Advanced Enrichment Strategies for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries: A Guide for Drug Discovery Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enrichment strategies for chemogenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) libraries, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Enrichment Strategies for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries: A Guide for Drug Discovery Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enrichment strategies for chemogenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS) libraries, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of NGS library preparation and its critical role in modern drug discovery. The scope extends to detailed methodological approaches, including hybridization capture and amplicon-based techniques, their practical applications in target identification and mechanism of action studies, and essential troubleshooting and optimization protocols to overcome common challenges like host DNA background and amplification bias. Finally, it outlines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different enrichment methods, ensuring data reliability and clinical translatability in accordance with emerging regulatory standards.

The Foundation of Chemogenomic NGS: Principles, Market Landscape, and Strategic Value in Drug Discovery

Defining Chemogenomic NGS and Its Role in Modern Drug Development

Chemogenomics represents a powerful integrative strategy in modern drug discovery, combining large-scale genomic characterization with functional drug response profiling. At its core, chemogenomics utilizes targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) to identify molecular alterations in disease models and patient samples, while parallel ex vivo drug sensitivity and resistance profiling (DSRP) assesses cellular responses to therapeutic compounds [1]. This dual approach creates a comprehensive functional genomic landscape that links specific genetic alterations with therapeutic vulnerabilities, enabling more precise treatment strategies for complex diseases including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and other malignancies [1].

The chemogenomic framework has emerged as a solution to one of the fundamental challenges in precision medicine: while genomic data can identify "actionable mutations," this information alone provides limited predictive value for treatment success [1]. Many targeted therapies used as monotherapies produce short-lived responses due to emergent drug resistance, necessitating combinations that target multiple pathways simultaneously [1]. By functionally testing dozens of drug compounds against patient-derived cells in rigorous concentration-response formats, researchers can identify effective therapeutic combinations tailored to individual patient profiles, potentially overcoming the limitations of genomics-only approaches [1].

Key Enrichment Strategies for Chemogenomic NGS Libraries

The foundation of any robust chemogenomic NGS workflow depends on effective target enrichment strategies to focus sequencing efforts on genomic regions of highest research and clinical relevance. The two primary enrichment methodologies—hybridization capture and amplicon-based approaches—offer distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must consider based on their specific application requirements [2] [3].

Hybridization Capture-Based Enrichment

Hybridization capture utilizes biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (baits) that are complementary to genomic regions of interest. These probes hybridize to target sequences within randomly sheared genomic DNA fragments, followed by magnetic pulldown to isolate the captured regions prior to sequencing [2] [4]. This method begins with random fragmentation of input DNA via acoustic shearing or enzymatic cleavage, generating overlapping fragments that provide comprehensive coverage of target regions [3]. The use of long oligonucleotide baits (typically RNA or DNA) allows for tolerant binding that captures all alleles equally, even in the presence of novel variants [3].

Key advantages of hybridization capture include:

- Superior uniformity of coverage across target regions [3]

- Reduced false positives from PCR artefacts due to minimal amplification [3]

- Comprehensive variant detection including single nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy number variations, and gene fusions [2]

- Enhanced discovery power for novel variants beyond known polymorphisms [4]

This method is particularly suited for larger target regions (typically >50 genes) including whole exome sequencing and comprehensive cancer panels, where its robust performance with challenging samples such as formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue offsets its longer workflow duration [3] [4].

Amplicon-Based Target Enrichment

Amplicon-based enrichment employs multiplexed polymerase chain reactions (PCR) with primers flanking genomic regions of interest to amplify targets thousands of fold [2]. Through careful primer design and reaction optimization, hundreds to thousands of primers can work simultaneously in a single multiplexed PCR reaction to enrich all target genomic regions [2]. Specialized variations including long-range PCR, anchored multiplex PCR, and COLD-PCR have expanded the applications of amplicon-based approaches for particular research needs [2].

Advantages of amplicon-based methods include:

- Rapid workflow with fewer steps and faster turnaround [3]

- Lower DNA input requirements, often as little as 10ng [3]

- Compatibility with degraded samples including FFPE material [2]

- Cost-effectiveness for smaller target regions (<50 genes) [4]

However, amplicon approaches face challenges including primer competition, non-uniform amplification efficiency across regions with varying GC content, and potential allelic dropout when variants occur in primer binding sites [2] [3]. These limitations make amplicon methods less ideal for discovery-oriented applications where novel variant detection is prioritized.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Enrichment Methodologies for Chemogenomic NGS

| Parameter | Hybridization Capture | Amplicon-Based |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Target Size | Large regions (>50 genes), whole exome | Small, well-defined regions (<50 genes) |

| Variant Detection Range | Comprehensive (SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusions) | Optimal for SNVs and small indels |

| Workflow Duration | Longer (can be streamlined to single day) | Shorter (few hours) |

| DNA Input Requirements | Higher (typically ~500ng, can be reduced) | Lower (as little as 10ng) |

| Uniformity of Coverage | Superior, especially for GC-rich regions | Variable, affected by GC content and amplicon length |

| Ability to Detect Novel Variants | Excellent | Limited by primer design |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High | Challenging at large scale |

| Cost Consideration | Cost-effective for larger regions | Cost-effective for smaller regions |

Selection Criteria for Enrichment Strategy

Choosing between hybridization and amplicon-based enrichment requires careful consideration of several experimental factors:

- Target region size and complexity: Hybridization capture excels for larger genomic regions, while amplicon approaches are ideal for smaller, well-defined targets [3] [4]

- Sample quality and quantity: Amplicon methods tolerate lower quality and quantity inputs, while hybridization capture requires sufficient high-quality DNA [3]

- Variant detection requirements: Hybridization capture provides more comprehensive variant profiling across all variant types [4]

- Turnaround time needs: Amplicon workflows offer faster results, while hybridization provides more robust data [3]

- Budget constraints: Amplicon approaches are generally more affordable for smaller target regions [3]

For chemogenomic applications specifically, where both known and novel variants may have therapeutic implications, hybridization capture often provides the optimal balance of comprehensive coverage and accurate variant detection [3] [4] [1].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Chemogenomic Workflow for Drug Discovery

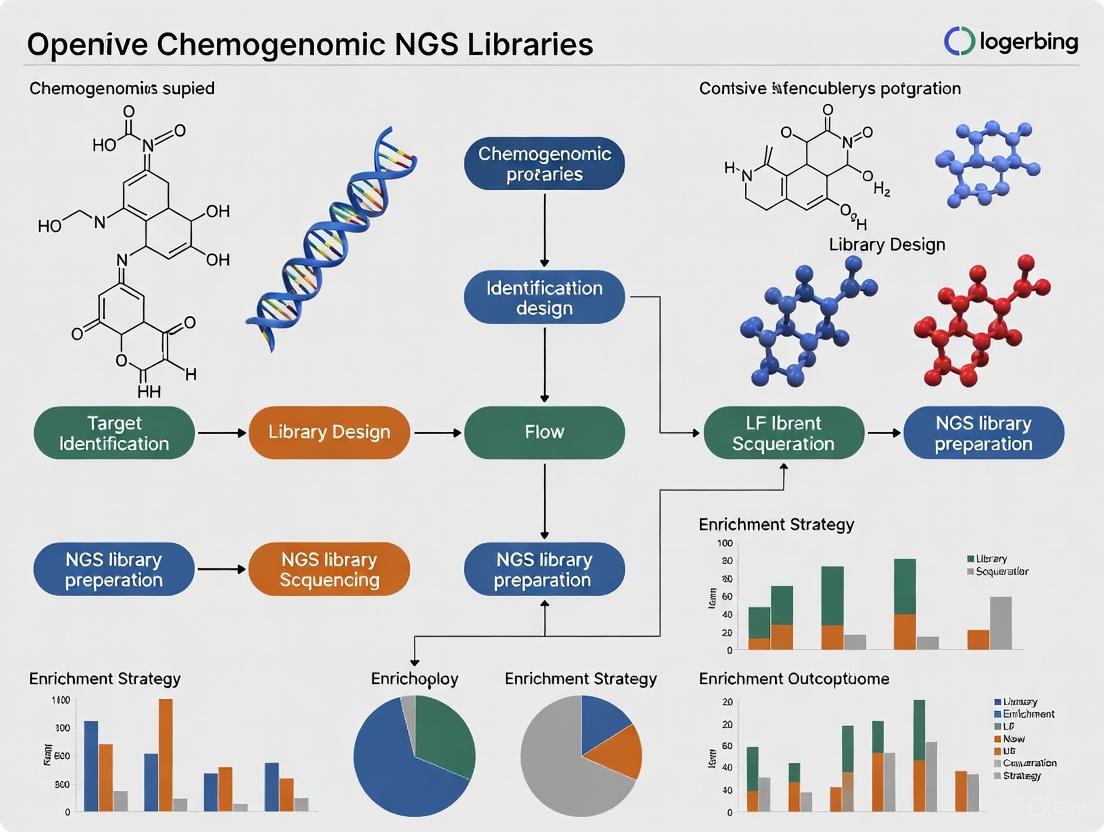

Implementing a robust chemogenomic workflow requires meticulous planning and execution across both genomic and functional screening components. The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated approach:

The typical chemogenomic protocol encompasses the following key stages:

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Obtain patient-derived samples (blood, bone marrow, or tumor tissue) [1]

- Extract high-quality DNA using standardized kits (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) [4]

- For FFPE samples, incorporate DNA repair steps to address formalin-induced damage [3]

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and assess quality via fragment analysis

Targeted NGS Library Preparation

- Fragment DNA to desired size (200-500bp) via acoustic shearing or enzymatic cleavage [2] [4]

- For hybridization capture: Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation [2]

- For amplicon approaches: Design and optimize multiplex primer panels [2]

- Incorporate sample barcodes to enable multiplex sequencing [5]

Target Enrichment

- For hybridization: Hybridize with biotinylated probes, capture with streptavidin beads, and wash [2] [4]

- For amplicon: Perform multiplex PCR with target-specific primers [2]

- Validate enrichment efficiency via qPCR or capillary electrophoresis

Next-Generation Sequencing

- Pool enriched libraries in equimolar ratios

- Sequence on appropriate platform (Illumina, Ion Torrent, etc.) [6]

- Achieve sufficient depth (>500x for somatic variants in heterogeneous samples) [3]

Variant Analysis and Interpretation

- Process raw data through bioinformatic pipeline (alignment, variant calling, annotation) [7]

- Filter and prioritize variants based on quality metrics and functional impact

- Identify "actionable mutations" with therapeutic implications [1]

Ex Vivo Drug Sensitivity and Resistance Profiling

Parallel to genomic analysis, functional drug screening provides essential complementary data:

Sample Processing

- Isolate viable cells from patient specimens (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells) [1]

- Cryopreserve cells if not testing immediately, ensuring consistent viability across batches

Drug Panel Preparation

- Curate drug library encompassing targeted therapies, chemotherapeutics, and experimental compounds [1]

- Include clinically relevant combinations in addition to single agents

- Prepare serial dilutions to establish concentration-response curves

Ex Vivo Drug Exposure

- Plate cells in multi-well formats with precision liquid handling systems

- Add drug compounds across concentration ranges (typically 5-8 concentrations)

- Incubate for 72-96 hours under physiologically relevant conditions [1]

Viability Assessment

- Measure cell viability using ATP-based, resazurin reduction, or apoptotic assays

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle-only, maximal cell death)

- Perform technical replicates to ensure data robustness

Data Analysis

- Calculate half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values for each drug [1]

- Normalize responses across patients using Z-score transformation: Z = (patient EC50 - mean EC50 of reference population) / standard deviation [1]

- Establish response thresholds (e.g., Z-score < -0.5 indicates sensitivity) [1]

Chemogenomic Data Integration

The power of chemogenomics emerges from integrating genomic and functional data:

Multidisciplinary Review

- Convene molecular biologists, clinicians, and pharmacologists to review integrated datasets [1]

- Correlate specific genomic alterations with drug sensitivity patterns

- Identify outlier responses that may reveal novel biomarker-drug relationships

Treatment Strategy Formulation

- Prioritize drugs demonstrating exceptional sensitivity in functional screening [1]

- Validate mechanistic connections between actionable mutations and drug responses

- Design combination strategies that target multiple vulnerability pathways simultaneously [1]

- Consider drug accessibility, potential toxicities, and clinical feasibility

Clinical Translation

- Generate patient-specific report with ranked therapeutic options [1]

- Document evidence supporting each recommendation (genomic and functional)

- Facilitate treatment decisions by clinical care teams

Table 2: Key Reagents and Solutions for Chemogenomic Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Qiagen DNA extraction kits, FFPE DNA repair mixes | Obtain high-quality DNA from various sample types, repair damage in archived specimens [3] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep, IDT xGen reagents | Fragment DNA, add platform-specific adapters, and incorporate sample barcodes [4] |

| Target Enrichment | OGT SureSeq panels, Illumina enrichment kits, Integrated DNA Technologies primers | Hybridization baits or PCR primers to enrich genomic regions of interest [2] [3] [4] |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina sequencing kits, Oxford Nanopore flow cells | Platform-specific chemistries to perform massively parallel sequencing [6] |

| Drug Screening Compounds | Targeted therapies (FLT3, IDH inhibitors), chemotherapeutics | Expose patient-derived cells to therapeutic agents for sensitivity profiling [1] |

| Cell Viability Assays | ATP-based luminescence kits, resazurin reduction assays | Quantify cellular viability after drug exposure to determine efficacy [1] |

Applications in Drug Development

Personalized Therapy Selection

Chemogenomic approaches have demonstrated particular utility in advancing personalized treatment strategies for aggressive malignancies. In a prospective study of relapsed/refractory AML, researchers implemented a tailored treatment strategy (TTS) guided by parallel tNGS and DSRP [1]. The approach successfully identified personalized treatment options for 85% of patients (47/55), with 36 patients receiving recommendations based on both genomic and functional data [1]. Notably, this chemogenomic strategy yielded results within 21 days for 58.3% of patients, meeting clinically feasible timelines for aggressive diseases [1].

The clinical implementation revealed several important patterns:

- Individual patients exhibited distinct sensitivity profiles, with 3-4 potentially active drugs identified per patient on average [1]

- Only five patient samples demonstrated resistance to all tested drugs in the panel [1]

- For the 17 patients who received TTS-guided treatment, objective responses included four complete remissions, one partial remission, and five instances of decreased peripheral blast counts [1]

- The multimodal approach proved particularly valuable when either genomics or functional data alone provided insufficient guidance [1]

Drug Repurposing and Combination Strategy Development

Beyond matching known drug-gene relationships, chemogenomics enables drug repurposing by uncovering unexpected sensitivities unrelated to obvious genomic markers. Systematic correlation of mutation patterns with drug response profiles across patient cohorts can reveal novel biomarker associations, expanding the therapeutic utility of existing agents [1]. This approach is especially valuable for rare mutations where clinical trial evidence is lacking.

Additionally, chemogenomic data provides rational basis for combination therapy development by identifying drugs that target complementary vulnerability pathways. This is particularly important for preventing or overcoming resistance, as single-agent therapies often produce transient responses in complex malignancies [1].

Clinical Trial Optimization

Chemogenomic approaches significantly enhance clinical trial design through:

- Biomarker discovery: Identifying genetic signatures that predict drug response or adverse effects [7] [8]

- Patient stratification: Selecting patient cohorts based on molecular profiles to improve trial success rates [8]

- Pharmacogenomic optimization: Tailoring dosages using variants in drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP450 genes) [8]

The integration of portable NGS technologies like Oxford Nanopore MinION further enables real-time genomic analysis in decentralized trial settings, expanding patient access and accelerating recruitment [8].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of chemogenomics continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements and increasing clinical validation. Several key trends are shaping its future applications in drug development:

Technological Innovations

Sequencing Platform Advancements

- Long-read technologies (Pacific Biosciences, Oxford Nanopore) enable resolution of complex structural variants and repetitive regions [6]

- Single-cell sequencing reveals tumor heterogeneity and resistant subclones [7]

- Portable sequencers facilitate real-time genomic analysis in resource-limited settings [8]

Functional Screening Enhancements

- High-content imaging provides multiparameter readouts beyond simple viability

- Microfluidic platforms enable high-throughput screening with minimal sample input

- CRISPR-based functional genomics systematically identifies genes essential for drug response [7]

Analytical and Computational Advances

Artificial Intelligence Integration

- Machine learning algorithms uncover complex patterns in multi-dimensional chemogenomic data [7]

- Deep learning approaches improve variant calling accuracy (e.g., Google's DeepVariant) [7]

- Predictive modeling of drug response based on integrated molecular profiles

Multi-Omics Integration

- Combining genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics provides comprehensive molecular context [7]

- Spatial transcriptomics maps gene expression within tissue architecture, revealing microenvironmental influences [7]

- Time-resolved analyses capture dynamic adaptations to therapeutic pressure

Clinical Implementation Challenges

Despite promising advances, several challenges remain for widespread chemogenomic implementation:

Operational Hurdles

- Turnaround time requirements for aggressive diseases necessitate streamlined workflows [1]

- Sample quality and quantity limitations, particularly for rare cancers or pediatric malignancies

- Cost-effectiveness demonstrations needed for healthcare system adoption

Analytical Validation

- Standardization of bioinformatic pipelines and functional assay protocols

- Quality control metrics for both genomic and functional data components

- Interpretative frameworks for reconciling discordant genomic and functional findings

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

- Validation of NGS-based biomarkers for regulatory approval [8]

- Data privacy and security for sensitive genetic information [7]

- Equitable access to avoid exacerbating healthcare disparities [7]

The ongoing development of chemogenomic approaches represents a paradigm shift in drug development, moving from population-level averages to individualized therapeutic strategies. As technologies mature and validation accumulates, chemogenomics is poised to become an integral component of precision medicine across diverse therapeutic areas.

Market Dynamics and Growth Catalysts in the NGS Library Preparation Sector

In the evolving landscape of precision medicine and functional genomics, next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation has emerged as a critical determinant of sequencing success, influencing data quality, variant detection accuracy, and ultimately, the reliability of scientific conclusions in chemogenomic research. The global NGS library preparation market, valued at USD 1.79-2.07 billion in 2024-2025, is projected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.30-13.47% to reach USD 4.83-6.44 billion by 2032-2034 [9] [10]. This remarkable growth is catalyzed by escalating demand for precision genomics, widespread adoption of NGS in oncology and infectious disease testing, and technological innovations that continuously improve workflow efficiency and cost-effectiveness. For researchers focused on chemogenomic library enrichment strategies, understanding these market dynamics and their interplay with experimental protocols is no longer a supplementary consideration but a fundamental component of strategic research planning and implementation.

The preparation of sequencing libraries represents the crucial interface between biological samples and sequencing instrumentation, with an estimated over 50% of sequencing failures or suboptimal runs tracing back to library preparation issues [11]. In chemogenomics, where researchers systematically study the interactions between small molecules and biological systems, the integrity of library preparation directly influences the detection of genetic variants, gene expression changes, and epigenetic modifications critical for understanding drug-gene interactions. As the market evolves toward more automated, efficient, and specialized solutions, researchers gain unprecedented opportunities to enhance the quality and throughput of their chemogenomic investigations while navigating an increasingly complex landscape of commercial options and methodological approaches.

Market Analysis: Quantitative Landscape and Growth Trajectories

Global Market Size and Projections

The NGS library preparation market demonstrates robust growth globally, with variations in valuation reflecting different methodological approaches to market sizing across analyst firms. Table 1 summarizes the key market metrics and growth projections from comprehensive market analyses.

Table 1: Global NGS Library Preparation Market Size and Growth Projections

| Metric | 2024-2025 Value | 2032-2034 Projected Value | CAGR (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size | USD 1.79 billion (2024) | USD 4.83 billion (2032) | 13.30% (2025-2032) | SNS Insider [9] |

| Global Market Size | USD 2.07 billion (2025) | USD 6.44 billion (2034) | 13.47% (2025-2034) | Precedence Research [10] |

| U.S. Market Size | USD 0.58 billion (2024) | USD 1.54 billion (2032) | 12.99% (2024-2032) | SNS Insider [9] |

| U.S. Market Size | USD 652.65 million (2024) | USD 2,237.13 million (2034) | 13.11% (2025-2034) | Biospace/Nova One Advisor [12] |

| Automated Systems (Global) | - | USD 895 million (2025) | 11.5% (2025-2033) | Market Report Analytics [13] |

Regional analysis reveals that North America dominated the market in 2024 with a 44% share, attributed to advanced genomic research facilities, well-established healthcare infrastructure, and the presence of major market players [10]. The Asia Pacific region is expected to be the fastest-growing market, projected to grow at a CAGR of 14.42-15% from 2025 to 2034, driven by rapidly expanding healthcare systems, rising investments in biotech and genomics research, and supportive government initiatives [9] [10].

Market Segmentation and Application Analysis

The NGS library preparation market exhibits distinct segmentation patterns across sequencing types, products, applications, and end-users, with particular relevance to chemogenomic research applications. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of market segmentation and dominant categories.

Table 2: NGS Library Preparation Market Segmentation Analysis (2024)

| Segmentation Category | Dominant Segment | Market Share (%) | Fastest-Growing Segment | Projected CAGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Type | Targeted Genome Sequencing | 63.2% | Whole Exome Sequencing | Significant [9] |

| Product | Reagents & Consumables | 78.4% | Instruments | 13.99% [9] |

| Application | Drug & Biomarker Discovery | 65.12% | Disease Diagnostics | Notable [9] |

| End User | Hospitals & Clinical Laboratories | 35.4-42% | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies | 13% [9] [10] |

| Library Preparation Type | Manual/Bench-Top | 55% | Automated/High-Throughput | 14% [10] |

The dominance of targeted genome sequencing (63.2% market share) reflects its cost-effectiveness, sensitivity, and targeted approach in identifying specific genetic variants, making it particularly valuable for chemogenomic applications focused on specific gene families or pathways [9]. The drug & biomarker discovery segment captured 65.12% market share in 2024, underscoring the critical role of NGS in pharmaceutical development and biomarker identification [9]. The anticipated rapid growth of the automated library preparation segment (14% CAGR) highlights the ongoing market shift toward high-throughput, reproducible workflows essential for large-scale chemogenomic screens [10].

Key Market Drivers and Industry Catalysts

Technological Innovations and Workflow Advancements

The NGS library preparation market is being transformed by continuous technological innovations that address longstanding challenges in workflow efficiency, sample quality, and data reliability. Automation of workflows represents a pivotal trend, reducing manual intervention while increasing throughput efficiency and reproducibility [10]. Automated systems can process hundreds of samples simultaneously at high-throughput sequencing facilities, significantly cutting expenses and turnaround times while minimizing human error [14]. The global market for automated NGS library preparation systems is projected to reach $895 million by 2025, expanding at a CAGR of 11.5% through 2033 [13].

The integration of microfluidics technology has revolutionized library preparation by enabling precise microscale control of sample and reagent volumes [10]. This technology supports miniaturization, conserves precious reagents, and guarantees consistent, scalable results across multiple samples – particularly valuable for chemogenomic libraries where reagent costs can be prohibitive at scale. Additionally, advancements in single-cell and low-input library preparation kits now allow high-quality sequencing from minimal DNA or RNA quantities, expanding applications in oncology, developmental biology, and personalized medicine [10]. These innovations offer deep insights into cellular diversity and rare genetic events central to understanding heterogeneous drug responses.

The emergence of tagmentation-based approaches (exemplified by Illumina's Nextera technology) combines fragmentation and adapter tagging into a single step, dramatically reducing processing time [15] [16]. This technology utilizes a transposase enzyme to simultaneously fragment DNA and insert adapter sequences, significantly streamlining the traditional multi-step workflow [15]. The development of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and unique dual indexes (UDIs) provides powerful solutions for multiplexing and accurate demultiplexing, enabling researchers to differentiate true variants from errors introduced during library preparation or amplification [14].

Expanding Applications in Precision Medicine and Drug Development

The growing adoption of NGS across diverse clinical and research applications represents a fundamental driver of market expansion. Precision medicine initiatives worldwide are accelerating demand for robust library preparation solutions, as clinicians and researchers increasingly rely on genomic insights to guide therapy decisions for cancer, rare genetic disorders, and infectious diseases [9]. The United States maintains its leadership position partly due to "rising demand for precision medicine, with extensive genomic research in oncology, rare diseases, and reproductive health" [10].

In pharmaceutical and biotechnology research, NGS library preparation technologies are essential for target identification, validation, and biomarker discovery. The pharmaceutical and biotech R&D segment is expected to grow at a notable CAGR of 13.5%, "driven by the adoption of NGS library preparation technologies, accelerated by increasing investments in clinical trials, personalized therapies, and drug discovery" [10]. For chemogenomic libraries specifically, which aim to comprehensively profile compound-gene interactions, the reliability of library preparation directly impacts the quality of insights into drug mechanisms, toxicity profiles, and potential therapeutic applications.

The rising clinical adoption of NGS-based diagnostics represents another significant growth catalyst. The disease diagnostics segment is poised to witness substantial growth during the forecast period, "with the increasing adoption of NGS in clinical diagnostics for cancer, rare genetic conditions, infectious diseases, and prenatal screening" [9]. This clinical translation generates demand for more robust, reproducible, and efficient library preparation methods that can deliver reliable results in diagnostic settings.

Technical Protocols: NGS Library Preparation Methodologies

Core Workflow for DNA Library Preparation

The fundamental process of preparing DNA sequencing libraries involves a series of meticulously optimized steps to convert genomic DNA into sequencing-ready fragments. The following protocol outlines the standard workflow, with special considerations for chemogenomic applications where preserving the complexity of heterogeneous compound-treated samples is paramount.

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quantification

- Input Material: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from biological samples (cell cultures, tissues, or blood). For chemogenomic studies involving compound treatments, ensure consistent cell numbers and viability across conditions.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate DNA integrity using fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) and fragment analysis (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation). The absorbance ratio (A260/280) should be 1.8-2.0, indicating minimal protein or solvent contamination [17] [14].

- Critical Consideration: For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples common in translational research, implement additional DNA repair steps using specialized enzyme mixes (e.g., SureSeq FFPE DNA Repair Mix) to reverse cross-linking artifacts that can cause false mutation calls [14].

Step 2: DNA Fragmentation

- Objective: Generate DNA fragments within optimal size distribution (typically 200-600 bp for Illumina platforms) [11].

- Methods:

- Mechanical Shearing: Using acoustic focusing technology (e.g., Covaris instruments) for unbiased fragmentation with tight size distributions. Parameters are tuned to achieve desired fragment size [15] [11].

- Enzymatic Fragmentation: Employing non-specific endonucleases (e.g., Fragmentase) or transposase-based "tagmentation" (e.g., Illumina Nextera) that combines fragmentation and adapter tagging in a single step [15].

- Optimization Tip: "Over-fragmentation vs under-fragmentation must be optimized... to avoid fragments that are too short (leading to adapter dimer dominance) or too long (causing poor clustering)" [11].

Step 3: End Repair and A-Tailing

- End Repair: Convert heterogeneous fragment ends (5' or 3' overhangs) to blunt, phosphorylated ends using T4 DNA polymerase (fills 5' overhangs, chews back 3' overhangs) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (phosphorylates 5' ends) [15] [11].

- A-Tailing: Add single adenine nucleotide to 3' ends using Taq polymerase or Klenow exo- fragment, creating complementary overhangs for subsequent adapter ligation [15] [11].

- Protocol Conditions: Typically 30 minutes at 20°C for end repair, followed by 30 minutes at 65°C for A-tailing. Modern kits often combine these steps into a single reaction [11].

Step 4: Adapter Ligation

- Adapter Design: Y-shaped adapters containing platform-specific sequences, unique dual indexes (UDIs) for sample multiplexing, and binding sites for sequencing primers [15] [14].

- Ligation Reaction: Incubate A-tailed fragments with adapter mix using T4 DNA ligase (30 minutes to 2 hours at 20-25°C). Maintain optimal adapter:fragment ratio (~10:1 molar ratio) to maximize ligation efficiency while minimizing adapter dimer formation [15] [11].

- Critical Consideration: Using unique dual indexes (UDIs) where "each library has a completely unique i7 and i5" enables more accurate demultiplexing and prevents index hopping artifacts in multiplexed chemogenomic screens [14].

Step 5: Library Cleanup and Size Selection

- Purification Methods: Use magnetic bead-based cleanups (e.g., AMPure XP beads) to remove enzymes, salts, and short fragments. For precise size selection or when working with small RNAs, implement agarose gel extraction [15].

- Size Selection Parameters: Target library sizes appropriate for your sequencing application. For whole genome sequencing, 350-600 bp inserts are common; for targeted panels, 200-350 bp may be optimal [15].

Step 6: Library Amplification (Optional)

- PCR Amplification: When input DNA is limited (<50 ng), amplify adapter-ligated fragments using high-fidelity DNA polymerases with minimal sequence bias [15] [11].

- Cycle Optimization: "Reduce PCR cycles" to minimize amplification biases, particularly for GC-rich regions. "Increasing the amount of starting material and optimising your extraction steps" can reduce required amplification cycles [14].

- Condition Recommendations: Typically 4-12 cycles using primers complementary to adapter sequences. Include unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during this step to correct for amplification duplicates and detect low-frequency variants [14].

Step 7: Library Quantification and Quality Control

- Quantification Methods:

- Quality Assessment: Analyze library size distribution using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation systems. Ensure adapter dimer contamination is <5% of total signal [15] [11].

Target Enrichment Strategies for Chemogenomic Applications

For chemogenomic studies focused on specific gene families or pathways, target enrichment following library preparation enables deeper sequencing of genomic regions of interest. The two primary approaches—hybridization capture and amplicon-based enrichment—offer distinct advantages for different research scenarios. Table 3 compares these fundamental target enrichment methodologies.

Table 3: Comparison of Target Enrichment Approaches for NGS

| Parameter | Hybridization Capture | Amplicon-Based |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Solution-based hybridization with biotinylated probes (RNA or DNA) to genomic regions of interest followed by magnetic pull-down [2] | PCR amplification of target regions using target-specific primers [2] |

| Advantages | Better uniformity of coverage; fewer false positives; superior for detecting structural variants; compatible with degraded samples (FFPE) [2] [14] | Fast, simple workflow; requires less input DNA; higher sensitivity for low-frequency variants; lower cost [2] |

| Disadvantages | More complex workflow; higher input DNA requirements; longer hands-on time; higher cost [2] | Limited multiplexing capability; amplification biases; primer-driven artifacts; poor uniformity [2] [14] |

| Best For | Comprehensive variant detection; large target regions (>1 Mb); structural variant analysis; degraded samples [2] | Small target panels (<50 genes); low-frequency variant detection; limited sample quantity; rapid turnaround needs [2] |

Hybridization Capture Protocol:

- Library Pooling: Combine up to 96 uniquely indexed libraries in equimolar ratios (total 500-1000 ng DNA).

- Hybridization: Incubate library pool with biotinylated probes (1-16 hours at 65°C) in hybridization buffer containing blocking oligonucleotides to prevent repetitive sequence capture.

- Capture and Wash: Bind probe-library hybrids to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, followed by stringent washes to remove non-specifically bound fragments.

- Amplification: PCR-amplify captured libraries (8-12 cycles) to generate sufficient material for sequencing.

- Specialized Variant: For RNA baits, note that "RNA baits provide better hybridization specificity and higher stability when bound to the DNA ROIs" but require careful handling due to RNA's labile nature [2].

Amplicon-Based Enrichment Protocol:

- Primer Design: Design target-specific primers flanking regions of interest, with possible incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for error correction.

- Multiplex PCR: Optimize primer concentrations and cycling conditions to ensure uniform amplification across all targets. "Hundreds to thousands of primers [may need] to work in unison under similar PCR conditions" [2].

- Library Construction: Ligate sequencing adapters to amplicons or use tailed primers containing adapter sequences.

- Advanced Approach: Consider anchored multiplex PCR, which "is open-ended: only one side of the ROI sequence is targeted using a target-specific primer (anchor), while the other end is targeted with a universal primer" – particularly valuable for detecting novel fusions without prior knowledge of partners [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS library preparation protocols requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each workflow step. The following toolkit outlines critical components for establishing robust library preparation processes, particularly in the context of chemogenomic applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation Enzymes | Tagmentase (Illumina), Fragmentase (NEB) | Simultaneously fragments DNA and adds adapter sequences via transposition [15] | Reduces hands-on time; ideal for high-throughput chemogenomic screens |

| End Repair & A-Tailing Mix | T4 DNA Polymerase, Klenow Fragment, T4 PNK, Taq Polymerase | Converts fragment ends to phosphorylated, blunt-ended or A-tailed molecules [11] | Master mixes combining multiple enzymes streamline workflow |

| Ligation Reagents | T4 DNA Ligase, PEG-containing Buffers | Catalyzes attachment of adapters to A-tailed DNA fragments [15] | High PEG concentrations increase ligation efficiency |

| Specialized Clean-up Beads | AMPure XP, SPRIselect | Size-selective purification of library fragments; removal of adapter dimers [15] [14] | Bead-to-sample ratio determines size selection stringency |

| Library Amplification Mix | High-Fidelity Polymerases (Q5, KAPA HiFi) | PCR amplification of adapter-ligated fragments with minimal bias [14] | "High-fidelity polymerases are preferred to reduce error and bias" [11] |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Illumina CD Indexes, IDT for Illumina | Sample multiplexing with unique combinatorial barcodes [14] | Prevents index hopping; essential for pooled chemogenomic screens |

| Quality Control Kits | Qubit dsDNA HS, Bioanalyzer HS DNA | Accurate quantification and size distribution analysis [14] | qPCR-based quantification most accurately measures amplifiable libraries |

| FFPE Repair Mix | SureSeq FFPE DNA Repair Mix | Enzymatic repair of formalin-induced DNA damage [14] | Critical for working with archival clinical specimens in translational research |

Optimization Strategies and Troubleshooting Guide

Achieving high-quality sequencing libraries requires careful optimization and proactive troubleshooting throughout the preparation process. The following evidence-based strategies address common challenges in NGS library preparation, with particular emphasis on maintaining library complexity and minimizing biases in chemogenomic applications.

Minimizing Amplification Bias: "Reduce PCR cycles" whenever possible, as excessive amplification "can cause a significant drop in diversity and a large skew in your dataset" [14]. When amplification is necessary for low-input samples (a common scenario in primary cell chemogenomic screens), select library preparation kits with "high-efficiency end repair, 3' end 'A' tailing and adaptor ligation as this can help minimise the number of required PCR cycles" [14]. Additionally, consider hybridization-based enrichment strategies over amplicon approaches, as they yield "better uniformity of coverage, fewer false positives, and superior variant detection due to the requirement of fewer PCR cycles" [14].

Addressing Contamination Risks: Implement rigorous laboratory practices including "one room or area... dedicated for pre-PCR testing" to separate nucleic acid extraction and post-amplification steps [17]. Utilize "unique molecular identifiers (UMIs)" to uniquely tag each molecule in a sample library, enabling differentiation between true variants and errors introduced during library preparation or amplification [14]. For automated workflows, ensure "automated systems are often equipped with real-time monitoring capabilities and integrated QC checks to flag any deviations or potential issues" [13].

Optimizing for Challenging Samples: For FFPE samples common in translational chemogenomics, implement specialized repair steps using enzyme mixes "optimised to remove a broad range of damage that can cause artefacts in sequencing data" [14]. For low-input samples (e.g., rare cell populations after compound treatment), consider "advancement in single-cell and low-input library preparation kits [that] now allow high-quality sequencing from minimal DNA or RNA quantities" [10]. Enzymatic fragmentation methods typically "accommodate lower input and fragmented DNA" compared to mechanical shearing approaches [11].

Ensuring Accurate Quantification: Employ multiple quantification methods appropriate for different quality control checkpoints. While fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) are useful for assessing total DNA, "qPCR methods are extremely sensitive and only measure adaptor ligated-sequences," providing the most accurate assessment of sequencing-ready libraries [14]. Proper quantification is critical as "overestimating your library concentration will result in loading the sequencer with too little input and in turn, reduced coverage," while "underestimating your library concentration, you can overload the sequencer and reduce its performance" [14].

The NGS library preparation sector continues to evolve at a remarkable pace, driven by synergistic advancements in market availability, technological innovation, and expanding application horizons. For researchers focused on chemogenomic library enrichment strategies, understanding these dynamics provides not only a competitive advantage but also a framework for making informed methodological decisions that enhance research outcomes. The projected market growth to USD 4.83-6.44 billion by 2032-2034 reflects the increasing centrality of high-quality sequencing library preparation across basic, translational, and clinical research domains [9] [10].

Future directions in the sector point toward increased automation, with the automated NGS library preparation system market projected to reach $895 million by 2025 [13]. This automation trend aligns with the needs of chemogenomic research for high-throughput, reproducible screening capabilities. Additionally, the ongoing development of more efficient enzymatic methods, improved unique dual indexing strategies, and specialized solutions for challenging sample types will continue to expand the experimental possibilities for researchers studying compound-gene interactions.

The convergence of market growth, technological innovation, and methodological refinement in NGS library preparation creates unprecedented opportunities for chemogenomic research. By leveraging these advancements while maintaining rigorous optimization and quality control practices, researchers can generate increasingly reliable, comprehensive, and biologically meaningful data to advance the understanding of how small molecules modulate biological systems – ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

In chemogenomic research, which explores the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems, the quality of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data is paramount. The journey from raw biological sample to a sequenced chemogenomic library is a critical pathway where each step introduces potential biases and artifacts that can compromise data integrity. Sample preparation, encompassing nucleic acid extraction and library construction, is no longer a mere preliminary step but a determinant of experimental success. This process transforms mixtures of nucleic acids from diverse biological samples into sequencing-ready libraries, with specific considerations for chemogenomic applications where accurately capturing variant populations and subtle transcriptional changes is essential [17].

Challenging samples—such as those treated with bioactive compounds, limited cell populations, or fixed specimens—demand robust and optimized preparation protocols. Inefficient library construction can lead to decreased data output, increased chimeric fragments, and biased representation of genomic elements. Furthermore, contamination risks and the substantial costs associated with library preparation necessitate careful planning and execution [17]. This document details the core components and methodologies for establishing a reliable workflow from nucleic acid extraction to library preparation, framed within the context of enrichment strategies for chemogenomic NGS libraries.

Core Component 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction

The initial step in every NGS sample preparation protocol is the isolation of pure, high-quality nucleic acids. The success of all downstream applications, including variant calling and transcriptome analysis in chemogenomics, hinges on this foundational step [17] [14].

Sample Types and Considerations

The optimal sample type for nucleic acid extraction is a homogenous population of cells, such as those from an in vitro culture. However, chemogenomic studies often involve more complex samples, including primary cells, fixed tissues, or samples with limited material from high-throughput chemical screens. The quality of extracted nucleic acids is directly dependent on the quality and appropriate storage of the starting material, with fresh material always recommended but often substituted by properly frozen or cooled samples [17]. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples present a particular challenge due to chemical crosslinking that binds nucleic acids to proteins, resulting in impure, degraded, and fragmented samples. This damage can lead to lost information and false conclusions, such as difficulty distinguishing true low-frequency mutations from damage-induced artifacts [14].

Extraction Methodologies and Comparative Performance

The choice of extraction method can significantly impact sequencing outcomes. The basic steps involve cell disruption, lysis, and nucleic acid purification. A comparative study evaluating different DNA extraction procedures, library preparation protocols, and sequencing platforms found that the investigated extraction procedures did not significantly affect de novo assembly statistics and the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) detected [18]. This suggests that multiple standardized commercial methods can be effective, though optimization for specific sample types is always advised.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits and Their Performance

| Kit Name | Sample Type | Key Features | Impact on Downstream NGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [18] | Bacterial cultures | Standardized silica-membrane protocol | Reliable performance for microbial WGS |

| ChargeSwitch gDNA Mini Bacteria Kit [18] | Bacterial cultures | Magnetic bead-based purification | Reliable performance for microbial WGS |

| Easy-DNA Kit [18] | Purified DNA samples | Organic extraction method | Suitable for pre-extracted DNA |

| Not specified (FFPE repair) [14] | FFPE tissue | Includes enzymatic repair mix | Reduces sequencing artifacts from damaged DNA |

For challenging FFPE samples, a dedicated repair step is recommended. Using a mixture of enzymes optimized to remove a broad range of DNA damage can preserve original complexity and deliver high-quality sequencing data, which is critical for accurate variant detection in chemogenomic studies [14].

Core Component 2: Library Preparation Kits and Strategies

Library preparation is the process of converting purified nucleic acids into a format compatible with NGS platforms. This involves fragmenting the DNA or cDNA, attaching platform-specific adapters, and often includes a PCR amplification step [17].

Library Preparation Workflow and Kit Options

The general workflow for DNA library preparation involves three core steps after fragmentation: End Repair & dA-Tailing, Adapter Ligation, and Library Amplification [17] [19]. Multiple commercial kits are available, optimized for different sequencing platforms like Illumina, and offer varying features to streamline this process.

Table 2: Overview of Commercial Library Preparation Kits

| Kit Name | Fragmentation Method | Input DNA Range | Key Features | Workflow Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Library Prep Kits [20] | Various | Various | Optimized for Illumina platforms; support diverse throughput needs | Varies by kit |

| Invitrogen Collibri PS DNA Library Prep Kit [21] | Not specified | Not specified | Visual feedback for reagent mixing; reduced bias in WGS | ~1.5 hours (PCR-free) |

| Twist Library Preparation EF Kit [19] | Enzymatic | 1 ng – 1 µg | Single-tube reaction; tunable fragment sizes; ideal for automation | Under 2.5 hours |

| Twist Library Preparation Kit [19] | Mechanical (pre-sheared) | Wide range | Accommodates varying DNA input types; minimizes start/stop artifacts | Under 2.5 hours |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit [18] | Enzymatic (Tagmentation) | Low input (e.g., 1 ng) | Simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging via tagmentation | Not specified |

| TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep Kit [18] | Acoustic shearing | High input (1–4 µg) | Random fragmentation reduces uneven sequencing depth | Not specified |

Two main fragmentation approaches are used: mechanical (e.g., acoustic shearing) and enzymatic (e.g., tagmentation). Mechanical methods are known for random fragmentation, which reduces unevenness in sequencing coverage [18]. Enzymatic fragmentation, particularly tagmentation which combines fragmentation and adapter ligation into a single step, significantly reduces hands-on time and costs [17] [19].

Mitigating Bias in Library Preparation

A critical consideration in library preparation, especially for chemogenomics, is the introduction of bias. Amplification via PCR is often necessary for low-input samples but is prone to biases such as PCR duplicates and uneven coverage of GC-rich regions [17] [14]. To minimize this:

- Reduce PCR Cycles: Optimize the workflow to use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary. This can be achieved by increasing starting material where possible and selecting kits with high-efficiency end repair and ligation to minimize the required amplification [14].

- Utilize Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): UMIs are short sequences that uniquely tag each original molecule prior to amplification. This allows for the bioinformatic discrimination of true biological variants from errors introduced during PCR and sequencing, which is vital for detecting low-frequency variants [14].

- Choose Hybridization Over Amplicon Enrichment: For targeted sequencing, a hybridization-based capture strategy is preferable to amplicon-based approaches as it requires fewer PCR cycles, yields better coverage uniformity, and results in fewer false positives [14].

Comparative Analysis: Extraction and Library Prep Impact on Data

Empirical studies have compared the impact of different pre-sequencing choices on final data quality. One study found that three different DNA extraction procedures and two library preparation protocols (Nextera XT and TruSeq Nano) did not significantly affect de novo assembly statistics, SNP calling, or ARG identification for bacterial genomes. A notable exception was observed for two duplicates associated with one PCR-based library preparation kit, highlighting that amplification can be a significant variable [18].

Another comparative analysis of metagenomic NGS (mNGS) on clinical body fluid samples provides insights relevant to complex samples. This study compared whole-cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS to microbial cell-free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS. The mean proportion of host DNA in wcDNA mNGS was 84%, significantly lower than the 95% observed in cfDNA mNGS. Using culture results as a reference, the concordance rate for wcDNA mNGS was 63.33%, compared to 46.67% for cfDNA mNGS. This demonstrates that wcDNA mNGS had significantly higher sensitivity for pathogen detection, although its specificity was compromised, necessitating careful data interpretation [22].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of mNGS Approaches in Clinical Samples

| Sequencing Approach | Mean Host DNA Proportion | Concordance with Culture | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Cell DNA (wcDNA) mNGS [22] | 84% | 63.33% (19/30) | 74.07% | 56.34% |

| Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) mNGS [22] | 95% | 46.67% (14/30) | Not specified | Not specified |

Furthermore, a comparison of two sequencing platforms, Illumina MiSeq and Ion Torrent S5 Plus, for analyzing antimicrobial resistance genes showed that despite different sequencing chemistries, the platforms performed almost equally, with results being closely comparable and showing only minor differences [23]. This suggests that the wet-lab preparation steps may have a more pronounced impact on results than the choice of sequencing platform itself.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful NGS library preparation workflow relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the process.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Library Preparation

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit [17] [18] | Isolates DNA/RNA from biological samples. | Choose based on sample type (e.g., bacterial, FFPE) and required yield/quality. |

| FFPE DNA Repair Mix [14] | Enzymatically reverses cross-links and repairs DNA damage in FFPE samples. | Critical for reducing artifacts and improving variant calling accuracy from archived tissues. |

| Library Preparation Kit [21] [19] | Contains enzymes and reagents for fragmentation, end repair, dA-tailing, adapter ligation, and amplification. | Select based on input amount, fragmentation method (enzymatic/mechanical), and need for automation. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [14] | Short barcodes that tag individual molecules before amplification. | Enables accurate detection of low-frequency variants and removal of PCR duplicates. |

| Size Selection Beads [17] | Purify and select nucleic acid fragments within a specific size range. | Improves sequencing efficiency by removing too large or too small fragments. |

| Library Quantification Kit [14] | Accurately measures the concentration of the final library. | qPCR-based methods are sensitive and measure only adapter-ligated molecules. |

Detailed Protocol: An Optimized Workflow for DNA Library Preparation

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for preparing sequencing-ready libraries from double-stranded DNA, incorporating best practices to minimize bias and ensure quality—a crucial consideration for chemogenomic applications.

Materials and Reagents

- Purified genomic DNA (e.g., extracted using a kit from Table 1)

- Selected Library Preparation Kit (e.g., from Table 2)

- Magnetic stand suitable for 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes

- Freshly prepared 80% ethanol

- Nuclease-free water

- Agarose gel equipment or bioanalyzer

- Library quantification kit (qPCR-based recommended)

Step-by-Step Procedure

DNA Fragmentation and Size Selection

- Mechanical Method: Fragment DNA using an acoustic shearer according to the manufacturer's instructions. Optimize the shearing time to achieve the desired fragment size distribution (e.g., 200-500 bp for whole-genome sequencing).

- Enzymatic Method: If using an enzymatic fragmentation kit, combine DNA with the fragmentation enzyme mix in a single tube. Incubate at the recommended temperature and time to achieve tunable fragment sizes [19].

- Clean-up and Size Selection: Purify the fragmented DNA using size selection beads. Adjust the bead-to-sample ratio to selectively bind fragments within the desired size range. Elute in nuclease-free water [17].

End Repair and dA-Tailing

- Combine the fragmented DNA with end repair and dA-tailing master mix. This step creates blunt-ended, 5'-phosphorylated fragments with a single 'A' overhang at the 3' ends, preparing them for adapter ligation [19].

- Incubate in a thermal cycler according to the kit specifications. Some advanced kits combine fragmentation, end repair, and dA-tailing into a single reaction to minimize handling and bias [14].

Adapter Ligation

- Add sequencing adapters containing platform-specific sequences and sample indexes (barcodes) to the 'A'-tailed fragments. Using Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) is critical for accurate sample multiplexing and to prevent index hopping errors [14].

- Incubate the ligation reaction to allow the adapters to ligate to the insert DNA. Using high-efficiency ligation enzymes can minimize the number of PCR cycles needed later [14].

Library Amplification and Clean-up

- If amplification is required, perform a limited-cycle PCR to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments. Use a polymerase known to minimize amplification bias [17]. The goal is to maximize library complexity while minimizing PCR duplicates. Reduce PCR cycles as much as possible (e.g., 4-10 cycles) based on input DNA [14].

- Perform a final clean-up using magnetic beads to remove excess primers, enzymes, and adapter dimers. Elute the purified library in nuclease-free water or the provided elution buffer.

Quality Control and Quantification

- Fragment Analysis: Assess the library's size distribution and profile using an agarose gel or, preferably, a bioanalyzer/fragment analyzer. The optimal library size is application-dependent [17].

- Accurate Quantification: Quantify the final library concentration using a qPCR-based method. This method is highly sensitive and specifically quantifies fragments that have functional adapters on both ends, ensuring accurate loading on the sequencer. Avoid over- or underestimating concentration, as both can lead to poor sequencing performance and data quality [14].

The path from nucleic acid extraction to a finalized sequencing library is a multi-step process where each component—the extraction method, the library preparation kit, and the enzymatic treatments—plays a vital role in determining the quality, accuracy, and reliability of the resulting NGS data. For chemogenomic research, where discerning true biological signals from noise is essential, adopting strategies to minimize bias (such as using UMIs, reducing PCR cycles, and selecting appropriate kits) is non-negotiable. By following optimized protocols, utilizing the tools and reagents outlined in this guide, and adhering to rigorous quality control, researchers can ensure that their library preparation workflow provides a solid foundation for robust and meaningful chemogenomic discovery.

The field of chemogenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is undergoing a transformative shift driven by three interconnected technological pillars: advanced automation, sophisticated microfluidics, and high-resolution single-cell analysis. This convergence is directly addressing the core challenge of chemogenomics—understanding the complex interactions between chemical compounds and genomic targets—by enabling the creation of enriched, complex, and information-rich libraries from minimal input material. The integration of these technologies allows researchers to move beyond bulk cell analysis, uncovering heterogeneous cellular responses to compounds and enabling the discovery of novel drug targets with unprecedented precision. These shifts are not merely incremental improvements but represent foundational changes in how NGS library preparation is conceptualized and implemented for drug discovery applications.

The Technological Landscape: Quantitative Market and Adoption Trends

The adoption of automated, microfluidics-enabled single-cell technologies is reflected in the rapidly evolving NGS library preparation market. This growth is quantified by recent market analysis and demonstrates the strategic direction of the field.

Table 1: Key Market Trends in NGS Library Preparation (2025-2034)

| Trend Category | Specific Metric | 2024/2025 Status | Projected Growth & Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market | Global Market Size | USD 2.07 billion (2025) | USD 6.44 billion by 2034 (CAGR 13.47%) [10] |

| Automation Shift | Automated Preparation Segment | - | Fastest growing segment (CAGR 14%) [10] |

| Product Trends | Library Preparation Kits | 50% market share (2024) | Dominant product type [10] |

| Automation Instruments | - | Rapid growth (13% CAGR) driven by high-throughput demand [10] | |

| Regional Adoption | North America | 44% market share (2024) | Largest market [10] |

| Asia-Pacific | - | Fastest growing region (CAGR 15%) [10] | |

| Technology Platform | Illumina Kits | 45% market share (2024) | Broad compatibility and high accuracy [10] |

| Oxford Nanopore | - | Rapid growth (14% CAGR) for real-time, long-read sequencing [10] |

The data demonstrates a clear industry-wide shift toward automated, high-throughput solutions. The rapid growth of the automated preparation segment, at a 14% compound annual growth rate (CAGR), significantly outpaces the overall market, indicating a strategic prioritization of workflow efficiency and reproducibility [10]. This is further reinforced by the expansion of the automation instruments segment, as labs invest in hardware to enable large-scale genomics projects. The dominance of library preparation kits underscores their central, enabling role in modern NGS workflows. Regionally, the accelerated growth in the Asia-Pacific market suggests a broader, global dissemination of these advanced technologies beyond established research hubs [10].

Core Protocol 1: High-Throughput Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Compound Response Profiling

This protocol details the use of droplet-based microfluidics to capture transcriptomic heterogeneity in cell populations treated with chemogenomic library compounds, enabling the identification of distinct cellular subtypes and their specific response pathways.

Application Note

This method is designed for the unbiased profiling of cellular responses to chemical perturbations at single-cell resolution. It is particularly valuable in chemogenomics for identifying rare, resistant cell subpopulations, understanding mechanism-of-action, and discovering novel biomarker signatures of compound efficacy or toxicity. The protocol leverages microfluidic encapsulation to enable the parallel processing of thousands of cells, making it feasible to detect low-frequency events and build a comprehensive picture of a compound's transcriptional impact [24] [25].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete single-cell RNA sequencing workflow, from cell preparation to data analysis.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Compound Treatment

- Procedure: Prepare a single-cell suspension from your model system (e.g., cell line, primary cells). Treat cells with the chemogenomic compound(s) of interest at appropriate concentrations and time points. Include a DMSO or vehicle control.

- Critical Parameters: Cell viability must exceed 90% before loading onto the microfluidic device. Use viability dyes (e.g., Propidium Iodide) for accurate assessment. Optimize cell density to achieve a target capture of 5,000-10,000 cells per run [24] [26].

Step 2: Microfluidic Single-Cell Isolation and Barcoding

- Procedure: Load the single-cell suspension, reverse transcription reagents, and barcoded gel beads onto a commercial droplet-based system (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium). Run the instrument to co-encapsulate single cells with a single barcoded bead in a water-in-oil emulsion droplet [25] [26].

- Critical Parameters: The cell concentration should be titrated to maximize the percentage of droplets containing exactly one cell and one bead, minimizing doublets and empty droplets. The Poisson distribution dictates that a concentration yielding ~10% cell-containing droplets is often optimal [25].

Step 3: Cell Lysis and Reverse Transcription

- Procedure: Within each droplet, the cell membrane is lysed upon contact with the bead. The poly-T oligonucleotides on the beads capture poly-A mRNA molecules. The reverse transcription reaction occurs inside the droplet, producing barcoded, cell-specific cDNA [24] [25].

- Critical Parameters: Ensure the oil and surfactant system is stable to prevent droplet coalescence or breakdown, which leads to cross-contamination [25].

Step 4: cDNA Amplification and NGS Library Preparation

- Procedure: Break the emulsion and pool the barcoded cDNA. Amplify the cDNA via PCR. Subsequently, construct the sequencing library by fragmenting the cDNA, adding adapters, and performing a final index PCR.

- Critical Parameters: Minimize PCR cycle numbers to reduce amplification bias. Use library quantification methods like qPCR for accurate sizing and molarity determination before sequencing [17].

Step 5: Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Procedure: Sequence the libraries on an appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina). Use a standardized bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., Cell Ranger) for demultiplexing, alignment, and UMI counting. Perform downstream analysis (clustering, differential expression) using tools like Seurat or Scanpy [27].

- Critical Parameters: Sequence to a sufficient depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per cell) to confidently detect both highly and lowly expressed genes. Carefully filter data based on metrics like genes per cell, UMIs per cell, and mitochondrial read percentage to remove low-quality cells and doublets [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Droplet-Based scRNA-seq

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell 3' Gel Bead Kit | Contains barcoded oligo-dT gel beads for mRNA capture and cellular barcoding. | The core reagent for partitioning and barcoding; essential for multiplexing [10]. |

| Partitioning Oil & Reagent Kit | Forms stable water-in-oil emulsion for nanoscale reactions. | Stability is critical to prevent cross-contamination between cells [25]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Synthesizes cDNA from captured mRNA templates inside droplets. | High-processivity enzymes improve cDNA yield from low-input RNA [17]. |

| SPRIselect Beads | Perform post-RT cleanup and size selection for library preparation. | Used for efficient purification and removal of enzymes, primers, and short fragments [17]. |

| Dual Index Kit | Adds sample-specific indexes during library amplification. | Allows for multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing lane [17]. |

Core Protocol 2: Automated, Low-Input NGS Library Preparation for Chemogenomic Screens

This protocol describes an automated, microplate-based workflow for preparing sequencing libraries from limited samples, such as cells sorted from specific populations after a chemogenomic screen or material from microfluidic chambers.

Application Note

Automation in NGS library preparation is critical for ensuring reproducibility, scalability, and throughput in chemogenomic research, where screens often involve hundreds of samples. This protocol minimizes human error and inter-sample variability while enabling the processing of low-input samples that are typical in functional genomics follow-up experiments [17] [10]. The integration of microfluidics or liquid handling in a plate-based format is a key enabler of this shift.

Experimental Workflow

The automated library preparation workflow is a sequential process managed by a robotic liquid handler.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Automated Nucleic Acid Normalization and Fragmentation

- Procedure: Use a robotic liquid handler (e.g., from Hamilton, Agilent, or Beckman) to transfer and normalize the input DNA or RNA to a defined volume and concentration in a 96-well or 384-well microplate. For DNA, proceed with enzymatic or acoustic shearing. For RNA, proceed with fragmentation during cDNA synthesis.

- Critical Parameters: Ensure the liquid handler is calibrated for precise nanoliter-volume dispensing. Use a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) for accurate quantification of low-concentration samples over spectrophotometry [17].

Step 2: Robotic Adapter Ligation and Cleanup

- Procedure: The liquid handler adds sequencing adapters, along with ligation master mix, to the fragmented DNA. For RNA libraries, it adds adapters during the cDNA synthesis step. Following incubation, the system performs a magnetic bead-based cleanup (e.g., using SPRI beads) to remove excess adapters and reagents.

- Critical Parameters: Efficient A-tailing of DNA fragments is crucial for successful adapter ligation and preventing chimera formation [17]. The bead-to-sample ratio must be precisely controlled by the robot for consistent size selection and yield across all wells.

Step 3: Library Amplification and Indexing

- Procedure: The robot adds a PCR master mix containing primers with unique dual indexes (UDIs) to each well. The PCR enriches for adapter-ligated fragments and adds the sample indexes.

- Critical Parameters: Use a high-fidelity, low-bias polymerase. Limit the number of PCR cycles to the minimum required to generate sufficient material for sequencing to avoid skewing representation and introducing duplicate reads [17].

Step 4: Quality Control and Pooling

- Procedure: The automated system can aliquot a small volume from each well for quality control. After QC validation, it pools equal volumes or masses of each indexed library into a single tube for sequencing.

- Critical Parameters: Automated QC systems (e.g., Fragment Analyzer or TapeStation) can be integrated. Normalize libraries based on qPCR quantification for the most accurate pooling, as it measures amplifiable library fragments rather than total DNA [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Automated NGS Library Prep

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lyophilized NGS Library Prep Kit | Pre-dispensed, room-temperature-stable enzymes and buffers. | Eliminates cold-chain shipping and freezer storage; ideal for automation and improving reproducibility [10]. |

| Magnetic SPRI Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization beads for nucleic acid purification and size selection. | The backbone of automated cleanup steps; particle uniformity is key for consistent performance [17]. |

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Plates | Pre-arrayed, unique barcode combinations in a microplate. | Essential for multiplexing many samples while preventing index hopping artifacts [17]. |

| Low-Bias PCR Master Mix | Enzymes and buffers optimized for uniform amplification of diverse sequences. | Critical for maintaining sequence representation in low-input and enriched libraries [17]. |

The integration of automation, microfluidics, and single-cell analysis represents a paradigm shift in the preparation and enrichment of chemogenomic NGS libraries. These protocols provide a framework for leveraging these technological shifts to achieve higher throughput, greater sensitivity, and deeper biological insight. By adopting automated and miniaturized workflows, researchers can overcome the limitations of sample input and scale, while single-cell technologies make it possible to deconvolve the heterogeneous effects of chemical compounds directly within complex biological systems. The strategic implementation of these tools will be a key determinant of success in future drug discovery and functional genomics research.

Aligning Library Preparation Strategies with Chemogenomic Research Objectives

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics, becoming an indispensable tool in both research and clinical diagnostics. Within the field of chemogenomics—which utilizes phenotypic profiling of biological systems under chemical or environmental perturbations to identify gene functions and map biological pathways—the initial sample and library preparation steps are particularly critical. The quality of library preparation directly influences the accuracy and reliability of downstream sequencing data, which in turn affects the ability to draw meaningful biological conclusions from chemogenomic screens. These screens systematically measure phenotypes such as microbial fitness, biofilm formation, and colony morphology to establish functional links between genetic perturbations and chemical conditions [28].

The process of preparing a sequencing library involves transforming extracted nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) into a format compatible with NGS platforms through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and optional amplification [17] [29]. In chemogenomic research, the choice between different library preparation strategies—such as metagenomic NGS (mNGS), amplification-based targeted NGS (tNGS), and capture-based tNGS—must be carefully aligned with the specific experimental objectives, whether for pathogen identification in infectious disease models, variant discovery in antimicrobial resistance genes, or comprehensive functional annotation [30]. Recent advancements have seen these methods become more efficient, accurate, and adaptable, enabling researchers to customize workflows based on project size, scope, and desired outcomes [31] [32].

Key Library Preparation Methods and Their Strategic Selection

Selecting the appropriate library preparation method is a foundational decision in chemogenomic research. The three primary approaches offer distinct advantages and are suited to different experimental goals. Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) provides a hypothesis-free, comprehensive sequencing of all nucleic acids in a sample, making it ideal for discovering novel or unexpected pathogens. In contrast, targeted NGS (tNGS) methods enrich specific genomic regions of interest prior to sequencing, thereby increasing sensitivity and reducing costs for focused applications. Targeted approaches primarily branch into two methodologies: capture-based tNGS, which uses probes to hybridize and pull down target sequences, and amplification-based tNGS, which employs multiplex PCR to amplify specific targets [30].

The strategic selection among these methods involves careful consideration of several factors. mNGS is particularly valuable when the target pathogens are unknown or when a broad, unbiased overview of the microbial community is required. However, this comprehensive approach comes with higher costs and longer turnaround times. Targeted methods, while requiring prior knowledge of the targets, offer significantly higher sensitivity for detecting low-abundance pathogens and can be more cost-effective for large-scale screening studies. Each method exhibits different performance characteristics in terms of sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, and cost, making them suited to different phases of chemogenomic research [30].

Comparative Performance of NGS Methods

A recent comparative study of 205 patients with suspected lower respiratory tract infections provided quantitative insights into the performance characteristics of these three NGS methods, offering evidence-based guidance for method selection in infectious disease applications of chemogenomics [30].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of NGS Methods in Pathogen Detection

| Method | Total Species Identified | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity for DNA Viruses (%) | Cost (USD) | Turnaround Time (Hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) | 80 | N/A | N/A | N/A | $840 | 20 |

| Capture-based tNGS | 71 | 93.17 | 99.43 | 74.78 | N/A | N/A |

| Amplification-based tNGS | 65 | N/A | N/A | 98.25 | N/A | N/A |

Note: N/A indicates data not available in the cited study [30].

The data reveals that capture-based tNGS demonstrated the highest overall diagnostic performance with exceptional sensitivity, making it suitable for routine diagnostic testing where detecting the presence of pathogens is critical. Amplification-based tNGS showed superior specificity for DNA viruses, making it valuable in scenarios where false positives must be minimized. However, it exhibited poor sensitivity for both gram-positive (40.23%) and gram-negative bacteria (71.74%), limiting its application in comprehensive bacterial detection. Meanwhile, mNGS identified the broadest range of species, confirming its utility for detecting rare or unexpected pathogens, albeit at a higher cost and longer turnaround time [30].

Experimental Protocols for Chemogenomic Applications

Protocol for Metagenomic NGS (mNGS) Library Preparation

The mNGS approach provides an unbiased survey of all microorganisms in a sample, making it particularly valuable for chemogenomic studies aimed at discovering novel microbial responses to chemical compounds or identifying unculturable organisms. The following protocol is adapted from methodologies used in lower respiratory infection studies [30]: