Addressing Sequencing Errors in Chemogenomic Variant Calling: Strategies for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Accurate variant calling is foundational for discovering genetic biomarkers of drug response in chemogenomics.

Addressing Sequencing Errors in Chemogenomic Variant Calling: Strategies for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

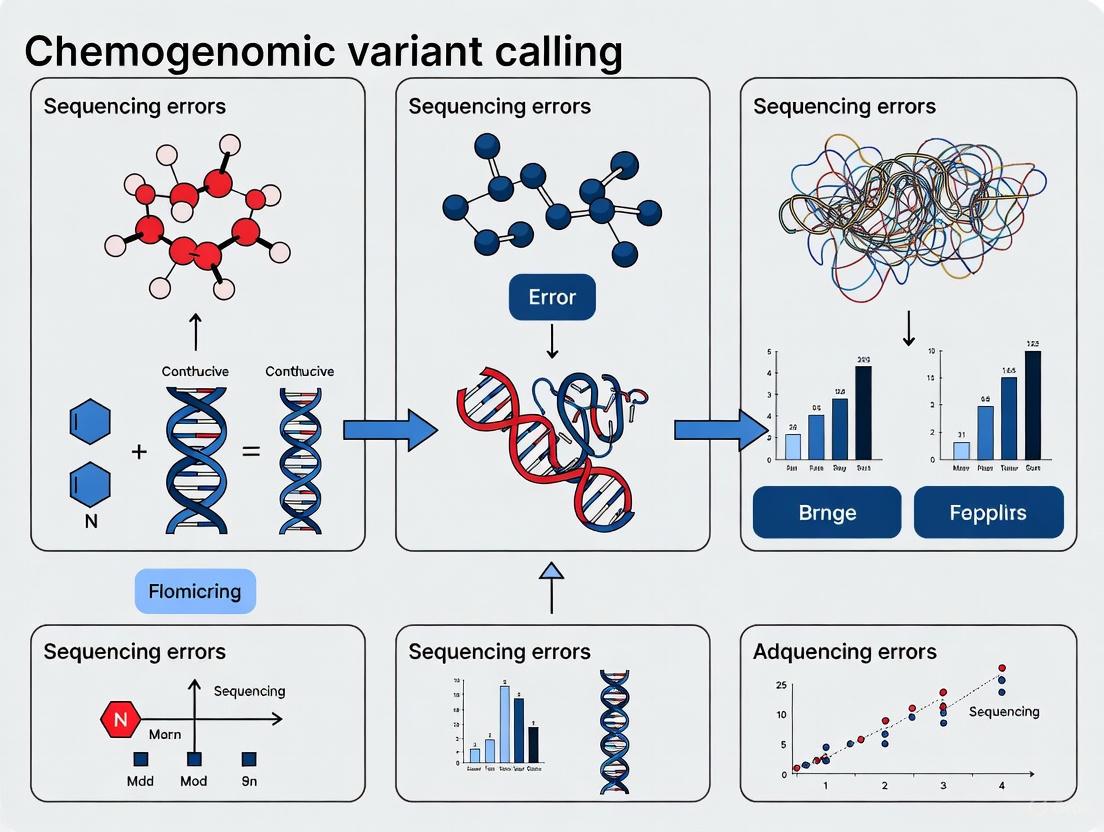

Accurate variant calling is foundational for discovering genetic biomarkers of drug response in chemogenomics. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address sequencing errors, which can obscure true signal and compromise discovery. We explore the foundational sources of error across different sequencing technologies and genomic contexts, detail best-practice methodologies and emerging machine-learning tools for error mitigation, present advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenging genomic regions, and finally, establish rigorous validation and benchmarking practices to ensure variant call reliability for downstream clinical application.

Understanding the Landscape of Sequencing Errors in Chemogenomics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the concrete impact of a variant calling error on the discovery of a chemogenomic biomarker?

A variant calling error can directly prevent the identification of a true biomarker or lead to the validation of a false one. This has a cascading effect on downstream research and clinical applications [1] [2]. In precise terms, the impact includes:

- False Positives/Negatives in Biomarker Identification: Errors can cause a genuine variant to be missed (false negative) or a non-existent variant to be reported (false positive). This corrupts the dataset used to establish correlations between genetic variants and drug response [3].

- Inaccurate Patient Stratification: Biomarkers are often used to stratify patients for targeted therapies. An error in calling a key variant can misclassify a patient, potentially leading to the administration of an ineffective treatment or the exclusion from a beneficial one [2] [4]. For example, in HIV treatment, specific errors in the V3 loop sequence can lead to incorrect prediction of co-receptor tropism, directly impacting the recommendation for entry inhibitor drugs like Maraviroc [2].

- Compromised Drug Discovery and Development: In chemogenomics, the goal is to link genetic markers to drug efficacy or toxicity. Variant calling errors in research datasets can derail this process by obscuring true relationships, leading to failed clinical trials and wasted resources [1] [5].

FAQ 2: My NGS data contains sequences with ambiguous bases ('N'). What is the best strategy to handle them for a reliable analysis?

The optimal strategy depends on the number and location of ambiguities and your specific research goal. A comparative analysis of error-handling strategies provides the following guidance [2]:

- Use the "Neglection" strategy when ambiguities are few and randomly distributed, as this strategy simply removes sequences containing ambiguities from the analysis. It outperforms other methods when no systematic errors are present.

- Employ the "Deconvolution with a majority vote" strategy when a significant fraction of your reads contains ambiguities or when errors are suspected to be non-random. This method is computationally expensive but more robust in the face of systematic errors. It resolves all possible sequences from the ambiguous one, makes predictions for each, and takes the majority vote as the final call.

- Avoid the "Worst-case assumption" strategy for general use. This study found it performs worse than both neglection and deconvolution, as it can lead to overly conservative predictions that exclude patients from potentially beneficial treatments [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Error Handling Strategies for Ambiguous Bases in NGS Data

| Strategy | Method | Best Use Case | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neglection | Removes sequences with ambiguities from analysis. | Few, random errors; no systematic bias. | Can introduce bias if errors are systematic, leading to data loss. |

| Deconvolution with Majority Vote | Resolves ambiguities into all possible sequences; the most frequent prediction is used. | Many ambiguities or suspected systematic errors. | Computationally expensive with multiple ambiguous positions (complexity: (4^k)). |

| Worst-Case Assumption | Assumes the ambiguity represents the variant with the worst therapeutic outcome. | Generally not recommended. | Leads to overly conservative therapy recommendations and excludes patients from treatment. |

FAQ 3: Which variant calling tool should I choose for my chemogenomics project?

There is no single "best" tool; the choice depends on your sequencing technology and research objective. The trend is moving from traditional statistical models to AI-based tools, which offer higher accuracy, especially in complex genomic regions [3]. Many studies advocate for a multi-caller approach to increase confidence [6].

Table 2: Selection Guide for AI-Based Variant Calling Tools

| Tool | Best For | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant | Short- and long-read (PacBio HiFi, ONT) data; large-scale studies. | High accuracy; uses deep learning on pileup images. | High computational cost. |

| DeepTrio | Family trio data (child and parents). | Improves accuracy by leveraging familial genetic context. | Specific to trio study designs. |

| DNAscope | Efficient processing of large datasets. | High speed and accuracy, reduced computational cost. | Based on machine learning, not deep learning. |

| Clair/Clair3 | Long-read data; fast and accurate SNP/InDel calling. | High performance, especially at lower coverages. | Earlier versions struggled with multi-allelic variants. |

| Medaka | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) long-read data. | Designed specifically for ONT data. | Specialized to one technology. |

FAQ 4: How can I improve accuracy when detecting somatic structural variants (SVs) in cancer research?

Somatic SVs are key drivers of cancer but are challenging to detect accurately. Benchmarking studies suggest that combining multiple specialized tools into a single pipeline significantly enhances the detection of true somatic SVs [6]. A robust workflow involves:

- Using multiple SV callers (e.g., Sniffles, cuteSV, Delly) on your tumor and matched normal samples.

- Merging and comparing the resulting VCF files to identify candidate somatic SVs present in the tumor but absent in the normal sample.

- Leveraging a truth set (like the COLO829 melanoma cell line) for validation and benchmarking your pipeline's performance [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a proven somatic SV detection pipeline:

FAQ 5: How is the field moving beyond genomics to improve biomarker discovery?

The field is rapidly evolving towards integrative multi-omics approaches [1] [7]. While genomics is crucial, it is now recognized that layering additional data provides a more complete picture of disease biology and drug response. The current paradigm shift includes:

- Integration of Proteomics, Transcriptomics, and Metabolomics: This helps capture the functional effects of genetic variants, moving beyond static DNA sequences to dynamic biological activity [1] [7].

- Spatial Biology and Single-Cell Analysis: These technologies allow researchers to see where biological processes happen within a tissue and to analyze cellular heterogeneity, which bulk sequencing can miss [7].

- Liquid Biopsy and Novel Biomarkers: The use of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from blood is a minimally invasive method for cancer diagnosis and monitoring. New approaches, like neomers (short DNA sequences absent in healthy genomes but created by tumor mutations), show high accuracy in detecting early-stage cancers [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Variant Calling and Biomarker Discovery

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| GRCh38 Reference Genome | The baseline human genome sequence for aligning sequencing reads and calling variants. | Used as the standard reference in genomic studies [8]. |

| Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) Extraction Kits | To isolate circulating DNA from blood plasma for liquid biopsy applications. | Crucial for non-invasive cancer detection and monitoring studies [8]. |

| AI-Based Variant Callers | Software to identify genetic variants from sequenced reads with high accuracy. | E.g., DeepVariant, DNAscope, Clair3 [3]. |

| SURVIVOR | A tool to simulate, manipulate, and compare structural variants from multiple VCF files. | Used for merging VCFs and identifying somatic SVs in pipeline approaches [6]. |

| Nullomer/Neomer Database | A curated set of DNA sequences absent from the reference human genome. | Serves as a basis for detecting cancer-specific mutations; used as a novel biomarker [8]. |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) | A high-performance visualization tool for interactive exploration of large genomic datasets. | Used for manual validation of variant calls, such as inspecting BAM files for somatic SVs [6]. |

FAQs: Understanding Sequencing Platform Errors

What are the most common types of errors introduced by Illumina, PacBio, and Oxford Nanopore sequencing?

Each major sequencing platform has a distinct error profile rooted in its underlying technology. The table below summarizes the primary characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Error Profiles of Major Sequencing Platforms

| Sequencing Platform | Primary Error Type | Typical Raw Read Accuracy | Most Common Error Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Low stochastic error rate [9] | >99.9% (Q30) [9] | Cluster generation failures; Base substitution errors [10] |

| PacBio (HiFi mode) | Stochastic errors (reduced via consensus) [11] | >99.9% (Q30) from circular consensus [12] [13] | Small insertions/deletions; Fluorescence signal misinterpretation [11] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Systematic errors [11] | ~99.5% - 99.8%+ (Q20-Q26+) [14] | Deletions in homopolymer regions; Errors in methylation motifs (e.g., Dcm, Dam sites) [15] [16] |

How do errors from different platforms impact variant calling in chemogenomic research?

Inaccurate variant calling can directly lead to false conclusions in chemogenomic studies.

- False Positives/Negatives: Elevated error rates can cause misreports (false positives) or missed reports (false negatives) of genomic variants. This is particularly critical in cancer genomics or rare disease research, where an error could lead to misidentifying a pathogenic mutation [11].

- Bias in Transcriptome Analysis: Errors can affect the identification of alternative splicing events and RNA modifications, potentially misleading the understanding of gene regulation mechanisms in response to chemical compounds [11].

Can these systematic errors be corrected, and what are the recommended strategies?

Yes, platform-specific error correction strategies are essential for generating reliable data.

- Illumina: The primary approach is rigorous experimental design and library quality control to prevent issues like overclustering or underclustering that cause cycle 1 imaging failures [10].

- PacBio: Employ the HiFi (Circular Consensus Sequencing) mode. This mode sequences the same DNA molecule multiple times to generate a highly accurate consensus read, effectively reducing stochastic errors [11] [12].

- Oxford Nanopore: A multi-faceted approach is best:

- Hardware: Use the R10.4.1 flow cell, which has a dual reader head that improves accuracy in homopolymer regions [11] [14].

- Basecalling: Use the most accurate basecalling models, such as Super Accuracy (SUP) [14].

- Bioinformatics: Generate consensus sequences from high-depth data (>50x coverage) using tools like Medaka to correct systematic errors [11] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Illumina: Troubleshooting Cycle 1 Imaging Errors

Cycle 1 errors (e.g., "Best focus not found") indicate the instrument could not calculate the focal point due to insufficient cluster intensity [10].

Detailed Protocol for Diagnosis and Resolution:

Run Instrument System Check:

- Perform a post-run wash as prompted.

- Power cycle the instrument.

- Navigate to

Manage Instrumentand selectSystem Check. - Select all motion tests, prime reagent lines, and both thermal ramping and volume tests.

- If any test fails (except the PR2 position in the volume test), contact Illumina Technical Support [10].

Inspect Library and Reagents:

- Check reagent kits for expiration dates and proper storage conditions.

- Verify library quality and quantity using Illumina-recommended methods (e.g., fluorometric quantification). Avoid photometric measurements which often overestimate concentration [16].

- Confirm that a fresh dilution of NaOH was used and that its pH is above 12.5 [10].

Execute a Control Experiment:

- If no issues are apparent, repeat the run with a 20% PhiX control spike-in. The PhiX acts as a positive control for clustering.

- If the run again fails at cycle 1, this indicates an underlying library issue. If it proceeds, the problem was likely with the original library [10].

Oxford Nanopore: Resolving Homopolymer and Methylation Site Errors

Systematic errors in homopolymers and methylation sites are a well-documented characteristic of Nanopore data and require specific bioinformatic polishing [15] [16].

Detailed Protocol for Error Correction:

Basecalling and Initial Assembly:

- Perform basecalling using the Dorado basecaller with a Super Accuracy (SUP) model to achieve the highest raw read accuracy [14].

- Assemble the most abundant sequence from your data using a long-read assembler.

Bioinformatic Polishing:

- Polish the initial assembly using a methylation-aware algorithm. These algorithms are trained on datasets containing common methylation motifs (e.g., Dam: Gm6ATC; Dcm: C5mCTGG or C5mCAGG) and can correct systematic errors at these sites [15].

- For homopolymer-related indels, manual inspection and correction may be necessary, informed by the knowledge that homopolymers longer than 9 bases are often truncated by a base or two [15].

Validation and Confidence Assessment:

- Map your raw reads back to the polished consensus sequence.

- Use a variant calling strategy to identify positions with lower confidence. In challenging regions (homopolymers, methylation sites), different nucleotides may be called at the same position in the raw reads even if the assembled base is correct [16].

- Report these positions as "lower confidence" in your final results.

PacBio: Mitigating Stochastic Errors for High-Fidelity Variant Calling

While PacBio HiFi reads are highly accurate, the initial single-pass reads have a higher error rate that is corrected via circular consensus [11].

Detailed Protocol for Generating High-Accuracy Data:

Library Preparation for HiFi Sequencing:

Data Generation and Processing:

- Sequence the library on a PacBio Sequel II/IIe system. The instrument will perform multiple passes on each molecule [13].

- Process the data using the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) algorithm. This algorithm generates a highly accurate HiFi read from the multiple sub-reads of a single molecule, effectively averaging out the stochastic errors [11] [12].

Data Validation:

- For the highest reliability in critical applications like clinical variant calling, consider a hybrid approach. Integrate PacBio long-read data with Illumina short-read data for hybrid assembly, which can further enhance data reliability by cross-validating variants [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Sequencing and Error Mitigation

| Item Name | Function / Application | Platform |

|---|---|---|

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | Prepares genomic DNA for PacBio sequencing, forming the circular template essential for HiFi read generation [12]. | PacBio |

| ONT 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-16S114.24) | Used for full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification and barcoding in microbiome studies [9]. | Oxford Nanopore |

| QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel | Targets and amplifies specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) for Illumina-based 16S rRNA sequencing [9]. | Illumina |

| PhiX Control Kit | Serves as a positive control for cluster generation and sequencing; vital for spiking-in to troubleshoot failed runs [10]. | Illumina |

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit | Optimized for DNA extraction from complex samples like soil or gut microbiota, critical for accurate microbiome profiling [12]. | All Platforms |

| Dorado Basecaller (SUP model) | Software tool for converting raw Nanopore current signals into nucleotide sequences with the highest accuracy (Super Accuracy) [14]. | Oxford Nanopore |

Experimental Workflow for Systematic Error Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for characterizing and mitigating technology-specific errors, applicable to chemogenomic research.

Workflow for Sequencing Error Analysis

Workflow for Comparative Platform Evaluation

For studies aiming to directly compare the performance of multiple sequencing platforms, the following workflow is recommended.

Comparative Platform Evaluation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Homopolymers

Q1: What are homopolymers and why are they problematic for sequencing? Homopolymers (HPs) are sequences consisting of consecutive identical bases (e.g., "AAAAA" or "CCCCC"). They are present throughout the human genome, with over 1.43 million identified, most being short sequences (4-6 mers) [17]. They are problematic because they induce false insertion/deletion (indel) and substitution errors during sequencing. The accuracy of detecting the correct length of a homopolymer decreases significantly as the length of the homopolymer increases [17].

Q2: Which sequencing technologies perform best in homopolymeric regions? Performance varies by platform. One study found that the MGISEQ-2000 (tetrachromatic fluorogenic platform) and NextSeq 2000 (dichromatic fluorogenic platform) showed highly comparable performance for HP sequencing [17]. Furthermore, for bacterial variant calling, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) with deep learning-based tools like Clair3 have been shown to achieve high accuracy in indel calling, challenging the historical limitation of ONT in homopolymer-rich regions [18].

Q3: What wet-lab method can improve variant detection in homopolymers? Incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) into your library preparation protocol significantly improves performance. One study demonstrated that with a UMI-based bioinformatics pipeline, there were no differences between detected and expected variant frequencies for any homopolymers tested, except for poly-G 8-mers on one specific platform [17].

Segmental Duplications

Q4: What are segmental duplications and what challenges do they pose? Segmental duplications (SDs) are large, highly similar duplicated blocks of genomic DNA, typically ranging from 1 to 200 kilobases [19]. They comprise approximately 3.6% of the human genome and are dramatically enriched in pericentromeric and subtelomeric regions [19]. Their high sequence similarity causes misassembly, misassignment, and decreased sequencing coverage, making accurate mapping and variant detection nearly impossible with short-read technologies [19] [20].

Q5: How can I accurately call variants in medically relevant genes within segmental duplications? A powerful method involves using HiFi long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) paired with the informatics tool Paraphase [20]. This combination allows for high-precision variant detection and copy number analysis by phasing haplotypes across paralogous gene families. This approach has been successfully used to genotype complex genes like those for spinal muscular atrophy (SMN1/SMN2) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CYP21A2) [20].

Low-Complexity Regions

Q6: What are Low-Complexity Regions (LCRs) in a genomic context? Low-Complexity Regions (LCRs) are segments of a genome or protein sequence characterized by a low diversity of nucleotides or amino acids [21]. In proteins, these are often considered disordered fragments, though they can play important functional roles [21].

Q7: How can I identify and mask LCRs in my sequencing data? You can use tools like the "Mask Low-Complexity Regions" function available in bioinformatics suites (e.g., CLC Genomics Machine). This tool uses a sliding window approach across the sequence. You can set parameters like window size, window stride (how many nucleotides the window moves each step), and a low-complexity threshold to identify and then mask these regions by replacing bases with 'N's or by annotating the sequence [22].

General Troubleshooting

Q8: My variant calling has unexpected errors. How can I estimate my sample-specific error rate? You can use family data (parent-offspring trios) to estimate sequencing error rates. Methods have been developed that use Mendelian errors observed in family data to predict the overall precision and recall of variant calls for each sample using Poisson regression. This provides a highly granular error estimate tailored to your specific data, regardless of the sequencing platform or variant-calling methodology used [23].

Q9: How can I predict where my variant calling pipeline is likely to fail? StratoMod is an interpretable machine learning classifier (using Explainable Boosting Machines) that predicts germline variant calling errors based on genomic context [24]. It can predict both precision and recall for a given method, allowing you to identify variants in challenging contexts (like difficult-to-map regions or homopolymers) that are likely to be false positives or false negatives [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Indel Error Rates in Homopolymeric Regions

Problem: Your variant calls in homopolymeric regions show an elevated number of false insertion/deletion errors.

Solution: Implement a wet-lab and bioinformatics protocol utilizing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs).

Experimental Protocol (Based on [17]):

- Library Preparation with UMIs: Use a library prep kit that incorporates UMIs. These are short, random oligonucleotide sequences that are added to each original DNA molecule before PCR amplification.

- Sequencing: Sequence your samples on your chosen NGS platform. The study indicates that MGISEQ-2000 and NextSeq 2000 show comparable performance for HP sequencing [17].

- Bioinformatic Processing with UMI Pipeline:

- Cluster Reads: After sequencing, bioinformatically group reads that originate from the same original DNA molecule by identifying reads sharing the same UMI.

- Consensus Building: Generate a consensus sequence for each group of UMI-clustered reads. This process effectively corrects for random errors introduced during PCR amplification and sequencing.

- Variant Calling: Perform variant calling on the consensus-read BAM file rather than the raw read BAM file.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this error-correction process:

Diagram: UMI-Based Error Correction Workflow

Issue 2: Inability to Call Variants in Segmental Duplications

Problem: You cannot accurately call variants in genes located within segmental duplications (e.g., SMN1, CYP21A2), leading to false positives/negatives and an inability to determine accurate copy number.

Solution: Employ HiFi long-read sequencing and the Paraphase computational tool.

Experimental Protocol (Based on [20]):

- DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight DNA extraction protocols to preserve long DNA fragments.

- HiFi Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare a library for PacBio HiFi sequencing. HiFi reads provide the combination of long read lengths (typically >10 kb) and high single-read accuracy (>99%) required to span and accurately sequence within highly similar duplicated regions.

- Variant Calling with Paraphase:

- Perform a genome-wide run of Paraphase on the HiFi read data.

- Paraphase resolves haplotypes by phasing reads across the entire paralogous gene family, distinguishing between the highly similar copies.

- The output provides phased variants and precise copy number for each gene in the segmental duplication.

The analysis process for resolving complex duplications is shown below:

Diagram: Resolving Variants in Segmental Duplications

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Homopolymer Length on Detected Variant Frequency

Data derived from a study using a plasmid with inserted homopolymers sequenced across three NGS platforms. Detected frequencies were compared to the expected frequency (as determined by an internal control mutation T790M). This shows a clear negative correlation between HP length and detection accuracy without UMI correction. [17]

| Homopolymer Length | Nucleotide | Expected Frequency | Average Detected Frequency (MGISEQ-2000) | Average Detected Frequency (NextSeq 2000) | Significant Drop (P<0.01)? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-mer | A, C, G, T | 3% - 60% | ~3% - ~60% | ~3% - ~60% | No |

| 4-mer | A, C, G, T | 3% - 60% | ~3% - ~60% | ~3% - ~60% | No |

| 6-mer | Poly-A | 30% | ~22% | ~24% | Yes (Both platforms) |

| 6-mer | Poly-C | 30% | ~26% | ~28% | Yes (MGISEQ-2000) |

| 8-mer | A, C, G, T | 3% - 60% | Substantially Lower | Substantially Lower | Yes (Nearly all cases) |

Table 2: Performance of Deep Learning Variant Callers on Bacterial ONT Data

This benchmarking study compared variant callers across 14 bacterial species. Clair3 and DeepVariant, both deep learning-based, showed superior performance in handling SNPs and Indels, even in contexts traditionally prone to errors like homopolymers. [18]

| Variant Caller | Type | SNP F1 Score (%) (Simplex-sup) | Indel F1 Score (%) (Simplex-sup) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clair3 | Deep Learning | 99.99 | 99.53 | Highest overall accuracy for SNPs and Indels |

| DeepVariant | Deep Learning | 99.99 | 99.61 | Excellent performance, on par with Clair3 |

| Medaka | Traditional | >99.9 | ~98.5 | Good performance |

| Longshot | Traditional | >99.9 | ~97.5 | Good for SNPs |

| BCFtools | Traditional | ~99.7 | ~85.0 | Lower Indel accuracy |

| FreeBayes | Traditional | ~99.5 | ~80.0 | Lower Indel accuracy |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Wet-lab Reagent | Molecular barcodes for error correction; enables bioinformatic consensus calling to reduce false positives/negatives. | Critical for improving accuracy in homopolymer sequencing and low-frequency variant detection [17]. |

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Sequencing Technology | Long (>10 kb) and highly accurate (>99.9%) reads. | Essential for phasing and accurately mapping reads within segmental duplications and other complex regions [20]. |

| Paraphase | Computational Tool | Informatics tool for haplotype-phasing and variant calling in paralogous gene families. | Resolves genes in segmental duplications (e.g., SMN1, CYP21A2) for accurate SNV and CNV calling [20]. |

| StratoMod | Computational Tool | Interpretable machine learning classifier (EBM) to predict variant calling errors from genomic context. | Pre-emptively identifies variants likely to be false positives/negatives for any pipeline in hard-to-map regions [24]. |

| Clair3 & DeepVariant | Computational Tool | Deep learning-based variant callers trained to recognize patterns in sequencing data. | Superior SNP and Indel accuracy, even in traditionally error-prone contexts like homopolymers (using ONT data) [18]. |

| Mask Low-Complexity Regions Tool | Computational Tool | Identifies and masks low-complexity sequences to prevent erroneous alignment. | Prevents spurious alignments in taxonomic profiling or variant calling by masking simple repeats [22]. |

In chemogenomic variant calling research, the accuracy of final data is highly dependent on the initial pre-analytical steps. Errors introduced during DNA isolation, fragmentation, and PCR amplification can propagate through the entire experimental pipeline, leading to false variant calls and compromised research conclusions. This technical guide addresses the major sources of pre-analytical errors and provides troubleshooting methodologies to ensure data integrity for researchers and drug development professionals.

DNA Isolation and Fragmentation Considerations

DNA Integrity and Purity

FAQ: How does template DNA quality affect my PCR and sequencing results?

Poor DNA integrity and purity are significant contributors to experimental failure and increased error rates. Degraded DNA templates can lead to incomplete amplification and introduce artifacts during sequencing.

- Causes & Recommendations:

- Poor Integrity: Minimize shearing and nicking of DNA during isolation. Evaluate template DNA integrity by gel electrophoresis. Store DNA in molecular-grade water or TE buffer (pH 8.0) to prevent nuclease degradation [25].

- Low Purity: Residual PCR inhibitors such as phenol, EDTA, and proteinase K can severely inhibit polymerase activity. Re-purify DNA or precipitate and wash with 70% ethanol to remove residual salts or ions. For challenging samples (e.g., from blood or soil), choose DNA polymerases with high processivity and inhibitor tolerance [25].

- Insufficient Quantity: Examine the quantity of input DNA and increase the amount if necessary. Choose DNA polymerases with high sensitivity for amplification. If appropriate, increase the number of PCR cycles [25].

Sperm DNA Fragmentation Testing

FAQ: When should DNA fragmentation testing be considered in a clinical or research context?

While not a routine test, DNA fragmentation analysis is an important adjunct in specific scenarios, particularly in reproductive medicine and studies where DNA integrity is paramount. The strongest evidence exists for its use in the following clinical scenarios [26]:

- Presence of varicoceles

- Unexplained infertility

- Recurrent pregnancy loss

- Recurrent IUI/IVF failures

- Patients with a preponderance of lifestyle risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity)

The American Urological Association and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine do not currently recommend routine DNA fragmentation testing for all men with fertility issues due to a lack of validated clinical cut-off points and variable test sensitivity [27].

PCR Amplification and Error Rates

DNA Polymerase Fidelity

FAQ: Which DNA polymerase should I use to minimize PCR errors for cloning applications?

The choice of DNA polymerase is one of the most critical factors in determining PCR error rates. Proofreading polymerases significantly reduce error rates compared to non-proofreading enzymes.

Table 1: Error Rate Comparison of DNA Polymerases [28]

| DNA Polymerase | Published Error Rate (errors/bp/duplication) | Fidelity Relative to Taq | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | ( 1–20 \times 10^{-5} ) | 1x | Standard non-proofreading polymerase |

| AccuPrime-Taq HF | Not Available | ~9x better | High-fidelity version of Taq |

| KOD Hot Start | Not Available | ~4-50x better | High fidelity, thermostable |

| Pfu | ( 1-2 \times 10^{-6} ) | 6–10x better | Proofreading activity |

| Phusion Hot Start | ( 4-9.5 \times 10^{-7} ) | 24->50x better | Very high fidelity, uses HF or GC buffer |

| Pwo | Comparable to Pfu | >10x better | Proofreading activity |

A direct sequencing study of 94 unique DNA targets found that Pfu, Phusion, and Pwo polymerases had the lowest error rates, which were more than 10-fold lower than that observed with Taq polymerase. Error rates were comparable for these three high-fidelity enzymes [28].

PCR Component Optimization

FAQ: How can I optimize my PCR reaction to minimize errors?

- Magnesium Concentration: Review and optimize Mg²⁺ concentration. Excessive concentrations favor misincorporation of nucleotides, while insufficient concentrations can reduce yield. Note that EDTA or high dNTP concentrations can chelate Mg²⁺, requiring higher amounts [25].

- dNTP Concentrations: Ensure equimolar concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. Unbalanced nucleotide concentrations increase the PCR error rate [25].

- Cycle Number: Reduce the number of cycles without drastically lowering the yield. High numbers of cycles increase the incorporation of mismatched nucleotides. Increase the amount of input DNA when appropriate to avoid excessive cycles [25].

Specialized Target Amplification

FAQ: How do I handle complex DNA targets like GC-rich sequences or long amplicons?

- GC-Rich Templates/Targets with Secondary Structures: Use DNA polymerases with high processivity. Incorporate PCR additives or co-solvents (e.g., DMSO, GC Enhancer) to help denature templates. Increase denaturation time and/or temperature [25].

- Long Targets: Verify the amplification length capability of the selected DNA polymerase. Use enzymes specifically designed for long PCR. Prolong the extension time according to amplicon length. Reduce annealing and extension temperatures to aid enzyme thermostability for very long targets [25].

Quantitative Error Analysis and Methodologies

Measuring Error Rates in Next-Generation Sequencing

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) error rates are a composite of errors from sample preparation, library construction, and the sequencing process itself. A systematic study sequencing a single known template on an Illumina platform determined an average error rate of 0.24 ± 0.06% per base, with 6.4 ± 1.24% of sequences containing at least one mutation [29].

Key Experimental Protocol for Error Rate Determination [29]:

- Template: Use a single, known DNA sequence (e.g., a plasmid or synthesized oligo).

- Sample Preparation: Compare different DNA polymerases (e.g., PWO, Taq) for the index-PCR step. Include a control with template synthesized including indices to omit the index-PCR.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina platform to generate millions of reads.

- Data Analysis:

- Align all reads to the reference sequence.

- Calculate the percentage of mutated sequences.

- Calculate the error rate (average mutation per base).

- Analyze mutation frequency per position and mutation spectra (which nucleotides are converted to which).

This study found that phasing effects (pre-phasing and post-phasing) during sequencing-by-synthesis were a major contributor to the observed error rates. The removal of shortened sequences, which are a result of phasing, was necessary to determine the true error rate [29].

Advanced Error Prediction with StratoMod

For advanced variant calling pipelines, machine learning tools like StratoMod can predict errors. StratoMod uses an interpretable machine-learning classifier (Explainable Boosting Machines) to predict germline variant calling errors based on genomic context (e.g., homopolymer regions, difficult-to-map regions) [24]. This allows for a more precise, data-driven assessment of pipeline performance compared to traditional stratification methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for High-Fidelity PCR and Sequencing [28] [25] [29]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases (e.g., Pfu, Phusion, Pwo) | PCR amplification for cloning and sequencing | Select proofreading enzymes for lowest error rates ((10^{-6}) to (10^{-7})). |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | PCR amplification | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer degradation by maintaining inactivity until high-temperature activation. |

| Mg²⁺ Solution (MgCl₂ or MgSO₄) | Cofactor for DNA polymerase | Concentration must be optimized; excess increases misincorporation, insufficient reduces yield. |

| Equimolar dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | Unbalanced concentrations increase error rates. Use high-quality, nuclease-free preparations. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, GC Enhancer) | Amplification of difficult templates | Helps denature GC-rich sequences and resolve secondary structures. Use at lowest effective concentration. |

| Template DNA Purification Kits | Isolation of high-purity DNA | Removes contaminants like phenol, salts, and proteins that inhibit polymerase activity. |

| Molecular-Grade Water or TE Buffer | Resuspension and storage of DNA | Prevents degradation by nucleases; avoids metal ions that can catalyze DNA damage. |

Workflow and Error Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the pre-analytical workflow and the primary error sources discussed in this guide.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Trade-offs

What is the fundamental error-reliability trade-off in variant calling pipelines?

The core trade-off lies between sensitivity (the ability to detect true positive variants, including rare ones) and specificity (the ability to avoid false positives). Standard next-generation sequencing (NGS) has error rates around 0.1% to 1%, which fundamentally limits reliable detection of subclonal variants present in fewer than ~1% of DNA molecules in a sample. Increasing sensitivity to find more true variants often means also capturing more sequencing errors, thereby reducing specificity. Conversely, overly stringent filtering to eliminate false positives increases specificity but risks discarding genuine, low-frequency variants [30].

Which steps in my pipeline are most critical for managing this balance?

The balance is affected at nearly every stage, but several are particularly critical:

- Experimental Design and Library Preparation: Choices here create an upper limit on data quality. PCR amplification can introduce duplicates and errors. Using PCR-free library construction or Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is crucial for accurate detection of low-frequency variants by allowing bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates [30] [31].

- Data Preprocessing and Alignment: This stage should prioritize sensitivity. A balanced preprocessing workflow, such as the GATK best practices pipeline that uses BWA-MEM for alignment and includes steps for duplicate marking and base quality score recalibration (BQSR), is recommended to set a strong foundation for variant calling [31].

- Variant Calling Itself: The choice of algorithm is paramount. Probabilistic methods that perform local reassembly of haplotypes, such as GATK's HaplotypeCaller, generally show superior performance in benchmarking studies because they are better at distinguishing true variants from sequencing artifacts [32] [31].

How does genomic context influence error rates and pipeline performance?

Genomic context is a major contributor to sequencing and variant calling errors. Performance varies significantly depending on the region being sequenced. For instance, homopolymer repeats (stretches of a single base) are challenging for most technologies, and segmental duplications cause mapping ambiguities. Tools like StratoMod use interpretable machine learning to predict the likelihood of missing a variant or calling a false positive based on its specific genomic context (e.g., homopolymer length, local repetition). This allows for more informed pipeline selection; one might choose a long-read technology for segmental duplications and a short-read technology for homopolymer-rich regions [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Excessive False Positive Variant Calls

This occurs when your pipeline lacks specificity, flagging sequencing errors as genuine variants.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Abundant low-frequency variants (~0.1-1%) that fail validation. | High error rate from the sequencer itself or from DNA damage during library prep. | Apply base quality score recalibration (BQSR). Use error-correction methods like single-molecule consensus sequencing [30]. |

| Clusters of false positives in specific sequence contexts (e.g., homopolymers). | Mapping errors or context-specific sequencing artifacts. | Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., MuTect, VarScan2) that filter variants biased toward read ends or those seen in only one orientation. Employ context-aware filters [30] [24]. |

| High false positive rate in metagenomic samples. | Using a variant caller designed for clonal germline samples. | Switch to a probabilistic variant caller validated for metagenomics, such as GATK's HaplotypeCaller or Mutect2, which show better performance in mixed samples [32]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Computational Error Reduction

- Align reads using a sensitive aligner like BWA-MEM [31].

- Mark or remove PCR duplicates using tools from the SAM/BAM utilities suite to prevent inflated allele frequencies [31].

- Recalibrate base quality scores using a tool like GATK's BQSR, which builds an error model from your data to produce more accurate quality scores [31].

- Call variants with a haplotype-aware tool like GATK HaplotypeCaller [31].

- Apply hard filters using a tool like GATK VariantFiltration or use a machine learning-based approach like Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR) to label and filter out low-confidence calls [30] [31].

Problem: Failure to Detect True Positive Variants (Low Sensitivity)

This indicates your pipeline is not sensitive enough, missing real variants, especially low-frequency ones.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Known variants (e.g., from Sanger sequencing) are not called. | Insufficient sequencing coverage or depth. | Increase average coverage. For exome sequencing, aim for 90–100× coverage to compensate for unevenness; for whole genome, 30× is typical but higher depth is needed for subclonal detection [31]. |

| Inability to detect subclonal variants (<1% allele frequency). | Background error rate is masking true signal. | Implement single-molecule consensus sequencing with UMIs. This tags original DNA molecules to generate a consensus sequence, reducing errors by orders of magnitude [30]. |

| Consistent missed calls in difficult genomic regions (e.g., segmental duplications). | Poor mapping quality in repetitive or complex regions. | Use a graph-based reference genome or a pipeline optimized for long-read sequencing data, which can improve mapping in these regions [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Barcoding for Low-Frequency Variant Detection

- Library Preparation with UMIs: During library preparation, use adapters that contain a unique molecular identifier (UMI) sequence. This UMI uniquely tags each original DNA molecule [30] [31].

- PCR Amplification & Sequencing: Proceed with PCR amplification and sequencing as normal. All copies derived from the same original molecule will share the same UMI [30].

- Bioinformatic Consensus Building: After sequencing, group reads by their UMI and mapping coordinates. Generate a consensus sequence for each group of reads, which corrects for random sequencing errors [30].

- Variant Calling: Call variants from the consensus reads, which now have a much lower error rate, enabling highly sensitive detection of rare variants [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function in Pipeline Design |

|---|---|

| PCR-free Library Prep Kits | Avoids PCR amplification biases and errors, improving the accuracy of variant allele frequency estimation and reducing false positives from duplicate reads [31]. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Adapters | Tags individual DNA molecules before amplification, allowing bioinformatic consensus building to eliminate PCR and sequencing errors. Essential for detecting low-frequency variants [30] [31]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | Reduces errors introduced during PCR amplification steps in library preparation, lowering the baseline false positive rate [30]. |

| BWA-MEM Aligner | A robust and sensitive algorithm for mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome, forming a critical foundation for accurate variant discovery [31]. |

| GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) | A industry-standard software suite for variant discovery that provides best-practice workflows for base recalibration, duplicate marking, and haplotype-based variant calling [32] [31]. |

| StratoMod or Similar Context-Aware Tools | An interpretable machine learning model that predicts where a specific variant calling pipeline is likely to fail based on genomic context, enabling proactive pipeline selection and optimization [24]. |

Pipeline Design and Error Analysis Workflows

Core Variant Calling and Error Mitigation Pipeline

Decision Framework for Pipeline Selection

Best Practices and Advanced Tools for Accurate Variant Calling

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers establishing a next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis pipeline. The content is framed within a broader thesis on addressing sequencing errors in chemogenomic variant calling research, focusing on the critical pathway from initial read alignment with BWA-MEM through variant calling with GATK best practices. The guidance below addresses common technical challenges encountered by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why does BWA-MEM produce different alignment results when using different numbers of threads? A: This is a known reproducibility issue in certain versions of BWA-MEM. Version 0.7.5a contained a bug that affected randomness when using multiple threads, leading to inconsistent mapping results [33]. Although this was reportedly fixed in the master branch, users have observed persistent variations in properly paired read counts even in version 0.7.17 [33]. For reproducible research, use consistent thread counts across analyses or consider alternative aligners like Bowtie2, which is deterministic when run with identical parameters [33].

Q: Why does my BWA-MEM job fail during the alignment process? A: A common failure point occurs during the BWA index-building step. One frequent cause is attempting to align paired-end reads where the two files contain reads of unequal length, often resulting from uneven quality trimming of read pairs [34]. Ensure both read files in a pair have identical numbers of sequences and consider performing quality adapter trimming in a way that either trims both reads or removes both reads of a pair if one fails quality thresholds [34].

Q: Why does GATK fail with "incompatible contigs" errors? A: This error occurs when contig names or sizes don't match between your input files (BAM/VCF) and reference genome [35]. For example, you might see chrM/16569 in your BAM file but chrM/16571 in your reference. This typically indicates you're using different genome builds (e.g., hg19 vs. GRCh38) or a reference that was modified from a similar but non-identical build [35]. The solution is to ensure all files use the same reference build consistently.

Q: Why does my pipeline run out of memory and fail with exit code 137? A: Exit code 137 indicates that a task was terminated for exceeding memory limits [36]. This commonly occurs during variant calling steps, particularly with whole-genome sequencing data. The solution is to increase the memory allocation ("mem_gb" runtime attribute) for the failing task [36]. For GATK-SV pipelines, also ensure you're deleting intermediate files to conserve disk space [36].

Q: Why are expected variants not being called at specific genomic positions? A: Variants may be missed due to several factors: insufficient sequencing coverage at the position, alignment artifacts around indels, or the variant existing in genomically challenging contexts [37] [24]. Homopolymer regions, segmental duplications, and other difficult-to-map regions are particularly problematic [24]. Consider using local realignment around indels, increasing coverage in target regions, or employing specialized tools like StratoMod that use machine learning to predict variant calling errors in specific genomic contexts [38] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common BWA-MEM Alignment Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting BWA-MEM Alignment Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Differential threading results | Bug in older versions (0.7.5a); parallelism issues [33] | Upgrade to latest BWA version; Use consistent thread count; Consider Bowtie2 for deterministic results [33] |

| Job fails during index building | Reference genome format issues; Uneven read lengths in pairs [34] | Validate reference FASTA format; Ensure paired reads have equal lengths; Re-process with symmetric trimming [34] |

| Apparent frameshift mutations | Visualization artifacts; Reference mismatch; Low-quality bases [39] | Confirm IGV uses same reference; Filter low-quality alignments (mapQ≥20); Mark duplicates; BamLeftAlign [39] |

| Low mapping percentage | Poor quality reads; Reference mismatch; Adapter contamination | Run quality control (FastQC); Verify reference genome build; Perform adapter trimming |

Common GATK Variant Calling Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting GATK Variant Calling Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incompatible contigs error | Reference genome mismatch between files [35] | Use consistent reference build; Liftover VCF files with Picard LiftoverVCF; Extract contigs of interest with -L [35] |

| Out of memory errors | Insufficient memory allocation; Large genomic intervals [36] | Increase mem_gb runtime attribute; Split analysis by chromosome; Increase disk space [36] |

| Missing expected variants | Low coverage; Alignment artifacts; Challenging genomic contexts [37] [24] | Increase sequencing depth; Local realignment; Use multiple variant callers; Review difficult regions [38] [24] |

| High false positive rate | Insufficient filtering; PCR artifacts; Mapping errors | Apply VQSR filtering; Use multiple callers; Mark duplicates; Base Quality Score Recalibration [38] |

Workflow Diagram: End-to-End Variant Calling Pipeline

Troubleshooting Decision Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Variant Calling Pipelines

| Tool/Resource | Function | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BWA-MEM | Read alignment to reference genome | Use latest version; For reproducible results, maintain consistent thread counts [38] [33] |

| GATK | Variant discovery and genotyping | Follow Best Practices workflow; Use appropriate version for your analysis [38] [37] |

| Samtools | BAM file manipulation and processing | Essential for sorting, indexing, and basic QC of alignment files [38] |

| Picard Tools | NGS data processing utilities | Used for marking duplicates, validating files, and liftover operations [38] [35] |

| GIAB Benchmarks | Reference variant datasets | Use for pipeline validation and benchmarking in known high-confidence regions [38] [24] |

| Exomiser/Genomiser | Variant prioritization | Optimize parameters for improved diagnostic variant ranking (85.5% in top 10 vs 49.7% with defaults) [40] |

| StratoMod | Error prediction with machine learning | Interpretable ML classifier predicts variant calling errors in specific genomic contexts [24] |

Advanced Considerations

Sex Chromosome-aware Analysis

Standard autosomal pipelines may perform suboptimally on sex chromosomes due to their unique characteristics. For XY samples, implement haploid calling on X and Y chromosomes rather than diploid calling to reduce false positives [41]. Align samples to reference genomes informed by the sex chromosome complement of the sample, which increases true positives in pseudoautosomal regions (PARs) and the X-transposed region (XTR) [41].

Optimizing Variant Prioritization

For rare disease research, parameter optimization in Exomiser significantly improves performance. For genome sequencing data, optimized parameters increased the percentage of coding diagnostic variants ranked within the top 10 candidates from 49.7% to 85.5% [40]. For exome sequencing, optimization improved top 10 rankings from 67.3% to 88.2% [40]. Use Genomiser as a complementary tool for noncoding variants, though performance improvements are more modest (15.0% to 40.0% in top 10 rankings) [40].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Duplicate Marking with Picard MarkDuplicates

Q: My duplicate marking step is taking an extremely long time and consuming high memory. What can I do?

- A: This is common with high-coverage whole-genome sequencing data. Use the

ASSUME_SORT_ORDER=coordinateparameter if your BAM is coordinate-sorted to skip re-sorting. Increase Java heap size with-Xmx(e.g.,-Xmx16G). For very large datasets, consider using--TMP_DIRto point to a drive with ample disk space.

- A: This is common with high-coverage whole-genome sequencing data. Use the

Q: After duplicate marking, my overall alignment rate seems low. Is this a problem?

- A: A lower alignment rate post-marking is normal and expected. The tool does not remove alignments; it simply flags or removes duplicates. The reported "percentage of duplicates" is the key metric. Rates above 20-30% in whole-genome sequencing may indicate over-amplification during library preparation and should be noted as a potential confounder in chemogenomic analyses.

Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR) with GATK

Q: The BQSR step fails with an error about "missing read groups" (@RG line). Why is this critical?

- A: The

@RGheader line, specifically theIDandSM(sample) fields, are mandatory for BQSR. The algorithm recalibrates data per read group to account for flow cell-lane specific errors. Without this, it cannot function. Ensure your BAM files have correct read groups added during the alignment or post-alignment processing.

- A: The

Q: I am working with a non-model organism or a custom panel. How can I perform BQSR without a comprehensive known variant set (like dbSNP)?

- A: You can create a "known sites" resource from your own data. Sequence a control sample to high depth (e.g., >50x) and call variants rigorously to create a high-confidence set. This set can then be used as the known sites input for BQSR on your experimental samples.

Local Realignment with GATK

Q: Is local realignment around indels still necessary with modern aligners like BWA-MEM?

- A: While BWA-MEM performs some local assembly, systematic misalignments around indels, especially in low-complexity regions, persist. Realignment improves the mapping quality of reads in these regions, leading to more accurate variant calls, which is non-negotiable for identifying drug-resistance mutations.

Q: The realignment step is resource-intensive. Are there alternatives?

- A: For germline calling, the GATK best practices have superseded local realignment with HaplotypeCaller, which performs a superior local assembly. However, for somatic variant calling with MuTect2, realignment of the normal/tumor BAMs together is often still a required pre-processing step to ensure consistent alignment.

Quantitative Impact of Pre-Processing Steps

The following table summarizes the typical impact of each pre-processing step on key metrics in a human whole-genome sequencing dataset.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Pre-Processing Steps on Variant Calling

| Pre-Processing Step | Effect on Total Read Count | Typical Reduction in Apparent Insertions/Deletions (Indels) | Typical Improvement in SNP Concordance | Key Metric to Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplicate Marking | Reduces by 5-20% | Minimal direct effect | Minimal direct effect | Percentage of Duplicates |

| Local Realignment | No change | Reduces by 10-25% | Slight improvement (<1%) | Number of Realigned Targets |

| Base Quality Score Recalibration | No change | Improves call quality | Improves both call quality and concordance by 1-3% | Post-Recalibration Quality Score Distribution |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: GATK Pre-Processing Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for processing aligned BAM files prior to variant discovery.

1. Input Materials: Coordinate-sorted BAM file(s) from BWA-MEM alignment. Reference genome (FASTA). Known variant sites resource (e.g., dbSNP, VCF).

2. Duplicate Marking:

- Tool: Picard MarkDuplicates

- Command:

3. Local Realignment:

- a. Create Realignment Targets:

- b. Perform Realignment:

4. Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR):

- a. Build Recalibration Model:

- b. Apply Recalibration:

Output: The final

analysis_ready.bamis suitable for variant calling.

Workflow Visualization

Title: NGS Pre-Processing Workflow

Title: BQSR Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools & Resources for Pre-Processing

| Item | Function in Pre-Processing | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BWA-MEM | Sequence alignment to a reference genome. | Generates the initial SAM/BAM file for input. |

| Picard Tools | A set of command-line utilities for manipulating sequencing data. | MarkDuplicates is the standard for duplicate marking. |

| GATK Suite | A comprehensive toolkit for variant discovery and genotyping. | Used for RealignerTargetCreator, IndelRealigner, and BaseRecalibrator/ApplyBQSR. |

| Reference Genome | The standard sequence against which reads are aligned. | Must be the same version used for alignment and pre-processing (e.g., GRCh38). |

| Known Sites Resource | A database of known polymorphic sites. | Used by BQSR to avoid masking true variants as errors (e.g., dbSNP, Mills indel set). |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Under what conditions is GATK HaplotypeCaller particularly advantageous? GATK HaplotypeCaller uses local assembly of haplotypes to resolve uncertain regions, which makes it particularly strong in calling insertions and deletions (INDELs) and variants within difficult-to-map genomic contexts, such as those with high homology or low complexity [31] [42].

Q2: For somatic variant calling in cancer, which of these callers is recommended? Strelka2 and GATK Mutect2 are highly recommended for somatic mutation detection. Strelka2's tiered haplotype model is specifically designed for both germline and somatic calling [31], while Mutect2 is the standard GATK tool for identifying somatic SNVs and Indels with high accuracy [42].

Q3: What is a critical pre-processing step to improve accuracy for all these callers? Local realignment around known indels and base quality score recalibration (BQSR) are critical pre-processing steps. One study found that realignment and recalibration significantly improved the positive predictive value of variant calls, reducing false positives caused by alignment artifacts [43].

Q4: How can I objectively benchmark the performance of my chosen variant caller? It is best practice to use established benchmark datasets where the true variants are known, such as those from the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Consortium or the Platinum Genomes [44]. These resources provide a "ground truth" set of variants for the human genome, allowing you to calculate the sensitivity and precision of your pipeline.

Q5: My variant caller is reporting a high number of false positives. What are some common filters to apply? Common filtering strategies include thresholds for variant confidence/quality scores, read depth, mapping quality, and strand bias [43]. For GATK, using the Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR) method, which builds an adaptive model based on a set of annotations, has been shown to achieve higher specificity than applying hard filters [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Concordance with Known Genotypes or Benchmark Data

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate data pre-processing.

- Solution: Ensure your BAM files have been properly processed. This includes marking PCR duplicates, local realignment around indels, and base quality score recalibration (BQSR). Studies have shown these steps, particularly realignment and recalibration, are crucial for high accuracy [43].

- Potential Cause 2: Suboptimal sequencing depth.

- Solution: Check the depth of coverage at discordant variant sites. Whole-genome sequencing should typically achieve 30-60x coverage, while exome sequencing requires much higher depth (e.g., 100x) to compensate for uneven coverage [31]. Consider increasing sequencing depth in low-coverage regions.

- Potential Cause 3: Incorrect tool configuration for variant type.

- Solution: Confirm you are using the correct tool and parameters for your study design. For example, use GATK Mutect2, not HaplotypeCaller, for somatic tumor-normal pairs [42]. Always use the latest version of the caller and consult the tool's documentation for best-practice parameters.

Problem: Poor Performance in Repetitive or Hard-to-Map Genomic Regions

- Potential Cause: Inherent limitations of short-read mappers in complex regions.

- Solution: This is a known challenge for all short-read callers. Consider leveraging genome stratifications (like those from GIAB) to understand your pipeline's performance in specific contexts (e.g., low-complexity or homologous regions) [24]. For critical projects, incorporating long-read sequencing data or using a graph-based reference genome can improve results in these difficult areas [24].

Problem: High Number of Apparent INDEL Errors

- Potential Cause: Alignment artifacts around indels.

- Solution: This re-emphasizes the importance of local realignment as a pre-processing step [43]. Additionally, inspect the read support for the INDELs in a tool like the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). False positives often show poor read support, significant strand bias, or are located in homopolymer runs.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the characteristics and recommended use cases for GATK HaplotypeCaller, Strelka2, and FreeBayes based on current literature and tool documentation.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of GATK HaplotypeCaller, Strelka2, and FreeBayes

| Feature | GATK HaplotypeCaller | Strelka2 | FreeBayes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Germline SNVs/Indels [44] [31] | Germline & Somatic SNVs/Indels [31] | Germline SNVs/Indels [44] [31] |

| Core Algorithm | Local de-novo assembly of haplotypes [42] | Tiered haplotype model [31] | Haplotype-based Bayesian model [31] |

| Key Strength | Accurate INDEL calling; well-supported best practices | Efficient; designed for both germline and somatic calling | Sensitive to complex variants like MNPs [31] |

| Benchmark Performance | Showed higher positive predictive value (92.55%) vs. an older SAMtools method (80.35%) [43] | Recommended as a best-practice tool for somatic and germline calling [31] | Popular and effective for germline variant discovery [44] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Best-Practice Germline Variant Calling with GATK HaplotypeCaller This protocol is based on established best practices and validation studies [44] [43].

- Raw Read Mapping: Map sequencing reads in FASTQ format to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using the BWA-MEM aligner [44] [31].

- Post-Alignment Processing: Sort the resulting BAM file and mark PCR duplicates using tools like Picard or Sambamba [44] [43].

- Variant Calling: Execute GATK HaplotypeCaller in GVCF mode on the pre-processed BAM file to perform local reassembly and generate per-sample genomic VCFs (gVCFs).

- Joint Genotyping: Consolidate multiple gVCFs using GATK's

GenotypeGVCFstool. - Variant Filtration: Apply variant quality score recalibration (VQSR) to the raw joint-called VCF to produce a final, high-confidence callset. Studies have shown VQSR can provide better specificity than hard filtering [43].

Protocol 2: Somatic Variant Discovery for Tumor-Normal Pairs This protocol summarizes the GATK best-practice workflow for somatic short variants [42].

- Call Candidate Variants: Run Mutect2 (GATK's somatic caller) on the matched tumor and normal BAMs. Mutect2 uses local assembly and a Bayesian model to calculate the likelihood of a variant being somatic [42].

- Estimate Contamination: Use

GetPileupSummariesandCalculateContaminationto estimate the level of cross-sample contamination in the tumor sample. - Model Artifacts: Use

LearnReadOrientationModelto account for orientation-specific biases common in some sample types like FFPE. - Filter Variants: Pass the initial calls, contamination data, and artifact models to

FilterMutectCallsto produce a filtered set of somatic variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Variant Calling

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Materials | Provides benchmark genomes (e.g., HG002) with well-characterized, high-confidence variant calls to validate the accuracy of your sequencing and analysis pipeline [44]. |

| BWA-MEM Aligner | A widely used software tool for accurately mapping short sequencing reads to a reference genome, which is a critical first step before variant calling [44] [31]. |

| Picard Tools | A set of command-line tools for manipulating sequencing data in SAM/BAM format, most commonly used for marking PCR duplicate reads [44] [43]. |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) | A high-performance visualization tool for interactive exploration of large genomic datasets, essential for visually inspecting and validating variant calls [44]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized best-practice workflow for germline variant discovery, integrating the key steps and tools discussed.

Best-Practice Germline Variant Discovery Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is StratoMod and what specific variant calling problem does it solve? StratoMod is an interpretable machine learning (IML) classifier designed to predict germline variant calling errors based on genomic context [24]. No single sequencing pipeline is optimal across the entire genome [24]. StratoMod addresses this by providing a data-driven method to predict where a specific pipeline is likely to make an error, such as missing a true variant (false negative) or calling an erroneous one (false positive) [24] [45]. This is a significant improvement over traditional pipelines, which typically only filter potential false positives, as StratoMod can also predict clinically relevant variants that are likely to be missed [24].

2. Why should I use an "interpretable" model like StratoMod instead of a deep learning model? Interpretable models, like the Explainable Boosting Machines (EBMs) used by StratoMod, provide clarity on how a prediction is made [24] [46]. Unlike "black box" deep learning models, you can inspect the model to understand the contribution of specific genomic features (e.g., homopolymer length, mapping difficulty) to the final error prediction [24] [47]. This is crucial for:

- Justifying decisions in a clinical or diagnostic setting [46] [47].

- Guiding pipeline development by precisely identifying which genomic contexts cause failures [24] [48].

- Gaining biological insights from the model itself, as the learned relationships can reveal new error modalities [46] [47].

3. What are the most common genomic features that lead to variant calling errors? Errors are often concentrated in specific, challenging genomic regions. The following table summarizes key problematic contexts and their impact on variant calling.

| Genomic Context | Description | Impact on Variant Calling |

|---|---|---|

| Homopolymers [24] [48] | Tandem repeats of a single nucleotide. | Higher error rates as length increases; challenges most sequencing technologies [24] [48]. |

| Segmental Duplications [24] [48] | Large, highly identical DNA segments. | Causes read mis-mapping, leading to false positives and false negatives [24] [48]. |

| Difficult-to-Map Regions [24] | Regions with low uniqueness or high complexity. | Reduces mapping confidence and variant call recall, particularly for short reads [24]. |

| Processed Pseudogenes [49] | Non-functional genomic copies of parent genes. | Reads from pseudogenes misalign to functional parent genes, creating false positive variant calls [49]. |

4. My variant caller is reporting a potentially pathogenic variant in a well-known gene, but the allelic fraction is ~25-30%. Should I be concerned? This pattern is a classic signature of a false positive variant originating from a processed pseudogene [49]. When a pseudogene is present, sequencing reads from both the functional gene and the non-functional pseudogene align to the reference. A true heterozygous variant in the functional gene has an allelic balance (AB) of ~50%. An AB of ~25-30% strongly suggests the variant is only present in the pseudogene, which typically contributes a smaller fraction of the reads [49]. You should orthogonally validate this finding before reporting it.

5. How do I get started with running StratoMod on my own data? The StratoMod pipeline is publicly available on GitHub [48]. The basic workflow is as follows:

- Input: Your query VCF file from your variant calling pipeline [48].

- Configuration: The pipeline can be configured to automatically download standard reference data (e.g., GIAB benchmarks, stratification BED files for genomic features) [48].

- Execution: The pipeline is run via Snakemake, which manages the computational environment and workflow steps [48].

- Output: An HTML report containing model performance metrics and, most importantly, interpretable plots showing how each genomic feature influences error prediction [48].

The diagram below illustrates the complete StratoMod workflow, from data input to final interpretation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High false positive variant calls in genes with high sequence homology (e.g., pseudogenes).

Explanation: This occurs when sequencing reads from a non-functional, highly similar genomic region (like a processed pseudogene) are incorrectly mapped to a functional gene in the reference genome. This generates mismatches that are called as variants, even though they are not present in the functional gene [49].

Solution:

- Inspect the Allelic Balance (AB): As noted in the FAQ, an AB of ~25-30% is a strong indicator of a pseudogene-originating variant [49].

- Re-call variants with an advanced tool: Benchmarking shows that DeepVariant is particularly effective at suppressing these spurious calls compared to other popular tools like GATK HaplotypeCaller or DRAGEN [49]. The table below quantifies this performance difference.

- Utilize structural variant callers: Tools like

Smoovecan detect the presence of non-reference processed pseudogenes by identifying specific patterns of split and mismatched reads in your data. This can help you flag genes prone to this issue [49].

Problem: Low recall (high false negatives) in difficult genomic regions.

Explanation: Your sequencing and analysis pipeline may be systematically missing true variants in complex regions like homopolymers, segmental duplications, and low-mappability regions [24] [31]. This is a known limitation of all pipelines, but the specific locations of failure vary.

Solution:

- Implement StratoMod for Prediction: Use StratoMod to predict the recall of your specific pipeline (e.g., Illumina vs. HiFi) across the genome. This will pinpoint the regions and variant types (SNVs or INDELs) where your recall is likely lowest [24].

- Leverage a better benchmark: Train or test your model using the latest benchmarks, such as the draft T2T-HG002 Q100 assembly-based benchmark, which provides truth sets in previously inaccessible difficult regions [24].

- Consider technology and algorithm trade-offs: StratoMod can help quantify the trade-offs. For example, it has been used to show that graph-based reference genomes can improve recall in hard-to-map regions compared to linear references [24]. Using long-read technologies (like PacBio HiFi) can also improve performance in these areas [24] [31].

Problem: Inconsistent or unreliable explanations from the interpretable model.

Explanation: This pitfall can occur when using post-hoc explanation methods (like SHAP or LIME) without proper validation. Different IML methods can produce different explanations for the same prediction, and some methods can be unstable to small input changes [46].

Solution:

- Use interpretable-by-design models: StratoMod uses Explainable Boosting Machines (EBMs), which are a type of Generalized Additive Model (GAM) that are inherently interpretable. The model's structure directly reveals feature impacts without needing a separate explanation step, enhancing reliability [24] [46].

- Evaluate explanation faithfulness and stability: When using any IML method, it's good practice to algorithmically evaluate the quality of the explanations. Faithfulness measures how well the explanation reflects the model's actual logic, while stability measures how consistent explanations are for similar inputs [46].

- Compare multiple IML methods: Avoid relying on a single IML method. If possible, compare explanations from multiple techniques (e.g., both a by-design method and a post-hoc method) to build confidence in your interpretations [46].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Implementing and Validating Interpretable Error Prediction

| Item | Function & Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Benchmark Sets [24] | Provides high-confidence variant calls (VCFs) and associated BED files to define "truth" for model training and validation. | Includes well-characterized genomes (e.g., HG002) and difficult-to-map region stratifications. Critical for labeling your data. |

| Genomic Stratification BED Files [24] [48] | Defines genomic contexts of interest (e.g., homopolymers, segmental duplications). Used as features for the StratoMod model. | Can be sourced from GIAB and UCSC (e.g., Simple Repeats, RepeatMasker, Segmental Dups). |

| StratoMod Software [48] | The core tool for building interpretable models to predict variant calling errors. | Available on GitHub. Uses a Snakemake workflow and a Conda/Mamba environment for reproducibility. |

| T2T-HG002 Q100 Assembly [24] | A near-perfect, complete diploid assembly. | Serves as an advanced benchmark for evaluating performance in the most difficult regions of the genome. |

| DeepVariant [49] | A deep learning-based variant caller that has demonstrated high accuracy, particularly in suppressing false positives from pseudogenes. | A useful tool to compare against your primary pipeline's performance in challenging contexts. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using RNA-Seq data for variant calling over DNA sequencing? RNA-Seq allows for the detection of variants that are actively expressed in the transcriptome. It can uncover allele-specific expression (ASE), where one allele is expressed at a significantly different level than the other, a phenomenon often missed by DNA sequencing alone. Furthermore, RNA-Seq is particularly valuable for identifying splicing defects and other transcript-level disruptions that have functional consequences [50] [51].

Q2: My RNA-Seq variant calls have a high false-positive rate. How can I improve accuracy? High false positives in RNA-Seq variant calling are often due to mapping errors near splice junctions, repetitive regions, or RNA editing sites. To mitigate this, use tools specifically designed for RNA-Seq data. The VarRNA pipeline, for instance, employs a two-stage XGBoost machine learning model to effectively distinguish true somatic and germline variants from sequencing and alignment artifacts [50]. Ensuring proper post-alignment processing, such as base quality score recalibration and using known variant sites for filtering, is also crucial [50].

Q3: Can I detect somatic variants from tumor RNA-Seq data without a matched normal sample? Yes, but it is computationally challenging. Methods like VarRNA are trained to classify variants as germline, somatic, or artifact using only the tumor RNA-Seq data, eliminating the need for a matched normal DNA sample. This is achieved through machine learning models trained on known variant features and datasets [50]. For long-read data, tools like ClairS-TO have also been developed specifically for tumor-only somatic variant detection [52].

Q4: What kind of unique biological insights can ASE analysis from tools like VarRNA provide? Allele-specific expression analysis can reveal mechanisms of tumor progression. For example, in cancer-driving genes, the mutant allele can be expressed at a much higher frequency than expected from the DNA variant allele frequency (VAF). This indicates a potential selective advantage for cells expressing the mutant transcript and highlights genes that may be actively driving the cancer pathogenesis [50].

Q5: Our lab is new to integrated RNA-Seq analysis. Are there comprehensive workflows available? Yes, several workflows integrate transcriptomic and genomic analysis. The MIGNON workflow is one example that not only performs standard gene expression quantification but also calls genomic variants from the same RNA-Seq data and integrates both data types for a functional analysis of signaling pathway activities [53].

Troubleshooting Guides