A Comprehensive Guide to Planning a Successful Chemogenomics NGS Experiment in 2025

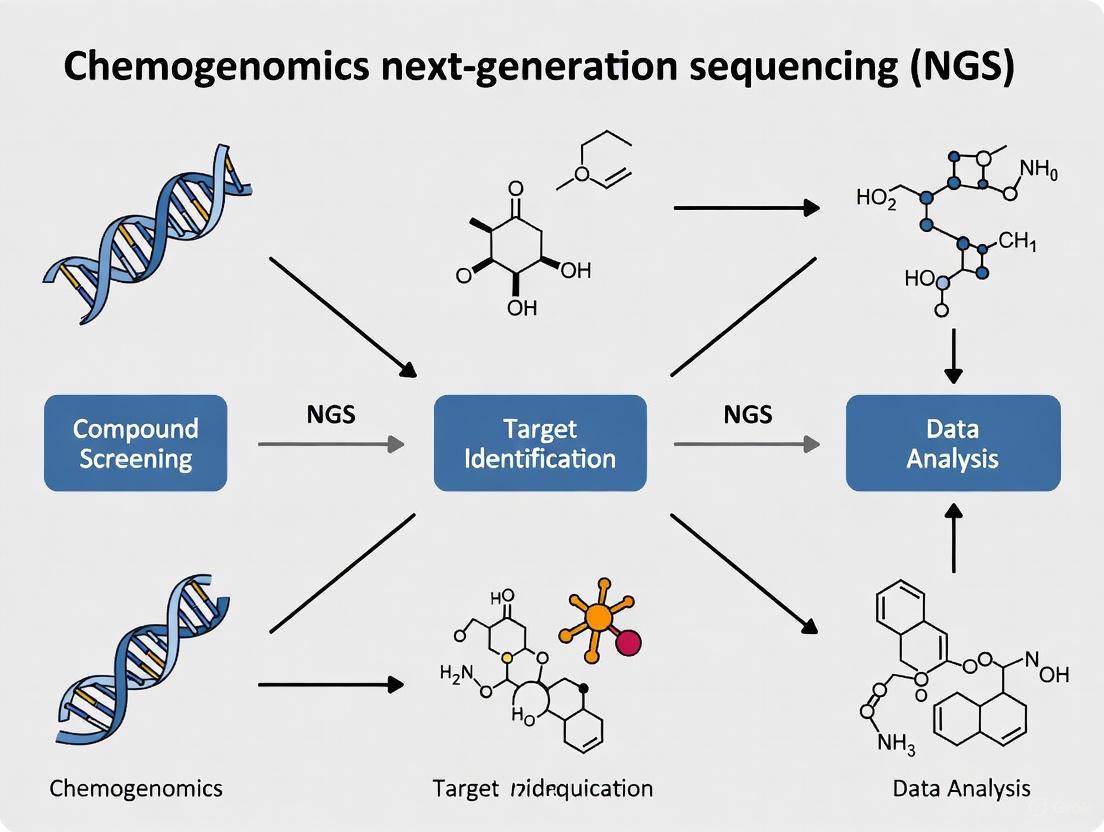

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for planning and executing a robust chemogenomics Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) experiment.

A Comprehensive Guide to Planning a Successful Chemogenomics NGS Experiment in 2025

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for planning and executing a robust chemogenomics Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) experiment. Covering the journey from foundational principles to advanced validation, it explores the integration of chemical and genomic data to uncover drug-target interactions. The article delivers actionable insights into experimental design, tackles common troubleshooting scenarios, and outlines rigorous methods for data analysis and cross-study comparison, ultimately empowering the development of targeted therapies and the advancement of precision medicine.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Chemogenomics and NGS

Chemogenomics is a foundational discipline in modern drug discovery that operates at the intersection of chemical biology and functional genomics. This field employs systematic approaches to investigate the interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems on a genome-wide scale, with the ultimate goal of defining relationships between chemical structures and their effects on genomic function. The core premise of chemogenomics lies in its ability to bridge two vast domains: chemical space—the theoretical space representing all possible organic compounds—and genomic function—the complete set of functional elements within a genome.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized chemogenomics by providing the technological means to comprehensively assess how small molecules modulate biological systems. Unlike traditional methods that examined compound effects on single targets, NGS-enabled chemogenomics allows for the unbiased, genome-wide monitoring of transcriptional responses, mutational consequences, and epigenetic modifications induced by chemical perturbations [1] [2]. This paradigm shift has transformed drug discovery from a target-centric approach to a systems-level investigation, enabling researchers to deconvolve complex mechanisms of action, identify novel therapeutic targets, and predict off-target effects with unprecedented resolution.

The integration of NGS technologies has positioned chemogenomics as an essential framework for addressing fundamental challenges in pharmaceutical research, including polypharmacology, drug resistance, and patient stratification. By quantitatively linking chemical properties to genomic responses, chemogenomics provides the conceptual and methodological foundation for precision medicine approaches that tailor therapeutic interventions to individual genetic profiles [3].

Foundational NGS Technologies for Chemogenomics

Core Sequencing Principles and Platform Selection

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies operate on the principle of massive parallel sequencing, enabling the simultaneous analysis of millions to billions of DNA fragments in a single experiment [1]. This represents a fundamental shift from traditional Sanger sequencing, which processes only one DNA fragment per reaction. The key technological advancement lies in this parallelism, which has led to a dramatic reduction in both cost (approximately 96% decrease per genome) and time required for comprehensive genomic analysis [1].

The NGS workflow comprises three principal stages: (1) library preparation, where DNA or RNA is fragmented and platform-specific adapters are ligated; (2) sequencing, where millions of cluster-amplified fragments are sequenced simultaneously using sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry; and (3) data analysis, where raw signals are converted to sequence reads and interpreted through sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines [1]. For chemogenomics applications, the choice of NGS platform and methodology depends on the specific experimental questions being addressed.

Table 1: NGS Method Selection for Chemogenomics Applications

| Research Question | Recommended NGS Method | Key Information Gained | Typical Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action Studies | RNA-Seq | Genome-wide transcriptional changes, pathway modulation | 20-50 million reads/sample |

| Resistance Mutations | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Comprehensive variant identification across coding/non-coding regions | 30-50x |

| Epigenetic Modifications | ChIP-Seq | Transcription factor binding, histone modifications | Varies by target |

| Off-Target Effects | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Coding region variants across entire exome | 100x |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Transcriptional profiles at single-cell resolution | 50,000 reads/cell |

Essential Bioinformatics Tools

The interpretation of NGS data in chemogenomics relies on a sophisticated bioinformatics ecosystem comprising both open-source and commercial solutions. These tools transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights about compound-genome interactions.

Open-source platforms provide transparent, modifiable pipelines for specialized analyses. The DRAGEN-GATK pipeline offers best practices for germline and somatic variant discovery, crucial for identifying mutation patterns induced by chemical treatments [4]. Tools like Strelka2 enable accurate detection of single nucleotide variants and small indels in compound-treated versus control samples [4]. For analyzing repetitive elements often involved in drug response, ExpansionHunter provides specialized genotyping of repeat expansions, while SpliceAI utilizes deep learning to identify compound-induced alternative splicing events [4].

Commercial solutions such as Geneious Prime offer integrated environments that streamline NGS data analysis through user-friendly interfaces, while QIAGEN Digital Insights provides curated knowledge bases linking genetic variants to functional consequences [5] [6]. These platforms are particularly valuable in regulated environments where reproducibility and standardized workflows are essential.

For quantitative morphological phenotyping often correlated with genomic data in chemogenomics, R and Python packages enable sophisticated image analysis and data integration, facilitating the connection between compound-induced phenotypic changes and their genomic correlates [7].

Experimental Design and Workflows

Strategic Framework for Chemogenomics Studies

A well-designed chemogenomics experiment requires careful consideration of multiple factors to ensure biologically relevant and statistically robust results. The experimental framework begins with precise definition of the chemical and biological systems under investigation, including compound properties (concentration, solubility, stability), model systems (cell lines, organoids, in vivo models), and treatment conditions (duration, replicates) [3].

Central to this framework is the selection of appropriate controls, which typically include untreated controls, vehicle controls (to account for solvent effects), and reference compounds with known mechanisms of action. These controls are essential for distinguishing compound-specific effects from background biological variation. Experimental replication should be planned with statistical power in mind, with most chemogenomics studies requiring at least three biological replicates per condition to ensure reproducibility [8].

The timing of sample collection represents another critical consideration, as it should capture both primary responses (direct compound-target interactions) and secondary responses (downstream adaptive changes). For time-course experiments, sample collection at multiple time points (e.g., 2h, 8h, 24h) enables differentiation of immediate from delayed transcriptional responses [9].

Quality Control and Validation

Implementing rigorous quality control measures throughout the experimental workflow is essential for generating reliable chemogenomics data. The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI) provides comprehensive frameworks for establishing quality management systems in NGS workflows [8]. Key recommendations include the use of the hg38 genome build as reference, implementation of standardized file formats, strict version control for analytical pipelines, and verification of data integrity through file hashing [3].

For library preparation, quality assessment should include evaluation of nucleic acid integrity (RIN > 8 for RNA studies), fragment size distribution, adapter contamination, and library concentration. During sequencing, key performance indicators include cluster density, Q-score distributions (aiming for Q30 ≥ 80%), and base call quality across sequencing cycles [1] [8].

Bioinformatics quality control encompasses verification of sequencing depth and coverage uniformity, assessment of alignment metrics, and evaluation of sample identity through genetically inferred markers. Pipeline validation should utilize standard truth sets such as Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) for germline variant calling and SEQC2 for somatic variant calling, supplemented with in-house datasets for filtering recurrent artifacts [3].

Data Analysis Pipelines and Computational Methods

Bioinformatics Framework for Chemogenomics

The analysis of NGS data in chemogenomics follows a structured pipeline that transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights about compound-genome interactions. This multi-stage process requires specialized tools and computational approaches at each step to ensure accurate interpretation of results.

Primary analysis begins with converting raw sequencing signals (BCL files) to sequence reads (FASTQ format) with corresponding quality scores (Phred scores) [1]. This demultiplexing and base calling step includes initial quality assessment using tools like FastQC to identify potential issues with sequence quality, adapter contamination, or GC bias [9].

Secondary analysis involves aligning sequence reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners such as BWA or STAR, generating BAM files that map reads to their genomic positions [3] [9]. Variant calling then identifies differences between the sample and reference genome, employing specialized tools for different variant types: GATK or Strelka2 for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels); Paragraph for structural variants; and ExpansionHunter for repeat expansions [4]. The output is a VCF file containing all identified genetic variants.

Tertiary analysis represents the most critical stage for chemogenomics interpretation, where variants are annotated with functional information from databases such as dbSNP, gnomAD, and ClinVar [1]. This annotation facilitates prioritization of variants based on population frequency, functional impact (e.g., missense, nonsense), and known disease associations. Subsequent pathway analysis connects compound-induced genetic changes to biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components, ultimately enabling mechanism of action prediction and target identification [3].

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Beyond standard variant analysis, chemogenomics leverages several specialized computational approaches to extract maximal biological insight from NGS data. Graph-based pipeline architectures provide flexible frameworks for integrating diverse analytical tools, automatically compiling specialized tool combinations based on specific analysis requirements [10]. This approach enhances both extensibility and maintainability of bioinformatics workflows, which is particularly valuable in the rapidly evolving chemogenomics landscape.

For cancer chemogenomics, additional analyses include assessment of microsatellite instability (MSI) to identify DNA mismatch repair defects, evaluation of tumor mutational burden (TMB) to predict immunotherapy response, and quantification of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) to guide PARP inhibitor therapy [3]. These specialized analyses require customized computational methods and interpretation frameworks.

Artificial intelligence approaches are increasingly being integrated into chemogenomics pipelines, with deep learning models like PrimateAI helping classify the pathogenicity of missense mutations identified in compound-treated samples [4] [2]. Large language models trained on biological sequences show promise for generating novel protein designs and predicting compound-protein interactions, potentially expanding the scope of chemogenomics from discovery to design [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of chemogenomics studies requires access to specialized reagents, computational resources, and experimental materials. The following table comprehensively details the essential components of a chemogenomics research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics

| Category | Specific Item/Kit | Function in Chemogenomics Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | High-quality DNA/RNA extraction kits | Isolation of intact genetic material from compound-treated cells/tissues |

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera, KAPA HyperPrep | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification for sequencing |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina TruSeq, IDT xGen | Hybrid-capture or amplicon-based targeting of specific genomic regions |

| Sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq, Ion Torrent S5 | High-throughput sequencing of prepared libraries |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer | Assessment of nucleic acid quality, fragment size, and concentration |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK, Strelka2, DESeq2 | Variant calling, differential expression analysis |

| Reference Databases | gnomAD, dbSNP, ClinVar, OMIM | Annotation and interpretation of identified genetic variants |

| Cell Culture Models | Immortalized cell lines, primary cells, organoids | Biological systems for compound treatment and genomic analysis |

| Compound Libraries | FDA-approved drugs, targeted inhibitor collections | Chemical perturbations for genomic functional studies |

Chemogenomics represents a powerful integrative framework that systematically connects chemical space to genomic function, with next-generation sequencing technologies serving as the primary enabling methodology. This approach has transformed early drug discovery by providing comprehensive, unbiased insights into compound mechanisms of action, off-target effects, and resistance patterns. The structured workflows, analytical pipelines, and specialized tools outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with a robust foundation for designing and implementing chemogenomics studies that can accelerate therapeutic development and advance precision medicine initiatives.

As NGS technologies continue to evolve, with improvements in long-read sequencing, single-cell applications, and real-time data acquisition, the resolution and scope of chemogenomics will expand correspondingly [9]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches will further enhance our ability to extract meaningful patterns from complex chemogenomics datasets, potentially enabling predictive modeling of compound efficacy and toxicity based on genomic features [2]. Through the continued refinement of these interdisciplinary approaches, chemogenomics will remain at the forefront of efforts to rationally connect chemical structures to biological function, ultimately enabling more effective and targeted therapeutic interventions.

The evolution of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed chemogenomics research, enabling the systematic screening of chemical compounds against genomic targets at an unprecedented scale. This technological progression from first-generation Sanger sequencing to today's massively parallel platforms has provided researchers with powerful tools to understand complex compound-genome interactions, accelerating drug discovery and therapeutic development. The ability to sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously has created new paradigms for target identification, mechanism of action studies, and toxicity profiling, making NGS an indispensable technology in modern pharmaceutical research. This technical guide examines the evolution of sequencing technologies, their current specifications, and their specific applications in chemogenomics research workflows, providing a framework for selecting appropriate platforms for drug discovery applications.

Historical Progression of Sequencing Technologies

The journey of DNA sequencing spans nearly five decades, marked by three distinct generations of technological innovation that have progressively increased throughput while dramatically reducing costs.

First-Generation Sequencing: The Sanger Era

The sequencing revolution began in 1977 with Frederick Sanger's chain-termination method, a breakthrough that first made reading DNA possible [11]. This approach, also known as dideoxy sequencing, utilizes modified nucleotides (dideoxynucleoside triphosphates or ddNTPs) that terminate DNA strand elongation when incorporated by DNA polymerase [12] [13]. The resulting DNA fragments of varying lengths are separated by capillary electrophoresis, with fluorescent detection identifying the terminal base at each position [13]. Sanger sequencing produces long, accurate reads (500-1000 bases) with exceptionally high per-base accuracy (Q50, or 99.999%) [13]. This method served as the cornerstone of genomics for nearly three decades and was used to complete the Human Genome Project in 2003, though this endeavor required 13 years and approximately $3 billion [11] [14]. Despite its accuracy, the fundamental limitation of Sanger sequencing is its linear, one-sequence-at-a-time approach, which restricts throughput and maintains high costs per base [13].

Second-Generation Sequencing: The NGS Revolution

The mid-2000s marked a paradigm shift with the introduction of massively parallel sequencing platforms, collectively termed Next-Generation Sequencing [11]. The first commercial NGS system, Roche/454, launched in 2005 and utilized pyrosequencing technology [12]. This was quickly followed by Illumina's Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) platform in 2006-2007 and Applied Biosystems' SOLiD system [11]. These second-generation technologies shared a common principle: parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments immobilized on surfaces or beads, delivering a massive increase in throughput while reducing costs from approximately $10,000 per megabase to mere cents [11]. This "massively parallel" approach transformed genetics into a high-speed, industrial operation, making large-scale genomic projects financially and practically feasible for the first time [14]. Illumina's SBS technology eventually came to dominate the market, at times holding approximately 80% market share due to its accuracy and throughput [11].

Third-Generation Sequencing: Long-Read Technologies

The 2010s witnessed the emergence of third-generation sequencing platforms that addressed a critical limitation of second-generation NGS: short read lengths [11]. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) pioneered this transition in 2011 with their Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, which observes individual DNA polymerase molecules in real time as they incorporate fluorescent nucleotides [11]. Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) introduced an alternative approach using protein nanopores that detect electrical signal changes as DNA strands pass through [11]. These technologies produce much longer reads (thousands to tens of thousands of bases), enabling resolution of complex genomic regions, structural variant detection, and full-length isoform sequencing [11]. While initial error rates were higher than short-read NGS, these have improved significantly through technological refinements - PacBio's HiFi reads now achieve >99.9% accuracy, while ONT's newer chemistries reach ~99% single-read accuracy [11].

Figure 1: Evolution of DNA Sequencing Technologies from Sanger to Modern Platforms

Comparative Analysis of Modern NGS Platforms

Key Platform Specifications and Performance Metrics

The contemporary NGS landscape features diverse platforms with distinct performance characteristics, enabling researchers to select instruments optimized for specific applications and scales.

Table 1: Comparative Specifications of Major NGS Platforms (2025)

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Throughput per Run | Accuracy | Key Applications in Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) | 50-300 bp (short) | Up to 16 Tb [11] | >99.9% [14] | Large-scale variant screening, transcriptomic profiling, population studies |

| Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) | 50-300 bp (short) | 10-360 Gb [15] | >99.9% [15] | Targeted gene panels, small whole-genome sequencing, RNA-seq |

| PacBio Revio | HiFi SMRT (long-read) | 10-25 kb [11] | 180-360 Gb [11] | >99.9% (HiFi) [11] | Structural variant detection, haplotype phasing, complex region analysis |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | Up to 4+ Mb (ultra-long) [16] | Up to 100s of Gb (PromethION) | ~99% (simplex) [11] | Real-time sequencing, direct RNA sequencing, epigenetic modification detection |

| Element Biosciences AVITI | avidity sequencing | 75-300 bp (short) | 10 Gb - 1.5 Tb | Q40+ [17] | Multiplexed screening, single-cell analysis, spatial applications |

| Ultima Genomics UG 100 | Sequencing-by-binding | 50-300 bp (short) | Up to 10-12B reads [17] | High | Large-scale population studies, high-throughput compound screening |

Technical Differentiation: Short-Read vs. Long-Read Technologies

The choice between short-read and long-read technologies represents a fundamental strategic decision in experimental design, with each approach offering distinct advantages for chemogenomics applications.

Short-Read Platforms (Illumina, Element, Ultima): Short-read sequencing excels at detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels with high accuracy and cost-effectiveness [14]. The massive throughput of modern short-read platforms makes them ideal for applications requiring deep sequencing, such as identifying rare mutations in heterogeneous cell populations after compound treatment or conducting genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic determinants of drug response [14]. The main limitation of short reads is their difficulty in resolving complex genomic regions, including repetitive elements, structural variants, and highly homologous gene families [14].

Long-Read Platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore): Long-read technologies overcome the limitations of short reads by spanning complex genomic regions in single contiguous sequences [11]. This capability is particularly valuable in chemogenomics for characterizing structural variants induced by genotoxic compounds, resolving complex rearrangements in cancer models, and phasing haplotypes to understand compound metabolism differences [11]. Recent accuracy improvements, particularly PacBio's HiFi reads and ONT's duplex sequencing, have made long-read technologies suitable for variant detection applications previously reserved for short-read platforms [11]. Additionally, Oxford Nanopore's direct RNA sequencing and real-time capabilities offer unique opportunities for studying transcriptional responses to compounds without reverse transcription or PCR amplification biases [11].

Table 2: NGS Platform Selection Guide for Chemogenomics Applications

| Research Application | Recommended Platform Type | Key Technical Considerations | Optimal Coverage/Depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Gene Panels | Short-read (Illumina NextSeq, Element AVITI) | High multiplexing capability, cost-effectiveness for focused studies | 500-1000x for rare variant detection |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Short-read (Illumina NovaSeq) for large cohorts; Long-read for complex regions | Balance between breadth and resolution of structural variants | 30-60x for human genomes |

| Transcriptomics (Bulk RNA-seq) | Short-read (Illumina NextSeq/NovaSeq) | Accurate quantification across dynamic range | 20-50 million reads/sample |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Short-read (Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000) | High sensitivity for low-input samples | 50,000-100,000 reads/cell |

| Epigenetics (Methylation) | Long-read (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) | Single-molecule resolution of epigenetic modifications | 30x for comprehensive profiling |

| Structural Variant Detection | Long-read (PacBio Revio, Oxford Nanopore) | Spanning complex rearrangements with long reads | 20-30x for variant discovery |

NGS Workflow and Experimental Design for Chemogenomics

Core NGS Workflow Components

The NGS workflow consists of three fundamental stages that convert biological samples into interpretable genetic data, each requiring careful optimization for chemogenomics applications.

Figure 2: Core NGS Experimental Workflow with Key Decision Points

Library Preparation: The initial stage involves converting input DNA or RNA into sequencing-ready libraries through fragmentation, size selection, and adapter ligation [18]. For chemogenomics applications, specific considerations include preserving strand specificity in RNA-seq to determine transcript directionality, implementing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to control for PCR duplicates in rare variant detection, and selecting appropriate fragmentation methods to avoid bias in chromatin accessibility studies [15].

Sequencing and Imaging: This stage involves the actual determination of nucleotide sequences using platform-specific biochemistry and detection methods [18]. For Illumina platforms, this utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators, while Pacific Biosciences employs real-time observation of polymerase activity, and Oxford Nanopore measures electrical signal changes as DNA passes through protein nanopores [11] [16]. Key parameters to optimize include read length, read configuration (single-end vs. paired-end), and sequencing depth appropriate for the specific chemogenomics application [15].

Data Analysis: The final stage transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights through computational pipelines [18]. This includes quality control, read alignment to reference genomes, variant identification, and functional annotation [19]. For chemogenomics, specialized analyses include differential expression testing for compound-treated vs. control samples, variant allele frequency calculations in resistance studies, and pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes affected by compound treatment [19].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NGS Workflows in Chemogenomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in NGS Workflow | Chemogenomics Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep, Nextera XT | Fragment DNA/RNA, add adapters, amplify libraries | Compatibility with low-input samples from limited cell numbers; preservation of strand information |

| Enzymes | DNA/RNA polymerases, ligases, transposases | Catalyze key biochemical reactions in library prep | High fidelity enzymes for accurate representation; tagmentase for chromatin accessibility mapping (ATAC-seq) |

| Barcodes/Adapters | Illumina TruSeq, IDT for Illumina, Dual Indexing | Unique sample identification for multiplexing | Sufficient complexity to avoid index hopping in large screens; unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for quantitative applications |

| Target Enrichment | IDT xGen Panels, Twist Human Core Exome | Capture specific genomic regions of interest | Custom panels for drug target genes; comprehensive coverage of pharmacogenomic variants |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit, qPCR | Quantify and qualify input DNA/RNA and final libraries | Sensitivity to detect degradation in clinical samples; accurate quantification for pooling libraries |

| Cleanup Beads | SPRIselect, AMPure XP | Size selection and purification | Tight size selection to remove adapter dimers; optimization for fragment retention |

Advanced Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

Transcriptomic Profiling for Mechanism of Action Studies

NGS-based RNA sequencing has become a cornerstone for elucidating mechanisms of action (MOA) for novel compounds in drug discovery [19]. Bulk RNA-seq can quantify transcriptome-wide expression changes in response to compound treatment, revealing affected pathways and biological processes [15]. Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) technologies extend this capability to resolve cellular heterogeneity in response to compounds, identifying rare resistant subpopulations or characterizing distinct cellular responses within complex tissues [19] [15]. Spatial transcriptomics further integrates morphological context with gene expression profiling, enabling researchers to map compound effects within tissue architecture - particularly valuable in oncology and toxicology studies [15].

Epigenetic Modifications in Compound Response

Epigenetic profiling using NGS provides critical insights into how compounds alter gene regulation without changing DNA sequence [15]. Key applications include ChIP-seq for mapping transcription factor binding and histone modifications, ATAC-seq for assessing chromatin accessibility, and bisulfite sequencing or enzymatic methylation detection for DNA methylation patterns [15]. In chemogenomics, these approaches can identify epigenetic mechanisms of drug resistance, characterize compounds that target epigenetic modifiers, and understand how chemical exposures induce persistent changes in gene regulation [16]. Long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore offer the unique advantage of detecting epigenetic modifications natively alongside sequence information [11].

Variant Detection for Pharmacogenomics and Resistance

Targeted sequencing panels focused on pharmacogenes enable comprehensive profiling of genetic variants that influence drug metabolism, efficacy, and adverse reactions [15]. These panels typically cover genes involved in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), as well as drug targets and immune genes relevant to therapeutic response [14]. In cancer research, deep sequencing of tumors pre- and post-treatment enables identification of resistance mechanisms and guidance of subsequent treatment strategies [15]. Liquid biopsy approaches using cell-free DNA sequencing provide a non-invasive method for monitoring treatment response and emerging resistance mutations [15] [14].

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The NGS landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends particularly relevant to chemogenomics research. The convergence of sequencing with artificial intelligence is creating new opportunities for predictive modeling of compound-genome interactions, with AI algorithms increasingly used for variant calling, expression quantification, and even predicting compound sensitivity based on genomic features [19]. Multi-omics integration represents another frontier, combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to build comprehensive models of compound action [19]. Spatial multi-omics approaches are extending this integration to tissue context, simultaneously mapping multiple molecular modalities within morphological structures [17]. Emerging sequencing technologies, such as Roche's SBX (Sequencing by Expansion) technology announced in 2025, promise further reductions in cost and improvements in data quality [17]. Additionally, the continued maturation of long-read sequencing is gradually eliminating the traditional trade-offs between read length and accuracy, enabling more comprehensive genomic characterization in chemogenomics studies [11].

For researchers planning chemogenomics experiments, the expanding NGS toolkit offers unprecedented capability to connect chemical compounds with genomic consequences. Strategic platform selection based on experimental goals, sample types, and analytical requirements will continue to be essential for maximizing insights while efficiently utilizing resources. As sequencing technologies advance further toward the "$100 genome" and beyond, NGS will become increasingly integral to the entire drug discovery and development pipeline, from target identification through clinical application.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, providing unparalleled capabilities for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [16]. For researchers in chemogenomics and drug development, selecting the appropriate sequencing platform is a critical strategic decision that directly impacts experimental design, data quality, and research outcomes. NGS technology has evolved into three principal categories—benchtop, production-scale, and specialized systems—each with distinct performance characteristics, applications, and operational considerations [18]. This technical guide provides a structured framework for evaluating these platform categories, with a specific focus on their application within chemogenomics research, where understanding compound-genome interactions is paramount.

The evolution from first-generation sequencing to today's diverse NGS landscape represents one of the most transformative advancements in modern biology [20]. While the Human Genome Project required over a decade and nearly $3 billion using Sanger sequencing, modern NGS platforms can sequence entire human genomes in a single day for a fraction of the cost [18]. This dramatic improvement in speed and cost-efficiency has made large-scale genomic studies accessible to individual research laboratories, opening new frontiers in personalized medicine, drug discovery, and functional genomics [21].

Understanding NGS Platform Categories

Category 1: Benchtop Sequencers

Benchtop sequencers are characterized by their compact footprint, operational simplicity, and flexibility, making them ideal for individual laboratories focused on small to medium-scale projects [22] [18]. These systems represent the workhorse instrumentation for targeted studies, method development, and validation workflows commonly encountered in chemogenomics research. Their relatively lower initial investment and rapid turnaround times enable research groups to maintain sequencing capabilities in-house without requiring dedicated core facility support.

Key Applications in Chemogenomics:

- Targeted gene sequencing for validating compound-induced genetic changes

- Small whole-genome sequencing (microbes, viruses) for antimicrobial discovery

- Transcriptome sequencing for profiling gene expression responses to compounds

- 16S metagenomic sequencing for studying compound effects on microbiomes

- miRNA and small RNA analysis for epigenetic and regulatory studies

Table 1: Comparative Specifications of Major Benchtop Sequencing Platforms

| Specification | iSeq 100 | MiSeq | NextSeq 1000/2000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Output | 1.2-1.6 Gb | 0.9-1.65 Gb | 120-540 Gb |

| Run Time | 9-19 hours | 4-55 hours | 11-48 hours |

| Max Reads | 4-25 million | 1-50 million | 400 million - 1.8 billion |

| Read Length | 1x36-2x150 bp | 1x36-2x300 bp | 2x150-2x300 bp |

| Key Chemogenomics Applications | Targeted sequencing, small RNA-seq | Amplicon sequencing, small genome sequencing | Single-cell profiling, exome sequencing, transcriptomics |

Category 2: Production-Scale Sequencers

Production-scale sequencers represent the high-throughput end of the NGS continuum, designed for large-scale genomic projects that generate terabytes of data per run [22] [18]. These systems are typically deployed in core facilities or dedicated sequencing centers supporting institutional or multi-investigator programs. For chemogenomics applications, these platforms enable comprehensive whole-genome sequencing of multiple cell lines, population-scale pharmacogenomic studies, and large-scale compound screening across diverse genetic backgrounds.

Key Applications in Chemogenomics:

- Large whole-genome sequencing (human, plant, animal) for population pharmacogenomics

- Exome and large panel sequencing for variant discovery in compound screening

- Single-cell profiling (scRNA-Seq, scDNA-Seq) for heterogeneous compound responses

- Metagenomic profiling for microbiome-therapeutic interaction studies

- Cell-free sequencing and liquid biopsy analysis for pharmacodynamic monitoring

Table 2: Comparative Specifications of Production-Scale Sequencing Platforms

| Specification | NovaSeq 6000 | NovaSeq X Plus | Ion GeneStudio S5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Output | 3-6 Tb | 8-16 Tb | 15-50 Gb |

| Run Time | 13-44 hours | 17-48 hours | 2.5-24 hours |

| Max Reads | 10-20 billion | 26-52 billion | 30-130 million |

| Read Length | 2x50-2x250 bp | 2x150 bp | 200-600 bp |

| Key Chemogenomics Applications | Population sequencing, multi-omics studies | Biobank sequencing, large cohort studies | Targeted resequencing, rapid screening |

Category 3: Specialized Sequencing Systems

Specialized sequencing systems address specific technical challenges that cannot be adequately resolved with conventional short-read platforms [18] [11]. These include long-read technologies that overcome limitations in complex region sequencing, structural variant detection, and haplotype phasing. For chemogenomics research, these platforms provide crucial insights into the structural genomic context of compound responses, epigenetic modifications, and direct RNA sequencing without reverse transcription artifacts.

Key Applications in Chemogenomics:

- De novo genome assembly for non-model organisms used in compound screening

- Full-length transcript sequencing for isoform-specific drug responses

- Epigenetic modification detection for compound-induced chromatin changes

- Complex structural variation analysis for pharmacogenetic traits

- Real-time sequencing for rapid diagnostic applications

Table 3: Comparative Specifications of Specialized Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio Revio | HiFi Circular Consensus Sequencing | 10-25 kb | >99.9% (Q30) | High accuracy long reads |

| Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Nanopore electrical sensing | 10-100+ kb | ~99% (Q20) with duplex | Ultra-long reads, real-time |

| PacBio Onso | Sequencing by binding | 100-200 bp | >99.9% (Q30) | High-accuracy short reads |

NGS Workflow and Experimental Methodology

The fundamental NGS workflow comprises three major stages: template preparation, sequencing and imaging, and data analysis [18]. Understanding these steps is essential for designing robust chemogenomics experiments and properly interpreting resulting data.

Template Preparation and Library Construction

Library preparation converts biological samples into sequencing-compatible formats through a series of molecular biology steps. The quality of this initial process profoundly impacts final data integrity.

Detailed Protocol: Standard DNA Library Preparation

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA using validated extraction methods. Quality control via fluorometry and fragment analysis is critical.

- Fragmentation: Shear DNA to appropriate fragment sizes (200-800 bp) using acoustic shearing, enzymatic fragmentation, or nebulization.

- End Repair and A-tailing: Convert fragmented DNA to blunt-ended fragments using polymerase and kinase activities, then add single A-overhangs.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific adapters containing sequencing priming sites and sample barcodes for multiplexing.

- Size Selection: Purify ligated fragments using magnetic bead-based cleanups or gel electrophoresis to optimize insert size distribution.

- Library Amplification: Enrich adapter-ligated fragments via limited-cycle PCR (typically 4-15 cycles) using high-fidelity polymerases.

- Final Quality Control: Quantify libraries via qPCR and assess size distribution using capillary electrophoresis.

Sequencing and Imaging

During sequencing, prepared libraries are loaded onto platforms where the actual base detection occurs through different biochemical principles [18] [16]:

- Sequencing by Synthesis (Illumina): Uses fluorescently-labeled reversible terminator nucleotides detected by imaging after each incorporation cycle [16].

- Semiconductor Sequencing (Ion Torrent): Detects hydrogen ions released during nucleotide incorporation via pH-sensitive semiconductors [18].

- Single Molecule Real-Time Sequencing (PacBio): Observes fluorescent nucleotide incorporation in real-time using zero-mode waveguides [11].

- Nanopore Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore): Measures electrical signal changes as DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores [11].

Data Analysis

The massive datasets generated by NGS require sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines for meaningful interpretation [18]:

- Base Calling: Convert raw signal data (images or electrical traces) into nucleotide sequences with associated quality scores.

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using tools like FastQC and perform adapter trimming and quality filtering.

- Alignment/Mapping: Map reads to reference genomes using aligners like BWA, Bowtie2, or minimap2 (for long reads).

- Variant Calling: Identify genetic variations using callers such as GATK, FreeBayes, or DeepVariant.

- Downstream Analysis: Perform application-specific analyses (differential expression, variant annotation, pathway enrichment).

Platform Selection Framework for Chemogenomics

Selecting the optimal NGS platform requires careful consideration of multiple technical and practical factors aligned with specific research objectives.

Application-Driven Selection Guide

Table 4: Platform Recommendations for Common Chemogenomics Applications

| Research Application | Recommended Platform Category | Optimal Read Length | Throughput Requirements | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Gene Panels | Benchtop | Short (75-150 bp) | Low-Moderate (1-50 Gb) | Cost-effectiveness, rapid turnaround |

| Whole Transcriptome | Benchtop/Production | Short (75-150 bp) | Moderate-High (10-100 Gb) | Detection of low-expression genes |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Production-Scale | Short (150-250 bp) | Very High (100 Gb-3 Tb) | Coverage uniformity, variant detection |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics | Benchtop/Production | Short (50-150 bp) | Moderate (10-100 Gb) | Cell throughput, molecular recovery |

| Metagenomic Profiling | Production/Specialized | Long reads (>10 kb) | High (50-500 Gb) | Species resolution, assembly quality |

| Structural Variant Detection | Specialized | Long reads (>10 kb) | Moderate-High (20-200 Gb) | Spanning complex regions |

| Epigenetic Profiling | Benchtop/Production | Short (50-150 bp) | Low-Moderate (5-50 Gb) | Antibody specificity, resolution |

Technical Considerations for Platform Selection

- Throughput Requirements: Estimate required sequencing depth based on application (e.g., 30x for WGS, 10-50 million reads per sample for RNA-seq).

- Read Length Considerations: Short reads (50-300 bp) suffice for most applications, while long reads (>10 kb) excel in resolving complex genomic regions.

- Error Profiles: Different technologies exhibit distinct error patterns (substitution vs. indel errors) that impact downstream analysis.

- Multiplexing Capabilities: Consider sample batching options to optimize run efficiency and cost management.

- Operational Factors: Include instrument footprint, personnel expertise, and computational infrastructure requirements.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics NGS

Successful implementation of NGS workflows in chemogenomics research requires careful selection of reagents and consumables optimized for specific platforms and applications.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics NGS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep, NEBNext Ultra II | Fragment end repair, adapter ligation, library amplification | Select based on input material, application, and platform compatibility |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina Nextera Flex, Twist Target Enrichment, IDT xGen | Selective capture of genomic regions of interest | Critical for focused panels; consider coverage uniformity |

| Amplification Reagents | KAPA HiFi HotStart, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Library amplification with minimal bias | High-fidelity enzymes essential for accurate variant detection |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer, Qubit assays | Assess nucleic acid quality, quantity, and fragment size | Critical for troubleshooting and optimizing success rates |

| Sample Barcoding | IDT for Illumina, TruSeq DNA/RNA UD Indexes | Sample multiplexing for cost-efficient sequencing | Enable sample pooling and demultiplexing in downstream analysis |

| Targeted RNA Sequencing | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Takara SMARTer | RNA enrichment, cDNA synthesis, library construction | Maintain strand information for transcript orientation |

| Single-Cell Solutions | 10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody | Single-cell partitioning, barcoding, and library prep | Enable cellular heterogeneity studies in compound responses |

| Long-Read Technologies | PacBio SMRTbell, Oxford Nanopore Ligation | Library prep for long-read sequencing | Optimized for large fragment retention and structural variant detection |

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The NGS landscape continues to evolve with significant implications for chemogenomics research. Several emerging trends are positioned to further transform the field:

Enhanced Long-Read Technologies: Recent advancements in accuracy for both PacBio (HiFi) and Oxford Nanopore (duplex sequencing) technologies are making long-read sequencing increasingly viable for routine applications [11]. For chemogenomics, this enables comprehensive characterization of complex genomic regions impacted by compound treatments.

Multi-Omic Integration: New platforms and chemistries are enabling simultaneous capture of multiple molecular features from the same sample. The PacBio SPRQ chemistry, for example, combines DNA sequence and chromatin accessibility information from individual molecules [11].

Ultra-High Throughput Systems: Production-scale systems like the NovaSeq X series can output up to 16 terabases of data in a single run, dramatically reducing per-genome sequencing costs and enabling unprecedented scale in chemogenomics studies [21].

Portable Sequencing: The miniaturization of sequencing technology through platforms like Oxford Nanopore's MinION brings sequencing capabilities directly to the point of need, enabling real-time applications in field-deployable chemogenomics studies [11].

The global NGS market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17.5% from 2025-2033, reaching $16.57 billion by 2033, reflecting the continued expansion and adoption of these technologies across research and clinical applications [21].

The strategic selection of NGS platform categories—benchtop, production-scale, and specialized systems—represents a critical decision point in designing effective chemogenomics research studies. Each category offers distinct advantages that align with specific research objectives, scale requirements, and technical considerations. Benchtop systems provide accessibility and flexibility for targeted studies, production-scale instruments deliver unprecedented throughput for population-level investigations, and specialized platforms overcome specific technical challenges associated with genomic complexity.

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput, longer reads, and integrated multi-omic capabilities, chemogenomics researchers are positioned to extract increasingly sophisticated insights from their compound screening and mechanistic studies. By aligning platform capabilities with specific research questions through the framework presented in this guide, scientists can optimize their experimental approaches to advance drug discovery and development through genomic science.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a high-throughput technology that enables millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced in parallel, revolutionizing genomic research and precision medicine [14] [23]. For researchers in chemogenomics, understanding the NGS workflow is fundamental to designing experiments that can uncover the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core NGS steps, from nucleic acid extraction to data analysis, framed within the context of planning a robust chemogenomics experiment.

The Core NGS Workflow

The standard NGS workflow consists of four consecutive steps that transform a biological sample into interpretable genetic data. The following diagram illustrates this fundamental process and the key actions at each stage.

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction

The NGS workflow begins with the isolation of genetic material. The required quantity and quality of the extracted nucleic acids are critical for success and depend on the specific NGS application [24] [18]. For chemogenomics studies, this could involve extracting DNA from cell lines or model organisms treated with chemical compounds to study genotoxic effects, or extracting RNA to profile gene expression changes in response to drug treatments.

After extraction, a quality control (QC) step is essential. UV spectrophotometry can assess purity, while fluorometric methods provide accurate nucleic acid quantitation [24]. High-quality input material is paramount, as any degradation or contamination can introduce biases that compromise downstream results.

Step 2: Library Preparation

Library preparation is the process of converting the extracted genomic DNA or cDNA sample into a format compatible with the sequencing instrument [24]. This complex process involves fragmenting the DNA, repairing the fragment ends, and ligating specialized adapter sequences [25] [18]. These adapters are critical as they enable the fragments to bind to the sequencer's flow cell and provide primer binding sites for amplification and sequencing [18].

For experiments involving multiple samples, unique molecular barcodes (indexes) are incorporated into the adapters, allowing samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a process known as multiplexing [23] [18]. This is particularly cost-effective for chemogenomics screens that test hundreds of chemical compounds. A key consideration is avoiding excessive PCR amplification during library prep, as this can reduce library complexity and introduce duplicate sequences that must be later removed bioinformatically [26] [25].

Step 3: Sequencing

During the sequencing step, the prepared library is loaded onto a sequencing platform, and the nucleotides of each fragment are read. The most common chemistry, used by Illumina platforms, is Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) [24] [18]. This process involves the repeated addition of fluorescently labeled, reversible-terminator nucleotides. As each nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, a camera captures its specific fluorescent signal, and the terminator is cleaved to allow the next cycle to begin [24] [18]. This cycle generates millions to billions of short reads simultaneously.

Two critical parameters to define for any experiment are read length (the length of each DNA fragment read by the sequencer) and depth or coverage (the average number of reads that align to a specific genomic base) [24]. The required coverage varies significantly by application, as detailed in the table below.

Step 4: Data Analysis and Interpretation

The raw data generated by the sequencer consists of short sequence reads and their corresponding quality scores [23]. Making sense of this data requires a multi-step bioinformatics pipeline, often starting with FASTQ files that store the sequence and its quality information for each read [26] [27].

A standard bioinformatics pipeline involves the following key steps, visualized in the diagram below:

- Quality Control and Adapter Trimming: Raw sequences are processed to remove low-quality bases and trim any remaining adapter sequences [26] [18].

- Alignment/Mapping: The cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome to determine their genomic origin [26] [27].

- Post-Alignment Processing: This includes the removal of PCR duplicates to prevent false positive variant calls and base quality score recalibration to improve the accuracy of the base calls [26].

- Variant Calling: Specialized algorithms compare the aligned sequences to the reference genome to identify variations, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), and larger structural variants [26] [27].

- Annotation and Interpretation: Identified variants are annotated with information from genomic databases, providing insights into their potential functional impact, population frequency, and clinical significance [26] [27]. For chemogenomics, this is where the link between a chemical treatment and specific genetic mutations or expression changes can be established.

Quantitative Considerations for Experimental Design

A well-designed NGS experiment requires careful planning of key parameters. The table below summarizes recommended sequencing coverages for common NGS applications relevant to chemogenomics research.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Coverage/Reads by NGS Application

| NGS Type | Application | Recommended Coverage (x) or Reads | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Heterozygous SNVs [28] | 33x | Ensures high probability of detecting alleles present in half the cells. |

| Insertion/Deletion Mutations (INDELs) [28] | 60x | Higher depth needed to confidently align and call small insertions/deletions. | |

| Copy Number Variation (CNV) [28] | 1-8x | Lower depth can be sufficient for detecting large-scale copy number changes. | |

| Whole Exome Sequencing | Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) [28] | 100x | Compensates for uneven capture efficiency across exons while remaining cost-effective vs. WGS. |

| RNA Sequencing | Differential expression profiling [28] | 10-25 million reads | Provides sufficient data for robust statistical comparison of transcript levels between samples. |

| Alternative splicing, Allele specific expression [28] | 50-100 million reads | Higher read depth is required to resolve and quantify different transcript isoforms. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the NGS workflow depends on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for the NGS Workflow

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from various sample types (e.g., tissue, cells, biofluids) [24]. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Contain enzymes and buffers for DNA fragmentation, end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation [25] [28]. |

| Platform-Specific Flow Cells | The glass surface where library fragments bind and are amplified into clusters prior to sequencing [18]. |

| Sequencing Reagent Kits | Provide the nucleotides, enzymes, and buffers required for the sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry [24] [18]. |

| Multiplexing Barcodes/Adapters | Unique DNA sequences ligated to samples to allow pooling and subsequent computational deconvolution [18]. |

A thorough understanding of the NGS workflow—from nucleic acid extraction to data analysis—is a prerequisite for designing and executing a successful chemogenomics research project. Each step, governed by specific biochemical and computational principles, contributes to the quality and reliability of the final data. By carefully considering experimental goals, required coverage, and the appropriate bioinformatics pipeline, researchers can leverage the power of NGS to unravel the complex mechanisms of chemical-genetic interactions and accelerate drug discovery.

Chemogenomics represents a powerful, systematic approach in modern drug discovery that investigates the interaction between chemical compounds and biological systems on a genomic scale. The integration of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has fundamentally transformed this field, enabling researchers to decode complex molecular relationships at unprecedented speed and resolution. NGS provides high-throughput, cost-effective sequencing solutions that generate massive datasets characterizing the nucleotide-level information of DNA and RNA molecules, forming the essential data backbone for chemogenomic analyses [29]. This technical guide examines three critical applications—drug repositioning, target deconvolution, and mechanism of action (MoA) studies—within the framework of chemogenomics NGS experimental research, providing methodological details and practical protocols for implementation.

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) with NGS technologies has further accelerated drug discovery paradigms. AI-driven platforms can now compress traditional discovery timelines dramatically; for instance, some AI-designed drug candidates have reached Phase I trials in approximately two years, compared to the typical five-year timeline for conventional approaches [30]. More than 90% of small molecule discovery pipelines at leading pharmaceutical companies are now AI-assisted, demonstrating the fundamental shift toward computational-augmented methodologies [31]. This whitepaper provides researchers with the technical frameworks and experimental protocols necessary to leverage these advanced technologies in chemogenomics research, with a specific focus on practical implementation within drug development workflows.

Drug Repositioning via Chemogenomics

Conceptual Framework and Strategic Value

Drug repositioning (also referred to as drug repurposing) is a methodological strategy for identifying new therapeutic applications for existing drugs or drug candidates beyond their original medical indication. This approach offers significant advantages over traditional de novo drug discovery, including reduced development timelines, lower costs, and minimized risk profiles since the safety and pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds are already established [32]. The integration of chemogenomics data, particularly through NGS methodologies, has dramatically enhanced systematic drug repositioning efforts by providing comprehensive molecular profiles of both drugs and disease states.

The fundamental premise of drug repositioning through chemogenomics rests on analyzing the relationships between chemical structures, genomic features, and biological outcomes. By examining how drug-induced genomic signatures correlate with disease-associated genomic patterns, researchers can identify potential new therapeutic indications computationally before embarking on costly clinical validation [32]. This approach maximizes the therapeutic value of existing compounds and can rapidly address pressing medical needs, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic when computational models successfully predicted gene expression changes induced by novel chemicals for rapid therapeutic repurposing [33].

Key Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Computational Approaches for Drug Repositioning

| Method Category | Key Technologies | Primary Data Sources | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico-Based Computational Approaches | Machine learning, deep learning, semantic inference | Chemical-genomic interaction databases, drug-target interaction maps | High efficiency, ability to screen thousands of compounds rapidly [32] |

| Activity-Based Experimental Approaches | High-throughput screening, phenotypic screening | Cell-based assays, transcriptomic profiles, proteomic data | Direct biological validation, captures complex system responses [32] |

| Target-Based Screening | Binding affinity prediction, molecular docking | Protein structures, binding site databases, structural genomics | Direct mechanism insight, rational design capabilities [32] |

| Knowledge-Graph Repurposing | Network analysis, graph machine learning | Biomedical literature, multi-omics data, clinical databases | Integrates diverse evidence types, discovers novel relationships [30] |

Experimental Protocol: NGS-Enhanced Drug Repositioning

Objective: Systematically identify novel therapeutic indications for approved drugs through transcriptomic signature matching.

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Treat relevant cell lines with compounds of interest at multiple concentrations (typically spanning 3-5 logs) and time points (e.g., 6h, 24h, 48h)

- Include appropriate vehicle controls and replicate samples (minimum n=3 biological replicates)

- Extract total RNA using standardized kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy) with DNase treatment

- Prepare RNA-seq libraries using poly-A selection or ribosomal RNA depletion protocols

- Sequence libraries on appropriate NGS platform (Illumina NextSeq 500 or similar) to minimum depth of 30 million paired-end reads per sample [29]

Step 2: Bioinformatics Processing

- Perform quality control on raw sequencing data using FastQC or similar tool

- Align reads to reference genome (GRCh38 recommended) using splice-aware aligners (STAR or HISAT2)

- Generate gene-level count matrices using featureCounts or HTSeq-count

- Conduct differential expression analysis using DESeq2 or edgeR packages in R [29]

Step 3: Signature Generation and Matching

- Calculate differentially expressed genes for each treatment condition versus controls

- Generate gene signature profiles using rank-based methods (e.g., Connectivity Map approach)

- Compare drug-induced signatures against disease-associated gene expression profiles from public repositories (e.g., GEO, TCGA)

- Apply statistical frameworks (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests) to identify signature reversals indicating therapeutic potential [32]

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Prioritize top candidate drug-disease pairs based on statistical significance and biological plausibility

- Validate predictions in disease-relevant cellular models and animal systems

- Proceed to clinical evaluation for most promising repositioning opportunities

Diagram 1: Drug Repositioning Workflow via Transcriptomic Profiling

Target Deconvolution Strategies

Principles and Significance

Target deconvolution refers to the systematic process of identifying the direct molecular targets and associated mechanisms through which bioactive small molecules exert their phenotypic effects. This methodology is particularly crucial in phenotypic drug discovery approaches, where compounds are initially identified based on their ability to induce desired cellular changes without prior knowledge of their specific molecular targets [34]. The integration of NGS technologies with chemoproteomic approaches has significantly enhanced target deconvolution capabilities, enabling researchers to more rapidly and accurately elucidate mechanisms underlying promising phenotypic hits.

The strategic importance of target deconvolution lies in its ability to bridge the critical gap between initial phenotypic screening and subsequent rational drug optimization. By identifying a compound's direct molecular targets and off-target interactions, researchers can make informed decisions about candidate prioritization, guide structure-activity relationship (SAR) campaigns to improve selectivity, predict potential toxicity liabilities, and identify biomarkers for clinical development [34]. Furthermore, comprehensive target deconvolution can reveal novel biology by identifying previously unknown protein functions or signaling pathways relevant to disease processes.

Experimental Approaches for Target Identification

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Target Deconvolution Methods

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-Down | Compound immobilization and target capture | Protein-level | Medium | Requires high-affinity probe, may miss transient interactions [34] |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) | Photoactivated covalent crosslinking to targets | Amino acid-level | Medium | Potential steric interference from photoprobes [34] |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) | Detection of enzymatic activity changes | Functional residue-level | High | Limited to enzyme families with defined probes [34] |

| Stability-Based Profiling (CETSA, TPP) | Thermal stability shifts upon binding | Protein-level | High | Challenging for low-abundance proteins [34] |

| Genomic Approaches (CRISPR) | Gene essentiality/modification screens | Gene-level | High | Indirect identification, functional validation required [33] |

Experimental Protocol: Integrated NGS-Chemoproteomics for Target Deconvolution

Objective: Identify molecular targets of a phenotypic screening hit using affinity purification coupled with multi-omics validation.

Step 1: Probe Design and Validation

- Design chemical probes by incorporating biotin or other affinity handles without disrupting bioactivity

- Validate probe functionality through phenotypic assays comparing original compound and probe

- Determine appropriate probe concentration ranges through dose-response experiments

- Prepare control probes with scrambled or inactive chemistry for specificity assessment [34]

Step 2: Target Capture and Preparation

- Incubate functionalized probes with cell lysates or living cells (typically 1-10 μM concentration)

- For photoaffinity labeling approaches: irradiate samples with UV light (typically 300-365 nm) to induce crosslinking

- Capture probe-bound complexes using streptavidin beads or appropriate affinity matrix

- Perform rigorous wash steps to remove non-specific binders (typically high-salt and detergent washes)

- On-bead digest captured proteins using trypsin or Lys-C for mass spectrometry analysis [34]

Step 3: Multi-Omics Target Identification

- Analyze captured proteins by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Process proteomics data using standard search engines (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer)

- In parallel, conduct CRISPR-based genetic screens to identify genes whose manipulation modifies compound sensitivity

- Integrate proteomic and genetic datasets to generate high-confidence target candidates [33]

Step 4: Functional Validation

- Apply orthogonal binding assays (SPR, ITC) to confirm direct compound-target interactions

- Use cellular assays (knockdown, knockout, or dominant-negative approaches) to validate functional relevance

- Employ structural biology approaches (crystallography, Cryo-EM) where feasible to characterize binding mode

Diagram 2: Integrated Target Deconvolution Workflow

Mechanism of Action (MoA) Studies

Comprehensive MoA Elucidation Frameworks

Mechanism of Action (MoA) studies aim to comprehensively characterize the full sequence of biological events through which a therapeutic compound produces its pharmacological effects, from initial target engagement through downstream pathway modulation and ultimate phenotypic outcome. While target deconvolution identifies the primary molecular interactions, MoA studies encompass the broader functional consequences across multiple biological layers, including gene expression, protein signaling, metabolic reprogramming, and cellular phenotype alterations [33]. The integration of multi-omics NGS technologies has revolutionized MoA elucidation by enabling systematic, unbiased profiling of drug effects across these diverse molecular dimensions.

Modern MoA frameworks leverage advanced AI platforms to integrate heterogeneous data types and extract biologically meaningful patterns. For instance, sophisticated phenotypic screening platforms like PhenAID combine high-content imaging data with transcriptomic and proteomic profiling to identify characteristic morphological and molecular signatures associated with specific mechanisms of action [33]. These integrated approaches can distinguish between subtly different MoA classes even within the same target pathway, providing crucial insights for drug optimization and combination therapy design.

Multi-Omics Approaches for MoA Characterization

Table 3: NGS Technologies for MoA Elucidation

| Omics Layer | NGS Application | MoA Insights Provided | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Whole genome sequencing (WGS), targeted panels | Identification of genetic biomarkers of response/resistance | Minimum 30x coverage for WGS; tumor-normal pairs for somatic calling [29] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq | Pathway activation signatures, cell state transitions | 20-50 million reads per sample; strand-specific protocols recommended [29] |

| Epigenomics | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, methylation sequencing | Regulatory element usage, chromatin accessibility changes | Antibody quality critical for ChIP-seq; cell number requirements for ATAC-seq [33] |

| Functional Genomics | CRISPR screens, Perturb-seq | Gene essentiality, genetic interactions | Adeplicate library coverage (500x); appropriate controls for screen normalization [33] |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Modal MoA Elucidation

Objective: Comprehensively characterize the mechanism of action for a compound with known efficacy but unknown downstream consequences.

Step 1: Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

- Treat disease-relevant models (cell lines, organoids, or animal models) with compound across multiple concentrations and time points

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, tool compounds with known MoA)

- Process samples for parallel multi-omics analyses:

- RNA sequencing (bulk and single-cell)

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin (ATAC-seq)

- Proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiling (mass spectrometry)

- High-content imaging (Cell Painting or similar) [33]

Step 2: NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing

- For RNA-seq: Prepare libraries using poly-A selection with unique dual indexes for multiplexing

- For ATAC-seq: Follow optimized protocols for tagmentation and library amplification

- For CRISPR screens: Prepare sequencing libraries from genomic DNA with sufficient coverage

- Sequence libraries on appropriate platforms (Illumina NextSeq or NovaSeq) with recommended read depths [29]

Step 3: Bioinformatics Analysis and Integration

- Process each data type through standardized pipelines:

- RNA-seq: Alignment, quantification, differential expression, pathway analysis

- ATAC-seq: Peak calling, differential accessibility, motif analysis

- CRISPR screens: Read count normalization, gene ranking, hit identification

- Apply multi-omics integration algorithms (MOFA+, mixOmics) to identify coordinated changes

- Use AI-based platforms to compare molecular signatures with reference databases of known MoAs [33]

Step 4: Systems-Level MoA Modeling

- Construct network models integrating all significantly altered molecular entities

- Prioritize key pathways and nodes based on statistical significance and biological coherence

- Generate testable hypotheses about causal relationships in the MoA

- Design and execute functional experiments to validate predicted network relationships

Diagram 3: Multi-Omics MoA Elucidation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemogenomics Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Provider Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SureSelect Target Enrichment | Agilent Technologies | Hybridization-based capture of genomic regions of interest | Targeted sequencing for focused investigations [29] |

| PhenAID Platform | Ardigen | AI-powered analysis of high-content phenotypic screening data | MoA studies, phenotypic screening [33] |

| TargetScout Service | Momentum Bio | Affinity-based pull-down and target identification | Target deconvolution for phenotypic hits [34] |

| PhotoTargetScout | OmicScouts | Photoaffinity labeling for target identification | Target deconvolution, especially membrane proteins [34] |

| CysScout Platform | Momentum Bio | Proteome-wide profiling of reactive cysteine residues | Covalent ligand discovery, target deconvolution [34] |

| SideScout Service | Momentum Bio | Label-free target deconvolution via stability shifts | Native condition target identification [34] |

| eProtein Discovery System | Nuclera | Automated protein expression and purification | Target production for functional studies [35] |

| MO:BOT Platform | mo:re | Automated 3D cell culture and organoid handling | Biologically relevant assay systems [35] |

| MapDiff Framework | AstraZeneca/University of Sheffield | Inverse protein folding for biologic drug design | Protein-based therapeutic engineering [31] |

| Edge Set Attention | AstraZeneca/University of Cambridge | Graph-based molecular property prediction | Small molecule optimization [31] |

The integration of chemogenomics with NGS technologies has created a powerful paradigm for modern drug discovery, enabling systematic approaches to drug repositioning, target deconvolution, and mechanism of action studies. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with comprehensive frameworks for designing and implementing robust experiments in these critical application areas. As AI and automation continue to transform the pharmaceutical landscape—with over 75 AI-derived molecules reaching clinical stages by the end of 2024—the strategic importance of these chemogenomics applications will only intensify [30].

Looking forward, several emerging technologies promise to further enhance these approaches. The ongoing development of more sophisticated multi-omics integration platforms, combined with advanced AI architectures like graph neural networks and foundation models, will enable even more comprehensive and predictive compound characterization [31]. Additionally, the increasing availability of automated benchside technologies—from liquid handlers to automated protein expression systems—will help bridge the gap between computational predictions and experimental validation, creating more efficient closed-loop design-make-test-analyze cycles [35]. By adopting the structured protocols and methodologies presented in this whitepaper, research scientists can position themselves at the forefront of this rapidly evolving field, leveraging chemogenomics NGS approaches to accelerate the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

Designing Your Experiment: Methodologies and Practical Applications

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, offering multiple approaches for analyzing genetic material. For chemogenomics research—which explores the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems—selecting the appropriate NGS method is critical for generating meaningful data. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of three core NGS approaches: whole genome sequencing, targeted sequencing, and RNA sequencing. We examine the technical specifications, experimental considerations, and applications of each method within the context of chemogenomics research, enabling scientists and drug development professionals to make informed decisions for their experimental designs.

Chemogenomics employs systematic approaches to discover how small molecules affect biological systems through their interactions with macromolecular targets. NGS technologies provide powerful tools for understanding these interactions at the genetic and transcriptomic levels, facilitating drug target identification, mechanism of action studies, and toxicology assessments [36]. The fundamental advantage of NGS over traditional sequencing methods lies in its massive parallelism, enabling simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments [1] [16]. This high-throughput capability has led to a dramatic 96% decrease in cost-per-genome while exponentially increasing sequencing speed [1].

For chemogenomics research, NGS applications span from identifying novel drug targets to understanding off-target effects of compounds and stratifying patient populations for clinical trials [36]. The choice of NGS approach directly impacts the scope, resolution, and cost of experiments, making selection critical for generating biologically relevant and statistically powerful data.

Comparative Analysis of NGS Approaches

Technical Specifications and Applications

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the three primary NGS approaches relevant to chemogenomics research:

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Approaches for Chemogenomics Research

| Parameter | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Targeted Sequencing | RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Target | Complete genome including coding, non-coding, and regulatory regions [1] | Pre-defined set of genes or regions of interest [36] | Complete transcriptome or targeted RNA transcripts [36] [37] |