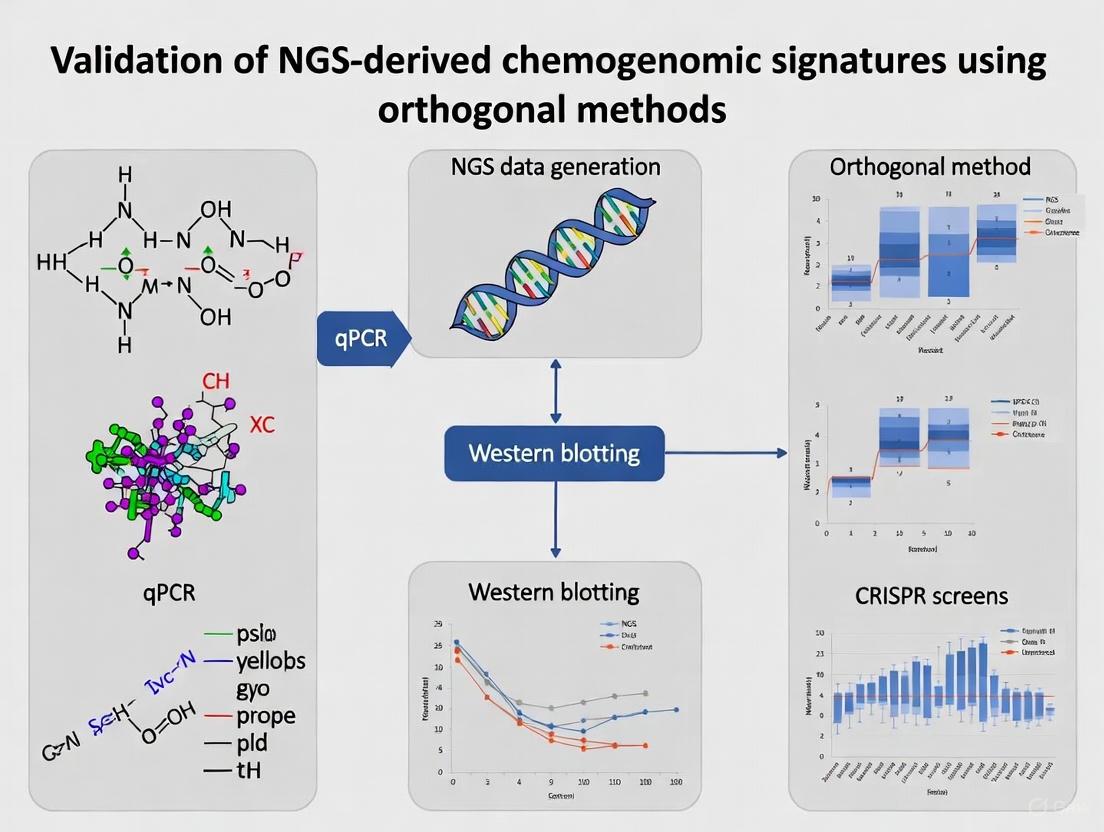

A Practical Framework for Orthogonal Validation of NGS-Derived Chemogenomic Signatures in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously validate next-generation sequencing (NGS)-derived chemogenomic signatures.

A Practical Framework for Orthogonal Validation of NGS-Derived Chemogenomic Signatures in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously validate next-generation sequencing (NGS)-derived chemogenomic signatures. It covers the foundational principles of chemogenomics and NGS technology, explores integrated methodological approaches for signature discovery, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a robust framework for validation using orthogonal techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and validation strategies, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and clinical translatability of chemogenomic data, ultimately accelerating targeted therapeutic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of NGS and Chemogenomics

Chemogenomics represents an emerging, interdisciplinary field that has prompted a fundamental paradigm shift within pharmaceutical research, moving from traditional receptor-specific studies to a comprehensive cross-receptor view [1]. This approach systematically explores biological interactions by attempting to fully map the pharmacological space between chemical compounds and macromolecular targets, fundamentally operating on the principle that "similar receptors bind similar ligands" [1] [2]. The primary objective of chemogenomics is to establish predictive links between the chemical structures of bioactive molecules and the receptors with which these molecules interact, thereby accelerating the modern drug discovery process [1].

This strategic reorientation addresses a critical pharmacological reality: while the human genome encodes approximately 3000 druggable targets, only about 800 have been seriously investigated by the pharmaceutical industry [2]. Similarly, of the millions of known chemical structures, only a minute fraction has been tested against this limited target space [2]. Chemogenomics aims to bridge this gap by systematically matching target space and ligand space through high-throughput miniaturization of chemical synthesis and biological evaluation, ultimately seeking to identify all ligands for all potential targets [2].

Core Principles and Conceptual Framework

Fundamental Hypotheses and Operational Assumptions

The chemogenomic approach rests on two foundational hypotheses that guide its methodology and experimental design. First, compounds sharing chemical similarity should share biological targets, allowing for prediction of novel targets based on structural resemblance to known active compounds [2]. Second, targets sharing similar ligands should share similar binding site patterns, enabling the extrapolation of ligand information across related protein families [2]. These principles facilitate the systematic compilation of the theoretical chemogenomic matrix—a comprehensive two-dimensional grid mapping all possible compounds against all potential targets [2].

The practical implementation of these principles occurs through three primary methodological frameworks: ligand-based approaches (comparing known ligands to predict their most probable targets), target-based approaches (comparing targets or ligand-binding sites to predict their most likely ligands), and integrated target-ligand approaches (using experimental and predicted binding affinity matrices) [1] [2]. This multi-faceted strategy enables researchers to fill knowledge gaps in the chemogenomic matrix by inferring data for "unliganded" targets from the closest "liganded" neighboring targets, and information for "untargeted" ligands from the closest "targeted" ligands [2].

Key Methodological Approaches in Chemogenomics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Chemogenomic Methodological Approaches

| Approach Type | Fundamental Principle | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based | "Similar compounds bind similar targets" [2] | GPCR-focused library design [1]; Target prediction | Applicable when target structure is unknown |

| Target-Based | "Similar targets bind similar ligands" [1] | Target hopping between receptor families [1]; Binding site comparison | Leverages protein sequence/structure data |

| Target-Ligand | Integrated analysis of compound-target pairs [1] | Machine learning prediction of orphan receptor ligands [1] | Holistic view of chemical-biological space |

Experimental Applications and Workflows

Chemogenomic Profiling in Infectious Disease Research

Chemogenomic profiling has demonstrated significant utility in antimicrobial drug discovery, particularly for pathogens like Plasmodium falciparum, the parasite responsible for malaria. This approach enables the functional classification of drugs with similar mechanisms of action by comparing drug fitness profiles across a collection of mutants [3]. The experimental workflow involves creating a library of single-insertion mutants via piggyBac transposon mutagenesis, followed by quantitative dose-response assessment (IC50 values) of each mutant against a library of antimalarial drugs and metabolic inhibitors [3].

The resulting chemogenomic profiles enable researchers to visualize complex genotype-phenotype associations through two-dimensional hierarchical clustering, grouping genes with similar chemogenomic signatures horizontally and compounds displaying similar phenotypic patterns vertically [3]. This methodology successfully identified that drugs targeting the same pathway exhibit significantly more similar profiles than those targeting different pathways (correlation of r = 0.33 versus r = 0.24; Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.01) [3]. Furthermore, this approach confirmed known antimalarial drug pairs with similar activity while revealing unexpected associations, such as the positive correlation between responses to the mitochondrial inhibitors rotenone and atovaquone with lumefantrine, suggesting potential novel mitochondrial interactions for the latter drug [3].

Figure 1: Chemogenomic profiling workflow for antimalarial drug discovery, showing the process from mutant library creation to mechanism of action prediction [3].

Integrated RNA and DNA Sequencing for Signature Validation

The validation of chemogenomic signatures increasingly relies on advanced genomic technologies, particularly integrated RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) with whole exome sequencing (WES). This combined approach substantially improves detection of clinically relevant alterations in cancer by enabling direct correlation of somatic alterations with gene expression, recovery of variants missed by DNA-only testing, and enhanced detection of gene fusions [4]. When applied to 2230 clinical tumor samples, this integrated assay demonstrated the capability to uncover clinically actionable alterations in 98% of cases, while also revealing complex genomic rearrangements that would likely have remained undetected without RNA data [4].

The analytical validation of such integrated assays requires a rigorous multi-step process: (1) analytical validation using custom reference samples containing thousands of SNVs and CNVs; (2) orthogonal testing in patient samples; and (3) assessment of clinical utility in real-world cases [4]. This comprehensive validation framework ensures that chemogenomic signatures derived from these platforms meet the stringent requirements for clinical application and therapeutic decision-making.

In Silico Repositioning Strategies for Parasitic Diseases

Chemogenomic approaches have proven particularly valuable for drug repositioning in neglected tropical diseases, as demonstrated in schistosomiasis research. This strategy involves the systematic screening of a parasite proteome (2114 proteins in the case of Schistosoma mansoni) against databases of approved drugs to identify potential drug-target interactions [5]. The methodology employs a combination of pairwise alignment, conservation state of functional regions, and chemical space analysis to refine predicted drug-target interactions [5].

This computational repositioning strategy successfully identified 115 drugs that had not been experimentally tested against schistosomes but showed potential activity based on target similarity [5]. The approach correctly predicted several drugs previously known to be active against Schistosoma species, including clonazepam, auranofin, nifedipine, and artesunate, thereby validating the methodology before its application to novel compound discovery [5].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Chemogenomic Studies

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | GPCR-focused library [1]; Purinergic GPCR-targeted library [1]; Pfizer/GSK compound sets [6] | Provide diverse chemical matter for screening | Phenotypic screening; Target-based screening |

| Bioinformatic Databases | ChEMBL [6]; TTD [5]; DrugBank [5]; STITCH [5] | Store drug-target interaction data | In silico prediction; Target identification |

| Pathway Resources | KEGG [6]; Gene Ontology [6] | Annotate protein function and pathways | Mechanism of action studies |

| Genomic Tools | Whole exome sequencing [4]; RNA-seq [4] | Detect genetic variants and expression | Signature validation; Biomarker discovery |

| Screening Technologies | Cell Painting [6]; High-content imaging [6] | Generate morphological profiles | Phenotypic screening; Mechanism analysis |

Data Analysis and Machine Learning Integration

Machine Learning for Variant Confidence Prediction

Modern chemogenomics increasingly incorporates machine learning algorithms to enhance the prediction and validation of genomic signatures. In next-generation sequencing applications, supervised machine learning models including random forest, logistic regression, gradient boosting, AdaBoost, and Easy Ensemble methods have been employed to classify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) into high or low-confidence categories [7]. These models utilize features such as allele frequency, read count metrics, coverage, quality scores, read position probability, homopolymer presence, and overlap with low-complexity sequences to differentiate true positive from false positive variants [7].

The implementation of a two-tiered confirmation bypass pipeline incorporating these models has demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving 99.9% precision and 98% specificity in identifying true positive heterozygous SNVs within benchmark regions [7]. This approach significantly reduces the need for orthogonal confirmation of high-confidence variants while maintaining rigorous accuracy standards, thereby streamlining the analytical workflow for chemogenomic signature validation.

Figure 2: Machine learning workflow for variant classification, showing the process from training data to high/low confidence categorization [7].

Chemogenomic Data Integration and Network Analysis

The integration of heterogeneous data sources represents a critical component of modern chemogenomics. Network pharmacology platforms that integrate drug-target-pathway-disease relationships have been developed using graph database technologies (e.g., Neo4j), enabling sophisticated analysis of the complex relationships between chemical compounds, their protein targets, and associated biological pathways [6]. These platforms facilitate the identification of proteins modulated by chemicals that correlate with morphological perturbations at the cellular level, potentially leading to identifiable phenotypes or disease states [6].

The development of specialized chemogenomic libraries comprising 5000 small molecules representing diverse drug targets involved in multiple biological effects and diseases further enhances these network-based approaches [6]. Such libraries, when combined with morphological profiling data from high-content imaging assays like Cell Painting, create powerful systems for target identification and mechanism deconvolution in phenotypic screening campaigns [6].

Comparative Performance of Methodological Approaches

Cross-Technology Validation Frameworks

The validation of chemogenomic signatures requires rigorous orthogonal methods to ensure analytical and clinical accuracy. For integrated RNA and DNA sequencing assays, this involves a comprehensive framework including: (1) analytical validation using reference samples containing 3042 SNVs and 47,466 CNVs; (2) orthogonal testing in patient samples; and (3) assessment of clinical utility in real-world applications [4]. This multi-layered approach ensures that detected alterations, including gene expression changes, fusions, and alternative splicing events, meet stringent clinical standards [4].

For machine learning-based variant classification, performance metrics across different algorithms demonstrate that while logistic regression and random forest models exhibit the highest false positive capture rates, gradient boosting achieves the optimal balance between false positive capture rates and true positive flag rates [7]. These quantitative comparisons inform the selection of appropriate analytical methods for specific chemogenomic applications.

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery

The practical impact of chemogenomic approaches is evidenced by multiple successful applications in drug discovery programs. For instance, the design and knowledge-based synthesis of chemical libraries targeting the purinergic GPCR subfamily at Sanofi-Aventis resulted in the identification of three novel adenosine A1 receptor antagonist series from screening libraries comprising 2400 compounds built around 5 chemical scaffolds [1]. Similarly, "target hopping" approaches leveraging binding site similarities have enabled the identification of potent antagonists for the prostaglandin D2-binding GPCR (CRTH2) by screening compounds based on angiotensin II antagonists, despite low overall sequence homology between these receptors [1].

These successes underscore the transformative potential of chemogenomics to accelerate lead identification and optimization by leveraging the fundamental principles of receptor similarity and ligand promiscuity across target families, ultimately expanding the druggable genome and enabling more efficient therapeutic development.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics by enabling massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously, dramatically reducing the cost and time required for genetic analysis compared to first-generation Sanger sequencing [8]. This transformation began with second-generation short-read technologies and has expanded to include third-generation long-read platforms, each with distinct advantages for specific applications in research and clinical diagnostics [9] [10].

The evolution of NGS technologies represents a fundamental shift from sequential to parallel processing of genetic information. First-generation methods like Sanger sequencing provided accurate but low-throughput readouts, while contemporary NGS platforms now deliver unprecedented volumes of genetic data, making large-scale projects like whole-genome sequencing accessible to individual laboratories [9]. This technological progression has been characterized by continuous improvements in read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness, enabling increasingly sophisticated applications across diverse fields including oncology, infectious diseases, agrigenomics, and personalized medicine [11] [8].

Comparative Analysis of Major NGS Platforms

Platform Specifications and Performance Metrics

The current NGS landscape features diverse platforms with specialized capabilities. Table 1 summarizes the key technical specifications of major sequencing systems, highlighting their distinct approaches to nucleic acid sequencing.

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Technologies

| Platform/Company | Sequencing Technology | Read Length | Key Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina [8] | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) with reversible dye terminators | Short-read (36-300 bp) | Whole-genome sequencing, targeted sequencing, gene expression | High accuracy, high throughput, established workflows | Potential signal crowding in overloaded samples |

| Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) [10] [8] | Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing | Long-read (avg. 10,000-25,000 bp) | De novo genome assembly, full-length isoform sequencing, structural variant detection | Very long reads, high consensus accuracy (HiFi reads: Q30-Q40) | Higher cost per sample, complex data analysis |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [10] [8] | Nanopore detection of electrical signal changes | Long-read (avg. 10,000-30,000 bp) | Real-time sequencing, field sequencing, metagenomics, epigenetic modifications | Ultra-long reads, portability, direct RNA sequencing | Higher error rates (~15% for simplex), though duplex reads now achieve >Q30 |

| MGI Tech [12] [13] | DNA Nanoball sequencing with combinatorial probe anchor synthesis | Short-read (50-150 bp) | Whole exome sequencing, whole genome sequencing | Cost-effective, high throughput | Multiple PCR cycles required |

| Element Biosciences [13] | Avidity sequencing | Short-read | Transcriptomics, chromatin profiling | Lower cost, high data quality | Relatively new platform |

| Ultima Genomics [13] | Sequencing on silicon wafers | Short-read | Large-scale genomic studies | Ultra-low cost ($80/genome) | Emerging technology |

Experimental Validation of Platform Performance

Rigorous validation studies provide critical performance data for platform selection. A 2025 comparative assessment of four whole exome sequencing (WES) platforms on the DNBSEQ-T7 sequencer demonstrated that platforms from BOKE, IDT, Nanodigmbio, and Twist Bioscience exhibited comparable reproducibility and superior technical stability with high variant detection accuracy [12]. The study established a robust workflow for probe hybridization capture compatible across all four commercial exome kits, enhancing interoperability regardless of probe brand [12].

For combined RNA and DNA analysis, a 2025 validated assay integrating RNA-seq with WES demonstrated substantially improved detection of clinically relevant alterations in cancer compared to DNA-only approaches [4]. Applied to 2230 clinical tumor samples, this integrated approach enabled direct correlation of somatic alterations with gene expression, recovered variants missed by DNA-only testing, and improved fusion detection, uncovering clinically actionable alterations in 98% of cases [4].

Advanced Applications in Research and Clinical Settings

Multi-Omics Integration and Single-Cell Analysis

The integration of multiple data modalities represents a frontier in NGS applications. Multi-omics approaches combine genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics to provide a comprehensive view of biological systems [11]. This integrative strategy has proven particularly valuable in cancer research, where it helps dissect the tumor microenvironment and reveal interactions between cancer cells and their surroundings [11].

PacBio's recently launched SPRQ chemistry exemplifies this trend toward multi-omics by enabling simultaneous extraction of DNA sequence and regulatory information from the same molecule [10]. This approach uses a transposase enzyme to insert special adapters into open chromatin regions, preserving long, native DNA molecules while capturing accessibility information that reflects regulatory activity [10].

Pharmacogenomics and Complex Gene Analysis

Long-read sequencing technologies have emerged as particularly valuable for pharmacogenomics applications, where they resolve challenges posed by complex genomic regions in key pharmacogenes. Table 2 highlights specific pharmacogenomic applications where long-read sequencing provides unique advantages.

Table 2: Long-Read Sequencing Applications in Pharmacogenomics

| Gene | Challenging Features | LRS Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 [14] | Structural variants, copy number variations, pseudogenes (CYP2D7, CYP2D8) | Resolves complex diplotypes, detects structural variants and hybrid genes |

| CYP2B6 [14] | Structural variants (CYP2B6*29, *30), pseudogene (CYP2B7) | Accurate variant calling in repetitive regions and pseudogene-homologous areas |

| HLA genes [14] | Extreme polymorphism, structural variants | Provides complete phasing and accurate allele determination |

| UGT2B17 [14] | Gene deletion polymorphisms, copy number variations | Direct detection of gene presence/absence and precise CNV characterization |

Long-read sequencing platforms from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore enable accurate genotyping in analytically challenging pharmacogenes without specialized DNA treatment, performing full phasing and resolving complex diplotypes while reducing false-negative results in a single assay [14]. This capability is particularly valuable for clinical implementation of pharmacogenomic testing where accurate haplotype determination directly impacts phenotype prediction and drug response stratification [14].

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

NGS Workflow and Quality Control

The fundamental NGS workflow comprises three critical stages: (1) template preparation, (2) sequencing and imaging, and (3) data analysis [9]. Each stage requires rigorous quality control to ensure reliable results. The following diagram illustrates a generalized NGS workflow with key quality checkpoints:

For WES, specifically, the hybridization capture process requires careful optimization. A 2025 study established a robust protocol using the MGIEasy Fast Hybridization and Wash Kit that demonstrated uniform performance across four different commercial exome capture platforms [12]. This protocol utilized:

- 50-200 ng of fragmented genomic DNA (100-700 bp fragments)

- MGIEasy UDB Universal Library Prep Set for library construction

- 1-plex (1000 ng input) or 8-plex (250 ng per library) hybridization

- 1-hour standardized hybridization incubation

- 12 cycles of post-capture PCR amplification [12]

Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Protocol

For comprehensive genomic characterization, particularly in oncology, integrated DNA-RNA sequencing approaches provide complementary information. A validated combined assay utilizes the following methodology:

Wet Lab Procedures:

- Nucleic acid isolation from tumor samples using Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA kits

- Library construction with TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (RNA) and SureSelect XTHS2 kits (DNA)

- Exome capture using SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR (RNA) and V7 (DNA) probes

- Sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with Q30 > 90% and PF > 80% thresholds [4]

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- WES data mapped to hg38 using BWA aligner v.0.7.17

- RNA-seq data mapped to hg38 using STAR aligner v2.4.2

- Gene expression quantification with Kallisto v0.43.0

- Somatic variant calling with Strelka v2.9.10

- Variant filtration using depth (tumor ≥10 reads, normal ≥20 reads) and VAF (tumor ≥0.05, normal ≤0.05) thresholds [4]

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful NGS experimentation requires carefully selected reagents and solutions at each workflow stage. Table 3 catalogizes key research reagents with their specific functions in NGS protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Manufacturer | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MGIEasy UDB Universal Library Prep Set [12] | MGI | Library preparation for NGS | Used in comparative WES study, provides uniform performance across platforms |

| SureSelect XTHS2 DNA/RNA Kit [4] | Agilent Technologies | Library construction from FFPE samples | Enables integrated DNA-RNA sequencing from challenging samples |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit [4] | Illumina | RNA library preparation | Maintains strand specificity for transcriptome analysis |

| SureSelect Human All Exon V7 + UTR [4] | Agilent Technologies | Exome capture probe | Captures exonic regions and untranslated regions for comprehensive analysis |

| TargetCap Core Exome Panel v3.0 [12] | BOKE Bioscience | Exome capture | One of four platforms showing comparable performance on DNBSEQ-T7 |

| xGen Exome Hyb Panel v2 [12] | Integrated DNA Technologies | Exome capture | Demonstrated high technical stability in comparative evaluation |

| MGIEasy Fast Hybridization and Wash Kit [12] | MGI | Hybridization and wash steps | Enabled uniform performance across different probe brands |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay [12] | Thermo Fisher Scientific | DNA quantification | Provides accurate concentration measurements for library normalization |

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The NGS technology landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several convergent trends shaping its future trajectory. Accuracy improvements represent a key focus, with Oxford Nanopore's duplex sequencing now achieving Q30 accuracy (>99.9%) and PacBio's HiFi reads reaching Q30-Q40 precision [10]. The integration of multi-omic data from a single experiment is becoming increasingly feasible, as demonstrated by PacBio's SPRQ chemistry which captures both DNA sequence and chromatin accessibility information [10].

The NGS market is projected to grow significantly, with estimates suggesting expansion from $3.88 billion in 2024 to $16.57 billion by 2033, representing a 17.5% compound annual growth rate [15]. This growth is fueled by rising adoption in clinical diagnostics, particularly oncology, and expanding applications in personalized medicine [15] [16].

Emerging technologies like Roche's SBX (Sequencing by Expansion) promise to further transform the landscape by encoding DNA into surrogate Xpandomer molecules 50 times longer than target DNA, enabling highly accurate single-molecule nanopore sequencing [13]. Simultaneously, the continued reduction in sequencing costs - with Ultima Genomics now offering a $80 genome - is democratizing access to genomic technologies [13].

For researchers validating NGS-derived chemogenomic signatures, the current technology landscape offers multiple orthogonal validation pathways, including platform cross-comparison, integrated DNA-RNA sequencing, and long-read verification of complex genomic regions. As these technologies continue to mature and converge, they will further enhance the precision and comprehensiveness of genomic analyses across basic research, drug development, and clinical applications.

Mutational signatures, which are specific patterns of somatic mutations left in the genome by various DNA damage and repair processes, have emerged as powerful tools for understanding cancer development and therapeutic opportunities [17]. These signatures provide insights into the mutational processes a tumor has undergone, revealing its molecular history and potential vulnerabilities [18]. The critical link between these signatures and drug response lies in their ability to identify specific DNA repair deficiencies and other molecular alterations that can be therapeutically exploited, enabling more precise treatment strategies and improved patient outcomes [18]. This guide compares approaches for identifying and validating these signatures, with a focus on their application in predicting drug response and target vulnerability.

Comparative Analysis of Mutational Signature Detection Methodologies

Comparison of Sequencing Approaches for Mutational Signature Analysis

| Sequencing Method | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Sequences entire genome; detects mutations in coding and non-coding regions [8]. | Comprehensive mutational landscape; ideal for de novo signature discovery [18]. | Higher cost and computational burden; larger data storage needs [8]. | Research applications, discovery of novel signatures, biomarker identification. |

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targets protein-coding regions (exons) only [8]. | Cost-effective; focuses on functionally relevant regions [17]. | May miss clinically relevant non-coding mutations; less comprehensive than WGS [17]. | Large-scale cohort studies, validating known signatures in clinical contexts. |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Focuses on curated sets of cancer-related genes (e.g., 50-500 genes) [17]. | Clinical feasibility; cost-effective for known biomarkers; faster turnaround [17]. | Limited gene coverage; may not capture full signature complexity [17]. | Clinical diagnostics, therapy selection, patient stratification in trials. |

Targeted sequencing panels, despite their limited scope, can effectively reflect WES-level mutational signatures, making them suitable for many clinical applications. Research shows that panels targeting 200-400 cancer-related genes can achieve high similarity to WES-level signatures, though the optimal number varies by cancer type [17].

Clinically Actionable Mutational Signatures and Their Therapeutic Implications

| Mutational Signature | Associated Process/Deficiency | Therapeutic Implications | Cancer Types with Prevalence | Clinical Evidence Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRd) - SBS3 | Defective DNA double-strand break repair [18]. | Sensitivity to PARP inhibitors (e.g., olaparib) and platinum chemotherapy [18]. | Ovarian, breast, pancreatic, prostate [18]. | Strong; validated predictive biomarker in clinical trials. |

| Mismatch Repair Deficiency (MMRd) | Defective DNA mismatch repair [19]. | Sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1) [19]. | Colorectal, endometrial, gastric [19]. | Strong; FDA-approved for immunotherapy selection. |

| APOBEC Hypermutation | Activity of APOBEC cytidine deaminases [18]. | Emerging target for APOBEC inhibitors; potential biomarker for immunotherapy [18]. | Bladder, breast, lung, head/neck [18]. | Preclinical and early clinical investigation. |

| Polymerase Epsilon Mutation | Ultramutated phenotype [18]. | Prognostic implications; potential implications for immunotherapy [18]. | Endometrial, colorectal [18]. | Clinical observation, ongoing studies. |

Experimental Protocols for Signature Identification and Validation

Multimodal Mutational Signature Analysis Workflow

Diagram: Multimodal Mutational Signature Analysis. This workflow integrates multiple mutation types (SBS, Indel, Structural Variants) for improved signature resolution and clinical prediction.

Protocol Details:

- Sample Preparation: Process tumor and matched normal samples (FFPE or fresh frozen) according to standard WGS protocols [18].

- Sequencing: Perform WGS to a minimum coverage of 60x for tumor and 30x for normal samples using platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq or PacBio Revio [8].

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), and structural variants using callers like Mutect2 and Manta [18].

- Spectrum Generation: Categorize SNVs into 96 trinucleotide contexts and indels into 83 categories according to COSMIC standards [17] [18].

- Signature Analysis: Extract mutational signatures using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) with tools like SigProfiler, then refit using COSMIC reference signatures [18].

- Multimodal Integration: Jointly analyze SNV and indel signatures to improve resolution of featureless signatures like SBS3, enabling identification of subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes [18].

Orthogonal Functional Validation of Signature-Directed Therapies

Diagram: Orthogonal Validation Workflow. This approach combines multiple experimental methods to validate therapeutic hypotheses generated from mutational signatures.

Validation Protocol:

- Genome-wide CRISPR Screens: Conduct positive and negative selection screens using libraries like Brunello (4 sgRNAs/gene) in models with specific mutational signatures. Identify genes whose knockout sensitizes to signature-relevant drugs (e.g., Prexasertib in HR-deficient models) [20].

- Chemical-Genetic Interaction Profiling: Treat parasite RNAi libraries (RIT-seq) with drugs to identify resistance mechanisms, applying this principle to cancer models to map genetic networks underlying signature-associated therapeutic vulnerabilities [21].

- Proteogenomic Integration: Combine transcriptional signatures with proteomic analysis of chromatin complexes to identify druggable mediators of therapy response, as demonstrated in the PA2G4-MYC axis in 3q26 AML [22].

- Patient-Derived Xenografts: Validate signature-directed therapeutic efficacy in PDX models with defined mutational signatures, assessing tumor regression and biomarker modulation [22].

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Signature Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions for Mutational Signature Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Key Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X Plus [8] | High-throughput WGS/WES | Enables large-scale cohort sequencing for signature discovery. |

| PacBio Revio [8] | Long-read sequencing | Resolves complex genomic regions and structural variants. | |

| Oxford Nanopore MinION [23] | Portable real-time sequencing | Rapid signature assessment in clinical settings. | |

| Signature Analysis Tools | SigProfiler [18] | De novo signature extraction | Gold-standard for COSMIC-compliant signature analysis. |

| deconstructSigs [17] | Signature refitting | Assigns known signatures to individual samples. | |

| Functional Validation | Brunello CRISPR Library [20] | Genome-wide knockout | Identifies genes modulating signature-associated drug response. |

| MSK-IMPACT Panel [17] | Targeted sequencing (468 genes) | Validates signatures in clinical-grade targeted sequencing. | |

| Bioinformatics | Enrichr/Reactome [19] | Pathway analysis | Maps signature-associated mutations to biological pathways. |

| CMap/L1000 [22] | Connectivity mapping | Identifies signature-targeting small molecules. |

Mutational signatures provide a critical link between tumor genomics and therapeutic strategy, moving beyond single-gene biomarkers to capture the complex molecular history of malignancies. The comparative data presented demonstrates that while targeted sequencing offers clinical utility for known signatures, WGS-based multimodal approaches provide superior resolution for identifying novel therapeutic vulnerabilities. The experimental protocols and reagents detailed enable robust identification and validation of these signatures, supporting their integration into drug development pipelines and clinical trial design. As these approaches mature, mutational signatures are poised to become standard biomarkers for therapy selection, fundamentally enhancing precision oncology.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the reading of DNA, RNA, and epigenetic modifications at an unprecedented scale, transforming sequencers into general-purpose molecular readout devices [10]. In chemogenomics, which studies the complex interactions between cellular networks and chemical compounds, extracting robust biological meaning from NGS data is paramount for identifying novel drug targets and biomarkers. This process involves multiple data transformations, each producing specific file types and requiring specialized analytical approaches [24]. The path from biological sample to scientific insight begins with sequencing instruments that generate raw electrical signals and base calls, proceeds through quality control and alignment where reads are mapped to reference genomes, and culminates in quantification, variant calling, and biological annotation [24]. In the context of chemogenomic signature validation, each step must be rigorously optimized and validated to ensure that the resulting insights accurately reflect true biological responses to chemical perturbations rather than technical artifacts.

The scale of NGS data presents significant computational challenges, with experiments generating massive datasets containing millions to billions of sequencing reads [24]. This data volume necessitates efficient compression methods, sophisticated indexing schemes for random access to specific genomic regions, standardized formats for interoperability between analysis tools, and rich metadata annotation for complex experimental designs [24]. The analytical workflow generally follows three core stages: primary analysis assessing raw sequencing data for quality, secondary analysis converting data to aligned results, and tertiary analysis where conclusions are made about genetic features or mutations of interest [25]. For chemogenomic applications, this workflow must be specifically tailored to detect subtle, chemically-induced genomic changes and distinguish them from background biological noise, often requiring specialized statistical methods and validation frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of NGS Technologies and Performance

Technology Platforms and Specifications

The NGS landscape in 2025 features diverse technologies from multiple companies, each with distinct strengths and limitations for chemogenomic applications [10]. Understanding these platform characteristics is essential for selecting appropriate sequencing methods for specific research questions. Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology dominates the market due to its high accuracy and throughput, with the latest NovaSeq X series capable of outputting up to 16 terabases of data (26 billion reads) per flow cell [10]. This platform excels in applications requiring high base-level accuracy, such as variant calling and gene expression quantification. In contrast, third-generation technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enable long-read sequencing, with PacBio's HiFi reads combining length advantages (10-25 kb) with high accuracy (Q30-Q40, or 99.9-99.99%), and ONT providing the unique capability of ultra-long reads (up to 2 Mb) with recent duplex chemistry achieving Q30 (>99.9%) accuracy [10]. Each technology exhibits distinct error profiles: Illumina has low substitution error rates, while Nanopore has higher indel rates particularly in homopolymer regions, and PacBio errors are random and thus correctable through consensus approaches [10].

For chemogenomic studies, technology selection depends on the specific analytical goals. Illumina platforms are ideal for detecting single nucleotide variants and quantifying gene expression changes in response to compound treatment, while long-read technologies enable resolution of complex genomic rearrangements, full-length isoform sequencing to detect alternative splicing events induced by chemical perturbations, and direct detection of epigenetic modifications that may be influenced by drug treatment [10]. The emergence of multi-omics platforms, such as PacBio's SPRQ chemistry which simultaneously extracts DNA sequence and chromatin accessibility information from the same molecule, provides particularly powerful tools for understanding the multidimensional effects of chemical compounds on biological systems [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms for Chemogenomic Applications

| Platform | Primary Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Error Profile | Ideal Chemogenomic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 50-300 bp | >99.9% (Q30) | Low substitution errors | Variant detection, gene expression profiling, high-throughput compound screening |

| PacBio Revio | Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | 10-25 kb (HiFi) | 99.9-99.99% (Q30-Q40) | Random errors | Structural variant detection, isoform sequencing, epigenetic modification analysis |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | 1 kb-2 Mb | >99.9% (Q30 duplex) | Indels, homopolymer errors | Real-time sequencing, direct RNA sequencing, large structural variant detection |

| PacBio SPRQ | SMRT with transposase labeling | 10-25 kb | 99.9-99.99% (Q30-Q40) | Random errors | Integrated genome sequence and chromatin accessibility analysis |

Analytical Performance Benchmarks

Rigorous analytical validation is essential for establishing the reliability of NGS-based chemogenomic insights. The NCI-MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial provides a comprehensive framework for NGS assay validation that can be adapted for chemogenomic applications [26]. This validation approach demonstrated that a properly optimized NGS assay can achieve an overall sensitivity of 96.98% for detecting 265 known mutations with 99.99% specificity across multiple clinical laboratories [26]. The validation established distinct limits of detection for different variant types: 2.8% for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), 10.5% for small insertion/deletions (indels), 6.8% for large indels (gap ≥4 bp), and four copies for gene amplification [26]. These performance characteristics are particularly relevant for chemogenomic studies that aim to detect rare mutant subpopulations emerging under chemical selection pressure.

The reproducibility of NGS assays is another critical performance parameter, especially when evaluating compound-induced genomic changes across multiple experimental batches. The NCI-MATCH validation demonstrated that high reproducibility is achievable, with a 99.99% mean interoperator pairwise concordance across four independent laboratories [26]. This level of reproducibility provides confidence that observed genomic changes truly reflect biological responses to chemical perturbations rather than technical variability. For chemogenomic applications, establishing similar reproducibility metrics through inter-laboratory validation studies is essential, particularly when identifying signatures for drug development decisions. The use of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) clinical specimens in the validation approach further enhances its relevance to real-world chemogenomic studies that often utilize archived samples [26].

Table 2: Analytical Performance Metrics from NCI-MATCH NGS Validation Study

| Performance Parameter | Performance Value | Implication for Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Sensitivity | 96.98% | High confidence in detecting true compound-induced mutations |

| Specificity | 99.99% | Minimal false positives in chemogenomic signature identification |

| SNV Limit of Detection | 2.8% | Ability to detect minor mutant subpopulations emerging under treatment |

| Indel Limit of Detection | 10.5% | Sensitivity to frame-shift mutations and small insertions/deletions |

| Large Indel Limit of Detection | 6.8% | Detection of larger structural variations induced by compound treatment |

| Interoperator Reproducibility | 99.99% mean concordance | Reliable signature identification across different laboratories and operators |

Experimental Protocols for NGS Data Generation and Analysis

Sample Processing and Library Preparation

The foundation of reliable chemogenomic insights begins with robust sample processing and library preparation methods. In the NCI-MATCH trial framework, clinical biopsy samples underwent rigorous preanalytical histologic assessment by board-certified pathologists to evaluate tumor content, a critical step for ensuring adequate cellular material for subsequent analysis [26]. For chemogenomic studies investigating compound effects on cell lines or patient-derived models, similar quality assessment is essential, including evaluation of cell viability, potential contamination, and morphological features. Following pathological assessment, nucleic acids (both DNA and RNA) are extracted using standardized protocols optimized for the specific sample type, whether fresh frozen, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), or other preservation methods [26]. The NCI-MATCH protocol utilized FFPE clinical tumor specimens with various histopathologic diagnoses to include a wide variety of known somatic variants, demonstrating the applicability of this approach to diverse sample types relevant to chemogenomics [26].

Library preparation represents a crucial gateway in the NGS workflow where significant technical bias can be introduced if not carefully controlled. The NCI-MATCH assay employed the Oncomine Cancer Panel using AmpliSeq chemistry, a targeted approach focusing on 143 genes with clinical relevance [26]. For comprehensive chemogenomic studies, library preparation must be tailored to the specific research question—whether whole genome sequencing for unbiased mutation discovery, whole transcriptome sequencing for gene expression profiling, or targeted sequencing for focused investigation of specific pathways. The use of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during library preparation is particularly valuable for chemogenomic applications, as these molecular barcodes enable correction for amplification biases and more accurate quantification of transcript abundance or mutation frequency in response to compound treatment [25]. For RNA sequencing applications, the selection of stranded RNA sequencing kits preserves information about the transcriptional strand origin, enabling more accurate annotation of antisense transcription and overlapping genes that may be regulated by chemical compounds [25].

Sequencing and Primary Data Analysis

Following library preparation, sequencing execution and primary data analysis form the next critical phase. The NCI-MATCH trial utilized the Personal Genome Machine (PGM) sequencer with locked standard operating procedures across four networked CLIA-certified laboratories [26]. For chemogenomic studies, consistent sequencing depth and coverage must be maintained across all samples in a comparative experiment to ensure equitable detection power. The primary analysis begins with the conversion of raw sequencing data from platform-specific formats (such as Illumina's BCL files or Nanopore's FAST5/POD5 files) into the standardized FASTQ format [25] [24]. This conversion is typically managed by instrument software (e.g., bcl2fastq for Illumina), which also performs demultiplexing to separate pooled samples based on their unique index sequences [25].

Quality assessment of the raw sequencing data is then performed using multiple metrics, including total yield (number of base reads), cluster density (measure of purity of base call signals), phasing/prephasing (percentage of base signal lost in each cycle), and alignment rates [25]. A critical quality metric is the Phred quality score (Q score), which measures the probability of an incorrect base call using the equation Q = -10 log10 P, where P is the error probability [25] [27]. A Q score >30, representing a <0.1% base call error rate, is generally considered acceptable for most applications [25]. Tools like FastQC provide comprehensive quality assessment through visualization of per-base and per-sequence quality scores, sequence content, GC content, and duplicate sequences [25] [27]. For chemogenomic studies, careful attention to these quality metrics at the primary analysis stage is essential for identifying potential technical batch effects that could confound the identification of compound-induced biological signatures.

Secondary Analysis: Alignment and Variant Calling

Secondary analysis transforms quality-assessed sequencing reads into biologically interpretable data through alignment to reference genomes and identification of genomic features. The process begins with read cleanup, which involves removing adapter sequences, trimming low-quality bases (typically using a Phred score cutoff of 30), and potentially merging paired-end reads [25]. For chemogenomic studies utilizing degraded samples or those with specific characteristics, additional cleanup steps may be necessary, such as removing reads shorter than a certain length or correcting sequence biases introduced during library preparation [25]. For RNA sequencing data, additional quality assessment may include quantification of ribosomal RNA contaminants and determination of strandedness if a directional RNA sequencing kit was used [25].

Sequence alignment represents one of the most computationally intensive steps in the NGS workflow, where cleaned reads in FASTQ format are mapped to a reference genome using specialized algorithms [25]. Common alignment tools include BWA and Bowtie 2, which offer a reliable balance between computational efficiency and mapping quality [25]. The choice of reference genome is critical—for human studies, the current standard is GRCh38 (hg38), though the previous GRCh37 (hg19) is still widely used [25]. The output of alignment is typically stored in Binary Alignment Map (BAM) format, a compressed, efficient representation of the mapping results [24]. For chemogenomic time-course experiments or dose-response studies, consistent alignment parameters and reference genomes across all samples are essential for comparative analysis.

Following alignment, variant calling identifies mutations and other genomic features that differ from the reference genome. The NCI-MATCH assay was designed to detect and report 4,066 predefined genomic variations across 143 genes, including single-nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy number variants, and gene fusions [26]. For chemogenomic studies, variant calling must be optimized based on the specific experimental design—somatic mutation detection in chemically-treated versus control samples, identification of allele-specific expression changes, or detection of fusion genes induced by compound treatment. The variant calling output is typically stored in Variant Call Format (VCF) files, which catalog all identified variants along with quality metrics and supporting evidence [25]. For RNA sequencing experiments, gene expression quantification produces count matrices that tabulate reads mapping to each gene across all samples, enabling subsequent differential expression analysis [25] [24].

Tertiary Analysis: Extracting Chemogenomic Insights

Tertiary analysis represents the transition from genomic observations to biological insights, where aligned sequencing data and identified variants are interpreted in the context of chemogenomic questions. This stage begins with comprehensive annotation of genomic features, connecting identified variants to functional consequences (e.g., missense, nonsense, splice site variants), population frequency databases, predicted pathogenicity scores, and known drug-gene interactions [26]. For chemogenomic applications, this annotation is particularly important for distinguishing driver mutations that may mediate compound sensitivity from passenger mutations with minimal functional impact.

Pathway and functional analysis then places individually significant genes into broader biological context, identifying networks and processes significantly enriched among compound-induced genomic changes. For gene expression data, this typically involves gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) or overrepresentation analysis of Gene Ontology terms, KEGG pathways, or other curated gene sets relevant to the mechanism of action of the tested compounds [27]. For mutation data, pathway analysis may identify biological processes with significant mutational burden following chemical treatment. The development of chemogenomic signatures often involves integrating multiple data types—such as mutation status, gene expression changes, and copy number alterations—into multi-parameter models that predict compound sensitivity or resistance.

The final stage of tertiary analysis focuses on validation of chemogenomic signatures using orthogonal methods, a critical requirement for establishing robust, actionable insights [26]. This validation may include functional assays using RNA interference or CRISPR-based approaches to confirm putative targets, direct measurement of compound-target engagement using cellular thermal shift assays or drug affinity responsiveness, or correlation of genomic signatures with compound sensitivity across large panels of cell line models. The NCI-MATCH trial established a framework for classifying genomic alterations based on levels of evidence, ranging from variants credentialed for FDA-approved drugs to those supported by preclinical inferential data [26]. Similar evidence-based classification should be applied to chemogenomic signatures to prioritize those with the strongest support for guiding drug development decisions.

Visualization Methods for NGS Data Interpretation

Quality Control and Exploratory Visualization

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting the massive datasets generated in NGS-based chemogenomic studies. Quality control visualization begins with tools like FastQC, which provides graphs representing quality scores across all bases, sequence content, GC distribution, and adapter contamination [25] [27]. These visualizations enable rapid assessment of potential technical issues that could compromise downstream analysis, such as declining quality toward read ends, biased nucleotide composition, or overrepresented sequences indicating contamination [27]. For chemogenomic studies comparing multiple compounds or doses, quality metrics should be visualized across all samples simultaneously to identify batch effects or sample-specific outliers that might confound biological interpretation.

Following quality assessment, exploratory data analysis visualization techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduce the dimensionality of complex NGS data, enabling visualization of sample relationships in two-dimensional space [27]. In PCA plots, samples with similar genomic profiles cluster together, allowing researchers to identify patterns related to experimental conditions, such as separation of compound-treated versus control samples, dose-dependent trends, or time-course trajectories [27]. For chemogenomic applications, PCA and similar techniques (t-SNE, UMAP) are invaluable for assessing overall data quality, identifying potential confounding factors, and generating initial hypotheses about compound-specific effects based on global genomic profiles.

Genomic Feature Visualization

Visualization of genomic features in their chromosomal context provides critical biological insights that may be missed in tabular data summaries. Genome browsers such as the Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV), University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser, or Tablet enable navigation across genomic regions with simultaneous display of multiple data types [25] [28]. These tools visualize read alignments (BAM files), variant calls (VCF files), gene annotations, and other genomic features in coordinated views, allowing researchers to assess the validity of specific variants, examine read support for mutation calls, visualize splice junctions in RNA-seq data, and identify potential artifacts [25] [28]. For chemogenomic studies, genome browser visualization is particularly valuable for examining variants in genes of interest, assessing compound-induced changes in splicing patterns, and validating structural variations suggested by analytical algorithms.

Specialized visualization approaches have been developed for specific NGS applications. For gene expression data, heatmaps effectively display expression patterns across multiple samples and genes, highlighting coordinated transcriptional responses to compound treatment [27]. Circular layouts are commonly used in whole genome sequencing to display overall genomic features and structural variations [27]. Network graphs visualize co-expression relationships or functional interactions between genes modulated by chemical compounds [27]. For epigenomic studies such as ChIP-seq or methylation analyses, heatmaps and histograms effectively display enrichment patterns or methylation rates across genomic regions [27]. The selection of appropriate visualization techniques should be guided by the specific research question and data type, with the goal of making complex chemogenomic data accessible and interpretable.

Programmatic Visualization with R and Bioconductor

Programmatic visualization using R and Bioconductor provides flexible, reproducible approaches for creating publication-quality figures from NGS data. The GenomicAlignments and GenomicRanges packages enable efficient handling of aligned sequencing data, allowing researchers to calculate and visualize coverage across genomic regions of interest [29]. For example, base-pair coverage can be computed from BAM files and plotted to visualize read density across genes or regulatory elements, revealing compound-induced changes in transcription or chromatin accessibility [29]. Visualization of exon-level data can be achieved by extracting genomic coordinates from transcript databases (TxDb objects) and plotting exon structures as annotated arrows, indicating strand orientation and exon boundaries [29].

Advanced genomic visualization packages like Gviz provide specialized frameworks for creating sophisticated multi-track figures that integrate diverse data types [29]. These tools enable simultaneous visualization of genome axis tracks, gene model annotations, coverage plots from multiple samples, variant positions, and other genomic features in coordinated views [29]. For chemogenomic studies, such integrated visualizations are invaluable for correlating compound-induced changes across different molecular layers—such as connecting mutations in specific genes to changes in their expression or splicing patterns. The reproducibility of programmatic approaches ensures that visualizations can be consistently regenerated as data is updated, facilitating iterative analysis and refinement of chemogenomic insights throughout the research process.

Core Analysis Tools and Software

The computational analysis of NGS data for chemogenomic applications requires a sophisticated toolkit of bioinformatic software and programming resources. The core analysis typically involves three primary stages—primary, secondary, and tertiary analysis—each with specialized tools [25]. Primary analysis, which assesses raw sequencing data quality, is often performed by instrument-embedded software like bcl2fastq for Illumina platforms, generating FASTQ files with base calls and quality scores [25]. Secondary analysis, comprising read cleanup, alignment, and variant calling, utilizes tools such as FastQC for quality assessment, BWA and Bowtie 2 for alignment, and variant callers like GATK or SAMtools for identifying genomic variations [25] [27]. Tertiary analysis focuses on biological interpretation using tools for annotation (e.g., SnpEff, VEP), pathway analysis (e.g., GSEA, clusterProfiler), and specialized chemogenomic databases connecting genomic features to compound sensitivity.

A critical consideration in NGS data analysis is the computational infrastructure required to handle massive datasets, which often necessitates access to advanced computing resources through private networks or cloud platforms [25]. Programming skills in Python, Perl, R, and Bash scripting are highly valuable, typically performed within Linux/Unix-like operating systems and command-line environments [25]. For researchers without extensive computational backgrounds, user-friendly platforms like the CSI NGS Portal provide online environments for automated NGS data analysis and sharing, lowering the barrier to sophisticated genomic analysis [27]. The selection of specific tools should be guided by the experimental design, with different software packages optimized for whole genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, methylation analyses, or exome sequencing applications [27].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for NGS-Based Chemogenomic Analysis

| Analysis Stage | Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analysis | Base Calling | bcl2fastq | Convert raw data to FASTQ format |

| Quality Assessment | FastQC | Comprehensive quality control reports | |

| Secondary Analysis | Read Cleanup | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt | Remove adapters, quality trimming |

| Alignment | BWA, Bowtie 2, HISAT2 | Map reads to reference genomes | |

| Variant Calling | GATK, SAMtools, FreeBayes | Identify SNPs, indels, structural variants | |

| Expression Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq | Generate gene expression count matrices | |

| Tertiary Analysis | Variant Annotation | SnpEff, VEP | Functional consequence prediction |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Identify statistically significant expression changes | |

| Pathway Analysis | GSEA, clusterProfiler | Functional enrichment analysis | |

| Visualization | IGV, Gviz, Tablet | Genomic data visualization |

Research Reagent Solutions

Experimental validation of NGS-derived chemogenomic insights requires specialized research reagents and assay systems. Cell line models represent fundamental reagents, with well-characterized cancer cell lines (e.g., NCI-60 panel) or primary cell models providing biologically relevant systems for testing compound responses. The NCI-MATCH trial utilized formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) clinical specimens with pathologist-assessed tumor content, highlighting the importance of well-characterized biological materials [26]. For nucleic acid extraction, standardized kits from commercial providers ensure high-quality DNA and RNA suitable for NGS library preparation, with specific protocols optimized for different sample types including FFPE tissue [26].

Targeted sequencing panels, such as the Oncomine Cancer Panel used in the NCI-MATCH trial, provide focused content for efficient assessment of clinically relevant genomic regions [26]. These panels typically employ AmpliSeq or similar technologies to amplify targeted regions across key genes, enabling sensitive detection of mutations with known or potential therapeutic implications [26]. For functional validation, CRISPR/Cas9 reagents enable genomic editing to confirm the functional role of putative resistance or sensitivity genes, while RNA interference tools (siRNA, shRNA) provide alternative approaches for gene knockdown studies. High-content screening assays, including cellular viability assays, apoptosis detection, and pathway-specific reporters, provide phenotypic readouts that connect genomic features to functional compound responses, completing the cycle from NGS discovery to biological validation.

Experimental Protocols for Orthogonal Validation

Orthogonal validation of NGS-derived chemogenomic signatures requires carefully designed experimental protocols that confirm findings using independent methodological approaches. The NCI-MATCH trial established a framework for classifying genomic alterations based on levels of evidence, with Level 1 representing variants credentialed for FDA-approved drugs and Level 3 based on preclinical inferential data [26]. This evidence-based classification can be adapted for chemogenomic signature validation, beginning with computational prediction and progressing through experimental confirmation.

Functional validation typically begins with genetic perturbation experiments using CRISPR-based gene knockout or RNA interference-mediated knockdown in model cell lines, assessing how these manipulations alter compound sensitivity [26]. For signatures suggesting direct compound-target interactions, biochemical assays such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or drug affinity responsiveness target stability (DARTS) can confirm physical engagement between compounds and their putative protein targets. Proteomic approaches using mass spectrometry-based quantification provide orthogonal confirmation of protein-level changes corresponding to transcriptomic alterations identified by RNA sequencing. For signatures with potential clinical translation, validation in patient-derived xenograft models or correlation with clinical response data in appropriate patient cohorts provides the highest level of evidence for actionable chemogenomic insights.

Table 4: Orthogonal Validation Methods for NGS-Derived Chemogenomic Signatures

| Validation Method | Experimental Approach | Information Gained | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Perturbation | CRISPR knockout, RNAi knockdown | Causal relationship between gene and compound response | Medium-High |

| Biochemical Binding | CETSA, DARTS, SPR | Direct physical interaction between compound and target | High |

| Proteomic Analysis | Mass spectrometry, Western blot | Protein-level confirmation of transcriptomic changes | Medium |

| Cellular Phenotyping | High-content imaging, viability assays | Functional consequences of genomic alterations | Medium |

| Preclinical Models | PDX models, organoids | Relevance in more physiological systems | High |

| Clinical Correlation | Retrospective analysis of patient responses | Direct clinical translatability | Highest |

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies for Deriving and Applying Signatures

Integrated multi-omic profiling represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, enabling a comprehensive understanding of biological systems by simultaneously analyzing multiple molecular layers. The convergence of whole-exome sequencing (WES), RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), and epigenetic profiling technologies provides unprecedented insights into the complex interplay between genetic predispositions, transcriptional regulation, and epigenetic modifications that drive disease pathogenesis and therapeutic responses [30]. This integrated approach is particularly vital for validating next-generation sequencing (NGS)-derived chemogenomic signatures, as it allows researchers to bridge the gap between identified genomic variants and their functional consequences across molecular layers.

The analytical validation of NGS assays, as demonstrated in large-scale precision medicine trials like NCI-MATCH, requires rigorous benchmarking to ensure reliability across multiple clinical laboratories [26]. Such validation establishes critical performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility that are essential for generating clinically actionable insights. As the field advances, integrated multi-omics approaches are increasingly being applied to unravel the biological and clinical insights of complex diseases, particularly in cancer research where molecular heterogeneity remains a fundamental challenge [31].

Performance Benchmarking of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

Method Comparison and Evaluation Frameworks

The computational integration of multi-omics data presents significant challenges, necessitating rigorous benchmarking of different integration strategies. A comprehensive evaluation of joint dimensionality reduction (jDR) approaches revealed that method performance varies substantially across different analytical contexts [32]. Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (intNMF) demonstrated superior performance in sample clustering tasks, while Multiple co-inertia analysis (MCIA) offered consistently effective behavior across multiple analysis contexts [32].

Benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated integration methods using three complementary approaches: (1) performance in retrieving ground-truth sample clustering from simulated multi-omics datasets, (2) prediction accuracy for survival, clinical annotations, and known pathways using TCGA cancer data, and (3) classification accuracy for multi-omics single-cell data [32]. These evaluations consistently demonstrate that no single method universally outperforms all others across every metric, highlighting the importance of selecting integration approaches based on specific research objectives.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Multi-Omics Integration Methods for Cancer Subtyping

| Integration Method | Mathematical Foundation | Clustering Accuracy | Survival Prediction | Biological Interpretability | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intNMF | Non-negative Matrix Factorization | High | Moderate | High | Sample clustering, distinct subtypes |

| MCIA | Principal Component Analysis | Moderate | High | High | Multi-context analysis, visualization |

| MOFA | Factor Analysis | Moderate | High | High | Capturing shared and unique variation |

| SNF | Similarity Network Fusion | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Network-based integration |

| iCluster | Factor Analysis | Moderate | High | Moderate | Genomic data integration |

Impact of Data Type Combinations on Integration Performance

Contrary to intuitive expectations, simply incorporating more omics data types does not always improve integration performance. Systematic evaluation of eleven different combinations of four primary omics data types (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics) revealed situations where integrating additional data types negatively impacts method performance [33]. This counterintuitive finding underscores the importance of strategic data selection rather than exhaustive data inclusion.

Research has identified particularly effective combinations for specific cancer types. For example, in breast cancer (BRCA), integrating gene expression with DNA methylation data frequently yields superior subtyping results, while in kidney cancer (KIRC), combining gene expression with miRNA expression proves most effective [33]. These findings emphasize that the optimal multi-omics combination is context-dependent and should be informed by biological knowledge of the disease system under investigation.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of NGS Assays in Clinical Validation

| Performance Metric | SNVs | Small Indels | Large Indels (≥4 bp) | Gene Amplifications | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | 96.98% |

| Specificity | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | 99.99% |

| Limit of Detection | 2.8% | 10.5% | 6.8% | 4 copies | Variant-dependent |

| Reproducibility | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | >99.9% | 99.99% |

Experimental Designs and Methodological Protocols

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Disease Mechanism Elucidation

A comprehensive multi-omics study on post-operative recurrence in stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) exemplifies a robust integrated profiling approach [31]. This research combined whole-exome sequencing, nanopore sequencing, RNA-seq, and single-cell RNA sequencing on samples from 122 stage I NSCLC patients (57 with recurrence, 65 without recurrence) to identify molecular determinants of disease recurrence. The experimental workflow incorporated matched tumor and adjacent normal tissues from fresh frozen (FF) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens to maximize analytical robustness while addressing practical clinical constraints.

The analytical approach implemented in this study exemplifies best practices for integrated multi-omics analysis: (1) genomic characterization of somatic mutations, copy number variations, and structural variants; (2) epigenomic profiling of differentially methylated regions using nanopore sequencing; (3) transcriptomic analysis of gene expression patterns; and (4) single-cell resolution decomposition of the tumor microenvironment [31]. This layered analytical strategy enabled the identification of coordinated molecular events across biological layers that would remain undetectable in single-omics analyses.

Diagram 1: Integrated multi-omics workflow for NSCLC recurrence analysis. This workflow demonstrates the parallel processing of multi-omics data streams and their integration for clinical stratification.

Quality Control Protocols for Multi-Omics Data

Rigorous quality control is paramount for generating reliable multi-omics data, particularly given the technical variability across different assay platforms. A comprehensive quality control framework for epigenomics and transcriptomics data outlines specific metrics and mitigation strategies for eleven different assay types [34]. For WES data, essential quality metrics include sequencing depth (typically >100x for somatic variants), coverage uniformity, base quality scores, and contamination estimates. For RNA-seq data, critical parameters include ribosomal RNA content, library complexity, transcript integrity numbers, and gene body coverage. For epigenetic profiling methods such as bisulfite sequencing or ChIP-seq, key metrics include bisulfite conversion efficiency, CpG coverage, enrichment efficiency, and peak distribution patterns.

The NCI-MATCH trial established a robust framework for analytical validation of NGS assays across multiple clinical laboratories, achieving an overall sensitivity of 96.98% for 265 known mutations and 99.99% specificity [26]. This validation approach incorporated formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) clinical specimens and cell lines to assess reproducibility across variant types, with a 99.99% mean inter-operator pairwise concordance across four independent laboratories [26]. The establishment of such rigorous quality standards is essential for generating clinically actionable insights from multi-omics profiling.

Biological Insights from Integrated Multi-Omics Studies

Molecular Determinants of Cancer Recurrence

The integrated analysis of WES, RNA-seq, and epigenetic data in stage I NSCLC identified distinct molecular features associated with post-operative recurrence [31]. Genomic characterization revealed that recurrent tumors exhibited significantly higher homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) scores and enriched APOBEC-related mutational signatures, indicating increased genomic instability. Furthermore, specific TP53 missense mutations in the DNA-binding domain were associated with significantly shorter time to recurrence, highlighting their potential prognostic value.

Epigenomic profiling through nanopore sequencing identified pronounced DNA hypomethylation in recurrent NSCLC, with PRAME identified as a significantly hypomethylated and overexpressed gene in recurrent lung adenocarcinoma [31]. Mechanistically, hypomethylation at the TEAD1 binding site was shown to facilitate transcriptional activation of PRAME, and functional validation demonstrated that PRAME inhibition restrains tumor metastasis through downregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related genes. This finding exemplifies how multi-omics integration can identify epigenetically dysregulated oncogenic drivers with potential therapeutic implications.

Tumor Ecosystem Characterization

Single-cell RNA sequencing integrated with bulk multi-omics data revealed essential ecosystem features associated with NSCLC recurrence [31]. The analysis identified enrichment of AT2 cells with higher copy number variation burden, exhausted CD8+ T cells, and Macro_SPP1 macrophages in recurrent LUAD, along with reduced interaction between AT2 and immune cells. This comprehensive ecosystem characterization provides insights into the immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates disease recurrence despite surgical resection.

Multi-omics clustering stratified NSCLC patients into four distinct subclusters with varying recurrence risk and subcluster-specific therapeutic vulnerabilities [31]. This stratification demonstrated superior prognostic performance compared to single-omics approaches, highlighting the clinical value of integrated molecular profiling for precision oncology applications.

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanisms of NSCLC recurrence identified through multi-omics profiling. This diagram illustrates the coordinated molecular events across biological layers that drive disease recurrence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Profiling

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncomine Cancer Panel | Targeted NGS panel | Detects 4066 predefined variants across 143 genes | Optimized for FFPE samples; validated in CLIA labs |

| Ion Torrent PGM | Next-generation sequencer | Medium-throughput sequencing | Used in NCI-MATCH with locked analysis pipeline |

| Thermo Fisher AmpliSeq | Library preparation | RNA and DNA library construction | Integrated with Oncomine panel |

| 10X Genomics Chromium | Single-cell partitioning | High-throughput single-cell sequencing | Utilizes gel bead-in-emulsion technology |

| Pacific Biosciences SMRT | Long-read sequencing | Epigenetic modification detection | Identifies base modifications without bisulfite treatment |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-read sequencing | Direct DNA/RNA sequencing | Enables simultaneous sequence and modification detection |

| PyClone-VI | Clonal decomposition | Phylogenetic analysis | Infers clonal architecture from multi-omics data |

| MOFA+ | Multi-omics factor analysis | Dimensionality reduction | Identifies shared and unique sources of variation |

Integrated multi-omic profiling combining WES, RNA-seq, and epigenetic data represents a powerful approach for elucidating complex biological mechanisms and validating NGS-derived chemogenomic signatures. The rigorous benchmarking of integration methods and comprehensive quality control frameworks established in recent studies provide robust analytical foundations for extracting biologically and clinically meaningful insights from these complex datasets. As the field advances, emerging technologies including long-read sequencing, single-cell multi-omics, and spatial transcriptomics are further enhancing the resolution and comprehensiveness of integrated molecular profiling [35].