Benchmarking NGS Platforms for Chemogenomic Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Toxicology and Drug Development

Error-corrected next-generation sequencing (ecNGS) has revolutionized the direct evaluation of genome-wide mutations following exposure to mutagens, enabling high-resolution detection of chemical-induced genetic alterations.

Benchmarking NGS Platforms for Chemogenomic Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Precision Toxicology and Drug Development

Abstract

Error-corrected next-generation sequencing (ecNGS) has revolutionized the direct evaluation of genome-wide mutations following exposure to mutagens, enabling high-resolution detection of chemical-induced genetic alterations. This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of contemporary NGS platforms—including Illumina, MGI, Oxford Nanopore, and PacBio systems—for chemogenomic applications. We explore the foundational principles of sequencing-induced error profiles, detail methodological workflows for robust assay design, and present optimization strategies to enhance sensitivity and specificity. Through comparative validation of platform performance using standardized mutagenesis models, we offer actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals to select appropriate technologies, optimize protocols, and accurately interpret mutation spectra for reliable mutagenicity assessment and safety profiling.

Understanding NGS Technology Landscapes and Their Impact on Mutation Detection in Chemogenomics

The evolution of DNA sequencing technologies has fundamentally transformed biological research and clinical diagnostics. From its beginnings with the Sanger method to today's third-generation platforms, each technological leap has expanded our ability to decipher genetic information with increasing speed, accuracy, and affordability. This progression is particularly relevant for chemogenomic sensitivity research, where understanding the genetic determinants of drug response requires comprehensive genomic analysis. The migration from first-generation Sanger sequencing to next-generation sequencing (NGS) and third-generation sequencing (TGS) has enabled researchers to move from analyzing single genes to entire genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes in a single experiment, providing unprecedented insights into the complex interactions between chemicals and biological systems [1] [2].

This guide provides an objective comparison of sequencing platforms across generations, focusing on performance metrics critical for chemogenomic applications. We present experimental data from controlled benchmarking studies and detail methodologies to assist researchers in selecting appropriate sequencing technologies for their specific sensitivity research needs.

Sequencing Technology Generations: Core Principles and Platforms

First-Generation Sequencing: Sanger Method

The chain-termination method developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977 established the foundation for modern genomics [1]. This technique utilizes dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) to terminate DNA synthesis at specific bases, followed by separation via capillary electrophoresis to determine the sequence. For years, Sanger sequencing represented the gold standard for accuracy, achieving >99.99% precision for individual DNA fragments [3]. However, its low throughput, high cost per base, and time-consuming nature limited its application for large-scale projects like genome-wide association studies now common in chemogenomics research.

Second-Generation Sequencing (NGS): High-Throughput Parallelism

Next-generation sequencing technologies revolutionized genomics by implementing massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [1]. This approach dramatically reduced costs and increased throughput compared to Sanger sequencing. Key NGS platforms include:

- Illumina: Utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators bridge amplification on solid surfaces [1]. Platforms range from the benchtop MiSeq to the high-throughput NovaSeq X series, which can sequence up to 20,000 genomes per year [2].

- Ion Torrent (Thermo Fisher): Employs semiconductor technology that detects hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization, without requiring optical detection systems [1].

- MGI DNBSEQ: Uses DNA nanoball technology and combinatorial probe anchor polymerization (cPAS) for sequencing [4].

NGS platforms generate short reads (typically 50-300 bp) with high accuracy (≥99.9%), making them suitable for a wide range of applications including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics, and targeted gene panels for mutation discovery in chemogenomic studies [1] [5].

Third-Generation Sequencing (TGS): Single-Molecule Real-Time Sequencing

Third-generation sequencing technologies overcome a fundamental limitation of NGS by sequencing single DNA molecules in real-time without prior amplification, producing long reads that can span repetitive regions and structural variants [6]. Major TGS platforms include:

- Pacific Biosciences (PacBio): Implements single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing using zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) to monitor DNA polymerase activity in real-time [6]. The technology offers two modes: Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) for high accuracy (>99.9%) and Continuous Long Read (CLR) for maximum read length.

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT): Measures changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [6] [7]. This platform offers remarkable portability, with devices ranging from pocket-sized MinION to high-throughput PromethION systems.

TGS platforms routinely generate reads exceeding 10,000 base pairs, with Nanopore technology capable of sequencing fragments up to hundreds of kilobases [7]. This advantage is particularly valuable for resolving complex genomic regions relevant to drug metabolism and resistance studies.

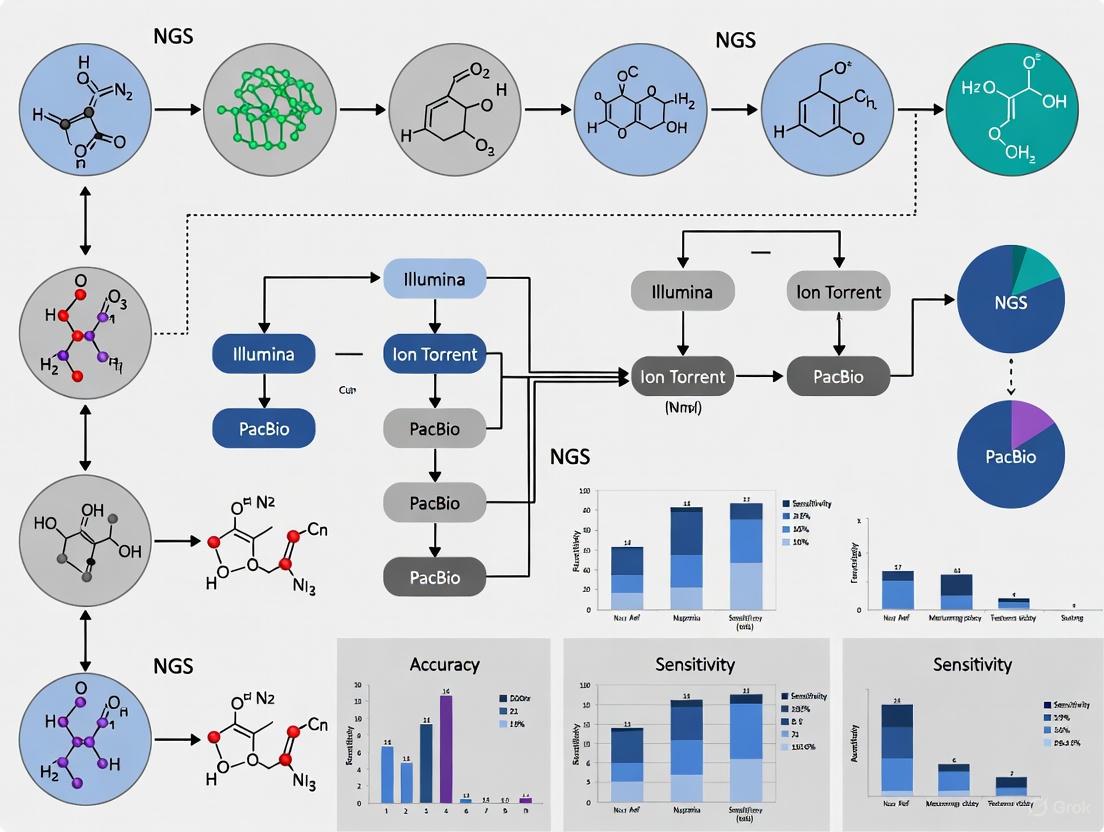

Figure 1: Evolution of sequencing technology generations from Sanger to emerging platforms. Each generation introduced fundamental changes in sequencing chemistry and throughput.

Performance Benchmarking: Comparative Experimental Data

Platform Performance Metrics

Multiple studies have directly compared sequencing platforms using standardized samples and metrics relevant to chemogenomic research. The following tables summarize key performance characteristics across platforms.

Table 1: Sequencing platform specifications and performance characteristics

| Platform | Read Length | Accuracy | Throughput per Run | Run Time | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger | 400-900 bp | >99.99% | 96-384 reads | 0.5-3 hours | Gold standard accuracy, simple analysis | Low throughput, high cost/base |

| Illumina | 50-300 bp | ≥99.9% | 10 Gb-6 Tb | 1-6 days | High throughput, low error rate | Short reads, GC bias, amplification artifacts |

| Ion Torrent | 200-400 bp | ≥99.9% | 80 Mb-15 Gb | 2-24 hours | Fast runs, no optical detection | Homopolymer errors, moderate throughput |

| MGI DNBSEQ | 50-300 bp | ≥99.9% | 8-180 Gb | 1-6 days | Lower cost alternative | Similar limitations to Illumina |

| PacBio | 10-25 kb (CLR); 1-3 kb (HiFi) | >99.9% (HiFi) | 5-500 Gb | 0.5-30 hours | Long reads, epigenetic detection | Higher DNA requirements, cost |

| Oxford Nanopore | 10 kb->100 kb | 95-99% (Q20+ available) | 10-280 Gb | 0.5-72 hours | Ultra-long reads, portability, real-time | Higher raw error rate (improving) |

Table 2: Performance comparison in microbial metagenomics study using complex synthetic communities (71-87 strains) [4]

| Platform | Reads Uniquely Mapped | Substitution Error Rate | Indel Error Rate | Assembly Contiguity (N50) | Genomes Fully Recovered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina HiSeq 3000 | ~95% | Very Low | Very Low | Moderate | 15/71 |

| Ion Torrent S5 | ~87% | Low | Low | Moderate | 12/71 |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T7 | ~96% | Very Low | Very Low | Moderate | 16/71 |

| PacBio Sequel II | ~99% | Lowest | Moderate | Highest | 36/71 |

| ONT MinION | ~99% | Moderate | Highest | High | 22/71 |

Accuracy and Error Profiles Across Platforms

Different sequencing technologies exhibit distinct error profiles that significantly impact their application in chemogenomic sensitivity research:

- Sanger sequencing demonstrates the highest accuracy but is limited to low-throughput applications [3].

- Illumina platforms show exceptionally low error rates (<0.1%) dominated by substitution errors, making them ideal for variant calling in pharmacogenomic studies [1] [5].

- Ion Torrent exhibits higher rates of indel errors, particularly in homopolymer regions, which can challenge interpretation of repetitive genomic regions [1].

- PacBio HiFi reads achieve >99.9% accuracy through circular consensus sequencing, providing both long reads and high accuracy for resolving complex gene families like cytochrome P450 enzymes relevant to drug metabolism [6].

- Oxford Nanopore has historically shown higher error rates (95-98% raw accuracy) but recent improvements (Q20+ chemistry) achieve >99% accuracy, with errors predominantly comprising indels in homopolymer regions [5] [7].

Limit of Detection for Pathogen Identification

For chemogenomic applications involving infectious diseases or microbiome interactions, the limit of detection (LoD) is a critical parameter. A comparative study evaluated three NGS platforms for detecting viral pathogens in blood samples [8]:

- Roche 454 Titanium: Detected Dengue virus at titers as low as 1X10^2.5 pfu/mL, with 31% genome coverage at this LoD

- Illumina MiSeq and Ion Torrent PGM: Demonstrated similar sensitivity, detecting viral genomes at concentrations as low as 1X10^4 genome copies/mL

- All platforms: Showed analytical sensitivity approaching standard qPCR assays, with the MiSeq platform providing the greatest depth and breadth of coverage for bacterial pathogen identification (Bacillus anthracis)

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

Benchmarking Study Design

To ensure meaningful comparisons across sequencing platforms, researchers should implement standardized experimental designs:

Mock Community Construction:

- Create synthetic microbial communities with known composition (64-87 strains) spanning diverse phylogenetic groups [4]

- Include strains with varying GC content (27-69%) and genome sizes (0.49-9.7 Mbp) to assess platform biases

- Spike in known concentrations of pathogens (e.g., Dengue virus, Influenza H1N1) in biological matrices like blood to determine limits of detection [8]

Standardized Metrics for Comparison:

- Sequencing accuracy: Calculate substitution, insertion, and deletion error rates by alignment to reference genomes

- Mapping rates: Determine percentage of reads uniquely mapping to reference sequences

- Coverage uniformity: Assess GC bias by correlating sequencing depth with genomic GC content

- Variant calling performance: Evaluate sensitivity and specificity for SNVs, indels, and structural variants using known variants in reference materials

- Assembly quality: Compare contiguity (N50), completeness, and accuracy of de novo assemblies [5]

Protocol for Metagenomic Sequencing Comparison

A comprehensive benchmarking study compared seven sequencing platforms (five second-generation and two third-generation) using synthetic microbial communities [4]. The detailed methodology included:

Sample Preparation:

- DNA Extraction: Use standardized extraction protocols across all samples to minimize bias

- Library Preparation:

- For Illumina: Nextera XT DNA library prep with dual indexing

- For Ion Torrent: Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit with emulsion PCR

- For PacBio: SMRTbell library preparation with size selection (>10 kb)

- For Nanopore: Ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109) without PCR amplification

- Quality Control: Quantify libraries using fluorometric methods and validate fragment size distribution

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequencing: Process libraries according to manufacturer recommendations for each platform

- Read Processing: Perform platform-specific quality filtering and adapter removal

- Read Mapping: Align reads to reference genomes using appropriate mappers (BWA-MEM for short reads, minimap2 for long reads)

- Taxonomic Profiling: Calculate relative abundances and compare to expected composition

- Assembly Evaluation: Perform de novo assembly using recommended tools for each data type (SPAdes for short reads, Flye for long reads)

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for comprehensive sequencing platform benchmarking. The standardized approach enables direct comparison across technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions for sequencing platform comparisons

| Category | Specific Products/Kits | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | ATCC MSA-1002 (20 Strain Even Mix), ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards | Provides known composition for accuracy assessment | Essential for determining platform-specific biases in metagenomic studies |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | High-quality DNA extraction with minimal bias | Critical for accurate representation of microbial communities; use consistent across platforms |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina Nextera XT, Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit, PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit, ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | Platform-specific library construction | Follow manufacturer recommendations; consider PCR-free protocols to avoid amplification bias |

| Quality Control Tools | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Agilent Fragment Analyzer, Quant-iT Broad-Range dsDNA Assay | Accurate quantification and size distribution | Essential for normalizing input across platforms; fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, MGI DNBSEQ-T7, Ion GeneStudio S5, PacBio Sequel II, ONT PromethION | DNA sequencing | Select based on required read length, throughput, and application needs |

| Bioinformatics Tools | FastQC, BWA-MEM, minimap2, SPAdes, Flye, Canu | Data quality control, alignment, and assembly | Use standardized versions and parameters for cross-platform comparisons |

Implications for Chemogenomic Sensitivity Research

The selection of sequencing technology directly impacts the quality and scope of chemogenomic research. Each platform offers distinct advantages for specific applications:

- Illumina platforms remain the gold standard for variant calling studies due to their high accuracy and throughput, ideal for genome-wide association studies of drug response [1] [2].

- PacBio HiFi reads excel in resolving complex genomic regions, including highly homologous gene families like CYP450 enzymes, which play crucial roles in drug metabolism [6].

- Oxford Nanopore provides unique capabilities for real-time sequencing and direct detection of epigenetic modifications, which may influence gene expression in response to chemical exposures [6] [7].

- Hybrid approaches combining short-read and long-read technologies have proven effective for generating complete, high-quality genomes, as demonstrated in yeast genome assembly studies [5].

For comprehensive chemogenomic profiling, researchers should consider integrating multiple sequencing technologies to leverage their complementary strengths—using short-read platforms for high-confidence variant detection and long-read technologies for resolving structural variants and haplotypes.

The evolution from Sanger to third-generation sequencing platforms has dramatically expanded our capabilities for genomic research, each generation offering distinct advantages for specific applications. Performance benchmarking demonstrates that platform selection involves trade-offs between read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost. For chemogenomic sensitivity research, there is no universal "best" platform—rather, the optimal choice depends on the specific research questions, sample types, and analytical requirements.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance, with improvements in accuracy, read length, and accessibility, their application in chemogenomics will further illuminate the genetic determinants of drug response. The experimental frameworks and comparative data presented in this guide provide researchers with evidence-based resources for selecting and implementing appropriate sequencing technologies for their chemogenomic studies.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have become fundamental to modern genomics, driving advances in disease research, drug discovery, and molecular biology. The performance of any genomic study is intrinsically linked to the choice of sequencing chemistry, each with distinct strengths and limitations in accuracy, throughput, read length, and application suitability. This guide provides a objective comparison of three core sequencing chemistries: Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), Ion Semiconductor Sequencing, and Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing. Framed within the context of benchmarking NGS platforms for chemogenomic sensitivity research, this analysis equips researchers and drug development professionals with the data necessary to select the optimal technology for their specific experimental needs, particularly in profiling complex genomes and detecting genomic variations with high precision.

The principle of "sequencing by synthesis" is shared across major NGS platforms, but the underlying biochemical and detection methods differ significantly, influencing their performance profiles.

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS): Utilized by Illumina platforms, SBS employs reversible dye-terminator chemistry. During each cycle, fluorescently labeled nucleotides are added to a growing DNA strand by a polymerase. After imaging to identify the incorporated base, the fluorescent dye and terminal blocker are enzymatically cleaved, preparing the strand for the next incorporation cycle [9]. This cyclic process occurs across millions of clusters on a flow cell in a massively parallel manner, generating high-throughput data. A key advantage is the virtual elimination of errors in homopolymer regions, a limitation of other technologies [9].

Ion Semiconductor Sequencing: This method, employed by Ion Torrent systems, is based on the detection of hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization. When a nucleotide is incorporated into the DNA strand, a hydrogen ion is released, causing a slight pH change detected by a semiconductor sensor [10]. A distinguishing feature is that it does not require optical imaging or modified nucleotides, which can streamline the workflow. However, it can be prone to errors in accurately calling the length of homopolymer sequences due to the proportional but sometimes difficult-to-resolve signal intensity [11] [10].

Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing: Developed by Pacific Biosciences, SMRT sequencing takes a fundamentally different approach. It observes DNA synthesis in real-time as a single DNA polymerase molecule incorporates fluorescently labeled nucleotides into a template immobilized at the bottom of a nanophotonic structure called a zero-mode waveguide [12]. The key differentiator is the read length; since the template is not amplified and the polymerase is processive, SMRT sequencing produces long reads averaging thousands of base pairs, with some reads exceeding 20,000 bp [12]. This makes it exceptionally powerful for de novo genome assembly, resolving complex structural variations, and detecting epigenetic modifications through native polymerase kinetics analysis [12].

Figure 1. Comparative workflows of the three core sequencing chemistries. SBS relies on cyclic reversible termination and imaging. Ion Semiconductor sequencing detects hydrogen ion release during nucleotide incorporation. SMRT sequencing directly observes single-molecule synthesis in real time. ZMW: Zero-Mode Waveguide.

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Data

Direct performance comparisons reveal technology-specific profiles that determine suitability for various applications. The following table summarizes key performance metrics as established in controlled studies.

Table 1. Quantitative Performance Comparison of Core Sequencing Chemistries

| Performance Metric | SBS (Illumina) | Ion Semiconductor (Ion Torrent) | SMRT (PacBio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [9] | ~99.0% [10] | ~90% for single pass [12] |

| Consensus Accuracy | N/A (Inherently high) | N/A (Inherently high) | >99.999% (with ~8x coverage) [12] |

| Read Length | 2x 300 bp (MiSeq) [13] | Up to 400 bp [10] | 3,000 bp average; up to 20,000+ bp [12] |

| Throughput per Run | 540 Gb (NextSeq 2000) to 8 Tb (NovaSeq X) [13] | ~10 Gb (Ion PGM) to ~50 Gb (Ion S5) [14] [10] | ~0.5 - 5 Gb per SMRT Cell [12] |

| Homopolymer Error | Very Low [9] | High [11] [10] | Low (post-consensus) [12] |

| Run Time | ~8-44 hours (NextSeq 2000) [13] | ~2-7 hours [10] | ~30 minutes - 4 hours [12] |

| Variant Detection | Excellent for SNPs/Indels [15] | Good for SNPs, lower indel fidelity [11] | Excellent for Structural Variants [12] |

| Epigenetic Detection | Requires bisulfite conversion | No native detection | Direct detection of base modifications [12] |

A 2014 comparative study of 16S rRNA bacterial community profiling highlighted specific performance disparities. The Ion Torrent platform exhibited organism-specific biases and a pattern of premature sequence truncation, which could be mitigated by optimized flow orders and bidirectional sequencing. While both Illumina and Ion Torrent platforms generally produced concordant community profiles, disparities arose from the failure to generate full-length reads for certain organisms and organism-dependent differences in sequence error rates on the Ion Torrent platform [11].

For single-cell transcriptomics (scRNA-seq), a 2024 study found that Illumina SBS and MGI's DNBSEQ (which also employs a form of SBS) performed similarly. DNBSEQ exhibited mildly superior sequence quality, evidenced by higher Phred scores, lower read duplication rates, and a greater number of genes mapping to the reference genome. However, these technical differences did not translate into meaningful analytical disparities in downstream single-cell analysis, including gene detection, cell type annotation, or differential expression analysis [16].

SMRT sequencing's performance is defined by its long reads and random error profile. While individual reads have a high error rate (approximately 11-14%), these errors are stochastic and not systematic. With sufficient depth (recommended ≥8x coverage), a highly accurate consensus sequence can be generated with >99.999% accuracy, as it is highly unlikely for the same error to occur randomly at the same genomic position multiple times [12]. This makes SMRT sequencing a powerful tool for de novo genome assembly and resolving complex regions.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of platform comparisons, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are adapted from key comparative studies.

Protocol 1: 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing for Microbiome Profiling

This protocol is designed to evaluate platform performance in differentiating complex microbial communities and identifying potential sequence-dependent biases [11].

- Step 1: Library Preparation. Use a defined 20-organism mock bacterial community as a control. Amplify the hypervariable V1-V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers. Purify the resulting amplicons.

- Step 2: Platform-Specific Library Construction. Prepare sequencing libraries according to the manufacturer's protocols for both Illumina (e.g., MiSeq) and Ion Torrent (e.g., PGM) platforms. For Ion Torrent, employ bidirectional amplicon sequencing and the optimized flow order to minimize read truncation artifacts.

- Step 3: Sequencing and Data Processing. Sequence libraries on both platforms. Process raw data through a standardized bioinformatics pipeline: demultiplexing, quality filtering (Q-score ≥30 for Illumina), and clustering of sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at 97% similarity.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. Compare the following outcomes:

- Observed richness: The number of distinct OTUs identified from the mock community.

- Taxonomic composition: Accuracy in recapitulating the known composition of the mock community.

- Beta-diversity: Concordance in community profiles generated from the same biological samples across the two platforms.

Protocol 2: scRNA-Seq Library Sequencing for Transcriptome Complexity

This protocol assesses the ability of different platforms to capture the full complexity of single-cell transcriptomes, including sensitivity in detecting lowly expressed genes [16].

- Step 1: Library Generation. Generate single-cell RNA-seq libraries from a well-characterized cell line or primary tissue (e.g., mouse brain) using a standardized droplet-based method (e.g., 10x Genomics).

- Step 2: Library Splitting and Sequencing. Split a single, pooled scRNA-seq library into aliquots. Sequence these technical replicates on the platforms being compared (e.g., Illumina SBS and DNBSEQ).

- Step 3: Bioinformatic Processing. Align reads to the reference genome (e.g., GRCm38 for mouse). Generate a gene-cell count matrix using the same alignment and quantification software (e.g., Cell Ranger).

- Step 4: Analytical Comparison. Evaluate key single-cell metrics:

- Number of genes detected per cell.

- Saturation of gene expression.

- Total number of cells identified after doublet removal and quality control.

- Concordance of differentially expressed genes between defined cell populations.

Protocol 3: Whole Genome Sequencing for Variant and Epigenetic Detection

This protocol benchmarks performance in comprehensive genome analysis, including variant calling and direct detection of base modifications [12].

- Step 1: Sample and Library Prep. Use a high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from a reference cell line (e.g., NA12878). Prepare libraries for both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (PacBio) platforms following manufacturers' guidelines.

- Step 2: Sequencing. Sequence the same DNA sample on the Illumina and PacBio platforms. For PacBio, aim for a minimum of 8x coverage to facilitate high-accuracy consensus calling.

- Step 3: Variant Calling and Assembly. For Illumina data, call SNPs and indels using a standard pipeline (e.g., BWA-GATK). For PacBio data, generate circular consensus sequences (CCS) or use the long reads for de novo assembly. Call variants against the reference genome.

- Step 4: Comparative Analysis.

- Variant Concordance: Compare SNP and indel calls between platforms in the benchmark regions.

- Assembly Metrics: For PacBio, assess contiguity using the N50 contig length.

- Structural Variant Detection: Identify large-scale variants from PacBio data and validate with Illumina data.

- Methylation Detection: Use the

kineticstools from SMRT Link to directly detect base modifications (e.g., 6mA, 4mC) from the PacBio data, which is not possible with standard Illumina sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2. Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technology Association |

|---|---|---|

| Reversible Terminator dNTPs | Fluorescently labeled nucleotides that allow one-base-at-a-time incorporation during sequencing-by-synthesis. | SBS (Illumina) [9] |

| Patterned Flow Cell | A substrate with nano-wells that enables ordered, high-density clustering of DNA templates, maximizing throughput. | SBS (Illumina) [9] |

| Ion Sphere Particles (ISPs) | Micron-sized beads used as a solid support for emulsion PCR-based template amplification. | Ion Semiconductor [14] |

| Semiconductor Sequencing Chip | A proprietary chip containing millions of microwell sensors that detect pH changes from nucleotide incorporation. | Ion Semiconductor [10] |

| SMRT Cell | A consumable containing thousands of Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs) that confine observation to a single polymerase molecule. | SMRT (PacBio) [12] |

| PhiX Control Library | A well-characterized, clonal library derived from the PhiX bacteriophage genome used for run quality control and calibration. | SBS (Illumina) [13] |

| Polymerase Binding Kit | Reagents for binding DNA polymerase to the template before sequencing begins. | SMRT (PacBio) [12] |

| Avidity Sequencing Reagents | Multivalent nucleotide ligands (Avidites) that enable highly accurate sequencing with low reagent consumption. | Element Biosciences [17] |

Figure 2. A simplified decision workflow for selecting a sequencing chemistry. The path from sample to analysis highlights the key, technology-specific steps that influence data output and application fitness.

The choice between SBS, Ion Semiconductor, and SMRT sequencing chemistries is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but rather of matching the technology's strengths to the specific research question.

- SBS (Illumina) remains the gold standard for high-throughput, high-accuracy applications requiring precise variant calling, such as large-scale whole-genome sequencing, exome studies, and transcriptome profiling. Its low per-base cost and robust performance make it a versatile first choice for many projects [9] [15].

- Ion Semiconductor (Ion Torrent) offers speed and operational simplicity, with run times measured in hours. Its lower instrument cost can be advantageous. However, researchers must be mindful of its limitations in homopolymer regions and potential for sequence-specific bias, which may affect applications like 16S metagenomic profiling [11] [10].

- SMRT (PacBio) is unparalleled for tasks that require long-range genomic information. It is the technology of choice for de novo genome assembly, fully resolving complex structural variations, and directly detecting epigenetic marks, providing a more complete picture of the genome [12].

For chemogenomic sensitivity research, this translates into a clear decision pathway: SBS is ideal for profiling a vast number of genetic markers across many samples; Ion Torrent may suit rapid, targeted sequencing in a clinical or diagnostic setting; and SMRT is essential for discovering complex genomic rearrangements and haplotype-phased mutations that underlie drug resistance and sensitivity. A strategic combination of these technologies often provides the most comprehensive insights.

In chemogenomic research, where identifying the mode of action (MoA) of compounds relies on precise genomic data, understanding the technical artifacts of sequencing platforms is fundamental to experimental design and data interpretation. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has revolutionized biomedical science by enabling super-fast detection of genomic variants at base-pair resolution, but it simultaneously poses the challenging problem of identifying technical artifacts [18]. These platform-specific error proclivities—whether a technology tends to produce more substitution errors (one base replaced by another) or insertion/deletion errors (indels)—can confound downstream analysis and lead to erroneous biological conclusions if not properly accounted for. This guide provides an objective comparison of major sequencing platforms, detailing their characteristic error profiles to inform robust experimental design in chemogenomic sensitivity studies.

Sequencing Technology Landscape and Error Origins

A Taxonomy of Sequencing Platforms

Current sequencing technologies fall into two primary categories with distinct biochemical approaches and corresponding error patterns:

- Second-Generation Sequencing (Short-Read): Characterized by high accuracy but limited read length, making them susceptible to errors in repetitive regions. Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000, iSeq) dominate this space, with challengers including MGI's DNBSEQ-T7 and Element Biosciences' AVITI [19] [20].

- Third-Generation Sequencing (Long-Read): Technologies from PacBio (SMRT sequencing) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) that generate significantly longer reads capable of spanning repetitive regions but with historically higher error rates [19].

The fundamental distinction in error proclivities between these platforms stems from their underlying biochemistry. Short-read technologies typically employ sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible terminators, while long-read approaches utilize single-molecule real-time sequencing (PacBio) or nanopore-based electrical signal detection (ONT) [19].

Errors in sequencing data are introduced at multiple stages of the workflow, creating a complex error landscape that researchers must navigate:

- Pre-sequencing errors: Artificial C:G to A:T transversions induced during DNA fragmentation via base oxidation, C:G to T:A transitions from spontaneous deamination during PCR, and 8-oxo-G errors from heat, shearing, and metal contaminants [18].

- Sequencing errors: Overlapping/polyclonal cluster formation, optical imperfections, erroneous end-repair, and accumulation of phasing and pre-phasing problems that elevate error rates at read ends [18].

- Data processing errors: Limitations in mapping algorithms, erroneous coding, and inaccuracies in reference genomes [18].

Understanding these sources is crucial for designing experiments that minimize technical artifacts, particularly in chemogenomic studies where detecting true biological signals against background noise is essential.

Comparative Analysis of Platform-Specific Error Profiles

Quantitative Error Proclivities by Platform

Table 1: Platform-Specific Error Profiles and Characteristics

| Platform | Dominant Error Type | Reported Error Rate | Primary Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Substitution errors | ~0.1%-1% [21] [22] | High raw accuracy, high throughput | Short reads, GC bias, difficulty with repetitive regions |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T7 | Substitution errors | Similar to Illumina (high accuracy) [19] | Cost-effective, accurate | Similar limitations to Illumina |

| PacBio (HiFi) | Minimal indels and substitutions | <0.1% with circular consensus [19] | Long reads, minimal GC bias | Higher cost, complex workflow |

| Oxford Nanopore | Indel errors | ~5-20% (1D reads); improved with 2D reads [19] | Ultra-long reads, portability | Higher error rates, particularly in homopolymers |

Detailed Platform Error Characteristics

Illumina and Short-Read Technologies

Illumina platforms exhibit error rates in the range of 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁴ after computational suppression, which represents a 10- to 100-fold improvement over generally accepted estimates [22]. These errors are not randomly distributed but show distinct patterns:

- Substitution bias: Error rates differ significantly by nucleotide substitution type, with A>G/T>C changes occurring at ~10⁻⁴, while A>C/T>G, C>A/G>T, and C>G/G>C changes occur at ~10⁻⁵ [22].

- Sequence context dependency: C>T/G>A errors exhibit strong sequence context dependency, making them potentially predictable and correctable [22].

- Sample-specific effects: Elevated C>A/G>T errors show sample-specific effects rather than systematic patterns [22].

- Amplification impact: Target-enrichment PCR leads to an approximately 6-fold increase in overall error rate [22].

Long-Read Technologies

Long-read platforms have historically suffered from higher error rates but have shown significant improvements in accuracy:

- PacBio Sequel: The circular consensus sequencing approach significantly reduces errors, with recent systems claiming Q30 standards (equivalent to one error in 1000 bases) [20].

- Oxford Nanopore: Error rates have improved from early versions, with current platforms claiming Q28 standards, though indel errors remain predominant, particularly in homopolymer regions [19] [20].

Recent advancements have narrowed the accuracy gap between short and long-read technologies, with some long-read platforms now approaching the accuracy levels traditionally associated with short-read technologies [20].

Experimental Methodologies for Error Profiling

Establishing Gold Standard Datasets

Robust error profiling requires carefully designed experiments that generate gold standard datasets for benchmarking. The following approaches have proven effective:

- Matched cell line dilution: Using matched cancer/normal cell lines (e.g., COLO829/COLO829BL) with known somatic variants diluted to specific ratios (e.g., 1:1000, 1:5000) to establish ground truth for low-frequency variant detection [22].

- UMI-based high-fidelity sequencing: Applying unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to fragments prior to amplification, enabling discrimination of true biological variants from errors by generating consensus sequences within UMI families [21].

- CRISPR-edited cellular models: Creating isogenic cell lines with defined genetic edits (e.g., in DNA mismatch repair genes) to establish controlled systems for studying specific error types [23].

Table 2: Key Experimental Reagents and Solutions for Error Profiling

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Error Profiling | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Matched cell lines | Provide ground truth with known variants | COLO829/COLO829BL for dilution studies [22] |

| UMI adapters | Molecular barcoding for error correction | Discriminating synthesis vs. sequencing errors [24] |

| CRISPR systems | Engineering defined genetic backgrounds | MMR-deficient models for studying indel patterns [23] |

| Polymerase variants | Testing enzyme-specific error profiles | Comparing Q5 vs. Kapa polymerases [22] |

Computational Error Characterization Methods

Computational tools play a crucial role in characterizing and correcting sequencing errors:

- Mapinsights: Performs quality control analysis of sequence alignment files, detecting outliers based on sequencing artifacts in HTS data through cluster analysis of QC features [18].

- SHIFT (Sequence/Position-Independent Highly Accurate Error Profiling Toolkit): Simultaneously profiles DNA synthesis and sequencing errors using oligonucleotide libraries with unique molecular identifiers [24].

- Error correction algorithms: Tools like Coral, Bless, Fiona, and others correct errors computationally, with varying performance across different data types [21].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between major sequencing platforms and their characteristic error profiles:

Implications for Chemogenomic Research

Impact on Chemogenomic Screening

In chemogenomic studies that utilize libraries of haploid deletion mutants to identify drug targets, sequencing errors can significantly confound results by:

- Generating false-positive or false-negative interactions: Errors may create apparent chemical-genetic interactions that don't exist biologically or mask true interactions [25].

- Misleading mode-of-action analysis: Incorrect variant calls can lead to erroneous assignment of compounds to functional modules [25] [26].

- Reducing cross-species concordance: Platform-specific errors may diminish the conservation of compound-functional module relationships observed across species [25].

Platform Selection Guidelines for Chemogenomic Applications

Based on the error profiles characterized in this guide, we recommend the following platform selection strategy for chemogenomic studies:

- For variant discovery in coding regions: Illumina or MGI platforms provide sufficient accuracy for most applications, with error rates computationally suppressible to 10⁻⁵-10⁻⁴ [22].

- For complex genomic regions: PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore platforms are preferable when studying repetitive elements or structural variants, despite their higher indel rates [19].

- For maximum accuracy in low-frequency variant detection: Employ UMI-based approaches with Illumina platforms to achieve the highest sensitivity for variants below 0.1% frequency [22].

The following workflow illustrates a recommended approach for comprehensive error profiling in sequencing experiments:

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, with platforms like Element Biosciences' AVITI and PacBio's Onso achieving Q40 and beyond [20], the fundamental distinction between substitution-prone and indel-prone platforms persists. Successful chemogenomic research requires careful consideration of these platform-specific error proclivities during experimental design, appropriate application of error correction methods, and interpretation of results in the context of technical limitations. By understanding and accounting for these factors, researchers can maximize the sensitivity and specificity of their chemogenomic studies, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and target validation.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, providing tools to decode biological systems at an unprecedented scale and speed. For researchers in chemogenomics—where understanding the interaction between chemical compounds and genomic elements is paramount—selecting the right sequencing platform is crucial. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary NGS platforms, focusing on the critical performance metrics that directly impact chemogenomic sensitivity research: read length, throughput, accuracy, and cost. The massive parallelization capabilities of NGS allow for the simultaneous processing of millions of DNA fragments, making it thousands of times faster and cheaper than traditional Sanger sequencing [27]. However, platform selection involves significant trade-offs between these key metrics, each of which can profoundly influence experimental outcomes in drug discovery and development workflows.

Comparative Analysis of NGS Platform Performance

The performance of NGS platforms varies significantly across key metrics, influencing their suitability for different research applications. The table below summarizes the comparative performance of major sequencing platforms based on current industry data and published studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major NGS Platforms

| Platform/Company | Maximum Read Length | Throughput per Run | Reported Raw Read Accuracy | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Not Specified | 600 Gb - 8 Tb (NovaSeq X Plus) [28] | >99.94% for SNVs [28] | High throughput, superior variant calling accuracy, comprehensive genome coverage [28] | High instrument cost, longer run times for high-output modes |

| Ultima UG 100 | Not Specified | Not Specified (20,000 genomes/year claim) [28] | High in "High-Confidence Region" (excludes 4.2% of genome) [28] | Lower cost per genome, high claimed throughput | Masks challenging genomic regions; 6x more SNV and 22x more indel errors vs. NovaSeq X [28] |

| PacBio Sequel | 10-20 kbp [5] | Varies | Higher error rate (5-20%) [5] | Long reads, less sensitive to GC content [5] | Lower throughput compared to short-read platforms, higher cost per gigabase |

| Oxford Nanopore (e.g., PromethION) | Up to thousands of kbp [5] | High (Ranked 1st in output/hour in one study) [29] | Lower than SGS (5-20%); ~30% for 1D read [5] | Ultra-long reads, real-time sequencing, portability | High raw read error rates, though accuracy improves with 2D sequencing [5] |

| MGI DNBSEQ-T7 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Accurate reads, comparable to Illumina [5] | Cost-effective, accurate; suitable for polishing in hybrid assemblies [5] | Less continuous assembly in SGS-only pipelines vs. Illumina [5] |

Analysis of Key Metric Trade-offs

The data reveals fundamental trade-offs. Short-read platforms (e.g., Illumina, MGI) excel in raw accuracy and high-throughput, making them ideal for variant calling and large-scale sequencing projects [28] [5]. However, they struggle with complex, repetitive genomic regions. Conversely, long-read platforms (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) overcome this limitation by spanning repetitive elements, facilitating de novo genome assembly and resolving complex structural variations, albeit at the cost of higher per-base error rates [5] [27]. Furthermore, a critical consideration is that accuracy claims can be misleading; some platforms achieve high reported accuracy by excluding challenging genomic regions, such as homopolymers and GC-rich sequences, from their analysis, which can mask performance deficits in biologically relevant areas [28].

Experimental Data and Benchmarking Methodologies

Independent benchmarking studies provide critical empirical data for platform evaluation. These experiments often involve sequencing well-characterized reference genomes to compare the output quality, assembly continuity, and variant-calling precision of different platforms and their associated analytical pipelines.

A Practical Yeast Genome Benchmarking Study

A comprehensive 2023 study constructed 212 draft and polished de novo assemblies of the repetitive yeast genome using different sequencing platforms and assemblers [5]. The experimental workflow and key findings offer a model for robust platform comparison.

Experimental Protocol

- Sequencing Platforms: The study utilized four platforms: PacBio Sequel, ONT MinION, Illumina NovaSeq 6000, and MGI DNBSEQ-T7 [5].

- Assembly Algorithms: A range of assemblers was tested, including TGS-only tools (Flye, WTDBG2, Canu), hybrid assemblers (MaSuRCA, WENGAN), and SGS-first assemblers (SPAdes, ABySS) [5].

- Methodology: The genome of Debaryomyces hansenii KCTC27743 was sequenced on all platforms. The resulting data were processed through the different assembly pipelines, and the quality of the resulting assemblies was assessed using metrics such as contiguity and accuracy [5].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow of this benchmarking study.

Figure 1: Benchmarking Workflow for NGS Platforms

Key Findings from the Benchmark

- Long-Read Performance: ONT reads with R7.3 flow cells generated more continuous assemblies than those from PacBio Sequel, despite the presence of homopolymer-associated errors and chimeric contigs [5].

- Short-Read Performance: For SGS-only pipelines, Illumina NovaSeq 6000 provided more accurate and continuous assembly than MGI DNBSEQ-T7. However, MGI provided a cost-effective and accurate alternative, particularly in the polishing process of hybrid assemblies [5].

- Platform-Interplay: The study highlighted that the interaction between the sequencing platform and assembly algorithms has a critical effect on output quality, and a poor combination can lead to significant deterioration in assembly quality [5].

Cost and Performance Trade-off of Read Lengths

A 2024 study specifically evaluated the cost efficiency and performance of different Illumina read lengths (75 bp, 150 bp, and 300 bp) for pathogen identification in metagenomic samples, a relevant scenario for infectious disease chemogenomics [30].

Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation: 48 distinct mock metagenomic compositions were created, enriched with pathogenic taxa, and sequenced in silico at 75 bp, 150 bp, and 300 bp read lengths to generate 144 synthetic metagenomes [30].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Reads were processed through a standardized pipeline (fastp for QC) and taxonomically identified using Kraken2 with a standard database [30].

- Performance Metrics: Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and precision were calculated for each read length based on true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative classifications [30].

Table 2: Performance and Cost by Read Length for Pathogen Detection [30]

| Read Length | Sensitivity (Viral) | Sensitivity (Bacterial) | Precision (Viral & Bacterial) | Relative Cost & Time vs. 75 bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 bp | 99% | 87% | >99.7% | 1x (Baseline) |

| 150 bp | 100% | 95% | >99.7% | ~2x cost, ~2x time |

| 300 bp | 100% | 97% | >99.7% | ~2-3x cost, ~3x time |

Key Findings and Recommendation

The study concluded that while longer reads (150 bp and 300 bp) improved sensitivity for bacterial pathogen detection, the performance gain with 75 bp reads was statistically similar for many taxa, especially viruses. Given the substantial increase in cost and sequencing time for longer reads, the authors recommended prioritizing 75 bp read lengths during disease outbreaks where swift responses are required for viral pathogen detection, as this allows for better resource utilization and faster turnaround [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful NGS experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and consumables. The following table details key solutions required for a typical whole-genome sequencing workflow, which forms the foundation for many chemogenomic applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragments DNA and ligates platform-specific adapters; may include PCR amplification steps. | Critical for defining application (e.g., WGS, WES, targeted panels). Kits are often platform-specific [31]. |

| Sequenceing Reagents/Kits | Contains enzymes, buffers, and fluorescently-tagged nucleotides for the sequencing-by-synthesis reaction. | A major recurring cost; consistent use is key for production-scale sequencing and data quality [28] [32]. |

| Cluster Generation Reagents | Amplifies single DNA molecules on a flow cell surface into clonal clusters, which are required for signal detection. | Used in Illumina platforms (e.g., on the cBot system); essential for generating sufficient signal intensity [27] [10]. |

| Quality Control Kits | Assesses the quality, quantity, and fragment size of the DNA library prior to sequencing. | e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer kits. Prevents sequencing failures and wasted resources [30]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Software for secondary analysis (alignment, variant calling). e.g., DRAGEN, Sentieon, Clara Parabricks. | Not a physical reagent, but crucial for data interpretation. GPU-accelerated pipelines (e.g., Parabricks) can drastically reduce computation time [28] [33]. |

The choice of an NGS platform for chemogenomic research is not one-size-fits-all but must be strategically aligned with the specific experimental goals. Illumina systems currently set the benchmark for high-throughput, accurate variant calling, which is essential for profiling genetic alterations in response to compound treatments [28]. However, long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore are indispensable for characterizing complex genomic structures, rearrangements, and epigenetic modifications that can influence drug response [5] [27].

Researchers must critically evaluate performance claims, particularly regarding accuracy, by examining whether metrics are based on the entire genome or on curated "high-confidence" subsets that may exclude clinically relevant regions [28]. Furthermore, the total cost of ownership extends beyond the price of the sequencer to include a heavy recurring investment in reagents and consumables, which dominate sequencing costs [32], as well as the substantial computational infrastructure or cloud credits needed for data analysis [33]. As the field advances, the integration of AI for data analysis [34] and the growth of cloud-based bioinformatics solutions [33] are poised to further enhance the sensitivity and efficiency of NGS in unlocking the secrets of chemogenomic interactions.

Error-corrected Next-Generation Sequencing (ecNGS) represents a transformative advancement in genetic toxicology, enabling direct, high-sensitivity quantification of chemical-induced mutations with unprecedented accuracy. These technologies address critical limitations of traditional mutagenicity assays by detecting extremely rare mutational events at frequencies as low as 1 in 10⁻⁷ across the entire genome, bypassing the need for phenotypic expression time and clonal selection required by conventional methods [35]. Originally developed for detecting rare mutations in vivo, ecNGS is now being adapted for mutagenicity assessment where it can quantify induced mutations from xenobiotic exposures while providing detailed mutational spectra and exposure-specific signatures [35] [36].

The fundamental innovation of ecNGS lies in its ability to distinguish true biological mutations from sequencing errors through various biochemical or computational approaches. This capability is particularly valuable for regulatory toxicology and cancer risk assessment, where accurate detection of low-frequency mutations is essential for identifying potential genotoxic hazards [36]. As a New Approach Methodology (NAM), ecNGS supports the modernization of toxicological testing paradigms by reducing reliance on animal models and providing more human-relevant mutagenicity data for regulatory decision-making [35] [37]. The integration of ecNGS into standard toxicology study designs represents a significant advancement toward more predictive safety assessments for pharmaceuticals, industrial chemicals, and environmental contaminants.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Core ecNGS Methodologies

Multiple ecNGS platforms have been developed, each employing distinct strategies for error correction while sharing the common goal of accurate mutation detection:

Duplex Sequencing (Duplex-seq) utilizes molecular barcodes attached to both strands of double-stranded DNA fragments. After sequencing, bioinformatic analysis groups reads into families derived from the same original molecule, enabling generation of consensus sequences that eliminate errors not present in both DNA strands. This approach typically reduces error rates from approximately 1% to 1 false mutation per 10⁷ bases or lower, making it particularly suitable for detecting rare mutations in heterogeneous cell populations [35].

Hawk-Seq employs an optimized library preparation protocol with unique dual-indexing strategies and computational processing to generate double-stranded DNA consensus sequences (dsDCS). This method has demonstrated high inter-laboratory reproducibility in detecting dose-dependent increases in base substitution frequencies specific to different mutagens, showing strong concordance with traditional transgenic rodent assays [38].

Pacific Biosciences HiFi Sequencing utilizes circular consensus sequencing (CCS) technology, where DNA molecules are circularized and sequenced multiple times through continuous passes around the circular template. By averaging these multiple observations, the system generates highly accurate long reads (Q30-Q40 accuracy, 99.9-99.99%) with typical lengths of 10-25 kilobases, combining long-read advantages with high accuracy [39].

Oxford Nanopore Duplex Sequencing sequences both strands of double-stranded DNA molecules using a specialized hairpin adapter. The basecaller aligns the two complementary reads to correct random errors and resolve ambiguous regions, with duplex reads regularly exceeding Q30 (>99.9%) accuracy while maintaining the platform's characteristic long read lengths [39].

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Robust ecNGS mutagenicity assessment follows standardized experimental workflows that can be adapted to various testing scenarios:

In Vitro Testing in Metabolically Competent Cells: The protocol employing human HepaRG cells exemplifies a comprehensive approach to in vitro mutagenicity assessment. Differentiated No-Spin HepaRG cells are seeded at approximately 4.8 × 10⁵ viable cells per well in 24-well collagen-coated plates and cultured for 7 days to regain peak metabolic function [35]. Cells are exposed to test compounds for 24 hours, after which the test articles are removed and media is refreshed. Cells are then stimulated with human Epidermal Growth Factor-1 (hEGF) for 72 hours to induce cell division, followed by transfer to new plates for 48 hours in maintenance medium and a second round of hEGF stimulation to induce additional population doublings [35]. Following this expansion phase, cells are harvested for DNA isolation and ecNGS library preparation.

In Vivo Integration in Repeat-Dose Toxicity Studies: ecNGS protocols can be seamlessly incorporated into standard ≥28-day repeat-dose toxicity studies, advancing 3R principles by generating mutagenicity data without requiring additional animals [37]. Following the dosing period, genomic DNA is isolated from target tissues (typically liver) using high-quality extraction kits such as the RecoverEase DNA Isolation Kit. The extracted DNA undergoes quality control assessment for concentration, purity, and integrity before ecNGS library preparation [38].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: For Hawk-Seq, 60 ng of genomic DNA is fragmented to a peak size of 350 bp using a focused-ultrasonicator. The fragmented DNA undergoes end repair, 3' dA-tailing, and ligation to dual-indexed adapters using commercial library preparation kits [38]. After adapter ligation, libraries are amplified through optimized PCR cycles, quantified, and sequenced on high-throughput platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq6000 to yield at least 50 million paired-end reads per sample [38].

Figure 1: Comprehensive ecNGS Workflow for Mutagenicity Assessment

Performance Comparison of ecNGS Platforms

Technical Specifications and Capabilities

The evolving landscape of ecNGS technologies offers researchers multiple platforms with complementary strengths for mutagenicity assessment:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Major ecNGS Platforms

| Platform | Error Correction Mechanism | Accuracy | Typical Read Length | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplex Sequencing | Molecular barcodes + consensus calling | ~1 error per 10⁷ bases | 100-300 bp | Highest accuracy for low-frequency variants; well-validated | In vitro & in vivo mutagenicity screening; mutational signature analysis [35] |

| Hawk-Seq | Dual-indexing + dsDCS generation | High (inter-lab reproducible) | 150-300 bp | High inter-laboratory reproducibility; strong TGR concordance | Quantitative mutagenicity assessment; regulatory studies [38] |

| PacBio HiFi | Circular consensus sequencing (CCS) | Q30-Q40 (99.9-99.99%) | 10-25 kb | Long reads with high accuracy; detects structural variants | Complex genomic regions; phased mutation analysis [39] |

| Oxford Nanopore Duplex | Dual-strand sequencing + reconciliation | >Q30 (>99.9%) | 10-30 kb | Real-time sequencing; ultra-long reads; direct methylation detection | Comprehensive genomic characterization; integrated epigenomic assessment [39] |

Quantitative Performance in Mutagenicity Assessment

Recent benchmarking studies have demonstrated the robust performance of ecNGS platforms in detecting chemical-induced mutations:

Table 2: Mutagenicity Detection Performance Across Platforms

| Experimental Scenario | Platform | Mutation Frequency Increase | Mutational Signature | Concordance with Traditional Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepaRG cells + ENU [35] | Duplex Sequencing | Dose-responsive increase | Distinct alkylating substitution patterns | Complementary to cytogenetic endpoints |

| gpt delta mice + B[a]P [38] | Hawk-Seq | 4.6-fold OMF increase | C>A transversions (SBS4-like) | Correlation with gpt MFs (r²=0.64) |

| gpt delta mice + ENU [38] | Hawk-Seq | 14.2-fold OMF increase | Multiple substitution types | Higher sensitivity than gpt assay (6.1-fold) |

| gpt delta mice + MNU [38] | Hawk-Seq | 4.5-fold OMF increase | Alkylation signature | Higher sensitivity than gpt assay (2.5-fold) |

| HepaRG cells + Cisplatin [35] | Duplex Sequencing | Modest increase | C>A enriched spectra | COSMIC SBS31/32 enrichment |

Key: OMF = Overall Mutation Frequency; B[a]P = Benzo[a]pyrene; ENU = N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea; MNU = N-methyl-N-nitrosourea

The data demonstrate that ecNGS platforms consistently detect compound-specific mutational patterns with sensitivity comparable or superior to traditional transgenic rodent assays. Hawk-Seq showed particularly strong performance with high inter-laboratory reproducibility (correlation coefficient r² > 0.97 for base substitution frequencies across three independent laboratories) and excellent concordance with established regulatory models [38]. Duplex sequencing in HepaRG cells successfully identified mechanism-relevant mutational signatures, including enrichment of COSMIC SBS4 for benzo[a]pyrene (consistent with tobacco smoke exposure signatures) and SBS11 for ethyl methanesulfonate, supporting the mechanistic relevance of this human cell-based model [35].

Figure 2: Mutagen Classes and Their Detection by ecNGS

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of ecNGS for mutagenicity assessment requires specific reagent systems and laboratory materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ecNGS Mutagenicity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolically Competent Cells | Human-relevant xenobiotic metabolism | HepaRG cells [35] | Require 7-day differentiation for optimal metabolic function |

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA isolation | RecoverEase DNA Isolation Kit [38] | Critical for long-read applications; requires quality verification |

| Library Preparation Kits | ecNGS-compatible library construction | TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit [38] | Optimized for complex genomic DNA inputs |

| Molecular Barcodes/Adapters | Unique identification of DNA molecules | Duplex-seq barcodes; ONT Duplex adapters [35] [39] | Platform-specific requirements |

| DNA Repair Enzymes | Damage removal from treated samples | End repair mix; A-tailing enzymes | Essential for chemically damaged DNA |

| Quality Control Assays | DNA and library quality assessment | Fragment Analyzer; Bioanalyzer; Qubit [38] | Multiple QC checkpoints recommended |

| Positive Control Compounds | Assay performance verification | EMS, ENU, B[a]P, Cisplatin [35] | Mechanism-based coverage important |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data processing and mutation calling | Bowtie2, SAMtools, Cutadapt [38] | Custom pipelines often required |

Error-corrected NGS technologies represent a paradigm shift in mutagenicity assessment, offering unprecedented sensitivity, mechanistic insight, and human relevance compared to traditional approaches. The benchmarking data presented demonstrate that platforms such as Duplex Sequencing and Hawk-Seq provide reproducible, quantitative mutagenicity data with strong concordance to established regulatory models while enabling detailed characterization of mutational signatures. As the field advances toward regulatory acceptance, with active IWGT workgroups developing recommendations for OECD test guideline integration, ecNGS is poised to become an essential component of next-generation genotoxicity testing strategies [37]. The continued standardization of experimental protocols and bioinformatic pipelines will further enhance the reliability and adoption of these powerful methodologies for comprehensive mutagenicity assessment in chemical safety evaluation and drug development.

Designing Robust Chemogenomic Assays: From Library Preparation to Data Analysis

The emergence of advanced genomic tools is reshaping how we detect and assess the genotoxic impact of chemical exposures. Within this context, the choice of biospecimen—specifically, whether to use whole cellular DNA (wcDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA)—is paramount. This guide provides an objective comparison of wcDNA and cfDNA extraction for chemical exposure studies, framing the discussion within the broader effort to benchmark Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms for chemogenomic sensitivity research. The selection between these two sources dictates the biological context of the analysis, influencing the sensitivity, specificity, and ultimate interpretation of mutagenic or genotoxic events [40] [41]. wcDNA offers a snapshot of the genomic state within intact cells, while cfDNA provides a systemic, dynamic view of cellular death and tissue damage released into the circulation [40] [42]. This comparison will delve into their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in optimizing their study designs.

Performance Comparison: wcDNA vs. cfDNA

The decision between wcDNA and cfDNA hinges on the specific research question. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and optimal applications of each source to inform experimental design.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Applications of wcDNA and cfDNA

| Feature | Whole Cellular DNA (wcDNA) | Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Source | Intact cells (e.g., lymphocytes, cultured cells) [41] | Bodily fluids (e.g., blood plasma, urine) derived from apoptotic/necrotic cells or active release [40] [42] [43] |

| Primary Application | Assessing cumulative, persistent genomic damage within a specific cell population [44] [41] | Detecting real-time, systemic genotoxic stress and tissue-specific damage [40] [41] |

| Key Strength | Direct measurement of mutations and chromosomal damage in target cells; well-established for in vitro models [45] [35] | Minimally invasive serial sampling; captures a global response; can reflect tissue of origin via fragmentomics and methylation [40] [46] |

| Key Limitation | Requires access to specific cell populations; invasive sampling limits longitudinal tracking [41] | Lower DNA yield; potential background from clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) or other non-target tissues; preanalytical variables are critical [40] [43] |

| Ideal for | In vitro mutagenicity testing [45] [35], occupational exposure studies on specific blood cells [41] | Longitudinal monitoring of toxic insult [42] [41], early detection of organ-specific toxicity (e.g., cardiotoxicity) [42] |

Performance data from direct comparative studies underscores the practical implications of this choice. In occupational exposure settings, cfDNA has proven to be a sensitive biomarker.

Table 2: Performance Data in Occupational Exposure Studies

| Study Population | Exposure | wcDNA Analysis (Comet Assay) | cfDNA Analysis (Concentration) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car Paint Workers (n=33) [41] | Benzene, Toluene, Xylene (BTX) | Significant increase in DNA damage in lymphocytes of exposed vs. non-exposed individuals [41] | Significant increase in serum cfDNA in exposed (up to 2500 ng/mL) vs. non-exposed (0–580 ng/mL) [41] | Both wcDNA and cfDNA quantification confirmed genotoxic damage from occupational exposure, validating cfDNA as a reliable biomarker [41] |

| Professional Soldiers (n=33) [44] | Ammunition-related chemicals (e.g., diphenylamine, VOCs) | Not Assessed | Identification of new somatic SNPs in cfDNA (via UltraSeek Lung Panel) not present in congenital (buccal) genotype [44] | cfDNA analysis detected genome instability and mutations related to lung carcinogenesis, suggesting potential for early risk monitoring [44] |

Experimental Protocols for cfDNA Analysis

cfDNA Extraction and Quality Control

Robust and reproducible results in cfDNA analysis are heavily dependent on standardized preanalytical protocols [40] [43]. The following methodology is adapted from comparative studies.

- Sample Collection: Blood should be collected in specialized blood collection tubes containing preservatives, such as Streck Cell-Free DNA BCTs, which maintain sample integrity for up to 3 days at room temperature. This is comparable to the stability in standard K2EDTA tubes for only 6 hours [40]. For high-throughput needs, diagnostic leukapheresis can provide high-volume plasma samples [43].

- Plasma Separation: A two-step centrifugation protocol is critical to remove cells and debris. An initial centrifugation at 2,000–3,000 × g for 10 minutes separates plasma from blood cells. The transferred plasma is then subjected to a second, high-speed centrifugation at 14,000–16,000 × g for 10 minutes to eliminate any remaining cellular material [43] [41].

- cfDNA Extraction: Several commercial kits are available. Performance comparisons indicate that the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (CNA) consistently yields the highest quantity of cfDNA, including short-sized fragments, from a 2 mL plasma input. Conversely, the Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit (RSC) may yield a lower total quantity but can result in higher variant allelic frequencies (VAFs) for mutation detection, potentially due to less co-extraction of longer, non-target DNA [43]. The QIAamp MinElute ccfDNA Kit (ME) enables processing of larger plasma volumes (e.g., 8 mL), which can be beneficial for obtaining highly concentrated eluates for downstream NGS [43].

- Quality Control and Quantification: Quantification should move beyond simple fluorometry (e.g., Qubit). Integrity and fragment size distribution must be assessed using a Fragment Analyzer or Bioanalyzer. Furthermore, the amplifiability of specific fragment lengths can be confirmed with a multi-size ddPCR assay (e.g., targeting 137 bp, 420 bp, and 1950 bp fragments of a reference gene like β-actin) [43].

Error-Corrected NGS (ecNGS) for Mutation Detection

The following workflow, known as Hawk-Seq, details the application of ecNGS for detecting chemically-induced mutations, a key tool for chemogenomic sensitivity research [47].

- Library Preparation: DNA (either wcDNA or cfDNA) is sheared to a peak size of ~350 bp using a focused-ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris). Sheared DNA fragments are then subjected to end repair, A-tailing, and ligation to indexed adaptors using a library prep kit such as the TruSeq Nano DNA Low Throughput Library Prep Kit [47].

- Consensus Sequencing: This is the core error-correction step. The adapted library is sequenced on a platform like the Illumina NovaSeq6000 or NextSeq2000 to a high depth (e.g., >50 million paired-end reads). Bioinformatic processing then groups read pairs that share the same genomic start and end positions into Same Position Groups (SP-Gs). These groups are divided by orientation, and only those containing reads in both orientations are used to generate a double-stranded DNA Consensus Sequence (dsDCS). This process dramatically reduces errors inherent to the sequencing platform itself [47].

- Mutation Calling and Signature Analysis: The dsDCS reads are mapped to the reference genome. Base substitutions are enumerated after filtering out known genomic positions listed in databases like dbSNP. Mutation frequency is calculated for each of the six possible substitution types. The resulting mutation patterns can be analyzed as 96-dimensional trinucleotide profiles and decomposed into known COSMIC mutational signatures (e.g., SBS4 for benzo[a]pyrene exposure) using tools like the deconstructSigs package [45] [47].

Diagram 1: Error-Corrected NGS Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Successful execution of these protocols relies on specific research reagents and platforms. The table below lists key solutions for cfDNA and wcDNA analysis in exposure studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application | Example Products / Models |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent gDNA contamination and preserve cfDNA profile during storage/transport. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCTs [40] |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify short-fragment cfDNA from plasma with high efficiency and minimal contamination. | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (CNA), Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit (RSC), QIAamp MinElute ccfDNA Kit (ME) [43] |

| Fragment Analyzer | Critical quality control instrument for assessing the size distribution and integrity of extracted cfDNA. | Agilent 4200 TapeStation, Fragment Analyzer Systems [43] |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of specific DNA targets (e.g., mutations, mitochondrial DNA); assesses DNA amplifiability across fragment sizes. | Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System [42] [43] |

| Error-Corrected NGS Platform | High-sensitivity detection of ultra-rare mutations by eliminating sequencing errors via consensus calling. | Hawk-Seq, Duplex Sequencing [45] [35] [47] |

| Metabolically Competent Cell Models | Human-relevant in vitro systems for genotoxicity testing; provide endogenous bioactivation of pro-mutagens. | HepaRG cells [45] [35] |

| Organoid Culture Systems | Complex 3D human tissue models for studying development, toxicity, and identifying cfDNA markers in conditioned media. | Cardiac organoids [42] |

Analysis and Decision Framework

The choice between wcDNA and cfDNA is not merely technical but conceptual, dictating whether the research examines the "archive" of damage within cells or the "real-time report" of toxicity circulating in biofluids. The following diagram provides a logical framework for this decision.

Diagram 2: Decision Framework for DNA Source Selection

Impact of NGS Platform Selection

The sensitivity of mutation detection, especially for the low-frequency variants induced by chemical exposure, is profoundly affected by the choice of NGS platform and methodology. Standard NGS is plagued by high error rates, but ecNGS methods like Hawk-Seq and Duplex Sequencing reduce these errors by several orders of magnitude, enabling the direct detection of mutagen-induced mutations [45] [47]. However, the sequencing instrument itself contributes a unique background error profile. A comparative study of four platforms using the same Hawk-Seq protocol found that while all could detect benzo[a]pyrene-induced G:C to T:A mutations, the background error rates varied: HiSeq2500 (0.22 × 10⁻⁶), NovaSeq6000 (0.36 × 10⁻⁶), NextSeq2000 (0.46 × 10⁻⁶), and DNBSEQ-G400 (0.26 × 10⁻⁶) [47]. This highlights the necessity of platform-specific validation and baseline establishment in chemogenomic research.

For cfDNA analysis in particular, the GEMINI approach leverages low-coverage whole-genome sequencing to analyze genome-wide mutational profiles. It distinguishes cancer-derived cfDNA by comparing mutation type-specific frequencies in genomic regions associated with cancer versus control regions, effectively subtracting background noise and enabling detection of early-stage disease [46]. This underscores the potential of sophisticated bioinformatic strategies to extract maximal information from complex cfDNA samples.

The optimal selection between wcDNA and cfDNA is a strategic decision that directly shapes the sensitivity and applicability of chemogenomic exposure studies. wcDNA remains the cornerstone for direct, in vitro mutagenicity assessment within defined cell populations. In contrast, cfDNA offers a powerful, minimally invasive window into systemic genotoxic stress and organ-specific damage, enabling longitudinal monitoring that is impossible with cellular sources. The convergence of robust preanalytical protocols, error-corrected NGS, and advanced bioinformatic analysis is pushing the boundaries of detection. As the field moves towards standardized New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) for regulatory toxicology, understanding the complementary strengths of wcDNA and cfDNA will be crucial for designing robust, human-relevant studies that accurately define the genotoxic risk of chemical exposures.

In chemogenomic sensitivity research, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become an indispensable tool for uncovering interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. A significant technical challenge in this field, particularly when working with host-associated microbes or infection models, is the overwhelming abundance of host DNA which can constitute over 99% of the genetic material in a sample. This host DNA background consumes valuable sequencing capacity and obscures the detection of microbial signals, ultimately reducing the sensitivity and cost-effectiveness of NGS experiments [48]. Effective library preparation must therefore not only convert nucleic acids into sequenceable formats but also strategically minimize host-derived sequences to maximize information recovery from microbial populations.

This guide objectively compares current methodologies for host DNA depletion in library preparation, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers select optimal strategies for their specific chemogenomic research applications.

Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Techniques

Multiple approaches have been developed to address the challenge of host DNA contamination, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. The most effective methods can be categorized into pre-extraction physical separation techniques and post-extraction biochemical enrichment methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Host DNA Depletion Techniques

| Method | Mechanism | Host Depletion Efficiency | Microbial Recovery | Workflow Complexity | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZISC-based Filtration | Physical retention of host cells based on zwitterionic interface coating | >99% WBC removal [48] | High (>90% bacterial passage) [48] | Low (single-step filtration) | Moderate (specialized filters) |

| Differential Lysis | Selective chemical lysis of host cells followed by centrifugation | Variable (70-95%) [48] | Moderate to High (potential co-loss with host debris) | Moderate (multiple steps) | Low (standard reagents) |

| Methylated DNA Depletion | Biochemical removal of CpG-methylated host DNA | Moderate (limited to methylated regions) [48] | High (unmethylated microbial DNA preserved) | High (specialized kits) | High (enzymatic reagents) |