, risdiplam, and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), which collectively demonstrate how phenotypic screening can deliver transformative therapies for complex genetic diseases. Advances in computational methods, such as active reinforcement learning frameworks, are now addressing historical challenges in phenotypic screening by improving the prediction of compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes, enabling smaller and more focused screening campaigns [13].

Case Study 1: Ivacaftor – Correcting CFTR Protein Function

Ivacaftor (VX-770) represents a landmark as one of the first therapies to address the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis (CF) rather than merely managing symptoms [14]. CF is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, leading to abnormal chloride and sodium transport across epithelial membranes [15]. This results in thick, sticky mucus in organs such as the lungs and pancreas, causing progressive obstructive lung disease, pancreatic insufficiency, and premature mortality [14].

Mechanism of Action

Ivacaftor acts as a CFTR potentiator that selectively enhances the channel open probability (gating) of CFTR proteins at the epithelial cell surface [14] [15]. It specifically targets Class III CFTR mutations (gating mutations), where the protein localizes correctly to the cell membrane but cannot undergo normal cAMP-mediated activation [14]. By binding to CFTR, ivacaftor stabilizes the open state of the channel, enabling chloride transport and restoring ion and water balance [14]. The drug demonstrates targeted efficacy, showing significant clinical improvement in patients with gating mutations like G551D but minimal effect in those homozygous for the F508del mutation (a Class II folding mutation) [14] [15].

Key Experimental Data and Clinical Efficacy

Clinical trials established ivacaftor's profound clinical impact, with data summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy Data for Ivacaftor from Pivotal Trials

| Clinical Parameter | Baseline to 24-Week Change (Ivacaftor) | Baseline to 24-Week Change (Placebo) | Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Function (FEV1) | +10.4% to +17.5% [14] | Not specified | Patients with G551D mutation [14] |

| Sweat Chloride Concentration | -55.5 mmol/L [14] | -1.8 mmol/L [14] | Patients with G551D mutation [14] |

| Weight Gain | +3.7 kg [14] | +1.8 kg [14] | Children aged 6-11 [14] |

| Respiratory Improvement | Significant improvement vs placebo | No significant improvement | Observed after 2 weeks of treatment [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Ivacaftor Development

1. Electrophysiological CFTR Function Assays: The primary in vitro method utilized Ussing chamber experiments on primary human bronchial epithelial cells from CF patients with gating mutations. Cells were grown at air-liquid interface, and short-circuit current was measured after sequential addition of cAMP agonists and ivacaftor to quantify restoration of chloride transport [14].

2. Clinical Trial Endpoints: Pivotal Phase 3 trials employed forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as the primary endpoint. Key secondary endpoints included sweat chloride testing as a pharmacodynamic biomarker, pulmonary exacerbation frequency, and patient-reported quality of life measures [14] [15].

Case Study 2: Risdiplam – Modifying SMN2 Splicing

Risdiplam (Evrysdi) is an orally bioavailable small molecule approved for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a severe neurodegenerative disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality [16] [17]. SMA results from homozygous mutation or deletion of the survival of motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, causing progressive loss of spinal motor neurons and skeletal muscle weakness [16]. The paralogous SMN2 gene serves as a potential compensatory source of SMN protein, but a single nucleotide substitution causes exclusion of exon 7 during splicing, producing mostly truncated, unstable protein [16] [18].

Mechanism of Action

Risdiplam is an mRNA splicing modifier that binds specifically to two sites on SMN2 pre-mRNA: the 5' splice site (5'ss) of intron 7 and the exonic splicing enhancer 2 (ESE2) in exon 7 [16] [18]. This binding stabilizes the transient double-strand RNA structure formed between the 5'ss and the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (U1 snRNP), effectively converting the weak 5' splice site into a stronger one [16]. The result is increased inclusion of exon 7 in mature SMN2 transcripts, production of functional SMN protein, and compensation for the loss of SMN1 function [18].

Key Experimental Data and Clinical Efficacy

Table 2: Clinical Efficacy Data for Risdiplam from Pivotal Trials

| Trial Name | Patient Population | Key Efficacy Findings | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIREFISH [16] | Type 1 SMA infants | Improved event-free survival and motor milestone development | Well-tolerated |

| SUNFISH [16] | Type 2/3 SMA (2-25 years) | Statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in motor function | Well-tolerated across all age groups |

| Pharmacodynamics | Various SMA types | ~2-fold increase in SMN protein concentration after 12 weeks [18] | - |

Experimental Protocols for Risdiplam Development

1. High-Throughput Splicing Modification Screen: Discovery began with a cell-based high-throughput screening campaign designed to identify compounds that increase inclusion of exon 7 during SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing [16]. A coumarin derivative was identified as an initial hit and subsequently optimized through extensive medicinal chemistry to improve potency and specificity while reducing off-target effects [16].

2. SMN Protein Quantification: Clinical trials measured SMN protein levels in peripheral blood as a key pharmacodynamic biomarker using immunoassays. Patients treated with risdiplam demonstrated approximately a 2-fold increase in SMN protein concentration after 12 weeks of therapy [18].

Case Study 3: Immunomodulatory Drugs (IMiDs) – Redirecting E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Activity

Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), including lenalidomide and pomalidomide, are thalidomide derivatives that revolutionized multiple myeloma (MM) treatment [19] [20]. These agents possess pleiotropic properties including immunomodulation, anti-angiogenic, anti-inflammatory, and direct anti-proliferative effects [19]. Their discovery marked a shift toward targeting the tumor microenvironment and represented one of the most successful applications of phenotypic screening in oncology.

Mechanism of Action

IMiDs function by binding to a specific tri-tryptophan pocket of cereblon (CRBN), a substrate adaptor protein of the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [20]. This binding reconfigures the ligase's substrate specificity, leading to selective ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of key transcription factors, particularly Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3) [20]. Degradation of these targets mediates both direct anti-tumor effects through downregulation of IRF4 and c-MYC, and immunomodulatory effects including T-cell co-stimulation, enhanced NK cell activity, and inhibition of regulatory T-cells [19] [20].

Key Experimental Data on IMiD Potency

Table 3: Comparative Potency of Immunomodulatory Drugs

| Biological Effect | Thalidomide | Lenalidomide | Pomalidomide |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell Co-stimulation | + [19] | ++++ [19] | +++++ [19] |

| Inhibition of TNFα Production | + [19] | ++++ [19] | +++++ [19] |

| NK and NKT Cell Activation | + [19] | ++++ [19] | +++++ [19] |

| Anti-angiogenic Activity | ++++ [19] | +++ [19] | +++ [19] |

| Direct Anti-proliferative Activity | + [19] | +++ [19] | +++ [19] |

Experimental Protocols for IMiD Development

1. TNFα Inhibition Screening: Initial IMiD selection was based on potency in inhibiting TNFα production by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). IMiDs demonstrated 50-50,000-fold greater potency than thalidomide in these assays [19].

2. T-cell Co-stimulation Assays: Compounds were evaluated for their ability to stimulate T-cell proliferation in response to suboptimal T-cell receptor (TCR) activation. This co-stimulation was associated with enhanced phosphorylation of CD28 and activation of the PI3-K signaling pathway [19].

3. CRBN Binding and Neo-Substrate Degradation: Mechanistic studies utilized co-immunoprecipitation and western blotting to demonstrate IMiD-induced degradation of Ikaros and Aiolos. Resistance studies now routinely sequence CRBN and assess for abnormal splicing of exon 10, which prevents IMiD binding [20].

Comparative Analysis of Discovery Platforms

Screening Strategies and Lead Optimization

The three case studies exemplify distinct yet complementary approaches to drug discovery. Ivacaftor emerged from a target-based approach focused on correcting the function of a known protein, while risdiplam and IMiDs originated from phenotypic screening campaigns. Risdiplam's discovery involved screening for a specific molecular phenotype (increased exon 7 inclusion), whereas IMiDs were identified through functional phenotypic screening (immunomodulatory effects).

Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Targeting

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanistic pathways for each drug class:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Assay | Primary Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells | Ivacaftor development | In vitro model for CFTR function using Ussing chamber electrophysiology [14] |

| SMN2 Splicing Reporter Cell Lines | Risdiplam screening | High-throughput identification of compounds that promote exon 7 inclusion [16] |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | IMiD development | Ex vivo evaluation of immunomodulatory effects (TNFα inhibition, T-cell co-stimulation) [19] |

| 3D Spheroid/Organoid Cultures | Phenotypic screening | More physiologically relevant models for compound efficacy and toxicity testing [21] |

| Thermal Proteome Profiling | Target identification | System-wide mapping of drug-protein interactions and engagement [21] |

| RNA Sequencing | Mechanism of action studies | Transcriptional profiling to elucidate compound-induced changes [21] |

The case studies of ivacaftor, risdiplam, and IMiDs demonstrate the powerful synergy between phenotypic and target-based screening approaches in delivering transformative therapies. Ivacaftor exemplifies rational drug design targeting a specific protein defect, while risdiplam and IMiDs highlight how phenotypic screening can identify novel mechanisms that would be difficult to predict through target-based approaches alone. Advances in genomic profiling, bioinformatics, and cellular model systems continue to enhance both strategies, enabling more efficient identification of compounds with therapeutic potential. The integration of computational methods, such as the DrugReflector platform for phenotypic screening enrichment, promises to further accelerate this process by creating focused libraries tailored to disease-specific targets [13] [21]. These approaches collectively represent the evolving landscape of drug discovery, where understanding complex disease biology and employing appropriate screening methodologies leads to breakthrough therapies for previously untreatable conditions.

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action (MoA). By focusing on observable changes in disease-relevant models without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets, PDD has repeatedly expanded the boundaries of what is considered "druggable" [1]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for addressing diseases with complex biology and for targeting proteins that lack defined active sites, which have historically been intractable to traditional target-based drug discovery (TDD) [1] [22].

Between 1999 and 2008, a majority of first-in-class small-molecule drugs were discovered empirically through PDD approaches, demonstrating its significant impact on pharmaceutical innovation [1] [22]. The fundamental strength of PDD lies in its ability to identify compounds that modulate disease phenotypes through unprecedented biological mechanisms, including novel target classes and complex polypharmacology effects that would be difficult to rationally design [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of PDD-derived therapeutics, detailing their experimental validation and the unique biological space they occupy compared to target-based approaches.

PDD Successes in Expanding Druggable Targets

Phenotypic screening has enabled the therapeutic targeting of numerous protein classes and biological processes previously considered "undruggable." The table below summarizes key examples of novel mechanisms identified through PDD approaches.

Table 1: Novel Mechanisms and Targets Uncovered via Phenotypic Drug Discovery

| Therapeutic Area | Compound/Class | Novel Target/Mechanism | Biological Process Modulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | Daclatasvir (NS5A inhibitors) | HCV NS5A protein [1] | Viral replication complex formation [1] |

| Cystic Fibrosis (CF) | Ivacaftor (potentiator), Tezacaftor/Elexacaftor (correctors) | CFTR channel gating and cellular trafficking [1] [22] | Protein folding, membrane insertion, and ion channel function [1] |

| Multiple Myeloma | Lenalidomide/Pomalidomide | Cereblon E3 ubiquitin ligase [1] [2] | Targeted protein degradation (IKZF1/IKZF3) [1] [2] |

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | Risdiplam/Branaplam | SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing [1] | Stabilization of U1 snRNP complex and exon 7 inclusion [1] |

| Cancer/Multiple Indications | Imatinib (discovered via TDD but exhibits PDD-relevant polypharmacology) | BCR-ABL, c-KIT, PDGFR [1] | Multiple kinase inhibition contributing to clinical efficacy [1] |

These examples demonstrate how PDD has successfully targeted diverse biological processes, including viral replication complexes without enzymatic activity (NS5A), protein folding and trafficking (CFTR correctors), RNA splicing (SMN2 modulators), and targeted protein degradation (cereblon modulators) [1]. The clinical and commercial success of these therapies underscores the value of PDD in addressing previously inaccessible target space.

Benchmarking PDD Against Target-Based Approaches

Strategic and Outcomes Comparison

When evaluating drug discovery strategies, PDD and TDD present distinct advantages and challenges. The following table provides a comparative analysis of their key characteristics and documented outcomes.

Table 2: Strategic Comparison Between Phenotypic and Target-Based Drug Discovery

| Parameter | Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) | Target-Based Drug Discovery (TDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Disease phenotype or biomarker in realistic models [1] [8] | Pre-specified molecular target with hypothesized disease role [8] [2] |

| Target Requirement | Mechanism-agnostic; target identification follows compound validation [1] [2] | Requires known target and understanding of its disease relevance [2] |

| Success in First-in-Class | Higher proportion of first-in-class medicines [1] [22] | More effective for follower drugs with improved properties [22] |

| Novel Mechanism Potential | High - identifies unprecedented MoAs and targets [1] | Limited to known biology and predefined target space [1] |

| Clinical Attrition (AML case study) | Lower failure rates, particularly due to efficacy [23] | Higher failure rates in clinical development [23] |

| Key Challenges | Target deconvolution, hit validation [8] | Limited to druggable targets; may overlook complex biology [1] [2] |

Clinical Success Rates: Evidence from AML

A meta-analysis of 2918 clinical studies involving 466 unique drugs for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) provided evidence-based support for PDD's advantage in oncology drug discovery. The analysis revealed that PDD-based drugs fail less often due to a lack of efficacy compared to target-based approaches [23]. This real-world evidence underscores PDD's strength in identifying compounds with clinically relevant biological activity, particularly for complex diseases like cancer where multiple pathways and compensatory mechanisms often limit the effectiveness of single-target approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Phenotypic Screening Workflows

Modern phenotypic screening employs sophisticated experimental designs that capture disease complexity while maintaining suitability for drug discovery campaigns. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for phenotypic screening:

Diagram 1: Generalized Phenotypic Screening Workflow. This workflow highlights key stages from model system selection to target deconvolution, with examples of commonly used technologies and readouts.

Case Study: CAF Activation Assay Protocol

A recently developed phenotypic assay for cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) activation demonstrates the application of PDD principles in oncology research. This protocol aims to identify compounds that inhibit the formation of metastatic niches by blocking fibroblast activation [24].

Experimental Protocol:

Cell Co-culture Setup:

- Seed primary human lung fibroblasts in 96-well plates (5×10⁴ cells/well)

- Add highly invasive breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) and human monocytes (THP-1)

- Maintain in DMEM-F12/RPMI media with 10% FCS at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [24]

Phenotypic Readout Measurement:

- Fix cells and perform In-Cell ELISA (ICE) for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)

- Use anti-α-SMA primary antibody (1:1000 dilution)

- Apply fluorescent secondary antibody and quantify signal [24]

Validation Assay:

- Measure secreted osteopontin levels via ELISA

- Compare expression in co-culture vs. fibroblast-only controls [24]

Quality Control:

- Calculate Z′ factor to assess assay robustness (reported Z′=0.56)

- Use passages 2-5 fibroblasts to avoid spontaneous activation [24]

This assay successfully identified α-SMA as a robust biomarker for CAF activation, showing a 2.3-fold increase in expression when fibroblasts were co-cultured with cancer cells and monocytes [24]. The 96-well format enables medium-to high-throughput screening of compound libraries for metastatic prevention therapeutics.

Mechanism of Action Deconvolution Strategies

Following initial phenotypic hits, target deconvolution remains a critical challenge in PDD. The following diagram outlines common experimental approaches for mechanism elucidation:

Diagram 2: Target Deconvolution Approaches for PDD. Multiple experimental strategies are employed to identify molecular targets and mechanisms of action following phenotypic screening hits.

Advanced chemoproteomic platforms like the IMTAC (Isobaric Mass-Tagged Affinity Characterization) technology have emerged as powerful tools for target deconvolution. This approach uses covalent small molecule libraries screened against the entire proteome of live cells, enabling identification of engaging targets even for transient protein interactions and shallow binding pockets [7]. The platform has successfully identified small molecule ligands for over 4,000 proteins, approximately 75% of which lacked known ligands prior to discovery [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of PDD requires specialized reagents and tools designed to capture disease complexity while enabling high-quality screening. The following table details key solutions for phenotypic screening campaigns.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phenotypic Drug Discovery

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PDD | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cell Models | Human lung fibroblasts [24], Patient-derived immune cells | Maintain physiological relevance and disease context [8] [24] | Use early passages (2-5) to preserve native phenotypes [24] |

| Stem Cell Technologies | iPSC-derived lineages [8] | Disease modeling with genetic background control | Enable genetic engineering and scalable production |

| Co-culture Systems | Fibroblast/cancer cell/immune cell tri-cultures [24] | Recapitulate tumor microenvironment interactions | Require compartmentalization or marker-specific readouts |

| Bioimaging Tools | High-content imaging, Cell Painting [10] | Multiparametric morphological profiling | Generate rich datasets for AI/ML analysis |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics [2] | Mechanism elucidation and biomarker identification | Require integration with computational biology |

| Chemoproteomics | IMTAC platform, covalent libraries [7] | Target identification for phenotypic hits | Particularly valuable for "undruggable" targets |

| Computational Tools | DrugReflector AI, PhenoModel [13] [10] | Hit prediction and experimental prioritization | Use active learning to improve performance |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The PDD landscape is rapidly evolving with several technological innovations addressing historical challenges. Artificial intelligence and machine learning platforms are demonstrating significant potential in improving the efficiency of phenotypic screening. The DrugReflector framework, which uses active reinforcement learning to predict compounds that induce desired phenotypic changes, has shown an order of magnitude improvement in hit rates compared to random library screening [13]. Similarly, foundation models like PhenoModel effectively connect molecular structures with phenotypic information using dual-space contrastive learning, enabling better prediction of biologically active compounds [10].

Advanced chemoproteomics approaches are increasingly bridging the gap between phenotypic and target-based strategies. Platforms like IMTAC screen covalent small molecules against the entire proteome in live cells, simultaneously leveraging the benefits of PDD's phenotypic relevance and TDD's mechanistic clarity [7]. This integrated strategy has proven particularly valuable for targeting transient protein-protein interactions and shallow binding pockets that traditional approaches cannot address [7].

These technological advances, combined with more physiologically relevant model systems including microphysiological systems and organ-on-chip technologies, are positioning PDD to continue expanding the druggable genome and delivering first-in-class therapeutics for diseases with high unmet medical need [9].

In the field of drug discovery and phenotypic screening, the reliability of biological assays is paramount. High-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns, which can involve testing hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds, require assays that consistently generate high-quality, reproducible data [25]. A poorly performing assay can lead to wasted resources, false leads, and failed discovery projects. Consequently, researchers employ statistical parameters to quantitatively assess and validate assay performance prior to initiating large-scale screens [26] [27]. Among these, the Z'-factor (Z-prime factor) has emerged as a cornerstone metric for evaluating assay robustness. It serves as a standardized, unitless measure that captures both the dynamic range of the assay signal and the data variation associated with control samples [25] [28]. By applying this metric, scientists can make informed, data-driven decisions about the suitability of an assay for a screening campaign, thereby increasing the likelihood of identifying genuine hits [27].

Understanding and Calculating the Z'-factor

Definition and Formula

The Z'-factor is a statistical parameter used to assess the quality of an assay by comparing the signal characteristics of positive and negative controls. This comparison is made without the inclusion of test samples, making it an ideal tool for assay development and validation prior to full-scale screening [28]. The standard definition of the Z'-factor is:

Z'-factor = 1 - [3(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|]

In this equation:

- μp and μn are the sample means of the positive and negative controls, respectively.

- σp and σn are the sample standard deviations of the positive and negative controls, respectively [25].

The Z'-factor essentially quantifies the separation band between the positive and negative control populations, taking into account their variability. A larger separation and smaller variability result in a higher Z'-factor, indicating a more robust assay [25] [26].

Interpretation of Z'-factor Values

The value of the Z'-factor falls within a theoretical range of -∞ to 1. Based on established guidelines, the assay quality can be categorized as follows [25] [26]:

Table 1: Interpretation of Z'-factor Values

| Z'-factor Value | Assay Quality Assessment | Suitability for Screening |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Ideal assay (theoretical maximum) | Theoretical ideal, not achieved in practice |

| 0.5 to 1.0 | Excellent to good assay | Suitable for high-throughput screening (HTS) |

| 0 to 0.5 | Marginal or "yes/no" type assay | May be acceptable depending on context; unsuitable for HTS |

| < 0 | Poor assay, significant overlap between controls | Screening essentially impossible |

An assay with a Z'-factor greater than 0.5 is generally considered to have sufficient robustness for HTS applications. This threshold implies a clear separation between controls, with the means of the two populations being separated by at least 12 standard deviations if their variances are equal [25]. However, a more nuanced approach is sometimes necessary, particularly for complex cell-based assays where inherent biological variability can make achieving a Z' > 0.5 challenging [29] [28].

Figure 1: The Z'-factor Calculation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the step-by-step process of calculating and interpreting the Z'-factor, from inputting control data to assessing final assay robustness.

Z'-factor in the Context of Other Assay Metrics

Comparison with Related Z-Statistics

The Z'-factor is part of a family of Z-statistics. A closely related metric is the Z-factor (Z), which is used to evaluate assay performance during or after screening, as it incorporates data from test samples [28]. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Z'-factor and Z-factor

| Parameter | Z'-factor (Z') | Z-factor (Z) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Used | Positive and negative controls only [28] | Test samples and a control (e.g., negative control) [25] |

| Purpose | Assess the inherent quality and robustness of the assay platform [28] | Evaluate the actual performance of the assay during screening with test compounds [28] |

| Typical Use Case | Assay development, validation, and optimization [28] | Quality control during or after a high-throughput screen [25] |

| Formula | 1 - [3(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|] [25] | 1 - [3(σs + σc) / |μs - μc|] (where 's' is sample, 'c' is control) [25] |

In practice, for a well-developed assay and a screening library with a low hit rate, the Z-factor should be less than or equal to the Z'-factor, confirming that the assay performs as expected with test compounds [28].

Comparison with Other Common Assay Metrics

Beyond Z-statistics, other metrics are used to characterize assay performance. The Z'-factor is often evaluated alongside them to provide a comprehensive picture.

Table 3: Key Assay Performance Metrics Beyond Z'-factor

| Metric | Definition | Relationship to Z'-factor |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) | Ratio of the signal from a positive control to the signal from a negative control [26]. | A high S/B is necessary for a good Z'-factor, but Z' also penalizes high data variation [26]. |

| EC50 / IC50 | The concentration of a compound that produces 50% of its maximal effective (EC50) or inhibitory (IC50) response [26]. | Measures compound potency; an assay with a good Z' ensures reliable EC50/IC50 determination. |

| Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) | An alternative robustness parameter that is more robust to outliers and is mathematically more convenient for statistical inference [25]. | Proposed to address some limitations of Z', particularly with non-normal data or multiple positive controls [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Z'-factor

Standard Protocol for Z'-factor Calculation

The following protocol outlines the general steps for determining the Z'-factor of a cell-based assay, such as a gene reporter assay used in phenotypic screening.

- Plate Design: Seed cells in a microplate (e.g., 96 or 384-well). Designate a sufficient number of wells (e.g., n≥16-24 per control) for positive controls (e.g., cells treated with a known agonist or a maximal stimulus) and negative controls (e.g., untreated cells or cells treated with a vehicle like DMSO) [26] [27].

- Assay Execution: Treat the control wells according to the established protocol. For a luciferase reporter assay, this would involve adding the respective controls, incubating for the required time, and then adding the detection reagent (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) before measuring luminescence [26] [28].

- Data Collection: Read the assay signal (e.g., Relative Light Units (RLU) for luminescence) using an appropriate detector, ideally a microplate reader known for high sensitivity and low noise to minimize instrumental variability [28].

- Calculation: For each control group, calculate the mean (μp and μn) and standard deviation (σp and σn) of the measured signals. Input these values into the Z'-factor formula [25].

- Interpretation: Assess the calculated Z'-factor against the accepted thresholds (Table 1) to determine if the assay is robust enough for its intended purpose.

Advanced Adaptation: Robust Z'-factor

A recognized limitation of the standard Z'-factor is its sensitivity to outliers, as it relies on non-robust statistics (mean and standard deviation) [25]. This is particularly problematic in complex biological systems like primary neuronal cultures, where data may not follow a normal distribution [29].

To address this, a Robust Z'-factor has been developed. It substitutes the mean with the median and the standard deviation with the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) [25] [29]. The MAD is scaled by a constant (typically 1.4826) to be consistent with the standard deviation for normally distributed data.

Protocol for Robust Z'-factor:

- Follow the same experimental steps (1-3) as the standard protocol.

- Data Transformation: If necessary, apply a transformation (e.g., log transformation) to the raw data to better approximate a normal distribution [29].

- Robust Calculation:

- Calculate the median of the positive control signals (Medp) and the negative control signals (Medn).

- Calculate the MAD for both controls (MADp and MADn).

- Use these values in the adapted formula: Robust Z'-factor = 1 - [3(1.4826 × MADp + 1.4826 × MADn) / |Medp - Medn|] [29].

This method has been successfully applied in complex assays, such as those using adult dorsal root ganglion neurons on microelectrode arrays, where it demonstrated reduced sensitivity to data variation and provided a more reliable quality assessment [29].

Figure 2: Relationship Between Z'-factor and Other Key Metrics. This diagram shows how Z'-factor is derived from fundamental parameters like signal and variation, and how it relates to other important assay metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials commonly used in experiments designed to determine the Z'-factor for cell-based phenotypic screening assays.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Z'-factor Determination

| Item | Function in Assay Development & Z' Calculation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines (Engineered) | Engineered to contain the target of interest (e.g., a specific receptor) and a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase). Provide the biological system for the assay. | GPCR activation studies, pathway modulation assays [28]. |

| Positive/Negative Control Compounds | Define the assay's dynamic range. The positive control induces a maximal response; the negative control (e.g., vehicle) defines the baseline signal. | A known agonist for a receptor; DMSO vehicle control [26] [28]. |

| Reporter Assay Detection Kits | Provide optimized reagents to measure the output signal of the reporter gene (e.g., luciferase) accurately and sensitively. | Luciferase-based gene reporter assays, HTRF assays [26] [28]. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits | Used to monitor cytotoxicity, which can be a confounder in phenotypic screens. Can be used as a counter-screen or to normalize data. | CellTiter-Glo, MTT, resazurin assays [28]. |

| Microplate Readers | Instrumentation for detecting the assay signal (e.g., luminescence, fluorescence). High sensitivity and low noise are critical for achieving a high Z'-factor. | Luminescence detection for reporter assays, fluorescence for FRET/HTRF assays [28]. |

| Automation & Liquid Handling Systems | Ensure precision and reproducibility in reagent dispensing, which reduces well-to-well variability and improves the standard deviation component of the Z'-factor. | High-throughput screening in 384-well or 1536-well formats [27]. |

Advanced Tools and Workflows: Implementing High-Content and AI-Driven Screens

High Content Screening (HCS) generates rich, high-dimensional cellular image data, transforming the ability to profile cellular responses to genetic and chemical perturbations [30]. However, the adoption of advanced representation learning methods for this data has been hampered by the lack of accessible, standardized datasets and robust benchmarks [31]. The RxRx3-core dataset, a curated and compressed 18GB subset of the larger RxRx3 dataset, is specifically designed to fill this gap, providing a practical resource for benchmarking models on tasks like zero-shot drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction directly from microscopy images [30] [32]. This guide objectively compares its performance against alternative methods and datasets, providing experimental data to inform researchers in the field.

RxRx3-core addresses critical limitations in existing HCS resources. While large-scale datasets like the full RxRx3 and JUMP exist, their sheer size (over 100 TB each) creates a significant barrier to entry for most researchers [31]. Previous benchmarking efforts, such as those using the CPJUMP1 dataset, suffered from experimental confounders like non-randomized well positions between technical replicates [31]. Other frameworks, like the Motive dataset, frame DTI prediction as a graph learning task on pre-extracted image features rather than a benchmark for evaluating representation learning directly from pixels [31].

In contrast, RxRx3-core provides a compact dataset of 222,601 six-channel fluorescent microscopy images from human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), stained with a modified Cell Painting protocol [31] [32]. It spans 736 CRISPR knockouts and 1,674 compounds tested at 8 concentrations each, preserving the data structure necessary for rigorous benchmarking while being small enough for widespread use [30] [32]. Its associated benchmarks are designed to evaluate how well machine learning models can capture biologically meaningful signals, focusing on perturbation signal magnitude and zero-shot prediction of drug-target and gene-gene interactions [33].

Dataset Comparison: RxRx3-core vs. Alternatives

The table below compares RxRx3-core with other prominent datasets used for HCS image analysis, highlighting its unique position as an accessible benchmarking tool.

Table 1: Comparison of HCS Imaging Datasets for Benchmarking

| Dataset | Primary Purpose | Image Data Volume | Perturbations | Key Strengths | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RxRx3-core [31] [32] | Benchmarking representation learning & zero-shot DTI | 18 GB (images) | 736 genes, 1,674 compounds (8 conc.) | Managesable size; curated for benchmarking; includes pre-computed embeddings; no plate confounders. | Subset of full genome; compressed images. |

| Full RxRx3 [31] [34] | Large-scale phenomic screening | >100 TB | 17,063 genes, 1,674 compounds (8 conc.) | Extensive genetic coverage; high-resolution images. | Prohibitive size for most labs; majority of metadata was blinded. |

| JUMP [31] | Large-scale phenomic screening | >100 TB | ~11,000 genes, ~3,600 compounds | Broad genetic and compound coverage. | Prohibitive size for benchmarking. |

| CPJUMP1 [31] | Benchmarking DTI prediction | Not specified in results | 302 compounds, 160 genes | Designed for DTI task. | Plate layout confounders; limited number of perturbations. |

| Motive [31] | Graph learning for DTI | Uses pre-computed CellProfiler features from JUMP | ~11,000 genes, ~3,600 compounds | Leverages large-scale public annotations. | Does not benchmark learning from raw images; requires feature extraction. |

Performance Comparison of Representation Learning Methods

The core benchmarking utility of RxRx3-core is demonstrated by evaluating different representation learning methods on its data. The following table summarizes the performance of two proprietary models (Phenom-1, Phenom-2), one public model (OpenPhenom-S/16), and a traditional image analysis method (CellProfiler) on the RxRx3-core benchmarks [33].

Table 2: Model Performance on RxRx3-core Benchmarks

| Representation Learning Method | Model Architecture | Perturbation Signal (Energy Distance) | DTI Prediction (Median AUC) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellProfiler [33] | Manual feature extraction pipeline | Lower | Lower | Traditional features are less effective at capturing compound-gene activity. |

| OpenPhenom-S/16 [33] | ViT-S/16 (MAE), channel-agnostic | Medium | Medium | Publicly available model offering a strong open-source baseline. |

| Phenom-1 [33] | ViT-L/8 (MAE), proprietary | High | High | Scaling model size with proprietary data improves performance. |

| Phenom-2 [33] | ViT-G/8 (MAE), proprietary | Highest | Highest | Largest model achieved best performance, highlighting the importance of scale in self-supervised learning for biology. |

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking

The benchmarking process on RxRx3-core involves a standardized workflow to ensure fair and reproducible evaluation of different models [33]:

- Embedding Generation: For each image in the dataset, a feature vector (embedding) is generated using the model being evaluated. For foundation models like OpenPhenom-S/16, this is the output of the vision transformer encoder. For CellProfiler, it is a 952-dimensional vector of hand-crafted features per cell, which are then aggregated per image [33].

- Aggregation and Batch Alignment: The tile-level embeddings for each image are mean-aggregated to produce a single embedding per well. A critical step called PCA-CS (Principal Component Analysis with Centering and Scaling) is then applied. This batch alignment technique centers the latent space on control samples and aligns embeddings across different experimental batches to correct for technical noise [33].

- Benchmark Scoring:

- Perturbation Signal Benchmark: This measures the strength of a perturbation's phenotypic signal. For each perturbation (gene knockout or compound), the energy distance is computed between the distribution of its replicate embeddings and the distribution of negative control embeddings. A higher energy distance indicates a stronger and more detectable perturbation signal [33].

- Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Benchmark: This evaluates the model's ability to predict known drug-target pairs. Embeddings for compounds and gene knockouts are compared using cosine similarity. The benchmark tests if known interactions, curated from public databases, have higher similarity scores than non-interacting pairs. Performance is reported as the median Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Average Precision across all evaluated targets [33].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful experimentation in this domain, as demonstrated by the RxRx3-core benchmarks, relies on a suite of wet-lab reagents and computational tools. The table below details key components.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HCS Benchmarking

| Item Name | Category | Function in HCS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| HUVEC Cells [34] | Cell Line | Primary human cell type used in RxRx3-core; provides a biologically relevant system for assessing perturbations. |

| Modified Cell Painting Protocol [31] | Staining Kit | A set of fluorescent dyes that label multiple cellular compartments (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm, Golgi), generating rich morphological data. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Reagents [31] | Genetic Tool | Enables targeted knockout of specific genes (736 in RxRx3-core) to study loss-of-function phenotypes. |

| Bioactive Compound Library [31] [34] | Chemical Library | A collection of 1,674 small molecules used to perturb cellular state and probe for phenotypic changes. |

| OMERO [35] | Data Management Platform | Open-source platform for managing, visualizing, and analyzing large biological image datasets; crucial for handling HCS data. |

| CellProfiler [31] [33] | Image Analysis Software | Open-source tool for automated image analysis, including cell segmentation and feature extraction; used for traditional analysis pipelines. |

| Workflow Management Systems (Galaxy, KNIME) [35] | Computational Tool | Platforms for creating reproducible, semi-automated data analysis and management workflows, improving consistency and efficiency. |

Technical Insights from RxRx3-core Implementation

The creation of RxRx3-core itself involved a sophisticated data compression pipeline to make the dataset accessible without sacrificing its scientific utility. The process also highlights the shift from traditional feature extraction to self-supervised learning for biological image analysis.

Key Technical Findings