A Beginner's Guide to the NGS Workflow: From Sample to Insight in Chemogenomics

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows, tailored for researchers and professionals entering the field of chemogenomics and drug development.

A Beginner's Guide to the NGS Workflow: From Sample to Insight in Chemogenomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) workflows, tailored for researchers and professionals entering the field of chemogenomics and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of NGS technology, details each critical step in the methodological workflow from nucleic acid extraction to data analysis, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Furthermore, it addresses the essential practices for analytical validation and compares different NGS approaches, empowering beginners to implement robust, reliable sequencing strategies in their research.

Demystifying NGS: Core Principles for the Chemogenomics Researcher

What is NGS? Understanding Massively Parallel Sequencing

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), also known as massively parallel sequencing, is a high-throughput technology that enables the determination of the order of nucleotides in entire genomes or targeted regions of DNA or RNA by sequencing millions to billions of short fragments simultaneously [1] [2]. This represents a fundamental shift from the traditional Sanger sequencing method, which sequences a single DNA fragment at a time. NGS has revolutionized biological sciences, allowing labs to perform a wide variety of applications and study biological systems at an unprecedented level [1].

For researchers in chemogenomics—a field focused on the interaction of chemical compounds with biological systems to accelerate drug discovery—understanding NGS is crucial. It provides the powerful, scalable genomic data needed to elucidate mechanisms of action, identify novel drug targets, and understand cellular responses to chemical libraries.

Core Principle of Massively Parallel Sequencing

The defining feature of NGS is its massively parallel nature. Instead of analyzing a single DNA fragment, NGS platforms miniaturize and parallelize the sequencing process.

- Traditional Sanger Sequencing: This first-generation technology is based on the chain-termination method and uses capillary electrophoresis to separate DNA fragments. It is limited in throughput, expensive for large-scale projects, and was used to complete the Human Genome Project over a decade at a cost of nearly $3 billion [1] [3].

- Massively Parallel NGS: NGS technologies break the genome into millions of small fragments. Each fragment is sequenced at the same time in a massively parallel fashion, generating a vast number of short "reads." These reads are then computationally reassembled by aligning them to a reference genome or by piecing them together de novo [4] [2]. This approach allows an entire human genome to be sequenced within a single day, a task that took Sanger sequencing over a decade [2].

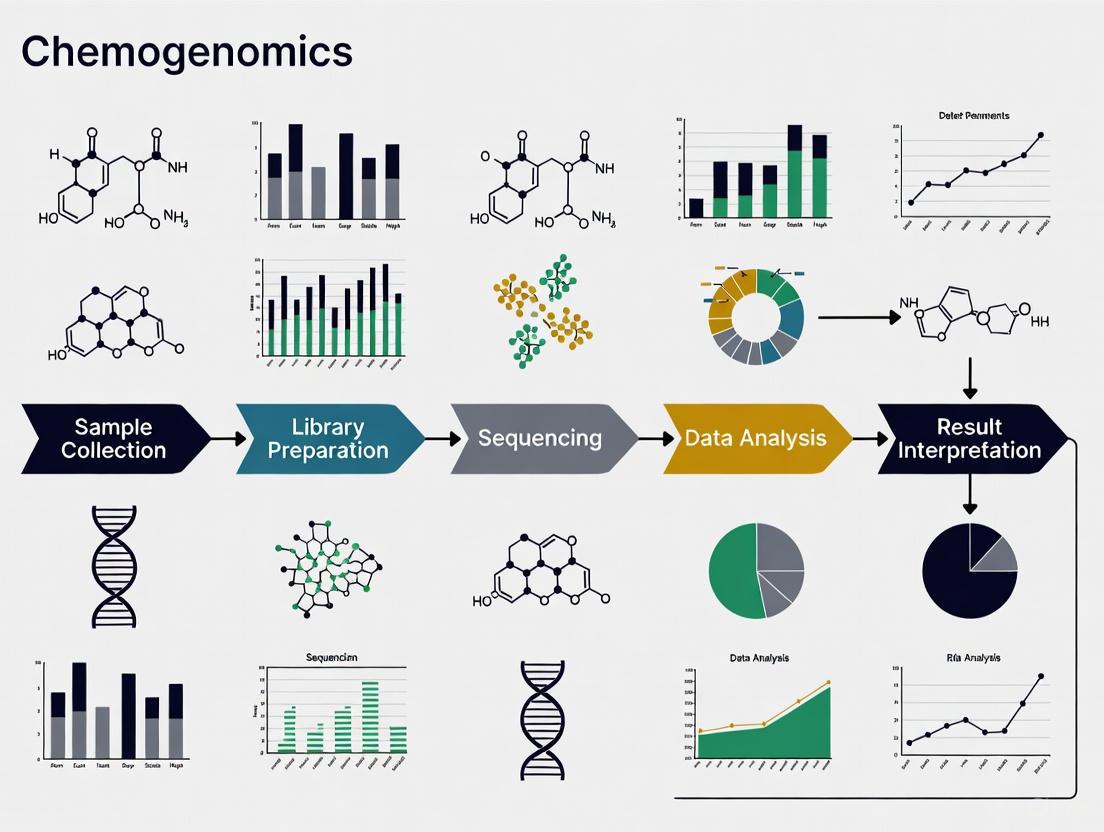

The NGS Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

A standard NGS workflow consists of four key steps. For chemogenomics research, where reproducibility and precision are paramount, each step must be meticulously optimized. The workflow is visually summarized in the diagram below.

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction

The process begins with the isolation of pure DNA or RNA from a sample of interest, such as cells treated with a chemical compound [5] [6]. This involves lysing cells and purifying the genetic material from other cellular components. The quality and quantity of the extracted nucleic acid are critical for all subsequent steps.

Step 2: Library Preparation

This is a crucial preparatory step where the purified DNA or RNA is converted into a format compatible with the sequencing instrument.

- Fragmentation: The genomic DNA or cDNA (complementary DNA synthesized from RNA) is randomly fragmented into smaller sizes [4] [6].

- Adapter Ligation: Specialized adapters are ligated (attached) to the ends of these fragments [5] [6]. These adapters serve multiple functions: they contain sequences that allow the fragments to bind to the flow cell (the surface where sequencing occurs), and they include index sequences (barcodes) that enable sample multiplexing—pooling multiple samples into a single sequencing run [6].

- Amplification (Optional): The adapter-ligated fragments, now called the "library," are often amplified using PCR to generate sufficient copies for detection [4]. However, excessive amplification can introduce bias and distort sequence heterogeneity, which is a critical consideration when studying the effects of small molecules on rare transcripts or variants [7].

Quantification of the final library is a sensitive and essential sub-step. Accurate quantification ensures optimal loading onto the sequencer. Methods include:

- Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit): Uses fluorescent dyes that bind specifically to nucleic acids [7].

- qPCR: Quantifies only library fragments that contain intact adapters and are capable of being sequenced, providing a more accurate measure of functional library concentration [7].

- Digital PCR (dPCR/ddPCR): Provides an absolute count of DNA molecules without the need for a standard curve, offering high sensitivity and accuracy, and is particularly useful for quantifying low-abundance libraries or avoiding amplification bias [7].

Step 3: Sequencing

The prepared library is loaded into a sequencer, where the actual determination of the base sequence occurs. The most common chemistry, used by Illumina platforms, is Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) [1] [4].

- Cluster Amplification: Library fragments are bound to a flow cell and amplified in situ through a process called "bridge amplification" to create tight, clonal clusters of each unique fragment [1] [4].

- Cyclic Reversible Termination (SBS): The flow cell is flooded with fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides. As DNA polymerase incorporates a complementary nucleotide into the growing DNA strand, a fluorescent signal is emitted. After imaging, the terminator and fluorophore are cleaved, and the cycle repeats hundreds of times to determine the sequence base-by-base [1]. Recent innovations like XLEAP-SBS chemistry have further increased the speed and fidelity of this process [1].

Step 4: Data Analysis

The massive number of short sequence reads generated (often tens to hundreds of gigabytes of data) must be processed computationally [1] [5].

- Primary Analysis: Involves base calling, which assigns a quality score (Q-score) to each base, indicating the probability of an incorrect call [7].

- Secondary Analysis: Reads are aligned to a reference genome (alignment), and genetic variants (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, deletions) are identified (variant calling) [2] [6].

- Tertiary Analysis: This is the interpretive stage, where the biological significance of the data is unlocked. For chemogenomics, this could involve pathway analysis, identifying differentially expressed genes in response to a compound, or correlating genetic mutations with drug sensitivity [1] [5].

NGS Chemistry and Platform Comparison

Different NGS platforms have been developed, each with unique engineering configurations and sequencing chemistries [4]. The table below summarizes the historical and technical context of major NGS platforms.

| Platform (Examples) | Sequencing Chemistry | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (HiSeq, MiSeq, NovaSeq) [4] [3] | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) with reversible dye-terminators [1] [4] | High throughput, high accuracy, short reads (50-300 bp). Dominates the market [4]. | WGS, WES, RNA-Seq, targeted sequencing [1] |

| Roche 454 [4] [3] | Pyrosequencing | Longer reads (400-700 bp), but higher cost and error rates in homopolymer regions [4] [3]. | Historically significant; technology discontinued [4] |

| Ion Torrent (PGM, Proton) [4] [3] | Semiconductor sequencing (detection of pH change) [4] | Fast run times, but struggled with homopolymer accuracy [4]. | Targeted sequencing, bacterial sequencing [3] |

| SOLiD [4] [3] | Sequencing by oligonucleotide ligation | High raw read accuracy, but complex data analysis and short reads [4] [3]. | Historically significant; technology discontinued [4] |

Table: Comparison of key NGS platforms and their chemistries. Illumina's SBS technology is currently the most widely adopted [4].

The core principle of Illumina's SBS chemistry, which dominates the current market, is illustrated in the following diagram.

Key NGS Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

The unbiased discovery power of NGS makes it an indispensable tool in the modern drug development pipeline.

- Target Identification and Validation: NGS can be used to discover novel disease-associated genes by sequencing patients with specific disorders (e.g., rare developmental disorders) or by identifying somatically acquired mutations in cancer genomes, thereby revealing new potential drug targets [2].

- Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq): This application quantifies gene expression across the entire transcriptome. For chemogenomics, RNA-Seq is used to profile the cellular response to chemical compounds, identify novel RNA variants and splice sites, and understand drug mechanisms of action. It offers a broader dynamic range for quantification compared to older technologies like microarrays [1] [5].

- Cancer Genomics and Personalized Medicine: Sequencing cancer samples allows researchers and clinicians to study rare somatic variants, tumor subclones, drug resistance, and metastasis. This enables more precise diagnosis, prognosis, and the identification of "druggable" mutations for targeted therapy [1] [2].

- Microbiome Research: NGS-based whole-genome shotgun sequencing and 16S rRNA sequencing are used to study the human microbiome. This can refine drug discovery by understanding how the microbiome influences drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity [1].

- Epigenetics: NGS can analyze epigenetic factors such as genome-wide DNA methylation (Bis-Seq) and DNA-protein interactions (ChIP-Seq). This helps in understanding how chemical compounds alter the epigenetic landscape, which can influence gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence [1] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful NGS experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key items for library preparation and sequencing.

| Item / Reagent | Function | Considerations for Chemogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA/RNA from diverse sample types (e.g., cell cultures, tissues). | Consistency in extraction is critical when comparing compound-treated vs. control samples. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/Systems | Randomly shear DNA into uniform fragments of desired size. | Shearing bias can affect coverage uniformity; method should be consistent across all samples in a screen. |

| Adapter Oligos & Ligation Kits | Attach platform-specific sequences to DNA fragments for binding and indexing. | Unique dual indexing is essential to prevent cross-talk when multiplexing many compound treatment samples. |

| PCR Enzymes for Library Amp | Amplify the adapter-ligated library to generate sufficient mass for sequencing. | Use high-fidelity polymerases and minimize PCR cycles to reduce duplicates and maintain representation of rare transcripts. |

| Quantification Kits (Qubit, qPCR, ddPCR) | Precisely measure library concentration. | Digital PCR (ddPCR) offers high accuracy for low-input samples, crucial for precious chemogenomics samples [7]. |

| Sequenceing Flow Cells & Chemistry (e.g., Illumina SBS kits) | The consumable surface where cluster generation and sequencing occur. | Choice of flow cell (e.g., high-output vs. mid-output) depends on the required scale and depth of the chemogenomic screen. |

Next-Generation Sequencing is more than just a sequencing technology; it is a foundational pillar of modern molecular biology and drug discovery. Its ability to provide massive amounts of genetic information quickly and cost-effectively has transformed how researchers approach biological questions. For the chemogenomics researcher, a deep understanding of the NGS workflow, chemistries, and applications is no longer optional but essential. Mastering this powerful tool enables the systematic deconvolution of compound mechanisms, accelerates target identification, and ultimately paves the way for the development of novel therapeutics.

For researchers entering the field of chemogenomics, understanding the fundamental tools of genomic analysis is paramount. The choice between Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing represents a critical early decision that can define the scale, scope, and success of a research program. While Sanger sequencing has served as the gold standard for accuracy for decades, NGS technologies have unleashed a revolution in speed, scale, and cost-efficiency, enabling research questions that were previously impossible to address [8] [9]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these technologies, specifically framed within the context of chemogenomics workflows for beginners, to empower researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal sequencing approach for their projects.

The evolution of DNA sequencing from the Sanger method to NGS mirrors the needs of modern biology. Chemogenomics—the study of the interaction of functional biomolecules with chemical libraries—increasingly relies on the ability to generate massive amounts of genomic data to understand compound mechanisms, identify novel drug targets, and elucidate resistance mechanisms. This guide will explore the technical foundations, comparative performance, and practical implementation of both sequencing paradigms to inform these crucial experimental decisions.

Fundamental Technical Differences

The core distinction between Sanger sequencing and NGS lies not in the basic biochemistry of DNA synthesis, but in the scale and parallelism of the sequencing process.

Sanger Sequencing: The Chain Termination Method

Sanger sequencing, also known as dideoxy or capillary electrophoresis sequencing, relies on the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) during in vitro DNA replication [10] [8]. In this method, DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand from a single-stranded template, but the inclusion of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs—which lack the 3'-hydroxyl group necessary for chain elongation—causes random termination at specific base positions [9]. The resulting DNA fragments are separated by capillary electrophoresis based on size, and the sequence is determined by detecting the fluorescent signal of the terminal ddNTP at each position [10]. This process generates a single, long contiguous read per reaction, typically ranging from 500 to 1000 base pairs, with exceptionally high accuracy (exceeding 99.99%) [10] [11].

Next-Generation Sequencing: Massively Parallel Sequencing

NGS, or massively parallel sequencing, represents a fundamentally different approach. While it also uses DNA polymerase to synthesize new strands, NGS simultaneously sequences millions to billions of DNA fragments in a single run [12] [5]. One prominent NGS method is Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), which utilizes fluorescently labeled, reversible terminators that are incorporated one base at a time across millions of clustered DNA fragments immobilized on a solid surface [10]. After each incorporation cycle, a high-resolution imaging system captures the fluorescent signal, the terminator is cleaved, and the process repeats [10]. Other NGS chemistries rely on principles such as ion detection or ligation, but all leverage massive parallelism to achieve unprecedented data output [10].

Diagram 1: Fundamental workflow differences between Sanger and NGS technologies.

Performance and Cost Comparison

The technological differences between Sanger sequencing and NGS translate directly into distinct performance characteristics and economic profiles, which must be carefully evaluated when designing chemogenomics experiments.

Throughput and Scalability

The throughput disparity between these technologies is the single most defining difference. Sanger sequencing processes one DNA fragment per reaction, making it suitable for targeted analysis of small genomic regions but impractical for large-scale projects [8]. In contrast, NGS can sequence millions to billions of fragments simultaneously per run, enabling comprehensive genomic analyses like whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) [10] [12]. This massive parallelism allows NGS to sequence hundreds to thousands of genes at once, providing unprecedented discovery power for identifying novel variants, structural variations, and rare mutations [12].

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

NGS offers superior sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants, a critical consideration in chemogenomics applications such as characterizing heterogeneous cell populations or identifying rare resistance mutations. While Sanger sequencing has a detection limit typically around 15-20% allele frequency, NGS can reliably identify variants present at frequencies as low as 1% through deep sequencing [12] [8]. This enhanced sensitivity makes NGS indispensable for applications like cancer genomics, where detecting somatic mutations in mixed cell populations is essential for understanding drug response and resistance mechanisms.

Sequencing Costs and Economic Considerations

The economic landscape of DNA sequencing has transformed dramatically, with NGS costs decreasing at a rate that far outpaces Moore's Law [13] [14]. While the initial capital investment for an NGS platform is substantial, the cost per base is dramatically lower than Sanger sequencing, making NGS significantly more cost-effective for large-scale projects [10] [15].

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance and Cost Comparison

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination with ddNTPs and capillary electrophoresis [10] [9] | Massively parallel sequencing (e.g., Sequencing by Synthesis) [10] [5] |

| Throughput | Low to medium (single fragment per reaction) [8] | Extremely high (millions to billions of fragments per run) [12] |

| Read Length | Long (500-1000 bp) [10] | Short to medium (50-300 bp for short-read platforms) [10] |

| Accuracy | Very high (~99.99%), considered the "gold standard" [11] [9] | High (<0.1% error rate), with accuracy improved by high coverage depth [10] [8] |

| Cost per Base | High [10] | Very low [10] |

| Detection Limit | ~15-20% allele frequency [12] [8] | ~1% allele frequency (with sufficient coverage) [12] [8] |

| Time per Run | Fast for single reactions (1-2 hours) [11] | Longer run times (hours to days) but massive parallelism [12] |

| Best For | Targeted confirmation, single-gene studies, validation [10] [12] | Whole genomes, exomes, transcriptomes, novel discovery [10] [12] |

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) has documented a 96% decrease in the average cost-per-genome since 2013 [13]. This trend has continued, with recent announcements of the sub-$100 genome from companies like Complete Genomics and Ultima Genomics [15] [14]. However, researchers should note that these figures typically represent only the sequencing reagent costs, and total project expenses must include library preparation, labor, data analysis, and storage [13] [15].

Table 2: Economic Considerations for Sequencing Technologies

| Economic Factor | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Instrument Cost | Lower [10] | Higher capital investment [10] |

| Cost per Run | Lower for small projects [12] | Higher per run, but massively more data [12] |

| Cost per Base/Mb | High [10] | Very low [10] |

| Cost per Genome | Prohibitively expensive for large genomes | $80-$200 (reagent cost only for WGS) [15] [14] |

| Data Analysis Costs | Low (minimal bioinformatics required) [10] | Significant (requires sophisticated bioinformatics) [10] |

| Total Cost of Ownership | Lower for small-scale applications | Must factor in ancillary equipment, computing resources, and specialized staff [13] |

Applications in Chemogenomics Research

The choice between Sanger and NGS technologies should be driven by the specific research question, scale, and objectives of the chemogenomics project.

Ideal Applications for Sanger Sequencing

Sanger sequencing remains the method of choice for applications requiring high accuracy for defined targets [8]. In chemogenomics, this includes:

- Validation of NGS findings: Confirming specific variants, mutations, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified through NGS screening [10] [12].

- Quality control of DNA constructs: Verifying plasmid sequences, inserts, and gene editing outcomes (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 modifications) [10] [11].

- Focused mutation screening: Interrogating known disease-associated loci or specific genetic variants in response to compound treatment [10].

- Low-throughput genotyping: Analyzing a small number of samples for a limited set of targets where NGS would be economically inefficient [12] [8].

Sanger sequencing is particularly well-suited for chemogenomics beginners starting with targeted, hypothesis-driven research, as it requires minimal bioinformatics expertise and offers a straightforward, reliable workflow [9].

Ideal Applications for Next-Generation Sequencing

NGS excels in discovery-oriented research that requires a comprehensive, unbiased view of the genome [12]. Key chemogenomics applications include:

- Whole-genome sequencing (WGS): Identifying novel genetic variants, structural variations, and copy number alterations across the entire genome in response to compound treatment [10].

- Whole-exome sequencing (WES): Focusing on protein-coding regions to identify causative mutations in functional genomic elements affected by chemical perturbations [10].

- Transcriptomics (RNA-Seq): Profiling gene expression changes, alternative splicing, and novel transcript isoforms induced by compound libraries [10] [12].

- Epigenetics: Mapping genome-wide DNA methylation patterns (methyl-seq) or protein-DNA interactions (ChIP-seq) to understand epigenetic mechanisms of drug action [10].

- High-throughput compound screening: Multiplexing hundreds to thousands of samples in a single run to profile genomic responses across diverse chemical libraries [12].

- Target deconvolution: Identifying novel drug targets and resistance mechanisms through comprehensive genomic analysis of compound-treated cell populations [16].

For chemogenomics researchers, NGS provides the hypothesis-generating power to uncover novel mechanisms and relationships that would remain invisible with targeted approaches.

Experimental Design and Workflow Considerations

Implementing sequencing technologies in a chemogenomics research program requires careful planning of experimental workflows and resource allocation.

NGS Workflow Steps for Beginners

A standard NGS workflow consists of four main steps [5]:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolation of high-quality DNA or RNA from biological samples, ensuring purity and integrity appropriate for downstream library preparation.

- Library Preparation: Fragmenting the DNA or RNA, followed by the addition of platform-specific adapters. This critical step may include target enrichment (e.g., using hybrid capture or amplicon approaches for focused studies) [16].

- Sequencing: Loading the prepared libraries onto the sequencing platform for massively parallel sequencing. The choice of instrument (e.g., benchtop vs. production-scale) depends on the required throughput and budget [13].

- Data Analysis: The most complex aspect of NGS, involving primary analysis (base calling), secondary analysis (alignment, variant calling), and tertiary analysis (biological interpretation) [10]. Beginners should leverage user-friendly bioinformatics platforms and collaborate with experienced bioinformaticians.

Diagram 2: Complete NGS workflow from sample to biological insight, highlighting key steps for beginners.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of sequencing technologies requires careful selection of reagents and materials at each workflow stage.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from various sample types | Select kits optimized for your source material (e.g., cells, tissue, blood) [5] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragmenting DNA/RNA and adding platform-specific adapters | Choice depends on sequencing application (WGS, WES, RNA-Seq) and sample input [5] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Enriching specific genomic regions of interest | Critical for targeted NGS; custom panels available for chemogenomics applications [12] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assessing nucleic acid quality, quantity, and library size distribution | Includes fluorometers, spectrophotometers, and fragment analyzers [13] |

| Sequencing Flow Cells/Chips | Platform-specific consumables where sequencing occurs | Choice affects total data output and cost-efficiency [13] |

| Sequenceing Chemistry Kits | Reagents for the sequencing reactions themselves | Platform-specific (e.g., Illumina SBS, Ion Torrent semiconductor) [16] |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data analysis, from base calling to variant calling and interpretation | Range from vendor-supplied to open-source tools; consider usability for beginners [10] [5] |

Total Cost of Ownership Considerations

When evaluating sequencing technologies, beginners must look beyond the initial instrument price or cost per gigabase. A comprehensive total cost of ownership assessment should include [13]:

- Ancillary equipment (e.g., nucleic acid quantitation instruments, quality analyzers, thermocyclers, centrifuges)

- Laboratory space and facility requirements

- Data storage and analysis infrastructure (computing resources, software licenses, IT support)

- Personnel costs for specialized staff (technical and bioinformatics expertise)

- Training and support services

- Reagent costs and supply chain stability

- Instrument service plans and maintenance

Illumina notes that economies of scale can significantly reduce costs for higher-output applications, but the initial investment in infrastructure and expertise should not be underestimated [13].

The revolution in DNA sequencing from Sanger to NGS technologies has fundamentally transformed the scale and scope of biological research, offering unprecedented capabilities for chemogenomics investigations. For beginners in the field, understanding the complementary strengths of these technologies is essential for designing efficient and informative research programs.

Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for targeted applications, offering unparalleled accuracy for validating variants, checking engineered constructs, and analyzing small numbers of genes [11] [9]. Its simplicity, reliability, and minimal bioinformatics requirements make it an excellent starting point for focused chemogenomics projects.

In contrast, NGS provides unmatched discovery power for comprehensive genomic analyses, enabling researchers to profile whole genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes in response to chemical perturbations [12] [8]. While requiring greater infrastructure investment and bioinformatics expertise, NGS offers tremendous cost-efficiencies for large-scale projects and can reveal novel biological insights that would remain hidden with targeted approaches.

For chemogenomics beginners, the optimal strategy often involves leveraging both technologies—using NGS for broad discovery and Sanger sequencing for targeted validation. As sequencing costs continue to decline and technologies evolve, the accessibility of these powerful tools will continue to expand, opening new frontiers in chemical biology and drug development research.

Key NGS Applications in Chemogenomics and Drug Discovery

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has become a cornerstone of modern chemogenomics and drug discovery, enabling researchers to understand the complex interactions between chemical compounds and biological systems at an unprecedented scale and resolution. By providing high-throughput genomic data, NGS accelerates target identification, biomarker discovery, and the development of personalized medicines, fundamentally reshaping pharmaceutical research and development [17] [18].

Core NGS Workflow in Drug Discovery

A typical NGS experiment follows a standardized workflow to convert a biological sample into interpretable genomic data. Understanding these steps is crucial for designing robust chemogenomics studies.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The process begins with extracting DNA or RNA from a biological sample. This genetic material is then fragmented into smaller pieces, and specialized adapters (short, known DNA sequences) are ligated to both ends. These adapters often contain unique molecular barcodes that allow multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a process called multiplexing [19] [20]. The prepared "library" is then loaded onto a sequencer. Most modern platforms use a form of sequencing by synthesis (SBS), where fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are incorporated one at a time into growing DNA strands, with a camera capturing the signal after each cycle [19].

Data Analysis

The massive amount of data generated by the sequencer undergoes a multi-stage analysis pipeline [21] [20]:

- Primary Analysis: The raw signal data from the instrument is converted into sequence reads with corresponding quality scores (Phred scores), resulting in FASTQ files.

- Secondary Analysis: Sequencing reads are cleaned (e.g., adapter trimming, quality filtering) and aligned to a reference genome. This step produces BAM files containing the aligned reads, which are then processed to identify genetic variants, generating VCF files, or to quantify gene expression [21].

- Tertiary Analysis: This stage involves the biological interpretation of the results, such as linking identified genetic variants to disease mechanisms or drug response [21].

Key NGS Applications and Methodologies in Chemogenomics

NGS technologies are applied across the drug discovery pipeline, from initial target identification to clinical trial optimization.

Drug Target Identification and Validation

NGS enables the discovery of novel drug targets by uncovering genetic variants linked to diseases through large-scale genomic studies [18].

- Methodology: Researchers conduct whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or whole-exome sequencing (WES) on cohorts of patients and healthy controls. By comparing the sequences, they can identify genes harboring significant mutations (e.g., loss-of-function mutations) associated with the disease. Studying individuals with naturally occurring loss-of-function mutations can help validate the safety and therapeutic potential of inhibiting a target [18].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Obtain tissue or blood samples from case and control cohorts.

- NGS Library Preparation: Prepare WGS or WES libraries using multiplexed barcodes.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an appropriate high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38).

- Call variants (SNVs, indels) and perform association analysis.

- Annotate variants and prioritize genes based on functional impact.

- Validation: Confirm key genetic findings using orthogonal methods like Sanger sequencing.

Pharmacogenomics and Toxicogenomics

This application focuses on understanding how genetic variations influence an individual's response to a drug, including efficacy and adverse effects [17] [18].

- Methodology: Targeted sequencing panels or WGS are used to profile genes involved in drug metabolism (e.g., CYP450 family), transport, and mechanism of action. In toxicogenomics, NGS is applied to study how chemicals cause toxicity by altering gene expression [17].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Study Design: Recruit patients showing differential response to a drug (e.g., responders vs. non-responders).

- Sequencing: Perform targeted sequencing of pharmacogenes or whole transcriptome profiling (RNA-Seq) from relevant tissues.

- Data Integration: Correlate genetic variants or gene expression changes with pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data and clinical outcomes.

- Biomarker Development: Identify genetic biomarkers that can predict drug response for clinical application.

Clinical Trial Stratification and Companion Diagnostics

NGS is used to stratify patients in clinical trials based on their genetic profiles, enriching for those most likely to respond to therapy [17] [18].

- Methodology: Using targeted sequencing of specific biomarkers (e.g., specific oncogenic mutations), patients are selected for trial enrollment. This approach increases trial success rates and facilitates the development of companion diagnostics [17].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Assay Development: Design an NGS-based assay targeting known predictive biomarkers for the disease and drug.

- Patient Screening: Sequence the biomarker panel for potential trial participants.

- Cohort Assignment: Assign patients to treatment arms based on their molecular profile.

- Real-Time Monitoring (Optional): Use newer platforms like Oxford Nanopore for real-time sequencing to monitor treatment response or resistance via circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [18].

DNA-Encoded Library Screening

This is a powerful chemogenomics application that accelerates the discovery of small molecules that bind to disease targets [18].

- Methodology: Vast libraries of small molecules, each tagged with a unique DNA barcode, are screened against a protein target of interest. The bound molecules are recovered, and the associated DNA barcodes are amplified and sequenced via NGS to identify the "hit" compounds.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Library Synthesis: Create a DNA-encoded chemical library (DEL).

- Affinity Selection: Incubate the DEL with the purified target protein.

- Wash and Elution: Remove unbound compounds and elute the specifically bound molecules.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the DNA barcodes from the eluted fraction.

- NGS and Deconvolution: Sequence the barcodes and map them back to the corresponding chemical structures for hit identification.

The table below summarizes the primary NGS technologies and their roles in drug discovery.

Table 1: NGS Technologies and Their Key Applications in Drug Discovery

| Technology | Primary Application in Drug Discovery | Key Advantage | Typical Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [17] | Comprehensive discovery of novel disease-associated variants and targets. | Unbiased, genome-wide view. | Very High (Gb – Tb) |

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) [17] [18] | Cost-effective discovery of coding variants linked to disease and drug response. | Focuses on protein-coding regions; more cost-effective than WGS. | Medium to High (Gb) |

| Targeted Sequencing / Gene Panels [17] | High-depth sequencing of specific genes for biomarker validation, pharmacogenomics, and companion diagnostics. | Cost-effective, allows for high sequencing depth on specific regions. | Low to Medium (Mb – Gb) |

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) [19] [18] | Profiling gene expression to understand drug mechanism of action, identify biomarkers, and study toxicogenomics. | Measures expression levels across the entire transcriptome. | Medium to High (Gb) |

| ChIP-Sequencing (ChIP-Seq) [17] [22] | Identifying binding sites of transcription factors or histone modifications to understand gene regulation by drugs. | Provides genome-wide map of protein-DNA interactions. | Medium to High (Gb) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NGS in chemogenomics relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS in Drug Discovery

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Kits [23] | Allows multiplexing of many samples by labeling each with unique barcodes on both ends of the fragment, minimizing index hopping. | Essential for any large-scale study pooling multiple patient or compound treatment samples. |

| NGS Library Prep Kits [19] | Kits tailored for specific applications (e.g., WGS, RNA-Seq, targeted panels) containing enzymes and buffers for fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and amplification. | The foundational starting point for preparing genetic material for sequencing. |

| Targeted Panels [17] | Pre-designed sets of probes to capture and enrich specific genes or genomic regions of interest (e.g., for pharmacogenetics or cancer biomarkers). | Used in companion diagnostic development and clinical trial stratification. |

| PhiX Control [24] | A well-characterized control library spiked into runs to monitor sequencing accuracy and, critically, to assist with color balance on Illumina platforms. | Vital for quality control, especially on modern two-channel sequencers (NextSeq, NovaSeq) to prevent data loss. |

| Cloud-Based Analysis Platforms [17] | Scalable computing resources to manage, store, and analyze the terabyte-scale datasets generated by NGS. | Crucial for tertiary analysis and integrating multi-omic datasets without local IT infrastructure. |

Data Visualization and Mining in Chemogenomics

Interpreting the vast datasets from NGS experiments requires specialized visualization tools that go beyond genome browsers. Programs like ngs.plot are designed to quickly mine and visualize enrichment patterns across functionally important genomic regions [22].

- Functionality: ngs.plot integrates NGS data (e.g., from ChIP-Seq or RNA-Seq) with genomic annotations (e.g., transcriptional start sites, enhancers) to generate average enrichment profiles and heatmaps. This allows researchers to see, for example, how a histone modification changes across a gene set after drug treatment [22].

- Workflow: The tool takes aligned reads (BAM files) and a set of genomic regions, calculates the coverage, normalizes it, and produces publication-ready figures showing aggregate patterns [22].

Quantitative Impact and Market Growth

The adoption of NGS in drug discovery is driven by clear quantitative benefits and significant market growth, reflecting its transformative impact.

Table 3: Market and Impact Metrics of NGS in Drug Discovery

| Metric | Value / Statistic | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024) [17] | USD 1.45 Billion | Demonstrates the substantial current investment and adoption of NGS technologies in the pharmaceutical industry. |

| Projected Market Size (2034) [17] | USD 4.27 Billion | Reflects the expected continued growth and integration of NGS into R&D pipelines. |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) [17] | 18.3% | Highlights the rapid pace of adoption and expansion of NGS applications in drug discovery. |

| Leading Application Segment [17] | Drug Target Identification (~37.2% revenue share) | Underscores the critical role of NGS in the foundational stage of discovering new therapeutic targets. |

| Leading Technology Segment [17] | Targeted Sequencing (~39.6% revenue share) | Indicates the prevalence of focused, cost-effective sequencing for biomarker and diagnostic development. |

| Cost Reduction [18] | From ~$100M (2001) to under $1,000 per genome | This drastic cost reduction has made large-scale genomic studies feasible, directly enabling precision medicine. |

The integration of NGS into chemogenomics represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, becoming faster, more accurate, and more affordable, their role in enabling the development of precise and effective personalized therapies will only become more central [19] [17] [18].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) represents a collection of high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies that enable the rapid parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments [5] [6]. For researchers in chemogenomics and drug development, understanding the core NGS approaches—targeted panels, whole exome sequencing (WES), and whole genome sequencing (WGS)—is fundamental to selecting the appropriate methodology for specific research questions. These technologies have revolutionized genetic research by dramatically reducing sequencing costs and analysis times while expanding the scale of genomic investigations [25] [5]. The selection between these approaches involves careful consideration of multiple factors including research objectives, target genomic regions, required coverage depth, and available resources [25].

Each methodological approach offers distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications in drug discovery and development. Targeted sequencing panels provide deep coverage of select gene sets, WES offers a cost-effective survey of protein-coding regions, and WGS delivers the most comprehensive genomic analysis by covering both coding and non-coding regions [25] [26]. This technical guide examines these three major NGS approaches within the context of chemogenomics research, providing detailed methodologies, comparative analyses, and practical implementation guidelines to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Technical Specifications of Major NGS Approaches

Targeted Sequencing Panels

Targeted sequencing panels utilize probes or primers to isolate and analyze specific subsets of genes associated with particular diseases or biological pathways [25] [27]. This approach focuses on predetermined genomic regions of interest, making it highly efficient for investigating well-characterized genetic conditions. Targeted panels deliver greater coverage depth per base of targeted genes, which facilitates easier interpretation of results and is particularly valuable for detecting low-frequency variants [25]. The method is considered the most economical and effective diagnostic approach when the genes associated with suspected diseases have already been identified [25].

A significant limitation of targeted panels is their restricted scope, which may miss molecular diagnoses outside the predetermined gene set. A 2021 study demonstrated that targeted panels missed diagnoses in 64% of rare disease cases compared to exome sequencing, with metabolic abnormality disorders showing the highest rate of missed diagnoses at 86% [27]. Additionally, targeted sequencing typically allows only for one-time analysis, making it impossible to re-analyze data for other genes if the initial results are negative [25]. This constraint is particularly problematic in research settings where new gene-disease associations are continuously being discovered, with approximately 250 gene-disease associations and over 9,000 variant-disease associations reported annually [25].

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)

Whole exome sequencing focuses specifically on the exon regions of the genome, which comprise approximately 2% of the entire genome but harbor an estimated 85% of known pathogenic variants [25]. WES represents a balanced approach between the narrow focus of targeted panels and the comprehensive scope of WGS, providing more extensive information than targeted sequencing while remaining more cost-effective than WGS [25]. This methodology is particularly valuable as a first-tier test for cases involving severe, nonspecific symptoms or conditions such as chromosomal imbalances, microdeletions, or microduplications [25].

The primary limitation of WES stems from its selective targeting of exonic regions. Not all exonic regions can be effectively evaluated due to variations in capture efficiency, and noncoding regions are not sequenced, making it impossible to detect functional variants outside exonic areas [25]. WES also demonstrates limited sensitivity for detecting structural variants (SVs), with the exception of certain copy number variations (CNVs) such as indels and duplications [25]. Additionally, data quality and specific genomic regions covered can vary depending on the capture kit utilized, as different kits employ distinct targeted regions and probe manufacturing methods [25]. On average, approximately 100,000 mutations can be identified in an individual's WES data, requiring sophisticated filtering and interpretation according to established guidelines such as those from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [25].

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Whole genome sequencing represents the most comprehensive NGS approach by analyzing the entire genome, including both coding and non-coding regions [25]. This extensive coverage provides WGS with the highest diagnostic rate among genetic testing methods and enables the detection of variation types that cannot be identified through WES, including structural variants and mitochondrial DNA variations [25]. By extending gene analysis coverage to non-coding regions, WGS can reduce unnecessary repetitive testing and provide a more complete genomic profile [25].

The comprehensive nature of WGS presents significant challenges in data management and interpretation. WGS generates extensive datasets, with costs for storing and analyzing this data typically two to three times higher than those for WES, despite constant technological advances steadily decreasing these expenses [25]. The interpretation of non-coding variants presents another substantial challenge, as there is insufficient research on non-coding regions compared to exonic regions, resulting in inadequate information for variant analysis [25]. This insufficient evidence regarding pathogenicity of non-coding variants can create confusion among researchers and clinical geneticists. On average, WGS detects around 3 million mutations per individual, making comprehensive assessment of each variant's pathogenicity nearly impossible without advanced computational approaches [25].

Comparative Analysis of NGS Approaches

Technical and Performance Specifications

Table 1: Comparative technical specifications of major NGS approaches

| Parameter | Targeted Panels | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | 10s - 100s of specific genes | ~2% of genome (exonic regions) | ~100% of genome (coding & non-coding) |

| Known Pathogenic Variant Coverage | Limited to panel content | ~85% of known pathogenic variants [25] | Nearly 100% |

| Average Diagnostic Yield | Varies by panel (avg. 36% sensitivity vs. ES for rare diseases) [27] | ~31.6% (rare diseases) [27] | Highest among methods [25] |

| Variant Types Detected | SNVs, small indels in targeted regions | SNVs, small indels, some CNVs [25] | SNVs, indels, CNVs, SVs, mitochondrial variants [25] |

| Typical Coverage Depth | High (>500x) | Moderate (100-200x) | Lower (30-60x) |

| Data Volume per Sample | Lowest (MB-GB range) | Moderate (GB range) | Highest (100+ GB range) |

Table 2: Practical considerations for NGS approach selection

| Consideration | Targeted Panels | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Considerations | Most economical [25] | Cost-effective intermediate [25] | Highest cost (2-3x WES for data analysis) [25] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Well-characterized genetic conditions; known gene sets [25] | Non-specific symptoms; heterogeneous conditions; first-tier testing [25] | Unexplained rare diseases; negative WES/panel results; comprehensive variant detection [25] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Lowest | Moderate | Highest (∼3 million variants/sample) [25] |

| Reanalysis Potential | Limited (one-time analysis) [25] | High (as new genes discovered) | Highest (complete genomic record) |

| ACMG Recommendation | - | Primary/secondary test for CA/DD/ID [25] | Primary/secondary test for CA/DD/ID [25] |

Decision Framework for NGS Approach Selection

Selecting the appropriate NGS methodology requires careful consideration of the research context and constraints. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) has recommended both WES and WGS as primary or secondary testing options for patients with rare genetic diseases, such as congenital abnormalities, developmental delays, or intellectual disabilities (CA/DD/ID) [25]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that WES and WGS can significantly increase diagnostic rates and provide greater clinical utility in such cases [25].

For research applications with clearly defined genetic targets, targeted panels offer the advantages of greater coverage depth and more straightforward data interpretation [25]. When investigating conditions with extensive locus heterogeneity or nonspecific presentations, WES provides a balanced approach that captures most known pathogenic variants while remaining cost-effective [25]. For the most comprehensive analysis, particularly when previous testing has been negative or when structural variants are suspected, WGS offers the highest diagnostic yield despite its greater computational demands [25].

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

Universal NGS Wet-Lab Protocol

The basic NGS workflow consists of four fundamental steps that apply across different sequencing approaches, though with specific modifications for each method [5] [6]:

Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA (or RNA for transcriptome studies) is isolated from the biological sample through cell lysis and purification to remove cellular contaminants. Sample quality and quantity are assessed through spectrophotometry or fluorometry [5] [6].

Library Preparation: This critical step fragments the DNA and ligates platform-specific adapters to the fragments. For targeted approaches, this step includes enrichment through hybridization-based capture or amplicon-based methods using probes or primers designed for specific genomic regions [5] [6]. WES uses exome capture kits (e.g., Agilent Clinical Research Exome) to enrich for exonic regions, while WGS processes the entire genome without enrichment [27].

Sequencing: Libraries are loaded onto sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina NextSeq) where sequencing-by-synthesis occurs. The platform generates short reads (100-300 bp) that represent the sequences of the DNA fragments [5] [27].

Data Analysis: Raw sequencing data undergoes quality control, alignment to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh37/hg19), variant calling, and annotation using specialized bioinformatics tools [5] [27].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of NGS data follows a structured pipeline to transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful results:

Quality Control and Read Filtering: Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format are assessed for quality using tools like FastQC. Low-quality bases and adapter sequences are trimmed to ensure data integrity [28] [27].

Alignment to Reference Genome: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38) using aligners such as Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA). This step produces SAM/BAM format files containing mapping information [28] [27].

Variant Calling: Genomic variants (SNVs and indels) are identified using tools like the Genome Analysis ToolKit (GATK). The resulting variants are stored in VCF format with quality metrics and filtering flags [27].

Variant Annotation and Prioritization: Detected variants are annotated with functional predictions, population frequencies, and disease associations using tools such as Variant Effect Predictor (VEP). Variants are then prioritized based on frequency, predicted impact, and phenotypic relevance [27].

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions for NGS workflows

| Research Reagent/Solution | Function in NGS Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent Clinical Research Exome | Exome capture kit for WES | Used for targeting protein-coding regions; v1 captures ~2% of genome [27] |

| Illumina NextSeq Platform | Sequencing instrument | Mid-output sequencer for WES and panels; uses sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry [27] |

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) | Alignment software | Aligns sequencing reads to reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) [27] |

| Genome Analysis ToolKit (GATK) | Variant discovery toolkit | Best practices for SNV and indel calling; version 3.8-0-ge9d806836 [27] |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Variant annotation tool | Annotates functional consequences of variants; version 88.14 [27] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification | Isolate high-quality DNA from blood or saliva samples [27] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA and add adapters | Platform-specific kits for Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore systems [6] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

NGS technologies have become indispensable tools throughout the drug development pipeline, from target identification to companion diagnostic development [26] [29]. Each NGS approach offers distinct advantages for specific applications in pharmaceutical research:

Target Identification and Validation: WGS and WES enable comprehensive genomic analyses to identify novel therapeutic targets by comparing genomes between affected and unaffected individuals. For example, researchers have identified 42 new risk indicators for rheumatoid arthritis through analysis of 10 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in over 100,000 subjects [29].

Drug Repurposing: SNP analysis through WGS can identify existing therapies that could be effective for other medical conditions. The same rheumatoid arthritis study revealed three drugs used in cancer treatment that could be potentially repurposed for RA treatment [29].

Combating Drug Resistance: NGS approaches help identify mechanisms of drug resistance and predict patient response to therapies. This application is particularly valuable in infectious disease research for understanding antimicrobial resistance and in oncology for addressing chemotherapy failures, which were estimated at 90% in 2017, largely due to drug resistance [29].

Precision Cancer Medicine: Targeted NGS panels enable the identification of biomarkers that predict treatment response. In bladder cancer, for example, tumors with a specific TSC1 mutation showed significantly better response to everolimus, illustrating how genetic stratification can identify patient subgroups that benefit from specific therapies [29].

Pharmacogenomics: WES provides cost-effective genotyping of pharmacogenetically relevant variants, helping to predict drug metabolism and adverse event risk, thereby supporting personalized treatment approaches [25] [26].

The selection of appropriate NGS methodologies represents a critical decision point in chemogenomics research and drug development. Targeted panels, whole exome sequencing, and whole genome sequencing each offer distinct advantages that make them suitable for specific research contexts and questions. Targeted panels provide cost-effective, deep coverage for well-characterized gene sets; WES offers a balanced approach for investigating coding regions with reasonable cost; while WGS delivers the most comprehensive genomic profile at higher computational expense. Understanding the technical specifications, performance characteristics, and practical implementation requirements of each approach enables researchers to align methodological choices with specific research objectives, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development through more effective genomic analysis.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research and clinical diagnostics by enabling the rapid sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [5]. For researchers in chemogenomics and drug development, a precise understanding of core NGS metrics—read depth, coverage, and variant allele frequency (VAF)—is fundamental to designing robust experiments and accurately interpreting genomic data. This technical guide delineates these critical parameters, their interrelationships, and their practical implications within the NGS workflow, providing a foundation for effective application in targeted therapeutic discovery and development.

Core Terminology and Definitions

Read Depth (Sequencing Depth)

Read depth, also termed sequencing depth or depth of coverage, refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide in the genome is sequenced [30] [31]. It is a measure of data redundancy at a given base position.

- Calculation: Expressed as an average multiple (e.g., 100x), meaning each base in the target region was sequenced, on average, 100 times [31].

- Primary Function: Higher read depth increases confidence in base calling and is critical for detecting low-frequency variants, such as somatic mutations in heterogeneous tumor samples or minor subclones in microbial populations [32] [31].

Coverage

Coverage describes the proportion or percentage of the target genome or region that has been sequenced at least once [31]. It reflects the completeness of the sequencing effort.

- Calculation: Typically expressed as a percentage (e.g., 95% coverage at 10x depth means 95% of the target bases were sequenced at least 10 times) [33].

- Primary Function: Ensures that the entirety of the genomic region of interest has been sampled, thereby minimizing gaps in the data that could lead to missed variants [31].

Variant Allele Frequency (VAF)

Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) is the percentage of sequence reads at a genomic position that carry a specific variant [32] [30].

- Calculation:

VAF = (Number of reads containing the variant / Total number of reads covering that position) * 100[30]. For instance, if 50 out of 1,000 reads at a position show a mutation, the VAF is 5% [30]. - Primary Function: VAF helps infer the prevalence of a mutation within a sample, which has critical implications in oncology for understanding tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and measurable residual disease (MRD) [32] [30].

The Interplay of Depth, Coverage, and VAF in Assay Sensitivity

The relationship between sequencing depth and VAF sensitivity is foundational to NGS assay design. Deeper sequencing directly enhances the ability to detect low-frequency variants with confidence [30].

The diagram above illustrates the logical relationship between these metrics. Higher sequencing depth mitigates the sampling effect, a phenomenon where a low number of reads can lead to overestimation, underestimation, or complete missing of variants [30]. With 100x coverage, a true 1% VAF might be represented by a single variant read, which could be easily missed or dismissed as an error. In contrast, with 10,000x coverage, the same 1% VAF would be represented by 100 variant reads, providing a statistically robust measurement [30].

Quantitative Guidelines for NGS Experiment Design

Selecting the appropriate sequencing depth is a critical decision that balances detection sensitivity with cost-effectiveness [30]. The required depth varies significantly based on the study's objective.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth by Application

| Research Application | Typical Sequencing Depth | Key Rationale and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Germline Variant Detection | 30x - 50x (WGS) [31] | Assumes variants are at ~50-100% VAF; lower depth is sufficient for confident calling [30]. |

| Somatic Variant Detection (Solid Tumors) | 100x - 500x and above [32] | Needed to detect subclonal mutations in samples with mixed tumor/normal cell populations [34]. |

| Measurable Residual Disease (MRD) | >1,000x (Ultra-deep) [32] [30] | Essential for identifying cancer-associated variants at VAFs well below 1% [30]. |

| VAF < 3% (e.g., TP53 in CLL) | ≥1,650x [32] | Recommended minimum depth for detecting 3% VAF with a threshold of 30 mutated reads, based on binomial distribution to minimize false positives/negatives [32]. |

The necessary depth is mathematically linked to the desired lower limit of VAF detection. Using binomial probability distribution, a minimum depth of 1,650x is recommended for reliable detection of variants at ≥3% VAF, with a supporting threshold of at least 30 mutated reads to minimize false positives and negatives [32]. Deeper coverage reduces the impact of sequencing errors, which typically range between 0.1% and 1%, thereby improving the reliability of low-frequency variant calls [32].

Methodological Framework: Implementing Metrics in the NGS Workflow

Understanding these terminologies is operationalized through a standardized NGS workflow, which consists of four key steps [35] [36].

The End-to-End NGS workflow

Detailed Methodologies for Key Steps

Library Preparation

This process converts extracted nucleic acids into a format compatible with the sequencer. DNA is fragmented (mechanically or enzymatically), and platform-specific adapters are ligated to the ends of the fragments [34]. These adapters facilitate binding to the flow cell and contain indexes (barcodes) that enable sample multiplexing—pooling multiple libraries for a single sequencing run, which dramatically improves cost-efficiency [33] [36]. An optional but common enrichment step (e.g., using hybridization capture or amplicon-based panels) can be incorporated to target specific genomic regions of interest [36] [37].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

During sequencing, massively parallel sequencing-by-synthesis occurs on instruments like Illumina systems [35]. The primary data output is a set of reads (sequence strings of A, T, C, G). In the analysis phase:

- Base Calling and Read Alignment: Sequences are aligned to a reference genome [34].

- Variant Calling and Calculation of Metrics: Bioinformatics tools identify differences from the reference. At this stage, read depth is calculated for each position, coverage is determined for the target region, and VAF is computed for each identified variant [36] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item / Reagent | Critical Function in the NGS Workflow |

|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-purity DNA/RNA from diverse sample types (e.g., blood, cells, tissue); quality is paramount for downstream success [36] [37]. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/Systems | Enzymatic (e.g., tagmentation) or mechanical (e.g., sonication) methods to shear DNA into optimal fragment sizes for sequencing [34] [37]. |

| Sequencing Adapters & Indexes | Short oligonucleotides ligated to fragments; enable cluster generation on the flow cell and sample multiplexing, respectively [33] [36]. |

| Target Enrichment Probes/Primers | For targeted sequencing; biotinylated probes (hybridization) or primer panels (amplicon) to isolate specific genomic regions [36] [34]. |

| Polymerase (PCR Enzymes) | Amplify library fragments; high-fidelity enzymes are essential to minimize introduction of amplification biases and errors during library prep [37]. |

Advanced Considerations in Clinical and Chemogenomics Applications

In translational research and drug development, these metrics directly impact the reliability of findings.

- Tumor Heterogeneity and Clonal Evolution: Cancers often contain multiple subclones with different mutations [34]. A sequencing depth sufficient to detect low-VAF variants (e.g., 1-5%) is necessary to fully characterize the tumor genome, understand resistance mechanisms, and identify potential therapeutic targets [32] [34].

- Standardization and Quality Control: The lack of consensus on minimum coverage depth remains a challenge in clinical NGS [32]. Laboratories must validate their assays by establishing a limit of detection (LOD) linked to sequencing depth, which defines the lowest VAF that can be reliably detected. For example, a study demonstrated that a coverage depth of only 100x resulted in a 30-45% false negative rate for detecting variants at 10% VAF, highlighting the risks of insufficient depth [32].

- Error Sources: The overall error rate of an NGS assay includes not only the intrinsic sequencing error (~0.1-1%) but also errors introduced during DNA processing and library preparation [32]. Deeper sequencing helps overcome these technical noises, ensuring that true biological variants are accurately discerned.

Read depth, coverage, and VAF are interdependent metrics that form the quantitative backbone of any rigorous NGS study. For chemogenomics researchers and drug development professionals, a nuanced grasp of these concepts is indispensable for designing sensitive and cost-effective experiments, interpreting complex genomic data from heterogeneous samples, and ultimately making informed decisions in the therapeutic discovery pipeline. By strategically applying the guidelines and methodologies outlined in this whitepaper—such as deploying ultra-deep sequencing for MRD detection—researchers can fully leverage the power of NGS to drive innovation in precision medicine.

The Step-by-Step NGS Laboratory Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

In the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for chemogenomics, the initial step of sample preparation and nucleic acid extraction is the most critical determinant of success. This phase involves the isolation of pure, high-quality genetic material (DNA or RNA) from biological samples, which serves as the foundational template for all subsequent sequencing processes [35] [38]. The profound impact of this step on final data quality cannot be overstated; even with the most advanced sequencers and library preparation kits, compromised starting material will inevitably derail an entire NGS run, leading to wasted resources and unreliable data [39]. For chemogenomics researchers, who utilize chemical compounds to probe biological systems and discover new therapeutics, the integrity of this genetic starting material is paramount for uncovering meaningful insights into gene expression, genetic variations, and drug-target interactions [40]. This guide details the essential protocols and considerations for ensuring that this first step establishes a robust foundation for your entire NGS workflow.

Core Principles and Quality Metrics

The primary goal of nucleic acid extraction is to obtain material that is optimal for library preparation. This is measured by three key metrics: Yield, Purity, and Quality [38] [36].

- Yield: This refers to the total amount of nucleic acid isolated. Most library preparation methods require nanograms to micrograms of DNA or cDNA (synthesized from RNA) [38] [36]. Sufficient yield is especially crucial when working with low-biomass samples, such as single cells or cell-free DNA (cfDNA).

- Purity: Isolated nucleic acids must be free of contaminants that can inhibit the enzymes used in later library preparation steps. Common inhibitors include reagents from the isolation process itself (e.g., phenol, ethanol, salts) or carryover from biological samples (e.g., heparin, humic acid, proteins) [38] [39].

- Quality: This pertains to the integrity and structural state of the nucleic acids. For DNA, this means it should be of high molecular weight and intact. For RNA, degradation must be minimized to ensure the transcriptome is accurately represented [38]. The importance of quality is highlighted by extensive analyses, such as one study of over 2,500 FFPE tissue samples, which found that samples with high DNA integrity had NGS success rates of ~94%, compared to only ~5.6% for low-integrity samples [39].

Table 1: Essential Quality Control Metrics for Nucleic Acids

| Metric | Description | Recommended Assessment Methods | Ideal Values/Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Total quantity of nucleic acid obtained. | Fluorometric assays (e.g., Qubit, PicoGreen) [38] [39]. | Nanograms to micrograms, as required by the library prep protocol [36]. |

| Purity | Absence of contaminants that inhibit enzymes. | UV Spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios) [35] [39]. | A260/280: ~1.8 (DNA), ~2.0 (RNA). A260/230: >1.8 [39]. |

| Quality/Integrity | Structural integrity and fragment size of nucleic acids. | Gel Electrophoresis; Microfluidic electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation); RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for RNA [38] [39]. | High molecular weight, intact bands for DNA; RIN > 8 for high-quality RNA [38]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Nucleic Acid Extraction Workflow

The following diagram outlines the generalized workflow for nucleic acid extraction, from sample collection to a qualified sample ready for library preparation.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Sample Collection and Stabilization [39] [37]

- Procedure: Immediately after collection, stabilize samples using appropriate methods to inhibit nucleases and prevent degradation. For tissues, this may involve flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen or immersion in stabilizers like RNAlater. For blood, use collection tubes containing anticoagulants like EDTA.

- Key Consideration: Minimize the number of freeze-thaw cycles, as each cycle incrementally degrades nucleic acids. Record comprehensive sample metadata (source, time, storage temperature) for traceability.

-

- Procedure: Lyse cells and tissues using a method tailored to the sample type. This can be:

- Mechanical: Grinding (for tough plant or tissue materials), or bead beating.

- Chemical: Use of detergents and chaotropic salts to disrupt membranes.

- Enzymatic: Application of enzymes like lysozyme (for bacteria) or proteinase K (for general protein digestion).

- Key Consideration: Optimize buffer composition and lysis conditions to completely break down cell walls and protein complexes without causing excessive shearing of genomic DNA.

- Procedure: Lyse cells and tissues using a method tailored to the sample type. This can be:

Separation and Purification [39] [36]

- Procedure: Separate nucleic acids from cellular debris (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates). This is commonly achieved through:

- Silica-Membrane Columns: Where nucleic acids bind to the membrane in the presence of a high-salt buffer.

- Magnetic Beads: Which bind nucleic acids and are retrieved using a magnet.

- Key Consideration: For challenging samples (e.g., plants, FFPE), additional cleanup steps may be necessary to remove specific inhibitors like polysaccharides or pigments.

- Procedure: Separate nucleic acids from cellular debris (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates). This is commonly achieved through:

-

- Procedure: Perform multiple wash steps with ethanol-based buffers to remove salts, solvents, and other contaminants while the nucleic acids remain bound to the column or beads.

- Key Consideration: Ensure residual ethanol is completely removed after the final wash, as it can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions. Avoid overdrying the membrane or beads, as this can make elution inefficient.

-

- Procedure: Elute the purified nucleic acids in a low-EDTA buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5-8.5) or nuclease-free water. Warming the elution buffer to 37-55°C and allowing it to incubate on the matrix for 2-5 minutes can improve yield.

- Key Consideration: The elution buffer must be compatible with downstream NGS library preparation steps. Buffers with high concentrations of EDTA can chelate magnesium ions and reduce enzyme activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Item/Kit | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | To disrupt cellular and nuclear membranes, releasing nucleic acids. | Buffer composition (detergents, salts, pH) must be optimized for specific sample types (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, fibrous tissue) [39]. |

| Protease (e.g., Proteinase K) | To digest histone and non-histone proteins, freeing DNA. | Essential for digesting tough tissues and inactivating nucleases. Incubation time and temperature are critical for efficiency [37]. |

| RNase A (for DNA isolation) | To degrade RNA contamination in a DNA sample. | Should be DNase-free. An incubation step is added after lysis. |

| DNase I (for RNA isolation) | To degrade DNA contamination in an RNA sample. | Should be RNase-free. Typically used on-column during purification [39]. |

| Silica-Membrane Spin Columns | To bind, wash, and elute nucleic acids based on charge affinity. | High-throughput and relatively simple. Well-suited for a wide range of sample types and volumes [39] [36]. |

| Magnetic Bead Kits | To bind nucleic acids which are then manipulated using a magnet. | Amenable to automation, reducing hands-on time and cross-contamination risk. Ideal for high-throughput workflows [39]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Additives (e.g., CTAB, PVPP) | To bind and remove specific contaminants like polyphenols and polysaccharides. | Crucial for challenging sample types such as plants, soil, and forensic samples [39]. |

Advanced Considerations for Challenging Samples

Working with low-quality or low-quantity starting material requires additional strategies:

- Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissues: Nucleic acids from FFPE samples are typically fragmented and cross-linked. Use isolation kits specifically designed for FFPE to maximize the recovery of sequenceable fragments. Target enrichment approaches or whole genome amplification may be necessary [38] [39].

- Single Cells and Low-Input Samples: When working with a limited quantity of nucleic acids, Whole Genome Amplification (WGA) or Whole Transcriptome Amplification (WTA) can be employed to generate sufficient material for library preparation. Enzymes with high processivity and low bias, such as phi29 DNA polymerase, are preferred for this purpose [38].

- Contamination Prevention: Contamination is a significant risk, especially with sensitive low-input applications.

- Strategies: Implement strict physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas, use aerosol-resistant filter tips, decontaminate surfaces with UV irradiation or bleach, and include negative controls (extraction blanks) in every run [39].

- Common Sources: Be aware of "kitome" contamination (background DNA in reagents), cross-sample carryover, and amplicon contamination from previous PCRs [39].

For chemogenomics beginners, mastering sample preparation and nucleic acid extraction is the first and most vital investment in a successful NGS research program. By rigorously adhering to protocols that prioritize the yield, purity, and integrity of genetic material, researchers lay a solid foundation for the subsequent steps of library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [35] [5]. A disciplined approach at this initial stage, including meticulous quality control and contamination prevention, will pay substantial dividends in the form of reliable, high-quality genomic data, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel biological insights and therapeutic targets [40].

In the context of a chemogenomics research pipeline, next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides powerful tools for understanding compound-genome interactions. Library preparation represents a critical early step that fundamentally determines the quality and reliability of all subsequent data analysis. This technical guide focuses on two core processes within library preparation: DNA fragmentation, which creates appropriately sized genomic fragments, and adapter ligation, which outfits these fragments for sequencing. Proper execution of these steps ensures maximal information recovery from precious chemogenomic samples, whether screening compound libraries against genomic targets or investigating drug-induced genomic changes.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from purified DNA to a sequence-ready library, highlighting the fragmentation and adapter ligation steps within the broader context.

DNA Fragmentation Strategies

The initial step in NGS library preparation involves fragmenting purified DNA into sizes optimized for the sequencing platform and application. The method of fragmentation significantly impacts library complexity, coverage uniformity, and potential for sequence bias, all critical considerations for robust chemogenomic assays [41] [42].

Comparison of Fragmentation Methods

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DNA Fragmentation Methods

| Method | Typical Input DNA | Fragment Size Range | Hands-On Time | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Shearing (Covaris) | 1–5 μg [41] | 100–5,000 bp [42] | Moderate | Unbiased fragmentation, consistent fragment sizes [41] | Specialized equipment cost, potential for sample overheating [41] |

| Sonication (Probe-based) | 1–5 μg [41] | 300–600 bp [41] | Moderate | Simple methodology, focused energy [41] | High contamination risk, requires optimization cycles [41] |

| Nebulization | Large input required [41] | Varies with pressure | Low | Simple apparatus | High sample loss, low recovery [41] |

| Enzymatic Digestion | As low as 1 ng [41] [43] | 200–600 bp | Low | Low input requirement, streamlined workflow, automation-friendly [41] [43] | Potential sequence bias, artifactual indels [42] [43] |